Abstract

Context

Patient-reported outcomes (PRO) data from randomised controlled trials (RCTs) are increasingly used to inform patient-centred care as well as clinical and health policy decisions.

Objective

The main objective of this study was to investigate the methodological quality of PRO assessment in RCTs of prostate cancer (PCa) and to estimate the likely impact of these studies on clinical decision making.

Evidence acquisition

A systematic literature search of studies was undertaken on main electronic databases to retrieve articles published between January 2004 and March 2012. RCTs were evaluated on a predetermined extraction form, including (1) basic trial demographics and clinical and PRO characteristics; (2) level of PRO reporting based on the recently published recommendations by the International Society for Quality of Life Research; and (3) bias, assessed using the Cochrane Risk of Bias tool. Studies were systematically analysed to evaluate their relevance for supporting clinical decision making.

Evidence synthesis

Sixty-five RCTs enrolling a total of 22 071 patients were evaluated, with 31 (48%) in patients with nonmetastatic disease. When a PRO difference between treatments was found, it related in most cases to symptoms only (n = 29, 58%). Although the extent of missing data was generally documented (72% of RCTs), few reported details on statistical handling of this data (18%) and reasons for dropout (35%). Improvements in key methodological aspects over time were found. Thirteen (20%) RCTs were judged as likely to be robust in informing clinical decision making. Higher-quality PRO studies were generally associated with those RCTs that had higher internal validity.

Conclusions

Including PRO in RCTs of PCa patients is critical for better evaluating the treatment effectiveness of new therapeutic approaches. Marked improvements in PRO quality reporting over time were found, and it is estimated that at least one-fifth of PRO RCTs have provided sufficient details to allow health policy makers and physicians to make critical appraisals of results.

Patient summary

In this report, we have investigated the methodological quality of PCa trials that have included a PRO assessment. We conclude that including PRO is critical to better evaluating the treatment effectiveness of new therapeutic approaches from the patient's perspective. Also, at least one-fifth of PRO RCTs in PCa have provided sufficient details to allow health policy makers and physicians to make a critical appraisal of results.

Keywords: Prostate cancer, Patient-reported outcomes, Clinical trials, Quality of life, Clinical decision making

1. Introduction

The global burden of prostate cancer (PCa) rose from 200 000 new cases each year in 1975 to reach an estimated 700 000 new cases in 2002 [1]. In 2013, approximately 238 000 men in the Unites States will be diagnosed with PCa, and 30 000 will be expected to die from the disease [2].

Treatments for patients with localised disease include radical prostatectomy (RP), active surveillance, and radiation therapy (RT), while hormone therapy is typically used in patients with advanced disease [3]. All of these treatments are associated with specific side effects resulting in considerable impairment in several health-related quality of life (HRQOL) domains [3,4]. Thus, the inclusion of HRQOL assessment in randomised controlled trials (RCTs) testing different interventions for PCa is crucial for understanding which approach is best from the patient's perspective.

Patient-reported outcomes (PRO) data from RCTs, which include HRQOL and other health aspects reported by patients themselves [5], are increasingly used to inform patient-centred care as well as clinical and health policy decisions [6]. Thousands of PCa patients have been enrolled in RCTs with a PRO component [7], with the ultimate goal being to provide key information on overall treatment effectiveness. Some of these RCTs have generated high-quality PRO evidence and have formed the basis for approval of drugs based on patients' subjective reports [8]. For example, Tannock et al. [9] and Osoba et al. [8], comparing prednisone with or without mitoxantrone in symptomatic patients with hormone-resistant cancer, observed significantly better and lasting HRQOL outcomes for patients treated with mitoxantrone plus prednisone. Based on this RCT and specifically on patient-reported pain, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) subsequently granted approval of mitoxantrone [10].

However, the number of high-quality studies in PCa with such impact, facilitating individual patient decision making or treatment policies, is low [11]. Although inclusion of PRO into clinical comparative effectiveness research and drug development has been recommended to understand the patient experience [12,13], earlier work has shown a number of methodological drawbacks in PRO reporting from RCTs, including various cancer disease sites[14–16]. In a systematic review of studies published between 1980 and 2001, Efficace et al. showed that this was also the case for RCTs of PCa [7]. However, given the increasing interest of the scientific community and stakeholders in the use and application of PRO [17], it is of paramount importance to rely on the most solid and up-to-date evidence and identify which methodological aspects are most in need of improvement.

The main objective of this study was to investigate the methodological quality of PRO assessment in RCTs of PCa conducted since the previous survey. Secondary objectives were to estimate the likely impact of these studies on clinical decision making and to evaluate whether the standard of reporting has improved over time.

2. Evidence acquisition

2.1. Search strategy for identification of studies

A systematic literature search for studies meeting the criteria was undertaken on the electronic databases PubMed/ Medline, the Cochrane Library, PsycINFO, and PsycARTICLES from January 2004 to March 2012. Relevant studies listed as references were also considered. The following script was used to identify all RCTs that had a PRO component: (“quality of life” OR “health related quality of life” OR “health status” OR “health outcomes” OR “patient outcomes” OR depression OR anxiety OR emotional OR social OR psychosocial OR psychological OR distress OR “social functioning” OR “social wellbeing” OR “patient reported symptom” OR “patient reported outcomes” OR pain OR fatigue OR “patient reported outcome” OR PRO OR PROs OR HRQL OR QOL OR HRQOL OR “symptom distress” OR “symptom burden” OR “symptom assessment” OR “functional status” OR sexual OR functioning) AND prostate.

The search strategy for PubMed/Medline was restricted to RCTs. No restriction in the search field description was performed, and only English-language articles were considered. We also contacted experts in the field to identify possible articles not retrieved in the electronic search. Details on the search strategy and selection process were documented according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analysis guidelines [18].

2.2. Criteria for considering studies

2.2.1. Types of participants

Adult patients diagnosed with PCa regardless of disease stage were included. Studies on patients with benign prostatic hyperplasia and those undergoing prevention or screening procedures were not eligible.

2.2.2. Types of intervention

Interventions included any RCTs comparing conventional treatments. Studies dealing with psychosocial interventions or complementary and alternative medicine were excluded.

2.2.3. Types of outcome measures examined

Any studies including a PRO, either as a primary or secondary end point, were considered. Thus, we included both HRQOL multidimensional self-reported patient measures and any other type of PRO (not necessarily HRQOL) measuring the impact of the disease and treatment-related effects. Studies evaluating adherence to therapy or satisfaction with care were not included.

2.2.4. Types of studies

All RCTs comparing different conventional medical treatment modalities and symptom management enrolling at least 50 PCa patients (combined arms) were studied. Publications meeting the above criteria but considering a heterogeneous cancer patient sample were not included because of the possible difficulties in interpreting PRO results relating specifically to PCa patients. Conference abstracts and case reports were not considered.

2.3. Methods of study evaluation

A Web-based data-collection system was developed for the purpose of this research (http://promotionproject.gimema.it). Two reviewers (V.C. and M.F.) independently reviewed all identified studies, and a third reviewer (F.E.) was consulted in case of disagreement. Each reviewer had password access to the online system and completed apredefined electronic data-extraction form (eDEF) for each RCT meeting the study criteria (the eDEF is reported in the online Supplement). A double-blind data-entry procedure was performed, and discrepancies in evaluations were electronically recorded. When disagreements occurred in the eDEF, the reviewers revisited the paper to reconcile any differences until consensus was achieved, and a final eDEF was validated and used for data analysis. Some trials had multiple publications, in which case the relevant data from all articles were combined.

2.4. Type of information extracted

Data extracted from each RCT and reported in the eDEF included (1) basic trial demographics and clinical and PRO characteristics (eg, number of patients enrolled, study location, treatments being compared, PRO instrument used, clinical and PRO assessments); (2) grade of PRO reporting based on the recently published recommendations by the International Society for Quality of Life Research (ISOQOL) [19]; and (3) bias, assessed using the Cochrane Risk of Bias tool, which rates RCTs for their adequacy of sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding of participant and personnel, incomplete outcome data, blinding of outcome assessment, selective outcome reporting, and other possible sources of bias [20].

2.5. Assessment of level of reporting and definition of high-quality patient-reported outcomes studies

Several checklists have been proposed and used to evaluate the quality of PRO reporting in RCTs [11,21,22], but only one has been endorsed by a major scientific society and developed with input from a large international panel of experts: the ISOQOL consensus-based recommendations for reporting PRO in publications of RCTs [19]. This guideline represents the highest-quality criteria available at the time of this study and forms the basis of the recently published Consolidated Standards of Reporting in Trials (CONSORT) PRO extension [23].

The ISOQOL checklist consists of a common set of 17 key issues that are to be documented for all RCTs, regardless of the type of PRO (either primary or secondary end point). An additional 11 issues are pertinent only when a PRO is a primary end point of the RCT [19]. Each item of the ISOQOL checklist was rated as yes if documented in the publication (scored as 1) or no if not documented (scored 0). We note that although the ISOQOL checklist contains a common set of 17 items [19], the one addressing the problem of missing data (ie, reporting the extent of and statistical approaches for dealing with missing data) was divided in two to better investigate accuracy of reporting. Each RCT thus received a score ranging from 0 to a maximum of 18 (PRO as a secondary end point) or 29 (primary end point); in both cases, the higher the score, the greater the robustness of the outcomes.

Given that the purpose of this study was to assess quality of PRO evidence and estimate the likely impact on clinical decision making, we needed to define the meaning of high-quality PRO study. As in previous works [11,24], we propose that at least two-thirds of the recommended criteria must be satisfied. Thus, our rule of thumb was that PRO evidence can be judged as “high quality” if at least 12 of 18 (secondary end point) or 20 of 29 (primary end point) criteria are satisfied. In addition, following previous work [11], the reporting of satisfactory levels for the following three criteria was considered mandatory: baseline compliance, psychometric properties, and missing data reported. If items were considered “not applicable,” the cut-off was adjusted accordingly (but the three mandatory criteria still had to be met). RCTs that either failed to reach the high-quality cut-off scores or did not take into account the three mandatory items were judged as reporting too little information to robustly inform clinical decision making.

Possible differences over time in the level of reporting of key selected PRO quality criteria between the current review and a previous report [7] were investigated using the chi-square test (α = 0.05).

3. Evidence synthesis

After having screened 1885 records, we identified 65 RCTs enrolling a total of 22 071 patients published between January 2004 and March 2012. For these studies, 116 papers were retrieved, including those related to the original RCT publication (the full list is reported in the online Supplement). Figure 1 details the search strategy and selection process.

Fig. 1.

Schematic breakdown of literature search results of Prostate Randomised Controlled Trials (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analysis).

PRO = patient-reported outcomes.

3.1. Overview of study demographics and patient-reported outcomes assessment

In 26 (40%) RCTs, a PRO was a primary end point. Nineteen studies (29%) were carried out in a multinational context, and 34 (52%) were at least partially supported by industry. Thirty-one (48%) involved patients with localised disease, and 21 (32%) recruited patients with metastatic (either hormone-sensitive or castration-resistant) disease. More than half of the RCTs (52%) enrolled >200 patients and in these larger studies, PRO were less frequently primary end points (23% of RCTs).

The two most frequently used PRO instruments, used alone or in conjunction with other measures, were the European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) QLQ-C30 in 18 RCTs (28%) and the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-General (FACT-G) in 13 RCTs (20%). A PRO difference was found in 50 (77%) studies. When a PRO difference between treatments was found, it related to symptoms only in 29 (58%) studies, PRO domains other than symptoms (ie, functional or psychosocial status or global HRQOL domains) in 5 (10%) studies, or both in 16 (32%) studies. Further details are provided in Table 1.

Table 1. Randomised clinical trial demographic characteristics.

| Variable | PRO end point, no. (%) | Total no. (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary 26 (40) | Secondary 39 (60) | ||

| Basic RCT demographics | |||

| International | |||

| No | 22 (84.62) | 24 (61.54) | 46 (70.77) |

| Yes | 4 (15.38) | 15 (38.46) | 19 (29.23) |

| Industry supported (fully or in part)* | |||

| No | 14 (53.85) | 17 (43.59) | 31 (47.69) |

| Yes | 12 (46.15) | 22 (56.41) | 34 (52.31) |

| Overall study sample size (regardless of patients included in the PRO analysis) | |||

| ≤200 patients | 18 (69.23) | 13 (33.33) | 31 (47.69) |

| >200 patients | 8 (30.77) | 26 (66.67) | 34 (52.31) |

| Disease stage | |||

| Advanced/metastatic | 3 (11.54) | 18 (46.15) | 21 (32.31) |

| Locoregional/no distant metastasis | 15 (57.69) | 16 (41.03) | 31 (47.69) |

| Mixed disease stages | 8 (30.77) | 5 (12.82) | 13 (20) |

| Broad treatment type | |||

| RT | 7 (26.92) | 14 (35.90) | 21 (32.31) |

| Surgery | 8 (30.77) | 2 (5.13) | 10 (15.38) |

| Chemotherapy | 0 (0) | 13 (33.33) | 13 (20.00) |

| HT | 11 (42.31) | 14 (35.90) | 25 (38.46) |

| Difference between treatment arms in the primary end point | |||

| No | 7 (26.92) | 13 (33.33) | 20 (30.77) |

| Yes | 19 (73.08) | 26 (66.67) | 45 (69.23) |

| OS difference favouring experimental treatment | |||

| No | 4 (15.38) | 19 (48.72) | 23 (35.38) |

| Yes | 0 (0) | 12 (30.77) | 12 (18.46) |

| N/A (in case OS was not assessed) | 22 (84.62) | 8 (20.51) | 30 (46.15) |

| PRO-related basic characteristics | |||

| PRO instrument used | |||

| EORTC instruments | 6 (23.08) | 12 (30.77) | 18 (27.69) |

| FACT Instruments | 1 (3.84) | 12 (30.77) | 13 (20.00) |

| VAS | 4 (15.38) | 3 (7.69) | 7 (10.77) |

| Others | 15 (57.70) | 12 (30.77) | 27 (41.54) |

| PRO difference between treatment arms | |||

| No differences at all | 5 (19.23) | 9 (23.08) | 14 (21.54) |

| Yes, broadly favouring experimental treatment† | 17 (65.38) | 19 (48.72) | 36 (55.38) |

| Yes, broadly favouring standard treatment† | 4 (15.38) | 10 (25.64) | 14 (21.54) |

| N/A | 0 (0) | 1 (2.56) | 1 (1.54) |

| If statistically significant PRO difference exists, in which domain? | |||

| Symptoms only | 13 (61.90) | 16 (55.18) | 29 (58.00) |

| PRO domains other than symptoms only (eg, functional scales, global QoL) | 1 (4.77) | 4 (13.79) | 5 (10.00) |

| Both domains (symptoms + domains other than symptoms) | 7 (33.33) | 9 (31.03) | 16 (32.00) |

| Length of PRO assessment during RCT | |||

| ≤6 mo | 12 (46.15) | 10 (25.64) | 22 (33.85) |

| ≤1 yr | 7 (26.92) | 8 (20.51) | 15 (23.08) |

| >1 yr | 7 (26.92) | 21 (53.85) | 28 (43.08) |

| Secondary paper on PRO‡ | |||

| No | 25 (96.15) | 23 (58.97) | 48 (73.85) |

| Yes | 1 (3.85) | 16 (41.03) | 17 (26.15) |

PRO = patient-reported outcomes; RCT = randomised controlled trial; RT = radiation therapy; HT = hormone therapy; OS = overall survival; EORTC = European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer; FACT = Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy; VAS = visual analogue scale; QoL = quality of life; HRQOL = health-related quality of life.

Assessed if explicitly stated or if one author or more were affiliated with a pharmaceutical company. This evaluation is based solely on information extracted from the paper.

Often, multiple PRO domains (eg, from multidimensional HRQOL questionnaires) are analysed at the same time in longitudinal PRO RCTs; to illustrate, difference in such domains might favour the experimental treatment arm at a given time point and then favour the control treatment arm at a different time point over the course of the study. The term broadly was inserted to account for this possible discrepancy, and final evaluation was based on reviewers' consensus.

Assessed as yes if at least one paper was published in addition to the original RCT report.

3.2. Overview of the health-related quality of life assessment methodology

A major limitation in publications was the lack of documentation of the mode of administration of the PRO instruments (for example, by telephone, by computer touch screen, or administered by health care professionals in a specific setting), with only 23% of RCTs reporting on this aspect. Of those that documented this information, none used electronic administration. Although the extent of missing data was generally documented (72% of RCTs), few reported details on statistical handling of this missing data (18%) or reasons for dropout (35%). Thus, although missing data is a crucial aspect in PRO RCTs, the level of details provided amongst reports was highly variable and ranged from studies that did not even report basic percentages of dropout over time to high-quality reports fully documenting both the lack of data and statistical methods to manage the problem [25]. Clinical significance of PRO findings was addressed in 32% of RCTs; of these, the majority (71%) discussed this issue in terms of minimally important difference. Full details on the level of reporting are provided in Table 2.

Table 2. Level of patient-reported outcomes (PRO) reporting by type of end point (PRO primary vs secondary end point of the trial).

| PRO end point, no. (%) | Total no. (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary 26 (40) | Secondary 39 (60) | ||

| Title and abstract | |||

| The PRO should be identified as an outcome in the abstract. | |||

| No | 0 (0) | 6 (15.38) | 6 (9.23) |

| Yes | 26 (100) | 33 (84.62) | 59 (90.77) |

| The title of the paper should be explicit as to the RCT including a PRO. | |||

| No | 10 (38.46) | – | 10 (38.46) |

| Yes | 16 (61.54) | – | 16 (61.54) |

| Introduction, background, and objectives | |||

| The PRO hypothesis should be stated and specify the relevant PRO domain, if applicable. | |||

| No | 1 (3.85) | 10 (25.64) | 11 (16.92) |

| Yes | 13 (50) | 11 (28.21) | 24 (36.92) |

| N/A (if explorative) | 12 (46.15) | 18 (46.15) | 30 (46.15) |

| The introduction should contain a summary of PRO research that is relevant to the RCT. | |||

| No | 3 (11.54) | – | 3 (11.54) |

| Yes | 23 (88.46) | – | 23 (88.46) |

| Additional details regarding the hypothesis should be provided, including the rationale for the selected domains, the expected directions of change, and the time points for assessment. | |||

| No | 22 (84.62) | – | 22 (84.62) |

| Yes | 4 (15.38) | – | 4 (15.38) |

| Methods | |||

| Outcomes | |||

| The mode of administration of the PRO tool and the methods of collecting data should be described. | |||

| No | 19 (73.08) | 31 (79.49) | 50 (76.92) |

| Yes | 7 (26.92) | 8 (20.51) | 15 (23.08) |

| An electronic mode of PRO administration was used.* | |||

| No | 7 (26.92) | 8 (20.51) | 15 (23.08) |

| N/A | 19 (73.08) | 31 (79.49) | 50 (76.92) |

| The rationale for the choice of the PRO instrument used should be provided. | |||

| No | 8 (30.77) | 16 (41.03) | 24 (36.92) |

| Yes | 18 (69.23) | 23 (58.97) | 41 (63.08) |

| Evidence of PRO instrument validity and reliability should be provided or cited. | |||

| No† | 10 (38.46) | 12 (30.77) | 22 (33.85) |

| Yes | 16 (61.54) | 27 (69.23) | 43 (66.15) |

| The intended PRO data-collection schedule should be provided. | |||

| No | 2 (7.69) | 4 (10.26) | 6 (9.23) |

| Yes | 24 (92.31) | 35 (89.74) | 59 (90.77) |

| PRO should be identified in the trial protocol post hoc analyses. | |||

| No | 16 (61.54) | 36 (92.31) | 52 (80) |

| Yes | 10 (38.46) | 3 (7.69) | 13 (20) |

| The status of PRO as either a primary or secondary outcome should be stated. | |||

| No | 3 (11.54) | 6 (15.38) | 9 (13.85) |

| Yes | 21 (80.77) | 27 (69.23) | 48 (73.85) |

| Unclear | 2 (7.69) | 6 (15.38) | 8 (12.31) |

| A citation for the original development of the PRO instrument should be provided. | |||

| No† | 11 (42.31) | – | 11 (42.31) |

| Yes | 15 (57.69) | – | 15 (57.69) |

| Windows for valid PRO responses should be specified and justified as being appropriate for the clinical context. | |||

| No | 7 (26.92) | – | 7 (26.92) |

| Yes | 19 (73.08) | – | 19 (73.08) |

| Sample size | |||

| There should be a power sample size calculation relevant to the PRO based on a clinical rationale. | |||

| No | 10 (38.46) | – | 10 (38.46) |

| Yes | 16 (61.54) | – | 16 (61.54) |

| Statistical methods | |||

| There should be evidence of appropriate statistical analysis and tests of statistical significance for each PRO hypothesis tested. | |||

| No | 1 (3.85) | 1 (2.56) | 2 (3.08) |

| Yes | 12 (46.15) | 10 (25.64) | 22 (33.85) |

| N/A (If PRO hypotheses were not stated) | 13 (50) | 28 (71.79) | 41 (63.08) |

| The extent of missing data should be stated.‡ | |||

| No | 5 (19.23) | 13 (33.33) | 18 (27.69) |

| Yes | 21 (80.77) | 26 (66.67) | 47 (72.31) |

| Statistical approaches for dealing with missing data should be explicitly stated.‡ | |||

| No | 23 (88.46) | 30 (76.92) | 53 (81.54) |

| Yes | 3 (11.54) | 9 (23.08) | 12 (18.46) |

| Methods | |||

| The manner in which multiple comparisons have been addressed should be provided. | |||

| No | 19 (73.08) | – | 19 (73.08) |

| Yes | 7 (26.92) | – | 7 (26.92) |

| Results | |||

| Participant flow | |||

| A flow diagram or a description of the allocation of participants and those lost to follow-up should be provided for PRO specifically. | |||

| No | 14 (53.85) | 27 (69.23) | 41 (63.08) |

| Yes | 12 (46.15) | 12 (30.77) | 24 (36.92) |

| The reasons for missing data should be explained. | |||

| No | 14 (53.85) | 28 (71.79) | 42 (64.62) |

| Yes | 12 (46.15) | 11 (28.21) | 23 (35.38) |

| Baseline data | |||

| The study patients' characteristics should be described, including baseline PRO scores. | |||

| No | 10 (38.46) | 13 (33.33) | 23 (35.38) |

| Yes | 16 (61.54) | 26 (66.67) | 42 (64.62) |

| Outcomes and estimation | |||

| Are PRO outcomes also reported in a graphical format?* | |||

| No | 9 (34.62) | 17 (43.59) | 26 (40) |

| Yes | 17 (65.38) | 22 (56.41) | 39 (60) |

| The analysis of PRO data should account for survival differences between treatment groups, if relevant. | |||

| No | 1 (3.85) | – | 1 (3.85) |

| N/A (if not relevant) | 25 (96.15) | – | 25 (96.15) |

| Results should be reported for all PRO domains (if multidimensional) and items identified by the reference instrument. | |||

| No | 3 (11.54) | – | 3 (11.54) |

| Yes | 23 (88.46) | – | 23 (88.46) |

| The proportion of patients achieving predefined responder definitions should be provided where relevant. | |||

| No | 1 (3.85) | – | 1 (3.85) |

| Yes | 7 (26.92) | – | 7 (26.92) |

| N/A (if not relevant) | 18 (69.23) | – | 18 (69.23) |

| Discussion | |||

| Limitations | |||

| The limitations of the PRO components of the trial should be explicitly discussed. | |||

| No | 16 (61.54) | 26 (66.67) | 42 (64.62) |

| Yes | 10 (38.46) | 13 (33.33) | 23 (35.38) |

| Generalizability | |||

| Generalizability issues uniquely related to the PRO results should be discussed. | |||

| No | 10 (38.46) | 18 (46.15) | 28 (43.08) |

| Yes | 16 (61.54) | 21 (53.85) | 37 (56.92) |

| Interpretation | |||

| Are PRO interpreted (not just restated)?* | |||

| No | 2 (7.69) | 17 (43.59) | 19 (29.23) |

| Yes | 24 (92.31) | 22 (56.41) | 46 (70.77) |

| The clinical significance of the PRO findings should be discussed. | |||

| No | 22 (84.62) | 22 (56.41) | 44 (67.69) |

| Yes | 4 (15.38) | 17 (43.59) | 21 (32.31) |

| What methodology was used to assess clinical significance (if this was addressed)?* | |||

| Anchor based | 2 (50) | 13 (76.47) | 15 (71.43) |

| Distribution based | 2 (50) | 4 (23.53) | 6 (28.57) |

| The PRO results should be discussed in the context of the other clinical trial outcomes. | |||

| No | 0 (0) | 4 (10.26) | 4 (6.15) |

| Yes | 26 (100) | 35 (89.74) | 61 (93.85) |

| Other information | |||

| Protocol | |||

| A copy of the instrument should be included if it has not been published previously (It could be found in the article appendix or in the online version). | |||

| No | 13 (50) | – | 13 (50) |

| Yes | 13 (50) | – | 13 (50) |

PRO = patient-reported outcomes; RCT = randomised controlled trial; ISOQOL = International Society for Quality of Life Research; CONSORT = Consolidated Standards of Reporting in Trials.

For descriptive purposes, subheadings of this table reflect those reported in the ISOQOL recommended standards [19]; however, rating of items was independent of location of the information within the manuscript.

Indicates items that are not applicable, as these are recommended to be reported only when PRO is a primary end point.

These items were not included in the ISOQOL recommended standards [19] but have been evaluated in our study and reported in this table to have a wider outlook on the level of reporting.

We evaluated as no if all PRO measures used in the study were not validated.

These items were originally combined in the ISOQOL recommended standards [19] but have been split in this report to better investigate possible discrepancies between documentation of PRO missing data (ie, reporting how many patients did not complete a given questionnaire at any given time point) versus actual reporting of statistical methods to address this issue. Also, we wanted to be consistent with items reported in the CONSORT PRO Extension [23] (ie, statistical approaches for dealing with missing data is reported as a stand-alone issue).

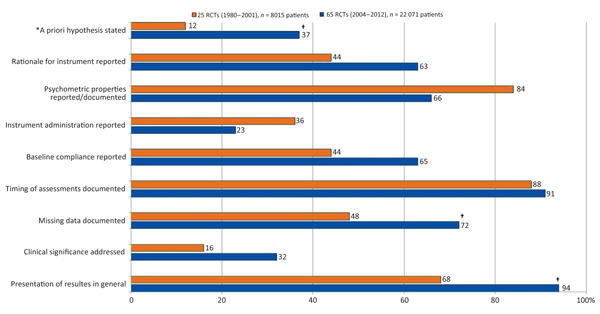

To investigate differences over time in the level of reporting, results found in the current review with regard some key methodological issues were compared with those of a similar systematic review for PCa RCTs from 1980 and 2001 [7]. Marked important improvements were found over time. For example, although an a priori hypothesis was reported in only 12% of studies published up to 2001, this percentage increased to 37% for RCTs published between 2004 and 2012 (p = 0.020). Similarly, documentation of missing data was found in 48% of RCTs published up to 2001 but improved up to 72% (p = 0.029) in the present survey. Details are reported in Figure 2.

Fig. 2.

Descriptive comparison of the level of reporting on selected key patient-reported outcomes issues in randomised controlled trials of prostate cancer by year of publication.

RCT = randomised controlled trial.

*This percentage is calculated by considering all studies reviewed (including those mentioning an exploratory evaluation); data from RCTs published between 1980 and 2001 were extracted from Efficace et al. [7].

†A statistically significant difference of p < 0.05.

3.3. Overview of treatment recommendations based on higher-quality patient-reported outcomes studies

Thirteen (20%) of the 65 RCTs were judged likely to be robust in informing clinical decision making. These reports are summarised in Supplemental Table 1. Of these, seven RCTs dealt with advanced metastatic disease, four with localised disease, and two RCTs enrolled patients with both metastatic and localised disease.

In metastatic, castration-resistant disease, the two largest RCTs had overall survival (OS) as primary end points, with 815 patients [26] and 629 patients [27] in the PRO analysis. Tannock and colleagues [26] showed that prednisone plus docetaxel every 3 wk, when compared with prednisone plus mitoxantrone or prednisone plus weekly administration of docetaxel, not only provided significantly better OS but also the greatest benefits in terms of HRQOL [26]. PRO details from this study were published in several reports [26,28–31].

Such was not the case for the other large PRO study, published by Berry and colleagues [32], which showed that docetaxel plus estramustine, compared with mitoxantrone plus prednisone, is associated with a slight increase in nausea and vomiting at 10 wk and 6 mo, but overall HRQOL is substantially similar between groups. This analysis complemented previously reported clinical efficacy findings [27] by showing that survival advantages obtained with docetaxel plus estramustine (compared to mitoxantrone plus prednisone) are not offset by worse HRQOL outcomes.

The largest study in patients with localised disease was published by Warde and colleagues comparing androgen deprivation with or without RT [33]. This study showed an OS advantage in the RT arm, with no PRO differences at 36 mo. Fransson and colleagues [34] performed a similar study and showed that androgen deprivation plus RT was associated with a worse bowel, urinary, and sexual function as well as social function at 4 yr. However, as these differences were considered small and given the survival benefit of androgen deprivation plus RT, previously found, the authors supported the value of this approach [34].

Another important PRO finding in patients with localised disease was published by the SWOG [25]. In this study, PRO was a secondary end point of an RCT comparing RP plus observation with RP plus adjuvant RT [35]. The primary end point favoured the RP plus RT arm in terms of metastasis-free survival and OS [35]. Additional PRO analysis revealed that worse bowel and urinary function were associated with RP plus RT. Interestingly, however, at 5 yr, patients treated with RP plus RT had better HRQOL outcomes than those treated with RP alone [25].

Figure 3 depicts risk of bias in all RCTs, subdivided by the PRO quality rating (high versus low). Higher-quality PRO studies were generally associated with those RCTs that had higher internal validity (ie, free from bias). For example, although the risk of bias from the lack of blinding of participants and personnel was low in 92% of higher-quality PRO studies, this risk was considered low in only 44% of poorer-quality PRO studies.

Fig. 3.

Bar chart showing the risk of bias across randomised controlled trials by quality of patient-reported outcomes studies.

PRO = patient-reported outcomes.

3.4. Discussion

More than 20 000 PCa patients have been enrolled in 65 RCTs with a PRO component over the past 8 yr, with the aim of providing important information to better inform clinical decision making. Of these RCTs, we estimated that one-fifth (20%) might have successfully reached this goal by providing solid PRO data from which to draw meaningful conclusions. It is considered, therefore, that the PRO data in these trials can be used to inform clinical practice and decision making and that future trials use this robust approach to PRO and trial study design.

The number of studies found in this systematic review is remarkable if compared with the previous review, which identified 25 RCTs enrolling some 8000 patients and published in the 21-yr time span from 1980 to 2001 [7]. This finding might reflect the substantial increasing interest of the scientific community and the fact that PRO are now highly valued by stakeholders and are often considered a routine outcome measure in trials [5].

The results of the present study with regard to quality of PRO reporting could be better interpreted in relation with those reported by Efficace et al. [7] reviewing HRQOL RCTs in PCa published between 1980 and 2001. Interestingly, some improvements in key methodological aspects over time were found, suggesting that investigators are becoming more familiar with the PRO issues that need to be addressed in clinical research. Several published guidelines might also have contributed in addressing previous methodological barriers to PRO implementation in RCTs. For example, although the clinical significance of PRO results was only addressed in 16% of studies published up to 2001, this percentage doubled in RCTs published between 2004 and 2012 (Fig. 2). Similarly, documentation of missing data also improved, but we also found a large discrepancy between documentation of the extent of PRO missing data (ie, reporting how many patients did not complete a questionnaire at any given time point) and the reporting of statistical methods to address this issue in data analysis. Very few studies (18%) documented this latter aspect. To our knowledge, no study has systematically investigated and reported on this discrepancy. The validity of model-based estimates from PRO longitudinal analyses might heavily depend on the amount of missing data and also on the extent to which missing data are not missing at random, especially if the dropout pattern is different across the treatment arms. Investigation of missing data mechanism and sensitivity analyses are thus critical to support the robustness of PRO findings [36,37]. A large variation in the level of missing data documentation (with regard to extent of, reasons for, and statistical handling) was found in our review, with some excellent examples [25] illustrating how to address and document this issue. Importantly, with regard to the key items that are included in the recently developed CONSORT PRO extension [23], our study showed that the level of reporting was suboptimal, with approximately 50% of fewer RCTs addressing the issue (Table 2). Urologists seeking to practice evidence-based medicine need to be increasingly cognizant of the recommended methodologies for conducting and reporting PRO-related research.

According to the US FDA, PRO can be defined as a measurement of any aspect of the “patient's health condition that comes directly from the patient, without interpretation of the patient's response by a clinician or anyone else” [5]. PRO can thus range from specific symptoms to more elaborate constructs such as HRQOL, which is a multidimensional construct consisting of at least four dimensions, including physical, psychological, and social function as well as disease- and treatment-related symptoms. An important issue often debated in the literature when designing an RCT with a PRO component [38] is whether the use of symptom outcome measures only suffices to properly inform on the value of a given treatment over another. Our study shows that when PRO differences were found, they were more frequently related to specific symptoms only (ie, in 58% of RCTs). In a minority of cases (10%), differences between groups were related to more generic aspects such as functional, psychosocial, or global HRQOL outcomes.

When PRO were used as secondary end points, the large majority of studies (74%) found that differences between treatment arms provided important additional information. However, inspection of higher-quality studies (summarised in Supplemental Table 1) also provides empirical evidence that, even when no major PRO differences are found between treatment arms, if PRO assessment is robustly performed, such patient-based outcomes can still be highly informative to comprehensively evaluate overall treatment effectiveness. Another important finding was that higher-quality PRO studies were generally associated with lower risk of bias RCTs (ie, with higher internal validity; Fig. 3). This finding might confirm the concept that well-designed trials also have well-designed PRO, and together the data can be used to inform practice.

Our study has limitations. It is possible that we might have missed some RCTs with a PRO component given our search strategy, although we did use a thorough search strategy. Another limitation is the exclusion of non–English-language published papers. However, previous evidence has shown that such omission would not significantly hamper conclusion of systematic reviews [39,40]. Also, our working definition of high-quality studies was based on methodological issues only, without an in-depth examination of the relevance for PRO inclusion in the specific RCT context. We thought that judging the relative importance of including a PRO assessment in a specific RCT over another would have been too subjective, and we thus assumed that the inclusion of a PRO component was equally important in all RCTs. We have, however, conducted a sensitivity analysis to examine the impact of tightening or relaxing slightly the cut-off used to define trials of robust quality. With a one point lower or higher than the one used in this analysis, we could have judged as “robust,” respectively, 17 (26%) or 11 (17%) in contrast to the 13 (20%) in the current work.

This work also has a number of strengths. Evaluation of the PRO methodological quality has been based on the highest quality standards developed by a large international panel of experts and endorsed by a major scientific society [19]. These criteria were also the basis for developing the recently published CONSORT PRO recommendations [23]. Also, unlike several other reviews in this area, we considered any study addressing PRO (rather than HRQOL outcomes only), thus providing a wider outlook in this field.

4. Conclusions

At least one-fifth of PRO RCTs in PCa have provided sufficient details to allow health policy makers and physicians to make a critical appraisal of results. Our work has shown that including well-designed PRO in RCTs of PCa patients is critical for better evaluating the treatment effectiveness of new therapeutic approaches. Improvements in key PRO quality reporting over time were also found, suggesting that methodological barriers to PRO implementation in RCTs are no longer so challenging as to hamper successful conduct of the study. High methodological rigor, however, is crucial to translating PRO research findings into information likely to affect clinical decision making. Investigators should note the methodological aspects that are most in need of improvement and thoughtfully plan and report future studies in PCa with a PRO component.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgement statement: The authors acknowledge Alessandro Perreca and Salvatore Soldati from the GIMEMA for their contribution to data management.

Funding/Support and role of the sponsor: This paper stems from a larger project (ie, Patient Reported Outcome Measurements Over Time In ONcology-PROMOTION Project), funded by a research grant from the EORTC Quality of Life Group, which reviewed and provided approval of the manuscript. Additional support for the conduct of the study was provided by the Italian Group for Adult Hematologic Diseases (GIMEMA).

Footnotes

Financial disclosures: Fabio Efficace certifies that all conflicts of interest, including specific financial interests and relationships and affiliations relevant to the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript (eg, employment/affiliation, grants or funding, consultancies, honoraria, stock ownership or options, expert testimony, royalties, or patents filed, received, or pending), are the following: Dr Blazeby is supported by the MRC ConDuCT Hub for Trials Methodology Research.

Author contributions: Fabio Efficace had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Study concept and design: Efficace, Fayers, Blazeby.

Acquisition of data: Efficace, Blazeby, Cafaro.

Analysis and interpretation of data: Efficace, Fayers, Blazeby, Pusic, Cafaro, Feuerstein, Eastham.

Drafting of the manuscript: Efficace, Fayers, Blazeby.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: Efficace, Fayers, Blazeby, Pusic, Cafaro, Fayers, Eastham.

Statistical analysis: Efficace.

Obtaining funding: Efficace.

Administrative, technical, or material support: Efficace, Fayers, Blazeby, Pusic, Cafaro, Feuerstein.

Supervision: Efficace.

Other (specify): None.

Appendix A. Supplementary data: Supplementary data associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.eururo.2013.10.017.

References

- 1.Boyle P, Levin B, editors. World Health Organization. World Cancer Report. Lyon, France: IARC Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Siegel R, Naishadham D, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2013. CA Cancer J Clin. 2013;63:11–30. doi: 10.3322/caac.21166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wolf AM, Wender RC, Etzioni RB, et al. American Cancer Society Prostate Cancer Advisory Committee. American Cancer Society guideline for the early detection of prostate cancer: update 2010. CA Cancer J Clin. 2010;60:70–98. doi: 10.3322/caac.20066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Singh J, Trabulsi EJ, Gomella LG. The quality-of-life impact of prostate cancer treatments. Curr Urol Rep. 2010;11:139–46. doi: 10.1007/s11934-010-0103-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.US Food and Drug Administration. Guidance for industry. Patient-reported outcome measures: use in medical product development to support labeling claims. US Department of Health and Human Services Food and Drug Administration Web site. http://www.fda.gov/downloads/Drugs/GuidanceComplianceRegulatoryInformation/Guidances/UCM193282.pdf. Updated December 2009.

- 6.Lipscomb J, Reeve BB, Clauser SB, et al. Patient-reported outcomes assessment in cancer trials: taking stock, moving forward. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:5133–40. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.12.4644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Efficace F, Bottomley A, van Andel G. Health related quality of life in prostate carcinoma patients: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Cancer. 2003;97:377–88. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Osoba D, Tannock IF, Ernst DS, Neville AJ. Health-related quality of life in men with metastatic prostate cancer treated with prednisone alone or mitoxantrone and prednisone. J Clin Oncol. 1999;17:1654–63. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1999.17.6.1654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tannock IF, Osoba D, Stockler MR, et al. Chemotherapy with mitoxantrone plus prednisone or prednisone alone for symptomatic hormone-resistant prostate cancer: a Canadian randomized trial with palliative end points. J Clin Oncol. 1996;14:1756–64. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1996.14.6.1756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Johnson JR, Williams G, Pazdur R. End points and United States Food and Drug Administration approval of oncology drugs. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:1404–11. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.08.072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Efficace F, Bottomley A, Osoba D, et al. Beyond the development of health-related quality-of-life (HRQOL) measures: a checklist for evaluating HRQOL outcomes in cancer clinical trials—does HRQOL evaluation in prostate cancer research inform clinical decision making? J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:3502–11. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.12.121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Basch E, Abernethy AP, Mullins CD, et al. Recommendations for incorporating patient-reported outcomes into clinical comparative effectiveness research in adult oncology. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:4249–55. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.42.5967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Basch E. Toward patient-centered drug development in oncology. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:397–400. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1114649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brundage M, Bass B, Davidson J, et al. Patterns of reporting health-related quality of life outcomes in randomized clinical trials: implications for clinicians and quality of life researchers. Qual Life Res. 2011;20:653–64. doi: 10.1007/s11136-010-9793-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Efficace F, Bottomley A, Vanvoorden V, Blazeby JM. Methodological issues in assessing health-related quality of life of colorectal cancer patients in randomised controlled trials. Eur J Cancer. 2004;40:187–97. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2003.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bottomley A, Efficace F, Thomas R, et al. Health-related quality of life in non-small-cell lung cancer: methodologic issues in randomized controlled trials. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:2982–92. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.01.203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Methodology Committee of the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI) Methodological standards and patient-centeredness in comparative effectiveness research: the PCORI perspective. JAMA. 2012;307:1636–40. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6:e1000097. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brundage M, Blazeby J, Revicki D, et al. Patient-reported outcomes in randomized clinical trials: development of ISOQOL reporting standards. Qual Life Res. 2013;22:1161–75. doi: 10.1007/s11136-012-0252-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Higgins JP, Altman DG, Gøtzsche PC, et al. Cochrane Bias Methods Group; Cochrane Statistical Methods Group. The Cochrane Collaboration's tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ. 2011;343:d5928. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d5928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Staquet M, Berzon R, Osoba D, Machin D. Guidelines for reporting results of quality of life assessments in clinical trials. Qual Life Res. 1996;5:496–502. doi: 10.1007/BF00540022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lee CW, Chi KN. The standard of reporting of health-related quality of life in clinical cancer trials. J Clin Epidemiol. 2000;53:451–8. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(99)00221-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Calvert M, Blazeby J, Altman DG, Revicki DA, Moher D, Brundage MD CONSORT PRO Group. Reporting of patient-reported outcomes in randomized trials: the CONSORT PRO extension. JAMA. 2013;309:814–22. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kvam AK, Fayers P, Hjermstad M, Gulbrandsen N, Wisloff F. Health-related quality of life assessment in randomised controlled trials in multiple myeloma: a critical review of methodology and impact on treatment recommendations. Eur J Haematol. 2009;83:279–89. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0609.2009.01303.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Moinpour CM, Hayden KA, Unger JM, et al. Southwest Oncology Group. Health-related quality of life results in pathologic stage C prostate cancer from a Southwest Oncology Group trial comparing radical prostatectomy alone with radical prostatectomy plus radiation therapy. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:112–20. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.10.4505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tannock IF, de Wit R, Berry WR, et al. TAX 327 Investigators. Docetaxel plus prednisone or mitoxantrone plus prednisone for advanced prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:1502–12. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa040720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Petrylak DP, Tangen CM, Hussain MH, et al. Docetaxel and estramustine compared with mitoxantrone and prednisone for advanced refractory prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:1513–20. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa041318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Armstrong AJ, Garrett-Mayer E, Ou Yang YC, et al. Prostate-specific antigen and pain surrogacy analysis in metastatic hormonerefractory prostate cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:3965–70. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.11.4769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Berthold DR, Pond GR, de Wit R, Eisenberger M, Tannock IF TAX 327 Investigators. Survival and PSA response of patients in the TAX 327 study who crossed over to receive docetaxel after mitoxantrone or vice versa. Ann Oncol. 2008;19:1749–53. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdn288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Berthold DR, Pond GR, Roessner M, de Wit R, Eisenberger M, Tannock AI TAX-327 Investigators. Treatment of hormone-refractory prostate cancer with docetaxel or mitoxantrone: relationships between prostate-specific antigen, pain, and quality of life response and survival in the TAX-327 study. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:2763–7. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-0944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Berthold DR, Pond GR, Soban F, de Wit R, Eisenberger M, Tannock IF. Docetaxel plus prednisone or mitoxantrone plus prednisone for advanced prostate cancer: updated survival in the TAX 327 study. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:242–5. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.12.4008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Southwest Oncology Group. Berry DL, Moinpour CM, et al. Quality of life and pain in advanced stage prostate cancer: results of a Southwest Oncology Group randomized trial comparing docetaxel and estramustine to mitoxantrone and prednisone. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:2828–35. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.04.8207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Warde P, Mason M, Ding K, et al. NCIC CTG PR.3/MRC UK PR07 investigators. Combined androgen deprivation therapy and radiation therapy for locally advanced prostate cancer: a randomised, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2011;378:2104–11. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61095-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fransson P, Lund JA, Damber JE, et al. Scandinavian Prostate Cancer Group Study 7; Swedish Association for Urological Oncology 3. Quality of life in patients with locally advanced prostate cancer given endocrine treatment with or without radiotherapy: 4-year follow-up of SPCG-7/SFUO-3, an open-label, randomised, phase III trial. Lancet Oncol. 2009;10:370–80. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(09)70027-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Thompson IM, Jr, Tangen CM, Paradelo J, et al. Adjuvant radiotherapy for pathologically advanced prostate cancer: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2006;296:2329–35. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.19.2329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fayers P, Hays R. Assessing quality of life in clinical trials. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fairclough DL, Peterson HF, Chang V. Why are missing quality of life data a problem in clinical trials of cancer therapy? Stat Med. 1998;17:667–77. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0258(19980315/15)17:5/7<667::aid-sim813>3.0.co;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cleeland CS. Symptom burden: multiple symptoms and their impact as patient-reported outcomes. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. 2007:16–21. doi: 10.1093/jncimonographs/lgm005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Moher D, Pham B, Klassen TP, et al. What contributions do languages other than English make on the results of meta-analyses? J Clin Epidemiol. 2000;53:964–72. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(00)00188-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jüni P, Holenstein F, Sterne J, Bartlett C, Egger M. Direction and impact of language bias in meta-analyses of controlled trials: empirical study. Int J Epidemiol. 2002;31:115–23. doi: 10.1093/ije/31.1.115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.