Abstract

Long QT syndrome (LQTS) is a genetically heterogeneous disorder associated with sequence variations in more than 10 genes; in some cases, it is caused by large deletions or duplications among the main, known LQTS-associated genes. Here, we describe a 14-month-old Korean boy with congenital hearing loss and prolonged QT interval whose condition was clinically diagnosed as Jervell and Lange-Nielsen syndrome (JLNS), a recessive form of LQTS. Genetic analyses using sequence analysis and multiplex ligation-dependent probe amplification (MLPA) assay revealed a large deletion spanning exons 7-10 as well as a frameshift mutation (c.1893dup; p.Arg632Glnfs*20). To our knowledge, this is the first report of a large deletion in KCNQ1 identified in JLNS patients. This case indicates that a method such as MLPA, which can identify large deletions or duplications needs to be considered in addition to sequence analysis to diagnose JLNS.

Keywords: Jervell and Lange-Nielsen syndrome, KCNQ1 mutation, Multiplex ligation-dependent probe amplification, Exon deletion

INTRODUCTION

Jervell and Lange-Nielsen syndrome (JLNS) is an autosomal recessive disorder associated with sensorineural hearing loss and long QTc, usually greater than 500 msec. Long QT syndrome (LQTS) manifests with episodes of syncope and is characterized by susceptibility to sudden death due to a specific type of polymorphic ventricular tachycardia, torsade de pointes [1]. Patients with JLNS have a more severe cardiac phenotype than those with Romano-Ward syndrome (RWS), an autosomal dominant inherited form of LQTS [2]. The prevalence of LQTS is estimated to be about 1 in 2,500 live births [3, 4]. Although it varies depending on the population studied, JLNS has been reported to affect about 3-5 in 1 million individuals, which represents less than 1% of all LQTS patients [5, 6, 7].

Among more than 10 genes responsible for LQTS, only 2 genes, KCNQ1 (LQTS1) and KCNE1 (LQTS5), are known to be associated with JLNS. About 90% cases of JLNS can be attributed to mutations in KCNQ1 [8, 9]. KCNQ1 contains 19 exons and spans more than 400 kb on chromosome 11p15.5 [10]. In addition to sequence variants, both deletions and duplications of KCNQ1 exon(s) are known to cause LQTS [11, 12]. However, their frequency is unknown. Because these deletions and duplications cannot be detected by sequence analysis, various other methods are used, e.g., quantitative PCR, long-range PCR, multiplex ligation-dependent probe amplification (MLPA), and chromosomal microarray analysis.

Here, we report compound heterozygous mutations in KCNQ1 in a child with JLNS who inherited a large gene deletion from his father and a frameshift mutation from his mother.

CASE REPORT

A 14-month-old boy with hearing loss visited the otolaryngology unit of the department of surgery; the electrocardiogram showed a prolonged QT interval with a QTc of 530 msec. He never experienced syncopal episodes, but his brother had a history of syncope while running in play. Otherwise, no other specific family history of LQTS was found. A Holter study showed neither T wave interruption nor Torsade de points. Treatment was immediately started with atenolol (β-adrenergic blocker), and genetic studies were performed on the patient and his family members (father, mother, and brother). The patient's father and mother showed normal echocardiograms with QTc values of 425 msec and 418 msec, respectively. However, the QT interval of the patient's brother was prolonged (QTc of 547 msec), but hearing loss was not observed.

After obtaining informed consent, we collected peripheral blood samples from the patient and his family. Whole blood was collected in standard EDTA tubes, and DNA was extracted by using the GentraPureGene blood kit (Gentra Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA) according to the manufacturer's instructions. PCR was performed by using primers specific for 16 coding exons of KCNQ1. The amplified products were sequenced on an ABI 3730 analyzer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) by using BigDye Terminator v3.1 Cycle sequencing kits (Applied Biosystems). Gross deletions and duplications in KCNQ1 were screened by the MLPA method, using the SALSA MLPA P114 Long-QT probe mix kit (MRC-Holland, Amsterdam, Netherlands).

The study was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the institutional ethics review board of the Seoul National University Hospital.

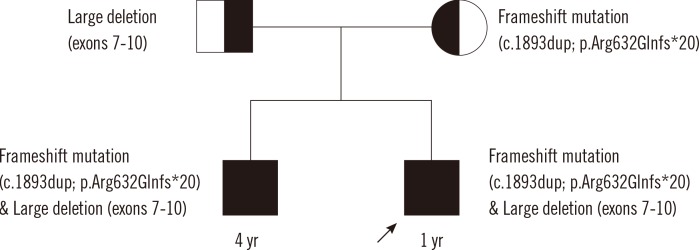

Genetic analysis revealed compound heterozygous mutations in KCNQ1 consisting of a large deletion (exons 7-10, c.922-?_c.1393+?del, reference sequence: NM_000218.2) and a frameshift mutation (c.1893dup; p.Arg632Glnfs*20) in the proband and his brother. The proband's father was heterozygous for the large deletion (exons 7-10) but did not carry the frameshift mutation, whereas the proband's mother was heterozygous for the frameshift mutation (c.1893dup; p.Arg632Glnfs*20) but neither exon deletions nor duplications were detected (Fig. 1 and 2).

Fig. 1.

Family pedigree. The older brother with a history of syncope and long QTc carries the same mutations as the proband (marked with arrow), i.e., large exon deletion and frameshift sequence mutation. Each mutation was inherited from one of the parents; the exon deletion from the father and the frameshift mutation from the mother.

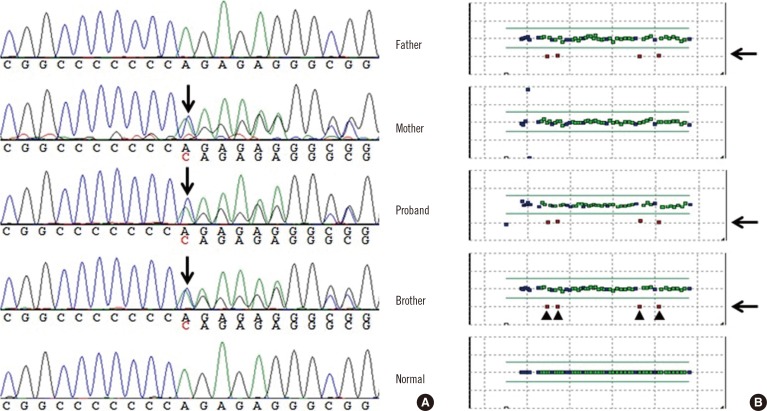

Fig. 2.

(A) Sequencing analysis revealed a frameshift mutation (c.1893dup; p.Arg632Glnfs*20) in the proband, his mother, and his brother. (B) On the basis of the result of multiplex ligation-dependent probe amplification, 4 exons (exons 9, 10, 7, and 8 in this order) with half the copy number were identified, indicating a large deletion in the proband, his father, and his brother.

DISCUSSION

Most of the symptomatic JLNS patients carry mutations in KCNQ1 and most of the asymptomatic patients carry KCNE1 mutations [9]. Among the mutations associated with JLNS, only a few cases with compound heterozygous mutations have been reported, all consisting of sequence mutations [5, 10, 13, 14]. Any large deletion or duplication in LQTS has been reported in RWS patients with mutation-negative cohorts by sequence analysis [12, 15, 16]. In our laboratory, this is the third case with a large deletion in KCNQ1 among patients whose conditions were clinically diagnosed as LQTS to date; however, the two previous cases were diagnosed as RWS (See supplemental data Table S1).

In general, although they are heterozygous for the same gene, patients with LQTS1 are significantly more symptomatic, whereas the parents of the JLNS patients are asymptomatic or mildly symptomatic. The most obvious explanation would be that JLNS mutations result in a less severe phenotype and, therefore, have a less pronounced effect in heterozygous carriers [9]. Most LQTS1 genetic variants are missense mutations that can co-assemble with normal subunits and interfere with channel functions, thereby exerting a negative effect [17, 18]. In contrast, frameshift/truncating mutations are responsible for the majority of JLNS cases [8]; these mutations cannot co-assemble with normal subunits and are unable to cause dominant-negative suppression under normal circumstances [2]. The frameshift mutation (c.1893dup; p.Arg632Glnfs*20) leads to a premature stop codon and is predicted to produce a truncated protein [10]. When this mutation was first identified as a novel mutation in a RWS family, the proband experienced several stress-induced syncopes since the age of 3 yr, but her affected father was asymptomatic [10]. However, homozygous/compound heterozygous JLNS is the most severe form among the major variants of LQTS [9], and the efficacy of β-blockers is very limited [19].

Of the 249 KCNQ1-positive patients included in a study that was performed at the Mayo Clinic, 15 patients (6.0%) carried mutations on both KCNQ1 alleles; furthermore,11 of these double-KCNQ1-positive individuals (73%) presented without sensorineural deafness/hearing loss typically associated with JLNS and, thus, are best defined as autosomal recessive form of LQT1 [20]. Moreover, this result implies that the incidence of the autosomal recessive form of LQT1 in the absence of an auditory phenotype may be higher than previously anticipated and that these cases should be treated as a higher-risk LQTS subset similar to their JLNS counterparts [20]. Therefore, appropriate molecular diagnostic methods are needed to differentiate the autosomal recessive form of LQT1 from autosomal dominant RWS. In addition, it is important to perform molecular screening to identify carriers and counsel on the possibility of transmitting the mutation to children who are at possible risk of being homozygous and, consequently, developing a severe phenotype that may be lethal [21]. Molecular testing of LQTS is based mostly on sequence analysis and regardless of whether sequence mutations are detected or not, additional deletion and duplication analysis should be considered.

To our knowledge, this is the first report of a large deletion in KCNQ1 identified in JLNS patients. The present case suggests that a testing method such as MLPA, which can identify large deletions or duplications needs to be considered in addition to sequence analysis to diagnose JLNS.

Acknowledgment

This study was supported by the Basic Science Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea funded by the Ministry of Education, Science, and Technology (NRF-2013R1A1A2011551).

Footnotes

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

Supplementary Material

References

- 1.Kannankeril P, Fish F. Disorders of cardiac rhythm and conduction. In: Allen HD, Driscoll DJ, Shaddy RE, Feltes TF, editors. Moss and Adams' heart disease in infants, children, and adolescents including the fetus and youngadult. 7th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2008. pp. 293–341. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baek JS, Bae EJ, Lee SY, Park SS, Kim SY, Jung KN, et al. Jervell and Lange-Nielsen syndrome: novel compound heterozygous mutations in the KCNQ1 in a Korean family. J Korean Med Sci. 2010;25:1522–1525. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2010.25.10.1522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kanovsky J, Novotny T, Kadlecova J, Gaillyova R. A new homozygous mutation of the KCNQ1 gene associated with both Romano-Ward and incomplete Jervell Lange-Nielsen syndromes in two sisters. Heart Rhythm. 2010;7:531–533. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2009.11.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kaltenbach S, Capri Y, Rossignol S, Denjoy I, Soudée S, Aboura A, et al. Beckwith-Wiedemann syndrome and long QT syndrome due to familial-balanced translocation t(11;17)(p15.5;q21.3) involving the KCNQ1 gene. Clin Genet. 2013;84:78–81. doi: 10.1111/cge.12038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tranebjaerg L, Bathen J, Tyson J, Bitner-Glindzicz M. Jervell and Lange-Nielsen syndrome: a Norwegian perspective. Am J Med Genet. 1999;89:137–146. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Goldenberg I, Moss AJ, Zareba W, McNitt S, Robinson JL, Qi M, et al. Clinical course and risk stratification of patients affected with the Jervell and Lange-Nielsen syndrome. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2006;17:1161–1168. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8167.2006.00587.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Winbo A, Stattin EL, Diamant UB, Persson J, Jensen SM, Rydberg A. Prevalence, mutation spectrum, and cardiac phenotype of the Jervell and Lange-Nielsen syndrome in Sweden. Europace. 2012;14:1799–1806. doi: 10.1093/europace/eus111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tyson J, Tranebjaerg L, McEntagart M, Larsen LA, Christiansen M, Whiteford ML, et al. Mutational spectrum in the cardioauditory syndrome of Jervell and Lange-Nielsen. Hum Genet. 2000;107:499–503. doi: 10.1007/s004390000402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schwartz PJ, Spazzolini C, Crotti L, Bathen J, Amlie JP, Timothy K, et al. The Jervell and Lange-Nielsen syndrome: natural history, molecular basis, and clinical outcome. Circulation. 2006;113:783–790. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.592899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Neyroud N, Richard P, Vignier N, Donger C, Denjoy I, Demay L, et al. Genomic organization of the KCNQ1 K+ channel gene and identification of C-terminal mutations in the long-QT syndrome. Circ Res. 1999;84:290–297. doi: 10.1161/01.res.84.3.290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zehelein J, Kathoefer S, Khalil M, Alter M, Thomas D, Brockmeier K, et al. Skipping of Exon 1 in the KCNQ1 gene causes Jervell and Lange-Nielsen syndrome. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:35397–35403. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M603433200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Eddy CA, MacCormick JM, Chung SK, Crawford JR, Love DR, Rees MI, et al. Identification of large gene deletions and duplications in KCNQ1 and KCNH2 in patients with long QT syndrome. Heart Rhythm. 2008;5:1275–1281. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2008.05.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang Z, Li H, Moss AJ, Robinson J, Zareba W, Knilans T, et al. Compound heterozygous mutations in KvLQT1 cause Jervell and Lange-Nielsen syndrome. Mol Genet Metab. 2002;75:308–316. doi: 10.1016/S1096-7192(02)00007-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ning L, Moss AJ, Zareba W, Robinson J, Rosero S, Ryan D, et al. Novel compound heterozygous mutations in the KCNQ1 gene associated with autosomal recessive long QT syndrome (Jervell and Lange-Nielsen syndrome) Ann Noninvasive Electrocardiol. 2003;8:246–250. doi: 10.1046/j.1542-474X.2003.08313.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tester DJ, Benton AJ, Train L, Deal B, Baudhuin LM, Ackerman MJ. Prevalence and spectrum of large deletions or duplications in the major long QT syndrome-susceptibility genes and implications for long QT syndrome genetic testing. Am J Cardiol. 2010;106:1124–1128. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2010.06.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Barc J, Briec F, Schmitt S, Kyndt F, Le Cunff M, Baron E, et al. Screening for copy number variation in genes associated with the long QT syndrome: clinical relevance. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;57:40–47. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2010.08.621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Splawski I, Shen J, Timothy KW, Lehmann MH, Priori S, Robinson JL, et al. Spectrum of mutations in long-QT syndrome genes. KVLQT1, HERG, SCN5A, KCNE1, and KCNE2. Circulation. 2000;102:1178–1185. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.102.10.1178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tester DJ, Will ML, Haglund CM, Ackerman MJ. Compendium of cardiac channel mutations in 541 consecutive unrelated patients referred for long QT syndrome genetic testing. Heart Rhythm. 2005;2:507–517. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2005.01.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Richter S, Brugada P. Risk-stratifying Jervell and Lange-Nielsen syndrome from clinical data. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2006;17:1169–1171. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8167.2006.00613.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Giudicessi JR, Ackerman MJ. Prevalence and potential genetic determinants of sensorineural deafness in KCNQ1 homozygosity and compound heterozygosity. Circ Cardiovasc Genet. 2013;6:193–200. doi: 10.1161/CIRCGENETICS.112.964684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shinwari Z, Al-Hazzani A, Dzimiri N, Tulbah S, Mallawi Y, Al-Fayyadh M, et al. Identification of a novel KCNQ1 mutation in a large Saudi family with long QT syndrome: clinical consequences and preventive implications. Clin Genet. 2013;83:370–374. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.2012.01914.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.