Abstract

If O2 is available at circumneutral pH, Fe2+ is rapidly oxidized to Fe3+, which precipitates as FeO(OH). Neutrophilic iron oxidizing bacteria have evolved mechanisms to prevent self-encrustation in iron. Hitherto, no mechanism has been proposed for cyanobacteria from Fe2+-rich environments; these produce O2 but are seldom found encrusted in iron. We used two sets of illuminated reactors connected to two groundwater aquifers with different Fe2+ concentrations (0.9 μM vs. 26 μM) in the Äspö Hard Rock Laboratory (HRL), Sweden. Cyanobacterial biofilms developed in all reactors and were phylogenetically different between the reactors. Unexpectedly, cyanobacteria growing in the Fe2+-poor reactors were encrusted in iron, whereas those in the Fe2+-rich reactors were not. In-situ microsensor measurements showed that O2 concentrations and pH near the surface of the cyanobacterial biofilms from the Fe2+-rich reactors were much higher than in the overlying water. This was not the case for the biofilms growing at low Fe2+ concentrations. Measurements with enrichment cultures showed that cyanobacteria from the Fe2+-rich environment increased their photosynthesis with increasing Fe2+ concentrations, whereas those from the low Fe2+ environment were inhibited at Fe2+ > 5 μM. Modeling based on in-situ O2 and pH profiles showed that cyanobacteria from the Fe2+-rich reactor were not exposed to significant Fe2+ concentrations. We propose that, due to limited mass transfer, high photosynthetic activity in Fe2+-rich environments forms a protective zone where Fe2+ precipitates abiotically at a non-lethal distance from the cyanobacteria. This mechanism sheds new light on the possible role of cyanobacteria in precipitation of banded iron formations.

Keywords: oxygenic phototrophs, Cyanobacteria, Fe(II), iron-encrustation, banded iron formations, oxygen microgradients, pH microgradients

Introduction

Abiotic oxidation of Fe2+ to Fe3+ and subsequent precipitation of FeO(OH) is a function of pH and O2 concentration, and is relatively rapid when O2 is available at circumneutral pH (Khalil et al., 2011). To prevent iron self-encrustation, iron oxidizing bacteria developed a variety of protection mechanisms, including formation of organic matter stalks (Chan et al., 2009; Suzuki et al., 2011) or sheaths (Van Veen et al., 1978) that provide a template for FeO(OH) nucleation. For some phototrophic iron oxidizers, a low-pH microenvironment generated by the cell's proton pumps has been suggested as a mechanism preventing iron self-encrustation (Hegler et al., 2010). Additional adaptations include a hydrophilic cell membrane with a near neutral surface charge to prevent the adhesion of Fe2+/Fe3+ (Saini and Chan, 2013).

Oxygenic phototrophs are often found in microbial mats in Fe2+-rich environments (Pierson et al., 1999; Brown et al., 2005, 2010; Wieland et al., 2005). It is known that when the photosynthetically active cells are densely packed in a volume where transport is limited by diffusion (e.g., in photosynthetic biofilms or mats), their activity leads to a locally increased pH and O2 concentration (Pierson et al., 1999; Wieland et al., 2005), which should favor locally higher rates of Fe2+ oxidation and precipitation. Yet, oxygenic phototrophs in Fe2+-rich environments have seldom been found encrusted in precipitated iron (Pierson and Parenteau, 2000). A defense mechanism against iron self-encrustation that would enable oxygenic phototrophs to thrive in Fe2+-rich environments has hitherto not been suggested. Although cyanobacteria that accumulate iron precipitates intracellularly were described from Yellowstone National Park (Brown et al., 2010), this phenomenon has not been found elsewhere.

In the Fe2+-rich environment of the Äspö Hard Rock Laboratory (HRL), Sweden, which is a man-made research tunnel, a series of flow-through reactors were set up in 2006 as part of a study on iron oxidizing bacteria (Ionescu et al., 2014a). Part of the reactors were connected to two aquifers that emerge from the tunnel wall at the top and bottom of the tunnel and differ markedly with respect to concentrations of dissolved Fe2+ (top: ~26 μM, bottom: ~0.9 μM). Half of the reactors were illuminated and the other half were not. After four years of undisturbed incubation, we found that inside the illuminated reactors cyanobacterial biofilms developed. Interestingly, cyanobacteria in the Fe2+-poor reactors were mostly encrusted in iron precipitates, whereas those from the Fe+2-rich reactors were not.

In this study we aimed to understand this counter-intuitive observation. Past studies showed that only some morphotypes of cyanobacteria are found encrusted in iron (Pierson and Parenteau, 2000; Parenteau and Cady, 2010) while others are not; however a mechanism to account for these differences was not suggested. Pierson et al. (1999) showed that cyanobacterial mats from iron rich environments were characterized by high photosynthetic O2 production, which was similar to our observation in the cyanobacterial biofilms growing in the Fe2+-rich reactors. Hence, we hypothesized that it is the high rate of oxygenic photosynthesis that allows cyanobacterial proliferation in the Fe2+-rich environment of the Äspö HRL. Specifically, due to mass transfer limitations, cyanobacterial photosynthesis creates a microenvironment with elevated O2 concentrations and pH that causes high rates of Fe2+ oxidation and precipitation at a non-lethal distance from the cells and thus prevents their iron self-encrustation.

Materials and methods

Reactors

The Äspö HRL is a man-made research tunnel (length 3.6 km) operated since 1995 by the Swedish Nuclear Waste Management Facility (SKB) in the south-east of Sweden. The tunnel intersects several groundwater aquifers, each characterized by specific water chemistry (Laaksoharju et al., 1999; Ionescu et al., 2014a). In 2006 two sets of two illuminated reactors were connected directly to the aquifers at sites TASF (depth 460 m) and TASA-1327B (depth 185 m) using valves KF0069A01 and HA1327B, respectively. Only chemically inert materials such as polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE, Teflon®), PTFE-fiber glass, fluorinatedethylene propylene (FEP) and special PTFE-foam were used as construction materials to avoid biological contamination from the surrounding environment and chemical contamination from glass- and plastic-ware. The reactors and connection tubing were sterilized with ethanol (70%, overnight) before underground installation. In each set, reactor 1 (R1) had an air headspace and gas exchange was allowed through a 0.2 μm membrane filter. Reactor 2 (R2) did not have an air headspace, which was achieved by elevating the outflow pipe above the height of the reactor. Both reactors were illuminated using two fluorescent lamps (WL11, Brennenstuhl, Tübingen, Germany; Figure S1). Light penetrated inside the reactors through an FEP-window in the center of the lid. Irradiance behind the window was 60 μmol photons m−2 s−1, as determined by a quantum irradiance sensor (LI-190 Quantum) connected to a light meter (LI-250, both from LI-COR Biosciences).

DNA extraction and sequencing

To characterize the composition of the cyanobacterial communities developed in the reactors, DNA was extracted as previously described (Ionescu et al., 2012). Pyrosequencing was done by MrDNA laboratories (Shallowater, TX) using general bacterial primers 27F and 519R (Lane, 1991). Sequences were analyzed using the SILVA NGS pipeline (Ionescu et al., 2012) and the SILVA 111 database (Quast et al., 2012).

Culturing

Green cyanobacterial biomass that developed in the aerated Fe2+-poor (TASF-R1) and aerated/non-aerated Fe2+-rich (1327-R1/R2) reactors was physically separated from the rusty-orange biomass of iron oxidizing bacteria and transferred on site to sterile BG-11 medium (Rippka et al., 1979). Upon arrival to the laboratory the samples were transferred to both solid and liquid BG-11 medium and grown in constant light (irradiance 60–70 μmol photons m−2 s−1) at 15°C to provide light and temperature conditions close to those in their natural habitat. To allow for later microsensor measurements (see below) without the loss of added iron, cultures were allowed to grow on GF/F filters (Whatmann, diameter 47 mm) that were soaked in Fe2+-free media and placed on top of pre-grown BG-11 (Fe2+-free) agar plates. Filters were used once the green cyanobacterial biomass was visible.

Microsensor measurements

Dissolved O2 concentration was measured with a fast-responding Clark-type microelectrode (tip diameter ~30 μm). pH was measured using shielded liquid ion exchange glass microelectrodes. Both microsensors were constructed and calibrated as previously described (Revsbech, 1989; de Beer and Stambler, 2000). In-situ measurements were conducted either directly in the reactors or, if not possible, directly next to them, placing the biofilms in water from the respective reactor. Illumination during all experiments was provided by a Schott KL1500 lamp (Carl Zeiss AG, Göttingen, Germany), with the incident irradiance adjusted to match the value inside the reactors (60 μmol photons m−2 s−1).

For laboratory measurements 0.5 cm filter stripes with a well-developed cyanobacterial biomass were placed in an equally wide flow-through chamber (volume ~5 mL) connected to a media reservoir using a peristaltic pump (Figure S2). The medium was continuously purged with N2 gas to maintain anoxic conditions. During measurements, Fe2+ was added to the media reservoir while subsamples for iron determination were periodically taken from the chamber to assure the required concentration (1, 5, 10, 30, 50 μM) is maintained. Iron was added from an acidic Fe(II)Ammonium Sulfate stock solution resulting in a slight acidification of the medium (<0.2 pH units). Used medium was not recycled.

A similar iron addition experiment was performed also in-situ using a biofilm collected from the aerated Fe2+-poor reactor (TASF-R1). The sample was placed in a 1 L beaker and covered with water from the same reactor. The water was purged with N2 and iron was added to a final concentration of 25 μM.

In all experiments Fe2+ was measured colorimetrically using ferrozine as previously described (Riemer et al., 2004).

NanoSIMS measurements

To test whether iron oxides are being precipitated inside cyanobacterial filaments in a similar way as described by Brown et al. (2010), 57Fe2+ was added to a culture from the non-aerated Fe2+-rich reactor at a concentration of 50 μM. Samples were transferred to polycarbonate filters and cyanobacterial filaments were identified using auto-fluorescence. Areas that contained the filaments were marked by a laser dissection microscope (LMD7000, Leica), which allowed their later localization and identification in the nanoSIMS instrument using the built-in CCD camera. NanoSIMS analysis was performed with the nanoSIMS 50 L instrument (Cameca) available at the MPI Bremen. Before each analysis the sample was pre-sputtered with a Cs+ primary ion beam (16 keV, 1.1–3.5 pA) focused on a spot of ~120 nm diameter for 60–90 s. Subsequently, the same beam was scanned over the sample in a 256 × 256 pixel raster with a counting time of 1 ms per pixel, and the following ions were detected: 12C−, 12C14N−, 32S−, 56Fe16O−, and 57Fe16O−. The mass resolution power during all measurements was >8000. For each region of interest 30–100 planes were acquired at a raster size of 15 × 15 or 30 × 30 μm. Data analysis was done with the Look@NanoSIMS software (Polerecky et al., 2012). As a control of the method, the same 57Fe2+-addition experiment and nanoSIMS analysis were performed using samples from mats of iron oxidizing bacteria.

Fe2+ profile modeling

Depth profiles of Fe2+ concentrations around the biofilm surface could not be measured and were therefore modeled numerically. First, a depth profile of Fe2+ oxidation rates was calculated according to Morgan and Lahav (2007) based on the profile of O2 concentrations and pH measured in-situ. Subsequently, these rates were used to calculate the evolution of the Fe2+ concentration profile, starting from a flat profile (i.e., Fe2+ concentrations in the entire modeled domain equal to that measured in the reactor water). Specifically, during each time-step, the net decrease in the Fe2+ concentration at a given depth was the result of the local Fe2+ oxidation rate combined with the transport by diffusion determined from the Fe2+ concentrations above and below. Fe2+ concentrations at distances greater than the thickness of the diffusive boundary layer (DBL) were kept constant and equal to the initial concentrations during the entire calculation. DBL thickness was derived from the measured O2 profile. Calculation proceeded in time-steps of 1 × 10−3 s until a steady state was reached. Steady state was defined when the changes in Fe2+ concentration across the entire profile fell below 10−6 μM. Equilibrium constants required for the iron speciation were corrected for the ionic strength and temperature of the specific feeding aquifer using the Davies (Davies, 1962) and Van't Hoff (Atkins, 1978) equations, respectively. Ionic strength of the different waters was calculated using Visual MINTEQ (Ver. 3.0). Iron diffusion coefficient was set to 5.82 × 10−6 cm2 s−1 (Yuan-Hui and Gregory, 1974). As no pH profile was available from the aerated Fe2+-rich reactor, modeling was done only for biofilms from the non-aerated Fe2+-rich and aerated Fe2+-poor reactors.

Results

Water chemistry

Water in the top aquifer is mainly influenced by the Baltic Sea and recent meteoric water and has a retention time in the bedrock of several weeks (Laaksoharju et al., 1999). It is rich in dissolved Fe2+ (around 26 μM) and has pH of 7.4 and O2 concentrations of about 2 μM. In contrast, water in the bottom aquifer is a mixture of glacial, ancient marine and brine water and was dated to the Boreal age (SICADA, SKB Database). It has markedly lower Fe2+ concentrations (0.9 μM), higher pH (8), and O2 concentrations of about 4 μM. Other notable differences include dissolved inorganic carbon (DIC), total alkalinity (Alk), and total dissolved salt (TDS) concentrations, which are about 10- and 100-fold lower and 5-fold higher in the bottom aquifer, respectively (Table 1).

Table 1.

Physico-chemical characteristics of the different aquifers connected to the reactors.

| Site | Sampled water | pH | T °C | Fe2+ μM | O2 μM | Alk μM | DIC μM C | DOC μM C | TDS μM C | H2S μM | NH4 μM | NO3 μM |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TASF (Fe2+-poor) | Aquifer | 7.98 | 12 | 0.89 | 3.7 | 110 | 133 | 183 | 23.6 | 0.53 | 0.61 | 1.05 |

| R1# | 7.94 | 12 | 0.89 | 32.5 | 110 | 133 | 167 | 23.5 | 0.53 | 0.67 | 1.03 | |

| TASA (1327B Fe2+-rich) | Aquifer | 7.41 | 15 | 25.8 | 2.2 | 3277 | 1691 | 492 | 5.1 | 1.88 | 215 | 0.12 |

| R1# | 7.40 | 15 | 27.1 | 7.2 | 3277 | 1933 | 617 | 5.1 | 1.17 | 217 | 1.15 | |

| R2# | 7.39 | 15 | 26.4 | 3.9 | 3245 | 1825 | 558 | 4.9 | 0.88 | 212 | 1.48 |

R1 and R2 are aerated and non-aerated flow reactors, respectively.

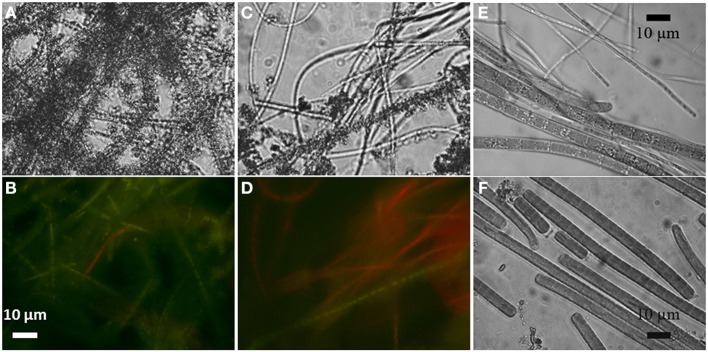

In-situ biomass

Filamentous cyanobacteria in the aerated reactors connected to the Fe2+-poor aquifer formed veil-like biofilms (2–3 cm long, 2–3 mm thick) that slowly but continuously moved due to the slow water flow in the reactor. Their pale-green color coincided with a low chlorophyll a (Chl a) concentration (0.2 μg Chl a mg−1 wet weight) and thus presumably low cyanobacterial biomass. Microscopic observations of biofilm subsamples revealed clear iron encrustation and largely diminished auto-fluorescence of the filaments (Figures 1A,B). Upon addition of 0.3 M oxalic acid, most of the Fe-oxide crystals dissolved and the red auto-fluorescence induced by green light, which is typical for cyanobacteria due to their Chl a and phycocyanin content, significantly increased (Figures 1C,D). Due to an extremely low biomass, biofilms from the non-aerated reactor from the Fe2+-poor site were not studied.

Figure 1.

Light (A) and autofluorescence (B) microscopic images of iron-encrusted cyanobacterial filaments from the aerated Fe2+-poor reactor. Upon treatment with 0.3 M oxalic acid most of the Fe crystals dissolved (C) and the natural red autofluorescence induced by green light resumed (D). Filaments from the aerated (E) and non-aerated (F) Fe2+-rich reactors were not found encrusted.

Cyanobacterial biofilms in the reactors connected to the Fe2+-rich aquifer had about 10-fold larger biomass (3.2 μg Chl a mg−1 wet weight), consistent with their dark-green appearance. Biofilms in the aerated reactor were 0.5–1 mm thick, floated atop of black decaying material (2–3 cm thick) and were in direct contact with air in the reactor (but still moist). In contrast, cyanobacterial biofilms in the non-aerated reactor were submersed, about 0.3 mm thick, and covered thick mats of iron oxidizing bacteria, the latter identified based on their rusty-orange appearance and an in-depth community analysis performed earlier (Ionescu et al., 2014a). Importantly, no signs of iron encrustation were observed for the cyanobacteria from these two reactors (Figures 1E,F).

Cyanobacterial community

Phylogenetic comparison based on the gene for the 16S rRNA revealed that the cyanobacterial communities significantly differed between the reactors from the Fe2+-rich and Fe2+-poor sites (Figure S3). Communities from the aerated and non-aerated reactors from the Fe2+-rich site were more diverse, clustering with sequences of Geitlerinema, Pseudanabaena, and several different clusters of Leptolyngbia. Many sequences from these reactors were shared. In contrast, cyanobacterial sequences from the aerated reactor from the Fe2+-poor site were unique, forming a cluster within the clade of Leptolyngbia (Figure S3). No sequences from any of the sampled reactors were closely related with the known ferro-philic cyanobacteria Chroogloeocystis siderophila. Sequences of cyanobacterial enrichment cultures from the respective reactors clustered in close proximity to those obtained from in-situ samples. One of these sequences was closely related to Oscillatoria JSC-1, a cyanobacterial strain known to precipitate iron internally (Brown et al., 2010).

Clustering of the sequences at 98% similarity cutoff using the CDHIT-EST software(Huang et al., 2010; Fu et al., 2012) supports the phylogenetic tree and shows that no overlap is found between sequences from the Fe2+-poor and the Fe2+-rich reactors. In contrast, sequences from the Fe2+-rich aerated and non-aerated reactors form individual as well as shared clusters (data not shown).

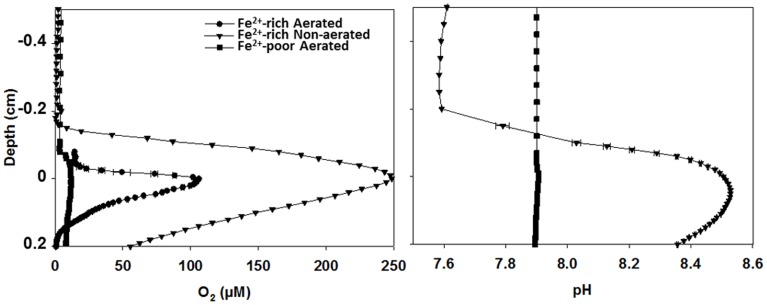

O2 and pH microsensor measurements

In-situ microsensor measurements revealed high volumetric rates of oxygenic photosynthesis in the biofilms forming in the Fe2+-rich reactors. This was demonstrated by the steep gradients in O2 and pH around the biofilm-water interface (Figure 2) as well as by direct rate measurements using the light-dark-shift method of Revsbech and Jorgensen (1981) (Figure S4). In contrast, O2 and pH profiles had only minute peaks in the biofilms in the Fe2+-poor reactor (Figure 2), indicating very low rates of photosynthesis. Based on the measured O2 profiles, the estimated net areal rates of photosynthesis were 21–23 and 1.5–5 μmol m−2 s−1 in the biofilms from the Fe2+-rich and Fe2+-poor reactors, respectively. This pattern was consistent with the approximately 10-fold difference in the cyanobacterial biomass (see above).

Figure 2.

In-situ O2 and pH microprofiles in cyanobacterial biofilms from aerated and non-aerated Fe2+-rich and aerated Fe2+-poor reactors. All profiles were measured under similar irradiance as that used during long-term incubations of the reactors. Measurements in the biofilm from the aerated Fe2+-poor reactor were conducted outside of the reactor using the natural water purged with N2 gas to maintain anoxic conditions.

We used freshly collected subsamples of the biofilms from the Fe2+-poor reactor to test the response of their photosynthesis to the addition of Fe2+ at a concentration comparable to that found in the Fe2+-rich reactors. We found that the photosynthetic O2 production started to decrease within minutes after the increase of the Fe2+ concentration to 25 μM and was close to zero after about an hour (Figure S5).

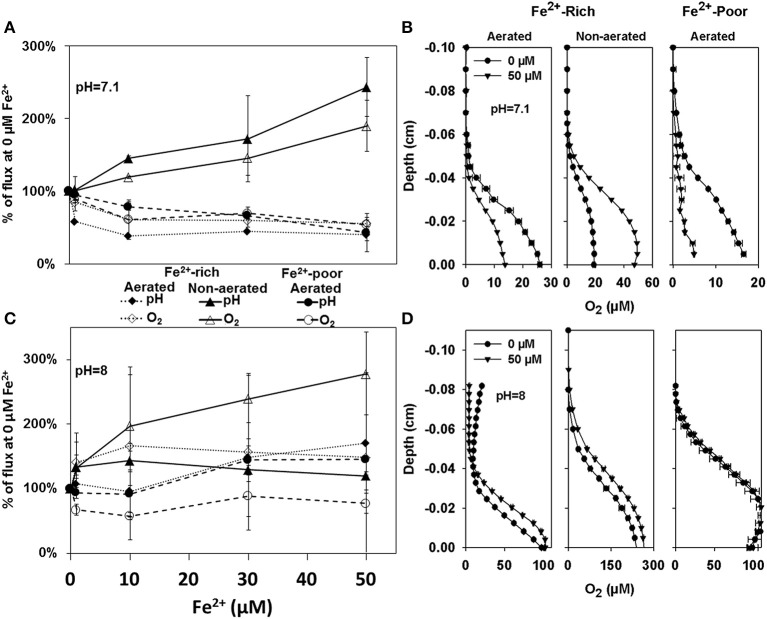

In addition to in-situ measurements, we conducted laboratory microsensor measurements to characterize the response of photosynthesis to increased Fe2+ concentrations in biofilms prepared from the cyanobacterial enrichment cultures obtained from the two reactor types. When the bulk pH was 7.1, the addition of up to 50 μM Fe2+ stimulated net O2 production in the enrichment cultures from the non-aerated Fe2+-rich reactor (Figure 3A — open triangles; Spearman correlation coefficient ρ = 0.952, p = 2 × 10−7), suggesting stimulation of photosynthetic activity by Fe2+. This was consistent with the observed increase in pH gradients at the biofilm-medium interface (Figure 3A, filled triangles; ρ = 0.854, p = 2 × 10−7). In contrast, increasing Fe2+ lead to a decrease in both O2 fluxes and pH gradients in biofilms prepared from the enrichment cultures from the aerated Fe2+-rich (O2: ρ = −0.686, p = 7.45 × 10−4; pH: ρ = −0.741, p = 0.011) and Fe2+-poor reactor (O2: ρ = −0.865, p = 2 × 10−7; pH: ρ = −0.986, p = 2 × 10−7), with the largest part of this decrease occurring for Fe2+ concentrations between 1 and 10 μM (Figures 3A,B). Analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) revealed that the slope of the regression line for the culture enriched from the non-aerated Fe2+-rich reactor was significantly greater than that for the enrichment cultures from the aerated Fe2+-rich and aerated Fe2+-poor reactors (p = 2 × 10−9), whereas the latter two were not significantly different (p = 0.97).

Figure 3.

Percent change in O2 fluxes and pH gradients calculated from microprofiles measured in cyanobacterial biofilms grown from enrichment cultures from the Fe2+-rich and Fe2+-poor reactors at pH 7 (A) and pH 8 (C). The shown fluxes are averaged measurements in 3 different biofilms with 3–4 steady state profiles each. Example of profiles from which these fluxes were calculated are shown in (B,D), respectively. Depth zero corresponds to the biofilm surface.

When the same experiments were performed at bulk medium pH of 8, net O2 production was again significantly stimulated by Fe2+ in the biofilm cultures from the non-aerated Fe2+ reactor (ρ = 0.716; p = 0.015), while no significant inhibition was observed in the biofilms from the aerated Fe2+-rich (ρ = 0.543; p = 0.097) and aerated Fe2+-poor (ρ = −0.123; p = 0.707) reactors (Figures 3C,D). However, due to the high variability in the results, the slopes of the regression lines for the three biofilm types were not significantly different (ANCOVA, p = 0.079). Also, there was no significant difference in the slopes determined at pH 7.1 and 8 in the biofilm cultures from the Fe2+-rich reactors (ANCOVA, aerated p = 0.20; non-aerated p = 0.26).

Importantly, no encrustation in iron minerals was observed in any (pH 7.1 or pH 8.0) of these experiments.

NanoSIMS measurements

No iron precipitates could be detected in or nearby the cyanobacterial filaments from the non-aerated Fe2+-rich reactor which were incubated with 57Fe2+ (Figures S6A,B). This is in contrast to control experiments conducted with samples from mats of iron oxidizing bacteria where some cells were clearly enriched in 57Fe precipitates as compared to the surrounding (Figures S6C,D; see also Ionescu et al., 2014b).

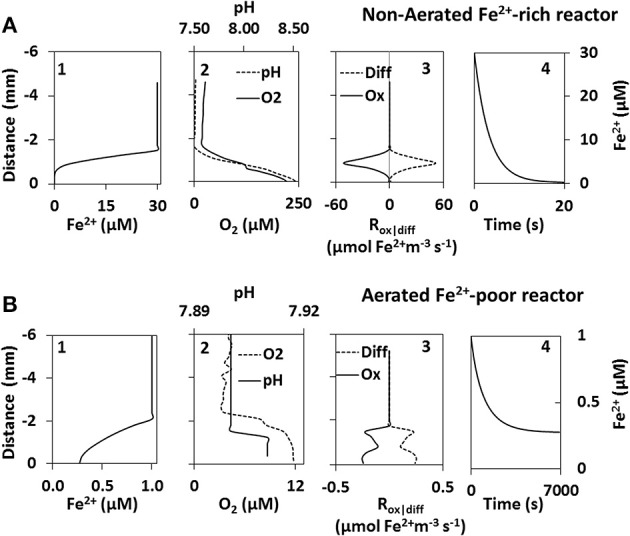

Fe2+ profile modeling

Modeling in the non-aerated Fe2+-rich reactor revealed that the steady state Fe2+ concentration profile was reached in ~10 min. Fe2+ concentration at the biofilm surface decreased from the initial value of 30 μM to below 0.001 μM in about 20 s, and in the steady state the Fe2+ concentration was below 0.001 μM already at a distance of ~400 μm from the biofilm surface (Figure 4A). In contrast, in the aerated Fe2+-poor reactor the steady state was reached after a much longer time (~2 h) and the concentration at the biofilm surface did not decrease below 0.3 μM (Figure 4B).

Figure 4.

Fe2+ model results of the non-aerated Fe2+-rich (A) and aerated Fe2+-poor (B) reactors. Steady state Fe2+ profiles above cyanobacteria biofilms (graph 1) were calculated using microprofiles of O2 and pH measured in-situ (graph 2). Steady state was achieved once Fe2+ consumption by abiotic oxidation (Ox) was equal to Fe2+ supplied by diffusion (Diff) (graph 3). The change in Fe2+ concentration at the biofilm surface is shown as a function of time (graph 4).

Discussion

The role of cyanobacterial oxygenic photosynthesis has been extensively discussed in relation to Fe(III) mineral formation during early Earth (Cloud, 1973; Lewy, 2012). However, the effects of O2 production in the presence of high ferrous iron concentrations have been only seldom discussed on the scale relevant for the microenvironment of the cyanobacteria (~100 μm or less) (Pierson and Parenteau, 2000). Our finding of iron-encrusted cyanobacteria at low Fe2+ concentrations as compared to naked filaments at high Fe2+ concentrations has raised three intriguing questions: (1) Why do we see iron-encrusted filaments specifically in the environment with the lower Fe2+? (2) How do oxygenic phototrophs, who by their means of existence form environmental conditions favoring Fe precipitation, avoid encrustation? (3) How do these organisms avoid Fe2+ toxicity?

Cyanobacteria are regarded as oxygenic phototrophs, yet a large number of species possess the ability to switch to anoxygenic phototrophy in the presence of sulfide (Cohen et al., 1986; Oren et al., 2005). Therefore, one possible way for photosynthetic cyanobacteria to avoid iron encrustation in Fe2+-rich environments could be by performing anoxygenic photosynthesis utilizing H2S (detected in the reactors) as the electron donor, which does not lead to O2 production. Alternatively, it was suggested that cyanobacteria could also use Fe2+ as an electron donor in the process of anoxygenic photosynthesis (Olson, 2006). Such cyanobacteria have, however, not been described yet. If such a mechanism exists, it is not clear where would the oxidized Fe be deposited, as the analogous sulfide oxidizing phototrophs can deposit elemental sulfur both internally (Arunasri et al., 2005) and externally (Ventura et al., 2000).

With this background knowledge, we initially hypothesized that the cyanobacteria in the Fe2+-rich reactors performed anoxygenic photosynthesis. This hypothesis was rejected by our in-situ microsensor measurements, which clearly showed that they performed oxygenic photosynthesis. This was further supported by our failed attempts to grow the cultured cyanobacteria in the presence of DCMU (3-(3,4-dichlorophenyl)-1,1-dimethylurea), an inhibitor of oxygenic photosynthesis, using either sulfide or iron as the electron donor, questioning the ability of these cyanobacteria to perform anoxygenic photosynthesis.

Recently it was shown that some filamentous cyanobacteria from iron-rich environments accumulate iron-oxides internally (Brown et al., 2010). These cyanobacteria are not full with iron particles as one would expect from an organism that is continuously exposed to high Fe2+ concentrations. Therefore, it may be that the creation of iron inclusions is an auxiliary mechanism only. Our NanoSIMS measurements did not detect any accumulation of iron oxides inside the cyanobacteria cells from the Äspö HRL (Figure S6). Such an accumulation would have accounted for the lack of external iron precipitates and may have provided a detoxification mechanism.

The above results call for a different mechanism to prevent encrustation in iron while actively producing O2. We suggest that, counter-intuitively, it is the photosynthetic activity itself, in combination with mass transfer limitation, that protects cyanobacteria against iron encrustation.

Our data show that each of the three cyanobacterial communities sampled is adapted to the iron concentrations it lives in. Oxygen production by the cyanobacteria enriched from the Fe2+-poor reactor is inhibited by more than 1 μM Fe2+, yet they never encounter higher concentrations in their natural habitat. To confirm that this is true also for the original biofilm community from the Fe2+-poor reactor and not only a trait of the enriched cyanobacteria, we exposed freshly collected biofilms to iron concentrations present in the Fe2+-rich reactors. As expected, photosynthesis was inhibited within minutes of the exposure. Intriguingly, the observed decline in oxygen production was coupled with a transient increase in pH at the biofilm surface (Figure S5) for which we presently do not have an explanation.

The cyanobacteria from the aerated Fe2+-rich reactor exhibit as well a reduced O2 production when exposed to more than 1 μM Fe2+ (at pH 7.1). Though they grow in a reactor connected to an aquifer with high ferrous iron concentration, the cyanobacterial biofilms from the aerated Fe2+-rich reactors are found only floating at the reactor water surface atop mats of Fe2+ oxidizers, where they are not in direct contact with the aquifer water and therefore also with high Fe2+ concentrations.

Notably, the inhibitory effects of iron observed in cultures from the aerated Fe2+-rich and Fe2+-poor reactors at pH 7.1 were not present when the experiment was conducted at pH 8. At this pH Fe is expected to precipitate faster and thus the cells are not exposed to high concentrations at any time. Nevertheless, the cyanobacteria from the Fe2+-poor reactor still get encrusted in iron at a pH of 7.9. This phenomenon is explained by the results of our model as discussed later on.

In contrast to the biofilms from the aerated Fe2+-rich and Fe2+-poor reactors, the submerged cyanobacterial biofilms from the non-aerated Fe2+-rich reactor increase their O2 production in response to increasing iron concentration. Nevertheless, despite their tolerance to elevated Fe2+ concentrations, these are not required for growth in culture as also confirmed by their continuous activity at all tested Fe2+ concentrations.

Modeling of Fe2+ concentrations in the non-aerated Fe2+-rich reactor suggests that all Fe2+ is precipitated at a distance of at least 400 μm from the biofilm surface. Thus, at steady state the cyanobacteria forming the biofilm are not exposed to high Fe2+ in their microenvironment. The precipitated Fe(oxy)hydroxides are probably dispersed away by the water movement. Although true steady state conditions would be reached rather slowly (in ~10 min), our simulation suggests that already after about 20 s the biofilm is exposed to little or no Fe2+ at all. This suggests the necessity for these cyanobacteria to be able to tolerate high Fe2+ concentrations for at least a short period of time (seconds to minutes).

The cyanobacteria in the aerated Fe2+-poor reactor are not able to precipitate the Fe2+ away from their surface. Even if a theoretical steady-state were reached, which would take about 2 h, Fe2+ concentrations inside the biofilm would still be about 0.3 μM. Given the low biomass and the continuous movement of the biofilm, such a steady-state condition can, however, never be reached. Thus, given the already high pH in the water column of this reactor, whatever O2 these cyanobacteria produce reacts immediately with the available Fe2+ and precipitates on the filaments themselves. Furthermore, Fe2+ is known to bind to charged moieties of extracellular polymeric substances (Fortin and Langley, 2005). Therefore, the continuous movement of the biofilms coupled with the low O2 production will additionally lead to the adherence of Fe to the filaments. Though these cyanobacteria are able to achieve high biomass in Fe2+-poor culture media, an increase in Fe2+ above 1 μM inhibits their growth. Therefore these organisms are confined to environments with low Fe2+.

High photosynthesis rates appear to be a common trait of benthic cyanobacterial communities described from environments with high Fe2+ concentrations. Descriptions that include O2 and pH data measured in such systems are, however, rare (Pierson et al., 1999; Wieland et al., 2005). We applied our model on data available for cyanobacterial mats from Chocolate Pots (Yellowstone National Park, US) (Pierson et al., 1999) and a saline lake from Camargue, France (Wieland et al., 2005) using the reported pH, O2 and Fe2+ concentrations. The calculated half-life of Fe+2 at the surface of the mats described by Pierson et al. (1999) ranges between 19 and 35 ms. Since the data provided by these authors do not include pH and O2 profiles in the water column above the mats, full iron profiles could not be reconstructed. Interestingly, the same study reported stimulation of O2 production by an increasing concentration of Fe2+, similar to what we have found for the cyanobacteria from our non-aerated Fe2+-rich reactor. With respect to the Camargue saline lake, Fe2+ diffuses toward the cyanobacterial populations at the surface of the mats from deeper sediment layers (Wieland et al., 2005). The lake water is oxic and has a pH >8.9, thus Fe2+ would not be stable under these conditions (Morgan and Lahav, 2007). Nevertheless, calculated half-life of Fe2+ in these mats ranges between 2 and 8 ms. In both cases the short (calculated) half-life of Fe2+ in the microenvironment of the cyanobacteria suggests that they are not exposed to high concentration of Fe2+.

We propose that cyanobacteria living in benthic communities in Fe2+-rich environments require high photosynthesis rates to avoid self-encrustation in iron precipitates. This attribute combined with mass transfer resistance will lead to elevated pH and O2 concentrations, which will form a barrier that prevents Fe from precipitating directly on the cells. Coupled with the flow conditions of natural water bodies the majority of the abiotically precipitated iron will be dispersed by the water. The high rate of photosynthesis will ensure that the barrier will be established within seconds to minutes in case flow conditions or iron concentrations in the ambient water are fluctuating.

Under the experimental conditions in the Äspö HRL, the barrier is present continuously because of the uninterrupted exposure to light, which would not be the case under natural conditions due to diurnal light fluctuations. Nevertheless, such light fluctuations should not have a significant effect on the ability of cyanobacteria to prevent self-encrustation in iron. Fe2+-rich environments, such as the one in the Äspö HRL, typically have very low O2 concentrations (Pierson et al., 1999; Ionescu et al., 2014a). Thus, in the dark, when there is no photosynthetic activity, the microenvironment in the cyanobacterial biofilms will rapidly turn anoxic due to the combined effects of respiration and mass transfer resistance, and the cells will not face an encrustation problem. The need for a protection mechanism against iron encrustation returns as soon as the photosynthetic activity resumes upon onset of illumination. Here, a high rate of photosynthesis to minimize the exposure time to high Fe2+ while producing O2 will be essential.

In addition to iron self-encrustation, cyanobacteria from Fe2+-rich environments need to deal also with Fe2+ toxicity (Brown et al., 2005; Shcolnick and Keren, 2006). While the iron-barrier provides a protection against iron toxicity during day time, it will have no effect in the dark. Therefore, we suggest that these cyanobacteria require a second mechanism to deal with the high Fe2+ concentrations at night, such as elaborate metal export systems (Shcolnick et al., 2009).

Single cells or biofilms below a critical biomass appear to get encrusted in iron (Pierson et al., 1999). The amount of biomass necessary to create the suggested “iron barrier” probably cannot be reached under the conditions in which the cells would need such a barrier. Hence, we suggest that new biofilms of the required critical biomass are formed in a “Fe2+ neutral” environment (e.g., floating on the surface or on the shores of a water body). When such biofilms become permanently exposed to high Fe2+, their survival is determined by the rapid achievement of a steady state in the distribution of Fe2+ in the microenvironment around the biofilms. This in turn depends on biomass, the overall photosynthesis rate of the biofilms and the ability of the biofilms to respond to the change in Fe2+ concentrations. This also suggests that a biofilm that contains a critical biomass of “iron tolerant cyanobacteria” may shelter less tolerant species, which could explain the observed partial overlap between the cyanobacterial communities from the aerated and non-aerated Fe2+-rich reactors.

The ability of cyanobacteria to survive in Fe2+-rich environments without getting encrusted while at the same time facilitating precipitation of iron oxides through their O2 producing photosynthetic activity may have implications for our understanding of early Earth geology. Cyanobacteria have been often suggested to be involved in the creation of the banded iron formations (BIF), the largest Fe depositions on Earth. Whether their impact was directly in the water body (Cloud, 1965, 1973) or indirectly by oxygenation of the atmosphere remains controversial (Cloud, 1968). However, despite cyanobacterial microfossils being found in BIFs (Cloud, 1965), the overall abundance of organic matter is scarce (Bontognali et al., 2013). If cyanobacteria were directly involved in the formation of BIFs, the existence of a cyanobacterial protective “iron barrier” may explain the lack of biomass in the Fe precipitates. Such a barrier mechanism would prevent the cyanobacteria from becoming entrapped in the precipitated iron. The Fe2+ supplied from the deep primordial ocean (Wang et al., 2009) would have been oxidized in the water column below the chlorophyll maximum and sink down as particulate Fe(III) without the carryover of biomass. Intuitively, marine cyanobacteria appear to be suitable model organisms to study the existence of such a mechanism. Nevertheless, modern oceans have been poor in iron for about 2 Ga, a substantial period for evolutionary adaptation, which makes it unlikely for marine cyanobacteria today to be adapted to such elevated Fe2+ concentrations. Hence, in this case, cyanobacteria from brackish-saline, iron-rich environments such as the Äspö HRL still provide the best model organisms for studying ancient Earth marine analogs.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the SKB staff for technical, logistical, and analytical support at the Äspö HRL. Joachim Reitner is acknowledged for the initiation of the project “Biomineralisation, Biogeochemistry and Biodiversity of chemolithotrophic Microorganisms in the Tunnel of Äspö (Sweden),” which provided funding for this study through the DFG (German Research Foundation) research unit FOR 571. We thank the reviewers for valuable comments that helped improve the manuscript.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: http://www.frontiersin.org/journal/10.3389/fmicb.2014.00459/abstract

Pictures of an aerated (A) and a non-aerated (B) reactor set up in the ÄSPÖ Hard Rock Laboratory. The draining tube of the non-aerated reactor was bended such that flow-through was obtained only when the reactor was full to the top.

(A) Experimental setup for laboratory microsensor measurements. N2-purged medium was run through a small flow chamber (V~5 ml) (B) in which filters overgrown with cyanobacterial biofilms were placed and measured using microsensors (C).

Maximum Likelihood tree of cyanobacterial sequences from the different reactors together with reference sequences. The sequences are labeled according to their origin: 1327 R1 and R2 for the Fe2+-rich aerated and non-aerated reactors, respectively; TASF R1 for the Fe2+-poor aerated reactor. Bold labels were used in the case of larger clusters of sequences of measured cultures.

O2 microprofiles measured in the cyanobacterial biofilms in the aerated and non-aerated Fe2+-rich reactors in the dark (filled symbols) and at incident irradiance of 60 μmol photons m−2 s−1 (open symbols). The bars represent gross photosynthesis rates (in μM O2 s−1) as measured by the light-dark-shift method in 100 μm steps in the biofilm. All measurements were done in-situ.

In-situ O2 and pH microprofiles measured in the cyanobacterial biofilm from the aerated Fe2+-poor reactor before and after the addition of 25 μM of Fe2+ at time points indicated in the legend. All profiles were measured using similar light intensity as used in the reactors. The measurements were conducted outside of the reactor using the natural water. N2 gas was bubbled continuously to maintain anoxic conditions.

Nanoscale Secondary Ion Mass Spectrometry (nanoSIMS) analysis of a cyanobacterial enrichment culture and an iron oxidizing mat obtained from the non-aerated Fe2+-rich reactor and incubated with 57Fe2+. The Secondary electron panels (A,C) show the surface topography with color bar representing signal intensity. No enrichment with 57Fe2+ can be seen near or on the cyanobacterial filaments (B), while an overall high concentration of 57Fe2+ was detected in the iron oxidizing mat including a highly enriched single filament (D).

References

- Arunasri K., Sasikala C., Ramana C. V., Süling J., Imhoff J. F. (2005). Marichromatium indicum sp. nov., a novel purple sulfur gammaproteobacterium from mangrove soil of Goa, India. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 55, 673–679 10.1099/ijs.0.02892-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atkins P. W. (1978). Physical Chemistry, 1st Edn. Oxford: Oxford University Press [Google Scholar]

- de Beer D., Stambler N. (2000). A microsensor study of light enhanced Ca2+ uptake and photosynthesis in the reef-building hermatypic coral Favia sp. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 194, 75–85 10.3354/meps194075 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bontognali T. R. R., Fischer W. W., Föllmi K. B. (2013). Siliciclastic associated banded iron formation from the 3.2Ga Moodies Group, Barberton Greenstone Belt, South Africa. Precambrian Res. 226, 116–124 10.1016/j.precamres.2012.12.003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brown I. I., Bryant D. A., Casamatta D., Thomas-Keprta K. L., Sarkisova S. A., Shen G., et al. (2010). Polyphasic characterization of a thermotolerant siderophilic filamentous cyanobacterium that produces intracellular iron deposits. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 76, 6664–6672 10.1128/AEM.00662-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown I. I., Mummey D., Cooksey K. E. (2005). A novel cyanobacterium exhibiting an elevated tolerance for iron. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 52, 307–314 10.1016/j.femsec.2004.11.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan C. S., Fakra S. C., Edwards D. C., Emerson D., Banfield J. F. (2009). Iron oxyhydroxide mineralization on microbial extracellular polysaccharides. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 73, 3807–3818 10.1016/j.gca.2009.02.036 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cloud P. (1973). Paleoecological significance of the banded iron formation. Econ. Geol. 68, 1135–1143 10.2113/gsecongeo.68.7.1135 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cloud P. E. (1965). Significance of the gunflint (Precambrian) microflora: photosynthetic oxygen may have had important local effects before becoming a major atmospheric gas. Science 148, 27–35 10.1126/science.148.3666.27 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cloud P. E. (1968). Atmospheric and hydrospheric evolution on the primitive earth: both secular accretion and biological and geochemical processes have affected earth's volatile envelope. Science 160, 729–736 10.1126/science.160.3829.729 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen Y., Jørgensen B. B., Revsbech N. P., Poplawski R. (1986). Adaptation to hydrogen sulfide of oxygenic and anoxygenic photosynthesis among Cyanobacteria. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 51, 398–407 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies C. W. (1962). Ion Association. Washington, DC: Butterworth [Google Scholar]

- Fortin D., Langley S. (2005). Formation and occurrence of biogenic iron-rich minerals. Earth-Sci. Rev. 72, 1–19 10.1016/j.earscirev.2005.03.00218380875 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fu L., Niu B., Zhu Z., Wu S., Li W. (2012). CD-HIT: accelerated for clustering the next-generation sequencing data. Bioinformatics 28, 3150–3152 10.1093/bioinformatics/bts565 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hegler F., Schmidt C., Schwarz H., Kappler A. (2010). Does a low-pH microenvironment around phototrophic Fe(II)-oxidizing bacteria prevent cell encrustation by Fe(III) minerals? FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 74, 592–600 10.1111/j.1574-6941.2010.00975.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Y., Niu B., Gao Y., Fu L., Li W. (2010). CD-HIT suite: a web server for clustering and comparing biological sequences. Bioinformatics 26, 680–682 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ionescu D., Heim C., Polerecky L., Ramette A., Häusler S., Bizic-Ionescu M., et al. (2014a). Diversity of iron oxidizing and reducing bacteria in flow reactors in the Äspö Hard Rock Laboratory. Geomicrobiol. J. (in press). [Google Scholar]

- Ionescu D., Heim C., Polerecky L., Thiel V., de Beer D. (2014b). Biotic and abiotic oxidation and reduction of iron at circumneutral pH are inseparable processes under natural conditions. Geomicrobiol. J. (in press). [Google Scholar]

- Ionescu D., Siebert C., Polerecky L., Munwes Y. Y., Lott C., Häusler S., et al. (2012). Microbial and chemical characterization of underwater fresh water springs in the Dead Sea. PLoS ONE 7:e38319 10.1371/journal.pone.0038319 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khalil M., Teunissen C., Langkammer C. (2011). Iron and neurodegeneration in multiple sclerosis. Mult. Scler. Int. 2011:606807 10.1155/2011/606807 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laaksoharju M., Tullborg E., Wikberg P., Wallin B., Smellie J. (1999). Hydrogeochemical conditions and evolution at the Äspö HRL, Sweden. Appl. Geochemistry 14, 835–859 10.1016/S0883-2927(99)00023-2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lane D. (1991). 16S/23S rRNA sequencing, in Nucleic Acid Techniques in Bacterial Systematics, eds Stackebrandt E., Goodfellow M. (New York; Chichester: John Wiley and Sons; ), 115–175 [Google Scholar]

- Lewy Z. (2012). Banded iron formations (BIFs) and associated sedediments do not reflect the physical and chemical properties of early precambrian seas. Int. J. Geosci. 03, 226–236 10.4236/ijg.2012.31026 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan B., Lahav O. (2007). The effect of pH on the kinetics of spontaneous Fe(II) oxidation by O2in aqueous solution–basic principles and a simple heuristic description. Chemosphere 68, 2080–2084 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2007.02.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olson J. M. (2006). Photosynthesis in the Archean era. Photosynth. Res. 88, 109–117 10.1007/s11120-006-9040-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oren A., Ionescu D., Lipski A., Altendorf K. (2005). Fatty acid analysis of a layered community of cyanobacteria developing in a hypersaline gypsum crust. Arch. Hydrobiol. Suppl. Algol. Stud. 117, 339–347 10.1127/1864-1318/2005/0117-0339 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Parenteau M. N., Cady S. L. (2010). Microbial piosignatures in iron-mineralized phototrophic mats at Chocolate Pots hot springs, Yellowstone National Park, United States. Palaios 25, 97–111 10.2110/palo.2008.p08-133r [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pierson B. K., Parenteau M. N. (2000). Phototrophs in high iron microbial mats: microstructure of mats in iron-depositing hot springs. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 32, 181–196 10.1111/j.1574-6941.2000.tb00711.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pierson B. K., Parenteau M. N., Griffin B. M. (1999). Phototrophs in high-iron-concentration microbial mats?: physiological ecology of phototrophs in an iron-depositing hot spring. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 65, 5474–5483 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polerecky L., Adam B., Milucka J., Musat N., Vagner T., Kuypers M. M. M. (2012). Look@NanoSIMS–a tool for the analysis of nanoSIMS data in environmental microbiology. Environ. Microbiol. 14, 1009–1023 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2011.02681.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quast C., Pruesse E., Yilmaz P., Gerken J., Schweer T., Yarza P., et al. (2012). The SILVA ribosomal RNA gene database project: improved data processing and web-based tools. Nucleic Acids Res. 41, 1–7 10.1093/nar/gks1219 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Revsbech N., Jorgensen B. B. (1981). Primary production of microalgae in sediments measured by oxygen microprofile, H14CO3 2 fixation and oxygen exchange methods. Limnol. Oceangr. 26, 717–730 10.4319/lo.1981.26.4.0717 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Revsbech N. P. (1989). An oxygen microsensor with a guard cathode. Limnol. Oceanogr. 34, 474–478 10.4319/lo.1989.34.2.0474 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Riemer J., Hoepken H. H., Czerwinska H., Robinson S. R., Dringen R. (2004). Colorimetric ferrozine-based assay for the quantitation of iron in cultured cells. Anal. Biochem. 331, 370–375 10.1016/j.ab.2004.03.049 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rippka R., Deruelles J., Waterbury J. B., Herdman M., Stanier R. Y. (1979). Generic assignments, strain histories and properties of pure cultures of cyanobacteria. J. Gen. Microbiol. 111, 1–61 10.1099/00221287-111-1-1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Saini G., Chan C. S. (2013). Near-neutral surface charge and hydrophilicity prevent mineral encrustation of Fe-oxidizing micro-organisms. Geobiology 11, 191–200 10.1111/gbi.12021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shcolnick S., Keren N. (2006). Metal homeostasis in cyanobacteria and chloroplasts. Balancing benefits and risks to the photosynthetic apparatus. Plant Physiol. 141, 805–810 10.1104/pp.106.079251 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shcolnick S., Summerfield T. C., Reytman L., Sherman L. A., Keren N. (2009). The mechanism of iron homeostasis in the unicellular cyanobacterium synechocystis sp. PCC 6803 and its relationship to oxidative stress. Plant Physiol. 150, 2045–56 10.1104/pp.109.141853 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki T., Hashimoto H., Matsumoto N., Furutani M., Kunoh H., Takada J. (2011). Nanometer-scale visualization and structural analysis of the inorganic/organic hybrid structure of Gallionella ferruginea twisted stalks. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 77, 2877–2881 10.1128/AEM.02867-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Veen W. L., Mulder E. G., Deinema M. H. (1978). The Sphaerotilus-Leptothrix group of bacteria. Microbiol. Rev. 42, 329–356 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ventura S., Viti C., Pastorelli R., Giovannetti L. (2000). Revision of species delineation in the genus Ectothiorhodospira. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 50, 583–591 10.1099/00207713-50-2-583 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y., Xu H., Merino E., Konishi H. (2009). Generation of banded iron formations by internal dynamics and leaching of oceanic crust. Nat. Geosci. 2, 781–784 10.1038/ngeo652 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wieland A., Zopfi J., Benthien M., Kühl M. (2005). Biogeochemistry of an iron-rich hypersaline microbial mat (Camargue, France). Microb. Ecol. 49, 34–49 10.1007/s00248-003-2033-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan-Hui L., Gregory S. (1974). Diffusion of ions in sea water and in deep-sea sediments. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 38, 703–714 10.1016/0016-7037(74)90145-8 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Pictures of an aerated (A) and a non-aerated (B) reactor set up in the ÄSPÖ Hard Rock Laboratory. The draining tube of the non-aerated reactor was bended such that flow-through was obtained only when the reactor was full to the top.

(A) Experimental setup for laboratory microsensor measurements. N2-purged medium was run through a small flow chamber (V~5 ml) (B) in which filters overgrown with cyanobacterial biofilms were placed and measured using microsensors (C).

Maximum Likelihood tree of cyanobacterial sequences from the different reactors together with reference sequences. The sequences are labeled according to their origin: 1327 R1 and R2 for the Fe2+-rich aerated and non-aerated reactors, respectively; TASF R1 for the Fe2+-poor aerated reactor. Bold labels were used in the case of larger clusters of sequences of measured cultures.

O2 microprofiles measured in the cyanobacterial biofilms in the aerated and non-aerated Fe2+-rich reactors in the dark (filled symbols) and at incident irradiance of 60 μmol photons m−2 s−1 (open symbols). The bars represent gross photosynthesis rates (in μM O2 s−1) as measured by the light-dark-shift method in 100 μm steps in the biofilm. All measurements were done in-situ.

In-situ O2 and pH microprofiles measured in the cyanobacterial biofilm from the aerated Fe2+-poor reactor before and after the addition of 25 μM of Fe2+ at time points indicated in the legend. All profiles were measured using similar light intensity as used in the reactors. The measurements were conducted outside of the reactor using the natural water. N2 gas was bubbled continuously to maintain anoxic conditions.

Nanoscale Secondary Ion Mass Spectrometry (nanoSIMS) analysis of a cyanobacterial enrichment culture and an iron oxidizing mat obtained from the non-aerated Fe2+-rich reactor and incubated with 57Fe2+. The Secondary electron panels (A,C) show the surface topography with color bar representing signal intensity. No enrichment with 57Fe2+ can be seen near or on the cyanobacterial filaments (B), while an overall high concentration of 57Fe2+ was detected in the iron oxidizing mat including a highly enriched single filament (D).