Abstract

A prominent risk factor of primary open-angle glaucoma is ocular hypertension, a pathologic state caused by impaired outflow of aqueous humor through the trabecular meshwork within the iridocorneal angle. The juxtacanalicular region of the trabecular meshwork and the inner wall of Schlemm canal have been identified as the main contributors to aqueous outflow resistance, and both extracellular matrix within the trabecular meshwork and trabecular meshwork cell shape have been shown to affect outflow. Overexpression of multiple ECM proteins in perfused cadaveric human eyes has led to increased outflow resistance and elevated IOP. Pharmacologic agents targeting trabecular meshwork cytoskeletal arrangements have been developed after multiple studies demonstrated the importance of cell shape on outflow. Several groups have shown that aqueous outflow occurs only at certain segments of the trabecular meshwork circumferentially, a concept known as segmental flow. This is based on the theory that aqueous outflow is dependent on the presence of discrete pores within the Schlemm canal. Segmental flow has been described in the eyes of multiple species, including primate, bovine, mouse, and human samples. While the trabecular meshwork appears to be the major source of resistance, trabecular meshwork bypass procedures have been unable to achieve the degree of IOP reduction observed with trabeculectomy, reflecting the potential impact of distal flow, or flow through Schlemm canal and collector channels, on outflow. Multiple studies have demonstrated that outflow occurs preferentially near collector channels, suggesting that these distal structures may be more important to aqueous outflow than previously believed.

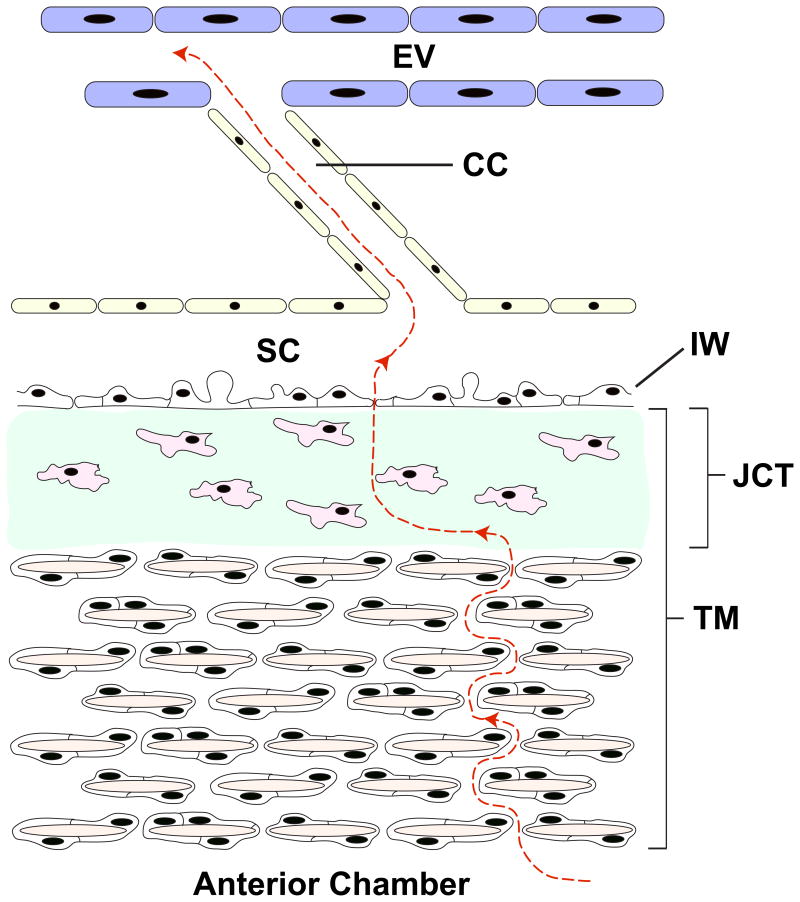

Primary open-angle glaucoma (POAG) is a disease characterized by painless vision loss due to retinal ganglion cell death, affecting more than 70 million individuals worldwide1, 2. Elevated intraocular pressure (IOP) is the only modifiable risk factor.1, 3 The flow of aqueous humor occurs through 2 routes, known as the conventional and uveoscleral pathways. The conventional pathway, which regulates approximately 85% of aqueous outflow, refers to the flow of aqueous humor through the trabecular meshwork (TM), Schlemm canal, collector channels, and episcleral veins (Figure 1).4 Within this pathway, the juxtacanalicular connective tissue region of trabecular meshwork has been shown to be the key source of outflow resistance.5,6

Figure 1.

Schematic illustrating the major components of the conventional outflow pathway. Aqueous humor (red dashed line) flows through the initial portion of the trabecular meshwork (TM), juxtacanalicular connective tissue region, inner wall of Schlemm canal (IW), Schlemm canal (SC), collector channel (CC), and finally reaches the episcleral vein (EV). Multiple TM cells encase the trabecular beams (tan) within the TM. The juxtacanalicular connective tissue is composed of sparse cells (pink) and substantial ECM (green).

Given the role of the trabecular meshwork in outflow resistance, many surgical devices have recently been engineered to bypass the trabecular meshwork. These devices include ab interno trabeculectomy (Trabectome, Neomedix Inc.) and the iStent (Glaukos Corp.), Express (Optonol Ltd.), and Hydrus (Ivantis Inc.) shunts. However, to date, none of these procedures has been shown to reduce IOP to the degree achieved by trabeculectomy, the gold standard glaucoma procedure. For example, multiple studies have demonstrated an approximately 61% decrease in IOP with trabeculectomy compared with a 43% IOP decrease with Trabectome after 2 years.7,8 Use of the iStent decreased IOP by only 16% in one study.9 Trabecular meshwork bypass procedures appear to be unable to achieve the IOP decrease observed with trabeculectomy. Patients who receive trabecular meshwork bypass procedures often remain on medications after the procedure, in contrast to patients who receive trabeculectomy.

The failure of trabecular meshwork bypass surgeries to reduce IOP further has shed new light on the possible importance of distal flow, which refers to the flow of aqueous humor subsequent to the trabecular meshwork and Schlemm canal (ie, within the collector channels and episcleral veins). In this review, aqueous humor outflow within the trabecular meshwork and distal segments of the outflow pathway will be discussed.

Role of Extracellular Matrix and Cell Morphology within the Trabecular Meshwork

Both extracellular matrix and cell morphology have been shown to affect outflow through the trabecular meshwork. With an increase in actin stiffness and the development of crosslinked actin networks, cells assume a rigid shape and outflow has been shown to decrease in bovine eyes and human trabecular meshwork cells in vitro.10–12 Multiple pharmacologic compounds have been shown to decrease the formation of these actin stress fibers, thereby increasing outflow through the trabecular meshwork in primate eyes and human tissue in vitro. These compounds include ethacrynic acid, latrunculins, and Rho-kinase inhibitors, and induce changes in cell shape, increasing outflow around cells and decreasing IOP (Figure 2).13–18 Many of these compounds are currently in clinical trials.

Figure 2.

Impact of ROCK inhibitor on trabecular meshwork cell morphology and shape (cells stained with phalloidin). Actin is prominent in (A) normal cells, but is significantly decreased in (B) cells treated with the ROCK inhibitor Y-27632. (Inoue T, Tanihara H. Rho-associated kinase inhibitors: a novel glaucoma therapy. Prog Retin Eye Res 2013; 37:1–12, reprinted with permission from Elsevier.)

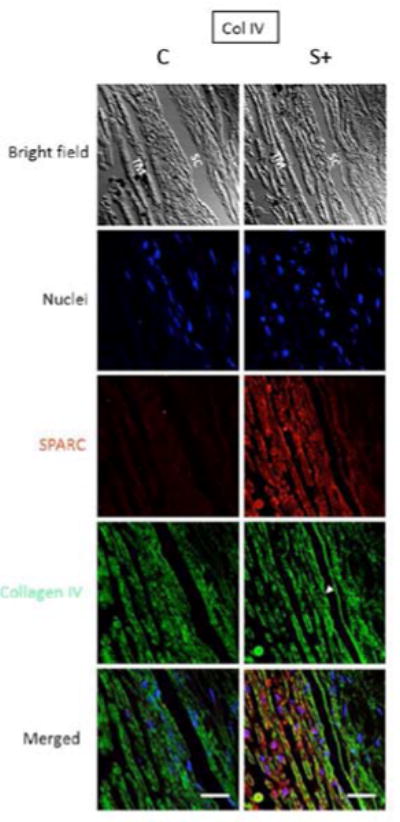

Extracellular matrix (ECM) has been shown to strongly influence aqueous outflow and IOP. Overexpression of a variety of proteins, including myocilin, cochlin, secreted frizzled-related protein, gremlin, and secreted protein acidic and rich in cysteine (SPARC), in human cadaveric eyes has reduced outflow or increased IOP.19–23 Overexpression of these proteins has been shown to increase IOP by upregulating ECM proteins such as fibronectin, collagens, and plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 (Figure 3). In addition, inhibition of ECM degradation has been shown to increase outflow resistance in perfused human eyes by approximately 40%, reflecting the importance of ECM turnover.23,24

Figure 3.

The effect of SPARC overexpression on collagen IV expression within the trabecular meshwork in perfused human cadaveric eyes. The SPARC overexpression is confirmed (red), and the concentration of collagen IV is significantly increased with SPARC overexpression (green) (bar = 30μm).23

Multiple studies have demonstrated that transforming growth factor-β2 (TGFβ2) is increased in the aqueous humor of glaucomatous eyes.25–33 Overexpression of TGFβ2 has been shown to reduce aqueous outflow and increase IOP in both mice and rats by upregulation of certain ECM proteins.34–36 In mice lacking SPARC, overexpression of TGFβ2 is unable to induce a significant increase in IOP, reflecting the importance of SPARC in regulating ECM, and thus outflow and IOP (unpublished data). Aside from elevation of TGFβ2 in glaucomatous eyes, sheath-derived plaques have been found to accumulate within the trabecular meshwork, which are thought to impair outflow. The increase in sheath-derived plaques strongly correlates with optic nerve head damage, further substantiating their role in glaucoma.37,38

Synergistic effects of trabecular meshwork cellular morphology and ECM may also contribute to determining outflow within the trabecular meshwork. One study has shown that trabecular meshwork contractility is dependent on specific integrin complexes39; other groups have demonstrated the importance of a protein called integrin-linked kinase in modulating intracellular architecture as well as extracellular matrix deposition.40 Ultimately, both trabecular meshwork cytoskeletal properties as well as the surrounding extracellular matrix contribute to the degree of outflow through the trabecular meshwork, and hence IOP.

Juxtacanalicular Connective Tissue and Inner Wall of Schlemm Canal: Key Source of Outflow Resistance

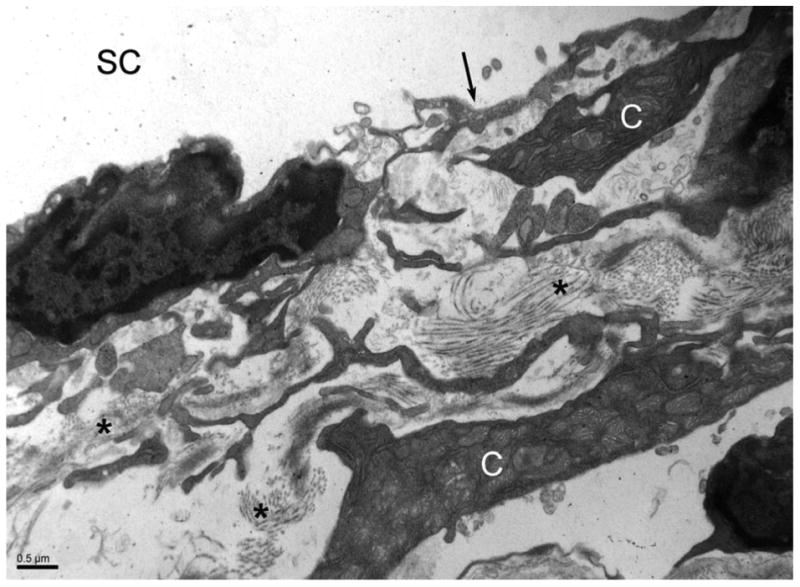

The juxtacanalicular connective tissue is the final portion of the trabecular meshwork. It is amorphous and composed mostly of ECM with occasional cells (Figure 4). The juxtacanalicular connective tissue has been identified as a key contributor to outflow resistance. Studies conducted in the late 1980s demonstrated that in monkeys, a significant portion of pressure reduction occurs slightly upstream of Schlemm canal, seemingly pointing to the juxtacanalicular connective tissue region.6,41 Additional studies comparing normal and glaucomatous human eyes found the greatest difference between the 2 groups in juxtacanalicular connective tissue morphology; glaucomatous eyes had a significantly thicker juxtacanalicular connective tissue region than the control eyes.42 A specific methodology used to evaluate ECM ultrastructure showed that the juxtacanalicular connective tissue contains an intricate mixture of ECM with large open spaces lacking ECM.43 Substances such as proteoglycans and glycosaminoglycans are thought to account for some of the resistance within the juxtacanalicular connective tissue, but this cannot be appreciated using current methodology. To further demonstrate the importance of the juxtacanalicular connective tissue, sheath-derived plaques have been shown to accumulate in this region.38,44

Figure 4.

Electron microscopy of the juxtacanalicular connective tissue. This portion of the trabecular meshwork is composed of sparse cells (C) with abundant, amorphous extracellular matrix (*). The inner wall of Schlemm canal (arrow) and Schlemm canal (SC) are labeled.

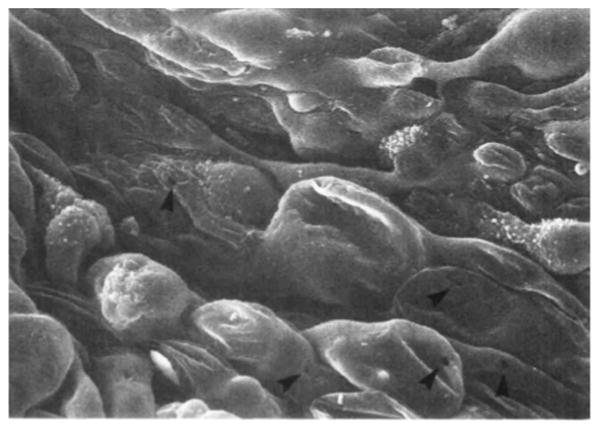

The inner wall of Schlemm canal is also thought to contribute to outflow resistance. Aqueous humor is thought to traverse through the inner wall via micron-sized pores (Figure 5). Although the concentration of these pores has been debated in the literature, 1 important study demonstrated that the pore density is decreased in glaucomatous eyes.45 This is still a highly debated topic, but it is possible that a decrease in the number of pores would limit aqueous outflow, leading to elevated IOP.

Figure 5.

Electron microscopy demonstrating pores (arrows) within the inner wall endothelium of Schlemm canal. (Reprinted with permission. Allingham RR, de Kater AW, Ethier CR, Anderson PJ, Hertzmark E, Epstein DL. The relationship between pore density and outflow facility in human eyes. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 1992; 33:1661– 1669. Available at: http://www.iovs.org/content/33/5/1661.full.pdf. Accessed June 16, 2014

Another concept that has been studied in various animal models is washout, which describes a significant decrease in outflow resistance and IOP after a certain period of anterior segment perfusion. This phenomenon, first described in the 1950s,46 has been reported in multiple species including cow, monkey, and pig eyes47–49 but not in human and mouse eyes.50,51 In monkey and bovine eyes, the juxtacanalicular connective tissue region becomes distended and exhibits greater separation from the Schlemm canal inner wall when washout is observed (ie, when outflow resistance is notably decreased).52–54 This once again demonstrates the importance of the juxtacanalicular connective tissue– Schlemm canal interface in outflow resistance. The reason washout is not observed in the human or murine eye is unclear and is currently an important topic of investigation within the glaucoma community.

Funneling Theory and Segmental Flow

The physical association of the Schlemm canal inner wall and the juxtacanalicular connective tissue region is thought to synergistically provide the most resistance within the aqueous outflow pathway, given the limiting nature of the inner wall pores as described above. A more rigorous biophysical analysis of the tissue established the theory that aqueous humor probably funnels through the juxtacanalicular connective tissue as it approaches the pores within the inner wall (Figure 6). 55 This would mean that only certain sections of the trabecular meshwork corresponding to the presence of Schlemm canal pores are used for outflow. This would subsequently result in a much greater resistance (approximately a 15- to 30-fold increase) attributable to the juxtacanalicular connective tissue–inner wall section of the outflow pathway.55

Figure 6.

Schematic of funneling theory, whereby outflow through the trabecular meshwork occurs specifically in areas in which pores in the inner wall of Schlemm canal are present. Reprinted with permission from Investigative Ophthalmology and Visual Sciences.53

Experiments that break this so-called tethering between the Schlemm canal inner wall and juxtacanalicular connective tissue using the chemical ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid demonstrated an 85% decrease in outflow resistance.56 A more recent study demonstrated that when colloidal gold was injected into perfused monkey eyes, only 10% to 20% of the total length of trabecular meshwork was labeled, reflecting the explicit location of outflow around major pores. However, when H-7, a serine-threonine kinase inhibitor that alters cell shape and weakens the cytoskeleton, was injected into live monkey eyes and followed by colloidal gold labeling, over 80% of the trabecular meshwork became uniformly labeled and electron microscopy demonstrated a dissociation of the juxtacanalicular connective tissue and Schlemm canal inner wall.57,58 Such studies appear to support the funneling theory and the importance of the juxtacanalicular connective tissue–Schlemm canal inner wall interaction.

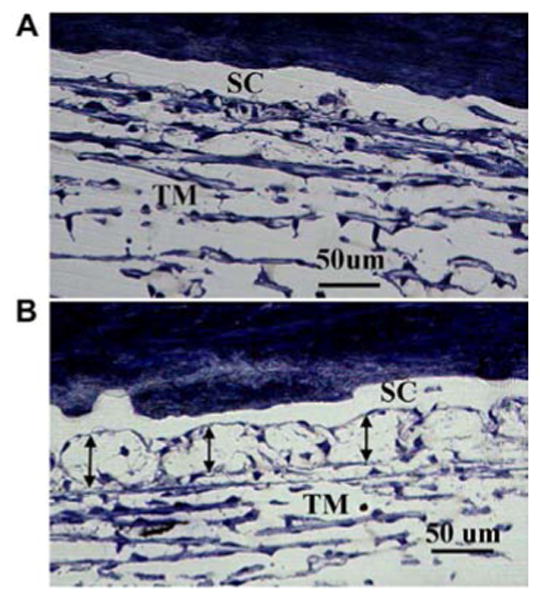

Expanding the funneling theory further, multiple studies have demonstrated that outflow is not uniform throughout the trabecular meshwork. Rather, outflow occurs in only certain regions. This concept, known as segmental flow, has been verified using a variety of methods in bovine, mouse, monkey, and human eyes (Figure 7).57,59–63 The morphology of the tissue where flow occurs is variable: One study in mice found that high-flow regions demonstrate greater separation between trabecular meshwork cells,61 whereas studies in bovine eyes found that greater flow occurred in areas with dissociation between the juxtacanalicular connective tissue and Schlemm canal inner wall.59 Treatment of monkey eyes with a Rho-kinase inhibitor led to a more uniform distribution of fluorescent tracer and an overall decrease in the connections between juxtacanalicular connective tissue cells and their ECM64 (Figure 8). Outflow resistance decreased significantly with this treatment.

Figure 7.

Illustration of segmental flow in the mouse eye using fluorescent microbeads. A: Segmental flow in the wild-type mouse eye. Microbeads are only present in certain parts of the trabecular meshwork. B: Outflow is more uniform in the SPARC knockout mouse due to the lack of this matricellular protein.61

Figure 8.

Effect of ROCK inhibitor on the association between juxtacanalicular connective tissue and inner wall of Schlemm canal of monkey eyes. A: Normal, untreated eye with Schlemm canal (SC) and trabecular meshwork (TM) labeled. It is difficult to distinguish the inner wall from the TM. B: Eye treated with a ROCK inhibitor. There is a clear separation of the inner wall, with a ballooning effect of the juxtacanalicular connective tissue region. Reprinted with permission from Experimental Eye Research.64

In human eyes perfused with fluorescent microbeads, the tracer was found to collect in large, empty spaces within the juxtacanalicular connective tissue in areas of active flow.65 Genetic analyses of areas of high-flow and low-flow have demonstrated interesting results. The presence of versican, a large chondroitin sulfate proteoglycan, was inversely correlated with flow; areas with low outflow were found to have high versican levels and vice-versa, indicating that versican could contribute to outflow patterns.66 A subsequent study by the same group attempted to identify other ECM genes that were expressed at different levels in high-flow and low-flow regions. Several genes were found, including versican and SPARC, whose expression was inversely correlated in various regions of the eye.A These findings cumulatively suggest that ECM proteins may influence segmental outflow in addition to the presence of pores in the inner wall of Schlemm canal. Clinical correlates to the principle of segmental flow include anecdotal evidence that multiple trabecular meshwork bypass devices (eg, iStent) are often required before a significant decrease in IOP is observed.

Distal Flow: An Important Contributor?

The importance of aqueous structures after Schlemm canal (ie, collector channels and episcleral veins) has also been investigated. One research group found that in bovine and monkey eyes, segmental flow was observed and areas of high flow were noted to be concentrated around collector channels (Figure 9).60,64 These data suggest that aqueous flow may be dependent on the location of distal flow structures, as collector channels could cause preferential flow by altering the pressure distribution within Schlemm canal. This is further substantiated by the fact that when IOP was artificially increased in these eyes, which is known to cause Schlemm canal collapse, the aqueous plexus (bovine variation of Schlemm canal) and juxtacanalicular connective tissue region collapsed in areas near collector channels only (Figure 10).

Figure 9.

Affinity of fluorescent microbeads for trabecular meshwork near collector channels. A: Fluorescent microbeads preferentially collect within the trabecular meshwork (TM) near collector channels (CC). B: Increase in microbead concentration in this area after treatment with a ROCK inhibitor. Reprinted with permission from Experimental Eye Research.64

Figure 10.

Light microscopy of trabecular meshwork of bovine eyes perfused at various pressures. A: At 7mm Hg, the aqueous plexus (AP) and collector channel (CC) are well organized. B, C, D: At progressively higher perfusion pressures, herniation of the trabecular meshwork into the AP and CC is observed. Reprinted with permission from Investigative Ophthalmology and Visual Sciences.60

These findings were also observed in monkey eyes that were treated with a laser to induce an IOP increase.67 Herniation of the tissue into the collector channels was observed. Previous studies modeling aqueous flow indicate that as IOP increased, herniation occurred in areas of the canal in which pressure was the lowest,68 suggesting that the concentration of collector channels could be an important factor in modulating outflow and IOP. These experimental data are corroborated by recent mathematical modeling of pressure gradients within Schlemm canal and collector channels. One study calculated that outflow would increase only13% to 26% with trabecular meshwork bypass and that the effectiveness of the bypass on IOP would be solely dependent on resistance within Schlemm canal and collector channels.69 A subsequent study by the same group calculated that trabecular meshwork bypass would reduce IOP to the mid-to-high teens only, whereas moderate Schlemm canal and collector channel dilation could decrease IOP further by 3 to 6 mm Hg.70

The importance of collector channels remains controversial. Initial studies showed that the IOP in collector channels was essentially equivalent to that of episcleral veins, indicating that collector channels did not affect outflow resistance.6,41 However, when enucleated eyes were pretreated with a trabeculotomy, at least 25% of outflow resistance remained.71–73 Data suggest that these structures do not contribute significantly to resistance specifically in glaucomatous eyes; an early study from the 1960s demonstrated that trabeculotomy completely eliminated all outflow resistance in glaucomatous eyes.74,75. However, this is in opposition to the clinical trabecular meshwork bypass data from glaucomatous eyes that was previously discussed, which demonstrated a significant decrease in IOP after the procedure but residual IOP elevation several months after the procedure.

In conclusion, the mechanics of aqueous outflow are extremely complex, influenced by myriad factors including cell shape, ECM, and tissue morphology. Multiple pharmaceutical options that are currently being developed represent unique, targeted therapy against the primary pathology in ocular hypertension and POAG. At the microscopic level, the juxtacanalicular connective tissue portion of the trabecular meshwork and the inner wall of Schlemm canal have been shown to be important determinants of outflow—in both resistance and the specific segments of the trabecular meshwork in which outflow occurs. However, distal components of the outflow pathway may also have a significant impact on outflow and IOP. As research groups and pharmaceuticals attempt to identify future devices and surgical procedures to definitively treat ocular hypertension, all the intricate components of the outflow pathway will have to be considered.

Acknowledgments

Supported by R01 EY 019654 (Dr. Rhee).

Footnotes

Financial Disclosure: Dr. Rhee is a consultant for Aerie Pharmaceuticals, Alcon Laboratories, Inc., Allegan, Inc., Aquesys, Inc., Glaukos Corp., Ivantis, Inc., Johnson & Johnson, Merck Sharp & Dohme Corp. and Santen, Inc. No other author has a financial or proprietary interest in any material or method mentioned.

References

- 1.Weinreb RN, Khaw PT. Primary open-angle glaucoma. Lancet. 2004;363:1711–1720. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16257-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Quigley HA. Number of people with glaucoma worldwide. [Accessed June 13, 2014];Br J Ophthalmol. 1996 80:389–393. doi: 10.1136/bjo.80.5.389. Available at: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC505485/pdf/brjopthal00005-0009.pdf. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rohen JW. Why is intraocular pressure elevated in chronic simple glaucoma? Anatomical considerations Ophthalmology. 1983;90:758–765. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(83)34492-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bill A, Phillips CI. Uveoscleral drainage of aqueous humour in human eyes. Exp Eye Res. 1971;12:275–281. doi: 10.1016/0014-4835(71)90149-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Overby DR, Stamer WD, Johnson M. The changing paradigm of outflow resistance generation: towards synergistic models of the JCT and inner wall endothelium. Exp Eye Res. 2009;88:656–670. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2008.11.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mäepea O, Bill A. Pressures in the juxtacanalicular tissue and Schlemm's canal in monkeys. Exp Eye Res. 1992;54:879–883. doi: 10.1016/0014-4835(92)90151-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jea SY, Francis BA, Vakili G, Filippopoulos T, Rhee DJ. Ab interno trabeculectomy versus trabeculectomy for open-angle glaucoma. Ophthalmology. 2012;119:36–42. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2011.06.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Minckler DS, Baerveldt G, Alfaro MR, Francis BA. Clinical results with the Trabectome for treatment of open-angle glaucoma. Ophthalmology. 2005;112:962–967. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2004.12.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Arriola-Villalobos P, Martínez-de-la-Casa JM, Díaz-Valle D, Fernández-Pérez C, García-Sánchez J, García-Feijoó J. Combined iStent trabecular micro-bypass stent implantation and phacoemulsification for coexistent open-angle glaucoma and cataract: a long-term study. Br J Ophthalmol. 2012;96:645–649. doi: 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2011-300218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Clark AF, Wilson K, McCartney MD, Miggans ST, Kunkle M, Howe W. Glucocorticoid-induced formation of cross-linked actin networks in cultured human trabecular meshwork cells. [Accessed June 13, 2014];Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1994 35:281–294. Available at: http://www.iovs.org/content/35/1/281.full.pdf. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Filla MS, Woods A, Kaufman PL, Peters DM. β1 and β3 integrins cooperate to induce syndecan-4-containing cross-linked actin networks in human trabecular meshwork cells. [Accessed June 13, 2014];Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2006 47:1956–1967. doi: 10.1167/iovs.05-0626. Available at: http://www.iovs.org/content/47/5/1956.full.pdf. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.O'Reilly S, Pollock N, Currie L, Paraoan L, Clark AF, Grierson I. Inducers of cross-linked actin networks in trabecular meshwork cells. [Accessed June 13, 2014];Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2011 52:7316–7324. doi: 10.1167/iovs.10-6692. Available at: http://www.iovs.org/content/52/10/7316.full.pdf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liang LL, Epstein DL, de Kater AW, Shahsafaei A, Erickson-Lamy KA. Ethacrynic acid increases facility of outflow in the human eye in vitro. Arch Ophthalmol. 1992;110:106–109. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1992.01080130108036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Epstein DL, Roberts BC, Skinner LL. Nonsulfhydryl-reactive phenoxyacetic acids increase aqueous humor outflow facility. [Accessed June 13, 2014];Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1997 38:1526–1534. Available at: http://www.iovs.org/content/38/8/1526.full.pdf. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Peterson JA, Tian B, Bershadsky AD, Volberg T, Gangnon RE, Spector I, Geiger B, Kaufman PL. Latrunculin-A increases outflow facility in the monkey. [Accessed June 13, 2014];Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1999 40:931–941. Available at: http://www.iovs.org/content/40/5/931.full.pdf. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Okka M, Tian B, Kaufman PL. Effect of low-dose latrunculin B on anterior segment physiologic features in the monkey eye. [Accessed June 13, 2014];Arch Ophthalmol. 2004 122:1482–1488. doi: 10.1001/archopht.122.10.1482. Available at: http://archopht.jamanetwork.com/data/Journals/OPHTH/9930/ELS40020.pdf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Honjo M, Inatani M, Kido N, Sawamura T, Yue BYJT, Honda Y, Tanihara H. Effects of protein kinase inhibitor, HA1077, on intraocular pressure and outflow facility in rabbit eyes. [Accessed June 13, 2014];Arch Ophthalmol. 2001 119:1171–1178. doi: 10.1001/archopht.119.8.1171. Available at: http://archopht.jamanetwork.com/data/Journals/OPHTH/6717/ELS00061.pdf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tanihara H, Inoue T, Yamamoto T, Kuwayama Y, Abe H, Araie M for the K-115 Clinical Study Group. Phase 1 Clinical trials of a selective rho kinase inhibitor, K-115. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2013;131:1288–1295. doi: 10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2013.323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Resch ZT, Fautsch MP. Glaucoma-associated myocilin: a better understanding but much more to learn. Exp Eye Res. 2009;88:704–712. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2008.08.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bhattacharya SK. Focus on molecules: cochlin. Exp Eye Res. 2006;82:355–356. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2005.09.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wordinger RJ, Fleenor DL, Hellberg PE, Pang IH, Tovar TO, Zode GS, Fuller JA, Clark AF. Effects of TGF-β2, BMP-4, and gremlin in the trabecular meshwork: implications for glaucoma. [Accessed June 13, 2014];Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2007 48:1191–1200. doi: 10.1167/iovs.06-0296. Available at: http://www.iovs.org/content/48/3/1191.full.pdf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang WH, McNatt LG, Pang IH, Millar JC, Hellberg PE, Hellberg MH, Steely HT, Rubin JS, Fingert JH, Sheffield VC, Stone EM, Clark AF. Increased expression of the WNT antagonist sFRP-1 in glaucoma elevates intraocular pressure. [Accessed June 13, 2014];J Clin Invest. 2008 118:1056–1064. doi: 10.1172/JCI33871. Available at: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2242621/pdf/JCI0833871.pdf. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Oh DJ, Kang MH, Ooi YH, Choi KR, Sage EH, Rhee DJ. Overexpression of SPARC in human trabecular meshwork increases intraocular pressure and alters extracellular matrix. [Accessed June 13, 2014];Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2013 54:3309–3319. doi: 10.1167/iovs.12-11362. Available at: http://www.iovs.org/content/54/5/3309.full.pdf. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bradley JMB, Vranka J, Colvis CM, Conger DM, Alexander JP, Fisk AS, Samples JR, Acott TS. Effect of matrix metalloproteinases activity on outflow in perfused human organ culture. [Accessed June 13, 2014];Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1998 39:2649–2658. Available at: http://www.iovs.org/content/39/13/2649.full.pdf. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tripathi RC, Li J, Chan WFA, Tripathi BJ. Aqueous humor in glaucomatous eyes contains an increased level of TGF-β2. Exp Eye Res. 1994;59:723–727. doi: 10.1006/exer.1994.1158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Inatani M, Tanihara H, Katsuta H, Honjo M, Kido N, Honda Y. Transforming growth factor-β2 levels in aqueous humor of glaucomatous eyes. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2001;239:109–113. doi: 10.1007/s004170000241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Picht G, Welge-Luessen U, Grehn F, Lütjen-Drecoll E. Transforming growth factor β2 levels in the aqueous humor in different types of glaucoma and the relation to filtering bleb development. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2001;239:199–207. doi: 10.1007/s004170000252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schlötzer-Schrehardt U, Zenkel M, Küchle M, Sakai LY, Naumann GOH. Role of transforming growth factor-β1 and its latent form binding protein in pseudoexfoliation syndrome. Exp Eye Res. 2001;73:765–780. doi: 10.1006/exer.2001.1084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Trivedi RH, Nutaitis M, Vroman D, Crosson CE. Influence of race and age on aqueous humor levels of transforming growth factor-beta 2 in glaucomatous and nonglaucomatous eyes. J Ocul Pharmacol Ther. 2011;27:477–480. doi: 10.1089/jop.2010.0100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yamamoto N, Itonaga K, Marunouchi T, Majima K. Concentration of transforming growth factor β2 in aqueous humor. Ophthalmic Res. 2005;37:29–33. doi: 10.1159/000083019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ozcan AA, Ozdemir N, Canataroglu A. The aqueous levels of TGF-β2 in patients with glaucoma. Int Ophthalmol. 2004;25:19–22. doi: 10.1023/b:inte.0000018524.48581.79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Min SH, Lee TI, Chung YS, Kim HK. Transforming growth factor-β levels in human aqueous humor of glaucomatous, diabetic and uveitic eyes. [Accessed June 13, 2014];Korean J Ophthalmol. 2006 20:162–165. doi: 10.3341/kjo.2006.20.3.162. Available at: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2908840/pdf/kjo-20-162.pdf. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ochiai Y, Ochiai H. Higher concentration of transforming growth factor-β in aqueous humor of glaucomatous eyes and diabetic eyes. Jpn J Ophthalmol. 2002;46:249–253. doi: 10.1016/s0021-5155(01)00523-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Robertson JV, Golesic E, Gauldie J, West-Mays JA. Ocular gene transfer of active TGF-β induces changes in anterior segment morphology and elevated IOP in rats. [Accessed June 13, 2014];Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2010 51:308–318. doi: 10.1167/iovs.09-3380. Available at: http://www.iovs.org/content/51/1/308.full.pdf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shepard AR, Millar JC, Pang IH, Jacobson N, Wang WH, Clark AF. Adenoviral gene transfer of active human transforming growth factor-β2 elevates intraocular pressure and reduces outflow facility in rodent eyes. [Accessed June 13, 2014];Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2010 51:2067–2076. doi: 10.1167/iovs.09-4567. Available at: http://www.iovs.org/content/51/4/2067.full.pdf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fleenor DL, Shepard AR, Hellberg PE, Jacobson N, Pang IH, Clark AF. TGFβ2-induced changes in human trabecular meshwork: implications for intraocular pressure. [Accessed June 13, 2014];Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2006 47:226–234. doi: 10.1167/iovs.05-1060. Available at: http://www.iovs.org/content/47/1/226.full.pdf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gottanka J, Johnson DH, Martus P, Lütjen-Drecoll E. Severity of optic nerve damage in eyes with POAG is correlated with changes in the trabecular meshwork. J Glaucoma. 1997;6:123–132. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lütjen-Drecoll E, Shimizu T, Rohrbach M, Rohen JW. Quantitative analysis of “plaque material” in the inner- and outer wall of Schlemm's canal in normal- and glaucomatous eyes. Exp Eye Res. 1986;42:443–455. doi: 10.1016/0014-4835(86)90004-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schwinn MK, Gonzalez JM, Jr, Gabelt BT, Sheibani N, Kaufman PL, Peters DM. Heparin II domain of fibronectin mediates contractility through an α4β1 co-signaling pathway. Exp Cell Res. 2010;316:1500–1512. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2010.03.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Faralli JA, Newman JR, Sheibani N, Dedhar S, Peters DM. Integrin-linked kinase regulates integrin signaling in human trabecular meshwork cells. [Accessed June 13, 2014];Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2011 52:1684–1692. doi: 10.1167/iovs.10-6397. Available at: http://www.iovs.org/content/52/3/1684.full.pdf. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mäepea O, Bill A. The pressures in the episcleral veins, Schlemm's canal and the trabecular meshwork in monkeys: effects of changes in intraocular pressure. Exp Eye Res. 1989;49:645–663. doi: 10.1016/s0014-4835(89)80060-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Buller C, Johnson D. Segmental variability of the trabecular meshwork in normal and glaucomatous eyes. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1994;35:3841–3851. Available at: http://www.iovs.org/content/35/11/3841.full.pdf. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gong H, Ruberti J, Overby D, Johnson M, Freddo TF. A new view of the human trabecular meshwork using quick-freeze, deep-etch electron microscopy. Exp Eye Res. 2002;75:347–358. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Alvarado JA, Yun AJ, Murphy CG. Juxtacanalicular tissue in primary open angle glaucoma and in nonglaucomatous normals. Arch Ophthalmol. 1986;104:1517–1528. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1986.01050220111038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Johnson M, Chan D, Read AT, Christensen C, Sit A, Ethier CR. The pore density in the inner wall endothelium of Schlemm's canal of glaucomatous eyes. [Accessed June 13, 2014];Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2002 43:2950–2955. Available at: http://www.iovs.org/content/43/9/2950.full.pdf. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bárány EH, Scotchbrook S. Influence of testicular hyaluronidase on the resistance to flow through the angle of the anterior chamber. Acta Physiol Scand. 1954;30:240–248. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-1716.1954.tb01092.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gaasterland DE, Pederson JE, MacLellan HM, Reddy VN. Rhesus monkey aqueous humor composition and a primate ocular perfusate. [Accessed June 13, 2014];Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1979 18:1139–1150. Available at: http://www.iovs.org/content/18/11/1139.full.pdf. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Erickson-Lamy K, Rohen JW, Grant WM. Outflow facility studies in the perfused bovine aqueous outflow pathways. Curr Eye Res. 1988;7:799–807. doi: 10.3109/02713688809033211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yan DB, Trope GE, Ethier CR, Menon IA, Wakeham A. Effects of hydrogen peroxide-induced oxidative damage on outflow facility and washout in pig eyes. [Accessed June 13, 2014];Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1991 32:2515–2520. Available at: http://www.iovs.org/content/32/9/2515.full.pdf. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Erickson-Lamy K, Schroeder AM, Bassett-Chu S, Epstein DL. Absence of time-dependent facility increase (“washout”) in the perfused enucleated human eye. [Accessed June 13, 2014];Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1990 31:2384–2388. Available at: http://www.iovs.org/content/31/11/2384.full.pdf. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lei Y, Overby DR, Boussommier-Calleja A, Stamer WD, Ethier CR. Outflow physiology of the mouse eye: pressure dependence and washout. [Accessed June 13, 2014];Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2011 52:1865–1871. doi: 10.1167/iovs.10-6019. Available at: http://www.iovs.org/content/52/3/1865.full.pdf. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.McMenamin PG, Lee WR. Effects of prolonged intracameral perfusion with mock aqueous humour on the morphology of the primate outflow apparatus. Exp Eye Res. 1986;43:129–141. doi: 10.1016/s0014-4835(86)80051-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Overby D, Gong H, Qiu G, Freddo TF, Johnson M. The mechanism of increasing outflow facility during washout in the bovine eye. [Accessed June 13, 2014];Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2002 43:3455–3464. Available at: http://www.iovs.org/content/43/11/3455.full.pdf. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Scott PA, Overby DR, Freddo TF, Gong H. Comparative studies between species that do and do not exhibit the washout effect. Exp Eye Res. 2007;84:435–443. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2006.10.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Johnson M, Shapiro A, Ethier CR, Kamm RD. Modulation of outflow resistance by the pores of the inner wall endothelium. [Accessed June 13, 2014];Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1992 33:1670–1675. Available at: http://www.iovs.org/content/33/5/1670.full.pdf. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bill A, Lütjen-Drecoll E, Svedbergh B. Effects of intracameral Na2EDTA and EGTA on aqueous outflow routes in the monkey eye. [Accessed June 13, 2014];Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1980 19:492–504. Available at: http://www.iovs.org/content/19/5/492.full.pdf. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sabanay I, Gabelt BT, Tian B, Kaufman PL, Geiger B. H-7 effects on the structure and fluid conductance of monkey trabecular meshwork. [Accessed June 13, 2014];Arch Ophthalmol. 2000 118:955–962. Available at: http://archopht.jamanetwork.com/data/Journals/OPHTH/9875/els90042.pdf. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Sabanay I, Tian B, Gabelt BT, Geiger B, Kaufman PL. Functional and structural reversibility of H-7 effects on the conventional aqueous outflow pathway in monkeys. Exp Eye Res. 2004;78:137–150. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2003.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lu Z, Overby DR, Scott PA, Freddo TF, Gong H. The mechanism of increasing outflow facility by rho-kinase inhibition with Y-27632 in bovine eyes. Exp Eye Res. 2008;86:271–281. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2007.10.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Battista SA, Lu Z, Hofmann S, Freddo T, Overby DR, Gong H. Reduction of the available area for aqueous humor outflow and increase in meshwork herniations into collector channels following acute IOP elevation in bovine eyes. [Accessed June 13, 2014];Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2008 49:5346–5352. doi: 10.1167/iovs.08-1707. Available at: http://www.iovs.org/content/49/12/5346.full.pdf. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Swaminathan SS, Oh DJ, Kang MH, Ren R, Jin R, Gong H, Rhee DJ. Secreted protein acidic and rich in cysteine (SPARC)-null mice exhibit more uniform outflow. [Accessed June 13, 2014];Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2013 54:2035–2047. doi: 10.1167/iovs.12-10950. Available at: http://www.iovs.org/content/54/3/2035.full.pdf. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Hann CR, Bahler CK, Johnson DH. Cationic ferritin and segmental flow through the trabecular meshwork. [Accessed June 13, 2014];Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2005 46:1–7. doi: 10.1167/iovs.04-0800. Available at: http://www.iovs.org/content/46/1/1.full.pdf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ethier CR, Chan DWH. Cationic ferritin changes outflow facility in human eyes whereas anionic ferritin does not. [Accessed June 15, 2014];Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2001 42:1795–1802. Available at: http://www.iovs.org/content/42/8/1795.full.pdf. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Lu Z, Zhang Y, Freddo TF, Gong H. Similar hydrodynamic and morphological changes in the aqueous humor outflow pathway after washout and Y27632 treatment in monkey eyes. Exp Eye Res. 2011;93:397–404. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2011.05.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Yang CYC, Liu Y, Lu Z, Ren R, Gong H. Effects of Y27632 on aqueous humor outflow facility with changes in hydrodynamic pattern and morphology in human eyes. [Accessed June 13, 2014];Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2013 54:5859–5870. doi: 10.1167/iovs.12-10930. Available at: http://www.iovs.org/content/54/8/5859.full.pdf. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Keller KE, Bradley JM, Vranka JA, Acott TS. Segmental versican expression in the trabecular meshwork and involvement in outflow facility. [Accessed June 13, 2014];Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2011 52:5049–5057. doi: 10.1167/iovs.10-6948. Available at: http://www.iovs.org/content/52/8/5049.full.pdf. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Zhang Y, Toris CB, Liu Y, Ye W, Gong H. Morphological and hydrodynamic correlates in monkey eyes with laser induced glaucoma. Exp Eye Res. 2009;89:748–756. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2009.06.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Moses RA. The conventional outflow resistances. Am J Ophthalmol. 1981;92:804–810. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(14)75634-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Zhou J, Smedley GT. A trabecular bypass flow hypothesis. J Glaucoma. 2005;14:74–83. doi: 10.1097/01.ijg.0000146360.07540.ml. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Zhou J, Smedley GT. Trabecular bypass; effect of Schlemm canal and collector channel dilation. J Glaucoma. 2006;15:446–455. doi: 10.1097/01.ijg.0000212262.12112.42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Ellingsen BA, Grant WM. Trabeculotomy and sinusotomy in enucleated human eyes. [Accessed June 14, 2014];Invest Ophthalmol. 1972 11:21–28. Available at: http://www.iovs.org/cgi/reprint/11/1/21.pdf. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Peterson WS, Jocson VL. Hyaluronidase effects on aqueous outflow resistance; quantitative and localizing studies in the rhesus monkey eye. Am J Ophthalmol. 1974;77:573–577. doi: 10.1016/0002-9394(74)90473-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Van Buskirk EM. Trabeculotomy in the immature, enucleated human eye. [Accessed June 13, 2014];Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1977 16:63–66. Available at: http://www.iovs.org/content/16/1/63.full.pdf. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Johnson M. What controls aqueous humour outflow resistance? [Accessed June 13, 2014];Exp Eye Res. 2006 82:545–557. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2005.10.011. Available at: http://www.bme.northwestern.edu/markj/PDFofPapers/Johnson2006.pdf. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Grant WM. Experimental aqueous perfusion in enucleated human eyes. Arch Ophthalmol. 1963;69:783–801. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1963.00960040789022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Other Cited Material

- A.Vranka J, Keller KE, Acott T. Extracellular matrix gene expression profiling of high and low flow areas of human trabecular meshwork. [Accessed June 13, 2014];IOVS. 2013 54 ARVO E-Abstract 3566. Available at: http://abstracts.iovs.org//cgi/content/abstract/54/6/3566?sid=c784a366-6ea4-4248-9adc-1e49de32dd69. [Google Scholar]