Abstract

One of the most remarkable chromatin remodeling processes occurs during spermiogenesis, the post-meiotic phase of sperm development during which histones are replaced with sperm-specific protamines to repackage the genome into the highly compact chromatin structure of mature sperm. Here we identify Chromodomain helicase DNA binding protein 5 (Chd5) as a master regulator of the histone-to-protamine chromatin remodeling process. Chd5 deficiency leads to defective sperm chromatin compaction and male infertility in mice, mirroring the observation of low CHD5 expression in testes of infertile men. Chd5 orchestrates a cascade of molecular events required for histone removal and replacement, including histone 4 (H4) hyperacetylation, histone variant expression, nucleosome eviction, and DNA damage repair. Chd5 deficiency also perturbs expression of transition proteins (Tnp1/Tnp2) and protamines (Prm1/2). These findings define Chd5 as a multi-faceted mediator of histone-to-protamine replacement and depict the cascade of molecular events underlying chromatin remodeling during this process of extensive chromatin remodeling.

Spermatogenesis is an intricate biological process that transforms diploid spermatogonial stem cells into haploid spermatozoa in seminiferous tubules of testis. It consists of three major phases: mitosis, meiosis and spermiogenesis1. Spermatogonial stem cells first multiply by repeated rounds of mitosis and differentiate into primary spermatocytes, which subsequently undergo meiosis and become haploid round spermatids. Round spermatids then mature into highly specialized spermatozoa through spermiogenesis, the final phase of spermatogenesis1. During spermiogenesis, round spermatids undergo a number of characteristic changes including elongation and condensation of the nucleus, formation of the acrosome and flagellum, and removal of cytoplasm2. In mouse, spermatogenesis is subdivided into twelve stages (stage I-XII) whereas spermiogenesis is further divided into 16 steps (step 1-16) mainly defined by changes in acrosome structure and nuclear morphology of the maturing spermatids1,3-5.

Extensive chromatin remodeling occurs during spermiogenesis, which results in the majority of nucleosomal histones being replaced by sperm-specific basic proteins, initially transition proteins, and ultimately protamines6. Protamines are distinct from histones, packaging the sperm genome into a distinct toroid chromatin structure7. This dramatic histone-to-protamine remodeling repackages the sperm genome into a chromatin structure that is six-fold or more compact than that of somatic cells, and is essential for normal sperm development6,8. Given its extensive degree of chromatin remodeling, spermiogenesis offers a unique process to study mechanisms of chromatin remodeling. However, this process is currently understudied and still poorly understood, mainly due to the complexity of the process itself and lack of in vitro experimental systems for studying it. In particular, chromatin remodelers are believed to be essential for facilitating the extensive degree of chromatin remodeling during spermiogenesis, but their roles in this process are not well elucidated. In this study, we discovered that Chromodomain helicase DNA binding protein 5 (Chd5) plays an orchestrating role in the histone-to-protamine remodeling process during spermiogenesis. Chd5 is a member of the CHD family of chromatin remodelers, which we identified as a dosage-sensitive tumor suppressor9. While recent studies reveal that Chd5 binds unmodified histone 3 (H3) via its dual plant homeodomains10,11 and that this interaction is essential for tumor suppression10, the ability of Chd5 to mediate chromatin dynamics in the context of normal cells is not well understood. We find that Chd5 is highly expressed during spermiogenesis and plays essential roles during sperm development. Inactivation of Chd5 in mice leads to sperm chromatin compaction defects and male infertility. We reveal that Chd5 both mediates a cascade of molecular events for histone removal and modulates the homeostasis of transition proteins and protamines, identifying Chd5 as a master regulator of the histone-to-protamine chromatin remodeling process during spermiogenesis.

Results

Chd5 is expressed in spermatids during spermiogenesis

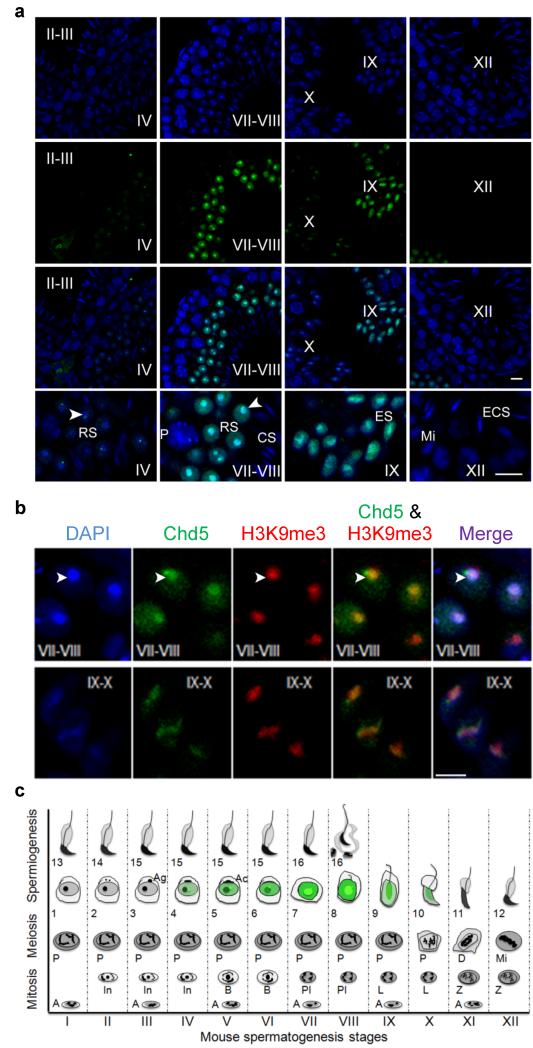

Using immunofluorescence analyses with a previously validated antibody specific for Chd510,12 we found that Chd5 is expressed in mouse testes specifically during spermiogenesis (Fig. 1, Supplementary Fig. 1). Chd5 was first detectable after meiosis, when it was expressed within nuclei of step 4 spermatids (Fig. 1). At this phase, Chd5 was weakly expressed throughout the nucleus but was highly expressed in an intense focal spot near the chromocenter, a cluster of centromeres and pericentromeric heterochromatin13. Chd5 expression peaked at steps 7-8, when it was expressed robustly throughout the nucleus and was enriched in the chromocenter, where Chd5 co-localized with the heterochromatin mark H3K9me3, and was expressed in a pattern similar to that of the repressive histone mark H3K27me3 (Fig. 1b, Supplementary Fig. 2). Chd5 expression decreased after step 9, when it remained enriched in heterochromatin, and was not detectable after step 10 (Fig. 1). The Chd5-intense focal spot juxtaposed to the edge of the chromocenter was present in round spermatids from steps 4-8, and was positioned at the junction between the chromocenter and the post-meiotic sex chromosome, both of which are DAPI-intense sub-nuclear structures within spermatids (Fig. 1, Supplementary Fig. 3a)14. In contrast to the chromocenter, the Chd5-intense focal spot was DAPI-weak and was negative for H3K9me3 (Fig. 1b, Supplementary Fig. 3a), suggesting that it marks transcriptionally active chromatin. We speculated that the Chd5-intense foci may be within nucleoli. Co-immunostaining of Chd5 with the nucleolar marker fibrillarin showed that the Chd5-intense spot was near the nucleolus in many spermatid nuclei, but was clearly separated in others (Supplementary Fig. 3b), raising the possibility that Chd5 transiently associates with the nucleolus. These findings indicate that Chd5 is expressed specifically in nuclei of round and early elongating spermatids during spermiogenesisis where it is primarily enriched in heterochromatic regions, and that Chd5 is also expressed in an intense focal spot in a non-heterochromatic region juxtaposed to the chromocenter.

Figure 1. Chd5 is expressed in step 4 to 10 spermatids and is enriched in heterochromatin during spermiogenesis.

Roman numerals indicate the spermatogenic stages of the tubules in wild type testes sections. (a) Blue, DAPI; Green, Chd5; RS, round spermatid; ES, elongating spermatid; ECS, elongating and condensing spermatid; CS, condensed spermatid; P, pachytene spermatocyte; Mi, meiotic division. Arrow heads mark the chromocenter. Scale bar, 10 μm. (b) Chd5 is enriched in DAPI-intense heterochromatic regions, and co-localizes with heterochromatin marker H3K9me3. Top panel, step 7-8 round spermatids; bottom panel, step 9-10 elongating spermatids. Arrow heads mark the chromocenter. Scale bar, 5 μm. (c) Schematic of Chd5 expression during spermatogenesis. Spermatogenesis is divided into twelve stages (stage I-XII) in mouse and each stage has a distinct cellular composition. Spermiogenesis, the maturation process of haploid spermatids, is divided into 16 steps (step 1-16). Green marks Chd5 protein expression. Chd5 is specifically expressed in spermatids from step 4 to 10, with peak expression in step 7-8 round spermatids, where Chd5 is enriched in the heterochromatic chromocenter. A focus of intense Chd5 protein expression is located adjacent to the junction of the chromocenter and the post-meiotic sex chromosomes in step 4-8 spermatids. Spermatogonia (A, In, B); Spermatocyte (Pl, preleptotene; L, leptotene; Z, zygotene; P, pachytene; D, diakinesis; Mi, meiotic division); Ag, acrosomic granule; Ac, acrosomic cap. The diagram is drawn based on the illustration of Dr. Rex Hess et al. in Chapter 1, Molecular Mechanisms in Spermatogenesis, Springer, 2008.

Chd5 deficiency impairs sperm development and fertility

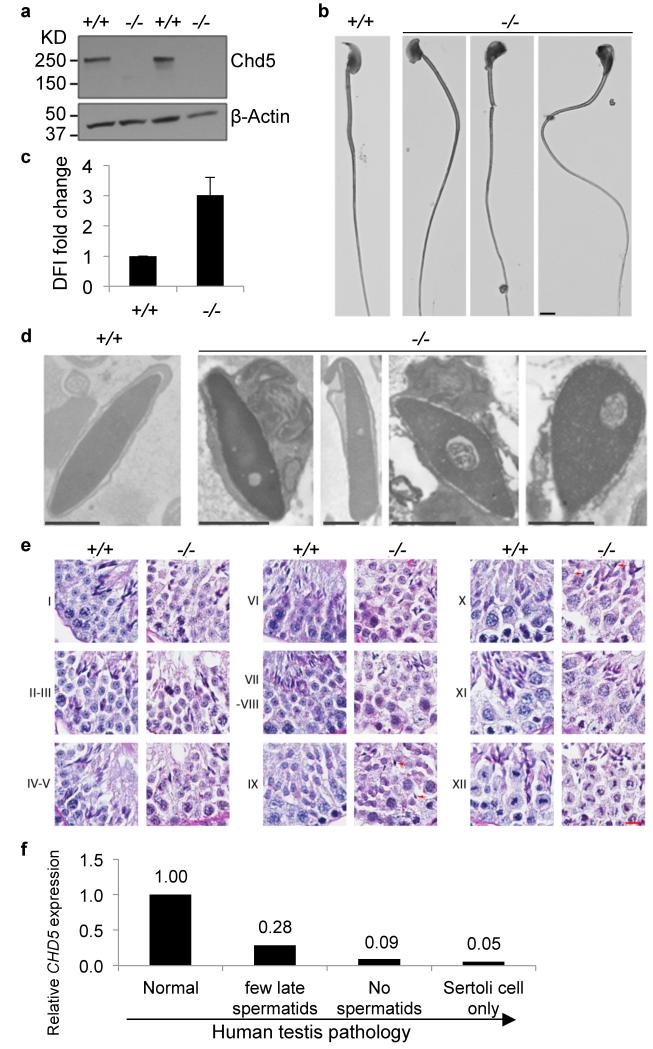

The dynamics of Chd5 expression during spermiogenesis indicated that it might play a functional role in chromatin remodeling during spermatid maturation. To explore this possibility, we generated Chd5 deficient mice carrying the Chd5Aam1 null allele (Supplementary Fig. 4). Western blot analyses using a validated antibody10 recognizing a part of Chd5 protein not disrupted by the gene targeting, demonstrated that the Chd5 protein was not detected in testes of Chd5Aam1 homozygotes (Fig. 2a). Chd5Aam1−/− mice were viable and grossly normal. Mating tests revealed that whereas Chd5Aam1−/− female mice and Chd5Aam1+/- mice of both genders were fertile, Chd5Aam1−/− males were either sub-fertile or sterile (Supplementary Table 1). Chd5Aam1−/− mice had significantly lower sperm counts, and the sperm that were produced had compromised motility and a higher proportion of morphological abnormalities (Table 1, Fig. 2b; Supplementary Table 2). Using in vitro fertilization (IVF), we found that Chd5Aam1−/− sperm failed to fertilize wild type oocytes (Supplementary Table 3). Although it might be expected that some functional sperm from sub-fertile Chd5Aam1−/− mice should be able to fertilize oocytes, none of the sperm obtained from three different Chd5Aam1−/− mice were able to generate blastocysts in vitro. This may be because each of the three males tested happened to be sterile rather then sub-fertile, or, that in vitro fertilization conditions compromised the sperm that would have been able to fertilize oocytes under in vivo conditions. A possible explanation for the range of severity of the fertility phenotype in different mice was genetic background, as 129Sv embryonic stem cells were used to generate the Chd5Aam1 allele, with mice being backcrossed for over four generations onto the C57BL/6 background prior to heterozygotes being intercrossed. To determine whether genetic background affected fertility, we established a second Chd5-deficient mouse model (carrying the Chd5Tm1b null allele15) that was in a 100% pure C57BL/6 genetic background, and assessed male fertility (Supplementary Fig. 5, Supplementary Table 4). We found that Chd5Tm1b−/− male mice were also either sterile or subfertile. Another Chd5-deficient mouse model in a pure 129E background also showed that homozygous male mice exhibited variable pathology ranging from absence of sperm to near normal sperm count, although six homozygous males tested did not produce any progeny over the 2-month period analyzed16. These data suggest that Chd5 deficiency compromises sperm production and male fertility and that this phenotype exhibits inherent variability in different individuals.

Figure 2. Chd5 deficiency leads to defective spermatogenesis and chromatin condensation.

(a) Western blot analyses indicates that Chd5 protein is not detectable in Chd5Aam1−/− (−/−) testis. A validated antibody 10 raised against a peptide for amino acids 1524-1705 of mouse Chd5 (which is not disrupted by gene targeting), was used for the Western blotting. β-Actin serves as a loading control. (b) Representative abnormal head morphology of Chd5Aam1−/− sperm. Scale bar, 20 μm. (c) SCSA revealed impaired chromatin integrity of Chd5Aam1−/− sperm. DFI, DNA Fragmentation Index (see Methods Summary). Data are presented as mean ± s.d. from four independent experiments. (d) Transmission electron microscopy analyses of sperm from Chd5Aam1+/+ and Chd5Aam1−/− caudal epididymi. Chromatin is homogenously condensed in Chd5Aam1+/+ sperm, but appears loose and uneven with fibrillar texture and contains abnormal vacuoles in Chd5Aam1−/− sperm nuclei. Scale bar, 1 μm. (e) Staged comparison of Periodic Acid-Schiff (PAS) stained Chd5Aam1+/+ and Chd5Aam1−/− testes. Roman numerals indicate the stages of the seminiferous tubules. A decrease in the number of elongated spermatids, especially at stage VII-VIII, is evident in Chd5Aam1−/− tubules. Arrows in stage IX and X mark abnormal retention of condensed spermatids. Scale bar, 1 μm. (f) Relative CHD5 expression in human testis with normal vs. clinically defined abnormal spermatogenesis. Data are derived from published microarray dataset (ArrayExpress: E-TABM-234) of 39 human testis biopsy samples from 29 men with highly defined testicular pathologies and 10 men with normal spermatogenesis. RNA was prepared from the testis biopsies and analyzed for gene expression using Affymetrix GeneChip. Data were analyzed through NextBio18. Arrow indicates increased severity of spermatogenic defect.

Table 1.

Reduced sperm counts and motility in Chd5Aam1−/− mice

| Genotype | N | Sperm/caudal epididymis (×106) |

All motile sperm (%) |

Progressive motile sperm (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chd5 Aam1+/+ | 7 | 5.52±1.13 | 62.3±5.4 | 48.6±11.3 |

| Chd5 Aam1+/− | 4 | 6.51±0.68 | 66.0±3.8 | 52.8±2.3 |

| Chd5 Aam1−/− | 11 | 2.74±0.68 | 42.4±10.3 | 21.0±5.7 |

| p (+/+ vs +/−) | 0.103 | 0.228 | 0.375 | |

| p (+/+ vs −/−) | 0.0002* | 0.0055* | 0.0004* | |

N indicates the number of mice used for the indicated sperm analyses. p value is two-tail Student’s t-test result between the indicated genotypes.

indicates statistical significance. Data are presented as mean ± s.d. +/+, Chd5Aam1+/+; −/−, Chd5Aam1−/−.

To assess chromatin integrity in sperm from Chd5-deficient mice, we used the sperm chromatin structure assay (SCSA)(Fig. 2c). SCSA revealed that DNA fragmentation was enhanced in Chd5Aam1−/− sperm, reflecting a compromise in chromatin integrity17. Consistent with this finding, transmission electron microscopy showed that whereas chromatin within nuclei of wild type sperm is homogeneously condensed, less condensed chromatin with a punctate texture and uneven density, as well as the presence of abnormal vacuoles, were observed in nuclei of Chd5Aam1−/− sperm (Fig. 2d). These findings show that Chd5 deficiency leads to defective chromatin compaction in sperm.

Since compromised fertility can be caused by a deregulation of sex hormones, we investigated this possibility (Supplementary Fig. 6). However, we did not detect a significant alteration in sex hormones in Chd5Aam1−/− male mice relative to controls. Histological analyses of testes revealed that seminiferous tubules of Chd5Aam1−/− mice contained fewer elongated spermatids relative to controls, with an abnormal retention of condensed spermatids within stage IX and X tubules (Fig. 2e, Supplementary Fig. 7). The extent of histological abnormalities varied among individual Chd5Aam1−/− mice (Supplementary Fig. 7), in agreement with the variable severity of infertility observed in male Chd5-deficient mice. In contrast to post-meiotic defects, we did not observe differences in spermatogenic cells (spermatogonia, spermatocytes, round spermatids) or in somatic cells (Sertoli cells, Leydig cells) in Chd5Aam1−/− testes (Fig. 2e, Supplementary Fig. 7). These findings indicate that Chd5 deficiency disrupts the elongation and condensation steps of post-meiotic sperm maturation, consistent with Chd5’s peak of expression in step 7-8 round spermatids, the phase that immediately precedes initiation of chromatin remodeling.

To determine whether our findings from Chd5 deficient mice might be relevant to human cases of male infertility, we analyzed a previously established gene expression dataset of testes biopsies from 39 men (29 men with highly defined testicular pathology, and 10 men with normal spermatogenesis)18. This analysis revealed that men with spermatogenic defects had lower CHD5 expression relative to controls and that the clinical grade of spermatogenic defect correlated inversely with CHD5 expression (Fig. 2f). While this is a correlation rather than evidence for causality, it suggests that future efforts should be made to determine whether compromised CHD5 contributes to male infertility in humans.

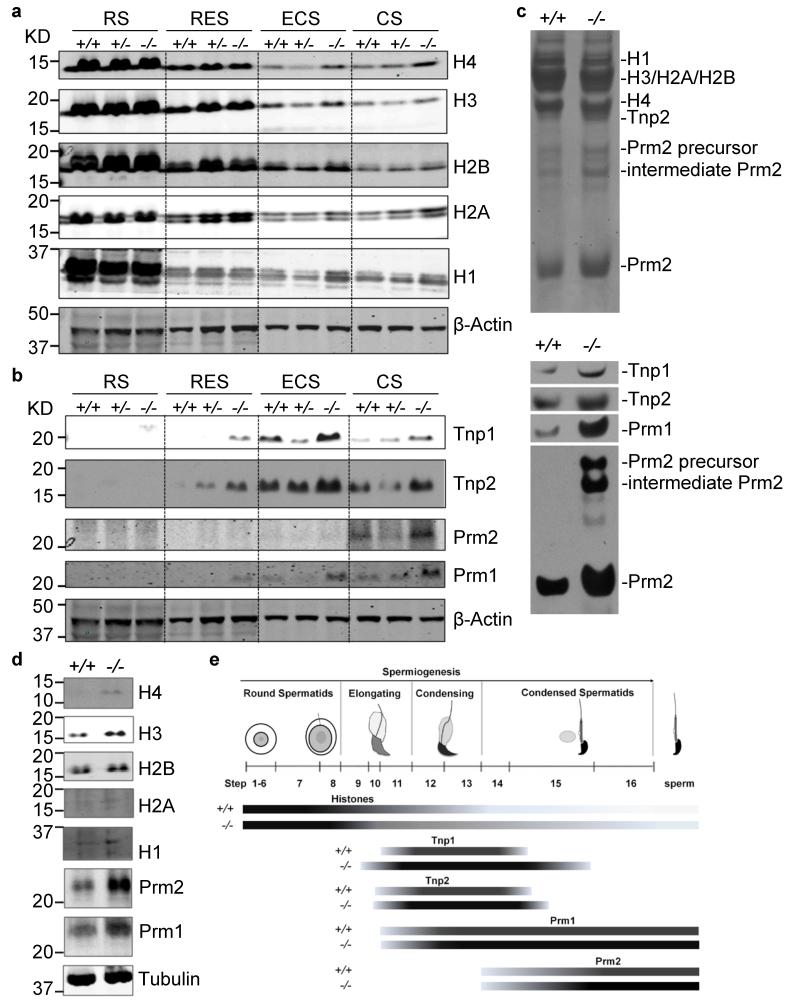

Chd5 deficiency disrupts histone-to-protamine replacement

During mammalian spermiogenesis, the majority of canonical histones are removed and replaced by histone variants and transition proteins, which are subsequently replaced by protamines6,7,19,20. This histone-to-protamine replacement process repackages the sperm genome at least six-fold more compact than its somatic counterpart8. To define the mechanism whereby Chd5 deficiency compromises chromatin compaction during spermiogenesis, we used western blotting to assess expression of a panel of somatic histones, transition proteins, and protamines in elutriation-purified spermatids at different steps of spermiogenesis (Supplementary Fig. 8). The core nucleosomal histones (H1, H2A, H2B, H3, and H4) were quickly depleted after the round spermatid steps in wild type testes, with minimal retention in condensing and condensed spermatids (Fig. 3a). In contrast, these core histones were retained to a higher extent in Chd5Aam1−/− differentiated spermatids, which implied ineffective histone removal. In addition, transition proteins (Tnp1 and Tnp2) and protamines (Prm1 and Prm2) had elevated expression in differentiated Chd5Aam1−/− spermatids (Fig. 3b, c), likely contributing to impaired fertility of Chd5Aam1−/− mice, as precise control of levels of Prm1 and Prm2 are critical for male fertility21,22. Prm2 is first translated as a precursor protein that is subsequently processed into mature Prm2 through a multistep proteolytic cleavage. In Chd5Aam1−/− spermatids, there was enhanced expression of the Prm2 precursor and partially processed Prm2 was present, indicating a defect in Prm2 processing, which may be because the overproduction of Prm2 in Chd5Aam1−/− spermatids exceeds the processing capacity of the cells. In addition, both Tnp1 and Tnp2 deficiency have been shown to increase levels of the Prm2 precursor and partially processed forms of Prm223,24. Thus, the abnormal elevation of Tnp1 and Tnp2 in Chd5Aam1−/− spermatids may also contribute to defective Prm2 processing. Consistent with the observation in spermatids, western blotting of lysates from mature sperm also revealed enhanced retention of core nucleosomal histones and elevated Prm1 and Prm2 expression in Chd5Aam1−/− sperm (Fig. 3d). Furthermore, immunofluorescent analyses of testes showed enhanced expression of Tnp1, Tnp2, Prm1 and Prm2 in Chd5Aam1−/− spermatids (Fig. 3e, Supplementary Figs. 9-12). In addition, Tnp1 was precociously expressed in steps 9-10 spermatids and had extended expression until step 15 spermatids in Chd5Aam1−/− testes. These findings indicate that Chd5 deficiency perturbs the histone-to-protamine transition that occurs during spermiogenesis, leading to aberrant retention of nucleosomal histones and elevated levels of transition proteins and protamines.

Figure 3. Chd5 modulates histone removal and homeostasis of transition proteins and protamines.

(a, b) Western blot analyses of protein lysates from purified spermatids at different spermiogenic stages. RS, round spermatids; RES, round and early elongating spermatids; ECS, elongating and condensing spermatids; CS, condensed spermatids. Increased retention of histones (H4, H3, H2B, H2A and H1) as well as elevated transition proteins (Tnp1, Tnp2) and protamines (Prm1, Prm2) are observed in elongating, condensing and condensed spermatids, but not in round spermatids of Chd5Aam1−/− (−/−) testis. β-Actin serves as a loading control. Levels of histones, transition proteins and protamines in Chd5Aam1+/- spermatids are in general similar to the levels in Chd5Aam1+/+ counterparts, with some variability among different Chd5Aam1+/- samples. The alterations in H3 in ECS, and alterations in Tnp2 and Prm2 in CS, are not consistently observed. (c) Top panel, Coomassie blue staining of basic protein extracts from Chd5Aam1+/+ and Chd5Aam1−/− sonication-resistant spermatids (SRS) separated using urea-acid gel electrophoresis. Equal amounts of proteins are loaded. Bottom panel, Western blot analyses of the same basic protein extracts show an increase in Tnp1, Tnp2, Prm1 and Prm2 in Chd5Aam1−/− SRS. The increase in the Prm2 precursor and intermediate Prm2 indicate deficient processing of the Prm2 precursor in Chd5Aam1−/− SRS. (d) Western blot analyses of protein lysates of sperm prepared from caudal epididymi of Chd5Aam1+/+ (+/+) and Chd5Aam1−/− (−/−) mice reveal increased retention of nucleosomal histones and elevated Prm1 and Prm2 in Chd5Aam1−/− sperm. H4, H2A and H1 are barely detectable in Chd5Aam1+/+ sperm, but are detected in Chd5Aam1−/− sperm. H3 and H2B are detectable in both Chd5Aam1+/+ and Chd5Aam1−/− sperm, but are higher in Chd5Aam1−/− sperm. Tubulin serves as a loading control. (e) Illustration of the dynamics of histones, transition proteins and protamines during spermiogenesis in Chd5Aam1+/+ (+/+) and Chd5Aam1−/− (−/−) testes. For each nuclear protein, the darker color of the bar in Chd5Aam1−/− testis indicates stronger expression of the protein at the indicated spermatogenic steps relative to Chd5Aam1+/+ counterparts.

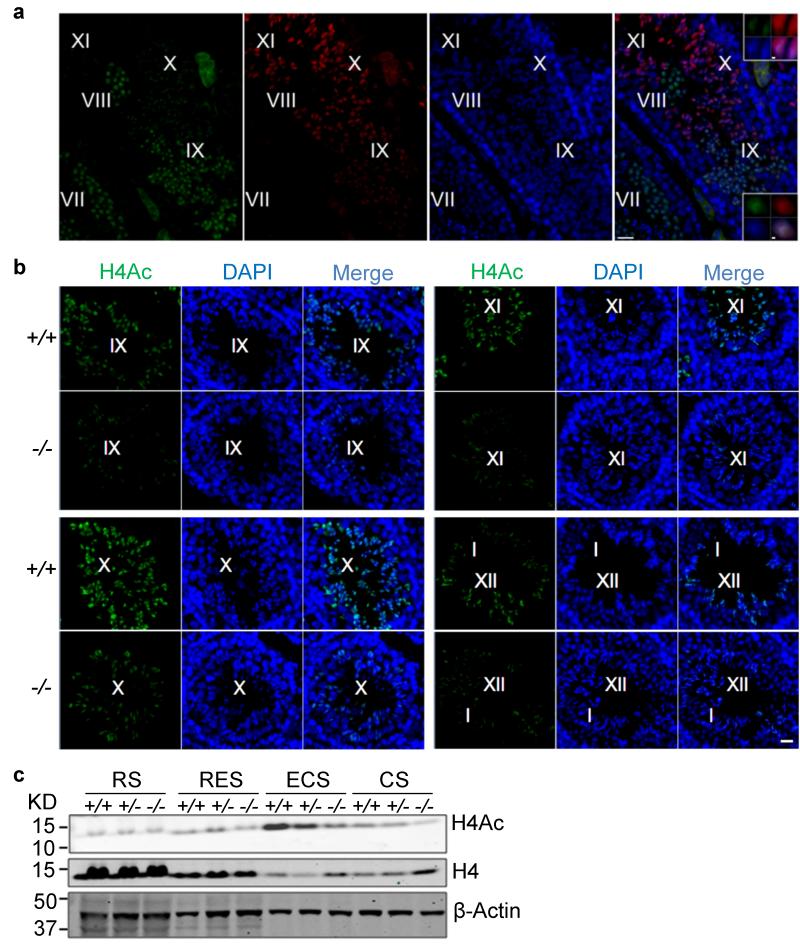

Chd5 mediates H4Ac, nucleosome eviction and DNA repair

To assess the mechanism of how Chd5 deficiency leads to aberrant histone removal we focused on H4 hyperacetylation, a molecular event occurring in early elongating spermatids that is essential for histone-to-protamine replacement in Drosophila25, and considered the same for spermiogenesis in mammals6,25,26. Using immunofluorescence, we determined that Chd5 had similar expression dynamics as H4 hyperacetylation during spermiogenesis, but immediately preceded it (Fig. 4a). In step 9-10 spermatids, Chd5 co-localized with H4 acetylation, suggesting that Chd5 modulates H4 hyperacetylation during spermiogenesis (Fig. 4a). Consistent with this hypothesis, immunofluorescent analyses revealed that H4 acetylation was compromised in Chd5Aam1−/− spermatids (Fig. 4b). In Chd5Aam1+/+ testis, H4 hyperacetylation was detected in step 9 spermatids and showed peak expression in step 10-12. H4 acetylation decreased in step 13 spermatids, and was not detectable at later steps. Whereas H4 acetylation was detected within step 9-13 spermatids of Chd5Aam1−/− testis, its expression was substantially reduced in Chd5Aam1+/+ spermatids. Furthermore, western blotting of lysates from elutriation-purified spermatid fractions showed that whereas more total H4 was retained, H4Ac was severely compromised in differentiated Chd5Aam1−/− spermatids (Fig. 4c). Consistent with the findings in Chd5Aam1−/− mice, Chd5Tm1b−/− testes also showed compromised histone H4 acetylation (Supplementary Fig. 13). These findings indicate that acetylated H4 is compromised in Chd5-deficient testes.

Figure 4. Chd5 deficiency leads to compromised H4 acetylation during spermiogenesis.

(a) Co-staining of Chd5 and H4 acetylation (H4Ac) in wild type testes. Roman numerals indicate spermatogenic stages of the marked tubular areas. Top and bottom inserts show higher magnification view of step 10 and step 9 spermatids, respectively. Both Chd5 and H4Ac are enriched in DAPI-intense regions within nuclei of step 9 and 10 spermatids in wild type testes. H4Ac is detected by a mouse monoclonal antibody against pan-H4K5/8/12/16Ac. Scale bars, 20 μm in main panels and 1 μm for inserts. (b) Immunofluorescence analyses of H4 acetylation in Chd5Aam1+/+ (+/+) and Chd5Aam1−/−(−/−) seminiferous tubules. Roman numerals indicate spermatogenic stages of the marked tubules. H4 hyperacetylation starts at step 9 spermatids of stage IX tubules, exhibits peak expression from step10 of stage X tubules to step 12 spermatids of stage XII tubules and decreases in step 13 spermatids in stage I tubules in Chd5Aam1+/+ (+/+) testis. H4 acetylation is weaker from step 9 to 13 spermatids in Chd5Aam1−/− (−/−) testis than in the Chd5Aam1+/+ counterparts. H4Ac was detected by a rabbit polyclonal antibody against pan-acetylation of H4. Scale bar, 20 μm. (c) Western blot analyses of purified spermatids at different spermiogenic stages. Histone H4 becomes transiently hyperacetylated in ECS of Chd5Aam1+/+ (+/+) testes, but not in ECS of Chd5Aam1−/− (−/−) testes. H4Ac was detected by a rabbit polyclonal antibody against pan-acetylation of H4. β-Actin serves as a loading control. RS, round spermatids; RES, round and early elongating spermatids; ECS, elongating and condensing spermatids; CS, condensed spermatids.

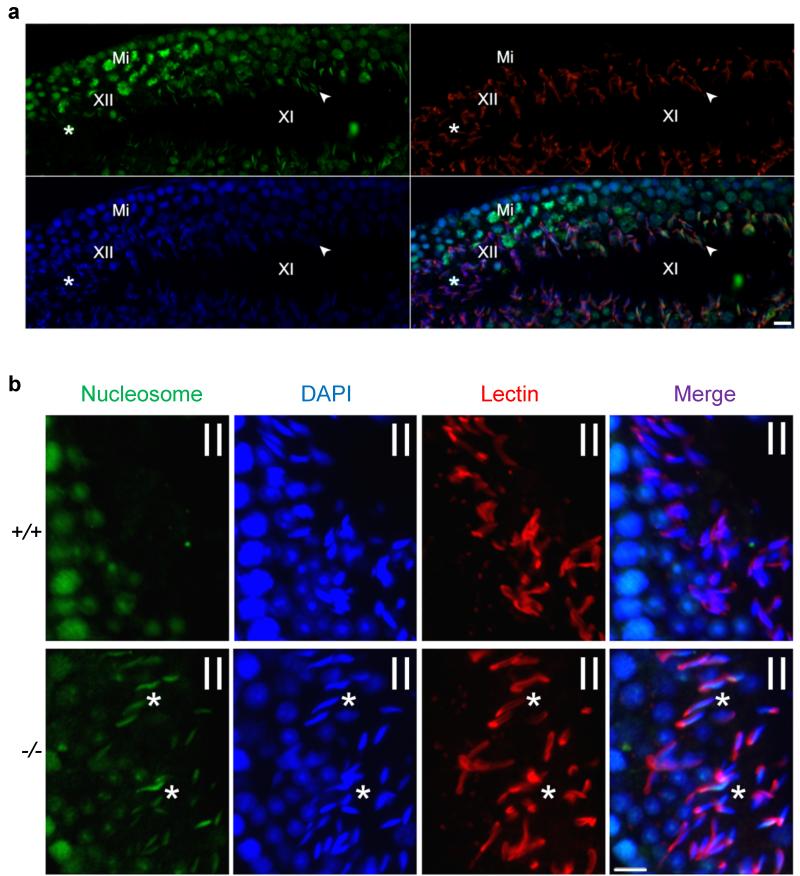

Following H4 hyperacetylation, acetylated histone tails are recognized by Brdt, a testis-specific member of the BRD bromodomain containing protein family that has been shown to induce eviction of nucleosomes6,27,28. However, how Brdt mediates nucleosome eviction is not clear. Likely, Brdt recruits chromatin remodelers to remodel and evict hyperacetylated nucleosomes. We therefore asked whether the compromised H4 acetylation and Chd5 deficiency perturbed nucleosome eviction in Chd5Aam1−/− spermatids. Using an antibody specific for intact nucleosomes29, we found that nucleosomes were detectable through step 11 of spermatid maturation in wild type testes, but were depleted at later steps (Fig. 5a). However, we found that nucleosomes were aberrantly retained in Chd5Aam1−/− spermatids as late as step 14 (Fig. 5b), indicating that nucleosomes were ineffectively evicted. Thus, both H4 acetylation and nucleosome eviction are compromised by Chd5 deficiency.

Figure 5. Chd5 deficiency leads to inefficient nucleosome eviction during spermiogenesis.

Roman numerals indicate the spermatogenic stages of tubular areas. (a) Nucleosomes are detected in step 11 spermatids (indicated by arrow head) of stage XI seminiferous tubules, but are depleted afterwards and not detectable in step 12 spermatids (indicated by *) of stage XII seminiferous tubule in of wild type testes. Green, nucleosomes; Red, Lectin (visualizing acrosome for staging seminiferous tubules); Blue, DAPI; Mi, meiotic figure, a hallmark of stage XII tubules. (b) Immunostaining for nucleosomes show that nucleosomes are retained in as late as step 14 spermatids of stage II seminiferous tubules in Chd5Aam1−/− (−/−) testes, while absent in the Chd5Aam1+/+ (+/+) counterpart. Asterisks (*) mark nucleosome-positive condensing spermatids (step 14) in Chd5Aam1−/− tubules. Scale bar, 10 μm.

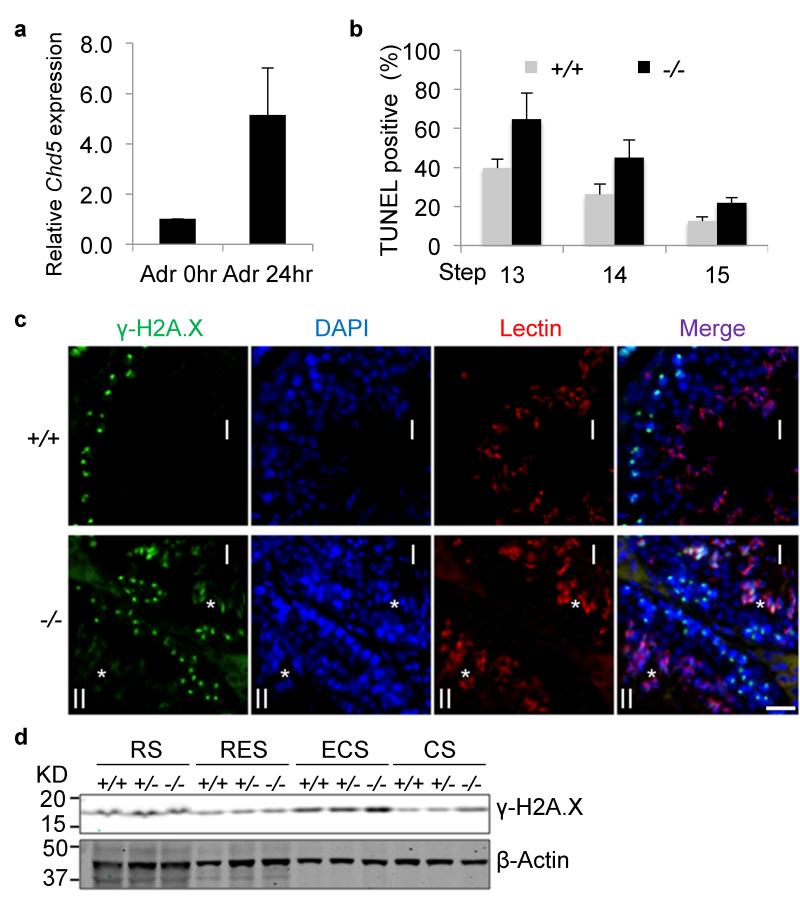

Nucleosome eviction generates DNA supercoiling tension that needs to be relieved. Previous studies indicate that topoisomerase II beta (Top2β) catalyzes resolution of such supercoils in elongating spermatids, during which double-strand breaks (DSBs) are generated. A DNA damage response is then triggered to repair the DSBs in order to maintain genome integrity30-33. We found that Chd5 expression is induced by DNA damage (Fig. 6a), suggesting that Chd5 plays a role in the DNA damage response as well. Indeed, TUNEL assays revealed an increase of DNA breaks in differentiated Chd5Aam1−/− spermatids, most notably at steps 13-14 (Fig. 6b), a time point when most DNA breaks are repaired in wild type testes. In agreement with this finding, immunofluorescent analyses showed that whereas γ-H2A.X (a marker for the DSB-activated DNA damage response) is cleared in wild type spermatids after step 12, it is detected in Chd5Aam1−/− spermatids as late as step14 (Fig. 6c). Western blot analyses further confirmed an increase of γ-H2A.X in differentiated Chd5Aam1−/− spermatids (Fig. 6d). Together, these findings indicate that Chd5 deficiency impairs H4 hyperacetylation, nucleosome eviction, and DNA damage repair during spermiogenesis.

Figure 6. Increased DNA damage in Chd5Aam1−/− spermatids.

(a) qRT-PCR analyses shows that Chd5 expression is induced approximately 5 fold when wild type mouse embryonic fibroblasts are treated with the DNA damaging agent adriamycin (0.4 μg/ml) for 24 hours. Results are normalized to Actb and the expression level at 0 hours is defined as 1. Data are presented as mean ± s.d. from three independent experiments. Adr, Adriamycin. (b) Increased TUNEL-positive condensing spermatids (step 13-15) in Chd5Aam1−/− testis. Data are presented as mean ± s.d. from three independent experiments. (c) Immunofluorescence analyses of γ-H2A.X in Chd5Aam1+/+ (+/+) and Chd5Aam1−/−(−/−) seminiferous tubules. Asterisks (*) mark γ-H2A.X-positive spermatids (step 13 in stage I and step 14 in stage II tubules) in Chd5Aam1−/− testis. Scale bar, 20 μm. (d) Western blot analyses of purified spermatids at different spermiogenic stages show a transient up-regulation of γ-H2A.X in wild type ECS, and increased accumulation of γ-H2A.X in Chd5Aam1−/− ECS and CS compared to wild type counterparts. β-Actin serves as a loading control. RS, round spermatids; RES, round and early elongating spermatids; ECS, elongating and condensing spermatids; CS, condensed spermatids.

Chd5 loss alters gene expression in spermatids

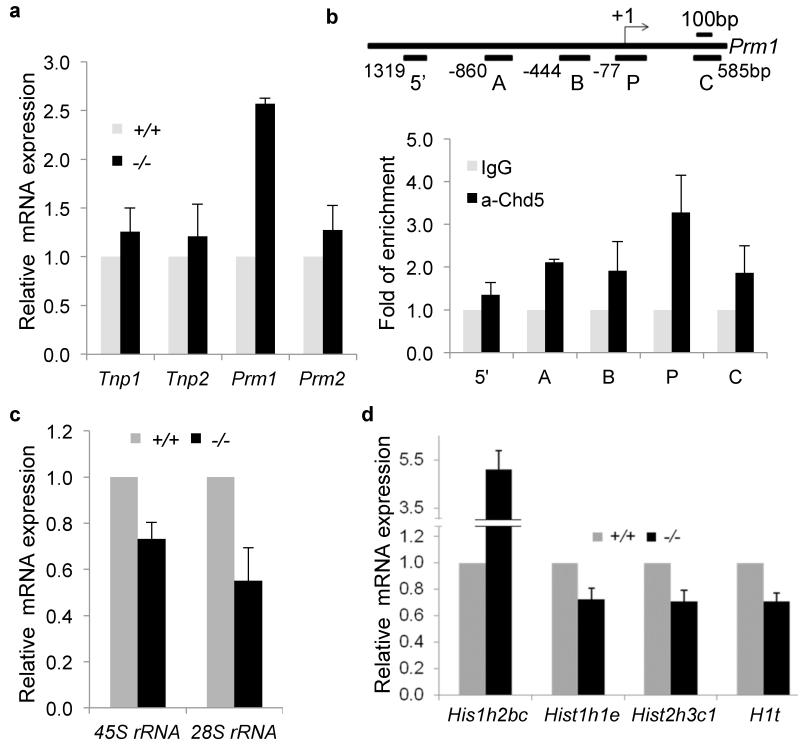

Tnp1, Tnp2, Prm1 and Prm2 are transcribed in round spermatids, but their transcripts are stored in translationally repressed ribonucleoprotein particles (RNPs) before being later translated into protein within elongating spermatids34-36. To determine whether the increase in transition proteins and protamines within Chd5-deficient spermatids was due to enhanced expression at the transcript level, we used qRT-PCR to assess Tnp1, Tnp2, Prm1 and Prm2 expression in Chd5Aam1−/− and Chd5Aam1+/+ round spermatids. Whereas only a slight increase of Tnp1, Tnp2, and Prm2 transcripts were detected, Prm1 transcript was increased approximately 2.5 fold in Chd5Aam1−/− round spermatids (Fig. 7a). Using Chromatin Immunoprecipitation-qPCR (ChIP-qPCR) analyses of nuclear lysates from testicular cells, we found an enrichment of Chd5 binding at the Prm1 promoter (region P: −77 bp to +135 bp)(Fig. 7b). Less pronounced Chd5 binding was observed at region A (−860 to −672bp), B (−444 bp to −239 bp) and C (+397 bp to +585 bp), but not at region 5− (−1319 bp to −1164 bp). Collectively, these data suggest that Chd5 represses Prm1 transcription, whereas it negatively modulates expression of Tnp1, Tnp2, and Prm2 mainly post-transcriptionally.

Figure 7. Altered transcription of Prm1 and histone variants in Chd5-deficient spermatids.

(a) qRT-PCR analyses of transition protein and protamine genes in Chd5Aam1+/+ and Chd5Aam1−/− round spermatids. Results are normalized to Actb expression. Prm1 expression is increased approximately 2.5 fold in Chd5Aam1−/− round spermatids. Data are presented as mean ± s.d. from four independent experiments. (b) Top panel, diagram of mouse Prm1 gene and location of primer sets used for ChIP-qPCR. Bottom panel, ChIP-qPCR analyses reveals enrichment of Chd5 at promoter region P (-77 bp to +135 bp) of Prm1 gene. The results are normalized to IgG control and are shown as fold of enrichment. Data are presented as mean ± s.d. from four to five independent experiments. (c) qRT-PCR analyses of rRNAs shows compromised expression of 28S and 45S ribosomal RNAs in Chd5Aam1−/− (−/−) round spermatids. Results are normalized to Actb expression. Data are presented as mean ± s.d. from four to five independent experiments. (d) qRT-PCR analyses of histone variants revealed an approximately 5 fold increase in expression of histone H2B variant Hist1h2bc and modest decreases in expression of histone variants Hist1h1e, Hist2h3c1 and H1t in Chd5Aam1−/− (−/−) round spermatids. Results are normalized to Actb expression. Data are presented as mean ± s.d. from three to five independent experiments.

As described above, a Chd5-intense focus near the edge of chromocenter in round spermatids showed proximity to the nucleolar marker fibrillarin (see Supplementary Fig. 3b), suggesting that Chd5 may play a role in rRNA biogenesis and translational control. qRT-PCR analyses of 45S and 28S rRNA expression revealed that 45S rRNA was reduced approximately 30%, and 28S rRNA expression was reduced over 50%, in Chd5Aam1−/− round spermatids (Fig. 7c), indicating compromised rRNA biogenesis in Chd5Aam1−/− spermatids. These results suggest a role of Chd5 in rRNA biogenesis during spermiogenesis, which is consistent with the known function of other CHD proteins such as CHD4 and CHD7 in positively regulating rRNA biogenesis37,38.

In addition to H4 hyperacetylation, replacement of canonical core nucleosomal histones with histone variants including those that are testis-specific is another key mechanism facilitating nucleosome destabilization and histone removal during spermatogenesis39-41. We examined expression of a panel of general and testis-specific histone variants in Chd5Aam1+/+ and Chd5Aam1−/− round spermatids via qRT-PCR, and discovered that expression of the H2b variant Hist1h2bc was elevated over 5 fold in Chd5Aam1−/− round spermatids (Fig. 7d). Although little is known about the functions of Hist1h2bc, its substantial increase in Chd5Aam1−/− round spermatids suggests that it might impact histone variant exchanges during spermiogenesis. In addition, an approximate 30% decrease in expression of histone H1 variant Hist1h1e, histone H3 variant Hist2h3c1 and testis-specific H1 variant H1t were consistently observed in Chd5Aam1−/− spermatids (Fig. 7d). These findings indicate that Chd5 deficiency alters transcript levels of specific histone variants during spermiogenesis.

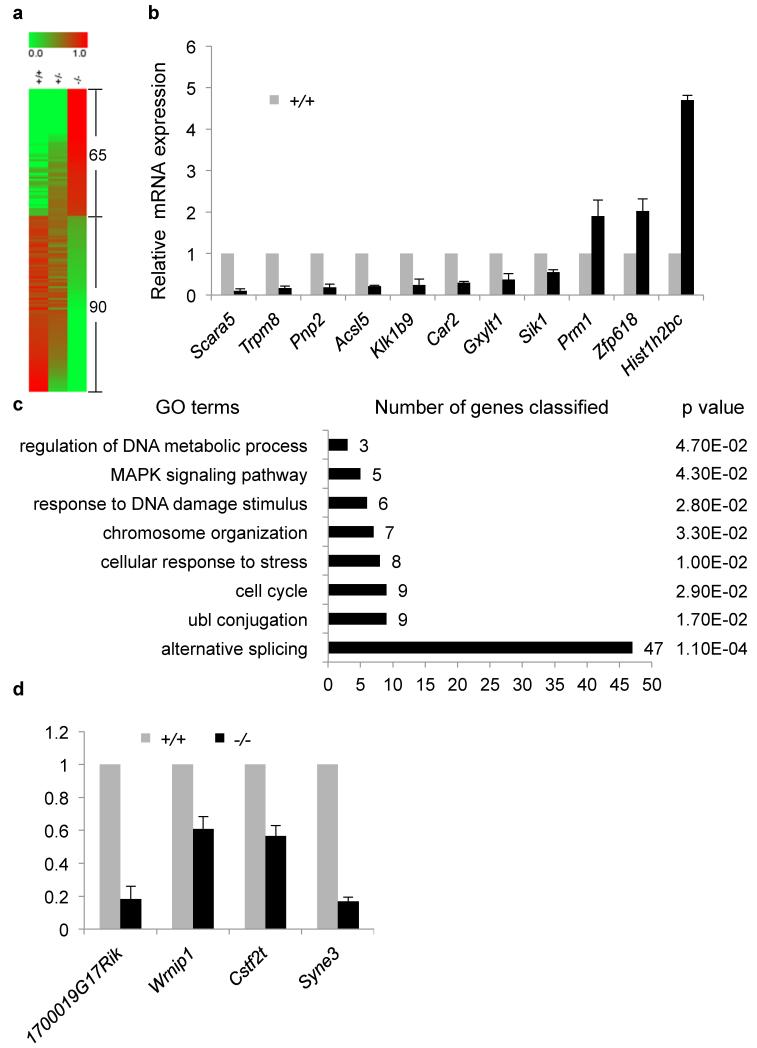

In order to gain insight into the global gene expression changes resulting from Chd5 deficiency and to identify candidate Chd5 targets, we performed RNA Sequencing (RNA-Seq)(Fig. 8). Chd5 is mainly expressed in round spermatids, where transcription is most active during spermiogenesis, with transcription globally being ceased afterwards. Using RNA-Seq, we compared mRNA expression profiles of round spermatids that had been elutriation-purified from 5 sets of Chd5Aam1+/+, Chd5Aam1+/- and Chd5Aam1−/− littermates. Expression of 14,206 transcripts was detected in at least one of the three genotypes. Two-hundred and sixty-one transcripts, or 1.8% of all the transcripts detected, showed a two-fold or greater expression change in Chd5Aam1−/− round spermatids compared to Chd5Aam1+/+ counterparts (false discovery rate q = 0.05). Among the 261 transcripts, 156 transcripts or 59.8% were downregulated, whereas 105 transcripts, or 40.2%, were upregulated, in Chd5Aam1−/− round spermatids. Together, these results suggest that Chd5 deficiency leads to a rather limited alteration in global gene expression in round spermatids, and that Chd5 both activates and suppresses gene expression in round spermatids with a slight preference for activation. Gene ontology analysis of the gene expression changes showed clustering of GO terms including chromosome organization, response to DNA damage, acetylation, alternative splicing, nuclear export, protein transport, ubl (ubiquitin) conjugation, intracellular transport, endocytosis, cell cycle and MAPK pathway (Supplementary Fig. 14). Since Chd5Aam1+/- male mice were fertile, we reasoned that genes that had expression changes only in Chd5Aam1−/− spermatids but not in Chd5Aam1+/- spermatids, or genes that had gradual expression changes dependent on Chd5 dosage, would be candidates most likely to contribute to the infertility of Chd5Aam1−/− male mice. We thus further filtered the 261 transcripts through clustering with manual examination and identified a list of 155 transcripts that had expression changes only in Chd5Aam1−/− spermatids, or that had gradual expression changes which correlated with Chd5 dosage (Fig. 8a, Supplementary Fig. 15). Among the list, 90 transcripts were down regulated and 65 transcripts, including Hist1h2bc, were up regulated in Chd5Aam1−/− spermatids (Fig. 8a). qRT-PCR analyses for expression of 11 genes from this list, which included the positive control Hist1h2bc and represented a range of expression changes, was used to validate the expression changes revealed by RNA-Seq, attesting to the reliability of the RNA-Seq data and analyses (Fig. 8b). Gene ontology analysis of this list showed clustering of a subset of GO terms revealed from the original list, which include chromosome organization, response to DNA damage stimulus, alternative splicing, ubl conjugation, regulation of DNA metabolic process, cell cycle and MAPK signaling (Fig. 8c). A number of candidates implicated in acetylation (1700019G17Rik), DNA damage response (Wrnip1), RNA processing and translational control (Cstf2t) and nuclear structure maintenance (Syne3) were further verified using qRT-PCR (Fig. 8d, Supplementary Fig. 16). Altogether, these GO terms are consistent with the phenotypic impacts of Chd5 deficiency on chromatin compaction, DNA damage response and posttranscriptional modulation of transition proteins and protamines during spermiogenesis. Alterations in gene expression within these GO terms are likely contributing, at least partially, to the spermatogenic abnormalities of Chd5Aam1−/− male mice.

Figure 8. RNA-Seq reveals global gene expression changes in Chd5Aam1−/− spermatids.

(a) Heat map presentation of gene expression in Chd5Aam1+/+, Chd5Aam1+/- and Chd5Aam1−/− round spermatids revealed by RNA-Seq. Green to red (0 to 1) represents the gradient increase of expression levels. Sixty-five transcripts show upregulation, and 90 transcripts show downregulation, in Chd5Aam1−/− round spermatids. (b) qRT-PCR validation of RNA-Seq revealed gene expression changes in round spermatids. Results are normalized to Actb expression and data are presented as mean ± s.d. from four to five independent experiments. (c) Gene ontology analysis of the 155 transcripts that either show expression changes only in Chd5Aam1−/− spermatids but not in Chd5Aam1+/- spermatids, or that show gradual expression change from Chd5Aam1+/+ spermatids to Chd5Aam1+/- spermatids to Chd5Aam1−/− spermatids. Numbers next to bars indicate the number of genes classified to the corresponding GO term. P value is calculated using modified Fisher’s exact test by DAVID (v6.7)70. (d) qRT-PCR verification of compromised expression of genes implicated in histone acetylation, DNA damage response, RNA processing and nuclear integrity in Chd5Aam1−/− spermatids. Results are normalized to Actb expression and Data are presented as mean ± s.d. from four to five independent experiments.

Discussion

In this study, we show that Chd5 mediates a cascade of molecular events underlying histone removal during spermiogenesis including H4 hyperacetylation, histone variant expression, nucleosome eviction, and DNA damage repair. Chd5 deficiency leads to disruption of these biological processes and increases histone retention in both spermatids and sperm. We reveal that Chd5 also modulates the homeostasis of transition proteins and protamines by suppressing expression of Prm1 transcriptionally and expression of Tnp1, Tnp2 and Prm2 post-transcriptionally. Chd5 deficiency results in elevated levels of both transition proteins and protamines. These findings unravel pleiotropic functions of Chd5 and highlight its multi-faceted role in orchestrating the extensive histone-to-protamine remodeling that occurs during male germ cell development.

Chd5 contains multiple domains (PHD domains, chromodomains, SNF2-like ATPase domain, DEAD/DEAH-box Helicase domain, SANT domain and DNA binding motifs), which may enable its diverse functions during spermiogenesis. The SNF2-like ATPase domain defines the nucleosome remodeling function of CHD proteins42,43. Chd5 may facilitate nucleosome eviction during spermiogenesis through its ATPase domain, whose absence in Chd5-deficient spermatids would thus lead to inefficient nucleosome eviction. The ATPase domain is also implicated in DNA damage repair in somatic cells44 and may play a direct role in the DNA damage response during spermiogenesis and contribute to the increased DNA damage in Chd5-deficient spermatids. The DEAD/DEAH-box helicase domain may implicate Chd5 in RNA processing and the characteristic repression of mRNA translation in round spermatids, which could contribute to the abnormal post-transcriptional elevation of transition proteins and protamines in Chd5-deficient spermatids. It is known that the dual PHD domains of Chd5 preferentially bind H3 tails lacking H3K4me3 in mouse embryonic fibroblasts10, whereas the chromodomains bind to H3K27me3 in neurons, both of which are important for Chd5 to mediate gene expression in somatic cells10,45. We also observe such patterns in mouse spermatids, as Chd5 is enriched in the chromocenter of spermatids, a heterochromatic region marked with H3K9me3 and H3K27me3, but lacking H3K4me3 (Fig.1, Supplementary Fig. 2). This suggests that the PHD and/or chromodomains of Chd5 may also play important roles in regulating gene expression in spermatids, as RNA-Seq revealed that Chd5 deficiency leads to expression changes of specific gene sets. These multiple functional domains of Chd5 may work independently or in concert, enabling the diverse functions of Chd5 observed during spermiogenesis.

It is possible that there is a functional connection between the histone removal process and homeostasis of transition proteins and protamines. For example, transition proteins have been implicated in DNA repair during spermiogenesis46,47, thus the abnormal levels of transition proteins may contribute to the increased DNA damage in Chd5Aam1−/− spermatids. On the other hand, deficient H4 acetylation may alter the chromatin structure of the Prm1 locus, thereby contributing to its increased transcription, although it is counterintuitive that a decrease in H4 acetylation would result in transcriptional activation.

Chromatin remodelers are thought to be critical for the extensive chromatin remodeling taking place during the post-meiotic phase of spermiogenesis, however little is known about their roles in this process. The chromatin remodeler Brg1 is essential for meiosis, and its deficiency leads to meiotic arrest with global alterations in histone modifications and chromatin structure in mice48. Acf1, which binds to chromatin remodeler Snf2h within the ACF complex, plays an essential role during post-meiotic spermiogenesis49. Deletion of Acf1 results in male infertility with increased DNA damage and spermiation defects, but without any detectable alterations in chromatin composition49. Previous studies have also suggested roles of chromatin modifier Rnf8, a E3 ubiquitin ligase, in spermiogenesis. Lu et al. revealed that Rnf8 mediates H2A and H2B ubiquitination in elongating spermatids, and is critical for H4K16 acetylation and histone-to-protamine replacement50. However, Sin et al. later reported that Rnf8 deficiency does not affect H4K16 acetylation and histone-to-protamine exchange in spermatids, but instead compromises gene activation from inactive sex chromosomes in round spermatids51. Thus, while a number of nuclear proteins have been implicated in spermatogenesis, Chd5, to our knowledge, is the first chromatin remodeler identified to play an orchestrating role in chromatin remodeling during post-meiotic spermiogenesis.

Consistent with Chd5 deficiency disrupting histone acetylation, DNA damage response and homeostasis of transition proteins and protamines during spermiogenesis, RNA-Seq reveals that Chd5 deficiency alters expression of genes encoding proteins underlying these processes, but does not cause a major change in global gene expression in round spermatids. We validate a number of candidate Chd5 target genes (e.g. Cstf2t, 1700019G17Rik, Wrnip1 and Syne3) implicated in these processes. Notably, Cstf2t encodes the RNA polyadenylation protein tauCstF-64, which is expressed during haploid spermatid differentiation52. Deletion of Cstf2t in mice disrupts post-meiotic development and leads to male infertility52. Similar to the heterogeneity of histopathology among Chd5Aam1−/− testes, Cstf2t−/− male mice also display variable expressivity of sperm defects52. These intriguing parallels suggest that deficient expression of Cstf2t in Chd5Aam1−/− spermatids may contribute to the infertile phenotypes of Chd5Aam1−/− mice. In addition, the compromised expression of Cstf2t in Chd5Aam1−/− spermatids may compromise polyadenylation and translational repression of transition protein and protamine mRNAs thereby leading to an elevation in protein production, since translational repression of mRNAs in spermatids involves binding of protein repressors to poly (A) tails, and shortening of poly (A) tails of Tnp1, Tnp2, Prm1 and Prm2 mRNAs accompanies their translation activation53,54. 1700019G17Rik encodes a putative N-acetyltransferase that is highly enriched in mouse testis but is absent in most other tissues (Supplementary Fig. 15a). We also found that 1700019G17Rik expression increases as round spermatids differentiate into elongating spermatids, the time point at which H4 hyperacetylation occurs (Supplementary Fig. 15b). These data suggest 1700019G17Rik as a potential acetyltransferase affecting H4 acetylation during spermiogenesis, and the greater than 80% decrease in expression may compromise H4 acetylation in Chd5Aam1−/− spermatids. Wrnip1 stimulates the activity of DNA polymerase delta, rapidly accumulates at laser-irradiated sites, and is required for maintaining genome integrity55-57. Syne3 is a component of the nuclear envelope that tethers the nucleus to the cytoskeleton, and is critical for maintaining nuclear organization and structural integrity, as well as for development of the sperm head58-62. Compromised expression of Wrnip1 and Syne3 may contribute to the enhanced DNA damage and abnormal sperm head morphology, respectively, in Chd5Aam1−/− testis. However, it is not yet clear whether these genes and other candidates revealed by RNA-Seq are direct Chd5 target genes, a question that could be addressed by defining the global pattern of Chd5-bound loci in spermatids. A small proportion of histones and nucleosomes are retained in chromatin of wild type sperm, preferentially at loci encoding proteins of developmental importance63. It would be interesting to know whether the aberrant histone retention in Chd5Aam1−/− sperm disrupts such a pattern, where the aberrantly retained histones locate in the genome of Chd5Aam1−/− sperm, and to understand these implications for the developmental potency of the sperm. Future studies to characterize genome-wide distribution of Chd5, nucleosomal histones and specific histone modifications in Chd5-deficient spermatids and sperm should shed additional light on these questions.

We observed variation ranging from sterility to subfertility among individual Chd5Aam1−/− male mice in a mixed C57BL/6 and 129S background, as well as among individual Chd5Tm1b−/− male mice in a pure C57BL/6 background. Such variability in infertility is similarly observed in Tnp1−/− and Tnp2−/− male mice, as approximately 40% and 89% of Tnp1−/− and Tnp2−/− male mice, respectively, are sub-fertile23,24. The aberrant Tnp1 and Tnp2 levels in Chd5-deficient testes may contribute to the variable infertility among individual Chd5-deficient male mice. In addition, we observed increased DNA damage in Chd5-deficient spermatids and sperm. The intrinsically variable extent of DNA damage may be more severe in testes of some Chd5-deficient mice than in others, thus contributing to the variability of infertility.

H4 hyperacetylation in early elongating spermatids is shown to be essential for histone-to-protamine replacement in Drosophila 25 and has been considered the same for mammalian spermiogenesis6,25,26. Our study shows that Chd5 deficiency leads to substantial deficiency in H4 acetylation in elongating spermatids and subsequent defects in nucleosome eviction and histone removal, supporting the notion that H4 hyperacetylation is indeed critical for efficient nucleosome eviction and histone removal during mouse spermiogenesis. However, most nucleosomes and histones eventually get removed in late Chd5Aam1−/− spermatids. This suggests that whereas H4 hyperacetylation is important for efficient nucleosome eviction and histone removal during mammalian spermiogenesis, it seems not essential. Thus, whether H4 hyperacetylation is required for histone-to-protamine replacement during mammalian spermiogenesis warrants further investigation. In addition, the enzymes responsible for H4 hyperacetylation during spermiogenesis remain unidentified and are of great interest in the field. Our study identifies 1700019G17Rik as a candidate acetyltransferase for H4 hyperacetylation, providing a new promising target for future study.

The cascade of defects in H4 hyperacetylation, nucleosome eviction, and DNA break repair during Chd5Aam1−/− spermatid maturation provide functional evidence demonstrating the sequential order of these events, and suggest a model for the molecular events underlying the histone-to-protamine replacement process during spermiogenesis: H4 is first hyperacetylated, which along with other epigenetic modifications, leads to chromatin loosening and nucleosome eviction to facilitate histone removal and exposure of the DNA to allow for deposition of transition proteins and eventually protamines. DSBs are generated during nucleosome eviction to resolve supercoiling tension and DNA damage response is activated to repair the DSBs, ensuring integrity of the sperm genome. This sequence of molecular events is in agreement with the model proposed by Leduc et al.30. Our findings establish functional evidence revealing the cascade of major molecular events underlying the histone-to-protamine replacement process, and provide a foundation to further elucidate this critical but elusive process.

Methods

Generation of Chd5 deficient mouse models

To generate the Chd5Aam1 mouse model, Chd5 locus was disrupted in AB2.2 ES cells using the MHPN20h05 MICER vector64, and targeted ES cells were injected into C57BL/6 blastocysts through standard procedures. All animals were housed and utilized according to the Cold Spring Harbor Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) and the Association for Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care International (AAALAC) policies. Progeny resulting from germline transmission were backcrossed to wild type C57BL/6 mice, and Chd5Aam1+/- mice were intercrossed to obtain homozygotes. To generate the Chd5Tm1b mouse model, ES clones with Chd5Tm1a(EUCOMM)Wtsi allele, which has exon 2 of Chd5 locus flanked by LoxP sites, were obtained from EUCOMM (European Conditional Mouse Mutagenesis)65. ES cells were from the C57BL/6N-A/a background and were injected into albino B6 (C57BL/6J-Tyr c-2J) blastocysts through standard procedures. Progeny resulting from germline transmission, designated as Chd5Tm1a+/- mice harbored a Chd5 allele with exon 2 flanked by LoxP sites. Chd5Tm1a+/- mice were mated to CMV-Cre mice in the C57BL/6 background to obtain Chd5Tm1b+/- mice (which had a Chd5 allele with exon 2 excised), and Chd5Tm1b+/- mice were intercrossed to obtain Chd5Tm1b−/− progeny.

Genotyping

For Southern blot genotyping of the Chd5Aam1 model, the MHPN20h05 MICER vector was cut with Afl II and the 2.6 kb excised fragment was gel purified and used as a probe. Southern blotting of genomic DNA digested with Bgl II yielded the expected 7.8 and 10.4 kb endogenous and targeted alleles, respectively. Genotypes were differentiated based on dosage of the targeted allele (Chd5Aam1+/+, 0 copies; Chd5Aam1+/-, 1 copy; Chd5Aam1−/−, 2 copies). All genotypes had 2 copies of the endogenous band, which serve as an internal loading control and reference for dosage. For PCR-based genotyping, relative dosage of the neo-cassette in different genotypes (Chd5Aam1+/+, 0 copies; Chd5Aam1+/-, 1 copy; Chd5Aam1−/−, 2 copies) was quantitated using qPCR, with Neo-cassette dosage being normalized to dosage of Actb. Genotyping of Chd5Tm1b mice was performed by PCR using primers (Supplementary Fig. 16) that amplify a 674 bp endogenous band specific for the wild type Chd5 allele and a 456 bp targeted band specific for the targeted Chd5Tm1b allele.

Antibodies

Antibodies used for Western blot, immunoflurorescence, and ChIP are as follows: anti-H3K27me3 (Cell Signaling #9756, 1:100 for IF, i.e. immunofluorescence), anti-H2A (Cell Signaling #2578, 1:300 for WB, i.e. Western blotting), anti-H4 (Cell Signaling #2935, 1:800 for WB), anti-γ-H2A.X (Cell signaling #9718, 1:200 for IF; 1:1500 for WB), anti-H3K9me3 (Active Motif #39385, 1:100 for IF), anti-H1 (Active Motif #39707, 1:800 for WB), anti-H2B (Active Motif #39125, 1:800 for WB), anti-H4Ac-pan (Active Motif #39243, 1:1000 for WB; 1:200 for IF), anti-H3 (Abcam #ab1791, 1:15000 for WB), anti-Chd5 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology #sc-68389, 1:1500 for WB; 1:200 for IF), anti β-Actin (Sigma #A2228, 1:2000 for WB), anti-H4K5/8/12/14Ac (Millipore #05-1335, 1:100 for IF), anti-lectin PNA Alex Fluor 568 (Invitrogen #L32458, 1:4000 for IF), anti-Prm1 (Briar Patch Biosciences, Hup1N, 1:300 for WB; 1:150 for IF), antiPrm2 (Briar Patch Biosciences, Hup2B, 1:800 for WB; 1: 200 for IF), anti-Tnp1 (gift from Dr. Stephen Kistler, University of South Carolina, 1:500 for WB; 1: 100 for IF), anti-Tnp2 (gift from Dr. Stephen Kistler, University of South Carolina, 1:1000 for WB; 1: 200 for IF) anti-nucleosome (mab #32, gift from Dr. Jo H.M. Berden, Radboud University Nijmegen Medical Center, 1:300 for IF).

Histology and immunostaining

Testes were fixed in Bouin’s fixative or 4% paraformaldehyde, embedded in paraffin, and sectioned at 5 μm. Sections were deparaffinized in xylene and subjected to either PAS staining for histological analyses or immunofluorescent staining using the indicated antibodies.

Sperm counts and motility analysis

Individual caudal epididymi were minced in 200 μl HTF medium (Irvine Scientific). After 30 minutes incubation at 37 °C, the tissue pieces were separated from sperm by pipetting and passaging through a 70 μm filter. Sperm counts and motility assessment were performed using the DRM-600 CELL-VU Sperm Counting Cytometer.

Sperm morphology

Air-dried smears were prepared from sperm suspended in PBS, stained with hematoxylin, and examined using light microscopy at 100 × magnification. Head, neck, and tail morphology was determined independently for each mouse, with separate counts of at least 100 cells per sample.

Sperm chromatin structure assay

SCSA was carried out as previously described24 using a LSR II flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson). Briefly, a 0.2 ml aliquot of sperm nuclei in TNE buffer (0.1 M Tris, 0.15 M NaCl, and 1 mM EDTA, pH 7.4) was mixed with 0.4 ml acid detergent solution (0.15 M NaCl, 0.08 N HCl, and 0.1% Triton X-100, pH 1.4). After 30 seconds, 1.2 ml acridine orange staining solution (6 μg/ml acridine orange, 0.1 M citric acid, 0.2 M Na2HPO4, 1 mM EDTA, and 0.15 M NaCl, pH 6.0) were added to the denatured sperm nuclei. After staining for 3 minutes, samples were measured for green and red fluorescence using LSR II with a 488-nm excitation wavelength. For the SCSA assay, acid-treated sperm were stained with acridine orange, which emits red or green fluorescence when binding to single-stranded or double-stranded DNA, respectively. Sperm with impaired chromatin generate more single-stranded DNA after denaturation with acid treatment, and therefore emit more red fluorescence. DNA Fragmentation Index (DFI) is defined as the percentage of red/green + red fluorescence.

Transmission Electron Microscopy

Testes were fixed with 2% paraformaldehyde and 2% glutaraldehyde in 0.1 M sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.4), dehydrated, and embedded in Epon. Sections were contrasted and imaged in a Hitachi H7000T transmission electron microscope.

Basic protein extraction and acid-urea gel electrophoresis

Testes were surgically decapsulated and homogenized in buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.2, 0.32 M sucrose, 5 mM MgCl2, 0.1% Triton-X100, 0.5 mM PMSF). After centrifugation, cell pellets were resuspended in sonication buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 25 mM 2-mercaptoethanol) and sonicated using a Diagenode Bioruptor UCD-200 to obtain sonication resistant spermatids (SRS), which represent step 12 to 16 spermatids. After centrifugation, SRS pellets were resuspended in 10 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5 by brief vortexing and HCl was added to a final concentration of 0.5 M. Samples were incubated on ice for 30 minutes to extract basic proteins. After centrifugation, the supernatant was transferred to a new tube and 20% trichloroacetic acid (final concentration) was added to precipitate basic proteins. Protein pellets were washed with acetone, dried, and dissolved in buffer containing 5 M urea, 0.5% acetic acid and 1% β-2-mercaptoethanol. Proteins were separated by electrophoresis in acid-urea-15% polyacrylamide gels and were subjected to either staining with Coomassie brilliant blue or Western blot using the indicated antibodies.

TUNEL assay

TUNEL assays were performed with the In Situ Cell Death Detection Fluorescein Kit (Roche), following the manufacturer’s instruction. Briefly, testes sections were deparaffinized, rehydrated, and digested with 20 μg/ml Proteinase K in 10 mM Tris pH 7.5 for 30 minutes at 37 °C. After washes, sections were incubated with TUNEL reaction mixture for 1 hour at 37 °C, followed with lectin PNA (1:4000, 1 hr) and DAPI (1:5000, 5 minutes) staining to visualize acrosomes and DNA.

ChIP

ChIP was performed using SimpleChIP Enzymatic Chromatin IP Kit (Cell Signaling) with the indicated antibodies. Primers for ChIP-qPCR are listed in Supplementary Table 5.

Centrifugal elutriation

Fractionation of spermatogenic cells through centrifugal elutriation was performed as previously described66 using a Beckman Coulter Avanti J-26XP centrifuge with JE-5.0 rotor.

RNA-Seq

Five sets of Chd5Aam1+/+: Chd5Aam1+/-: Chd5Aam1−/− littermate male mice with matched background and age (~3 months old) were used for elutriation. Round spermatids were purified through centrifugal elutriation of the testes pooled from five mice of the same genotype. Total RNA was prepared from the round spermatid samples using RNeasy kit (Qiagen) with DNase I treatment. RNA-Seq libraries were prepared from RNA samples using Illumina TruSeq protocol. RNA-Seq libraries were barcoded and sequenced on Illumina HiSeq 2000. Data are deposited in the Short Reads Archive (accession number SRPO40711).

RNA-Seq data analysis

The quality of raw data was assessed and passed by FastQC. Reads were mapped to the mm9 reference genome with OLego67. Cufflinks (v2.0.2)68 was used to estimate transcript expression levels represented by FPKM (fragments per kilo bases per million mapped reads) for all the samples. Ensembl transcripts annotation was provided (-g) to guide transcriptome reconstruction. Cuffdiff 68 was run to detect differential expression between samples. Transcripts showing two-fold or more expression changes in Chd5Aam1−/− spermatids compared to Chd5Aam1+/+ spermatids were selected (false discovery rate q=0.05), and further filtered via hierarchical clustering using Genesis (v1.7.6)69. Clusters that either showed expression changes only in Chd5Aam1−/− spermatids but not in Chd5Aam1+/- spermatids, or those that showed gradual expression changes from Chd5Aam1+/+ spermatids toChd5Aam1+/-spermatids to Chd5Aam1−/− spermatids, were selected for gene ontology analysis using DAVID (v6.7)70.

qRT-PCR validation of RNA-Seq hits

qRT-PCR was first performed on the same RNA samples used for RNA-Seq, and then repeated using another set of RNA samples which were prepared from round spermatids that had been elutriation-purified from three different sets of Chd5Aam1+/+, Chd5Aam1+/-, and Chd5Aam1−/− littermate male mice with matched background and age. All qRT-PCR results were pooled and data are presented as mean ± s.d. from four to five independent experiments. Primers for qRT-PCR and ChIP-qPCR are listed in Supplementary Table 5.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank W. Stephen Kistler for anti-Tnp antibodies, Jo H.M. Berden for anti-nucleosome antibodies, Emma Vernersson-Lindahl for critical reading of the manuscript, and Lisa Bianco and Aigoul Nourjanova for technical assistance. This project was supported by the Office of the Director, National Institutes of Health under award numbers R01CA127383 (to A.A.M) and R21OD018332 (to A.A.M), NIH HG001696 (to M.Q.Z), and NSFC 91019016 (to M.Q.Z); the content is the sole responsibility of the authors. This work was performed with assistance from Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Shared Resources, which are funded, in part, by the Cancer Center Support Grant 5P30CA045508.

Footnotes

Author Contributions W.L. and A.A.M. designed experiments and prepared the manuscript with input from co-authors. W.L. and A.A.M. generated Chd5 deficient mouse models. W.L. performed experiments with assistance from S.Y.K. for sperm analyses and IVF, and with assistance from M.Z. and M.L.M. for centrifugal elutriation. W.L. and A.A.M. interpreted the data, with RNA-Seq data being analyzed by J.W., W.L. and M.Q.Z.

Competing Financial Interests statement The authors declare no conflict of financial interests.

References

- 1.Hess RA, Renato de Franca L. Spermatogenesis and cycle of the seminiferous epithelium. Advances in experimental medicine and biology. 2008;636:1–15. doi: 10.1007/978-0-387-09597-4_1. doi:10.1007/978-0-387-09597-4_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tanaka H, Baba T. Gene expression in spermiogenesis. Cellular and molecular life sciences: CMLS. 2005;62:344–354. doi: 10.1007/s00018-004-4394-y. doi:10.1007/s00018-004-4394-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Oakberg EF. Duration of spermatogenesis in the mouse and timing of stages of the cycle of the seminiferous epithelium. The American journal of anatomy. 1956;99:507–516. doi: 10.1002/aja.1000990307. doi:10.1002/aja.1000990307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Oakberg EF. A description of spermiogenesis in the mouse and its use in analysis of the cycle of the seminiferous epithelium and germ cell renewal. The American journal of anatomy. 1956;99:391–413. doi: 10.1002/aja.1000990303. doi:10.1002/aja.1000990303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ahmed EA, de Rooij DG. Staging of mouse seminiferous tubule cross-sections. Methods in molecular biology. 2009;558:263–277. doi: 10.1007/978-1-60761-103-5_16. doi:10.1007/978-1-60761-103-5_16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rousseaux S, et al. Epigenetic reprogramming of the male genome during gametogenesis and in the zygote. Reproductive biomedicine online. 2008;16:492–503. doi: 10.1016/s1472-6483(10)60456-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hud NV, Allen MJ, Downing KH, Lee J, Balhorn R. Identification of the elemental packing unit of DNA in mammalian sperm cells by atomic force microscopy. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1993;193:1347–1354. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1993.1773. doi:S0006-291X(83)71773-0 [pii]10.1006/bbrc.1993.1773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ward WS, Coffey DS. DNA packaging and organization in mammalian spermatozoa: comparison with somatic cells. Biology of reproduction. 1991;44:569–574. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod44.4.569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bagchi A, et al. CHD5 is a tumor suppressor at human 1p36. Cell. 2007;128:459–475. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.11.052. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2006.11.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Paul S, et al. Chd5 requires PHD-mediated histone 3 binding for tumor suppression. Cell reports. 2013;3:92–102. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2012.12.009. doi:10.1016/j.celrep.2012.12.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Oliver SS, et al. Multivalent recognition of histone tails by the PHD fingers of CHD5. Biochemistry. 2012;51:6534–6544. doi: 10.1021/bi3006972. doi:10.1021/bi3006972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vestin A, Mills AA. The tumor suppressor Chd5 is induced during neuronal differentiation in the developing mouse brain. Gene expression patterns: GEP. 2013;13:482–489. doi: 10.1016/j.gep.2013.09.003. doi:10.1016/j.gep.2013.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Berkovits BD, Wolgemuth DJ. The role of the double bromodomain-containing BET genes during mammalian spermatogenesis. Current topics in developmental biology. 2013;102:293–326. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-416024-8.00011-8. doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-416024-8.00011-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cocquet J, et al. A genetic basis for a postmeiotic X versus Y chromosome intragenomic conflict in the mouse. PLoS genetics. 2012;8:e1002900. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002900. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1002900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Skarnes WC, et al. A conditional knockout resource for the genome-wide study of mouse gene function. Nature. 2011;474:337–342. doi: 10.1038/nature10163. doi:10.1038/nature10163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhuang T, et al. CHD5 is required for spermiogenesis and chromatin condensation. Mechanisms of development. 2014;131:35–46. doi: 10.1016/j.mod.2013.10.005. doi:10.1016/j.mod.2013.10.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bungum M. Sperm DNA integrity assessment: a new tool in diagnosis and treatment of fertility. Obstet Gynecol Int. 2012;2012:531042. doi: 10.1155/2012/531042. doi:10.1155/2012/531042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Spiess AN, et al. Cross-platform gene expression signature of human spermatogenic failure reveals inflammatory-like response. Human reproduction. 2007;22:2936–2946. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dem292. doi:10.1093/humrep/dem292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kimmins S, Sassone-Corsi P. Chromatin remodelling and epigenetic features of germ cells. Nature. 2005;434:583–589. doi: 10.1038/nature03368. doi:nature03368 [pii]10.1038/nature03368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Carrell DT. Epigenetics of the male gamete. Fertility and sterility. 2012;97:267–274. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2011.12.036. doi:10.1016/j.fertnstert.2011.12.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Carrell DT, Emery BR, Hammoud S. Altered protamine expression and diminished spermatogenesis: what is the link? Human reproduction update. 2007;13:313–327. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dml057. doi:10.1093/humupd/dml057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Okada Y, Scott G, Ray MK, Mishina Y, Zhang Y. Histone demethylase JHDM2A is critical for Tnp1 and Prm1 transcription and spermatogenesis. Nature. 2007;450:119–123. doi: 10.1038/nature06236. doi:10.1038/nature06236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yu YE, et al. Abnormal spermatogenesis and reduced fertility in transition nuclear protein 1-deficient mice. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2000;97:4683–4688. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.9.4683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhao M, et al. Targeted disruption of the transition protein 2 gene affects sperm chromatin structure and reduces fertility in mice. Molecular and cellular biology. 2001;21:7243–7255. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.21.7243-7255.2001. doi:10.1128/MCB.21.21.7243-7255.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Awe S, Renkawitz-Pohl R. Histone H4 acetylation is essential to proceed from a histone- to a protamine-based chromatin structure in spermatid nuclei of Drosophila melanogaster. Systems biology in reproductive medicine. 2010;56:44–61. doi: 10.3109/19396360903490790. doi:10.3109/19396360903490790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sonnack V, Failing K, Bergmann M, Steger K. Expression of hyperacetylated histone H4 during normal and impaired human spermatogenesis. Andrologia. 2002;34:384–390. doi: 10.1046/j.1439-0272.2002.00524.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gaucher J, et al. Bromodomain-dependent stage-specific male genome programming by Brdt. The EMBO journal. 2012;31:3809–3820. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2012.233. doi:10.1038/emboj.2012.233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pivot-Pajot C, et al. Acetylation-dependent chromatin reorganization by BRDT, a testis-specific bromodomain-containing protein. Molecular and cellular biology. 2003;23:5354–5365. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.15.5354-5365.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kramers K, et al. Specificity of monoclonal anti-nucleosome auto-antibodies derived from lupus mice. J Autoimmun. 1996;9:723–729. doi: 10.1006/jaut.1996.0094. doi:S0896-8411(96)90094-3 [pii]10.1006/jaut.1996.0094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Leduc F, Maquennehan V, Nkoma GB, Boissonneault G. DNA damage response during chromatin remodeling in elongating spermatids of mice. Biol Reprod. 2008;78:324–332. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.107.064162. doi:biolreprod.107.064162 [pii]10.1095/biolreprod.107.064162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Marcon L, Boissonneault G. Transient DNA strand breaks during mouse and human spermiogenesis new insights in stage specificity and link to chromatin remodeling. Biol Reprod. 2004;70:910–918. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.103.022541. doi:10.1095/biolreprod.103.022541biolreprod.103.022541 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sakkas D, et al. Origin of DNA damage in ejaculated human spermatozoa. Rev Reprod. 1999;4:31–37. doi: 10.1530/ror.0.0040031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Laberge RM, Boissonneault G. On the nature and origin of DNA strand breaks in elongating spermatids. Biol Reprod. 2005;73:289–296. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.104.036939. doi:biolreprod.104.036939 [pii]10.1095/biolreprod.104.036939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Steger K, et al. Expression of mRNA and protein of nucleoproteins during human spermiogenesis. Mol Hum Reprod. 1998;4:939–945. doi: 10.1093/molehr/4.10.939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Morales CR, Kwon YK, Hecht NB. Cytoplasmic localization during storage and translation of the mRNAs of transition protein 1 and protamine 1, two translationally regulated transcripts of the mammalian testis. J Cell Sci. 1991;100(Pt 1):119–131. doi: 10.1242/jcs.100.1.119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kleene KC. Patterns of translational regulation in the mammalian testis. Molecular reproduction and development. 1996;43:268–281. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-2795(199602)43:2<268::AID-MRD17>3.0.CO;2-#. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1098-2795(199602)43:2<268::AID-MRD17>3.0.CO;2-#. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ling T, et al. CHD4/NuRD maintains demethylation state of rDNA promoters through inhibiting the expression of the rDNA methyltransferase recruiter TIP5. Biochemical and biophysical research communications. 2013 doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2013.06.045. doi:10.1016/j.bbrc.2013.06.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zentner GE, et al. CHD7 functions in the nucleolus as a positive regulator of ribosomal RNA biogenesis. Human molecular genetics. 2010;19:3491–3501. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddq265. doi:10.1093/hmg/ddq265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bonisch C, et al. H2A.Z.2.2 is an alternatively spliced histone H2A.Z variant that causes severe nucleosome destabilization. Nucleic acids research. 2012;40:5951–5964. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks267. doi:10.1093/nar/gks267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tachiwana H, et al. Structural basis of instability of the nucleosome containing a testis-specific histone variant, human H3T. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2010;107:10454–10459. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1003064107. doi:10.1073/pnas.1003064107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Govin J, Caron C, Lestrat C, Rousseaux S, Khochbin S. The role of histones in chromatin remodelling during mammalian spermiogenesis. European journal of biochemistry/FEBS. 2004;271:3459–3469. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.2004.04266.x. doi:10.1111/j.1432-1033.2004.04266.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Marfella CG, Imbalzano AN. The Chd family of chromatin remodelers. Mutation research. 2007;618:30–40. doi: 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2006.07.012. doi:10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2006.07.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hall JA, Georgel PT. CHD proteins: a diverse family with strong ties. Biochemistry and cell biology = Biochimie et biologie cellulaire. 2007;85:463–476. doi: 10.1139/O07-063. doi:10.1139/O07-063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Stanley FK, Moore S, Goodarzi AA. CHD chromatin remodelling enzymes and the DNA damage response. Mutation research. 2013;750:31–44. doi: 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2013.07.008. doi:10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2013.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chris M, Egan UN, Julie Skotte, Gundula Streubel, Siobhán Turner, O’Connell David J., Vilma Rraklli, Dolan Michael J., Naomi Chadderton, Klaus Hansen, Farrar Gwyneth Jane, Kristian Helin, email Johan Holmbergsend, Adrian P. Bracken. CHD5 Is Required for Neurogenesis and Has a Dual Role in Facilitating Gene Expression and Polycomb Gene Repression. Developmental Cell. 2013;26:223–236. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2013.07.008. doi:10.1016/j.devcel.2013.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Boissonneault G. Chromatin remodeling during spermiogenesis: a possible role for the transition proteins in DNA strand break repair. FEBS letters. 2002;514:111–114. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(02)02380-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kierszenbaum AL. Transition nuclear proteins during spermiogenesis: unrepaired DNA breaks not allowed. Molecular reproduction and development. 2001;58:357–358. doi: 10.1002/1098-2795(20010401)58:4<357::AID-MRD1>3.0.CO;2-T. doi:10.1002/1098-2795(20010401)58:4<357::AID-MRD1>3.0.CO;2-T. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kim Y, Fedoriw AM, Magnuson T. An essential role for a mammalian SWI/SNF chromatin-remodeling complex during male meiosis. Development. 2012;139:1133–1140. doi: 10.1242/dev.073478. doi:10.1242/dev.073478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Dowdle JA, et al. Mouse BAZ1A (ACF1) is dispensable for double-strand break repair but is essential for averting improper gene expression during spermatogenesis. PLoS genetics. 2013;9:e1003945. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003945. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1003945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lu LY, et al. RNF8-dependent histone modifications regulate nucleosome removal during spermatogenesis. Dev Cell. 2010;18:371–384. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2010.01.010. doi:10.1016/j.devcel.2010.01.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sin HS, et al. RNF8 regulates active epigenetic modifications and escape gene activation from inactive sex chromosomes in post-meiotic spermatids. Genes & development. 2012;26:2737–2748. doi: 10.1101/gad.202713.112. doi:10.1101/gad.202713.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Dass B, et al. Loss of polyadenylation protein tauCstF-64 causes spermatogenic defects and male infertility. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2007;104:20374–20379. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0707589104. doi:10.1073/pnas.0707589104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Steger K. Haploid spermatids exhibit translationally repressed mRNAs. Anatomy and embryology. 2001;203:323–334. doi: 10.1007/s004290100176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kleene KC. Poly(A) shortening accompanies the activation of translation of five mRNAs during spermiogenesis in the mouse. Development. 1989;106:367–373. doi: 10.1242/dev.106.2.367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Nomura H, et al. WRNIP1 accumulates at laser light irradiated sites rapidly via its ubiquitin-binding zinc finger domain and independently from its ATPase domain. Biochemical and biophysical research communications. 2012;417:1145–1150. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2011.12.080. doi:10.1016/j.bbrc.2011.12.080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hayashi T, et al. Vertebrate WRNIP1 and BLM are required for efficient maintenance of genome stability. Genes & genetic systems. 2008;83:95–100. doi: 10.1266/ggs.83.95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Tsurimoto T, Shinozaki A, Yano M, Seki M, Enomoto T. Human Werner helicase interacting protein 1 (WRNIP1) functions as a novel modulator for DNA polymerase delta. Genes to cells: devoted to molecular & cellular mechanisms. 2005;10:13–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2443.2004.00812.x. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2443.2004.00812.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Morimoto A, et al. A conserved KASH domain protein associates with telomeres, SUN1, and dynactin during mammalian meiosis. The Journal of cell biology. 2012;198:165–172. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201204085. doi:10.1083/jcb.201204085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Gob E, Schmitt J, Benavente R, Alsheimer M. Mammalian sperm head formation involves different polarization of two novel LINC complexes. PloS one. 2010;5:e12072. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0012072. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0012072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Nery FC, et al. TorsinA binds the KASH domain of nesprins and participates in linkage between nuclear envelope and cytoskeleton. Journal of cell science. 2008;121:3476–3486. doi: 10.1242/jcs.029454. doi:10.1242/jcs.029454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ketema M, et al. Requirements for the localization of nesprin-3 at the nuclear envelope and its interaction with plectin. Journal of cell science. 2007;120:3384–3394. doi: 10.1242/jcs.014191. doi:10.1242/jcs.014191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wilhelmsen K, et al. Nesprin-3, a novel outer nuclear membrane protein, associates with the cytoskeletal linker protein plectin. The Journal of cell biology. 2005;171:799–810. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200506083. doi:10.1083/jcb.200506083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Hammoud SS, et al. Distinctive chromatin in human sperm packages genes for embryo development. Nature. 2009;460:473–478. doi: 10.1038/nature08162. doi:10.1038/nature08162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Adams DJ, et al. Mutagenic insertion and chromosome engineering resource (MICER) Nature genetics. 2004;36:867–871. doi: 10.1038/ng1388. doi:10.1038/ng1388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Pettitt SJ, et al. Agouti C57BL/6N embryonic stem cells for mouse genetic resources. Nature methods. 2009;6:493–495. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1342. doi:10.1038/nmeth.1342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Zhao M, et al. Utp14b: a unique retrogene within a gene that has acquired multiple promoters and a specific function in spermatogenesis. Dev Biol. 2007;304:848–859. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2007.01.005. doi:S0012-1606(07)00019-X [pii]10.1016/j.ydbio.2007.01.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Wu J, Anczukow O, Krainer AR, Zhang MQ, Zhang C. OLego: fast and sensitive mapping of spliced mRNA-Seq reads using small seeds. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41:5149–5163. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt216. doi:gkt216 [pii]10.1093/nar/gkt216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Trapnell C, et al. Transcript assembly and quantification by RNA-Seq reveals unannotated transcripts and isoform switching during cell differentiation. Nature biotechnology. 2010;28:511–515. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1621. doi:10.1038/nbt.1621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]