Abstract

Canonical Hedgehog (HH) signaling leads to the regulation of the GLI code: the sum of all positive and negative functions of all GLI proteins. In humans, the three GLI factors encode context-dependent activities with GLI1 being mostly an activator and GLI3 often a repressor. Modulation of GLI activity occurs at multiple levels, including by co-factors and by direct modification of GLI structure. Surprisingly, the GLI proteins, and thus the GLI code, is also regulated by multiple inputs beyond HH signaling. In normal development and homeostasis these include a multitude of signaling pathways that regulate proto-oncogenes, which boost positive GLI function, as well as tumor suppressors, which restrict positive GLI activity. In cancer, the acquisition of oncogenic mutations and the loss of tumor suppressors – the oncogenic load – regulates the GLI code toward progressively more activating states. The fine and reversible balance of GLI activating GLIA and GLI repressing GLIR states is lost in cancer. Here, the acquisition of GLIA levels above a given threshold is predicted to lead to advanced malignant stages. In this review we highlight the concepts of the GLI code, the oncogenic load, the context-dependency of GLI action, and different modes of signaling integration such as that of HH and EGF. Targeting the GLI code directly or indirectly promises therapeutic benefits beyond the direct blockade of individual pathways.

Keywords: GLI transcription factors, Hedgehog-GLI signaling, Cancer, Development, Signal transduction, Signaling integration, Oncogenes, Stem cells

1. Introduction

The molecular dissection of the Hedgehog (Hh)-Gli signal transduction pathway in insects (e.g. [1–7]) and vertebrates (e.g. [8–16]), has revealed it to be complex and context-dependent with a surprising number of distinct cellular outputs.

Complexity is found at every level of signaling, from multiple ligands with apparently different strengths, and perhaps different properties, multiple membrane components (e.g., PTCH1 vs. PTCH2), a bagful of intracellular regulators and the existence of three GLI proteins in humans that mediate final genomic responses, to ligand-driven pathway activation. Complexity is also found in the tissue – specific expression of different modulators and in the multiple variations of the canonical pathway found in different species.

We are just beginning to understand the meaning of species-specific differences in Hh signaling but what is clear is that a single-species (e.g., mouse)-centric view is not universally informative. How or why organisms would have evolved multiple Ptc receptors (as in worms) for instance, increase the number of Hh ligands or of Gli proteins (as in zebrafish), or constraint HH signaling to primary clia in some species and tissues is unclear but likely to have important clues to speciation and the evolution of the morphogenetic plan (reviewed in [15]).

The outputs are numerous since the HH pathway controls aspects of cell proliferation, survival, migration and stemness. How these are orchestrated over time in developing tissues remains unclear. The GLI proteins also regulate and are regulated by tumor suppressors, such as p53 and this reveals yet another important aspect of HH-GLI signaling: its major role in human cancer (reviewed in [16]).

But perhaps the most intriguing aspect of this and other pathways is their context-dependency. How is it that the same extracellular input can be interpreted differently by responding cells? How is it that reception of a HH ligand can lead to diverse responses in time, space and in different cell types? While the complexity of the pathway makes a complete discussion for a review chapter not feasible, we focus here on the GLI zinc finger transcription factors, which represent the terminal station of the canonical HH signaling path. Whereas other reviews and papers address key aspects of the morphogenetic function of HH ligands (e.g. [17–20]) we elect to focus this review on 3 key points of the highly context-dependent nature of the HH-GLI pathway, where the history and the molecular make-up of the receiving cell determines the qualitative and quantitative output and biological effect: 1 – The GLI code; 2 – Regulation of the GLI code by non-HH signals and by the oncogenic load; and 3 – Mechanisms of GLI regulation. In choosing to do so, here we wish to emphasize the fact that the GLI transcription factors act as key determinants in the interpretation of context- and concentration-dependent canonical HH-GLI signaling in development and disease, and that the GLI code is a signaling integration node.

2. The GLI code

The GLI code model [21,22] considers the total GLI function as a balance of positive activator (GLIA) and negative repressive (GLIR) activities with GLI1 being mostly a positive transcription factor and GLI3 mostly a transcriptional repressor. The GLIA:GLIR ratio is thus critical, being highly regulated, species- and context-specific, and highly dynamic (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Model for the GLI code and its morphogenetic activity leading to the creation of context-dependent diversity. A gradient of HH ligands is interpreted, canonically, by a combinatorial and context-specific distribution of repressor and activator activities of the three GLI proteins, the GLI code. Note that GLI1 and GLI2 have strong activating action and GLI3 is a strong repressor in many contexts. Combinatorial GLI activities are then modified by positive or negative modifiers leading to differential regulation of target genes, which may either respond to create graded levels of expression of specific genes or induce specific genes in given thresholds. The output of these genetic changes is then the creation of spatially and/or temporally distinct outputs and behaviors.

GLI proteins belong to the superfamily of zinc finger transcription factors with five sequential zinc fingers of the C2H2 type constituting the sequence specific DNA binding domain. GLI1 (originally GLI) was first identified as an amplified gene in a human glioblastoma cell line [23,24]. Later on and independently, what turned out to be its fly homolog, Cubitus interruptus (Ci) was identified and placed in the Hh pathway [7,25–27]. GLI1 was not linked to the vertebrate Hh pathway until later [12,28]. While the Drosophila genome encodes only one GLI protein, the mouse and human genomes comprise three: GLI1, GLI2 and GLI3.

One of the most remarkable features of GLI proteins is that in canonical HH signaling they can act as both transcriptional activators and repressors [29–33]. The situation is likely to be complex as all GLI proteins can act as activators or repressors in a stage-dependent and target gene-dependent manner [34]. However, the basic idea of the GLI code is useful as a framework and generally considers GLI1 as an activator and GLI3 mostly as a repressor.

In the absence of HH pathway activity positive GLI function is off, GLI1 is not transcribed [12] and the GLI code is tipped toward a GLIR output, thus leading to pathway silencing. In this context, GLI2/3 proteins are proteolytically processed into C-terminally truncated repressors consisting of an N-terminal repressor domain and the DNA binding zinc fingers, but lacking the C-terminal transactivation domain. There is also evidence for GLI1 isoforms but how these are produced is not clear [35].

GLI processing in the absence of HH signaling is triggered by sequential phosphorylation of Ci or GLI2/3 by Protein Kinase A (PKA), Glycogen Synthase Kinase 3-beta (GSK3β) and Casein Kinase 1 (CK1) [36] followed by proteasomal degradation of the C-terminal region [31,33]. Truncated Ci/GLI repressor binds to GLI sites in HH target promoters, thereby shutting off target gene expression (e.g. [37–39] (reviewed in [16,40])).

Activation of canonical HH signaling abrogates GLI processing allowing full-length and active GLI (GLIA) to enter the nucleus and turn on target gene expression. HH-GLI signaling also has feed-forward and feedback loops. In the latter case, GLI1 directly regulates PATCHED1 (PTCH1), genetically a SMOOTHENED (SMOH) inhibitor, but it also autoregulates itself. GLI2/3A activity leads to GLI1 expression, which further positively boosts GLI1 transcription. How his apparently close loop is broken is unclear, in order to allow precise and reversible control of the GLI code, which is of utmost importance for proper development and health. It is also unclear how the GLI proteins act since there is evidence that the GLI code will be highly refined and meticulously regulated given that GLI1, GLI2 and GLI3 can act in a combinatorial manner [30,34,41–43].

The importance of the critical and tight regulation of the GLI code is illustrated on the one hand by the fact that varying levels of HH-GLI will induce different numbers of neural stem cells in normal development and homeostasis [35,44–48], and also induce different cell fates in the ventral neural tube in response to a morphogenetic gradient of HH ligands [8,9,11,49–51]. On the other hand, genetic and/or epigenetic changes leading to irreversible activation of GLIA, and GLI1 [52], can drive a variety of malignant states ranging from cancers of the brain, skin, breast, prostate and digestive tract to malignancies of the hematopoietic system (e.g. [16,52–60]).

3. Regulation of the GLI code by non-HH signals and by the oncogenic load

The GLI code may be seen as the essential parameter to regulate canonical HH output. Its regulation first appeared to be strictly dependent on the presence of specific levels of HH ligands. Indeed, GLI1 transcription is so far the only general biomarker of a cell's response to HH ligands [12], it can be a diagnostic tool for HH pathway activity [52] and is used to measure the efficiency of SMOH blockers in clinical samples [61–63].

However, surprising data revealed that the GLI1 code and activity can also be modulated by non-HH signals [64,65]. Such regulation occurs in normal and in disease contexts and here we highlight key examples (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Control of the GLI code by the oncogenic load. (A) Under normal homeostatic conditions a fine-tuned balance of HH signaling as well as of parallel proto-oncogenic (e.g., EGF, FGF, PDGF, etc.) and tumor-suppressive pathways leads to precisely controlled levels of GLIA/GLIR. The balance can be tipped one way or another, thus allowing for the highly controlled ON-OFF switch. For simplicity, feed-forward and feedback regulatory loops are not included. (B) In cancer, the loss of tumor suppressors and the presence of mutant oncogenes lead to the massive deregulation of the GLI code and to a constitutively active ON state (GLIA). Note that given the stable genetic changes resulting from gene mutation, the GLI code is no longer under homeostatic control.

3.1. Tumor suppressors negatively regulate GLI1 activity in normal development and homeostasis.

The first example of tumor suppressors regulating normal GLI activity came from the work on p53, where p53 negatively regulates GLI1 [35]. Interestingly, GLI1 also regulates p53 [35,66], thus creating a regulatory loop in which the GLI code is subjected to the precise regulation by p53. Modulation of p53 by GLI1 takes place through MDM factors [35,66] and it remains unclear how p53 represses GLI1 although it involves okadaic acid-sensitive protein phosphatases, possibly PP2A [35].

3.2. Loss of tumor suppressors leads to unregulated GLI1 activity.

Loss of p53 is a common occurrence in human tumors and this provokes the unregulated up-modulation of GLI1, thus leading to increased tumor cell proliferation and increased self-renewal of cancer stem cells [35]. Similarly, PTEN negatively regulates GLI1 activity in different human tumors that include melanomas [65]. This activity may flow through the action of AKT, which positively regulates GLI1 (see below) and is itself negatively modulated by PTEN [65,67], a repressor of AKT (see below). Many other tumor suppressors have since been found to regulate GLI. For example, loss of the SNF5 or Menin leads to activation of GLI1 [68,69].

3.3. Oncogenes, and the pathways that normally regulate proto-oncogenes, positively regulate GLI1.

Not only do common tumor suppressors repress GLI1 but common oncogenes, including RAS, MEK, MYC and AKT, positively regulate GLI1 in different tumor types [65,70]. Moreover, regulation of cMYC [71,72] and possibly of AKT [73] by GLI1, may establish positive feed-forward loops. Together, this insures that GLI1 activity will increase as tumor suppressors are lost and oncogenes gained. This has led to the idea that it is the stepwise gain of oncogenic events and loss of tumor suppressors – named the oncogenic load – that leads to the acquisition of higher and higher GLI1 levels and thus higher and higher levels of GLIA [64]. These increases then drive GLIA beyond thresholds that induce changes in cell fate and behavior, such as the acquisition of metastatic behavior [64,70,71,74].

Note that one key contribution to the oncogenic load in a number of cancers, such as basal cell carcinomas, is the oncogenic mutation of the HH-GLI pathway itself, often through loss of PTCH1 in familial tumors [75,76], or loss of PTCH1, gain of SMOH activity or increase of SHH levels in sporadic cancers [52,53,56,65,70,77–86].

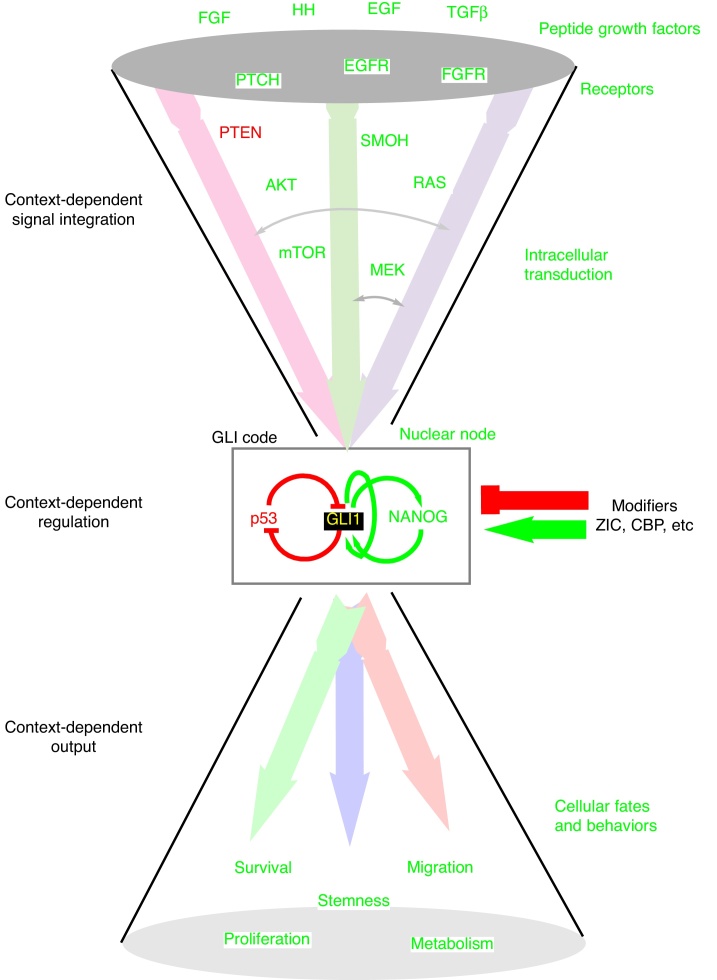

Interestingly, initial evidence for non-HH signaling regulating the GLI code came from studies with frog embryos where GLI2 was found to act in the FGF-Brachyury loop in the early mesoderm [87]. In a separate study, the growth of mouse brain neurospheres was found to be dependent on both EGF and Sonic HH (SHH) signaling but only after decreasing their levels [46,47]. This synergism between EGF and SHH [47], together with the regulation of GLI2 by FGF [87], and the regulation of GLI1 by RAS-MEK-AKT [65] opened a new chapter on the regulation of the GLI code, in this case by non-HH signals. These studies predicted the modulation of the GLI code and of GLI1 by peptide growth factors acting upstream of RAS, MEK and AKT such as FGF, EGF, and many other ligands that trigger receptor tyrosine kinases and activate RAS and downstream events. These findings can therefore help to explain why the GLI code and GLI1 in particular, as the final positive feed-forward output, is important in human cancer. The GLI code, and GLI1, act at the tip of a funnel to integrate multiple outputs. Such a funnel idea [22] (Fig. 3) has strong implications for understanding the logic of signaling but also places the GLI code, and GLI1 in particular, in the line of fire for the development of novel therapies against cancer.

Fig. 3.

A working framework for the GLI code as a node for signal integration. Multiple signaling inputs from diverse pathways, including but not restricted to HH, EGF, FGF, TGFβ, can converge on GLI regulation, changing the GLI code. Integration can also take place above, through crosstalk (gray arrows). The position of the different components is not related to each other but shown as examples of the types of components involved in the signaling cascades. The GLI code, a transcriptional regulatory node, is then modulated by additional context-dependent inputs (arrow and T bar, such as ZIC proteins) that include a negative feedback loop with p53 [35] and a positive feed-forward regulatory loop with NANOG [133]. The outcome, through differential regulation of target genes, is context-dependent and includes change in stemness, survival, proliferation migration and metabolic regulation. This framework can help not only to conceptualize cell behavior resulting from multiple signaling events but also design multi-target therapies to increase efficiency and prevent resistance. Note that each input also has divergent pathways not shown in the scheme.

Additional work has shown that oncogenic RAS can regulate GLI1 in the apparent absence of Smo in pancreatic cancer in mice [88] being required for RAS-mediated tumorigenesis [89], and that EGF signaling cannot only synergize with HH-GLI outputs but also modify its outputs [90–93]. Many other proto-oncogenic and oncogenic inputs have since been shown to regulate the GLI code in different contexts, such as for instance the EWS/FLI1 fusion oncoprotein [94,95], TGFβ signaling [96,97], the mTOR/S6K1 axis [98], WNT signaling [99] (although WNT genes can also be targets and mediators of GLI function [100,101]) and WIP1 [102].

Finally, interactions between pathways may be balanced by direct transcription factor binding such as that between GLI repressors and SMAD proteins, the latter being the mediators of normal and oncogenic BMP and TGFβ signaling [103,104].

3.4. HH and EGF in human basal cell carcinoma

The integration of HH and EGF signaling [46,47,92] has been intensely studied given its developmental interest and its high therapeutic relevance. Here we describe HH-GLI and EGF crosstalk as one example of how a cell can integrate apparently parallel signal inputs.

HH and EGF signaling synergistically promote oncogenic transformation and integration of the signals can occur at different levels. SHH can transactivate the EGF receptor (EGFR) [105]. In addition, EGF activates the RAS-MEK cascade and this can superactivate GLI1 [65]. Moreover, both pathways can converge on the level of common target gene promoters resulting in selective and synergistic modulation of gene expression (reviewed in [59,106]).

Global gene expression studies of human keratinocytes with combined or single activation of HH-GLI and EGFR revealed three classes of target gene responses: (i) genes responding to HH-GLI only, (ii) genes activated or repressed by EGFR only and (iii) genes only or at least preferentially responding to combined and simultaneous activation of both pathways [92]. Notably, class III genes, also referred to as HH-EGFR target genes or cooperation response genes, contain functional GLI binding sites in their promoters, suggesting that signal integration occurs at the level of HH-EGFR target gene promoters [92]. It is important to note that signal cooperation is a selective process as classical HH-GLI target genes such as PTCH1 or HHIP are not affected by parallel EGF signaling in keratinocytes [90,92,93].

In this context, cooperation of EGFR with GLI1 and GLI2 depends on activation of MEK/ERK signaling while PI3K/AKT function is dispensable downstream of EGFR. MEK/ERK induced phosphorylation and activation of the JUN/AP1 transcription factor is the critical event at the terminal end of the EGFR cascade, inducing binding of activated JUN and GLI to common HH-EGFR target promoters, thereby cooperatively regulating target gene expression and transformation [92,93]. It is noteworthy that although basically all receptor tyrosine (RTK) pathways (e.g., HGF, VEGF or FGF) activate MEK/ERK, this is context-dependent as not all of them synergize with HH-GLI in human keratinocytes, possibly because they fail to activate JUN/AP1 in these cells [90]. So far, only EGFR and PDGFRA [107] signaling have been identified as being able to stimulate both MEK/ERK and JUN/AP1 and synergize with HH-GLI in basal cell carcinoma (BCC) (Fig. 4). Importantly, the beneficial effect of EGFR blockade in HH-driven BCC and pancreatic cancer models can be synergistically improved by combined targeting of both pathways [90,93,108].

Fig. 4.

Modes of HH-EGF signaling integration. (A) Canonical HH-GLI signaling activated by binding of SHH to its receptor PTCH results in ciliary localization of SMOH and subsequent GLI activation (GLIA). HH-GLI signaling alone only activates classical GLI targets including HHIP and GLI1 but fails to induce HH-EGFR cooperation target genes. (B) Concomitant activation of HH-GLI and EGF/PDGF signaling (EGFR or PDGFRA) can lead to synergistic interactions [46,47]. Such interactions can result in (i) cross talk between SHH and EGFR in neural stem cells [105], (ii) enhancement of GLI1 activity by RAS/MEK signaling in melanomas and other tumor cells [65], and/or (iii) synergistic promotion of basal cell carcinoma and pancreatic cancer by selective activation of HH-EGFR target genes such as CXCR4, FGF19, SOX9 and TGFA [90,92,93]. In the latter case, integration of HH-EGFR signaling occurs at the level of common target gene promoters. Activation of EGF signaling induces the RAS/RAF/MEK/ERK cascade eventually leading to activation of GLI1 or/and of the JUN/AP1 transcription factor. JUN synergizes with GLI activator forms by co-occupying selected target gene promoters leading to synergistic transcriptional activation of HH-EGFR targets and enhanced tumorigenesis (e.g., BCC and pancreatic cancer).

3.5. HH-GLI and WNT-TCF in human colon cancer

A second example involves the interaction between HH and WNT signaling in human colon cancer [71]. In this context, enhanced GLl1 represses WNT-TCF targets and repression of WNT-TCF targets via dominant-negative dnTCF leads to enhanced HH-GLI targets [71]. This mutually inhibitory interaction is distinct from that seen in other contexts between these two pathways (e.g. [100,109]) and is relevant in the context of the metastatic transition of human colon cancers. Patients with metastases, but not those without, harbor local intestinal tumors that display repressed WNT-TCF and enhanced HH-GLI pathways as assessed by target gene signatures [71]. This switch, from high WNT-TCF, which drives initial intestinal tumorigenesis (e.g. [110]), to low WNT-TCF and enhanced HH-GLI in advanced and metastatic tumors was totally unexpected and is critical as experimental repression of WNT-TCF or enhancement of HH-GLI in xenografts leads to increased metastases in mice [70,71]. Blocking WNT-TCF in advanced cancers is thus not recommended.

The interaction between the HH-GLI and WNT-TCF pathways is complex and stage-dependent: TCF activity, essential for βCATENIN activation of WNT-TCF targets, is required for intestinal initiation and for adenomas. (e.g. [111]). However, while it is also required for advanced human colon cancer cells in vitro [110] it is not required in vivo [71]. Moreover, HH-GLI is dominant: enhanced GLI1 levels, or suppression of PTCH1, rescue the deleterious effects of TCF blockade by dnTCF [71]. There thus appears to be a functional cross-pathway switch at the metastatic transition. WNT-TCF may keep tumors in a crypt-like state and enhanced HH-GLI together with repressed WNT-TCF may allow tumors to change fate and behavior and become metastatic [71].

Modeling such interactions in mice has revealed that Hh-Gli signaling is a parallel requirement since intestinal tumorigenesis can be initiated by loss of Apc but it is fully rescued by concomitant loss of Smo in the intestine [112,113].

Understanding how WNT-TCF and HH-GLI inputs are integrated is of great importance given the essential functions of both pathways in stem cells, human disease and development. Such integration of parallel signaling inputs can take place at multiple levels. In the case of WNT-TCF signaling, there is evidence for binding of βCATENIN, the final output of canonical WNT pathway and both GLI3 C′-terminally deleted repressors and GLI1 [71,114]. Whether this interaction is the key mode of integration remains to be determined.

4. Mechanisms of GLI regulation

4.1. Context-dependent regulation of GLI activity by modulation of DNA binding

GLI proteins regulate target gene promoters by binding the consensus sequence GACCACCCA [115,116]. The two cytosines flanking the central adenine in the consensus sequence are essential for binding, while the other positions allow a certain degree of variation (Fig. 5A) [117,118]. Sequence-specific DNA binding to the cis-regulatory region of a GLI target gene mainly involves zinc fingers 4 and 5 which make extensive base contacts within the 9-mer binding sequence, while fingers 2–3 mainly establish a few contacts with the phosphate backbone. Extensive protein–protein contacts between fingers 1 and 2 apparently contribute to the overall stability of the DNA binding domain [119] (Fig. 5B). Fingers 1 and 2 also provide protein–protein interaction sites to form GLI2, GLI3 and ZIC2 complexes [34].

Fig. 5.

GLI DNA binding and context-dependent target gene regulation. (A) Consensus 9-mer GLI DNA binding motif calculated from experimentally validated GLI binding sites. The motif was generated with a set of 22 experimentally validated GLI binding sites using WebLogo3 [168]. Positions 4C and 6C are essential for DNA binding while basically all other positions allow a certain degree of sequence variation resulting in distinct target gene activation efficiencies. (B) 3D model of the GLI DNA binding domain composed of five zinc fingers and its interaction with the consensus binding sequence. Note that fingers 4 and 5 form extensive base contacts thereby determining binding specificity (source: Protein Databank ID 2GLI; [119]). (C) Non-exhaustive models of context-dependent target gene activation. Here, GLI activator (GLIA) and GLI repressor forms (GLIR) binding the same target sequences refer to the GLI code. (i) Classical target gene activation model with GLIA binding to the promoters of canonical targets such as PTCH1 or HHIP. (ii) Context-dependent interactions of GLIA with co-activators (CoA) or (iii) of GLIR with co-repressors (CoR) modifies the GLI code and expression of HH-GLI targets. (iv) Context-dependent combinatorial binding of GLIA and cooperating transcription factors (TF) (e.g., JUN, SOX2) to common target promoters can also result in synergistic modulation of gene expression.

Although global chromatin immunoprecipitation analyses and in vitro GLI-DNA binding screenings confirmed the consensus sequence as dominant binding site for GLIs [38,39,115,116,120], the importance of GLI binding sequences with 1–2 base pair substitutions is underappreciated and therefore possibly neglected or overseen in many studies. Variations of the consensus sequence while preserving functionality contribute to subtle differences in DNA–protein binding affinity and hence may have a significant impact on the transcriptional output in response to defined GLI activator levels [117,118,121]. For instance, substitution of the consensus cytosine at position 7 for adenine results in a GLI binding site with even enhanced transcriptional response compared to the consensus motif [117].

Variants of the consensus GLI binding site contribute also to selective target gene activation by different GLI proteins. Although all GLI proteins bind the 9-mer consensus sequence with comparable affinity, repressor and activator forms bind the same sites [37], and different GLI proteins affect the same target genes differently [34,41]. For example, GLI2 induces expression of the direct GLI target BCL2 significantly more strongly than GLI1 and systematic analysis of the BCL2 promoter reveals that one of the three validated GLI binding sites accounts for the preferential response to GLI2 [122].

In line with the documented morphogenetic activity of HH-GLI signaling e.g., in the neural tube (reviewed in [123,124] variations in binding site affinity are likely to play a major role in the interpretation of threshold GLI activity levels above which a gene is transcribed or below which the very same gene remains silent. Accordingly, high affinity GLI binding sites in the cis-regulatory region of GLI targets will ensure expression at both high and low levels of GLI activator activity, while targets with low affinity binding sites will respond to high GLI activity only, as demonstrated for the response of neural tube patterning genes controlled by GLI [118]. High affinity binding may be generated by GLI binding site sequence variants and/or multiple repeats of the binding motif. This also suggests that not only quantitative differences in the absolute GLIA protein level or activity determine the context-dependent cellular responses to HH-GLI [50,51,125] but also differential epigenetic modifications of the cis-regulatory regions of GLI targets affecting GLI-DNA binding affinity. Cell-type specific histone acetylations or methylations and/or CpG methylation patterns of GLI target gene promoters are thus likely to modulate both the qualitative and quantitative response to GLI [118], an area in the HH-GLI field that has not yet been explored in great detail.

Distinct combinatorial GLI function could also account for the substantial difference and context-dependency of GLI1 regulated gene networks in the early embryo [30,34,41], as well as in the normal developing cerebellum and in medulloblastoma [120]. A genome-wide survey of GLI1 binding locations revealed numerous GLI1 binding sites in both the normal and malignant tissues, though the location and expression pattern diverged significantly between normal and malignant cells [120].

Although global ChIP approaches successfully and reliably identified classical HH-targets in addition to novel targets, it should be noted that these studies were performed with epitope tagged and overexpressed GLI [38,39,118,120], which may fully mimic endogenous GLI function. It is therefore possible that future approaches will refine our current understanding of context-dependent target gene regulation, once reliable and high-quality antibodies suitable for the isolation of rare endogenous GLI proteins bound to DNA become available.

4.2. Context-specificity of the GLI code by interactions with co-factors

Specificity and activity of transcription factors (TF) heavily depend on interactions with activating or repressing co-factors as well as on co-occurrence of other TF that can bind and/or act cooperatively to regulate target gene expression (Fig. 5C). It follows that the absence or presence of GLI co-factors or cooperative transcription factors within a given cellular context is a major determinant of the transcriptional output.

An example of such an interplay with cofactors that regulates the GLI code is the functional interaction between Zic and Gli proteins [126] (Fig. 3). The Zic factors are nuclear proteins with a GLI-type 5 zinc finger domain [127] that can recognize GLI binding sites albeit with different affinities [128]. They modify GLI outputs [126,128] and can interact through the first two zinc fingers [34,129]. In the early neural plate of frog embryos, Zic2 is expressed in specific longitudinal bands that are adjacent to zones of primary neurogenesis, which is triggered by GLI proteins expressed throughout the plate. The overlap leads to the repression of Gli proneurogenic function by Zic2 in restricted domains, thus leading to the definition of domains of neurogenic differentiation [126]. In this context, Zic2 mimics C-terminally truncated Gli repressors [126]. In a different context Zic2 may mimic positive GLI function as it is required for ventral forebrain fates: Loss of ZIC2 is associated with human holoprosencephaly [130], paralleling the association of this malformation with loss of SHH [131] or GLI2 [132].

A second case that exemplifies a different form of interaction is the cross-functional network of GLI1, p53 and NANOG (made from NANOG1 and NANOGP8 in human cancer cells) (Fig. 3). As discussed above p53 negatively regulates GLI1 [35] and GLI1 negatively regulates p53 [35,66]. p53 would appear to be active in most cells. However, a further layer of regulation is provided by the homeodomain and stemness factor NANOG, which forms a positive feed-forward loop with GLI1 [133]. Interestingly, this loop is also regulated negatively by p53, establishing a highly dynamic node that will be affected by any input that will affect GLI1, NANOG and/or p53 [133] (Fig. 3). Regulatory mechanisms involve regulation of MDM proteins by GLI1, protein phosphatase action, direct GLI regulation of NANOG1 expression and the action of microRNAs [35,66,134,135]. Thus, in adult cells expressing NANOG, likely stem cells and cancer stem cells, the GLI code will be modulated by additional positive mechanisms. As p53 is often lost in cancer, this is predicted to free the GLI1-NANOG loop from negative regulation, allowing unrestricted activity of GLIA. The essential role of NANOG and HH-GLI is demonstrated by their regulation of clonogenic gliomaspheres and by their absolute requirement for the growth of primary human glioblastomas orthotopically engrafted in the brains of host mice [133].

Additional mechanisms of GLI code regulation include interactions with CREB-binding protein (CBP). Genetic and functional studies first carried out in the fruit fly and later in mammalian cells have identified CBP as essential co-factor for Ci and GLI3 mediated target gene activation [136]. Haploinsufficiency of CBP is associated with Rubinstein-Taybi syndrome, a genetic disorder characterized by several developmental anomalies with partially striking similarities to defects observed in patients suffering from Greig's cephalopolysyndactyly syndrome, which is caused by mutations in the GLI3 gene [136–139]. Given the intrinsic histone acetyl transferase (HAT) of CBP/p300 [140], CBP-GLI interactions are likely to cause epigenetic changes of the cis-regulatory region of GLI targets making them more accessible to other transcriptional regulators. In line with this hypothesis, histone acetyl transferase PCAF interacts with GLI1 and enhances HH-GLI target gene expression in medulloblastoma cells by promoting the level of H3K lysine modifications [141]. However, when functioning as ubiquitin ligase, PCAF can also negatively regulate GLI activity under genotoxic stress conditions [142].

Further evidence for epigenetic modifications in context-dependent GLI activity comes from studies of SAP18, a component of the histone deacetylase complex. Recruitment of SAP18 to GLI via binding to the negative GLI regulator Suppressor of Fused (SUFU) [143] is crucial for efficient repression of GLI target genes [144,145]. Like SAP18, Atrophin (Atro) has been identified in fish and flies as a GLI/Ci cofactor required for target gene repression via recruitment of histone deacetylases [146].

TBP-associated factor 9 (TAF9) encodes a transcriptional co-activator that directly interacts with the GLI activator forms GLI1 and GLI2 via their transcriptional activation domain [147]. TAF9 has been shown to enhance the transcriptional activity of GLI, which may play an oncogenic role in lung cancer. Both genetic and chemical inhibition of TAF9-GLI interactions dampen GLI target gene transcription, thus providing a possible therapeutic strategy to target oncogenic HH-GLI signaling downstream of the common HH drug target SMOH [147].

Furthermore, direct interaction of GLI3 with MED12, a subunit of the RNA Polymerase II transcriptional Mediator, enhances the transcriptional response to GLI activator by reversing the Mediator-regulated repression of HH target genes [148].

Transcriptional activity of GLI proteins can be negatively regulated by binding to cofactors including 14-3-3 protein. Notably, PKA phosphorylation at amino acid residues distinct from those enhancing GLI repressor formation promote association of 14-3-3 with GLI2 and GLI3, thereby repressing their transcriptional activity independent of the intrinsic N-terminal repressor domain of GLI2 and GLI3 [149].

Studies addressing selected GLI target gene promoters together with global approaches analyzing the entire landscape of GLI target gene promoters revealed the importance of combinatorial transcription factor binding in context-dependent HH-GLI target gene regulation (Fig. 5C). For instance, high level activation of a subgroup of direct GLI target genes such as IL1R2, JUN/AP1, or ARC was abolished by inhibition of JUN expression as full transcriptional activation of these targets is likely to require co-occupancy of their promoter region by GLI and JUN/AP1, similar to the mechanism accounting for HH and EGF signal integration [90,93,150].

Another example of how combinatorial binding of transcription factors controls context-dependent HH output is illustrated by the finding that co-occupancy of selected GLI targets by GLI1 and SOX2 is required for full activation of a neural gene expression signature [118].

Motif enrichment analyses identified E-box sequences as frequently co-occurring with GLI binding sites in GLI target genes expressed in medulloblastoma [120]. It is therefore possible, that E-box binding bHLH transcription factors cooperate with GLI in the control of tissue specific target gene expression and cancer development, a model that still needs to be confirmed in future studies.

4.3. Modulation of GLI DNA binding affinity and transcriptional activity by post-translational modifications

Fine-tuning and reversible activation/termination of HH-GLI signaling is critical to proper development and health. As outlined in the introduction of this article, numerous reports have provided a wealth of data showing that precise control of HH-GLI signal strength occurs at nearly every level of the canonical HH cascade, ranging from the control of ligand production and ligand-receptor interactions down to the numerous molecular interactions and modifications of GLI proteins eventually determining the molecular phenotype by controlling gene expression in response to pathway activity [20,22,40,54,151].

At the level of GLI code, a number of post-translational modifications of GLI proteins play a fundamental role in its control by affecting GLI stability, subcellular localization and DNA binding ability [152–155] (reviewed in [20,40]). To remain focused on the topic of context-dependent GLI activity, we concentrate here on GLI modifications that directly affect the intrinsic GLI transcriptional activity.

Post-translational modifications of GLI proteins result in drastic modifications of activity. For instance, phosphorylation and acetylation of GLI1/2 at specific amino acid residues have a major impact on the ability of GLI proteins to regulate target genes by modifying their binding to target promoters (see Fig. 6) [156–158].

Fig. 6.

Post-translational modifications regulate GLI transcriptional activity. Fine-tuning of GLI activity by phosphorylation/dephosphorylation and acetylation/deacetylation. Left: fully activated GLI transcription factor with multiple phosphorylated serine/threonine residues in the N-terminal region and the DNA binding domain. In addition, de-acetylation promotes DNA binding affinity and transcriptional activity, respectively. Several kinases (MAPK, S6K, aPKC) and deacetylases catalyze the activation of GLI, while phosphatases, PKA and acetyltransferases negatively regulate GLI activity. Note that PKA phosphorylation of the two amino acid residues C-terminal of the DNA binding domain negatively regulates the transcriptional activity of GLI without affecting processing or stability [161]. ncPKA: non-consensus PKA phosphorylation sites involved in GLI activation.

Atypical Protein Kinase Cι/λ (aPKC) has been identified as both a HH-GLI target gene and major regulator of GLI activity in basal cell carcinoma. aPKC acts downstream of the essential HH effector and drug target SMOH by phosphorylating GLI1 at amino acid residues located in the zinc finger DNA binding domain. GLI1 phosphorylated by aPKC displays enhanced DNA binding and maximum transcriptional activity. Of note, hyperactivation of aPKC in BCC can account for SMOH inhibitor resistance, rendering it a promising drug target for the treatment of cancer patients unresponsive to classical HH pathway inhibitors targeting SMOH [156]. aPKC (also referred to as PRKCI) can affect HH-GLI signaling also by phosphorylating the transcription factor SOX2. Phospho-SOX2 acts a potent transcriptional activator of HH acetyltransferase expression, leading to increased HH ligand production and cell-autonomous HH-GLI activation in lung squamous cell carcinoma [159].

In addition to aPKC phosphorylation of GLI1, several serine and threonine residues in the N-terminal region of GLI1/2 serve as phosphorylation sites involved in GLI activation. In esophageal cancer cells, activation of mTOR/S6K1 signaling leads to S6K1-mediated phosphorylation of Ser85 in GLI1, enhancing GLI1 transcriptional activity by disrupting its interaction with the negative GLI regulator SUFU [98]. Of note, the S6K1 phosphorylation site at Ser85 of GLI1 is located in a D-site motif that serves as MAP kinase binding site required for phosphorylation and activation of GLI1 by JNK and ERK [160] (Fig. 6). S6K1 phosphorylation may therefore not only interfere with SUFU binding but also modify GLI phosphorylation by MAP kinases.

A cluster of non-consensus PKA phosphorylation sites (ncPKA) in close proximity to the SUFU binding site has also been shown to regulate GLI2/3 activation, though the GLI activating kinase responsible for phosphorylating ncPKA sites has not been identified [161]. Whether phosphorylation of ncPKA sites activates GLI2/3 by disrupting the SUFU-GLI complex or by a different mode also needs to be addressed in future studies.

A number of distinct phosphorylation events in the N-terminal region of GLI control full GLIA. This suggests that the N-terminus of GLI proteins serves as integration domain for multiple signals from distinct pathways such as PI3K/AKT, mTOR/S6K or FGF/MEK/ERK signaling [65,98,162]. In line with an integration function of the N-terminal region, deletion of the GLI1 N-terminus abolishes its ectopic activation of FoxA2 (HNF3β) in the neural tube [30] and its hyperactivation in response to FGF treatment [162]. It follows that this integration domain plays a major role in the fine-tuning of GLI activity in normal tissues and importantly, also in the irreversible activation of GLI in cancer cells.

Besides phosphorylation, acetylation of GLI is another parameter in the complex regulation of GLI transcriptional activity. Acetylation of GLI2 at Lys757 by the histone acetyl transferase p300 is a critical negative regulatory modification in HH signaling [157]. Interestingly, acetylated GLI2 displays significantly reduced recruitment to chromatin and consequently only weak activator potential [157]. As the acetylation site is C-terminal of the DNA binding domain it is unlikely that acetylation directly affects DNA binding affinity. Rather, deacetylation may favor the interaction of GLI with chromatin bound proteins and therefore enhance its recruitment to target gene enhancers/promoters. Indeed, HH signaling promotes deacetylation of GLI1/2 via inducing class I histone deacetylases (HDAC), which has been identified as important step in the activation of GLI target gene expression [157,158].

In summary, the remarkable progress in our understanding of GLI modifications highlights context-dependent reversible post-translational modifications as critical determinants of GLI activity. Here, selected kinases (MAPK, S6K1 and aPKC) and deacetylases (HDAC) act as positive regulators, while acetylases (p300), PKA [161] and as yet unidentified phosphatases control the termination of HH signaling via GLI inactivation (Fig. 6). In cancer a number of these components are deregulated, thus contributing to the oncogenic load that regulate the GLI code.

5. Outlook

Whereas great progress has been made to understand how the GLI proteins act (e.g., reviewed in [7,21,58,59,64,163]), much remains to be understood. For example, it is not clear what are effective endogenous concentrations of GLI proteins, how they interact with co-factors, how can they be modified in cells receiving simultaneous inputs, how their activity can be affected by and affect epigenetic changes, how they are protected from cleavage or modification, or even how the pathway is effectively turned off when required.

Documenting the full range of inputs and factors that can modulate their activities in multiple developmental, homeostatic and disease contexts will require much effort but will certainly be a good start. Such knowledge may allow us to begin to understand the logic of signaling in development, in disease and hopefully also in evolution. Thus, we promote the idea that these analyses must be carried out in all possible species and cell types in order to compare and contrast mechanisms and outcomes in a quest to extract essential signaling principles as well as specific solutions for each system.

A more anthropocentric goal is to understand how the GLI code is perverted in human disease, and specifically in cancer, through pathway corruption and the oncogenic load. Such knowledge will possibly lead us to design novel and more efficient therapies against multiple forms of deadly cancers, including those of the brain, intestine, lung, skin, pancreas and other organs. Indeed, the involvement of HH-GLI signaling in normal stem cell lineages and in cancer stem cells [54] raises the possibility that novel molecular approaches to block positive GLI function, reverting the GLI code, could be highly beneficial.

For example, the discovery of aPKC, PI3K/AKT, mTOR/S6K or EGF signaling (see above) as part of the oncogenic load and, importantly, as druggable GLI modulators has already pointed out possible ways of how to design novel combination treatments with improved therapeutic benefit [64,65,90,98,164,165]. However, despite the increasing number of studies of GLI regulation in health and disease, we are only beginning to realize the remarkable complexity of context-dependent regulatory processes affecting the GLI code. The identification and in depth analysis of modifiers of the GLI code will guide us to the development of better rational combination treatments by synergistically targeting the core of the HH-GLI pathway itself, and its modifiers. This will also open therapeutic opportunities to tackle the problem of relapse and drug resistance, as exemplified by the successful targeting of aPKC in SMOH inhibitor-resistant basal cell carcinomas [156].

We are now entering an era where the GLI transcription factors and their modulators are beginning to take center stage as drug targets. Targeting transcription factors for cancer therapy has long been considered not effective, but clearly the number of recent examples such as those mentioned above along with the identification of small molecule GLI antagonists [166,167] provide ample proof-of-concept for the therapeutic relevance of such an approach. Given the essential function of GLIs in normal and malignant stem cells, the systematic identification and functional analysis of GLI modulators, particularly of those amenable to small molecule targeting, as well as studies addressing their context-dependent activity will be an area of intense future research with significant impact on several medical areas such as cancer, tissue regeneration and wound healing.

Acknowledgements

We thank members of our labs for discussion and comments on the manuscript and apologize to the authors of work left out of this review due to space constraints. The readers are encouraged to perform PubMed searches.

Work of the Aberger lab was supported by the Austrian Science Fund FWF (Projects P16518, P20652 and P25629), the Austrian Genome Program Gen-AU/Med-Sys (Project MoGLI), the European FP7 Marie-Curie Initial Training Network HEALING and the priority program Biosciences and Health of the Paris-Lodron University of Salzburg.

Work in the Ruiz i Altaba lab was funded by grants from the Swiss National Science Foundation, the Ligue Suisse Contre le Cancer, the European FP7 Marie-Curie Initial Training Network HEALING, a James McDonnell Foundation 21st Century Science Initiative in Brain Cancer-Research Award and funds from the Départment d’Instruction Publique of the Republic and Canton of Geneva.

Contributor Information

Fritz Aberger, Email: fritz.aberger@sbg.ac.at.

Ariel Ruiz i Altaba, Email: ariel.ruizaltaba@unige.ch.

References

- 1.Tabata T., Eaton S., Kornberg T.B. The Drosophila hedgehog gene is expressed specifically in posterior compartment cells and is a target of engrailed regulation. Genes Dev. 1992;6:2635–2645. doi: 10.1101/gad.6.12b.2635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Forbes A.J., Nakano Y., Taylor A.M., Ingham P.W. Genetic analysis of hedgehog signalling in the Drosophila embryo. Development. 1993;11:2–5. 4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nakano Y., Guerrero I., Hidalgo A., Taylor A., Whittle J.R., Ingham P.W. A protein with several possible membrane-spanning domains encoded by the Drosophila segment polarity gene patched. Nature. 1989;341:508–513. doi: 10.1038/341508a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lee J.J., von Kessler D.P., Parks S., Beachy P.A. Secretion and localized transcription suggest a role in positional signaling for products of the segmentation gene hedgehog. Cell. 1992;71:33–50. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90264-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mohler J., Vani K. Molecular organization and embryonic expression of the hedgehog gene involved in cell-cell communication in segmental patterning of Drosophila. Development. 1992;115:957–971. doi: 10.1242/dev.115.4.957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ingham P.W., McMahon A.P. Hedgehog signaling in animal development: paradigms and principles. Genes Dev. 2001;15:3059–3087. doi: 10.1101/gad.938601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Aza-Blanc P., Kornberg T.B. Ci: a complex transducer of the hedgehog signal. Trends Genet. 1999;15:458–462. doi: 10.1016/s0168-9525(99)01869-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Echelard Y., Epstein D.J., St-Jacques B., Shen L., Mohler J., McMahon J.A. Sonic hedgehog, a member of a family of putative signaling molecules, is implicated in the regulation of CNS polarity. Cell. 1993;75:1417–1430. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90627-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Krauss S., Concordet J.P., Ingham P.W. A functionally conserved homolog of the Drosophila segment polarity gene hh is expressed in tissues with polarizing activity in zebrafish embryos. Cell. 1993;75:1431–1444. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90628-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Riddle R.D., Johnson R.L., Laufer E., Tabin C. Sonic hedgehog mediates the polarizing activity of the ZPA. Cell. 1993;75:1401–1416. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90626-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Roelink H., Augsburger A., Heemskerk J., Korzh V., Norlin S., Ruiz i Altaba A. Floor plate and motor neuron induction by vhh-1, a vertebrate homolog of hedgehog expressed by the notochord. Cell. 1994;76:761–775. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90514-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee J., Platt K.A., Censullo P. Ruiz i Altaba A. Gli1 is a target of Sonic hedgehog that induces ventral neural tube development. Development. 1997;124:2537–2552. doi: 10.1242/dev.124.13.2537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hooper J.E., Scott M.P. Communicating with Hedgehogs. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2005;6:306–317. doi: 10.1038/nrm1622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Goetz S.C., Ocbina P.J., Anderson K.V. The primary cilium as a Hedgehog signal transduction machine. Methods Cell Biol. 2009;94:199–222. doi: 10.1016/S0091-679X(08)94010-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ingham P.W., Nakano Y., Seger C. Mechanisms and functions of Hedgehog signalling across the metazoa. Nat Rev Genet. 2011;12:393–406. doi: 10.1038/nrg2984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ruiz i Altaba A., editor. Landes Bioscience, Springer Science and Business Media. Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers; New York: 2006. HEDGEHOG-GLI signaling in human disease. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Guerrero I., Chiang C. A conserved mechanism of Hedgehog gradient formation by lipid modifications. Trends Cell Biol. 2007;17:1–5. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2006.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Verbeni M., Sanchez O., Mollica E., Siegl-Cachedenier I., Carleton A., Guerrero I. Morphogenetic action through flux-limited spreading. Phys Life Rev. 2013;10:457–475. doi: 10.1016/j.plrev.2013.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kornberg T.B. Cytonemes extend their reach. EMBO J. 2013;32:1658–1659. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2013.115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Briscoe J., Therond P.P. The mechanisms of Hedgehog signalling and its roles in development and disease. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2013;14:416–429. doi: 10.1038/nrm3598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ruiz i Altaba A. Catching a Gli-mpse of Hedgehog. Cell. 1997;90:193–196. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80325-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ruiz i Altaba A., Mas C., Stecca B. The Gli code: an information nexus regulating cell fate, stemness and cancer. Trends Cell Biol. 2007;17:438–447. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2007.06.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kinzler K.W., Ruppert J.M., Bigner S.H., Vogelstein B. The GLI gene is a member of the Kruppel family of zinc finger proteins. Nature. 1988;332:371–374. doi: 10.1038/332371a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kinzler K.W., Bigner S.H., Bigner D.D., Trent J.M., Law M.L., O’Brien S.J. Identification of an amplified, highly expressed gene in a human glioma. Science. 1987;236:70–73. doi: 10.1126/science.3563490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Aza-Blanc P., Ramirez-Weber F.A., Laget M.P., Schwartz C., Kornberg T.B. Proteolysis that is inhibited by hedgehog targets Cubitus interruptus protein to the nucleus and converts it to a repressor. Cell. 1997;89:1043–1053. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80292-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dominguez M., Brunner M., Hafen E., Basler K. Sending and receiving the hedgehog signal: control by the Drosophila Gli protein Cubitus interruptus. Science. 1996;272:1621–1625. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5268.1621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Alexandre C., Jacinto A., Ingham P.W. Transcriptional activation of hedgehog target genes in Drosophila is mediated directly by the cubitus interruptus protein, a member of the GLI family of zinc finger DNA-binding proteins. Genes Dev. 1996;10:2003–2013. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.16.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sasaki H., Hui C., Nakafuku M., Kondoh H. A binding site for Gli proteins is essential for HNF-3beta floor plate enhancer activity in transgenics and can respond to Shh in vitro. Development. 1997;124:1313–1322. doi: 10.1242/dev.124.7.1313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Aza-Blanc P., Lin H.Y., Ruiz i Altaba A., Kornberg T.B. Expression of the vertebrate Gli proteins in Drosophila reveals a distribution of activator and repressor activities. Development. 2000;127:4293–4301. doi: 10.1242/dev.127.19.4293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ruiz i Altaba A. Gli proteins encode context-dependent positive and negative functions: implications for development and disease. Development. 1999;126:3205–3216. doi: 10.1242/dev.126.14.3205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wang B., Fallon J.F., Beachy P.A. Hedgehog-regulated processing of Gli3 produces an anterior/posterior repressor gradient in the developing vertebrate limb. Cell. 2000;100:423–434. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80678-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bai C.B., Stephen D., Joyner A.L. All mouse ventral spinal cord patterning by hedgehog is Gli dependent and involves an activator function of Gli3. Dev Cell. 2004;6:103–115. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(03)00394-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pan Y., Bai C.B., Joyner A.L., Wang B. Sonic hedgehog signaling regulates Gli2 transcriptional activity by suppressing its processing and degradation. Mol Cell Biol. 2006;26:3365–3377. doi: 10.1128/MCB.26.9.3365-3377.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nguyen V., Chokas A.L., Stecca B., Ruiz i Altaba A. Cooperative requirement of the Gli proteins in neurogenesis. Development. 2005;132:3267–3279. doi: 10.1242/dev.01905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Stecca B., Ruiz i Altaba A. A GLI1-p53 inhibitory loop controls neural stem cell and tumour cell numbers. EMBO J. 2009;28:663–676. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2009.16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Price M.A., Kalderon D. Proteolysis of the Hedgehog signaling effector Cubitus interruptus requires phosphorylation by glycogen synthase kinase 3 and casein kinase 1. Cell. 2002;108:823–835. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00664-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Muller B., Basler K. The repressor and activator forms of Cubitus interruptus control Hedgehog target genes through common generic gli-binding sites. Development. 2000;127:2999–3007. doi: 10.1242/dev.127.14.2999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Vokes S.A., Ji H., McCuine S., Tenzen T., Giles S., Zhong S. Genomic characterization of Gli-activator targets in sonic hedgehog-mediated neural patterning. Development. 2007;134:1977–1989. doi: 10.1242/dev.001966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Vokes S.A., Ji H., Wong W.H., McMahon A.P. A genome-scale analysis of the cis-regulatory circuitry underlying sonic hedgehog-mediated patterning of the mammalian limb. Genes Dev. 2008;22:2651–2663. doi: 10.1101/gad.1693008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hui C.C., Angers S. Gli proteins in development and disease. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2011;27:513–537. doi: 10.1146/annurev-cellbio-092910-154048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ruiz i Altaba A. Combinatorial Gli gene function in floor plate and neuronal inductions by sonic hedgehog. Development. 1998;125:2203–2212. doi: 10.1242/dev.125.12.2203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Park H.L., Bai C., Platt K.A., Matise M.P., Beeghly A., Hui C.C. Mouse Gli1 mutants are viable but have defects in SHH signaling in combination with a Gli2 mutation. Development. 2000;127:1593–1605. doi: 10.1242/dev.127.8.1593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Blaess S., Corrales J.D., Joyner A.L. Sonic hedgehog regulates Gli activator and repressor functions with spatial and temporal precision in the mid/hindbrain region. Development. 2006;133:1799–1809. doi: 10.1242/dev.02339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lai K., Kaspar B.K., Gage F.H., Schaffer D.V. Sonic hedgehog regulates adult neural progenitor proliferation in vitro and in vivo. Nat Neurosci. 2003;6:21–27. doi: 10.1038/nn983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Machold R., Hayashi S., Rutlin M., Muzumdar M.D., Nery S., Corbin J.G. Sonic hedgehog is required for progenitor cell maintenance in telencephalic stem cell niches. Neuron. 2003;39:937–950. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00561-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Palma V., Lim D.A., Dahmane N., Sanchez P., Brionne T.C., Herzberg C.D. Sonic hedgehog controls stem cell behavior in the postnatal and adult brain. Development. 2005;132:335–344. doi: 10.1242/dev.01567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Palma V., Ruiz i Altaba A. Hedgehog-GLI signaling regulates the behavior of cells with stem cell properties in the developing neocortex. Development. 2004;131:337–345. doi: 10.1242/dev.00930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ahn S., Joyner A.L. In vivo analysis of quiescent adult neural stem cells responding to Sonic hedgehog. Nature. 2005;437:894–897. doi: 10.1038/nature03994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Stamataki D., Ulloa F., Tsoni S.V., Mynett A., Briscoe J. A gradient of Gli activity mediates graded sonic hedgehog signaling in the neural tube. Genes Dev. 2005;19:626–641. doi: 10.1101/gad.325905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Balaskas N., Ribeiro A., Panovska J., Dessaud E., Sasai N., Page K.M. Gene regulatory logic for reading the sonic hedgehog signaling gradient in the vertebrate neural tube. Cell. 2012;148:273–284. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.10.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Dessaud E., Yang L.L., Hill K., Cox B., Ulloa F., Ribeiro A. Interpretation of the sonic hedgehog morphogen gradient by a temporal adaptation mechanism. Nature. 2007;450:717–720. doi: 10.1038/nature06347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Dahmane N., Lee J., Robins P., Heller P., Ruiz i Altaba A. Activation of the transcription factor Gli1 and the sonic hedgehog signalling pathway in skin tumours. Nature. 1997;389:876–881. doi: 10.1038/39918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Dahmane N., Sanchez P., Gitton Y., Palma V., Sun T., Beyna M. The sonic hedgehog-Gli pathway regulates dorsal brain growth and tumorigenesis. Development. 2001;128:5201–5212. doi: 10.1242/dev.128.24.5201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ruiz i Altaba A., Sanchez P., Dahmane N. Gli and hedgehog in cancer: tumours, embryos and stem cells. Nat Rev Cancer. 2002;2:361–372. doi: 10.1038/nrc796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Beachy P.A., Karhadkar S.S., Berman D.M. Tissue repair and stem cell renewal in carcinogenesis. Nature. 2004;432:324–331. doi: 10.1038/nature03100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Clement V., Sanchez P., de Tribolet N., Radovanovic I., Ruiz i Altaba A. HEDGEHOG-GLI1 signaling regulates human glioma growth, cancer stem cell self-renewal, and tumorigenicity. Curr Biol. 2007;17:165–172. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2006.11.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Peacock C.D., Wang Q., Gesell G.S., Corcoran-Schwartz I.M., Jones E., Kim J. Hedgehog signaling maintains a tumor stem cell compartment in multiple myeloma. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:4048–4053. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0611682104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kasper M., Regl G., Frischauf A.M., Aberger F. GLI transcription factors: mediators of oncogenic Hedgehog signalling. Eur J Cancer. 2006;42:437–445. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2005.08.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Aberger F., Kern D., Greil R., Hartmann T.N. Canonical and noncanonical Hedgehog/GLI signaling in hematological malignancies. Vitam Horm. 2012;88:25–54. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-394622-5.00002-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Teglund S., Toftgard R. Hedgehog beyond medulloblastoma and basal cell carcinoma. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2010;1805:181–208. doi: 10.1016/j.bbcan.2010.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Tang J.Y., Mackay-Wiggan J.M., Aszterbaum M., Yauch R.L., Lindgren J., Chang K. Inhibiting the hedgehog pathway in patients with the basal-cell nevus syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:2180–2188. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1113538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Von Hoff D.D., LoRusso P.M., Rudin C.M., Reddy J.C., Yauch R.L., Tibes R. Inhibition of the hedgehog pathway in advanced basal-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:1164–1172. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0905360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kim D.J., Kim J., Spaunhurst K., Montoya J., Khodosh R., Chandra K. Open-label, exploratory phase II trial of oral itraconazole for the treatment of basal cell carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32:745–751. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.49.9525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Stecca B., Ruiz i Altaba A. Context-dependent regulation of the GLI code in cancer by HEDGEHOG and non-HEDGEHOG signals. J Mol Cell Biol. 2010;2:84–95. doi: 10.1093/jmcb/mjp052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Stecca B., Mas C., Clement V., Zbinden M., Correa R., Piguet V. Melanomas require HEDGEHOG-GLI signaling regulated by interactions between GLI1 and the RAS-MEK/AKT pathways. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:5895–5900. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0700776104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Abe Y., Oda-Sato E., Tobiume K., Kawauchi K., Taya Y., Okamoto K. Hedgehog signaling overrides p53-mediated tumor suppression by activating Mdm2. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:4838–4843. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0712216105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Riobo N.A., Lu K., Ai X., Haines G.M., Emerson C.P., Jr. Phosphoinositide 3-kinase and Akt are essential for sonic hedgehog signaling. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:4505–4510. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0504337103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Jagani Z., Mora-Blanco E.L., Sansam C.G., McKenna E.S., Wilson B., Chen D. Loss of the tumor suppressor Snf5 leads to aberrant activation of the Hedgehog-Gli pathway. Nat Med. 2010;16:1429–1433. doi: 10.1038/nm.2251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Gurung B., Feng Z., Hua X. Menin directly represses gli1 expression independent of canonical hedgehog signaling. Mol Cancer Res. 2013;11:1215–1222. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-13-0170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Varnat F., Duquet A., Malerba M., Zbinden M., Mas C., Gervaz P. Human colon cancer epithelial cells harbour active HEDGEHOG-GLI signalling that is essential for tumour growth, recurrence, metastasis and stem cell survival and expansion. EMBO Mol Med. 2009;1:338–351. doi: 10.1002/emmm.200900039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Varnat F., Siegl-Cachedenier I., Malerba M., Gervaz P., Ruiz i Altaba A. Loss of WNT-TCF addiction and enhancement of HH-GLI1 signalling define the metastatic transition of human colon carcinomas. EMBO Mol Med. 2010;2:440–457. doi: 10.1002/emmm.201000098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Yoon J.W., Gallant M., Lamm M.L., Iannaccone S., Vieux K.F., Proytcheva M. Noncanonical regulation of the Hedgehog mediator GLI1 by c-MYC in Burkitt lymphoma. Mol Cancer Res. 2013;11:604–615. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-12-0441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Agarwal N.K., Qu C., Kunkalla K., Liu Y., Vega F. Transcriptional regulation of serine/threonine protein kinase (AKT) genes by glioma-associated oncogene homolog 1. J Biol Chem. 2013;288:15390–15401. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.425249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Ruiz i Altaba A., Stecca B., Sanchez P. Hedgehog – Gli signaling in brain tumors: stem cells and paradevelopmental programs in cancer. Cancer Lett. 2004;204:145–157. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3835(03)00451-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Hahn H., Wicking C., Zaphiropoulous P.G., Gailani M.R., Shanley S., Chidambaram A. Mutations of the human homolog of Drosophila patched in the nevoid basal cell carcinoma syndrome. Cell. 1996;85:841–851. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81268-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Johnson R.L., Rothman A.L., Xie J., Goodrich L.V., Bare J.W., Bonifas J.M. Human homolog of patched, a candidate gene for the basal cell nevus syndrome. Science. 1996;272:1668–1671. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5268.1668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Xie J., Murone M., Luoh S.M., Ryan A., Gu Q., Zhang C. Activating smoothened mutations in sporadic basal-cell carcinoma. Nature. 1998;391:90–92. doi: 10.1038/34201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Gailani M.R., Stahle-Backdahl M., Leffell D.J., Glynn M., Zaphiropoulos P.G., Pressman C. The role of the human homologue of Drosophila patched in sporadic basal cell carcinomas. Nat Genet. 1996;14:78–81. doi: 10.1038/ng0996-78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Goodrich L.V., Milenkovic L., Higgins K.M., Scott M.P. Altered neural cell fates and medulloblastoma in mouse patched mutants. Science. 1997;277:1109–1113. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5329.1109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Berman D.M., Karhadkar S.S., Maitra A., Montes De Oca R., Gerstenblith M.R., Briggs K. Widespread requirement for Hedgehog ligand stimulation in growth of digestive tract tumours. Nature. 2003;425:846–851. doi: 10.1038/nature01972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Karhadkar S.S., Bova G.S., Abdallah N., Dhara S., Gardner D., Maitra A. Hedgehog signalling in prostate regeneration, neoplasia and metastasis. Nature. 2004;431:707–712. doi: 10.1038/nature02962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Watkins D.N., Berman D.M., Burkholder S.G., Wang B., Beachy P.A., Baylin S.B. Hedgehog signalling within airway epithelial progenitors and in small-cell lung cancer. Nature. 2003;422:313–317. doi: 10.1038/nature01493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Sanchez P., Hernandez A.M., Stecca B., Kahler A.J., DeGueme A.M., Barrett A. Inhibition of prostate cancer proliferation by interference with sonic hedgehog-GLI1 signaling. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:12561–12566. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0404956101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Yuan Z., Goetz J.A., Singh S., Ogden S.K., Petty W.J., Black C.C. Frequent requirement of hedgehog signaling in non-small cell lung carcinoma. Oncogene. 2007;26:1046–1055. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Park K.S., Martelotto L.G., Peifer M., Sos M.L., Karnezis A.N., Mahjoub M.R. A crucial requirement for Hedgehog signaling in small cell lung cancer. Nat Med. 2011;17:1504–1508. doi: 10.1038/nm.2473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Sheng T., Li C., Zhang X., Chi S., He N., Chen K. Activation of the hedgehog pathway in advanced prostate cancer. Mol Cancer. 2004;3:29. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-3-29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Brewster R., Mullor J.L., Ruiz i Altaba A. Gli2 functions in FGF signaling during antero-posterior patterning. Development. 2000;127:4395–4405. doi: 10.1242/dev.127.20.4395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Nolan-Stevaux O., Lau J., Truitt M.L., Chu G.C., Hebrok M., Fernandez-Zapico M.E. GLI1 is regulated through Smoothened-independent mechanisms in neoplastic pancreatic ducts and mediates PDAC cell survival and transformation. Genes Dev. 2009;23:24–36. doi: 10.1101/gad.1753809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Rajurkar M., De Jesus-Monge W.E., Driscoll D.R., Appleman V.A., Huang H., Cotton J.L. The activity of Gli transcription factors is essential for Kras-induced pancreatic tumorigenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:E1038–E1047. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1114168109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Eberl M., Klingler S., Mangelberger D., Loipetzberger A., Damhofer H., Zoidl K. Hedgehog-EGFR cooperation response genes determine the oncogenic phenotype of basal cell carcinoma and tumour-initiating pancreatic cancer cells. EMBO Mol Med. 2012;4:218–233. doi: 10.1002/emmm.201100201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Gotschel F., Berg D., Gruber W., Bender C., Eberl M., Friedel M. Synergism between Hedgehog-GLI and EGFR signaling in Hedgehog-responsive human medulloblastoma cells induces downregulation of canonical Hedgehog-target genes and stabilized expression of GLI1. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e65403. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0065403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Kasper M., Schnidar H., Neill G.W., Hanneder M., Klingler S., Blaas L. Selective modulation of Hedgehog/GLI target gene expression by epidermal growth factor signaling in human keratinocytes. Mol Cell Biol. 2006;26:6283–6298. doi: 10.1128/MCB.02317-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Schnidar H., Eberl M., Klingler S., Mangelberger D., Kasper M., Hauser-Kronberger C. Epidermal growth factor receptor signaling synergizes with Hedgehog/GLI in oncogenic transformation via activation of the MEK/ERK/JUN pathway. Cancer Res. 2009;69:1284–1292. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-2331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Zwerner J.P., Joo J., Warner K.L., Christensen L., Hu-Lieskovan S., Triche T.J. The EWS/FLI1 oncogenic transcription factor deregulates GLI1. Oncogene. 2008;27:3282–3291. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Beauchamp E., Bulut G., Abaan O., Chen K., Merchant A., Matsui W. GLI1 is a direct transcriptional target of EWS-FLI1 oncoprotein. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:9074–9082. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M806233200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Dennler S., Andre J., Alexaki I., Li A., Magnaldo T., ten Dijke P. Induction of sonic hedgehog mediators by transforming growth factor-beta: Smad3-dependent activation of Gli2 and Gli1 expression in vitro and in vivo. Cancer Res. 2007;67:6981–6986. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-0491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Dennler S., Andre J., Verrecchia F., Mauviel A. Cloning of the human GLI2 Promoter: transcriptional activation by transforming growth factor-beta via SMAD3/beta-catenin cooperation. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:31523–31531. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.059964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Wang Y., Ding Q., Yen C.J., Xia W., Izzo J.G., Lang J.Y. The crosstalk of mTOR/S6K1 and Hedgehog pathways. Cancer Cell. 2012;21:374–387. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2011.12.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Alvarez-Medina R., Cayuso J., Okubo T., Takada S., Marti E. Wnt canonical pathway restricts graded Shh/Gli patterning activity through the regulation of Gli3 expression. Development. 2008;135:237–247. doi: 10.1242/dev.012054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Mullor J.L., Dahmane N., Sun T., Ruiz i Altaba A. Wnt signals are targets and mediators of Gli function. Curr Biol. 2001;11:769–773. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(01)00229-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Yang S.H., Andl T., Grachtchouk V., Wang A., Liu J., Syu L.J. Pathological responses to oncogenic Hedgehog signaling in skin are dependent on canonical Wnt/beta3-catenin signaling. Nat Genet. 2008;40:1130–1135. doi: 10.1038/ng.192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Pandolfi S., Montagnani V., Penachioni J.Y., Vinci M.C., Olivito B., Borgognoni L. WIP1 phosphatase modulates the Hedgehog signaling by enhancing GLI1 function. Oncogene. 2013;32:4737–4747. doi: 10.1038/onc.2012.502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Liu F., Massague J., Ruiz i Altaba A. Carboxy-terminally truncated Gli3 proteins associate with Smads. Nat Genet. 1998;20:325–326. doi: 10.1038/3793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Maurya A.K., Tan H., Souren M., Wang X., Wittbrodt J., Ingham P.W. Integration of Hedgehog and BMP signalling by the engrailed2a gene in the zebrafish myotome. Development. 2011;138:755–765. doi: 10.1242/dev.062521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Reinchisi G., Parada M., Lois P., Oyanadel C., Shaughnessy R., Gonzalez A. Sonic hedgehog modulates EGFR dependent proliferation of neural stem cells during late mouse embryogenesis through EGFR transactivation. Front Cell Neurosci. 2013;7:166. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2013.00166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Mangelberger D., Kern D., Loipetzberger A., Eberl M., Aberger F. Cooperative Hedgehog-EGFR signaling. Front Biosci J Virt Libr. 2012;17:90–99. doi: 10.2741/3917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Pelczar P., Zibat A., van Dop W.A., Heijmans J., Bleckmann A., Gruber W. Inactivation of Patched1 in mice leads to development of gastrointestinal stromal-like tumors that express Pdgfralpha but not kit. Gastroenterology. 2013;144:134–144. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2012.09.061. e6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Mimeault M., Batra S.K. Frequent deregulations in the hedgehog signaling network and cross-talks with the epidermal growth factor receptor pathway involved in cancer progression and targeted therapies. Pharmacol Rev. 2010;62:497–524. doi: 10.1124/pr.109.002329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Borycki A., Brown A.M., Emerson C.P., Jr. Shh and Wnt signaling pathways converge to control Gli gene activation in avian somites. Development. 2000;127:2075–2087. doi: 10.1242/dev.127.10.2075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.van de Wetering M., Sancho E., Verweij C., de Lau W., Oving I., Hurlstone A. The beta-catenin/TCF-4 complex imposes a crypt progenitor phenotype on colorectal cancer cells. Cell. 2002;111:241–250. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)01014-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Kinzler K.W., Vogelstein B. Lessons from hereditary colorectal cancer. Cell. 1996;87:159–170. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81333-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Varnat F., Zacchetti G., Ruiz i Altaba A. Hedgehog pathway activity is required for the lethality and intestinal phenotypes of mice with hyperactive Wnt signaling. Mech Dev. 2010;127:73–81. doi: 10.1016/j.mod.2009.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Arimura S., Matsunaga A., Kitamura T., Aoki K., Aoki M., Taketo M.M. Reduced level of smoothened suppresses intestinal tumorigenesis by down-regulation of Wnt signaling. Gastroenterology. 2009;137:629–638. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.04.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Ulloa F., Itasaki N., Briscoe J. Inhibitory Gli3 activity negatively regulates Wnt/beta-catenin signaling. Curr Biol. 2007;17:545–550. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2007.01.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Kinzler K.W., Vogelstein B. The GLI gene encodes a nuclear protein which binds specific sequences in the human genome. Mol Cell Biol. 1990;10:634–642. doi: 10.1128/mcb.10.2.634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Hallikas O., Palin K., Sinjushina N., Rautiainen R., Partanen J., Ukkonen E. Genome-wide prediction of mammalian enhancers based on analysis of transcription-factor binding affinity. Cell. 2006;124:47–59. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.10.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Winklmayr M., Schmid C., Laner-Plamberger S., Kaser A., Aberger F., Eichberger T. Non-consensus GLI binding sites in Hedgehog target gene regulation. BMC Mol Biol. 2010;11:2. doi: 10.1186/1471-2199-11-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Peterson K.A., Nishi Y., Ma W., Vedenko A., Shokri L., Zhang X. Neural-specific Sox2 input and differential Gli-binding affinity provide context and positional information in Shh-directed neural patterning. Genes Dev. 2012;26:2802–2816. doi: 10.1101/gad.207142.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Pavletich N.P., Pabo C.O. Crystal structure of a five-finger GLI-DNA complex: new perspectives on zinc fingers. Science. 1993;261:1701–1707. doi: 10.1126/science.8378770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Lee E.Y., Ji H., Ouyang Z., Zhou B., Ma W., Vokes S.A. Hedgehog pathway-regulated gene networks in cerebellum development and tumorigenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:9736–9741. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1004602107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Parker D.S., White M.A., Ramos A.I., Cohen B.A., Barolo S. The cis-regulatory logic of Hedgehog gradient responses: key roles for gli binding affinity, competition, and cooperativity. Sci Signal. 2011;4:ra38. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2002077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Regl G., Kasper M., Schnidar H., Eichberger T., Neill G.W., Philpott M.P. Activation of the BCL2 promoter in response to Hedgehog/GLI signal transduction is predominantly mediated by GLI2. Cancer Res. 2004;64:7724–7731. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-1085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]