Abstract

Purpose

Detailed knowledge of cell surface proteins present during early embryonic development remains limited for most cell lineages. Due to the relevance of cell surface proteins in their functional roles controlling cell signaling and their utility as accessible, non-genetic markers for cell identification and sorting, the goal of this study was to provide new information regarding the cell surface proteins present during early mouse embryonic development.

Experimental Design

Using the Cell Surface Capture Technology, the cell surface N-glycoproteomes of three cell lines and one in vitro differentiated cell type representing distinct cell fates and stages in mouse embryogenesis were assessed.

Results

Altogether, more than 600 cell surface N-glycoproteins were identified represented by >5500 N-glycopeptides.

Conclusions and Clinical Relevance

The development of new, informative cell surface markers for the reliable identification and isolation of functionally defined subsets of cells from early developmental stages will advance the use of stem cell technologies for mechanistic developmental studies, including disease modeling and drug discovery.

Keywords: Biomarkers, Cardiovascular, Glycoproteins, Plasma membrane, Glycoproteomics

Expanded understanding of the principles dictating the earliest stages of embryonic development will benefit mechanistic studies of cell lineage restriction and facilitate the use of stem cells for disease modeling and regenerative medicine efforts. While a complex transcriptional hierarchy within the early stages of embryonic development has been well documented for many lineages, including cardiac [1] knowledge of the events occurring at the cell surface remains limited for most lineages. Due to the relevance of cell surface proteins for defining how cells can sense and respond to their microenvironment, mapping of cell surface proteins would provide critical insight regarding signaling events in early development as well as provide a means for accessible, non-genetic cell identification and tracking through the use of immunophenotyping [2]. While a cell surface lineage map has been established for hematopoietic stem cell subpopulations [3] similarly complete surface protein maps are not yet available for other stem cell progeny. A major hurdle to the development of surface marker maps is the technical challenge of discovering new, cell type-specific markers. While some progress has been made using transcriptomics, antibody screens, and proteomics [4–7], gene expression patterns correlate poorly with protein abundance on the cell surface [8] and limitations to antibody screens include the limited availability and specificity of monoclonal antibodies that recognize surface exposed epitopes.

Due to the limited amount of primary tissue available to study early developmental stages, discovery-based proteomic analysis is more practically achieved using comparable stage embryo-derived stem cell culture models. In this study, three cell lines and one in vitro differentiated cell type representing distinct cell fates and stages in mouse embryogenesis were assessed. The earliest developmental stages included the pluripotent epiblast and extraembryonic primitive endoderm-like, represented by embryonic stem cells (mESC) and extraembryonic endoderm (XEN) cells, respectively. Later developmental stages include mESC-derived cardiomyocytes (mESC-CM) and embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs). Using a selective approach that exploits the prediction that >90% of cell surface proteins are glycosylated [9], we have generated unique views of surface N-glycoproteomes on these four cell types. Our approach, termed Cell Surface Capture (CSC-Technology), is an antibody-independent strategy that uses affinity enrichment of N-glycoproteins and mass spectrometry to achieve >85% specificity for cell surface proteins while simultaneously determining N-glycosite occupancy and membrane topology [10–12]. The benefits of CSC-Technology include its high specificity for surface-accessible proteins and its ability to directly verify the extracellular domains by identifying the site of N-glycosylation, thereby avoiding reliance on database annotations and/or prediction algorithms to determine protein localization. We have previously published qualitative N-glycoproteomes of mESC, miPSC, C2C12 myoblasts, human fibroblasts, hiPSC and hESC [8, 10, 12]. The current dataset extends qualitative descriptions of the cell surface N-glycoproteome to MEFs and mESC-CM and reports a quantitative comparison of mESC and XEN based on stable isotope labeling of amino acids in cell culture (SILAC) analysis. The quantitative comparison of XEN and mESC is expected to shed light on markers for identifying and isolating lineage restricted progenitors from blastocysts, and the analyses of MEFs and mESC-CMs are included to benefit the future development of markers for identifying and isolating cardiomyogenic progeny derived from pluripotent stem cells.

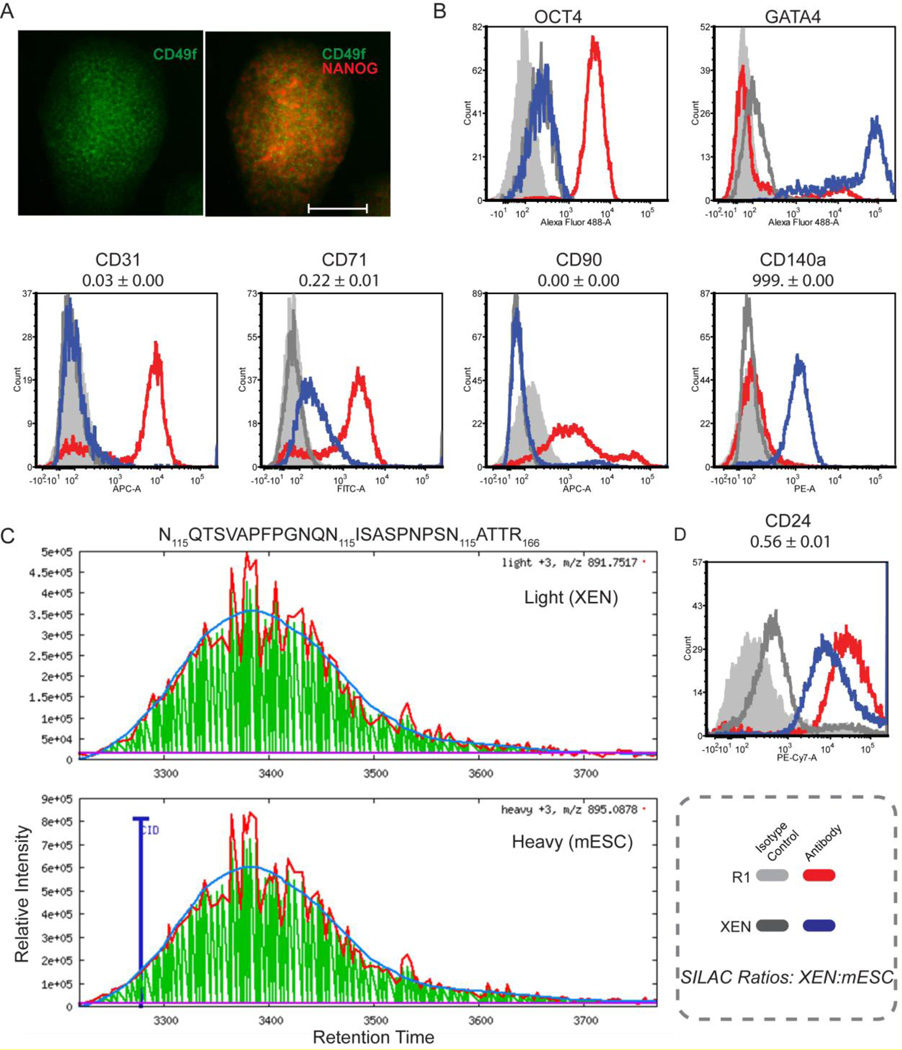

Mouse ESC (R1[13]), XEN (X10[14]) and mouse embryonic fibroblasts (STO) were cultured as described [12, 15–17], with the exception that mESC and XEN were cultured in SILAC media containing dialyzed serum [18]. Under these conditions, mESC stain positive for OCT4 and CD49f and XEN are positive for GATA4 (Fig 1A,B). For SILAC, mESC were cultured with heavy stable isotope versions of lysine (13C6, 15N2) and arginine (13C6, 15N4), whereas XEN were cultured in light. For cardiac differentiation, mESCs (syNP4 subclone of R1 [19]) were differentiated as described [20] and puromycin-selected CMs were robustly positive for reference cardiac markers ACTN1, TNNI3, TNNT2, and MLC2v by day 17 of differentiation (Figure 2C), which was the time point used for proteomic analysis. For each cell type, approximately 1E8 cells per biological replicate (n≥3) were taken through the CSC-Technology workflow as reported [10–12, 21] with details provided in the supplement, with the exception of the mESC/XEN SILAC which used 1E6 cells per replicate, due to slower growth rates in the SILAC media (e.g. dialyzed FBS). For flow cytometry, cells were stained as described [12] with antibody details provided in the supplemental methods. Data were acquired on a BD LSRII flow cytometer (BD Biosciences) and analyzed using FCSExpress V3 (DeNovo Software) and histograms represent an average of at least three biological replicates.

Figure 1. Surface N-glycoproteins on mESC and XEN.

A) Immunofluorescence image of mESC stained for CD49f and NANOG. Scale bar = 100 µm. B) Flow cytometry histograms of reference intracellular markers OCT4 and GATA4 (top) and surface markers identified via the CSC-Technology. For each surface marker, the quantitative ratio measured by SILAC is provided. C) Representative image of peak integration by ASAPratio of the reconstructed ion chromatogram for one peptide for CD24. D) Flow cytometry histograms for CD24 showing higher abundance in mESC (shift to the right), consistent with SILAC data.

Figure 2. Surface N-glycoproteins on cardiomyocytes.

A) Annotated MS/MS spectrum of an N-glycopeptide from SIRPA. B) Predicted membrane topology of SIRPA demonstrating experimentally observed sequence coverage of the extracellular domain using the CSC-Technology. Image generated using Protter [27]. C) Flow cytometry histograms of intracellular reference markers on day 28 mESC-CMs. D) Flow cytometry histograms selected surface markers on day 28 mESC-CMs.

165 cell surface N-glycoproteins were identified in the mESC:XEN SILAC comparison (Table S1). Six proteins were found exclusively in XEN (F3, PDGFRa, PVR, TEK, SLCO3A1, PTH1R) and 24 (ALCAM, ALPL, BST3, CD38, CNNM2, DSG2, FAT1, FN1, GLG1, GPC3, H2–K1, LNPEP, LPAR4, PVRL1, S1PR2, SLC46A1, SLC5A1, SLC6A6, SLCO4A1, ST14, THY1, TSPAN31, SFP11, LY75) were found exclusively in mESCs. The data for PDGFRa, ALPL, and THY1 are consistent with known expression patterns [4, 14] and serve as internal controls that confirm data reliability. Furthermore, SILAC ratios for CD24, CD31, CD71, CD90, and CD140a were consistent with flow cytometry results (Figure 1B,C). In comparison to a report by Rugg-Gunn et al., [4] that used a spectral counting approach to compare membrane proteins in mESC vs XEN, the quantitative ratios are consistent with those previously reported (e.g. ALCAM, ALPL, BST2, GPC3, LAMA1, and PECAM1), but an additional 55 proteins were uniquely identified here, including CD24 (Figure 1C,D). A subset of 51 proteins and their SILAC ratios are summarized in Table 1A, including 25 unique to this study and 26 that were found with ratios consistent with Rugg- Gunn et al. It is noted that the limited number of identifications made in the SILAC comparison of mESC:XEN is attributed to the fact that fewer cells were used for labeling, as a result of practical limitations to expanding the cells in SILAC media.

| A. Subset of 51 cell surface N-glycoproteins identified in the XEN-mESC SILAC comparison. Gene symbol and SILAC ratio are listed | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gene Symbol | Ratio XEN:mESC |

Gene Symbol | Ratio XEN:mESC |

Gene Symbol | Ratio XEN:mESC |

| ABCC1 | 0.27 | GPC3 | mESC only | SLC19A2* | 0.15 |

| ABCC4* | 0.04 | ITFG3 | 0.17 | SLC1A4* | 0.26 |

| ALCAM | mESC only | LNPEP* | mESC only | SLC29A1 | 0.22 |

| ANO6* | 0.13 | LPAR4 * | mESC only | SLC2A1 | 0.19 |

| ATP1B1 | 0.44 | MPZL1 * | 0.27 | SLC39A14* | 0.27 |

| ATP1B3 | 0.27 | NCAM1 | 0.29 | SLC39A6* | 0.38 |

| BCAM | 0.23 | NRADD | 0.44 | SLC3A2 | 0.39 |

| BST2 | mESC only | PDGFRA | XEN only | SLC45A4* | 0.05 |

| CADM1 | 0.08 | PECAM1 | 0.03 | SLC6A6* | mESC only |

| CD24* | 0.55 | PIEZO1 * | 0.61 | SLC7A1* | 0.36 |

| CD276* | 0.19 | PLXNA1 | 0.24 | SLCO4A1* | 0 |

| CLCN2* | 0.35 | PTGFRN | 0.09 | ST14 | 0 |

| CLDND1* | 0.33 | PTK7 | 0.28 | SUSD2* | 0.67 |

| ENPEP | 30.62 | PTPRG | 0.41 | THY1* | mESC only |

| EPHA2 | 0.15 | S1PR2 * | mESC only | TMEM2 | 0.1 |

| F11R | 0.48 | SLC12A4* | 1.05 | TMEM30A* | 0.17 |

| F3 | 72.78 | SLC12A7* | 0.29 | TSPAN31* | mESC only |

| B. Subset of 79 cell surface N-glycoproteins identified in mESC-CM that were not otherwise identified via CSC-Technology analysis of MEF, mESC, miPSC, human fibroblasts, hESC, hiPSC | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AQPEP | CLCA1 | FCGR2B | LRP8 | PTPRC | TINAGL1 |

| ACP2§ | CPXM1 | FMOD | MFAP4 | PXDN§ | TMEM108 |

| ADAMTS9 | CRB2§ | GDF3 | MST1R | SCN2B | TMEM132C |

| ADAMTS15 | CSF2RA | GPR116 | OLR1 | SEMA4G | TMEM59§ |

| ANO1 | DCN | GPR97 | PCDHGA5§ | SIGLEC1 | TRPV2§ |

| ATP8A2 | DKK3 | GPRC5C§ | PCDHGA7 | SIPA1L2 | TSPAN18§ |

| BMP4 | DPCR1 | IGSF10 | PDGFRL | SLC44A4 | UPK1B |

| CACHD1 | DST§ | IL15RA | PKDCC | SLC6A12 | UPK3B |

| CALB1 | ENPP4§ | KCNH3 | PLET1 | SLC6A2 | VNN1 |

| CAR12 | ENTPD3§ | LIPG | PLVAP§ | SLIT3 | WNT11 |

| CAR4 | EPHA3 | LIPH | PROM2 | SOWAHB | WNT8A |

| CD22 | EPHA4 | LOXL2 | PRSS8 | SPPL2B | BC067074 |

| CDH5§ | FAM132A | LPL | PTPRB§ | SULF1 | SLC39A2 |

| CER1 | |||||

560 cell surface N-glycoproteins were identified on mESC-CM and 453 were identified on MEFs, altogether including more >6500 N-glycopeptides representing extracellular-exposed protein domains (Table S2–S3). The CSC-Technology revealed SIRPA. on the surface of mESC-CMs (Figure 2), in contrast to a previous report that identified it on human ESC-CMs but was unable to confirm the presence of SIRPA on mESC-CM using antibody and microarray approaches [6]. Seven additional proteins (CRB2, DSC2, ITGA8, MSLN, NRP1, PRNP, and PTPRB) were identified via the CSC-Technology and flow cytometry analysis is consistent with their presence on the cell surface. When compared to our CSC-Technology analysis of MEFs, mESC, miPSC, human fibroblasts, hESC, and hiPSC [8, 12], 79 proteins were unique to mESC-CM, and of these, 14 were similarly identified in human ESC-CMs previously [5] (Table 1B).

A benefit of the CSC-Technology is its high specificity for authentic cell surface proteins [11, 12]. All SILAC data for selected markers proved consistent with quantitative comparisons achieved by flow cytometry and other published data when available. This partially validated, new dataset should, therefore, be invaluable for future lineage tracing experiments and immunophenotyping assays. It should however be noted that lineage tracing and quantitation based on CSC-Technology data may be affected by alterations in N-glycosylation status, as only N-glycosylated peptides were detected in this study. These cell surface proteomes will continue to evolve as additional discovery strategies are applied, including those not limited to N-glycoproteins [4, 5, 21]. Moreover, there are numerous valuable studies of the N-glycoproteome of other cell types including, but not limited to, pancreatic beta cells, the developing mouse brain cell, rat heart, microglia, and breast cancer [22–26], that are also expected to prove valuable in the long term as efforts continue towards identifying cell surface markers that are lineage, cell type, or disease state specific.

Knowledge of timing and abundance of the proteins present at the cell surface during embryonic development should contribute to a greater understanding of the cellular mechanisms that are involved in lineage and cell fate specification, as cell surface proteins are the gateway for receiving exogenous signals. Specifically relevant for cardiac biology, the discovery of stage-specific markers within the cardiomyogenic lineage will facilitate the analysis of molecular events that regulate critical cell fate decisions at the single cell level during very early development, in a similar way to how immunophenotyping has enabled the systematic study of molecular events regulating hematopoietic stem cell lineage specification. As monoclonal antibodies suitable for immunophenotyping are lacking for a majority of the cell surface proteins identified here, the extensive collection of extracellular epitopes defined here will facilitate the development of monoclonal antibodies that recognize the extracellular domain of surface proteins, allowing their use in live cell sorting schemes.

Statement of Clinical Relevance.

The development of new, informative cell surface markers for the reliable identification and isolation of functionally defined subsets of cells from early developmental stages will advance the use of stem cell technologies for mechanistic developmental studies, including disease modeling and drug discovery.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by NIH 4R00HL094708-03, BD Biosciences Research Grant Award, MCW Research Affairs Committee New Faculty Award, and the Kern foundation (startup funds) at the Medical College of Wisconsin (R.L.G.); an NIH Induced Pluripotent Stem Cell Center/Center for Regenerative Medicine Research Study Award and Research Grants Council of Hong Kong Theme-based Research Scheme T13-706/11 (K.R.B.); NIH (RO1-DK084391) and NYSTEM (A.K.H.). Erin Kropp is a member of the MCW-MSTP which is partially supported by a T32 grant from NIGMS, GM080202. We thank Hope Campbell at the Flow Cytometry Core of the Blood Research Institute of Wisconsin and Dr. Kate Noon, Michael Pereckas, and Xioagang Wu at the MCW Mass Spectrometry Facility for assistance with data collection.

Abbreviations

- mESC

Mouse embryonic stem cells

- mESC-CM

mESC-derived cardiomyocytes

- XEN

extraembryonic endoderm

- MEFs

mouse embryonic fibroblasts

- CSC-Technology

Cell Surface Capture Technology

Reference

- 1.Franco D, Lamers WH, Moorman AF. Patterns of expression in the developing myocardium: towards a morphologically integrated transcriptional model. Cardiovasc Res. 1998;38:25–53. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(97)00321-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Landay AL, Muirhead KA. Procedural guidelines for performing immunophenotyping by flow cytometry. Clin Immunol Immunopathol. 1989;52:48–60. doi: 10.1016/0090-1229(89)90192-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shizuru JA, Negrin RS, Weissman IL. Hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells: clinical and preclinical regeneration of the hematolymphoid system. Annu Rev Med. 2005;56:509–538. doi: 10.1146/annurev.med.54.101601.152334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rugg-Gunn PJ, Cox BJ, Lanner F, Sharma P, et al. Cell-surface proteomics identifies lineage-specific markers of embryo-derived stem cells. Dev Cell. 2012;22:887–901. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2012.01.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Van Hoof D, Dormeyer W, Braam SR, Passier R, et al. Identification of cell surface proteins for antibody-based selection of human embryonic stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes. J Proteome Res. 2010;9:1610–1618. doi: 10.1021/pr901138a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dubois NC, Craft AM, Sharma P, Elliott DA, et al. SIRPA is a specific cell-surface marker for isolating cardiomyocytes derived from human pluripotent stem cells. Nat Biotechnol. 2011;29:1011–1018. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Elliott DA, Braam SR, Koutsis K, Ng ES, et al. NKX2-5(eGFP/w) hESCs for isolation of human cardiac progenitors and cardiomyocytes. Nat Methods. 2011;8:1037–1040. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Boheler KR BS, Chuppa S, Riordon DR, Kropp E, Burridge PW, Wu JC, Wersto RP, Rao S, Wollscheid B, Gundry RL. A Human Pluripotent Stem Cell Surface N-Glycoproteome Resource Reveals New Markers, Extracellular Epitopes, and Drug Targets. doi: 10.1016/j.stemcr.2014.05.002. submitted. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Apweiler R, Hermjakob H, Sharon N. On the frequency of protein glycosylation, as deduced from analysis of the SWISS-PROT database. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1999;1473:4–8. doi: 10.1016/s0304-4165(99)00165-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gundry RL, Raginski K, Tarasova Y, Tchernyshyov I, et al. The mouse C2C12 myoblast cell surface N-linked glycoproteome: identification, glycosite occupancy, and membrane orientation. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2009;8:2555–2569. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M900195-MCP200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wollscheid B, Bausch-Fluck D, Henderson C, O'Brien R, et al. Mass-spectrometric identification and relative quantification of N-linked cell surface glycoproteins. Nat Biotechnol. 2009;27:378–386. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gundry RL, Riordon DR, Tarasova Y, Chuppa S, et al. A Cell Surfaceome Map for Immunophenotyping and Sorting Pluripotent Stem Cells. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2012;11:303–316. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M112.018135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nagy A, Rossant J, Nagy R, Abramow-Newerly W, Roder JC. Derivation of completely cell culture-derived mice from early-passage embryonic stem cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1993;90:8424–8428. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.18.8424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Artus J, Douvaras P, Piliszek A, Isern J, et al. BMP4 signaling directs primitive endoderm-derived XEN cells to an extraembryonic visceral endoderm identity. Dev Biol. 2012;361:245–262. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2011.10.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kunath T, Arnaud D, Uy GD, Okamoto I, et al. Imprinted X-inactivation in extra-embryonic endoderm cell lines from mouse blastocysts. Development. 2005;132:1649–1661. doi: 10.1242/dev.01715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brown K, Legros S, Artus J, Doss MX, et al. A comparative analysis of extra-embryonic endoderm cell lines. PLoS One. 2010;5:e12016. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0012016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Niakan KK, Schrode N, Cho LT, Hadjantonakis AK. Derivation of extraembryonic endoderm stem (XEN) cells from mouse embryos and embryonic stem cells. Nat Protoc. 2013;8:1028–1041. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2013.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ong SE, Blagoev B, Kratchmarova I, Kristensen DB, et al. Stable isotope labeling by amino acids in cell culture, SILAC, as a simple and accurate approach to expression proteomics. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2002;1:376–386. doi: 10.1074/mcp.m200025-mcp200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yamanaka S, Zahanich I, Wersto RP, Boheler KR. Enhanced proliferation of monolayer cultures of embryonic stem (ES) cell-derived cardiomyocytes following acute loss of retinoblastoma. PLoS One. 2008;3:e3896. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0003896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Boheler KR, Joodi RN, Qiao H, Juhasz O, et al. Embryonic stem cell-derived cardiomyocyte heterogeneity and the isolation of immature and committed cells for cardiac remodeling and regeneration. Stem Cells Int. 2011;2011:214203. doi: 10.4061/2011/214203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hofmann A, Gerrits B, Schmidt A, Bock T, et al. Proteomic cell surface phenotyping of differentiating acute myeloid leukemia cells. Blood. 2010;116:e26–e34. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-02-271270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Danzer C, Eckhardt K, Schmidt A, Fankhauser N, et al. Comprehensive description of the N-glycoproteome of mouse pancreatic beta-cells and human islets. J Proteome Res. 2012;11:1598–1608. doi: 10.1021/pr2007895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Palmisano G, Parker BL, Engholm-Keller K, Lendal SE, et al. A novel method for the simultaneous enrichment, identification, and quantification of phosphopeptides and sialylated glycopeptides applied to a temporal profile of mouse brain development. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2012;11:1191–1202. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M112.017509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Parker BL, Palmisano G, Edwards AV, White MY, et al. Quantitative N-linked glycoproteomics of myocardial ischemia and reperfusion injury reveals early remodeling in the extracellular environment. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2011;10:M110 006833. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M110.006833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Deeb SJ, Cox J, Schmidt-Supprian M, Mann M. N-linked glycosylation enrichment for in-depth cell surface proteomics of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma subtypes. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2014;13:240–251. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M113.033977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yen TY, Haste N, Timpe LC, Litsakos-Cheung C, et al. Using a cell line breast cancer progression system to identify biomarker candidates. J Proteomics. 2014;96:173–183. doi: 10.1016/j.jprot.2013.11.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Omasits U, Ahrens CH, Muller S, Wollscheid B. Protter: interactive protein feature visualization and integration with experimental proteomic data. Bioinformatics. 2013 doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btt607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]