Abstract

Background

Discharge beta-blocker prescription after myocardial infarction (MI) is recommended for all eligible patients. Numerous beta-blocker choices are presently available with variable glycometabolic effects, which could be an important consideration in patients with diabetes mellitus (DM). Whether patients with DM preferentially receive beta-blockers with favorable metabolic effects after MI and if this choice is associated with better glycemic control post-discharge is unknown.

Methods

Among patients from 24 US hospitals enrolled in an MI registry (2005–08), we investigated the frequency of “DM-friendly” beta-blocker prescription at discharge by DM status. Beta-blockers were classified as DM-friendly (e.g., carvedilol, labetalol), or non-DM-friendly (e.g., metoprolol, atenolol), based on their effects on glycemic control. Hierarchical, multivariable logistic regression examined the association of DM with DM-friendly beta-blocker use. Among DM patients, we examined the association of DM-friendly beta-blockers with worsened glycemic control at 6 months after MI.

Results

Of 4031 MI patients, 1382 (34%) had DM. Beta-blockers were prescribed at discharge in 93% of patients. DM-friendly beta-blocker use was low regardless of DM status, although patients with DM were more likely to be discharged on a DM-friendly beta-blocker compared with patients without DM (13.5% vs. 10.3%, p=0.003), an association that remained after multivariable adjustment (OR 1.41, 95% CI 1.13–1.77). There was a trend toward a lower risk of worsened glucose control at 6 months in DM patients prescribed DM-friendly vs. non-friendly beta-blockers (RR 0.80, 95% CI 0.60–1.08).

Conclusion

The vast majority of DM patients were prescribed non-DM friendly beta-blockers—a practice that was associated with a trend towards worse glycemic control post-discharge. While in need of further confirmation in larger studies, our findings highlight an opportunity to improve current practices of beta-blockers use in patients with DM.

Keywords: myocardial infarction, beta-blockers, diabetes mellitus, quality of care

Beta-blockers are strongly recommended after an acute myocardial infarction (MI) for all eligible patients to reduce recurrent ischemic events and the risk of cardiac death.1 However, beta-blockers are a heterogenous class of medications with diverse pharmacologic and physiologic properties. Specifically, numerous medications within this class are presently available that vary with regard to their glycometabolic effects2–5, a potentially important consideration in patients with diabetes mellitus (DM). Traditional beta-blockers such as atenolol and metoprolol act primarily by reducing heart rate and myocardial contractility. Reduced cardiac output can induce compensatory peripheral vasoconstriction, leading to increased insulin resistance and a more atherogenic lipid profile.2–4, 6 In contrast, vasodilating beta-blockers such as carvedilol and labetolol have shown neutral or beneficial effects on metabolic parameters in patients with DM and hypertension. 2–5, 7 In head-to-head trials, patients with DM who were treated with vasodilating (vs. traditional) beta-blockers had small but significant decreases in hemoglobin A1c levels, improved insulin sensitivity, lower cholesterol levels, less weight gain, and less progression to microalbuminuria.3, 8–11 However, these findings have not been confirmed in the real-world clinical practice environment.

The concept of “DM-friendly” management of coronary artery disease implies choosing medications that have a favorable or neutral effect on glucose control whenever possible. Given the multiple beta-blockers available—with varying metabolic effects, similar cardioprotective properties12–13, and equal costs14–15—we studied whether providers apply this concept in clinical practice. In addition, we evaluated whether prescription of beta-blockers with unfavorable glycometabolic profile is associated with worse glycemic control post-discharge. Since worsening glycemic control may require intensification of glucose-lowering medications with potential exposure to additional side-effects and costs or if left untreated could adversely affect risk for long-term DM complications, the strategy of selectively treating DM patients with DM-friendly beta-blockers could have important implications in the management of patients after an MI.

METHODS

Study Population and Protocol

Between June 2005 and December 2008, patients from 24 US hospitals were enrolled into the Translational Research Investigating Underlying disparities in acute Myocardial infarction Patients’ Health status (TRIUMPH) study.16 Patients were required to have biomarker evidence of myocardial necrosis and additional evidence supporting the clinical diagnosis of an acute MI (e.g., ischemic signs/symptoms ≥20 minutes or electrocardiographic ST changes) during the initial 24 hours of admission. Baseline data were obtained through chart abstraction and a structured interview by trained research staff within 24 to 72 hours of admission. In addition, consenting patients had fasting blood specimens collected prior to discharge. Approximately 20 mL of fasting blood was drawn from each subject in 3 tubes, which were processed, refrigerated and sent by overnight mail to the core laboratory (Clinical Reference Laboratory, Lenexa, KS) on a daily basis. Blood was analyzed for glucose and HbA1c. Chart data on laboratory values drawn for clinical purposes were also recorded. Each participating hospital obtained Institutional Research Board approval, and all patients provided written informed consent. TRIUMPH was sponsored by a grant from the National Institutes of Health (National Heart, Lung, Blood Institute): SCCOR Grant #P50HL077113-01. This study was sponsored by an investigator-initiated research grant from Gilead Sciences, Foster City, CA. The funding organizations did not play a role in the design and conduct of the study or in the collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data.

Definition of DM and DM-Friendly Beta-Blockers

As this analysis was investigating practice patterns associated with patients with known DM, we defined DM as prevalent DM (i.e., DM by chart abstraction or DM medications at admission [except metformin or thiazolidindiones, which can be used for DM prevention]) or newly-diagnosed DM that was recognized during hospitalization. Newly diagnosed DM was defined as HbA1c≥6.5% by core laboratory or chart assessment. If HbA1c level was missing, DM could be additionally diagnosed as 1) ≥2 fasting blood glucose levels >126 mg/dL or 2) ≥1 fasting blood glucose >126 mg/dL and random blood glucose (at presentation) ≥200 mg/dL. Patients with newly diagnosed DM were considered “recognized” if they were discharged on any DM medications or received DM education during AMI hospitalization. Beta-blockers prescribed at discharge were categorized by their impact on glucose control. Vasodilating beta-blockers (acebutalol, betaxolol, carvedilol, labetolol, nebivolol) were categorized as DM-friendly, and non-vasodilating beta-blockers (all others: e.g., metoprolol, atenolol, propranolol) were categorized as non-DM-friendly. Patients with chart-documented contraindications to beta-blockers at discharge (i.e., systolic blood pressure <90 mmHg, heart rate <50 bpm, or allergy) were excluded from the analyses (n=138).

Outcomes Assessment

Detailed follow-up interviews were attempted on all survivors at 1, 6, and 12 months after AMI. In addition to a report of interval events and an assessment of health status, participants were asked to read the names and doses of their medications from their prescription bottles. Patients could opt for 6-month follow-up by telephone or in-home visit, which allowed for collection of additional laboratory data, which was analyzed for HbA1c at the core laboratory. Worsened glucose control at the 6-month follow-up was defined as either an increase in HbA1c from baseline of ≥0.1% or an intensification of DM meds. Intensification of DM medications was defined, per prior work,17 as any of the following: 1) increase in dose of a medication; 2) addition of a medication; 3) increase in daily basal insulin of 20%; or 4) addition of insulin. If a patient was missing 6-month follow-up medication data, 12-month data was used if available. In addition, we did a second analysis defining worsened glycemic control as an increase in HbA1c from baseline of ≥0.5% or intensification of DM meds.

Statistical Analysis

The frequency of prescription of DM-friendly beta-blockers among patients with and without DM was compared using the chi-square test. We then constructed a hierarchical logistic regression model among patients who were discharged on a beta-blocker to examine the association of DM with use of a DM-friendly beta-blocker, with site included as a random effect to account for clustering of patients within sites. The first model was unadjusted, and a second model included factors other than DM that might impact prescription with a DM-friendly (i.e., vasodilating) beta-blocker: age (vasodilating beta-blockers may cause orthostasis in elderly patients), atrial fibrillation (non-vasodilating beta-blockers may be superior for rate controlling atrial arrhythmias), chronic lung disease (vasodilating beta-blockers may cause increased wheezing), left ventricular dysfunction and a history of heart failure (vasodilating beta-blockers are considered by many to be better for patients with heart failure18), self-reported avoidance of medications due to costs (vasodilating beta-blockers were not available as a generic medication for the first 2 years of TRIUMPH), heart rate (non-vasodilating beta-blockers lower heart rate more than vasodilating beta-blockers), and systolic blood pressure at discharge (vasodilating beta-blockers lower blood pressure more than non-vasodilating beta-blockers). We also performed a sensitivity analysis excluding patients who might not be considered candidates for vasodilating beta-blockers: patients with atrial fibrillation, chronic lung disease, or systolic blood pressure at discharge of <110 mmHg.

As practice patterns may have changed due to changes in medication availability over time (e.g., metoprolol succinate became generic in 2006; carvedilol became generic in 2007, and nebivolol was introduced in 2007), we examined the association of time with the prescription of DM-friendly beta-blockers by adding time (as quarter of year) to the multivariable model. To examine if patients with DM were more likely to be treated with DM-friendly beta-blockers over time, we also examined the interaction of DM*time. Spline terms were considered for all continuous variables, and all models were hierarchical, with hospital included as a random effect to adjust for patient clustering by site.

Among patients with DM discharged on a beta-blocker, we examined the association of DM-friendly beta-blocker at discharge with glycemic control over the following 6 months using hierarchical modified Poisson regression, adjusted for clinical and demographic factors (age, left ventricular dysfunction, history of heart failure, chronic lung disease, self-reported avoidance of medical care due to costs, and baseline HbA1c). All analyses were conducted using SAS v9.2 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC), and statistical significance was determined by a 2-sided p-value of <0.05.

RESULTS

Study Population

Among 4031 patients who were discharged alive after acute MI and did not have a contraindication to beta-blocker therapy, 34% (n=1382) had DM. The mean age of the overall population was 59 years, 33% were women, and 32% nonwhite. The baseline demographic and clinical characteristics by presence of DM are shown in Table 1. Patients with DM (vs. no DM) were more likely to be older, female, nonwhite, and lower socioeconomic status. DM patients had more cardiac and non-cardiac comorbidities, were less likely to present with an ST-elevation MI, and had longer length of stays than patients without DM.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics by diabetes status

| Diabetes n=1382 |

No Diabetes n=2649 |

P-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sociodemographics | |||

| Age (y) | 60.2±11.6 | 58.3±12.7 | <0.001 |

| Male | 40.8% | 28.8% | <0.001 |

| White race | 58.8% | 72.3% | <0.001 |

| High school or greater education | 74.6% | 81.8% | <0.001 |

| Insurance coverage for medications | 71.4% | 73.3% | 0.195 |

| Avoids medical care due to cost | 28.8% | 24.2% | 0.002 |

| Clinical characteristics | |||

| Hypertension | 82.8% | 58.4% | <0.001 |

| Current smoking | 29.2% | 42.8% | <0.001 |

| Depressive symptoms | 20.1% | 13.5% | <0.001 |

| Chronic lung disease | 8.0% | 6.3% | 0.039 |

| Chronic kidney disease (GFR <60) | 35.8% | 19.0% | <0.001 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 31.6±7.2 | 28.6±5.8 | <0.001 |

| History of PCI | 24.1% | 17.4% | <0.001 |

| History of CABG | 17.0% | 8.1% | <0.001 |

| Prior heart failure | 14.5% | 5.3% | <0.001 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 5.8% | 4.3% | 0.031 |

| Acute presentation and treatment | |||

| ST-elevations on arrival | 32.8% | 49.5% | <0.001 |

| LV systolic dysfunction | 21.0% | 17.1% | 0.002 |

| Heart rate (bpm) | 74.1±12.3 | 72.4±11.9 | <0.001 |

| Systolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 124.0±20.6 | 117.6±18.1 | <0.001 |

| GRACE discharge score | 106.6±29.9 | 96.8±29.7 | <0.001 |

| In-hospital PCI | 56.3% | 70.9% | <0.001 |

| In-hospital CABG | 10.8% | 8.8% | 0.05 |

| Length of stay (days) | 6.4±7.4 | 5.0±5.2 | <0.001 |

| Aspirin at discharge | 92.5% | 95.7% | <0.001 |

| ACE Inhibitor/ARB at discharge | 76.6% | 74.3% | 0.104 |

| Statin at discharge | 87.0% | 89.4% | 0.023 |

DM-Friendly Beta-blocker Prescription

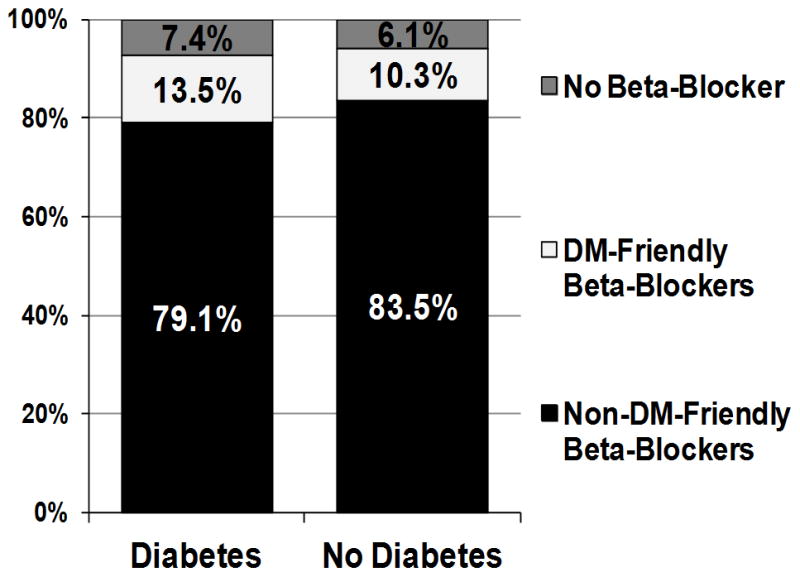

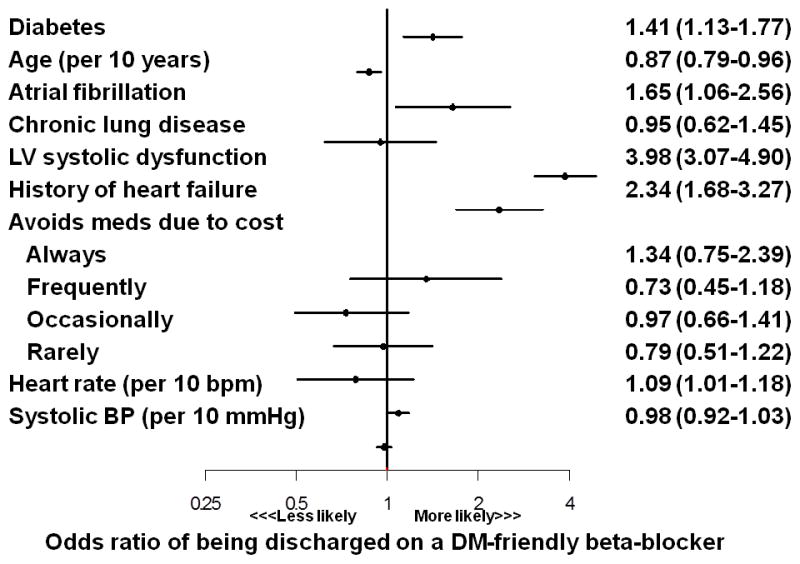

Overall, 93.5% of patients were discharged after acute MI on a beta-blocker, with no significant difference by DM status (Figure 1). Rates of DM-friendly beta-blocker prescription were low regardless of DM status, although a larger proportion of patients with DM were discharged on a DM-friendly beta-blocker compared with patients without DM (13.5% vs. 10.3%, p=0.003). Among patients discharged on a beta-blocker, those with DM were more likely to be prescribed a DM-friendly beta-blocker in unadjusted analysis (OR 1.55, 95% CI 1.26–1.90), as well as after adjustment for patient factors that could influence beta-blocker se lection (OR 1.41, 95% CI 1.13–1.77; Figure 2). However, the factors that most influenced choice of beta-blocker were the presence of left ventricular systolic dysfunction (OR 3.88, 95% CI 3.07–4.90) and a clinical history of heart failure (OR 2.34, 95% CI 1.68–3.27).

Figure 1. Breakdown of beta-blockers prescribed at hospital discharge by diabetes status.

DM-friendly beta-blockers (e.g., carvedilol, labetolol). Non-DM-friendly beta-blockers (e.g., metoprolol, atenolol).

Figure 2.

Association of patient factors with prescription of DM-friendly beta-blocker after acute myocardial infarction

In a sensitivity analysis excluding 1603 patients who might have been considered ineligible for vasodilating beta-blockers at the time of discharge (patients with atrial fibrillation, chronic lung disease, or systolic blood pressure <110 mmHg), the results were essentially unchanged, with a low percentage of patients being discharged on DM-friendly beta-blockers and a small difference between the rates among patients with and without DM (12.1% vs. 8.5%, p=0.004). Patients with DM remained more likely to be prescribed DM-friendly beta-blockers (OR 1.44, 95% CI 1.06–1.95) in the hierarchical multivariable model.

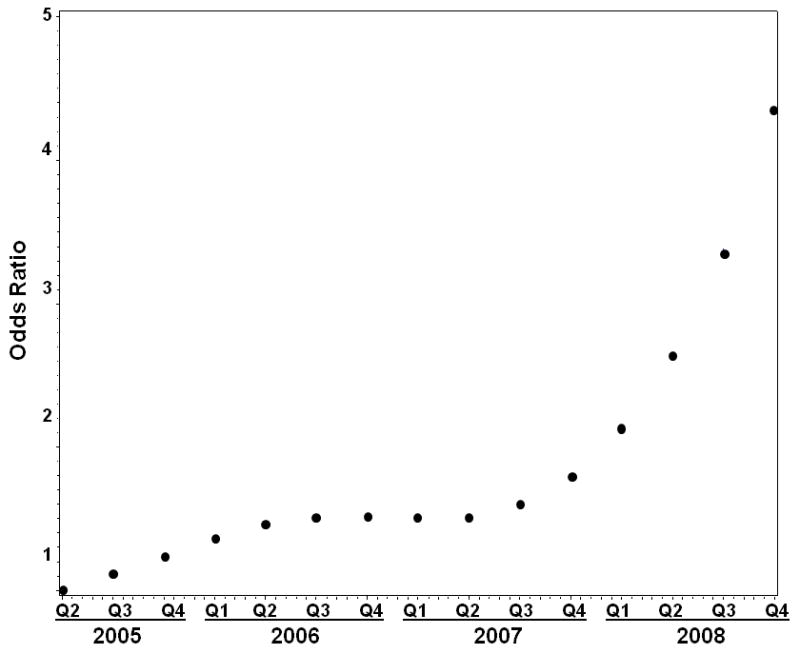

DM-Friendly Beta-blocker Prescription Over Time

As TRIUMPH enrolled patients from June 2005 and December 2008 and several commonly used beta-blockers were introduced or became generic during that time period, we examined whether time was associated with DM-friendly beta-blocker prescriptions. In the multivariable model, time (analyzed as quarter years) was significantly associated with DM-friendly beta-blocker use in a non-linear manner, with a rapid increase in likelihood of prescription during 2008 (Figure 4). This time period corresponded to the point when carvedilol (which represented 94% of all DM-friendly beta-blocker prescriptions) became available as a generic medication. However, while overall prescription of DM-friendly beta-blockers increased over time during TRIUMPH, the interaction of DM*time was not significant (p=0.33), indicating that the likelihood of being treated with DM-friendly beta-blockers among patients with vs. without DM did not increase over time.

Outcomes

We examined the association of DM-friendly beta-blockers on worsened glycemic control among 609 patients with DM with follow-up data available. At baseline, there was no difference in HbA1c levels between groups (DM-friendly vs. non-DM-friendly: 8.1% vs. 8.0%, p=0.68). At 6 months, patients discharged on DM-friendly beta-blockers had a non-significant trend toward better glucose control (worsened glucose control: 31.3% vs. 39.2%, p=0.17), with similar trends in each component of glucose control (DM medications intensified: 24.7% vs. 32.0%, p=0.21; HbA1c increased: 25.0% vs. 37.7%, p=0.16). In the multivariable model, a DM-friendly beta-blocker prescription at discharge was associated with a trend toward a lower risk of worsened glucose control at 6 months (RR 0.80, 95% CI 0.60–1.08). In the sensitivity analysis using a cut-point of ≥0.5% increase in HbA1c to indicate worsened glycemic control, the two groups were more similar (DM-friendly vs. not: 28.9% vs. 34.4%, p=0.33).

DISCUSSION

In a large, multicenter MI registry, we found that DM was associated with a modest increase in the use of DM-friendly beta-blockers at discharge. However, the vast majority of DM patients were still prescribed beta-blockers with potentially adverse glycometabolic effects. While the overall prescription of DM-friendly beta-blockers increased over time, choice of beta-blocker at discharge appeared to be driven more by other factors, such as the presence of left ventricular dysfunction and local practice patterns, rather than the presence of DM. Furthermore, DM patients prescribed a DM-friendly beta-blocker at discharge were less likely to have worsened glucose control at follow-up versus those prescribed a non-DM-friendly beta-blocker. These results suggest that there may be clinically important differences in the metabolic effects of different beta-blockers. Provided that these differences in glucose management (which may in turn impact patients’ symptoms, quality of life, and healthcare costs) are confirmed in future studies, there are significant opportunities to improve current practices of beta-blocker use in patients with DM.

Drug-disease interactions—where a medication to treat one condition can worsen a pre-existing condition—are common and may cause harm.19 Due to their potential adverse impact on glycemic status and insulin sensitivity, conventional beta-blockers are not recommended for the treatment of hypertension in patients with DM, unless the blood pressure remains uncontrolled on other agents.20–24 For example, the American Society of Hypertension recommends only vasodilating beta-blockers as second- or third-line treatment for patients with DM and hypertension due to their neutral effects on glycemic control and increase insulin sensitivity.20

However, in the post-MI period, beta-blockers reduce mortality and recurrent nonfatal MI25, even among patients with DM26, and are therefore recommended in all patients after MI, regardless of DM status.1 Although certain clinical factors may contribute to the appropriate selection of a non-DM-friendly beta-blocker in a post-MI patient with DM (e.g., atrial or ventricular arrhythmias, marginal blood pressures, orthostasis), in the absence of such factors it seems logical that post-MI patients with DM would be treated with a beta-blocker that exhibits more beneficial glycometabolic effects.

Prior head-to-head studies of DM-friendly vs. non-DM-friendly beta-blockers in patients with DM have been limited mostly to surrogate outcomes, such as differences in serum lipids and HbA1c, and as such, it is not known if the discrepant metabolic effects of the different classes of beta-blockers translate into differences in long-term, clinically meaningful outcomes. In a small 24-week randomized trial of carvedilol vs. atenolol in patients with DM and hypertension, carvedilol resulted in decreases in fasting plasma glucose, insulin, and triglyceride levels and increases in high-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels compared with adverse changes in each of these levels with atenolol.9 In a second large, multicenter 35-week randomized trial of carvedilol vs. metoprolol in patients with DM and hypertension, treatment with carvedilol resulted in small but significant differences in hemoglobin A1c levels (0.13% lower with carvedilol, p=0.004), improved insulin sensitivity (7.2% lower with carvedilol, p=0.004), and lower cholesterol and triglyceride levels compared with adverse changes in each of these levels with metoprolol. In addition, there was more weight gain (1 kg more with metoprolol, p<0.001) and a greater progression to microalbuminuria in the metoprolol group compared with those randomized to carvedilol (10.3% vs. 6.4%, p=0.04).3 Furthermore, in addition to the changes in lipid levels, more patients in the metoprolol group had initiation of statin therapy or their statin dose increased compared with those in the carvedilol group (32% vs. 11%, p=0.04).27 Similar results have also been observed in 2 small trials comparing the metabolic effects of nebivolol with atenolol8 and metoprolol.11 In a secondary analysis of the large, multinational Carvedilol Or Metoprolol European Trial, patients without DM who were randomized to carvedilol were less likely to develop DM compared with those randomized to metoprolol (HR=0.78, p=0.048).10 A recent meta-analysis of 644 acute MI patients (not limited to patients with DM) suggested a reduction in all-cause mortality in patients randomized to carvedilol vs. metoprolol or atenolol.18 However, the overall result was primarily driven by a single trial that enrolled MI patients with left ventricular dysfunction28, which limits the generalizability of this study.

Although long-term outcomes studies comparing DM-friendly beta-blockers with non-DM-friendly beta-blockers after MI would be clinically valuable, particularly among patients with DM, such studies are unlikely to be conducted. We found in that patients with DM who were discharged on non-DM-friendly beta-blockers had a trend toward worsened glycemic control after discharge, which has a well-established relationship with long-term microvascular complications.29–31 Although confirmation in a larger study is needed, our results suggest that the metabolic differences between different beta-blockers may have clinically important implications. As such, treating DM patients with DM-friendly beta-blockers post-MI seems to be the optimal strategy, particularly since there is no downside in terms of their cardioprotective effects12–13 or associated costs (e.g., carvedilol is available as a generic medication and as a $4/month drug at many pharmacies14–15).

The results of our study should be considered in light of the following potential limitations. There are many important clinical distinctions between the classes of beta-blockers other than their glycometabolic effects that might lead a physician to choose one beta-blocker over another (e.g., bradycardia, orthostasis, bronchospastic lung disease, etc.). While we accounted for these by multivariable adjustment and in the sensitivity analysis, it is possible that some patients were being treated with a particular beta-blocker for a clinically relevant reason for which we were unable to adjust (e.g., migraines, portal hypertension, erectile dysfunction). However, it is unlikely that such patients represented more than a small fraction of our cohort. In addition, not all beta-blockers have been studied in the post-MI population, with the seminal trials using propranolol32, atenolol33, metoprolol34, and carvedilol35. In head-to-head trials, carvedilol has been at least as effective as metoprolol in terms of anti-ischemic effects.12–13 While there is no inherent reason to believe that medications such as labetolol or nebivolol would not be effective in reducing the risk of adverse ischemic events after an MI, this lack of outcomes data may have affected the practice patterns of some physicians; nevertheless, these medications constituted only a small fraction of DM-friendly beta blockers in our study (6%). Further qualitative research would be informative to better understand why physicians choose one beta-blocker over another after an MI. Second, the glycemic effects of all beta-blockers have not been formally studied. Preclinical data suggests that the mechanism by which cardvedilol and nebivolol achieve neutral glycemic effects would extend to the other vasodilatory beta-blockers, but the glycemic effects of the beta-blockers such as labetolol, which has higher alpha-blocking activity compared with carvedilol, have only been shown in small studies.36 Finally, we only examined the association of DM with the use of DM-friendly beta-blockers after AMI. However, there is also evidence that DM-friendly beta-blockers also reduce progression to DM among patients with impaired fasting glucose and pre-DM.4, 10 As patients with pre-DM represent ~1/3 of patients with AMI, it is possible that DM-friendly beta-blockers could be beneficial in these patients as well. However, we decided to limit our analysis to the group of patients in which the benefits of these medications are better established.

In conclusion, in a large, multicenter study of MI patients, we found that the vast majority of DM patients were prescribed beta-blockers with potentially adverse glycometabolic effects—a practice that was associated with a trend towards worse glycemic control post-discharge. Although in need of further confirmation in larger studies, our findings highlight a potential opportunity to improve current prescription practices of beta-blockers in patients with DM after an AMI.

Figure 3. Odds of prescription of DM-friendly beta-blocker among all patients at discharge over time.

Reference is 2nd quarter of 2005.

Footnotes

Disclosures: SVA: Research grants: Significant-Genentech, Eli Lilly, Sanofi-Aventis, Gilead; JAS: Research grants: NHLBI, AHA, ACCF, Gilead, Lilly, EvaHeart, Amorcyte. Consultation: United Healthcare, Genentech, Amgen. DKM: Consultant : Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Daiichi Sankyo, Pfizer, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Regeneron, Genentech, F Hoffmann-La Roche, Merck, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Tethys Biosciences, AstraZeneca, Orexigen, Eli Lilly, and Takeda. MK: Research grants: Significant-American Heart Association, Genentech, Sanofi-Aventis, Gilead, Eisai, Medtronic Minimed, Glumetrics, Maquet; Consultant honoraria: Modest-Genentech, Gilead, F Hoffmann LaRoche, Medtronic Minimed, AstraZeneca, Abbvie, Regeneron. The other authors report no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Anderson JL, Adams CD, Antman EM, Bridges CR, Califf RM, Casey DE, Jr, et al. ACC/AHA 2007 guidelines for the management of patients with unstable angina/non ST-elevation myocardial infarction: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Writing Committee to Revise the 2002 Guidelines for the Management of Patients With Unstable Angina/Non ST-Elevation Myocardial Infarction): developed in collaboration with the American College of Emergency Physicians, the Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, and the Society of Thoracic Surgeons: endorsed by the American Association of Cardiovascular and Pulmonary Rehabilitation and the Society for Academic Emergency Medicine. Circulation. 2007;116(7):e148–304. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.181940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Le Brocq M, Leslie SJ, Milliken P, Megson IL. Endothelial dysfunction: from molecular mechanisms to measurement, clinical implications, and therapeutic opportunities. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2008;10(9):1631–74. doi: 10.1089/ars.2007.2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bakris GL, Fonseca V, Katholi RE, McGill JB, Messerli FH, Phillips RA, et al. Metabolic effects of carvedilol vs metoprolol in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus and hypertension: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2004;292(18):2227–36. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.18.2227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bangalore S, Parkar S, Grossman E, Messerli FH. A meta-analysis of 94,492 patients with hypertension treated with beta blockers to determine the risk of new-onset diabetes mellitus. Am J Cardiol. 2007;100(8):1254–62. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2007.05.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schmidt AC, Graf C, Brixius K, Scholze J. Blood pressure-lowering effect of nebivolol in hypertensive patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: the YESTONO study. Clin Drug Investig. 2007;27(12):841–9. doi: 10.2165/00044011-200727120-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dornhorst A, Powell SH, Pensky J. Aggravation by propranolol of hyperglycaemic effect of hydrochlorothiazide in type II diabetics without alteration of insulin secretion. Lancet. 1985;1(8421):123–6. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(85)91900-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Van Bortel LM. Efficacy, tolerability and safety of nebivolol in patients with hypertension and diabetes: a post-marketing surveillance study. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2010;14(9):749–58. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Badar VA, Hiware SK, Shrivastava MP, Thawani VR, Hardas MM. Comparison of nebivolol and atenolol on blood pressure, blood sugar, and lipid profile in patients of essential hypertension. Indian J Pharmacol. 2011;43(4):437–40. doi: 10.4103/0253-7613.83117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Giugliano D, Acampora R, Marfella R, De Rosa N, Ziccardi P, Ragone R, et al. Metabolic and cardiovascular effects of carvedilol and atenolol in non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus and hypertension. A randomized, controlled trial. Ann Intern Med. 1997;126(12):955–9. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-126-12-199706150-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Torp-Pedersen C, Metra M, Charlesworth A, Spark P, Lukas MA, Poole-Wilson PA, et al. Effects of metoprolol and carvedilol on pre-existing and new onset diabetes in patients with chronic heart failure: data from the Carvedilol Or Metoprolol European Trial (COMET) Heart. 2007;93(8):968–73. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2006.092379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Celik T, Iyisoy A, Kursaklioglu H, Kardesoglu E, Kilic S, Turhan H, et al. Comparative effects of nebivolol and metoprolol on oxidative stress, insulin resistance, plasma adiponectin and soluble P-selectin levels in hypertensive patients. J Hypertens. 2006;24(3):591–6. doi: 10.1097/01.hjh.0000209993.26057.de. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bonnemeier H, Ortak J, Tolg R, Witt M, Schmidt J, Wiegand UK, et al. Carvedilol versus metoprolol in the acute phase of myocardial infarction. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2005;28 (Suppl 1):S222–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8159.2005.00014.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tolg R, Witt M, Schwarz B, Kurz T, Kurowski V, Hartmann F, et al. Comparison of carvedilol and metoprolol in patients with acute myocardial infarction undergoing primary coronary intervention--the PASSAT Study. Clin Res Cardiol. 2006;95(1):31–41. doi: 10.1007/s00392-006-0317-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Walmart.Com. Retail Prescription Program Drug List [Google Scholar]

- 15.Target.com. Target: Pharmacy: $4 Generics by Condition [Google Scholar]

- 16.Arnold SV, Chan PS, Jones PG, Decker C, Buchanan DM, Krumholz HM, et al. Translational Research Investigating Underlying Disparities in Acute Myocardial Infarction Patients’ Health Status (TRIUMPH): Design and Rationale of a Prospective Multicenter Registry. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2011;4(4):467–476. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.110.960468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stolker JM, Spertus JA, McGuire DK, Lind M, Tang F, Jones PG, et al. Relationship between glycosylated hemoglobin assessment and glucose therapy intensification in patients with diabetes hospitalized for acute myocardial infarction. Diabetes Care. 2012;35(5):991–3. doi: 10.2337/dc11-1839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.DiNicolantonio JJ, Lavie CJ, Fares H, Menezes AR, O’Keefe JH. Meta-analysis of carvedilol versus beta 1 selective beta-blockers (atenolol, bisoprolol, metoprolol, and nebivolol) Am J Cardiol. 2013;111(5):765–9. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2012.11.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lindblad CI, Hanlon JT, Gross CR, Sloane RJ, Pieper CF, Hajjar ER, et al. Clinically important drug-disease interactions and their prevalence in older adults. Clin Ther. 2006;28(8):1133–43. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2006.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bakris GL, Sowers JR. ASH position paper: treatment of hypertension in patients with diabetes-an update. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich) 2008;10(9):707–13. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-7176.2008.00012.x. discussion 714–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Leonetti G, Egan CG. Use of carvedilol in hypertension: an update. Vasc Health Risk Manag. 2012;8:307–22. doi: 10.2147/VHRM.S31578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.DiNicolantonio JJ, Hackam DG. Carvedilol: a third-generation beta-blocker should be a first-choice beta-blocker. Expert Rev Cardiovasc Ther. 2012;10(1):13–25. doi: 10.1586/erc.11.166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bangalore S, Messerli FH, Kostis JB, Pepine CJ. Cardiovascular protection using beta-blockers: a critical review of the evidence. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;50(7):563–72. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.04.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Williams B, Poulter NR, Brown MJ, Davis M, McInnes GT, Potter JF, et al. Guidelines for management of hypertension: report of the fourth working party of the British Hypertension Society, 2004-BHS IV. J Hum Hypertens. 2004;18(3):139–85. doi: 10.1038/sj.jhh.1001683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Freemantle N, Cleland J, Young P, Mason J, Harrison J. beta Blockade after myocardial infarction: systematic review and meta regression analysis. BMJ. 1999;318(7200):1730–7. doi: 10.1136/bmj.318.7200.1730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kjekshus J, Gilpin E, Cali G, Blackey AR, Henning H, Ross J., Jr Diabetic patients and beta-blockers after acute myocardial infarction. Eur Heart J. 1990;11(1):43–50. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.eurheartj.a059591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bell DS, Bakris GL, McGill JB. Comparison of carvedilol and metoprolol on serum lipid concentration in diabetic hypertensive patients. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2009;11(3):234–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1326.2008.00927.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mrdovic IB, Savic LZ, Perunicic JP, Asanin MR, Lasica RM, Jelena MM, et al. Randomized active-controlled study comparing effects of treatment with carvedilol versus metoprolol in patients with left ventricular dysfunction after acute myocardial infarction. Am Heart J. 2007;154(1):116–22. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2007.03.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Khaw KT, Wareham N, Luben R, Bingham S, Oakes S, Welch A, et al. Glycated haemoglobin, diabetes, and mortality in men in Norfolk cohort of european prospective investigation of cancer and nutrition (EPIC-Norfolk) BMJ. 2001;322(7277):15–8. doi: 10.1136/bmj.322.7277.15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Berton G, Cordiano R, Palmieri R, Cucchini F, De Toni R, Palatini P. Microalbuminuria during acute myocardial infarction; a strong predictor for 1-year mortality. Eur Heart J. 2001;22(16):1466–75. doi: 10.1053/euhj.2000.2582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kennedy LM, Dickstein K, Anker SD, James M, Cook TJ, Kristianson K, et al. Weight-change as a prognostic marker in 12 550 patients following acute myocardial infarction or with stable coronary artery disease. Eur Heart J. 2006;27(23):2755–62. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehl182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.A randomized trial of propranolol in patients with acute myocardial infarction. I. Mortality results. JAMA. 1982;247(12):1707–14. doi: 10.1001/jama.1982.03320370021023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Randomised trial of intravenous atenolol among 16 027 cases of suspected acute myocardial infarction: ISIS-1. First International Study of Infarct Survival Collaborative Group. Lancet. 1986;2(8498):57–66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.The Lopressor Intervention Trial: multicentre study of metoprolol in survivors of acute myocardial infarction. Lopressor Intervention Trial Research Group. Eur Heart J. 1987;8(10):1056–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dargie HJ. Effect of carvedilol on outcome after myocardial infarction in patients with left-ventricular dysfunction: the CAPRICORN randomised trial. Lancet. 2001;357(9266):1385–90. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(00)04560-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ohman KP, Weiner L, von Schenck H, Karlberg BE. Antihypertensive and metabolic effects of nifedipine and labetalol alone and in combination in primary hypertension. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 1985;29(2):149–54. doi: 10.1007/BF00547413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]