Abstract

Health communication and health information technology influence the ways in which health care professionals and the public seek, use, and comprehend health information. The Health Information National Trends Survey (HINTS) program was developed to assess the effect of health communication and health information technology on health-related attitudes, knowledge, and behavior. HINTS has fielded 3 national data collections with the fourth (HINTS 4) currently underway. Throughout this time, the Journal of Health Communication has been a dedicated partner in disseminating research based on HINTS data. Thus, the authors thought it the perfect venue to provide an historical overview of the HINTS program and to introduce the most recent HINTS data collection effort. This commentary describes the rationale for and structure of HINTS 4, summarizes the methodological approach applied in Cycle 1 of HINTS 4, describes the timeline for the HINTS 4 data collection, and identifies priorities for research using HINTS 4 data.

Background

Health communication and health information technology play an increasingly central role in health care delivery and public health (Hesse, Moser, Rutten, & Kreps, 2006; Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, 2010; Viswanath, 2005). Processes of health communication and supportive health information technology infrastructure shape the ways in which health care professionals and the public seek, use, and understand health information (Hesse et al., 2006; Hesse et al., 2005). Information seeking and health communication have a significant effect on individuals' health decisions, health-related behavior, and health outcomes (Hesse et al., 2006; Hesse et al., 2005; Nelson et al., 2004; Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, 2010).

The Health Information National Trends Survey (HINTS) program was developed to track changes in the rapidly evolving health communication and information technology landscape and to assess the effect of health communication and health information technology on health outcomes, health care quality, and health disparities (Nelson et al., 2004). HINTS is a nationally representative survey of the U.S. noninstitutionalized adult population that collects data on the American public's need for, access to, and use of health-related information and health-related behaviors, perceptions, and knowledge (Hesse et al., 2006; Nelson et al., 2004). Researchers use HINTS data to explore how the U.S. public uses different communication channels, including the Internet, to obtain health information and to gauge the public's attitudes regarding and perceptions of health-relevant topics (e.g., smoking, cancer screening). Program planners use HINTS data to identify barriers to health information usage across populations, and to create more effective communication strategies. Last, social scientists use the data to refine their theories of health communication in the information age and to inform recommendations for theory-driven interventions aimed at improving population health.

In recognition of the effect of health communication on health outcomes, Healthy People 2020 identified a series of health communication and health information technology objectives to (a) improve population health outcomes and health care quality and (b) reduce health disparities through use of effective health communication strategies and health information technology (Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, 2010). Specific objectives include the following: improving shared decision-making processes between patients and health care professionals; providing self-management tools and resources to support health; developing social support networks around health concerns; delivering actionable and relevant health information; improving meaningful use of health information technology and fostering the greater exchange of health information among health care and public health professionals; enabling informed action during public health emergencies; improving the public's health literacy; improving outreach to culturally diverse populations; and increasing access to the Internet and mobile devices (Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, 2010).

The alignment of Healthy People 2020 health communication objectives and measurement objectives of HINTS made for a ready partnership for tracking health communication and health information technology in the population. Thus, Healthy People 2020 designated HINTS as the data source for tracking a number of their health communication and health information technology objectives (Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, 2010) using items from HINTS to track public access to the Internet, use of electronic personal health management tools, and use of mobile devices.

Overview

HINTS has fielded three national data collections with the fourth (HINTS 4) currently underway. Throughout the past decade, the Journal of Health Communication has been a committed partner in our efforts to disseminate research based on HINTS data. Two special issues of the journal have been dedicated to summarizing key findings derived from HINTS data resources showcasing a breadth of research topics including disparities in health communication (Geiger et al., 2010; Kobetz et al., 2010; Langford, Resnicow, & An, 2010; Nguyen & Bellamy, 2006; Oh et al., 2010; Tortolero-Luna et al., 2010; Vanderpool & Huang, 2010; Viswanath et al., 2006; Zhao, 2010), health communication in health care delivery (Chou, Wang, Finney Rutten, Moser, & Hesse, 2010; Ciampa, Osborn, Peterson, & Rothman, 2010; Hou & Shim, 2010; Ling, Klein, & Dang, 2006; Marks, Ok, Joung, & Allegrante, 2010; Rutten, Augustson, & Wanke, 2006; Shim, Kelly, & Hornik, 2006; Smith, Wolf, & von Wagner, 2010), health information seeking (Hesse et al., 2006; Rutten, Squiers, & Hesse, 2006; Squiers et al., 2006), cancer prevention behavior and health communication (Ford, Coups, & Hay, 2006; Ling et al., 2006; Shim et al., 2006), perceptions of cancer risk (Ford et al., 2006; Han, Moser, & Klein, 2006; Zajac, Klein, & McCaul, 2006), mediated health communication (Clayman, Manganello, Viswanath, Hesse, & Arora, 2010; Kaufman, Augustson, Davis, & Finney Rutten, 2010; Kealey & Berkman, 2010; Koch-Weser, Bradshaw, Gualtieri, & Gallagher, 2010; Kontos, Emmons, Puleo, & Viswanath, 2010) and health survey methodology (McBride & Cantor, 2010; Peytchev, Ridenhour, & Krotki, 2010). In addition to the special issues, the journal has published several other peer-reviewed articles focused on HINTS analyses further demonstrating their commitment to this important program of research (Cheong, Feeley, & Servoss, 2007; Hesse et al., 2011; Koshiol, Rutten, Moser, & Hesse, 2009; Manganello & Clayman, 2011; McQueen, Vernon, Meissner, & Rakowski, 2008; Niederdeppe, Frosch, & Hornik, 2008; Ok, Marks, & Allegrante, 2008; Rains, 2007; Thompson et al., 2011; Ye, 2011). Recognizing that the HINTS community of researchers and results users has come to rely upon the Journal of Health Communication as the go-to journal for HINTS research, we thought it the perfect venue to provide an historical overview of the HINTS program and to introduce the most recent HINTS data collection effort. The purpose of this commentary is thus to describe the rationale for and structure of the current HINTS effort (HINTS 4) and to summarize the methodological approach applied in Cycle 1 of HINTS 4. We also describe the timeline for the HINTS 4 data collection efforts and resultant public data resources. Last, we summarize priorities for research using HINTS 4 data.

Brief History of HINTS Data Collection Efforts

HINTS was first administered in 2002–2003 (HINTS 2003) as a cross-sectional survey of the U.S. civilian, noninstitutionalized, adult population (Nelson et al., 2004). HINTS 2003 used a probability-based sample, drawing on random digit dialing (RDD) landline telephone numbers as the sampling frame of highest penetration at that time. Data were collected from 6,369 respondents. HINTS 2003 yielded a response rate of 33%, which was lower than anticipated but consistent with declining response rates for RDD studies in the field of survey research overall (Singer, Van Hoewyk, & Maher, 2000).

To address diminishing response rates, the second cycle of HINTS, conducted in 2005 (HINTS 2005), included embedded methodological experiments to compare response rates to surveys collected by landline telephone with surveys collected through the Internet. In addition, this field study explored the effect of varying levels of incentives on response rates. The overall response rate for HINTS 2005 was 24% (n = 5,586). Although decreasing telephone response rates have been experienced across the survey industry (Curtin, Presser, & Singer, 2005; Dillman, 2000), it had been expected that providing respondents with an Internet alternative, a monetary incentive for nonresponders, and making nonresponse conversion a priority would reduce the effect of declining response rates. However, this did not prove to be the case and the Internet arm was discontinued.

HINTS 2007–2008, conducted in 2008, included additional priorities: to provide guidance for strategies to increase response rates and to undertake a thorough assessment of the reasons for nonresponse, including the development of a mixed mode design (using a telephone and self-administered survey completed by mail) for survey administration and formative research on the survey mailing materials (Cantor et al., 2009). A series of focus groups were conducted on the letters sent to respondents and the cover of the mail questionnaire. The goal of the focus groups was to find the best way to motivate respondents to complete the survey. The mixed-mode data collection design employed dual sampling frames, both RDD and addressed-based sampling (ABS) frames, and provided a nationally representative sample in each. An RDD telephone survey and a mail questionnaire were implemented with telephone follow up of a subsample of the nonrespondents (Cantor et al., 2009). RDD respondents received the full questionnaire administered via computer-assisted telephone interview (CATI). Data were collected from 4,092 respondents via CATI and 3,582 respondents via mail for a total of 7,674 respondents. HINTS 2007–2008 results showed that the CATI interview had an overall response rate of 24% while the mailed survey had an overall response rate of 31% (Cantor et al., 2009).

HINTS 4

HINTS 4 draws upon the lessons learned from prior iterations of HINTS while employing some new strategies (Link, 2005). On the basis of the higher response rates for the mail survey (over the RDD survey) in HINTS 2007–2008, a single-mode mail survey was implemented for HINTS 4. HINTS 4 involves four separate data collection cycles over a 3-year field period that began late in 2011 and will extend into 2014.

Instrument Development

The HINTS program has always relied on the participation of a wide variety of researchers and practitioners to develop items for the survey instruments. This process has historically involved multiple meetings and exchanges among content experts to solicit survey items across a variety of domains relevant to health communication. One drawback to this approach is that it lacks transparency, is burdensome, time-consuming, precludes input from a wide range of stakeholders, and is inefficient. For HINTS 4, the National Cancer Institute developed an online application called HINTS-GEM to enable technology-mediated social participation in survey development. Moser, Beckjord, Finney Rutten, Blake, and Hesse (2012) describe in further detail the HINTS-GEM tool, its implementation, and the outcomes regarding survey development in the accompanying HINTS article published in this issue. In addition, HINTS 4 development has involved multiple intragovernmental collaborations, with content contributed by the Food and Drug Administration focused on medical product safety and the Office of the National Coordinator focused on security and privacy of electronic health information exchange.

Data Collection Structure and Timeline

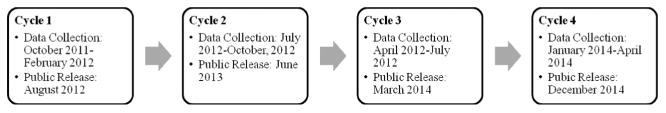

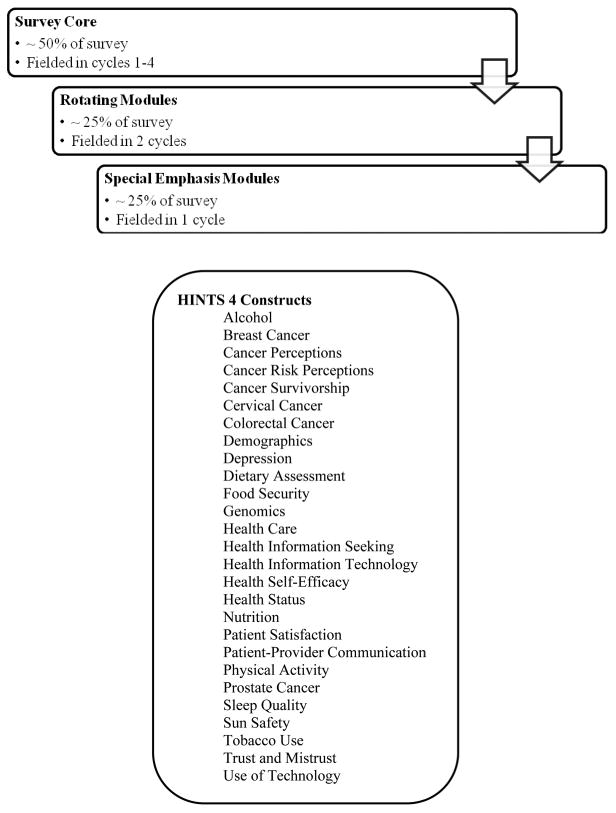

To more quickly address emerging issues in the field of health communication while still maintaining the ongoing measurement of trends, HINTS 4 will include four data collection cycles over the course of 3 years (Figure 1). The instrument for each data collection cycle will include a core module of common items for trend trending in addition to special topic modules to be implemented in only some of the cycles, increasing capacity of the HINTS instruments to include a broader array of topics and measures. The structure and construct-level content for HINTS 4 are summarized in Figure 2. The overall sample size for all four cycles of HINTS 4 combined will be approximately 14,000 respondents, nearly twice the size of previous rounds of HINTS data collections.

Figure 1.

HINTS 4 anticipated data collection and public data release timeline.

Figure 2.

Structure and construct level content of HINTS 4.

Cycle 1 Data Collection

Data collection for Cycle 1 of HINTS 4 was initiated in October 2011 and concluded in February of 2012. HINTS 4 Cycle 1 was a self-administered mailed questionnaire. The protocol for mailing the questionnaires involved an initial mailing of the questionnaire, followed by a reminder card mailing, and up to three additional mailings of the questionnaire as needed by non-responding households. As with prior HINTS administrations, methodological experiments were embedded to explore the potential effect of varying methodological strategies on response rates. Two methods of respondent selection were used for Cycle 1: the all-adult method and the next-birthday method. In the all-adult method all adults residing in a sampled household were asked to complete the questionnaire. In the next-birthday method, the adult who would have the next birthday in the sampled household was asked to complete the questionnaire.

Sample

The sampling frame consisted of a database of all nonvacant residential addresses in the United States used by Marketing Systems Group to provide random samples of addresses. To increase the precision of estimates for racial and ethnic subpopulations, the sampling frame of addresses was grouped into high and low racial and ethnic minority strata and high minority areas were oversampled. The sample design involved two stages wherein a stratified sample of addresses was selected from a file of residential addresses, and a subsequent sample of adults was selected within each sampled household using one of the two methods described previously.

Response Rates

Household response rates were calculated separately for each respondent selection method using the American Association for Public Opinion Research (2011) response rate 2 (RR2) formula. The household response rate for the next-birthday method was 37.9%. The household response rate for the all-adult method was 35.3%. For the all-adult method, a within household response rate was calculated at 84.6%. The final response rate was determined by combining response rates across respondent selection method in proportion to the sample allocated to each method. For Cycle 1 of HINTS 4, the final response rate was 36.7%.

Public Release of Data

As with the first three rounds of HINTS, data from HINTS 4 will be made available for public use following the removal of all identifying information, such as names, addresses, or telephone numbers. Data files will be prepared in accordance with standards for protecting the privacy of the participants. Cycle 1 of HINTS 4 data will be released to the public in August 2012. For Cycles 2–4, data, public release of data is planned approximately 6 months after each data collection effort is completed (Figure 1).

Priorities for Data Analysis

The purpose of funding a national probability survey to assess health communication processes is to provide communication researchers and practitioners with population estimates of the prevalence of cancer-relevant knowledge, attitudes, and information-seeking behaviors in the U.S. adult population (18+ years of age). Priorities for data analysis across the core content of the four cycles of HINTS 4 draw upon theoretical considerations and public health concerns in health communication and health information technology. Specific research questions follow from the Health People 2020 objectives in health communication and health information technology (Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, 2010) to examine the following important issues with relevance to cancer:

Considering the full range of communication channels, what are the major sources of cancer information for the American public, and has source usage changed over time in the population?

To what extent is access or lack of access to different sources of health information associated with cancer knowledge or behaviors, and has access to different sources of health information changed over time with resulting change in knowledge and behavior?

What segments of the U.S. population depend on information technology (i.e., the Internet) to meet at least some of their cancer information needs, and has dependence on technology for health information changed over time?

How trustworthy are available sources of health information perceived to be?

How satisfied are people with their access to health information and the content of the information they receive?

Have perceptions of trust in and satisfaction with various sources of health information changed over time?

What is the level of knowledge about cancer incidence, etiology, prevention, detection, and treatability and what are the psychological and structural determinants of this knowledge?

Are cancer prevention behaviors related to health information seeking and health information exposure from various sources?

Have there been population shifts in cancer prevention behaviors, and do such shifts correspond to changes in use of information sources?

How do people want to get information about cancer, and have those preferences changed over time?

Conclusions

The authors of the Healthy People 2020 initiative argue that effective use of “communication and technology by health care and public health professionals can bring about an age of patient- and public-centered health information and services” (Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, 2010). Effective communication and meaningful use of health information technology in health care delivery and public health efforts have the potential to create patient- and public-centered health information and services. Developing effective health communication messages, including cancer prevention messages, is relevant to myriad stakeholders because health communication can contribute to all aspects of disease prevention and health promotion (Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion., 2010).

Communicating public health messages requires comprehensive understanding of public access to cancer-related information; public trust in health information sources; public knowledge of health risks and prevention strategies; and understanding of factors that facilitate or hinder effective health communication (Hesse et al., 2006; Nelson et al., 2004; Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, 2010). HINTS data capture these trends offering a unique resource for communication planners and researchers in their common aim to reduce the population cancer burden through effective, evidence-based, and patient- or public-centered communication (Hesse et al., 2006; Hesse et al., 2005; Nelson et al., 2004). Strategic application of health information technology and health communication processes can serve to improve health care safety and quality, improve efficiencies in the delivery of health care, support community and home-based care, improve health-related decision making, and raise public awareness of health issues and improve relevant health skills (Hesse, 2005; Hesse, Arora, Burke Beckjord, & Finney Rutten, 2008; Hesse et al., 2011).

Acknowledgments

This project has been funded in part with federal funds from the National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health, under contract HHSN261200800001E. The content of this publication does not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the Department of Health and Human Services, not does mention of trade names, commercial products, or organizations imply endorsement by the US government.

Contributor Information

Lila J. Finney Rutten, Clinical Monitoring Research Program, SAIC-Frederick, Inc., NCI-Frederick, Frederick, Maryland, USA

Terisa Davis, Westat, Rockville, Maryland, USA.

Ellen Burke Beckjord, University of Pittsburgh Cancer Institute, University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, USA.

Kelly Blake, Behavioral Research Program, National Cancer Institute, Bethesda, Maryland, USA.

Richard P. Moser, Behavioral Research Program, National Cancer Institute, Bethesda, Maryland, USA

Bradford W. Hesse, Behavioral Research Program, National Cancer Institute, Bethesda, Maryland, USA

References

- American Association for Public Opinion Research. Standard definitions: Final dispositions of case codes and outcome rates for surveys. 7th. Deerfield, IL: Westat; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Cantor D, Coa K, Crystal-Mansour S, Davis T, Dipko S, Sigman R. Health Information National Trends Survey (HINTS) 2007: Final Report. Rockville, MD: Westat; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Cheong PH, Feeley TH, Servoss T. Understanding health inequalities for uninsured Americans: A population-wide survey. Journal of Health Communication. 2007;12:285–300. doi: 10.1080/10810730701266430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chou WY, Wang LC, Finney Rutten LJ, Moser RP, Hesse BW. Factors associated with Americans' ratings of health care quality: What do they tell us about the raters and the health care system? Journal of Health Communication. 2010;15(Suppl 3):147–156. doi: 10.1080/10810730.2010.522692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciampa PJ, Osborn CY, Peterson NB, Rothman RL. Patient numeracy, perceptions of provider communication, and colorectal cancer screening utilization. Journal of Health Communication. 2010;15(Suppl 3):157–168. doi: 10.1080/10810730.2010.522699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clayman ML, Manganello JA, Viswanath K, Hesse BW, Arora NK. Providing health messages to Hispanics/Latinos: Understanding the importance of language, trust in health information sources, and media use. Journal of Health Communication. 2010;15(Suppl 3):252–263. doi: 10.1080/10810730.2010.522697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curtin R, Presser S, Singer E. Changes in the telephone survey nonresponse over thepast quarter century. Public Opinion Quarterly. 2005;69:87–98. [Google Scholar]

- Dillman DA. Mail and Internet surveys: The tailored design method. 2nd. New York, NY: Wiley; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Ford JS, Coups EJ, Hay JL. Knowledge of colon cancer screening in a national probability sample in the United States. Journal of Health Communication. 2006;11(Suppl 1):19–35. doi: 10.1080/10810730600637533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geiger BF, O'Neal MR, Firsing SL, III, Smith KH, Chandan P, Schmidt A, Jackson JB. HealthyME HealthyU: A collaborative project to enhance access to health information and services for individuals with disabilities. Journal of Health Communication. 2010;15(Suppl 3):46–59. doi: 10.1080/10810730.2010.525295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han PK, Moser RP, Klein WM. Perceived ambiguity about cancer prevention recommendations: Relationship to perceptions of cancer preventability, risk, and worry. Journal of Health Communication. 2006;11(Suppl 1):51–69. doi: 10.1080/10810730600637541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hesse BW. Harnessing the power of an intelligent health environment in cancer control. Studies in Health, Technology, and Informatics. 2005;118:159–176. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hesse BW, Arora NK, Burke Beckjord E, Finney Rutten LJ. Information support for cancer survivors. Cancer. 2008;112(11 Suppl):2529–2540. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hesse BW, Moser RP, Rutten LJ, Kreps GL. The health information national trends survey: Research from the baseline. Journal of Health Communication. 2006;11(Suppl. 1):vii–xvi. doi: 10.1080/10810730600692553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hesse BW, Nelson DE, Kreps GL, Croyle RT, Arora NK, Rimer BK, Viswanath K. Trust and sources of health information: The impact of the Internet and its implications for health care providers: Findings from the first Health Information National Trends Survey. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2005;165:2618–2624. doi: 10.1001/archinte.165.22.2618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hesse BW, O'Connell M, Augustson EM, Chou WY, Shaikh AR, Rutten LJ. Realizing the promise of Web 2.0: Engaging community intelligence. Journal of Health Communication. 2011;16(Suppl 1):10–31. doi: 10.1080/10810730.2011.589882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hou J, Shim M. The role of provider–patient communication and trust in online sources in Internet use for health-related activities. Journal of Health Communication. 2010;15(Suppl 3):186–199. doi: 10.1080/10810730.2010.522691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman A, Augustson E, Davis K, Finney Rutten LJ. Awareness and use of tobacco quitlines: Evidence from the Health Information National Trends Survey. Journal of Health Communication. 2010;15(Suppl 3):264–278. doi: 10.1080/10810730.2010.526172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kealey E, Berkman CS. The relationship between health information sources and mental models of cancer: Findings from the 2005 Health Information National Trends Survey. Journal of Health Communication. 2010;15(Suppl 3):236–251. doi: 10.1080/10810730.2010.522693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobetz E, Kornfeld J, Vanderpool RC, Finney Rutten LJ, Parekh N, O'Bryan G, Menard J. Knowledge of HPV among United States Hispanic women: Opportunities and challenges for cancer prevention. Journal of Health Communication. 2010;15(Suppl 3):22–29. doi: 10.1080/10810730.2010.522695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koch-Weser S, Bradshaw YS, Gualtieri L, Gallagher SS. The Internet as a health information source: Findings from the 2007 Health Information National Trends Survey and implications for health communication. Journal of Health Communication. 2010;15(Suppl 3):279–293. doi: 10.1080/10810730.2010.522700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kontos EZ, Emmons KM, Puleo E, Viswanath K. Communication inequalities and public health implications of adult social networking site use in the United States. Journal of Health Communication. 2010;15(Suppl 3):216–235. doi: 10.1080/10810730.2010.522689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koshiol J, Rutten LF, Moser RP, Hesse N. Knowledge of human papilloma-virus: Differences by self-reported treatment for genital warts and sociodemographic characteristics. Journal of Health Communication. 2009;14:331–345. doi: 10.1080/10810730902873067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langford A, Resnicow K, An L. Clinical trial awareness among racial/ethnic minorities in HINTS 2007: Sociodemographic, attitudinal, and knowledge correlates. Journal of Health Communication. 2010;15(Suppl 3):92–101. doi: 10.1080/10810730.2010.525296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ling BS, Klein WM, Dang Q. Relationship of communication and information measures to colorectal cancer screening utilization: Results from HINTS. Journal of Health Communication. 2006;11(Suppl 1):181–190. doi: 10.1080/10810730600639190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Link MW, Mokdad AH. Effects of survey mode on self-reports of adult alcohol consumption: A comparison of mail, web, and telephone approaches. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2005;66:239–245. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2005.66.239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manganello JA, Clayman ML. The association of understanding of medical statistics with health information seeking and health provider interaction in a national sample of young adults. Journal of Health Communication. 2011;16(Suppl 3):163–176. doi: 10.1080/10810730.2011.604704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marks R, Ok H, Joung H, Allegrante JP. Perceptions about collaborative decisions: Perceived provider effectiveness among 2003 and 2007 Health Information National Trends Survey (HINTS) respondents. Journal of Health Communication. 2010;15(Suppl 3):135–146. doi: 10.1080/10810730.2010.522701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McBride B, Cantor D. Factors in errors of omission on a self-administered paper questionnaire. Journal of Health Communication. 2010;15(Suppl 3):102–116. doi: 10.1080/10810730.2010.525690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McQueen A, Vernon SW, Meissner HI, Rakowski W. Risk perceptions and worry about cancer: Does gender make a difference? Journal of Health Communication. 2008;13(1):56–79. doi: 10.1080/10810730701807076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moser RP, Beckjord EB, Finney Rutten LJ, Blake K, Hesse BW. Using collaborative Web technology to construct the Health Information National Trends Survey. Journal of Health Communication. 2012;17 doi: 10.1080/10810730.2012.700999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson DE, Kreps GL, Hesse BW, Croyle RT, Willis G, Arora NK, Alden S. The Health Information National Trends Survey (HINTS): Development, design, and dissemination. Journal of Health Communication. 2004;9:443–460. doi: 10.1080/10810730490504233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen GT, Bellamy SL. Cancer information seeking preferences and experiences: Disparities between Asian Americans and Whites in the Health Information National Trends Survey (HINTS) Journal of Health Communication. 2006;11(Suppl 1):173–180. doi: 10.1080/10810730600639620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niederdeppe J, Frosch DL, Hornik RC. Cancer news coverage and information seeking. Journal of Health Communication. 2008;13:181–199. doi: 10.1080/10810730701854110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. Healthy People 2020. 2010 Retrieved from http://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/default.aspx.

- Oh A, Shaikh A, Waters E, Atienza A, Moser RP, Perna F. Health disparities in awareness of physical activity and cancer prevention: Findings from the National Cancer Institute's 2007 Health Information National Trends Survey (HINTS) Journal of Health Communication. 2010;15(Suppl 3):60–77. doi: 10.1080/10810730.2010.522694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ok H, Marks R, Allegrante JP. Perceptions of health care provider communication activity among American cancer survivors and adults without cancer histories: An analysis of the 2003 Health Information Trends Survey (HINTS) Data. Journal of Health Communication. 2008;13:637–653. doi: 10.1080/10810730802412172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peytchev A, Ridenhour J, Krotki K. Differences between RDD telephone and ABS mail survey design: coverage, unit nonresponse, and measurement error. Journal of Health Communication. 2010;15(Suppl 3):117–134. doi: 10.1080/10810730.2010.525297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rains SA. Perceptions of traditional information sources and use of the world wide web to seek health information: Findings from the health information national trends survey. Journal of Health Communication. 2007;12:667–680. doi: 10.1080/10810730701619992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rutten LJ, Augustson E, Wanke K. Factors associated with patients' perceptions of health care providers' communication behavior. Journal of Health Communication. 2006;11(Suppl 1):135–146. doi: 10.1080/10810730600639596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rutten LJ, Squiers L, Hesse B. Cancer-related information seeking: Hints from the 2003 Health Information National Trends Survey (HINTS) Journal of Health Communication. 2006;11(Suppl 1):147–156. doi: 10.1080/10810730600637574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shim M, Kelly B, Hornik R. Cancer information scanning and seeking behavior is associated with knowledge, lifestyle choices, and screening. Journal of Health Communication. 2006;11(Suppl 1):157–172. doi: 10.1080/10810730600637475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singer E, Van Hoewyk J, Maher MP. Experiments with incentives in telephone surveys. Public Opinion Quarterly. 2000;64:171–188. doi: 10.1086/317761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith SG, Wolf MS, von Wagner C. Socioeconomic status, statistical confidence, and patient–provider communication: An analysis of the Health Information National Trends Survey (HINTS 2007) Journal of Health Communication. 2010;15(Suppl 3):169–185. doi: 10.1080/10810730.2010.522690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Squiers L, Bright MA, Rutten LJ, Atienza AA, Treiman K, Moser RP, Hesse B. Awareness of the National Cancer Institute's Cancer Information Service: Results from the Health Information National Trends Survey (HINTS) Journal of Health Communication. 2006;11(Suppl 1):117–133. doi: 10.1080/10810730600637517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson OM, Yaroch AL, Moser RP, Finney Rutten LJ, Petrelli JM, Smith-Warner SA, Nebeling L. Knowledge of and adherence to fruit and vegetable recommendations and intakes: Results of the 2003 Health Information National Trends Survey. Journal of Health Communication. 2011;16:328–340. doi: 10.1080/10810730.2010.532293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tortolero-Luna G, Finney Rutten LJ, Hesse BW, Davis T, Kornfeld J, Sanchez M, Davis K. Health and cancer information seeking practices and preferences in Puerto Rico: Creating an evidence base for cancer communication efforts. Journal of Health Communication. 2010;15(Suppl 3):30–45. doi: 10.1080/10810730.2010.522698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanderpool RC, Huang B. Cancer risk perceptions, beliefs, and physician avoidance in Appalachia: Results from the 2008 HINTS Survey. Journal of Health Communication. 2010;15(Suppl 3):78–91. doi: 10.1080/10810730.2010.522696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viswanath K. Science and society: The communications revolution and cancer control. Nature Reviews Cancer. 2005;5:828–835. doi: 10.1038/nrc1718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viswanath K, Breen N, Meissner H, Moser RP, Hesse B, Steele WR, Rakowski W. Cancer knowledge and disparities in the information age. Journal of Health Communication. 2006;11(Suppl 1):1–17. doi: 10.1080/10810730600637426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ye Y. Correlates of consumer trust in online health information: Findings from the health information national trends survey. Journal of Health Communication. 2011;16(1):34–49. doi: 10.1080/10810730.2010.529491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zajac LE, Klein WM, McCaul KD. Absolute and comparative risk perceptions as predictors of cancer worry: Moderating effects of gender and psychological distress. Journal of Health Communication. 2006;11(Suppl 1):37–49. doi: 10.1080/10810730600637301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao X. Cancer information disparities between U.S.- and foreign-born populations. Journal of Health Communication. 2010;15(Suppl 3):5–21. doi: 10.1080/10810730.2010.522688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]