Abstract

Phosphatase and tensin homolog deleted on chromosome 10 (PTEN) is rarely mutated in pancreatic cancers, but its regulation by transforming growth factor (TGF)-β might mediate growth suppression and other oncogenic actions. Here, we examined the role of TGFβ and the effects of oncogenic K-RAS/ERK upon PTEN expression in the absence of SMAD4. We utilized two SMAD4-null pancreatic cell lines, CAPAN-1 (K-RAS mutant) and BxPc-3 (WT-K-RAS), both of which express TGFβ surface receptors. Cells were treated with TGFβ1 and separated into cytosolic/nuclear fractions for western blotting with phospho-SMAD2, SMAD 2, 4 phospho-ATP-dependent tyrosine kinases (Akt), Akt and PTEN antibodies. PTEN mRNA levels were assessed by reverse transcriptase–polymerase chain reaction. The MEK1 inhibitor, PD98059, was used to block the downstream action of oncogenic K-RAS/ERK, as was a dominant-negative (DN) K-RAS construct. TGFβ increased phospho-SMAD2 in both cytosolic and nuclear fractions. PD98059 treatment further increased phospho-SMAD2 in the nucleus of both pancreatic cell lines, and DN-K-RAS further improved SMAD translocation in K-RAS mutant CAPAN cells. TGFβ treatment significantly suppressed PTEN protein levels concomitant with activation of Akt by 48 h through transcriptional reduction of PTEN mRNA that was evident by 6 h. TGFβ-induced PTEN suppression was reversed by PD98059 and DN-K-RAS compared with treatments without TGFβ. TGFβ-induced PTEN expression was inversely related to cellular proliferation. Thus, oncogenic K-RAS/ERK in pancreatic adenocarcinoma facilitates TGFβ-induced transcriptional down-regulation of the tumor suppressor PTEN in a SMAD4-independent manner and could constitute a signaling switch mechanism from growth suppression to growth promotion in pancreatic cancers.

Introduction

Pancreatic cancer has the highest death rate to incident ratio of cancers in the USA (1). The pathogenesis of pancreatic cancer is complex and seems to involve environmental influences and genetic alterations.

Transforming growth factor (TGF)-β1 over-expression is associated with poor survival in patients with pancreatic cancer (2). It often suppresses early tumorigenesis but later enhances tumor progression (3–5). Although TGFβ1 exerts an inhibitory effect on cancer cell growth in vitro, it also stimulates the synthesis of the extracellular matrix and has been implicated in the regulation of cell differentiation, angiogenesis, immunosuppression and fibrosis (6).

TGFβ signals through a heterotetrameric receptor complex comprising type II receptors and type I receptors, both serine/threonine kinases (7), followed by a canonical SMAD-dependent signaling cascade (8). Several studies have shown that expression of dominant-negative (DN) transforming growth factor-β receptor type 2 constructs in mice lead to enhanced mammary tumorigenesis with or without carcinogens (9–11). Moreover, results obtained from conditional ablation of SMAD4 in mouse mammary epithelium (12) confirm the importance of signaling through the TGFβ/SMAD pathway during tumor initiation and progression as suggested in earlier reports of enhanced colon tumorigenesis in SMAD4-null mouse models (13,14). These effects, however, are not limited to the mammary gland and colon since DN transforming growth factor-β receptor type 2 expression in the lung and skin also resulted in enhanced carcinogen-induced tumorigenesis (11,15).

The genetic profile of pancreatic cancer suggests contribution from both oncogenes and tumor suppressor genes. The tumor suppressor SMAD4 is deleted from >64% of pancreatic cancers (16,17), removing this TGFβ signaling molecule from the majority of these tumors. K-RAS is mutated in >90% of pancreatic cancers, although the presence of oncogenic K-RAS is not specific to cancer as it can also be found in benign pancreatic lesions (18,19). Numerous reports have described a correlation between RAS transformation and deficient TGFβ responsiveness, particularly with regards to TGFβ anti-mitogenic responses. RAS transformation of lung, intestinal, liver or mammary epithelial cells confers resistance to growth inhibition by TGFβ (20,21). Kretzschmar et al. (22) showed that oncogenic RAS inhibits the TGFβ signal transduction pathway at the level of SMAD by RAS/ERK-induced phosphorylation of clusters of four Ser/Thr-Pro sites in the linker region of SMAD2 and SMAD3 and preventing accumulation of SMAD2 and SMAD3 in the nucleus and inhibiting TGFβ signaling.

Phosphatase and tensin homolog deleted on chromosome 10 (PTEN), also known as MMAC1/TEP1, is localized to chromosome 10q23 (23,24). It is a dual specificity phosphatase and antagonizes phosphoinositide-3-kinase (PI3K)/ATP-dependent tyrosine kinases (Akt) signaling pathway (25), and thus plays a functional role in cell cycle arrest and apoptosis (26,27). Description of germ line mutations and deletions of PTEN in two hereditary cancer predisposition diseases, Cowden Disease and the Bannayan–Riley–Ruvalcaba syndrome (28–31), point to a role of PTEN as a tumor suppressor gene in the pathogenesis of both benign and malignant growth. PTEN is one of the most frequently mutated proteins in a variety of cancers (23,24,32), but PTEN mutations rarely occur in pancreatic cancer (33). PTEN expression has been shown to be regulated by TGFβ1 in keratinocytes (34), and PTEN mRNA levels were also reduced in a model of TGFβ1 over-expressing transgenic mice that develop pancreatic fibrosis (35). Reduction of PTEN mRNA levels in pancreatic cancer cells following TGFβ1 treatment has also been reported (35). Although PTEN is not found mutated in pancreatic cancers, the reduction of its expression may give pancreatic cells an additional growth advantage.

Our present study focused on whether TGFβ modulates PTEN expression in SMAD4-null pancreatic cancer cells and whether that modulation was influenced by oncogenic K-RAS. This investigation may provide clues to the conversion of TGFβ function from that of a tumor suppressor in early carcinogenesis to one of a tumor promoter in more mature cancers. Both SMAD4 loss and K-RAS activation are typical findings in pancreatic cancers. We found that TGFβ reduces PTEN expression in the absence of SMAD4, and oncogenic K-RAS and downstream effectors potentiate TGFβ-suppressed PTEN expression. Inhibition of K-RAS or its downstream effectors functionally ‘switched on’ PTEN expression where it may promote tumor suppression.

Materials and methods

Materials and reagents

PD98059, a MEK inhibitor, was purchased from PharMingen (San Diego, CA). A solution of PD98059 in dimethyl sulfoxide (Sigma, St Louis, MO) was prepared and used after diluting with medium for each assay. Dimethyl sulfoxide was also used as a blank control. DN construct of K-RAS was a generous gift from Dr Rik Derynck (University of California, San Francisco, CA).

Cell cultures

BxPC-3 and CAPAN-1 cells were obtained from American Type Culture Collection and they were maintained in RPMI and Dulbecco's modified Eagle medium (Gibco BRL, Gaithersburg, MA), respectively, supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum (Gibco BRL), without any antibiotics in an incubator at 37°C and 5% CO2. To analyze the effect of TGFβ1 on PTEN expression and cell proliferation, pancreatic cancer cell lines were grown to 70–80% confluency in the corresponding medium containing 10% fetal bovine serum. Afterwards, cells were washed twice in phosphate-buffered saline, starved for 30 min in serum-free medium and finally treated for 24 and 48 h with 10 ng/ml TGFβ1 or medium alone.

Cell growth assay

For determination of cell number, 30 000 human pancreatic carcinoma cells per well were seeded onto six-well plates (Nunc, Wiesbaden, Germany), and incubated overnight in complete growth medium (RPMI 1640 + 10% fetal bovine serum). Complete medium was replaced with serum-depleted medium with or without TGFβ and/or inhibitors. Cell numbers from each well were determined every 24 h for 3 days. Up to 12 independent experiments were performed.

Transfection of the CAPAN-1 cells

One day before transfection, exponentially growing cells were trypsinized, and 1–2 × 106 cells were plated onto 10 cm Petri dishes. Cells were then transfected the next day with the DN K-RAS construct or empty vector. The DN construct is known to suppress activated RAS by blocking RAS guanine nucleotide exchange factors (36). Transfection was carried out using Transfast (Promega, Madison, WI). Briefly, plasmid DNA was mixed with serum-free medium, followed by transfection reagent at the charge ratio of 1:1. The mixture was allowed to react for 10–15 min, and it was transferred to the cells to be transfected. One hour after transfection, complete medium was overlaid on top of the cells and allowed to incubate for 48 h.

Total RNA extraction and semi-quantative reverse transcriptase–polymerase chain reaction

Total RNA extraction from the control and TGFβ-treated cells was conducted using Trizol reagent (Invitrogen Corporation, Carlsbad, CA). Cells grown on six-well plate were lysed with the reagent (1 ml per well). Lysates were combined with chloroform, mixed and the pellets precipitated with isopropanol and 75% ethanol and air-dried. Total RNA was then extracted and re-suspended in water. Two micrograms of total RNA were reversed transcribed into cDNA and amplified by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) for PTEN and SMAD4 expression (SuperScript II, Invitrogen Corporation). Briefly, following inactivation at 65°C for 10 min, 1 μl of the reaction mixture were incubated in buffer containing 0.2 mM concentrations of dATP, dCTP, dGTP, dTTP, 0.2 μM concentrations each of oligonucleotide primers, 3 mM MgCl2 and a 10× buffer consisting of 200 mM Tris–HCl (pH 8.0), 500 mM KCl and 1 U Taq polymerase. PCR primers were designed to amplify a region spanning from nucleotides 117 to 741 of the PTEN gene (forward strand, 5′-CAGAAAGACTTGAAGGCGTAT-3′ and reverse strand, 5′-AACGGCTGAGGGAACTC-3′), as described previously (37). The 624 bp fragment contains an NsiI restriction site allowing to distinguish this region from the PTEN pseudogene (37). PCR primers used to amplify SMAD4 were forward strand, 5′-AACGTTAGCTGTTGTTTTTCAC-3′ and reverse strand, 5′-AGAGTATGTGAAGAGATGGAG-3′. The conditions for PCR reactions of PTEN were as follows: denaturation at 95°C for 3 min and 35 cycles of 94°C for 30 s, 55°C for 30 s and 74°C for 4 min. Primers used for GAPDH were used as a loading control (forward strand, 5′-ACCACAGTCCATGCCATCAC-3′ and reverse strand, 5′-TCCACCACCCTGTTGCTGTA-3′).

Nuclear–cytoplasmic fractionation, western blotting analysis and immunoprecipitation

Cytoplasmic- and nuclear-enriched fractions were prepared by scraping 5 × 106 cells in 1.5 ml of hypotonic lysis buffer consisting of 10 mM N-2-hydroxyethylpiperazine-N′-2-ethanesulfonic acid (pH 7.9), 2.5 mM MgCl2, 0.2 mM ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid, 0.5 mM dithiothreitol, 40 mM NaF, 4 mM β-glycerophosphate, 0.2% Nonidet P-40, 0.5 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 0.5 mM benzamidine HCl and 2 μg/ml each aprotinin and leupeptin. Cells suspension was maintained on ice for 20 min and inverted several times. The nuclear fraction (P1) was isolated by centrifugation of the suspension at 3500g for 5 min, followed by washing in 0.5 ml of hypotonic buffer. The supernatant, representative of cytoplasmic fraction (S1), was added with NaCl to 0.14 M final concentration and clarified by 10 min centrifugation at 10 000g. Nuclear proteins were extracted from nuclear fraction by lysis in 0.3 ml hypertonic lysis buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, 0.14 M NaCl, 0.25 M KCl, 1 mM ethyleneglycol-bis(aminoethylether)-tetraacetic acid, 1% Triton X-100, 0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate, 0.5 mM dithiothreitol, plus protease and phosphatase inhibitors), followed by 1 h rotation at 4°C, and clarified by 10 min centrifugation at 10 000g. Respectively, 50 μg of cytoplasmic and 30 μg of nuclear proteins were analyzed by western blotting and probed to specific antibodies. Phospho-SMAD2, phospho-Akt, ERK1/2 and phospho-ERK1/2 1:1000 (Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA); SMAD2 1:1000 (BD Transduction Laboratories, San Diego, CA); SMAD4 (1 μg/ml Upstate Biotechnology, Lake Placid, NY); Akt 1:200 and PTEN 1:500 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA); α-tubulin, histone H1 1:500 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) and GAPDH 1:5000 (Ambion, Austin, TX) antibodies were utilized.

For total lysates, cells were washed three times with ice-cold phosphate-buffered saline, and the cells lysed using total lysis buffer (150 mM NaCl, 10 mM Tris–HCl, pH 7.8, 1 mM ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid, 0.5% Triton X-100, 1 mM sodium orthovanadate) containing protease inhibitors (1 μg/ml leupeptin and 100 μg/ml phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride). Cells were then incubated at 4°C for 30 min with constant shaking, then scraped into microcentrifuge tubes and centrifuged at 12 000g for 15 min to remove insoluble material. The protein content in each sample was determined and adjusted. For immunoprecipitation, lysates were incubated with the immunoprecipitating antibody for 1 h at 4°C, followed by another 1 h incubation with protein A–agarose again at 4°C. Pellets were treated with 2× loading buffer (50 mM Tris, pH 6.8, 2% sodium dodecyl sulfate, 100 mM dithiothreitol, 0.2% bromophenol blue, 20% glycerol) and boiled for 5 min. Loading buffer supernatants from immunoprecipitation studies or cell lysates were then re-suspended in 2× gel loading buffer, boiled for 5 min and then separated by sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (9% polyacrylamide). Resolved proteins were transferred overnight at 4°C onto a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane (Millipore Corporate, Billerica, MA), blocked with a 5% solution of skim milk for 30 min at room temperature, followed by further incubation with monoclonal antibodies to specific antibodies. After washing with phosphate-buffered saline with 1% Tween, the secondary antibody was applied to the membrane. After washing with PBS with 1% Tween, the membrane was treated with a chemiluminescent solution according to manufacturer's instructions and exposed to X-ray film. Densitometric analysis of the blots was performed using an AlphaImager digital imaging system (Alpha Innotech Corporation, San Leandro, CA).

Data analysis

All data are expressed as the means for a series of experiments ± SEM. Data were analyzed by either one-way analysis of variance followed by Student-Newman–Keul's post hoc test or by Student's t-tests for unpaired samples using Instat 3.0 (San Diego, CA). P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

TGFβ mediates SMAD2 activation and nuclear translocation in SMAD4-null and ERK activated BxPc-3 and CAPAN-1 cells

TGFβ1 signaling usually requires SMAD4 together with SMAD2 activation, and nuclear translocation to transmit the TGFβ1-SMAD-responsive signaling event. To assess if TGFβ1 could mediate SMAD2 translocation in SMAD4-null cells, we treated BxPc-3 and CAPAN-1 cells with TGFβ, and observed SMAD compartmentalization using western blots after cytoplasmic/nuclear separation. As shown in Figure 1, TGFβ1 (10 ng/ml) caused activation and translocation of SMAD2 in WT-K-RAS BxPc-3 pancreatic cancer and oncogenic K-RAS CAPAN-1 cells. To address if activated RAS/ERK affected TGFβ-SMAD signaling, we inhibited MEK with the pharmacologic inhibitor, PD98059, which is activated downstream of K-RAS, and inhibited K-RAS itself with a DN-K-RAS construct. Pre-treatment of CAPAN-1 cells with PD98059 or with transfection with the DN-RAS construct (Figure 2A), or pre-treatment of BxPc-3 cells with PD98059 (Figure 2B) in the presence of TGFβ markedly improved SMAD2 activation and translocation. Note that SMAD4 protein was not detectable which further confirmed that the cells are SMAD4 null (Figure 1). Thus, inhibition of the RAS/ERK pathway markedly improved translocation of SMADs in pancreatic cancer cells, indicating a modulatory role by RAS on SMAD2 translocation, even in the absence of SMAD4.

Fig. 1.

Effects of TGFβ treatment on subcellular trafficking of SMAD2 in BxPc-3 and CAPAN-1 cells. Cells were treated with or without TGFβ (10 ng/ml) for 24 h. The cells were then lysed and separated into nuclear and cytoplasmic fractions. Note the appearance of phospho-SMAD2 in the nuclear and cytosolic fractions. Tubulin and histone H1 blots indicate purity of the fractions. SMAD4 is not detectable in either cell line, confirming their SMAD4-null status. T84 colon cancer cells were electrophoresed separately as a positive control for SMAD4 expression.

Fig. 2.

Effect of RAS/ERK inhibition and TGFβ treatment on subcellular trafficking of SMAD2 in CAPAN-1 and BxPc-3 cells. Cells were either pretreated with or without PD98059 (50 μM) for 1 h (A and B), or transiently transfected with a DN construct of K-RAS (A) 48 h before treatment with TGFβ. Cell lysates were blotted with anti-phospho-SMAD2, tubulin and histone antibodies. Note that PD98059 and DN-K-RAS transfection improved TGFβ-induced p-SMAD2 nuclear translocation. Tubulin served as a loading control and indicated purity of the cytoplasmic fractions, whereas histone served as a loading control and purity of the nuclear fractions.

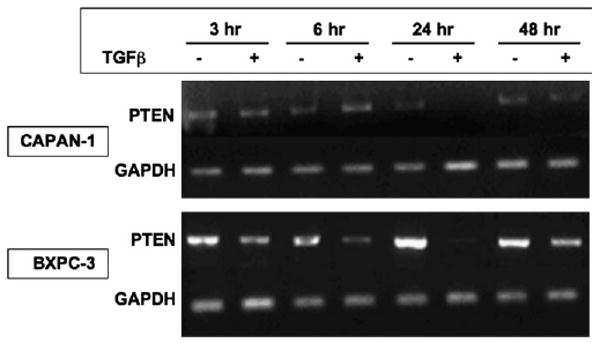

TGFβ treatment suppresses PTEN expression in SMAD4-null pancreatic cells

We examined the effects of TGFβ upon expression of PTEN in SMAD4-null pancreatic cancer cells. Both BxPC-3 and CAPAN-1 cells expressed abundant PTEN mRNA as determined by semi-quantitative reverse transcriptase–PCR (Figure 3). We observed minimal reduction of PTEN mRNA levels after 3 and 6 h of TGFβ1 treatment as compared with the untreated control. However, beginning at 6 h in BxPC-3 cells and by 24 h incubation with TGFβ1, a significant reduction of amplifiable PTEN mRNA was observed in both pancreatic cancer cell lines that recovered to some degree by 48 h after treatment (Figure 3). To verify the PTEN mRNA findings, we then examined the steady-state levels of PTEN protein. At the protein level in BxPc-3 cells, PTEN protein was also present and unchanged from controls through 24 h after TGFβ1 treatment (Figure 4A). However, PTEN protein expression was reduced by 48 h after treatment in BxPc-3 (Figure 4A) and CAPAN-1 cells (not shown, but 48 h data shown in Figure 6B), following the reduced PTEN mRNA expression at 24 h. Therefore, TGFβ1 appears to mediate suppression of PTEN mRNA and protein in a SMAD4-independent manner. PTEN function antagonizes PI3K function, and one of the effectors of PI3K, Akt (25). To assess whether the TGFβ-induced reduction in PTEN expression coincides with an imbalance in function of PI3K, we determined the activation of phospho-Akt at the same time PTEN protein is suppressed. As shown in Figure 4B, the suppression of PTEN by TGFβ is simultaneous with Akt activation, demonstrating functional loss of PTEN.

Fig. 3.

TGFβ treatment down-regulates PTEN transcription. CAPAN-1 and BxPc-3 cells were treated with a single dose of TGFβ (10 ng/ml), and transcription of PTEN was assessed by semi-quantitative reverse transcriptase–PCR. Cells were lysed by Trizol reagents and mRNA was extracted. PTEN mRNA is markedly reduced by 24 h, with subsequent recovery of transcription by 48 h after treatment with TGFβ. Thus, PTEN is down-regulated transiently at the transcriptional level by 24 h after a single TGFβ treatment. GAPDH was used as loading control.

Fig. 4.

TGFβ treatment reduces PTEN protein and activates Akt in SMAD4-null BxPc-3 cells. (A) Cell lysates were blotted with an anti-PTEN antibody. Note that PTEN protein is reduced by ∼50% at 48 h after a single TGFβ dose (10 ng/ml). Data shown are mean ± SEM of four experiments. *P < 0.05 versus control of 48 h. (B) The identical treatment condition in (A) also activated Akt at 48 h in BxPc3 cells. The data shown are representative of three experiments.

Fig. 6.

RAS/ERK inhibition reverses TGFβ-induced PTEN protein suppression in pancreatic cancer cells. (A) We treated ERK-activated BxPc-3 cells with PD98059 in the presence or absence of TGFβ and performed western blotting. Note that pretreatment of cells with PD98059 1 h before TGFβ treatment significantly reversed the suppressive effect of TGFβ on PTEN protein expression (lane 4 versus lane 2). GAPDH was used as a loading control. (B) RAS/ERK-activated CAPAN-1 cells were transfected with 3 μg of DN-K-RAS followed by TGFβ treatment. Cells were then lysed 48 h after TGFβ treatment and analyzed by western blotting for PTEN protein and GAPDH protein as a loading control. Note that direct K-RAS inhibition coupled with TGFβ treatment yielded the greatest expression of PTEN protein, as K-RAS inhibition reversed TGFβ-induced PTEN protein suppression (lane 6 versus lane 4). Data shown are means ± SEM of five experiments. *P < 0.05 versus control and †P < 0.05 versus TGFβ treatment alone.

Modulation of TGFβ-induced PTEN suppression by RAS/ERK constitutes an ‘on/off’ switch

As the RAS/ERK pathway is activated in pancreatic cancers, we assessed if RAS/ERK modulates the TGFβ-induced PTEN suppression observed in the SMAD4-null cell lines. PD98059, the MEK inhibitor, had no effect on amplifiable, semi-quantitative PTEN mRNA alone in CAPAN-1 (Figure 5A) and had no statistical significance to the small observed increase in PTEN mRNA in BxPc-3 cells with 50 μM PD98059 (Figure 5B). Treatment with PD98059, however, rescued TGFβ-induced PTEN mRNA suppression (Figure 5A and B). Similarly at the protein level, PD98059 had no effect on PTEN protein alone (Figure 6A). However, PD98059 reversed TGFβ-induced PTEN protein suppression (Figure 6A). Additionally, CAPAN-1 cells transfected with DN-K-RAS and treated with TGFβ for 48 hreversed the TGFβ-induced PTEN suppression (Figure 6B). Thus, RAS/ERK appears to facilitate TGFβ-induced PTEN suppression as blockage of ERK or RAS restores PTEN expression to pre-treatment levels. Here, RAS/ERK can ‘switch’ PTEN off through TGFβ signaling when activated and restore PTEN to ‘on’ through TGFβ signaling when RAS/ERK is inactivated.

Fig. 5.

PD98059 reverses TGFβ-induced PTEN suppression at the transcriptional level. We treated both SMAD4-null CAPAN-1 (A) and BxPc-3 (B) cells with the MEK1 inhibitor PD98059 and performed semiquantitative reverse transcriptase–PCR for PTEN mRNA at 24 h after TGFβ treatment. PD98059 had little effect on the basal levels of PTEN mRNA (A and B, lanes 2 and 3). However, MEK inhibition rescued TGFβ-induced PTEN transcriptional suppression in a dose-dependent manner (A and B, lanes 5 and 6). Thus, by blocking MEK/ERK activation, downstream of K-RAS activation, PTEN transcription can be switched back ‘on’ in the presence of TGFβ treatment. Data shown are means ± SEM of three to four experiments. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 versus control; ††P < 0.01 and †††P < 0.001 versus TGFβ treatment alone.

TGFβ-induced pancreatic cancer cell proliferation parallels PTEN expression and modulation by RAS/ERK

We assessed the biological consequences of modulation of TGFβ-induced PTEN suppression in the SMAD4-null pancreatic cancer cell lines. Cells were incubated with TGFβ at concentrations shown to suppress PTEN expression both at protein and mRNA levels. As shown in Figure 7, addition of TGFβ for 72 h significantly affects cell growth. TGFβ treatment causes pancreatic cell proliferation when compared with cells that were not treated with TGFβ. We then examined the effect of ERK by inhibiting its upstream inducer MEK1 using PD98059, using three increasing concentrations for inhibition. As shown in Figure 7, PD98059 (12.5 μM to 50 μM) caused a dose-dependent reduction in cell growth with TGFβ treatment. With increasing blockade of MEK1/ERK, TGFβ-induced proliferation was converted to TGFβ-induced growth suppression. Thus, the RAS/ERK pathway contributes to the ability of SMAD4-null pancreatic cancer cells to proliferate. RAS/ERK also modulates TGFβ-induced proliferation, which is paralleled by modulation of TGFβ-induced PTEN expression.

Fig. 7.

Effect of TGFβ and RAS/ERK inhibition on BxPc-3 cell growth. BxPC-3 cells were plated in complete medium (supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum). Cells were then grown in serum-free medium (serum depleted) in control medium, in medium containing 10 ng/ml TGFβ alone, or TGFβ in the presence of 12.5–50 μM PD98059. Cell number was determined on day 3. Data shown are means ± SEM of 12 independent assays and normalized to controls. *P < 0.05 and **P < 0.01 versus cells without TGFβ treatment; †P < 0.05, ††P < 0.01 and †††P < 0.001 versus cells with TGFβ but no PD98059 inhibitor treatment.

Discussion

Our investigation links two commonly affected signaling pathways in pancreatic cancer in the regulation of the tumor suppressor PTEN. PTEN mRNA suppression by TGFβ was first described in keratinocytes when PTEN was originally cloned (34), but the mechanisms for TGFβ-induced PTEN regulation had not been examined. On the other hand, PTEN expression blocked TGFβ-mediated cell invasion whereas PTEN absence increases TGFβ-induced invasion (38). The effects might be mediated by SMAD3, as this intracellular signaling molecule inducibly interacts with PTEN (38). PTEN is commonly affected in multiple cancers, often inactivated by genetic (23,24,33) or epigenetic (39) events during the pathogenesis of a particular cancer. This does not appear to be the case in pancreatic adenocarcinoma. PTEN protein expression in pancreatic cancers has previously been shown via immunohistochemistry to be reduced (35), but not due to genetic events (33). Here, we demonstrate that (i) TGFβ suppresses PTEN expression in SMAD4-null cells at the transcriptional level with subsequent reduction in protein expression and simultaneous increase in phospho-Akt; (ii) RAS/ERK signaling interferes with TGFβ-SMAD nuclear translocation, and SMAD2 translocation is improved with inhibition of RAS/ERK activity; (iii) RAS/ERK signaling facilitates TGFβ-induced PTEN suppression and PTEN expression is restored with inhibition of RAS/ERK; and (iv) proliferation events are inversely related to expression of the tumor suppressor PTEN as regulated by TGFβ and modulated by RAS/ERK.

Taken together, our findings have a number of implications in pancreatic adenocarcinoma. First, we implicate PTEN, as regulated by TGFβ, as a controller of cellular proliferation in pancreatic cancer. Thus, PTEN through ligand regulation, in addition to genetic and epigenetic events, contributes to cancer growth. Regulation of PTEN by TGFβ is complex as this regulation occurs in SMAD4-null cells. As depicted in Figure 8, we speculate that there are at least two intracellular pathways by which TGFβ regulates PTEN. With TGFβ-mediated SMAD-dependent signaling, a well-characterized suppressor pathway in epithelial cells, we suggest that this cascade enhances PTEN expression. In our pancreatic cell models studied, PTEN expression is lessened by (i) loss of SMAD4, which is well-described to facilitate translocation of SMAD2 into the nucleus; and (ii) interference of SMAD2 translocation by activated RAS/ERK, which has been suggested to phosphorylate the linker region of SMAD2/3 and prohibits its translocation to the nucleus (22). Because SMAD2 translocation was improved with blockage of RAS/ERK, as well as restoration of TGFβ-induced PTEN expression, SMAD2 may have nuclear effects that are independent of the presence of SMAD4, and this has been suggested in the literature (40,41).

Fig. 8.

Schematic summarizing our working model. Pancreatic cancer cells are often SMAD4 null, and thus TGFβ utilizes signaling pathways to regulate PTEN expression in a SMAD4-independent manner. We hypothesize that TGFβ-induced SMAD-dependent signaling restores PTEN expression, and speculate that PTEN is suppressed via non-SMAD pathways. As most pancreatic cells have activated RAS/ERK because of oncogenic mutations, TGFβ-SMAD-induced PTEN transcription is inhibited (A). When activated RAS/ERK is blocked, TGFβ-induced PTEN transcription is resumed (B). Thus, in a SMAD4-null environment, activated RAS/ERK acts as a ‘switch’ to convert TGFβ signaling functionally from a tumor suppressor to tumor promoter via modulation of PTEN expression.

Second, we also speculate the presence of a TGFβ-mediated SMAD-independent pathway, which down-regulates PTEN and facilitates cellular growth. Our data strongly suggest the existence of such a pathway because TGFβ mediates PTEN suppression in the absence of SMAD4 and in the presence of activated RAS/ERK, both of which attenuate SMAD2 nuclear translocation. Thus, SMAD-dependent signaling is blocked, which is the case in most human pancreatic cancers, while TGFβ still has cellular effects. There are a number of reports that indicate that TGFβ can have dual roles: growth suppression and, in the right scenario, induce growth proliferation. In many cases, TGFβ's role in cellular proliferation is demonstrated in metastasis, which represents mature cancers with the accumulated pathway derangements. In pancreatic cancers, TGFβ ligand is often up-regulated, and this is believed to be due to loss of negative feedback regulation by SMAD-dependent signaling (35). The increased amounts of ligand could help increasingly signal through a proliferative-driven SMAD-independent pathway through down-regulation of PTEN favoring unbalanced mitogenic PI3K signaling. Recently, a second mechanism has been demonstrated that reduces PTEN levels after TGFβ stimulation. TGFβ signaling induces dephosphorylation of PTEN, reducing its stability in the cytoplasm (42). Thus, there appears to be at least two mechanisms, reduced PTEN expression and reduced PTEN stability, to decrease PTEN protein levels to increase the pancreatic cancer cell's ability to proliferate with TGFβ signaling.

Third, RAS/ERK, which is activated in over 90% of pancreatic cancers, modulates PTEN expression through TGFβ signaling. The regulation appears to be through blocking SMAD translocation, as previously suggested in the literature (22). However, K-RAS mutations, in particular, are one of the earliest events in pancreatic cancer pathogenesis, and oncogenic mutations are seen in benign pancreatic conditions such as pancreatitis (18,19). Because RAS/ERK activation is a potent inhibitor of SMAD signaling, TGFβ-induced PTEN regulation is likely affected at a very early stage in pancreatic carcinogenesis.

In summary, we indicate that PTEN may be a key tumor suppressor involved in pancreatic tumorigenesis. Unlike other tumors in which PTEN is inactivated by a variety of genetic or epigenetic mechanisms, PTEN expression is ligand regulated by TGFβ signaling. The TGFβ-induced PTEN expression may be determined by either or both of SMAD-dependent and SMAD-independent signaling pathways. When SMAD-dependent signaling is blocked by oncogenic K-RAS or activated ERK, TGFβ induces down-regulation of PTEN coupled with growth proliferation of pancreatic cells. When RAS/ERK activation is blocked, SMAD2 nuclear translocation is restored (even without SMAD4), TGFβ-induced PTEN down-regulation is reversed and cellular proliferation is reduced to non-TGFβ-induced levels. We suggest that RAS/ERK activation ‘switches’ the balance of the dual roles of TGFβ in favor of proliferation when PTEN is turned off, and the switch can be reversed with blockage of RAS/ERK to turn PTEN expression on reducing cellular proliferation. This regulatory mechanism could potentially be controlled pharmacologically.

Acknowledgments

Funding: United States Public Health Service (K01-DK073090 to J.Y.C., T32-HL07212 to S.E.B., CA90231 and DK067287 to J.M.C.); National Pancreas Foundation; VA Research Service.

Abbreviations

- Akt

ATP-dependent tyrosine kinases

- DN

dominant negative

- PTEN

phosphatase and tensin homolog deleted on chromosome 10

- PI3K

phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase

- PCR

polymerase chain reaction

- TGF

transforming growth factor

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Statement: None declared.

References

- 1.Warshaw AL, et al. Pancreatic carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 1992;326:455–465. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199202133260706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Friess H, et al. Enhanced expression of transforming growth factor beta isoforms in pancreatic cancer correlates with decreased survival. Gastroenterology. 1993;105:1846–1856. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(93)91084-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Derynck R, et al. TGF-beta signaling in tumor suppression and cancer progression. Nat Genet. 2001;29:117–129. doi: 10.1038/ng1001-117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pasche B. Role of transforming growth factor beta in cancer. J Cell Physiol. 2001;186:153–168. doi: 10.1002/1097-4652(200002)186:2<153::AID-JCP1016>3.0.CO;2-J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Roberts AB, et al. The two faces of transforming growth factor beta in carcinogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:8621–8623. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1633291100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Massague J. TGFbeta signaling: receptors, transducers, and Mad proteins. Cell. 1996;85:947–950. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81296-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Massague J, et al. Transcriptional control by the TGF-beta/Smad signaling system. EMBO J. 2000;19:1745–1754. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.8.1745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.ten Dijke P, et al. New insights into TGF-beta-Smad signalling. Trends Biochem Sci. 2004;29:265–273. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2004.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Siegel PM, et al. Transforming growth factor beta signaling impairs Neu-induced mammary tumorigenesis while promoting pulmonary metastasis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:8430–8435. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0932636100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gorska AE, et al. Transgenic mice expressing a dominant-negative mutant type II transforming growth factor-beta receptor exhibit impaired mammary development and enhanced mammary tumor formation. Am J Pathol. 2003;163:1539–1549. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9440(10)63510-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bottinger EP, et al. Expression of a dominant-negative mutant TGF-beta type II receptor in transgenic mice reveals essential roles for TGF-beta in regulation of growth and differentiation in the exocrine pancreas. EMBO J. 1997;16:2621–2633. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.10.2621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Li W, et al. Squamous cell carcinoma and mammary abscess formation through squamous metaplasia in Smad4/Dpc4 conditional knockout mice. Development. 2003;130:6143–6153. doi: 10.1242/dev.00820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Takaku K, et al. Intestinal tumorigenesis in compound mutant mice of both Dpc4 (Smad4) and Apc genes. Cell. 1998;92:645–656. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81132-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Takaku K, et al. No effects of Smad2 (madh2) null mutation on malignant progression of intestinal polyps in Apc(delta716) knockout mice. Cancer Res. 2002;62:4558–4561. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Amendt C, et al. Expression of a dominant negative type II TGF-beta receptor in mouse skin results in an increase in carcinoma incidence and an acceleration of carcinoma development. Oncogene. 1998;17:25–34. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1202161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hahn SA, et al. Homozygous deletion map at 18q21.1 in pancreatic cancer. Cancer Res. 1996;56:490–494. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hahn SA, et al. DPC4, a candidate tumor suppressor gene at human chromosome 18q21.1. Science. 1996;271:350–353. doi: 10.1126/science.271.5247.350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Carethers JM, et al. Neoplasia of the Gastrointestinal Tract. In: Yamada T, Alpers DH, Kaplowitz N, Laine L, Owyang C, Powell DW, editors. Textbook of Gastroenterology. 4th. Lippincott-Raven Publishers; Philadelphia, PA: 2003. pp. 557–583. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Laghi L, et al. Common occurrence of multiple K-RAS mutations in pancreatic cancers with associated precursor lesions and in biliary cancers. Oncogene. 2002;21:4301–4306. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1205533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schwarz LC, et al. Loss of growth factor dependence and conversion of transforming growth factor-beta 1 inhibition to stimulation in metastatic H-ras-transformed murine fibroblasts. Cancer Res. 1988;48:6999–7003. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Filmus J, et al. Development of resistance mechanisms to the growth-inhibitory effects of transforming growth factor-beta during tumor progression. Curr Opin Oncol. 1993;5:123–129. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kretzschmar M, et al. A mechanism of repression of TGFbeta/Smad signaling by oncogenic Ras. Genes Dev. 1999;13:804–816. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.7.804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Li J, et al. PTEN, a putative protein tyrosine phosphatase gene mutated in human brain, breast, and prostate cancer. Science. 1997;275:1943–1947. doi: 10.1126/science.275.5308.1943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Steck PA, et al. Identification of a candidate tumour suppressor gene, MMAC1, at chromosome 10q23.3 that is mutated in multiple advanced cancers. Nat Genet. 1997;15:356–362. doi: 10.1038/ng0497-356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Maehama T, et al. The tumor suppressor, PTEN/MMAC1, dephosphorylates the lipid second messenger, phosphatidylinositol 3,4,5-trisphosphate. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:13375–13378. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.22.13375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Di Cristofano A, et al. The multiple roles of PTEN in tumor suppression. Cell. 2000;100:387–390. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80674-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Simpson L, et al. PTEN: life as a tumor suppressor. Exp Cell Res. 2001;264:29–41. doi: 10.1006/excr.2000.5130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liaw D, et al. Germline mutations of the PTEN gene in Cowden disease, an inherited breast and thyroid cancer syndrome. Nat Genet. 1997;16:64–67. doi: 10.1038/ng0597-64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Marsh DJ, et al. Germline mutations in PTEN are present in Bannayan-Zonana syndrome. Nat Genet. 1997;16:333–334. doi: 10.1038/ng0897-333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Huang SC, et al. Genetic heterogeneity in familial juvenile polyposis. Cancer Res. 2000;60:6882–6885. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Carethers JM. Unwinding the heterogeneous nature of hamartom-atous polyposis syndromes. JAMA. 2005;294:2498–2500. doi: 10.1001/jama.294.19.2498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dong JT, et al. PTEN/MMAC1 is infrequently mutated in pT2 and pT3 carcinomas of the prostate. Oncogene. 1998;17:1979–1982. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1202119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sakurada A, et al. Infrequent genetic alterations of the PTEN/MMAC1 gene in Japanese patients with primary cancers of the breast, lung, pancreas, kidney, and ovary. Jpn J Cancer Res. 1997;88:1025–1028. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.1997.tb00324.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Li DM, et al. TEP1, encoded by a candidate tumor suppressor locus, is a novel protein tyrosine phosphatase regulated by transforming growth factor beta. Cancer Res. 1997;57:2124–2129. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ebert MP, et al. Reduced PTEN expression in the pancreas overexpressing transforming growth factor-beta 1. Br J Cancer. 2002;86:257–262. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6600031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Feig LA, et al. Inhibition of NIH 3T3 cell proliferation by a mutant ras protein with preferential affinity for GDP. Mol Cell Biol. 1988;8:3235–3243. doi: 10.1128/mcb.8.8.3235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sano T, et al. Differential expression of MMAC/PTEN in glioblastoma multiforme: relationship to localization and prognosis. Cancer Res. 1999;59:1820–1824. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hjelmeland AB, et al. Loss of phosphatase and tensin homologue increases transforming growth factor beta-mediated invasion with enhanced SMAD3 transcriptional activity. Cancer Res. 2005;65:11276–11281. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-3016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Goel A, et al. Frequent inactivation of PTEN by promoter hypermethylation in microsatellite instability-high sporadic colorectal cancers. Cancer Res. 2004;64:3014–3021. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.can-2401-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ijichi H, et al. Smad4-independent regulation of p21/WAF1 by transforming growth factor-beta. Oncogene. 2004;23:1043–1051. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fink SP, et al. TGF-beta-induced nuclear localization of Smad2 and Smad3 in Smad4 null cancer cell lines. Oncogene. 2003;22:1317–1323. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Vazquez F, et al. Phosphorylation of the PTEN tail regulates protein stability and function. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:5010–5018. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.14.5010-5018.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]