Abstract

Immunization with effective cancer vaccines can offer a much needed adjuvant therapy to fill the treatment gap after liver resection to prevent relapse of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). However, current HCC cancer vaccines are mostly based on native shared-self/tumor antigens that are only able to induce weak immune responses. In this study, we investigated whether the HCC-associated self/tumor antigen of alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) could be engineered to create an effective vaccine to break immune tolerance and potently activate CD8 T cells to prevent clinically relevant carcinogen-induced autochthonous HCC in mice. We found that the approach of computer-guided methodical epitope-optimization created a highly immunogenic AFP and that immunization with lentivector expressing the epitope-optimized AFP, but not wild-type AFP, potently activated CD8 T cells. Critically, the activated CD8 T cells not only cross-recognized short synthetic wild-type AFP peptides, but also recognized and killed tumor cells expressing wild-type AFP protein. Immunization with lentivector expressing optimized AFP, but not native AFP, completely protected mice from tumor challenge and reduced the incidence of carcinogen-induced autochthonous HCC. In addition, prime-boost immunization with the optimized AFP significantly increased the frequency of AFP-specific memory CD8 T cells in the liver that were highly effective against emerging HCC tumor cells, further enhancing the tumor prevention of carcinogen-induced autochthonous HCC. Our data demonstrate that epitope-optimization is required to break immune tolerance and potently activate AFP-specific CD8 T cells, generating effective antitumor effect to prevent clinically relevant carcinogen-induced autochthonous HCC in mice. Our study provides a practical roadmap to develop effective human HCC vaccines that may result in an improved outcome compared to the current HCC vaccines based on wild-type AFP.

Keywords: CD8 T cell response, lentivector, vaccinia vector, prime-boost, immune prevention

Introduction

Liver cancer is the 5th most common cancer and the 3rd most common cause of cancer death in the world (1). In the United States, the incidence of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), the most common type of liver cancer, has almost tripled over the past two decades to an estimated 24,500 new cases in 2013 (American Cancer Society). Although HBV vaccines have reduced HBV infections, and will decrease HBV-associated HCC in the long run (2), the large pool of existing HBV (350 million) (3) and HCV (170 million) (4) patients, and the recent recognition that obesity/diabetes has become the major risk factor of HCC in US (5) suggest that HCC incidence will continue increasing. Unfortunately, treatment options for HCC are limited, which contributes to the dismal 17% 3-year survival rate (1). Liver resection and transplantation are curative for small tumors, but the lack of post-surgery adjuvant therapies becomes a critical barrier to the success of liver resection, resulting in a 5-year recurrence rate of ~70% (6). Thus, there is an urgent need to develop novel approaches for HCC treatments.

One approach is to enlist a patient’s own immune system to fight HCC and guard against recurrence (7, 8). Alpha-fetoprotein (AFP), which is re-expressed in ~73% (9) of HCC, was identified as a target for T cell-mediated immunotherapy (8, 10–13). In animal model, mouse wild-type AFP (wt-AFP) in the form of DNA, viral vectors, or dendritic cells has been utilized to induce AFP-specific immune responses (11, 13–15). However, only a relatively low level of immune activation was detected, and a weak or modest antitumor effect was observed. For example, three immunizations with dendritic cells expressing mouse wt-AFP only protected 1 out of 4 mice from AFP+ tumor challenge (11). Xenogenic AFP (16) or a combination of AFP with heat shock protein (17, 18) or stimulatory cytokines (19) was employed to enhance the AFP-specific responses with marginal success. In addition, the potency of these immunizations and mechanisms of response are difficult to gauge because of the lack of identified H-2b-restricted AFP epitopes. In human studies, HLA-A2-restricted human AFP epitopes have been identified in HLA-A2 transgenic mice and in cultured human CD8 T cells (12, 20). However, the HCC vaccines based on native AFP peptides failed to generate a significant antitumor effect in clinical trials (10, 21). Thus, there is a clear demand to improve the efficacy of AFP-based HCC vaccines.

Previous studies demonstrated that immunization with native shared-self/tumor antigens is usually unable to break tolerance (22–24). Consistent with this, vaccinia vector (vv) expressing murine wt-AFP was incapable of inducing AFP-specific CD8 responses in mice (25). Recent study found that DNA encoding epitope-optimized melanoma antigen could break tolerance and activate CD8 T cells (22). Furthermore, lentivector (lv) expressing optimized melanoma antigen stimulated ~10% of circulating CD8 T cells to become melanoma-specific effector cells (23). Thus, epitope-optimization is a valid approach to increase the immunogenicity of shared-self/tumor antigens to break tolerance and induce potent immune responses.

In the current study, we investigated whether epitope-optimization of murine AFP and lv-mediated genetic immunization (26) could break tolerance and induce potent AFP-specific CD8 responses to generate a significant antitumor effect in an autochthonous HCC model. We found that lv expressing epitope-optimized murine AFP (opt-AFP), but not wt-AFP, potently activated AFP-specific CD8 T cells, which, critically, not only cross-recognized wt-AFP short peptides, but also recognized and killed wt-AFP+ tumor cells. The mice immunized with lv expressing opt-AFP, but not wt-AFP, were completely protected from AFP+ tumor challenge. Importantly, immunization with opt-AFP, but not wt-AFP, increased liver infiltration of AFP-specific CD8 cells and prevented carcinogen-induced autochthonous HCC. In addition, prime-boost immunization with opt-AFP, but not wt-AFP, further increased liver infiltration of AFP-specific CD8 memory cells that could detect and respond to evolving HCC tumor cells, enhancing the prevention of autochthonous HCC. Our data demonstrate that genetic immunization with epitope-optimized opt-AFP is able to break tolerance and induce potent AFP-specific CD8 responses to prevent mouse autochthonous HCC, providing a roadmap to create effective human HCC vaccines that may have a better chance of success than the current wt-AFP-based vaccines to prevent HCC relapse after liver resection and de novo development in high-risk populations.

Materials and Methods (Details are in Supplement)

Mice and murine autochthonous HCC model

C57BL/6 and C3H mice were from the NCI-Frederick (Frederick, MD) and maintained under specific pathogen-free conditions at Laboratory Animal Services of Georgia Regents University. Autochthonous HCC was induced in male F1 mice of C57BL/6XC3H as described (15, 27). Animal protocols were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Design of opt-AFP, viral vector preparation, and immunization

The mouse wt-AFP protein sequence was analyzed by EpitOptimizer program (28). Ten putative CD8 epitopes were optimized to increase their affinity to H-2Db and H-2Kb and create opt-AFP. Asparagines at positions 247, 325, and 498 were converted into glutamines to remove glycosylation sites that may hinder antigen processing (22). Lvs (wt-AFP-lv and opt-AFP-lv) were prepared and titrated as described (29) and their expression of wt-AFP and opt-AFP proteins was confirmed (Fig.S1). For immunization, 1.5X107 transduction units of lv were injected subcutaneously. Vv were constructed as described (30, 31) and 1.0X107 pfu were injected intraperitoneally for boosting immunization.

MHC I stabilization assay

The MHC stabilization assay was conducted as described (32).

Intracellular staining (ICS) of IFNγ

ICS of IFNγ was conducted as we described (23). To detect cytokine production by liver infiltrating CD8 T cells, the immune cells were first enriched by Percoll gradients (33).

Tetramer staining

The liver single cell suspension was enriched with Percoll gradient and stained with AFP212-Db tetramer and CD8 as described (30).

In vitro CTL assays

The in vitro CTL assay was performed as reported (34) and the specific killing was calculated (29).

Hematoxylin-Eosin (HE) and Ki67 staining

The liver histology was examined by HE staining and the proliferation status of liver and tumor were determined by Ki67 staining (27).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using the t-test or ANOVA (GraphPad Inc, La Jolla, CA).

Results

Putative wt-AFP epitopes are optimized to increase H-2b binding affinity

AFP has been studied as a target for HCC immunotherapy in mouse model by several groups (11, 13–15, 17, 19). However, the lack of defined H-2b restricted epitopes in the commonly used C57BL/6 strain has limited research progress in developing AFP-based cancer vaccines. In this study, using an algorithmic program, we identified 10 putative H-2b restricted CD8 epitopes (Table 1). Importantly, this program also provided the optimized epitopes that increased virtual MHC binding scores by 10–100 times.

Table I.

The amino acid sequences and the virtual binding scores of mouse native wt-AFP epitopes and their optimized opt-AFP counterparts.

| Kb- Restricted | Db- Restricted | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| wt-mAFP | opt-mAFP | wt-mAFP | opt-mAFP | ||||||

| Epitope | AA Sq | Score | AA Sq | Score | Epitope | AA Sq | Score | AA Sq | Score |

| 168 | FMYAPAIL | 66 | FMYAYAIL | 2640 | 152 | AVFMNRFIY | 15 | AVFNNRFIL | 2149 |

| 411 | SCALYQTL | 264 | SCYLYQTL | 2640 | 178 | AAQYDKVVL | 18 | AAQYNKVVL | 1789 |

| 419 | GDYKLQNL | 86 | GDMYQNL | 2880 | 212 | GSMLNEHVC | 82 | GSMLNEHVM | 1641 |

| 499 | SSYSNRRL | 66 | SSYSYRRL | 2640 | 285 | CSQQNILSS | 25 | CSQQNILSL | 3437 |

| 567 | VTADFSGL | 158 | VTYDFSGL | 1584 | 421 | YKLQNLFLI | 80 | YMYQNLFLI | 1394 |

The underlined and bolded letters indicate the changed amino acids in the optimized epitopes. AA Sq: Amino Acid Sequences.

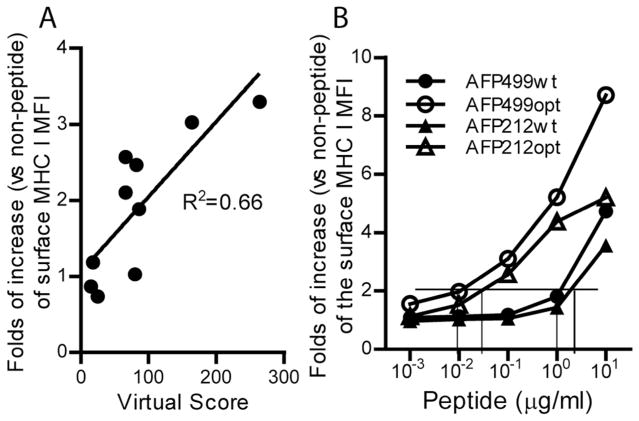

The actual MHC binding data of each putative wt-AFP epitope was determined by MHC stabilization assay. Overall, the virtual MHC binding scores predicted by computer correlated well to the actual binding data (Fig.1A). In addition, our data showed that the optimized AFP212opt and AFP499opt peptides could effectively stabilize the MHC I molecules at 50–100 times lower concentration compared to wt-AFP peptides of AFP212wt and AFP499wt (Fig.1B), suggesting that epitope-optimization indeed significantly increases the affinity of AFP CD8 epitopes to H-2b molecules.

Fig. 1.

(A) Correlation of virtual MHC binding scores of wt-AFP CD8 epitopes and the actual data of MHC stabilization assay. The actual binding data is obtained with 10Og/ml of peptides in the stabilization assay. (B) Comparison of the MHC stabilization data of two pairs of mouse wt-AFP (AFP212wt and AFP499wt) and opt-AFP (AFP212opt and AFP499opt) peptides. The MHC stabilization data is presented as the fold of increase of the H-2b molecule on the surface of RMA-S cells in the presence of peptides over cells cultured in the absence of peptides. The assay was repeated three times with similar results. Vertical lines indicate the concentration of wt-AFP and opt-AFP peptides required to increase the surface H-2b level by 2-fold. MFI: mean fluorescent intensity.

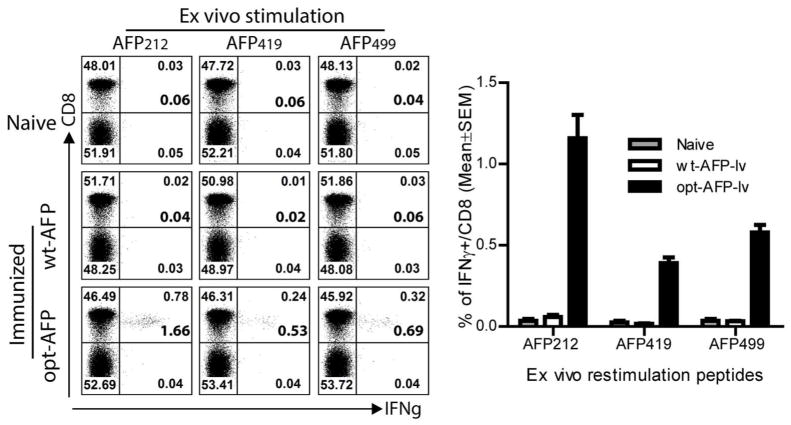

Opt-AFP-lv, but not wt-AFP-lv, breaks tolerance and effectively activates AFP-specific CD8 T cells that can cross-recognize wt-AFP short epitopes

To test if the computer-designed opt-AFP could break tolerance and induce more potent CD8 responses than wt-AFP, we chose the approach of lv-mediated genetic immunization because it effectively stimulates CD8 responses (26, 35–37). Twelve days after immunization, the CD8 responses were examined. No IFNγ-producing CD8 cells were detected in the control and wt-AFP-lv immunized mice after ex vivo re-stimulation with any of the 10 AFP epitopes (Fig.2 and Fig.S2). In contrast, a significant proportion of CD8 T cells from the opt-AFP-lv immunized mice were able to produce IFNγ after stimulation with three wt-AFP peptides, AFP212, AFP419, and AFP499. As high as 1.66% of spleen CD8 T cells produced IFNγ after AFP212 peptide stimulation. In addition, in vivo cytolytic activity was only detected in the opt-AFP-lv immunized mice (Fig.S3). These data indicate that epitope-optimization of AFP is required to break immune tolerance and effectively activate AFP-specific CD8 T cells, which, importantly, are able to cross-recognize wt-AFP epitopes.

Fig. 2.

Epitope-optimization of AFP is required to break tolerance and activates AFP-specific CD8 T cells. Representative dot plots of ICS of IFNγ after ex vivo stimulation with wt-AFP CD8 epitopes are presented. Only the Thy1.2+ T cells are gated and shown. The number at the bottom corner of up-right quadrant is the calculated percentage of IFNγ+ cell out of CD8 T cells. A summary of data from 6 mice in two experiments is also shown. Non-paired t-test was used for statistical analysis. This experiment was repeated at least 5 times with similar results.

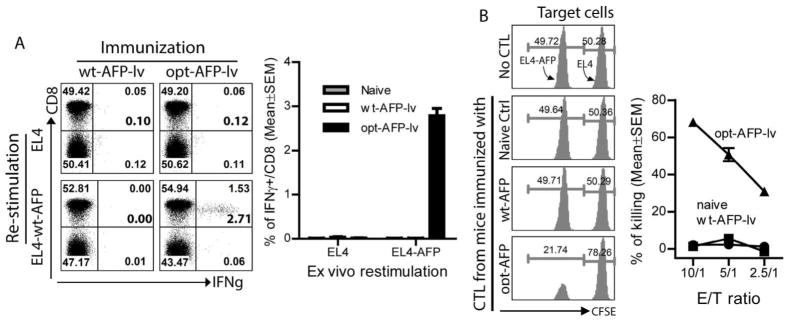

The CD8 T cells activated by opt-AFP can recognize and effectively kill tumor cells that naturally process and present wt-AFP peptides

We next determined whether the CD8 T cells activated by opt-AFP could recognize native wt-AFP epitopes that are naturally processed and presented on AFP-expressing tumor cells. Because the available B6 mouse HCC cell line, Hepa1-6, is MHC I negative even after IFNγ treatment, we utilized EL4-AFP tumor cells as surrogate target cells, similar to previous studies (11). We found that ~2.7% of spleen CD8 T cells from the opt-AFP-lv immunized mice produced high level of IFNγ after co-culture with EL4-AFP, but not parental EL4, tumor cells, (Fig.3A). In contrast, no IFNγ-producing CD8 T cells were detected in the wt-AFP-lv immunized mice. Importantly, the spleen CD8 T cells from opt-AFP-lv, but not wt-AFP-lv, immunized mice could effectively kill EL4-AFP target tumor cells in vitro (Fig. 3B), consistent with the in vivo killing data (Fig.S3). Even at the low effector/target ratio of 10:1, ~70% of EL4-AFP target cells were killed and eliminated within 6 hours. These data strongly suggest that the CD8 T cells activated by opt-AFP can recognize and efficiently kill tumor cells expressing native wt-AFP, but also supports the hypothesis that the AFP CD8 epitopes identified in this study are presented by AFP+ tumor cells, making them recognizable by the opt-AFP-activated CD8 T cells.

Fig. 3.

CD8 T cells activated by opt-AFP recognize naturally processed and presented wt-AFP CD8 epitopes on EL4-AFP tumor cells and effectively kill them. (A) Splenocytes from mice immunized with opt-AFP-lv, but not wt-AFP-lv, are able to recognize EL4-AFP tumor cells and produce IFNγ. One set of representative dot plots and a summary data of 6 mice from two experiments are shown. The number at the bottom corner of up-right quadrant represents the calculated percentage of IFNγ+ cells out of total CD8 T cells. (B) Splenocytes from the opt-AFP-lv, but not wt-AFP-lv, immunized mice are able to kill EL4-AFP target cells. CFSE labeled EL4 and EL4-AFP tumor cells are indicated. One set of histograms at effector/target ratio of 10 are shown. A summary of the in vitro CTL data at the indicated E/T ratio is also shown. E/T: effector/target. The experiment was repeated three times with similar results.

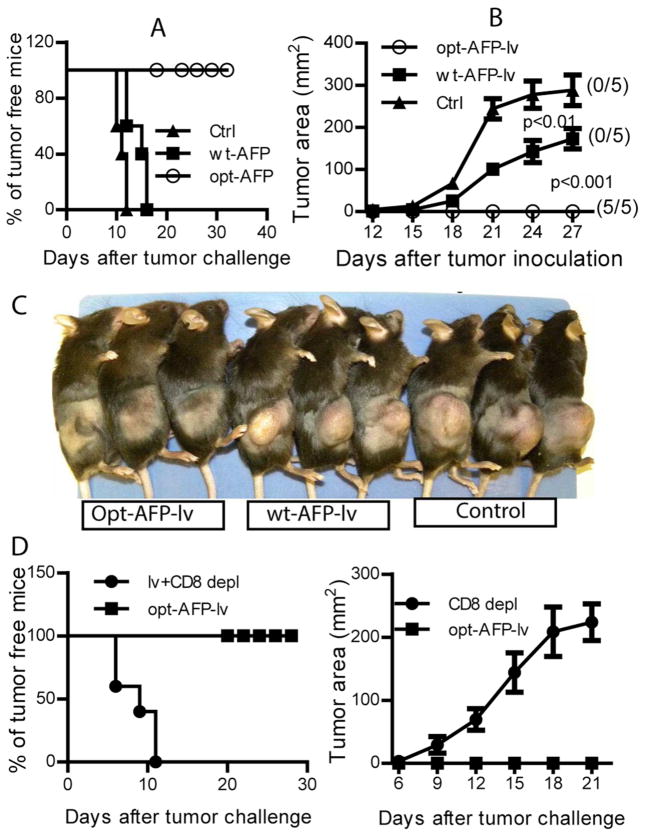

Opt-AFP-lv, but not wt-AFP-lv, immunization completely protects mice from AFP+ tumor cell challenge in a CD8-dependent manner

To study if the CD8 T cells activated by opt-AFP could recognize and kill wt-AFP epitopes naturally processed and presented on tumor cells in vivo, we challenged the immunized mice with EL4-AFP tumor cells. Compared to naïve mice, wt-AFP-lv immunization did not protect mice from tumor challenge although tumor growth was slowed (Fig.4A), a limited antitumor effect of wt-AFP similar to previous report (11). In contrast, one single immunization of opt-AFP-lv completely protected mice from lethal dose of EL4-AFP tumor challenge (Fig.4A), suggesting that opt-AFP markedly improved the antitumor effect over wt-AFP. To determine if the antitumor effect of opt-AFP-lv immunization was indeed mediated by the activated CD8 T cells, we depleted CD8 T cells two days prior to tumor challenge. CD8 depletion completely abolished the antitumor effect of opt-AFP-lv with all mice rapidly developing tumors (Fig. 4D), indicating that the CD8 T cells activated by opt-AFP-lv played a critical role in the prevention of AFP+ tumor cell challenge, consistent with previous findings (11).

Fig. 4.

Immunization with opt-AFP-lv, but not wt-AFP-lv, prevents challenge by EL4-AFP in a CD8-dependent manner. (A & B) Percentage of tumor-free mice (A) and the tumor growth curve (B). The number in the parentheses indicates the number of tumor-free mice out of a total 5 mice. Two-way ANOVA was used to conduct statistical analysis. (C). Tumor-bearing condition at the time of sacrifice is shown. This experiment was repeated twice with similar results. (D) Antitumor effect of opt-AFP-lv immunization is dependent on CD8 T cells. Both the tumor-bearing status and tumor growth are presented.

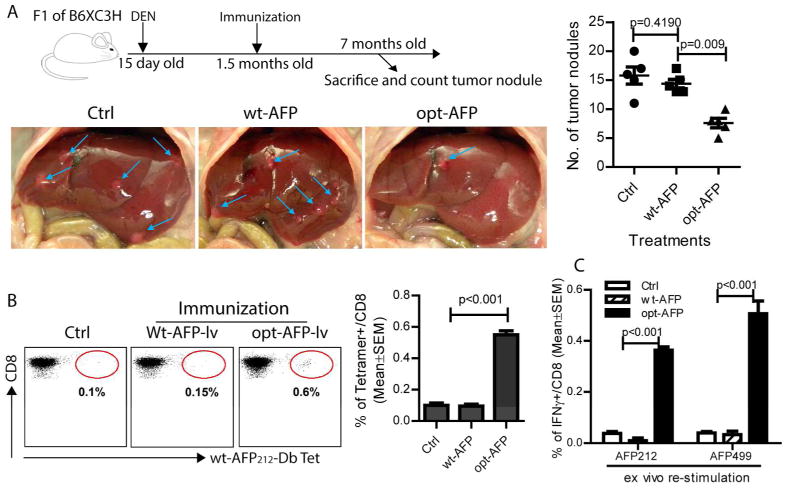

Opt-AFP-lv, but not wt-AFP-lv, immunization significantly reduces the tumor burden of autochthonous HCC and increases liver infiltration of functional AFP-specific CD8 T cells

We then studied the antitumor effect of opt-AFP-lv immunization in the clinically relevant DEN-induced autochthonous HCC model. Our data showed that opt-AFP-lv, but not wt-AFP-lv, immunization significantly reduced the tumor nodule number of DEN-induced autochthonous HCC (Fig.5A). Immunological analysis showed that, compared to wt-AFP-lv, opt-AFP-lv immunization significantly increased the liver infiltration of AFP-specific CD8 T cells (Fig. 5B). Importantly, these liver-infiltrated CD8 T cells were functional, producing IFNγ in response to native wt-AFP peptide stimulation (Fig.5C).

Fig. 5.

One single immunization with opt-AFP-lv, but not wt-AFP-lv, significantly reduces the number of DEN-induced autochthonous HCC tumor nodules and increases the liver infiltration of functional AFP-specific CD8 T cells. (A) Experimental scheme. Mice were sacrificed at the age of 7 months. The liver was photographed and the tumor nodules on the liver surface were counted. Blue arrows indicate the tumor nodules. A summary of combined data from two independent experiments is also presented. (B) Increase of AFP-specific CD8 T cells in the liver of opt-AFP-lv immunized mice. Representative dot plots of the AFP212-Db tetramer staining and a summary of data are presented. (C) Liver infiltrating CD8 from the opt-AFP-lv, but not wt-AFP-lv, immunized mice produced effector cytokines in response to ex vivo stimulation by two native wt-AFP peptides. A summary data of 5 mice in two experiments is shown.

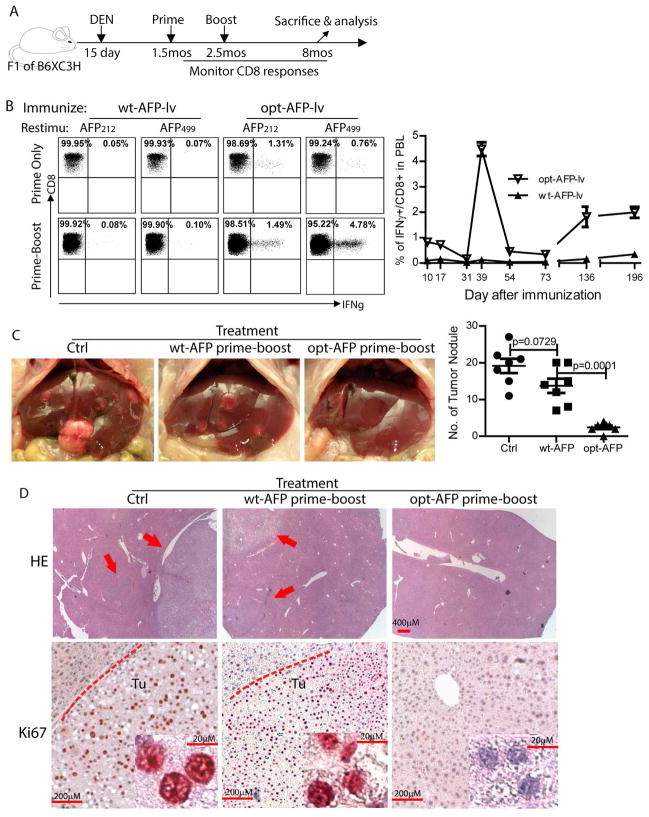

Prime-boost with opt-AFP, but not wt-AFP, increases the AFP-specific CD8 response and antitumor effect in the autochthonous HCC model

To improve the antitumor effect of opt-AFP-lv, we utilized a prime-boost strategy to increase the magnitude of AFP-specific CD8 responses (Fig.6A). The primary CD8 responses in the F1 mice (Fig. 6B) were similar to that in B6 mice (Fig.2). The wt-AFP-lv and wt-AFP-vv prime-boost immunization did not activate AFP-specific CD8 responses (Fig. 6B). In contrast, opt-AFP-lv and opt-AFP-vv prime-boost markedly enhanced the AFP212 and AFP499 specific CD8 effector responses (Fig.6B). The mean fluorescent intensity of IFNγ in the prime-boosted mice was also significantly higher than in the lv-prime alone (6200 vs 2100), suggesting that the amount of IFNγ produced is significantly more. The kinetics data showed that AFP-specific CD8 responses returned to baseline two months after the boost. Surprisingly, the AFP-specific CD8 T cell responses were markedly increased again at the age of 6 months and remained at high level until the time of sacrifice at 8 months of age (Fig 6B). The opt-AFP prime-boosted mice showed a significantly low number of HCC tumor nodules compared to wt-AFP prime-boosted mice (Fig.6C). Some livers were free of HCC tumors even microscopically (Fig.6D). Furthermore, while tumor nodules were found in the highly proliferative state by Ki67 staining in the livers of control or wt-AFP immunized mice, no obvious Ki67 were found in the liver treated with opt-AFP-lv prime and opt-AFP-vv boost (Fig.6D).

Fig. 6.

Opt-AFP, but not wt-AFP, prime-boost increases effector and memory CD8 responses and enhances tumor prevention effect in autochthonous HCC model. (A) Experimental scheme (mos: months). (B) Representative dot plot of ICS of IFNγ at 12 days after lv prime or 7 days after vv boost. The kinetics demonstrates a dramatic re-appearance of AFP499 CD8 responses in the mice immunized with opt-AFP, but not wt-AFP, at the age of 6 months. (C) Significant reduction of tumor nodules of autochthonous HCC by prime-boost with opt-AFP, but not wt-AFP. Representative liver pictures and a summary of HCC tumor nodules of two experiments are presented. (D) Representative liver histology after HE and Ki67 staining. HE pictures are taken at the lowest magnification of 2.5x (scale bar: 400mm) to cover a large area. The arrows indicate the tumors in the liver. Tu: tumor. The dashed lines indicate the tumors (scale bar: 200mm). Insets are the high magnification (40x) (scale bar: 20mm).

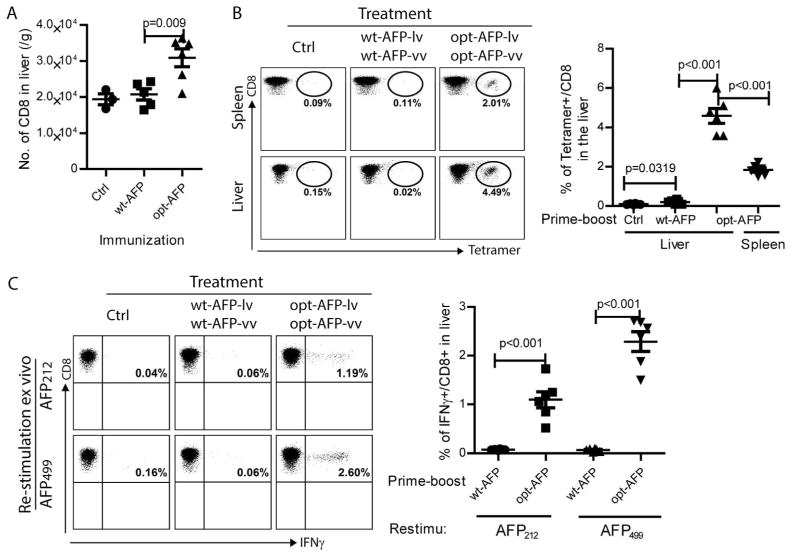

Prime-boost with opt-AFP, but not wt-AFP, markedly increases the liver infiltration of functional AFP-specific CD8 T cells

The CD8 infiltration in the liver after prime-boost immunization was also examined. We found that the liver from the opt-AFP prime-boosted mice contained a significantly higher number of total CD8 T cells compared to control or wt-AFP immunized livers (Fig.7A). Importantly, the opt-AFP prime-boosted livers were infiltrated with a significantly higher percent of AFP-specific CD8 T cells (Fig.7B). In addition, compared to opt-AFP-lv immunization alone (Fig. 5B), the prime-boost immunization markedly increased the proportion of AFP-specific CD8 T cells in the liver. Approximately 4.5% of the liver-infiltrated CD8 T cells were AFP212 specific CD8 T cells by AFP212-Db tetramer staining. Furthermore, compared to spleen, the percentage of AFP212 specific CD8 T cells was significantly higher. No AFP-specific CD8 T cells were found in the liver of wt-AFP prime-boosted mice, suggesting that epitope-optimization is required to activate CD8 T cells to infiltrate into liver tissue. The opt-AFP activated CD8 T cells in liver were functional, producing a high amount of IFNγ in response to AFP212 or AFP499 peptide stimulation (Fig.7C). Compared to lv immunization alone (Fig.5C), the percentage of CD8 T cells in the liver and the amount of IFNγ produced by liver CD8 T cells were significantly higher (Fig.7C). For example, 0.5% of CD8 T cells in lv primed liver vs 2.6% in the prime-boosted liver produced IFNγ in response to wt-AFP499 stimulation. Again, prime-boost immunization with wt-AFP-lv and wt-AFP-vv did not generate a measurable number of IFNγ-producing CD8 T cells in the liver, further suggesting that creation of highly immunogenic AFP by epitope-optimization is required in order to activate and increase liver infiltration of functional AFP-specific CD8 T cells to prevent autochthonous HCC in the DEN-treated mice.

Fig. 7.

Opt-AFP, but not wt-AFP, lv-vv prime-boost immunization increases liver infiltration of functional AFP-specific CD8 T cells. (A) Absolute number of total CD8 T cells in the liver. (B) Tetramer staining of AFP212 specific CD8 T cells in liver and spleen. Representative dot plots show the percentage of AFP212 specific CD8 T cells. A summary data of 6 mice from two experiments is also presented. (C) Cytokine production of liver infiltrating CD8 T cells after stimulation with wt-AFP peptides. Representative dot plots and a summary of data are shown.

Discussion

Most studies show that native wt-AFP induces weak AFP-specific responses and fails to generate a sufficient antitumor effect because of the immune tolerance imposed on the shared-self/tumor antigens. To our knowledge, there has been only one report showing that a peptide sequence mutation in the human AFP542 epitope enhances the CD8 responses but there is no investigation of antitumor effects (38). Here, we systematically studied whether epitope-optimization could increase the immunogenicity of AFP and if immunization with lv encoding epitope-optimized opt-AFP could enhance AFP-specific responses. One major finding of the present study is that creation of epitope-optimized opt-AFP is required to break tolerance and effectively activate AFP-specific CD8 T cells. Once activated, however, these CD8 T cells could efficiently cross-recognize wt-AFP epitopes, allowing us to identify three novel H-2b restricted CD8 epitopes. All three wt-AFP epitopes have an intermediate affinity for H-2b molecules, in agreement with the theory that T cells against the highest and lowest affinity antigens are deleted through positive and negative selection (39).

To break immune tolerance, altered peptide ligand (APL) has been extensively studied to activate CD8 T cells against self/tumor antigens (24, 40–42) because of the enhanced stability of APL and MHC complex (43) even though a recent study found that changes in the MHC binding residues minimally affect the stability (44). However, the CD8 T cells activated by APL may not be able to efficiently cross-recognize the corresponding native epitopes (45). In addition, the T cell repertoire may be skewed (46) and the quality of clonotypic T cells may be suboptimal (47) in generating antitumor effect in APL immunization. Furthermore, some of the synthetic short peptide epitopes predicted by computer may not be indeed naturally processed and presented by target tumor cells (20). These drawbacks of APL may explain why recent APL clinical trials failed to show a significant antitumor effect (48). Data from this study and previous reports in melanoma antigen (22, 23) demonstrate that genetic vaccines encoding full-length epitope-optimized antigen may have several advantages. First, the antigen expressed from genetic vaccine and synthesized inside antigen-presenting cells will likely go through the same processing and presentation pathway as the native antigen expressed in target tumor cells. Unlike an exogenously pulsed short peptide, this better recapitulates natural antigen processing and presentation. Consistent with this hypothesis, the CD8 T cells activated by opt-AFP-lv immunization were able to effectively recognize and kill EL4-AFP tumor cells expressing native wt-AFP (Fig.3). Secondly, the full-antigen based approach offers a much broader immune response than shorter APL. Furthermore, lv expressing full-length optimized AFP allows us to examine the immune responses of multiple AFP epitopes in one single immunization, facilitating identification and verification of each individual epitope. Thus, epitope-optimization together with genetic immunization represents an effective approach for activating immune responses against shared-self/tumor antigens to generate a significant antitumor effect. However, the principle of epitope-optimization to increase antigen immunogenicity in genetic immunization setting is the same as in APL. Thus, the success of the epitope-optimized genetic vaccines may still depend on trials and errors, and the quality of activated T cells may vary case-by-case. Recent investigation of the TCR-optimized (or both MHC and TCR optimized) peptides (46) may shed some light on designing APL and epitope-optimized genetic vaccines to activate high quality T cells to recognize native epitopes.

The inability of detecting AFP-specific CD8 responses after wt-AFP-lv immunization in our study seems contradictory to the conclusion of CD8 activation by wt-AFP made in previous studies (11, 15). However, the discrepancy is likely due to the different assays employed. In our study, we used ICS of IFNγ after a short 3-hour ex vivo stimulation to directly measure the in vivo level of AFP-specific CD8 T cells instead of using an ELISPOT assay after 24 hours (15) or 48 hours (11) of in vitro stimulation, which is more sensitive (49). However, the antitumor protection in ¼ of the immunized mice from EL4-AFP tumor challenge (with retardation of tumor growth in the rest) observed in previous study (11), is comparable to the limited antitumor effect observed here with our wt-AFP-lv immunization (Fig.4B). Thus, we conclude that wt-AFP-lv may weakly activate AFP-specific CD8 T cells and that epitope-optimization of AFP is needed in order to induce potent AFP-specific CD8 responses and generate a much more significant antitumor effect. Interestingly, immunization with wt-AFP DNA vaccines formulated with a cationic polymer (15) resulted in remarkable reduction of tumor development in the DEN-induced autochthonous HCC model despite of the AFP-specific CD8 responses being relatively weak. It is possible that humoral responses may play an important role in that study since DNA immunization via intramuscular route is known to be effective for antibody response induction (50).

To prevent autochthonous HCC, the vaccine-activated CD8 T cells need to infiltrate into and constantly surveil the liver tissue to detect and respond to newly evolved AFP expressing tumor cells. The longitudinal study of the AFP-specific CD8 responses in DEN-treated mice reveals one important finding, i.e., the marked re-appearance and increase of AFP-specific CD8 cells at the age of 6 months in the prime-boosted mice (Fig.6B), which may coincide with the evolution and emergence of AFP+ HCC tumor cells in the DEN–treated liver. The spike of AFP-specific CD8 responses at the age of 6 months in the DEN-treated mice also suggest that the AFP-specific memory CD8 T cells induced by vaccines may detect AFP antigen in the liver and respond by expansion, which then control autochthonous HCC growth. The higher percentage of AFP-specific CD8 T cells in the liver than in the spleen (Fig.7B) suggests that AFP-specific CD8 T cells are preferentially recruited into liver tissue, or may simply reflect the fact that the AFP-specific CD8 memory T cells respond to the emerging HCC tumor cells in the liver by expansion and are retained in the liver tissue because of the constant emerging AFP antigen. Further studies are needed to clarify this important question.

In summary, we have demonstrated a practical approach to break tolerance and enhance AFP-specific CD8 responses to achieve a much stronger antitumor effect in a clinically relevant autochthonous HCC model, which has a great potential to be translated into the development of novel human HCC vaccines to prevent HCC relapse after surgery or to prevent HCC de novo development in high-risk populations.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Lei Huang, Georgia Regents University, for helping the MHC stabilization assay, NIH Tetramer Core Facility for synthesizing AFP212-Db tetramer, and Dr. Rhea Markowitz for editing the manuscript.

Grant support: Research in this study is supported by the Distinguished Investigator Fund from Georgia Research Alliance to Yukai He.

Abbreviations

- AFP

alpha-fetoprotein

- HCC

hepatocellular carcinoma

- wt

wild-type

- opt

optimized

- vv

recombinant vaccinia vector

- lv

recombinant lentivector

- DEN

diethylnitrosamine

- wt-AFP-lv

lv expressing mouse wt-AFP protein

- opt-AFP-lv

lv expressing mouse opt-AFP protein

- ICS

intracellular staining

References

- 1.Ferlay J, Shin HR, Bray F, Forman D, Mathers C, Parkin DM. Estimates of worldwide burden of cancer in 2008: GLOBOCAN 2008. Int J Cancer. 2010;127:2893–2917. doi: 10.1002/ijc.25516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chang MH, You SL, Chen CJ, Liu CJ, Lee CM, Lin SM, Chu HC, et al. Decreased incidence of hepatocellular carcinoma in hepatitis B vaccinees: a 20-year follow-up study. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2009;101:1348–1355. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djp288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wright TL. Introduction to chronic hepatitis B infection. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101 (Suppl 1):S1–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2006.00469.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sy T, Jamal MM. Epidemiology of hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection. Int J Med Sci. 2006;3:41–46. doi: 10.7150/ijms.3.41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Welzel TM, Graubard BI, Quraishi S, Zeuzem S, Davila JA, El-Serag HB, McGlynn KA. Population-attributable fractions of risk factors for hepatocellular carcinoma in the United States. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108:1314–1321. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2013.160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kao WY, Su CW, Chau GY, Lui WY, Wu CW, Wu JC. A comparison of prognosis between patients with hepatitis B and C virus-related hepatocellular carcinoma undergoing resection surgery. World J Surg. 2011;35:858–867. doi: 10.1007/s00268-010-0928-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pardee AD, Butterfield LH. Immunotherapy of hepatocellular carcinoma: Unique challenges and clinical opportunities. Oncoimmunology. 2012;1:48–55. doi: 10.4161/onci.1.1.18344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bei R, Mizejewski GJ. Alpha fetoprotein is more than a hepatocellular cancer biomarker: from spontaneous immune response in cancer patients to the development of an AFP-based cancer vaccine. Curr Mol Med. 2011;11:564–581. doi: 10.2174/156652411800615162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Liu C, Xiao GQ, Yan LN, Li B, Jiang L, Wen TF, Wang WT, et al. Value of alpha-fetoprotein in association with clinicopathological features of hepatocellular carcinoma. World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19:1811–1819. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v19.i11.1811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Butterfield LH, Ribas A, Meng WS, Dissette VB, Amarnani S, Vu HT, Seja E, et al. T-cell responses to HLA-A*0201 immunodominant peptides derived from alpha-fetoprotein in patients with hepatocellular cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2003;9:5902–5908. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vollmer CM, Jr, Eilber FC, Butterfield LH, Ribas A, Dissette VB, Koh A, Montejo LD, et al. Alpha-fetoprotein- specific genetic immunotherapy for hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Res. 1999;59:3064–3067. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Butterfield LH, Koh A, Meng W, Vollmer CM, Ribas A, Dissette V, Lee E, et al. Generation of human T-cell responses to an HLA-A2. 1-restricted peptide epitope derived from alpha-fetoprotein. Cancer Res. 1999;59:3134–3142. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Grimm CF, Ortmann D, Mohr L, Michalak S, Krohne TU, Meckel S, Eisele S, et al. Mouse alphafetoprotein- specific DNA-based immunotherapy of hepatocellular carcinoma leads to tumor regression in mice. Gastroenterology. 2000;119:1104–1112. doi: 10.1053/gast.2000.18157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Meng WS, Butterfield LH, Ribas A, Dissette VB, Heller JB, Miranda GA, Glaspy JA, et al. alpha-Fetoprotein-specific tumor immunity induced by plasmid prime-adenovirus boost genetic vaccination. Cancer Res. 2001;61:8782–8786. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cany J, Barteau B, Tran L, Gauttier V, Archambeaud I, Couty JP, Turlin B, et al. AFP-specific immunotherapy impairs growth of autochthonous hepatocellular carcinoma in mice. J Hepatol. 2011;54:115–121. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2010.06.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pang XH, Chen MS, Jia WH, Zhou XX. Inhibitory effects of human AFP-derived peptide-pulsed dendritic cells on mouse hepatocellular carcinoma. Ai Zheng. 2008;27:1233–1238. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lan YH, Li YG, Liang ZW, Chen M, Peng ML, Tang L, Hu HD, et al. A DNA vaccine against chimeric AFP enhanced by HSP70 suppresses growth of hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2007;56:1009–1016. doi: 10.1007/s00262-006-0254-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang X, Lin H, Wang Q. Specific genetic immunotherapy induced by recombinant vaccine alpha-fetoprotein-heat shock protein 70 complex. Physics Procedia. 2012;33:738–742. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rodriguez MM, Ryu SM, Qian C, Geissler M, Grimm C, Prieto J, Blum HE, et al. Immunotherapy of murine hepatocellular carcinoma by alpha-fetoprotein DNA vaccination combined with adenovirus-mediated chemokine and cytokine expression. Hum Gene Ther. 2008;19:753–759. doi: 10.1089/hum.2007.130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Butterfield LH, Meng WS, Koh A, Vollmer CM, Ribas A, Dissette VB, Faull K, et al. T cell responses to HLA-A*0201-restricted peptides derived from human alpha fetoprotein. J Immunol. 2001;166:5300–5308. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.8.5300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Butterfield LH, Ribas A, Dissette VB, Lee Y, Yang JQ, De la Rocha P, Duran SD, et al. A phase I/II trial testing immunization of hepatocellular carcinoma patients with dendritic cells pulsed with four alpha-fetoprotein peptides. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12:2817–2825. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-2856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Guevara-Patino JA, Engelhorn ME, Turk MJ, Liu C, Duan F, Rizzuto G, Cohen AD, et al. Optimization of a self antigen for presentation of multiple epitopes in cancer immunity. J Clin Invest. 2006;116:1382–1390. doi: 10.1172/JCI25591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liu Y, Peng Y, Mi M, Guevara-Patino J, Munn DH, Fu N, He Y. Lentivector immunization stimulates potent CD8 T cell responses against melanoma self-antigen tyrosinase-related protein 1 and generates antitumor immunity in mice. J Immunol. 2009;182:5960–5969. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0900008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Overwijk WW, Tsung A, Irvine KR, Parkhurst MR, Goletz TJ, Tsung K, Carroll MW, et al. gp100/pmel 17 is a murine tumor rejection antigen: induction of “self”-reactive, tumoricidal T cells using high-affinity, altered peptide ligand. J Exp Med. 1998;188:277–286. doi: 10.1084/jem.188.2.277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tran L, Judor JP, Gauttier V, Geist M, Hoffman C, Rooke R, Vassaux G, et al. The immunogenicity of the tumor-associated antigen alpha-fetoprotein is enhanced by a fusion with a transmembrane domain. J Biomed Biotechnol. 2012;2012:878657. doi: 10.1155/2012/878657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.He Y, Falo LD., Jr Lentivirus as a potent and mechanistically distinct vector for genetic immunization. Curr Opin Mol Ther. 2007;9:439–446. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jin X, Moskophidis D, Mivechi NF. Heat shock transcription factor 1 is a key determinant of HCC development by regulating hepatic steatosis and metabolic syndrome. Cell Metab. 2011;14:91–103. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2011.03.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Houghton CS, Engelhorn ME, Liu C, Song D, Gregor P, Livingston PO, Orlandi F, et al. Immunological validation of the EpitOptimizer program for streamlined design of heteroclitic epitopes. Vaccine. 2007;25:5330–5342. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2007.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.He Y, Zhang J, Mi Z, Robbins P, Falo LD., Jr Immunization with lentiviral vector-transduced dendritic cells induces strong and long-lasting T cell responses and therapeutic immunity. J Immunol. 2005;174:3808–3817. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.6.3808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Xiao H, Peng Y, Hong Y, Liu Y, Guo ZS, Bartlett DL, Fu N, et al. Lentivector prime and vaccinia virus vector boost generate high-quality CD8 memory T cells and prevent autochthonous mouse melanoma. J Immunol. 2011;187:1788–1796. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1101138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Guo ZS, Naik A, O’Malley ME, Popovic P, Demarco R, Hu Y, Yin X, et al. The enhanced tumor selectivity of an oncolytic vaccinia lacking the host range and antiapoptosis genes SPI-1 and SPI-2. Cancer Res. 2005;65:9991–9998. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-1630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Price GE, Ou R, Jiang H, Huang L, Moskophidis D. Viral escape by selection of cytotoxic T cell-resistant variants in influenza A virus pneumonia. J Exp Med. 2000;191:1853–1867. doi: 10.1084/jem.191.11.1853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hong Y, Peng Y, Mi M, Xiao H, Munn DH, Wang GQ, He Y. Lentivector expressing HBsAg and immunoglobulin Fc fusion antigen induces potent immune responses and results in seroconversion in HBsAg transgenic mice. Vaccine. 2011;29:3909–3916. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.03.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nakagawa Y, Watari E, Shimizu M, Takahashi H. One-step simple assay to determine antigen-specific cytotoxic activities by single-color flow cytometry. Biomed Res. 2011;32:159–166. doi: 10.2220/biomedres.32.159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.He Y, Zhang J, Donahue C, Falo LD., Jr Skin-derived dendritic cells induce potent CD8(+) T cell immunity in recombinant lentivector-mediated genetic immunization. Immunity. 2006;24:643–656. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.03.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Esslinger C, Chapatte L, Finke D, Miconnet I, Guillaume P, Levy F, MacDonald HR. In vivo administration of a lentiviral vaccine targets DCs and induces efficient CD8(+) T cell responses. J Clin Invest. 2003;111:1673–1681. doi: 10.1172/JCI17098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Arce F, Breckpot K, Collins M, Escors D. Targeting lentiviral vectors for cancer immunotherapy. Curr Cancer Ther Rev. 2011;7:248–260. doi: 10.2174/157339411797642605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Meng WS, Butterfield LH, Ribas A, Heller JB, Dissette VB, Glaspy JA, McBride WH, et al. Fine specificity analysis of an HLA-A2. 1-restricted immunodominant T cell epitope derived from human alpha-fetoprotein. Mol Immunol. 2000;37:943–950. doi: 10.1016/s0161-5890(01)00017-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Starr TK, Jameson SC, Hogquist KA. Positive and negative selection of T cells. Annu Rev Immunol. 2003;21:139–176. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.21.120601.141107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dyall R, Bowne WB, Weber LW, LeMaoult J, Szabo P, Moroi Y, Piskun G, et al. Heteroclitic immunization induces tumor immunity. J Exp Med. 1998;188:1553–1561. doi: 10.1084/jem.188.9.1553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Slansky JE, Rattis FM, Boyd LF, Fahmy T, Jaffee EM, Schneck JP, Margulies DH, et al. Enhanced antigen-specific antitumor immunity with altered peptide ligands that stabilize the MHC-peptide-TCR complex. Immunity. 2000;13:529–538. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)00052-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.van Stipdonk MJ, Badia-Martinez D, Sluijter M, Offringa R, van Hall T, Achour A. Design of agonistic altered peptides for the robust induction of CTL directed towards H-2Db in complex with the melanoma-associated epitope gp100. Cancer Res. 2009;69:7784–7792. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-1724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.van der Burg SH, Visseren MJ, Brandt RM, Kast WM, Melief CJ. Immunogenicity of peptides bound to MHC class I molecules depends on the MHC-peptide complex stability. J Immunol. 1996;156:3308–3314. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Miles KM, Miles JJ, Madura F, Sewell AK, Cole DK. Real time detection of peptide-MHC dissociation reveals that improvement of primary MHC-binding residues can have a minimal, or no, effect on stability. Mol Immunol. 48:728–732. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2010.11.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cole DK, Edwards ES, Wynn KK, Clement M, Miles JJ, Ladell K, Ekeruche J, et al. Modification of MHC anchor residues generates heteroclitic peptides that alter TCR binding and T cell recognition. J Immunol. 2010;185:2600–2610. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1000629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ekeruche-Makinde J, Clement M, Cole DK, Edwards ES, Ladell K, Miles JJ, Matthews KK, et al. T-cell receptor-optimized peptide skewing of the T-cell repertoire can enhance antigen targeting. J Biol Chem. 287:37269–37281. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.386409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Speiser DE, Baumgaertner P, Voelter V, Devevre E, Barbey C, Rufer N, Romero P. Unmodified self antigen triggers human CD8 T cells with stronger tumor reactivity than altered antigen. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:3849–3854. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0800080105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Filipazzi P, Pilla L, Mariani L, Patuzzo R, Castelli C, Camisaschi C, Maurichi A, et al. Limited Induction of Tumor Cross-Reactive T Cells without a Measurable Clinical Benefit in Early Melanoma Patients Vaccinated with Human Leukocyte Antigen Class I-Modified Peptides. Clin Cancer Res. 2012;18:6485–6496. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-12-1516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Letsch A, Scheibenbogen C. Quantification and characterization of specific T-cells by antigen-specific cytokine production using ELISPOT assay or intracellular cytokine staining. Methods. 2003;31:143–149. doi: 10.1016/s1046-2023(03)00124-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tang DC, DeVit M, Johnston SA. Genetic immunization is a simple method for eliciting an immune response. Nature. 1992;356:152–154. doi: 10.1038/356152a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.