Abstract

Purpose

The inverse relationship between cigarette smoking and endometrial carcinoma risk is well established. We examined effect modification of this relationship and associations with tumor characteristics in the National Institutes of Health–AARP Diet and Health Study.

Methods

We examined the association between cigarette smoking and endometrial carcinoma risk among 110,304 women. During 1,029,041 person years of follow-up, we identified 1,476 incident endometrial carcinoma cases. Multivariable Cox proportional hazards regression models were used to estimate relative risks (RRs) and 95 % confidence intervals (CIs) for the association between smoking status, years since smoking cessation, and endometrial carcinoma risk overall and within strata of endometrial carcinoma risk factors. Effect modification was assessed using likelihood ratio test statistics. Smoking associations by histologic subtype/grade and stage at diagnosis were also evaluated.

Results

Reduced endometrial carcinoma risk was evident among former (RR 0.89, 95 % CI 0.80, 1.00) and current (RR 0.65, 95 % CI 0.55, 0.78) smokers compared with never smokers. Smoking cessation 1–4 years prior to baseline was significantly associated with endometrial carcinoma risk (RR 0.65, 95 % CI 0.48, 0.89), while cessation ≥10 years before baseline was not. The association between smoking and endometrial carcinoma risk was not significantly modified by any endometrial carcinoma risk factor, nor did we observe major differences in risk associations by tumor characteristics.

Conclusion

The cigarette smoking–endometrial carcinoma risk relationship was consistent within strata of important endometrial carcinoma risk factors and by clinically relevant tumor characteristics.

Keywords: Cohort study, Cigarette smoking, Endometrial carcinoma, Effect modification

Introduction

The association between cigarette smoking and endometrial carcinoma risk has been evaluated in numerous epidemiological studies [1–3]. A decreased risk of this cancer has consistently been observed among ever smokers, with fairly uniform evidence of greater risk reductions among current as opposed to former smokers. In the few prospective studies that have explored quantitative metrics of cigarette smoking including duration, intensity, age at first use, and time since cessation among former smokers, relationships with endometrial carcinoma risk have been less clear [4–8]. Although current smokers have a lower overall risk, longer duration, greater consumption, earlier age at initiation, and less time since cessation—factors that usually correlate with currency of smoking—do not produce dose–response declines in endometrial carcinoma risk. The lack of a dose–response relation in prior work may be a result of limited numbers of cases; alternatively, the effects of cigarette smoking on endometrial carcinoma risk may not be not linear. Case–control studies of quantitative smoking metrics have reported reductions in endometrial cancer risk associated with long duration and high intensity, but assessment of smoking habits in case–control studies is potentially limited by recall bias [1].

Risk factors that result in higher levels of circulating estrogen relative to progesterone are known to increase the risk of endometrial carcinoma [9]. Cigarette smoking is thought to lower endometrial carcinoma risk through one of several anti-estrogenic mechanisms. First, cigarette smokers tend to be leaner than non-smokers, which would potentially result in reduced conversion of androstenedione to estrogen in adipose tissue. Other potential mechanisms include shifting estrogen metabolism to favor production of 2-hydroxyestrone, which is postulated to be anti-carcinogenic [10, 11], increases in circulating progesterone [12], and lowers the age at natural menopause through destruction of oocytes [13]. Interestingly, cigarette smoking is not protective for other estrogen-related cancers, such as breast cancer, and is in fact associated with increased risk of this tumor overall and for estrogen-receptor positive tumors in some studies [14].

Effect modification, which can be defined as variation in a selected risk factor across levels of other factors [15], may provide additional clues regarding potential mechanisms underlying the cigarette smoking–endometrial carcinoma risk relationship. Epidemiological studies evaluating menopausal status, body mass index (BMI), and menopausal hormone use as effect modifiers have generally reported stronger cigarette smoking–endometrial carcinoma risk reductions among postmenopausal women, obese women, or menopausal estrogen therapy users [4, 5, 8, 16–25]. The observation that cigarette smoking is seemingly protective among subgroups of women with presumably higher endogenous estrogen levels suggests that smoking exerts it effects on endometrial cancer risk via anti-estrogenic mechanisms [16, 18, 20, 22]. Fewer studies have examined effect modification by other hormonal and non-hormonal endometrial carcinoma risk factors, including age at menarche, parity, oral contraceptive use, diabetes, and physical activity. In addition to effect modification of the cigarette smoking–endometrial carcinoma relationship, associations between cigarette smoking metrics and endometrial carcinoma tumor characteristics may provide additional etiologic clues. Here, we prospectively examined the association between cigarette smoking and endometrial carcinoma risk within strata of endometrial carcinoma risk factors and by clinically important tumor characteristics.

Methods

Study population

The NIH–AARP Diet and Health study has been described previously [26]. Briefly, a baseline questionnaire was mailed in 1995–1996 to 3.5 million AARP members 50–71 years of age who resided in six states (California, Florida, Louisiana, New Jersey, North Carolina, and Pennsylvania) or two metropolitan areas (Atlanta, GA and Detroit, MI). Of 617,119 returned questionnaires, 566,398 were completed in satisfactory detail. We excluded study participants whose baseline questionnaire was completed by proxy (n = 15,760), were male (n = 325,171), had prevalent cancer other than non-melanoma skin cancer before baseline (n = 23,957), reported a hysterectomy before baseline (n = 82,107), had unknown hysterectomy status (n = 2,927), menstrual periods that stopped either due to surgery (n = 1,830), or radiation or chemotherapy (n = 117). We also excluded women who died or moved out of the study area before study entry (n = 12), those who developed non-epithelial endometrial cancer (i.e., uterine sarcoma) during follow-up (n = 47), women with missing smoking status (n = 3,338), and women with extreme values of BMI (BMI < 15 kg/m2 or BMI > 50 kg/m2, n = 828), leaving a baseline population of 110,304 women.

Between 1996 and 1997, a second questionnaire, which assessed menopausal hormone therapy (MHT) in greater detail, was sent to participants who did not have self-reported colon, breast, or prostate cancer at baseline. Approximately 64 % (n = 70,826) of eligible baseline participants successfully completed and returned the second questionnaire and contributed to analyses examining MHT use.

Cohort follow-up

Addresses for cohort members were updated annually in response to information provided by the participants and through the National Change of Address database. Vital status was ascertained using the U.S. Social Security Administration Death Master File, the National Death Index, cancer registry linkages, and mailing responses. The NIH–AARP Diet and Health Study was approved by the Special Studies Institutional Review Board of the U.S. National Cancer Institute, and all participants gave informed consent by virtue of completing and returning the questionnaire.

Cigarette smoking and covariate assessment

The baseline questionnaire queried participants on current smoking status, when they quit smoking, and the number of cigarettes smoked per day. Participants were considered ever smokers if they had smoked more than 100 cigarettes during their lifetime. Ever smokers were asked to record their typical daily cigarette consumption using 6 categories (1–10, 11–20, 21–30, 31–40, 41–60, ≥61), which we collapsed into ≤20 (1 pack) versus. >20 cigarettes per day. Women who had stopped smoking within 1 year of baseline were considered current cigarette smokers. Time since smoking cessation was grouped into 3 categories (cessation 1–4 years before baseline, cessation 5–9 years before baseline, and cessation ≥10 years before baseline). Assessment of cigarette smoking on the questionnaire has shown high reproducibility (r = 0.94) and validity (r = 0.92) for women relative to serum cotinine levels in previous methodology studies [27, 28].

Other covariates assessed by the baseline questionnaire included weight and height at time of questionnaire completion which were used to calculate BMI as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared (kg/m2). Frequency of vigorous physical activity was defined by how often women participated in exercise, sports, or carrying heavy loads that increased sweating, breathing, or heart rate and lasted ≥20 min. Participants were additionally queried on age at menarche, number of live births, menopausal status, age at menopause, oral contraceptive use, and history of diabetes. Because information on the regimen of MHT use was not available at baseline, we used information collected by the second questionnaire administered between 1996 and 1997. For each formulation (estrogen only, estrogen plus progestin, etc.), women reported dates of first and last use, total duration of use, usual dose, and the name of the pill that they took for the longest time. Based on previous analyses in this cohort [29], we categorized MHT use as no MHT, estrogen only, sequential estrogen plus progestin (progestin component delivered <15 days per cycle), continuous estrogen plus progestin (progestin component delivered ≥15 days per cycle), unknown MHT regimen, and unknown use.

Endometrial carcinoma case ascertainment

Incident cases of endometrial carcinoma were identified through probabilistic linkages to cancer registries in the eight states of the cohort as well as three common states of relocation (Arizona, Nevada, and Texas). Identification of cases by cancer registry linkage is reported to be 90 % in the NIH–AARP cohort [30]. Histology was defined using the International Classification of Diseases for Oncology (ICD-O 3rd Edition). Endometrial carcinoma cases with the following histology codes were included for analysis: endometrioid (8,380, 8,382, 8,383), mucinous adenocarcinoma (8,480–8,482) adenocarcinoma (8,140, 8,210, 8,560, 8,570), clear cell (8,310), serous (8,441, 8,460, 8,461), mixed cell (8,323), small cell (8,041), squamous cell, (8,070, 8,071, 8,076), and other histologic subtypes (8,000, 8,010, 8,012, 8,020–8,022, 8,050, 8,255, 8,260, 8,323, 8,950, 8,951, 8,980).

Statistical analysis

We used multivariable Cox proportional hazards regression models to estimate adjusted relative risks (RRs) and 95 % confidence intervals (CIs) for endometrial carcinoma risk associated with detailed smoking variables with age as the underlying time metric. All regression models used never smokers as the referent group. Follow-up time began at the age at which the baseline questionnaire (for the main analyses) or the second questionnaire (for analyses related to formulation of MHT) was received and scanned and continued through the earliest of the following dates: participant diagnosed with endometrial cancer, moved out of her registry catchment area, died from any cause, or 31 December, 2006. Models were adjusted for race (White, non-White), age at menarche (≤12, 13–14, ≥15), BMI at baseline (<25, 25–29.9, ≥30 kg/m2), parity (nulliparous, 1–2, ≥3), age at menopause (premenopausal, <45, 45–49, 50–54, ≥55), oral contraceptive use (ever, never), MHT use from the baseline questionnaire (never, ever), history of diabetes (no, yes), and frequency of vigorous physical activity (never/rarely, 1–3 times per month, 1–2 times per week, 3–4 times per week, and ≥5 times per week). MHT use from the second questionnaire was categorized as previously described.

We assessed effect modification by creating multiplicative interaction terms between the smoking variables and each endometrial carcinoma risk factor namely, race, age at menarche, BMI, parity, oral contraceptive use, menopausal status, age at menopause among postmenopausal women, MHT use, history of diabetes, and physical activity and calculating a likelihood ratio test statistic comparing models with and without the interaction terms.

Smoking associations were also evaluated by clinical characteristics of the tumor, namely histology (Type I, Type II) and SEER summary stage (localized, regional/distant). As defined in a previous analysis [31] Type I tumors included endometrioid, mucinous, and adenocarcinoma histologic subtypes. Within the Type I category, we also conducted analyses examining risks for low-grade endometrioid and high-grade endometrioid tumors, which have been identified as having distinct etiologies [32]. Type II tumors included serous, clear cell, mixed cell, small cell, and squamous cell tumors. Models predicting risk for one subgroup while censoring the other subgroups were analyzed. To test for statistical heterogeneity in associations between smoking and endometrial tumor characteristics, case-only logistic regression models were used with histology type or stage as the dependent variable. In these logistic regression models, we adjusted for the same covariates included in the Cox proportional hazards regression models and additionally adjusted for age at enrollment and person years to account for duration in the cohort.

The proportional hazards assumption was tested for the smoking variables and covariates by including interaction terms between the time scale (age) and each variable and calculating a likelihood ratio test statistic. The assumption of proportional hazards held for all variables (p > 0.20). All analyses were performed using SAS 9.3 software (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC) and a p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Among the 110,304 women who completed the baseline questionnaire and were eligible for analysis, 1,476 incident endometrial carcinoma cases were diagnosed. Median follow-up was 10.5 and 5.1 years among the non-cases and endometrial carcinoma cases, respectively. Median ages at enrollment were 62.1 (interquartile range [IQR] = 9.2) for non-cases compared with 63.0 (IQR = 8.4) for endometrial carcinoma cases, and median ages at study exit were 71.2 (IQR = 9.5) and 67.7 (IQR = 8.5). Among the 70,826 women who completed the second questionnaire and were eligible for this analysis, 935 incident endometrial carcinomas were identified through 2006. Characteristics of the study population according to smoking status are shown in Table 1. At baseline, 45 % of women were never smokers, 38 % were former smokers, and 17 % were current smokers. Compared with never smokers, current smokers tended to be younger at baseline and were more likely to be White, normal-weight, have younger ages at menopause, use oral contraceptives, and were less likely to be current or former users of menopausal hormones. Of the 40 % of current smokers who reported any MHT use, 18 % reported continuous estrogen plus progestin use, 11 % sequential estrogen and progestin use, and 8 % estrogen-only MHT.

Table 1.

Distributions of select characteristics of study participants in relation to smoking status at enrollment in the NIH–AARP Diet and Health Study, 1995–2006

| Smoking status

|

pa | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Never (n = 49,768) n (%) |

Former (n = 41,824) n (%) |

Current (n = 18,712) n (%) |

||

| Age, years | <0.0001 | |||

| <55 | 7,645 (15.4) | 6,321 (15.1) | 3,557 (19.0) | |

| 55–59 | 11,560 (23.2) | 9,566 (22.9) | 4,669 (24.9) | |

| 60–64 | 13,274 (26.7) | 11,528 (27.6) | 5,164 (27.6) | |

| 65–69 | 15,490 (31.1) | 12,990 (31.1) | 4,849 (25.9) | |

| ≥70 | 1,799 (3.6) | 1,419 (3.4) | 473 (2.5) | |

| Race | <0.0001 | |||

| White | 44,325 (89.1) | 38,613 (92.3) | 17,104 (91.4) | |

| Non-white | 5,443 (10.9) | 3,211 (7.7) | 1,608 (8.6) | |

| Age at menarche | 0.0003 | |||

| ≤12 | 23,581 (47.4) | 19,675 (47.0) | 8,931 (47.7) | |

| 13–14 | 21,218 (42.6) | 18,188 (43.5) | 7,821 (41.8) | |

| ≥15 | 4,804 (9.6) | 3,846 (9.2) | 1,911 (10.2) | |

| BMI (kg/m2) | <0.0001 | |||

| Normal (<25) | 21,940 (44.1) | 17,869 (42.7) | 10,016 (53.5) | |

| Overweight (25–29.99) | 15,309 (30.8) | 13,320 (31.8) | 5,263 (28.1) | |

| Obese (≥30) | 10,861 (21.8) | 9,580 (22.9) | 2,771 (14.8) | |

| Parity | 0.0001 | |||

| Nulliparous | 8,927 (17.9) | 7,200 (17.2) | 3,225 (17.2) | |

| 1–2 | 18,103 (36.4) | 15,737 (37.6) | 7,042 (37.6) | |

| ≥3 | 22,534 (45.3) | 18,758 (44.8) | 8,382 (44.8) | |

| Oral contraceptive use | <0.0001 | |||

| Never | 30,891 (62.1) | 23,601 (56.4) | 10,444 (55.8) | |

| Ever | 18,525 (37.2) | 17,998 (43.0) | 8,137 (43.4) | |

| Menopausal status | <0.0001 | |||

| Premenopausal | 3,357 (6.7) | 2,678 (6.4) | 919 (4.9) | |

| Postmenopausal | 44,528 (89.5) | 37,530 (89.7) | 17,279 (92.3) | |

| Age at menopauseb | <0.0001 | |||

| <45 | 4,340 (8.7) | 4,528 (10.8) | 2,907 (15.5) | |

| 45–49 | 11,291 (22.7) | 10,760 (25.7) | 5,948 (31.8) | |

| 50–54 | 23,151 (46.5) | 18.214 (43.5) | 7,275 (38.9) | |

| ≥55 | 5,746 (11.5) | 4,028 (9.6) | 1,149 (6.1) | |

| Menopausal hormone use (Baseline assessment) | <0.0001 | |||

| Never | 30,372 (61.0) | 23,341 (55.8) | 12,396 (66.2) | |

| Current | 15,646 (31.4) | 14,892 (35.6) | 5,029 (26.9) | |

| Former | 3,677 (7.4) | 3,521 (8.4) | 1,266 (6.8) | |

| Menopausal hormone use (Risk factor assessment) | <0.0001 | |||

| Never | 17,027 (53.0) | 13,114 (47.6) | 6,443 (57.6) | |

| Estrogen only | 2,044 (6.4) | 1,850 (6.7) | 937 (8.4) | |

| Sequential estrogen plus progestin | 4,274 (13.3) | 4,177 (15.2) | 1,200 (10.7) | |

| Continuous estrogen plus progestin | 6,778 (21.1) | 6,530 (23.7) | 1,992 (17.8) | |

| Unknown regimen | 848 (2.6) | 878 (3.2) | 279 (2.5) | |

| History of diabetes | <0.0001 | |||

| No | 46,466 (93.4) | 38,942 (93.1) | 17,659 (94.4) | |

| Yes | 3,302 (6.6) | 2,882 (6.9) | 1,053 (5.6) | |

| Physical activity | <0.0001 | |||

| Never/rarely | 10,089 (20.3) | 5,260 (19.7) | 5,609 (30.0) | |

| 1–3 times/month | 6,834 (13.7) | 5,672 (13.6) | 3,291 (17.6) | |

| 1–2 times/week | 10,656 (21.4) | 8,568 (20.5) | 4,008 (21.4) | |

| 3–4 times/week | 12,965 (26.0) | 11,227 (26.8) | 3,548 (19.0) | |

| 5+ times/week | 8,658 (17.4) | 7,754 (18.5) | 2,054 (11.0) | |

Chi-squared p value

Among postmenopausal women

Table 2 shows the distribution of detailed smoking variables among endometrial carcinoma cases and non-cases and multivariable-adjusted RRs associated with endometrial carcinoma risk. Endometrial carcinoma incidence was lower in current (RR 0.65, 95 % CI 0.55, 0.78) and former smokers (RR 0.89, 95 % CI 0.80, 1.00) compared with never smokers, and the difference between current and former smokers was significantly different (p = 0.001). Compared with never smokers, cessation 1–4 years prior to baseline was significantly associated with reduced endometrial carcinoma risk (RR 0.65, 95 % CI 0.48, 0.89); however, no significant reduction was noted for women who quit smoking ≥5 years prior to baseline. Among current and former smokers, endometrial carcinoma risk did not significantly differ according to the number of cigarettes smoked per day (p > 0.20).

Table 2.

Relative risks and 95 % CIs for endometrial carcinoma risk in relation to cigarette smoking among 110,304 women in the NIH–AARP Diet and Health Study, 1995–2006

| Non-cases n = 108,828 |

Endometrial carcinoma cases n = 1,476 |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Person years | n (%) | n (%) | RR (95 % CI)a | |

| Smoking history | ||||

| Never | 470,730 | 45.0 | 772 (52.3) | 1 (Ref) |

| Former | 385,016 | 37.9 | 559 (37.9) | 0.89 (0.80, 1.00) |

| Current | 165,376 | 17.1 | 145 (9.8) | 0.65 (0.55, 0.78) |

| Intensity | ||||

| Former smokers | ||||

| ≤20 cigarettes/day | 265,252 | 25.9 | 382 (25.9) | 0.91 (0.81, 1.03) |

| >20 cigarettes/day | 119,763 | 12.0 | 177 (12.0) | 0.85 (0.72, 1.00) |

| Current smokers | ||||

| ≤20 cigarettes/day | 122,013 | 12.4 | 102 (6.9) | 0.64 (0.52, 0.78) |

| >20 cigarettes/day | 43,662 | 4.6 | 43 (2.9) | 0.70 (0.51, 0.95) |

| Time since quitting among former smokersb | ||||

| Cessation ≥10 years ago | 273,108 | 32.1 | 422 (31.7) | 0.95 (0.84, 1.07) |

| Cessation 5–9 years ago | 69,172 | 8.3 | 93 (7.0) | 0.81 (0.66, 1.01) |

| Cessation 1–4 years ago | 42,735 | 5.2 | 44 (3.3) | 0.65 (0.48, 0.89) |

Adjusted for race (white, non-white), age at menarche (≤12, 13–14, ≥15), BMI (normal, overweight, obese), parity (nulliparous, 1–2, ≥3), oral contraceptive use (never, ever), age at menopause (premenopausal,<45, 45–49, 50–54, ≥55), menopausal hormone use (never, current, former), diabetes (never, ever), physical activity (never/rarely, 1–3 times/month, 1–2 times/week, 3–4 times/week, ≥5 times/week). Unknown was set as a separate category within each factor

Current smokers excluded

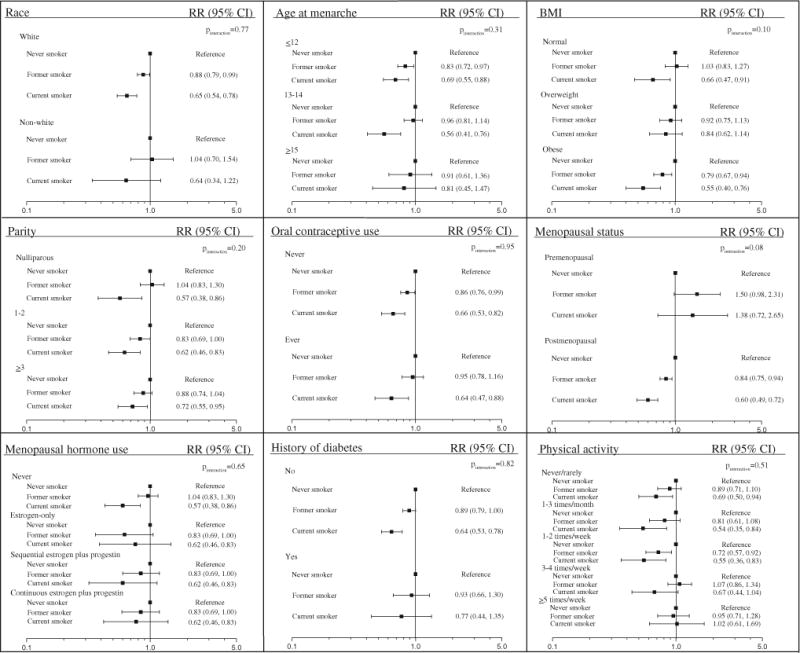

Effect modification of the cigarette smoking–endometrial carcinoma risk association is shown in Fig. 1. The association between smoking status and endometrial carcinoma risk was not significantly modified by any endometrial carcinoma risk factor examined in our analysis. A suggestion of an interaction for menopausal status was observed (pinteraction = 0.08); among postmenopausal women, former (RR 0.84, 95 % CI 0.75, 0.94) and current smokers (RR 0.60, 95 % CI 0.49, 0.72) had significantly reduced risk of endometrial carcinoma similar to the main analysis. Although not statistically significant, the reverse trend was observed for former and current premenopausal smokers. Additionally, we observed differences in the strength of associations between current smoking and endometrial carcinoma risk in analyses stratified by BMI, but these differences did not reach statistical significance (pinteraction = 0.10).

Fig. 1.

Relative risks and 95 % CIs for smoking status and endometrial carcinoma risk within strata of endometrial cancer risk factors among 110,304 women in the NIH–AARP Diet and Health Study, 1995–2006

Table 3 shows associations between smoking status and endometrial carcinoma risk by clinically important tumor characteristics. Tumor grade and stage were missing for 7 and 33 % of cases, respectively. Current smoking was inversely related to risk of Type I (RR 0.71, 95 % CI 0.58, 0.87) and Type II endometrial carcinomas (RR 0.38, 0.16, 0.89). No significant difference between the two subtypes was observed (pheterogeneity = 0.14). In analysis of specific histologic subtypes of the Type I category, we noted that current smoking was significantly associated with risk of low-grade endometrioid tumors (RR 0.61, 95 % CI 0.46, 0.82), but not high-grade endometrioid tumors (RR 1.04, 95 % CI 0.54, 2.00); however, this difference was not statistically significant (pheterogeneity = 0.34). Similar to the main analyses, current smoking was inversely related to localized tumors (RR 0.63, 95 % CI 0.48, 0.82) and regional/distant tumors (RR 0.56, 95 % CI 0.32, 0.96, pheterogeneity = 0.92).

Table 3.

Relative risks and 95 % CIs for smoking status and endometrial carcinoma risk by tumor characteristics

| Tumor characteristicsa | Smoking status

|

pheterogeneity | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Never (n = 49,768)

|

Former (n = 41,824)

|

Current (n = 18,712)

|

|||||

| Cases | RR (95 % CI)b | Cases | RR (95 % CI)b | Cases | RR (95 % CI)b | ||

| Histology | |||||||

| Type I | 653 | 1 (ref) | 490 | 0.92 (0.82, 1.03) | 127 | 0.68 (0.56, 0.82) | 0.15c |

| Low-grade endometrioid | 333 | 1 (ref) | 244 | 0.90 (0.76, 1.06) | 56 | 0.61 (0.46, 0.82) | 0.34d |

| High-grade endometrioid | 42 | 1 (ref) | 36 | 1.03 (0.66, 1.61) | 12 | 1.04 (0.54, 2.00) | |

| Type II | 63 | 1 (ref) | 36 | 0.74 (0.49, 1.12) | 8 | 0.41 (0.20, 0.87) | |

| Stage | 0.92e | ||||||

| Localized | 417 | 1 (ref) | 288 | 0.85 (0.73, 0.98) | 72 | 0.59 (0.46, 0.76) | |

| Regional/distant | 111 | 1 (ref) | 78 | 0.91 (0.68, 1.21) | 17 | 0.53 (0.32, 0.89) | |

Associations were evaluated for subgroups defined by histology/grade and SEER summary stage using models to predict risk for one subgroup. Cases of other subgroups were censored at the time of diagnosis

Adjusted for race (white, non-white), age at menarche (≤12, 13–14, ≥15), BMI (normal, overweight, obese), parity (nulliparous, 1–2, ≥3), oral contraceptive use (never, ever), age at menopause (premenopausal,<45, 45–49, 50–54, ≥55), menopausal hormone use (never, current, former), diabetes (never, ever), physical activity (never/rarely, 1–3 times/month, 1–2 times/week, 3–4 times/week, ≥5 times/week). Unknown was set as a separate category within each factor

pheterogeneity is from logistic regression of case-only analysis comparing smoking status between Type I and Type II endometrial cancer cases

pheterogeneity is from logistic regression of case-only analysis comparing smoking status between low-grade endometrioid and high-grade endometrial cancer cases

pheterogeneity is from logistic regression of case-only analysis comparing smoking status between localized and regional/distant endometrial cancer cases

We examined effect modification of the years since smoking cessation–endometrial carcinoma risk relationship by collapsing the categories cessation 1–4 years prior to baseline and current smokers into a “recent smokers” category given similar estimates of effect in Table 2. We also combined cessation 5–9 years prior to baseline and cessation ≥10 years before baseline given similar effect estimates and small numbers of cases in these categories. Again, menopausal status was the only factor suggestive of modifying the relation between years since smoking cessation and endometrial carcinoma risk (p = 0.09). Among postmenopausal women, recent smokers (RR 0.61, 95 % CI 0.51, 0.72) and those who quit ≥5 years before baseline (RR 0.86, 95 % CI 0.77, 0.97) had significantly reduced risks of endometrial carcinoma compared with never smokers (Supplemental Table 1). Among premenopausal women, cessation ≥5 years before baseline (RR 1.60, 95 % CI 1.03, 2.47) but not recent smoking was significantly associated with endometrial carcinoma risk. With respect to years since smoking cessation and endometrial tumor characteristics, recent smokers had reduced risks of Type I, low-grade endometrioid, Type II, and localized tumors; no significant heterogeneity between histology subtypes or stage classifications were observed (pheterogeneity > 0.12, Supplementary Table 2).

Discussion

Our large prospective study including more than 110,000 women enrolled in the NIH–AARP Diet and Health Study Cohort showed that current and former smokers who recently quit had significantly lower endometrial carcinoma risks compared with never smokers. The effect of cigarette smoking on endometrial carcinoma risk was not significantly modified by any endometrial carcinoma risk factor; however, there was a suggestion that menopausal status modified the association, with lower endometrial carcinoma risk among postmenopausal but not premenopausal smokers. Furthermore, we did not observe heterogeneity in risk estimates according to endometrial tumor characteristics.

Imbalances in the sex-steroid hormones, estrogen and progesterone, are strongly related to development of endometrial carcinoma [9]. Exposure of the endometrium to high levels of estrogen in the absence of progesterone is postulated to result in increased cellular proliferation and higher rates of mutation, potentially leading to malignant transformation. As such, factors that increase estrogen relative to progesterone are associated with increased endometrial carcinoma risk, whereas factors that lower estrogen relative to progesterone are thought to be protective. As observed in other prospective investigations [4–6, 8, 33, 34], current cigarette smoking was inversely related to endometrial carcinoma in our cohort which has led some to hypothesize that cigarette smoking is anti-estrogenic [35–37]. While endogenous estrogen levels have not been shown to vary meaningfully between non-smokers and smokers [12, 38–45], alteration of estrogen metabolism, which mainly occurs in hepatic tissues, may be related to cigarette smoking. As opposed to 2-hydroxyestrogen, 16alpha-hydroxyestrogen stimulates cell proliferation and has been found to be related to higher risk of breast and endometrial carcinomas [46–48]. Among smokers, increased clearance of 16alpha-hydroxyestrone has been observed, which may explain the inverse association between cigarette smoking and endometrial carcinoma risk [11, 49]. The paucity of studies exploring relationships between estrogen metabolites, cigarette smoking, and endometrial carcinoma risk warrants additional investigation.

Some have speculated that cigarette smoking is related to endometrial carcinoma risk through relationships with other known risk factors for the disease. As such, we assessed effect modification of cigarette smoking and endometrial carcinoma risk by other endometrial carcinoma risk factors. Smoking-associated risk of endometrial carcinoma did not differ significantly by any endometrial carcinoma risk factor examined in this study, although we did observe possible differences between premenopausal and postmenopausal women. Our finding that smoking reduced endometrial carcinoma risk among postmenopausal women is in line with previous studies [8, 18, 50–53]. The exact mechanisms underlying a protective effect in postmenopausal women are unknown; some have proposed that cigarette smoking has direct toxic effects on the ovaries, resulting in progesterone deficiency, consequently producing a higher estrogen to progesterone ratio leading to endometrial cell proliferation [8, 54, 55]. However, others have reported higher progesterone levels among smokers compared with non-smokers, detracting from the plausibility of this hypothesis [39, 56]. Among premenopausal women, we and others [8, 18] observed a nonsignificant increase in endometrial carcinoma risk associated with former and current smoking. The small number of premenopausal women in this cohort likely resulted in limited power in detecting an association in this subgroup.

We did not observe effect modification by other factors associated with endometrial carcinoma risk. Previous epidemiological studies have reported lower endometrial carcinoma risk among smokers who are obese [16, 19, 22] or menopausal estrogen users [24, 25] while others reported no effect modification by these two risk factors [4, 5, 8, 16–18, 20, 21, 23, 37]. Furthermore, parity [4, 17–20], oral contraceptive use [4, 17, 18, 22, 23, 25], and history of diabetes [19, 20] have not been shown to modify this relationship. The consistency of risk estimates across strata of endometrial carcinoma risk factors may indicate that cigarette smoking lowers endometrial carcinoma risk through a common mechanism regardless of other characteristics related to endometrial carcinogenesis. Whether this common mechanism is anti-estrogenic cannot be determined from our data. Future studies with information on relevant endometrial carcinoma biomarkers will be useful in determining the mechanism through which cigarette smoking lowers endometrial carcinoma risk.

Endometrial carcinoma is a heterogeneous disease and is commonly classified in two broad categories, Type I and Type II. Type I cancers are more common, typically of endometrioid morphology, and are etiologically related to imbalances in estrogen and progesterone. Type II or non-endometrioid cancers, which generally include serous, clear cell, and mixed-cell histologic types, are less common and have been the focus of fewer investigations. Previous studies have proposed that Type II tumors are less associated with hormonal and reproductive risk factors than Type I tumors [31, 32, 57–59], whereas a recent, large study performed in the Epidemiology of Endometrial Cancer Consortium suggested that serous and mixed-cell endometrial tumors are similarly associated with the classical endometrial carcinoma risk factors and are not as hormone independent as previously considered [60]. Our exploration of cigarette smoking and risk of endometrial carcinoma histologic subtypes did not provide evidence of major differences between the broad Type I and Type II subtypes or between the more narrow categories of low-grade endometrioid and high-grade endometrioid, which agrees with previous studies [31, 60]. These observations lend additional support to the hypothesis that cigarette smoking reduces endometrial carcinoma risk by a common mechanism. Stage is another clinically important tumor characteristic, and while some have reported cigarette smoking to be more strongly associated with late-stage tumors [61, 62], we observed similar inverse associations for early and late-stage tumors.

Our study has several notable strengths, including the large size of the cohort, availability of detailed smoking variables and known endometrial carcinoma risk factors, and the prospective design which eliminated recall bias as an explanation for our findings. The large number of endometrial carcinoma cases enabled us to evaluate effect modification by other risk factors for the disease, which has been a limitation of previous studies. Limitations of our study included lack of information on other smoking characteristics, including smoking duration, age at initiation, and type of cigarette smoked. Furthermore, we only assessed smoking status at baseline which may lead to misclassification bias if smoking behaviors changed during follow-up. Given the prospective nature of this study, this would likely lead to non-differential misclassification between cases and non-cases which would bias our results toward the null. Despite these limitations, our prospective investigation provides evidence that the cigarette smoking–endometrial carcinoma risk relationship is possibly modified by menopausal status, but not other endometrial carcinoma risk factors. Furthermore, we noted consistent effects of cigarette smoking by endometrial tumor characteristics. Taken together, these data suggest that a shared mechanism may contribute to the inverse association between cigarette smoking and endometrial carcinoma risk which should be furthered explored, as this research might inform prevention strategies to reduce endometrial carcinoma incidence.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the NIH, National Cancer Institute. Cancer incidence data from the Atlanta metropolitan area were collected by the Georgia Center for Cancer Statistics, Department of Epidemiology, Rollins School of Public Health, Emory University. Cancer incidence data from California were collected by the California Department of Health Services, Cancer Surveillance Section. Cancer incidence data from the Detroit metropolitan area were collected by the Michigan Cancer Surveillance Program, Community Health Administration, State of Michigan. The Florida cancer incidence data used in this report were collected by the Florida Cancer Data System under contract to the Department of Health. Cancer incidence data from Louisiana were collected by the Louisiana Tumor Registry, Louisiana State University Medical Center in New Orleans. Cancer incidence data from New Jersey were collected by the New Jersey State Cancer Registry, Cancer Epidemiology Services, New Jersey State Department of Health and Senior Services. Cancer incidence data from North Carolina were collected by the North Carolina Central Cancer Registry. Cancer incidence data from Pennsylvania were supplied by the Division of Health Statistics and Research, Pennsylvania Department of Health, Harrisburg, Pennsylvania. Cancer incidence data from Arizona were collected by the Arizona Cancer Registry, Division of Public Health Services, Arizona Department of Health Services. Cancer incidence data from Texas were collected by the Texas Cancer Registry, Cancer Epidemiology and Surveillance Branch, Texas Department of State Health Services. The views expressed herein are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the contractor or the Florida Department of Health. The Pennsylvania Department of Health specifically disclaims responsibility for any analyses, interpretations, or conclusions.

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary material The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s10552-014-0350-1) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Contributor Information

Ashley S. Felix, Email: ashley.felix@gmail.com, Hormonal and Reproductive Epidemiology Branch, Division of Cancer Epidemiology and Genetics, National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health, 9609 Medical Center Drive, Bethesda, MD 20892-9774, USA Cancer Prevention Fellowship Program, Division of Cancer Prevention, National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA.

Hannah P. Yang, Hormonal and Reproductive Epidemiology Branch, Division of Cancer Epidemiology and Genetics, National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health, 9609 Medical Center Drive, Bethesda, MD 20892-9774, USA

Gretchen L. Gierach, Hormonal and Reproductive Epidemiology Branch, Division of Cancer Epidemiology and Genetics, National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health, 9609 Medical Center Drive, Bethesda, MD 20892-9774, USA

Yikyung Park, Nutritional Epidemiology Branch, Division of Cancer Epidemiology and Genetics, National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA.

Louise A. Brinton, Hormonal and Reproductive Epidemiology Branch, Division of Cancer Epidemiology and Genetics, National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health, 9609 Medical Center Drive, Bethesda, MD 20892-9774, USA

References

- 1.Terry PD, Rohan TE, Franceschi S, Weiderpass E. Cigarette smoking and the risk of endometrial cancer. Lancet Oncol. 2002;3(8):470–480. doi: 10.1016/s1470-2045(02)00816-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Services USDoHaH. The health consequences of involuntary exposure to tobacco smoke: A Report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta, GA: 2006. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhou B, Yang L, Sun Q, Cong R, Gu H, et al. Cigarette smoking and the risk of endometrial cancer: a meta-analysis. Am J Med. 2008;121(6):501–508. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2008.01.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Terry PD, Miller AB, Rohan TE. A prospective cohort study of cigarette smoking and the risk of endometrial cancer. Br J Cancer. 2002;86(9):1430–1435. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6600278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Viswanathan AN, Feskanich D, De Vivo I, Hunter DJ, Barbieri RL, et al. Smoking and the risk of endometrial cancer: results from the Nurses’ Health Study. Int J Cancer. 2005;114(6):996–1001. doi: 10.1002/ijc.20821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Loerbroks A, Schouten LJ, Goldbohm RA, van den Brandt PA. Alcohol consumption, cigarette smoking, and endometrial cancer risk: results from the Netherlands Cohort Study. Cancer Causes Control. 2007;18(5):551–560. doi: 10.1007/s10552-007-0127-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nordlund LA, Carstensen JM, Pershagen G. Cancer incidence in female smokers: a 26-year follow-up. Int J Cancer. 1997;73(5):625–628. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0215(19971127)73:5<625::aid-ijc2>3.0.co;2-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Al-Zoughool M, Dossus L, Kaaks R, Clavel-Chapelon F, Tjonneland A, et al. Risk of endometrial cancer in relationship to cigarette smoking: results from the EPIC study. Int J Cancer. 2007;121(12):2741–2747. doi: 10.1002/ijc.22990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kaaks R, Lukanova A, Kurzer MS. Obesity, endogenous hormones, and endometrial cancer risk: a synthetic review. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2002;11(12):1531–1543. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bradlow HL, Telang NT, Sepkovic DW, Osborne MP. 2-hydroxyestrone: the ‘good’ estrogen. J Endocrinol. 1996;150(Suppl):S259–S265. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Michnovicz JJ, Hershcopf RJ, Naganuma H, Bradlow HL, Fishman J. Increased 2-hydroxylation of estradiol as a possible mechanism for the anti-estrogenic effect of cigarette smoking. N Engl J Med. 1986;315(21):1305–1309. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198611203152101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Longcope C, Johnston CC., Jr Androgen and estrogen dynamics in pre- and postmenopausal women: a comparison between smokers and nonsmokers. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1988;67(2):379–383. doi: 10.1210/jcem-67-2-379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mattison DR, Thorgeirsson SS. Smoking and industrial pollution, and their effects on menopause and ovarian cancer. Lancet. 1978;1(8057):187–188. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(78)90617-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gaudet MM, Gapstur SM, Sun J, Diver WR, Hannan LM, et al. Active smoking and breast cancer risk: original cohort data and meta-analysis. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2013;105(8):515–525. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djt023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Porta M. A dictionary of epidemiology. 5. Oxford University Press; New York, NY: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lawrence C, Tessaro I, Durgerian S, Caputo T, Richart R, et al. Smoking, body weight, and early-stage endometrial cancer. Cancer. 1987;59(9):1665–1669. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19870501)59:9<1665::aid-cncr2820590924>3.0.co;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Levi F, la Vecchia C, Decarli A. Cigarette smoking and the risk of endometrial cancer. Eur J Cancer Clin Oncol. 1987;23(7):1025–1029. doi: 10.1016/0277-5379(87)90353-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brinton LA, Barrett RJ, Berman ML, Mortel R, Twiggs LB, et al. Cigarette smoking and the risk of endometrial cancer. Am J Epidemiol. 1993;137(3):281–291. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a116675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Parazzini F, La Vecchia C, Negri E, Moroni S, Chatenoud L. Smoking and risk of endometrial cancer: results from an Italian case–control study. Gynecol Oncol. 1995;56(2):195–199. doi: 10.1006/gyno.1995.1031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Newcomer LM, Newcomb PA, Trentham-Dietz A, Storer BE. Hormonal risk factors for endometrial cancer: modification by cigarette smoking (United States) Cancer Causes Control. 2001;12(9):829–835. doi: 10.1023/a:1012297905601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chang SC, Lacey JV, Jr, Brinton LA, Hartge P, Adams K, et al. Lifetime weight history and endometrial cancer risk by type of menopausal hormone use in the NIH–AARP diet and health study. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2007;16(4):723–730. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-06-0675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Polesel J, Serraino D, Zucchetto A, Lucenteforte E, Dal Maso L, et al. Cigarette smoking and endometrial cancer risk: the modifying effect of obesity. Eur J Cancer Prev. 2009;18(6):476–481. doi: 10.1097/CEJ.0b013e32832f9bc4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yang HP, Brinton LA, Platz EA, Lissowska J, Lacey JV, Jr, et al. Active and passive cigarette smoking and the risk of endometrial cancer in Poland. Eur J Cancer. 2010;46(4):690–696. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2009.11.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Weiss NS, Farewall VT, Szekely DR, English DR, Kiviat N. Oestrogens and endometrial cancer: effect of other risk factors on the association. Maturitas. 1980;2(3):185–190. doi: 10.1016/0378-5122(80)90003-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Franks AL, Kendrick JS, Tyler CW., Jr Postmenopausal smoking, estrogen replacement therapy, and the risk of endometrial cancer. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1987;156(1):20–23. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(87)90196-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schatzkin A, Subar AF, Thompson FE, Harlan LC, Tangrea J, et al. Design and serendipity in establishing a large cohort with wide dietary intake distributions : the National Institutes of Health-American Association of Retired Persons Diet and Health Study. Am J Epidemiol. 2001;154(12):1119–1125. doi: 10.1093/aje/154.12.1119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Assaf AR, Parker D, Lapane KL, McKenney JL, Carleton RA. Are there gender differences in self-reported smoking practices? Correlation with thiocyanate and cotinine levels in smokers and nonsmokers from the Pawtucket Heart Health Program. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2002;11(10):899–906. doi: 10.1089/154099902762203731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Petitti DB, Friedman GD, Kahn W. Accuracy of information on smoking habits provided on self-administered research questionnaires. Am J Public Health. 1981;71(3):308–311. doi: 10.2105/ajph.71.3.308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Trabert B, Wentzensen N, Yang HP, Sherman ME, Hollenbeck AR, et al. Is estrogen plus progestin menopausal hormone therapy safe with respect to endometrial cancer risk? Int J Cancer. 2013;132(2):417–426. doi: 10.1002/ijc.27623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Michaud D, Midthuner D, Hermansen S, Leitzmann MF, Harlan LC, et al. Comparison of cancer registry case ascertainment with SEER estimates and self-reporting in a subset of the NIH– AARP Diet and Health Study. J Registry Manag. 2005;32(2):6. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yang HP, Wentzensen N, Trabert B, Gierach GL, Felix AS, et al. Endometrial cancer risk factors by 2 main histologic subtypes: the NIH–AARP Diet and Health Study. Am J Epidemiol. 2013;177(2):142–151. doi: 10.1093/aje/kws200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Brinton LA, Felix AS, McMeekin DS, Creasman WT, Sherman ME, et al. Etiologic heterogeneity in endometrial cancer: evidence from a gynecologic oncology group trial. Gynecol Oncol. 2013;129(2):277–284. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2013.02.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Folsom AR, Demissie Z, Harnack L, Iowa Women’s Health S Glycemic index, glycemic load, and incidence of endometrial cancer: the Iowa women’s health study. Nutr Cancer. 2003;46(2):119–124. doi: 10.1207/S15327914NC4602_03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lacey JV, Jr, Leitzmann MF, Chang SC, Mouw T, Hollenbeck AR, et al. Endometrial cancer and menopausal hormone therapy in the National Institutes of Health–AARP Diet and Health Study cohort. Cancer. 2007;109(7):1303–1311. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jensen J, Christiansen C, Rodbro P. Cigarette smoking, serum estrogens, and bone loss during hormone-replacement therapy early after menopause. N Engl J Med. 1985;313(16):973–975. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198510173131602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Baron JA. Smoking and estrogen-related disease. Am J Epidemiol. 1984;119(1):9–22. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a113730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Weiderpass E, Baron JA. Cigarette smoking, alcohol consumption, and endometrial cancer risk: a population-based study in Sweden. Cancer Causes Control. 2001;12(3):239–247. doi: 10.1023/a:1011201911664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.MacMahon B, Trichopoulos D, Cole P, Brown J. Cigarette smoking and urinary estrogens. N Engl J Med. 1982;307(17):1062–1065. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198210213071707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Friedman AJ, Ravnikar VA, Barbieri RL. Serum steroid hormone profiles in postmenopausal smokers and nonsmokers. Fertil Steril. 1987;47(3):398–401. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Khaw KT, Tazuke S, Barrett-Connor E. Cigarette smoking and levels of adrenal androgens in postmenopausal women. N Engl J Med. 1988;318(26):1705–1709. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198806303182601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schlemmer A, Jensen J, Riis BJ, Christiansen C. Smoking induces increased androgen levels in early post-menopausal women. Maturitas. 1990;12(2):99–104. doi: 10.1016/0378-5122(90)90087-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Berta L, Frairia R, Fortunati N, Fazzari A, Gaidano G. Smoking effects on the hormonal balance of fertile women. Horm Res. 1992;37(1–2):45–48. doi: 10.1159/000182280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Key TJ, Pike MC, Brown JB, Hermon C, Allen DS, et al. Cigarette smoking and urinary oestrogen excretion in premenopausal and post-menopausal women. Br J Cancer. 1996;74(8):1313–1316. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1996.536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Law MR, Cheng R, Hackshaw AK, Allaway S, Hale AK. Cigarette smoking, sex hormones and bone density in women. Eur J Epidemiol. 1997;13(5):553–558. doi: 10.1023/a:1007389712487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lucero J, Harlow BL, Barbieri RL, Sluss P, Cramer DW. Early follicular phase hormone levels in relation to patterns of alcohol, tobacco, and coffee use. Fertil Steril. 2001;76(4):723–729. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(01)02005-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Fishman J, Schneider J, Hershcope RJ, Bradlow HL. Increased estrogen-16 alpha-hydroxylase activity in women with breast and endometrial cancer. J Steroid Biochem. 1984;20(4B):1077–1081. doi: 10.1016/0022-4731(84)90021-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Fuhrman BJ, Schairer C, Gail MH, Boyd-Morin J, Xu X, et al. Estrogen metabolism and risk of breast cancer in postmenopausal women. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2012;104(4):326–339. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djr531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zeleniuch-Jacquotte A, Shore RE, Afanasyeva Y, Lukanova A, Sieri S, et al. Postmenopausal circulating levels of 2- and 16alpha-hydroxyestrone and risk of endometrial cancer. Br J Cancer. 2011;105(9):1458–1464. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2011.381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Barbieri RL, McShane PM, Ryan KJ. Constituents of cigarette smoke inhibit human granulosa cell aromatase. Fertil Steril. 1986;46(2):232–236. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lesko SM, Rosenberg L, Kaufman DW, Helmrich SP, Miller DR, et al. Cigarette smoking and the risk of endometrial cancer. N Engl J Med. 1985;313(10):593–596. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198509053131001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Smith EM, Sowers MF, Burns TL. Effects of smoking on the development of female reproductive cancers. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1984;73(2):371–376. doi: 10.1093/jnci/73.2.371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Stockwell HG, Lyman GH. Cigarette smoking and the risk of female reproductive cancer. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1987;157(1):35–40. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(87)80341-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Tyler CW, Jr, Webster LA, Ory HW, Rubin GL. Endometrial cancer: how does cigarette smoking influence the risk of women under age 55 years having this tumor? Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1985;151(7):899–905. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(85)90668-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Mlynarcikova A, Fickova M, Scsukova S. Ovarian intrafollicular processes as a target for cigarette smoke components and selected environmental reproductive disruptors. Endocr Regul. 2005;39(1):21–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Vanderhyden BC. Loss of ovarian function and the risk of ovarian cancer. Cell Tissue Res. 2005;322(1):117–124. doi: 10.1007/s00441-005-1100-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Duskova M, Simunkova K, Hill M, Velikova M, Kubatova J, et al. Chronic cigarette smoking alters circulating sex hormones and neuroactive steroids in premenopausal women. Physiol Res. 2012;61(1):97–111. doi: 10.33549/physiolres.932164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Felix AS, Weissfeld JL, Stone RA, Bowser R, Chivukula M, et al. Factors associated with Type I and Type II endometrial cancer. Cancer Causes Control. 2010;21(11):1851–1856. doi: 10.1007/s10552-010-9612-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Sherman ME. Theories of endometrial carcinogenesis: a multidisciplinary approach. Mod Pathol. 2000;13(3):295–308. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.3880051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Sherman ME, Sturgeon S, Brinton LA, Potischman N, Kurman RJ, et al. Risk factors and hormone levels in patients with serous and endometrioid uterine carcinomas. Mod Pathol. 1997;10(10):963–968. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Setiawan VW, Yang HP, Pike MC, McCann SE, Yu H, et al. Type I and II endometrial cancers: have they different risk factors? J Clin Oncol. 2013;31(20):2607–2618. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.48.2596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Lawrence C, Tessaro I, Durgerian S, Caputo T, Richart RM, et al. Advanced-stage endometrial cancer: contributions of estrogen use, smoking, and other risk factors. Gynecol Oncol. 1989;32(1):41–45. doi: 10.1016/0090-8258(89)90847-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Daniell HW. More advanced-stage tumors among smokers with endometrial cancer. Am J Clin Pathol. 1993;100(4):439–443. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/100.4.439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.