Summary

The EGF-stimulated ERK/MAPK pathway is a key conduit for cellular proliferation signals and a therapeutic target in many cancers. Here, we characterize two central quantitative aspects of this pathway: the mechanism by which signal strength is encoded and the response curve relating signal output to proliferation. Under steady-state conditions, we find that ERK is activated in discrete, asynchronous pulses with frequency and duration determined by extracellular concentrations of EGF spanning the physiological range. In genetically identical sister cells, cell-to-cell variability in pulse dynamics influences the decision to enter S-phase. While targeted inhibition of EGFR reduces the frequency of ERK activity pulses, inhibition of MEK reduces their amplitude. Continuous response curves measured in multiple cell lines reveal that proliferation is effectively silenced only when ERK pathway output falls below a threshold of ~10%, indicating that high-dose targeting of the pathway is necessary to achieve therapeutic efficacy.

Introduction

Signal transduction networks transmit information about the external environment of the cell and integrate these inputs to trigger discrete cell fate decisions. The biochemical events involved in signal transduction have been studied in many systems, providing a detailed view of the molecular paths through which information flows from cell surface receptors to transcription factors and other effectors of cell state. However, much less is known about how quantitative information is transmitted by these networks. In the simplest cases, the number or fraction of responding signaling molecules activated inside the cell is proportional to the extracellular concentration of the stimulating ligand (Brent, 2009). In other cases, quantitative information about a constant extracellular stimulus is carried not by the number of molecules responding (or signal “amplitude”), but by the frequency with which the pool of responding signaling molecules shifts between “on” and “off” states (and thus termed “frequency modulation”)(Cai et al., 2008; Hao and O'Shea, 2011).

While many quantitative studies of signal transduction have focused on unicellular systems, much remains to be learned in metazoans, where quantitative signaling properties play a central role in development and disease. Appropriate responses to quantitative variations in morphogen gradients are essential in developmental processes, and detailed “response curves” have been mapped in which cellular response is plotted as a continuous function of the strength of an upstream signal (Gregor et al., 2007). In cancer, key oncogenes such as c-Myc and Ras elicit different cellular responses depending on the extent to which they are activated, but these determinations have been made for only 3–5 discrete signal levels (Murphy et al., 2008; Sarkisian et al., 2007). Continuous signal-response maps spanning the full dynamic range of output for pathways involved in tumor growth and survival would facilitate rational cancer therapy by indicating the level of pathway inhibition necessary to achieve a biologically significant change in proliferation rate (Fig 1A).

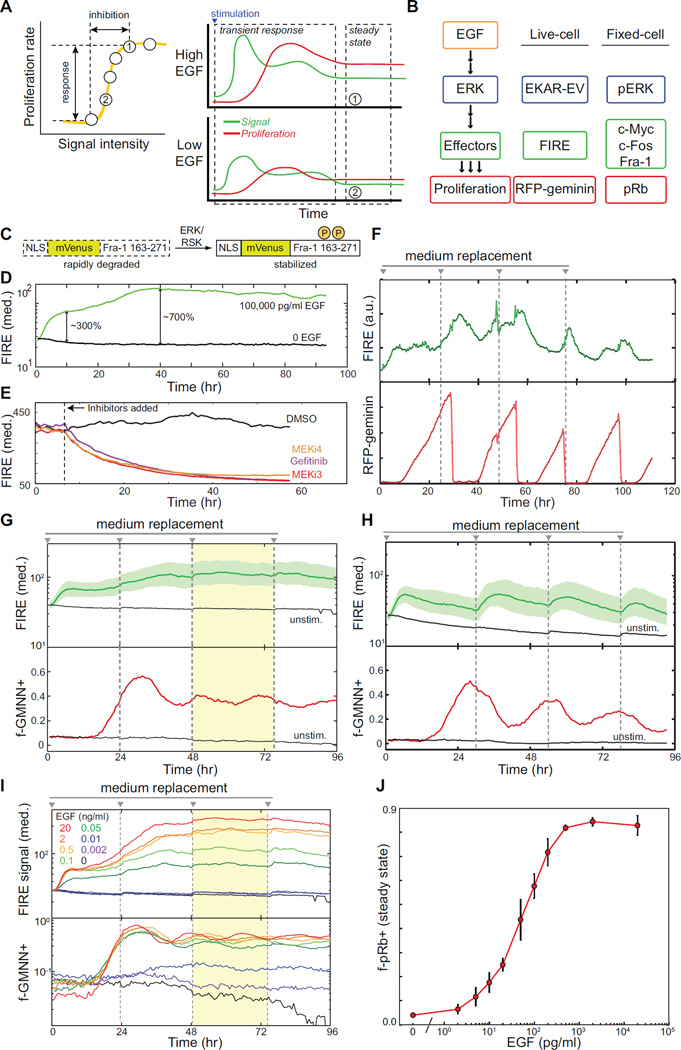

Figure 1. Steady-state signaling and proliferation in mammary epithelial cells.

A. Determining signal-response relationships. Left, a signal-response curve (yellow) relates the strength of pharmacological signal inhibition (e.g., of ERK) to the resulting reduction in proliferation (arrows). Right, this curve can be evaluated using steady-state measurements of signal intensity and proliferation rate at various EGF concentrations.

B. EGFR-ERK signaling pathway measurements used in this study.

C. Design of FIRE. Amino acids 163–271 of Fra-1 were fused in-frame to the C-terminus of mVenus, with a nuclear localization sequence (NLS) at the N-terminus.

D. Induction of FIRE fluorescence. Curves depict the median fluorescence intensity for populations of 100–1000 cells treated with EGF at time 0 (green) or untreated (black) cells.

E. Decay of FIRE fluorescence upon ERK pathway inhibition. MCF-10A cells expressing FIRE were grown in the presence of 20,000 pg/ml EGF and treated with 1 µM gefitinib (EGFR inhibitor), 1 µM PD325901 (MEKi3), or 1 µM PD184161 (MEKi4) at the indicated time. Curves depict the median fluorescence intensity for a population of 100–1000 cells for EGF-treated (green) or untreated (black) cells. Associated time-lapse images are shown in Supplemental Movie S1.

F. Live-cell measurements of ERK output (FIRE reporter) and cell cycle progression (RFP-geminin) in a single cell deprived of growth factors for 48 hours and re-stimulated at time 0 with 20,000 pg/ml EGF. Medium was replaced at ~24-hour intervals (dashed lines).

G. Population-level measurements of signaling and proliferation in mammary epithelial cells. Curves represent the median intensity of FIRE signal (green; shaded region indicates the 25th – 75th percentile) and the fraction positive for RFP-geminin (f-GMNN+, red) as determined by automated live-cell microscopy for cells treated as in (C). Yellow shaded region indicates a time period over which both FIRE and f-GMNN+ signals remain stable. Measurements were made under high-volume culture conditions (see Materials and Methods)

H. Fluctuations in signaling and proliferation under standard culture conditions. Measurements were performed as in (G), using standard culture conditions (see Materials and Methods).

I. Establishment of multiple proliferative steady states. Cells were treated and analyzed as in (G), with varying concentrations of EGF.

J. Percentage of pRb-positive cells at steady state. Error bars indicate standard deviation of six replicates. See Supplemental Fig. S1 for characterization of pRb dynamics in proliferation.

Data shown are from one experiment representative of three or more independent replicates.

The EGFR-ERK/MAPK signaling cascade is a central driver of cell proliferation in many cancers and the target of clinically relevant inhibitors. While quantitative and systems-level analyses of EGF-stimulated ERK activity have been performed (Amit et al., 2007; Chen et al., 2009; Nakakuki et al., 2010; Santos et al., 2007; Sturm et al., 2010; Zwang et al., 2011), these studies have focused on acute re-stimulation of cells with growth factors following a period of withdrawal, which induces ERK signaling within minutes, followed by proliferation many hours later. This temporal separation between signal and response obscures the signal-response relationship because multiple characteristics of the initial signal pulse - including delay, amplitude, frequency, or duration - may contribute to control of phenotype (Asthagiri et al., 2000; Traverse et al., 1994). A second difficulty with this type of experiment is the lag time in the first cell cycle following stimulation (Brooks et al., 1980). Signaling and proliferation can be more easily related when both processes have reached steady state (at the population level), because the magnitude of each can be represented by a single time-independent average (Fig 1A). Steady-state conditions also more accurately model the cellular response to chronic EGF exposure, which occurs in many physiological and tumor environments.

Here, to understand how quantitative information is transmitted by the EGFR-ERK signaling pathway, we utilize live and fixed single-cell methods to measure signal strength and dynamics under conditions of steady-state EGF stimulation. We find that this pathway incorporates both frequency- and amplitude-modulated elements: ERK is activated in discrete pulses that are integrated to set graded levels of downstream effectors. We show that inhibitors acting at different levels of the ERK cascade can modify the amplitude or the frequency of ERK activity, and we use our quantitative measurements to map a continuous signal-response relationship between ERK pathway output and proliferation rate across different inhibitors and doses.

Results

Working with MCF-10A mammary epithelial cells, which require EGF-stimulated ERK signaling for proliferation (Ethier and Moorthy, 1991), we assembled a panel of live-cell and high-content immunofluorescence (HCIF) measurements for ERK pathway signaling and proliferation (Fig. 1B). ERK activity was monitored by HCIF detection of phosphorylated ERK (pERK) and by live-cell measurement of a FRET-based ERK activity reporter, EKAR-EV, with rapid response kinetics (Harvey et al., 2008; Komatsu et al., 2011). Downstream output of the ERK pathway was monitored in fixed cells by HCIF for ERK effectors including c-Fos, c-Myc, and Fra-1, and in live cells by a newly developed live-cell reporter consisting of YFP fused to the PEST domain of Fra-1, termed FIRE (Fra-1-based integrative reporter of ERK; Fig. 1C). Because phosphorylation by ERK stabilizes the Fra-1 PEST domain (Casalino et al., 2003; Vial and Marshall, 2003), FIRE intensity increases by up to 7-fold upon ERK induction (Fig. 1D), and decays upon inhibition of ERK or EGFR (Fig. 1E). Cellular proliferation was monitored by HCIF detection of phosphorylated Rb protein (pRb) or a geminin-based live-cell reporter (Sakaue-Sawano et al., 2008), both of which initiate near the onset of S-phase and remain “on” until the beginning of the next cell cycle (Fig. S1). Control experiments confirmed that the fraction of pRb-positive (f-pRb+) cells within a population is closely correlated to the population doubling rate (Fig. S1).

Using live-cell imaging, we monitored populations of 200–1000 cells over the course of four days, allowing individual cells to be tracked for 4–5 successive cell cycles (Supplemental Movie S1). Although individual cells vary in signaling and cell cycle status over the course of the experiment (Fig. 1F), it was possible to maintain the population-average ERK signaling and proliferation at nearly constant steady-state levels between 48 and 72 hours post-stimulation (Fig. 1G). Depletion of EGF from the medium (resulting in periodic signal decay, Fig.1H) was prevented by using a high ratio of medium to cells (Kim et al., 2009; Knauer et al., 1984). Using a range of EGF concentrations, we established a series of steady-state conditions under which quantitative characteristics of ERK signaling could be linked to proliferation rates ranging from ~3% to ~80% pRb-positive (Figs. 1I,J).

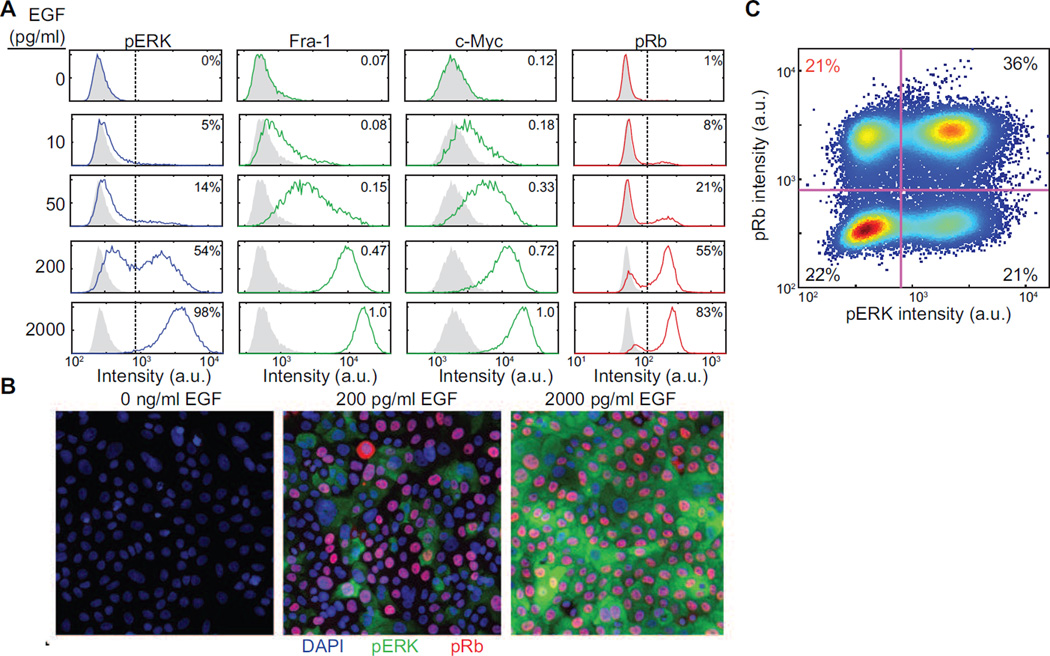

We next measured ERK network states associated with each EGF concentration under steady-state conditions (58–60 hours post-stimulation). HCIF imaging of Fra-1 revealed a detectable range for pathway output of ~15-fold, with unimodally distributed populations of cells indicative of a graded change in signal strength in response to increasing EGF (Fig. 2A). Similar behavior was observed with other ERK effectors including c-Fos, c-Myc, and Ets-1 (Fig. S2). In contrast to its downstream targets, phospho-ERK exhibited a bimodal staining pattern, in which the fraction of cells in the positive peak varied as a function of EGF, implying all-or-none regulation. Paradoxically, at intermediate EGF concentrations where only a subset of cells were pERK- or pRb- positive, the pERK-positive population did not correlate with the pRb-positive population (Fig. 2B,C), despite the absolute requirement of ERK activity for cell cycle progression.

Figure 2. Signaling states under chronic EGF stimulation.

A. Mammary epithelial cells were treated as in Fig. 1G, fixed at 58 hours after treatment, and analyzed for the indicated proteins by HCIF. Histograms indicate the distribution for a population of >5000 cells; the distribution in the absence of EGF is shown in gray for comparison. See Supplemental Fig. S2 for HCIF analysis of additional proteins.

B. Representative HCIF images for cells analyzed as in (A).

C. Quantitation of pRb+,pERK− cells cultured at steady state with 200 pg/ml EGF and analyzed as in (A).

Data shown are from one experiment representative of three or more independent replicates.

This apparent discrepancy was resolved by dynamic analysis of EKAR, the live-cell ERK activity reporter. EKAR-EV displayed intermittent bursts of activity alternating with periods of low activity, at a frequency dependent on the concentration of EGF (Fig. 3A, B). EKAR-EV emission ratios in the nucleus and cytoplasm were closely correlated (Fig. 3C) and pERK staining was distributed throughout the cell (Fig. 3D), suggesting that activity pulses were not constrained to specific subcellular domains. EKAR-EV pulses were sporadic in the absence of EGF, while low concentrations of EGF induced isolated bursts lasting 20–30 minutes (mean 27 minutes) interspersed by dormant periods of 1–4 hours (Fig. 3A). With increasing concentrations of EGF, pulses increased in duration and decreased in spacing, with individual bursts becoming indistinguishable at higher concentrations of EGF (>200 pg/ml). Thus, pRb+/pERK− cells can be observed at low EGF concentrations because the population of ERK molecules within the cell alternates between “on” (mostly active) and “off” (mostly inactive) states at least 10–20 times during a single cell cycle. Because essentially all cells within the population display pulsatory behavior (Fig. 3B and Supplemental Movie S2), the fraction of pERK+ cells observed by HCIF reflects the average fraction of time spent in the “on” state by each cell.

Figure 3. EGF-stimulated, frequency-modulated ERK activity pulses.

A, B. ERK activity in single cells under steady-state conditions. Individual MCF-10A cells expressing EKAR-EV were treated as in Fig. 1G and imaged from 48 to 70 hours after stimulation. A. EKAR-EV signal (CFP/YFP ratio) for single cells; note that the Y-axis is inverted as ERK activity induces a decrease in CFP/YFP ratio. B. EKAR-EV signal for 29 cells in each EGF concentration; each row in the heat maps represents one cell. Data shown are from one experiment representative of five independent replicates. Associated time-lapse imaging is shown in Supplemental Movie S2.

C. Comparison of nuclear and cytosolic ERK activity for an individual cell. Cells stably expressing EKAR-EV were transferred from full growth medium to 20 pg/ml EGF immediately prior to imaging. The ratio of CFP/YFP fluorescence was measured in discrete regions within the nucleus or cytosol; results are representative of all cells examined.

D. Immunofluorescence of phospho-ERK under steady-state conditions. MCF-10A cells were grown in the presence of 20 pg/ml EGF for 60 hours prior to fixation and staining. Note that in pERK-positive cells, pERK is present throughout the cell.

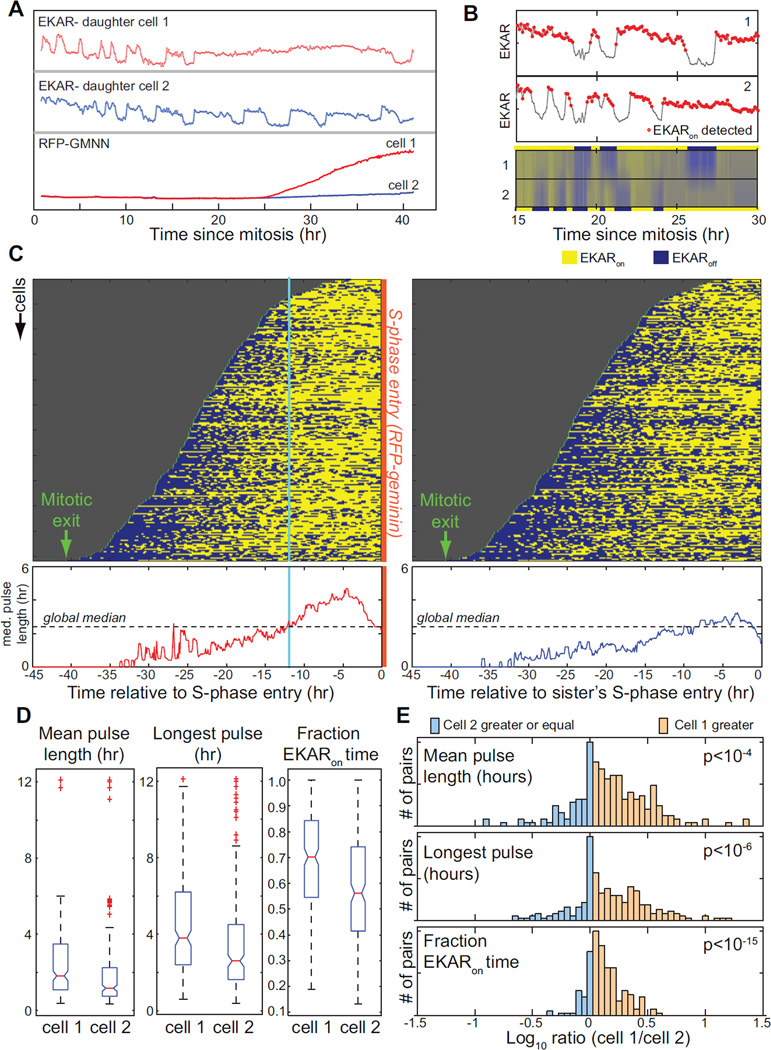

To understand how sporadic pulses of ERK activity at low EGF concentrations affect S-phase entry, we employed MCF-10A cells co-expressing EKAR-EV and RFP-geminin (Supplemental Movie S3). To limit the effects of genetic variability, local variation in media factors, and cell cycle position, we analyzed sister cell pairs in which one sister cell entered S-phase at least five hours prior to the other sister (Fig. 4A and S3). Pulses of ERK activity were identified using a combination of automated and manual scoring (Fig. 4B), and ERK activity profiles for 223 sister cell pairs were aligned by the time of RFP-geminin induction (Fig.4C). Analysis of the aligned profiles revealed a shift in ERK pulse dynamics specific to the time interval preceding S-phase entry: median pulse length rose sharply at ~12 hours prior to RFP-geminin induction among the cells entering S-phase, but not in the corresponding sister cells. This increase in pulse length suggested that longer periods of ERK activity stimulate S-phase entry. To test this idea, we performed a statistical analysis of the mean pulse length per cell, the longest pulse in each cell, and the fraction of time spent in the ERKon state. All of these metrics were significantly greater in the earlier-committing cell (“cell 1”) for both the 12 hours immediately preceding S-phase entry and for the entire interval between the previous mitosis and S-phase entry, although the differences were largest within the 12-hour period (Table S1). When cell 1 and cell 2 populations were compared as a whole (Fig. 4D), mean pulse length and longest pulse were ~50% larger in the cell 1 population (1.8 vs. 1.2 hours for mean pulse; 3.8 vs. 2.6 hours for longest pulse) and the fraction of time spent in the ERKon state was greater (70% vs. 56%). Comparison of the same pulse parameters within each pair also revealed a highly significant enhancement of ERKon time for cell 1 (Fig. 4E). In contrast, the number of pulses in cell 1 was smaller than in cell 2 for the majority of pairs (Table S1), suggesting that the length of time spent in the ERKon state, and not the number of pulses, is a significant determinant of each cell’s decision to enter S-phase.

Figure 4. Stimulation of cell cycle progression by sustained ERK activity pulses.

A. Imaging of ERK activity pulses and cell cycle progression. MCF-10A cells expressing EKAR-EV and RFP-geminin were imaged in the presence of 50 pg/ml EGF. Pairs of sister cells were analyzed in which one sister cell entered a subsequent round of DNA replication (as indicated by RFP-geminin induction) >5 hours prior to the other sister. One representative cell pair is shown; see Supplemental Fig. S3 and Movie S3 for additional examples and time-lapse images.

B. Automatic detection of ERK activity pulses. Top, regions of increased EKAR-EV activity (red circles) identified by a peak detection algorithm for a representative cell pair. Bottom, heat map of EKAR-EV signal in the same cell pair, with binary EKAR-EV values (solid blue and yellow) shown for each pair.

C. Patterns of EKAR-EV pulse dynamics prior to S-phase entry. Binarized EKAR-EV measurements for 223 cells were ordered from top to bottom by the length of the interval between the previous mitosis (green lines) and the subsequent induction of RFP-geminin (red line) in the first cell of the pair (cell 1, left); the corresponding sister cells not entering S-phase are shown at right. At bottom, the median EKARon pulse length for a sliding time window is shown; dotted line indicates the overall median pulse length for all cells. Cyan line indicates 12 hours prior to RFP-geminin induction, where median pulse length increases sharply for the cell 1 population.

D. Distribution of ERK activity parameters in cells committing to S-phase earlier (cell 1) or later (cell 2). Mean pulse length, longest pulse, and fraction of time in the ERKon state were calculated for each cell within the 12 hours preceding RFP-geminin induction (for cell 1), and within the same 12 hour period for cell 2. Red lines indicate the median, boxes the 25th – 75th percentile, dashed lines the total range, and (+) the outliers for each population. See Table S1 for values and additional analysis.

E. Pairwise comparison of ERK activity parameters. For each pair of sister cells, the ratio of the indicated ERK pulse parameters for the earlier- (cell 1) and later- (cell 2) committing cells was calculated. The logarithm of the cell 1/cell 2 ratio was plotted as a histogram to show the frequency of pairs in which the indicated parameter was larger in cell 1 (pink, >0) or in cell 2 (blue, ≤0). P-values were calculated using a paired t-test.

Data shown are collated from three independent experiments (n=24, 59, and 140).

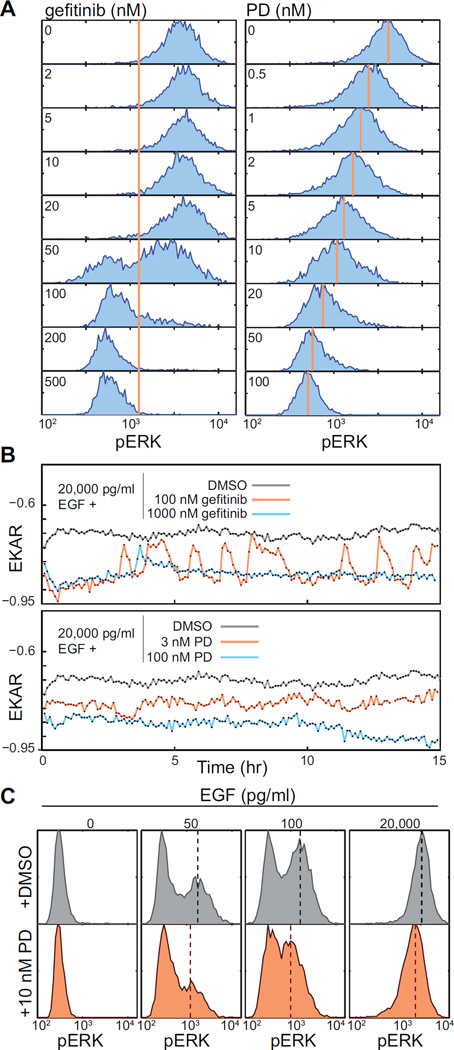

To understand the role of ERK dynamics in response to pharmacological inhibition, we evaluated the effects of the EGFR inhibitor gefitinib or the highly selective MEK inhibitor PD0325901 (PD) (Bain et al., 2007). Similar to titration with EGF, varying concentrations of gefitinib produced a bimodal shift in pERK intensity measured by HCIF (Fig. 5A). In accord, live imaging of EKAR-EV upon gefitinib addition revealed complete inhibition of the EGF-induced signal at high gefitinib concentrations, but pulsatory behavior at intermediate concentrations (Fig.5B). These data, taken from cells stimulated with saturating levels of EGF, demonstrate that ERK activity pulses are not simply the result of fluctuations in the local concentration of EGF, but are intrinsic to the intracellular signaling machinery.

Figure 5. Modulation of ERK frequency and amplitude by signaling inhibitors.

A. Distributions of pERK at steady state in the presence of 20,000 pg/ml EGF and the indicated concentrations of inhibitors. Histograms represent >5000 cells measured by HCIF after 48 hours of treatment with the indicted inhibitors. For gefitinib-treated cells, vertical red line represents the division between pERK+ and pERK- cells. For PD-treated cells, vertical red lines indicate the approximate median pERK fluorescence intensity (or “amplitude”).

B. Live-cell measurements of EKAR-EV signal (CFP/YFP ratio) upon EGFR or MEK inhibition. Mammary epithelial cells growing in the presence of 20,000 pg/ml EGF were treated with the indicated concentrations of inhibitors immediately prior to imaging at time 0.

C. Simultaneous modulation of pERK frequency and amplitude. Cells were grown at steady-state with the indicated concentrations of PD and EGF and analyzed by HCIF. Dashed lines indicate the approximate median of the pERK-positive population; a shift in this value indicates decreased amplitude of the ERK-on state.

Data shown are from one experiment representative of two or more independent replicates.

In contrast to gefitinib, and in agreement with previous work (Komatsu et al., 2011), titration of EGF-saturated cells with PD resulted in a unimodal shift from high pERK intensity to low (Fig. 5A). Consistent with these data, live imaging revealed a graded reduction in EKAR-EV intensity upon PD treatment, rather than pulsatory behavior (Fig. 5B). Using combinations of EGF and PD (Fig. 5C), it was possible to modulate both the frequency and amplitude of ERK signaling simultaneously: at 10 nM PD and 50–100 pg/ml EGF, for example, pERK retained its bimodal pattern but the intensity of the “on” population decreased by ~30%. Thus, ERK activity is frequency-modulated (FM) by quantitative variation in receptor activity but amplitude modulated (AM) by changes in MEK activity.

Because ERK activity can vary in both amplitude and frequency, measuring the integrated activity level of ERK directly poses technical challenges. We therefore turned to downstream effectors as potential indicators of integrated ERK pathway output, focusing on Fra-1 because it displayed the largest measurable dynamic range (Fig. S2). To understand how unimodal distributions of Fra-1 arise downstream of FM ERK activity, we performed a kinetic analysis of changes in effector concentration. When cells growing in full growth medium were treated with MEK inhibitor, ERK phosphorylation was fully abrogated within 10 minutes, while Fra-1 levels decayed slowly (t1/2>12 hours; Fig. 6A). A simplified kinetic model of Fra-1 stabilization based on reported half-lives for phosphorylated Fra-1 (Casalino et al., 2003) and pERK (Kleiman et al., 2011) was consistent with these decay times (Fig. 6B; see Supplemental Experimental Procedures and Tables S2 and S3 for details of model construction). Using the rate of phosphorylation of ERK as an input parameter to the model, we simulated the experimentally observed patterns of ERK pulses and found that the level of Fra-1 changed in a graded manner as a function of ERK frequency (Fig. 6C,D). This simulated behavior is consistent with the observation that the median intensity of Fra-1 changes in a graded manner as the frequency of ERK pulses varies (Fig. 2A). The model also predicts that variation over time in ERK pulse frequency, which is observed in individual cells (Fig. 3A,B) would result in slow fluctuations in Fra-1 (Fig. 6E). This prediction is confirmed in individual cells expressing the Fra-1 based FIRE reporter; at concentrations of EGF under which ERK activity is highly pulsatory (10 pg/ml; see Fig. 3A), fluctuations in Fra-1-based FIRE intensity occurred on a much slower time scale (~12 hours; Fig 6F). The sporadic nature of ERK activity pulses at intermediate EGF concentrations should also result in increased variability in effector expression, which is indeed observed as a broader distribution of Fra-1 and c-Myc at 50 pg/ml EGF (Fig. 2A).

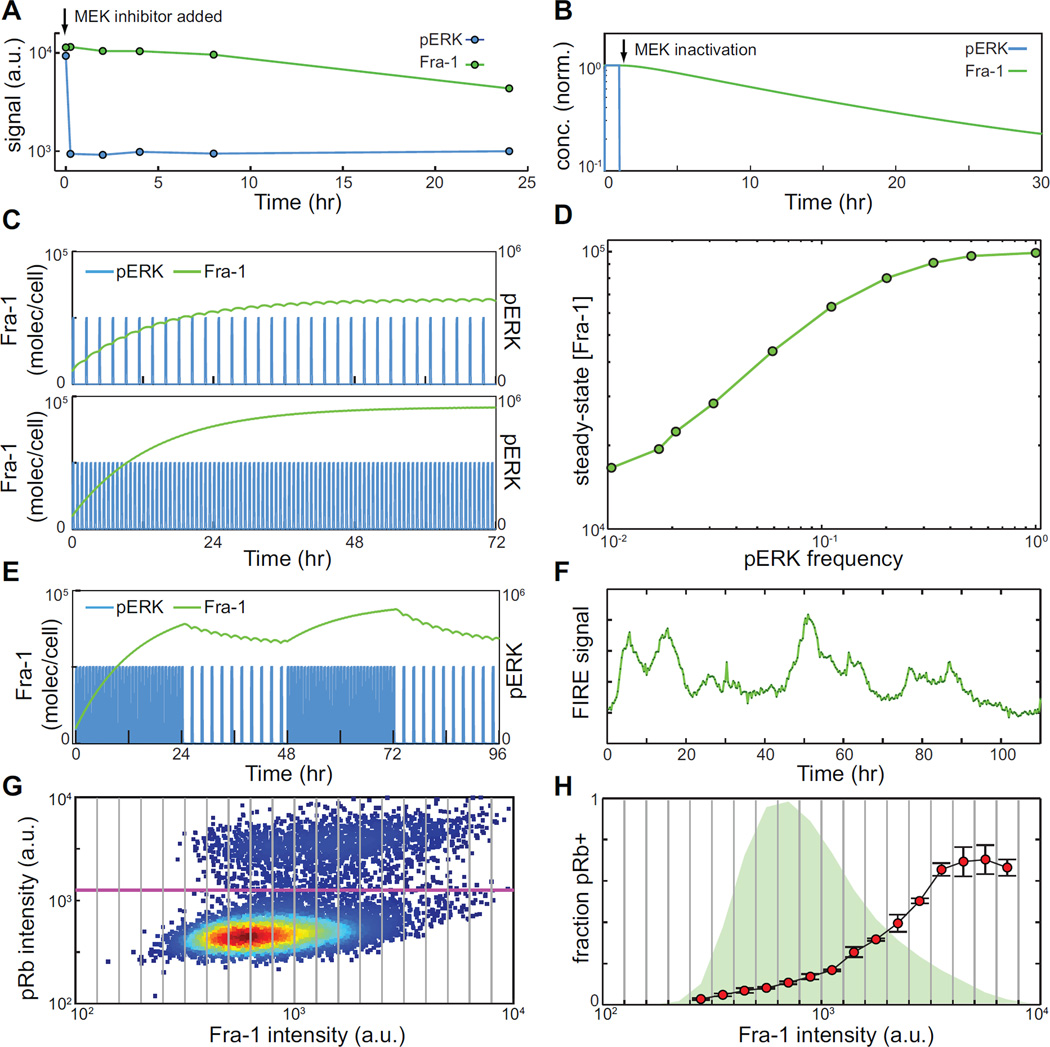

Figure 6. Integration of ERK pulses by downstream effectors.

A. Decay of endogenous pERK and Fra-1 levels upon MEK inhibition. Cells were grown in full growth medium and treated with MEK inhibitor for the indicated times prior to fixation and HCIF analysis.

B. Simulation of pERK and Fra-1 decay upon MEK inhibition. See Supplemental Experimental Procedures and Tables S2 and S3 for details of model construction and simulation.

C. Simulation of Fra-1 concentration in response to varying frequencies of ERK activity pulses.

D. Simulated steady-state levels of Fra-1 as a function of the fraction of time pERK spends in the “on” state.

E. Simulation of slow fluctuations in Fra-1 levels driven by variation in ERK pulse frequency over time.

F. Representative individual cell trace of FIRE expression at 50 pg/ml. Cells were cultured as in Fig. 1F.

G. Scatter plot of pRb and Fra-1 intensities detected for HCIF for MCF-10A cells growing at steady state (59 hr) with 50 pg/ml EGF. Pink line indicates the threshold for determining pRb+ or pRb- status; gray vertical lines indicate bins dividing Fra-1 into graded expression levels.

H. Frequency of pRb+ cells as a function of Fra-1 expression. For each Fra-1 expression bin (gray lines), the fraction of pRb+ cells was determined (red circles); error bars indicate the standard deviation for triplicate samples. The overall Fra-1 distribution is shown in green.

Data shown are from one experiment representative of three or more independent replicates.

Because the fraction of time spent in the ERKon state controls entry to S-phase (see Fig. 4), our model would further predict that individual cells with higher Fra-1 levels, which have experienced a greater integrated ERKon time, would be more likely to enter S-phase. To test this idea, we analyzed immunofluorescence data from a population of cells treated with intermediate levels (50 pg/ml) of EGF. Fra-1 expression was divided into bins, and the cells at each Fra-1 level were assessed for the frequency of pRb staining (Fig 6G,H). Across the range of Fra-1 levels, the fraction of pRb+ cells increased from <0.05 at low Fra-1 to >0.6 at high Fra-1. These data confirm that variations in ERK pulse activity, which are integrated over a 12–24 hour window by Fra-1 expression, strongly influence the proliferative activity of individual cells.

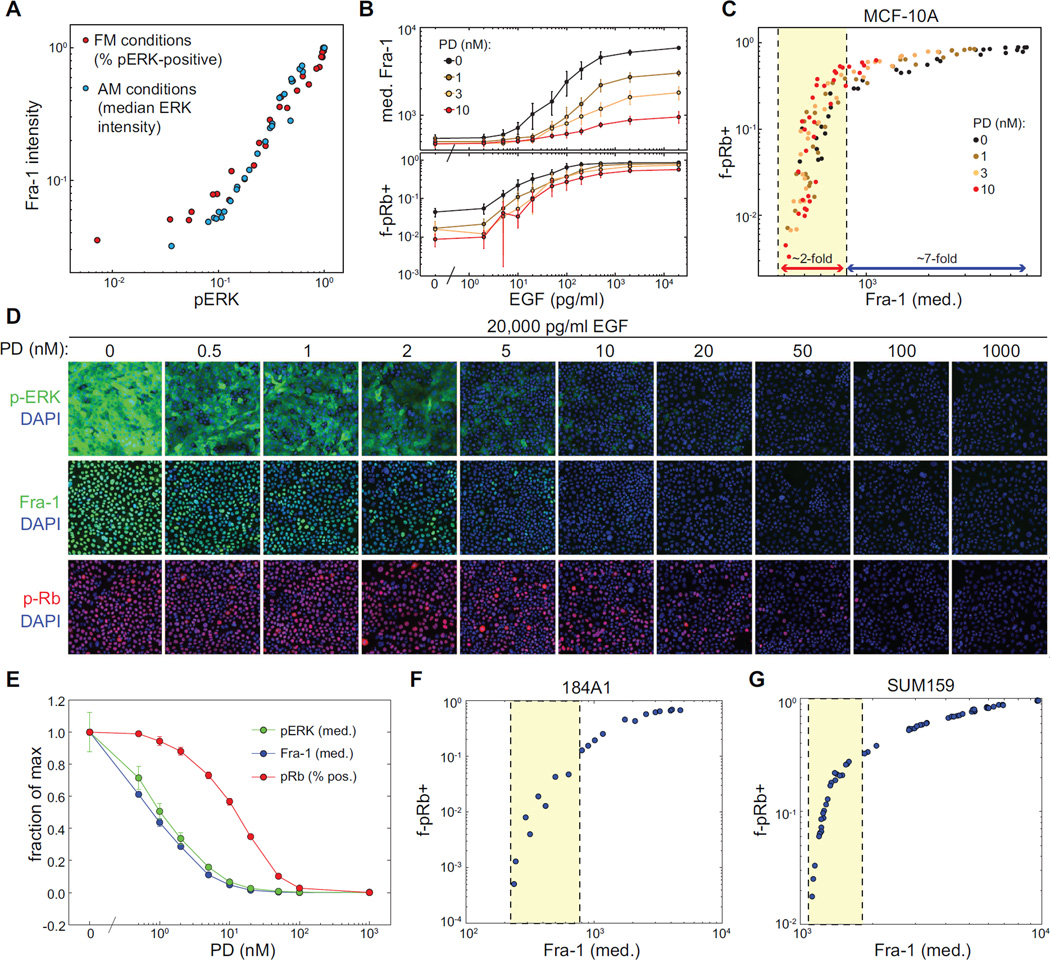

The correlation of Fra-1 intensity with both the frequency of pERK+ cells under FM conditions and the intensity of pERK staining under AM conditions (Fig. 7A) makes it a useful steady-state indicator of ERK pathway output independent of ERK dynamics. Across a wide range of EGF and PD concentrations, we compared ERK pathway output (measured by steady-state Fra-1 intensity) to proliferation rate (measured by f-pRb+; Fig. 7B,C). Strikingly, these data fit a single curvilinear relationship, suggesting that ERK output is the main quantitative factor controlling steady-state proliferation within this system. The inverted “L” shape of this relationship indicates that at low levels of ERK pathway output (yellow region in Fig. 7C), small changes in signal intensity correspond to large changes in proliferative rate, while large changes in signal intensity near the high end of the dynamic range have little impact on proliferation. This relationship predicts, and experiments confirm (Fig. 7D,E), that under saturating concentrations of EGF, inhibition of up to 85% of ERK output will have less than a 2-fold effect on proliferation rate. However, once this threshold of inhibition is passed, proliferation declines rapidly; 95% inhibition is sufficient to reduce proliferation by 10-fold. Similar curves were measured for 184A1 cells, an unrelated mammary epithelial cell line displaying similar ERK activity patterns to MCF-10A (Fig. S4 and 7F), and for SUM159, a triple-negative breast cancer line dependent on ERK for proliferation (Fig. 7G). Although the slopes of these curves vary, in all cases the relationship between ERK output and proliferation is non-linear and steepest at the lower end of the ERK dynamic range.

Figure 7. Signal-response relationship between ERK output and proliferation rate.

A. Correspondence between Fra-1 intensity and pERK at steady state. HCIF measurements for Fra-1 intensity were plotted against the fraction of pERK-positive cells under FM conditions (titration of EGF) or median pERK intensity under AM conditions (titration of PD).

B. HCIF measurements of Fra-1 intensity and f-pRb+ for combinations of EGF and PD. Values represent the mean, and error bars the standard deviation, for triplicate wells with >5000 cells each.

C. Relationship between ERK output (Fra-1 intensity) and f-pRb+ for the measurements shown in (B). Yellow region indicates the segment of the dynamic range over which proliferation changes rapidly as a function of ERK pathway output.

D. Representative HCIF images of pERK, Fra-1, and pRb of mammary epithelial cells at steady state (60 hours post-stimulation) in the presence of 20,000 pg/ml EGF and varying concentrations of PD.

E. Quantitation of fluorescence for images shown in (D).

F,G. Relationship between ERK output (Fra-1 intensity) and f-pRb+ for 184A1 mammary epithelial cells and SUM159 breast cancer cells. Cells were grown in varying concentrations of EGF and MEK inhibitor for 48 hours prior to fixation and staining. pRb and Fra-1 were measured and plotted as in (C).

Data shown are from one experiment representative of two or more independent replicates.

Discussion

Information transmission between EGFR and the cell cycle

The EGFR-ERK system functions to relay information about the extracellular concentration of growth factor ligands to the core cell cycle circuitry; here we trace the representation of quantitative information along this pathway with single-cell methods. At the level of ERK, we find that the steady-state concentration of EGF is represented by the frequency and duration of pulses of ERK activity. At the next stage of the pathway, expression levels of effectors such as Fra-1 and c-Myc are controlled by ERK activity via an integrative process, such that the total levels of these proteins are proportional to the frequency of ERK activity pulses. From a measurement perspective, exploiting this integrative control by fusing phosphorylation-regulated degradation domains to a fluorescent protein, such as in the FIRE reporter, represents an underutilized approach to generating high dynamic range biosensors for kinase activity. Finally, at the cell fate level, the average rate of entry into the S-phase of the cell cycle, a commitment that is made discrete by positive feedback loops (Yao et al., 2008), displays a non-linear dependence on the output of the ERK pathway.

We examined the quantitative relationship between ERK activity and proliferation rate at two different scales. At the level of individual cells (Fig. 3), the pattern of ERK activity is unique for each cell, and the fraction of time spent in the “on” state and the duration of ERK pulses, regulates the rate of entry into S-phase (Fig. 4). This trend may reflect the existence of downstream network motifs that respond preferentially to sustained ERK activity (Murphy et al., 2002; Yamamoto et al., 2006). Our analysis of cell-wide changes in ERK activity likely overlooks subtle effects of ERK activity localization (Harding et al., 2005). Moreover, competition of EKAR-EV with endogenous substrates for ERK and phosphatases, may perturb the output of the system, which is sensitive to substrate levels (Kim et al., 2011). Population-level studies have identified distinct periods of competency for cell cycle induction by ERK (Jones and Kazlauskas, 2001; Zwang et al., 2011); an individual cell’s decision to enter into Sphase may depend on the extent that its unique pattern of ERK pulses falls within these windows of competency, or on the timing of ERK pulses relative to other signaling events. At the population scale, however, data from thousands of cells can be averaged to identify a continuous steady-state relationship between ERK and proliferation rate (Fig. 7). The shape of this curve is conserved across multiple cell lines and indicates that in general, proliferation can be stimulated by very low levels of ERK output.

Generation of ERK activity pulses

The data obtained here at physiological EGF concentrations (Tanaka et al., 2008) in non-tumor epithelial cells with no known mutations in the EGFR-ERK pathway, suggest that frequency-modulated ERK signaling is pertinent to cells exposed chronically to EGF within normal epithelia. The bursts of ERK activity observed here are distinct from highly regular, frequency-invariant oscillations in ERK localization (Shankaran et al., 2009) and damped oscillations immediately following EGF stimulation (Cohen-Saidon et al., 2009; Nakayama et al., 2008). While the capacity of ERK to respond in an all-or-none manner has been noted (Altan-Bonnet and Germain, 2005; Das et al., 2009; Markevich et al., 2004; Qiao et al., 2007; Sturm et al., 2010), we show that transitions between the “on” and “off” state are rapid and enable a distinct mode of signaling for a central physiological regulator of proliferation. The importance of frequency modulation for signaling within this ubiquitous pathway mirrors similar findings in other pathways (Lahav et al., 2004; Tay et al., 2010) and suggests that FM signaling may be a widely used strategy for information transfer in mammalian cells.

Theoretical modeling of oscillations and bistability in the ERK pathway suggest that negative feedback is central in this behavior (Kholodenko, 2000; Markevich et al., 2004). There are several negative feedback pathways that may be involved, including internalization of activated EGFR (Wells et al., 1990), transcriptional activation of multiple DUSPs (Amit et al., 2007), stabilization of MKP1/DUSP1 by ERK-mediated phosphorylation (Brondello et al., 1997; Brondello et al., 1999), and inhibitory phosphorylation of SOS (Langlois et al., 1995), Raf (Brummer et al., 2003; Dougherty et al., 2005), or MEK (Pages et al., 1994) by ERK. Positive feedback may also control the rapid onset of ERK pulses and may arise from the allosteric activation of SOS by GTP-bound Ras (Boykevisch et al., 2006; Margarit et al., 2003), phosphorylation of RKIP by ERK (Shin et al., 2009), phosphorylation-induced degradation of the MKP-3 (Marchetti et al., 2005), or stimulatory phosphorylation of Raf by ERK (Balan et al., 2006). The presence of many redundant feedback pathways complicates analysis of the roles of individual processes. However, given the ~5–10 minute timescale of ERK pulse induction and inactivation, feedbacks involving direct phosphorylation events are more likely to be involved in pulse generation than slower processes involving transcription, degradation, or receptor internalization.

Interpretation of quantitative changes in ERK signaling

ERK phosphorylation and activity are frequently measured as indicators of the activity of upstream oncogenes such as receptor tyrosine kinases or Ras. Very often, however, the impact on cell phenotype of an observed change in ERK activity is not clear: for example, what does a two-fold change in pERK signify for the cell? Our analysis of response curves provides a prototype for translating such measurements of signal strength into expected cellular behaviors. However, the non-linear nature of the response curves measured here implies that the significance of a quantitative difference cannot be established without knowing in what region of the dynamic range ERK is operating. A two-fold change in ERK activity near the top of the dynamic range may have little effect on proliferation, while a two-fold effect on ERK activity near the bottom of the dynamic range may stimulate a 5-fold change in proliferation rate. This characteristic underscores the need for quantitative techniques for measuring signaling events. Transfer curves, which describe the input-output behavior of system components, are ubiquitous and essential in electrical and systems engineering; measuring such relationships for mammalian signaling systems will be a key step in developing clinically useful predictive models.

The quantitative characteristics of information transfer in the ERK network determined here suggest several avenues for clinical intervention in tumors dependent on this pathway for growth. Because inhibition of up to 85% of ERK output has little effect on proliferation (a finding consistent with clinical data (Bollag et al., 2009)), our findings provide rationale for combined inhibition of multiple nodes in the ERK pathway, to constrain ERK output below the threshold required for proliferation. Alternatively, it may be advantageous to identify agents which shift the quantitative relationship between ERK output and proliferation, such that less stringent ERK inhibition is required; the quantitative methods developed here will be of use in identifying such compounds. Finally, as prolonged ERK activation is more effective in committing a single cell to proliferate (Fig. 4D,E), intermittent high dose inhibition may provide a usable therapeutic index.

Experimental procedures

Experimental culture conditions

Signaling and proliferation experiments were performed in glass-bottom 12-, 24-, or 96-well plates (Mat-Tek, Matrical). For “standard” culture conditions (Fig. 1H only), the entire well bottom was pre-treated with type I collagen (BD Biosciences) to promote cell adherence and seeded with 2500–5000 cells/well in 200 ul of culture medium (in a 96-well plate). To reduce the effect of cell-mediated EGF depletion, all other experiments were performed in “high-volume” culture conditions, in which wells were pre-treated with a 3–10 µl droplet of collagen solution (depending on the size of the plate) to create a region of high adherence ~4–6 mm in diameter (area ~0.1–0.3 cm2). Cells (2×103 – 1 × 104) were then seeded directly on the collagen-coated region; during the course of the experiments, cells remained confined to the coated region, within which they were 50–100% confluent. Wells were then filled with the practical maximum volume of medium (0.4, 2.5, or 5 ml/well in 96, 24, or 12-well plates, respectively) and replenished daily by removing 80% of the culture volume and adding an equivalent volume of fresh medium.

For steady-state experiments, cells were initially plated in full growth medium to promote adherence, and then shifted to GM-GFS for 2 days. After this starvation period, medium was replaced with GM-GFS supplemented with varying concentrations of EGF; this time point is designated “time 0”. For the duration of the experiment (up to 96 hours), medium were replaced daily as described above. Importantly, while serum and insulin are required for long-term propagation of MCF-10A cells, we found that these cells will proliferate normally in response to EGF alone for at least 2 weeks (data not shown). All steady-state experiments were performed within this time window to enable EGF-stimulated signaling and proliferation to be analyzed in isolation from signals induced by insulin or growth factors present in the serum.

For sister-cell experiments, cells were plated as above in full growth medium and shifted to GMGFS supplemented with 50 pg/ml EGF immediately prior to beginning live-cell microscopy. This protocol allowed a large fraction of the population to enter S/G2 phase and become poised for cell division prior to imaging; cells dividing during the imaging phase were identified manually immediately following division and then tracked using automated routines (see below) through their subsequent cell cycles.

Live-cell microscopy

Time-lapse images were captured with a 20× 0.75NA objective on Nikon Eclipse Ti or Applied Precision Instruments Deltavision inverted fluorescence microscopes fitted with environmental chambers; cells were maintained at 37° C and ~5% CO2 for the duration of the experiments. Images were collected at intervals of 5–20 minutes using a Hammamatsu Orca-ER digital camera with 2×2 binning. For higher-frequency imaging (<10-minute intervals), neutral density filters were used to reduce phototoxicity.

High-content immunofluorescence

Following growth and treatment as indicated on glass-bottom 96-well plates, cells were fixed for 15 minutes at room temperature with a freshly prepared solution of 2% paraformaldehyde in PBS and permeabilized with 100% methanol; rapid fixation was essential to prevent decay of the pERK signal. Samples were then stained with primary and secondary antibodies and scanned on an Applied Precision Cellworx instrument with a 10× objective.

Image processing

Immunofluorescence image analysis and was performed in MATLAB as previously described (Worster et al., 2012), using routines derived from the CellProfiler platform (Lamprecht et al., 2007). Briefly, image segmentation was performed on the nuclear (DAPI-stained) image for each field; following background subtraction, the fluorescence intensity for each channel was calculated as the mean pixel value for either the nuclear or cytoplasmic region of each cell.

Population-level live-cell analysis of FIRE and RFP-geminin was performed as for immunofluorescence, using NLS-mCerulean as the segmentation marker. FIRE and RFP-geminin signals were normalized to the NLS-mCerulean intensity to correct for changes in cell shape. Segmentation and quantitation were performed independently for each time point. Analysis of FIRE and RFP-geminin in individual live cells for time periods of >48 hours was performed manually, to avoid tracking errors resulting from failure of automated tracking to identify cell division events.

Analysis of EKAR-EV was performed using a custom MATLAB algorithm, and FRET intensity was calculated as the mean CFP/YFP ratio (calculated pixel-by-pixel on background-subtracted images) for a dilated nuclear region that included both cytoplasmic and nuclear regions. To avoid the introduction of non-linearities into the FRET measurement, the CFP-excitation, YFP-emission channel was not used (Birtwistle et al., 2011). Analysis of EKAR-EV activity pulses was performed automatically using MATLAB; transitions between the ERK “on” and “off “ state were identified as peaks in a vector calculated by subtracting the CFP/YFP ratio in frame n from that in frame n-3, followed by manual editing (blinded to cell fate) to correct errors.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

Imaging facilities were provided by the Institute of Chemistry and Cell Biology and the Nikon Imaging Center at Harvard Medical School. Plasmid DNA for reporter constructs was provided by K. Aoki (EKAR-EV), A. Miyawaki (geminin), A. Bradley (PiggyBAC), and the Harvard Institute of Proteomics (Fra-1). We thank S. Spencer and Y.P. Hung for advice on the manuscript. This work was supported by the US National Institutes of Health (5-R01-CA105134-07 to J.S.B.) and by a Department of Defense Breast Cancer Research Program postdoctoral fellowship (W81XWH-08-1-0609 to J.G.A.).

References

- Altan-Bonnet G, Germain RN. Modeling T cell antigen discrimination based on feedback control of digital ERK responses. PLoS Biol. 2005;3:e356. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0030356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amit I, Citri A, Shay T, Lu Y, Katz M, Zhang F, Tarcic G, Siwak D, Lahad J, Jacob-Hirsch J, et al. A module of negative feedback regulators defines growth factor signaling. Nat Genet. 2007;39:503–512. doi: 10.1038/ng1987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asthagiri AR, Reinhart CA, Horwitz AF, Lauffenburger DA. The role of transient ERK2 signals in fibronectin- and insulin-mediated DNA synthesis. J Cell Sci. 2000;113(Pt 24):4499–4510. doi: 10.1242/jcs.113.24.4499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bain J, Plater L, Elliott M, Shpiro N, Hastie CJ, McLauchlan H, Klevernic I, Arthur JS, Alessi DR, Cohen P. The selectivity of protein kinase inhibitors: a further update. Biochem J. 2007;408:297–315. doi: 10.1042/BJ20070797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balan V, Leicht DT, Zhu J, Balan K, Kaplun A, Singh-Gupta V, Qin J, Ruan H, Comb MJ, Tzivion G. Identification of novel in vivo Raf-1 phosphorylation sites mediating positive feedback Raf-1 regulation by extracellular signal-regulated kinase. Mol Biol Cell. 2006;17:1141–1153. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E04-12-1123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birtwistle MR, von Kriegsheim A, Kida K, Schwarz JP, Anderson KI, Kolch W. Linear approaches to intramolecular Forster resonance energy transfer probe measurements for quantitative modeling. PLoS One. 2011;6:e27823. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0027823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bollag G, Hirth P, Tsai J, Zhang J, Ibrahim PN, Cho H, Spevak W, Zhang C, Zhang Y, Habets G, et al. Clinical efficacy of a RAF inhibitor needs broad target blockade in BRAF-mutant melanoma. Nature. 2009;467:596–599. doi: 10.1038/nature09454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boykevisch S, Zhao C, Sondermann H, Philippidou P, Halegoua S, Kuriyan J, Bar-Sagi D. Regulation of ras signaling dynamics by Sos-mediated positive feedback. Curr Biol. 2006;16:2173–2179. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2006.09.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brent R. Cell signaling: what is the signal and what information does it carry? FEBS Lett. 2009;583:4019–4024. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2009.11.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brondello JM, Brunet A, Pouyssegur J, McKenzie FR. The dual specificity mitogenactivated protein kinase phosphatase-1 and-2 are induced by the p42/p44MAPK cascade. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:1368–1376. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.2.1368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brondello JM, Pouyssegur J, McKenzie FR. Reduced MAP kinase phosphatase-1 degradation after p42/p44MAPK-dependent phosphorylation. Science. 1999;286:2514–2517. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5449.2514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks RF, Bennett DC, Smith JA. Mammalian cell cycles need two random transitions. Cell. 1980;19:493–504. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(80)90524-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brummer T, Naegele H, Reth M, Misawa Y. Identification of novel ERK-mediated feedback phosphorylation sites at the C-terminus of B-Raf. Oncogene. 2003;22:8823–8834. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai L, Dalal CK, Elowitz MB. Frequency-modulated nuclear localization bursts coordinate gene regulation. Nature. 2008;455:485–490. doi: 10.1038/nature07292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casalino L, De Cesare D, Verde P. Accumulation of Fra-1 in ras-transformed cells depends on both transcriptional autoregulation and MEK-dependent posttranslational stabilization. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23:4401–4415. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.12.4401-4415.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen WW, Schoeberl B, Jasper PJ, Niepel M, Nielsen UB, Lauffenburger DA, Sorger PK. Input-output behavior of ErbB signaling pathways as revealed by a mass action model trained against dynamic data. Mol Syst Biol. 2009;5:239. doi: 10.1038/msb.2008.74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen-Saidon C, Cohen AA, Sigal A, Liron Y, Alon U. Dynamics and variability of ERK2 response to EGF in individual living cells. Mol Cell. 2009;36:885–893. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.11.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Das J, Ho M, Zikherman J, Govern C, Yang M, Weiss A, Chakraborty AK, Roose JP. Digital signaling and hysteresis characterize ras activation in lymphoid cells. Cell. 2009;136:337–351. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.11.051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dougherty MK, Muller J, Ritt DA, Zhou M, Zhou XZ, Copeland TD, Conrads TP, Veenstra TD, Lu KP, Morrison DK. Regulation of Raf-1 by direct feedback phosphorylation. Mol Cell. 2005;17:215–224. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2004.11.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ethier SP, Moorthy R. Multiple growth factor independence in rat mammary carcinoma cells. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 1991;18:73–81. doi: 10.1007/BF01980969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gregor T, Tank DW, Wieschaus EF, Bialek W. Probing the limits to positional information. Cell. 2007;130:153–164. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.05.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hao N, O'Shea EK. Signal-dependent dynamics of transcription factor translocation controls gene expression. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2011;19:31–39. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harding A, Tian T, Westbury E, Frische E, Hancock JF. Subcellular localization determines MAP kinase signal output. Curr Biol. 2005;15:869–873. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2005.04.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harvey CD, Ehrhardt AG, Cellurale C, Zhong H, Yasuda R, Davis RJ, Svoboda K. A genetically encoded fluorescent sensor of ERK activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:19264–19269. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0804598105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones SM, Kazlauskas A. Growth-factor-dependent mitogenesis requires two distinct phases of signalling. Nat Cell Biol. 2001;3:165–172. doi: 10.1038/35055073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kholodenko BN. Negative feedback and ultrasensitivity can bring about oscillations in the mitogen-activated protein kinase cascades. Eur J Biochem. 2000;267:1583–1588. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.2000.01197.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim JH, Kushiro K, Graham NA, Asthagiri AR. Tunable interplay between epidermal growth factor and cell-cell contact governs the spatial dynamics of epithelial growth. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:11149–11153. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0812651106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim Y, Paroush Z, Nairz K, Hafen E, Jimenez G, Shvartsman SY. Substratedependent control of MAPK phosphorylation in vivo. Mol Syst Biol. 2011;7:467. doi: 10.1038/msb.2010.121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleiman LB, Maiwald T, Conzelmann H, Lauffenburger DA, Sorger PK. Rapid phospho-turnover by receptor tyrosine kinases impacts downstream signaling and drug binding. Mol Cell. 2011;43:723–737. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2011.07.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knauer DJ, Wiley HS, Cunningham DD. Relationship between epidermal growth factor receptor occupancy and mitogenic response. Quantitative analysis using a steady state model system. J Biol Chem. 1984;259:5623–5631. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Komatsu N, Aoki K, Yamada M, Yukinaga H, Fujita Y, Kamioka Y, Matsuda M. Development of an optimized backbone of FRET biosensors for kinases and GTPases. Mol Biol Cell. 2011;22:4647–4656. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E11-01-0072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lahav G, Rosenfeld N, Sigal A, Geva-Zatorsky N, Levine AJ, Elowitz MB, Alon U. Dynamics of the p53-Mdm2 feedback loop in individual cells. Nat Genet. 2004;36:147–150. doi: 10.1038/ng1293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamprecht MR, Sabatini DM, Carpenter AE. CellProfiler: free, versatile software for automated biological image analysis. Biotechniques. 2007;42:71–75. doi: 10.2144/000112257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langlois WJ, Sasaoka T, Saltiel AR, Olefsky JM. Negative feedback regulation and desensitization of insulin- and epidermal growth factor-stimulated p21ras activation. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:25320–25323. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.43.25320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marchetti S, Gimond C, Chambard JC, Touboul T, Roux D, Pouyssegur J, Pages G. Extracellular signal-regulated kinases phosphorylate mitogen-activated protein kinase phosphatase 3/DUSP6 at serines 159 and 197, two sites critical for its proteasomal degradation. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25:854–864. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.2.854-864.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Margarit SM, Sondermann H, Hall BE, Nagar B, Hoelz A, Pirruccello M, Bar-Sagi D, Kuriyan J. Structural evidence for feedback activation by Ras.GTP of the Ras-specific nucleotide exchange factor SOS. Cell. 2003;112:685–695. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00149-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markevich NI, Hoek JB, Kholodenko BN. Signaling switches and bistability arising from multisite phosphorylation in protein kinase cascades. J Cell Biol. 2004;164:353–359. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200308060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy DJ, Junttila MR, Pouyet L, Karnezis A, Shchors K, Bui DA, Brown-Swigart L, Johnson L, Evan GI. Distinct thresholds govern Myc's biological output in vivo. Cancer Cell. 2008;14:447–457. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2008.10.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy LO, Smith S, Chen RH, Fingar DC, Blenis J. Molecular interpretation of ERK signal duration by immediate early gene products. Nat Cell Biol. 2002;4:556–564. doi: 10.1038/ncb822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakakuki T, Birtwistle MR, Saeki Y, Yumoto N, Ide K, Nagashima T, Brusch L, Ogunnaike BA, Okada-Hatakeyama M, Kholodenko BN. Ligand-specific c-Fos expression emerges from the spatiotemporal control of ErbB network dynamics. Cell. 2010;141:884–896. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.03.054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakayama K, Satoh T, Igari A, Kageyama R, Nishida E. FGF induces oscillations of Hes1 expression and Ras/ERK activation. Curr Biol. 2008;18:R332–R334. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2008.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pages G, Brunet A, L'Allemain G, Pouyssegur J. Constitutive mutant and putative regulatory serine phosphorylation site of mammalian MAP kinase kinase (MEK1) EMBO J. 1994;13:3003–3010. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06599.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiao L, Nachbar RB, Kevrekidis IG, Shvartsman SY. Bistability and oscillations in the Huang-Ferrell model of MAPK signaling. PLoS Comput Biol. 2007;3:1819–1826. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.0030184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakaue-Sawano A, Kurokawa H, Morimura T, Hanyu A, Hama H, Osawa H, Kashiwagi S, Fukami K, Miyata T, Miyoshi H, et al. Visualizing spatiotemporal dynamics of multicellular cell-cycle progression. Cell. 2008;132:487–498. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.12.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santos SD, Verveer PJ, Bastiaens PI. Growth factor-induced MAPK network topology shapes Erk response determining PC-12 cell fate. Nat Cell Biol. 2007;9:324–330. doi: 10.1038/ncb1543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarkisian CJ, Keister BA, Stairs DB, Boxer RB, Moody SE, Chodosh LA. Dose-dependent oncogene-induced senescence in vivo and its evasion during mammary tumorigenesis. Nat Cell Biol. 2007;9:493–505. doi: 10.1038/ncb1567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shankaran H, Ippolito DL, Chrisler WB, Resat H, Bollinger N, Opresko LK, Wiley HS. Rapid and sustained nuclear-cytoplasmic ERK oscillations induced by epidermal growth factor. Mol Syst Biol. 2009;5:332. doi: 10.1038/msb.2009.90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shin SY, Rath O, Choo SM, Fee F, McFerran B, Kolch W, Cho KH. Positive- and negative-feedback regulations coordinate the dynamic behavior of the Ras-Raf-MEK-ERK signal transduction pathway. J Cell Sci. 2009;122:425–435. doi: 10.1242/jcs.036319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sturm OE, Orton R, Grindlay J, Birtwistle M, Vyshemirsky V, Gilbert D, Calder M, Pitt A, Kholodenko B, Kolch W. The mammalian MAPK/ERK pathway exhibits properties of a negative feedback amplifier. Sci Signal. 2010;3:ra90. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2001212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka Y, Ogasawara T, Asawa Y, Yamaoka H, Nishizawa S, Mori Y, Takato T, Hoshi K. Growth factor contents of autologous human sera prepared by different production methods and their biological effects on chondrocytes. Cell Biol Int. 2008;32:505–514. doi: 10.1016/j.cellbi.2007.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tay S, Hughey JJ, Lee TK, Lipniacki T, Quake SR, Covert MW. Single-cell NF-kappaB dynamics reveal digital activation and analogue information processing. Nature. 2010;466:267–271. doi: 10.1038/nature09145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Traverse S, Seedorf K, Paterson H, Marshall CJ, Cohen P, Ullrich A. EGF triggers neuronal differentiation of PC12 cells that overexpress the EGF receptor. Curr Biol. 1994;4:694–701. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(00)00154-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vial E, Marshall CJ. Elevated ERK-MAP kinase activity protects the FOS family member FRA-1 against proteasomal degradation in colon carcinoma cells. J Cell Sci. 2003;116:4957–4963. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wells A, Welsh JB, Lazar CS, Wiley HS, Gill GN, Rosenfeld MG. Ligand-induced transformation by a noninternalizing epidermal growth factor receptor. Science. 1990;247:962–964. doi: 10.1126/science.2305263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Worster DT, Schmelzle T, Solimini NL, Lightcap ES, Millard B, Mills GB, Brugge JS, Albeck JG. Akt and ERK Control the Proliferative Response of Mammary Epithelial Cells to the Growth Factors IGF-1 and EGF Through the Cell Cycle Inhibitor p57Kip2. Sci Signal. 2012;5:ra19. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2001986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto T, Ebisuya M, Ashida F, Okamoto K, Yonehara S, Nishida E. Continuous ERK activation downregulates antiproliferative genes throughout G1 phase to allow cell-cycle progression. Curr Biol. 2006;16:1171–1182. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2006.04.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yao G, Lee TJ, Mori S, Nevins JR, You L. A bistable Rb-E2F switch underlies the restriction point. Nat Cell Biol. 2008;10:476–482. doi: 10.1038/ncb1711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zwang Y, Sas-Chen A, Drier Y, Shay T, Avraham R, Lauriola M, Shema E, Lidor-Nili E, Jacob-Hirsch J, Amariglio N, et al. Two phases of mitogenic signaling unveil roles for p53 and EGR1 in elimination of inconsistent growth signals. Mol Cell. 2011;42:524–535. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2011.04.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.