Abstract

Anaplastic thyroid cancer (ATC) is among the most lethal types of cancers, characterized as a fast-growing and highly invasive thyroid tumor that is unresponsive to surgery and radioiodine, blunting therapeutic efficacy. Classically, genetic alterations in tumor suppressor TP53 are frequent, and cumulative alterations in different signaling pathways, such as MAPK and PI3K, are detected in ATC. Recently, deregulation in microRNAs (miRNAs), a class of small endogenous RNAs that regulate protein expression, has been implicated in tumorigenesis and cancer progression. Deregulation of miRNA expression is detected in thyroid cancer. Upregulation of miRNAs, such as miR-146b, miR-221, and miR-222, is observed in ATC and also in differentiated thyroid cancer (papillary and follicular), indicating that these miRNAs' overexpression is essential in maintaining tumorigenesis. However, specific miRNAs are downregulated in ATC, such as those of the miR-200 and miR-30 families, which are important negative regulators of cell migration, invasion, and epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT), processes that are overactivated in ATC. Therefore, molecular interference to restore the expression of tumor suppressor miRNAs, or to blunt overexpressed oncogenic miRNAs, is a promising therapeutic approach to ameliorate the treatment of ATC. In this review, we will explore the importance of miRNA deregulation for ATC cell biology.

1. Introduction

Anaplastic thyroid cancer (ATC) is the most lethal histotype of thyroid cancer, responsible for more than one-third of thyroid cancer-related deaths [1]. The fast-growing nature of this type of cancer and its refractoriness to radioiodine treatment due to tumors not concentrating iodine limit the efficacy of therapeutic interventions [2]. Thus, ATC patients display a rapidly progressive disease that may cause death within six months [3].

ATC's clinical pathology is characterized by the aggressive behavior of cancer cells, which results in a rapid enlargement of the neck tumor to invade adjacent tissue and migrate as distant metastases, usually with secondary sites in the lungs, bone, and brain [4]. During this process, activation of epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT) is a key feature of anaplastic transformation. Moreover, loss of expression of differentiation markers (iodine metabolizing genes) and, consequently, loss of iodine uptake are markers of this process that negatively impact on ATC radioiodine responsiveness.

Unlike the differentiated histotypes of thyroid cancer, papillary thyroid cancer (PTC) and follicular thyroid cancer (FTC) that show a single driver mutation pattern, the tumorigenesis of ATC is not completely understood: it may arise de novo or from a preexisting well-differentiated cancer (PTC/FTC). The most prevalent genetic alterations in ATC are mutations in the TP53 gene at codon 273 as observed in more than 70% of ATC samples [5, 6], leading to p53 loss of function. Moreover, mutations in the telomerase gene (TERT) are frequently seen in aggressive thyroid cancers, including in poorly differentiated and anaplastic thyroid cancers [7, 8], and lead to increased transcriptional activity of TERT. However, additional mutations in MAPK signaling (RAS and BRAF genes), in PI3K signaling (PIKCA and PTEN), and in Wnt signaling (β-catenin and APC) have also been detected in ATC [9–12].

Animal models have contributed to an understanding of the molecular transformation of ATC. The thyroid cancer progression hypothesis is corroborated by a transgenic mouse model for the early activation of the BRAF T1799A oncogene restricted to the thyroid gland (Tg-BRAF) that is affected by high penetrance PTC that undergoes temporal dedifferentiation [13]. Molecular analysis of Tg-BRAF mice-derived tumors reveals the deregulation of TGFβ signaling upon prolonged stimulation of the BRAF oncogene, with enhanced TGFβ signaling transduction and a shift to EMT by ZEB1 and ZEB2 transcription factor activation [14]. Another transgenic model with BRAF activation in adult mice also gives rise to differentiated thyroid cancer; however, progression to ATC requires TP53 gene deletion [15], corroborating the multistep cancer progression hypothesis for ATC. A mouse model harboring defective PI3K signaling gives rise to aggressive thyroid cancer. Transgenic mice carrying deletions of Pten and TP53 [Pten, p53](thyr−/−) develop ATC with loss of expression of the thyroid transcription factors, Nkx2-1, Pax-8, and Foxe1, and thyroid differentiation markers, Nis, Tpo, Tg, Tshr, and Duox [16]. [Pten, p53](thyr−/−) mice thyroid tumors undergo TGFβ signaling induced EMT and demonstrate increased pSMAD2 and vimentin levels, but loss of E-cadherin expression.

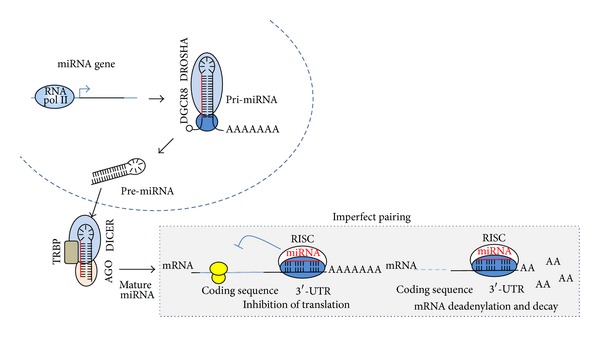

Recently, a pivotal role for microRNAs (miRNAs) in cancer has emerged with increasing evidence showing that they may drive and potentiate oncogenesis. The miRNAs are a class of small noncoding RNAs (~20 nt) that regulates posttranscriptional gene expression. These miRNAs are transcribed as long primary RNAs that undergo sequential cleavages by Drosha and Dicer ribonucleases in the nucleus and cytoplasm, respectively, to yield mature miRNA. In turn, mature miRNA associates with the protein complex RISC (RNA-induced silencing complex), which directs pairing with the 3′-UTR region of target mRNAs. Imperfect pairing leads to translational blockage of target mRNA and, also, mRNA deadenylation and decay (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Biogenesis of miRNA. Transcription of miRNA by RNA polymerase II yields a long primary transcript (pri-miRNA) that contains a cap 5′ and poly-A tail. The complex DROSHA/DGCR8 cleaves pri-miRNA and gives rise to an miRNA precursor (pre-miRNA) that is exported to the cytoplasm and further processed by DICER endonuclease. An miRNA duplex associates with the RISC complex and retains the mature strand of miRNA. This complex directs imperfect binding to 3′-UTR region of target mRNA, leading to a reduction in protein levels via translation blockage and mRNA deadenylation and decay.

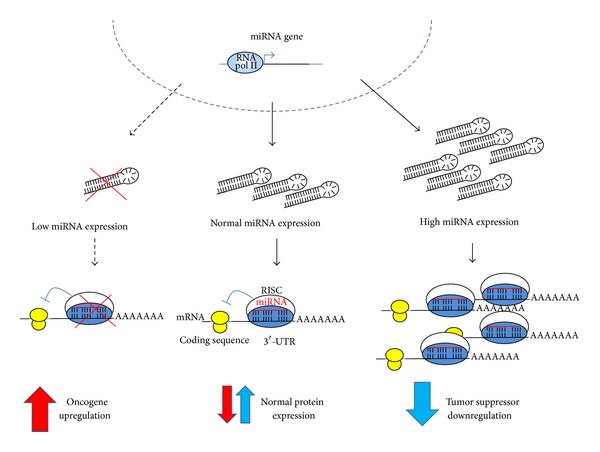

Essentially, miRNA deregulation in cancer is oncogenic (oncomiR) under two different conditions: (a) when overexpressed, miRNAs may block tumor suppressor gene translation or (b) when underexpressed, miRNAs may derepress protooncogene mRNA translation (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Some miRNAs act as oncomiRs. Deregulation of miRNA changes physiological protein level balances and enhances the oncogenic process where (1) low expression of an miRNA may enhance protein translation of an oncogenic protein or (2) high expression of an miRNA may repress the translation of a tumor suppressor gene. Both situations may occur concomitantly in cancer as observed in anaplastic thyroid cancer.

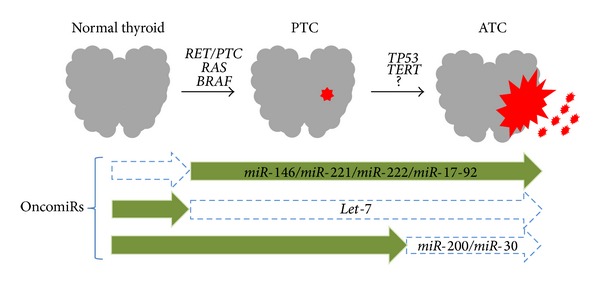

Deregulation of miRNA in thyroid cancer was initially described by He et al. in a group of PTCs [17]. The same group of upregulated miRNAs, such as miR-146b, miR-221, and miR-222, is commonly detected in ATC and in differentiated thyroid cancers (papillary and follicular histotypes) [18] and also in a fraction of benign nodules [17, 19], indicating that persistent expression of these miRNAs may be necessary to maintain tumorigenesis. However, ATC also shows exclusive reduction of certain miRNAs with tumor suppressor properties, indicating a role for these miRNAs in tumor aggressiveness (Figure 3). Investigating tumour samples from a group of ten ATC patients by microarray analysis, the seminal study of Visone et al. [20] revealed the repression of miR-30d, miR-125b, miR-26a, and miR-30a-5p. In addition, another study showed a reduction of several members of the let-7 and miR-200 family of miRNAs [21] and overexpression of miR-221, miR-222, and miR-125a-3p.

Figure 3.

Thyroid oncogenesis and miRNAs. Activation of MAPK oncogenes by mutations or rearrangements leads to PTC. Progression to ATC may be associated with the acquisition of additional genetic alterations such as TP53 mutations. Deregulation of miRNA occurs during thyroid oncogenesis, with specific upregulation of miRNAs such as miR-146, miR-221, miR-222, and miR-17-92 cluster, and loss of let-7 expression, in both PTC and ATC. Exclusive downregulation of miRNAs, such as miR-200 and miR-30, is observed in ATC.

In this review, we will explore some aspects of the deregulated miRNA found in anaplastic thyroid cancer to address the molecular biology and signaling pathways implicated in the clinical-pathological characteristics of this type of cancer (Table 1).

Table 1.

Validated targets for deregulated miRNAs in ATC.

| miRNAs | Validated targets | Cellular processes | References | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Downregulated miRs | miR-200 family | ZEB1 | ZEB2 | β-Catenin | EMT and proliferation | [21, 67] |

| miR-30 family | Beclin1 | EZH2 | VIM | Autophagy, chromatin condensation, and EMT | [30, 33, 67] | |

| let-7 family | RAS | HMGA2 | LIN28 | Proliferation, histone modification, and stemness | [67, 68] | |

| miR-25 | EZH2 | BIM | KLF4 | Chromatin condensation and apoptosis | [30, 67] | |

| miR-125 | MMP1 | HMGA2 | LIN28A | Invasion, histone modification, and stemness | [20, 67, 69] | |

|

| ||||||

| Upregulated miRs | miR-221/miR-222 | p27 | RECK | PTEN | Cell cycle, growth, and invasion | [20, 67] |

| miR-17-92 cluster | p21 | TIMP3 | PTEN | Cell growth and invasion | [45, 67] | |

| miR-146a/miR-146b | NFκB | THRB | SMAD4 | Cell differentiation, proliferation, and invasion | [52, 67, 70, 71] | |

2. Downregulated miRNAs in ATC

Specific miRNAs are reduced in thyroid cancer, such as the let-7 family, but other miRNAs, such as the miR-200 and miR-30 families, are exclusively downregulated in ATC, indicating that the latter miRNAs may play a role in the acquisition of more aggressive tumor characteristics (i.e., enhanced cell invasion and migration).

2.1. miR-200 Family

The miR-200 family is composed of the miR-200a, miR-200b, and miR-200c genes, which are usually downregulated in ATC [21]. The miR-200a and miR-200b genes make up a cluster located on chromosome 1, while the miR-200c gene is located on chromosome 12. An important transcriptional activator of miR-200 is p53, which binds to the promoter region of miR-200c at multiple sites. Interestingly, a TP53 mutation at a DNA binding domain as present in ATC impairs downstream transcriptional activation of miR-200 [22]. Moreover, p53 is an important controller of tumor suppressor miRNAs, such as those of the miR-34 family, and also influences miRNA processing [23], besides having a classical role in DNA repair and genomic stability. Another signaling pathway that influences miR-200 expression is the EGF pathway. Overexpression of the EGF receptor, EGFR, is observed in ATC [24], while EGFR knockdown in ATC cells restores miR-200 expression and represses the expression of mesenchymal markers [25]. Classically, TGFβ signaling induces epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT), via the transcriptional activation of ZEB1 and ZEB2 [21], inducing a mesenchymal phenotype, with the expression of vimentin and repression of E-cadherin as observed in ATC. Interestingly, the miR-200 family is an important regulator of the EMT process by regulating ZEB1 and ZEB2 protein levels. Downregulation of miR-200 in ATC would potentiate the TGFβ-mediated EMT switch and enhance aggressiveness.

2.2. miR-30 Family

The miR-30 family of tumor suppressor miRNAs is composed of five members: miR-30a, miR-30b, miR-30c, miR-30d, and miR-30e. Downregulation of the miR-30 family is observed in several types of cancer such as breast, bladder, and colon [26, 27]. Moreover, decreased expression of miR-30 is observed in metastasis compared to the primary tumor [28], suggesting a role in aggressive disease. In ATC, miR-30 expression is also reduced in tumor samples [20, 29]. Indeed, modulation of miR-30 levels in ATC cells has a great impact in cancer cell biology. Importantly, miR-30d ectopic expression in an ATC cell line reduced monolayer cell growth and impaired anchorage-independent cell growth [30].

Downregulation of miR-30 derepresses the expression of EZH2, an important component of the polycomb repressive complex 2 (PRC2) that regulates chromatin condensation and gene expression. EZH2 is the enzymatic subunit of histone methyltransferase that trimethylates histone H3 lysine 27. EZH2 is overexpressed in ATC and enhances cell proliferation, migration, and invasion, while repressing the expression of thyroid transcription factor PAX8 [31]. Another important cellular process regulated by the miR-30 family is autophagy through targeting the key autophagy-promoting protein, Beclin1 (gene BECN1). In ATC, miR-30d restoration sensitizes cancer cells to cisplatin treatment by repressing Beclin1, which participates in the early stages of autophagosome formation [32]. An miR-30d mimic enhanced the apoptotic effects of cisplatin as shown by increased cleaved caspase-3 and PARP levels and annexin V staining [33]. Moreover, cisplatin treatment in a xenograft model also showed shrinkage of ATC tumor derived from miR-30 overexpressing cells. The blockage of autophagy using specific inhibitors exerts similar effects to the reintroduction of miR-30 into ATC cells, indicating that the autophagy process is important for ATC cells' resistance to chemotherapy.

2.3. let-7 Family

Family genes of let-7 are located on different chromosomes and are abundantly expressed in a normal thyroid gland (let-7a, let-7b, let-7c, let-7d, let-7e, let-7f, and let-7g) [34]. Deregulation of let-7 is observed in several types of cancer, and its tumor suppressor effects are usually abolished by its downregulation [35]. let-7 was the first miRNA identified as having a role in cancer through validation of RAS protooncogene mRNA targeting and the association of low levels of let-7 with a poor prognosis in lung cancer [36]. Downregulation of several members of the let-7 family is observed in well-differentiated thyroid cancer (PTC and FTC) [37–39], but a marked decrease in the expression of let-7a, let-7c, let-7d, let-7f, let-7g, and let-7i is also observed in ATC [20, 21, 29].

Modulation of let-7 levels alters thyroid cancer cell biology. Ectopic expression of let-7f in a PTC cell line inhibits cell proliferation and viability, while it reduces the activation of MAPK signaling, an important marker of thyroid cancer [40]. Moreover, let-7 enhances the expression of thyroid transcription factor-1 (TTF1/NKX2-1), a key factor in maintaining the expression of iodine metabolizing genes and thyroid differentiation, usually lost in ATC. The recovery of let-7a expression in an FTC cell line changes cell morphology to an epithelial-like phenotype (flat and adherent), while it reduces cell migration by targeting FXYD5, an important regulator of cell adhesion [39]. Moreover, in aggressive lung cancer, loss of let-7 is associated with a poorer prognosis [36], and the reduction of let-7c is associated with refractoriness to chemo- and radiotherapy treatments. Indeed, the ectopic expression of let-7c in a lung cancer cell line restores the cells' response to chemo- and radiotherapy and represses the EMT process [41], indicating an important role for let-7 in tumor aggressiveness.

3. Upregulated miRNAs in ATC

Common miRNAs such as miR-146, miR-221, miR-222, and miR-17-92 are upregulated in aggressive ATC and in well-differentiated thyroid cancer, indicating that reinforced expression of these miRNAs is important in maintaining the oncogenic process.

3.1. Cluster miR-17-92

The miR-17-92 cluster is located on chromosome 13 and transcribes a polycistron that yields seven different mature miRNAs: miR-17-5p, miR-17-3p, miR-18a, miR-19a, miR-19b, miR-20a, and miR-92a. In normal thyroid follicular cells, early BRAFV600E oncogene activation induces the expression of an miR-17-92 cluster [42]. The BRAF oncogene is the most frequent genetic alteration in thyroid cancer (i.e., PTC) and is also detected in ATC, associated with poor clinical-pathological features of cancer such as extrathyroidal invasion, short time recurrence, and distant metastases [43, 44]. High levels of miR-17-92 components are expressed in ATC [45], similar to that observed in other types of cancer, such as lung, colon, pancreatic, and lymphoma [46], especially in the aggressive forms of disease [47].

The molecular modulation of endogenous levels of these miRNAs using LNA (locked nucleic acid) modification resulted in important effects in ATC cell biology. Specific blockage of miR-17-5p, miR-17-3p, and miR-19a resulted in a pronounced growth inhibition of ATC cells and apoptosis through activation of caspase-3 and caspase-9 [45]. Inhibition of the miR-17-92 cluster in ATC leads to the recovery of PTEN protein levels [45], an important negative regulator of PI3K growth signaling, which is repressed in ATC. Moreover, among several validated targets for the miR-17-92 cluster are proteins associated with tumor aggressiveness. A key target that influences tumor invasion is TIMP-3, an important inhibitor of metalloproteinase activation, targeted by miR-17-5p and miR-17-3p.

3.2. miR-146a and miR-146b

The miR-146 family, miR-146a and miR-146b, is overexpressed in ATC [18, 29, 48]. Despite sharing the same seed region, and therefore targets, miR-146a and miR-146b are transcribed by two independent genes located on chromosomes 5 and 10, respectively, and regulated by the transcription factor NFκB. The promoter region of both miRNAs contains binding sites for the NFκB complex, part of a key oncogenic signaling pathway, usually overactivated in ATC, which shows increased nuclear staining for RelA (p65), the subunit of the NFκB dimer [49]. Ectopic expression of the inhibitory protein of this signaling, IκB, decreases miR-146a and miR-146b levels in an ATC cell line [48]. Moreover, inhibition of miR-146a leads to an abrogation of anchorage-independent growth and invasion by ATC cells [48]. Interestingly, NFκB activation is observed at the invasive front of aggressive PTC showing local invasion compared to the central region of the tumor [50] and also in response to a BRAFV600E oncogene, leading to cell migration and invasion [51], and miR-146b upregulation [52]. Moreover, the introduction of miR-146b into PTC mutated cells (BRAFV600E or RET/PTC1) enhances cell invasiveness and migration [53]. Therefore, the NFκB signaling pathway and its transcriptionally activated miRNAs, miR-146a and miR-146b, play an important role in thyroid cancer aggressiveness and progression. Indeed, increased plasma circulating levels of miR-146b can be detected in papillary thyroid cancer before surgery, which also correlates with tumor aggressiveness and poor prognosis [54].

3.3. miR-221 and miR-222

miR-221/miR-222 is a cluster of miRNAs, located on chromosome X, which is deregulated in thyroid cancer. Although miR-221 and miR-222 overexpression is detected in differentiated (PTC and FTC) [17, 37] and anaplastic thyroid cancer cells [18, 29, 55], the expression of these miRNAs is associated with poor clinical-pathological features of cancer. In PTC and FTC, levels of miR-221 and miR-222 positively correlate with tumor aggressiveness, increased extrathyroidal invasion, tumor size, higher tumor node metastasis stage, and papillary thyroid cancer recurrence [18, 56–58]. Indeed, higher expression of miR-221 and miR-222 is present in metastatic, in comparison to nonmetastatic, cancers [59]. Moreover, miR-222 increased circulating plasma level is associated with the presence of the BRAF mutation and recurrent papillary thyroid cancer [54].

Ectopic expression of miR-221 in cancer cells results in a robust increase in anchorage-independent growth in soft-agar medium [37], pointing to a role for this cluster of miRNAs in the process of invasion and cell migration. Indeed, one target of the cluster is RECK, an inhibitor of metalloproteinase. Inhibition of miR-221 impairs cell migration and invasion via upregulation of RECK while it reduces metastases in a colon cancer mouse model [60]. Both miR-221 and miR-222 also influence cell proliferation, once overexpression deregulates the cell cycle, by targeting the p27kip1 (CDKN1B) protein, a key regulator of cell cycle progression [61].

4. Concluding Remarks

Currently, there is no effective therapy to blunt the lethal course of ATC, therefore prompting trials of additional and innovative therapies for ATC. Molecular targeted therapy for ATC seems to be a promising approach to retard cancer growth and increase patient survival. The molecular modulation of miRNA levels using miRNA mimics or antimiRs, allied to a novel class of highly specific inhibitors of MAPK and PI3K signaling, for instance, may enhance the ATC response to conventional treatment [62].

Systemic miRNA injection has showed promising results using lipid and other carrier molecules for treating lung and prostate cancer in animal models. Intratumoral injection or tail vein injection of a lipid-based miR-34a inhibited orthotopic prostate cancer tumor growth and metastases in immune-deficient mice [63], and lentivirus mediated miR-34a delivery to prostate cancer cells completely inhibited tumor growth. Moreover, the growth of prostate cancer bone metastases was significantly inhibited by systemically injecting miR-16 complexed with atelocollagen [64]. In lung cancer, systemic injection of a neutral lipid emulsion of miR-34a and let-7 significantly decreased in tumor burden in a mouse model of non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) [65]. Interestingly, a promising drug called miravirsen (SPC3649) is under phase II clinical trial for treating hepatic cancer. Miravirsen is a 15-nucleotide locked nucleic acid-modified antisense oligonucleotide with high affinity and specificity to miR-122, an miRNA used by HCV for hepatic cells infection [66].

Further studies in vitro and in animal models concerning the functional role of miRNAs and the impact of modulating oncomiR endogenous levels in ATC are one key to their future application as therapeutic adjuvant treatments. In particular, ATC patients would benefit from the concomitant reintroduction of tumor suppressor miRNAs miR-200 and miR-30 and the inhibition of the oncogenic miR-146, miR-221/miR-222, and miR-17-92 clusters, as these miRNAs target several deregulated processes such as cell growth, invasion, migration, and EMT.

Acknowledgments

Sao Paulo Research Foundation (FAPESP) Grants nos. 2010/51704-0, 2011/50732-2 and 2013/11019-4, a grant from the National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (CNPq), and a grant from the University of Sao Paulo, NapMiR Research Support Center, were presented to this work.

Conflict of Interests

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interests regarding the publication of this paper.

References

- 1.Howlader N, Noone A, Krapcho M, et al. Cronin K SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975–2011. Bethesda, Md, USA: National Cancer Institute; 2013. based on November 2013 SEER data submission, posted to the SEER web site, April 2014, http://seer.cancer.gov/csr/1975_2011/ [Google Scholar]

- 2.Smallridge RC, Ain KB, Asa SL, et al. American Thyroid Association guidelines for management of patients with anaplastic thyroid cancer. Thyroid. 2012;22(12):1104–1139. doi: 10.1089/thy.2012.0302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.O'Neill JP, Shaha AR. Anaplastic thyroid cancer. Oral Oncology. 2013;49(7):702–706. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2013.03.440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Patel KN, Shaha AR. Poorly differentiated and anaplastic thyroid cancer. Cancer Control. 2006;13(2):119–128. doi: 10.1177/107327480601300206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Donghi R, Longoni A, Pilotti S, Michieli P, Della Porta G, Pierotti MA. Gene p53 mutations are restricted to poorly differentiated and undifferentiated carcinomas of the thyroid gland. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 1993;91(4):1753–1760. doi: 10.1172/JCI116385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fagin JA, Matsuo K, Karmakar A, Tang SH, Koeffler HP. High prevalence of mutations of the p53 gene in poorly differentiated human thyroid carcinomas. The Journal of Clinical Investigation. 1993;91(1):179–184. doi: 10.1172/JCI116168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Landa I, Ganly I, Chan TA, et al. Frequent somatic TERT promoter mutations in thyroid cancer: higher prevalence in advanced forms of the disease. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2013;98:E1562–E1566. doi: 10.1210/jc.2013-2383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Liu X, Bishop J, Shan Y, et al. Highly prevalent TERT promoter mutations in aggressive thyroid cancers. Endocrine-Related Cancer. 2013;20(4):603–610. doi: 10.1530/ERC-13-0210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ricarte-Filho JC, Ryder M, Chitale DA, et al. Mutational profile of advanced primary and metastatic radioactive iodine-refractory thyroid cancers reveals distinct pathogenetic roles for BRAF, PIK3CA, and AKT1. Cancer Research. 2009;69(11):4885–4893. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-0727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Smallridge RC, Marlow LA, Copland JA. Anaplastic thyroid cancer: molecular pathogenesis and emerging therapies. Endocrine-Related Cancer. 2009;16(1):17–44. doi: 10.1677/ERC-08-0154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nikiforova MN, Kimura ET, Gandhi M, et al. BRAF mutations in thyroid tumors are restricted to papillary carcinomas and anaplastic or poorly differentiated carcinomas arising from papillary carcinomas. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2003;88(11):5399–5404. doi: 10.1210/jc.2003-030838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Garcia-Rostan G, Tallini G, Herrero A, D'Aquila TG, Carcangiu ML, Rimm DL. Frequent mutation and nuclear localization of β-catenin in anaplastic thyroid carcinoma. Cancer Research. 1999;59(8):1811–1815. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Knauf JA, Ma X, Smith EP, et al. Targeted expression of BRAFV600E in thyroid cells of transgenic mice results in papillary thyroid cancers that undergo dedifferentiation. Cancer Research. 2005;65(10):4238–4245. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-0047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Knauf JA, Sartor MA, Medvedovic M, et al. Progression of BRAF-induced thyroid cancer is associated with epithelial-mesenchymal transition requiring concomitant MAP kinase and TGFΒ signaling. Oncogene. 2011;30(28):3153–3162. doi: 10.1038/onc.2011.44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McFadden DG, Vernon A, Santiago PM, et al. p53 constrains progression to anaplastic thyroid carcinoma in a Braf-mutant mouse model of papillary thyroid cancer. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2014;111(16):E1600–E1609. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1404357111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Antico Arciuch VG, Russo MA, Dima M, et al. Thyrocyte-specific inactivation of p53 and Pten results in anaplastic thyroid carcinomas faithfully recapitulating human tumors. Oncotarget. 2011;2(12):1109–1126. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.He H, Jazdzewski K, Li W, et al. The role of microRNA genes in papillary thyroid carcinoma. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2005;102(52):19075–19080. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0509603102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nikiforova MN, Tseng GC, Steward D, Diorio D, Nikiforov YE. MicroRNA expression profiling of thyroid tumors: biological significance and diagnostic utility. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2008;93(5):1600–1608. doi: 10.1210/jc.2007-2696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ferraz C, Lorenz S, Wojtas B, Bornstein SR, Paschke R, Eszlinger M. Inverse correlation of miRNA and cell cycle-associated genes suggests influence of miRNA on benign thyroid nodule tumorigenesis. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2013;98(1) E8:p. E16. doi: 10.1210/jc.2012-2564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Visone R, Pallante P, Vecchione A, et al. Specific microRNAs are downregulated in human thyroid anaplastic carcinomas. Oncogene. 2007;26(54):7590–7595. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Braun J, Hoang-Vu C, Dralle H, Hüttelmaier S. Downregulation of microRNAs directs the EMT and invasive potential of anaplastic thyroid carcinomas. Oncogene. 2010;29(29):4237–4244. doi: 10.1038/onc.2010.169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chang CJ, Chao CH, Xia W, et al. p53 regulates epithelial–mesenchymal transition and stem cell properties through modulating miRNAs. Nature Cell Biology. 2011;13:317–323. doi: 10.1038/ncb2173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hermeking H. MicroRNAs in the p53 network: micromanagement of tumour suppression. Nature Reviews Cancer. 2012;12(9):613–626. doi: 10.1038/nrc3318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schiff BA, McMurphy AB, Jasser SA, et al. Epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) is overexpressed in anaplastic thyroid cancer, and the EGFR inhibitor gefitinib inhibits the growth of anaplastic thyroid cancer. Clinical Cancer Research. 2004;10(24):8594–8602. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-0690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhang Z, Liu Z, Ren W, Ye X, Zhang Y. The miR-200 family regulates the epithelial-mesenchymal transition induced by EGF/EGFR in anaplastic thyroid cancer cells. International Journal of Molecular Medicine. 2012;30(4):856–862. doi: 10.3892/ijmm.2012.1059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ichimi T, Enokida H, Okuno Y, et al. Identification of novel microRNA targets based on microRNA signatures in bladder cancer. International Journal of Cancer. 2009;125(2):345–352. doi: 10.1002/ijc.24390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ouzounova M, Vuong T, Ancey P, et al. MicroRNA miR-30 family regulates non-attachment growth of breast cancer cells. BMC Genomics. 2013;14, article 139 doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-14-139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Baffa R, Fassan M, Volinia S, et al. MicroRNA expression profiling of human metastatic cancers identifies cancer gene targets. The Journal of Pathology. 2009;219(2):214–221. doi: 10.1002/path.2586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schwertheim S, Sheu S, Worm K, Grabellus F, Schmid KW. Analysis of deregulated miRNAs is helpful to distinguish poorly differentiated thyroid carcinoma from papillary thyroid carcinoma. Hormone and Metabolic Research. 2009;41(6):475–481. doi: 10.1055/s-0029-1215593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Esposito F, Tornincasa M, Pallante P, et al. Down-regulation of the miR-25 and miR-30d contributes to the development of anaplastic thyroid carcinoma targeting the polycomb protein EZH2. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2012;97(5):E710–E718. doi: 10.1210/jc.2011-3068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Borbone E, Troncone G, Ferraro A, et al. Enhancer of zeste homolog 2 overexpression has a role in the development of anaplastic thyroid carcinomas. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2011;96(4):1029–1038. doi: 10.1210/jc.2010-1784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhu H, Wu H, Liu X, et al. Regulation of autophagy by a beclin 1-targeted microRNA, miR-30a, in cancer cells. Autophagy. 2009;5(6):816–823. doi: 10.4161/auto.9064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhang Y, Yang WQ, Zhu H, et al. Regulation of autophagy by miR-30d impacts sensitivity of anaplastic thyroid carcinoma to cisplatin. Biochemical Pharmacology. 2014;87:562–570. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2013.12.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Marini F, Luzi E, Brandi ML. MicroRNA role in thyroid cancer development. Journal of Thyroid Research. 2011;2011:12 pages. doi: 10.4061/2011/407123.407123 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fuziwara CS, Geraldo MV, kimura ET. Let-7 and cancer. In: Dahiya N, editor. MicroRNA Let-7: Role in Human Diseases and Drug Discovery. New York, NY, USA: Nova Science Publishers; 2012. pp. 109–124. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Takamizawa J, Konishi H, Yanagisawa K, et al. Reduced expression of the let-7 microRNAs in human lung cancers in association with shortened postoperative survival. Cancer Research. 2004;64(11):3753–3756. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-0637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pallante P, Visone R, Ferracin M, et al. MicroRNA deregulation in human thyroid papillary carcinomas. Endocrine-Related Cancer. 2006;13(2):497–508. doi: 10.1677/erc.1.01209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Swierniak M, Wojcicka A, Czetwertynska M, et al. In-depth characterization of the MicroRNA transcriptome in normal thyroid and papillary thyroid carcinoma. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2013;98(8):E1401–E1409. doi: 10.1210/jc.2013-1214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Colamaio M, Calì G, Sarnataro D, et al. Let-7a down-regulation plays a role in thyroid neoplasias of follicular histotype affecting cell adhesion and migration through its ability to target the FXYD5 (Dysadherin) gene. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2012;97(11):E2168–E2178. doi: 10.1210/jc.2012-1929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ricarte-Filho JCM, Fuziwara CS, Yamashita AS, Rezende E, da-Silva MJ, Kimura ET. Effects of let-7 microRNA on cell growth and differentiation of papillary thyroid cancer. Translational Oncology. 2009;2(4):236–241. doi: 10.1593/tlo.09151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cui SY, Huang JY, Chen YT, et al. Let-7c governs the acquisition of chemo- or radioresistance and epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition phenotypes in docetaxel-resistant lung adenocarcinoma. Molecular Cancer Research. 2013;11(7):699–713. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-13-0019-T. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fuziwara CS, Kimura ET. High iodine blocks a Notch/miR-19 loop activated by the BRAFV600E oncoprotein and restores the response to TGFbeta in thyroid follicular cells. Thyroid. 2013;24(3):453–462. doi: 10.1089/thy.2013.0398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Riesco-Eizaguirre G, Gutiérrez-Martínez P, García-Cabezas MA, Nistal M, Santisteban P. The oncogene BRAFV600E is associated with a high risk of recurrence and less differentiated papillary thyroid carcinoma due to the impairment of Na+/I− targeting to the membrane. Endocrine-Related Cancer. 2006;13(1):257–269. doi: 10.1677/erc.1.01119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Xing M, Westra WH, Tufano RP, et al. BRAF mutation predicts a poorer clinical prognosis for papillary thyroid cancer. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2005;90(12):6373–6379. doi: 10.1210/jc.2005-0987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Takakura S, Mitsutake N, Nakashima M, et al. Oncogenic role of miR-17-92 cluster in anaplastic thyroid cancer cells. Cancer Science. 2008;99(6):1147–1154. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2008.00800.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Volinia S, Calin GA, Liu C, et al. A microRNA expression signature of human solid tumors defines cancer gene targets. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2006;103(7):2257–2261. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0510565103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hayashita Y, Osada H, Tatematsu Y, et al. A polycistronic MicroRNA cluster, miR-17-92, is overexpressed in human lung cancers and enhances cell proliferation. Cancer Research. 2005;65(21):9628–9632. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-2352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pacifico F, Crescenzi E, Mellone S, et al. Nuclear factor-κb contributes to anaplastic thyroid carcinomas through up-regulation of miR-146a. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2010;95(3):1421–1430. doi: 10.1210/jc.2009-1128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Pacifico F, Mauro C, Barone C, et al. Oncogenic and anti-apoptotic activity of NF-κB in human thyroid carcinomas. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2004;279(52):54610–54619. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M403492200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Vasko V, Espinosa AV, Scouten W, et al. Gene expression and functional evidence of epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition in papillary thyroid carcinoma invasion. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2007;104(8):2803–2808. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0610733104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Palona I, Namba H, Mitsutake N, et al. BRAFV600E promotes invasiveness of thyroid cancer cells through nuclear factor κB activation. Endocrinology. 2006;147(12):5699–5707. doi: 10.1210/en.2006-0400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Geraldo MV, Yamashita AS, Kimura ET. MicroRNA miR-146b-5p regulates signal transduction of TGF-Β by repressing SMAD4 in thyroid cancer. Oncogene. 2012;31(15):1910–1922. doi: 10.1038/onc.2011.381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Chou C, Yang KD, Chou F, et al. Prognostic implications of miR-146b expression and its functional role in papillary thyroid carcinoma. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2013;98(2):E196–E205. doi: 10.1210/jc.2012-2666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lee JC, Zhao JT, Clifton-Bligh RJ, et al. MicroRNA-222 and microRNA-146b are tissue and circulating biomarkers of recurrent papillary thyroid cancer. Cancer. 2013;119(24):4358–4365. doi: 10.1002/cncr.28254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Mitomo S, Maesawa C, Ogasawara S, et al. Downregulation of miR-138 is associated with overexpression of human telomerase reverse transcriptase protein in human anaplastic thyroid carcinoma cell lines. Cancer Science. 2008;99(2):280–286. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2007.00666.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Chou CK, Chen RF, Chou FF, et al. MiR-146b is highly expressed in adult papillary thyroid carcinomas with high risk features including extrathyroidal invasion and the BRAFV600E mutation. Thyroid. 2010;20(5):489–494. doi: 10.1089/thy.2009.0027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wang Z, Zhang H, He L, et al. Association between the expression of four upregulated miRNAs and extrathyroidal invasion in papillary thyroid carcinoma. OncoTargets and Therapy. 2013;6:281–287. doi: 10.2147/OTT.S43014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lee JC, Zhao JT, Clifton-Bligh RJ, et al. MicroRNA-222 and MicroRNA-146b are tissue and circulating biomarkers of recurrent papillary thyroid cancer. Cancer. 2013;119(24):4358–4365. doi: 10.1002/cncr.28254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Jikuzono T, Kawamoto M, Yoshitake H, et al. The miR-221/222 cluster, miR-10b and miR-92a are highly upregulated in metastatic minimally invasive follicular thyroid carcinoma. International Journal of Oncology. 2013;42(6):1858–1868. doi: 10.3892/ijo.2013.1879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Qin J, Luo M. MicroRNA-221 promotes colorectal cancer cell invasion and metastasis by targeting RECK. FEBS letters. 2014;588(1):99–104. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2013.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Visone R, Russo L, Pallante P, et al. MicroRNAs (miR)-221 and miR-222, both overexpressed in human thyroid papillary carcinomas, regulate p27Kip1 protein levels and cell cycle. Endocrine-Related Cancer. 2007;14(3):791–798. doi: 10.1677/ERC-07-0129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Fuziwara CS, Kimura ET. Modulation of deregulated microRNAs for target therapy in thyroid cancer. In: Sarkar FH, editor. MicroRNA Targeted Cancer Therapy. 1st edition. Cham, Switzerland: Springer; 2014. pp. 219–237. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Liu C, Kelnar K, Liu B, et al. The microRNA miR-34a inhibits prostate cancer stem cells and metastasis by directly repressing CD44. Nature Medicine. 2011;17(2):211–215. doi: 10.1038/nm.2284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Takeshita F, Patrawala L, Osaki M, et al. Systemic delivery of synthetic microRNA-16 inhibits the growth of metastatic prostate tumors via downregulation of multiple cell-cycle genes. Molecular Therapy. 2010;18(1):181–187. doi: 10.1038/mt.2009.207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Trang P, Wiggins JF, Daige CL, et al. Systemic delivery of tumor suppressor microRNA mimics using a neutral lipid emulsion inhibits lung tumors in mice. Molecular Therapy. 2011;19(6):1116–1122. doi: 10.1038/mt.2011.48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Janssen HLA, Reesink HW, Lawitz EJ, et al. Treatment of HCV infection by targeting microRNA. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2013;368(18):1685–1694. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1209026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Vergoulis T, Vlachos IS, Alexiou P, et al. TarBase 6.0: capturing the exponential growth of miRNA targets with experimental support. Nucleic Acids Research. 2012;40(1):D222–D229. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr1161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Johnson SM, Grosshans H, Shingara J, et al. RAS is regulated by the let-7 microRNA family. Cell. 2005;120(5):635–647. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Wu D, Ding J, Wang L, et al. MicroRNA-125b inhibits cell migration and invasion by targeting matrix metallopeptidase 13 in bladder cancer. Oncology Letters. 2013;5(3):829–834. doi: 10.3892/ol.2013.1123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 70.Jazdzewski K, Boguslawska J, Jendrzejewski J, et al. Thyroid hormone receptor β (THRB) is a major target gene for microRNAs deregulated in papillary thyroid carcinoma (PTC) Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2011;96(3):E546–E553. doi: 10.1210/jc.2010-1594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Bhaumik D, Scott GK, Schokrpur S, Patil CK, Campisi J, Benz CC. Expression of microRNA-146 suppresses NF-κB activity with reduction of metastatic potential in breast cancer cells. Oncogene. 2008;27(42):5643–5647. doi: 10.1038/onc.2008.171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]