Abstract

The topoisomerase-IIα inhibition and antiproliferative activity of α-heterocyclic thiosemicarbazones and their corresponding copper(II) complexes have been investigated. The CuII(thiosemicarbazonato)Cl complexes were shown to catalytically inhibit topoisomerase-IIα at concentrations (0.3–7.2 μM) over an order of magnitude lower than their corresponding thiosemicarbazone ligands alone. The copper complexes were also shown to inhibit the proliferation of breast cancer cells expressing high levels of topoisomerase-IIα (SK-BR-3) at lower concentrations than cells expressing lower levels of the enzyme (MCF-7).

INTRODUCTION

For over 30 years, thiosemicarbazones (TSC) have been a focus of chemists and biologists because of their wide range of pharmacological effects; these compounds and their chemical relatives have been shown to have marked antibacterial, antiviral, antifungal, and, most intriguingly, antineoplastic activity.1 Soon after the discovery of the potency of organic thiosemicarbazones alone, it was determined that many of these molecules are often excellent chelators of transition metals, particularly Fe(II), Cu(II), and Zn(II), because of their inherent N-N-S tridentate coordination scaffold. Moreover, it was quickly shown that these metal complexes often possess potent pharmacological effects. A very rich literature exists exploring the chemistry and biology of metal-bound thiosemicarbazones, particularly CuII-thiosemicarbazonato and FeII-thiosemicarbazonato complexes.1–5

The antineoplastic activity of thiosemicarbazones is most often attributed to the ability of the compounds to inhibit mammalian ribonucleotide reductase (RR), an enzyme essential in the de novo production of deoxyribonucleotides.1 One family of thiosemicarbazones in particular (those with an α-pyridyl moiety adjacent to the N1 position) has shown significant potential as anticancer agents.6,7 Perhaps the best known member of this family, 3-aminopyridine carboxaldehyde thiosemicarbazone (3-AP), is a potent ribonucleotide reductase inhibitor that is currently in phase II clinical trials for the treatment of a number of forms of cancer, including non-small-cell lung cancer and renal carcinoma.8 Mechanistic studies of 3-AP and its analogues suggest that the biological effects of the compounds result predominantly from the intracellular chelation of Fe(II). It has been shown that not only the simple sequestration of Fe(II) but also the redox cycling properties of the resultant FeII(3-Ap) complexes are responsible for the inhibition of ribonucleotide reductase and the compound’s potent cytotoxicity.9 For example, detailed studies suggest that the enzymatic inhibition by the Fe(TSC) complex stems from the reactive oxygen species (ROS) mediated quenching of an important tyrosyl radical in the R2 subunit of RR and the more widespread deleterious effects of the intracellular production of ROS.10

The study of other α-pyridylthiosemicarbazones and their metal complexes has yielded similarly promising results.11 The ability of these compounds to inhibit critical enzymatic pathways responsible for DNA synthesis and polymerization (e.g., ribonucleotide reductase or DNA polymerase α) has been well-established. 2,3,11–14 More recently, however, other important mechanisms for the cytotoxicity of TSCs and M(TSC) complexes have been illuminated.1 For example, in elegant and thorough studies by Bernhardt, Richardson, and co-workers, di-2-pyridyl-N4-substituted thiosemicarbazones (DpT) and 2-acetylpyridine-N4-substituted thiosemicarbazones (ApT) have been shown to have potent antiproliferative effects in a variety of tumor cell lines, and convincing evidence suggests that this activity is mediated at least in part by intracellular iron chelation by the parent thiosemicarbazones and the subsequent redox cycling of the Fe(TSC) complexes to produce ROS within the cytoplasm.1,15,16 Even more relevant to the work at hand, related studies exploring the biological activity and redox properties of Cu complexes of ApT and DpT analogues have shown that these compounds, particularly monovalent Cu(TSC) species, are potent cytotoxic agents. Further, the CuI/II redox cycling of these complexes, like their FeII cousins, plays a significant role in their biological activity.15 Importantly, this work and that of others strongly support the hypothesis that it is the copper complexes rather than any dissociated ligands or cellular metabolites that are responsible for the biological effects in vitro and in vivo.13–15

Recent research into the ability of thiosemicarbazones and their metal complexes to inhibit topoisomerase IIα (Topo-IIα) has served not only to further reinforce the significant potential of metal-thiosemicarbazonato complexes in cancer research but also to expand the array of possible biochemical targets for the molecules.12–14,17–19 Topo-IIα is a well-known biomarker that is overexpressed in many forms of cancer and represents one of the most important targets for modern chemotherapeutics, with a wide variety of inhibitors (including etoposide, doxorubicin, mitoxantrone, amsacrine, and idarubicin) employed in the clinic against an array of malignancies.20,21 A small number of recent publications indicate that α-heterocyclic thiosemicarbazones and their Cu(II) complexes are capable of in vivo and in vitro inhibition of Topo-IIα at IC50 below that of the widely employed Topo-IIα poison etoposide (VP-16).12–14 Given the great potential of TSCs and their metal complexes in the development of chemotherapeutic agents and the importance of Topo-IIα in many forms of cancer, these results suggest a promising new avenue for study.12–14 Significantly, despite these exciting results, little has been reported on the role that metalation plays in the ability of TSCs to inhibit Topo-IIα. Considering the well-known complexity of the relationship between TSC metalation and biological activity, such an investigation could aid the progress of research in this field.

Herein, we report the evaluation of the Topo-IIα inhibition activity of a series of α-heterocyclic Cu(II)-thiosemicarbazonato complexes and their corresponding thiosemicarbazone ligands. Further, we examine the ability of the metal complexes to inhibit the proliferation of two breast cancer cell lines, SK-BR-3 and MCF-7, that we have shown to express high and low levels of Topo-IIα, respectively.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Synthesis and Characterization

For the study at hand, a series of α-heterocyclic-N4-substitued thiosemicarbazones (TSC) and their corresponding CuII(thiosemicarbazonato)Cl [Cu(TSC)Cl] complexes were synthesized. The thiosemicarbazone ligands were synthesized via the typical condensation route from their parent thiosemicarbazides and the appropriate ketone or aldehyde; subsequently, the Cu(TSC)Cl complexes were prepared via heating of the TSC ligands with CuCl2 (Scheme 1).7,12–14,22 The identity of both the N1-imine and N4-alkyl substituents were altered to provide a structurally systematic series of compounds (Chart 1). Because of the immense interest in their antineoplastic and antibacterial properties, a number of these complexes have been previously described in the literature.2,7 The ligands were characterized with 1HNMR, ESI-MS, and HRMS, and the Cu(TSC)Cl complexes were characterized via ESI-MS, UV-vis, and HRMS. The TSCs and Cu(TSC)Cl complexes were purified via reversed-phase HPLC and recrystallization, respectively, and prior to experimentation, the purity of all compounds was determined to be >98% by 1H NMR (ligands) and RP-HPLC (ligands and metal complexes).

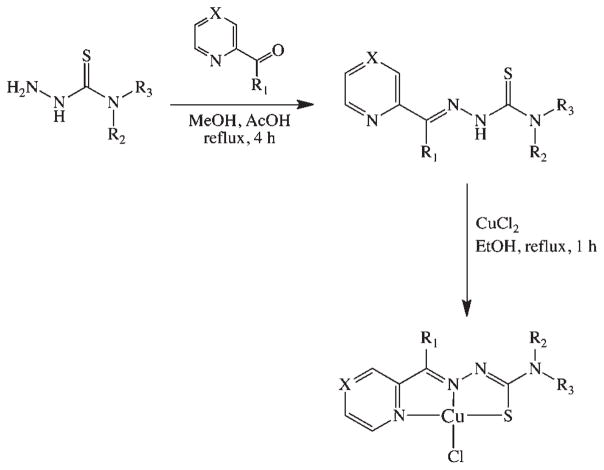

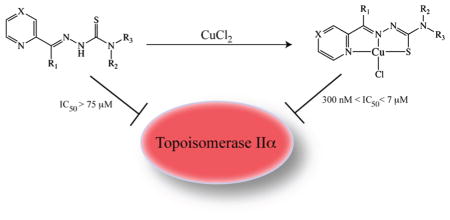

Scheme 1.

General Synthetic Route to the TSCs and Corresponding CuII(TSC)Cl Complexes

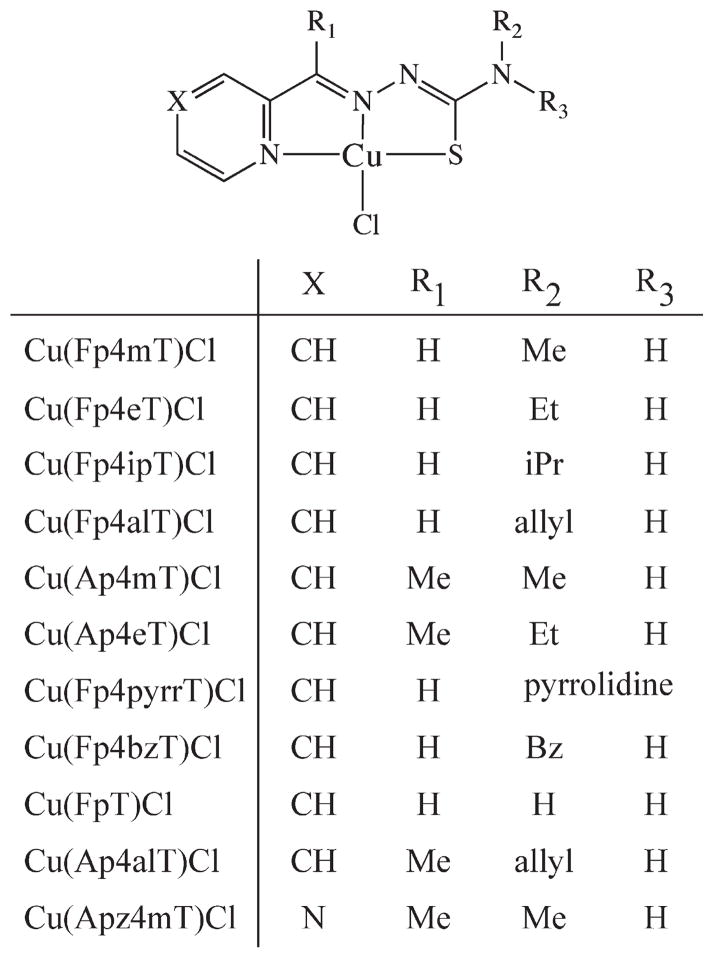

Chart 1.

Structures of the Thiosemicarbazone Ligands and Their CuII(TSC)Cl Complexesa

aWhen the ligand is discussed alone in the text, an “H” is placed before the name (e.g., HFp4mT).

Topoisomerase IIα Inhibition

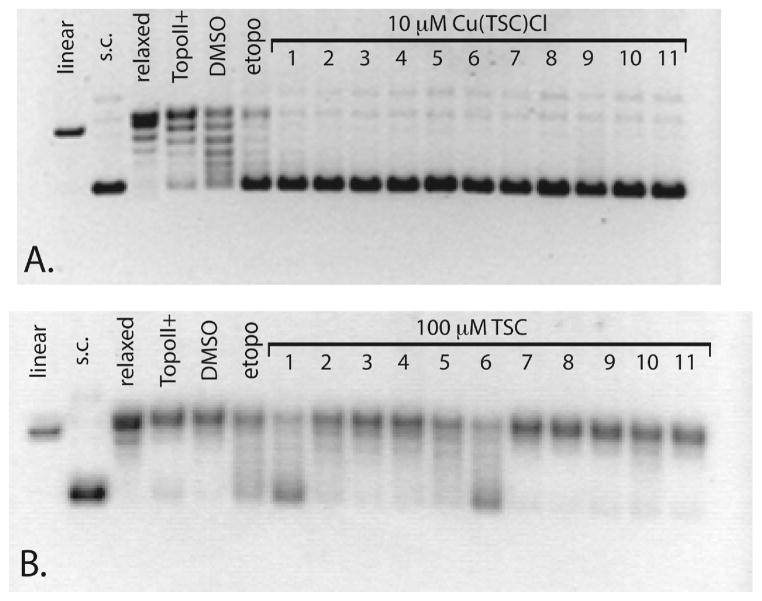

Agarose gel electrophoresis experiments were performed to assay the Topo-IIα inhibition activity of the Cu(TSC)Cl complexes and their corresponding ligands. Importantly, a commercially available Topo-IIα drug screening kit (TopoGen, Port Orange, FL) was employed for these assays, providing a significant improvement in gel clarity over previously published work using Topo-IIα isolated from cultured L1210 cells.12–14 In the present experiments, a supercoiled pHOT DNA substrate was incubated for 30 min at 37 °C with Topo-IIα in the presence of various concentrations of the agent of interest, and the resultant reaction solutions were electrophoresed on a 1% agarose gel to separate the possible products: supercoiled DNA, linear DNA, and relaxed DNA. The presence of each type of DNA indicates a different behavior by the enzyme: relaxed DNA reveals that the enzyme’s isomerase activity remains intact; supercoiled DNA suggests that the enzyme’s action has been inhibited; linear DNA reveals the formation of permanent double strand breaks during the catalytic cycle. In the study, gel results clearly show that the Cu(TSC)Cl complexes are potent Topo-IIα inhibitors, with all complexes completely inhibiting the action of Topo-IIα at 10 μM (Figure 1A). In contrast, almost all of the TSC ligands alone (Figure 1B) fail to significantly inhibit the enzyme at 100 μM, with only HFp4mT, HFp4eT, HAp4mT, and HAp4eT displaying any degree of inhibition at that concentration. Importantly, control experiments revealed that CuCl2 alone does not inhibit the enzyme at any concentrations below 500 μM, that the addition of 5% DMSO as a drug carrier does not inhibit the enzyme, and that neither the TSCs nor the Cu(TSC)Cl complexes alter the migration of the DNA below 500 μM. Subsequent experiments elucidated IC50 ranging from 300 nM to 7 μM for the Cu(TSC)Cl complexes, far below the corresponding values for the TSCs alone, which are all greater than 75 μM and in all but four cases exceed 100 μM (Chart 2). Easily the most pronounced feature of these assays was the marked difference in Topo-IIα inhibition activity of the Cu(TSC)Cl complexes compared to the TSCs alone, though the causal mechanism of this disparity remains unclear (vide supra). Importantly, a similar discrepancy in the Topo-IIα inhibitory activity of metalated vs free thiosemicarbazones has been reported for 1,2-naphthoquinone thiosemicarbazone and its CuII, PdII, and NiII complexes.23 In this case, the metallo-TSC complexes effectively inhibited Topo-IIα while the ligands alone did not; however, no IC50 values were presented in this work to quantitate the effect.

Figure 1.

Agarose gel assay for Topo-IIα inhibition by Cu(TSC)Cl complexes and TSC ligands alone. In the Cu(TSC)Cl gel (A), 1 mM etoposide was employed as a positive control, and lanes 1–11 denote the reaction of Topo-IIα with supercoiled (sc) DNA in the presence of 10 μM Cu(Fp4mT)Cl, Cu(Fp4eT)Cl, Cu(Fp4ipT)Cl, Cu(Fp4alT)Cl, Cu(Ap4mT)Cl, Cu(Ap4eT)Cl, Cu(Fp4pyrrT)Cl, Cu(Fp4bzT)Cl, Cu- (FpT)Cl, Cu(Ap4alT)Cl, and Cu(Apz4mT)Cl. In the TSC gel (B), 100 μM etoposide was employed as a positive control, and lanes 1–11 denote the reaction of Topo-IIα with supercoiled DNA in the presence of 100 μM HFp4mT, HFp4eT, HFp4ipT, HFp4alT, HAp4mT, HAp4-eT, HFp4pyrrT, HFp4bzT, HFpT, HAp4alT, and HApz4mT.

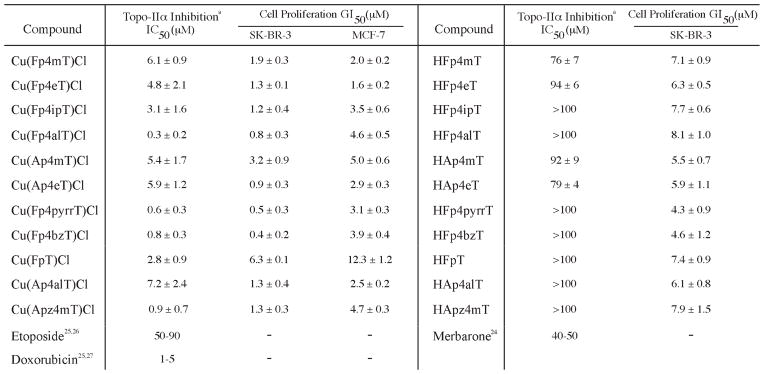

Chart 2.

Topo-IIα Inhibition Activity (IC50) and Antiproliferative Activity (GI50) of the TSCs and CuII(TSC)Cl Complexesb

aThe Topo-IIα inhibition IC50 for etoposide, merbarone, and doxorubicin vary somewhat in the literature; in this chart, a range of concentrations and representative publications are presented. bTopo-IIα inhibition IC50 values were determined via the described agarose gel supercoiled DNA relaxation assay employing a range of drug concentrations from 500 μM to 10 nM. Cell proliferation GI50 values were determined via MTT assay with drug concentrations ranging from 500 μM to 10 nM. All experiments were performed in triplicate, and all values are shown with (1 SD.

Little structure-activity relationship for Topo-IIα inhibition could be discerned for the Cu(TSC)Cl complexes or the TSCs alone. In the former case, the complexes bearing ligands with larger N4-allyl, N4-pyrrolidine, and N4-benzyl substituents [Cu(Fp4alT)Cl (300 ( 200 nM), Cu(Fp4pyrrT)Cl (600 ( 300 nM), and Cu(Fp4bzT)Cl (800 ( 300 nM)] generally had greater activity, though the least active complex, Cu(Ap4alT)Cl (7.2 ( 2.4 μM), also bears an N4-allyl group. Likewise, though a first glance suggests that the compounds with the lowest IC50 all bear a hydrogen rather than a methyl group in the R1 position, some of the complexes with the highest IC50 values [e.g., Cu(Fp4mT)Cl and Cu(Fp4eT)Cl] also possess a hydrogen at the R1 position. Among the TSCs alone, the four compounds with IC50 under 100 μM (HFp4mT, HFp4eT, HAp4mT, and HAp4eT) bear relatively small N4-substituents. However, the IC50 values of two other N4-methyl and N4-hydrogen-bearing TSCs, HApz4mT and HFpT, were both >100 μM. Clearly, the range of structures will have to be widened before a straightforward structure-activity relationship for these compounds becomes evident.

Notably, the IC50 values for the Cu(TSC)Cl complexes are comparable to those of the well-characterized Topo-IIα inhibitor doxorubicin (1–5 μM) and lie well below those of the Topo-IIα inhibitors merbarone (40–50 μM) and etoposide (50–90 μM).24–27 Further, these values generally agree with the in vitro IC50 and the in vivo concentrations at which Topo-IIα inhibition was observed in the studies of Miller et al.12–14 Similarly, the in vitro Topo-IIα IC50 values for the TSCs generally conform to those found for α-heterocyclic TSCs in Miller’s study of acetylpyridyl-N4-substituted thiosemicarbazones and the recently published work of Huang and co-workers.13,17 Further still, a recent study with di-2-pyridylketone-4,4-dimethylthiosemicarbazone (Dp44mT) found evidence of in vivo Topo-IIα inhibition at very low concentrations (<1 μM); this finding, however, is not inconsistent with the data described herein because of the significant structural difference of Dp44mT compared to the compounds at hand and because of the in vivo nature of the experiments.19

Topoisomerase IIα Inhibition Mechanism

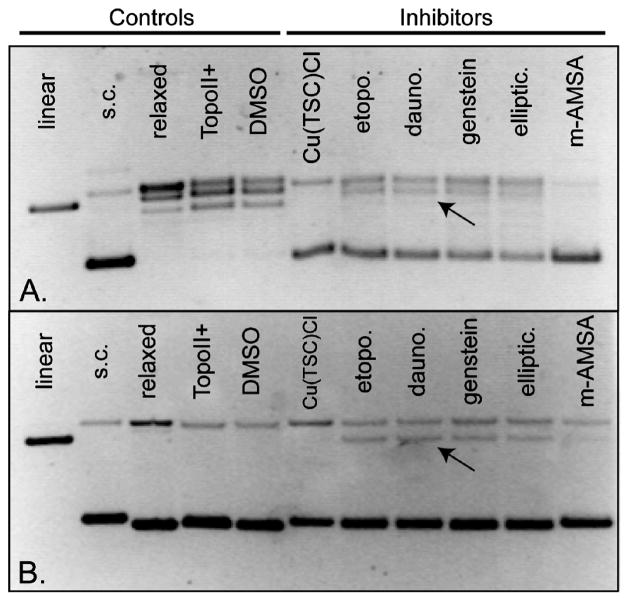

To further characterize the inhibitory action of the Cu(TSC)Cl complexes, we next determined the mechanistic class of Topo-IIα inhibitors to which the complexes belong. Two distinct classes of Topo-IIα inhibitors exist: (1) those, commonly referred to as poisons, that bind to and stabilize the DNA-Topo-IIα cleavage complex, ultimately promoting the formation of extremely toxic double strand breaks (e.g., etoposide) and (2) those, commonly referred to as catalytic inhibitors, that antagonize the ability of the enzyme to perform catalysis (e.g., merbarone).20 Further gel-based experiments aimed at the detection of double strand breaks were performed to discriminate between those two types of inhibitors. In a representative gel (Figure 2), it is clear that while the well-known Topo-IIα poisons etoposide, daunorubicin, genistein, ellipticine, and m-AMSA all produce discrete bands of linear DNA (thus indicating poison behavior), Cu(Fp4alT)Cl completely inhibits Topo-IIα without promoting the formation of linear DNA products. Similar results were observed with the other Cu(TSC)Cl complexes in the study. Thus, Cu(Fp4alT)Cl and its family of Cu(TSC)Cl complexes are catalytic inhibitors of Topo-IIα rather than poisons of the enzyme.

Figure 2.

Representative gel-based topoisomerase IIα inhibition assay illustrating the mechanism of Topo-IIα inhibition by Cu(Fp4alT)Cl. The top gel (A) was poststained with 5 μg/mL ethidium bromide in 1× TAE buffer, while the bottom gel (B) was electrophoresed with 5 μg/mL ethidium bromide within the gel. High concentrations of enzyme (4 units) and inhibitors (500 μM) were used to maximize the intensity of linear DNA bands (where present). Arrows mark representative linear DNA bands.

While it is clear that the Cu(TSC)Cl complexes at hand are catalytic inhibitors of Topo-IIα, a number of different mechanisms for this type of antagonist have been identified. Thus, the precise molecular mechanism of inhibition by the Cu(TSC)Cl complexes remains unknown. It has been well-established that the redox cycling of Fe(thiosemicarbazonato) complexes plays a significant role in their ribonucleotide reductase inhibition and cytotoxicity.1 And indeed, similar results have recently been published for Cu(thiosemicarbazonato) complexes;15 however, we believe that it is unlikely that the metal-mediated production of ROS plays a role in the observed Topo-IIα inhibition. The production of ROS would almost certainly result in the formation of single and double strand breaks in the DNA during the Topo-IIα incubation experiments, and no significant single- or double-strand break products were observed in the resultant gels. Further experimentation is currently underway to confirm this hypothesis.

A more likely mechanistic explanation lies perhaps in a convincing recent study by Huang et al. in which the authors propose that an α-heterocyclic-N4-substituted thiosemicarbazone in their study (2-quinoneline carboxaldehyde-4,4-dimethyl thiosemicarbazone) inhibits Topo-IIα by binding to the ATP hydrolysis domain of Topo-IIα and thus interfering with the ATP hydrolysis of the enzyme.17 Further, molecular docking experiments performed in the above investigation show the thiosemicarbazone in question bound to the ATPase binding site in a planar conformation with the heterocylic nitrogen, imine nitrogen, and sulfur forming a meridinal tridentate coordination environment.17 On the basis of our experimental observations and this modeled conformation of the thiosemicarbazone at the ATPase binding site, we believe it is possible that the Cu(TSC)Cl complexes in this study inhibit Topo-IIα via a similar ATP binding site-based mechanism. Interestingly, the binding of the Cu(TSC)Cl complex to the ATPase domain in a manner similar to that described in the Huang, et al. study may also present an explanation for the disparity between the inhibitory effects of the metal complexes and ligands alone. The planar molecular geometry strongly favored by the d9 Cu(II) center forces the thiosemicarbazone ligand to adopt a more rigidly planar structure than the unmetalated TSC would assume; if a planar conformation is the biologically active conformation, as is suggested by Huang and co-workers, then the Cu(TSC)Cl complexes would bind to the inhibition site more strongly than the ligands alone. Biochemical and structural investigations into the precise mechanism of Topo-IIα inhibition are currently underway to test this hypothesis; hopefully, these will also illuminate the cause of the discrepancy between TSC and Cu(TSC)Cl Topo-IIα inhibition activity.

Antiproliferative Activity of the TSCs and Cu(TSC)Cl Complexes

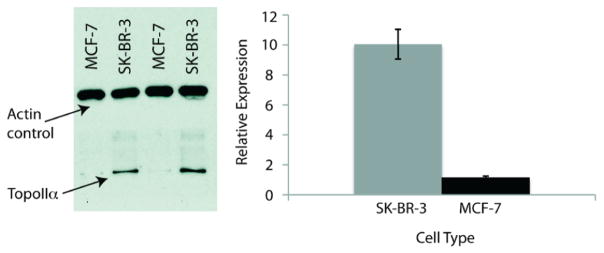

While Topo-IIα expression is often associated with malignancy, particularly strong links exist between Topo-IIα levels and breast cancer. Topo-IIα expression levels in breast cancer have been found to provide accurate and clinically helpful information on the number of cycling cancer cells, the likelihood of treatment response, the potential for remission after chemotherapy, and the possibility of disease-related death.28 Because of these well-established links, we endeavored to assay the antiproliferative effects of the Cu(TSC)Cl complexes and their parent ligands in two breast cancer cells lines, SK-BR-3 and MCF-7, that express high and low levels of Topo-IIα, respectively. To confirm the relative expression levels of Topo-IIα in SK-BR-3 and MCF-7, Western blots were performed, and it was determined that SK-BR-3 cells express approximately 10-fold more Topo-IIα than their MCF-7 counterparts (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Western blot (left) of relative Topo-IIα expression in SK-BR-3 and MCF-7 cells. Quantiation (right) was normalized using actin loading control. Error bars are (1 standard deviation and are the result of six independent experiments.

Subsequently, MTT assays were performed using 24 h drug incubations. Experiments with the Cu(TSC)Cl complexes revealed that all of the complexes are active antiproliferative agents, with GI50 of <1 to 6 μM with SK-BR-3 cells and 2 to 12 μM with MCF-7 cells (Chart 2). These values are in general agreement with those previously reported for Cu(TSC)Cl complexes and human cancer cells.12–14,29 Again, few structure-activity relationships are evident. However, two trends suggest that Topo- IIα inhibition may play a role in the antiproliferative effects of these complexes. First, in the SK-BR-3 cells, the GI50 indicate a positive correlation with the Topo-IIα inhibition IC50; that is, the Cu(TSC)Cl complexes that are more potent Topo-IIα inhibitors are also generally more active with respect to antiproliferation. Second, the GI50 for the complexes are typically lower in the Topo-IIα overexpressing SK-BR-3 cells than in the MCF-7 cells. Further, in SK-BR-3 cells, the GI50 of the Cu- (TSC)Cl complexes are lower than those of their corresponding TSC ligands alone (4–9 μM). Differences in cellular uptake and the possibility of intracellular metal chelation make quantitative comparisons between the activity of metal complexes and ligands somewhat suspect, but these data nevertheless suggest a role for Topo-IIα inhibition in the complex antiproliferative effects of these metal compounds.

Over a decade ago, a well-designed study by Miller et al. on the cytotoxicity of copper complexes of α-pyridylthiosemicarbazones proposed a variety of mechanisms for the antiproliferative effects of the compounds, including the inhibition of ribonucleotide reductase, purine biosynthesis, and DNA polymerase α.13 More recently, the important role of redox chemistry in the antiproliferative effects of mono- and divalent Cu-thiosemicarbazonato complexes has come to light.15 In this work, we have investigated yet another possible mechanism for the cytotoxicity of these compounds. The mild nature of the trends correlating IC50 and GI50 in SK-BR-3 cells and the relatively low GI50 of the complexes in the MCF-7 cells illustrate that Topo-IIα inhibition is clearly not the whole story. Yet taken together, the trends in the data described herein and the previous research of others into the Topo-IIα inhibitory activity of monovalent Cu(TSC) complexes suggest that Topo-IIα inhibition by Cu(TSC) complexes contributes to their antiproliferative activity.

CONCLUSIONS

We have synthesized a series of α-heterocyclic thiosemicarbazones and their corresponding copper(II) complexes and evaluated their in vitro Topo-IIα inhibition and antiproliferative activity in SK-BR-3 and MCF-7 breast cancer cells. Importantly, the Cu(TSC)Cl complexes are more potent Topo-IIα inhibitors than the thiosemicarbazone ligands alone, with IC50 for the complexes in most cases lower by well over an order of magnitude. Gel electrophoresis experiments revealed that the Cu(TSC)Cl complexes are catalytic inhibitors, rather than poisons, of Topo-IIα, though a molecular mechanism remains elusive. Finally, antiproliferation experiments with breast cancer cell lines expressing high and low levels of Topo-IIα (SK-BR-3 and MCF-7, respectively) revealed micromolar GI50 and suggest a role for Topo-IIα inhibition in the complex antiproliferative effects of Cu(TSC)Cl compounds. Further in vivo and in vitro mechanistic experiments are underway, as well as efforts to develop 64Cu-based positron emission tomography radiotracers for the noninvasive delineation of Topo-IIα expression in vivo. It is hoped that the investigation described herein will contribute to the development of more potent and effective Topo-IIα inhibitors and an enhanced understanding of the role of metalation in the biological activity of thiosemicarbazones.

EXPERIMENTAL SECTION

General Remarks

All chemicals, unless otherwise noted, were acquired from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO) and were used as received without further purification. All water employed was ultra-pure (>18.2 MΩcm−1 at 25 °C, Milli-Q, Millipore, Billerica, MA). All DMSO was of molecular biology grade (>99.9%; Sigma, D8418), and all other solvents were of the highest grade commercially available. All MTT assay kit materials were purchased from ATCC (Manassas, VA). All Topo-IIα Western blot and inhibition assay materials were purchased from TopoGEN, Inc. (Port Orange, FL). All instruments were calibrated and maintained in accordance with standard quality-control procedures. UV-vis measurements were taken on a Cary 100 Bio UV-vis spectrophotometer. NMR spectroscopy was performed on a Bruker 500 MHz NMR with Topsin 2.1 software for spectrum analysis. HPLC was performed using a Shimadzu HPLC equipped with a C-18 reversed-phase column (Phenomenex Luna analytical 4.6 mm × 250 mm or SemiPrep 21.2 mm × 100 mm, 5 μm, 1.0 or 6.0 mL/min), 2 LC-10AT pumps, and a SPD-M10AVP photodiode array detector. Data analysis was performed using Microsoft Excel, version 12.2.3, and OriginPro, version 8.1. All compounds employed were >98% pure, as purified via preparative reversed phase HPLC or recrystallization and as determined by 1H NMR and analytical RP-HPLC. Thiosemicarbazide precursors were synthesized according to previously reported protocols.7

General Synthetic Procedure for the Synthesis of Thiosemicarbazones

The general protocol of Klayman et al. was followed for the synthesis of all thiosemicarbazones.7 The relevant thiosemicarabazide (4.75 mmol) and ketone or aldehyde (4.75 mmol) were combined in methanol (9 mL) with acetic acid (1–2 drops). The mixture was refluxed for 4 h, during which a white or off-white precipitate appeared. After 4 h, the mixture was allowed to cool to room temperature, and water (40 mL) was added to further aid precipitation. The mixture was subsequently filtered, washed with cold water, and dried in vacuo. Ligands were further purified via semipreparative RPHPLC with a gradient of 0:100 MeCN/H2O (both with 0.1% TFA) to 100:0 MeCN/H2O over 15 min. ESI-MS, HRMS, and 1H NMR data were collected for all ligands.

General Synthetic Procedure for the Synthesis of Cu(II)-(thiosemicarbazonato)Cl Complexes

The general protocols published by West et al. were employed for the metalation of the thiosemicarbazone ligands.30 Thiosemicarbazone (0.5 mmol) and CuCl2 (0.48 mmol) were combined in EtOH (10 mL). The resultant mixture was stirred and refluxed for 1 h, during which a bright green precipitate appeared. After 1 h, the mixture was allowed to cool to room temperature. The mixture was then filtered, and the bright green product was washed with EtOH and Et2O and dried in vacuo. All metal complexes were subsequently purified by recrystallization from EtOH. HRMS and analytical HPLC [gradient of 0:100 MeCN/H2O(both with 0.1% TFA) to 100:0 MeCN/H2O over 15 min] were performed for all metal complexes.

Characterization Data

(E)-N-Methyl-2-(pyridin-2-ylmethylene) hydrazinecarbothioamide (HFp4mT)

Yield: 4.61 mmol (97%). 1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6), δ, ppm: 11.69 (s, 1H), 8.66 (s, 1H), 8.55 (d, 1H), 8.25 (d, 1H), 8.08 (s, 1H), 7.86 (dd, 1H), 7.38 (dd, 1H), 3.03 (s, 3H). ESI-MS: 192.9 [M − H]−. HRMS found (calculated, [M + H]+): 195.0713 (195.0704). HPLC tR = 6.9min.

(E)-N-Ethyl-2-(pyridin-2-ylmethylene)hydrazinecarbothioamide (HFp4eT)

Yield: 4.70 mmol (99%). 1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6), δ, ppm: 11.64 (s, 1H), 8.71 (s, 1H), 8.56 (d, 1H), 8.27 (d, 1H), 8.09 (s, 1H), 7.86 (dd, 1H), 7.38 (dd, 1H), 3.61 (q, 2H), 1.17 (t, 3H). ESI-MS: 207.0 [M − H]−, 231 [M + Na]+. HRMS found (calculated, [M + H]+): 209.0866 (209.0861). HPLC tR = 8.1 min.

(E)-N-Isopropyl-2-(pyridin-2-ylmethylene)hydrazinecarbothioamide (HFp4ipT)

Yield: 4.42 mmol (93%). 1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6), δ, ppm: 11.61 (s, 1H), 8.56 (s, 1H), 8.25 (d, 1H), 8.17 (d, 1H), 8.10 (1, 1H), 7.84 (dd, 1H), 7.38 (dd, 1H), 4.55 (m, 1H), 1.24 (d, 6H). ESI-MS: 221.1 [M − H]−, 245 [M + Na]+. HRMS found (calculated, [M + H]+): 223.1012 (223.1017). HPLC tR = 9.3 min.

(E)-N-Allyl-2-(pyridin-2-ylmethylene)hydrazinecarbothioamide (HFp4alT)

Yield: 4.65 mmol (98%). 1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6), δ, ppm: 11.39 (s, 1H), 8.82 (s, 1H), 8.59 (d, 1H), 8.42 (d, 1H), 8.10 (s, 1H), 7.84 (dd, 1H), 7.38 (dd, 1H), 5.91 (m, 1H), 5.15 (m, 2H), 4.26 (dd, 2H). ESI-MS: 219.2 [M − H]−. HRMS found (calculated, [M + H]+): 221.0878 (221.0861). HPLC tR = 8.9 min.

(E)-N-Methyl-2-(1-(pyridin-2-yl)ethylidene)hydrazinecarbothioamide (HAp4mT)

Yield: 3.9 mmol (82%). 1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6), δ, ppm: 10.34 (s, 1H), 8.63 (s, 1H), 8.57 (d, 1H), 8.42 (d, 1H), 7.83 (dd, 1H), 7.38 (dd, 1H), 3.06 (s, 3H), 2.36 (s, 3H). ESI-MS: 209.2 [M + H]+. HRMS found (calculated, [M + H]+): 209.0851 (209.0861). HPLC tR = 8.3 min.

(E)-N-Ethyl-2-(1-(pyridin-2-yl)ethylidene)hydrazinecarbothioamide (HAp4eT)

Yield: 4.1 mmol (86%). 1HNMR (500MHz, DMSOd6), δ, ppm: 10.25 (s, 1H), 8.67 (s, 1H), 8.58 (d, 1H), 8.41 (d, 1H), 7.81 (dd, 1H), 7.40 (dd, 1H), 3.66 (q, 2H), 2.36 (s, 3H), 1.16 (t, 3H). ESI-MS: 221.9 [M − H]−, 223.1 [M + H]+. HRMS found (calculated, [M + H]+): 223.1021 (223.1017). HPLC tR = 9.2min.

(E)-N′-(Pyridin-2-ylmethylene)pyrrolidine-1-carbothiohydrazide (HFp4pyrrT)

Yield: 4.2 mmol (88%). 1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6), δ, ppm: 11.01 (s, 1H), 8.34 (d, 1H), 7.83 (s, 1H), 7.64 (m, 2H), 7.12 (m, 1H), 1.8–1.6 (m, 10H). ESI-MS: 233.1 [M − H]−, 235.2 [M + H]+. HRMS found (calculated, [M + H]+): 235.1026 (235.1017). HPLC tR = 10.2 min.

(E)-N-Benzyl-2-(pyridin-2-ylmethylene)hydrazinecarbothioamide (HFp4bzT)

Yield: 4.7 mmol (99%). 1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6), δ, ppm: 11.82 (s, 1H), 9.25 (m, 1H), 8.57 (d, 1H), 8.30 (d, 2H), 8.13 (s, 1H), 7.83 (s, 1H), 7.40–7.25 (m, 6H), 4.87 (s, 2H). ESI-MS: 269.2 [M-H]−, 271.3 [M+H]+. HRMS found (calculated, [M+H]+): 271.1008 (271.1017). HPLC tR = 11.3 min.

(E)-2-(Pyridin-2-ylmethylene)hydrazinecarbothioamide (HFpT)

Yield: 4.6 mmol (96%). 1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6), δ, ppm: 11.62 (s, 1H), 8.56 (d, 1H), 8.34 (s, 1H), 8.26 (d, 1H), 8.16 (s, 1H), 8.08 (s, 1H), 7.83 (dd, 1H), 7.38 (dd, 1H). ESI-MS: 178.9 [MH]−. HRMS found (calculated, [M + H]+): 181.0559 (181.0548) HPLC tR = 8.2 min.

(E)-N-Allyl-2-(1-(pyridin-2-yl)ethylidene)hydrazinecarbothioamide (HAp4alT)

Yield: 4.55 mmol (96%). 1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6), δ, ppm: 10.38 (s, 1H), 8.84 (s, 1H), 8.58 (d, 1H), 8.41 (d, 1H), 7.83 (dd, 1H), 7.40 (dd, 1H), 5.93 (m, 1H), 5.18 (m, 2H), 4.26 (dd, 2H), 2.36 (s, 3H). ESI-MS: 233.0 [M − H]−, 235.0 [M + H]+. HRMS found (calculated, [M+ H]+): 235.1010 (235.1017). HPLC tR = 10.3min.

(E)-N-Methyl-2-(1-(pyrazin-2-yl)ethylidene)hydrazinecarbothioamide (HApz4mT)

Yield: 3.97 mmol (83%). 1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6), δ, ppm: 10.54 (s, 1H), 9.67 (s, 1H), 8.78 (s, 1H), 8.60 (s, 2H), 3.05 (s, 3H), 2.51 (s, 3H). ESI-MS: 210.0 [M + H]+. HRMS found (calculated, [M + H]+): 210.0825 (210.0813). HPLC tR = 8.0 min.

2-Formylpyridine-N4-methylthiosemicarbazonatochlorocopper( II) [Cu(Fp4mT)Cl]

Yield: 0.46 mmol (96%). HPLC tR = 6.3 min. ESI-MS: 294.2, 296.3 [M + H]+, 257.9 [M − Cl]+. HRMS found (calculated, [M−Cl]+): 258.0007 (258.0000). UV-vis (PBS, pH 7.4): 221 (λmax), 295, 328, 385 (ε385 = 11 800 mol−1 L−3 cm−1).

2-Formylpyridine-N4-ethylthiosemicarbazonatochlorocopper( II) [Cu(Fp4eT)Cl]

Yield: 0.45 mmol (94%). HPLC tR = 7.8 min. ESI-MS: 308.1, 310.1 [M + H]+, 271.8 [M − Cl]+. HRMS found (calculated, [M−Cl]+): 272.0169 (272.0157). UV-vis (PBS, pH 7.4): 220 (λmax), 295, 335, 389 (ε389 = 12 200mol−1 L−3 cm−1).

2-Formylpyridine-N4-isopropylthiosemicarbazonatochlorocopper( II) [Cu(Fp4ipT)Cl]

Yield: 0.47 mmol (98%). HPLC tR = 8.4 min. ESI-MS: 322.4, 324.3 [M + H]+, 286.2 [M − Cl]+. HRMS found (calculated, [M − Cl]+): 286.0308 (286.0313). UV-vis (PBS, pH 7.4): 219 (λmax), 296, 338, 395 (ε395 = 11 800 mol−1 L−3 cm−1).

2-Formylpyridine-N4-allylthiosemicarbazonatochlorocopper (II) [Cu(Fp4alT)Cl]

Yield: 0.40mmol (83%). HPLC tR =8.2min.ESI-MS: 319.7, 321.9 [M+ H]+, 284.2 [M−Cl]+. HRMS found (calculated, [M − Cl] +): 284.0166 (284.0157). UV-vis (PBS, pH 7.4): 222 (λmax), 295, 337, 393 (ε393 = 12100mol−1 L−3 cm−1).

2-Acetylpyridine-N4-methylthiosemicarbazonatochlorocopper( II) [Cu(Ap4mT)Cl]

Yield: 0.41mmol (85%). HPLC tR = 8.5 min. ESI-MS: 308.1, 310.4 [M+H]+, 272.1 [M − Cl]+. HRMS found (calculated, [M−Cl]+): 272.0153 (272.0157). UV-vis (PBS, pH7.4): 220 (λmax), 295, 331 (sh), 389 (ε389 = 11900 mol−1 L−3 cm−1).

2-Acetylpyridine-N4-ethylthiosemicarbazonatochlorocopper (II) Cu(Ap4eT)Cl]

Yield: 0.35 mmol (73%). HPLC tR = 9.1min. ESI-MS: 286.0 [M − Cl]+. HRMS found (calculated, [M − Cl]+): 286.0320 (286.0313). UV-vis (PBS, pH 7.4): 220 (λmax), 296, 337 (sh), 389 (ε389 = 11 200 mol−1 L−3 cm−1).

2-Formylpyridine-N4-pyrrolidinylthiosemicarbazonatochlorocopper( II) [Cu(Fp4pyrrT)Cl]

Yield: 0.42 mmol (88%). HPLC tR = 8.7 min. ESI-MS: 333.9, 335.8 [M + H]+, 297.9 [M − Cl]+. HRMS found (calculated, [M − Cl]+): 298.0299 (298.0313). UV-vis (PBS, pH 7.4): 219 (λmax), 302, 346, 399 (ε399 = 13 700 mol−1 L−3 cm−1).

2-Formylpyridine-N4-benzylthiosemicarbazonatochlorocopper( II) [Cu(Fp4bzT)Cl]

Yield: 0.46 mmol (96%). HPLC tR = 11.8 min. ESI-MS: 370.2, 372.1 [M + H]+, 333.9 [M−Cl]+. HRMS found (calculated, [M − Cl]+): 334.0324 (334.0313). UV-vis (PBS, pH 7.4): 220 (λmax), 395, 334, 396 (ε396 = 11 600mol−1 L−3 cm−1).

2-Formylpyridinethiosemicarbazonatochlorocopper(II) [Cu(FpT)Cl]

Yield: 0.43 mmol (89%). HPLC tR = 5.8min. ESI-MS: 279.8 [M + H]+, 243.7 [M−Cl]+. HRMS found (calculated, [M − Cl]+): 243.9846 (243.9844). UV-vis (PBS, pH 7.4): 221 (λmax), 285, 324, 392 (ε392 = 9100 mol−1 L−3 cm−1).

2-Acetylpyridine-N4-allylthiosemicarbazonatochlorocopper( II) [Cu(Ap4alT)Cl]

Yield: 0.47 mmol (99%). HPLC tR = 10.1 min. ESI-MS: 334.1, 336.1 [M + H]+, 297.9 [M − Cl]+. HRMS found (calculated, [M−Cl]+): 298.0307 (298.0313). UV-vis (PBS, pH 7.4): 220 (λmax), 297, 331, 398 (ε398) = 11 300 mol−1 L−3 cm−1).

2-Acetylpyrazine-N4-methylthiosemicarbazonatochlorocopper( II) [Cu(Apz4mT)Cl]

Yield: 0.47 mmol (99%). HPLC tR = 10.1 min. ESI-MS: 308.7, 310.9 [M + H]+, 273.1 [M−Cl]+. HRMS found (calculated, [M − Cl]+): 273.0112 (273.0109). UV-vis (PBS, pH 7.4): 220 (λmax), 296, 330, 391.

Topoisomerase IIα Inhibition Assays

Topoisomerase inhibition assays were performed using a eukaryotic topoisomerase IIα drug screening kit purchased from TopoGen (Port Orange, FL). All complementary materials (including various topoisomerase inhibitors) were also purchased from TopoGen, and all experiments were performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions and specifications. In a representative inhibition experiment, 14 μL of H2O, 4 μL of topoisomerase reaction buffer, 1 μL of supercoiled DNA subtrate, and 1 μL of eukaryotic topoisomerase IIα (~2 units of activity, as described by the manufacturer) were combined in a 1.7mLmicrocentrifuge tube. In experiments involving added drug, 2 μL of DMSO stock solution of compound were added, and the initial volume of water was adjusted to allow for a final reaction volume of 20 μL. The reaction mixture was vortexed gently, centrifuged briefly, and incubated at 37 °C for 30min. After 30min, 2 μL of 10% SDS was added to quench the reaction, 2 μL of proteinase K was added to digest remaining proteins, and the reaction mixture was again incubated at 37 °C for 15min. After this incubation, 2.5 μL of 10× loading dye was added to the reaction mixture, and the tube was subsequently vortexed lightly and centrifuged. The sample was then loaded onto a 1%agarose gel and electrophoresed for 5 h at 5 V/cm. Both prestained (5 μg/mL ethidium bromide in the 1% agarose gel) and poststained (incubated in a 1× TAE solution containing 5 μg/mL ethidium bromide) gels were performed in order to glean maximum information from the experiments. In the mechanism elucidation gels, higher amounts of enzyme (4 units) and higher concentrations of inhibitor (500 μM) were used in order to maximize the intensity of the linear DNA bands where present. Gels were visualized with a BioRad chemiluminescence detector, and the data were processed with Quantity One software (Bio-Rad, version 4.3.0), Un-Scan-It software (version 5.3, Silk Scientific, Orem, UT), and Origin (version 8.1). IC50 values were obtained by plotting % inhibition (as defined by the ratio of supercoiled DNA to total DNA in each lane) vs drug concentration and determining the midpoint of the resultant hysteresis curve using sigmoidal fitting in Origin. In some cases (especially with the TSC ligands alone), high background in the gel images made quantification somewhat difficult and resulted in slightly larger errors for the IC50 measurements; this is reflected in the data in Chart 2.

Cell Culture

Human breast cancer cell lines SK-BR-3 and MCF-7 were obtained from the American Tissue Culture Collection (ATCC, Manassas, VA) and maintained by weekly serial passage in a 5% CO2(g) atmosphere at 37 °C. Cells were harvested using a formulation of 0.25% trypsin and 0.53 mM EDTA in Hank’s buffered salt solution (HBSS) without calcium or magnesium. SK-BR-3 cells were grown in a 1:1 mixture of Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium: F-12 medium, supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum, 2mML-glutamine, nonessential amino acids, and 100 units/mL penicillin and streptomycin. MCF-7 cells were grown in minimum essential medium, supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum, 0.01 mg/mL bovine insulin (Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO), nonessential amino acids, 2mML-glutamine, 1mMsodiumpyruvate, 1.5 g/L sodium bicarbonate, and 100 units/mL penicillin and streptomycin.

Topoisomerase IIα Western Blots

SK-BR-3 and MCF-7 lysates were prepared using a lysis buffer of 100mMNaCl, 40mMKCl, 0.1mM EDTA, 20 mM Tris-Cl (pH 7.5), 0.1 mM PMSF, 10% glycerol, 0.2% NP-40, 0.1% Triton-X 100, and 1% SDS in conjunction with sonication. Protein concentrations were calculated using the bicinchoninic acid (BCA) protein assay kit (Pierce, Rockford, IL) using the manufacturer’s protocol. Lysates were resolved by SDS-PAGE electrophoresis and transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane. Human topoisomerase IIα was probed using a rabbit polyclonal antibody against Topo-IIα (TopoGEN, Port Orange, FL) at a 1:2500 dilution and a goat antirabbit IgG antibody conjugated to horseradish peroxidase (HRP) (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA) at a 1:3000 dilution. The α-tubulin loading control was probed using mouse monoclonal antibody (Abcam, Cambridge, MA) at a 1:5000 dilution and sheep anti-mouse IgG antibody conjugated to HRP (General Electric Healthcare Life Sciences, Piscataway, NJ) at a 1:4000 dilution. Bands were detected by incubating membranes with enhanced chemiluminescent substrate (Pierce, Rockford, IL). Detection was performed using the ECL-enhanced chemiluminescence detection system (Amersham Biosciences, Fairfield, CT) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Blots were visualized by autoradiography. Gels were scanned using Adobe Photoshop 7.0.1, and densitometric analysis was performed using Un-Scan-It software (version 5.3, Silk Scientific, Orem, UT).

Cell Proliferation Assays

Cell proliferation of SK-BR-3 and MCF-7 cells was quantified using an MTT assay kit obtained from American Tissue Culture Collection (ATCC, Manassas, VA) and performed according to the manufacturer’s specifications. To this end, SK-BR-3 (20 000 cells/well) and MCF-7 (50 000 cells/well) cells were seeded in 96-well plates (Costar 3596, Lowell, MA) overnight (18–24 h) (the number of cells/well that were seeded in each case was varied as described to compensate for cell growth rates and thus provide the same number of cells/well at the point of drug incubation). After overnight incubation, the medium was aspirated and discarded. Fresh medium mixed (via 1:20 dilution) with different drug concentrations was added to each well in 100 μL aliquots. The plates were subsequently incubated for 24 h at 37 °C/5% CO2. After 24 h, an amount of 10 μL of MTT reagent was added to each well, and the plates were further incubated at 37 °C/5% CO2 for 3 h. Cells were solubilized with the provided detergent reagent overnight (18–24 h) at room temperature. After this solubilization step, the absorbance of each well was measured using a SpectraMax M5 plate reader (Molecular Devices, New Orleans, LA). Proliferation values were normalized to 1 using the untreated, control well. All experiments were performed in triplicate. GI50 values were obtained by plotting % proliferation vs Cu(TSC)Cl (or TSC) concentration and determining the midpoint of the resultant hysteresis curve using sigmoidal fitting in Origin (version 8.1).

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Drs. Pierre Daumar, Jason Holland, Athanasios Glekas, and Darren Veach for helpful discussions.

This work was supported by an NSF NRSA postdoctoral grant for B.M.Z. (Grant 1F32CA144138-01).

ABBREVIATIONS USED

- TSC

thiosemicarbazone

- Topo-IIα

topoisomerase IIα

- RR

ribonucleotide reductase

- ROS

reactive oxygen species

- 3-AP

3-aminopyridine carboxaldehyde thiosemicarbazone

- DpT

di-2-pyridyl-N4-substituted thiosemicarbazones

- ApT

2-acetylpyridine-N4-substituted thiosemicarbazones

References

- 1.Yu Y, Kalinowski DS, Kovacevic Z, Siafakas AR, Jansson PJ, Stefani C, Lovejoy DB, Sharpe PC, Bernhardt PV, Richardson DR. Thiosemicarbazones from the old to new: iron chelators that are more than just ribonucleotide reductase inhibitors. J Med Chem. 2009;52:5271–5294. doi: 10.1021/jm900552r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.West DX, Liberta AE. Thiosemicarbazone complexes of copper(II): structural and biological studies. Coord Chem Rev. 1993;123:49–71. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Beraldo H, Gambino D. The wide pharmacological versatility of semicarbazones, thiosemicarbazones and their metal complexes. Mini-Rev Med Chem. 2004;4(1):31–39. doi: 10.2174/1389557043487484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kalinowski DS, Quach P, Richardson DR. Thiosemicarbazones: the new wave in cancer treatment. Future Med Chem. 2009;1(6):1143–1151. doi: 10.4155/fmc.09.80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tisato F, Marzano C, Porchia M, Pellei M, Santini C. Copper in diseases and treatments, and copper-based anticancer strategies. Med Res Rev. 2010;30(4):708–749. doi: 10.1002/med.20174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Easmon J, Heinisch G, Holzer W, Rosenwirth B. Novel thiosemicarbazones derived from formyl- and acyldiazines: synthesis, effects on cell proliferation, and synergism with antiviral agents. J Med Chem. 1992;35(17):3288–3296. doi: 10.1021/jm00095a027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Klayman DL, Bartosevich JF, Griffin TS, Mason CJ, Scovill JP. 2-Acetylpyridine thiosemicarbazones. 1. A new class of potential antimalarial agents. J Med Chem. 1979;22(7):855–859. doi: 10.1021/jm00193a020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ma B, Goh BC, Tan EH, Lam KC, Soo R, Leong SS, Wang LZ, Mo F, Chan AT, Zee B, Mok TA. A multicenter phase II trial of 3-aminopyridine-2-carboxaldehyde thiosemicarbazone and gemcitabine in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer with pharmacokinetic evaluation using peripheral blood mononuclear cells. Invest New Drugs. 2008;26:169–173. doi: 10.1007/s10637-007-9085-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shao J, Zhou B, Di Bilio AJ, Zhu L, Wang T, Qi C, Shih J, Yen Y. A ferrous-triapine complex mediates formation of reactive oxygen species that inactivate human ribonucleotide reductase. Mol Cancer Ther. 2006;5:586–592. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-05-0384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Thelander L, Graslund A. Mechanism of inhibition of mammalian ribonucleotide reductase by the iron chelate of 1-formylisoquinoline thiosemicarbazone. Destruction of the tyrosine free radical of the enzyme in an oxygen-requiring reaction. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1983;110:859–865. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Saryan LA, Ankel E, Krishnamurti C, Petering DH, Elford H. Comparitive cytotoxic and biochemical effects of ligands and metal-complexes of alpha-N-heterocyclic carboxaldehyde thiosemicarbazones. J Med Chem. 1979;22(10):1218–1221. doi: 10.1021/jm00196a013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Miller MC, 3rd, Bastow KF, Stineman CN, Vance JR, Song SC, West DX, Hall IH. The cytotoxicity of 2-formyl and 2-acetyl-(6-picolyl)-4N-substituted thiosemicarbazones and their copper(II) complexes. Arch Pharm. 1998;331(4):121–127. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1521-4184(199804)331:4<121::aid-ardp121>3.0.co;2-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Miller MC, 3rd, Stineman CN, Vance JR, West DX, Hall IH. The cytotoxicity of copper(II) complexes of 2-acetyl-pyridyl-4N-substituted thiosemicarbazones. Anticancer Res. 1998;18(6A):4131–4139. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Miller MC, Stineman CN, Vance JR, West DX, Hall IH. Multiple mechanisms for cytotoxicity induced by copper(II) complexes of 2-acetylpyrazine-N-substituted thiosemicarbazones. Appl Organomet Chem. 1999;13:9–19. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jansson PJ, Sharpe PC, Bernhardt PV, Richardson DR. Novel thiosemicarbazones of the ApT and DpT series and their copper complexes: identification of pronounced redox activity and characterization of their antitumor activity. J Med Chem. 2010;53:5759–5769. doi: 10.1021/jm100561b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bernhardt PV, Sharpe PC, Islam M, Lovejoy DB, Kalinowski DS, Richardson DR. Iron chelators of the dipyridyl-ketone thiosemicarbazone class: precomplexation and transmetallation effects on anticancer activity. J Med Chem. 2009;52:407–415. doi: 10.1021/jm801012z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Huang H, Chen W, Ku X, Meng L, Lin L, Wang X, Zhu C, Wang Y, Chen Z, Li M, Jiang H, Chen K, Ding J, Liu H. A series of alpha-heterocyclic carboxaldehyde thiosemicarbazones inhibit topoisomerase-II catalytic activity. J Med Chem. 2010;53:3048–3064. doi: 10.1021/jm9014394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hall IH, Miller MC, West DX. Antineoplastic and cytotoxic activity of nickel(II) complexes of thiosemicarbazones. Met-Based Drugs. 1997;4(2):89–95. doi: 10.1155/MBD.1997.89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rao VA, Klein SR, Agama KK, Toyoda E, Adachi N, Pommier Y, Shacter EB. The iron chelator Dp44mT causes DNA damage and selective inhibition of topoisomerase-II in breast cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2009;69(3):948–957. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-1437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Larsen AK, Escargueil AE, Skladanowski A. Catalytic topoisomerase II inhibitors in cancer therapy. Pharmacol Ther. 2003;99(2):167–181. doi: 10.1016/s0163-7258(03)00058-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liu LF. DNA topoisomerase poisons as antitumor drugs. Annu Rev Biochem. 1989;58:351–375. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.58.070189.002031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.West DX, Liberta AE, Rajendran KG, Hall IH. The cytotoxicity of copper(II) complexes of heterocyclic thiosemicarbazones and 2-substituted pyridine N-oxides. Anti-Cancer Drugs. 1993;4(2):241–249. doi: 10.1097/00001813-199304000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chen J, Huang Y-w, Liu G, Afrasiabi Z, Sinn E, Padhye S, Ma Y. The cytotoxicity and mechanisms of 1,2-naphthoquinone thiosemicarbazone and its metal derivatives against MCF-7 human breast cancer cells. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2004;197(1):40–48. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2004.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fortune JM, Osheroff N. Merbarone inhibits the catalytic activity of human topoisomerase II by blocking DNA cleavage. J Biol Chem. 1998;273(28):17643–17650. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.28.17643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rhee HK, Park HJ, Lee SK, Lee CO, Choo HYP. Synthesis, cytotoxicity, and DNA topoisomerase II inhibitory activity of benzofuroquinolinediones. Bioorg Med Chem. 2007;15:1651–1658. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2006.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kim JS, Rhee HK, Park HJ, Lee SK, Lee CO, Choo HYP. Synthesis of 1-/2-substituted-[1,2,3]triazolo[4,5-g]phthalazine4,9-diones and evaluation of their cytotoxicity and topoisomerase II inhibition. Bioorg Med Chem. 2008;16(8):4545–4550. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2008.02.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Suzuki K, Yahara S, Maehata K, Uyeda M. Isoaurostatin, a novel topoisomerase inhibitor produced by Thermomonospora alba. J Nat Prod. 2001;64(2):204–207. doi: 10.1021/np0004606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lynch BJ, Guinee DG, Holden JA. Human DNA topoisomerase II-alpha: a new marker of cell proliferation in invasive breast cancer. Hum Pathol. 1997;28:1180–1188. doi: 10.1016/s0046-8177(97)90256-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Easmon J, Purstinger G, Heinisch G, Roth T, Fiebig HH, Holzer W, Jager W, Jenny M, Hofmann J. Synthesis, cytotoxicity, and antitumor activity of copper(II) and iron(II) complexes of (4)N-azabicyclo[ 3.2.2]nonane thiosemicarbazones derived from acyl diazines. J Med Chem. 2001;44(13):2164–2171. doi: 10.1021/jm000979z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.West DX, Thientanavanich I, Liberta AE. Copper(II) complexes of 6-methyl-2-acetylpyridine-N(4)-substituted thiosemicarbazones. Transition Met Chem. 1995;20(3):303–308. [Google Scholar]