Abstract

Breast cancers are highly heterogeneous with different subtypes that lead to different clinical outcomes including prognosis, response to treatment and chances of recurrence and metastasis. An important task in personalized medicine is to determine the subtype for a breast cancer patient in order to provide the most effective treatment. In order to achieve this goal, integrative genomics approach has been developed recently with multiple modalities of large datasets ranging from genotypes to multiple levels of phenotypes. A major challenge in integrative genomics is how to effectively integrate multiple modalities of data to stratify the breast cancer patients. Consensus clustering algorithms have often been adopted for this purpose. However, existing consensus clustering algorithms are not suitable for the situation of integrating clustering results obtained from a mixture of numerical data and categorical data.

In this work, we present a mathematical formulation for integrative clustering of multiple-source data including both numerical and categorical data to resolve the above issue. Specifically, we formulate the problem as a novel consensus clustering method called Molecular Regularized Consensus Patient Stratification (MRCPS) based on an optimization process with regularization. Unlike the traditional consensus clustering methods, MRCPS can automatically and spontaneously cluster both numerical and categorical data with any option of similarity metrics. We apply this new method by applying it on the TCGA breast cancer datasets and evaluate using both statistical criteria and clinical relevance on predicting prognosis. The result demonstrates the superiority of this method in terms of effectiveness of aggregation and differentiating patient outcomes. Our method, while motivated by the breast cancer research, is nevertheless universal for integrative genomics studies.

Keywords: Cancer Patient Stratification, Breast Cancer Prognosis, Consensus Clustering, Integrative Genomic, Breast Cancer Subtypes

1. Introduction

Breast cancers are highly heterogeneous with many different subtypes. These subtypes confer different outcomes including different prognosis, response to treatments, and chances of recurrence and metastasis. In addition, these subtypes are often associated with different genetic mutations, gene expression profiles, molecular signatures, tissue and organ morphologies as well as different clinical phenotypes. In order to effectively treat the patients, personalized characterization of the genetic, molecular and clinical biomarkers is essential. In order to achieve this goal, integrative genomics approaches are often adopted.

Currently one of the major integrative genomics effort for cancer research is The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) project in which the genotype (SNPs, copy number variances and somatic mutations), epigenome (DNA methylation), transcriptome (mRNA and microRNA levels), proteome, morphology (histological and radiological images), and clinical records for hundreds of patients are made available for each selected cancer including breast cancer. One of the goals is to develop integrative biomarkers which can effectively stratify the patients into subtypes with clearly different clinical outcomes. However, a major challenge is how to effectively integrate multiple modalities of data.

Since the beginning of the century, gene signatures such as PAM50 [1] and the well known 70-gene signature [2] based on gene transcriptome data obtained from high throughput experiments such as microarray have been identified for subtyping breast cancer patients and prognosis prediction. However, different signatures often lead to different assignments of subtypes for the same cohort of breast cancer patients. Furthermore, subtyping based on other modalities such as microRNA, gene mutations and morphological features lead to even more discrepancies in the patient stratification [3, 4, 5, 6, 7]. Most importantly, the molecular based subtypes are often not consistent with the clinically used staging diagnosis provided by pathologists. Therefore, there is an urgent need for an effective approach for deriving a consistent framework for stratifying patients based on multiple data modalities.

Related Work

Recently, a class of unsupervised machine learning methods called consensus learning have been frequently adopted in addressing the issue of patient stratification discrepancies from multiple datasets. In traditional consensus clustering, the patients are first clustered using individual data modality. These clusters are then aggregated into a set of “consensus” clusters based on certain optimization criteria. Generally speaking, there are two main approaches to achieve the consensus solution and evaluate its quality: (1) probabilistic approach, in which given the distributions of base labelings, a maximum likelihood formulation is solved to return the consensus; (2) similarity approach, in which one can directly find the consensus clustering that agrees the most with the input base clusterings. For example, Topchy et al. [8] consider a representation of multiple clusterings as a set of new attributes characterizing the data distributions, then a mixture model (MM) offers a probabilistic model of consensus using a finite mixture of multinomial distributions in the space of base clusterings. A consensus result is found as the solution to the corresponding maximum likelihood problem using expectation maximization (EM) algorithm. Another probabilistic approach is Bayesian Consensus Ensemble, BCE [9]. Further, Lock and Dunson [10] adopt the first kind of approach, by extending the Dirich-let mixture model to accommodate data from multiple sources and apply it to multiple genomic data. In the second category, Strehl and Ghosh [11] seek a consensus clustering by maximizing the mutual information. However, currently the consensus clustering algorithms have often been applied to the studies when multiple molecular data types (e.g., genetic mutations with gene expression) are needed but they cannot be directly applicable for integrating the numerical molecular data such as gene expression levels with categorical data such as clinical staging information even though the later is highly important due to their wide clinical applications.

In this work, we present a mathematical formulation and objective of integrative clustering of multiple-source data including both numerical and categorical data to resolve the above issue. Specifically, we formulate the problem as a novel consensus clustering method called Molecular Regularized Consensus Patient Stratification (MRCPS) based on an optimization process with regularization. Unlike the traditional consensus clustering method (Cluster-based Similarity Partitioning Algorithm, CSPA [11]; HyperGraph Partitioning Algorithm, HGPA [11] and Bayesian Consensus Ensemble, BCE [9]), which can either take ”hard” or ”soft” base clusterings, this proposed method MRCPS can automatically and spontaneously cluster both numerical and categorical data with any option of similarity metrics. We apply this new method by applying it on the TCGA breast cancer datasets and evaluate using both statistical criteria and clinical relevance on predicting prognosis. The result demonstrates the superiority of this method in terms of effectiveness of aggregation and differentiating patient outcomes. Our method, while motivated by the breast cancer research, is nevertheless universal for integrative genomics studies.

The paper is organized as following: in the next section (Section 2), the problem of integratively clustering multiple types of data is mathematically formulated, followed by a brief overview of the proposed method. Then, in Section 3, we describe the details of the proposed MRCPS algorithms with proof of convergence in the Supplementary Material. Then we apply this approach to a breast cancer subtype study and provide evaluation results in Section 4 and discuss its implications in Section 5.

2. Problem Statement

2.1. Mathematical Formulation

2.1.1. Notations

Consider multiple numerical genomic measurements (each with dimension of pm) collected from N cancer samples , such that X(m) is a pm × N matrix from M data types (gene expression (mRNA) and microRNA expression), with data types (m = 1, 2, ⋯, M) from a mixture of k distributions (). Additionally we have at our disposal, various clinical attributes (histological types and tumor grades, etc.) represented by categorical vectors , all drawn from the same set of patient samples.

2.1.2. Objective

Our goal is to find a consensus partition or stratification of patients C* of from these M sets of genomic measurements and L sets of clinical attributes, such that this integration will reveal clinically and biologically relevant partition of the patient cohort based on the clustering. We propose a robust consensus clustering approach to achieve this aim.

2.2. Rationale

A natural means to cluster patient samples based on multiple types of data is to first cluster according to each individual data type and then find the consensus partition of the population from the multiple clustering results. This two-step approach carries out a series of clustering (labeled by ) from each type of molecular data, as well as each individual clinical attributes (labeled by categorical vectors ). With the clustering results from all datasets becoming available, consensus clustering methods such as CSPA [11] and BCE [9] can be used to integrate all the clusterings and provide the final consensus partition of the patients.

Current consensus clustering methods aggregate either the different clustering labels or the probability of each sample belonging to every cluster. For example, graph based methods like CSPA [11] signifies a relationship between samples in the same cluster and thus use the similarity matrix to partition the samples. The input of these methods must be ”hard” partitions of the samples and the methods can only take categorical inputs. The same drawback exists in the probabilistic algorithms, such as BCE. Given the distributions of base labelings, they solve a maximum likelihood formulation to return the consensus. The probabilistic approaches also require categorical inputs. Although there are ”soft versions” of consensus clustering, they seek consensus partition based on the probability of each sample belonging to every cluster. None of the consensus clustering methods can access to the original features of the samples. On the other hand, integrative clustering approaches such as iCluster [3, 7] can only take original features as input but not categorical labels such as clinical attributes.

2.3. Taking Advantage of the Molecular Data

The above two-step approach clusters each data source separately, followed by a post hoc integration of these separate clusterings. However, the molecular measurements, designed for detecting subtle differences between samples, are converted to a binary pairwise similarity (ie, if two samples are in the same cluster or not). This two-step method will reduce the accuracy of similarity measured by numerical molecular data and thus can miss these subtle differences in the final consensus.

Thus, instead of indirectly integrating multiple molecular data and clinical attributes, we propose to combine molecular data and clinical data automatically. Using numerical molecular expression data, we can define molecular subtypes and estimate density-based models as prescribed by the affinity of sample in the molecular features space. Next, we develop a computational method to regularize the clinical classification using the molecular density function. Finally, the patient stratification can be evaluated from statistical, clinical and biological perspectives.

A schematic diagram of this regularization method is shown in Figure 1. In the scenario where sample di and sample dj are in the same molecular subgroup and this subgroup is manifested as a relatively dense cluster in the molecular feature space, they might still be clustered in the same subgroup in the final clustering. In essence, the similarity of these two samples is not altered.

Figure 1.

Integration of molecular expression data with clinically-defined patient stratification. Although sample di and sample dj come from different clinical sub- types (I and II respectively), they come from the same, stable and dense molecular cluster, so they are desired to be combined in the consensus clustering.

This regularization also works the opposite way when sample di and sample dj are in the sparser molecular subgroup (such as the Molecular Subgroup 3 in Figure 1), but they may belong to the same clinical cluster. In reality, they might have very different etiology for cancer. The regularization will lead to the separation of the two samples in the final consensus clustering. In this way, we can take advantage of molecular features, and at the same time integrate categorical clinical attributes to derive the final clustering.

3. Methods and Materials

3.1. Dataset

The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) project aims to collect and provide genetic and genomic data for various types of cancers [12]. In one repository, mRNA and miRNA (M = 2)(microRNA) expression profiles were collected from 441 (N = 441) primary tumors of breast cancer patients. Pertinent clinical data was also available for all of these patients. The median follow-up duration is 3 years long. The mRNA and miRNA expressions were converted from RNAseq RPKM (reads per kilobase per million) and miRNAseq FPMM (fragments per million miRNA) profiles downloaded from TCGA data portal. Gene and miRNA expressions were later log-transformed, standardized and compiled into matrices. The clinical attributes (e.g. tumor grade and histological type, L = 3) were discretized into a discrete number of categories. The demographic information of patient samples is listed in Supplementary Table 1.

3.2. Molecular Regularized Consensus Patient Stratification

With notations and objective stated in the previous section, we now discuss the details of our algorithm for patient stratification based on multiple types of data. To reiterate, our method is inspired by the current state-of-the-art in consensus clustering, whereby different clusterings are aggregated to obtain one robust clustering. However, we will use numerical molecular data distance between samples to tune the clustering defined by the clinical attributes. Therefore, it is necessary to define a distance metric to represent the molecular similarity between samples.

Definition 1 - Cluster Density Function [13]

Based on the molecular features, a clustering algorithm such as Kmeans can be applied thus each sample xi (i = 1, 2, ⋯, N) is clustered in its molecular subgroup. Then, we can define a cluster density function f(i) of this sample. A classic choice of the density function is the Gaussian Kernel density function [14]:

| (1) |

where Kh is a Gaussian Kernel function with parameter h and Ni is the number of samples in the same cluster with xi in dimension p.

Definition 2 - Categorical Distance Metric

The categorical distance metric between two clinical clusters C(l) and C(l̂) can be defined as dist , where if the data points di and dj belong in the same cluster in C(l), and 0 otherwise.

Now, let us consider how to take advantage of the density function provided by the molecular data to tune the clinical clusterings. In fact, we can weight patient samples based on the reliability of the molecular communities to which they belong. The underlying intuition is that, if two patient samples di and dj are in a cluster of poor reliability in terms of molecular clustering, similarity between them can be deemed to be low and given a lower weight to leverage the high clinical similarity sij. The reliability is measured by the density functions f(i) and f(j) of the samples di and dj.

Specifically, given a set of L set of clinical partitions, C(1), ⋯, C(L), and dist(,) the symmetric difference distance metric, we wish to find an overall partition C* such that

| (2) |

Equipped with the Cluster Density Function (Definition 1) for molecular affinity and with a distance measure to compare across different clinical clusters (Definition 2), we can rewrite the above optimization in an equivalent form:

| (3) |

where S(l) is a N by N coassociation matrix. And is the entry of S(l); is the entry of S*. ωl is a weight for considering the contributions given by different base clusterings. In this case, if we assume every clinical data type scores the same to the final stratification, then ωl = 1, ∀l1 ≤ l ≤ L, changing Equation 3 as follows:

| (4) |

For samples di and dj, we have defined density estimators f(i) and f(j) respectively as the density of clusters they belong to. This density function denotes the ”molecular affinity” of the cluster sample which contains di. The larger f(i) is, the more similar the subgroup is, in molecular level. The same intuition applies to sample dj. We can weight each pair of similarity sij with the ωij = f(i) × f(j) for every di and dj. Hence, Equation 4 becomes:

| (5) |

where ωij is the molecular density function defined as:

We solve the above optimization problem as following:

| (6) |

where and S̃* = S* ○ W are the Hadamard products with ”molecular affinity matrix” W. ‖·‖F denotes the matrix Frobenius Norm.

Since S* represents the membership matrix of the final consensus clustering, we can write S* = UUT, where U = {0, 1}N × k, k is the number of clusters in the consensus. The binary membership indicator matrix U should satisfy that each row in U can only have one ’1’, , ∀i ∈ {1, ⋯, N}. Then, the above optimization problem becomes:

| (7) |

It is also required that U is diagonlizable, or UTU = D = diag(UTU) = diag(N1, N2, ⋯, Nk), where D is a diagonal matrix, {N1, N2, ⋯, Nk} are the numbers of samples in the clusters respectively, and further N1 + N2 + ⋯+Nk = N. The optimization of Equation 7 also requires to search through the indicator domain, which is exhaustive. We can relax the optimization as:

| (8) |

where . Given clinical similarity matrix and molecular density matrix W, similar to the classical Nonnegative Matrix Factorization (NMF) algorithm [15], this weighted Frobenius norm is non-increasing under the following updating rules:

| (9) |

| (10) |

The proof the convergence and derivations are provided in Supplementary Material. The detail of the MRCPS algorithm is given in Algorithm 1.

Algorithm 1.

Molecular Regularized Consensus Patient Stratification

| Data: Similarity Matrix S̃, Molecular Density Weight Matrix W, the number of clusters in final consensus k, MaxIter, precision ε | |||

| Result: Cluster indicator matrix U. | |||

| initialize Ũ(1) > 0, t = 1, Δ = +∞; | |||

| while t < MaxIter and Δ > ε do | |||

|

| |||

| end | |||

| Discretize Ũ to binary membership matrix. |

Here, the main computational cost is on calculating and in Equation 9 and Equation 10, each of which takes O(kN2) operations. So, the algorithm has complexity of #iteration × O(kN2), the same complexity with its general NMF form [16]. In real applications, the algorithm converges within about 1000 iterations.

3.3. Algorithm Usage

The proposed MRCPS method integratively clusters multiple numerical genomic data and categorical clinical attributes from the same samples and seeks a consensus clustering of the population. By this consensus clustering patient stratification, prognosis can be optimized and clinically and biologically interesting subtypes are identified. The Matlab code of the MRCPS algorithm is available here: https://github.com/chaowang1010/MorCPS.

Input: Numerical genomic measurements collected from N cancer samples and categorical vectors , drawn from the same set of patient samples. The number of final consensus clusters K.

Output: The final consensus partition C* of the N samples, where C* is a N-by-1 label vector indicating which cluster each sample belongs to.

3.4. Selection of Molecular Features based on Prior Knowledge

High-throughput sequencing measures the activities of several thousand molecules simultaneously. However, the difficulty of partitioning over these data is intrinsically caused by the existence of many redundant features that do not contribute to patient stratification. Thus, we can select a subset of relevant features from previous literatures. In the breast cancer case study, 70 prognostic genes [2] and 7 prognostic miRNAs [17] were selected. Genes from TCGA breast cancer dataset were matched with 70 genes and 28 genes were precisely matched. (Supplementary Table 2).

3.5. Choice of k and Statistical Evaluation

Traditional consensus clustering methods such as CSPA and HGPA [11] assess the effectiveness of cluster ensemble using mutual information function. In essence, the optimal consensus is expected to have the maximum mutual information with the base clusterings, meaning that it shares the most information. Here, we adopt the same statistical evaluation of using mutual information.

Let the entropy associated with u-th base clustering , where N is the number of samples and is the number of samples with label h in cluster Cu. Similarly, the entropy arising from the final clustering label is , where Nq denotes the number of samples with label q in final cluster. Therefore, the final clustering number k can be found by maximizing the following Normalized Mutual Information (NMI) with the original clusterings C:

| (11) |

where H(Cu,Cf) is the mutual information between two clusterings Cu and Cf.

Another important usage of the Normalized Mutual Information function is to determine the parameter k, the number of final clusters in consensus clustering. With different choices of k, we select the one which can maximize φ(NMI). In other words, the parameter k can be found, so that the similarity between the final cluster and all based clusterings is maximized.

4. Results

In this section, we compared the proposed MRCPS method with other consensus clustering methods that also follow the two-step model. A selected cohort of breast cancer patients in TCGA provides the necessary tested. The identified breast cancer patient subgroups were computationally tested for robustness, and then evaluated in clinical and biological contexts.

4.1. Comparative Performance of MRCPS

It is our hypothesis that MRCPS will maximize the normalized mutual information (NMI) measure in Equation 11. We included the following consensus clustering algorithms in our study namely, CSPA, HGPA and BCE for comparison purposes. For these three traditional methods, mRNA and microRNA expression profiles were clustered separately using the K-means algorithm after completing the step of feature selection. Then, we partitioned the patient population into k = 2, ⋯, 7 clusters. The result shown in Figure 2 indicated that the BCE method performed worst in terms of combining clusterings.

Figure 2.

Plotted values of NMI of MRCPS and other methods for different values of k.

Although k = 7 slightly outperformed smaller choices of k for CSPA, HGPA and the proposed MRCPS methods. It is likely that over-fitting exists with k being larger, since the observed numbers of clusters in clinical partitions are typically smaller than six. For example, the TCGA breast cancer data has four tumor grades and four disease stages. We did not provide NMI measurements beyond k = 7, since in this case study there were only 7 microRNA features. Larger k (beyond 7) is likely to provide more subtle differences between patient groups, but also will generate more over-fitting. In the case study, we have also observed that with increasing k beyond 7, the prognostic power of MRCPS decreases. In other application, users can determine the size of clusters by the sample size and separate the over-fitting from the actual improvements in clustering quality by examining not only the goodness of integrating, but also the prognostic power, which will not increase monotonically with k.

For the smaller number of clusters, MRCPS performs the best among the four methods. Additionally, the experiment also suggests that the choice of k = 4 is the best given the higher value of normalized mutual information (Equation 11).

4.2. Clinical Evaluation based on Prognosis Prediction

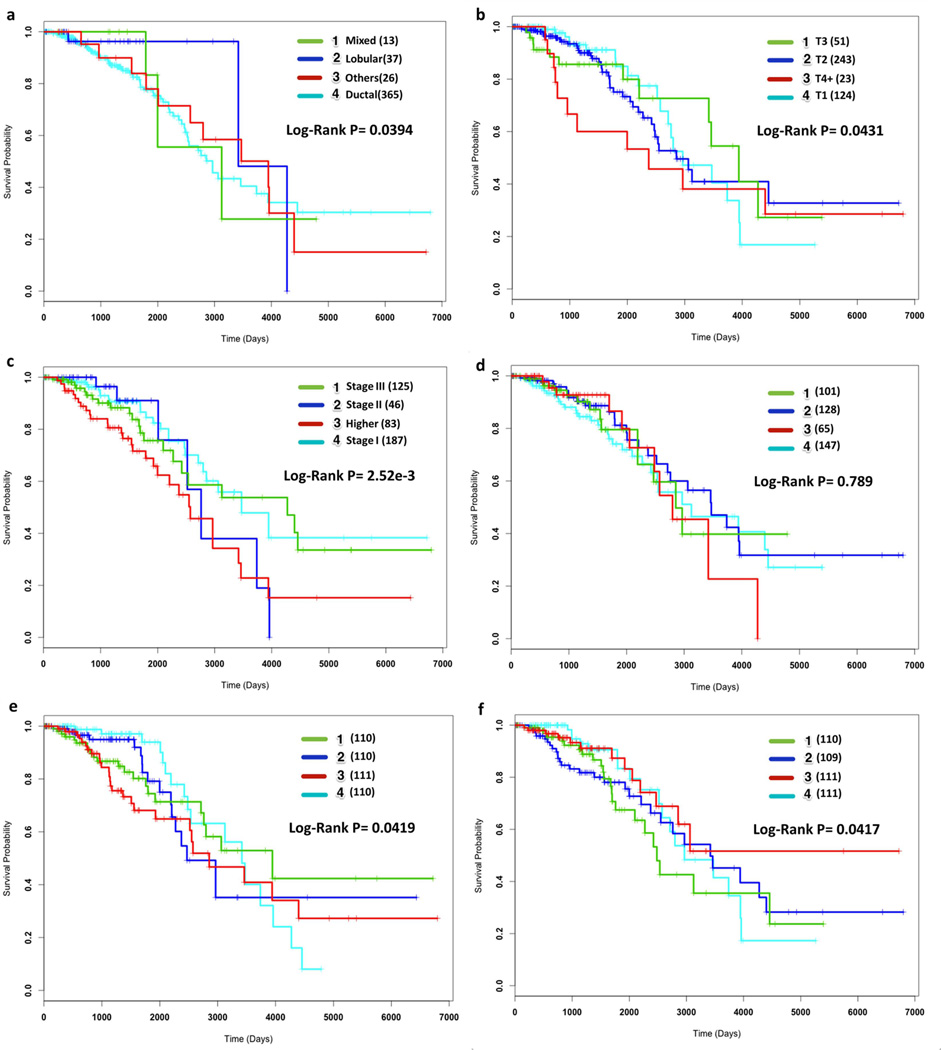

To determine the prognostic capabilities of MRCPS, we considered selected patients among the TCGA breast cancer datasets. For comparison, we provide k = 4 clusters to the each of the realizations of the CSPA, HGPA and BCE algorithm to obtain the consensus clusters eventually. These results, together with the induced clinical partitions obtained from using disease stage, tumor grade and histological type are shown in Figure 3. It is observed that infiltrating ductal carcinoma (IDC, n=365), which starts in an epithelial duct of the breast, has relatively higher risk than infiltrating lobular type (n=37) but is not distinct from mixed and other histological types in terms of overall survival (Figure 3(a)). Tumor size and disease stage are better prognostic markers than histological type (Figure 3(b) and Figure 3(c)). Patient stratifications based on the selected gene and miRNA expressions are provided in Supplementary Figure 1. Comparisons of patient stratifications based on k = 5 are provided in Supplementary Figure 2.

Figure 3.

Prognostic power of different patient stratification methods. Kaplan-Meier survival curves of (a) Histology Type, (b) Tumor Grade, (c) Disease Stage, (d) BCE, (e) HGPA and (f) CSPA listed along with estimated p-values (log-rank test). The numbers of the patients in each stratification are also listed in the parentheses.

On the other hand, the use of BCE consensus clustering method will identify subtypes that do not imply significantly distinct patient survival trends (log-rank p=0.789; Figure 3(d)). Graph-based methods, HGPA and CSPA, tend to cluster patient samples into subgroups with equal size Figure 3(e) and Figure 3(f) respectively. Moreover, they exhibit better performance(log-rank p=0.0419; Figure 3(e) and p=0.0417; Figure 3(f), respectively) than the Bayesian method, BCE, in predicting patients overall survival. This outcome can arise from the unbalanced number of clusters in the initial clustering.

We further compared these results with the subtypes derived from the proposed MRCPS method for the same patient samples. It can be observed (Figure 4) that the identified subtypes are highly predictive with log-rank p-value of 1.53e-04, admittedly lower than any other method (Figure 3). Although the sizes of subtypes are not as balanced as the ones obtained from graph-based clustering methods, the proposed MRCPS method has superior ability to differentiate patient populations with distinct outcomes. Specifically, MRCPS identifies a subtype that has significantly poorer survival rate (Red curve in Figure 4(a)).

Figure 4.

Prognostic power of MRCPS. (a) Kaplan-Meier survival curves of MRCPS with its p-value (log-rank test). (b) Disease stage in each subtype; stages earlier than stage III are considered to be early, with the rest considered to be late. (c) Tumor grades for each subtype. Grades less than T3 are considered to be lower grades, with the rest considered to be higher.

Furthermore, the identified subtypes display a good balance between early stage tumors and late stage tumors (Figure 4(b)). The association of tumor grade does not differ significantly across the subtypes (Figure 4(c)). This indicates that MRCPS clustering does not dominantly depend on tumor grade or disease stage. The partition of the patient population is also regularized by molecular affinity and other clinical attribute.

4.3. Biological Evaluation

4.3.1. Subtype-Specific Gene Analysis

We identified genes that are differentially expressed in each subtype relatively to other subtypes derived from MRCPS. To achieve this, we carried out a supervised analysis using ANOVA (false-discovery rate of 0.05) followed by Tukey post-hoc testing [18] to identify genes with differential expression between pre-defined groups. We focus on the group with the worst outcome (group 2; red curve in Figure 4(a)). Sixty (60) genes were uncovered for this subgroup with poor outcome (Supplementary Table 3). Among these genes, many have been reported to be significantly mutated, such as GATA3. Overexpression of CDH3 was also reported in esophageal, pancreatic, bladder and breast cancers [19, 20, 21, 22, 23].

Next, we conducted network and functional analysis using the Ingenuity Pathway Analysis software (IPA, fall release 2013, http://www.ingenuity.com) on the collected gene list. A network which contains 23 genes was identified (Figure 5). Interestingly, GATA3 serves as a hub gene in this network and correlates strongly with estrogen receptor. Recently, it was discovered that GATA3 serves as a licensing factor for ESR1-mediated transcription and it might potentially explain a mutant-GATA3 subtype of ESR+ breast cancer [24] and GATA3 is one of the most frequently mutated gene in breast cancers. Our observation suggests that ESR1+ patients (n=37) in this poor-outcome subgroup might be this high-risk mutant-GATA3 subtype.

Figure 5.

A gene network identified from the high-risk group.

4.3.2. Diseases and Functions of Subtype-Specific Genes

We also analyzed the specific genes for the poor outcome group using IPA. Top diseases are Cancer and Reproductive System Disease which are directly related to breast cancers (Figure 6). In addition, the top enriched functions include gene expression, cellular growth/proliferation, and cell cycle which are related to tumor development.

Figure 6.

Top diseases and functions identified from the subtype-specific genes using IPA.

5. Conclusion

In this paper, we proposed a novel consensus clustering method enabling integrative patient stratification, MRCPS, which aggregates both essential clinical information and multiple molecular expression data. Our method solves the integrative clustering problem by regulating clinical partition of patients using the molecular affinity function, and then achieves the consensus clustering by a multiplicative update. We applied MRCPS to stratify the large breast cancer patient cohort datasets collected from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA). The result shows the proposed MRCPS method can robustly combine data from different sources into reliable and clinically relevant subtypes. Specifically, a subgroup of patients with extremely poor survival was identified based on the integrative analysis.

The application of MRCPS is not limited to breast cancer. Our case study combined mRNA and microRNA expression into viable molecular features. It can also be used to identify subtypes of other types of diseases. Nonetheless, MRCPS can also consider other kinds of genomic features which are genomic in nature. Our method can be also extended to applications in which integration of both categorical and numerical datasets for clustering is needed.

One of the limitations of our method is that the number of clusters k has to be set up by the users. Another future work will be the definition of genetic difference between samples, which will allow the integration with genetic variances in subtyping cancer patients.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgement

We thank Dr. Charles L. Shapiro for helps on this study.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Chao Wang, Email: wang.2031@osu.edu.

Raghu Machiraju, Email: machiraju.1@osu.edu.

Kun Huang, Email: kun.huang@osumc.edu.

References

- 1.Perou CM, Sø rlie T, Eisen MB, van de Rijn M, Jeffrey SS, Rees Ca, Pollack JR, Ross DT, Johnsen H, Akslen La, Fluge O, Pergamenschikov a, Williams C, Zhu SX, Lø nning PE, Bø rresen Dale aL, Brown PO, Botstein D. Molecular portraits of human breast tumours. Nature. 2000;406(6797):747–752. doi: 10.1038/35021093. URL http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=3465532\&tool=pmcentrez\&rendertype=abstract. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.van’t Veer L, Dai H, Vijver MVD. Gene expression profiling predicts clinical outcome of breast cancer. nature. 415(345) doi: 10.1038/415530a. URL http://www.nature.com/nature/journal/v415/n6871/abs/415530a.html. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shen R, Mo Q, Schultz N, Seshan VE, Olshen AB, Huse J, Ladanyi M, Sander C. Integrative subtype discovery in glioblastoma using iCluster. PloS one. 2012;7(4):e35236. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0035236. URL http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=3335101\&tool=pmcentrez\&rendertype=abstract. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gade S, Porzelius C, Fälth M, Brase JC, Wuttig D, Kuner R, Binder H, Sültmann H, Beissbarth T. Graph based fusion of miRNA and mRNA expression data improves clinical outcome prediction in prostate cancer. BMC bioinformatics. 2011;12:488. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-12-488. URL http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=3471479\&tool=pmcentrez\&rendertype=abstract. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yuan Y, Savage RS, Markowetz F. Patient-specific data fusion defines prognostic cancer subtypes. PLoS computational biology. 2011;7(10):e1002227. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1002227. URL http://dx.plos.org/10.1371/journal.pcbi.1002227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yuan Y, Failmezger H, Rueda OM, Ali HR, Gräf S, Chin S-F, Schwarz RF, Curtis C, Dunning MJ, Bardwell H, Johnson N, Doyle S, Turashvili G, Provenzano E, Aparicio S, Caldas C, Markowetz F. Quantitative image analysis of cellular heterogeneity in breast tumors complements genomic profiling. Science translational medicine. 2012;4(157):157ra143. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3004330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shen R, Olshen AB, Ladanyi M. Integrative clustering of multiple genomic data types using a joint latent variable model with application to breast and lung cancer subtype analysis. Bioinformatics (Oxford, England) 2009;25(22):2906–2912. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp543. URL http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=2800366\&tool=pmcentrez\&rendertype=abstract. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Topchy A, Jain A, Punch W. A mixture model of clustering ensembles. Proc. SIAM Intl. Conf. on Data Mining. 2004:379–390. URL http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/summary?doi=10.1.1.215.2755. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang H, Shan H, Banerjee A. Bayesian cluster ensembles. Statistical Analysis and Data Mining. 2011;4(1):54–70. URL http://doi.wiley.com/10.1002/sam.10098. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lock EF, Dunson DB. Bayesian consensus clustering. Bioinformatics (Oxford, England) 2013;29(20):2610–2616. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btt425. URL http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23990412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Strehl A, Ghosh J. Cluster ensembles—a knowledge reuse framework for combining multiple partitions. The Journal of Machine Learning Research. 2003;3:583–617. URL http://dl.acm.org/citation.cfm?id=944935. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Comprehensive molecular portraits of human breast tumours. Nature. 2012;490(7418):61–70. doi: 10.1038/nature11412. URL http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/nature11412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kriegel H-P, Kröger P, Sander J, Zimek A. Density-based clustering. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Data Mining and Knowledge Discovery. 2011;1(3):231–240. URL http://doi.wiley.com/10.1002/widm.30. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Epanechnikov VA. Non-Parametric Estimation of a Multivariate Probability Density. Theory of Probability & Its Applications. 1969;14(1):153–158. URL http://epubs.siam.org/doi/abs/10.1137/1114019. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sha F, Lin Y, Saul LK, Lee DD. Multiplicative updates for nonnegative quadratic programming. Neural computation. 2007;19(8):2004–2031. doi: 10.1162/neco.2007.19.8.2004. URL http://dl.acm.org/citation.cfm?id=1268594.1268596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lin C-J. Projected gradient methods for nonnegative matrix factorization. Neural computation. 2007;19(10):2756–2779. doi: 10.1162/neco.2007.19.10.2756. URL http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17716011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Volinia S, Croce CM. Prognostic microRNA/mRNA signature from the integrated analysis of patients with invasive breast cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110(18):7413–7417. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1304977110. URL http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=3645522\&tool=pmcentrez\&rendertype=abstract. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lowry R. One-Way ANOVA: Independent Samples: II. URL http://vassarstats.net/textbook/ch14pt2.html. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nakamura T, Furukawa Y, Nakagawa H, Tsunoda T, Ohigashi H, Murata K, Ishikawa O, Ohgaki K, Kashimura N, Miyamoto M, Hirano S, Kondo S, Katoh H, Nakamura Y, Katagiri T. Genome-wide cDNA microarray analysis of gene expression profiles in pancreatic cancers using populations of tumor cells and normal ductal epithelial cells selected for purity by laser microdissection. Oncogene. 2004;23(13):2385–2400. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207392. URL http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/sj.onc.1207392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bryan RT, Atherfold PA, Yeo Y, Jones LJ, Harrison RF, Wallace DMA, Jankowski JA. Cadherin switching dictates the biology of transitional cell carcinoma of the bladder: ex vivo and in vitro studies. The Journal of pathology. 2008;215(2):184–194. doi: 10.1002/path.2346. URL http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18393367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Palacios J, Benito N, Pizarro A, Suárez A, Espada J, Cano A, Gamallo C. Anomalous expression of P-cadherin in breast carcinoma. Correlation with E-cadherin expression and pathological features. The American journal of pathology. 1995;146(3):605–612. URL http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=1869170\&tool=pmcentrez\&rendertype=abstract. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shimoyama Y, Hirohashi S. Expression of E- and P-Cadherin in Gastric Carcinomas. Cancer Res. 1991;51(8):2185–2192. URL http://cancerres.aacrjournals.org/content/51/8/2185.abstract?ijkey=26ee3dd14cf9f2db7be7a16310f56d91bf17b8bb\&keytype2=tf_ipsecsha. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sanders DS, Bruton R, Darnton SJ, Casson AG, Hanson I, Williams HK, Jankowski J. Sequential changes in cadherin-catenin expression associated with the progression and heterogeneity of primary oesophageal squamous carcinoma. International journal of cancer. Journal international du cancer. 1998;79(6):573–579. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0215(19981218)79:6<573::aid-ijc4>3.0.co;2-h. URL http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9842964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Theodorou V, Stark R, Menon S, Carroll JS. GATA3 acts upstream of FOXA1 in mediating ESR1 binding by shaping enhancer accessibility. Genome research. 2013;23(1):12–22. doi: 10.1101/gr.139469.112. URL http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=3530671\&tool=pmcentrez\&rendertype=abstract. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.