Abstract

The Family Satisfaction with End-of-Life Care (FAMCARE) has been used widely among caregivers to individuals with cancer. The aim of this study was to evaluate the psychometric properties of this measure using item response theory (IRT).

Methods

The analytic sample was comprised of caregivers to 1983 patients with advanced cancer. Among the patients, 56% were female, with mean age 59.9 (s.d. = 11.8); 20% were non-Hispanic Black. The majority were family members either living with (44%) or not living with (35%) the patient.

Factor analyses and IRT were used to examine the dimensionality, information and reliability of the FAMCARE.

Results

Although a bi-factor model fit the data slightly better than did a unidimensional model, the loadings on the group factors were very low. Thus, a unidimensional model appears to provide adequate representation for the item set. The reliability estimates, calculated along the satisfaction (theta) continuum were adequate (>0.80) for all levels of theta for which subjects had scores.

Examination of the category response functions from IRT showed overlap in the lower categories with little unique information provided; moreover the categories were not observed to be interval. Based on these analyses, a three response category format was recommended: very satisfied, satisfied and not satisfied. Most information was provided in the range indicative of either dissatisfaction or high satisfaction.

Conclusions

These analyses support the use of fewer response categories, and provide item parameters that form a basis for developing shorter-form scales. Such a revision has the potential to reduce respondent burden.

Keywords: FAMCARE, patient, caregiver, satisfaction, item response theory, psychometric properties

Satisfaction with care has emerged as a key outcome variable for evaluating quality of palliative care [1–3] and is the most commonly measured outcome for caregivers of patients receiving palliative care [4]. Caregiver satisfaction is posited to improve patient care because satisfied caregivers are better able to handle their challenging role [5,6]. Moreover, family satisfaction with care is highly correlated with patient satisfaction [7], which cannot always be measured adequately in late-stage illness.

Satisfaction with care includes the following components: accessibility, coordination, emotional support, personalization of care and support of decision making [8]. Fourteen different instruments have been used to measure family satisfaction in palliative care populations [4], several of which were developed specifically for use in such settings including the McCusker scale [9], the satisfaction scale for family members receiving inpatient palliative care [10], and the Family Satisfaction with End-of-Life Care (FAMCARE) for cancer patients [11].

The FAMCARE has been used widely [1,12–15] to support findings that families of patients receiving palliative care interventions are more satisfied with care than those in usual care receiving only such interventions as supportive social services and pain management. The FAMCARE is a 20-item scale designed to measure family satisfaction with advanced cancer care [16,17]. In one study the internal consistency and test-retest reliability were estimated as 0.91 and 0.93, respectively among cancer patients [11]. Original development of the measure identified four domains: information giving, availability of care, psychosocial care, and physical patient care [11]; although further research did not support this multidimensional framework [13,18–20], and most studies supported a unidimensional structure.

Because the scale was specifically developed for patients in home-based palliative care settings, a revised 17-item version (FAMCARE -2) was recently developed [21] in Australia for use in inpatient settings. Additionally, others have used a shortened 19-item version [22] and a 6-item version, FAMCARE-6, which was adapted for use in outpatient oncology settings [19]. Little work has been conducted among ethnically diverse samples and to our knowledge no studies have used item response theory (IRT) to examine the 20 item FAMCARE.

IRT [23] incorporates latent variable models that confer many advantages over traditional methods of item analyses, and is the methodology used in item banking projects sponsored by the National Institutes of Health [24]. Unlike those derived from classical test theory (the method most often used to examine measures), IRT parameter estimates are theoretically invariant and can be compared across groups. Classical test theory (CTT) parameters and statistics such as proportion positive, corrected item-total correlations and coefficient alpha are affected (confounded) by sample characteristics, and thus cannot be compared. Moreover, CTT internal consistency estimates are omnibus statistics in the sense that they are summary measures of reliability, whereas IRT precision or reliability estimates can be examined at varying points along the attribute continuum. It is more realistic to expect that precision is greater at varying points along the continuum than to assume that one value summarizes measure performance for all levels of the state or trait. Finally, information functions derived from the models and analyses provide a means for selection of the best item subsets when short forms are developed

The aims of this study were to examine the psychometric properties of the FAMCARE using IRT among a relatively large, ethnically diverse sample that included 388 non-Hispanic blacks.

Conceptual Model

According to the literature review above, it was posited that the measure is essentially unidimensional with one single underlying attribute, but that additional variance may be explained due to additional factors or satisfaction subscales. The items were posited to be effect indicators in that the underlying latent variable satisfaction gives rise to the indicators and accounts for the variance in the item set.

METHODS

Sample

The analytic sample was comprised of 1,983 patients with cancer from a study of palliative care. Hospitalized patients with advanced cancer were recruited from six hospitals in the Eastern and Midwestern United States to study outcomes for patients and families who receive inpatient palliative care consultation team services. Patients were required to meet the following criteria: age 18 and older, diagnosis of metastatic solid tumor or CNS malignancies, locally advanced head and neck or pancreas cancers, metastatic melanoma, or transplant-ineligible lymphoma and myeloma. Participants were excluded if their attending physician did not give permission to recruit their patients; did not speak English; had a diagnosis of dementia; were admitted for routine chemotherapy; died or were discharged within 48 hours of admission; or had previously received palliative care consultation.

The FAMCARE scale was administered to family members by a research nurse via telephone one week post discharge. If a patient died during the hospitalization, the family member was contacted by telephone two months after the death and administered the FAMCARE. These latter cases were excluded from the analyses.

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at Mt. Sinai Medical Center.

Statistical Approach

Prior to analyses, item distributions were examined. A preliminary analysis of the total sample and all five response categories was performed using item response theory. The graded response model [25] was used to evaluate the measure; such IRT methods have been recommended to model health-related constructs, e.g., [26]. The category response functions were examined in order to determine whether any categories were overlapping and if they provided unique information. The motivation for these analyses was to determine if categories should be collapsed prior to further analyses.

Subsequent factor analyses to examine dimensionality were performed using split samples, constructed by selection of two random halves in order to use one sample for cross-validation of results. The random first half of the sample was used for the exploratory factor analyses with principal components estimation and tests of scree; and the second half was used to obtain the confirmatory bi-factor solution. The bifactor model assumes that a single general trait explains most of the common variance but that group traits explain additional common variance for item subsets (see [27]).

A Schmid-Leiman (S-L) [28] transformation using the “psych” R package [29] was performed in order to find an alternative set of group factors for the bi-factor model [27]. All items were specified to load on the general factor, and the loadings on the group factors were specified following the Schmid-Leiman solution. The final bi-factor model was run using M-PLUS [28]. Polychoric correlations based on the underlying continuous normal variables were estimated using M-PLUS [30]. The explained common variance (ECV), which can be estimated as the percent of observed variance explained, provides information about whether the observed variance covariance matrix is close to unidimensionality [31]. Reliability can be evaluated by decomposing the scale score into the sum of the item scores, and the contribution of the common term or communality. Known as McDonald’s [32] Omega Total (ωt,) this reliability estimate is based on the proportion of total common variance explained. Omega Hierarchical (ωh, [33]) is calculated as the sum of the squared loadings on the general factor, divided by the total scale score variance (see [34]).

The final IRT model was evaluated using the total sample. The estimates for the discrimination and severity (location) parameters (a and b, respectively) were evaluated, the item and test information functions were graphed and the reliability estimates were calculated for points along the dimension of the underlying construct, denoted as θ (theta). The discrimination parameter informs about the strength of the relationship between an item and the trait measured, e.g., satisfaction. The severity (location) parameter indicates at what point along the satisfaction continuum the item maximally discriminates (separates or differentiates among examinees at different satisfaction levels or groups). These parameters are useful in determining which items are most informative in terms of the measurement of the underlying construct, satisfaction. IRTPRO [35] was used for IRT parameter estimation and tests of model fit.

RESULTS

Sample Characteristics

After omission of individuals who responded to less than 50% of items and those responding after the death of the family member, the analytic sample was comprised of caregivers to 1983 patients. Among the patients, 56.2% were female; the mean age was 59.9 (s.d. = 11.8), and 35.1% were 65 years of age or older. The mean educational level was 13.6 years (s.d. = 3.2); 19.6% were non-Hispanic Black and 76.5% were non-Hispanic White.

The caregivers were: family members living with the patient (43.5%), family members not living with the relative (35.0%), friends (10.5%), home health aides (1.4%), staff or certified nursing aides (0.1%); 1.6% refused to provide and 7.9% were missing the relationship.

Examination of Item Distributions

The majority of respondents (82% to 93% across items) expressed satisfaction with care. The main distinction was between the category “satisfied” and “very satisfied”. The majority of respondents reported that they were “satisfied”. Across most items, about one fourth to one third of respondents reported feeling “very satisfied” with care. For the data set analyzed here only 0.5% to 2.3% responded “very dissatisfied”, and for most of the items, 1% or fewer of respondents reported being “very dissatisfied”. Between 0% and 7.7% responded “dissatisfied,” and for the majority of items fewer than 5% of respondents reported being “dissatisfied”. Finally, between 2.1% and 6.9% responded “undecided,” with fewer than 4% of respondents reporting “undecided” for the majority (80%) of items.

Preliminary IRT analyses

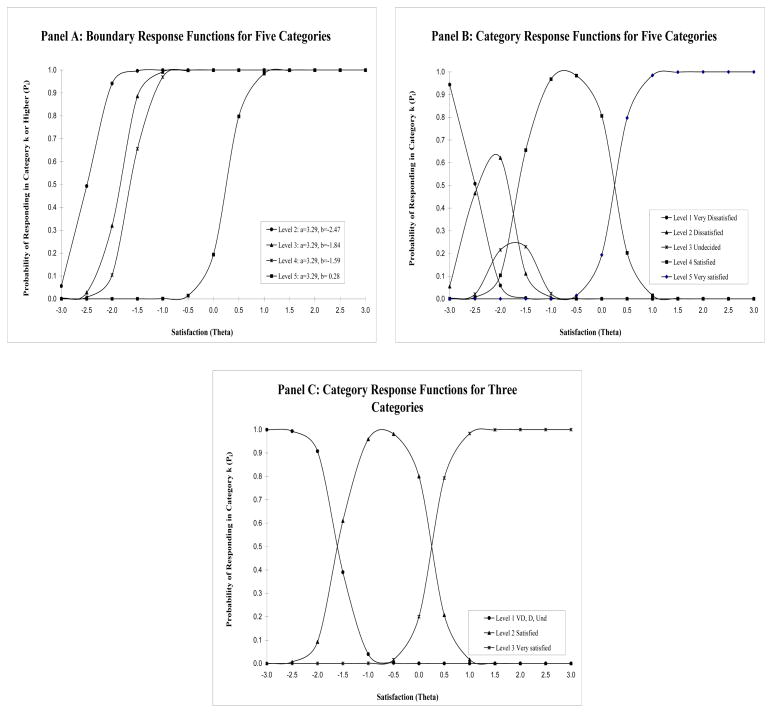

The results of preliminary IRT analyses using all response categories are given in Supplementary Figure 1; category response functions and item information functions are shown. The graphic shows the information function superimposed on the category response functions. What is evident is that for all items the lower categories are overlapping such that the probability of response is similar for these three categories: very dissatisfied, dissatisfied and undecided, indicating little if any unique information provided by these categories. As an illustration, Figure 1 shows the category and boundary response functions from the preliminary IRT analyses for an illustrative more informative item. The graphs also show that this is a relatively discriminating item with a slope of 3.21. The boundary response functions show that the distance between the lower categories is not equal and is not equal to the distance between the highest two categories, indicating the lack of interval level responses. For example, the difference in response levels between the highest two categories are much larger than that observed between the lower categories (Panel A). There is considerable overlap in the areas under the curves of the lowest three categories, indicating little unique information provided (Panel B). Moreover, the “very dissatisfied” category provides maximum information at a point (about −2.3) for which there are few or no respondents. Panel C, Figure 1 shows the category response functions after collapsing categories to three; there is little overlap among categories.

Figure 1.

FAMCARE Item 9: Doctor’s attention to patient’s description of symptoms Boundary and Category Response Functions - Five and three response categories

Due to sparse data in the very dissatisfied categories, equivocal classification in terms of the “undecided” category, and the results of the preliminary IRT analyses, items were coded as ordinal and collapsed as follows: ‘Very satisfied’ responses were coded as 2, ‘satisfied’ as 1 and indecision or ‘dissatisfaction’ as 0. The resulting sum score was from 0 to 40. The remainder of the analyses was performed using these three collapsed response categories.

Exploratory Factor Analyses (EFA)

The simple first to second eigenvalue ratio test supported essential unidimensionality (total sample: eigenvalues of 12.723 to 0.915 or 13.9 to 1; random first half of the total subsample: 12.775 to 0.929 or 13.8 to 1). The first component (eigenvalue) explained 84.4% of the variance in the total sample and 84.7% in the random first half subsample. The scree plots showed a clear dominance of the first component relative to the others (See Supplemental Figure 2). The fit indices for the unidimensional and two factor models performed by MPLUS for the total sample were: CFI one factor, 0.965, two-factor, 0.978; the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEAs) were: one factor, 0.095, two-factor, 0.080; for the first random half subsample were: CFI one factor, 0.974, two-factor, 0.973; the RMSEAs were: one factor, 0.095, two-factor, 0.087 (Supplemental Table 1).

Bifactor Analyses

Prior to analyses, the inter-item polychoric correlation matrix was reviewed; correlations range from 0.40 to 0.84 in the total sample (see Supplemental Table 2). The graphic depiction of the bi-factor model (derived from the empirical results) for the total sample tested is shown in Supplemental Figure 3. Tables 1 and Supplemental Table 3 show the factor loadings from the Schmid-Leiman and MPLUS solutions for the unidimensional and bi-factor models for the total and random split sample, respectively. The relative size of the general and group factor loadings (MPLUS two group factors) indicates a very strong general factor. Loadings for all items were higher on the general factor than any of the group factors for the total sample and the second half random subsample, suggesting essential unidimensionality. The range of the loadings on the general factor (MPLUS solution, total sample) was from 0.60 to 0.85; the range of the loading on the group factors was from 0.01 to 0.44 (see Table 1). Similarly for the second half random subsample, the range of the loadings on the general factor was from 0.59 to 0.85; the range of the loading on the group factors was from 0.12 to 0.45 (see Supplemental Table 3). The RMSEA statistic produced by “Psych” R for the Schmid-Leiman three factor solution was 0.09 for the total sample and 0.08 for the second half of the random subsample; and for the MPLUS bi-factor model it was 0.07 for the total sample and the second random half subsample (see Table 2), applied using the general and three group factor results from the Schmid-Leiman solution (see Supplemental Table 1). The fit statistics for the bi-factor models were slightly better than the unidimensional models (bi-factor total sample = CFI: 0.984; unidimensional total sample = CFI: 0.965; bi-factor 2nd half sample random subsample = CFI: 0.985; unidimensional 1st half subsample = CFI: 0.974) (Supplemental Table 1).

Table 1.

FAMCARE item loadings (λ) from the unidimensional confirmatory factor analysis (MPLUS), Schmid-Leiman bi-factor model with three group factors (performed with R) and MPLUS bi-factor three group factor solution. Total sample

| Item Description | One Fact.* λ (s.e.) | Schmid-Leiman Bi-Factor Solution | MPLUS Bi-Factor Solutions (Based on S-L** Result) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| G λ (var.) | F1 λ | F2 λ | F3 λ | h2 | G λ (s.e.) | F1 λ (s.e.) | F2 λ (s.e.) | F3 λ (s.e.) | ||

| The patient’s pain relief | 0.68 (0.01) | 0.63 | 0.23 | 0.35 | 0.57 | 0.67 (0.01) | 0.22 (0.03) | |||

| Information provided about prognosis | 0.76 (0.01) | 0.72 | 0.42 | 0.70 | 0.72 (0.01) | 0.44 (0.02) | ||||

| Answers from health professionals | 0.80 (0.01) | 0.76 | 0.35 | 0.71 | 0.78 (0.01) | 0.34 (0.02) | ||||

| Information given about side effects | 0.73 (0.01) | 0.69 | 0.39 | 0.63 | 0.70 (0.01) | 0.38 (0.02) | ||||

| Referrals to specialists | 0.75 (0.01) | 0.72 | 0.31 | 0.61 | 0.73 (0.01) | 0.28 (0.02) | ||||

| Availability of hospital bed | 0.60 (0.02) | 0.57 | 0.24 | 0.40 | 0.60 (0.02) | 0.23 (0.03) | ||||

| Family conferences held to discuss the patient’s illness | 0.74 (0.01) | 0.71 | 0.24 | 0.58 | 0.74 (0.01) | 0.18 (0.02) | ||||

| Speed with which symptoms were treated | 0.78 (0.01) | 0.73 | 0.38 | 0.69 | 0.77 (0.01) | 0.27 (0.03) | ||||

| Doctor’s attention to patient’s description of symptoms | 0.85 (0.01) | 0.80 | 0.23 | 0.73 | 0.84 (0.01) | 0.15 (0.02) | ||||

| The way tests and treatments are performed | 0.79 (0.01) | 0.74 | 0.21 | 0.27 | 0.67 | 0.79 (0.01) | 0.17 (0.03) | |||

| Availability of doctors to the family | 0.83 (0.01) | 0.79 | 0.26 | 0.70 | 0.83 (0.01) | 0.13 (0.02) | ||||

| Availability of nurses to the family | 0.68 (0.01) | 0.64 | 0.35 | 0.54 | 0.67 (0.01) | 0.34 (0.03) | ||||

| Coordination of care | 0.82 (0.01) | 0.78 | 0.25 | 0.70 | 0.81 (0.01) | 0.23 (0.03) | ||||

| Time required to make diagnosis | 0.82 (0.01) | 0.79 | 0.20 | 0.68 | 0.83 (0.01) | 0.04 (0.02) | ||||

| The way the family is included in treatment and care decisions | 0.83 (0.01) | 0.79 | 0.21 | 0.69 | 0.84 (0.01) | 0.01 (0.02) | ||||

| Information given about how to manage the patient’s pain | 0.84 (0.01) | 0.80 | 0.22 | 0.73 | 0.85 (0.01) | 0.09 (0.02) | ||||

| Information given about the patient’s tests | 0.85 (0.01) | 0.82 | 0.23 | 0.74 | 0.85 (0.01) | 0.11 (0.02) | ||||

| How thoroughly the doctor assesses the patient’s symptoms | 0.86 (0.01) | 0.82 | 0.32 | 0.77 | 0.82 (0.01) | 0.35 (0.02) | ||||

| The way tests and treatments are followed up by the doctor | 0.89 (0.01) | 0.85 | 0.35 | 0.85 | 0.85 (0.01) | 0.41 (0.02) | ||||

| Availability of the doctor to the patient | 0.86 (0.01) | 0.82 | 0.33 | 0.78 | 0.83 (0.01) | 0.33 (0.02) | ||||

| Eigenvalues | 11.29 | 0.73 | 0.77 | 0.66 | ||||||

| Correlation of scores with factors | 0.95 | 0.54 | 0.69 | 0.75 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | ||

G – general factor, F1, F2, F2, F3 – group factors, h2 – communality; (uniqueness u2 = 1- communality)

Geomin (oblique) rotation

Schmid-Leiman PC=principal components

Table 2.

Reliability, dimensionality and model fit statistics obtained from R for the three factor Schmid-Leiman solution, MPLUS v6.1 one factor and bi-factor solutions

| Statistic | Schmid-Leiman 3 Factor Solutions | MPLUS Total Sample | MPLUS Half Sample 2 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total Sample | Half Sample 2 | 1 Factor | Bi-factor | 1 Factor | Bi-factor | |

| Reliability (alpha coefficient for general factor) | 0.97 | 0.97 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Omega Hierarchical | 0.88 | 0.88 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Omega Total | 0.97 | 0.97 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| ECV | 0.99 | 0.99 | 0.64 | 0.90 | 0.63 | 0.89 |

| RMSEA | 0.09 | 0.08 | 0.10 | 0.07 | 0.09 | 0.07 |

| CFI | N/A | N/A | 0.97 | 0.98 | 0.97 | 0.99 |

| TLI | N/A | N/A | 0.96 | 0.98 | 0.96 | 0.98 |

Based on marginal reliability for response pattern scores

For the one or two factor model, omega h is not meaningful because three factors are required for identification in the calculation of omega h. However, omega total is interpretable for a unidimensional solution.

Essential unidimensionality

The essential unidimensionality estimates were high; the ECV from the Psych R program was 0.99; and 0.90 and 0.89 for the total sample and second half of the subsample from the MPLUS bi-factor model (see Table 2). ECV statistics were 0.90 for the bi-factor model for the total sample compared to 0.64 for the unidimensional MPLUS model and 0.89 compared to 0.63 for the 2nd half random subsample (Table 2). Although there appears to be some modest support for a bi-factor solution, with items loading on three group factors: 1) Doctor Involvement, 2) Information Sharing and 3) Nurse, Resource Availability, Speed and Coordination; the loadings on the group factors were very low, and nearly all items loaded much higher on the general factor, which were very similar to (within 0.03 to 0.05 of the magnitude) the loadings on the one factor solution (see Table 1). Therefore, the bolus of evidence supports an essentially unidimensional structure.

Final IRT Analyses

The IRT discrimination (a) parameters estimated with IRTPRO, ranged from the lowest 1.46 (satisfaction with “Availability of hospital bed”) to the highest 3.67 (satisfaction with “The way tests and treatments are followed up by the doctor”) (see Table 3). Additional items with discrimination parameters above 3.0 were: “How thoroughly the doctor assesses the patient’s symptoms” (3.32), “Doctor’s attention to patient’s description of symptoms” (3.21), “Availability of the doctor to the patient” (3.21), “Information given about the patient’s tests” (3.16) and “Information given about how to manage the patient’s pain” (3.02). The severity (location) parameters (b) ranged from −2.01 (“Availability of nurses to the family”) to 1.09 (“Information given about side effects”; Table 3). The range of the location parameters reflects the overall relatively high satisfaction rates with mean scores between 1 (satisfied) and 2 (very satisfied) (see Supplemental Table 4 for item means).

Table 3.

IRT item parameters and standard error estimates (using IRTPRO) for the FAMCARE item set

| Item Description | a | s.e. a | b1 | s.e. | b2 | s.e. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| The patient’s pain relief | 1.70 | 0.08 | −1.91 | 0.08 | 0.45 | 0.05 |

| Information provided about prognosis | 2.12 | 0.09 | −1.18 | 0.05 | 0.94 | 0.05 |

| Answers from health professionals | 2.50 | 0.11 | −1.40 | 0.05 | 0.59 | 0.05 |

| Information given about side effects | 1.94 | 0.09 | −1.30 | 0.05 | 1.09 | 0.06 |

| Referrals to specialists | 2.18 | 0.10 | −1.45 | 0.05 | 0.79 | 0.05 |

| Availability of hospital bed | 1.46 | 0.07 | −1.75 | 0.08 | 0.86 | 0.06 |

| Family conferences held to discuss the patient’s illness | 2.10 | 0.09 | −1.29 | 0.05 | 0.89 | 0.05 |

| Speed with which symptoms were treated | 2.34 | 0.10 | −1.52 | 0.05 | 0.50 | 0.05 |

| Doctor’s attention to patient’s description of symptoms | 3.21 | 0.15 | −1.56 | 0.05 | 0.28 | 0.04 |

| The way tests and treatments are performed | 2.50 | 0.11 | −1.62 | 0.06 | 0.54 | 0.05 |

| Availability of doctors to the family | 2.81 | 0.13 | −1.32 | 0.04 | 0.49 | 0.04 |

| Availability of nurses to the family | 1.81 | 0.09 | −2.01 | 0.08 | 0.26 | 0.05 |

| Coordination of care | 2.78 | 0.13 | −1.39 | 0.05 | 0.52 | 0.05 |

| Time required to make diagnosis | 2.83 | 0.13 | −1.35 | 0.04 | 0.66 | 0.05 |

| The way the family is included in treatment and care decisions | 2.89 | 0.13 | −1.33 | 0.04 | 0.53 | 0.04 |

| Information given about how to manage the patient’s pain | 3.02 | 0.14 | −1.40 | 0.04 | 0.71 | 0.05 |

| Information given about the patient’s tests | 3.16 | 0.15 | −1.35 | 0.04 | 0.69 | 0.05 |

| How thoroughly the doctor assesses the patient’s symptoms | 3.32 | 0.16 | −1.51 | 0.05 | 0.36 | 0.04 |

| The way tests and treatments are followed up by the doctor | 3.67 | 0.18 | −1.39 | 0.04 | 0.44 | 0.04 |

| Availability of the doctor to the patient | 3.21 | 0.15 | −1.42 | 0.04 | 0.45 | 0.04 |

The RSMEA indicative of the IRT model fit was 0.078

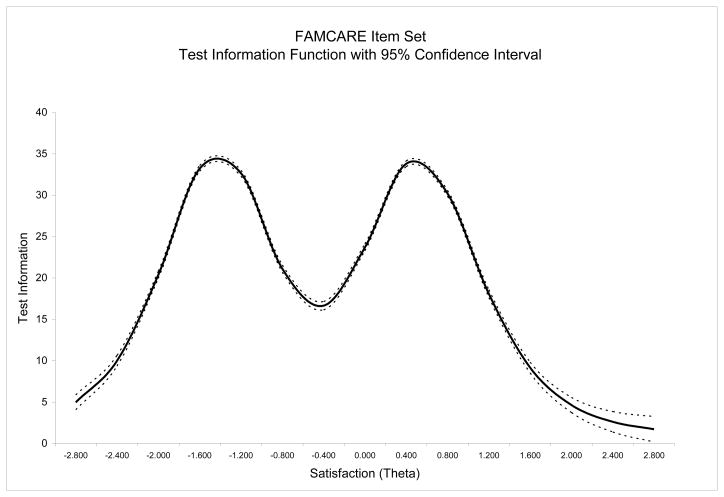

Information

The information functions (estimated using IRTPRO) for all the items in the FAMCARE item set are bimodal with two peaks where most information is provided. The first peak for individual items is in the theta area between −2.0 to −1.2 translating into the range for the sum score between 4 and 13 on the satisfaction scale. The second peak is in the theta range from 0.2 to 1.1 or the sum score range between 25.5 and 36. Most information was provided in the range indicative of either dissatisfaction or high satisfaction. Less information was provided in the range of scores indicative of reporting being “just” satisfied. (see Supplemental Figure 4 and Figure 2).

Figure 2.

FAMCARE item set: Test information function (IRTPRO)

In terms of individual items, inspection of Supplemental Figure 1 shows that little information was provided by about half of the items. The final IRT model showed that the most information was provided by about five items, particularly the last row of items. The highest information function (3.4) was for the item: “The way tests and treatments are followed by the doctor,” which peaked at the theta levels of −1.4 and then 0.4. The items providing the next highest amount of information were: “How thoroughly the doctor assess the patient’s symptoms” (2.8 at theta −1.5 and 2.7 at theta 0.4) and then the item, “Availability of the doctor to the patient” (2.6 at theta −1.4 and 0.4), “Doctor’s attention to patient’s description of symptoms” (2.6 at theta −1.6 and 0.3) and “Information given about the patient’s tests” (2.5 at theta −1.3 and 0.7). The following provided the least amount of information: “Availability of hospital bed” (0.5 at theta −1.7 and 0.8), “The patient’s pain relief” (0.7 at theta −1.9 and 0.4), “Availability of nurses to the family” (0.8 at theta −2.0 and 0.2), ‘Information given about side effects” (1.0 at theta −1.3 and 1.1).

Reliability

Different reliability estimates were obtained from several methods. The internal consistency estimate from the “psych” R package was 0.97, omega hierarchical (three group solution) 0.88, omega total (three group solution) 0.97 (Table 2). The Cronbach’s alpha reliability estimate as well as the standardized alpha was 0.95. Corrected item-total correlations ranged from 0.53 (“Availability of hospital bed”) to 0.77 (“The way tests and treatments are followed up by the doctor”) (Supplemental Table 4). Based on the IRTPRO results, the estimates of reliability were calculated along the theta continuum and ranged from 0.72 (higher end of theta) to 0.97 at theta −1.6, −1.2, and at 0.4 and 0.8 (Table 4). In general, reliability was adequate (>0.80) for all levels of theta for which subjects had scores (θ <2.2) (see Table 4). The average reliability estimate was 0.92.

Table 4.

Reliability statistics at varying levels of the attribute (theta) estimate based on results of the IRT analysis (IRTPRO)

| Satisfaction (Theta) | Reliability |

|---|---|

| −2.8 | 0.83 |

| −2.4 | 0.91 |

| −2.0 | 0.95 |

| −1.6 | 0.97 |

| −1.2 | 0.97 |

| −0.8 | 0.95 |

| −0.4 | 0.94 |

| 0.0 | 0.96 |

| 0.4 | 0.97 |

| 0.8 | 0.97 |

| 1.2 | 0.95 |

| 1.6 | 0.90 |

| 2.0 | 0.83 |

| 2.4 | 0.72 |

| Overall (Average) | 0.92 |

Estimates of reliability are provided for theta levels for which there are sample respondents. There are no observed data at theta >2.4.

Examining the distributional characteristics of the measure, the mean sum score was 23.65 (s.d.= 8.63) with the median of 21; the mean theta was −0.01 (0.95) with the median of −0.29. Skewness statistics were 0.33 (0.06) and 0.57 (0.06) and kurtosis was −0.30 (0.11) and 0.07 (0.11). The Kolmogorow-Smirnov test of normality was 0.16, p<0.001 and 0.15, p<0.001; Supplemental Table 5). Twenty percent of the respondents had a score of 20 or the average score of ‘Satisfied’ on all items and almost one third had a sum satisfaction score between 19 and 21 equivalent to the theta values between −0.5 and −0.3 (Supplemental Figure 5 and Supplemental Table 5).

DISCUSSION

Previous factor analytic studies of the FAMCARE support an essentially unidimensional solution; however, not all studies confirmed that such a solution was superior [18]. Previous studies were of smaller samples and none used item response theory to examine the items. The results of the analyses presented here indicate that although a bi-factor model fit the data slightly better than did a unidimensional model, the loadings on the group factors were very low, and the amount of improvement in fit was not large. Thus, as found by other authors [13,19,22], a unidimensional model appears to provide adequate representation for the item set.

Although at least one third of the sample responded in the middle (satisfied) range of the continuum, less information is provided by this item set at that point on the scale. More information is provided for those who are very satisfied or not satisfied. In part the relatively lower information provided in the “just” satisfied or middle range of the measure reflects inclusion of many non-informative items in this analyses. Future analyses will examine shorter version scales comprised of the more informative items.

A possible limitation of the analyses is that due to sparse data, not all response categories were used. Although collapsing categories can result in loss of information, it is often observed that item responses for satisfaction-type items are very skewed, and that typical analytic methods may not be optimal [36] because most responses are in the satisfied categories. The steps between such ordinal ratings and examination of minimal ratings may be more predictive of actual satisfaction. It may be important to distinguish very satisfied vs. satisfied because many individuals are reluctant to express dissatisfaction, and may merely select the “satisfied” category to register their dissatisfaction. Thus, the most informative distinction in satisfaction measurement may be the difference between “satisfied” and “very satisfied”.

The decision to collapse the lowest three categories into a “not satisfied” category was supported by examination of the category response functions which showed that the lowest two categories were overlapping and the third (undecided) category provided minimal or no information at its peak. Moreover, inclusion of the lower categories resulted in non-interval level responses. Based on the IRT analyses, three response categories are recommended: very satisfied, satisfied and not satisfied. Given the very sparse data, little information is obtained from the small percentage (about 1%) of individuals responding “very dissatisfied” or the roughly 3% to 4% responding “undecided”, particularly as this category is not necessarily ordinal or clear in meaning. Such a revision has the potential to reduce respondent burden.

The information provided here can serve as a basis for selecting shorter forms if desired. First, one may select the items providing the most information. Second, one may select items that provide maximal information at varying points along the continuum. The next step in these analyses is to examine differential item functioning (DIF) among various groups: age, gender, race/ethnicity and education. Items that show DIF of large magnitude are less desirable. Although shorter scales have been developed, the information provided by IRT and DIF using large, ethnically diverse samples is critical for use in developing short-form scales. The analyses presented here using a relatively large, ethnically diverse sample with application of item response theory adds to the scientific literature regarding this important measure.

Supplementary Material

Supplemental Figure 1. Item response category response and information functions

Supplemental Figure 2. Exploratory factor analysis scree plot

Supplemental Figure 3. Graphical presentation of the bi-factor model (with general and three group factors)

Supplemental Figure 4. Item information functions (IRTPRO)

Supplemental Figure 5. Histograms for the satisfaction sum score and theta estimate

Supplemental Table 1. Exploratory and confirmatory factor analyses: Model fit statistics (Comparative Fit Indices (CFI), Tucker Lewis Index (TLI) and Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA), MPLUS v6.1)

Supplemental Table 2. Polychoric correlation matrix for FAMCARE items

Supplemental Table 3. FAMCARE item set: Item loadings (λ) from the unidimensional confirmatory factor analysis (MPLUS), Schmid-Leiman bi-factor model with three group factors (performed with R) and MPLUS bi-factor three group factor solution. Two randomly selected half samples (one factor CFA for both subsamples and bi-factor solutions for the 2nd half sample)

Supplemental Table 4. Classical test reliability analysis using Cronbach’s alpha (SPSS)

Supplemental Table 5. Distribution of the summary score mapped to the FAMCARE satisfaction estimate (theta)

Acknowledgments

This project was funded by the National Cancer Institute, Grant #: 5R01CA116227-05

Support for these analyses was provided by the Claude Pepper Older Americans Independence Center: National Institute on Aging, P30, AG028741.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest

The authors do not have a financial relationship with the sponsoring organization. The authors have full control of the primary data and can provide the data for a full review if requested.

References

- 1.Ringdal GI, Jordhoy MS, Kaasa S. Family satisfaction with end-of-life care for cancer patients in a cluster randomized trial. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2002;4:53–63. doi: 10.1016/s0885-3924(02)00417-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hearn J, Higginson IJ. Do specialist palliative care teams improve outcomes for cancer patients? A systematic literature review. Palliat Med. 1998;12:317–332. doi: 10.1191/026921698676226729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wilkinson EK, Salisbury C, Bosanquet N, Franks PJ, Kite S, Lorentzon M, et al. Patient and carer preference for, and satisfaction with, specialist models of palliative care: a systematic literature review. Palliat Med. 1999;13:197–216. doi: 10.1191/026921699673563105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hudson PL, Trauer T, Graham S, Grande G, Ewing G, Payne S, et al. A systematic review of instruments related to family caregivers of palliative care patients. Palliat Med. 2010;24:656–668. doi: 10.1177/0269216310373167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Andershed B. Relatives in end-of-life care--part 1: a systematic review of the literature the five last years, January 1999–February 2004. J Clin Nurs. 2006;151:1158–1169. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2006.01473.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Milberg A, Strang P, Carlsson M, Borjesson S. Advanced palliative home care: next-of-kin’s perspective. J Palliat Med. 2003;6:749–756. doi: 10.1089/109662103322515257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Williams AL, McCorkle R. Cancer family caregivers during the palliative, hospice, and bereavement phases: a review of the descriptive psychosocial literature. Palliat Support Care. 2011;9:315–325. doi: 10.1017/S1478951511000265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dy SM, Shugarman LR, Lorenz KA, Mularski RA, Lynn J. A systematic review of satisfaction with care at the end of life. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008;56:124–129. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2007.01507.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McCusker J. Development of scales to measure satisfaction and preferences regarding long-term and terminal care. Med Care. 1984;22:476–493. doi: 10.1097/00005650-198405000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Morita T, Chihara S, Kashiwagi T. A scale to measure satisfaction of bereaved family receiving inpatient palliative care. Palliat Med. 2002;16:141–150. doi: 10.1191/0269216302pm514oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kristjanson LJ. Validity and reliability testing of the FAMCARE Scale: measuring family satisfaction with advanced cancer care. Soc Sci Med. 1993;36:693–701. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(93)90066-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Grunfeld E, Coyle D, Whelan T, Clinch J, Reyno L, Earle CC, et al. Family caregiver burden: results of a longitudinal study of breast cancer patients and their principal caregivers. CMAJ. 2004;170:1795–1801. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.1031205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ringdal GI, Jordhoy MS, Kaasa S. Measuring quality of palliative care: psychometric properties of the FAMCARE Scale. Qual Life Res. 2003;12:167–176. doi: 10.1023/a:1022236430131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dudgeon DJ, Knott C, Eichholz M, Gerlach JL, Chapman C, Viola R, et al. Palliative Care Integration Project (PCIP) quality improvement strategy evaluation. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2008;35:573–582. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2007.07.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Follwell M, Burman D, Le LW, Wakimoto K, Seccareccia D, Bryson J, et al. Phase II study of an outpatient palliative care intervention in patients with metastatic cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:206–213. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.17.7568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kristjanson LJ. Quality of terminal care: salient indicators identified by families. J Palliat Care. 1989;5:21–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kristjanson LJ. Indicators of quality of palliative care from a family perspective. J Palliat Care. 1986;1:8–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Johnsen AT, Ross L, Petersen MA, Lund L, Groenvold M. The relatives’ perspective on advanced cancer care in Denmark. A cross-sectional survey. Support Care Cancer. 2012;20:3179–3188. doi: 10.1007/s00520-012-1454-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Carter GL, Lewin TJ, Gianacas L, Clover K, Adams C. Caregiver satisfaction with out-patient oncology services: utility of the FAMCARE instrument and development of the FAMCARE-6. Support Care Cancer. 2011;19:565–572. doi: 10.1007/s00520-010-0858-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rodriguez KL, Bayliss NK, Jaffe E, Zickmund S, Sevick MA. Factor analysis and internal consistency evaluation of the FAMCARE scale for use in the long-term care setting. Palliat Support Care. 2010;8:169–176. doi: 10.1017/S1478951509990927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Aoun S, Bird S, Kristjanson LJ, Currow D. Reliability testing of the FAMCARE-2 scale: measuring family carer satisfaction with palliative care. Palliat Med. 2010;24:674–681. doi: 10.1177/0269216310373166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lo C, Burman D, Hales S, Swami N, Rodin G, Zimmermann C. The FAMCARE-Patient scale: measuring satisfaction with care of outpatients with advanced cancer. Eur J Cancer. 2009;45:3182–3138. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2009.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lord FM, Novick MB. Statistical theories of mental test scores: with contributions by A. Birnbaum. Reading Massachusetts: Addison-Wesley Publishing Company, Inc; 1968. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Reeve BB, Hays RD, Bjorner JB, Cook KF, Crane PK, Teresi JA, Thissen D, Revicki DA, Weiss DJ, Hambleton RK, Liu H, Gershon R, Reise SP, Lai JS, Cella D PROMIS Cooperative Group. Psychometric evaluation and calibration of health-related quality of life item banks: Plans for the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurment Information System (PROMIS) Medical Care. 2007;45(Suppl 1):S22–31. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000250483.85507.04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Samejima F. Psychometricka Monograph Supplement. Vol. 17. Richmond, VA: William Byrd Press; 1969. Estimation of latent ability using a response pattern of graded scores. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Teresi J, Kleinman M, Ocepek-Welikson K. Modern psychometric methods for detection of differential item functioning: Application to cognitive assessment measures. Statistics in Medicine. 2000;19:1651–1683. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0258(20000615/30)19:11/12<1651::aid-sim453>3.0.co;2-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Reise SP, Moore TM, Haviland MG. Bifactor models and rotations: Exploring the extent to which multidimensional data yield univocal scale scores. Journal of Personality Assessment. 2010;92:544–559. doi: 10.1080/00223891.2010.496477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schmid L, Leiman J. The development of hierarchical factor solutions. Psychometrika. 1957;22:53–61. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rizopoulus D. ltm: Latent Trait Models under IRT. 2009 http://cran.rproject.org/web/packages/ltm/index.html.

- 30.Muthén LK, Muthén BO. M-PLUS Users Guide. 6. Los Angeles, California: Muthén and Muthén; 1998–2010. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sijtsma K. On the use, the misuse, and the very limited usefulness of Cronbach’s alpha. Psychometrika. 2009;74:107–120. doi: 10.1007/s11336-008-9101-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.McDonald RP. Test theory: A unified treatment. Mahwah, N.J: L. Erlbaum Associates; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 33.McDonald RP. Theoretical foundations of principal factor analysis and alpha factor analysis. British Journal of Mathematical and Statistical Psychology. 1970;23:1–21. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Revelle W, Zinbarg RE. Coefficient Alpha, Beta, Omega, and the GLB:Comments on Sitsma. Psychometrika. 2009;74:145–154. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cai L, Thissen D, du Toit SHC. IRTPRO: Flexible, multidimensional, multiple categorical IRT modeling [Computer software] Chicago, IL: Scientific Software International, Inc; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fullam F, Garman AN, Johnson TJ, Hedberg EC. The use of patient satisfaction surveys and alternative coding procedures to predice malpractice risk. Medical Care. 2009;47:553–559. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3181923fd7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental Figure 1. Item response category response and information functions

Supplemental Figure 2. Exploratory factor analysis scree plot

Supplemental Figure 3. Graphical presentation of the bi-factor model (with general and three group factors)

Supplemental Figure 4. Item information functions (IRTPRO)

Supplemental Figure 5. Histograms for the satisfaction sum score and theta estimate

Supplemental Table 1. Exploratory and confirmatory factor analyses: Model fit statistics (Comparative Fit Indices (CFI), Tucker Lewis Index (TLI) and Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA), MPLUS v6.1)

Supplemental Table 2. Polychoric correlation matrix for FAMCARE items

Supplemental Table 3. FAMCARE item set: Item loadings (λ) from the unidimensional confirmatory factor analysis (MPLUS), Schmid-Leiman bi-factor model with three group factors (performed with R) and MPLUS bi-factor three group factor solution. Two randomly selected half samples (one factor CFA for both subsamples and bi-factor solutions for the 2nd half sample)

Supplemental Table 4. Classical test reliability analysis using Cronbach’s alpha (SPSS)

Supplemental Table 5. Distribution of the summary score mapped to the FAMCARE satisfaction estimate (theta)