Abstract

Vinculin is an essential structural adaptor protein that localizes to sites of adhesion and is involved in a number of cell processes including adhesion, spreading, motility, force transduction, and cell survival. The C-terminal vinculin tail domain (Vt) contains the necessary structural components to bind and cross-link actin filaments. Actin binding to Vt induces a conformational change that promotes dimerization through the C-terminal hairpin of Vt and enables actin filament cross-linking. Here we show that Src phosphorylation of Y1065 within the C-terminal hairpin regulates Vt-mediated actin bundling and provide a detailed characterization of Y1065 mutations. Furthermore, we show that phosphorylation at Y1065 plays a role in cell spreading and the response to the application of mechanical force.

The ability of cells to respond to external mechanical stimuli, encountered, for example, during cell spreading or in response to pulses of force, requires signaling to be transduced via transmembrane receptors to the actin cytoskeleton. These mechanical stimuli initiate signaling cascades, permitting the cells to adapt appropriately. Integrins, a major class of transmembrane receptors that link the extracellular matrix (ECM) to the actin cytoskeleton, are involved in force transmission.1 These transmembrane receptors can activate a number of signaling pathways and cellular processes, including cytoskeletal rearrangements and assembly of focal adhesions (FAs).2,3 External forces that are applied to the cell via linkages with the ECM to integrins promote cellular stiffening by activating pathways that promote cell contractility. For instance, signaling downstream from integrins leads to the activation of RhoA and promotes an increase in actomyosin contractility and adhesion maturation.4−7 Additionally, FA scaffolding proteins such as vinculin are rapidly recruited to areas under tension, and loss of vinculin results in a failure to respond to external applications of force.8−10 Although vinculin can be recruited to FAs and reinforces the adhesion under tension, this mechanism is poorly understood.8 Consistent with these observations, variants of vinculin that are impaired in actin bundling significantly impair cell stiffening in response to pulses of external force.11,12

Vinculin is a highly conserved and large (1066 amino acids) structural adaptor protein that localizes to both FAs and adherens junctions.13,14 Furthermore, vinculin is essential for embryonic development, as vinculin knockout mice show defects in heart and neural tube formation and do not survive past day E10.5.15 Fibroblasts isolated from knockout mice exhibit a number of defects, including a rounded morphology, increased motility,15 and resistance to apoptosis and anoikis.16 At the subcellular level, vinculin has been implicated in the regulation of FA turnover,17 FA dynamics at the leading edge of migrating cells,18 and force transduction.19 However, the mechanism by which vinculin regulates these various functions remains to be fully characterized.

Vinculin contains three main domains: a large, helical head domain (Vh), a proline-rich linker region, and a tail domain (Vt). Each of these respective regions binds to a number of proteins. While talin, α/β-catenin, α-actinin, MAPK, and IpaA from Shigella flexneri bind to Vh,20−25 VASP, Cbl-associated protein (CAP)/ponsin, vinexin α/β, nArgBP2, p130CAS, and the Arp2/3 complex associate with the proline-rich linker.26−31 A number of ligands also bind Vt including PKCα, paxillin, Hic-5, raver1, α-synemin, PIP2, and F-actin.32−39 In the autoinhibited conformation, vinculin is unable to interact with binding partners due to intramolecular interactions between Vt and Vh.40−42 Vinculin is considered to be active upon release of Vt and Vh through combinatorial binding of ligands to each domain.41,43 Additionally, it has been shown that when external forces are applied to cells, there is a robust recruitment of vinculin to FAs.8 However, the exact mechanism that controls the activation of vinculin in response to mechanical stimuli has yet to be fully elucidated. Once vinculin adopts an open conformation, additional binding partners are recruited to maturing adhesion complexes.44,45 In FAs, vinculin aids in transducing mechanical cues by linking integrins with the cytoskeleton through its association with talin and F-actin.

Upon binding to F-actin, Vt undergoes a conformational change that exposes a cryptic dimerization site that enables F-actin bundling.35,45 In recent years, models for how Vt binds to and bundles F-actin have been proposed.45,46 Janssen et al. proposed a structural model of the Vt/F-actin complex using negative-stain electron microscopy and computational docking, in which Vt binds to F-actin through two sites: site one binds via helices 2 and 3 and site two binds through helices 3, 4, and the C-terminus.46 In the proposed model, deletion of the N-terminal strap impairs actin bundling, while deletion of the C-terminus enhanced actin bundling.46 However, contrasting data have arisen that support a distinct hydrophobic Vt interface critical for the association with actin on helix 4.47−49 Recent studies have shown that the C-terminal hairpin of Vt is essential for Vt self-association and subsequent F-actin cross-linking.11,50

Within the C-terminal hairpin, there is a known Src phosphorylation site, Y1065, which is the only tyrosine residue within Vt. Vinculin was one of the first substrates identified to be phosphorylated by the transforming oncogene of Rous sarcoma virus, v-Src.51 Previous studies have shown that phosphorylation of Y1065 alters a number of cellular processes including traction forces, exchange from adhesions, and cell spreading.52,53 Phosphorylation at Y1065 has also been shown to affect intramolecular interactions with Vh and binding to the Arp2/3 complex.53,54

In this study, we provide evidence that Src phosphorylation of Vt disrupts F-actin bundling but retains binding to F-actin. This phosphorylation also prevents binding to Vh, but does not affect binding to PIP2. These results are consistent with our findings that the C-terminal hairpin of Vt, containing Y1065, is critical for F-actin bundling.11 Additionally, we show that mutation of Y1065 to phenylalanine (Y1065F), a common nonphosphorylatable variant, enhances F-actin bundling capacity, disrupts binding to Vh, but retains binding to other ligands. We have also structurally characterized alternate Vt variants that either mimic (Y1065E) or prevent phosphorylation (Y1065A) to study the impact of phosphorylation at Y1065 on actin binding and bundling. Using these variants, we have examined their impact on FA morphology, cell spreading, and cellular stiffening in response to force in vinculin knockout murine embryo fibroblasts (Vin −/– MEFs).

Materials and Methods

Expression and Purification of Proteins

Expression of chicken Vt (residues 879–1066) was performed as previously described.55 Full-length vinculin was transformed into E. coli strain BL21-DE3 RIPL cells and purified as previously described.12,47 The final product was evaluated by SDS-PAGE for purity prior to use in biochemical assays. The kinase domain of c-Src (residues 251–533) was kindly provided by J. Kuriyan’s laboratory at the University of California (Berkeley, CA) and was purified as previously described.56 The purified protein was stored in 50% glycerol aliquots at −20 °C until use.

Expression and purification of GST and GST-Vh (residues 1–811) were performed as previously described30,57 with minor modifications. Briefly, GST-Vh was transformed into the E. coli strain JM109. 500 mL cultures were grown at 37 °C until induced with 0.1 mM IPTG at an OD of 0.6. The cultures were then grown at room temperature for an additional 12–16 h. Cells were lysed in 1× PBS, 1% Triton X-100 in the presence of 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride and 10 μg/mL of aprotinin and leupeptin. GST and GST-Vh were purified by incubation with glutathione-sepharose 4B beads (GE Healthcare) at 4 °C for 3 h and then washed three times with 1× PBS.

Generation of Phosphorylated Vt

Following initial purification, WT Vt was dialyzed into phosphorylation reaction buffer (50 mM HEPES, 1 mM MgCl2, 1 mM MnCl2, 1 mM DTT, pH 7.5) prior to incubation with ∼1 μM Src and 2 mM ATP at 37 °C overnight. To separate phosphorylated Vt, the sample was loaded onto a weak cation-exchange column with buffer A (20 mM Tris, 20 mM NaCl, 2.5 mM EDTA, 1 mM DTT, pH 7.5) and eluted using a gradient from 20 mM to 380 mM NaCl. Fractions were collected and verified for phosphorylation by Western blotting using a phosphotyrosine antibody (Santa Cruz). To determine the stoichiometry of the phosphorylated sample collected through this method, samples were dialyzed in 10 μM ammonium bicarbonate prior to submission for analysis by Fourier transform ion cyclotron resonance mass spectrometry (FTICR-MS).

Actin Cosedimentation Assays

Actin binding and bundling by Vt and full-length vinculin were measured with a cosedimentation assay as previously described.11,12 For bundling assays, samples were prepared as described for the actin binding experiment except samples were subjected to a low speed spin (5000 × g). Pellet and soluble fractions were separated by SDS-PAGE, the band intensity was calculated using ImageJ,58 and percentages were calculated as previously described.11

Lipid Cosedimentation Assays

Vt binding to phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate (PIP2) was evaluated by lipid cosedimentation assays using small, unilamellar vesicles as previously described.12,55 Relative protein amounts were quantified using ImageJ.58

Fluorescence Microscopy of F-Actin Bundles

F-actin bundles were induced by the addition of full-length vinculin or Vt variants to 10 μM actin. The bundles were visualized using fluorescence microscopy as previously described.11,18,59 Images were acquired on a Zeiss axiovert 200M microscope equipped with a 63× objective lens and a Hamamatsu ORCA-ERAG digital camera.

Circular Dichroism (CD)

Spectra were collected from 350 to 250 nm (near-UV) and 260–190 nm (far-UV) at protein concentrations of 450 and 5 μM, respectively. Data were collected on a Jasco J-815 CD spectrometer (Jasco; Easton, MD) and on an Applied Photophysics Pistar-180 spectrometer at 25 °C in CD buffer (10 mM potassium phosphate and 50 mM Na2SO4, pH 7.5)

Thermal Stability of Vt

Fast quantitative cysteine reactivity (fQCR) was used to measure changes in protein stability as previously described.60 1 μM Vt was incubated with 1 mM 4-fluoro-7-aminosulfonylbenzofurzan (ABD-F, Anaspec) in fQCR buffer (25 mM KPO4, 100 mM KCl, pH 7.5) for 1 min at the desired temperature before being quenched with 0.1 N HCl. The fluorescence intensity was measured on a PHERAstar plate reader (BMG Labtech). The data were normalized and fit to a sigmoidal dose–response curve to determine the temperature at which 50% of the protein was unfolded, representing the Tm. The slope as Vt transitioned from folded to unfolded was used as an indicator of cooperativity for the unfolding protein. Data represents the mean ± SEM. Experiments were performed in triplicate for two independent trials. Data sets were analyzed using the two-tailed Student’s t test for p-values.

NMR Spectroscopy

Vt samples for NMR were prepared from cells grown in M9 media with 15NH4Cl as the sole nitrogen source. The 15N-Vt samples were exchanged into NMR buffer (10 mM KH2PO4, 50 mM NaCl, 0.1% NaN3, 2 mM DTT, and 10% D2O, pH 5.5) and concentrated to 50 μM for WT Vt, Vt Y1065F, Vt Y1065A, and Vt Y1065E and 35 μM for pY-Vt. All heteronuclear single quantum coherence (HSQC) spectra were collected on a Varian INOVA 700 MHz spectrometer at 37 °C. Processing was done with NMRPipe61 and spectral analysis with NMRViewJ.62

Vinculin Head–Tail Pulldowns

Pulldown assays were performed as previously described53 with the following modifications. Purified Vt and Vt variants were dialyzed into TEEAN buffer (20 mM Tris, 150 mM NaCl, pH 7.5). Protein concentration was calculated and adjusted to 10 μM per reaction with TEEAN buffer containing 0.5% CHAPS, 1% BSA, 0.5 mM β-mercaptoethanol. Approximately 10 μM of GST and GST-Vh were used for the pulldown experiments. Incubations (450 μL) were nutated at 4 °C for 2 h. The samples were collected by brief centrifugation and washed four times in TEEAN. Samples were boiled in sample buffer and separated by SDS-PAGE. Vt protein bands were detected using a rabbit anti-chicken Vt antibody,11 a gift from Dr. Susan Craig (Johns Hopkins University). GST was detected with a polyclonal anti-GST antibody (Molecular Probes).

Cell Culture and Transfection

Vinculin knockout murine embryo fibroblasts (Vin −/– MEFs) were obtained from Dr. Eileen Adamson (Burnham Institute; La Jolla, CA) and grown in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM; Invitrogen) supplemented with 5% fetal bovine serum and antibiotic-antimycotic solution in 10% CO2 at 37 °C. DNA constructs were generated for cell culture as previously reported.11 Cells were transfected with GFP-tagged vinculin expression constructs using Lipofectamine (Invitrogen) and Plus Reagent (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer’s protocol and examined 24–72 h following transfection.

RTCA and Spreading

Prior to plating, cells were serum-starved in DMEM media supplemented with 0.5% delipidated BSA and antibiotic-antimycotic solution. Cells were then resuspended in the serum-free delipidated BSA media for approximately 2 h. For the real-time cell analyzer (RTCA) xCELLigence System (Acea Biosciences), 3500 cells per well were seeded into the E-plate 16 that was coated with 50 μg/mL fibronectin (FN). Attachment and spreading were monitored by impedance, given as the arbitrary unit, cell index (CI), and was recorded with the RTCA apparatus every 15 s over a 4 h time period. For the spreading assay and subsequent adhesion site analysis, cells were prepared as described above prior to seeding onto glass coverslips coated with 50 μg/mL FN. Cells were fixed for 10 min with 3.7% formaldehyde and washed once with 1× PBS. Cells were then permeabilized for 10 min with 0.2% Triton X-100 in PBS and stained with phalloidin (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) and examined with a Zeiss axiovert 200M microscope equipped with a 63× objective lens and a Hamamatsu ORCA-ERAG digital camera. FAs were quantified as previously reported.11 Experiments were repeated three independent times and the resulting data representing the mean ± SEM. Data sets were analyzed using the two-tailed Student’s t test for p-values.

Force Microscopy

Three-dimensional force microscopy (3DFM) was used to apply controlled force to integrins in order to track bead displacements as an indicator of cellular reinforcement. Experiments and analysis were performed as previously described.11,12 Tracked bead displacements were analyzed using the two-tailed Student’s t test for p-values and are reported as mean ± SEM.

Results

Phosphorylation or Mutation at Y1065 Does Not Affect Actin or PIP2 Binding, but Alters Actin Bundling

Removal of the C-terminal residues (1052–1066) from Vt was previously found to enhance F-actin bundling.46 However, the C-terminus forms interactions with the helical core of Vt and the N-terminal strap, and large C-terminal deletions beyond seven amino acids lead to destabilization of the protein.17,55 The destabilizing effects of large C-terminal deletions are further supported through protease digestion studies.17 We previously demonstrated that a C-terminal hairpin deletion mutant (Vt ΔC5) retains the structural integrity and actin binding of Vt, but is significantly disrupted in its ability to bundle actin filaments11 and impairs formation of the actin-induced Vt dimer.11 These findings suggest that the C-terminal hairpin is critical for actin-induced Vt dimerization, which in turn is necessary for F-actin bundling. Since Y1065 lies within the C-terminal hairpin and is the sole Src phosphorylation site in Vt, we examined the impact of phosphorylation or mutation at Y1065 on the ability of Vt to bind and consequently bundle F-actin. To generate phosphorylated Vt (pY-Vt) we incubated purified Vt with the c-Src kinase domain and separated phosphorylated from unmodified Vt by anion exchange chromatography. Modification of Vt Y1065 by phosphorylation was verified by Fourier transform ion cyclotron resonance mass spectrometry and determined to be ∼84% phosphorylated (Figure S1, Supporting Information).

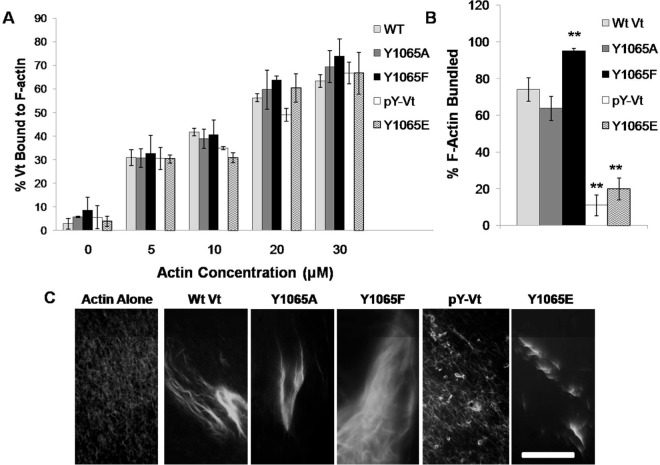

Consistent with our previous observations that removal of the C-terminal hairpin does not alter actin binding, Y1065 variants and pY-Vt showed a similar association with actin compared to WT Vt in actin cosedimentation assays (Figure 1A and Table S1, Supporting Information).11,53 However, significant differences were observed for actin bundling (Figure 1B and Table S1). While wildtype (WT) Vt and Vt Y1065A showed approximately the same actin bundling efficiency, Y1065F exhibited significantly higher bundling capacity than WT Vt. In contrast to WT Vt, pY-Vt, and Y1065E showed greater than 3-fold reduction in their bundling efficiency.

Figure 1.

Actin binding and bundling with pY-Vt and Vt Y1065 mutants. (A) Actin binding and (B) actin bundling cosedimentation assays in the presence of WT Vt and Y1065 Vt mutants. (C) fluorescence microscopy of actin bundles formed by Vt Y1065 variants. **p ≤ 0.001 comparing Y1065 variants to WT Vt. Error bars are ± S.E.M., n = 3. Scale bar: 25 μm.

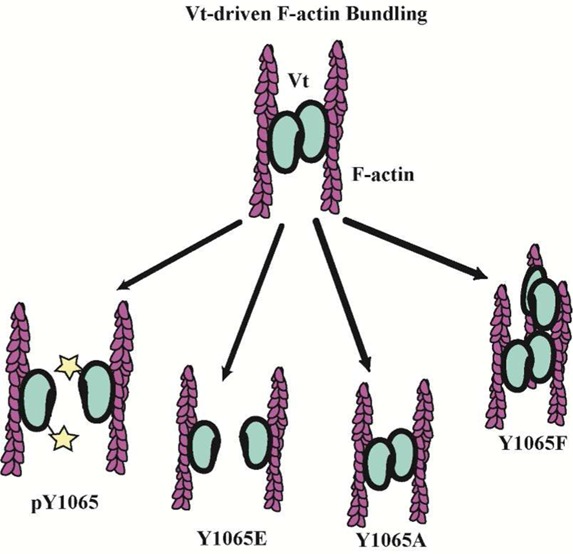

To visualize the bundles formed in the presence of the Vt variants, we viewed the F-actin bundles by fluorescence microscopy. As shown in Figure 1C, single actin filaments are observed in the absence of Vt. However, in the presence of WT Vt and Vt Y1065A, most of the filaments are packed into thick actin bundles, similar to bundles previously observed.11 Upon incubation of Y1065F with F-actin, larger F-actin bundles are observed, which would account for the high bundling efficiency observed in the actin bundling cosedimentation assays. As a result of this finding, we have termed Vt Y1065F a “superbundler.” However, upon phosphorylation or mutation to Y1065E, there is a deficiency in the ability of the variants to form bundles that resemble WT Vt. While some small bundles do form, they lack the persistence observed with the native protein. Results from the actin bundling cosedimentation assays and the bundles observed by fluorescence microscopy both indicate that Y1065A behaves similarly to WT Vt, while Y1065F shows significantly enhanced F-actin bundling in comparison to WT Vt. Furthermore, phosphorylation or mutation to a phosphomimetic (Y1065E) disrupted actin bundle formation to approximately the same severity. Previous studies have shown that deletion of the C-terminal hairpin disrupts actin bundling due to a disruption in forming the actin-induced dimer.11 Since Y1065 is located within the C-terminal hairpin and we observe similar disruptions in actin bundling, we conclude that phosphorylation at Y1065 can regulate Vt-driven F-actin bundling.

On the basis of studies using Vt C-terminal deletion variants (residues 1052–1066) and C-terminal peptides derived from Vt, it has been proposed that the Vt C-terminus is critical for association and insertion of Vt into membranes.40,63,64 However, these studies were performed with destabilizing Vt variants or the C-terminal peptide alone and may not accurately portray interactions with vinculin and PIP2. In fact, we showed that loss of the C-terminal hairpin does not affect the association of Vt with PIP2.55 Therefore, we anticipated that mutation or phosphorylation of Y1065 within Vt would not affect PIP2 association. To verify this, we performed lipid cosedimentation assays to assess their binding to PIP2. As shown in Figure S2, Supporting Information, neither phosphorylation nor mutation at Y1065 alters the association of Vt with PIP2-containing liposomes. These data support our previous findings that the Vt C-terminal hairpin is not required for association with PIP2 and contradict previous studies using a vinculin C-terminal peptide that propose a role for Y1065 phosphorylation in regulating membrane association.64

Mutation or Phosphorylation of Y1065 Retains the Vt Helix Bundle Fold

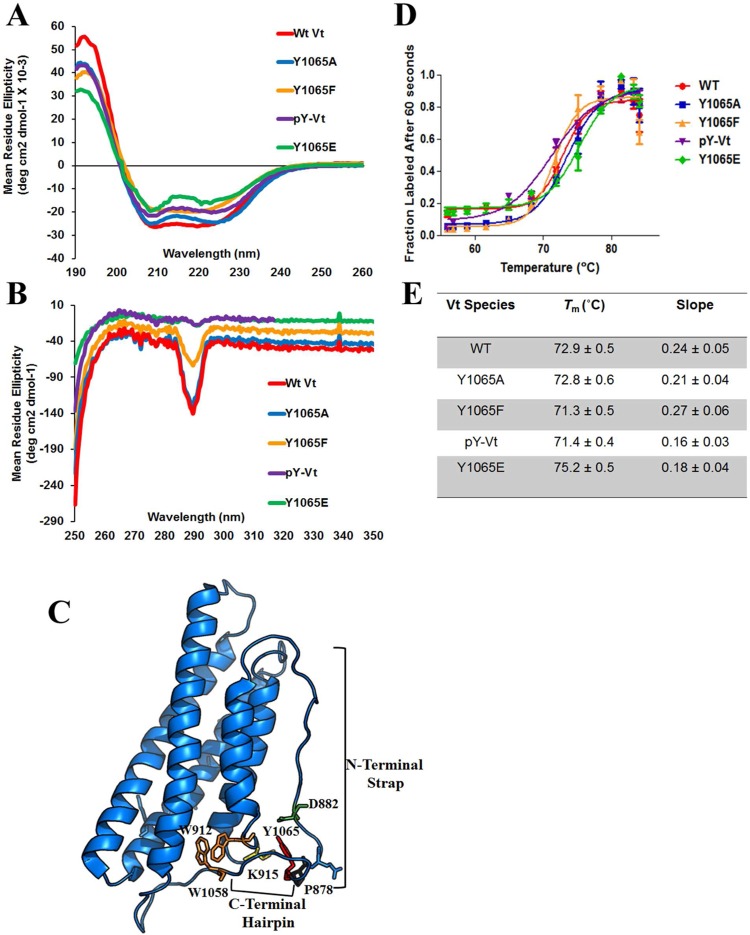

Because of the different actin bundling efficiencies displayed by the Vt variants, we next performed near and far-UV circular dichroism (CD) spectroscopy experiments to examine the overall secondary and tertiary structure of pY-Vt and Vt variants in comparison to WT Vt. As shown in Figure 2A, far-UV spectra for Y1065 variants and pY-Vt were similar to WT Vt, indicating that mutation or modification of Y1065 does not significantly alter the overall α-helical signature of Vt. Next we examined near-UV spectra of the Y1065 mutants and pY-Vt (Figure 2B). These data are sensitive to tertiary interactions between the N-terminus and C-terminus, due to aromatic packing interactions between W912 in the H1–H2 loop and W1058 in the C-terminal extension, (Figure 2C).55 While the near-UV spectra of WT Vt and Vt Y1065A are similar, we observe a loss of tryptophan packing when Y1065 is mutated to phenylalanine, glutamic acid, or phosphorylated. These results indicate a disruption in tryptophan packing. This suggests that, though the C-terminus of Vt is flexible,12,40 altering the chemical environment can impact packing at the bottom of the helix bundle. This is especially evident in the cases of pY-Vt and Vt Y1065E, which show the same disruption in tryptophan packing, suggesting that the presence of a negative charge alters interactions of the C-terminus within Vt. Additionally, these data indicate that Y1065F, previously used as a typical nonphosphorylatable Vt variant, does not share some structural characteristics with unmodified WT Vt, a criteria that should be met. Rather, Y1065A most closely resembles nonphosphorylated WT Vt as shown by our actin bundling data (Figure 1B,C, Table S1). However, our far-UV CD data suggest that loss of these C-terminal contacts do not significantly perturb the overall secondary structure of the helix bundle, likely due to the higher conformational heterogeneity of the C-terminal arm.

Figure 2.

CD and fQCR of pY-Vt and Y1065 variants. (A) far-UV CD spectra and (B) near-UV CD spectra upon phosphorylation and mutation to Y1065. (C) The side chain of Y1065 (red) lies within the C-terminal hairpin (D) fQCR curves show temperature dependence of cysteine accessibility, used to monitor Vt unfolding properties as buried cysteines within Vt become exposed and modified by ABD-F upon Vt unfolding. (E) Results indicate no significant changes in Tm upon phosphorylation or mutation, but differences in cooperativity of the unfolding protein are observed upon phosphorylation and mutation to Y1065E.

To evaluate if mutation or phosphorylation at Y1065 alters the stability of Vt, we performed fast quantitative cysteine reactivity (fQCR), a technique that uses a thiol-reactive fluorescent indicator that covalently modifies cysteines as they become exposed when the protein unfolds over a thermal gradient.60 Similar to a standard CD thermal melt, the fluorescent readout can be used to determine the Tm of a protein and provides an indication of the thermostability and cooperativity of protein unfolding. Vt has three buried cysteines (C950, C972, and C985) that become exposed upon thermal unfolding. Hence, cysteine reactivity can be used to monitor thermal unfolding. As shown in Figure 2D,E, the Tm of the various Vt variants is not significantly different; however, the unfolding transition for pY-Vt and Y1065E is slightly less cooperative. These results in combination with our near-UV CD data indicate that pY-Vt and Y1065E cause some disruption in packing interactions likely due to alternate interactions of these negatively charged residues within Vt. Overall, these data suggest that while mutation or modification of Y1065 does not alter the overall stability of the protein, the presence of a negative charge at Y1065 can slightly alter helix bundle packing interactions.

Next, we collected 1H–15N 2D heteronuclear correlation spectra (HSQC) on 15N-enriched WT Vt, Y1065 variants and pY-Vt, to further delineate how Y1065 mutations and phosphorylation alter Vt. 1H–15N HSQC NMR spectra report on HN resonances associated with the protein backbone (except for proline) and side chains, and give signals that are very sensitive to changes in the local chemical environment of these nuclei. By monitoring the position of peaks from backbone amides, the local or global consequences of a perturbation within a protein can be tracked. Furthermore, changes in peak intensity and/or line widths indicate the possibility of changes in the dynamics of the protein. If signal changes correspond to residues near the site of mutation or phosphorylation, this would indicate that the mutation or phosphorylation likely had little effect on the global structure and dynamics of the protein. However, if changes in the chemical shifts and/or intensity of amide peaks are observed for a significant fraction of the peaks corresponding to residues remote from the site of perturbation, this can indicate that the perturbation may alter the structural and dynamic properties of the protein. As shown in Figure S3, Supporting Information, Vt produces a spectral dispersion indicative of a well-folded protein. Phosphorylation or mutations at Y1065 do not change this. Overall, the amide resonances do not show significant changes in chemical shift, intensity, or line width in comparison to WT Vt. However, a small subset of NH peaks show changes in chemical shift and/or line width upon mutation or phosphorylation of Y1065. These changes have been labeled on the respective HSQC spectra (Figure S3A–D) and mapped onto the structure of Vt in Figure S3E. The changes are mostly localized to the C-terminal arm of Vt, though some extend out to helix 5, the helix 3–helix 4 loop, and the interface between the N-terminal strap and helix 1. In conjunction with our CD and Tm results, these data indicate that mutation or phosphorylation of Y1065 does not significantly alter the helix bundle fold. This is not surprising given previous work examining the similarities between NMR spectra of WT Vt in comparison to C-terminal hairpin deletion (Vt ΔC5 and VtΔC2) variants.55 Notably, C-terminal hairpin deletions lead to small shifts that are observed with NH resonances associated with residues near the loop between helix 1 and 2 and residues within helix 5. These small shifts may occur due to loss of the Y1065 phenol, since this side chain forms weak contacts with residues in the Vt N-terminus.41 The changes in the HSQC that correspond to residues further from Y1065 are likely propagated through the C-terminal arm and the N-terminal strap, not through the helices comprising the bundle. This is in agreement with the absence of defined secondary structure in these regions and their increased flexibility, relative to the helix bundle.12

Phosphorylation and Mutations at Y1065F Alter Vinculin Head–Tail Interactions

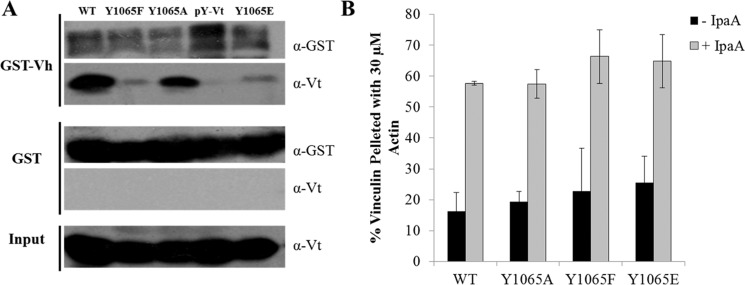

Structures of full-length vinculin have been obtained for its autoinhibited or inactive conformation.41 In these structures, numerous intramolecular contacts were observed between Vt and D1, D3, and D4 of Vh.41,65 Consistent with the numerous autoinhibitory contacts between Vh and Vt, Vt interacts with both D1 and D4 of Vh, which mediates head–tail interactions and the active state of vinculin.44,66 Src phosphorylation of vinculin at Y1065 has been implicated in disrupting head–tail interactions to activate vinculin.53 We wanted to examine how our Y1065 mutations bound to Vh by performing head–tail pulldowns with GST-tagged Vh (contains D1–D4; residues 1–811) and evaluated differences in head–tail interactions. When pulldowns were performed at a head/tail ratio of 1:1, we found that WT Vt and Y1065A retained binding to the head domain (Figure 3A), whereas pY-Vt and Y1065E exhibited reduced binding to Vh. The reduction in binding observed for pY-Vt and Y1065E is not surprising in light of previous findings that pY-Vt may disrupt autoinhibitory interactions between Vh and Vt (Figure 3A).53 Surprisingly, Y1065F also showed reduced binding to GST-Vh, indicating a perturbation in head–tail interactions (Figure 3A). Y1065F has been used previously as a nonphosphorylatable variant, but our findings indicate that Y1065F not only enhances actin bundling but also reduces association with Vh. These results indicate that studies using Y1065F vinculin to prevent phosphorylation in cells could be misleading.

Figure 3.

Phosphorylation of Y1065 and select Y1065 mutants alter Vt binding to Vh, but do not ablate head–tail interactions. (A) The variants were incubated with either GST alone or the GST-Vh domain protein (residues 1–811). Bound proteins were eluted off the beads and probed with the indicated antibodies. (B) The Y1065 mutants bind actin in the presence of the activating virulent peptide, IpaA.

To determine whether head–tail defects are observed in the context of full-length protein, we performed actin cosedimentation assays with the Y1065 mutants in full-length vinculin either with or without IpaA peptide. IpaA is a peptide derived from virulent factor from Shigella flexneri, which has been shown to be sufficient to activate vinculin.43 If the Y1065 mutations greatly perturb head–tail interactions, we expect those variants to bind to F-actin in the absence of IpaA since F-actin alone is not sufficient to release head–tail intramolecular contacts.67 In the absence of IpaA, the Y1065 variants are unable to bind or bundle actin. These findings indicate that the vinculin Y1065 mutations are unable to significantly disrupt head–tail interactions in the context of the full-length protein (Figure 3B). Similar to previous observations, Y1065A vinculin can bind and bundle F-actin similar to WT vinculin in the presence of the IpaA peptide. In contrast, Y1065E vinculin is unable to bundle actin in the presence of IpaA while Y1065F vinculin displays a higher bundling efficiency (Figure S4A,B, Supporting Information). These results are consistent with a previous observation that phosphorylation of full-length vinculin is not sufficient to facilitate F-actin association.53 When F-actin is visualized by fluorescence microscopy, bundle formation is observed with WT, Y1065A, and Y1065F vinculin, but not Y1065E, in the presence of the IpaA peptide (Figure S4B). These data indicate that the head–tail defects observed by the Vh-Vt pulldown assay are not enough to overcome the head–tail intramolecular interactions that would allow full-length vinculin variants to bind F-actin in the absence of the IpaA peptide. Furthermore, these results show that comparable behavior is observed between Vt and the full-length protein, which is not surprising given the structural similarities of isolated Vt and its conformation in in full-length vinculin.3,40,41

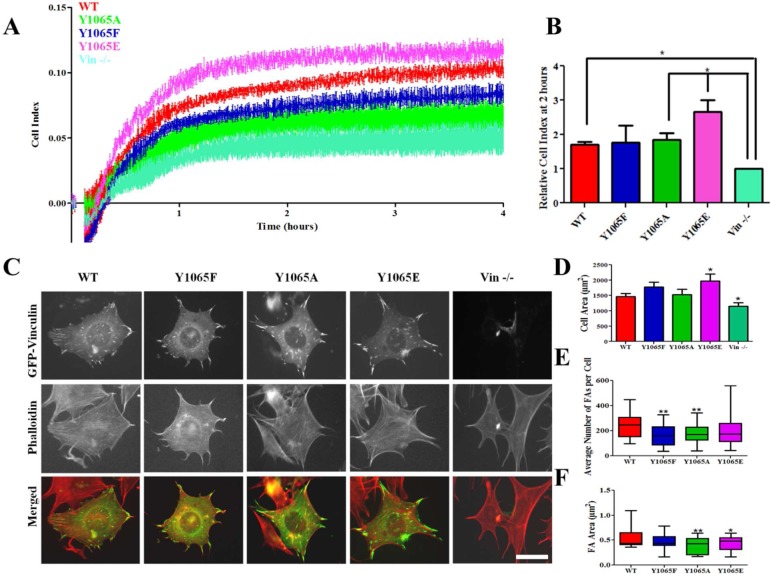

Mutation at Y1065 Affects Cell Spreading

To further probe the differences between the Y1065 variants and better understand the impact of Y1065 phosphorylation, we explored the impact of these mutants in cells, particularly during cell spreading events. When the F-actin bundling deficient mutant (ΔC5-vinculin) is expressed in cells, the cells are found to be significantly smaller with significantly fewer but slightly larger FAs.11 However, previous studies have shown that both Y1065F and Y100F mutants are required for a cell spreading defect.53 To examine cell spreading, we expressed our GFP-vinculin variants in Vin −/– MEFs, examined their expression levels by Western blot (data not shown), and monitored the cells using the real-time cell analyzer (RTCA) xCELLigence system. The RTCA system is an impedance-based method that monitors electrical impedance as cells attach and spread on the electrode (given in the arbitrary units, cell index (CI)). As previously reported, Vin −/– MEFs have difficulty in adhering to and spreading on FN, while cells expressing WT vinculin and Y1065A vinculin are well spread (Figure 4A,B).68 Cells expressing Y1065E vinculin exhibited a higher CI, indicating cells are more spread. In contrast, cells expressing Y1065F vinculin displayed lower impedance suggesting a defect in cell spreading while Y1065A vinculin expressing cells were comparable to cells expressing WT vinculin (Figure 4A,B).

Figure 4.

Vinculin variants at Y1065 localize to FAs and affect cell spreading and FAs. (A) A representative trace of cell impedance (graphed as cell index (CI)) from the RTCA xCELLigence system is taken every 15 s for 4 h; lower impedance indicates less contact with the electrode. Each data point represents an average CI of at least duplicate wells for each condition. (B) A graph showing the relative CI of cells spread on FN 2 h following plating, which corresponds to the same time as the pictures shown in (C). Data are the average ± SEM combined from three independent experiments. *p ≤ 0.05.(C) Vin–/– MEFs expressing either GFP-tagged WT-, Y1065F-, Y1065A-, or Y1065E vinculin or untransfected cells were allowed to adhere and spread on FN for 2 h. Plots of cell area (D), number of FAs per cell (E) and FA area (F) (WT n = 47; Y1065F n = 31; Y1065A n = 41; Y1065E n = 33; Vin −/– n = 35). *p-value ≤ 0.05. Error bars are ± SEM. Scale bar is 25 μm.

We also visualized cells expressing the vinculin mutants by microscopy to see if their morphology corresponds to the CI observed by RTCA. As shown in Figure 4C, cells expressing WT vinculin and the Y1065 mutants retain vinculin localization to FAs, which is not surprising since Vh is sufficient to localize vinculin to FAs.69 The cell area was quantified for Vin −/– MEFs expressing the vinculin variants and Vin −/– MEFs to examine spreading on FN. Cells expressing Y1065E vinculin are significantly larger (1971.99 μm2 ± 226.8), while Vin −/– MEFs (1156.19 μm2 ± 112.6) are significantly smaller, a finding that corresponds to our RTCA observations (Figure 4D). Quantification of FAs in cells expressing Y1065A and Y1065F vinculin revealed significantly fewer FAs (average 182.7 ± 12.62; 163.2 ± 15.31, respectively) compared to cells expressing WT vinculin (average 235.9 ± 12.83) and cells expressing Y1065A and Y1065E vinculin have significantly smaller FAs (Figure 4E,F). These results, taken together, suggest that the phosphorylation state of Y1065 and vinculin-mediated actin bundling capacity can affect cell spreading through their influence on FA number and area.

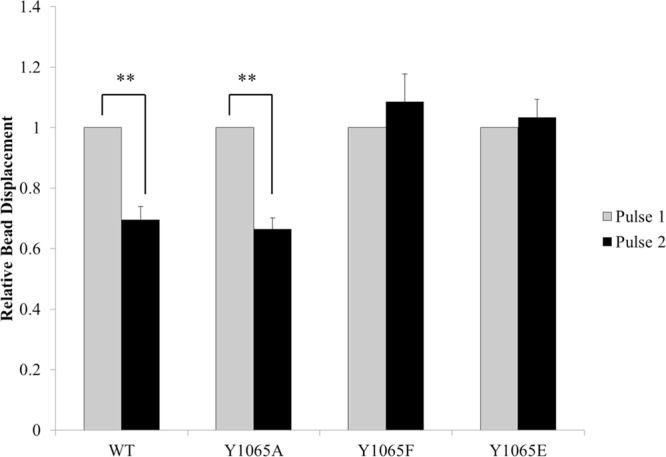

Phosphorylation State of Y1065 Regulates the Response to Mechanical Force Applied to Integrins

Vinculin plays a critical role in transducing signals that enable cellular reinforcement.19,70 We have recently shown that direct interactions between vinculin and actin are important for cells to stiffen in response to external pulses of force.11,12 Given our findings that phosphorylation at Y1065 impairs F-actin bundling in vitro, we employed three-dimensional force microscopy (3DFM) to examine cell stiffening in response to external pulses of force. For these measurements, the relative bead displacement for the first and second pulse was measured.71 Cells expressing either WT- or Y1065A vinculin showed a significant decrease in bead displacement indicative of a stiffening response (Figure 5). However, cells expressing Y1065F or Y1065E vinculin exhibited a similar bead displacement upon the second pulse, indicating a lack of a stiffening response. This result is surprising given the ability of Vt Y1065F to bundle F-actin in vitro, but it could indicate the F-actin bundles formed by vinculin need to be tightly attuned to the correct efficiency or require a specific conformation in order to transduce the signals to attain a cellular stiffening response.

Figure 5.

The phosphorylation state of Y1065 regulates the cellular stiffening response to external forces on integrins. For the relative bead displacement measurements, two pulses of force were applied to FN-coated beads bound to Vin −/– MEFs transfected with either WT vinculin (n = 17), Y1065F vinculin (n = 15), Y1065A vinculin (n = 16), or Y1065E vinculin (n = 16). **p ≤ 0.001 comparing Y1065 vinculin variants to WT vinculin. Error bars are ± SEM.

Discussion

Vinculin is an essential adaptor protein that has been implicated in a number of cellular processes including cell adhesion, spreading, regulating FA dynamics, and mediating external mechanical cues.39,72 The interaction between vinculin and F-actin is critical for vinculin to operate in FAs as indicated by mutations that selectively disrupt the ability of vinculin to bind or bundle F-actin.11,12,47,50 Here, we show that Y1065 is critical for vinculin-mediated F-actin bundle formation, which in turn is important for cells to spread and transduce forces. Furthermore, we find that phosphorylation of Vt by Src disrupts actin bundling and reduces Vh-Vt interactions. We have also characterized a series of Y1065 mutants to determine which variants best mimic phosphorylated and unphosphorylated states of vinculin. Surprisingly, while Y1065F vinculin has been previously used a nonphosphorylatable variant,52−54 Y1065A possesses properties that better mimic nonphosphorylated vinculin. While Vt Y1065A retains similar structure (Figure 2B), actin bundling (Figure 1B,C), and interactions with Vh (Figure 3A) in comparison to WT Vt, Vt Y1065F shows alterations in tryptophan packing interactions (Figure 2B), reduced affinity for Vh (Figure 3A), and significantly enhanced actin bundling relative to WT Vt and Vt Y1065A (Figure 1B,C). Additionally, our results indicate that phosphorylation or mutation to a phosphomimetic (Y1065E) impacts not only the tertiary structure (Figure 2B) and the cooperativity of unfolding in response to increasing temperature (Figure 2C,D), but it also disrupts binding to Vh (Figure 3), similar to previous observations.53 In contrast to previous studies, our results provide additional support that the C-terminal hairpin is not critical for acidic phospholipid association with Vt,55 and that Y1065 phosphorylation does not regulate the interaction between PIP2 and Vt (Figure S2, Supporting Information).64

Previous studies investigating the ability of vinculin to bundle actin have used large, destabilizing deletions.35,73,74 For instance, while removal of the Vt C-terminus (residues 1052–1066) showed an enhanced actin bundling efficiency,46 it has been previously shown that this deletion alters the structural integrity of Vt.55 We have previously shown that deletion of Y1065 and Q1066 from the C-terminal hairpin retains Vt structure, actin, and phospholipid binding, but greatly impairs actin bundling.11,50 Hence, our finding that phosphorylation or certain mutations at Y1065 also impair actin bundling is not surprising given the importance of the C-terminal hairpin in actin-induced Vt self-association;11 however, we were surprised by the varying degrees of bundling efficiency exhibited by the different Y1065 mutations (Figure 1B,C; Figure S4A and B; Table S1). While the results from the head–tail pulldowns found that Y1065F, pY-Vt, and Y1065E were unable to bind to GST-Vh in the Vh-Vt pulldowns with the same efficiency as WT Vt and Y1065A, actin cosedimentation assays with full-length vinculin showed that the Y1065 mutants were unable to bind F-actin unless the activating IpaA peptide was present (Figure 3B). These results suggest that the head–tail interaction defects exhibited by Y1065F and Y1065E are not drastic enough to ablate head–tail intramolecular interactions in the context of the full-length protein. Other factors may contribute to priming the molecule to adopt an open conformation such as phosphorylation of additional tyrosine residues (Y100) and PKC-mediated phosphorylation of serine residues (S1033 or S1045).42,53,75 The differences observed between Vh-Vt pulldowns and actin cosedimentations with full-length vinculin observed in vitro could be attributed to an avidity effect of having Vt tethered to Vh by the proline-rich linker. Recent studies have employed a vinculin activation biosensor to monitor the recruitment of either Y1065F or Y1065E to the membrane in smooth muscle cells. Results from these analyses have shown that Y1065F is defective in recruitment and hence activation.76 However, further studies are required to examine how these mutations modulate the active conformation of vinculin in FAs. Overall, these data indicate that Src phosphorylation at Y1065 provides a mechanism for regulating vinculin-driven F-actin bundle formation in cells. Moreover, our characterization of the Y1065 mutants indicate that Y1065A, rather than Y1065F, is a better nonphosphorylatable variant whereas Y1065E mimics phosphorylated vinculin.

As demonstrated in Figure 4, cells expressing vinculin variants are affected by the phosphorylation state at Y1065, as indicated by their ability to spread on FN. The RTCA and quantification of cell area data indicate that cells expressing WT-, Y1065F-, and Y1065A vinculin behave similarly with respect to cell spreading. These results are similar to previous studies that have examined Y1065F.53 In contrast, cells expressing Y1065E, the phosphomimetic vinculin construct, develop a larger area. Taken together with previous studies that examined actin binding and bundling on cell spreading,11,12 it is likely that vinculin-driven F-actin bundling does not play a direct role in dictating cell area during spreading events since the actin bundling-deficient variant, Y1065E vinculin, exhibits a significant increase in the cell area. Rather, the phosphorylation state of Y1065 is the main contributing factor that affects cell spreading events which is likely attributed to interactions with an unidentified binding partner. Additionally, we find that cells expressing Y1065A and Y1065F vinculin mutants display significantly fewer FAs, and that Y1065A and Y1065E vinculin-expressing cells have significantly smaller FAs.

As shown previously, vinculin is a crucial component for efficiently transducing forces, whether they are external forces being applied or internally generated forces. These forces are generated through vinculin interactions with F-actin.77−79 Preventing vinculin binding to or bundling F-actin prevents cellular reinforcement when external pulses of force are applied to integrins.11,12 We observed that when Y1065 is mutated, cells expressing Y1065A vinculin are able to display a decrease in bead displacement with subsequent pulses of force, thereby indicating a stiffening response (Figure 5). However, cells expressing Y1065F and Y1065E vinculin are unable to stiffen upon applications of force to integrins (Figure 5). This observation is not unexpected for Y1065E given its bundling defect in vitro. However, we were surprised with the lack of stiffening response displayed by cells expressing Y1065F, given the “superbundling” phenotype displayed by this variant in vitro. These results suggest that the bundling efficiency displayed by vinculin needs to be tightly controlled in order to attain efficient cellular reinforcement or Y1065 is responsible for mediating additional functions. Whether it is through association of an unknown binding partner that regulates these events via the C-terminal hairpin or the actin-induced vinculin dimer, the contribution to cell spreading and cellular reinforcement appears to be phosphorylation dependent. While detection of this binding partner is beyond the scope of this work, future efforts will be directed toward the identification of the binding partner and elucidating its interaction interface.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Li Zhou for performing the mass spectrometry analysis on phosphorylated Vt. We thank Dr. Greg Young, the NMR facility manager at University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill, for assistance in NMR data collection, and Dr. Ashutosh Tripathy, Director of the UNC Macromolecular Interactions Facility, for assistance in the acquisition of CD spectra. We thank Dr. Min-Qi Lu for the preparation of monomeric actin.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- 3DFM

three dimensional force microscopy

- BME

β-mercaptoethanol

- CD

circular dichroism

- DMEM

Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium

- DTT

dithiothreitol

- fQCR

fast quantitative cysteine reactivity

- FAs

focal adhesions

- F-actin

filamentous actin

- FN

fibronectin

- G-actin

monomeric actin

- KO

knockout

- MEFs

murine embryo fibroblasts

- PBS

phosphate buffered saline

- PIP2

phosphatidylinositol (4,5)-bisphosphate

- SEM

standard error of the mean

- RTCA

real-time cell analyzer

- Vh

vinculin head, residues 1–855

- Vin −/–

vinculin knockout cells

- Vt

vinculin tail, residues 879–1066

Supporting Information Available

Summary of actin binding and bundling for additional Vt Y1065 variants (Table S1) and mass spectrometry confirmation of percent phosphorylation of Vt (Figure S1). Data also include PIP2 cosedimentation results comparing the variants (Figure S2), results of HSQC spectra comparing the variants (Figure S3), and actin bundling results with full-length vinculin mutants in the presence of IpaA (Figure S4). This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

Author Present Address

¶ (C.E.T.) Cell Motility Laboratory, Cancer Research UK, London Research Institute, 44 Lincoln’s Inn Fields, London WC2A 3LY, UK.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Funding Statement

National Institutes of Health, United States

Supplementary Material

References

- Hynes R. O. (2002) Integrins: bidirectional, allosteric signaling machines. Cell 110, 673–687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Critchley D. R. (2000) Focal adhesions - the cytoskeletal connection. Curr. Opin Cell Biol. 12, 133–139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ridley A. J.; Schwartz M. A.; Burridge K.; Firtel R. A.; Ginsberg M. H.; Borisy G.; Parsons J. T.; Horwitz A. R. (2003) Cell migration: integrating signals from front to back. Science 302, 1704–1709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang N.; Butler J. P.; Ingber D. E. (1993) Mechanotransduction across the cell surface and through the cytoskeleton. Science 260, 1124–1127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matthews B. D.; Overby D. R.; Mannix R.; Ingber D. E. (2006) Cellular adaptation to mechanical stress: role of integrins, Rho, cytoskeletal tension and mechanosensitive ion channels. J. Cell Sci. 119, 508–518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guilluy C.; Swaminathan V.; Garcia-Mata R.; O’Brien E. T.; Superfine R.; Burridge K. (2011) The Rho GEFs LARG and GEF-H1 regulate the mechanical response to force on integrins. Nat. Cell Biol. 13, 722–727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lessey E. C.; Guilluy C.; Burridge K. (2012) From Mechanical Force to RhoA Activation. Biochemistry 51, 7420–7432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balaban N. Q.; Schwarz U. S.; Riveline D.; Goichberg P.; Tzur G.; Sabanay I.; Mahalu D.; Safran S.; Bershadsky A.; Addadi L.; Geiger B. (2001) Force and focal adhesion assembly: a close relationship studied using elastic micropatterned substrates. Nat. Cell Biol. 3, 466–472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alenghat F. J.; Fabry B.; Tsai K. Y.; Goldmann W. H.; Ingber D. E. (2000) Analysis of cell mechanics in single vinculin-deficient cells using a magnetic tweezer. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 277, 93–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mierke C. T.; Kollmannsberger P.; Zitterbart D. P.; Smith J.; Fabry B.; Goldmann W. H. (2008) Mechano-coupling and regulation of contractility by the vinculin tail domain. Biophys. J. 94, 661–670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen K.; Tolbert C. E.; Guilluy C.; Swaminathan V. S.; Berginski M. E.; Burridge K.; Superfine R.; Campbell S. L. (2011) The vinculin C-terminal hairpin mediates F-actin bundle formation, focal adhesion, and cell mechanical properties. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 45103–45115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson P. M.; Tolbert C. E.; Shen K.; Kota P.; Palmer S. M.; Plevock K. M.; Orlova A.; Galkin V. E.; Burridge K.; Egelman E. H.; Dokholyan N. V.; Superfine R.; Campbell S. L. (2014) Identification of an actin binding surface on vinculin that mediates mechanical cell and focal adhesion properties. Structure 22, 697–706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geiger B.; Bershadsky A.; Pankov R.; Yamada K. M. (2001) Transmembrane crosstalk between the extracellular matrix--cytoskeleton crosstalk. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2, 793–805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geiger B.; Spatz J. P.; Bershadsky A. D. (2009) Environmental sensing through focal adhesions. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 10, 21–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu W.; Baribault H.; Adamson E. D. (1998) Vinculin knockout results in heart and brain defects during embryonic development. Development 125, 327–337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Subauste M. C.; Pertz O.; Adamson E. D.; Turner C. E.; Junger S.; Hahn K. M. (2004) Vinculin modulation of paxillin-FAK interactions regulates ERK to control survival and motility. J. Cell Biol. 165, 371–381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saunders R. M.; Holt M. R.; Jennings L.; Sutton D. H.; Barsukov I. L.; Bobkov A.; Liddington R. C.; Adamson E. A.; Dunn G. A.; Critchley D. R. (2006) Role of vinculin in regulating focal adhesion turnover. Eur. J. Cell Biol. 85, 487–500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boschek C. B.; Jockusch B. M.; Friis R. R.; Back R.; Grundmann E.; Bauer H. (1981) Early changes in the distribution and organization of microfilament proteins during cell transformation. Cell 24, 175–184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grashoff C.; Hoffman B. D.; Brenner M. D.; Zhou R.; Parsons M.; Yang M. T.; McLean M. A.; Sligar S. G.; Chen C. S.; Ha T.; Schwartz M. A. (2010) Measuring mechanical tension across vinculin reveals regulation of focal adhesion dynamics. Nature 466, 263–266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hazan R. B.; Kang L.; Roe S.; Borgen P. I.; Rimm D. L. (1997) Vinculin is associated with the E-cadherin adhesion complex. J. Biol. Chem. 272, 32448–32453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watabe-Uchida M.; Uchida N.; Imamura Y.; Nagafuchi A.; Fujimoto K.; Uemura T.; Vermeulen S.; van Roy F.; Adamson E. D.; Takeichi M. (1998) alpha-Catenin-vinculin interaction functions to organize the apical junctional complex in epithelial cells. J. Cell Biol. 142, 847–857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wachsstock D. H.; Wilkins J. A.; Lin S. (1987) Specific interaction of vinculin with alpha-actinin. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 146, 554–560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gingras A. R.; Ziegler W. H.; Frank R.; Barsukov I. L.; Roberts G. C.; Critchley D. R.; Emsley J. (2005) Mapping and consensus sequence identification for multiple vinculin binding sites within the talin rod. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 37217–37224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tran Van Nhieu G.; Ben-Ze’ev A.; Sansonetti P. J. (1997) Modulation of bacterial entry into epithelial cells by association between vinculin and the Shigella IpaA invasin. EMBO J. 16, 2717–2729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holle A. W.; Tang X.; Vijayraghavan D.; Vincent L. G.; Fuhrmann A.; Choi Y. S.; del Alamo J. C.; Engler A. J. (2013) In situ mechanotransduction via vinculin regulates stem cell differentiation. Stem Cells. 31, 2467–2477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandai K.; Nakanishi H.; Satoh A.; Takahashi K.; Satoh K.; Nishioka H.; Mizoguchi A.; Takai Y. (1999) Ponsin/SH3P12: an l-afadin- and vinculin-binding protein localized at cell-cell and cell-matrix adherens junctions. J. Cell Biol. 144, 1001–1017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kioka N.; Sakata S.; Kawauchi T.; Amachi T.; Akiyama S. K.; Okazaki K.; Yaen C.; Yamada K. M.; Aota S. (1999) Vinexin: a novel vinculin-binding protein with multiple SH3 domains enhances actin cytoskeletal organization. J. Cell Biol. 144, 59–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawabe H.; Hata Y.; Takeuchi M.; Ide N.; Mizoguchi A.; Takai Y. (1999) nArgBP2, a novel neural member of ponsin/ArgBP2/vinexin family that interacts with synapse-associated protein 90/postsynaptic density-95-associated protein (SAPAP). J. Biol. Chem. 274, 30914–30918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brindle N. P.; Holt M. R.; Davies J. E.; Price C. J.; Critchley D. R. (1996) The focal-adhesion vasodilator-stimulated phosphoprotein (VASP) binds to the proline-rich domain in vinculin. Biochem. J. 318(Pt 3), 753–757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeMali K. A.; Barlow C. A.; Burridge K. (2002) Recruitment of the Arp2/3 complex to vinculin: coupling membrane protrusion to matrix adhesion. J. Cell Biol. 159, 881–891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janostiak R.; Brabek J.; Auernheimer V.; Tatarova Z.; Lautscham L. A.; Dey T.; Gemperle J.; Merkel R.; Goldmann W. H.; Fabry B.; Rosel D. (2014) CAS directly interacts with vinculin to control mechanosensing and focal adhesion dynamics. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 71, 727–744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood C. K.; Turner C. E.; Jackson P.; Critchley D. R. (1994) Characterisation of the paxillin-binding site and the C-terminal focal adhesion targeting sequence in vinculin. J. Cell Sci. 107(Pt 2), 709–717. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ziegler W. H.; Tigges U.; Zieseniss A.; Jockusch B. M. (2002) A lipid-regulated docking site on vinculin for protein kinase C. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 7396–7404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huttelmaier S.; Illenberger S.; Grosheva I.; Rudiger M.; Singer R. H.; Jockusch B. M. (2001) Raver1, a dual compartment protein, is a ligand for PTB/hnRNPI and microfilament attachment proteins. J. Cell Biol. 155, 775–786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huttelmaier S.; Bubeck P.; Rudiger M.; Jockusch B. M. (1997) Characterization of two F-actin-binding and oligomerization sites in the cell-contact protein vinculin. Eur. J. Biochem. 247, 1136–1142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson R. P.; Niggli V.; Durrer P.; Craig S. W. (1998) A conserved motif in the tail domain of vinculin mediates association with and insertion into acidic phospholipid bilayers. Biochemistry 37, 10211–10222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellin R. M.; Huiatt T. W.; Critchley D. R.; Robson R. M. (2001) Synemin may function to directly link muscle cell intermediate filaments to both myofibrillar Z-lines and costameres. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 32330–32337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ziegler W. H.; Liddington R. C.; Critchley D. R. (2006) The structure and regulation of vinculin. Trends Cell Biol. 16, 453–460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carisey A.; Ballestrem C. (2011) Vinculin, an adapter protein in control of cell adhesion signalling. Eur. J. Cell Biol. 90, 157–163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bakolitsa C.; de Pereda J. M.; Bagshaw C. R.; Critchley D. R.; Liddington R. C. (1999) Crystal structure of the vinculin tail suggests a pathway for activation. Cell 99, 603–613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bakolitsa C.; Cohen D. M.; Bankston L. A.; Bobkov A. A.; Cadwell G. W.; Jennings L.; Critchley D. R.; Craig S. W.; Liddington R. C. (2004) Structural basis for vinculin activation at sites of cell adhesion. Nature 430, 583–586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golji J.; Mofrad M. R. (2010) A molecular dynamics investigation of vinculin activation. Biophys. J. 99, 1073–1081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen H.; Choudhury D. M.; Craig S. W. (2006) Coincidence of actin filaments and talin is required to activate vinculin. J. Biol. Chem. 281, 40389–40398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson R. P.; Craig S. W. (1994) An intramolecular association between the head and tail domains of vinculin modulates talin binding. J. Biol. Chem. 269, 12611–12619. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson R. P.; Craig S. W. (1995) F-actin binding site masked by the intramolecular association of vinculin head and tail domains. Nature 373, 261–264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janssen M. E.; Kim E.; Liu H.; Fujimoto L. M.; Bobkov A.; Volkmann N.; Hanein D. (2006) Three-dimensional structure of vinculin bound to actin filaments. Mol. Cell 21, 271–281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thievessen I.; Thompson P. M.; Berlemont S.; Plevock K. M.; Plotnikov S. V.; Zemljic-Harpf A.; Ross R. S.; Davidson M. W.; Danuser G.; Campbell S. L.; Waterman C. M. (2013) Vinculin-actin interaction couples actin retrograde flow to focal adhesions, but is dispensable for focal adhesion growth. J. Cell Biol. 202, 163–177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson P. M.; Tolbert C. E.; Shen K.; Kota P.; Palmer S. M.; Plevock K. M.; Orlova A.; Galkin V. E.; Burridge K.; Egelman E. H.; Dokholyan N. V.; Superfine R.; Campbell S. L. (2014) Identification of an Actin Binding Surface on Vinculin that Mediates Mechanical Cell and Focal Adhesion Properties. Structure 22, 697–706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golji J.; Mofrad M. R. (2013) The interaction of vinculin with actin. PLoS Comput. Biol. 9, e1002995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tolbert C. E.; Burridge K.; Campbell S. L. (2013) Vinculin regulation of F-actin bundle formation: what does it mean for the cell?. Cell Adh. Migr. 7, 219–225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sefton B. M.; Hunter T.; Ball E. H.; Singer S. J. (1981) Vinculin: a cytoskeletal target of the transforming protein of Rous sarcoma virus. Cell 24, 165–174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kupper K.; Lang N.; Mohl C.; Kirchgessner N.; Born S.; Goldmann W. H.; Merkel R.; Hoffmann B. (2010) Tyrosine phosphorylation of vinculin at position 1065 modifies focal adhesion dynamics and cell tractions. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 399, 560–564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Z.; Izaguirre G.; Lin S. Y.; Lee H. Y.; Schaefer E.; Haimovich B. (2004) The phosphorylation of vinculin on tyrosine residues 100 and 1065, mediated by SRC kinases, affects cell spreading. Mol. Biol. Cell 15, 4234–4247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moese S.; Selbach M.; Brinkmann V.; Karlas A.; Haimovich B.; Backert S.; Meyer T. F. (2007) The Helicobacter pylori CagA protein disrupts matrix adhesion of gastric epithelial cells by dephosphorylation of vinculin. Cell Microbiol. 9, 1148–1161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmer S. M.; Playford M. P.; Craig S. W.; Schaller M. D.; Campbell S. L. (2009) Lipid binding to the tail domain of vinculin: specificity and the role of the N and C termini. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 7223–7231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levy Y.; Arbel-Goren R.; Hadari Y. R.; Eshhar S.; Ronen D.; Elhanany E.; Geiger B.; Zick Y. (2001) Galectin-8 functions as a matricellular modulator of cell adhesion. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 31285–31295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weekes J.; Barry S. T.; Critchley D. R. (1996) Acidic phospholipids inhibit the intramolecular association between the N- and C-terminal regions of vinculin, exposing actin-binding and protein kinase C phosphorylation sites. Biochem. J. 314(Pt 3), 827–832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abramoff M. D.; Magalhaes P. J.; Ram S. J. (2004) Image Processing with ImageJ. Biophotonics International 11, 36–42. [Google Scholar]

- Dixon R. D.; Arneman D. K.; Rachlin A. S.; Sundaresan N. R.; Costello M. J.; Campbell S. L.; Otey C. A. (2008) Palladin is an actin cross-linking protein that uses immunoglobulin-like domains to bind filamentous actin. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 6222–6231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isom D. G.; Marguet P. R.; Oas T. G.; Hellinga H. W. (2011) A miniaturized technique for assessing protein thermodynamics and function using fast determination of quantitative cysteine reactivity. Proteins 79, 1034–1047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delaglio F.; Grzesiek S.; Vuister G. W.; Zhu G.; Pfeifer J.; Bax A. (1995) NMRPipe: a multidimensional spectral processing system based on UNIX pipes. J. Biomol NMR 6, 277–293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson B. A.; Blevins R. A. (1994) Nmr View - a Computer-Program for the Visualization and Analysis of Nmr Data. J. Biomol NMR 4, 603–614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diez G.; Kollmannsberger P.; Mierke C. T.; Koch T. M.; Vali H.; Fabry B.; Goldmann W. H. (2009) Anchorage of vinculin to lipid membranes influences cell mechanical properties. Biophys. J. 97, 3105–3112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wirth V. F.; List F.; Diez G.; Goldmann W. H. (2010) Vinculin’s C-terminal region facilitates phospholipid membrane insertion. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 398, 433–437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borgon R. A.; Vonrhein C.; Bricogne G.; Bois P. R.; Izard T. (2004) Crystal structure of human vinculin. Structure 12, 1189–1197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen D. M.; Chen H.; Johnson R. P.; Choudhury B.; Craig S. W. (2005) Two distinct head-tail interfaces cooperate to suppress activation of vinculin by talin. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 17109–17117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Izard T.; Tran Van Nhieu G.; Bois P. R. (2006) Shigella applies molecular mimicry to subvert vinculin and invade host cells. J. Cell Biol. 175, 465–475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu W.; Coll J. L.; Adamson E. D. (1998) Rescue of the mutant phenotype by reexpression of full-length vinculin in null F9 cells; effects on cell locomotion by domain deleted vinculin. J. Cell Sci. 111(Pt 11), 1535–1544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Humphries J. D.; Wang P.; Streuli C.; Geiger B.; Humphries M. J.; Ballestrem C. (2007) Vinculin controls focal adhesion formation by direct interactions with talin and actin. J. Cell Biol. 179, 1043–1057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ji L.; Lim J.; Danuser G. (2008) Fluctuations of intracellular forces during cell protrusion. Nat. Cell Biol. 10, 1393–1400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Brien E. T.; Cribb J.; Marshburn D.; Taylor R. M.; Superfine R. (2008) Magnetic Manipulation for Force Measurements in Cell Biology. Method Cell Biol. 89, 433–+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng X.; Nelson E. S.; Maiers J. L.; DeMali K. A. (2011) New insights into vinculin function and regulation. Int. Rev. Cell Mol. Biol. 287, 191–231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson R. P.; Craig S. W. (2000) Actin activates a cryptic dimerization potential of the vinculin tail domain. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 95–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menkel A. R.; Kroemker M.; Bubeck P.; Ronsiek M.; Nikolai G.; Jockusch B. M. (1994) Characterization of an F-actin-binding domain in the cytoskeletal protein vinculin. J. Cell Biol. 126, 1231–1240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golji J.; Wendorff T.; Mofrad M. R. (2012) Phosphorylation primes vinculin for activation. Biophys. J. 102, 2022–2030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Y.; Day R. N.; Gunst S. J. (2013) Vinculin Phosphorylation at Tyr 1065 Regulates Vinculin Conformation and Tension Development in Airway Smooth Muscle Tissues. J. Biol. Chem. 289, 3677–3688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pasapera A. M.; Schneider I. C.; Rericha E.; Schlaepfer D. D.; Waterman C. M. (2010) Myosin II activity regulates vinculin recruitment to focal adhesions through FAK-mediated paxillin phosphorylation. J. Cell Biol. 188, 877–890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galbraith C. G.; Yamada K. M.; Sheetz M. P. (2002) The relationship between force and focal complex development. J. Cell Biol. 159, 695–705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz M. A. (2009) Cell biology. The force is with us. Science 323, 588–589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.