Jung et al. (1) claim to show that “feminine-named hurricanes cause significantly more deaths than do masculine-named hurricanes” (p. 1). This conclusion is mainly obtained by analyzing data on fatalities caused by hurricanes in the United States (1950–2012). By reanalyzing the same data, we show that the conclusion is based on biased presentation and invalid statistics.

The reasoning in ref. 1 is fundamentally based on the regression models reported in their table S2, in particular, model 4. However, due to the interaction terms combined with extreme values and weak significance, the analysis is based on a very fragile model; e.g., the model predicts almost 20,000 deaths for hurricane Sandy, which actually caused 159 fatalities. Their figure 1 and the discussion on p. 5, first paragraph, are not based on model 4, but on a model using normalized damage factors in two categories. For this model, for which only β-coefficients are reported, we want to remark that neither the masculinity-femininity index (MFI) variable nor the interaction terms are significant, and the one for low normalized damage and MFI is only weakly significant (P = 0.07). (We want to remark that in the paper, the parameter β3 is reported with a wrong sign, and therefore the prediction results are also not correct, although the impact is not too significant.)

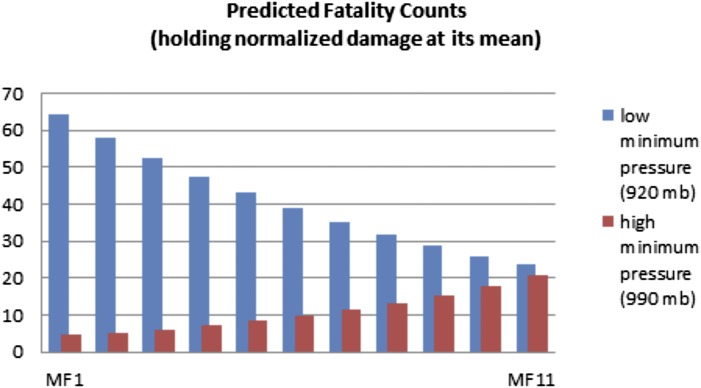

Fig. 1.

Predicted fatality counts. Hurricanes with low MFI (vs. high MFI) are masculine-named (vs. feminine-named). Predicted counts of deaths were estimated separately for each value of MFI of hurricanes, holding the normalized damage at its mean.

Now, we explain our claim that the results are presented in a biased way. By holding the minimum pressure at its mean in prediction of counts of deaths, the authors only report the influence of MFI and normalized damage (figure 1 in ref. 1). This ignores the influence of the second interaction term MFI minimum pressure, which shows an opposite influence (see the estimated parameters on p. 5, first paragraph). By considering the counts of deaths under constant normalized damage, the results are contrary: male-named hurricanes with a low minimum pressure (strong hurricanes) are associated with more deaths than female ones (Fig. 1).

In the light of an alternating male-female naming system started in 1979, the authors claim that similar results can be obtained by only considering the data after 1979 (model 4; P = 0.073). However, when reanalyzing the model described on p. 5 for these years, no effect can be observed at all: neither MFI nor the interaction terms are significant on a 10% level. The results show nearly no effect for hurricanes names. The same holds when using all years, but excluding the extreme values for the four hurricanes ≥100 deaths (three before 1979, thus automatically female named; Table 1). A Mann–Whitney test shows for both subsamples—and also for the whole sample—no significant differences between male- or female-named hurricanes for deaths, minimum pressure, category, and damages.

Table 1.

Predicted fatality counts for alternative data selections

| Data ≥ 1979 | Holding minimum pressure at its mean | |||

| High normalized damage | Low normalized damage | |||

| MF1 | MF11 | MF1 | MF11 | |

| 10.1 | 22.4 | 9.6 | 8.5 | |

| Holding normalized damage at its mean | ||||

| Low minimum pressure (920 mb) | High minimum pressure (990 mb) | |||

| MF1 | MF11 | MF1 | MF11 | |

| 92.3 | 66.1 | 2.8 | 5.7 | |

| Deaths ≤ 100 | Holding minimum pressure at its mean | |||

| High normalized damage | Low normalized damage | |||

| MF1 | MF11 | MF1 | MF11 | |

| 12.5 | 13.8 | 8.9 | 7.1 | |

| Holding normalized damage at its mean | ||||

| Low minimum pressure (920 mb) | High minimum pressure (990 mb) | |||

| MF1 | MF11 | MF1 | MF11 | |

| 77.7 | 73.6 | 3.4 | 3.2 | |

To conclude, the analyses given in ref. 1 are examples of the fact that prediction models using interaction terms have to be handled and interpreted carefully; in particular, using insignificant variables is not expedient and may lead to statistical artifacts.

To summarize, the data do not contain evidence that feminine-named hurricanes cause more deaths than masculine-named hurricanes.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Jung K, Shavitt S, Viswanathan M, Hilbe JM. Female hurricanes are deadlier than male hurricanes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014;111(24):8782–8787. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1402786111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]