Abstract

Wildlife consumption can be viewed as an ecosystem provisioning service (the production of a material good through ecological functioning) because of wildlife’s ability to persist under sustainable levels of harvest. We used the case of wildlife harvest and consumption in northeastern Madagascar to identify the distribution of these services to local households and communities to further our understanding of local reliance on natural resources. We inferred these benefits from demand curves built with data on wildlife sales transactions. On average, the value of wildlife provisioning represented 57% of annual household cash income in local communities from the Makira Natural Park and Masoala National Park, and harvested areas produced an economic return of U.S.$0.42 ha−1 · year−1. Variability in value of harvested wildlife was high among communities and households with an approximate 2 orders of magnitude difference in the proportional value of wildlife to household income. The imputed price of harvested wildlife and its consumption were strongly associated (p< 0.001), and increases in price led to reduced harvest for consumption. Heightened monitoring and enforcement of hunting could increase the costs of harvesting and thus elevate the price and reduce consumption of wildlife. Increased enforcement would therefore be beneficial to biodiversity conservation but could limit local people’s food supply. Specifically, our results provide an estimate of the cost of offsetting economic losses to local populations from the enforcement of conservation policies. By explicitly estimating the welfare effects of consumed wildlife, our results may inform targeted interventions by public health and development specialists as they allocate sparse funds to support regions, households, or individuals most vulnerable to changes in access to wildlife.

Keywords: bushmeat, demand curve, development targeting, ecosystem services, hunting, microeconomics, protected areas, wildlife conservation

Introduction

Quantifying the services provided to humans by ecosystems has become a major area of research within ecology, economics, and conservation biology (Costanza et al. 1997; Pagiola et al. 2004). One of the primary uses for quantifying ecosystem services is to determine the economic effects of land management and how the benefits and costs of management are distributed among stakeholders (Kremen et al. 2000; Pagiola et al. 2004; Farley & Costanza 2010). Through fine-scale analyses of the distribution of costs and benefits to local users, one can better understand the incentives for conservation and rule-breaking behavior and determine potential interventions through payment for ecosystem services. Ecosystem services may disproportionately benefit certain user groups; thus, land-use changes may unequally affect different groups of people (Newton et al. 2012). By modeling the effects of a given policy on categories of local users, ecosystem-service analyses can be used to mitigate the effects of restricted access to ecosystem services.

The widespread harvest of wildlife for human consumption is a major ecosystem service (MEA 2005) that provides benefits to tens of millions of rural poor (Bodmer et al. 1994; Milner-Gulland et al. 2003; Balmford et al. 2011). In areas of Africa, where the majority of harvested wildlife is sold (e.g., de Merode et al. 2004), studies of the value of harvested wildlife commonly entail analysis of commercial markets rather than nonmarket valuation techniques (e.g., Steel 1994; Refisch & Kone 2005). Researchers have also used market reports to determine the national or regional value of wildlife harvested each year (e.g., Godoy et al. 2000; Chapman & Peres 2001). Neither approach accounts for the large fraction of locally consumed wildlife that is not part of cash or noncash markets (Robinson & Bennett 2000; Brashares et al. 2011). Thus, market-based studies of harvested wildlife evaluate only part of the amount extracted and ignore often large subsistence values.

As in many developing countries, wildlife in Madagascar is a major nutritional resource and contributes substantially to the welfare and livelihoods of rural communities (Golden 2009; Golden et al. 2011). Yet, because there is often no formal commercial market for this commodity, its monetary value and its contributions to ecosystem services are often overlooked. In addition to its value as a food source (provisioning service), mammalian wildlife in Madagascar also provide regulatory, cultural, and supporting services (MEA 2005). For example, frugivorous and nectarivorous bat and lemur species regulate forest floral diversity through their role as seed dispersers and pollinators (Dew & Wright 1998). Many of the insectivorous bat and carnivorous species also are natural predators of insects, snakes, and rodents that affect local agriculture and livestock. Mammalian wildlife also attract tourists, a major industry in Madagascar (Ormsby & Mannle 2006).

Consumption of wildlife has direct nutritional benefits (Golden et al. 2011). Certain households would likely consume wildlife even if no health benefit existed because harvesting wildlife with minimal effort is less expensive than domesticated meat consumption. More accurate assessments of the monetary value of wildlife provisioning are needed because not all value is subsumed under the already calculated health value (Golden et al. 2011) and the costs to humans of a loss of access to wildlife are unknown.

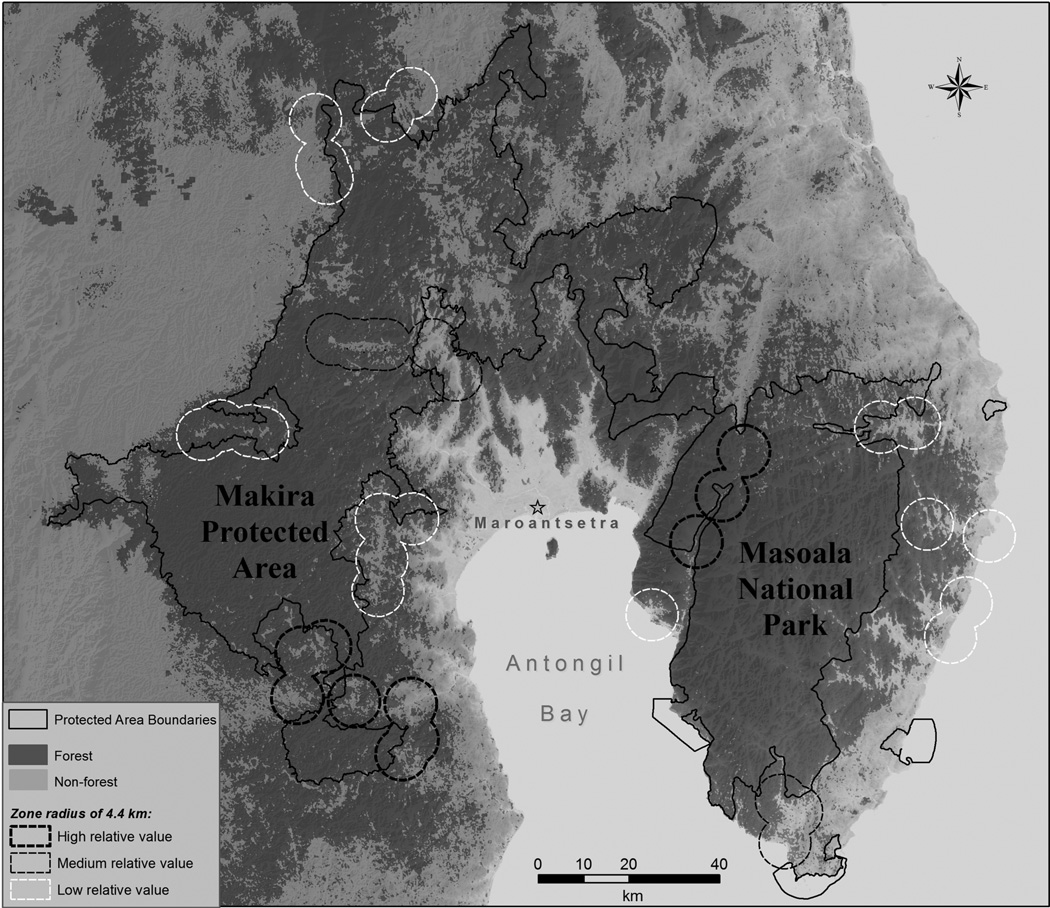

Working around 2 protected areas in northeastern Madagascar (Fig. 1), we estimated the total (market and nonmarket) subsistence value (a value in direct conflict with conservationist’s conception of its existence value) of wildlife for residents for 2 primary reasons: to create broad regional eligibility criteria to target and allocate development and public health support toward communities most at risk of losing access to ecosystem services from changes in land use (including conservation) and to calculate a value of wildlife provisioning per individual household’s cash revenue (in the style of payment for ecosystem services [Newton et al. 2012]) to ensure equity in deliveries. Unsustainable hunting could lead to current or future loss of access and thus reduce the option value or bequest value of wildlife (Pagiola et al. 2004). With this knowledge, people most vulnerable to changes in access to wildlife could be supported prior to anticipated changes in nutrition and livelihoods.

Figure 1.

Makira Natural Park and Masoala National Park and hunting harvest areas (dashed lines, mean harvest area [radius 4.4 km] surrounding a community [Golden 2009]; low, <$0.20 ha1·year1; medium, $0.20–0.75 ha1·year1; high, >$0.75 ha1·year1). Only communities within the study are shown. Relative values were calculated from natural breaks in the variable describing the value of subsistence wildlife harvest within each of the harvest areas shown.

Methods

Study Site and Subjects

We studied communities adjacent to Makira Natural Park and Masoala National Park in northeastern Madagascar (Fig. 1). The Makira Natural Park (henceforth Makira) covers approximately 370,000 ha and is characterized by lowland and midelevation rainforest (Golden 2009). Masoala National Park (henceforth Masoala) is a littoral and lowland rainforest covering approximately 210,000 ha (Kremen et al. 1999). These parks are among the nation’s largest remaining blocks of contiguous forest and contain high levels of biodiversity (Goodman & Benstead 2005; Kremen et al. 2008; Golden 2009). The 2 primary ethnic groups in Makira are the Betsimisaraka in the east and south (45.2% of the population) and the Tsimihety in the north and west (50.0% of the population) (Golden 2009). In Masoala, the sampled human population was almost entirely Betsimisaraka (94.7%). To estimate annual household consumption rates of bushmeat, we surveyed 417 households in 26 villages that bordered Makira and 224 households in 13 villages that bordered Masoala (Golden et al. 2013) (see Supporting Information for details of survey methods).

Harvested Wildlife Prices

Building from previous work that estimated wildlife value from livestock meat prices, urban bushmeat market prices, or a flat rate for all wildlife (e.g., Bodmer et al. 1994; Naidoo & Ricketts 2006), we identified local prices specific to each harvested species and location to estimate the total value of harvested wildlife. Although there were no reports of formal commercial markets for harvested wildlife in Madagascar (most mammal species were illegal to hunt), animal carcasses were occasionally sold household to household, making it possible to develop an index for a local pricing structure. Because price information was collected locally in each village, these prices were not skewed by long-distance transportation costs to urban markets or use of brokers. Local consumer prices of wildlife were reported and recorded during household interviews when interviewees had purchased rather than hunted individual animals (Table 1).

Table 1.

Price structure of household-to-household wildlife sales in Makira, Madagascar.

| Species | Mean price in USD /kg*(n) |

|---|---|

| Lemurs | |

| Avahi laniger, eastern wooly lemur |

1.04–1.89 (6) |

| Cheirogaleus sp., dwarf lemur sp. |

1.21–3.82 (5) |

| Daubentonia madagascariensis aye-aye |

0.94–0.98 (1) |

| Eulemur albifrons white-fronted brown lemur |

0.85–1.10 (68) |

| Eulemur rubriventer red-bellied lemur |

0.91–1.36 (11) |

| Hapalemur griseus, eastern bamboo lemur |

1.03–1.44 (11) |

| Indri indri, indri | 0.48–0.70 (4) |

| Lepilemur seali, Seal’s sportive lemur |

1.23–1.84 (1) |

| Microcebus sp., mouse lemur sp. |

5.88 (1) |

| Propithecus candidus, silky sifaka |

0.45–0.59 (3) |

| Varecia sp., ruffed lemur sp. | 0.68–1.08 (12) |

| Carnivores | |

| Cryptoprocta ferox, fosa | 0.39–0.78 (5) |

| Eupleres goudotii, falanouc | 0.59–1.06 (3) |

| Fossa fossana, fanaloka | 0.31–0.59 (1) |

| Galidia elegans, ringtailed mongoose |

0.72–1.02 (2) |

| Viverricula indica, lesser Indian civet |

0.33–0.66 (6) |

| Bats | |

| Pteropus rufus, Madagascar flying fox |

1.23–1.85 (15) |

| Rousettus madagascariensis Madagascar rousette |

0.44–1.76 (29) |

| Insectivorous bats spp. | 4.20–9.80 (1) |

| Tenrecs and bush pigs | |

| Potamochoerus larvatus, bush pig |

0.97 (356) |

| Setifer setosus, greater hedgehog tenrec |

3.92–6.72 (3) |

| Tenrec ecaudatus, common tenrec |

0.24–0.48 (93) |

For all species except P. larvatus, values were derived from mean price of individual animals averaged across species divided by a range in adult body mass for that species. Body mass values from Garbutt (2007). For P. larvatus, sales were typically in pieces of 1–2 kg and were thus divided by that range. An exchange rate of $1 USD = 2000 Malagasy ariary was used.

Value of Wildlife

We estimated the value of wildlife to consumers by constructing demand curves with a 2-stage least squares (TSLQ) panel data method. Demand curves are used to represent the functional relation between the quantity of a good demanded by consumers across a spectrum of prices. Because points along the demand curve represent the consumers’ willingness to pay, economists often equate demand curves with the marginal benefit of the good (i.e., benefit of the last unit consumed).

The primary challenge of estimating the value of wildlife consumption among households in our study area was that most wildlife consumption does not occur through market transactions; thus, there is no record of price or value. Accordingly, we used 232 records of price and quantity information from 194 households that engaged in market transactions to estimate a demand function for wildlife. We then used our wildlife demand function (Eq. 1) to estimate the total benefit of wildlife consumption for all households:

| (1) |

where Qi,t is the quantity (kilograms) of wildlife purchased by household i in year t; P is the price per kilogram of wildlife spent by household i in year t; β1 is the price elasticity of demand (i.e., percent change in quantity demanded as a result of a percent change in price); and ε and u are error terms across households and time, respectively. Because there were not enough data points to adequately examine species-specific effects on price, we aggregated all harvested species by weight; the demand curve therefore represents the willingness to pay for an average kilogram of wildlife.

In the first-stage regression, we generated fitted values of price, P̂, from a regression with 2 instrumental variables (IVs). By definition, IVs are correlated with the endogenous explanatory variable in the demand function (Pi,t) but are not independently correlated with the dependent variable (Qi,t) (Bonds et al. 2012). The first stage regression is

| (2) |

The explanatory variables in Eq. 2 are IVs and were selected because they are thought to represent supply side factors (Supporting Information). The variable M is a dummy variable that equaled 1 if the household was near Masoala National Park. We expected this park to have higher populations of mammalian wildlife because of its protection status and longer duration under protection. Makira became an official natural park after we finished collecting data; thus, we expected it to have less of an effect on how conservation policies affect wildlife hunting. The variable S is the regional supply of wildlife for household i at time t. It equals the per capita wildlife consumption of all communities weighted by the distance of each community from household i:

| (3) |

where nv is the number of households in the survey in community v and D is the distance between community v and household i. For the household’s own community, D = 1.

In the second-stage regression, we regressed the quantity of wildlife purchased by each household on the fitted values of price from the first-stage regression

| (4) |

Because our IVs were chosen to represent supply-side factors, this second-stage equation is interpreted as a regression of the quantity demanded of wildlife as a function of supply-driven (i.e., exogenous) changes in price. The outcome of this regression produced the demand curve in Eq. 5 (see Results). Because the demand curve represents marginal benefit, we used the output of this regression analysis to generate an equation for the total benefits (TB) of wildlife. This is equal to the integral of the marginal benefits: TB = ∫MB, where the marginal benefit is the inverse function of the demand curve (Eq. 4). We present the total value as a proportion of total annual cash income, which we calculated as the sum of wages earned, products sold, and items bartered. This measure of cash income neither adds benefits of harvested forest products or agricultural consumption nor subtracts time-allocation costs from labor invested. Therefore, the value of wildlife to local people is in addition to this cash income measure. Results of the second-stage regression allowed for the estimation of an imputed price of wildlife per quantity of wildlife consumed and were used to parameterize Eq. 4, which models the quantity of wildlife a household purchases at a given price. The demand curve can therefore be represented by

| (5) |

To calculate the marginal benefit (MB), we rearranged Eq. 5 so that price was a function of quantity and took the antilog:

| (6) |

The total benefit (TB) of subsistence wildlife consumption for each household per year was the area under the demand curve, as calculated by the integral of Eq. 6:

| (7) |

where Q is the annual amount of wildlife consumption at the household level.

To determine traditional ecosystem-service values of wildlife consumption ($ ha−1·year−1), we estimated the harvest area surrounding each community (Supporting Information). On the basis of dollar values per geographical area, we categorized these community wildlife harvest zones as low (<$0.20 ha−1·year−1), medium ($0.20–0.75 ha−1·year−1) and high (>$0.75 ha−1·year−1) values from natural breaks in the variable. All monetary units are in U.S. dollars.

Results

Ninety-eight percent of consumed wildlife was collected by the hunter and his family, whereas 2% of consumed wildlife was purchased. This finding demonstrates a near absence of a formal market for wildlife in this area. Across the study area, the percentage of households hunting particular taxa ranged widely across taxa: 16% hunted bats, 23% hunted bush pigs (Potamochoerus larvatus), 40% hunted carnivorous species, 49% hunted lemurs, and 91% hunted Tenrecidae. On average, households were extremely poor, with a mean annual household cash income of $140.50 (median $58.93). Decisions to sell wildlife were made on a daily basis and not made on the basis of total harvest for a hunting season. Because of a lack of refrigeration and effective preservation methods, wildlife tended to be sold only if the amount harvested was too great a quantity to consume in a day. Therefore, only bush pigs and bats were sold frequently because they were respectively either too large to consume in a day or were killed in great quantities on a given night.

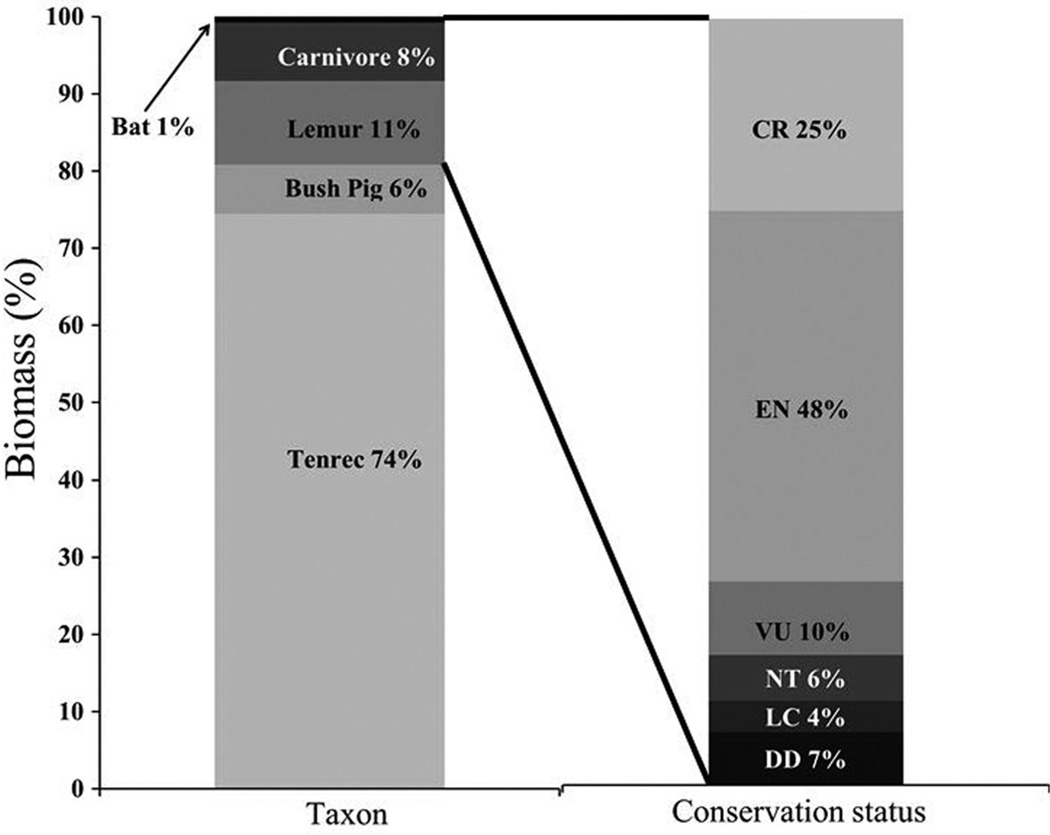

The typical household in our study consumed a mean of 12.98 kg (SE 0.51) of wildlife/year. By biomass, nearly 75% of the wildlife consumed in households were members of the Tenrecidae family, with lemurs, carnivores, bush pigs, and bats comprising the remaining quarter of biomass in that order (Fig. 2). Although it was impossible to determine whether local people followed a specified hunting season of game species through our annual consumption data, approximately 66% of wildlife biomass appeared to be harvested illegally. Thus, on the basis of these harvest data and the assumption of no prey switching, comprehensive enforcement of hunting regulations in our study area could result in a 66% decline of harvested wildlife for households. Among bats, lemurs, and carnivores, nearly 75% of biomass was of species classified as endangered or critically endangered at the time of our study (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

The biomass of wildlife harvested by households in Makira Natural Park and Masoala National Park by taxonomic group and conservation status (IUCN 2012) of illegally harvested species. Certain tenrecs and bush pig are legal to harvest if hunting gear, season of harvest, and other restrictions are followed (CR, critically endangered; EN, endangered; VU, vulnerable; NT, near threatened; LC, least concern; DD, data deficient).

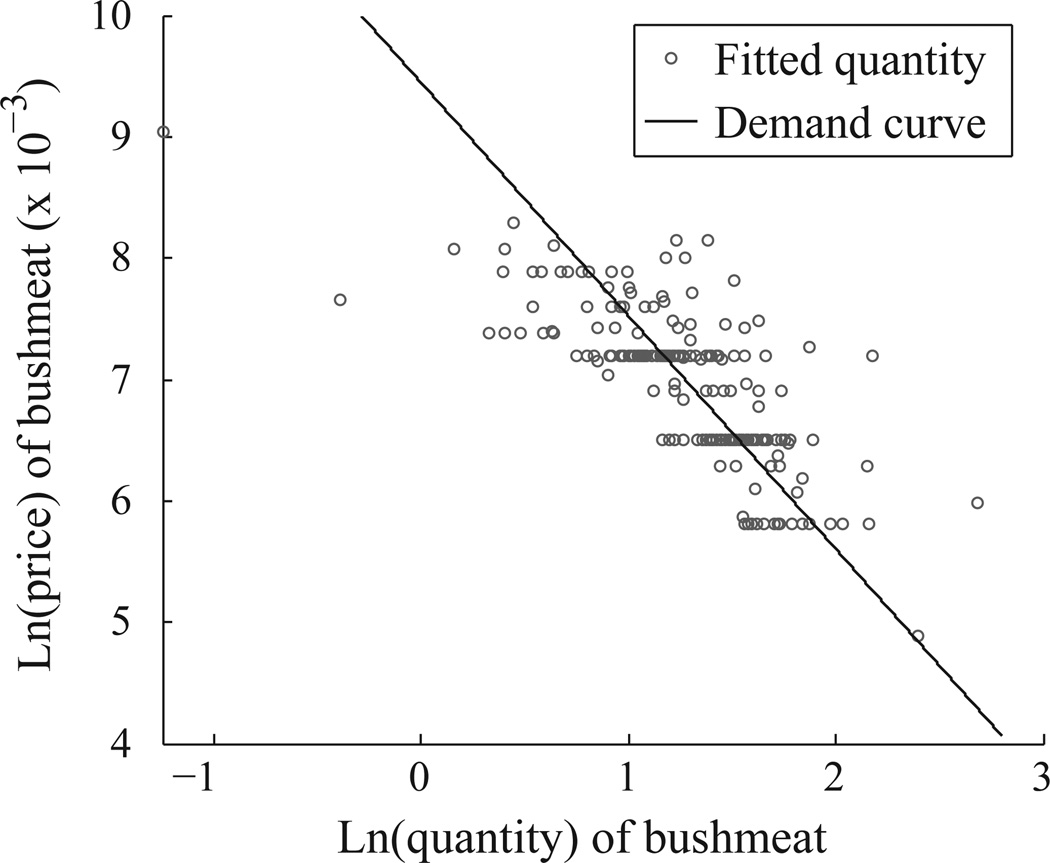

Value of Wildlife Consumption

The price of wildlife was significantly and negatively associated (p < 0.01) with the 2 IVs. These results are highly consistent with the notion that differences between parks and the regional consumption of meat reflect differences in the supply of wildlife. Specifically, a 1% increase in the local supply of wildlife led to a 0.47% decrease in the imputed price of wildlife (p < 0.001). Residents of Masoala paid, on average, 38% less per kilogram of busmeat than residents of Makira (p = 0.004). Thus, consistent with economic theory, as supply increased prices fell, indicating that wildlife price is supply driven. As the imputed price of wildlife increased by 1%, consumption decreased by 1.12% (Table 2).

Table 2.

First- and second-stage regression estimates of instrumental variables and fitted values of price for quantity of wildlife consumed (n = 232).

| Regression Stage |

Independent variable |

Parameter |

|---|---|---|

| First | park dummy (λ1) | −0.38 (0.13) |

| First | ln(regional supply) (λ2) | −0.47 (0.08) |

| First | constant (λ0) | 8.91 (0.46) |

| Second | imputed price (β1) | −1.12 (0.17) |

| Second | constant (β0) | 8.98 (1.02) |

Note: The dependent variable for the first-stage regression was ln(price) for household i in year t. The dependent variable for the second-stage regression was ln(quantity) in kilograms of wildlife. The R2 of the second stage regression was 0.33. All parameter estimates were significant at the 1% level.

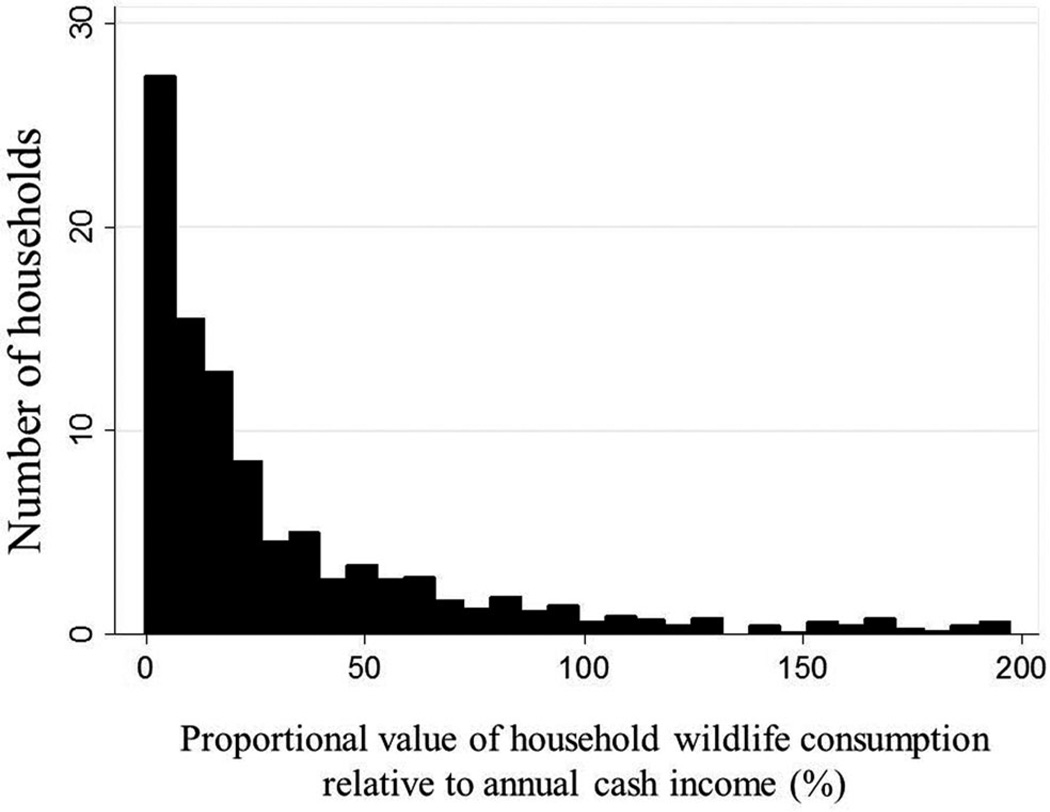

Demand is the marginal benefit each household derives from each additional kilogram of wildlife consumed, which is equivalent to the hunter’s willingness to pay. The negative slope of the demand curve demonstrates the diminishing returns of each additional kilogram of wildlife harvested (Fig. 3). On average, across all surveyed species and households, the mean value of 1 kg of wildlife was $1.40 and the mean total annual benefit value of subsistence wildlife consumption to households was $18.32 in addition to a household’s annual cash income. These values represented approximately 13% of mean annual household cash income in this region or 31% of median annual household cash income. As suggested by this major difference between the mean and median household income values, the proportional value of wildlife to households was highly skewed. The value of wildlife relative to household annual cash income demonstrates its substantial role in household welfare and livelihoods (median: 17.5% of income, mean: 56.7% of income, CI 1.3–190.7%) (Fig. 4). Thus, certain households were harvesting wildlife valued at almost 2 times their annual cash income.

Figure 3.

Demand curve for harvested wildlife in Makira, Madagascar. Demand is the marginal benefit per kilogram (in U.S.$) a household derives from consuming wildlife each year.

Figure 4.

Monetary value of wildlife relative to household annual income. For the purposes of visually presenting the data, values over 200% were excluded (n = 68 of a total 1210).

At the community level, the mean benefit value of wildlife as a provisioning service was $1534.69 per community per year (SE 255.56). The mean value of wildlife as a provisioning service per hectare across communities was $0.42 (SE 0.11) per year, and there were no significant differences between Makira and Masoala (Fig. 1).

Discussion

Our study of wildlife provisioning in Madagascar highlights great variability in the flow of ecosystem services at the community and household scale. Wildlife provisioning is a more tangible ecosystem service than many other types because it is visible, excludable, and exists within a commercial market (albeit small in scale). An awareness of this service and its variability could prove useful in understanding local incentives for conservation or environmental rule-breaking or for development targeting or the creation of payment for ecosystem services schemes. Understanding the effects of lost wildlife provisioning is critical if conservationists wish to assess the effect of enforcement or the potential cost of unsustainable wildlife use on human livelihoods.

We focused only on calculating the total subsistence-benefit value and the potential decreases in utilization and thus value of wildlife due to regulation enforcement (approximately 66% reduction of current value). We ignored the long-term cost to local livelihoods (economic and human health) of unsustainable use leading to depletion of wildlife. Furthermore, because of its protected status, we ignored the possibility of the land being converted to agriculture, yet this type of land-use change could decrease availability of wildlife. Unsustainable harvesting and agricultural extensification are likely to occur in Madagascar, where the current population is 21 million and is expected to exceed 55 million people by 2050 (UNDESA 2013).

For the provisioning service of wildlife to be maintained in the long run, harvest must be sustainable, which is unlikely for many species in the Makira (Golden 2009) and Masoala. In such an economic setting, issues of sus-tainability are unlikely to be considered by local people, particularly when the majority of hunting uses low-cost passive techniques. Animals are caught in snares and traps at rates relatively proportional to their natural ecological abundance. In our analysis of the effect of supply of wildlife on price (Eq. 3), we found that the extractive behaviors of certain communities may disturb the productivity of this ecosystem service and thus affect other communities. Because of the nature of passive hunting, even if a population crashes for a given species, hunting behavior is unlikely to change (Noss 1998; Wilkie & Carpenter 1999) because snares and traps target a broad range of species within taxonomic groups (e.g., lemurs and carnivores). Thus, declines may reach a threshold after which local extinction of rare wildlife species is inevitable (Clayton et al. 1997).

It is illegal to hunt most mammalian species in Madagascar, and 66% of wildlife harvested by biomass in this region may be hunted illegally. We found no major price differences between illegally and legally hunted wildlife. We believe this is consistent with our finding that the demand for wildlife (independent of the source) was relatively elastic. This elasticity limited price variation among groups of wildlife. Furthermore, we suggest that the supply was relatively inelastic; therefore, any upward pressure on prices that illegal harvest would make cannot be directly offset by harvesting legal sources. If conservation policies to prevent specific types of hunting (either illegal or hunting of species listed as vulnerable, endangered, or critically endangered) were monitored and enforced and there was no shift to legally hunted species, the volume, and thus value, of wildlife in households would be reduced. Effective monitoring, in the absence of a shift in hunter behavior, would incur a 66% reduction in the biomass of wildlife consumed. If substantial wildlife depletion occurs or if access is highly restricted, it is likely that prices would increase and consumption would fall (Farley 2008). For legally hunted species, it is vital to maintain reproductive capacity to ensure future flows of benefits, but this action will not solve the environmental or public health issues that arise from depletion of wildlife. Furthermore, the legality of harvest does not ensure sustainability.

At a regional scale, our estimate of benefit value of wildlife, $0.42 ha/year, was substantially lower than other estimates elsewhere (e.g., approximately 2 orders of magnitude less than Cross River National Park, Nigeria [Ruitenbeek 1989] and Iquitos, Peru [Padoch & de Jong 1989]). Our average value per hectare per year likely masks heterogenous values within the harvest area because areas closer to communities are subject to higher levels of hunting (Levi et al. 2009). Although we found a relatively low absolute monetary value for this ecosystem service, markets are imperfect and market valuation weights all preferences by purchasing power (Scitovsky 1993). It is possible our estimates of value are lower than other regions due to methodological differences because we calculated value by estimating marginal benefits through demand curves rather than simply multiplying quantity by price. Furthermore, economically poor, resource-dependent people heavily discount future benefits (Pearce et al. 2003), and these communities are characterized by both of those attributes. Cost-benefit analysis often ignores the distribution of benefits and focuses on potential Pareto improvements, in which those who benefit could hypothetically compensate losers (Farley 2008). Yet, when dealing with such extreme poverty and low capacity to compensate those most affected, it is likely that the costs of conservation will disproportionately burden the poor and vulnerable—those most reliant on access to natural resources (Shyamsundar & Kramer 1996; Shyamsundar & Kramer 1997; Ferraro 2002). Thus, few commodities will have a high monetary value to the economically poor, even if they are essential to life. If they truly are essential and nonsubstitutable, the benefit value is arguably infinite and inestimable (Gowdy 1997).

Although estimating per-hectare monetary values may provide a basis for cross-regional comparisons (Gowdy 1997) or comparisons among alternative management scenarios (e.g., Kremen et al. 2000), measurements at this scale do not elucidate understanding of differences in equity among communities and households and do not illuminate other forms of value, such as health benefits (Golden et al. 2011). Thus, it is important to examine benefits at the community and household levels to estimate the proportional value of a service to local livelihoods (Golden et al. 2012). By calculating this metric, we created a socioeconomic comparison rather than a geographic comparison. Values of wildlife harvest were highly variable among communities and households. Among communities, we identified regions of high, medium, and low wildlife benefit value (Fig. 1) that could be used to target economic or other support to mitigate costs of conservation. Those who have the greatest proportional economic reliance on this service have the greatest incentives for rule-breaking behavior and are likely to be the most resistant to policy changes that restrict access (Keane et al. 2008).

At a finer scale, the proportional value of wildlife compared with annual cash household income was within a 95% CI of 1.3–190.7%. This proportional value can be interpreted as an index of dependence on wild source foods because meat substitutes are often prohibitively expensive in this area. The highly right-skewed variation in dependence (Fig. 4) could allow development and public-health specialists to partition these results to target support at the household level. It is important to keep in mind that we compared these values with household cash income and that a large share of total economic assets was likely derived from subsistence production. As a result, our cash income variable was subject to truncation bias because it was a partial measure for all income, with likely structural variation in the truncation pattern. Certain households may have had larger proportions of their income attributed to cash income, and this may have biased our measure of dependence.

We also found a strong link between rising imputed prices of wildlife being associated with reduced consumption of harvested meat. Wilkie and Godoy (2001) found, in a similarly remote and subsistence setting, that demand for wildlife is elastic and that consumption is reduced through price increases. If enforcement is increased enough to make wildlife consumption a more costly enterprise for consumers in Madagascar, a reduction in consumption may result that would constitute a substantial economic cost of conservation (Naidoo et al. 2006). Increases in the costs of hunting and the correlative increases in the price of harvested wildlife need to be balanced with development or public health assistance to compensate for the loss to consumers, especially because households with lower income consume more wildlife relative to domesticated meat and thus it is of greater proportional value (Golden et al. 2011). Our estimates of the economic value of the foregone benefits of harvested wildlife provide a framework for offsetting losses.

In addition to conservation strategies that may increase the costs of hunting and reduce local harvest of the resource, there are other types of interventions that may decrease local reliance on wildlife as a food source. If the supply of meat of domesticated animals were to rise (which might require significant development interventions), then the price of this meat would fall and would provide an alternative source of meat for consumers (e.g., Apaza et al. 2002). Dietary diversification through the development of alternative animal-source foods and specifically the development of improved and more efficient systems of poultry production (Alders & Pym 2009) may be the best intervention.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the ESRI Conservation Program for the contribution of ArcGIS (version 9.3) software, R. Rajaonson, and N. Randriambololona for geographic information (GIS) assistance, Kew Royal Botanical Gardens for the GIS source files, and E. J. G. Anjaranirina for research assistance. We thank C. Barrett, H. Young, E.J. Milner-Gulland, and three anonymous reviewers for comments on the manuscript. We thank Wildlife Conservation Society (WCS) in Madagascar and the Malagasy Ministry of Environment and Forests for logistical support. For financial support, we acknowledge the National Geographic Society Conservation Trust (grant C135–08), the Margot Marsh Biodiversity Fund (grant 023815), the Mohamed bin Zayed Species Conservation Fund (grant 1025935), WCS, Conservation International, and the National Science Foundation (Doctoral Dissertation Improvement grant 1011714 and Coupled Human Natural Systemsgrant NSF-GEO1115057).

Footnotes

Supporting Information

Further methodological details on wildlife consumption surveys, constructing the demand curve, and calculating ecosystem service values (Appendix S1) are available online. The authors are solely responsible for the content and functionality of these materials. Queries (other than absence of the material) should be directed to the corresponding author.

Literature Cited

- Alders RG, Pym RAE. Village poultry: still important to millions, eight thousand years after domestication. World’s Poultry Science Journal. 2009;65:181–190. [Google Scholar]

- Apaza L, Wilkie D, Byron E, Huanca T, Leonard W, Perez E, Reyes-Garcia V, Vadez V, Godoy R. Meat prices influence the consumption of wildlife by the Tsimane Amerindians of Bolivia. Oryx. 2002;36:382–388. [Google Scholar]

- Balmford A, Fisher B, Green RE, Naidoo R, Strassburg B, Turner RK, Rodrigues ASL. Bringing ecosystem services into the real world: an operational framework for assessing the economic consequences of losing wild nature. Environmental & Resource Economics. 2011;48:161–175. [Google Scholar]

- Bodmer RE, Fang TG, Moya L, Gill R. Managing wildlife to conserve Amazonian forests- population biolody and economic considerations of game hunting. Biological Conservation. 1994;67:29–35. [Google Scholar]

- Bonds MH, Dobson AP, Keenan DC. Disease ecology, biodiversity, and the latitudinal gradient in income. PLoS Biology. 2012;10 doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1001456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brashares JS, Golden CD, Weinbaum KZ, Barrett CB, Okello GV. Economic and geographic drivers of wildlife consumption in rural Africa. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2011;108:13931–13936. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1011526108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapman CA, Peres CA. Primate conservation in the new millennium: the role of scientists. Evolutionary Anthropology. 2001;10:16–33. [Google Scholar]

- Clayton L, Keeling M, Milner-Gulland EJ. Bringing home the bacon: a spatial model of wild pig hunting in Sulawesi, Indonesia. Ecological Applications. 1997;7:642–652. [Google Scholar]

- Costanza R, et al. The value of the world’s ecosystem services and natural capital. Nature. 1997;387:253–260. [Google Scholar]

- de Merode E, Homewood K, Cowlishaw G. The value of bushmeat and other wild foods to rural households living in extreme poverty in Democratic Republic of Congo. Biological Conservation. 2004;118:573–581. [Google Scholar]

- Dew JL, Wright P. Frugivory and seed dispersal by four species of primates in Madagascar’s eastern rain forest. Biotropica. 1998;30:425–437. [Google Scholar]

- Farley J. The role of prices in conserving critical natural capital. Conservation Biology. 2008;22:1399–1408. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1739.2008.01090.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farley J, Costanza R. Payments for ecosystem services: from local to global. Ecological Economics. 2010;69:2060–2068. [Google Scholar]

- Ferraro PJ. The local costs of establishing protected areas in low-income nations: Ranomafana National Park, Madagascar. Ecological Economics. 2002;43:261–275. [Google Scholar]

- Garbutt N. Mammals of Madagascar: a complete guide. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Godoy R, Wilkie D, Overman H, Cubas A, Cubas G, Demmer J, McSweeney K, Brokaw N. Valuation of consumption and sale of forest goods from a Central American rain forest. Nature. 2000;406:62–63. doi: 10.1038/35017647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golden CD. Bushmeat hunting and use in the Makira Forest north-eastern Madagascar: a conservation and livelihoods issue. Oryx. 2009;43:386–392. [Google Scholar]

- Golden CD, Fernald LCH, Brashares JS, Rasolofoniaina BJR, Kremen C. Benefits of wildlife consumption to child nutrition in a biodiversity hotspot. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2011;108:19653–19656. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1112586108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golden CD, Rasolofoniaina BJR, Anjaranirina EJG, Nicolas L, Ravaoliny L, Kremen C. Rainforest pharmacopeia in Madagascar provides high value for current local and prospective global uses. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e41221. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0041221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golden CD, Wrangham RW, Brashares JS. Assessing the accuracy of interviewed recall for rare, highly seasonal events: the case of wildlife consumption in Madagascar. Animal Conservation. 2013;16 [Google Scholar]

- Goodman SM, Benstead JP. Updated estimates of biotic diversity and endemism for Madagascar. Oryx. 2005;39:73–77. [Google Scholar]

- Gowdy JM. The value of biodiversity: Markets, society, and ecosystems. Land Economics. 1997;73:25–41. [Google Scholar]

- IUCN. [accessed 10 October 2012];The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2012.2. 2012 Available from http://www.iucnredlist.org.

- Keane A, Jones JPG, Edwards-Jones G, Milner-Gulland EJ. The sleeping policeman: understanding issues of enforcement and compliance in conservation. Animal Conservation. 2008;11:75–82. [Google Scholar]

- Kremen C, et al. Aligning conservation priorities across taxa in Madagascar with high-resolution planning tools. Science. 2008;320:222–226. doi: 10.1126/science.1155193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kremen C, Niles JO, Dalton MG, Daily GC, Ehrlich PR, Fay JP, Grewal D, Guillery RP. Economic incentives for rain forest conservation across scales. Science. 2000;288:1828–1832. doi: 10.1126/science.288.5472.1828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kremen C, Razafimahatratra V, Guillery RP, Rakotomalala J, Weiss A, Ratsisompatrarivo JS. Designing the Masoala National Park in Madagascar based on biological and socioeconomic data. Conservation Biology. 1999;13:1055–1068. [Google Scholar]

- Levi T, Shepard GH, Jr., Ohl-Schacherer J, Peres CA, Yu DW. Modelling the long-term sustainability of indigenous hunting in Manu National Park, Peru: landscape-scale management implications for Amazonia. Journal of Applied Ecology. 2009;46:804–814. [Google Scholar]

- Millennium Ecosystem Assessment (MEA) Ecosystems and human well-being: synthesis. Washington, D.C.: Island Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Milner-Gulland EJ, et al. Wild meat: the bigger picture. Trends in Ecology & Evolution. 2003;18:351–357. [Google Scholar]

- Naidoo R, Balmford A, Ferraro PJ, Polasky S, Ricketts TH, Rouget M. Integrating economic costs into conservation planning. Trends in Ecology & Evolution. 2006;21:681–687. doi: 10.1016/j.tree.2006.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naidoo R, Ricketts TH. Mapping the economic costs and benefits of conservation. PLoS Biology. 2006;4:2153–2164. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0040360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newton P, Nichols ES, Endo W, Peres CA. Consequences of actor level livelihood heterogeneity for additionality in a tropical forest payment for ecosystem services programme with an undifferentiated reward structure. Global Environmental Change. 2012;22:127–136. [Google Scholar]

- Noss AJ. The impacts of cable snare hunting on wildlife populations in the forests of the Central African Republic. Conservation Biology. 1998;12:390–398. [Google Scholar]

- Ormsby A, Mannle K. Ecotourism benefits and the role of local guides at Masoala National Park, Madagascar. Journal of Sustainable Tourism. 2006;14:271–287. [Google Scholar]

- Padoch C, de Jong W. Production and profit in agroforestry: an example from the Peruvian Amazon. In: Browder J, editor. Fragile lands of Latin America: strategies for sustainable development. Boulder, CO: Westview Press; 1989. pp. 102–113. [Google Scholar]

- Pagiola S, Von Ritter K, Bishop J. Environment Department Papers. Washington, D.C.: The World Bank; 2004. Assessing the economic value of ecosystem conservation; p. 101. [Google Scholar]

- Pearce D, Groom B, Hepburn C, Koundouri P. Valuing the future: recent advances in social discounting. World Economics. 2003;4:121–141. [Google Scholar]

- Refisch J, Kone I. Impact of commercial hunting on monkey populations in the Tai region, Cote d’Ivoire. Biotropica. 2005;37:136–144. [Google Scholar]

- Robinson J, Bennett E. Hunting for sustainability in tropical forests. New York: Columbia University Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Ruitenbeek H. Economic analysis of issues and projects relating to the establishment of the proposed cross river national park (Oban Division) and support zone. London: World Wide Fund for Nature; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Scitovsky T. The meaning, nature, and source of value in economics. In: Hechter M, Nadel L, Michod R, editors. The origin of values. New York: de Gruyter; 1993. pp. 93–105. [Google Scholar]

- Shyamsundar P, Kramer RA. Tropical forest protection: an empirical analysis of the costs borne by local people. Journal of Environmental Economics and Management. 1996;31:129–144. [Google Scholar]

- Shyamsundar P, Kramer R. Biodiversity conservation—at what cost? A study of households in the vicinity of Madagascar’s Mantadia National Park. Ambio. 1997;26:180–184. [Google Scholar]

- Steel E. Study of the value and volume of bushmeat commerce in Gabon. World Wildlife Fund; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs (UNDESA) World population prospects: the 2010 revision. UN, New York: 2013. [accessed April 2013]. Available from http://esa.un.org/unpd/wpp/index.htm. [Google Scholar]

- Wilkie DS, Carpenter JF. Bushmeat hunting in the Congo Basin: an assessment of impacts and options for mitigation. Biodiversity and Conservation. 1999;8:927–955. [Google Scholar]

- Wilkie DS, Godoy RA. Income and price elasticities of bushmeat demand in lowland Amerindian societies. Conservation Biology. 2001;15:761–769. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.