Abstract

p73 is a member of the p53 protein family. Although the tumor suppressor function of p53 is clearly defined, the role of p73 in tumorigenesis is still a matter of debate. A complex pattern of expression of p73 isoforms makes it difficult to unambiguously interpret the experimental results. Previously, we and others have found that the N-terminally truncated isoform of p73, ΔNp73, has potent anti-apoptotic and oncogenic properties in vitro and in vivo. In the present study, we analyzed, for the first time, the regulation of ΔNp73 in a large number of gastric, gastroesophageal junction and esophageal tumors. We found that expression of ΔNp73 mRNA and protein is increased in these neoplasms. Furthermore, the up-regulation of the ΔNp73 protein is significantly associated with poor patient survival. Oncogenic properties of ΔNp73 were further confirmed by finding that ΔNp73 facilitates anchorage-independent growth of gastric epithelial cells in soft agar. As little is currently known about the regulation of ΔNp73 transcription, we investigated the alternative p73 gene promoter that mediates the ΔNp73 expression. Analyzing the ΔNp73 promoter in silico as well as by using chromatin immunoprecipitation, site-directed mutagenesis and deletion analyses we identified the evolutionary conserved region within the ΔNp73 promoter that contains binding sites for HIC1 protein. We found that HIC1 negatively regulates ΔNp73 transcription in mucosal epithelial cells. This leads to a decrease in ΔNp73 protein levels and may normally control the oncogenic potential of the ΔNp73 isoform.

Keywords: p73, gastric tumor, esophageal tumor

Introduction

p73 is a member of the p53 protein family of transcription factors. p73 and p53 have significant structural and functional similarities. The DNA binding domain of p73 shares 62% amino acid identity with p53 (Melino et al., 2003). This translates into similar functional properties; p73 and p53 transactivate an overlapping set of target genes, induce apoptosis, cell cycle arrest and cellular senescence. However, there are also significant differences. In contrast to p53, which is mutated in human tumors, p73 is frequently over-expressed without mutations. We and others have hypothesized that this occurs because the p73 gene (TP73) can produce additional isoforms with oncogenic properties (Buhlmann and Putzer, 2008; Cam et al., 2006; Zaika and El-Rifai, 2006). p73 isoforms can be divided into two groups, termed TA and ΔN (or ΔTA). TAp73 isoforms contain the N-terminal transactivation domain, are induced by DNA damage and potentially have tumor suppressor properties (Lin et al., 2004; Tomasini et al., 2008). In contrast, ΔN isoforms partially or completely lack the transactivation domain and are potent dominant-negative inhibitors of p53 and TAp73. An extensive body of data show that they may behave as oncogenes. We found that ΔNp73 immortalizes murine cells and cooperates with other oncogenes in cellular transformation of primary mouse embryonic fibroblasts (Petrenko et al., 2003). Subcutaneous injection of these transformed cells into immunocompromised mice produces tumors. ΔNp73 also inhibits differentiation and promotes malignant transformation of myobasts (Cam et al., 2006). Transgenic expression of ΔNp73 leads to tumor formation in mice (Tannapfel et al., 2008). It has also been reported that ΔNp73 is over-expressed in a number of human tumors (Casciano et al., 2002; Vilgelm et al., 2008b).

Regulation of ΔNp73 expression remains largely unknown. The TP73 gene has two promoters, P1 and P2. The P1 promoter mediates expression of TA isoforms, while the intragenic P2 promoter is responsible for ΔNp73 transcription (Vilgelm et al., 2008a). In addition, aberrant splicing of TAp73 transcripts may lead to ΔNp73 increase (Stiewe et al., 2004). Currently, p53 and TAp73 are the only well characterized transcription factor that are known to regulate the P2 promoter. The studies found that induction of ΔNp73 leads to p53 and TAp73 inhibition and creates a feedback mechanism that negatively controls their transcription activities. (Grob et al., 2001; Kartasheva et al., 2002; Nakagawa et al., 2002). However, due to frequent tumor-specific inactivation of p53, it is unlikely that p53 is a major regulator of ΔNp73 transcription in tumor tissues.

HIC1 (Hypermethylated In Cancer) is a sequence-specific transcriptional repressor that plays a tumor suppressor role. Ectopic expression of HIC1 suppresses growth and survival of tumor cells (Wales et al., 1995). Germline disruption of one allele of the HIC1 gene predisposes mice to spontaneous tumors in which the wild-type allele is inactivated. HIC1 is also frequently inactivated by epigenetic mechanisms in gastric and other human tumors (summarized in (Chen and Baylin, 2005)).

Here we investigated the regulation of ΔNp73 expression in human upper gastrointestinal tumors and found that HIC1 is involved in transcriptional repression of the ΔNp73 promoter in gastric epithelial cells.

Results and Discussion

Expression of ΔNp73 in gastric tumors

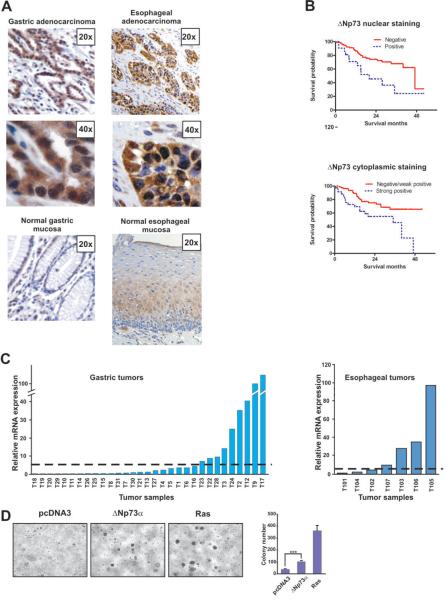

The clinicopathological role of ΔNp73 has not been previously assessed in gastric and esophageal tumors. Therefore, we first analyzed the expression of ΔNp73 protein using immunohistochemistry with ΔNp73-specific antibody. Three tissue microarray blocks composed of the clinical material from 185 patients with gastric, gastroesophageal junction (GEJ) and esophageal cancers who had surgical resection at Vanderbilt University Medical Center, United States and the University of Barcelona, Spain were analyzed by a pathologist in a blind manner. We found that expression of the ΔNp73 protein is significantly increased in the nuclei and cytoplasms of tumor epithelial cells compared to the normal mucosa (Fig. 1A). The nuclear and cytoplasmic expressions of ΔNp73 were further analyzed for association with clinicopathological variables. We found a significant difference in survival between gastric cancer patients with high levels of nuclear ΔNp73 and those with a negative/weak expression (p=.005, log-rank test). The median survival time for patients with an increased nuclear ΔNp73 was 20 months, while that of patients with a negative/weak expression was 47 months (Fig. 1B, upper panel). Similarly, elevated levels of cytoplasmic ΔNp73 was significantly correlated with a poor survival rate of gastric cancer patients (p=.009, log-rank test, Fig. 1B, lower panel). Cytoplasmic (but not nuclear) expression of ΔNp73 was also marginally associated (p=.05) with the survival of esophageal and GEJ cancer patients (Supplementary Table 1). There were no statistically significant associations between ΔNp73 expression and other clinicopathological parameters except between cytoplasmic ΔNp73 and lymph node metastases and pT classification (Supplementary Table 2 and 3). In multivariate analysis using Cox proportional hazards model, ΔNp73 was not an independent prognostic factor (p=.09).

Figure 1. Expression of ΔNp73 in gastric and esophageal tumors.

A. Representative immunostaining for ΔNp73 in. gastric and esophageal adenocarcinomas and corresponding normal mucosas. Original magnification 20× and 40×. ΔNp73-specific antibody (Imgenex, San Diego, CA, 1:200 dilution) was used in this analysis. The immunoreactivity was interpreted as positive when more than 10% of tumor cells showed positivity for nuclear ΔNp73. Staining specificity was verified by omitting a primary antibody step in the protocol. The detailed immunohistochemistry protocol was described previously (Vilgelm et al., 2008b). The analyzed tissue samples were obtained after approval by the Institutional Review Boards. B. Kaplan-Meier survival curve for gastric stratified according to nuclear and cytoplasmic ΔNp73 expression. Statistical significance was assessed by the log-rank test. C. Left panel: Relative expression of ΔNp73 transcripts in primary gastric tumors compared to the average ΔNp73 level in 16 normal mucosal biopsies. Right panel: Relative expression of ΔNp73 mRNA in esophageal tumors compared to the average ΔNp73 level in 4 normal mucosal biopsies. Dashed line shows an arbitrary cut-off, delineating tumors with five-fold or higher relative expression. Data were normalized to HPRT1 mRNA expression. Sequences of primers used for qPCR are shown in Supplementary Table 4. D. ΔNp73α promotes the anchorage-independent growth of immortalized mouse gastric epithelial cells (MGEC). The cells bear a temperature-sensitive mutant of SV40 large T antigen under the control of an γIFN-inducible promoter and were cultured in RPMI-1640 medium supplemented with 5% FBS and 0.3 ng/ml interferon-γ at 33°C. Soft-agar assay was carried out as described previously (Wang et al., 2002). Left panel: representative images of colonies growing in soft agar. Right panel: average number of colonies (per field ±s.d, n=10). Transfection with oncogenic KRAS(V12) was used as a positive control (Petrenko et al., 2003).

To analyze mechanisms of ΔNp73 regulation, we next examined the expression of ΔNp73 mRNA in 31 gastric and 7 esophageal tumors. We employed real-time RT-PCR with primers, which specifically amplify ΔNp73 transcripts derived from the P2 promoter. Our analysis of the ΔNp73 mRNA expression found a frequent over-expression of this transcript in 29% (9/31) gastric tumors (Fig. 1C, left panel) and in 57% (4/7) esophageal tumors (Fig. 1C, right panel). The over-expression was defined as an arbitrary cut-off, delineating tumors with five-fold or higher mRNA up-regulation compared to the average normal level in 16 normal gastric and 4 normal esophageal mucosal biopsies (shown as a dashed line in Fig. 1C).

The tumor-specific over-expression of ΔNp73 is consistent with the oncogenic function of ΔNp73. To further confirm this, non-neoplastic immortalized murine gastric epithelial cells (MGEC), which harbor a temperature-sensitive mutation of the SV40 large T antigen (ts-TAg), were transfected with ΔNp73α and then cultured in soft-agar until visible colonies were formed. Control vector-transfected cells failed to efficiently grow forming a few small size colonies in soft agar. In contrast, ΔNp73α facilitated the anchorage-independent growth and produced multiple large-size colonies suggesting that ΔNp73α plays an oncogenic role in gastric epithelial cells (Fig. 1D).

Regulation of ΔNp73

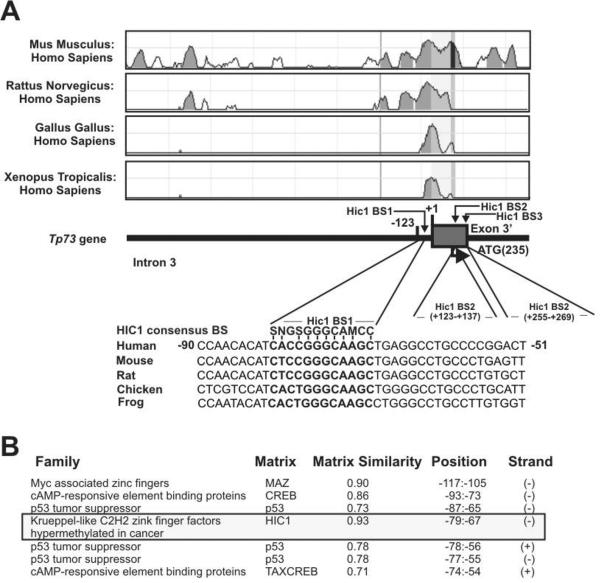

As shown above, ΔNp73 transcription is significantly increased in analyzed tumors. Currently, little is known about the regulation of the alternative P2 promoter that mediates the transcription of ΔNp73. To investigate this promoter, we initially carried out its analysis in silico. Using comparative sequencing analysis with the rVista (v. 2.0) computational tool (Loots and Ovcharenko, 2004), ΔNp73 promoter was investigated for potential cis-regulatory elements. Based on the comparison of homologous sequences from different species, we identified a small region (~250 bp) in the ΔNp73 promoter that is highly conservative in human, mouse, rat, chicken and frog (Fig. 2A). Further analysis of this region found three potential binding sites for zinc-finger transcriptional repressor, HIC1. The highest similarity to the HIC1 consensus binding site was found for the site located at position −80/−69 (Fig. 2A). The presence of the HIC1 binding site was also confirmed by the Genomatix MatInspector software (Fig. 2B).

Figure 2. The ΔNp73 promoter analysis in silico.

A. Multiple alignment of the ΔNp73 promoter from the indicated species using the rVista computational tool (Loots and Ovcharenko, 2004). Bottom panel: positions of the HIC1 binding sites (BS). B. Analysis of the ΔNp73 promoter using the Genomatix MatInspector software (Cartharius et al., 2005).

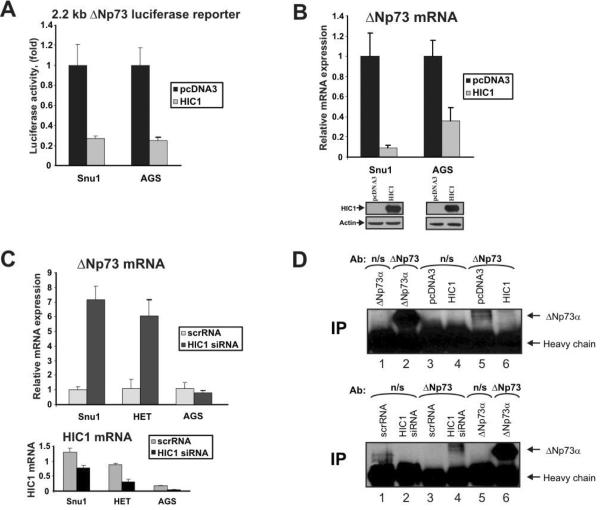

To further investigate the regulation of ΔNp73, gastric epithelial cell lines, SNU1 and AGS were co-transfected with HIC1 and luciferase reporter, which expresses luciferase under the control of 2.2 kb ΔNp73 promoter. As is shown in Figure 3A, transfection of HIC1 significantly decreased the luciferase activity suggesting that HIC1 is a negative regulator of ΔNp73 promoter. Consistent with this analysis, we found that ectopic HIC1 also suppressed the expression of both endogenous ΔNp73 mRNA (Fig. 3B) and protein (Fig. 3D, upper panel, compare lanes 5 and 6). To analyze the effect of endogenous HIC1, SNU1, HET-1A, and AGS cells were transfected with siRNA against HIC1. HET-1A esophageal cells were selected as a prototypical non-neoplastic cell line as it is derived from normal epithelial cells. Inhibition of endogenous HIC1 in SNU1 and HET-1A cell lines not only significantly increased levels of ΔNp73 mRNA (Fig. 3C) but also ΔNp73 protein confirming that HIC1 negatively regulates ΔNp73 (Fig. 3D, bottom panel, compare lanes 3 and 4). Interestingly, the effect of HIC1 siRNA was significantly diminished in AGS cells that express low levels of the endogenous HIC1 mRNA and protein (Fig. 3C, bottom panel and data not shown).

Figure 3. HIC1 inhibits ΔNp73 expression.

A. HIC1 inhibits activity of ΔNp73 luciferase reporter in SNU1 and AGS gastric epithelial cells. Cells were transfected with luciferase reporter containing a 2.2 kb fragment of the ΔNp73 promoter together with HIC1 expression plasmid or control empty vector. ΔNp73 promoter activity was measured 24hrs after transfection using Dual-Luciferase Reporter Assay kit (Promega, Madison, WI) as described previously (Vilgelm et al., 2008b). SNU1 and AGS cells (ATCC, Manassas, VA) were maintained in Ham's F-12 media (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) supplemented with 10% FBS. Transfections were performed with FuGENE 6 reagent (Roche, Indianapolis, IN) using the manufacturer's protocol. ΔNp73 luciferase reporter was kindly provided by Dr. Melino (University of Rome, Italy). Human HIC1 expression plasmid was a generous gift of Dr. Leprince (Institut de Biologie de Lille, France). B. Down-regulation of endogenous ΔNp73 mRNA after HIC1 transfection into SNU1 and AGS cells. Cells were transfected with Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) using the manufacturer's protocol. mRNA levels were measured by qPCR 48 hrs after transfection as described previously (Vilgelm et al., 2008b). Primers used for qPCR are shown in Supplementary Table 4. Bottom panel: Western blot analysis of HIC1 protein. C. Inactivation of endogenous HIC1 with specific siRNA induces expression of ΔNp73 mRNA. SNU1, AGS and HET-1A cells were transfected with siRNA against HIC1 (Ambion, Austin, TX). mRNA levels of ΔNp73 (top panel) and HIC1 (bottom panel) were analyzed by qPCR 72 hrs after transfection. HET-1A immortalized non-neoplastic esophageal cells (ATCC, Manassas, VA) were maintained in DMEM media (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) supplemented with 10% FBS. D. HIC1 inhibits expression of ΔNp73 protein. To increase specificity of the analysis, ΔNp73 protein was immunoprecipitated with ΔNp73-specific antibody (Imgenex, San Diego, CA) and Western blotted with another p73 antibody (AB-2, Calbiochem, La Jolla, CA), which recognizes ΔNp73 protein. Top panel: AGS cells were transfected with ΔNp73, pcDNA3 or HIC1 plasmids for 48 hrs and then immunoprecipitated with ΔNp73-specific or control mouse non-specific (n/s) (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA) antibodies. Western blot was performed with the p73 antibody (AB-2). Bottom panel: same as top panel except SNU1 cells were transfected with HIC1 siRNA.

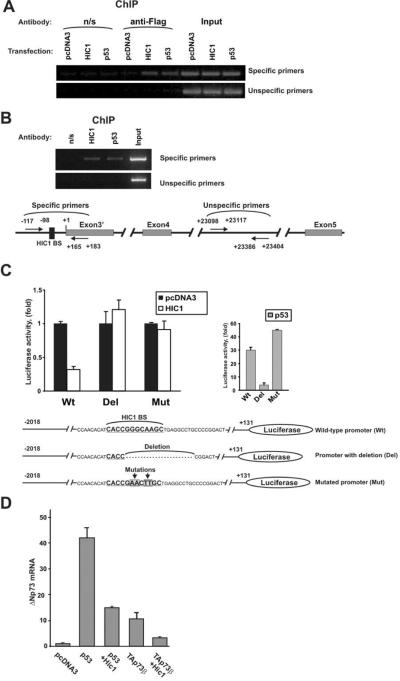

Next, we asked whether this effect is mediated by direct binding of HIC1 to the ΔNp73 promoter. SNU1 cells were transfected with Flag-tagged HIC1 expression vector and analyzed for HIC1 binding to ΔNp73 promoter using chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP). p53, which is known to be bound to this promoter, was used as an additional positive control. Unspecific IgG (n/s) and amplification with distal unspecific primers were used as negative controls. Positions of all primers are shown in Figure 4B (bottom panel). The ChIP analysis with Flag antibody found strong binding of HIC1 to the ΔNp73 promoter (Fig. 4A). To confirm binding of the endogenous HIC1, we also carried out ChIP analysis using HIC1 antibody. As shown in Figure 4B, similar to the ectopic protein, the endogenous HIC1 binds to the ΔNp73 promoter.

Figure 4. HIC1 protein binds to the ΔNp73 promoter.

A. Binding of HIC1 to the native ΔNp73 promoter. SNU1 cells were transfected with the indicated Flag-tagged plasmids. HIC1 binding was analyzed by ChIP with anti-Flag antibody (M2, Sigma, St Louis, MO) using the ChIP Assay Kit from Upstate Biotechnology (Lake Placid, NY). B. Endogenous HIC1 protein binds to the ΔNp73 promoter. ChIP analysis was performed with HIC1-specific antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA) in SNU1 cells. As negative and positive controls precipitations with non-specific rabbit IgG (Jackson ImmunoResearch) and p53-specific antibody (DO1, Calbiochem, La Jolla, CA) were performed, respectively. Bottom panel: positions of ChIP primers. Sequences of primers are shown in Supplementary Table 4. C. Deletion or mutation of the HIC1 BS attenuates the inhibitory function of HIC1 at the ΔNp73 promoter. MKN75 gastric cancer cells were transfected with the indicated luciferase reporters and HIC1 activity was then analyzed using reporter assay. Bottom panel shows sequences of ΔNp73 luciferase reporters. Mutated ΔNp73 reporter was generated by site-directed mutagenesis using the site-directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA). MKN75 were maintained in RPMI media (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) supplemented with 10% FBS. ΔNp73 luciferase reporter was kindly provided by Dr. Melino. D. HIC1 inhibits expression of ΔNp73 mRNA induced by p53 and TAp73. MKN28 gastric epithelial cells were maintained in RPMI medium supplemented with 10% FBS. Cells were transfected with the indicated plasmids and expression of ΔNp73 mRNA was analyzed using qPCR as described previously (Vilgelm et al., 2008b).

However, the ChIP analysis does not provide sufficient resolution to precisely characterize the HIC1 binding site. As so, we conducted deletion analysis and site-directed mutagenesis of the ΔNp73 promoter. We found that a small deletion of 20 bp that encompasses a significant part of the HIC1 binding site led to complete loss of response to HIC1 suppression in MKN75 cells (Fig. 4C). A similar effect was also seen in other cells, AGS and SNU1 (data not shown) suggesting that HIC1 binds to this site. To further confirm that this binding site is responsible for the effect of HIC1 and minimize effects of other transcription factors we introduced four point mutations into the HIC1 binding site and tested the mutated promoter using reporter analysis (Fig. 4C). These specific mutations completely suppressed the inhibitory effect of HIC1 on the ΔNp73 promoter further supporting our data. Notably, these mutations did not inhibit activation of the promoter by p53 even though p53 and HIC1 binding sites are located in close proximity (Fig. 4C, left panel). In fact, p53 activation of the mutant ΔNp73 promoter was approximately 1.5-fold higher than that of the wild-type promoter. This suggests that endogenous HIC1 may interfere with the regulation of the ΔNp73 reporter by p53. To further investigate functional interaction between HIC1 and p53 at the ΔNp73 promoter we transfected MKN28 cells with either the p53 plasmid alone or in combination with HIC1. We found that HIC1 inhibited activation of ΔNp73 expression by p53 (Fig. 4D). Notably, it also inhibited activity of TAp73, which has also been shown to regulate the ΔNp73 expression through the same p53-binding site (Nakagawa et al., 2002)(Fig. 4D). Similar results were obtained in other cell lines including AGS, SNU1 and HET-1A (data not shown).

In order to confirm our findings, we analyzed the correlation between HIC1 and Δp73 mRNA in human primary gastric and esophageal tumors. Only a trend of inverse correlation between HIC1 and ΔNp73 (ρ=−0.22, p=.2; Spearman rank correlation) was found in the combined set of 26 gastric and esophageal specimens (Supplementary Figure 1B). However, in the subset of esophageal tissues (n=11) significant inverse correlation (ρ=−0.68, p=.03) was found (Supplementary Figure 1C). Thus, HIC1 may contribute to the ΔNp73 regulation in vivo. In addition, we evaluated p53 and TAp73 as potential regulators of the Δp73 transcription. The Δp73 mRNA expression was not significantly associated with the mutational status of p53 (p=.11, Wilcoxon rank sum test) suggesting that p53 is not a main regulator of ΔNp73 in these tumors. In contrast, we found that the expression of ΔNp73 mRNA positively correlates with TAp73 (ρ=0.72, p<.001) in gastric and esophageal tumors (Supplementary Figures 1A, 1D). This is consistent with the important role of TAp73 in the regulation of ΔNp73 expression (Nakagawa et al., 2002).

Taken together, our analyses show, for the first time, that ΔNp73 plays important role in gastric tumorigenesis and its increased expression is associated with poor survival of patients with gastric tumors. We also found that HIC1 tumor suppressor binds to the ΔNp73 promoter and inhibits its activity. Our data suggest that loss of HIC1, which frequently occurred in human gastric tumors (Kanai et al., 1998), may lead to the up-regulation of ΔNp73. As a result, ΔNp73 inhibits p53 and TAp73 activities and promotes gastric tumorigenesis.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Cancer Institute grant NIH CA108956 and Vanderbilt CTSA grant UL1 RR024975.

We thank Drs. Castells and Pera of University of Barcelona for their assistance.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Buhlmann S, Putzer BM. DNp73 a matter of cancer: mechanisms and clinical implications. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2008;1785:207–16. doi: 10.1016/j.bbcan.2008.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cam H, Griesmann H, Beitzinger M, Hofmann L, Beinoraviciute-Kellner R, Sauer M, et al. p53 family members in myogenic differentiation and rhabdomyosarcoma development. Cancer Cell. 2006;10:281–93. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2006.08.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casciano I, Mazzocco K, Boni L, Pagnan G, Banelli B, Allemanni G, et al. Expression of DeltaNp73 is a molecular marker for adverse outcome in neuroblastoma patients. Cell Death Differ. 2002;9:246–51. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4400993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen WY, Baylin SB. Inactivation of tumor suppressor genes: choice between genetic and epigenetic routes. Cell Cycle. 2005;4:10–2. doi: 10.4161/cc.4.1.1361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grob TJ, Novak U, Maisse C, Barcaroli D, Luthi AU, Pirnia F, et al. Human delta Np73 regulates a dominant negative feedback loop for TAp73 and p53. Cell Death Differ. 2001;8:1213–23. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4400962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanai Y, Ushijima S, Ochiai A, Eguchi K, Hui A, Hirohashi S. DNA hypermethylation at the D17S5 locus is associated with gastric carcinogenesis. Cancer Lett. 1998;122:135–41. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3835(97)00380-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kartasheva NN, Contente A, Lenz-Stoppler C, Roth J, Dobbelstein M. p53 induces the expression of its antagonist p73 Delta N, establishing an autoregulatory feedback loop. Oncogene. 2002;21:4715–27. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1205584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin KW, Nam SY, Toh WH, Dulloo I, Sabapathy K. Multiple stress signals induce p73beta accumulation. Neoplasia. 2004;6:546–57. doi: 10.1593/neo.04205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loots GG, Ovcharenko I. rVISTA 2.0: evolutionary analysis of transcription factor binding sites. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:W217–21. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melino G, Lu X, Gasco M, Crook T, Knight RA. Functional regulation of p73 and p63: development and cancer. Trends Biochem Sci. 2003;28:663–70. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2003.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakagawa T, Takahashi M, Ozaki T, Watanabe Ki K, Todo S, Mizuguchi H, et al. Autoinhibitory regulation of p73 by Delta Np73 to modulate cell survival and death through a p73-specific target element within the Delta Np73 promoter. Mol Cell Biol. 2002;22:2575–85. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.8.2575-2585.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petrenko O, Zaika A, Moll UM. deltaNp73 facilitates cell immortalization and cooperates with oncogenic Ras in cellular transformation in vivo. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23:5540–55. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.16.5540-5555.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stiewe T, Tuve S, Peter M, Tannapfel A, Elmaagacli AH, Putzer BM. Quantitative TP73 transcript analysis in hepatocellular carcinomas. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10:626–33. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.ccr-0153-03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tannapfel A, John K, Mise N, Schmidt A, Buhlmann S, Ibrahim SM, et al. Autonomous growth and hepatocarcinogenesis in transgenic mice expressing the p53 family inhibitor DNp73. Carcinogenesis. 2008;29:211–8. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgm236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomasini R, Tsuchihara K, Wilhelm M, Fujitani M, Rufini A, Cheung CC, et al. TAp73 knockout shows genomic instability with infertility and tumor suppressor functions. Genes Dev. 2008;22:2677–91. doi: 10.1101/gad.1695308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vilgelm A, El-Rifai W, Zaika A. Therapeutic prospects for p73 and p63: rising from the shadow of p53. Drug Resist Updat. 2008a;11:152–63. doi: 10.1016/j.drup.2008.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vilgelm A, Wei JX, Piazuelo MB, Washington MK, Prassolov V, El-Rifai W, et al. DeltaNp73alpha regulates MDR1 expression by inhibiting p53 function. Oncogene. 2008b;27:2170–6. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wales MM, Biel MA, el Deiry W, Nelkin BD, Issa JP, Cavenee WK, et al. p53 activates expression of HIC-1, a new candidate tumour suppressor gene on 17p13.3. Nat Med. 1995;1:570–7. doi: 10.1038/nm0695-570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang F, Hansen RK, Radisky D, Yoneda T, Barcellos-Hoff MH, Petersen OW, et al. Phenotypic reversion or death of cancer cells by altering signaling pathways in three-dimensional contexts. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2002;94:1494–503. doi: 10.1093/jnci/94.19.1494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaika AI, El-Rifai W. The role of p53 protein family in gastrointestinal malignancies. Cell Death Differ. 2006;13:935–40. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.