Abstract

As novel postnatal stem cells, gingiva-derived mesenchymal stem cells (GMSCs) have been considered as an ideal candidate cell resource for tissue engineering and cell-based therapies. GMSCs implanted into sites of injury have been confirmed to promote the injury repair. However, no studies have demonstrated whether systemically transplanted GMSCs can home to the bone injuries and contribute to the new bone formation in vivo. In this study, we transplanted human GMSCs into C57BL/6J mice with defects in mandibular bone via the tail vein to explore the capacity of transplanted GMSCs to promote bone regeneration. Results showed that the transplanted GMSCs were detected in the bone defects and employed in new bone formation. And the newly formed bone area in mice with GMSCs transplantation was significantly higher than that in control mice. Our findings indicate that systemically transplanted GMSCs can not only home to the mandibular defect but also promote bone regeneration.

Keywords: Gingiva, mesenchymal stromal cells, bone regeneration, mice

Introduction

Bone injuries in the oral and maxillofacial area due to trauma, tumor resection and infectious diseases may have a serious impact on masticatory function, facial aesthetics and psychological health of patients. Demand for physiological and functional reconstruction is pressing. The optimal bone reconstruction for healing is the regeneration of the damaged tissues. Similar to embryonic development the process of bone regeneration for repair involves a series of cellular events, the most important of which is mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) recruitment to the wound site as well as proliferation and differentiation into osteoblasts and chondrocytes [1,2]. As stem cells especially MSCs present a great hope for repairing almost all type of tissues, the cell-based therapies have been a promising alternative for bone healing [3].

Because of the ability of self-renewal and multiple differentiation potential, bone marrow stromal cells (BMSCs) have played a significant role in cell-based therapy and tissue engineering in the past years. However, the disadvantages in cell isolation, aging and limited proliferative property restrict the utility of BMSCs for clinical application [4,5]. In addition, MSCs derived from various dental tissues such as dental pulp, periodontal ligament and dental follicles have also shown the potential to differentiate into many cell types [3,6]. And yet these cells are not easily obtained or cultured. Gingiva-derived mesenchymal stem cells (GMSCs), obtained from gingival tissue, are a type of pluripotent mesenchymal stem cells with self-renewal, multipotent differentiation potential and immunomodulatory capacities [5,7,8]. As novel postnatal stem cells, GMSCs have been paid great attention for ease of isolation, high proliferation capacity, uniformly homogenous property, stable phenotype, and importantly, maintaining normal karyotype and telomerase activity during prolonged culture time [5]. Thus, GMSCs are considered as an ideal candidate cell resource for tissue engineering and cell-based therapies. GMSCs transplanted into the periodontal defects have been confirmed to participate and contribute to the periodontal regeneration in animal models [9]. After implantation into the mandibular defects in animal models, GMSCs showed great promotion to the bone healing [10]. Various studies demonstrated when delivered systemically into humans and animals, MSCs selectively home to the sites of injury and provide therapeutic benefits [11-14]. These reports lead us to hypothesize that systemically transplanted GMSCs can home to the bone defects and be employed in bone regeneration in vivo. In this study, we transplanted human GMSCs into C57BL/6J mice with defects in mandibular bone via the tail vein to explore the capacity of transplanted GMSCs to promote bone regeneration.

Materials and methods

Animals

A total of 36 seven-week-old male C57BL/6J mice purchased from Peking University Health Science Center (Beijing, China) were used in this study. The animals were kept under specific pathogen-free conditions with controlled temperature (22 ± 2°C), humidity (60%) and lighting (12-h light/dark cycle). The experimental protocol was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Qingdao University, Qingdao, Shandong Province, China.

Isolation of GMSCs

Human gingival tissues were obtained from young adult donors (18-25 years old) who had no history of periodontal disease during surgery with informed consent and approval of the clinical research ethics committee of Qingdao University. The gingival tissue was washed several times with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) containing 400 μg/ml streptomycin and 400 U/ml penicillin and incubated in a medium containing 2 mg/ml dispase (Sigma) at 4°C overnight. Then the epithelial layer was easily separated from connective tissue. Afterwards, the connective tissue was minced into small pieces (approximately 1 mm3) which were subsequently digested with a solution of 2 mg/ml collagenase (Sigma) for 40 min at 37°C. The tissue explants were then placed into 25 cm2 culture vessel containing α-MEM medium (Hyclone) supplemented with 15% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Hyclone) at 37°C in 5% CO2. Cells were subcultured at 80% confluency by 0.25% trypsin/EDTA solution (Gibco).

Flow cytometry

GMSCs (1 × 106) at passage 1 were washed with PBS and incubated with antibodies against human CD73, CD105, CD144, CD31, HLA-DR, Stro-1, CD34, CD44, CD45 (BioLegend), CD29 (eBioscience) at 4°C for 30 min in the dark. Then the cells were washed and resuspended in 1% paraformaldehyde for flow cytometry analysis with the use of CXP Analysis 2.1 software (Beckman Coulter).

Enhanced green fluorescent protein transfection of GMSCs

To directly trace the fate of transplanted GMSCs in vivo, the lentiviral vector with enhanced green fluorescent protein (pLV.Ex2d.P/neo-EF1A>eGFP; Cyagen, China) was used to label GMSCs. The first-passage GMSCs (5 × 103 cells/cm2) were incubated in 6-well plates for approximately 24 h. Then the culture medium was removed and concentrated viral supernatant diluted in serum-free α-MEM was added. 8 hours later, the viral supernatant was replaced with complete culture medium. Transfected cells were selected with G418 (100 μg/ml). The GFP+ GMSCs were expanded and cells from third to fifth passage were used for in vivo experiments.

Colony-forming unit-fibroblasts (CFU-F) assay

To assess colony-forming efficiency of GMSCs, CFU-F assay was performed as described previously [15]. A total of 500 GMSCs at passage 1 were seeded into 6-CM cell culture dish. The culture medium (α-MEM with 10% FBS) was replaced every 3 days. After 10 days of cultivation, all cultures were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde, stained with 0.1% crystal violet and then washed twice with distilled water. Aggregates of more than 50 cells were counted as a colony under the microscope.

In vitro multipotent differentiation

Adipogenic differentiation: The fourth-passage GMSCs (5 × 103 cells/cm2) were incubated in 96-well plates in α-MEM growth media. 24 h later, the culture medium was replaced with adipogenic induction medium supplemented with α-MEM containing 10% FBS, 1 μM dexamethasone (Sigma), 200 μM indomethacin (Sigma), 10 μM insulin (Sigma), 0.5 mM isobutyl-methylxanthine (Sigma), and 1% antibiotic/antimycotic. Two weeks later, Oil Red O staining was performed to detect the formation of oil globules.

Osteogenic differentiation

As described above, cells plated in 24-well plates were incubated in α-MEM medium containing 5% FBS, 10 mM β-glycerophosphate (Sigma), 50 mg/ml ascorbate-2-phosphate (Sigma) and 0.1 μM dexamethasone. The media was changed twice weekly. Four weeks later, mineral deposition was identified by Alizarin Red S (Sigma-Aldrich) staining.

Chondrogenic differentiation

As described above, GMSCs seeded in 6-well plates were cultured in chondrogenic induction medium supplemented with α-MEM containing 10% FBS, 50 nM ascorbate-2-phosphate, 10 ng/mL TGF-β1 (Sigma), and 0.1 μM dexamethasone. The medium was changed twice weekly. Three weeks later, toluidine blue staining was performed to detect glycosaminoglycan production.

Animal surgery and GMSCs transplantation

As described previously [16], a bone defect with 1.5-mm in diameter in the right mandibular body were created in the 8-week-old C57BL/6J mice. The defect was sited below the mesial root of the lower first molar and drilled with a dental bur under continuous irrigation with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). Animals were randomly divided into group A and B, with 18 mice in each group. The GFP+ GMSCs were re-suspended in 100 μl of α-MEM and transplanted into mice in group A by tail vein injection with a very slow speed [17]. Each recipient mouse received approximately 1 × 106 cells. Group B animals were injected with 100 μl α-MEM as control. Animals were sacrificed at 1, 2 and 3 weeks after transplantation.

Tissue preparation and histomorphometric analysis

Following perfusion fixation via the intracardiac route with 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA, Sigma) the right mandibular bone was removed. Then the samples were decalcified in 10% EDTA for 3 to 4 weeks, paraffin-embedded and cut into 3 μm-thick sections disto-mesially. Sections selected from the most central areas of the bone defect were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (HE) and Masson’s Ttichrome (MT). The slides were observed with light microscopy (Olympus, Japan) and photographed using the ProgRes CapturePro software (Jenoptik Optical Systems, Germany). Three HE-stained sections were analyzed morphometrically for each sample. The new bone formation area as a percentage of the total defect area was calculated with a soft package (Image-Pro Plus 6.0, USA) [18].

Homing assay

Nuclear staining was performed using DAPI. Briefly, the sections were rehydrated and washed with PBS for 5 min and stained with DAPI for 3 min. After washed with PBS, the slices were visualized by a fluorescent microscope (Leica, Germany) under × 400 magnification and image analysis was performed using Image J2x (Image J2x Software, USA). GFP+ cells counterstained with DAPI were examined.

Immunohistochemistry for GFP

Immunohistochemical study was performed using purified rabbit polyclonal antibody (GFP 1:200; Cell signaling, USA) against GFP. Dewaxed and hydrated sections were treated with 3% H2O2 for 10 min to quench endogenous peroxidase. Then the sections were incubated with the primary antibody at 4°C overnight, washed with PBS and incubated with the anti-rabbit secondary antibody (ZSGB-BIO, Beijing, China) at 37°C for 30 min. Counter staining was performed with Mayer’s hematoxylin. Control sections were incubated with normal rabbit serum without the primary antibody.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using a statistical package (SPSS 19.0, SPSS Inc, USA). Data were expressed as mean ± SD. Comparison of histomorphometry data for bone formation were analyzed by Independent-Samples T test. The statistical significance chosen was p < 0.05.

Results

Characterization of human GMSCs

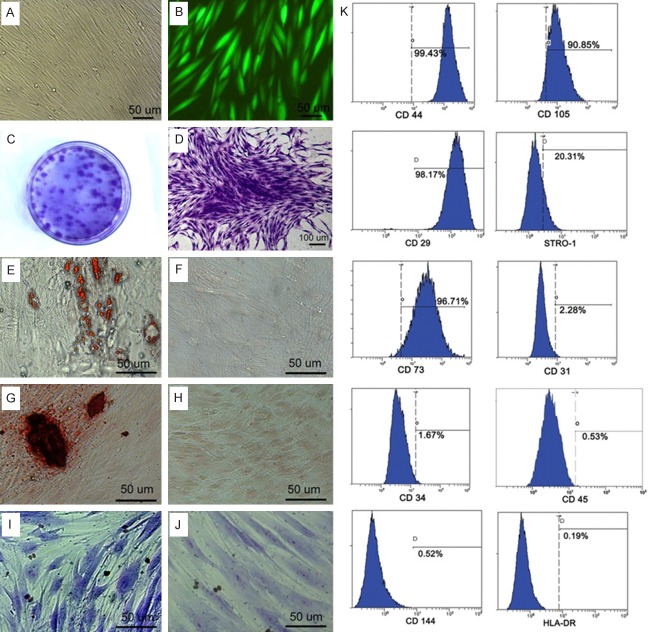

Human GMSCs isolated from healthy gingival appeared fibroblast-like spindle shape (Figure 1A) and were able to form clonogenic cell clusters confirmed by the CFU-F assay (Figure 1C, 1D). Flow cytometry analysis showed that the 1st generation GMSCs expressed CD73, CD105, CD29, CD44, and Stro-1 but not CD144, CD31, HLA-DR, CD34 and CD45 (Figure 1K). Strong expression of GFP could be detected 72 h post-transfection in GMSCs and GFP expressed stably accompanied the subculture of GMSCs (Figure 1B).

Figure 1.

Characterization of human GMSCs. A. In vitro culture of GMSCs. B. Expression of GFP in GMSCs cultured in vitro. C. CFU-F assay was carried out. D. Single-colony clusters derived from GMSCs showed typical fibroblastic morphology. E-J. Multipotent differentiation of GMSCs. E. Adipogenic differentiation of GMSCs detected by Oil Red O staining. F. GMSCs cultured under normal conditions detected by Oil Red O staining as control. G. Osteogenic differentiation of GMSCs identified by Alizarin Red S staining. H. GMSCs cultured under normal conditions detected by Alizarin Red S staining as control. I. Chondrogenic differentiation detected by toluidine blue staining. J. GMSCs cultured under normal conditions detected by toluidine blue staining as control. K. Flow cytometry analysis showed that human GMSCs expressed CD44, CD29, CD105, CD73 and STRO-1 but not CD34, CD45, CD31, CD144 and HLA-DR.

Multiple differentiation potential of human GMSCs

Cultured in adipogenic induction medium for 2 weeks, lipid-rich cells were detected by Oil Red O staining, which indicated GMSCs could differentiate into adipocytes (Figure 1E). Under osteogenic induction conditions for 4 weeks, GMSCs showed formation of mineralized nodules which were identified by Alizarin Red S staining (Figure 1G). After 3 weeks of culture in chondrogenic induction medium, GMSCs were observed an increase in size and blue stained in their cytoplasm using toluidine blue staining (Figure 1I). Whereas, no cells positive for Oil Red O staining, Alizarin Red S staining and toluidine blue staining were detected in the control group under normal noninduction conditions (Figure 1F, 1H and 1J). These findings suggest that human GMSCs have the potential to differentiate into bone, fat and cartilage.

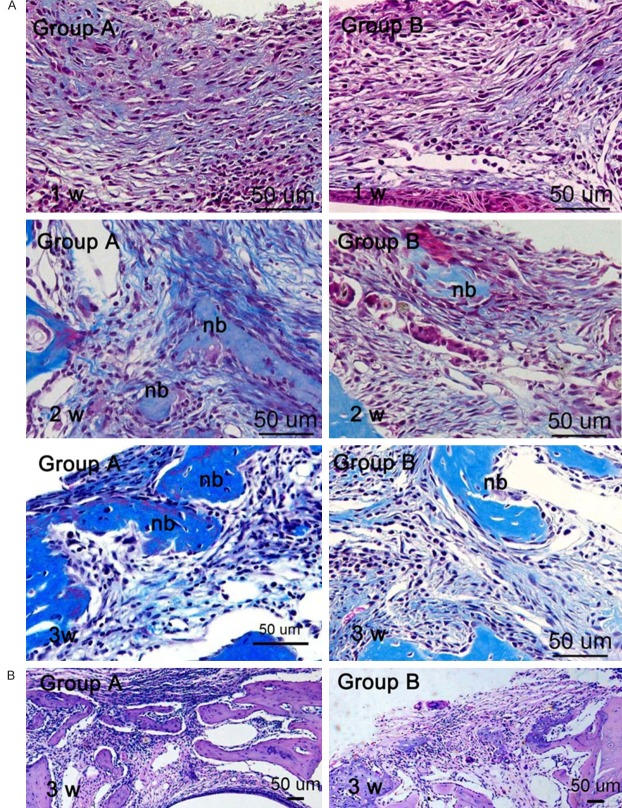

Histology observation and morphometric assessment of the bone defect

Histology changes were observed in the bone defect by HE and MT staining. In the 1st week post transplantation, no bone formation was detected in mandibular defect area of both groups. Abundant connective tissue was observed with plenty of fibroblast-like cells and a little newly formed collagen matrix distributed throughout the whole defect area. In the 2nd week post transplantation, the bone defect was rich in blue color by MT staining implying new collagen and bone formation. Some islands of osteoid were observed in the center of the bone defect and newly formed woven bone was present on the defect margins. At 3 weeks post transplantation, active bone formation was observed in both groups and mice in group A showed osteogenesis ability more strongly than those in group B (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Histological observation within the bone defects. A. Observation under × 400 magnification by MT staining. B. Low power view of the bone defects by HE staining.

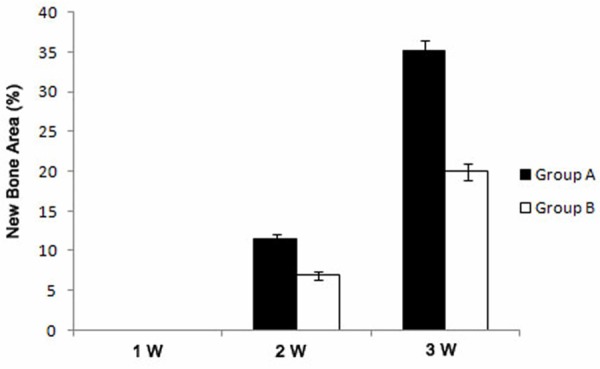

The newly formed bone area within mandibular defects at the 2nd and 3rd week was assessed in both groups. At 2 weeks after transplantation, the newly formed bone area in group A and B was 11.4% and 6.9% respectively. And at 3 weeks that was 35.2% and 20% respectively. Both at 2 weeks and 3 weeks after transplantation, the differences in bone formation between group A and B were all statistically significant, which indicated a significant effect of GMSCs transplantation on bone regeneration (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Analysis of newly formed bone tissue in the bone defects (mean ± SD, %). *p < 0.05.

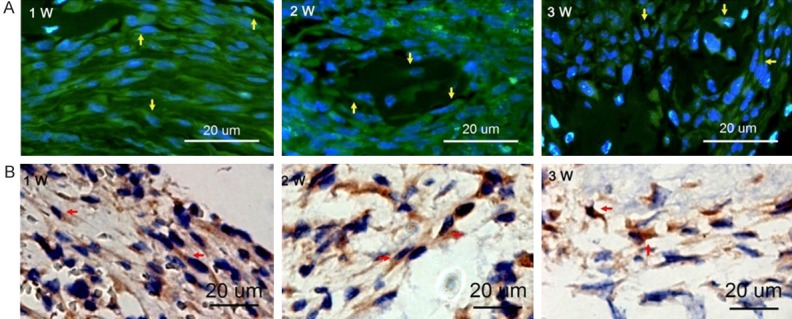

Homing properties of GMSCs

Both fluorescent microscope observation and immunohistochemical staining showed the existence of GFP+ cells in the bone defect, which indicated the transplanted GMSCs exhibited homing specificity and could survive in the bone defect (Figure 4). 1 week and 2 weeks after transplantation, a large number of GFP+ fibroblast-like cells were observed in the bone defect and at 3 weeks the number of donor cells decreased. GFP+ osteoblasts were identified in the surface and inside of newly formed bone at 2 and 3 weeks post transplantation.

Figure 4.

Detection of GFP+ GMSCs within the bone defect. A. Observation under fluorescence microscopy. Green cells counterstained with DAPI-stained nuclei in blue were detected (as yellow arrowheads indicated). B. Immunohistochemical staining for GFP. Expression Of GFP was intense (as red arrowheads indicated).

Discussion

Stem-cell-based therapies aiming at reconstruction of bone injuries have been a promising alternative for clinical trial [19]. As novel postnatal stem cells, GMSCs have been paid extensive attention for their therapeutic potential in regenerative medicine [9,10]. GMSCs can be easily isolated from human gingival tissue which is usually discarded as biological waste in the clinic and proliferate rapidly in vitro to meet the transplantation requirement for cell amount. In this study, GMSCs were positive for MSC-associated surface markers such as CD73, CD105, CD29, CD44 and Stro-1 and negative for hematopoietic stem markers (CD34 and CD45) and endothelial cells markers (CD144 and CD31). Moreover, GMSCs were negative for HLA-DR indicating the applicability for allogeneic stem cell transplantation. We also found GMSCs had self-renewal capacity and showed multiple differentiation potential, which were consistent with previous studies showing that GMSCs possessed the basic characteristics of mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) [5,10].

In our previous study we demonstrated systemically delivered BMSCs can home to the mandibular bone defect in mice and provide therapeutic benefits [14]. However, up to date no study has been reported to evaluate the contribution of GMSCs migrating from peripheral circulation to bone regeneration though local application of GMSCs showed great promotion to the bone healing [10]. Therefore, we designed a study to explore the capacity of systemically transplanted GMSCs to promote bone regeneration. We labeled GMSCs with GFP to directly trace the fate of transplanted GMSCs in vivo. The results of fluorescent microscope observation and immunohistochemical staining showed GFP+ fibroblast-like cells were detected within bone defects at 1, 2, 3 weeks post transplantation, which were consistent with previous demonstrations that MSCs have a tendency to home to the sites of injury [11-13]. We also detected GFP+ osteoblasts in the newly formed bone area in the 2nd and 3rd week post transplantation. These findings strongly supported our hypothesis that systemically transplanted GMSCs can be employed in bone regeneration in vivo.

The contribution of GMSCs to bone regeneration was confirmed by histology observation and morphometric assessment of the bone defect in the present study. As we found, at 2 and 3 weeks post transplantation, the newly formed bone area in Group A mice was significantly higher than that in Group B mice. In addition to the osteogenenic potential of GMSCs to promote the new bone forming, another possible explanation responsible for the therapeutic effects of GMSCs on bone injuries was the transplanted GMSCs triggered the endogenous MSCs recruitment which is known to be crucial for successful bone repair [2,16], though the mechanisms of MSCs recruitment to the injury sites were unclear.

Stem-cell-based therapies have been a promising alternative for bone regeneration. Selection of appropriate donor cell types plays an important role in successful cell transplantation. The present study provides evidence that systemically transplanted GMSCs can not only home to the mandibular defect but also promote bone regeneration. Given the basic characteristics of MSCs and advantages such as ease of isolation, high proliferation capacity, uniformly homogenous property, and so on, GMSCs are considered as an ideal candidate cell resource for cell-based therapies. Future studies using large animal models are needed to assess the long-term safety and efficacy of GMSCs for bone regeneration.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by grants from Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 81271141) to PY.

Disclosure of conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- 1.Schindeler A, McDonald MM, Bokko P, Little DG. Bone remodeling during fracture repair: The cellular picture. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2008;19:459–466. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2008.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Griffin M, Iqbal SA, Bayat A. Exploring the application of mesenchymal stem cells in bone repair and regeneration. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2011;93:427–434. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.93B4.25249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pagni G, Kaigler D, Rasperini G, Avila-Ortiz G, Bartel R, Giannobile W. Bone repair cells for craniofacial regeneration. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2012;64:1310–1319. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2012.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stenderup K, Justesen J, Clausen C, Kassem M. Aging is associated with decreased maximal life span and accelerated senescence of bone marrow stromal cells. Bone. 2003;33:919–926. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2003.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tomar GB, Srivastava RK, Gupta N, Barhanpurkar AP, Pote ST, Jhaveri HM, Mishra GC, Wani MR. Human gingiva-derived mesenchymal stem cells are superior to bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells for cell therapy in regenerative medicine. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2010;393:377–383. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2010.01.126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Akiyama K, Chen C, Gronthos S, Shi S. Odontogenesis. Springer; 2012. Lineage differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells from dental pulp, apical papilla, and periodontal ligament; pp. 111–121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mitrano TI, Grob MS, Carrión F, Nova-Lamperti E, Luz PA, Fierro FS, Quintero A, Chaparro A, Sanz A. Culture and characterization of mesenchymal stem cells from human gingival tissue. J Periodontol. 2010;81:917–925. doi: 10.1902/jop.2010.090566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhang Q, Shi S, Liu Y, Uyanne J, Shi Y, Shi S, Le AD. Mesenchymal stem cells derived from human gingiva are capable of immunomodulatory functions and ameliorate inflammation-related tissue destruction in experimental colitis. J Immunol. 2009;183:7787–7798. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0902318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fawzy El-Sayed KM, Paris S, Becker ST, Neuschl M, De Buhr W, Sälzer S, Wulff A, Elrefai M, Darhous MS, El-Masry M, Wiltfang J, Dörfer CE. Periodontal regeneration employing gingival margin derived stem/progenitor cells: an animal study. J Clin Periodontol. 2012;39:861–870. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2012.01904.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang F, Yu M, Yan X, Wen Y, Zeng Q, Yue W, Yang P, Pei X. Gingiva-derived mesenchymal stem cell-mediated therapeutic approach for bone tissue regeneration. Stem Cells Dev. 2011;20:2093–2102. doi: 10.1089/scd.2010.0523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ortiz LA, Gambelli F, McBride C, Gaupp D, Baddoo M, Kaminski N, Phinney DG. Mesenchymal stem cell engraftment in lung is enhanced in response to bleomycin exposure and ameliorates its fibrotic effects. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:8407–8411. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1432929100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jackson JS, Golding JP, Chapon C, Jones WA, Bhakoo KK. Homing of stem cells to sites of inflammatory brain injury after intracerebral and intravenous administration: a longitudinal imaging study. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2010;1:17. doi: 10.1186/scrt17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Li S, Tu Q, Zhang J, Stein G, Lian J, Yang PS, Chen J. Systemically transplanted bone marrow stromal cells contributing to bone tissue regeneration. J Cell Physiol. 2008;215:204–209. doi: 10.1002/jcp.21302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Xu QC, Hao PJ, Yu XB, Chen SL, Yu MJ, Zhang J, Yang PS. Hyperlipidemia compromises homing efficiency of systemically transplanted BMSCs and inhibits bone regeneration. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2014;7:1580. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.DiGirolamo CM, Stokes D, Colter D, Phinney DG, Class R, Prockop DJ. Propagation and senescence of human marrow stromal cells in culture: a simple colony-forming assay identifies samples with the greatest potential to propagate and differentiate. Br J Haematol. 1999;107:275–281. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.1999.01715.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhang J, Tu Q, Grosschedl R, Kim MS, Griffin T, Drissi H, Yang P, Chen J. Roles of SATB2 in osteogenic differentiation and bone regeneration. Tissue Eng Part A. 2011;17:1767–1776. doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2010.0503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lode HN, Xiang R, Pertl U, Förster E, Schoenberger SP, Gillies SD, Reisfeld RA. Melanoma immunotherapy by targeted IL-2 depends on CD4+ T-cell help mediated by CD40/CD40L interaction. J Clin Invest. 2000;105:1623–1630. doi: 10.1172/JCI9177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kim BJ, Kwon TK, Baek HS, Hwang DS, Kim CH, Chung IK, Jeong JS, Shin SH. A comparative study of the effectiveness of sinus bone grafting with recombinant human bone morphogenetic protein 2-coated tricalcium phosphate and platelet-rich fibrin-mixed tricalcium phosphate in rabbits. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol. 2012;113:583–592. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2011.04.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rose FR, Oreffo RO. Bone tissue engineering: hope vs hype. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2002;292:1–7. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2002.6519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]