Abstract

Patient: Male, 23

Final Diagnosis: Corynebacterium diphtheriae endocarditis

Symptoms: Abdominal pain • cachexia • diarrhea • fever • vomiting

Medication: —

Clinical Procedure: Mitral valve replacement

Specialty: Surgery

Objective:

Rare disease

Background:

Although Corynebacterium diphtheriae is well known for causing diphtheria and other respiratory tract infections, in very rare cases it can lead to severe systemic disease.

Case Report:

This is a case of a previously healthy young man (no prosthetic valve in situ or other known congenital defect), presenting with a Corynebacterium diphtheriae infection leading to endocarditis. The patient reported no I.V. drug use, so it can be assumed that no risk factors for infective endocarditis were present.

Conclusions:

This report aims to raise suspicion for this specific infection in order to proceed with the right treatment as soon as possible.

MeSH Keywords: Diphtheria, Corynebacterium diphtheriae, Embolism, Endocarditis

Background

Corynebacterium diphtheriae infection is rather rare, mostly due to early vaccination against the pathogen. Even more rare is the cardiac involvement, in cases of severe systemic disease. Further difficulties in suspicion of the disease include the microbiological similarity to other pathogens, which may delay the diagnosis. This appears to be a significant issue, as the wrong diagnosis may lead to further deteriotation of the patients’ status, and also to the performance of surgical therapies, that would not be necessary, if the diagnosis had been made earlier.

Case Report

A 23-year-old patient was admitted to our hospital with general symptoms, including abdominal pain, vomiting, diarrhea, cachexia, and fever up to 40°C with rigors. Although the symptoms persisted for about 40 days and the patient had visited the A&E department several times, he was repeatedly discharged with the diagnosis of flu-like symptoms.

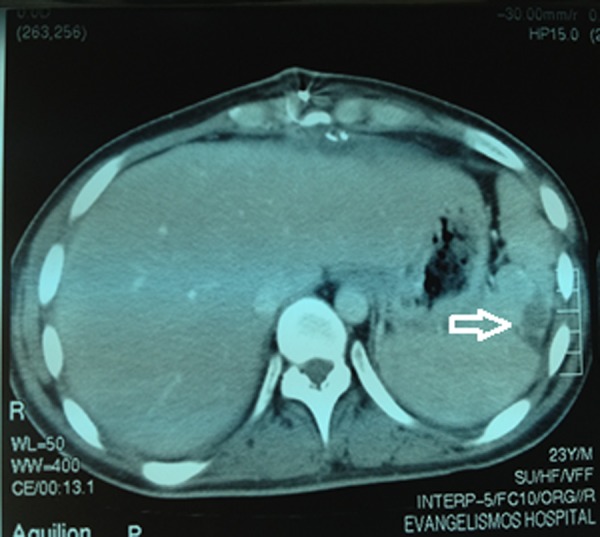

Upon physical examination, the patient was tachycardic and auscultation revealed a systolic murmur (2–3/6) at the auscultation site of the mitral valve. The abdomen was painful but not rigid at palpation, no guarding was present, and bowel sounds were reduced. ECG showed sinus rhythm. A chest-abdomen computed tomography (CT) scan showed multiple spleen embolisms (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Arrow demonstrates splenic septic emboli.

Transthoracic echocardiography revealed multiple mitral valve vegetations. The working diagnosis was infective endocarditis and after 3 sets of blood cultures were taken, antibiotics were administered (vancomycin and gentamicin). Two out of 3 blood cultures were positive for Kocuria kristinae, a gram-positive micrococcus. The antibiogram indicated that Kocuria kristinae was resistant to oxacillin and despite the fact that it was sensitive to penicillin, cross-resistance to b-lactams was suspected. Also, the patient showed no signs of improvement with the medication, so continuation of vancomycin, withdrawal of gentamicin, and administration of rifabicin and ciprofloxacin (with the indication of spleen abscesses) were implemented. The medication was not well tolerated, leading to the substitution of ciprofloxacin and rifabicin by levofloxacin.

Despite the treatment, no signs of improvement were noticed after 2 weeks, so vancomycin levels were checked but appeared within therapeutic range. The patient showed further deterioration and developed respiratory failure. Antibiotic administration was once again changed, this time to linezolid and levofloxacin. Chest CT scan was done, since there was high suspicion for pulmonary (septic) embolism. The CT scan was negative and the patient was also treated with I.V. furosemide 3 times daily for pulmonary edema. A new echo-cardiogram revealed aggravation, with findings such as left atrium dilatation, open foramen ovale, and severe mitral regurgitation (with convergence gap), which were not present on the first echocardiogram. Diuretic treatment led to significant and rapid improvement, so furosemide was reduced to once daily and spironolactone (25 mg once daily) was added. The transesophageal echocardiogram showed no chordae rupture. Improvement of the pulmonary edema was also confirmed by multiple chest x-rays.

The cardiac surgery department was contacted and an operation was scheduled for a date by which antibiotic treatment would have been terminated. In the meantime, PCR of the culture (in contrast to blood cultures) indicated Corynebacterium diphtheriae (100%) infection, and that led to another switch of antibiotics, this time to penicillin G, azithromycin, and gentamicin, according to the microbiologist’s advice. Improvement continued (normal CRP levels) and there was no fever, but a week later acute pulmonary edema presented with hypotension and signs of severe heart failure. An emergency echo-cardiogram showed further deterioration of the mitral convergence gap and severe heart failure (PASP 70 mmHg). The patient was started on high I.V. furosemide and was urgently transferred to the cardiothoracic department for a mitral valve replacement. A mechanical valve was inserted (Mechanical 27 mm Sorin Group®) and the operation was successful.

Discussion

Systemic disease caused by C. diphtheriae is very rare, and is even more rarely recognized and presented in the literature. Our case is one of the very few cases of reported endocarditis with C. diphtheriae being the proven pathogen (with PCR). No other congenital abnormalities or risk factors were found. This is also the first such case presented in Greece. Furthermore, the misjudgment by the microbiology lab regarding the pathogen from the blood culture (micrococcus instead of C. diphtheriae) reflects the rarity and the lack of experience in growing such bacteria in positive blood cultures, as well as the possible similarity in terms of visual characteristics (both are gram-positive, catalase-positive microorganisms, with the difference that micrococci are cocci and C. diphtheriae is bacilli) [1–3]. The report of this case may increase suspicion of this infective cause of endocarditis and help microbiology departments in reaching the right diagnosis. In this particular case, the correct assessment of the cultures could have led to administration of the right antibiotic treatment from the beginning or even help avoid the valve replacement, but the evidence does not suggest that the right medical treatment is related to better outcome or necessity of surgery [4].

It is also important to mention that the patient experienced a tremendous delay in the diagnosis of his disease and initiation of his treatment because of the general, flu-like symptoms that he presented for a long time, and which the doctors failed to relate to a severe disease such as infective endocarditis. C. diphtheriae does not have a particularly aggressive behavior and the manifestation of this infection is rather unremarkable. Nevertheless, cases with persistent symptomatology should trigger suspicion and further investigation. This report provides a good example of such a case [5–7].

Conclusions

This case shows that Corynebacterium diphtheriae can cause a systemic disease such as infective endocarditis even under normal circumstances (native valve). It is very important for all clinicians, as well as microbiologists, to have a high level of suspicion and an open mind regarding uncommon causes of such infections. This would possibly reduce the time wasted before diagnosing the disease, as well as the delay in initiating therapy (antimicrobial or surgical).

Moreover, it is important to mention that systemic diseases caused by low-infectiousness bacteria like Corynebacterium diphtheriae may present with general and non-specific symptoms like those of this case. A high level of suspicion from the doctors is required in order to diagnose it at an early stage, especially if the symptoms persist for a long time.

References:

- 1.Efstratiou A, Maple C. Diphitheria Manual for the laboratory diagnosis of diphtheria. Copenhagen: WHO; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Isaac-Renton JL, Boyko WJ, Chan R, Crichton E. Corynebacterium diphtheriae septicemia. Am J Clin Pathol. 1981;75:631–34. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/75.4.631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wilson APR. Treatment of infection caused by toxigenic and non-toxigenic strains of Corynebacterium diphtheriae. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1995;35:717–20. doi: 10.1093/jac/35.6.717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mishra B, Dignan RJ, Hughes CF, Hendel N. Corynebacterium Diphtheriae Endocarditis – Surgery for Some but not All. Asian Cardiovasc Thorac Ann. 2005;13(2):119–26. doi: 10.1177/021849230501300205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gruner E, Opravil M, Altwegg M, von Graevenitz A. Nontoxigenic Corynebacterium diphtheriae isolated from intravenous drug users. Clin Infect Dis. 1994;18:94–96. doi: 10.1093/clinids/18.1.94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Huber-Schneider C, Gubler J, Knoblauch M. [Endocarditis due to Corynebacterium diphtheriae cause by contact with intravenous drugs: report of 5 cases] Schweiz Med Wochenschr. 1994;124:2173–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. NCCLS. Document M2-A8. 8. NCCLS: USA; 2003. Performance standards for antimicrobial disk susceptibility tests; Approved standard.