Abstract

Hard ticks, family Ixodidae, are divided into two groups, the Metastriata and the Prostriata, based on morphological differences. In the United States, there are four medically important genera of the Ixodidae: Ixodes, Amblyomma, Dermacentor, and Rhipicephalus. Ixodes is the only genus in and representative of the Prostriata, whereas the latter three genera are members of the Metastriata. All developmental stages of the Prostriata can be easily differentiated from the Metastriata using morphology. Similarly, the three Metastriate genera are highly identifiable as adults, yet as immatures, the discriminating characteristics can be difficult to use for differentiation, especially if the specimens are damaged or engorged with blood. All three Metastriate genera represent medically important vectors, thus accurate differentiation is necessary. To this end, we have developed a multiplexed-PCR diagnostic assay that, when combined with RFLP analysis will differentiate between the Metastriate genera—Amblyomma, Dermacentor, Rhipicephalus, and Haemaphysalis based on the length of the PCR amplicon and subsequent restriction digestion profile. The intended use for this diagnostic is to verify morphological identifications, especially of immatures, as well as to identify samples destroyed for molecular analysis, which will lead to more accurate field data as well as implication of vectors in disease transmission.

Keywords: Metastriate, Amblyomma, Dermacentor, Haemaphysalis, Rhipicephalus, diagnostic

Introduction

The family Ixodidae, or hard ticks (Arachnida: Acari: Parasitiformes) consists of 694 species divided into two main morphological and phylogenetic groups: the Prostriata and the Metastriata (Sonenshine 1991). The Prostriata are represented by the single subfamily Ixodinae that consists of one genus, Ixodes. In contrast, the Metastriata consists of five subfamilies; Amblyomminae, Haemaphysalinae, Hyalomminae, Rhipicephalinae, Bothriocrotoninae (Black and Piesman 1994,Klompen et al. 2002). Of the thirteen described genera in the Metastriata, seven have species that are implicated in disease transmission (Hoogstraal and Wassef 1986). All Ixodidae are hematophagous and obligate ectoparasites.

Medically important species are represented in several genera of hard ticks found in the United States, including Ixodes, Amblyomma, Dermacentor, Rhipicephalus and Haemaphysalis (Walker 1998). Of these genera, Ixodes is the largest, with more than 200 recognized species. Ixodes scapularis, the black-legged tick, is probably the most recognized species of this genus and serves as the vector of Lyme disease, human babesiosis, granulocyctic ehrlichiosis and Powassan encephalitis virus in North America.

The most frequently encountered representative of the genus Dermacentor in the eastern United States is D. variabilis, the American dog tick. This species is implicated in the transmission of numerous species of Rickettsia, including the etiologic agent of Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever (RMSF) and can cause tick paralysis. Dermacentor andersoni, the Rocky Mountain wood tick, as its name suggests is not common on the east coast, and is primarily found in the western United States. This tick has been implicated as the vector of the agents that cause RMSF, Colorado tick fever, bovine anaplasmosis and Tularemia (Walker 1998). The Pacific coast tick, D. occidentalis, is restricted to the Pacific lowlands from Oregon to Baja California and is a natural vector for Anaplasma marginale Theiler. Unlike the previously mentioned Dermacentor species, the winter tick, D. albipictus, is a one host tick, completing its life cycle on white tailed deer (Odocoileus virginianus) and other large ungulates. While common in the Mid-Atlantic region D. albipictus is not associated with human disease transmission, but does vector bovine anaplasmosis (Stiller et al. 1981).

The most common Amblyomma tick in the eastern and mid-Atlantic United States is Amblyomma americanum, the Lone Star tick, which has been reported to vector Ehrlichia chaffeensis (Dumler and Bakken 1998) and the pathogens that cause tularemia and Q fever (Parola and Raoult 2001). Another Amblyomma species, A. maculatum, the Gulf Coast tick, is one of several vectors of Cowdria ruminantium Cowdry, the causative agent of the veterinary illness, heartwater, and is usually found on large animals (Uilenburg 1982). This tick is primarily found along the southern coastline between the Atlantic and Gulf Coast and is only occasionally found in more inland locations (Bishop and Hixson 1936, Harrison et al. 1997). Although considered a serious economic pest, no known human disease transmission is associated with A. maculatum.

The brown dog tick, Rhipicephalus sanguineus, is not as common but is occasionally found in the mid-Atlantic region and can vector canine babesia, Texas cattle fever, and canine hepatozoonosis (Ewing et al. 2000). Haemaphysalis leporispalustris, the rabbit tick, as its name suggests, primarily feeds on rabbits and birds and is not usually anthropophilic. While it has been speculated that this tick may vector several agents and serve as a potential bridge vector for RMSF, it does not appear to be a major vector for human pathogens (Goethert and Telford 2003).

Morphologically, these five tick genera are easily identifiable as adults. In the nymphal and larval stages the anal groove, the cuticular fold found near the anal aperture, clearly differentiates the Prostriata, with the groove anterior to the anus, from the Metastriata, on which the anal groove is either posterior to the anal aperture or is absent. Among the Metastriate, differentiation of nymphal and larval ticks has proven more difficult, especially if partially or fully engorged, or if the specimen is damaged or morphologically incomplete. A common dichotomous key used for the identification of ticks found in the northeast United States (Sonenshine 1979) is a useful guide for distinguishing hard ticks. However, many distinguishing characteristics are difficult to locate or identify in immature specimens, especially by those untrained in acarine taxonomy. For those unfamiliar with the taxa, the Metastriate immatures become especially difficult to differentiate and may be mis-identified. This problem is often compounded during molecular surveys for pathogens or genetic analysis, as the entire immature specimens are often destroyed. Therefore, an alternative method for rapid and accurate identification of Metastriate immatures is needed, especially for verification of specimen identification post-processing.

Mitochondrial and nuclear DNA has been used extensively to conduct phylogenetic studies (Black and Piesman 1994, Crampton et al. 1996, Black et al. 1997, Klompen et al. 1996, Norris et al. 1997, Dobson and Barker 1999), to check the validity of species designations (Wesson et al. 1993, Caporale et al. 1995, Norris et al. 1997), and in population genetic studies of Ixodid ticks (Rich et al. 1995, Norris et al. 1996). In each of these studies, PCR has been employed using specifically designed primer sets (Sparagano et al. 1999). The PCR product is then sequenced or screened using techniques such as single-strand confirmation polymorphism (SSCP) analysis, and nucleotide insertion, deletion or point mutations are then used to distinguish one species from another (Hiss et al. 1994, Qiu et al. 2002). These procedures can be both time consuming and costly. This study describes a novel PCR-RFLP based assay to clearly differentiate between the four most common Metastriate tick genera in the United States: Dermacentor, Amblyomma, Rhipicephalus, and Haemaphysalis.

Methods and Materials

Tick material

Ixodes scapularis, D. variabilis, and A. americanum adults were collected by standard flagging techniques. Collections were made during the spring, summer and fall of 2001 at various locations in central and southern Maryland. Voucher specimens of I. scapularis, D. variabilis, R. sanguineus, and A. americanum nymphs and larvae, and adult D. occidentalis were kindly provided from colonies maintained at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (Atlanta, GA). Voucher specimens of adult D. andersoni, larval D. albipictus, and adult A. americanum were graciously provided by G. Scoles (USDA, Washington State University, Pullman, WA). Specimens representing R. sanguineus, A. maculatum, and H. leporispalustris were purchased from the tick rearing facility at Okalahoma State University (Stillwater, OK). Several archived specimens of adult and nymph D. albopictus were provided by J.R. Keirans (Institute of Arthropodology and Parasitology, Georgia Southern University, Statesboro, GA).

PCR primer design and RFLP analysis

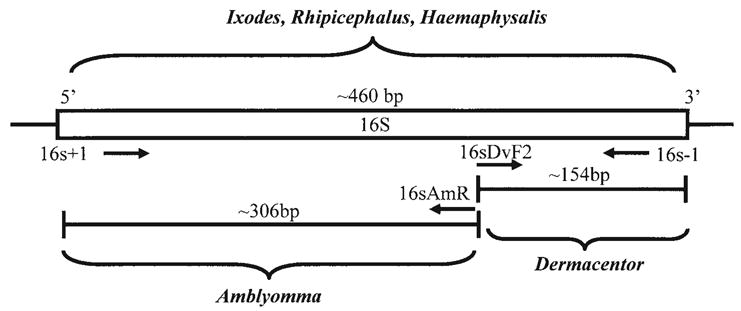

External primers employed in this study have been previously described (Black and Piesman 1994, Norris et al. 1996). Novel, internal, genus-specific primers were designed using a representative sample of previously published 16S sequences from GenBank for representative species of Dermacentor, Amblyomma, Rhipicephalus, Haemaphysalis and Ixodes tick (Table 1). The sequences were aligned using a multiple pairwise alignment program (MegAlign, DNAStar, Madison, WI). Analysis of the alignment revealed a 24-bp region which appeared to differentiate the major genera (Table 1). Two internal primers, 16sDvF2 and 16sAmR, were designed to amplify Dermacentor and Amblyomma species, respectively (Table 2, Fig. 1). The internal primers were manually selected with the assistance of Primer 3 (Rozen and Skaletsky 2000) to calculate Tm and primer compatibility.

Table 1. Tick Species, Genbank Accession Numbers Of Sequence Data Used To Design Diagnostic Primers, and Alignment Of Priming Region For Each Species.

| Species | Origin | Accession number | 16sDvF primer (nt 334–360) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dermacentor | AATGA-TTATTTGA-GAAAAATAC | |||

| D. albipictus | CA, USA | AF001231 | .....-.......-..-....... | Crosbie et al., 1998 |

| D. albipictus | WA, USA | AF001232 | . G...-. C.....-.. A....... | Crosbie et al., 1998 |

| D. albipictus | WA, USA | AF001233 | .....-. A.....-.. A....... | Crosbie et al., 1998 |

| D. albipictus | VA, USA | AY676458 | .....-. A..... G. G-....... | Unpublisheda |

| D. andersoni | KS, USA | L34299 | .....-. A......- TA....... | Black & Piesman, 1994 |

| D. halli | TX, USA | AF001247 | .....-........ A.-....... | Crosbie et al., 1998 |

| D. hunteri | CA, USA | AF001246 | .....-.... C...- A-....... | Crosbie et al., 1998 |

| D. imitans | Venezuela | AF001248 | .....-. A......-. A....... | Crosbie et al., 1998 |

| D. marginatus | unknown | Z97879 | .....-.... A...-......... | Mangold et al., 1997 |

| D. nitens | ID, USA | AF001249 | . T...-. A. C.... A......... | Crosbie et al., 1998 |

| D. occidentalis | CA, USA | AF001252 | .....-. A...... A.-....... | Crosbie et al., 1998 |

| D. variabilis | KS, USA | L34300 | .....-..........-....... | Black & Piesman, 1994 |

| D. variabilis | CA, USA | AY010235 | .....-. A.....-.. A....... | de la Fuenta et al., 2001 |

| D. variabilis | FL, USA | AY010237 | .....-..........-....... | de la Fuenta et al., 2001 |

| D. variabilis | VA, USA | AY010241 | .....-. C........-....... | de la Fuenta et al., 2001 |

| D. variabilis | ID, USA | AY010238 | .....-. A..... G.. A....... | de la Fuenta et al., 2001 |

| Haemaphysalis | ||||

| H. cretica | Iseral | L34308 | .....-.. T. A...-. A....... | Black & Piesman, 1994 |

| H. inermis | Slovak Rep | U95872 | .....-.... A... TT--...... | Norris, et al., 1999 |

| H. leporispalustris | Georgia | L34309 | .....-........-. T....... | Black & Piesman, 1994 |

| H. punctata | unknown | Z97880 | .....- A.. AA...-. T....... | Mangold et al., 1997 |

| Rhipicephalus | ||||

| R. appendiculatus | UK | L34301 | .....-... AA...--........ | Black & Piesman, 1994 |

| R. bursa | unknown | AJ002956 | .....-.... A...-.-....... | Marquez et al., 1997 |

| R. pusillus | unknown | AJ002957 | .....-... CA.. T--- T...... | Marquez et al., 1997 |

| R. sanguineus | Iseral | L34302 | .....-.... A.. T--- T...... | Black & Piesman, 1994 |

| R. sanguineus | unknown | Z97884 | .....-.... A.. T--- T...... | Mangold et al., 1997 |

| R. turanicus | Isreal | L34303 | .....-.... A.. T--- T...... | Black & Piesman, 1994 |

| Amblyomma | .. C. G- AC. C... G.-........ | |||

| A. americanum | KS, USA | L34313 | .. C. G- AC. C... G.-........ | Black & Piesman, 1994 |

| A. americanum | TX, USA | L34314 | . GC. G-. A. A... G- T........ | Black & Piesman, 1994 |

| A. cajennesse | OK, USA | L34317 | .... G-. A. AA...-......... | Black & Piesman, 1994 |

| A. glauerti | Australia | U95853 | . T.. G-........ A......... | Norris et al., 1999 |

| A. maculatum | OK, USA | AY676459 | . T.. G-.................. | Unpublisheda |

| A. macuatum | OK, USA | L34318 | . T.. G-... GA...- T........ | Black & Piesman, 1994 |

| A. ovale | Paraguay | AF541255 | . T.. G-... AA... AT........ | Guglielmone et al., 2003 |

| A. tuberculatum | GA, USA | U95856 | Norris, et al., 1999 | |

| Ixodes | . GA..-... AA...-......... | |||

| Ixodes scapularis | NC, USA | L43863 | .....-.......-..-....... | Black & Piesman, 1994 |

| 16sAmR Primer (nt 339–360) | ||||

| Amblyomma | CGG-ACACTTGG-AAAAAATAC | |||

| A. americanum | Brazil | AF541254 | G..- TA. AA.. A-TC....... | Guglielmone et al., 2003 |

| A. americanum | KS, USA | L34313 | ...-........-......... | Black & Piesman, 1994 |

| A. americanum | TX, USA | L34314 | ...-........-......... | Black & Piesman, 1994 |

| A. cajennesse | OK, USA | L34317 | ...- TA. A....- T........ | Black & Piesman, 1994 |

| A. glauerti | Australia | U95853 | T..- TA. AA.. A--........ | Norris, et al., 1999 |

| A. maculatum | OK, USA | AY676459 | T..- TT. T... A--G....... | Unpublisheda |

| A. macuatum | OK, USA | L34318 | T..- TT.T... A--........ | Black & Piesman, 1994 |

| A. ovale | Paraguay | AF541255 | T..- TT. GA.. A.AT....... | Guglielmone et al., 2003 |

| A. tuberculatum | GA, USA | U95856 | T..- TT. AA.. AA.T....... | Norris, et al., 1999 |

Species in bold were tested in this analysis. nt, nucleotide position based on the full-length 16S rRNA fragment.

Newly sequenced tick isolate used to optimize the PCR primers for the multiplex PCR analysis.

Table 2. Primers Used In The Multiplexed PCR.

| Primer | Sequence 5′→3′ | Genus |

|---|---|---|

| 16S+1 | CTGCTCAATGATTTTTTAAATTGCTGTGG | All |

| 16S−1 | CCGGTCTGAACT AGATCAAGTa | All |

| LR-J-12887 (Simon et al. 1994) with an A substitution at position 20 | ||

| 16SAmr | GTATTTTTTCCAAGTGTCCG | Amblyomma |

| 16SDvF2 | AATGATWATTTGRGRAAAATAC | Dermacentor |

LRJ, etc.

Fig. 1.

Schematic of the multiplex primer combination with predicted amplification product size.

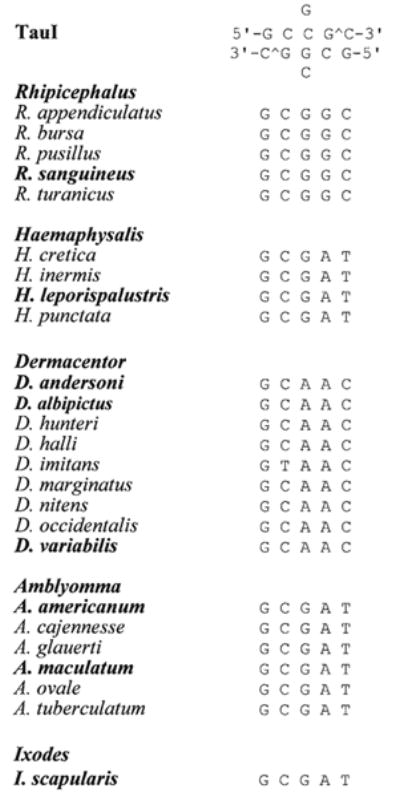

To differentiate Rhipicephalus from Haemaphysalis ticks, restriction enzyme recognition sites along the mitochondrial 16S gene were mapped using a world wide web based Restriction Mapper program (www.restrictionmapper.org). Using the previously described 16S ribosomal DNA alignment of various tick species, only enzymes which would cut either Rhipicephalus or Haemaphysalis, but not both, were chosen for further evaluation.

DNA extraction and amplification

Adult ticks were surface sterilized and bisected medially with a sterile scalpel, maintaining one half at −80°C as a voucher and utilizing the other half for genomic DNA extraction. DNA was extracted from ticks by modified hexadecyltrimethylammonium bromide (CTAB) DNA extraction (Johnson et al. 1992, Black et al. 1997). The described CTAB homogenization was followed by a phenol/chloroform/isoamyl alcohol (25:24:1) extraction, a chloroform/isoamly alcohol (24:1) extraction, isopropanol precipitation, and resuspension in 50 μL of HPLC grade H2O or 0.5 × TE buffer. Nymphal and larval ticks were extracted utilizing the same methods but using the entire specimen and were resuspended in 30 μL of HPLC H2O or 0.5 × TE buffer. All extractions were held at −20°C when not in use. Multiplexed PCR was performed using the four primers described in Table 2. The 50-μl reaction mixture consisted of 10 mM Tris (pH 8.3), 50 mM KCl, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 0.01% gelatin, 1.5 mM dNTPs; 25 μM of primers 16S+1 and 16S-1, 75 μM 16SDvR and 50 μM 16SAmF, 1.5U of Taq DNA polymerase, and 2 μL (≈30 ng) of DNA template. Differential priming efficiencies were noted among the different primer sets and combinations. Final primer concentrations were optimized by empirical experimentation to arrive at primer combinations that produced approximately equivalent band intensities. PCR amplification was performed by denaturing the samples at 94°C for 5 min, then 35 cycles of 94°C for 1 min, 54°C for 30 sec, and 72°C for 1 min with a final extension step at 72°C for 10 min. All amplifications were performed on a MJR PTC-200 96-well thermocycler (MJ Research, Watertown, MA). Amplicons were visualized on 2% agarose gels stained with ethidium bromide.

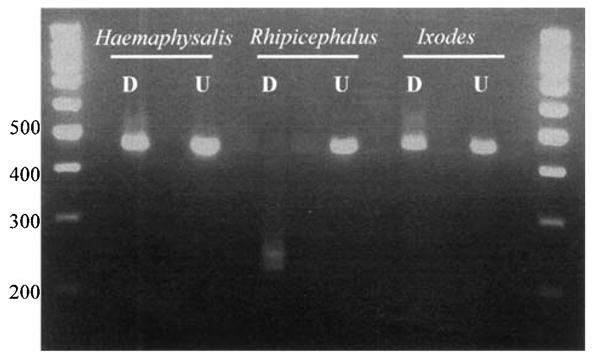

Amplified products that contained only one band of approximately 460 bp (presumably Haemaphysalis or Rhipicephalus) were subjected to RFLP analysis using TauI restriction enzyme (Fermentas Life Sciences, Hanover, MD) following the manufacturer's instructions. Products of the digestion reaction were visualized on 2% agarose gels stained with ethidium bromide.

Validation of multiplex primer design

Following optimization, the multiplexed primer cocktail was evaluated using 160 nymphs collected from several locations in Maryland. Using a dissecting microscope, all specimens were tentatively identified as Amblyomma americanum when compared to the morphology-based Sonenshine key for ticks in Virginia (Sonenshine 1979). The ticks were then crushed whole and processed for genomic amplification, as described above. As an additional validation, ten colony reared ticks representing various stages of D. variabilis, A. americanum, D. andersoni, and I. scapularis were extracted and tested in a manor such that each template was blinded. The investigator tested each template and identified the genus based on the PCR amplification profile. The template identity was revealed and the diagnostic accuracy was determined.

Results

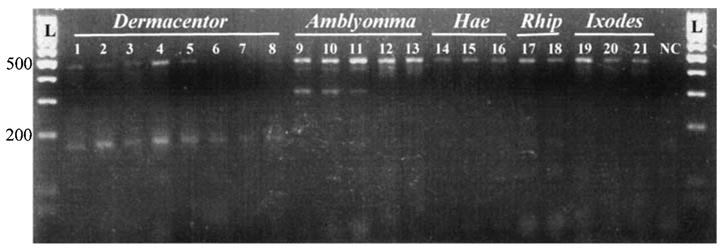

During optimization, all primer combinations produced amplicons of the expected length. Using the four primer multiplexed cocktail, each PCR reaction mixture produced one or two products, the genus-specific amplicon and/or the full length (460 bp) 16S+1/-1 amplicon. Amplicons unique for each tick genus were identified from single PCR reactions; ∼306-bp and 460-bp products for A. americanum, ∼190-bp and 460-bp products for all Dermacentor species, or only the fulllength product (460-bp) for Rhipicephalus, Haemaphysalis, and Ixodes. We were unable to derive an amplicon from A. maculatum using the internal genus specific primer. PCR products were successfully produced from each DNA template as expected, regardless of life stage utilized for source DNA (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

PCR amplification products from the multiplex reaction. Lanes 1–8 are amplified products from Dermacentor species (lanes 1–3: D. variabilis adult, nymph and larvae; lanes 4–6: D. albipictus adult, nymph and larvae; lane 7: D. andersoni adult; lane 8: D. occidentalis adult). Lanes 9–13 represent amplification from Amblyomma species (lanes 9–11: A. americanum adult, nymph and larvae; lanes 12–13: A. maculatum adult and nymph). Lanes 14–16 are Haemaphysalis leporispalustris adult, nymph and larvae. Lanes 17–18 are Rhipicephalus sanguineus adult and nymph specimens. Lanes 19–21 are Ixodes scapularis adult, nymph, and larvae. The ladder is a 100-bp marker. L, ladder; NC, negative control.

Rhipicephalus, Haemaphysalis, and Ixodes (for comparison) amplification products (one band at ∼460 bp) were subjected to RFLP analysis using the restriction enzyme TauI. TauI cuts at the recognition sequence GC[C/G]GC which is present in the mitochondrial 16S rDNA gene fragment of Rhipicephalus species but not in Haemaphysalis or any of the other species of ticks investigated (Fig. 3). Complete digestion produced a doublet band of ∼230 bp (Fig. 4).

Fig. 3.

Ribosomal 16S fragment alignment of the restriction enzyme digestion region (nucleotide 272–276) for TauI restriction enzyme of several species of hard ticks. Species names in bold were tested during this analysis.

Fig. 4.

Restriction digestion of genera that were not differentiated with multiplex PCR primer set. Samples were digested with TauI restriction enzyme. D, digested; U, undigested.

Following optimization, the multiplexed primer cocktail was evaluated on 160 nymphs collected from several locations in Maryland. All specimens had been tentatively identified as Amblyomma americanum using the morphology-based Sonenshine key for ticks in Virginia (Sonenshine 1979). The PCR-based assay confirmed the Amblyomma identification for all specimens. Correct identification of voucher specimens used in the blinded analysis further validated the specificity of the multiplexed PCR-RFLP analysis.

Discussion

Molecular evaluation of ticks for disease transmission and phylogenetic studies has increased tremendously over the past ten years (Sparagano et al. 1999). A considerable amount of this research is being carried out by personnel with little or no training in acarine taxonomy and morphology. Mis-identification can easily lead to erroneous results and, in the case of pathogen transmission, could implicate the incorrect vector species. Additionally, once the specimen is destroyed during DNA extraction, anomalous results are difficult to verify. Although voucher specimens should always be retained and identification verified by qualified taxonomists, the need to validate the identification of extracted tick DNA is crucial. Using established molecular markers for PCR amplification and sequencing can be extremely cost prohibitive, especially for population studies or surveys where possibly hundreds of samples are processed.

In the mid-Atlantic and northeastern regions of the United States, the main tick genera commonly encountered—Ixodes, Dermacentor, Amblyomma, Haemaphysalis, and Rhipicephalus—have overlapping seasonal activity and distributions, and most importantly have the potential to pose as threats to public health. Subsequently, tick collections often consist of more than one tick species at any given time. Misidentification of tick samples could lead to inaccurate disease transmission rates, incorrect host association as well as mis-interpretation of geographic and habitat range.

Three of the tick species used in this study—D. variabilis, A. americanum, and I. scapularis—are predominant ticks commonly encountered in Maryland and are all medically important. Several other tick species were included in this study even though they are either not considered medically important or are not commonly found in Maryland. We felt it was critical to include these species to create a tool that would be useful to investigators in other regions of North America. Although the list of species used in this investigation is not exhaustive, we could speculate on the ability of the species-specific internal primers to anneal to template DNAs from species that were not tested, based on the alignments provided in Table 1.

Internal Dermacentor- and Amblyomma-specific primers were designed to amplify all species of these respective genera. One exception was A. maculatum. The expected Amblyomma-specific fragment could not be amplified from representatives of this species. The 16S gene alignment based on the Amlyomma sequences from genebank illustrates that the internal primer region is highly polymorphic with multiple base changes in A. maculatum compared to A. amblyomma. Attempts at creating a primer with degenerate bases at the predicted mutation sites was not successful (data not shown). The distribution of A. maculatum is limited to the coastal regions of the southeastern United States. Specimens have been found at remote inland locations but populations do not generally become established. In addition, this tick is not common throughout much of the eastern United States.

Due to limited variability in the small 16S rRNA target sequence on which this diagnostic is based, a conserved primer set could not be created to differentiate between Rhipicephalus, Haemaphysalis, and Ixodes. This was partially overcome by using a restriction enzyme, TauI, which specifically cleaves Rhipicephalus, leaving both Haemaphysalis and Ixodes template DNAs uncut (Fig. 4). Further differetiation of Ixodes ticks should not be problematic as the Prostriata can be easily differentiated from the Metastriata using traditional morphological characteristics on all life stages, both engorged and un-engorged. Therefore, the derived PCR-RFLP-based diagnostic is only intended for differentiation of the four Metastriate genera; Dermacentor, Amblyomma, Rhipicephalus, and Haemaphysalis (Fig. 2). The molecular diagnostic described here will allow investigators to confidently discriminate between these Metastriate genera, quickly, easily and inexpensively, either as a confirmation of morphological identifications or verification for material processed in the laboratory for vector genetics or pathogen surveillance.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported in part by a Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Cooperative Agreement Award to D.E.N. (U50/ CCU319554) and NIEHS training award (T32ES07141) to J.M.A. We thank T.R. Schwartz and K.I. Swanson for assistance with collections and J. Keirans for verifying specimen identifications.

References

- Bishop FC, Hixson H. Biology and economic importance of the gulf coast tick. J Econ Entomol. 1936;29:1068–1076. [Google Scholar]

- Black WC, IV, Klompen JSH, Keirans JE. Phylogenetic relationships among tick subfamilies (Ixodidae: Argasidae) based on the 18S nuclear rDNA gene. Mol Phylogenet Evol. 1997;7:129–144. doi: 10.1006/mpev.1996.0382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Black WC, IV, Piesman J. Phylogeny of hard- and softtick taxa (Acari: Ixodida) based on mitochondrial 16S rDNA sequences. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:10034–10038. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.21.10034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caporale DA, Rich SM, Spielman A, et al. Discriminating between Ixodes ticks by means of mitochondrial DNA sequences. Mol Phylogenet Evol. 1995;4:361–365. doi: 10.1006/mpev.1995.1033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crampton A, McKay I, Barker S. Phylogeny of ticks (Ixodida) inferred from nuclear ribosomal DNA. Int J Parasitol. 1996;26:511–517. doi: 10.1016/0020-7519(96)89379-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dobson S, Barker S. Phylogeny of the hard ticks (Ixodidae) inferred from 18S rRNA indicates that the genus Aponomma is paraphyletic. Mol Phylogenet Evol. 1999;11:288–295. doi: 10.1006/mpev.1998.0565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dumler SJ, Bakken J. Human ehrlichioses: newly recognized infections transmitted by ticks. Annu Rev Med. 1998;49:201–213. doi: 10.1146/annurev.med.49.1.201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ewing S, Panciera R, Mathew J, Cummings C, et al. American canine hepatozoonosis. An emerging disease in the New World. Annu Rev NY Acad Sci. 2000;916:81–92. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2000.tb05277.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goethert H, Telford SR., III Enzootic transmission of Anaplasma bovis in Nantucket cottontail rabbits. J Clin Microbiol. 2003;41:3744–3747. doi: 10.1128/JCM.41.8.3744-3747.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrison BA, Engber BR, Apperson CS. Ticks (Acari: Ixodidae) uncommonly found biting humans in North Carolina. J Vector Ecol. 1997;22:6–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hiss RH, Norris DE, Dietrich CR, Whitcomb RF, et al. Molecular taxonomy using single strand confirmation polymorphism (SSCP) analysis of mitochondrial ribosomal DNA genes. Insect Molecular Biology. 1994;3:171–182. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2583.1994.tb00164.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoogstraal H, Wassef HY. Dermacentor (Indocentor) steini (Acari: Ixodoidae: Ixodidae): identity of male and female. J Med Ent. 1986;23:532–537. doi: 10.1093/jmedent/23.5.532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson BJ, Happ CM, Mayer LW, Piesman J, et al. Detection of Borrelia burgdorferi in ticks by species-specific amplification of the flagellin gene. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1992;47:730–741. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1992.47.730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klompen JSH, Black WC, IV, Keirans JE, Oliver JE. Evolution of ticks. Annu Rev Ent. 1996;41:141–161. doi: 10.1146/annurev.en.41.010196.001041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klompen JSH, Dobson SJ, Barker SC. A new subfamily, Bothriocrotoninae n. subfam., for the genusBothriocroton Keirans, King & Sharrad, 1994 status amend (Ixodida: Ixodida), and the synonymy of Aponomma Neumann, 1899 with Amblyomma Koch, 1844. Syst Parasitol. 2002;53:101–107. doi: 10.1023/a:1020466007722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norris DE, Klompen JSH, Black WC., IV Comparison of the mitochondrial 12S and 16S ribosomal genes in resolving phylogenetic relationships amond hard-ticks (Acari: Ixodidae) Ann Entomol Soc Am. 1999;92:117–129. [Google Scholar]

- Norris DE, Klompen JSH, Keirans JE, Black WC., IV Population genetics of Ixodes scapularis (Acari: Ixodidae) based on mitochondrial 16S and 12S genes. J Med Ent. 1996;33:78–89. doi: 10.1093/jmedent/33.1.78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norris DE, Klompen JSH, Keirans JE, Lane RS, et al. Taxonomic status of Ixodes neotomae and I. spinipalpis (Acari: Ixodidae) based on mitochondrial DNA evidence. J Med Ent. 1997;34:696–703. doi: 10.1093/jmedent/34.6.696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parola P, Raoult D. Tick-borne bacterial diseases emerging in Europe. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2001;7:80–83. doi: 10.1046/j.1469-0691.2001.00200.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiu WG, Dykhuizen DE, Acosta MS, Luft MJ. Geographic uniformity of the Lyme disease spirochete (Borrelia burgdorferi) and its shared history with tick vectors (Ixodes scapularis) in the Northeastern United States. Genetics. 2002;160:833–849. doi: 10.1093/genetics/160.3.833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rich SM, Caporale DA, Telford SR, III, et al. Distribution of the Ixodes ricinus-like ticks of eastern North America. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:6284–6288. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.14.6284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rozen S, Skaletsky HJ. Primer3 on the WWW for general users and for biologist programmers. In: Krawetz S, Misener S, editors. Bioinformatics Methods and Protocols: Methods in Molecular Biology. Totowa, NJ: Humana Press; 2000. pp. 365–386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon C, Frati F, Beckenbach A, et al. Evolution, weighting, and phylogenetic utility of mitochondrial gene sequences and a compilation of conserved polymerase chain reaction primers. Ann Entomol Soc Am. 1994;87:651–701. [Google Scholar]

- Sonenshine D. Ticks of Virginia (Acari: Metastigmata) Blacksburg, VA: Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Sonenshine D. Biology of Ticks. I. New York: Oxford University Press; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Sparagano OAE, Allsopp MTEP, Mank RA, et al. Molecular detection of pathogen DNA in ticks (Acari: Ixodidae): a review. Exp Appl Acarol. 1999;23:929–960. doi: 10.1023/a:1006313803979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stiller D, Leatch G, Kuttler K. Proceedings of the Seventh National Anaplasmosis Conference. Mississippi State University; Experimental transmission of bovine anaplasmosis by the winter tick, Dermacentor albipictus (Packard) pp. 463–475. [Google Scholar]

- Uilenberg G. Experimental transmission of Cowdria ruminantium by the Gulf Coast tick Amblyomma maculatum: danger of introducing heartwater and benign African theileriasia into the American mainland. Am J Vet Res. 1982;43:1279–1282. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker D. Tick-transmitted infectious diseases in the United States. Annu Rev Public Health. 1998;19:237–269. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.19.1.237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wesson DM, McLain DK, Oliver JH, et al. Investigation of the validity of species status of Ixodes dammini (Acari: Ixodidae) using rDNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:10221–10225. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.21.10221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]