Abstract

Astrophysicists use the term “dark matter” to describe the majority of the matter and/or energy in the universe that is hidden from view, and biologists now apply it to the new families of RNA they are uncovering. We review evidence for an analogous hidden world containing peptides. The critical experiments involved pulse-labeling human cells with tagged amino acids for periods as short as five seconds. Results are extraordinary in two respects: both nucleus and cytoplasm become labeled, and most signals disappear with a half-life of less than one minute. Just as the synthesis of each mature mRNA is regulated by the abortive production of hundreds of shorter transcripts that are quickly degraded, it seems that the synthesis of each full-length protein in the stable proteome is regulated by an apparently wasteful production and degradation of shorter peptides. Some of the nuclear synthesis is probably a byproduct of nuclear ribosomes proofreading newly-made RNA for inappropriately-placed termination codons (a process that triggers “nonsense-mediated decay”). We speculate that some “dark-matter” peptides will play other important roles in the cell.

Keywords: open-reading frame, protein turnover, RNA turnover, translation, uORF

Many astrophysicists accept the idea that most matter and/or energy in our universe is hidden from view and use the term “dark” to describe it. Biologists now apply the same term to the various RNAs being uncovered by high-throughput sequencing (RNA-seq).1 Here, we outline some reasons that make detection of dark-matter RNA so difficult, and go on to review evidence pointing to the existence of an analogous hidden world containing peptides.

Inefficient Transcription and Rapid Turnover of Aborted Transcripts

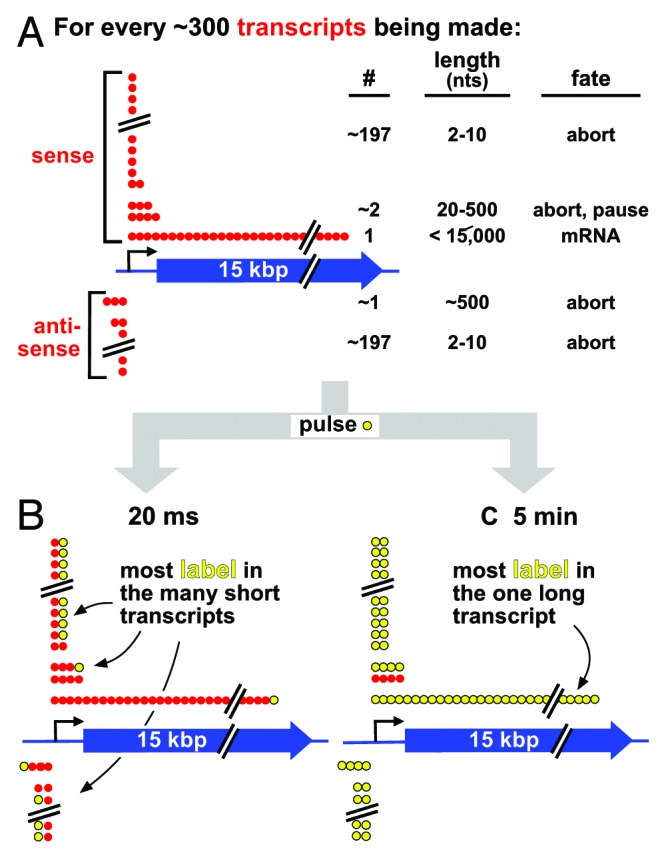

In the 1950s, pulse-chase experiments using radioactive precursors showed that ~95% of the RNA made in mammalian nuclei is degraded within minutes.2 At the time, no credible reason could be proposed for this astonishing turnover, and only later did we discover it results from the destruction of non-coding RNAs and intronic regions within coding transcripts. While such synthesis and destruction appears utterly wasteful, it is nevertheless an integral part of metabolism. At the molecular level, each step seems profligate (Fig. 1A).3 For example, for every 100 transcripts initiated by a bacterial polymerase in vitro and in vivo, ~99 abort within ~10 nucleotides.4 These aborting transcripts are not contained in current catalogs of transcripts made using RNA-seq, as they are too short to be mapped. Eukaryotic polymerases then undergo a structural transition on “escape” from the promoter, but many stall and/or abort prematurely after 20–500 nucleotides to give the promoter-proximal peak seen by RNA-seq.5 Polymerases also initiate on the antisense strand to give similar sets of abortive products. Consequently, the production of each full-length sense transcript is accompanied by the synthesis of >100 shorter products. In a human cell, the associated energy costs must be marginal, as typically nine-tenths of a message will now be spliced out and degraded. Unfortunately, there is little data on the half-lives of prematurely-terminated products, but it is likely they will be less than those of an intron (typically ~5 min) simply because they are so much shorter. Note that even the machines that we expect to perform precisely also initiate inefficiently; most unique sequences in dividing human cells are present in equimolar amounts, but ~200-bp segments from origins of replication are in excess – and are presumably generated as DNA polymerases abort.6

Figure 1. The inefficiency of transcription, and a thought experiment. (A) Strings of red spheres depict nucleotides (nts) incorporated into ~300 transcripts being copied from sense/anti-sense strands of a 15-kbp gene in a cell population. Most polymerases abort prematurely to yield short unstable transcripts of 2–10 nucleotides from both strands, a few pause/abort after generating unstable transcripts of 20–500 nucleotides, and only one generates a stable full-length transcript. The numbers of transcripts in each class are not known, and are included for illustrative purposes only; however, there are probably so many short aborting ones of 2–10 nucleotides that the same general conclusion can be drawn irrespective of precise numbers. (B) After 20 ms (when an elongating polymerase incorporates ~1 labeled nucleotide; yellow), most incorporated label is in short transcripts that soon abort and are quickly degraded; the long transcript contains one label, which goes undetected using most current methods. (C) After 5 min (when a polymerase incorporates ~15 000 nucleotides), the one stable transcript is completely filled with label; however, label incorporated early during the pulse into the many short aborting transcripts has turned over (and so goes undetected).

Now consider a “thought” experiment. Imagine that we could see every nucleotide in every transcript copied from a typical human gene as it is incorporated during a 20-ms “pulse” (when a polymerase adds ~1 nucleotide), and know what its fate might be (Fig. 1B). As the process is so inefficient, most labels at the end of the pulse will be in the many short transcripts that soon abort (and are degraded rapidly, probably within seconds). Only a tiny fraction will be in molecules that contribute to the stable transcriptome. Now imagine we repeat the experiment using a 5 min pulse (long enough for a polymerase to transcribe the gene; Fig. 1C). After 5 min, all transcripts labeled early on will have been degraded, and the few contributing to the stable transcriptome will contain a much higher fraction of label (because they are both stable and longer). As traditional methods usually require pulses of >5 min to allow detection of the full-length RNA (usually the one of interest), they completely miss the rapidly turning-over fraction.

Translation is Seen as Efficient and Proteins as Stable

In contrast to transcription, current reviews see a ribosome initiating efficiently, and then most being able to translate all the way to a termination codon without mishap—although some will stall to be rescued by pathways like those involved in “non-stop” and “no-go” decay.7 Most products made by ribosomes are also seen as stable, with the half-life of a typical human protein being ~20 h (this average covers a wide range varying from minutes to tens of hours).8-10 If production is efficient, and most products are stable, then the efficiency of translation must be very different from that of transcription!

The Proteome is Still Imprecisely Defined

Genome sequences are annotated using complex assumptions, and it remains difficult to predict which segments encode open-reading frames (ORFs) that are translated into protein, especially when those segments are short. For example, it was initially assumed that ORFs should be longer than 300 nucleotides, but ~10% of mouse ORFs are shorter than this,11 and both ribosome profiling (a method for monitoring ribosome binding along a message12) and proteomics show that many such short ORFs (sORFs) are translated, whether they lie in genic or “non-coding” RNAs.12-14 About 50% of human mRNAs also encode upstream open-reading frames (uORFs) of ≥9 nucleotides (median length 48 nucleotides15); many of these uORFs are as evolutionarily conserved as ORFs,11 and are translated into products12,13 that are present in 10–2,000 copies in the cell.14

Translation of sORFs can have important consequences. For example, translation of uORFs reduces expression of associated ORFs,15 and mutations introducing a uORF into the 5′ leader of the mRNA encoding CDKN2A predisposes individuals to melanoma, in LDLR to familial hypercholesterolemia, and in CFTR to cystic fibrosis.16 Some products of sORFs are also medically important, like GnRH1 in hormonal signaling, CCL/CXCL members in innate immunity, and defensins in pathogen protection. Only now are the dedicated pipelines needed for their detection being developed, with 74 new human peptides at the tip of the iceberg being found in a recent survey.14

A Digression on Nuclear Protein Synthesis

Experiments using short pulses have uncovered an incredibly-high turnover of newly-made peptides. These short pulses were being used in an attempt to solve an old chestnut—whether or not translation occurs in nuclei—and we now digress to discuss this.

Studies in the 1950s showed that isolated nuclei could incorporate radiolabeled amino acids into acid-insoluble protease-sensitive material, and this provoked a debate about whether this (apparently nuclear) synthesis was due to contamination by cytoplasmic ribosomes.17 Subsequently, it was shown that protein synthesis in bacteria is often spatially coupled to transcription,18 and it was expected it would be the same in eukaryotes. But the discovery of introns seemed to provide a good reason why such coupling should not occur: if nuclear ribosomes translated introns—which possess many termination codons—too many truncated peptides would be produced, and some would surely be toxic. Clearly, restricting intron-containing RNA to nuclei, and translation of intron-free mRNA to the cytoplasm, prevents such a lethal possibility. This killed the idea that any translation might occur in nuclei.

From time to time, the debate concerning nuclear translation has been re-opened. For example, translation is involved in proofreading mRNA during nonsense-mediated decay (NMD).7 NMD involves the detection of inappropriately-placed termination codons in transcripts and degradation of the faulty RNA. As some NMD may occur in human nuclei,19 and as a translating ribosome is the only known mechanism able to detect stop codons, this points to some nuclear ribosomal activity. (However, contrary findings indicate that NMD is predominantly cytoplasmic in yeast20 and mammals.21) More direct experiments also point to some nuclear translation. Thus, when HeLa cells are permeabilized and allowed to extend nascent peptides by ~15 residues in the presence of a translational precursor like biotin-Lys-tRNA (and triphosphates required for transcription), ~10% of the label in newly-made protein is nuclear; this signal is reduced by incubation with transcriptional inhibitors, which suggests that some translation is biochemically coupled to transcription.22 More recently, cells were pulsed for 5 min with puromycin (a structural mimic of aminoacyl-tRNA), permeabilized, and fixed; puromycin is incorporated by ribosomes into C-termini of nascent peptides, and it was then immuno-localized using an anti-puromycin antibody. Some signal is again nuclear.23 However, in both cases cells were permeabilized, and so critics can say cytoplasmic ribosomes were now able to enter nuclei to give rise to artifactual signals. And although initiation factors, ribosomal proteins, and 80S ribosomes are all found in the nucleoplasm close to transcription sites,22,24-27 this might be expected: ribosomes are made in nucleoli and have to be exported through the nucleoplasm to get to the cytoplasm.

We can then summarize this digression as follows: since introns were discovered, the overwhelming consensus has been that all translation occurs in the cytoplasm. This consensus has withstood repeated questioning.

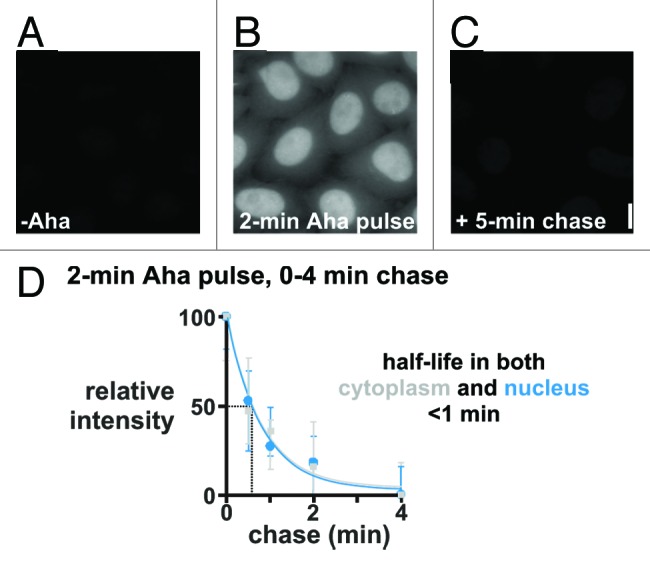

Astonishing Turnover of Newly-Made Peptides in Both Nucleus and Cytoplasm

Baboo et al.28 revisited the question whether there was any nuclear translation using intact cells, and pulses too short to allow peptides made by cytoplasmic ribosomes to enter nuclei during the pulse. Azido-homoalanine (Aha) is a Met analog that possesses a reactive azide group, and Aha-containing peptides can be localized after “clicking” alkyne-linked fluors onto the azide. HeLa cells (or primary diploid human cells) were fed Aha for periods as short as 5 s (during which a ribosome in a living cell polymerizes ~25 residues, or ~one-sixteenth the length of a typical protein). Results obtained using a 2 min Aha pulse are illustrated in Figure 2, and they are astonishing in two respects. First, there is clear nuclear signal which appears brighter than the cytoplasmic one, although integration over the larger cytoplasmic area shows nuclei contain slightly less than half of all signals. Signals are reduced by pretreatment with translational inhibitors (so ribosomes are involved), and increased by pretreatment with a proteasomal inhibitor (so label is in protein). Second, signals in both compartments disappear during chases with half-lives of less than a minute, so that almost none remains after 5 min.

Figure 2. Peptides made in both nucleus and cytoplasm turn over rapidly. HeLa cells were starved of Met for 15 min to deplete pools, pulsed for 2 min ± 2 mM Aha, and chased (0–5 min; 0.2 mM Met without Aha). After fixation and “clicking” on Alexa 555, DNA was counterstained with DAPI, images collected using a wide-field microscope, and fluorescence intensities of Alexa 555 (± SD) seen during the chase in the cytoplasm and nucleus normalized relative to values at 0 min. Bar: 10 μm. (A) If Aha is omitted, no fluorescence is seen. (B) After a 2 min Aha pulse, nuclei appear the brightest; however, integration over the larger area of the cytoplasm indicates that this compartment contains slightly more signal. (C) If the 2 min pulse is followed by a 5 min chase, essentially no signal is seen. (D) Alexa 555 fluorescence in both nucleus and cytoplasm declines rapidly during a chase. From Baboo et al.28

Essentially similar results are obtained using two structurally-unrelated precursors—puromycin (immunolocalized as above) and heavy amino acids. In the latter case, amino acids were tagged with 15N (or 13C), and distributions of incorporated 15N (or 13C) were mapped using a mass spectrometer attached to a microscope—an approach called NanoSIMS (high-resolution secondary-ion mass spectrometry). In a variant experiment, HeLa cells were incubated for 2 min in both [13C]amino acids and [15N]amino acids; then, (13C15N)- ions derived from both nucleus and cytoplasm could be detected. Signals were again sensitive to ribosomal inhibitors, and decayed with half-lives of <1 min. This is consistent with the coupling by a ribosome of two different amino acids into one peptide bond, followed by the rapid destruction of that bond.

These results prompt many questions. For example, why has this astonishing turnover not been seen before? The answer is simple: we should only expect to detect it using a pulse that is roughly the length of the half-life, and such short pulses have not been used previously. How can these results be reconciled with the known ~20 h half-life of the “mature” proteome?10 Once we remember that this half-life was measured using pulses lasting days, the answer is again simple. Just as only a tiny fraction of label incorporated during a short pulse is found in the one stable transcript in Figure 1, a 5 s or 2 min pulse should not be expected to label much of the mature proteome if a substantial amount of abortive translation and rapid turnover occurs. But we should expect more labels to be incorporated into that mature proteome using longer pulses, and it is. Thus, if the experiment in Figure 2C is repeated using 10 min and 1 h pulses, progressively more signals survive the 5 min chase.28 Finally, making a peptide is energetically costly, so how can the system support such waste? Again the answer is simple: the cost must be marginal, as it is for transcription.

A Molecular Explanation for the Peptide Turnover

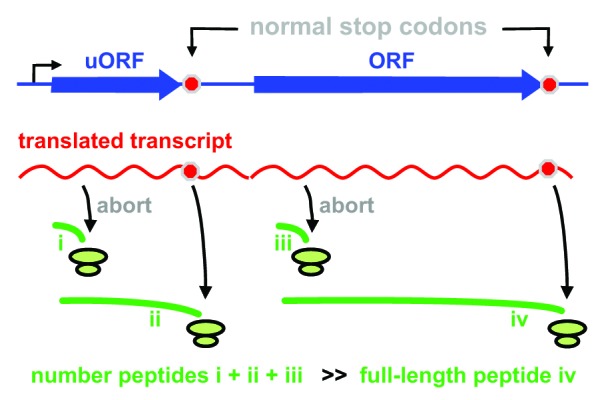

The extraordinary turnover is simply explained if the efficiency of translation is like that of transcription. Just as the polymerization of one full-length transcript is associated with an unproductive turnover of many shorter ones (Fig. 1), we suggest that the polymerization of each full-length peptide is regulated by the synthesis of many shorter peptides that are rapidly degraded. We envisage the scale of the peptide abortion has been underestimated, with perhaps only one in ≥20 initiated ribosomes translating all the way to a termination codon to generate a product that will contribute to the mature proteome. We speculate that most recently-initiated ribosomes abort close to the beginning of uORFs, sORFs, and ORFs because they fail to “escape” (like an RNA polymerase) into a structure that allows stable elongation (Fig. 3); then, the resulting short peptides (combined with those made by translating to ends of many uORFs and sORFs) are degraded rapidly.

Figure 3. A model illustrating how dark-matter peptides (green lines i-iii) and the mature proteome (iv) might arise. Most initiated ribosomes terminate prematurely (giving i and iii), and some translate to the end of the uORF (giving ii); the resulting peptides are rapidly degraded (half-life < 1 min), to give rise to the astonishing turnover seen using short pulses. A minority of ribosomes translates the whole ORF (giving iv); such peptides are the ones detected conventionally using long pulses (they are generally stable and contribute to the mature proteome). From Baboo et al.28

This dark-matter world of aborting peptides has been hidden from our view for reasons much like those that had obscured dark-matter RNA. (1) As illustrated in Figure 1, such a fraction can only be detected using a pulse time roughly the order of the half-life, and then so little label is incorporated that biochemical detection is challenging. (2) Translation was traditionally monitored by incubation in radioactive amino acids, followed by protein precipitation with trichloroacetic acid and scintillation counting; however di- and/or tri-peptides (and probably longer ones too) are not precipitated—and so were missed using this traditional approach.29 (In Fig. 2, perhaps more short peptides are retained during the fixation used for microscopy, compared with the traditional acid extraction.) (3) Short peptides are also missed during gel electrophoresis; those with <100 residues run together in most gels at the “front”, and those with <10 remain unresolved even in dedicated gels.30 In both cases, they are difficult to detect because they bind proportionally less of any stain, and/or pass through membranes without binding during “blotting”. (4) If shorter than ~12 residues, they become indistinguishable from the background produced by proteasomes. (5) By analogy with a polymerase, a recently-initiated ribosome may bind less tightly to its mRNA than one that has translated further—and so might be more likely to detach. This could explain why ribosome profiling uncovers only a small peak of bound ribosomes near initiation codons (as unstable ones detach), and why translation inhibitors increase the area of this peak—by “freezing” unstable ones on the message.12,31 (6) Most peptides with <6 peptides cannot be mapped uniquely within the human proteome by mass spectrometry, and so are missed using current approaches.

The abortive synthesis and turnover probably play additional important roles including: (1) A nuclear ribosome might proofread a pre-mRNA as it is being made to see if it has been spliced appropriately (and so does not contain premature termination codons). Then, the faulty RNA and truncated peptide produced as a by-product would be degraded—one by NMD, the other by the proteasome. Old evidence for this has been reviewed,19,25 and more has been obtained recently.28,32 (It was stated earlier that the discovery of introns killed the idea that translation might occur in nuclei because ribosomes must be prevented from translating intron-containing transcripts; however, a nuclear ribosome would not “see” a termination codon in an intron if that ribosome was so placed it could only act on the transcript once splicing had occurred.25) (2) If such nuclear proofreading of mRNAs is error-prone, perhaps the system has a second go with a cytoplasmic ribosome at detecting a mis-spliced transcript once that transcript reaches the cytoplasm (with consequential degradation of truncated peptides produced as by-products). (3) Some mechanism must also exist to weed out the many non-coding transcripts like the anti-sense promoter transcripts (which are immediately degraded) from the few sense ones that go on to contribute to the stable transcriptome. Again, ribosomes acting co-transcriptionally as part of the NMD machinery could sense the difference between the two (as non-coding transcripts probably contain many stop codons). (4) Many more proteins than hitherto expected may misfold during synthesis, to be degraded immediately. (5) In the special case of antigen-presenting cells, some newly-made peptides may be processed rapidly, and the resulting fragments used in the defense against infection.33,34 In all these cases—whether it be nuclear ribosomes that specialize in proofreading newly-made transcripts, or cytoplasmic ones dedicated to mass-production—the result is the same: inefficient translation, abortive production, and rapid degradation of resulting peptides.

Some Challenges

The discovery of any new world always raises many questions. For example, how many different fractions of short peptides are there in a cell, how quickly does each one turn over, and what are the associated energy costs? Critically, we also need to establish what roles the peptides in each fraction might play, and what additional effects the turnover might have. Fortunately, some necessary techniques are becoming available. Thus, fluorescent tagging of proteins and super-resolution microscopy allow us to monitor interactions in living cells in ever-sharper detail. Moreover, we can use new bioinformatic pipelines to identify sORFs,35 ribosome profiling to see if they are translated,12,13 and “peptidomics” to sequence shorter-than-usual peptides.14 However, we have seen that many challenges remain, especially in detecting and mapping short peptides. And like their counterparts in the RNA world, we can expect most short peptides to be “junk”, with only a minority being of obvious value.

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

No potential conflict of interest was disclosed.

Acknowledgments

S.B. was supported by the Felix Scholarship Trust of The University of Oxford and The Sir William Dunn School of Pathology.

Glossary

Abbreviations:

- Aha

azido-homoalanine

- RNA-seq

high-throughput RNA sequencing

- NanoSIMS

high-resolution secondary-ion mass spectrometry

- NMD

nonsense-mediated decay

- ORF

open reading frame

- sORF

short open reading frame

- uORF

upstream open reading frame

References

- 1.Kapranov P, St Laurent G. Dark matter RNA: existence, function, and controversy. Front Genet. 2012;3:60. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2012.00060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Harris H. An RNA heresy in the fifties. Trends Biochem Sci. 1994;19:303–5. doi: 10.1016/0968-0004(94)90011-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Coulon A, Chow CC, Singer RH, Larson DR. Eukaryotic transcriptional dynamics: from single molecules to cell populations. Nat Rev Genet. 2013;14:572–84. doi: 10.1038/nrg3484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Goldman SR, Ebright RH, Nickels BE. Direct detection of abortive RNA transcripts in vivo. Science. 2009;324:927–8. doi: 10.1126/science.1169237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ehrensberger AH, Kelly GP, Svejstrup JQ. Mechanistic interpretation of promoter-proximal peaks and RNAPII density maps. Cell. 2013;154:713–5. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.07.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gómez M, Antequera F. Overreplication of short DNA regions during S phase in human cells. Genes Dev. 2008;22:375–85. doi: 10.1101/gad.445608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lykke-Andersen J, Bennett EJ. Protecting the proteome: Eukaryotic cotranslational quality control pathways. J Cell Biol. 2014;204:467–76. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201311103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wheatley DN, Giddings MR, Inglis MS. Kinetics of degradation of “short-“ and “long-lived” proteins in cultured mammalian cells. Cell Biol Int Rep. 1980;4:1081–90. doi: 10.1016/0309-1651(80)90045-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bachmair A, Finley D, Varshavsky A. In vivo half-life of a protein is a function of its amino-terminal residue. Science. 1986;234:179–86. doi: 10.1126/science.3018930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Boisvert FM, Ahmad Y, Gierliński M, Charrière F, Lamont D, Scott M, Barton G, Lamond AI. A quantitative spatial proteomics analysis of proteome turnover in human cells. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2012;11:011429. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M111.011429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Frith MC, Forrest AR, Nourbakhsh E, Pang KC, Kai C, Kawai J, Carninci P, Hayashizaki Y, Bailey TL, Grimmond SM. The abundance of short proteins in the mammalian proteome. PLoS Genet. 2006;2:e52. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0020052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ingolia NT, Lareau LF, Weissman JS. Ribosome profiling of mouse embryonic stem cells reveals the complexity and dynamics of mammalian proteomes. Cell. 2011;147:789–802. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fritsch C, Herrmann A, Nothnagel M, Szafranski K, Huse K, Schumann F, Schreiber S, Platzer M, Krawczak M, Hampe J, et al. Genome-wide search for novel human uORFs and N-terminal protein extensions using ribosomal footprinting. Genome Res. 2012;22:2208–18. doi: 10.1101/gr.139568.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Slavoff SA, Mitchell AJ, Schwaid AG, Cabili MN, Ma J, Levin JZ, Karger AD, Budnik BA, Rinn JL, Saghatelian A. Peptidomic discovery of short open reading frame-encoded peptides in human cells. Nat Chem Biol. 2013;9:59–64. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.1120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Calvo SE, Pagliarini DJ, Mootha VK. Upstream open reading frames cause widespread reduction of protein expression and are polymorphic among humans. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:7507–12. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0810916106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Barbosa C, Peixeiro I, Romão L. Gene expression regulation by upstream open reading frames and human disease. PLoS Genet. 2013;9:e1003529. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Goidl JA, Allen WR. Does protein synthesis occurs within the nucleus? Trends Biochem Sci. 1978;3:225–8. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Miller OL, Jr., Hamkalo BA, Thomas CA., Jr. Visualization of bacterial genes in action. Science. 1970;169:392–5. doi: 10.1126/science.169.3943.392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Maquat LE. Nonsense-mediated mRNA decay: splicing, translation and mRNP dynamics. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2004;5:89–99. doi: 10.1038/nrm1310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kuperwasser N, Brogna S, Dower K, Rosbash M. Nonsense-mediated decay does not occur within the yeast nucleus. RNA. 2004;10:1907–15. doi: 10.1261/rna.7132504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Trcek T, Sato H, Singer RH, Maquat LE. Temporal and spatial characterization of nonsense-mediated mRNA decay. Genes Dev. 2013;27:541–51. doi: 10.1101/gad.209635.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Iborra FJ, Jackson DA, Cook PR. Coupled transcription and translation within nuclei of mammalian cells. Science. 2001;293:1139–42. doi: 10.1126/science.1061216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.David A, Dolan BP, Hickman HD, Knowlton JJ, Clavarino G, Pierre P, Bennink JR, Yewdell JW. Nuclear translation visualized by ribosome-bound nascent chain puromycylation. J Cell Biol. 2012;197:45–57. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201112145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brogna S, Sato TA, Rosbash M. Ribosome components are associated with sites of transcription. Mol Cell. 2002;10:93–104. doi: 10.1016/S1097-2765(02)00565-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Iborra FJ, Jackson DA, Cook PR. The case for nuclear translation. J Cell Sci. 2004;117:5713–20. doi: 10.1242/jcs.01538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.De S, Varsally W, Falciani F, Brogna S. Ribosomal proteins’ association with transcription sites peaks at tRNA genes in Schizosaccharomyces pombe. RNA. 2011;17:1713–26. doi: 10.1261/rna.2808411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Al-Jubran K, Wen J, Abdullahi A, Roy Chaudhury S, Li M, Ramanathan P, Matina A, De S, Piechocki K, Rugjee KN, et al. Visualization of the joining of ribosomal subunits reveals the presence of 80S ribosomes in the nucleus. RNA. 2013;19:1669–83. doi: 10.1261/rna.038356.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Baboo S, Bhushan B, Jiang H, Grovenor CRM, Pierre P, Davis BG, Cook PR. Most human proteins made in both nucleus and cytoplasm turn over within minutes. PLoS One. 2014;9:e99346. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0099346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Greenberg NA, Shipe WF. Comparison of the abilities of trichloroacetic, picric, sulfosalicylic, and tungstic acids to precipitate protein hydrolysates and proteins. J Food Sci. 1979;44:735–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2621.1979.tb08487.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schägger H, von Jagow G. Tricine-sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis for the separation of proteins in the range from 1 to 100 kDa. Anal Biochem. 1987;166:368–79. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(87)90587-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lee S, Liu B, Lee S, Huang SX, Shen B, Qian SB. Global mapping of translation initiation sites in mammalian cells at single-nucleotide resolution. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:E2424–32. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1207846109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.de Turris V, Nicholson P, Orozco RZ, Singer RH, Mühlemann O. Cotranscriptional effect of a premature termination codon revealed by live-cell imaging. RNA. 2011;17:2094–107. doi: 10.1261/rna.02918111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yewdell JW, David A. Nuclear translation for immunosurveillance. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:17612–3. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1318259110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Apcher S, Millot G, Daskalogianni C, Scherl A, Manoury B, Fåhraeus R. Translation of pre-spliced RNAs in the nuclear compartment generates peptides for the MHC class I pathway. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:17951–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1309956110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Heo HS, Lee S, Kim JM, Choi YJ, Chung HY, Oh SJ. tsORFdb: theoretical small open reading frames (ORFs) database and massProphet: peptide mass fingerprinting (PMF) tool for unknown small functional ORFs. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2010;397:120–6. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2010.05.093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]