Abstract

Multiple biological processes are regulated by complicated interaction networks formed by protein-protein or protein-RNA interactions. Nuclear bodies (NBs) are a class of membrane-less subnuclear structures, acting as reaction sites, storage and modification sites, or transcription regulating sites involved in signaling transduction. Biochemical and fluorescence-based methods are widely used to study protein-protein interactions, but false-positive results are a major issue, especially for some fluorescence-based methods. Moreover, these methods fail to be applied to study the formation of NBs, which were characterized by a popular bacterial Lac operator and/or repressor (LacO/LacI) system in mammalian cells. Methods investigating assembly of plant NBs are not available. We have recently developed a nucleolar marker protein nucleolin2 (Nuc2)-based method named Nucleolus-tethering System (NoTS) and showed its application in interaction assay among nucleoplasmic proteins and initiation of plant specific NBs, photobodies. In this extraview, we will compare NoTS with the traditional methods and discuss the assembly mechanisms of NBs, in addition to advantages, limitations, and perspectives about the application of NoTS.

Keywords: FRET, BiFC, yeast two-hybrid, F2H, Cajal body, photobody

NoTS Assay for Protein-Protein Interactions

Many cellular events take place step by step by dynamically assembled interaction networks, thus detecting protein-protein interactions is of importance to understand different biological processes in vivo.1,2 Traditional methods, such as yeast two-hybrid, in vitro pull-down, and co-immunoprecipitation (Co-IP), are widely used to study protein-protein interactions.3,4 However, yeast two-hybrid may miss some real interactions because posttranslational modifications of some cellular factors might be absent in yeast.5 The represented results revealed by in vitro pull-down may be not the real ones compared with the in vivo situations.2,6 Co-IP only demonstrates the two interacting proteins are in the same complex in vivo.7 Moreover, these methods fail to display the subcellular localizations of the interacting proteins.

Development of fluorescent proteins and microscopy-based methods such as Fluorescence Resonance Energy Transfer (FRET) and Bimolecular Fluorescence Complementation (BiFC) allow protein complexes to be visualized directly in living cells in their normal environments.2,8-10 The two methods monitor protein-protein interactions in vivo without antibody staining, but there exist some limitations for them. For FRET, spectral cross-talk, along with the auto-fluorescence of samples may produce “noise” signals that increase the acceptor emission falsely. Some cellular conditions unrelated to protein interactions may also produce interference on the fluorescence intensity or lifetime. For example, the high expression of proteins may cause nonspecific energy transfer by increased random collision because of over accumulation of these proteins.2,8 Attaching large chromophore proteins at either N-terminal or C-terminal or internal site may also preclude protein interactions.2 As for BiFC, fluorescent fragments intrinsically associate with each other under some conditions, not related to the real protein-protein interactions, which may limit its applications. Additionally, the high concentration of the fused proteins in a small subcellular volume may increase false positive rate in BiFC experiments.2,9,10 Therefore, a strict negative control such as a mutated protein in its protein-interacting domain is normally necessary; however, this kind of negative control is often difficult to obtain. Conformation of the fusion protein may also affect the distance between two fluorescent fragments, disturbing the result of BiFC.

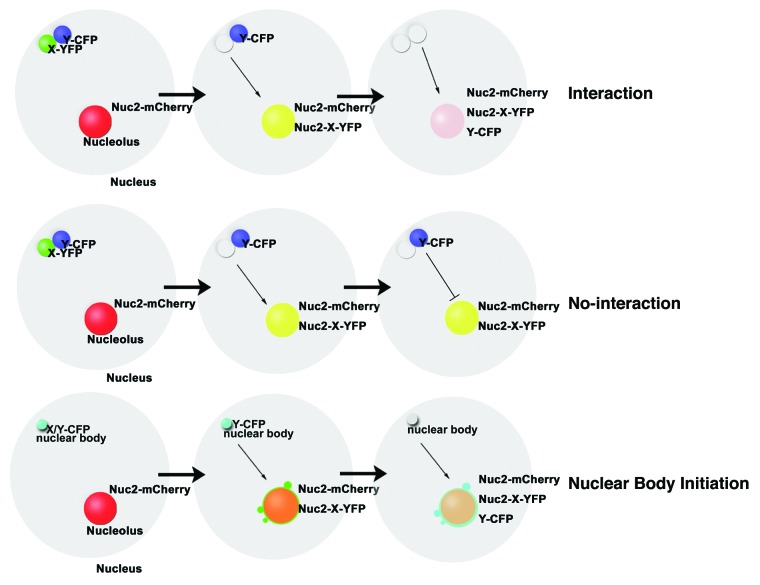

Several methods were developed to visualize protein-protein associations in vivo based on the relocalizations of interacting proteins. The different cytolocalization assay (DCLA) allows observing the cytoplasmic protein-protein interactions in vivo by visualizing relocalizations of preys to the cytoplasmic cell membranes because of the interactions between the bait and preys. The bait is immobilized to the cell membrane by fusing with a specific localization signal, membrane tether localization signal (MTLS).11 An orthoreovirus protein μNS-derived method is used to monitor protein-protein associations inside cells based on co-localization of preys and the bait in the large cytoplasmic aggregates formed by the bait-μNS fusion.12 Additionally, a fluorescent two-hybrid assay (F2H) successfully reveals the protein-protein interactions in living cells in real-time according to the relocations of preys by the fluorescent protein (FP) and the lac repressor (LacI) fused bait, based on the specific binding of LacI to the lac operator (LacO) repeats at a special genomic position.7,13 However, the former two methods are normally suitable for detecting the association between cytoplasmic proteins, and have not been applied in plants. As for the LacO/LacI system, the generation of 256 repeats of LacO sequence in the Agrobacterium-competent binary vector for plant transformation is not easy as the backbone of a binary vector is normally big. Besides, it is difficult to detect if the introduced genes are integrated into plant genome or not in transient assay and it will take a long time to generate transgenic plants containing several genes. The NoTS is applied to visualize protein-protein interactions in the nucleus based on relocation of preys to the nucleolus in plant cells. It can be easily performed in transient assay and costs less time to get the experimental results. In NoTS, we use Nuc2, a nucleolar marker of the nucleolus, as the tethering protein to immobilize a protein of interest (X) to the nucleolus.14-16 We generated a triple fusion protein consistent of the yellow fluorescent protein (YFP), the Nuc2, and a protein of interest (X). This fusion showed a diffuse signal throughout the nucleolus and/or nuclear body-like structures at the periphery of the nucleolus. If another protein (Y) tagged by cyan fluorescent protein (Y-CFP) interacts with X, relocation of Y to the nucleolus can be monitored, which leads to co-localization of YFP and CFP signals (Fig. 1, the top panel). If there is no interaction between X and Y, Y will maintain its original distribution pattern and separated signals of FPs can be detected in vivo (Fig. 1, the middle panel). NoTS reveals protein-protein interactions by visualizing the relocations of interacting proteins to the nucleolus recruited by a protein of interest fused with Nuc2, a nucleolar marker of the nucleolus, which is conserved in eukaryotes.17,18 Through the nucleolar tethering of Nuc2 and recruitment of Nuc2 fusions, the interacting proteins are relocated to the nucleolus and diluted in the large volume of nucleolus, avoiding local high concentrations of these proteins at the interacting sites which easily cause false-positive results, as the cases for BiFC and FRET analysis.

Figure 1. Schematic outline of NoTS assay for nuclear protein-protein interactions and initiation of nuclear bodies. A protein of interest (X) is fused to Nuc2 and YFP to make Nuc2-X-YFP, which is tethered to nucleolus. The interacting protein (Y) of X is fused to CFP. If Y interacts with X, Y-CFP will be relocated to the position of Nuc2-X-YFP and the co-localization signals of YFP and CFP can be detected in the nucleolus, which is labeled by Nuc2-mCherry (the top panel). If Y does not interact with X, Y-CFP will maintain its original position and separated signals of YFP and CFP will be observed in the nucleus (the middle panel). For nuclear body initiation assay, a component of NBs (X) is fused with Nuc2 and YFP to make Nuc2-X-YFP and displays body-like structures at the periphery of nucleolus, which contain other components of the NBs (Y-CFP), suggesting X has initiation ability for the assembly of NBs (the bottom panel).

NoTS is based on exogenously overexpressed Nuc2 fusion protein, however, comparing the expression levels of 18S and 25S rRNAs in wild type (Col-0) and transgenic line overexpressing Nuc2-COP1-YFP in background of cop1 mutant revealed that exogenous expression of Nuc2 is not likely to be problematic for NoTS assay.19 The relocation of a large protein such as the plant microRNA (miRNA) processing enzyme DICER-LIKE 1 (DCL1), with a molecular weight of about 214 kDa, by its interacting protein HYL1 fused by Nuc2 (Nuc2-HYL1) demonstrated the high recruitment efficiency of the interacting proteins by Nuc2 fusion proteins in NoTS.19,20 Successful recruitments of cryptochromes (cry1, cry2), UVR8, CONSTANS (CO) and LONG HYPOCOTYL IN FAR-RED 1 (HFR1) to the nucleolus by Nuc2-COP1 suggested direct interactions between COP1 and them, consistent with previous reports.19,21,22 It is possible that the relocations revealed by NoTS may be resulted from Nuc2 or its-interacting proteins, so controls are of importance to exclude this probability. The failure to detect the co-localization between COP1-interacting proteins and Nuc2 or a WD40 repeat domain-deleted COP1 (Nuc2-COP1△WD40) clearly indicated that the interaction results revealed by NoTS are credible.19

NoTS Assay for the Assembly of Nuclear Bodies

In addition to the application on protein-protein interactions, NoTS can be also used for studying the assembly of NBs. NBs are special subnuclear domains containing many proteins or RNAs to form complicated interaction networks, exerting multiple functions by free exchange of components in NBs with the surrounding nucleoplasm.23-27 Many NBs exist both in animals and plants, including the nucleolus, Cajal bodies (CBs), polycomb group (PcG) body and nuclear speckles.28-31 NBs such as paraspeckles, promyelocytic leukemia body (PML body) and 53BP1 nuclear body were only characterized in mammalian cells.32-34 Some plant-specific NBs are also characterized, such as nuclear dicing bodies (D-bodies), photobodies, cyclophilin-containing bodies, and AKIP1-concentrated bodies.35-37 NBs may be reaction sites, promoting cellular processes by concentrating proteins or RNA required, such as the nucleolus and CBs.17,25,26,30 NBs may also act as hubs recruiting gene loci for transcription regulation like PcG bodies in Drosophila.38 NBs can also serve as storage or modification sites where phosphorylation or sumoylation takes place, such as nuclear speckles and PcG bodies.28,39 In plant NBs, D-bodies might be the sites for maturation of miRNAs.36 Photobodies may be reaction, degradation, or storage sites during light signaling transduction.35

Three assembly models have been put forward to explain the formation of NBs in mammalian cells.25 The first is a stochastic assembly model in which individual component interacts stochastically to build up NBs in an equal and random order.25,40 Different components in CBs like coilin, SMN complex, or special ribonucleoproteins (RNPs) can initiate de novo formation of CBs which share similar morphology, composition and dynamics to the endogenous CBs, suggesting a self-organized model for the assembly of CBs.40 The second is an ordered assembly model, emphasizing the sequential assembly fashion. The third one is a seeding assembly model proposing a seed function during the initiation of NBs. A protein or RNA can be the seed during the assembly process.25 NBs like histone locus bodies (HLBs), nuclear stress bodies (nSBs), paraspeckles, nuclear speckles, and PML body follow a seeding assembly model.30,32,41,42 A hybrid assembly model was proposed recently and suggested that the formation of a nuclear body is first initiated by a seeding event; other components are then recruited to assemble NBs randomly or in a self-organized pathway.43 In mammalian cells, a bacterial LacO/LacI tethering system is widely used to study the assembly of NBs.25,40,44-47 However, this system is not easily used in plant cells, especially for a transient assay.

NoTS revealed the initiation of NBs by testing whether the tethered component of NBs can form a de novo body at the periphery of the nucleolus. If one component of NBs fused with Nuc2 forms body-like structures at the periphery of nucleolus, which are similar to endogenous NBs in components, morphology and dynamics, we can conclude that this component has the nucleation ability to initiate a nuclear body and may be a potential seed in the assembly process (Fig. 1, the bottom panel). The perinucleolar localization can be directly showed in NoTS by co-expressing proteins of interest tagged by three different fluorescent proteins, much easier than the LacO/LacI system for application in plant cells. Using NoTS, many components of photobodies were demonstrated to have capacities of initiating de novo photobodies.19 The similar dynamics between those newly formed bodies and endogenous photobodies, together with the successful complementation of cop1 mutant by transgenic Arabidopsis plants with relocated bodies, suggested that these de novo bodies are truly functional photobodies, which contain components of endogenous photobodies and differ from other plant NBs, indicating that the results about the assembly of photobodies revealed by NoTS are believable.19 Moreover, NoTS makes it convenient to evaluate the nucleation efficiency of different components in the initiation of NBs. The nucleation differences among components in NBs also provided us cues to understand the potential functions of these NBs. NoTS revealed that COP1, an E3 ligase, had the highest initiation efficiency, indicating photobodies may function as degradation sites in light signaling regulation.19

Discussion and Perspectives

Revealing protein-protein interactions by relocations of proteins through its interacting protein is powerful. Proteins relocated to cell membrane, viral factory-like structures (FLS) and the genomic locus containing LacOs have been visualized to detect protein-protein associations or interactions in cytoplasm and nucleus.7,11,12 NoTS uses the nucleolus as an anchor structure to detect the interactions among nucleoplasmic proteins or components of NBs based on immobilization of the bait by fusing with Nuc2 in plants.19 It is quite easy to operate in transient assay in plants and costs less time to display experimental results. As nucleolus is a conserved organelle, it is of great interest to extend the application of NoTS to other cell lines or organisms to detect the nuclear protein-protein interactions.14,17 NoTS does not easily produce a false-positive result, which is a major issue for BiFC and FRET, as when assessing a protein-protein interaction in the nucleolus or at the periphery foci of the nucleolus, full or partial co-localization signal of FPs can be observed throughout the nucleolus in NoTS, avoiding a local high concentration of the proteins by diluting them in the large volume of the nucleolus. However, false-negative result might be a problem for NoTS. The failed recruitment of photoreceptors PHYTOCHROME A (phyA) and PHYTOCHROME B (phyB) to nucleolus by Nuc2-COP1 showed in NoTS indicated indirect or weak interactions may be not suitable for NoTS assay.19,48,49 Thus, the interaction affinity between two proteins is a key factor for application of NoTS, very weak protein-protein interactions may be out of the sensitivity of NoTS. It is a good choice to conjunct NoTS with other fluorescence-based methods like BiFC and FRET. NoTS was now only used to detect the interactions among nucleoplasmic proteins, extending its application to analyze the interactions among cytoplasmic proteins fused with nuclear localization signals will be also of great interest. In this case, it should point out that this may produce unexpected off-target effects in some situations. If the interaction of cytoplasmic proteins depends on modifications by other cytoplasmic proteins, it may miss the interaction result in NoTS. For the assembly of NBs, NoTS is easier to be generated by transient co-expression in plants compared with the bacterial LacO/LacI system. Besides, tethering a protein of interest to the nucleolus by Nuc2 can be easily achieved and monitoring the recruitment and localization of these components to the de novo formed bodies by fluorescent proteins is more direct and simple than antibody staining. Previously, the RNA fused by LacI and MS2 stem loop is tethered to LacO repeats through specific binding of LacO/lacI and MS2 coat/MS2 stem loop and visualized by the fluorescence in site hybridization (FIHS).44,46,47 A λN22 RNA stem-loop binding system is also proposed for visualization of RNA in vivo in plant cells.50 NoTS may be modified to test the function of RNAs in the formation of NBs by using MS2 coat protein/MS2 stem loop or similar systems. This modification may be also helpful for NoTS to test the RNA-protein interactions. In plants, D-bodies are related to maturation of miRNAs; nuclear speckles are involved in splicing of messenger RNAs (mRNAs). It is of interest to explore the assembly of D-bodies or plant nuclear speckles and reveal the potential functions of RNAs in these NBs.36,51 As NoTS revealed the assembly of photobodies follows a self-organization model, further tests are needed to address whether this kind of assembly model is also applied to other NBs in plants.19

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

No potential conflict of interest was disclosed.

Acknowledgments

We thank members of Fang’s lab for insightful discussions. This work was supported by grants to Y. F. from National Natural Science Foundation of China (31171168 and 91319304), National Basic Research Program of China (973 Program, 2012CB910503).

References

- 1.Galperin E, Verkhusha VV, Sorkin A. Three-chromophore FRET microscopy to analyze multiprotein interactions in living cells. Nat Methods. 2004;1:209–17. doi: 10.1038/nmeth720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ciruela F. Fluorescence-based methods in the study of protein-protein interactions in living cells. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 2008;19:338–43. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2008.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Miller J, Stagljar I. Using the yeast two-hybrid system to identify interacting proteins. Methods Mol Biol. 2004;261:247–62. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-762-9:247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Selbach M, Mann M. Protein interaction screening by quantitative immunoprecipitation combined with knockdown (QUICK) Nat Methods. 2006;3:981–3. doi: 10.1038/nmeth972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Parrish JR, Gulyas KD, Finley RL., Jr. Yeast two-hybrid contributions to interactome mapping. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 2006;17:387–93. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2006.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nguyen TN, Goodrich JA. Protein-protein interaction assays: eliminating false positive interactions. Nat Methods. 2006;3:135–9. doi: 10.1038/nmeth0206-135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zolghadr K, Mortusewicz O, Rothbauer U, Kleinhans R, Goehler H, Wanker EE, Cardoso MC, Leonhardt H. A fluorescent two-hybrid assay for direct visualization of protein interactions in living cells. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2008;7:2279–87. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M700548-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Padilla-Parra S, Tramier M. FRET microscopy in the living cell: different approaches, strengths and weaknesses. Bioessays. 2012;34:369–76. doi: 10.1002/bies.201100086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kerppola TK. Visualization of molecular interactions using bimolecular fluorescence complementation analysis: characteristics of protein fragment complementation. Chem Soc Rev. 2009;38:2876–86. doi: 10.1039/b909638h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kerppola TK. Bimolecular fluorescence complementation: visualization of molecular interactions in living cells. Methods Cell Biol. 2008;85:431–70. doi: 10.1016/S0091-679X(08)85019-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Blanchard D, Hutter H, Fleenor J, Fire A. A differential cytolocalization assay for analysis of macromolecular assemblies in the eukaryotic cytoplasm. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2006;5:2175–84. doi: 10.1074/mcp.T600025-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Miller CL, Arnold MM, Broering TJ, Eichwald C, Kim J, Dinoso JB, Nibert ML. Virus-derived platforms for visualizing protein associations inside cells. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2007;6:1027–38. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M700056-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zolghadr K, Rothbauer U, Leonhardt H. The fluorescent two-hybrid (F2H) assay for direct analysis of protein-protein interactions in living cells. Methods Mol Biol. 2012;812:275–82. doi: 10.1007/978-1-61779-455-1_16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tajrishi MM, Tuteja R, Tuteja N. Nucleolin: The most abundant multifunctional phosphoprotein of nucleolus. Commun Integr Biol. 2011;4:267–75. doi: 10.4161/cib.4.3.14884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Minguez A, Moreno Diaz de la Espina S. In situ localization of nucleolin in the plant nucleolar matrix. Exp Cell Res. 1996;222:171–8. doi: 10.1006/excr.1996.0022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dickinson LA, Kohwi-Shigematsu T. Nucleolin is a matrix attachment region DNA-binding protein that specifically recognizes a region with high base-unpairing potential. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15:456–65. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.1.456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shaw P, Brown J. Nucleoli: composition, function, and dynamics. Plant Physiol. 2012;158:44–51. doi: 10.1104/pp.111.188052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ma N, Matsunaga S, Takata H, Ono-Maniwa R, Uchiyama S, Fukui K. Nucleolin functions in nucleolus formation and chromosome congression. J Cell Sci. 2007;120:2091–105. doi: 10.1242/jcs.008771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liu Y, Liu Q, Yan Q, Shi L, Fang Y. Nucleolus-tethering system (NoTS) reveals that assembly of photobodies follows a self-organization model. Mol Biol Cell. 2014;25:1366–73. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E13-09-0527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kurihara Y, Takashi Y, Watanabe Y. The interaction between DCL1 and HYL1 is important for efficient and precise processing of pri-miRNA in plant microRNA biogenesis. RNA. 2006;12:206–12. doi: 10.1261/rna.2146906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lau OS, Deng XW. The photomorphogenic repressors COP1 and DET1: 20 years later. Trends Plant Sci. 2012;17:584–93. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2012.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yi C, Deng XW. COP1 - from plant photomorphogenesis to mammalian tumorigenesis. Trends Cell Biol. 2005;15:618–25. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2005.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sleeman JE, Trinkle-Mulcahy L. Nuclear bodies: new insights into assembly/dynamics and disease relevance. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2014;28C:76–83. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2014.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dundr M. Nuclear bodies: multifunctional companions of the genome. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2012;24:415–22. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2012.03.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mao YS, Zhang B, Spector DL. Biogenesis and function of nuclear bodies. Trends Genet. 2011;27:295–306. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2011.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dundr M, Misteli T. Biogenesis of nuclear bodies. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2010;2:a000711. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a000711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Matera AG, Izaguire-Sierra M, Praveen K, Rajendra TK. Nuclear bodies: random aggregates of sticky proteins or crucibles of macromolecular assembly? Dev Cell. 2009;17:639–47. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2009.10.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Spector DL, Lamond AI. Nuclear speckles. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2011;3:3. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a000646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pederson T. The nucleolus. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2011;3:3. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a000638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nizami Z, Deryusheva S, Gall JG. The Cajal body and histone locus body. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2010;2:a000653. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a000653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bemer M, Grossniklaus U. Dynamic regulation of Polycomb group activity during plant development. Curr Opin Plant Biol. 2012;15:523–9. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2012.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lallemand-Breitenbach V, de Thé H. PML nuclear bodies. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2010;2:a000661. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a000661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Foltánková V, Matula P, Sorokin D, Kozubek S, Bártová E. Hybrid detectors improved time-lapse confocal microscopy of PML and 53BP1 nuclear body colocalization in DNA lesions. Microsc Microanal. 2013;19:360–9. doi: 10.1017/S1431927612014353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fox AH, Lamond AI. Paraspeckles. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2010;2:a000687. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a000687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Van Buskirk EK, Decker PV, Chen M. Photobodies in light signaling. Plant Physiol. 2012;158:52–60. doi: 10.1104/pp.111.186411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Liu Q, Shi L, Fang Y. Dicing bodies. Plant Physiol. 2012;158:61–6. doi: 10.1104/pp.111.186734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shaw PJ, Brown JW. Plant nuclear bodies. Curr Opin Plant Biol. 2004;7:614–20. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2004.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Brown JL, Kassis JA. Architectural and functional diversity of polycomb group response elements in Drosophila. Genetics. 2013;195:407–19. doi: 10.1534/genetics.113.153247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.MacPherson MJ, Beatty LG, Zhou W, Du M, Sadowski PD. The CTCF insulator protein is posttranslationally modified by SUMO. Mol Cell Biol. 2009;29:714–25. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00825-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kaiser TE, Intine RV, Dundr M. De novo formation of a subnuclear body. Science. 2008;322:1713–7. doi: 10.1126/science.1165216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Naganuma T, Hirose T. Paraspeckle formation during the biogenesis of long non-coding RNAs. RNA Biol. 2013;10:456–61. doi: 10.4161/rna.23547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sasaki YT, Ideue T, Sano M, Mituyama T, Hirose T. MENepsilon/beta noncoding RNAs are essential for structural integrity of nuclear paraspeckles. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:2525–30. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0807899106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dundr M. Seed and grow: a two-step model for nuclear body biogenesis. J Cell Biol. 2011;193:605–6. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201104087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dundr M. Nucleation of nuclear bodies. Methods Mol Biol. 2013;1042:351–64. doi: 10.1007/978-1-62703-526-2_23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Shevtsov SP, Dundr M. Nucleation of nuclear bodies by RNA. Nat Cell Biol. 2011;13:167–73. doi: 10.1038/ncb2157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mao YS, Sunwoo H, Zhang B, Spector DL. Direct visualization of the co-transcriptional assembly of a nuclear body by noncoding RNAs. Nat Cell Biol. 2011;13:95–101. doi: 10.1038/ncb2140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Carmo-Fonseca M, Rino J. RNA seeds nuclear bodies. Nat Cell Biol. 2011;13:110–2. doi: 10.1038/ncb0211-110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Jang IC, Henriques R, Seo HS, Nagatani A, Chua NH. Arabidopsis PHYTOCHROME INTERACTING FACTOR proteins promote phytochrome B polyubiquitination by COP1 E3 ligase in the nucleus. Plant Cell. 2010;22:2370–83. doi: 10.1105/tpc.109.072520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yang SW, Jang IC, Henriques R, Chua NH. FAR-RED ELONGATED HYPOCOTYL1 and FHY1-LIKE associate with the Arabidopsis transcription factors LAF1 and HFR1 to transmit phytochrome A signals for inhibition of hypocotyl elongation. Plant Cell. 2009;21:1341–59. doi: 10.1105/tpc.109.067215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Schönberger J, Hammes UZ, Dresselhaus T. In vivo visualization of RNA in plants cells using the λN₂₂ system and a GATEWAY-compatible vector series for candidate RNAs. Plant J. 2012;71:173–81. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2012.04923.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Reddy AS, Day IS, Göhring J, Barta A. Localization and dynamics of nuclear speckles in plants. Plant Physiol. 2012;158:67–77. doi: 10.1104/pp.111.186700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]