Abstract

Gelation process of acid-induced casein gels was studied using response surface method (RSM). Ratio of casein to whey proteins, incubation and heating temperatures were independent variables. Final storage modulus (G′) measured 200 min after the addition of glucono-δ-lactone and the gelation time i.e. the time at which G′ of gels became greater than 1 Pa were the parameters studied. Incubation temperature strongly affected both parameters. The higher the incubation temperature, the lower was the G′ and the shorter the gelation time. Increased heating temperature however, increased the G′ but again shortened the gelation time. Increase in G′ was attributed to the formation of disulphide cross-linkages between denatured whey proteins and casein chains; whilst the latter was legitimized by considering the higher isoelectric pH of whey proteins. Maximum response (G′ = 268.93 Pa) was obtained at 2.7 % w/w, 25 °C and 90 °C for casein content, incubation and heating temperatures, respectively.

Keywords: Acid-induced gel, Gelation behavior, Rheology, Response surface method

Introduction

Acid-induced casein gels are simple model systems used for yogurt and other fermented dairy products (Madadlou et al. 2010). These systems are of importance for providing a scientific framework (Foegeding et al. 2003) for gel structures formed via acidification of milk or caseinate solutions. Acidification is done in these systems either with bacterial cultures or glucono-δ-lactone (GDL), resulting in aggregation of caseins (Braga et al. 2006). As pH drops to the isoelectric point of casein, it becomes unstable and coagulates to form a firm gel, composed of strands of caseins. The caseins with the whey proteins entrapped within this matrix form a protein network. The use of GDL in a model system addresses some of problems associated with starter bacteria, such as variable activity and variation with the type of culture used (Braga et al. 2006).

Gelation behavior of casein solutions and rheological properties of gels are affected by processing variables during their manufacture. Several studies have been carried out to assess the influences of heat treatment prior to gelation (van Vliet and Keetels 1995; Lee and Lucey 2004a) and incubation temperature during gelation (Lucey et al. 1998a; Lee and Lucey 2004a, b; Phadungath 2005) on the rheological properties of casein gels. Heat treatment of milk leads to the denaturation of whey proteins, a number of which may complex with caseins by hydrophobic and intermolecular disulphide interactions (Smits and van Brouwershaven 1980). This could modify the gelation behavior of casein gels. The effect of casein to whey protein ratio on rheological properties of casein gels has also been studied, resulting in ambiguous observations. It has been reported that storage modulus (G′) decreased when casein to whey protein ratio increased (Kücükcetin 2008); on the contrary, an increase in G′ has been reported by Damin et al. (2009). Jelen et al. (1987) and Morris et al. (1995) reported that casein to whey protein ratio had no significant effect on G′.

Little has however been reported on the combined effects of various variables on detailed gelation behavior of acid-induced casein gels and most publications dealt with the influence of individual factors on gelation. The objective of the present research was therefore to study the combined effects of heat treatment before gelation, casein to whey protein ratio and incubation temperature during gelation process on the gelation behavior of casein solutions. Response surface method (RSM) in which a response of interest is influenced simultaneously by several variables (Baş and Boyaci 2007) was used throughout the study. The approach helps to define the influence of the independent variables either alone or in combination (Yim et al. 2012).

Materials and methods

Casein was procured from Merck (Darmstadt, Germany). WPC was procured from DMV International (Textrion PROGEL 800, DMV International, Veghel, The Netherlands) and typically contained 78 % protein, 5 % lactose, 6 % fat, 4 % ash and 5 % moisture according to the manufacturer. GDL was obtained from Merck (Darmstadt, Germany).

Preparation of solutions and gels

Different casein content, incubation and heating temperatures were the gelation process variables tested according to the experimental design outlined in Table 1. Casein and WPC were blended at desired quantities to obtain different ratios (2.1:0.9, 2.4:0.6 and 2.7:0.3) of casein to WPC. These were blended at 3 % total solids (w/w) and hydrated with deionized water; sodium azide (100 mg L−1) was added to prevent microbial growth. After adjusting pH of mixture to ~6.8 using 5 M NaOH and stirring at 6,500 rpm for 60 min (Ultraturax T25 IKA, IKA® Laboratory Equipment, Staufen, Germany), the solution was stored in a refrigerator (~5 °C) overnight to allow complete hydration.

Table 1.

Experimental design and levels for studied factors in actual values

| Test | Casein content (%w/w) | Incubation temperature (°C) | Heating temperature (°C) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2.1 | 25 | 90 |

| 2 | 2.4 | 35 | 80 |

| 3 | 2.4 | 35 | 80 |

| 4 | 2.4 | 35 | 90 |

| 5 | 2.7 | 45 | 90 |

| 6 | 2.1 | 25 | 70 |

| 7 | 2.7 | 25 | 90 |

| 8 | 2.4 | 35 | 80 |

| 9 | 2.4 | 35 | 80 |

| 10 | 2.1 | 45 | 90 |

| 11 | 2.7 | 25 | 70 |

| 12 | 2.7 | 35 | 80 |

| 13 | 2.4 | 35 | 80 |

| 14 | 2.1 | 45 | 70 |

| 15 | 2.1 | 35 | 80 |

| 16 | 2.4 | 35 | 70 |

| 17 | 2.7 | 45 | 70 |

| 18 | 2.4 | 35 | 80 |

| 19 | 2.4 | 45 | 80 |

| 20 | 2.4 | 25 | 80 |

The mixture was then heated at 70, 80 or 90 °C for 15 min using a thermostatically controlled water bath (Gesellschaft fur Labortechnik mbH., Burgwedel, Germany). After cooling the mixture, acidification was performed using GDL at 0.7 % (w/w) at three different temperatures for gelation: 25, 35 or 45 °C.

Rheological properties

Immediately after the GDL addition, solution was well shaken for 1 min and then 37 mL of solution was transferred to the rheometer (Physica MCR301, Anton paar, GmbH, Ostfildern, Germany). Oscillatory rheological measurements were made at a controlled rate. By using the dimensions recommended by Steffe (1996) the vane st14 was introduced into the cup vertically. Temperature was regulated and fixed by a viscotherm VT 2 circulating bath and controlled with a Peltier system (Anton Paar, GmbH, Ostfildern, Germany) with an accuracy of ±0.1 °C. Solvent trap was used to prevent evaporation of the samples. Time-sweep measurements were performed throughout the gelation process at 25, 35 and 45 °C, at a frequency of 1 Hz and with an applied strain of 1 % that was within the linear viscoelastic range of this type of gel network (Lee and Lucey 2006). The test ended 200 min after inoculation with GDL to approximately mimic the conventional incubation time for acid-induced milk gels; measurements were taken every 1 min. G′ was reported as the final G′ value measured 200 min after the addition of GDL. Gelation was arbitrarily described as the moment when G′ of gels became greater than 1 Pa (Lee and Lucey 2004b; Lee and Lucey 2006).

Experimental design and statistical analysis

The effects of heat treatment and incubation temperature and casein to whey protein ratio on gelation behavior of gels were investigated using RSM. These parameters were used as independent variables. The design that consisted of 8 cube points, 6 center points in cubes, 6 axial points and no center points on axes produced 20 runs (Table 1). Cube points were used to assess the linear and interaction effects, center points provided the possibility of checking for curvature in response and axial points were used to estimate quadratic terms. Axial points, which were positioned outside or on the surface of the cube, sat on the cube surface in a face-centered design. Because of poor description of geometric slope of response surfaces in first-order models, two independent variables and one dependent (response variable) were plotted based on a second-order (polynomial) model. Eq. (1) shows a second-order polynomial model that was fitted to the experimental data. In the equation Y is the response, β0, βi, βii and βij are regression coefficients for intercept, linear, quadratic and interaction coefficients, respectively and Xi and Xj are the independent variables (Madadlou et al. 2009; Jha et al. 2012):

|

1 |

Minitab version 15.1.1.0 (Minitab Inc., Pennsylvania, USA) was used for response surface analysis and mapping of plots. After analyzing the collected data, contour plots were drawn by the software and used for further investigations. In a contour plot, the response surface was viewed as a two-dimensional plane where all points that had the same response were connected to produce contour lines of constant responses (Minitab Help, Minitab@ Release 15.1).

Results and discussion

RSM model for G′

The role of rheology is critical when a liquid (sol) is transformed into a semi-solid (gel) during the process of gelation (Tiwari and Bhattacharya 2012). Oscillatory rheology is extensively used to study the viscoelastic behavior of food systems and monitor the formation and strengthening process of gels. The parameters measured in this test are very sensitive to chemical composition and physical structure of gel (Cavallieri and Da Cunha 2008). Rheological parameters e.g. dynamic moduli describing casein gels depend generally on the number and strength of bonds among casein particles, on the structure of particles and the spatial distribution of the strands forming these particles (Lucey et al. 1997a). The following equation (Eq. (2)) yielded after statistical analysis of data is an empirical relationship between the response and the studied variables:

|

2 |

Where Y is G′ (final G′ value measured 200 min after the addition of GDL) and x1, x2 and x3 are casein to whey protein ratio, incubation and heating temperatures, respectively. The model coefficients and analysis of variance (ANOVA) are presented in Tables 2 and 3. P-value for lack-of-fit (0.163) and the ratio of lack-of-fit to pure error (2.56) show that the proposed model is adequate for describing the data (Ginta et al. 2009). R2 value (99.89 %) of model, the fraction of the variation of response explained by the model (Madadlou et al. 2009) also shows a very good correlation between the experimental and predicted values. Significance of each model term was determined according to Pareto principle. The principle states that amongst several factors, which influence a situation or a response, only few ones will account for the most of the impact (Val-Arreola et al. 2006). The standardized effects (each coefficient was divided by its standard error) and P values detailed in Table 2 were used for significance determination of terms. The smaller the magnitude of P value, the more significant is the corresponding term (Bayraktar 2001). Considering the Pareto principle, the quadratic effect of incubation temperature is the most significant term in determination of G′, followed by the effect of incubation temperature. The interactive effect of incubation temperature and heating temperature and the effect of heating temperature were also more significant than the other factors.

Table 2.

Terms of quadratic model and their significance for storage modulus (G′)

| Model term | Coefa | SE Coefb | Coef/SEc | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Constant | 145.710 | 185.029 | 0.787 | 0.449 |

| Casein content | 129.682 | 133.328 | 0.973 | 0.354 |

| Incubation temperature | −39.694 | 2.298 | −17.270 | 0.000*** |

| Heating temperature | 14.196 | 4.000 | 3.549 | 0.005* |

| Casein content × Casein content | −12.980 | 26.443 | −0.491 | 0.634 |

| Incubation temperature × Incubation temperature | 0.614 | 0.024 | 25.814 | 0.000*** |

| Heating temperature × Heating temperature | −0.039 | 0.024 | −1.625 | 0.135 |

| Casein content × Incubation temperature | −0.837 | 0.465 | −1.801 | 0.102 |

| Casein content × Heating temperature | −0.396 | 0.465 | −0.851 | 0.415 |

| Incubation temperature × Heating temperature | −0.149 | 0.014 | −10.688 | 0.000*** |

acoefficient

bstandard error of coefficient

ccoefficient/standard error

***P ≤ 0.001; **P ≤ 0.01; *P ≤ 0.05

Table 3.

Analysis of variance (ANOVA) of the quadratic model for storage modulus (G′)

| Source | DFa | Seq SSb | Adj SSc | Adj MSd | F value | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Regression | 9 | 135417 | 135417.1 | 15046.35 | 966.07 | 0.000*** |

| Linear | 3 | 116455 | 4752.6 | 1584.21 | 101.72 | 0.000 |

| Square | 3 | 17122 | 17121.7 | 5707.24 | 366.44 | 0.000 |

| Interaction | 3 | 1841 | 1840.8 | 613.61 | 39.40 | 0.000 |

| Residual Error | 10 | 156 | 155.7 | 15.57 | ||

| Lack-of-Fit | 5 | 112 | 112.0 | 22.40 | 2.56 | 0.163 |

| Pure Error | 5 | 44 | 43.7 | 8.75 | ||

| Total | 19 | 135573 |

a DF degrees of freedom

b Seq SS sum of squares

c Adj SS the adjusted sum of squares

d Adj MS the adjusted mean square

***P ≤ 0.001

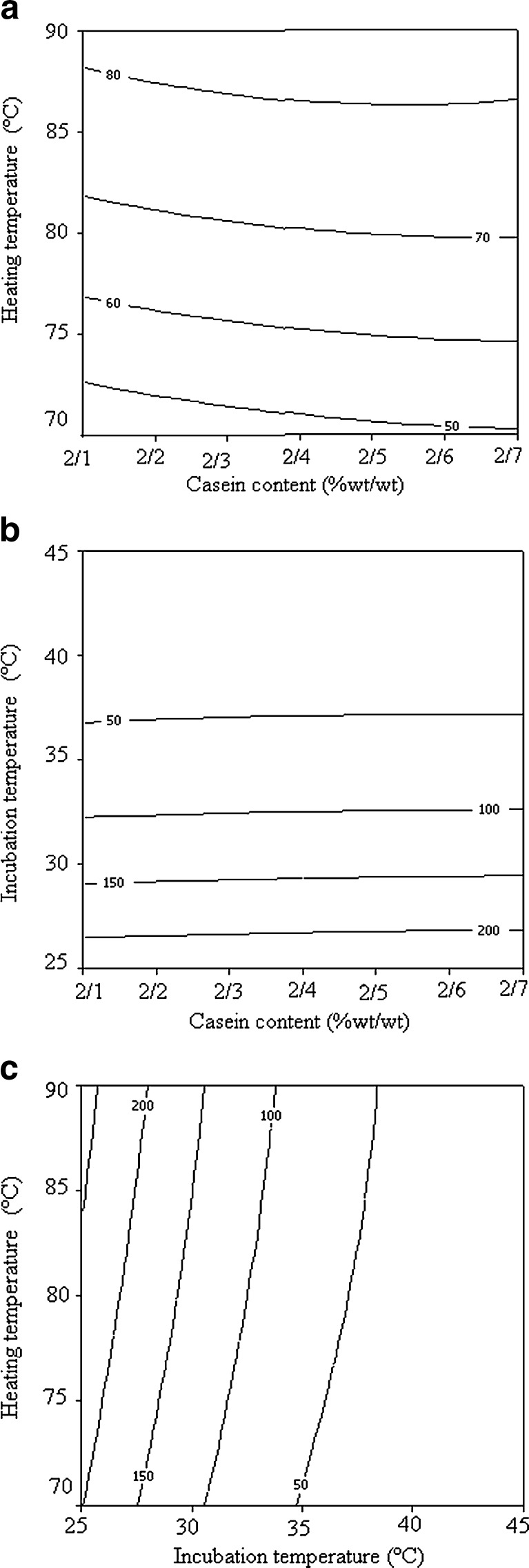

Contour plots can imagine the model equation. Each contour plot represents a combination of two studied variables with the other ones maintained at their middle level (Bayraktar 2001). Figure 1a represents the interaction between casein content and heating temperature. This plot shows that G′ >80 Pa was obtained at casein content of 2.1–2.7 % (w/w) and heating temperature of 86.52–88.18 °C. As shown in Fig. 1b, G′ >200 Pa was obtained at casein content of % 2.1–2.7 (w/w) and incubation temperature of 25–26.84 °C. Figure 1c shows that G′ >250 Pa was obtained at incubation temperature of 25–25.72 °C and heating temperature of 84.32–90 °C. These findings suggest that casein to whey protein ratio had no significant effect on G′ which agrees with the results of Jelen et al. (1987) and Morris et al. (1995).

Fig. 1.

Counter plots showing the influence of different parameters on storage modulus (G′) of gels: (a) influence of casein content and heating temperature on G′ at incubation temperature of 35 °C, (b) influence of casein content and incubation temperature on G′ at heating temperature of 80 °C, (c) influence of heating temperature and incubation temperature on G′ at casein content of 2.4 % wt/wt

Results showed that gels formed at higher gelation (incubation) temperatures had lower G′ values compared with those formed at lower temperatures (Fig. 1b). It is attributed to the more compact conformation and reduced voluminosity of casein particles at higher temperature since hydrophobic interactions in the structure of particles are endothermic (Lucey et al. 1997a; Lee and Lucey 2004a; Roefs and van Vliet 1990). Gels formed from solutions heated at higher temperatures had higher G′ values compared with those formed from samples heated at lower temperatures. Lucey et al. (1997b) observed a large increase in denaturation of β-lactoglobulin when milk was heated at ~80 °C compared with milk heated at 75 °C. During heating at >80 °C, α-lactalbumin and β-lactoglobulin may denature and form aggregates, afterwards associate with the micelle as the temperature is raised to 90–95 °C (Sodini et al. 2005). Increased disulphide cross-links amongst denatured whey proteins and casein plays a dominant role in increasing G′ value of these gels (Lucey et al.1998b).

Gelation time

The following equation (Eq. (3)) is an empirical relationship between gelation time and the studied variables:

|

3 |

The model coefficients and analysis of variance (ANOVA) are presented in Tables 4 and 5, respectively. P-value for lack-of-fit (0.110) and the ratio of lack-of-fit to pure error (3.26) show that the proposed model is adequate for describing the data (Ginta et al. 2009). R2 value (99.87 %) of model also shows a very good correlation between the experimental and predicted values. The first-order effect of incubation temperature was the most significant term in determination of gelation time, followed by the quadratic and first-order effects of casein content, the quadratic effect of incubation temperature and the first-order effect of heating temperature, respectively (Table 4).

Table 4.

Terms of quadratic model and their significance indices for gelation time

| Model term | Coefa | SE Coefb | Coef/SEc | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Constant | 219.480 | 61.1951 | 3.587 | 0.005 |

| Casein content | 119.023 | 44.0960 | 2.699 | 0.022* |

| Incubation temperature | −5.135 | 0.7602 | −6.755 | 0.000*** |

| Heating temperature | −3.112 | 1.3229 | −2.352 | 0.040* |

| Casein content × Casein content | −23.737 | 8.7454 | −2.714 | 0.022* |

| Incubation temperature × Incubation temperature | 0.019 | 0.0079 | 2.368 | 0.039* |

| Heating temperature × Heating temperature | 0.014 | 0.0079 | 1.733 | 0.114 |

| Casein content × Incubation temperature | −0.250 | 0.1538 | −1.625 | 0.135 |

| Casein content × Heating temperature | 0.083 | 0.1538 | 0.542 | 0.600 |

| Incubation temperature × Heating temperature | 0.010 | 0.0046 | 2.167 | 0.055 |

acoefficient

bstandard error of coefficient

ccoefficient/standard error

***P ≤ 0.001; **P ≤ 0.01; *P ≤ 0.05

Table 5.

Analysis of variance (ANOVA) of the quadratic model for gelation time

| Source | DFa | Seq SSb | Adj SSc | Adj MSd | F value | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Regression | 9 | 13365.8 | 13365.764 | 1485.0848 | 871.71 | 0.000*** |

| Linear | 3 | 13329.4 | 102.080 | 34.0266 | 19.97 | 0.000 |

| Square | 3 | 23.4 | 23.364 | 7.7879 | 4.57 | 0.029 |

| Interaction | 3 | 13.0 | 13.000 | 4.3333 | 2.54 | 0.115 |

| Residual Error | 10 | 17.0 | 17.036 | 1.7036 | ||

| Lack-of-Fit | 5 | 13.0 | 13.036 | 2.6073 | 3.26 | 0.110 |

| Pure Error | 5 | 4.0 | 4.000 | 0.8000 | ||

| Total | 19 | 13382.8 |

a DF degrees of freedom

b Seq SS sum of squares

c Adj SS the adjusted sum of squares

d Adj MS the adjusted mean square

***P ≤ 0.001

Since casein content had a direct relation with gelation time (Table 4), a decrease in casein content resulted in a shorter gelation time which agrees with the results of Lucey et al. (1999). This is probably caused by the higher gelation pH of gels with lower casein to whey protein ratios. Therefore, surface charge of a casein particle would be neutralized at higher pH values resulting in gelation in a shorter time.

In consistent with earlier reports by Lee and Lucey (2004a, 2006) gels formed from solutions heated at higher temperatures had shorter gelation times. This is possibly related to denaturation of whey proteins by heat and their subsequent attachment to κ-casein at the surface of casein particles. The isoelectric pH of whey proteins is higher than that of casein e.g., the main whey protein, β-lactoglobulin has an isoelectric pH of ~5.3 (Phadungath 2005). Hence, surface charge of a casein particle replete with whey proteins would logically be neutralized at higher pH values resulting in gelation at a shorter time. Gelation time increased with decreasing incubation temperature (Arshad et al. 1993; Lucey et al. 1998b, 1999; Lee and Lucey 2004a; Lee and Lucey 2006), presumably because of the decreased rate of hydrolysis of GDL at lower temperatures (Lucey et al. 1997a).

In a RSM approach, after design of experiments, selection of variables’ levels in experimental runs, and fitting the mathematical models, the response of interest is optimized (Chakraborty et al. 2011). Response optimizer of RSM package was used to compute the values of variables in the regression equation (Eq. (2)) to obtain a maximum G′ value of 268.93 Pa. These values were 2.7 % (w/w), 25 °C and 90 °C for casein content, incubation temperature and heating temperature, respectively.

Conclusion

Results obtained in the present research showed that it is possible to modify the gelation behavior of acid-induced casein gels by altering the gelation and heating temperatures and ratio of casein to whey protein. Incubation temperature was the most significant term in determination of G′ of the gel, while; the effect of casein to whey protein ratio had no significant influence on G′. The lower G′ observed for samples gelled at higher incubation temperatures was attributed to the more compact conformation and reduced voluminosity of casein particles at higher temperatures. However, gels formed from solutions heated at higher temperatures before gelation had higher G′ values probably due to the increased disulphide cross-links between denatured whey proteins and casein. Casein content had a direct relation with gelation time and a decrease in casein content resulted in a shorter gelation time.

Information obtained from the present study would be useful in production of acidified milk products with different physical and rheological properties. It may potentially help to solve some difficulties encountered in production of low-fat and non-fat yogurts which exhibit weak body, poor texture and whey separation. Maximization of G′ may modify the rheological properties of these products to meet the standards required in the market.

References

- Arshad M, Paulsson M, Dejmek P. Rheology of buildup, breakdown and rebodying of acid casein gels. J Dairy Sci. 1993;76:3310–3316. doi: 10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(93)77668-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Baş D, Boyaci IH. Modeling and optimization. I. Usability of response surface methodology. J Food Eng. 2007;78:836–845. doi: 10.1016/j.jfoodeng.2005.11.024. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bayraktar E. Response surface optimization of the separation of DL-tryptophan using an emulsion liquid membrane. Process Biochem. 2001;37:169–175. doi: 10.1016/S0032-9592(01)00192-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Braga ALM, Menossi M, Cunha RL. The effect of the glucono-δ-lactone/caseinate ratio on sodium caseinate gelation. Int Dairy J. 2006;16:389–398. doi: 10.1016/j.idairyj.2005.06.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cavallieri ALF, Da Cunha RL. The effects of acidification rate, pH and ageing time on the acidic cold set gelation of whey proteins. Food Hydrocolloids. 2008;22:439–448. doi: 10.1016/j.foodhyd.2007.01.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chakraborty SK, Kumbhar BK, Chakraborty S, Yadav P. Influence of processing parameters on textural characteristics and overall acceptability of millet enriched biscuits using response surface methodology. J Food Sci Technol. 2011;48(2):167–174. doi: 10.1007/s13197-010-0164-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Damin MR, Alcântara MR, Nunes AP, Oliviera MN. Effects of milk supplementation with skim milk powder, whey protein concentrate and sodium caseinate on acidification kinetics, rheological properties and structure of nonfat stirred yogurt. LWT-Food Sci Tech. 2009;42:1744–1750. doi: 10.1016/j.lwt.2009.03.019. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Foegeding EA, Brown J, Drake MA, Daubert CR. Sensory and mechanical aspects of cheese texture. Int Dairy J. 2003;13:585–591. doi: 10.1016/S0958-6946(03)00094-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ginta TL, Amin AKMN, Radzi HCDM, Lajis MA. Tool life prediction by response surface methodology in end milling titanium alloy Ti-6Al-4V using uncoated WC-Co inserts. Eur J Sci Res. 2009;28(4):533–541. [Google Scholar]

- Jelen P, Buchheim W, Peters KH. Heat stability and use of milk with modified casein: whey protein content in yoghurt and cultured milk products. Milchwissenschaft. 1987;42:418–421. [Google Scholar]

- Jha A, Tripathi AD, Alam T, Yadav R (2012) Process optimization for manufacture of pearl millet-based dairy dessert by using response surface methodology (RSM). J Food Sci Technol. doi:10.1007/s13197-011-0347-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Kücükcetin A. Effect of heat treatment and casein to whey protein ratio of skim milk on graininess and roughness of stirred yoghurt. Food Res Int. 2008;41:165–171. doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2007.11.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lee WJ, Lucey JA. Rheological properties, whey separation, and microstructure in set-style yogurt: effects of heating temperature and incubation temperature. J Texture Stud. 2004;34:515–536. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-4603.2003.tb01079.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lee WJ, Lucey JA. Structure and physical properties of yogurt gels: effect of inoculation rate and incubation temperature. J Dairy Sci. 2004;87:3153–3164. doi: 10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(04)73450-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee WJ, Lucey JA. Impact of gelation conditions and structural breakdown on the physical and sensory properties of stirred yogurts. J Dairy Sci. 2006;89:2374–2385. doi: 10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(06)72310-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lucey JA, Munro PA, Singh H. Effects of heat treatment and whey protein addition on the rheological properties and structure of acid skim milk gels. Int Dairy J. 1999;9:275–279. doi: 10.1016/S0958-6946(99)00074-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lucey JA, Tamehana M, Singh H, Munro PA. A comparison of the formation, rheological properties and microstructure of acid skim milk gels made with a bacterial culture or glucono-δ-lactone. Food Res Int. 1998;31:147–155. doi: 10.1016/S0963-9969(98)00075-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lucey JA, Tamehana M, Singh H, Munro PA. Effect of interactions between denatured whey proteins and casein micelles on the formation and rheological properties of acid skim milk gels. J Dairy Res. 1998;65:555–567. doi: 10.1017/S0022029998003057. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lucey JA, van Vliet T, Grolle K, Geurts T, Walstra P. Properties of acid casein gels made by acidification with glucono-δ-lactone. 1. Rheological properties. Int Dairy J. 1997;7:381–388. doi: 10.1016/S0958-6946(97)00027-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lucey JA, Teo CT, Munro PA, Singh H. Rheological properties at small (dynamic) and large (yield) deformations of acid gels made from heated milk. J Dairy Res. 1997;64:591–600. doi: 10.1017/S0022029997002380. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Madadlou A, Emam-Djomeh Z, Mousavi ME, Ehsani M, Javanmard M, Sheehan D. Response surface optimization of an artificial neural network for predicting the size of re-assembled casein micelles. Comput Electron Agr. 2009;68:216–221. doi: 10.1016/j.compag.2009.06.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Madadlou A, Emam-Djomeh Z, Mousavi ME, Mohamadifar M, Ehsani M. Acid-induced gelation behavior of sonicated casein solutions. Ultrason Sonochem. 2010;17(1):153–158. doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2009.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris HA, Ghaleb HM, Smith DE, Bastian ED. A comparison of yoghurts fortified with nonfat dry milk and whey protein concentrates. Cult Dairy Prod. 1995;30(1):2–4. [Google Scholar]

- Phadungath C. The mechanism and properties of acid-coagulated milk gels. Songklanakarin J Sci Tech. 2005;27(2):433–448. [Google Scholar]

- Roefs SPFM, van Vliet T. Structure of acid casein gels. 2. Dynamic measurements and type of interaction forces. Colloid Surface. 1990;50:161–175. doi: 10.1016/0166-6622(90)80260-B. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Smits P, van Brouwershaven JH. Heat-induced association of β-lactoglobulin and casein micelles. J Dairy Res. 1980;47:313–325. doi: 10.1017/S0022029900021208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steffe JF. Rheological methods in food process engineering. 2. East Lansing, USA: Freeman Press; 1996. p. 200. [Google Scholar]

- Sodini I, Lucas A, Tissier JP, Corrieu G. Physical properties and microstructure of yoghurts supplemented with milk protein hydrolysates. Int Dairy J. 2005;15:29–35. doi: 10.1016/j.idairyj.2004.05.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tiwari S, Bhattacharya S (2012) Mango pulp-agar based model gel: textural characterization. J Food Sci Technol. doi:10.1007/s13197-011-0486-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Val-Arreola D, Kebreab E, France J. Modeling small-scale dairy farms in central Mexico using multi-criteria programming. J Dairy Sci. 2006;89:1662–1672. doi: 10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(06)72233-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Vliet T, Keetels CJAM. Effect of preheating of milk on the structure of acidified milk gels. Netherlands Milk Dairy J. 1995;49:27–35. [Google Scholar]

- Yim HS, Chye FY, Rao V, Low JY, Matanjun P, How SE, Ho CW (2012) Optimization of extraction time and temperature on antioxidant activity of Schizophyllum commune aqueous extract using response surface methodology. J Food Sci Technol. doi:10.1007/s13197-011-0349-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]