Abstract

Ongoing intrinsic brain activity in resting, but awake humans is dominated by alpha oscillations. In human, individual alpha frequency (IAF) is associated with cognitive performance. Noticeable, performance in cognitive and emotional tasks in women is associated with menstrual cycle phase and sex hormone levels, respectively. In the present study, we correlated frequency of alpha oscillation in resting women with menstrual cycle phase, sex hormone level, or use of oral contraceptives. Electroencephalogram (EEG) was recorded from 57 women (aged 24.07±3.67 years) having a natural menstrual cycle as well as from 57 women (aged 22.37±2.20 years) using oral contraceptives while they sat in an armchair with eyes closed. Alpha frequency was related to the menstrual cycle phase. Luteal women showed highest and late follicular women showed lowest IAF or center frequency. Furthermore, IAF as well as center frequency correlated negatively with endogenous estradiol level, but did not reveal an association with endogenous progesterone. Women using oral contraceptives showed an alpha frequency similar to women in the early follicular phase. We suggest that endogenous estradiol modulate resting alpha frequency.

Keywords: Estradiol, Individual alpha frequency, Center frequency, Oral contraceptive

Highlights

-

•

Alpha frequency is associated with menstrual cycle phase and estradiol level.

-

•

Lowest alpha frequency correlates with late follicular phase.

-

•

Alpha frequency correlates negatively with estradiol level.

1. Introduction

Fluctuations of estradiol and progesterone during natural menstrual cycles are fundamental in synchronizing cellular activities. In the periphery, sex hormone oscillations synchronize differentiation of ovarian follicles with epithelial maturation in uterus. In the central nervous system, changes in sex hormones are captured in changes in neuronal architecture, excitability, and cognitive processes (McEwen et al., 2012). In women, volume increase in areas of the temporal lobe correlates with elevated estradiol levels (Protopopescu et al., 2008, Pletzer et al., 2010, De Bondt et al., 2013). Estradiol and progesterone are potent neuromodulators. In general, estradiol increases and progesterone decreases neuronal excitability (Finocchi, Ferrari, 2011). Furthermore, estradiol or menstrual cycle phases having elevated levels of estradiol correlate positively with performance in verbal memory tasks, working memory, paired-associate learning, but negatively with performance in spatial tasks (Hampson and Kimura 1992; Phillips and Sherwin, 1992, Hampson 1990, Hausmann et al., 2000, Rosenberg and Park, 2002, Maki et al. 2002).

Ovarian steroid hormone fluctuations correlate with changes in energy balance in reproductively fertile women. In comparison to the follicular phase, energy expenditure and food intake is increased in the luteal phase (Buffenstein et al., 1995). Nutritional and endocrinological studies on rodents, non-human primates and humans revealed that estradiol has an inhibitory impact on food intake (Buffenstein et al., 1995). Although the weight of the brain is 2% of the total body weight, it consumes about 20% of the energy. Task processing increases energy consumption only by about 5% (Raichle, 2010). Critically, more than 90% of cortical neurons are glutamatergic (Braitenberg, Schüz, 1991), and the great majority of energy in the human brain is presumably consumed by excitatory glutamatergic synapses (Attwell and Laughlin, 2001, Raichle, 2010). Synchronized oscillatory activity monitored by the EEG during event related potentials or spontaneous, intrinsic activity is related to synaptic activity (Buzsáki et al., 2012). Interestingly, Hans Berger, who described alpha oscillations for the first time, concluded already in 1929 that “… mental work … adds only a small increment to the cortical work which is going on continuously …” (Berger, 1929, Raichle, 2010). Considering that the majority of energy is consumed in the resting – but awake – brain at glutamatergic synapses, EEG signals represent synchronous activity of glutamatergic synapses, and fluctuations in ovarian steroid hormones determine energy expenditure and food intake in women, we assumed that the frequency of ongoing alpha oscillations is related to the level of estradiol or progesterone.

Women using oral contraceptives differ in their response to specific tasks as well as in their resting state from women having a natural menstrual cycle. Compared to women with a natural menstrual cycle, women using oral contraceptives show a stronger BOLD response to faces in the right fusiform face area (Marecková et al., 2014), but a smaller BOLD response to erotic stimuli in the left precentral gyrus (Abler et al., 2013). In a numerical task, women using oral contraceptives have a BOLD response similar to men (Pletzer et al., 2014). Critically, Petersen and colleagues describe that oral contraceptives as well as endogenous sex hormones are associated with a decrease in connectivity in the resting state network (Petersen et al., 2014). Furthermore, recent voxel-based morphometric studies revealed some areas in the frontal and temporal lobe that were larger in women using oral contraceptives compared to women having a natural menstrual cycle (Pletzer et al., 2010, De Bondt et al., 2013).

Alpha oscillations (8–12 Hz) are the dominant frequency band in the human EEG (Klimesch, 1997). Typically, amplitude of the alpha rhythm is largest with the eyes closed and attenuates when eyes are opened. Accordingly, this alpha desynchronization was interpreted as suppression of sensory input or event-related desynchronization. However, more recently, alpha oscillations are seen as functional as well as physiological inhibition (Klimesch, 1997, 1999). In addition Anokhin and Vogel (1996) pointed out that alpha frequency is positive correlated with intelligence, a finding that has been replicated recently correlating individual alpha frequency and general intelligence g (Grandy et al. 2013).

The aims of the present study were to evaluate the frequency of alpha oscillations in resting state conditions (1) across the menstrual cycle, (2) in relation to endogenous estradiol or progesterone, and (3) in the active and inactive phase of oral contraceptive use.

2. Results

2.1. Alpha oscillations in resting state conditions have a higher frequency in luteal compared to follicular women

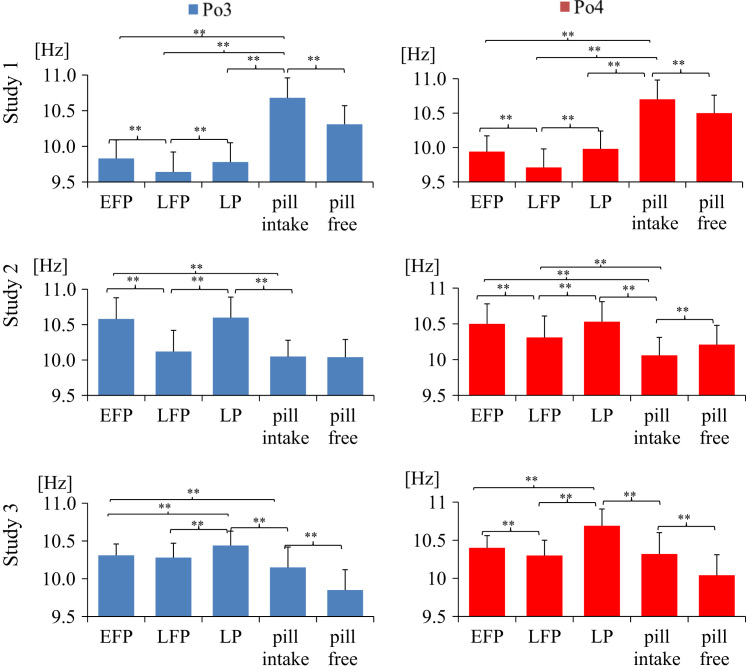

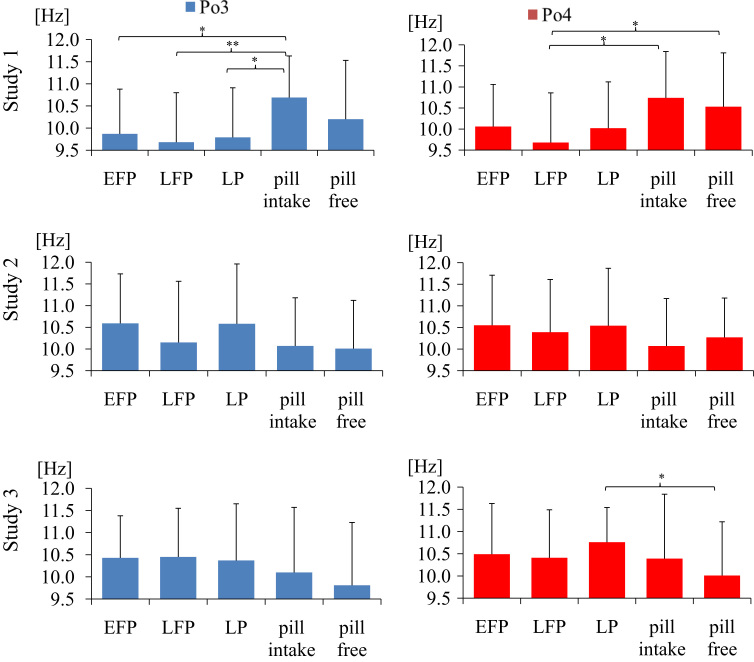

To evaluate whether frequency of ongoing EEG was menstrual cycle-dependent we (1) calculated IAF and center frequency as detailed in Experimental procedures and (2) compared IAF and center frequency in women who participated in three segregated experiments (Tables 1 and 2). Figs. 1 and 2 summarize center frequency and IAF of ongoing EEG in the left and right parieto-occipital cortex. In each of the studies, we identified the slowest center frequency in the late follicular phase and the fastest in the luteal phase. Repeated measures ANOVA, calculated for each study showed a significant difference between cycle phases for Po4 center frequency in study 1 (F(2, 34)=49.235, p=.000, η2=.743), study 2 (F(2, 36)=54.147, p=.000, η2=.751) and study 3 (F(2, 36)=73.849, p=.000, η2=.804). ANOVAs for Po3, P3 and P4 electrodes revealed similar results. As expected, dependent t-tests yielded that women showed significant faster center frequency in the luteal phase compared to late follicular phase in study 1 (Po4 t(17)=−8.913, p=.000), study 2 (Po4 t(18)=−9.476, p=.000), and study 3 (Po4 t(18)=−10.450, p=.000). Center frequency increased by 2–5% (by .1–.5 Hz) from late follicular to luteal phase. Similarly, women showed faster center frequency in the luteal phase compared to early follicular phase in study 1(P3 t(17)=−12.866, p=.000), study 2 (P3 t(18)=−11.604, p=.000) and study 3 (Po4 t(18)=−8.663, p=.000). Repeated measures ANOVA showed a significant difference between cycle phases for P3 IAF in study 2 (F(2, 36)=4.253, p=.037, η2=.191) but not in study 1 (F(2, 34)=1.721, p=.207, η2=.092) and study 3 (F(2, 36)=.557, p=.520, η2=.030). ANOVAs for Po3, P3 and P4 electrodes revealed similar results. Dependent t-tests showed that IAF was faster in luteal compared to late follicular women in study 1 (P3 t(17)=−3.562, p=.002), study 2 (P3 t(18)=−2.241, p=.038), but not in study 3. Center frequency revealed more significant associations than IAF (Figs. 1 and 2). However, we identified a positive correlation between IAF and center frequency in all three studies for women having a natural menstrual cycle as well as for women using hormonal contraceptives (p<.05). For example, in early follicular women IAF (Po3) and center frequency (Po3) correlated positively in study 1 (r(16)=.672, p=.002), in study 2 (r(17)=.705, p=.001), and study3 (r(17)=.714, p=.001). Therefore, the reason why we got statistically significant results preferentially for center frequency compared to IAF is due to the high variance in IAF.

Table 1.

Women with a natural menstrual cycle.

| N | Age range | Mean age±SD | Mean cycle length | Schedule of studies (modusa) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study 1 | 18 | 16–33 | 24.06±4.66 | 29.44±1.9 | September to March (December). |

| Study 2 | 19 | 19–30 | 23.32±3.45 | 27.97±2.32 | December to April (February) |

| Study 3 | 20 | 19–29 | 24.80±2.82 | 30.23±2.47 | April to October (October) |

In study 1, we excluded two women because they had no menstruation since one year and two because of technical problems. For correlational analyses between sex hormones and IAF, one subject was excluded in the late follicular and luteal phase because her estradiol level was more than two standard deviations higher than the mean. In study 2, one subject was excluded because she did not finish the study. For correlational analyses between sex hormones and IAF one subject was excluded in the early follicular and one subject in the late follicular phase because their estradiol level was more than two standard deviations higher than the mean. Furthermore, one subject was excluded in the late follicular and luteal phase and one subject in the luteal phase because their progesterone level was more than two standard deviations higher than the mean. In study 3, one woman was excluded during luteal phase because of inadequate determination of luteal phase. For correlational analyses between sex-hormones and IAF we excluded one participant in each cycle phase because her saliva sample was contaminated with lipstick. One woman was excluded during late follicular and luteal phase because her progesterone level was more than two standard deviations higher than the mean. Furthermore, we had one missing values of progesterone level during early follicular phase because it was too high and, therefore, not quantifiable.

modus: month, in which most women were studied.

Table 2.

Women using oral contraceptives (combination pill).

| N | Age range | Mean age±SD | Oral contraceptives | Schedule of studies (modusa) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study 1 | 17 | 19–26 | 22.53±2.27 | Desogestrel (n=2), Gestoden (n=2), Dienogest (n=4), Drospirenon (n=8), Levonorgestrel (n=1) | October to March (January) |

| Study 2 | 20 | 18–26 | 21.60±2.19 | Desogestrel (n=1), Gestoden (n=3), Dienogest (n=3), Drospirenon (n=8), Levonorgestrel (n=2), Cyproteron (n=3) | November to March (January) |

| Study 3 | 20 | 20–28 | 23±2.03 | Desogestrel (n=1), Gestoden(n=2), Dienogest(n=4), Drospirenon(n=8), Levonorgestrel(n=3), Cyproteron(n=1), Chlormadinon(n=1) | April to October (July) |

Combined oral contraceptive pill contained ethinylestradiol (.015–.035 mg) and different doses of progestins. In study 1, two women were excluded because they use different hormonal contraceptives then the classical combined contraceptive pill and other three because of technical problems. In study 2, one subject was excluded because she did not finished the study. For correlational analyses between sex-hormones and IAF one subject was excluded during pill intake and pill free week because her progesterone level was more than two standard deviations higher than the mean. In study 3, one subject was excluded because she did not finished the study. One more participant was excluded because she is a diabetic and need to regularly inject insulin. For correlational analyses between sex-hormones and IAF two participants were excluded during pill free week because their progesterone level were more than two standard deviations higher than the mean. Furthermore we had one missing values of progesterone level during pill intake phase because it was too high and therefore impossible to measure.

modus: month, in which most women were studied.

Fig. 1.

Average alpha center frequency (M±SD) in women with a natural menstrual cycle and women using oral contraceptives. Late follicular women show lowest center frequency. EFP: early follicular phase, LFP: late follicular phase, LP: luteal phase; pill intake phase: active phase, pill free week: inactive phase; *p<.05; **p<.01.

Fig. 2.

Average IAF (M±SD) in women with a natural menstrual cycle and women using oral contraceptives. Late follicular women reveal lowest IAF. EFP: early follicular phase, LFP: late follicular phase, LP: luteal phase; pill intake phase: active phase, pill free week: inactive phase; *p<.05; **p<.01.

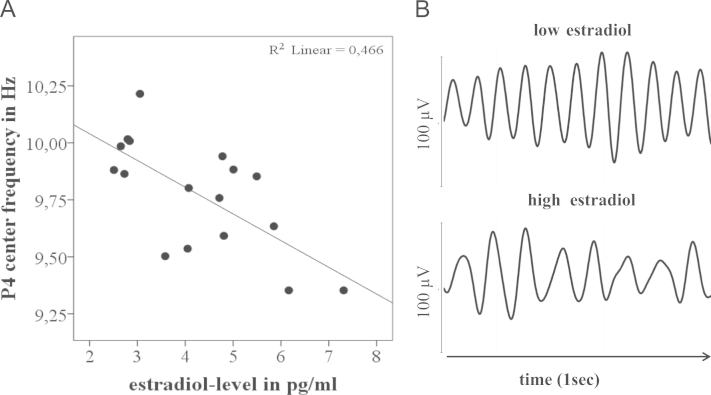

2.2. IAF and center frequency are negatively correlated with estradiol in women having a natural menstrual cycle

Because of the significant association between IAF and center frequency with menstrual cycle phase, we next correlated estradiol and progesterone level with alpha frequency. In general, we found that estradiol was negatively correlated with IAF and with center frequency (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Estradiol level correlates negatively with alpha frequency. (A) The regression line shows a negative correlation between estradiol and center frequency in luteal woman. (B) Alpha oscillation (filtered between 7 and 14 Hz) from late follicular women having either a low estradiol or high estradiol level.

IAF correlated negatively with estradiol in luteal phase in study 1 (P4 r(15)=−.415, p=.098) and study 2 (P4 r(15)=−.483, p=.049) as well as in late follicular phase in study 1 (P3 r(15)=−.468, p=.058) and study 3 (P4 r(16)=−.608, p=.007). Similarly, center frequency correlated negatively with estradiol in luteal phase in study 1 (P4 r(15)=−.683, p=.003), in late follicular phase in study 1 (P4 r(15)=−583, p=.014) and study 3 (P4 r(16)=−.501, p=.034), as well as in early follicular phase in study 1 (P4 r(16)=−503, p=.033). In parietal and parieto-occipital electrodes, the significance of negative correlations between estradiol level and center frequency varied between p=.003 and p=.098. In contrast to estradiol, we did not detect significant correlations (p<.05) between progesterone and IAF or center frequency.

2.3. Oral contraceptives and alpha oscillations

In oral contraceptive users in the active phase, Po3 center frequency ranges between 9.64 and 11.12 Hz with an average of 10.27±.37 (n=57), and in the inactive phase between 9.33 and 10.85 Hz with an average of 10.05±.31 (n=57). In general, center frequency, but not IAF, revealed a significant faster frequency in the active compared to inactive phase of oral contraceptive use (Fig. 1) in study 1 (P3 t(17)=8.961, p=.000), study 2 (P3 t(19)=4.217, p=.000), and study 3 (P3 t(19)=11.315, p=.000). Thus, the impact of oral contraceptives on alpha frequency was reversible within a few days.

In study 2 and 3, the center frequency recorded from parieto-occipital cortex was smaller in women using oral contraceptives (active phase) than in women in the luteal phase (study 2: Po3 t(33)=6.608, p=.000; study 3: Po4 t(37)=4.522, p=.000), but faster than in late follicular women in study 2 (P3 t(37)=−4.491, p=.000). In study 1, women using oral contraceptives (active phase) had a higher center frequency compared to women in the luteal phase (P4 t(33)=−8.850, p=.000). However, in this study, women having a natural menstrual cycle revealed slower center frequency or IAF compared to women in study 2 and study 3 (Figs. 1 and 2). Whether differences in alpha frequencies are related to external factors, like seasonal differences (Tables 1 and 2), remains to be evaluated. Comparison of oral contraceptive-free interval revealed similar results. When we used IAF, we identified a higher IAF during active phase compared to luteal phase in study 1 (P3 t(33)=−2.187, p=.036), but a lower IAF during inactive phase compared to luteal phase in study 3 (Po4 t(37)=2.281, p=.028).

Women using hormonal contraceptives (active phase) are characterized by significantly lower estradiol concentration than normally cycling women during late follicular phase (t(32)=1.991, p=.055) and luteal phase (t(32)=2.062, p=.047) in study 1, during early follicular (t(35)=2.058, p=.047), late follicular (t(34)=4.912, p=.000) and luteal phase (t(34)=3.094, p=.004) in study 2. In contrast to women having a natural menstrual cycle, women using oral contraceptives did not reveal an association between estradiol and alpha frequency (p>.05) in active and inactive phase.

3. Discussion

Our confirmation of previous EEG findings (Becker et al., 1982, Creutzfeldt et al., 1976) in three independent studies demonstrates a robust effect of menstrual cycle on alpha frequency. In addition, we identified a negative correlation between estradiol and frequency of the alpha band. This provides a further hint of the interplay between neural activity and endocrine system. Furthermore, similar to the results of Becker and colleagues (Becker et al., 1982), we find that women using oral contraceptives have an alpha frequency close to early follicular women.

The brain is not a reflexive organ, but intrinsically active. Raichle and colleagues defined a default mode by comparing deviations in the local oxygen extraction fraction with mean hemisphere oxygen extraction fraction (Raichle et al., 2001). These authors identified brain areas tonically active in a baseline state along midline areas, including precuneus, posterior cingulate, and medial prefrontal cortex, as well as in some lateral areas, specifically in parietal cortex. A default system, which is task-independently active, has since then been identified in numerous fMRI and PET studies (Raichle, 2010). The earliest electrophysiological documentation of intrinsic brain activity dates back to 1929, when Hans Berger published ongoing alpha activity in awake but resting individuals with eyes closed (Berger, 1929). We as well as Creutzfeldt and colleagues (Becker et al., 1982, Creutzfeldt et al., 1976) demonstrate reliable cyclic changes in alpha frequencies in women. Since resting alpha frequency is a predictor for cognitive performance (Grandy et al. 2013), menstrual cycle-dependent changes in alpha activity may have functional consequences in performance.

Elevated estradiol correlates with a higher spine density in hippocampal pyramidal neurons in rodents and non-human primates and an increased synaptic excitatory potential in rodents (McEwen, 2010, McEwen et al., 2012). Surprisingly, we identified a negative correlation between estradiol and alpha frequency. This may indicate that these neuroanatomical and physiological findings are more related to EEG amplitudes rather than frequency or to different frequency bands compared to alpha band. Interestingly, an association between low estradiol and fast alpha frequency was also detectable in our study in two participants where menstruation failed to occur at least in the last twelve months. In general, these women had high IAF. One woman showed on both EEG sessions a high IAF of 11.48 Hz and 12.45 Hz, and the second an IAF of 10.99 and 8.06 Hz, respectively. Changes in alpha frequency during the menstrual cycle may be related to the modulatory impact of estradiol and progesterone on synaptic transmission. Noticeably, alpha frequency is lower in late follicular phase compared to early follicular phase or luteal phase. Early follicular phase and luteal phase have in common that levels of estradiol or progesterone are either low (early follicular phase) or high (luteal phase), but the ratio of estradiol to progesterone is similar. In the late follicular phase, the level of estradiol is elevated, but the level of progesterone is low. Thus, the ratio of estradiol to progesterone is high in the late follicular phase. Cyclic changes in sex steroids are paralleled by changes in gene expression in the nervous system. Interestingly, estradiol modulates expression of GABA A receptors as well as glutamate decarboxylase. GABA A receptors are upregulated in proestrus rats, where estradiol is elevated (Puri et al., 2011). Furthermore, the gad2 promotor, required for expression of glutamate decarboxylase, is a target of estradiol receptors (Hudgens et al., 2009). GABAergic synaptic transmission is modulated by progesterone and its metabolites. Accordingly, estradiol-dependent expression of GABA A receptors and the GABA synthesizing enzyme, glutamate decarboxylase, may affect alpha frequency. The modulation of GABAergic transmission may be different when the ratio of estradiol to progesterone is similar, like in early follicular phase and luteal phase, or when the ratio is high, like in the late follicular phase.

Changes in frequency of ongoing alpha oscillations (Becker et al., 1982, present study) and food intake (Lyons et al., 1989, Buffenstein et al., 1995) across the menstrual cycle are in parallel. These studies demonstrate a decrease in food intake during the periovulatory, but an increase in the luteal phase. Our study reveals a decrease in alpha frequency in the late follicular phase compared to the luteal phase. We suggest that this similarity is beyond chance. The human brain weighs 2% of the total body weight, but consumes 20% of the bodies resting energy budget (Raichle, 2010). More than 90% of cortical synapses are glutamatergic (Braitenberg, Schüz, 1991). In the human brain, glutamatergic synapses are the dominant ATP consumers with an estimated 60% to 80% of the energy used by intrinsic brain activity (Attwell and Laughlin, 2001, Raichle, 2010). Accordingly, increase in glutamatergic activity predicts accelerated ATP consumption. If an increase in estradiol is coupled to a decrease in food consumption, a decline in alpha frequency saves energy because synapses are activated less frequently. Interestingly, although estradiol to progesterone ratio changes between late follicular phase and luteal phase, estradiol does not vary that much between these menstrual cycle phases. Individuals low in estradiol have higher IAF and center frequency compared to women high in estradiol. Accordingly, these individuals should differ in metabolism. In preliminary results, we found in the luteal phase a positive correlation between body temperature and center frequency (r(19)=.451, p=.053). Although many women taking a combination pill complain about weight gain as an adverse side effect, meta-studies on this topic did not find empirical evidence (Gupta, 2000, Lindh et al., 2011). Nevertheless, correlative studies between brain and body metabolism in women using oral contraceptives would be of interest to identify the impact of ethinyl estradiol, a synthetic steroid in hormonal contraceptives, on neural activity.

Structure and activity of the brain of women using oral contraceptives differ from those women having a natural menstrual cycle (Pletzer et al., 2010, De Bondt et al., 2013, Pletzer et al., 2014). Critically, differences between oral contraceptive users and non-users are detectable under resting state conditions of the brain. Petersen and colleagues describe a decrease in connectivity in oral contraceptive users and luteal women, suggesting the synthetic hormones in oral contraceptives and endogenous sex hormones have a similar effect on connectivity in the resting state (Petersen et al., 2014). In the present study, we find a similar alpha frequency in oral contraceptive users and early follicular women. If ethinyl estradiol substitute endogenous, consumption of oral contraceptives predict a decrease in center frequency or IAF. Similarity in alpha frequency in oral contraceptive users and early follicular women indicate that either ethinyl estradiol is not as efficient as endogenous estradiol in decreasing alpha frequency or combination of ethinyl estradiol and progestins have an enhancing effect on alpha frequency.

In conclusion, our study demonstrates that menstrual cycle phase and, specifically, estradiol correlates with alpha frequency. Given the importance of menstrual cycle and sex-hormone associated differences in cognitive tasks (Hampson and Kimura, 1992; Phillips and Sherwin, 1992, Hampson, 1990, Hausmann et al., 2000, Rosenberg and Park, 2002, Maki et al., 2002) and the predictor capacity of alpha frequency on task performances (Grandy et al., 2013), modulation of ongoing oscillations by estradiol may be a link between performance and sex hormone changes.

4. Experimental procedures

4.1. Participants

EEG recordings were collected from three subject groups (see Tables 1 and 2). Most women were recruited from the University of Salzburg (Department of Biology, Department of Psychology) and gave their written informed consent. Participants were free of medication and reported no history of neurological disorders. Our studies were approved by the local ethics committee.

4.2. Salivary sex hormone analysis

Estradiol and progesterone were quantified using Demetitec Salivary Estradiol ELISA kids according to the recommendations of the provider. Each participant provided a saliva sample before an EEG-session. Saliva samples were collected in sterile centrifuge tubes, stored in a freezer at −20 °C. Particles in saliva samples were removed by centrifugation (2355 g for 15 min) before sex hormone quantification. Tables 3 and 4 summarize mean and standard deviation of estradiol and progesterone levels.

Table 3.

Mean±SD for estradiol- (E2) and progesterone-level (P) (in pg/ml) for early follicular phase (EFP) late follicular phase (LFP) and luteal phase (LP).

| EFP |

LFP |

LP |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| E2 | P | E2 | P | E2 | P | |

| Study 1 | n (18) 3.94±1.82 | n (18) 62.34±57.74 | n (17) 4.43±2.07 | n (17) 64.76 ±32.21 | n (17) 4.26±1.42 | n (17) 134.67±105.94 |

| Study 2 | n (18) 5.42±2.05 | n (18) 131.15±101.35 | n (17) 7.50±2.43 | n (17) 193.04±87.61 | n (17) 6.74 ±3.20 | n (17) 334.43±104.38 |

| Study 3 | n (19) 8.46±4.13 | n (18) 87.74±54.72 | n (18) 9.81±3.91 | n (18) 95.19±81.66 | n (17) 9.02±3.90 | n (17) 290.79±177.45 |

Table 4.

Mean±SD for estradiol- (E2) and progesterone-level (P) (in pg/ml) for pill intake phase and pill free week.

| Pill intake phase | Pill free week | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| E2 | P | E2 | P | |

| Study 1 | n (17) 3.09±1.84 | n (17) 171.61±138.66 | n (17) 3.86±2.18 | n (17) 137.35±62.93 |

| Study 2 | n (19) 4.19±1.56 | n (19) 77.66±54.57 | n (19) 4.49±1.55 | n (19) 71.45±33.37 |

| Study 3 | n (20) 10.91±4.60 | n (19) 123.16±80.49 | n (18) 10.01±4.08 | n (18) 85.23±53.57 |

4.3. EEG recordings

EEG signals were recorded while women sat in an armchair in a sound-attenuated room with eyes closed for five minutes. Women having a natural menstrual cycle were tested in early (onset of menstruation plus five days) and late follicular phase (approximately 14 days before onset of menstruation) as well as in luteal phase (three days post ovulation to five days before the onset of menstruation). Late follicular phase was estimated by verbal reports and by use of a commercial ovulation tests (Pregnafix®Ovulationstest). About a third of the participants started in early follicular phase, late follicular phase, and luteal phase, respectively. With six exceptions, the three EEG sessions were a maximum of one menstrual cycle apart. Women using hormonal contraceptives were tested twice, once during administration pause (inactive phase) and once during intake of the pill (active phase). About one half of the participants started in the active and the second half in the inactive phase.

4.4. Acquisition of EEG data

32 Ag–AgCl electrodes were used in study 1 and 64 Ag–AgCl electrodes were used in study 2 and study 3, respectively, to record EEG signals. Electrodes were referenced to a nose electrode and a grounding electrode was located on the forehead. Electrode positions were according to the 10–20 system (Jaspers, 1958). Signals were amplified with a BrainAmp amplifier (Brain Products, Inc., Gilching, Germany) using a sampling rate at 1000 Hz. To eliminate 50 Hz oscillation, a notch filter at 50 Hz was applied and recording bandwidth was set from .016 to 100 Hz. Eye movements were controlled by two electrodes set at vertical and horizontal positions near the right eye. Impedance was kept below 8 kΩ.

4.4.1. Data-analysis

EEG data were analyzed using BrainVisionAnalyzer 2.0 (Brain Products, Inc., Gilching, Germany). Raw EEG data were re-referenced to earlobe-electrodes and filtered with an IIR bandpass filter between .5 and 40 Hz in study 1 or .5 and 70 Hz in study 2 and study 3, respectively. Eye artifacts (EOG) were removed using ocular correction based on Gratton and Coles (Gratton et al., 1983). Remaining artifacts were eliminated by skipping bad intervals following visual inspection.

4.4.2. Individual alpha frequency and gravity frequency

Alpha frequency is characterized either as peak or gravity frequency within the traditional alpha frequency band of about 8–12 Hz. Peak frequency was estimated as the spectral component within f1 to f2 which showed the largest power. To calculate the individual alpha frequency (IAF) and the center frequency, respectively, we segmented five minutes resting-conditions eyes closed into consecutive 4000 ms segments and applied a Fast-Fourier-Transformation (FFT) with a .24 Hz resolution using the Hanning window (10%). After averaging, we inspected visually the highest peak of the Po3, Po4, P3 and P4 electrodes within a frequency window from 7 to 14 Hz and noted the peak frequency (IAF). We choose a similar frequency window as Becker et al. (1982) used. Center or gravity frequency is the weighted sum of spectral estimates, divided by alpha power (∑(a(f)×f))/(∑a(f))×a(f) is power spectral estimate at frequency f. Summation ranges from f1 to f2. Gravity or center frequency is more appropriate when multiple peaks are detected in the alpha range (Klimesch, 1999). We calculated the center frequency using MATLAB (R2010b). The frequency window f1 to f2 was defined collectively for each cycle phase or pill intake phase and pill free week as the mean IAF±2 Hz. For example if the mean IAF during early follicular phase is 10.06 Hz than f1 is 8.06 Hz and f2 is 12.06 Hz.

4.5. Statistical methods

PASW Statistics 18 (SPSS) was used for statistical analysis. To test for cycle-dependent differences in center frequency or IAF, a repeated measure ANOVA with the factor IAF or center frequency was calculated separately for each electrode. Dependent t-tests showed differences in center frequency or IAF between individual cycle phases and independent t-tests showed differences between naturally cycling women and women using oral contraceptives. Estradiol levels were associated with center frequency or IAF using the Pearson correlation coefficient (2-tailed).

Acknowledgments

The first author of this paper was financially supported by the Doctoral College “Imaging the Mind” of the Austrian Science Fund (FWF-W1233).

References

- Abler B., Kumpfmüller D., Grön G., Walter M., Stingl J., Seeringer A. Neural correlates of erotic stimulation under different levels of female sexual hormones. PLoS One. 2013;8:e54447. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0054447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anokhin A., Vogel F. EEG alpha rhythm frequency and intelligence in normal adults. Intelligence. 1996;23:1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Attwell D., Laughlin S.B. An energy budget for signaling in the grey matter of the brain. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 2001;21:1133–1145. doi: 10.1097/00004647-200110000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker D., Creutzfeldt O.D., Schwibbe M., Wuttke W. Changes in physiological, EEG and psychological parameters in women during the spontaneous menstrual cycle and following oral contraceptives. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 1982;7:75–90. doi: 10.1016/0306-4530(82)90057-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berger H. Über das Elektrenkephalogramm des Menschen (On the human electroencephalogram) Arch. Psychiatrie Nervenkrankh. 1929;87:527–570. [Google Scholar]

- Braitenberg V., Schüz A. Anatomy of the Cortex. Springer; Berlin: 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Buffenstein R., Poppitt S.D., McDevitt R.M., Prentice A.M. Food intake and the menstrual cycle: a retrospective analysis, with implications for appetite research. Physiol. Behav. 1995;58:1067–1077. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(95)02003-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buzsáki G., Anastassiou C.A., Koch C. The origin of extracellular fields and currents--EEG, ECoG, LFP and spikes. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2012;13:407–420. doi: 10.1038/nrn3241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Creutzfeldt O.D., Arnold P.-M., Becker D., Langenstein S., Tirsch W., Wilhelm H., Wuttke W. EEG changes during spontaneous and controlled menstrual cycles and their correlation with psychological performance. Electroencephalogr. Clin. Neurophysiol. 1976;40:113–131. doi: 10.1016/0013-4694(76)90157-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Bondt T., Jacquemyn Y., Van Hecke W., Sijbers J., Sunaert S., Parizel P.M. Regional gray matter volume differences and sex-hormone correlations as a function of menstrual cycle phase and hormonal contraceptives use. Brain Res. 2013;1530:22–31. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2013.07.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finocchi C., Ferrari M. Female reproductive steroids and neuronal excitability. Neurol. Sci. 2011;32:31–35. doi: 10.1007/s10072-011-0532-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grandy T.H., Werkle-Bergner M., Chicherio C., Lövdén M., Schmiedek F., Lindenberger U. Individual alpha peak frequency is related to latent factors of general cognitive abilities. NeuroImage. 2013;79:10–18. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2013.04.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gratton G., Coles M.G., Donchin E. A new method for off-line removal of ocular artifact. Electroencephalogr. Clin. Neurophysiol. 1983;55:468–484. doi: 10.1016/0013-4694(83)90135-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta S. Weight gain on the combined pill--is it real? Hum. Reprod. Update. 2000;6:427–431. doi: 10.1093/humupd/6.5.427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hampson E. Variations in sex-related cognitive abilities across the menstrual cycle. Brain Cogn. 1990;14:26–43. doi: 10.1016/0278-2626(90)90058-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hampson E., Kimura D. Sex differences and hormonal influences on cognitive function in humans. In: Becker J.B., Breedlove S.M., Crews D., editors. Behavioral Endocrinology. MIT Press/Bradford Books; Cambridge, MA: 1992. pp. 357–398. [Google Scholar]

- Hausmann M., Slabbekoorn D., Van Goozen S.H., Cohen-Kettenis P.T., Güntürkün O. Sex hormones affect spatial abilities during the menstrual cycle. Behav. Neurosci. 2000;114:1245–1250. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.114.6.1245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hudgens E.D., Ji L., Carpenter C.D., Petersen S.L. The gad2 promoter is a transcriptional target of estrogen receptor (ER)alpha and ER beta: a unifying hypothesis to explain diverse effects of estradiol. J. Neurosci. 2009;29:8790–8797. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1289-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jasper H.H. The ten-twenty electrode system of the International Federation. Electroencephalogr. Clin. Neurophysiol. 1958;10:371–375. [Google Scholar]

- Klimesch W. EEG-alpha rhythms and memory processes. Int. J. Psychophysiol. 1997;26:319–340. doi: 10.1016/s0167-8760(97)00773-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klimesch W. EEG alpha and theta oscillations reflect cognitive and memory performance: a review and analysis. Brain Res. Rev. 1999;29:169–195. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0173(98)00056-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindh I., Ellström A.A., Milsom I. The long-term influence of combined oral contraceptives on body weight. Hum. Reprod. 2011;26:1917–1924. doi: 10.1093/humrep/der094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyons P.M., Truswell A.S., Mira M., Vizzard J., Abraham S.F. Reduction of food intake in the ovulatory phase of the menstrual cycle. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 1989;49:1164–1168. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/49.6.1164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maki P.M., Rich J.B., Rosenbaum R.S. Implicit memory varies across the menstrual cycle: estrogen effects in young women. Neuropsychologia. 2002;40:518–529. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3932(01)00126-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marecková K., Perrin J.S., Nawaz Khan I., Lawrence C., Dickie E., McQuiggan D.A., Paus T. Hormonal contraceptives, menstrual cycle and brain response to faces. Soc. Cogn. Affect. Neurosci. 2014;9:191–200. doi: 10.1093/scan/nss128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McEwen B.S. Stress, sex, and neural adaptation to a changing environment: mechanisms of neuronal remodeling. Ann. N.Y. Acad. Sci. 2010;1204:38–59. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2010.05568.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McEwen B.S., Akama K.T., Spencer-Segal J.L., Milner T.A., Waters E.M. Estrogen effects on the brain: actions beyond the hypothalamus via novel mechanisms. Behav. Neurosci. 2012;126:4–16. doi: 10.1037/a0026708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petersen N., Kilpatrick L.A., Goharzad A., Cahill L. Oral contraceptive pill use and menstrual cycle phase are associated with altered resting state functional connectivity. Neuroimage. 2014;90:24–32. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2013.12.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips S.M., Sherwin B.B. Variations in memory function and sex steroid hormones across the menstrual cycle. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 1992;17:497–506. doi: 10.1016/0306-4530(92)90008-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pletzer B., Kronbichler M., Aichhorn M., Bergmann J., Ladurner G., Kerschbaum H.H. Menstrual cycle and hormonal contraceptive use modulate human brain structure. Brain Res. 2010;1348:55–62. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2010.06.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pletzer B., Kronbichler M., Nuerk H.C., Kerschbaum H. Hormonal contraceptives masculinize brain activation patterns in the absence of behavioral changes in two numerical tasks. Brain Res. 2014;1543:128–142. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2013.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Protopopescu X., Butler T., Pan H., Root J., Altemus M., Polanecsky M., McEwen B., Silbersweig D., Stern E. Hippocampal structural changes across the menstrual cycle. Hippocampus. 2008;18:985–988. doi: 10.1002/hipo.20468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puri J., Bellinger L.L., Kramer P.R. Estrogen in cycling rats alters gene expression in the temporomandibular joint, trigeminal ganglia and trigeminal subnucleus caudalis/upper cervical cord junction. J. Cell. Physiol. 2011;226:3169–3180. doi: 10.1002/jcp.22671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raichle M.E. Two views of brain function. Trends Cogn. Sci. 2010;14:180–190. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2010.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raichle M.E., MacLeod A.M., Snyder A.Z., Powers W.J., Gusnard D.A., Shulman G.L. A default mode of brain function. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2001;98:676–682. doi: 10.1073/pnas.98.2.676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg L., Park S. Verbal and spatial functions across the menstrual cycle in healthy young women. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2002;27:835–841. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4530(01)00083-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]