Abstract

Background and Aims:

Transversus abdominis plane (TAP) block has been shown to provide postoperative pain relief following various abdominal and inguinal surgeries, but few studies have evaluated its analgesic efficacy for intraoperative analgesia. We evaluated the efficacy of TAP block in providing effective perioperative analgesia in total abdominal hysterectomy in a randomized double-blind controlled clinical trial.

Materials and Methods:

A total of 90 adult female patients American Society of Anesthesiologists physical status I or II were randomized to Group B (n = 45) receiving TAP block with 0.25% bupivacaine and Group N (n = 45) with normal saline followed by general anesthesia. Hemodynamic responses to surgical incision and intraoperative fentanyl consumption were noted. Visual analog scale (VAS) scores were assessed on the emergence, at 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6 and 24 h. Time to first rescue analgesic (when VAS ≥4 cm or on demand), duration of postoperative analgesia, incidence of postoperative nausea-vomiting were also noted.

Results:

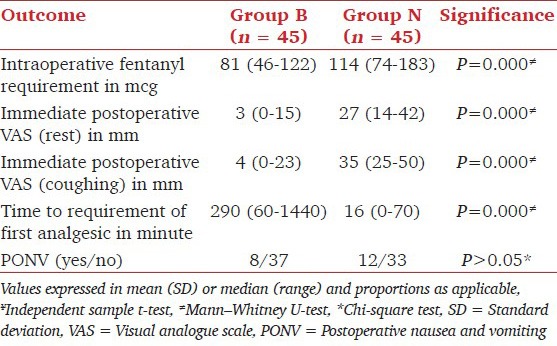

Pulse rate (95.9 ± 11.2 bpm vs. 102.9 ± 8.8 bpm, P = 0.001) systolic and diastolic BP were significantly higher in Group N. Median intraoperative fentanyl requirement was significantly higher in Group N (81 mcg vs. 114 mcg, P = 0.000). VAS scores on emergence at rest (median VAS 3 mm vs 27 mm), with activity (median 8 mm vs. 35 mm) were significantly lower in Group B. Median duration of analgesia was significantly higher in Group B (290 min vs. 16 min, P = 0.000). No complication or opioid related side effect attributed to TAP block were noted in any patient.

Conclusion:

Preincisional TAP block decreases intraoperative fentanyl requirements, prevents hemodynamic responses to surgical stimuli and provides effective postoperative analgesia.

Keywords: Abdominal hysterectomy, perioperative analgesia, transversus abdominis plane block

Introduction

Transversus abdominis plane (TAP) block is a widely practiced peripheral nerve block, utilized to anesthetize the somatic nerves supplying the anterior abdominal wall by depositing local anesthetic in the neurovascular plane between internal oblique and transversus abdominis muscle layers. It was introduced in anesthesia practice in 2001 by Rafi utilizing the traditional anatomical land marks.[1] TAP block has subsequently been used as a component of multimodal analgesia for postoperative pain relief following various surgical procedures such as large bowel resection,[2] open appendectomy,[3] retropubic prostatectomy,[4] nephrectomy,[5] hernia repair,[6] laparoscopic cholecystectomy[7,8] and cesarean section.[9]

Although Carney et al.[10] and Atim et al.[11] have observed analgesic benefit of TAP block in total abdominal hysterectomy by landmark based approach and ultrasound guided (USG) approach respectively, Griffith et al. found that TAP block does not confer any definite analgesic benefit in major gynecological procedures[12] over a multimodal analgesic regimen. Furthermore, the effect of preincisional TAP block on intraoperative as well as postoperative analgesia in patients undergoing total abdominal hysterectomy remains yet to be elucidated.

Based on these observations, this study was conceptualized to elucidate the efficacy of bilateral preincisional TAP block as a component of multimodal analgesia for providing perioperative pain relief in patients undergoing total abdominal hysterectomy.

Materials and Methods

After obtaining approval by the institute ethics committee and written informed consent, 90 adult female patients of American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) physical status (PS) I or II, scheduled for total abdominal hysterectomy by a lower abdominal transverse incision were recruited in this randomized double-blind controlled clinical trial. Unwilling patients and patients with body mass index >30 kg/m2, compromised renal and liver function, uncontrolled diabetes, severe cardiovascular, respiratory disease, having a history of allergy to any of the study drug, and history of abdominal surgery were excluded from the study.

Primary outcome of our study was immediate postoperative visual analogue scale (VAS). Secondary outcomes were intraoperative fentanyl requirement and hemodynamic changes, postoperative hemodynamic changes and time to request first postoperative analgesic.

A thorough review of related literature was performed from standard textbooks and an internet search of related articles was performed PubMed. Sample size was calculated on the basis that a 20 mm difference in the mean VAS between the two groups would be clinically useful. We used PS Power and Sample Size Calculations Software, version 3.0 [Department of Biostatistics, Vanderbilt School of Medicine, Nashville, TN].

We assumed a standard deviation of 30 mm as a standard deviation of VAS score in the population. Forty one patients in each group would be needed, assuming the probability of alpha (α) error is 5% and a power of the study is 85%. Assuming a probable drop out of 10%, 90 patients were recruited. Patients were randomly allocated into two equal groups of 45 patients in each group using a random number generators in Microsoft Excel™ 2003 [Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA] and allocation concealment were maintained by using an opaque sealed envelope technique.

Standard ASA monitoring was used. Baseline parameters such as heart rate, continuous electrocardiogram, noninvasive blood pressure, SpO2 were noted down. Patients were randomly allocated into two groups, Group B or Group N to receive one of the following solutions for bilateral TAP block.

Group B: Injection bupivacaine, 0.25% (0.5 ml/kg body weight on each side).

Group N: Injection normal saline (0.5 ml/kg body weight on each side).

The anesthesiologist, who prepared the solution in identical syringes, remained unaware of the nature of the study and was not involved in further data collection.

The lumbar triangle of Petit, located just anterior to the latissimus dorsi muscle was identified by palpating the iliac crest in an anterior to posterior direction, until the edge of the latissimus dorsi was felt. The skin was pierced just cephalic to the iliac crest over the triangle of Petit with a blunt 18 gauge Tuhoy needle [Smiths Medical International Limited, Hythe, Kent, UK] after infiltration with 2% lignocaine. The block was administered following the technique advocated by McDonnell et al.[2] The needle was advanced perpendicular to the skin in the coronal plane until the first resistance of external oblique muscle was encountered. Gentle advancement of the needle resulted in a pop sensation as the needle entered the plane between the external and internal oblique fascial layers. A second resistance was felt as the needle passed through the internal oblique muscle. A second loss of resistance was encountered when the needle reaches the transversus abdominis fascial plane between the internal oblique and transversus abdominis muscle. A test dose of 1 ml was injected to determine resistance to flow and confirm the needle tip placement within the neurovascular plane. After this one of the study solutions was injected on each side following careful aspiration to exclude vascular puncture.

Ten min after TAP block, all patients received a standardized general anesthesia with fentanyl 1 mcg/kg, propofol and atracurium. Bispectral index (BIS) was maintained within a range of 40-60. They were monitored for any signs of inadequate analgesia in the intraoperative period such as sweating, lacrimation, tachycardia (>100/min) and hypertension (>20% elevation of baseline mean arterial pressure) and supplemental doses of injection fentanyl 0.5 mcg/kg were given as needed. An anesthesiologist who was unaware about the patient allocation did recording of intraoperative hemodynamic data and other anesthesia management. Intravenous infusion of paracetamol (1 g to patients with body weight >40 kg and 750 mg to patients with body weight <40 kg) was given 30 min prior to completion of surgery. Prophylactic antiemetics were not given in any patients.

Fluid deficit arising from preoperative fasting was corrected by maintenance fluid. Blood loss and other plasma losses were approximately calculated from mops and suction drain bottles. Blood losses up to the transfusion threshold were replaced with 3 ml of Ringer's lactate for each ml of blood loss.

After the patient had adequately recovered from anesthesia, and was able to assess pain, postoperative analgesia was assessed with VAS 0-100 mm in the immediate postoperative period (when the patient was able to communicate in the postanesthesia care unit), at 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6 and 24 h and whenever the patient complained of pain. The time of administration of rescue analgesic in the form of injection tramadol 2 mg/kg intravenous (IV) was noted when VAS >40 mm. VAS score was assessed in both rest and movement (knee flexion) by an independent observer who was unaware about the allocation. After administration of rescue analgesic, patients were shifted to a postoperative analgesic regimen of injection tramadol IV 2 mg/kg 8 hourly and injection paracetamol 6 hourly up to 24 h.

The incidence of postoperative nausea and vomiting was noted during the first 24 h. Rescue antiemetics were given to any patient who complained of nausea or vomiting. Any signs of adverse effects of the technique like local site infection, hematoma formation, local anesthetic toxicity due to intravascular injection of anesthetic (like dizziness, tinnitus, perioral numbness and tingling, lethargy, seizures, signs of cardiac toxicity like atrio-ventricular conduction block, arrhythmias, myocardial depression and cardiac arrest), peritoneal perforation, bowel perforation, difficulty ambulating or fall and injury secondary to spread of local anesthetic to nerves of the buttock, lateral thigh or leg in the distribution of the femoral nerve were sought for.[13]

All raw data were entered into a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet and analyzed using standard statistical software. Continuous numerical data were expressed as mean and standard deviation (for normally distributed data), or median and inter-quartile range (for data that are not normally distributed). Categorical data were expressed as frequencies and percentages.

Normally distributed numerical data between groups were analyzed using the Student's t-test. Skewed data between groups were analyzed using the Mann–Whitney U-test. Categorical variables were analyzed using the Fisher's exact test or the Pearson's Chi-square test as applicable. All tests were two-tailed. P < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

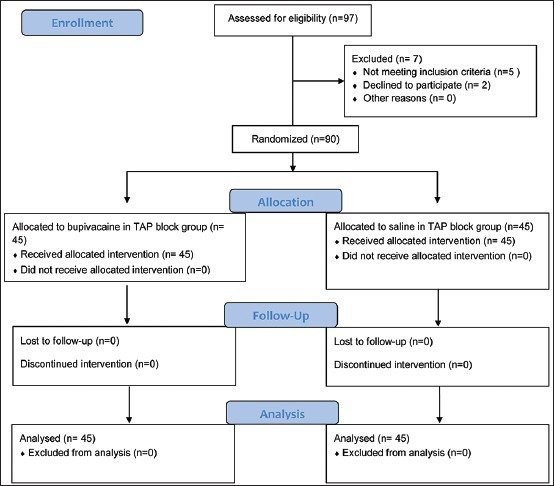

Ninety patients were recruited for the trial and data from all of them has been analyzed. A CONSORT flow diagram depicting the passage of participants through the trial has been provided in Figure 1. The two groups were comparable in terms of baseline demographic parameters (age, sex and body weight), duration of surgery and anesthesia and preoperative hemodynamic parameters (pulse rate, systolic and diastolic blood pressure, respiratory rate) and the volume of the study drug required in TAP block. A summary of base line characteristics of the patients has been furnished in Table 1.

Figure 1.

CONSORT flow diagram for patient selection

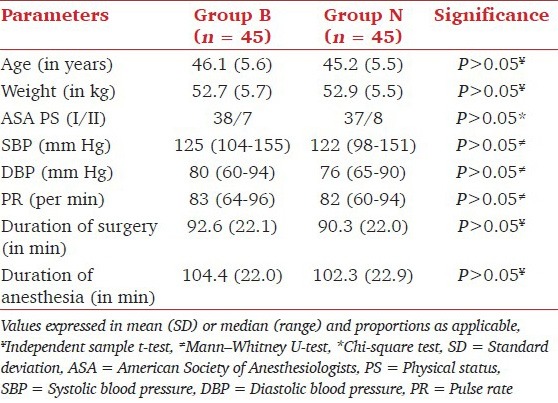

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of the patients in each group

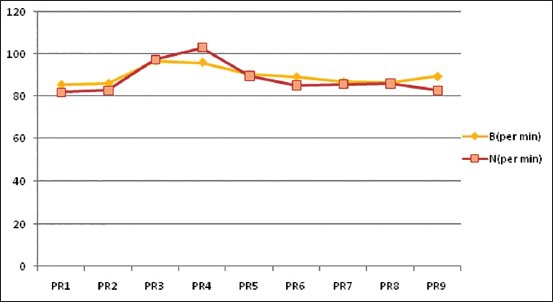

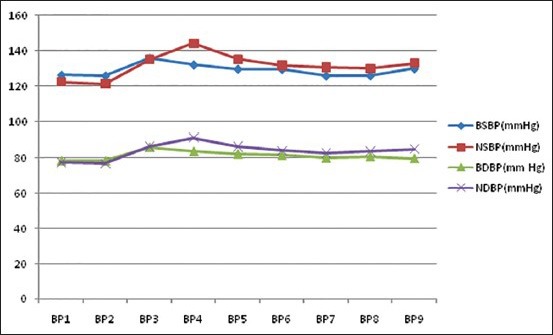

From the analysis of the intraoperative hemodynamic parameters it was found that pulse rate was significantly higher in patients receiving placebo (95.9 ± 11.2 bpm vs. 102.9 ± 8.8 bpm, mean the difference 7.0 s, P = 0.001) after surgical skin incision. Both systolic and diastolic blood pressure after surgical skin incision was also significantly higher in patients receiving placebo, but similar at all other time points. Intraoperative hemodynamic changes have been graphically plotted in Figures 2 and 3.

Figure 2.

Comparison of mean preoperative and intraoperative pulse rate, B = Group B, N = Group N, PR1 = 10 min after TAP block, PR2 = Before induction, PR3 = After induction, PR4 = After incision, PR5 = 15 min intraoperative, PR6 = 30 min intraoperative, PR7 = 60 min intraoperative, PR8 = 90 min intraoperative, PR9 = 120 min intraoperative

Figure 3.

Comparison of mean preoperative and intraoperative systolic blood pressure and diastolic blood pressure. BSBP = Systolic blood pressure of Group B, NSBP = Systolic blood pressure of Group N, BDBP = Diastolic blood pressure of Group B, NDBP = Diastolic blood pressure of Group N, BP1 = 10 min after TAP block, BP2 = Before induction, BP3=after induction, BP4 = After incision, BP5 = 15 min intraoperative, BP6 = 30 min intraoperative, BP7 = 60 min intraoperative, BP8 = 90 min intraoperative, BP9 = 120 min intraoperative

Median requirement of intraoperative fentanyl was significantly higher in patients receiving placebo in comparison to bupivacaine in TAP block (81 mcg vs. 114 mcg, P = 0.000, Mann–Whitney U-test). The difference between the medians is 32.0 mcg with a 95% confidence interval (CI) of 22.0, 42.5 (Hodges–Lehman median difference).

There was no statistically significant difference between the two groups in terms of median values of immediate postoperative pulse rate, systolic blood pressure and diastolic blood pressure (Mann–Whitney U-test). Postoperative oxygen saturation varied from 97% to 100% in all patients of both Groups B and N.

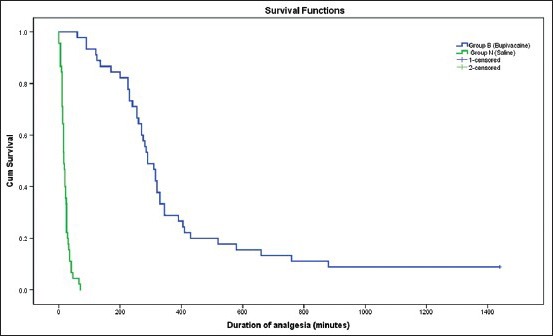

VAS scores in the immediate postoperative period both at rest (median VAS 3 mm vs. 27 mm) and with activity (median 8 mm vs. 35 mm) were significantly lower in patients who received TAP block. Median duration of analgesia was significantly higher in patients belonging to Group B (290 min vs. 16 min, P = 0.000, Mann–Whitney U-test). The difference in median duration of analgesia is 275 min with 95% CI of 250–307 min (Hodges–Lehman median difference). These findings have summarized in Table 2. A Kaplan–Meier survival analysis for the cumulative duration of analgesia in first 24 h shows a significantly longer duration of analgesia in patients receiving TAP block [Figure 4].

Table 2.

Comparison of quality of analgesia

Figure 4.

Duration of analgesia in either group has been depicted in by Kaplan Meyer survival analysis. The survival graph shows significant cumulative analgesia in patients receiving transversus abdominis plane block

Incidence of postoperative nausea-vomiting was also similar in both groups. No opioid related side effects such as respiratory depression, pruritus or urinary retention was noted in any of the patients. None of the patients in either group had any complication that can be attributed to TAP block.

Median value of pulse rate, systolic blood pressure, diastolic blood pressure, VAS scores at 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6 and 24 h were not compared as >30% patients in Group N received rescue analgesic during the immediate postoperative period.

Discussion

The principal finding of our study is that bupivacaine in TAP block provides effective intraoperative and immediate postoperative analgesia in patients undergoing total abdominal hysterectomy.

Our finding of preincisional TAP block reducing intraoperative fentanyl requirement was consistent with those of Mukhtar and Khattak[14] who reported a significant reduction in intraoperative morphine consumption in patients receiving TAP block with 0.5% bupivacaine in renal transplant recipients (0.4 ± 1.2 mg vs. 9.3 ± 1.4 mg; P < 0.0001). El-Dawlatly et al.[7] reported a similar significant reduction in intraoperative sufentanil consumption in patients undergoing laparoscopic cholecystectomy (8.6 ± 3.5 mcg vs. 23.0 ± 4.8 mcg, P < 0.01). Similar findings were reported in a study by Ra et al.[15] in patients undergoing laparoscopic cholecystectomy where intraoperative remifentanil use was significantly lower in patients receiving either 0.5% or 0.25% bupivacaine in comparison to placebo.

However, no other RCT, to the best of our knowledge has addressed the efficacy of preincisional TAP block in preventing hemodynamic response to surgical stimuli.

We have found the superiority of TAP block in providing immediate postoperative analgesia reflected by a lower VAS score both at rest and with activity. The current literature on TAP block is not unanimous in the matter that whether it improves postoperative pain score or not. Our finding is consistent with those of McDonnell et al.[2] in abdominal surgery and Carney et al.[3] in open appendicectomy. In 2008, Carney et al.[10] found that anatomical TAP block in total abdominal hysterectomy patients significantly reduces postoperative pain scores up to 48 h period. Postoperative morphine consumption also decreased at 12 h, 36 h and 48 h time period. However, the authors did not address intraoperative opioid requirement. Recently, Sharma et al.[16] also found that TAP block by landmark technique improves VAS score in first 24 h in patients undergoing major abdominal surgery. Petersen et al.[8] in 2012 also found that US guided bilateral TAP block in patients undergoing laparoscopic cholecystectomy provides superior postoperative pain scores. Petersen et al.[17] in 2013 found that TAP block does not provide superior analgesia in comparison to placebo after inguinal hernia repair. A previous Cochrane review[18] and a meta-analysis[19] in 2012 failed to demonstrate the beneficial effect of TAP block on postoperative pain scores. In this context, it is worth mentioning that the meta-analysis found that TAP block decreases postoperative opioid consumption, which may be a more important parameter to decide an analgesic regimen.

The median duration of effective postoperative analgesia from our study was 290 min in patients receiving TAP block, and we did not use any additive in TAP block. Clonidine in peripheral nerve block has been shown to significantly increase the duration[20] and may be considered here also.

Time to the requirement of first postoperative analgesic is also significantly increased in patients received TAP block (290 min vs. 16 min). This was consistent with McDonnell et al.,[21] who demonstrated in their anatomic study that TAP block with 0.5% lignocaine may provide analgesia for 4-6 h.

Only three patients in bupivacaine TAP group required rescue analgesic in first two postoperative hours whereas 43 patients in the saline group required the same. Four patients in bupivacaine group did not require rescue analgesia in first 24 h postoperative period. The cause of prolonged duration of analgesic effect following single shot TAP block is not entirely clear. This may be explained by the fact that the TAP is relatively poorly vascularized, and therefore drug clearance may be slowed.[10]

Inadequate analgesia even after TAP block may be either due to technical failure or due to visceral pain component, which is not addressed by TAP block. We found a 6.67% of inadequate analgesia in first 2 h postoperative period. As such, until now, all local anesthetic techniques carry an inherent failure rate of 5-20%, depending on the skill of the operator.[22]

The most important clinical implication of our findings is the significant opioid sparing effects of TAP block both in the intraoperative as well as the postoperative period. Opioids, though very effective in perioperative pain management, may be associated with nausea-vomiting, pruritus and respiratory depression. Moreover, some patients who are morbidly obese or having obstructive sleep apnea will be maximally benefitted from TAP block as it provides opioid sparing effects. Besides this, TAP block also prevents the hemodynamic responses of surgical incision. Patients having ischemic heart disease or stenotic valvular lesion like mitral or aortic stenosis, where tachycardia is undesirable, will also be benefitted from preincisional TAP block. It may be a relatively safer alternative to neuraxial block for intra and postoperative analgesia in patients having coagulopathy.

Our study has a few limitations. First, it is difficult to define inadequate analgesia in the intraoperative period. Though we controlled the depth of anesthesia by BIS monitoring, ensured adequate muscle relaxation, prevented hypovolemia, indirect assessment of intraoperative pain by hemodynamic parameters may be unreliable. Second use of real time USG for TAP block is increasing; we used a landmark based anatomical approach. However, as real time US guidance may increase the efficacy of TAP block, it won’t change the primary finding of our study. Third, use of patient controlled analgesia in the postoperative period could have accurately delineated postoperative opioid consumption.

Conclusions

Preincisional TAP block decreases intraoperative fentanyl requirements, prevents hemodynamic responses to surgical stimuli and also provides effective postoperative analgesia. The anatomical approach of TAP block is also very safe and reasonably effective.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Rafi AN. Abdominal field block: A new approach via the lumbar triangle. Anaesthesia. 2001;56:1024–6. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2044.2001.02279-40.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McDonnell JG, O’Donnell B, Curley G, Heffernan A, Power C, Laffey JG. The analgesic efficacy of transversus abdominis plane block after abdominal surgery: A prospective randomized controlled trial. Anesth Analg. 2007;104:193–7. doi: 10.1213/01.ane.0000250223.49963.0f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Carney J, Finnerty O, Rauf J, Curley G, McDonnell JG, Laffey JG. Ipsilateral transversus abdominis plane block provides effective analgesia after appendectomy in children: A randomized controlled trial. Anesth Analg. 2010;111:998–1003. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0b013e3181ee7bba. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.O’Donnell BD, McDonnell JG, McShane AJ. The transversus abdominis plane (TAP) block in open retropubic prostatectomy. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2006;31:91. doi: 10.1016/j.rapm.2005.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hosgood SA, Thiyagarajan UM, Nicholson HF, Jeyapalan I, Nicholson ML. Randomized clinical trial of transversus abdominis plane block versus placebo control in live-donor nephrectomy. Transplantation. 2012;94:520–5. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e31825c1697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Aveline C, Le Hetet H, Le Roux A, Vautier P, Cognet F, Vinet E, et al. Comparison between ultrasound-guided transversus abdominis plane and conventional ilioinguinal/iliohypogastric nerve blocks for day-case open inguinal hernia repair. Br J Anaesth. 2011;106:380–6. doi: 10.1093/bja/aeq363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.El-Dawlatly AA, Turkistani A, Kettner SC, Machata AM, Delvi MB, Thallaj A, et al. Ultrasound-guided transversus abdominis plane block: Description of a new technique and comparison with conventional systemic analgesia during laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Br J Anaesth. 2009;102:763–7. doi: 10.1093/bja/aep067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Petersen PL, Stjernholm P, Kristiansen VB, Torup H, Hansen EG, Mitchell AU, et al. The beneficial effect of transversus abdominis plane block after laparoscopic cholecystectomy in day-case surgery: A randomized clinical trial. Anesth Analg. 2012;115:527–33. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0b013e318261f16e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McDonnell JG, Curley G, Carney J, Benton A, Costello J, Maharaj CH, et al. The analgesic efficacy of transversus abdominis plane block after cesarean delivery: A randomized controlled trial. Anesth Analg. 2008;106:186–91. doi: 10.1213/01.ane.0000290294.64090.f3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Carney J, McDonnell JG, Ochana A, Bhinder R, Laffey JG. The transversus abdominis plane block provides effective postoperative analgesia in patients undergoing total abdominal hysterectomy. Anesth Analg. 2008;107:2056–60. doi: 10.1213/ane.0b013e3181871313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Atim A, Bilgin F, Kilickaya O, Purtuloglu T, Alanbay I, Orhan ME, et al. The efficacy of ultrasound-guided transversus abdominis plane block in patients undergoing hysterectomy. Anaesth Intensive Care. 2011;39:630–4. doi: 10.1177/0310057X1103900415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Griffiths JD, Middle JV, Barron FA, Grant SJ, Popham PA, Royse CF. Transversus abdominis plane block does not provide additional benefit to multimodal analgesia in gynecological cancer surgery. Anesth Analg. 2010;111:797–801. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0b013e3181e53517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jankovic Z, Ahmad N, Ravishankar N, Archer F. Transversus abdominis plane block: How safe is it? Anesth Analg. 2008;107:1758–9. doi: 10.1213/ane.0b013e3181853619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mukhtar K, Khattak I. Transversus abdominis plane block for renal transplant recipients. Br J Anaesth. 2010;104:663–4. doi: 10.1093/bja/aeq077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ra YS, Kim CH, Lee GY, Han JI. The analgesic effect of the ultrasound-guided transverse abdominis plane block after laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Korean J Anesthesiol. 2010;58:362–8. doi: 10.4097/kjae.2010.58.4.362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sharma P, Chand T, Saxena A, Bansal R, Mittal A, Shrivastava U. Evaluation of postoperative analgesic efficacy of transversus abdominis plane block after abdominal surgery: A comparative study. J Nat Sci Biol Med. 2013;4:177–80. doi: 10.4103/0976-9668.107286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Petersen PL, Mathiesen O, Stjernholm P, Kristiansen VB, Torup H, Hansen EG, et al. The effect of transversus abdominis plane block or local anaesthetic infiltration in inguinal hernia repair: A randomised clinical trial. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 2013;30:415–21. doi: 10.1097/EJA.0b013e32835fc86f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Charlton S, Cyna AM, Middleton P, Griffiths JD. Perioperative transversus abdominis plane (TAP) blocks for analgesia after abdominal surgery. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010:CD007705. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007705.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Johns N, O’Neill S, Ventham NT, Barron F, Brady RR, Daniel T. Clinical effectiveness of transversus abdominis plane (TAP) block in abdominal surgery: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Colorectal Dis. 2012;14:e635–42. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1318.2012.03104.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kohli S, Kaur M, Sahoo S, Vajifdar H, Kohli P. Brachial plexus block: Comparison of two different doses of clonidine added to bupivacaine. J Anaesthesiol Clin Pharmacol. 2013;29:491–5. doi: 10.4103/0970-9185.119147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McDonnell JG, O’Donnell BD, Farrell T, Gough N, Tuite D, Power C, et al. Transversus abdominis plane block: A cadaveric and radiological evaluation. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2007;32:399–404. doi: 10.1016/j.rapm.2007.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Galante D, Caruselli M, Dones F, Meola S, Russo G, Pellico G, et al. Ultrasound guided transversus abdominis plane (TAP) block in pediatric patients: Not only a regional anesthesia technique for adults. Anaesth Pain Intensive Care. 2012;16:201–4. [Google Scholar]