Abstract

Human hantaviral disease is mediated by excessive proinflammatory and CD8+ T cell responses, which can be alleviated by administration of corticosteroids. In contrast to humans, male rats that are infected with their species-specific hantavirus, Seoul virus (SEOV), have reduced proinflammatory and elevated regulatory T cell responses in tissues where virus persists. To determine the effects of glucocorticoids on SEOV persistence and immune responses during infection, male and female Norway rats received sham surgeries (sham) or were adrenalectomized (ADX0), in some of which corticosterone was replaced at low (ADX10) or high (ADX80) doses. Rats were inoculated with SEOV and serum corticosterone, SEOV RNA, gene expression, and protein production were measured at different timepoints post-inoculation (p.i.). We observed that SEOV infection suppressed corticosterone in sham males to concentrations seen in ADX0 males. Furthermore, males with low corticosterone had more SEOV RNA in the lungs than either females or males with high corticosterone concentrations during peak infection. Although high concentrations of corticosterone suppressed the expression of innate antiviral and proinflammatory mediators to a greater extent in females than males, these immunomodulatory effects did not correlate with SEOV load. Males with low corticosterone concentrations and high viral load had elevated regulatory T cell responses and expression of matrix metalloprotease (Mmp)9. MMP-9 is a glycogenase that disrupts cellular matrices and may facilitate extravasation of SEOV-infected cells from circulation into lung tissue. Suppression of glucocorticoids may, thus, contribute to more efficient dissemination of SEOV in male than female rats.

Keywords: corticosterone, hantavirus, host-pathogen co-evolution, HFRS, IFN-β, TGF-β, TNF-α

Introduction

Hantaviruses are negative sense, single-stranded RNA viruses (Family: Bunyaviridae) with a tripartite genome that encodes the viral nucleocapsid (N), envelope glycoproteins (GN and GC), and an RNA polymerase (L). These zoonotic viruses are still emerging worldwide and are maintained in the environment by persistently infecting their rodent or insectivore (e.g. Sorex spp.) reservoirs (Arai et al., 2008, Klein & Calisher, 2007). Hantaviruses and their specific reservoir hosts represent a highly co-evolved system in which both virus and host survive (Plyusnin & Morzunov, 2001).

Rodent reservoirs sustain a presumably lifelong infection with hantaviruses, but do not display overt signs of disease (Botten et al., 2003, Lee et al., 1981). In contrast to rodents, spillover of hantaviruses to humans can cause hantavirus cardiopulmonary syndrome (HCPS), hemorrhagic fever with renal syndrome (HFRS), or nephropathia endemic (NE). Symptoms of HFRS and HCPS in humans are mediated by excessive proinflammatory and CD8+ T cell responses (Khaiboullina & St Jeor, 2002, Kilpatrick et al., 2004, Mori et al., 1999). Seoul virus (SEOV) is the species-specific hantavirus that infects Norway rats. SEOV persists in the lungs of male rats and during infection, localized antiviral defenses, proinflammatory factors, chemokines, and adhesion molecules generally are reduced in males (Easterbrook & Klein, 2008, Hannah et al., 2008, Klein et al., 2004). Regulatory responses, including forkhead box P3 (FoxP3) and transforming growth factor (TGF)-β, however, are elevated in the lungs of male rats during persistent SEOV infection (Easterbrook & Klein, 2008, Easterbrook et al., 2007). Regulatory T cells contribute to host homeostasis by suppressing proinflammatory and CD8+ T cell responses to protect the host, but also can contribute to viral persistence by suppressing responses necessary for viral clearance (Belkaid, 2007). Regulatory T cells reduce expression of tumor necrosis factor (Tnf)α and contribute to hantavirus persistence in the lungs of male rats, but mechanisms of regulatory T cell induction remain unknown (Easterbrook et al., 2007, Schountz et al., 2007).

In addition to regulatory T cells, glucocorticoids are anti-inflammatory steroid hormones that suppress potentially damaging proinflammatory and cellular responses that contribute to the maintenance of host homeostasis, but concurrently may also suppress responses necessary for resolving an infection (Webster et al., 2002). Exposure to a stressor, including viral infection, can activate the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis, which promotes the release of glucocorticoids from the adrenal cortex (Bailey et al., 2003, Silverman et al., 2005). Glucocorticoids suppress proinflammatory, CD8+ T cell, and Th1-polarized responses indirectly through effects on transcription factors, including NF-κB and AP-1, or directly by binding to glucocorticoid response elements (GRE) on responsive host genes (Kassel & Herrlich, 2007). Removal of glucocorticoids by adrenalectomy can result in more efficient viral clearance, but also can cause mortality mediated by excessive proinflammatory responses to viral infection (Bailey et al., 2003, Ruzek et al., 1999). Corticosteroids have been successfully administered to patients with HFRS or HCPS to alleviate symptoms of disease caused by excessive proinflammatory and cellular responses (Dunst et al., 1998, Seitsonen et al., 2006), but whether suppression of such responses may contribute to a reduced ability to clear the virus has not been examined.

Among humans and rodent reservoirs, more males than females are infected with hantaviruses (Klein & Calisher, 2007). When inoculated with the same dose of SEOV, male rats shed virus longer, via more routes, and have more viral RNA present in target organs, such as the lungs, than females (Hannah et al., 2008, Klein et al., 2000, Klein et al., 2004). During SEOV infection, innate immune responses, including the expression of pattern recognition receptors (PRR; e.g. Toll like receptor [Tlr]7 and retinoic acid inducible gene [Rig]I) and innate antiviral genes (e.g. interferon [Ifn]β and Myxovirus resistance [Mx]2), as well as proinflammatory and chemokine responses, are higher in the lungs of female than male rats (Hannah et al., 2008, Klein et al., 2004). These sex differences may be dependent on estradiol in females and testosterone in males, as gonadectomy reverses these differences (Hannah et al., 2008). Like sex steroids, glucocorticoids can be differentially regulated between the sexes (Kitay, 1961) and also may contribute to differential immune responses in males and females during SEOV infection. We hypothesized that elevated concentrations of glucocorticoids in male rats may suppress host proinflammatory and effector immune responses during SEOV infection to contribute to increased viral persistence in male as compared with female rats.

Materials and Methods

Animals

Adult male and female (50–55 days of age) Long Evans rats (Rattus norvegicus) were purchased from Charles River Laboratories (Raleigh, NC) and housed individually in polypropylene cages covered with polyester filter bonnets. All infected rats were housed in a pathogen-free Biosafety Level (BSL) 3 animal facility with food, water, and 0.9% saline available ad libitum. Uninfected animals were housed under identical conditions as infected animals. Rats were maintained on a constant 14:10 light:dark cycle with lights on at 0600 hours Eastern Standard Time. The Johns Hopkins Animal Care and Use Committee and the Johns Hopkins Office of Health, Safety and Environment approved all procedures described in this manuscript.

Surgical procedure and glucocorticoid replacement

Male and female rats (n=400) were anaesthetized with Ketamine (80 mg/kg) and Xylazine (6 mg/kg) (Phoenix Pharmaceutical, St. Joseph, MO) and were subjected to bilateral adrenalectomy (ADX) or received sham surgery. Exogenous corticosterone was replaced in 250 mg pellets containing 10% or 80% corticosterone (MP Biomedicals, Solon, OH), with the remainder of the pellet consisting of cholesterol (MP Biomedicals). Animals assigned to the sham surgery or ADX0 groups were implanted with pellets containing 100% cholesterol. Pellets were implanted in the intrascapular region and all animals were allowed two weeks to recover from surgery.

Infection

Male and female rats (n = 8–12/sex/corticosterone treatment/time-point) were inoculated i.p. with 104 plaque forming units (pfu) of SEOV (strain SR-11) or vehicle alone, as described previously (Klein et al., 2001, Klein et al., 2002). At Days 0, 3, 15, 30, and 40 post inoculation (p.i.), animals were anesthetized with isoflourane (Abbot Animal Health, North Chicago, IL) and blood was obtained from the retro-orbital sinus. To circumvent the rise in corticosterone concentrations following exposure to common laboratory handling procedures, blood samples were collected within 3 minutes of moving the cage (Place & Kenagy, 2000). Rats were euthanized with CO2 and lung samples were collected and stored at −80°C until processed.

Corticosterone EIA

Corticosterone was extracted from sera using diethyl ether. The ether layer was removed and evaporated and samples were reconstituted in assay buffer (Cayman Chemicals, Ann Arbor, MI). Corticosterone concentrations in serum (final dilution 1:100) were measured using a commercial EIA kit and the manufacturer’s protocol (Cayman Chemicals).

RNA Isolation

RNA was isolated from the lungs using Trizol LS (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) and the manufacturer’s protocol as described previously (Klein et al., 2000, Klein et al., 2001). Following isopropanol precipitation and washing in 75% ethanol, RNA pellets were briefly air dried and resuspended in DEPC-treated water.

Real-time quantitative RT – PCR for SEOV detection

First-strand synthesis of the S segment of SEOV cDNA was prepared as previously described using 0.1 µM gene-specific primers and the Invitrogen Superscript III First Strand Synthesis reagents (Easterbrook & Klein, 2008, Hannah et al., 2008). Negative- and positive-sense SEOV was measured by real-time RT-PCR as described elsewhere (Hannah et al., 2008).

Real-time quantitative RT – PCR for host gene expression

First strand cDNA was prepared and gene expression was measured by real-time RT-PCR, as described previously (Easterbrook & Klein, 2008, Hannah et al., 2008). Custom primer and probe sets were generated using Primer Express 2.0 software (Applied Biosystems) and the NCBI sequences for genes in Rattus norvegicus, with the exception of murine Rorγt. Gene expression patterns from SEOV infected animals were normalized to Gapdh expression and are presented as relative to the expression levels from uninfected rats (i.e. Day 0 p.i.) in the appropriate corticosterone treatment group and are expressed as fold change.

Cytokine protein quantitation by ELISA

Lung tissue was homogenized in lysis buffer, as described previously (Easterbrook & Klein, 2008). Cytokine protein in the supernatant was measured using ELISA kits for rat TNF-α and active mouse TGF-β1 (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN). Protein concentrations are expressed as fold change relative to protein concentrations in uninfected rats (i.e. Day 0 p.i.).

FACS Analyses

Lung tissue was digested in collagenase (1 mg/ml; Invitrogen) and DNase (3 µg/µl; Roche, Indianapolis, IN) to produce a single cell suspension. Following red blood cell lysis, non-specific binding was minimized by incubation with anti-rat CD32 (FcγII receptor). Cells were stained for viability using ethidium monoazide (EMA; Invitrogen) and the appropriate anti-rat monoclonal antibodies (BD Biosciences, San Diego, CA unless otherwise specified) as follows: CD4+ T cells: FITC-CD3 (clone G4.18), PE-CD25 (clone OX-39), and APC-CD4 (clone OX-35); CD8+ T cells: FITC-CD8 (clone OX-8), PE-CD3 (clone G4.18), and APC-CD4; B cells: FITC-CD45R (clone HIS24) and APC-CD4; NK cells: FITC-CD3, PE-CD161a (clone NKR-P1A), and APC-CD5 (clone HIS47; eBiosciences, San Diego, CA); regulatory T cells: FITC CD4 (clone OX-35) and PE-CD25; and macrophages: PE-CD3. Following fixation and permeabilization, regulatory T cells and macrophages were further labeled with APC-FoxP3 (clone FJK-16a; eBiosceinces) and FITC-CD68 (ED-1; Serotec, Raleigh, NC), respectively. Isotype controls for each fluorochrome were run using the same procedure as surface and intracellular labeling and were used to determine gating limits. Cells were identified using CellQuest Pro (BD Biosciences) and data were analyzed using FlowJo software (Treestar, Inc., Ashland, OR).

Statistical Analyses

Quantitative variables were analyzed using ANOVAs or the non-parametric equivalent. Significant interactions were further analyzed using the Tukey or Dunn method for pairwise multiple comparisons. Mean differences were considered statistically significant if P< 0.05. Correlational analyses were performed using the Pearson Product Moment.

Results

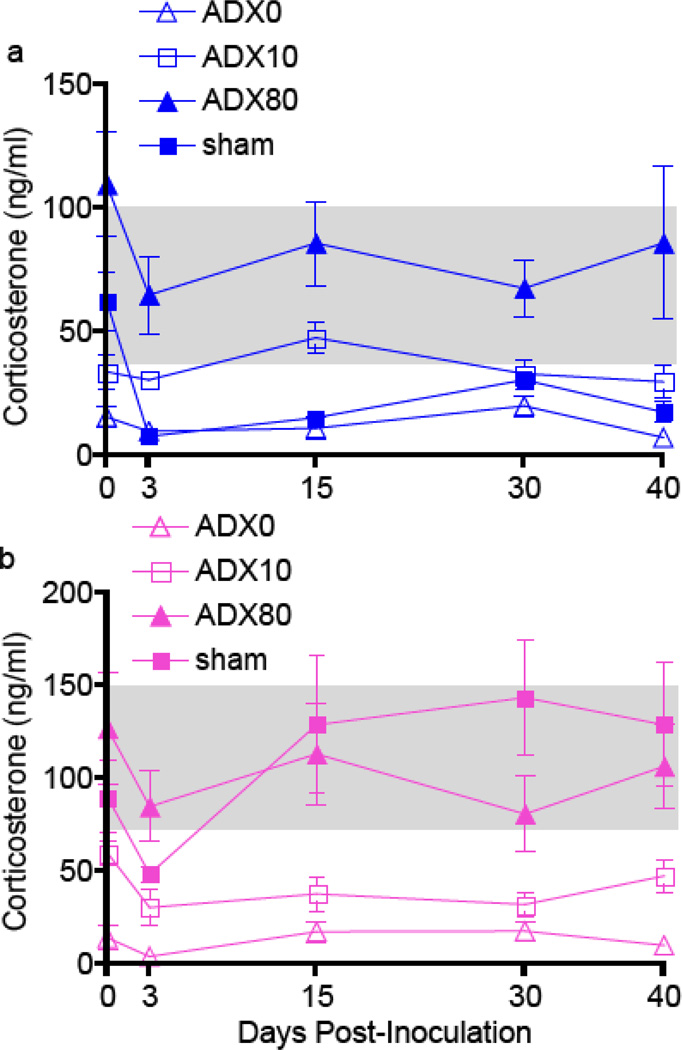

Circulating corticosterone concentrations are reduced in male rats during SEOV infection

The physiological circulating concentration of corticosterone in rodents generally ranges from 45–100 ng/ml for males and 75–150 ng/ml for females and is reduced to 10–25 ng/ml by bilateral adrenalectomy (Bishayi & Ghosh, 2003, Kitay, 1961, You-Ten & Lapp, 1996). Removal of the adrenal glands and subsequent replacement with 0% (ADX0), 10% (ADX10), and 80% (ADX80) corticosterone resulted in low (12.6 ± 1.4 ng/ml), medium (35.1 ± 2.7 ng/ml), and high (93.0 ± 7.3 ng/ml) concentrations of corticosterone in the serum of male and females rats throughout SEOV infection (Figures 1a and b; P<0.001 in each case). In male rats that received sham surgeries and had intact adrenal glands (sham), concentrations of corticosterone were reduced throughout SEOV infection (Figure 1a; P< 0.001) and were similar to concentrations in ADX0 males. In sham females, corticosterone concentrations were not affected by SEOV infection (Figure 1b).

Figure 1. Circulating corticosterone concentrations were reduced in male rats during SEOV infection.

Corticosterone in the serum of male (a) and female (b) rats that were ADX with corticosterone replaced at 0% (ADX0), 10% (ADX10), or 80% (ADX80) and in rats that received sham surgeries (sham) was measured by EIA. The gray boxes represent physiological concentrations of corticosterone in male and female rodents. Sham male rats had reduced concentrations of circulating corticosterone throughout SEOV infection that were comparable to ADX0 males (P<0.05).

Male rats with low circulating corticosterone have the highest amount of SEOV RNA in the lungs during peak infection

SEOV RNA was elevated 15 days p.i. in the lungs of both male and female rats (Figures 2a and b; P<0.001 in each case), but to a greater extent in males than females (P<0.01). At Day 15 p.i., ADX0 and sham males had more SEOV RNA in the lungs than ADX10 or ADX80 males (Figure 2a; P<0.001). Manipulation of corticosterone did not affect the amount of SEOV RNA in the lungs of female rats. Although the amount of SEOV RNA was reduced at Day 40 p.i., it was still detectable in the lungs of male and female rats in all treatment groups, but to a greater extent in sham male (9/10) than sham female (6/10) rats.

Figure 2. Male rats with low circulating corticosterone had the most SEOV RNA in the lungs during peak infection.

Genomic SEOV RNA was measured by real-time RT-PCR in lung tissue of male (a) and female (b) rats that were sham operated or ADX with corticosterone replaced and inoculated with SEOV. Sham and ADX0 males had more SEOV RNA in the lungs at Day 15 p.i. than either ADX10 or ADX80 males or all groups of females (*), P<0.05.

During replication of hantavirus genomic negative-sense RNA, positive-sense mRNA is produced and is indicative of viral replication (Botten et al., 2003, Hannah et al., 2008). Positive-sense SEOV mRNA was detected in the lungs of males and females and paralleled the distribution of negative-sense SEOV RNA copies at Day 15 p.i., but at an approximately 195-fold lower copy number (P<0.001). The copies of negative- and positive-sense SEOV RNA were positively correlated at all time-points during infection (R = 0.65, P<0.001).

Innate, proinflammatory, CD8+, and CD4+ T cell responses do not mediate the glucocorticoid-dependent sex difference in SEOV load

To test a likely hypothesis that immunomodulation by glucocorticoids caused the increased amount of SEOV RNA in the lungs of male rats with low corticosterone, proportions of various immune cell types and genes that are indicative of cellular activity were examined. There was no significant effect of SEOV infection or corticosterone treatment on the percentage of macrophages in the lungs of female or male rats (Supplemental Table 1). Expression of several innate and proinflammatory mediators was elevated (e.g. Tnfα and Ifnβ) or unchanged (i.e. Myd88 and Nos2) in the lungs of sham and ADX females with low corticosterone concentrations during SEOV infection (P<0.05 for both cases); the administration of a high dose of corticosterone suppressed or eliminated the elevated expression of these innate and proinflammatory mediators in females (Figure 3a, c, d, and f and Supplemental Table 2; P<0.05 for each case). The expression of Ifnβ, Tnfα, Myd88, and Nos2 was reduced in the lungs of male rats throughout SEOV infection, regardless of glucocorticoid manipulation (Figure 3a, b, d, and e and Supplemental Table 2; P<0.05 for each case). The expression of Il6 was reduced or remained unchanged in the lungs of both males and females throughout SEOV infection, regardless of corticosterone treatment (Supplemental Table 2; P<0.05).

Figure 3. The expression of Ifnβ and Tnfα was elevated in the lungs of female, but not male, rats during SEOV infection and was reduced by administration of a high dose of corticosterone.

Expression of Ifnβ and Tgfβ in the lungs of sham male and female rats (a and d) and males (b and e) and females (c and f) that had corticosterone manipulated was measured Days 0, 3, 15, 30, and 40 p.i. by real-time RT-PCR. Gene expression is displayed as relative to expression in uninfected rats in the same treatment group (green line) and the expression of each cytokine was normalized to Gapdh. The expression of Ifnβ and Tnfα was higher in the lungs of sham females than sham males during SEOV infection (*), P<0.05. High dose corticosterone (ADX80) eliminated the elevated expression of both Ifnβ and Tnfα in the lungs of female rats during SEOV infection (†), P<0.05.

The proportions of CD4+ T cells and B cells, as well as the expression of the Th1-specific T box transcription factor (Tbet), the Th2 transcription factor, GATA binding protein (Gata)3, Il4, the Th17 transcription factor retinoic acid-related orphan receptor (Rorγt), and Il17, were not altered by SEOV infection or glucocorticoid manipulation in the lungs of male and female rats (Supplemental Tables 1–3). The proportions of CD8+ T cells and expression of Ifnγ and granzyme B (Gzmb) genes were not affected by corticosterone manipulation in males or females; proportions of CD8+ T cells and expression of Ifnγ, however, were elevated in the lungs of sham females compared with sham males during persistent infection (Supplemental Tables 1 and 3; P<0.001 for each case).

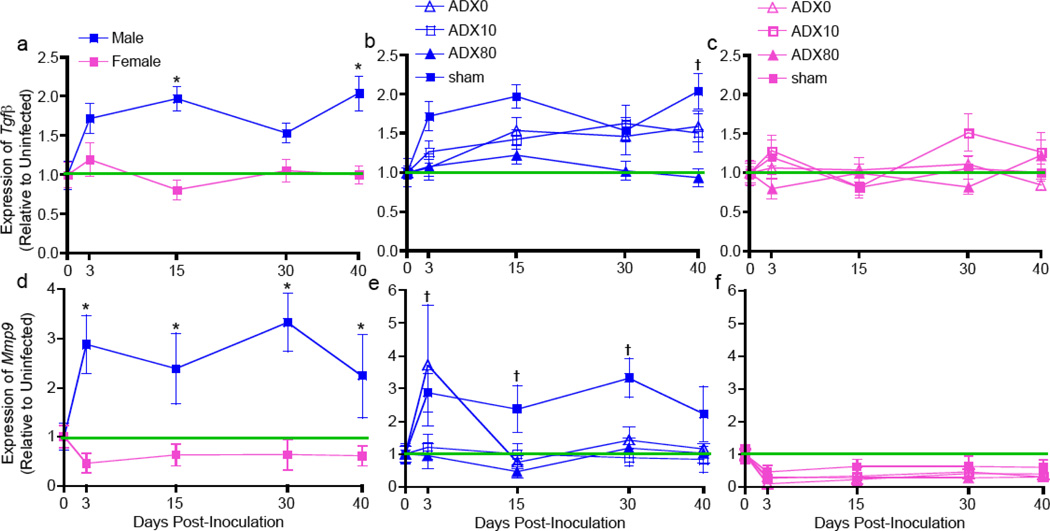

Elevated regulatory T cell activity in the lungs is associated with low circulating corticosterone in male, but not female, rats during SEOV infection

Previous data demonstrate that male rats have elevated proportions of regulatory T cells in the lungs during persistent SEOV infection (Easterbrook et al., 2007). The proportions of regulatory T cells and expression of Tgfβ and Foxp3 in the lungs were elevated in male rats with low corticosterone concentrations, but not in ADX80 males, 30 and 40 days p.i. (Figure 4a and b and Supplemental Tables 1 and 2; P<0.05 in each case). There was no effect of SEOV infection or corticosterone treatment on either the proportion of regulatory T cells or the expression of Tgfβ and Foxp3 in the lungs of female rats (Figure 4a and c and Supplemental Tables 1 and 2). Low concentrations of corticosterone correlated with increased regulatory T cell activity in the lungs of males (Tgfβ: R = −0.27, P<0.001 and Foxp3: R = −0.17, P = 0.04). Similar patterns of TGF-β protein production as Tgfβ gene expression in the lungs were observed for both males and females throughout infection (data not shown).

Figure 4. Elevated regulatory T cell activity and Mmp9 expression was associated with low circulating corticosterone in male, but not female, rats.

The expression of Tgfβ and Mmp9 in the lungs of sham male and female rats (a and d), as well as males (b and e) and females (c and f) that that were ADX with corticosterone replaced was measured Days 0, 3, 15, 30, and 40 p.i. by real-time RT-PCR. Gene expression was normalized to Gapdh and is expressed as relative to expression in uninfected rats in the same corticosterone treatment group (green line). Sham males had higher expression of Tgfβ and Mmp9 in the lungs than sham females during SEOV infection (*), P<0.05. Males with low concentrations of circulating corticosterone had higher expression of Tgfβ and Mmp9 than ADX80 males (†), P<0.05.

The expression of Mmp9 is elevated in the lungs of male rats with reduced glucocorticoid concentrations during acute SEOV infection

Because immune responses were not indicative of why male rats with low circulating corticosterone had higher amounts of SEOV RNA in their lungs during peak infection, we examined the potential role of non-immune mediators. The glycogenase, matrix metalloprotease (MMP)-9 was identified as a factor that is modulated by glucocorticoids, expressed differentially between the sexes, and can increase dissemination of virus-infected macrophages in tissues (Bishayi & Ghosh, 2003, Lafrenie et al., 1996, Nilsson et al., 2007). Expression of Mmp9, was higher in the lungs of sham males than sham females during SEOV infection (Figure 4d; P<0.001). Mmp9 expression was elevated early during infection at Day 3 p.i. in ADX0 and sham male rats as compared with ADX10 and ADX80 males (Figure 4e; P<0.05 for each case). In the lungs of female rats, expression of Mmp9 was reduced during SEOV infection, regardless of glucocorticoid treatment (Figure 4f; P = 0.006). Tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase (TIMP)-1 is a specific inhibitor of Mmp9 expression and the expression of Timp1 in the lungs did not differ among corticosterone treatment groups in either males or females (Supplemental Table 2). TGF-β causes increased expression of Mmp9 and our data consistently revealed a correlation between Tgfβ and Mmp9 expression across all time-points during SEOV infection (R = 0.23, P = 0.009). Thus, the expression of Mmp9 correlated with SEOV load in males with low circulating corticosterone.

Discussion

Glucocorticoids are instrumental for the maintenance of host homeostasis. Viral infection can increase glucocorticoid concentrations during an acute and symptomatic infection to suppress proinflammatory responses that otherwise may be fatal (Bailey et al., 2003, Silverman et al., 2005). Hantaviruses and their reservoir hosts, however, represent a highly co-evolved system in which viral persistence is maintained and the host does not display symptoms of disease. The role of glucocorticoids in maintaining the balance between survival of SEOV and survival of the rat host, a model system of host homeostasis, was examined. Circulating concentrations of corticosterone were reduced during SEOV infection in male, but not female, rats. Peak infection, as defined by the highest amount of SEOV RNA in the lungs, varies across studies, but consistently ranges between 15 and 30 days p.i., after which point, viral load is reduced, but remains detectable presumably for the lifetime of the rat (Easterbrook & Klein, 2008, Easterbrook et al., 2007, Hannah et al., 2008, Klein et al., 2001, Klein et al., 2002). Male rats with the lowest concentrations of corticosterone had the highest amount of SEOV RNA in the lungs during peak infection (i.e. Day 15 p.i.). No relationship between glucocorticoids and SEOV RNA was observed among females; thus, low corticosterone is associated with elevated SEOV replication or dissemination in the lungs of males only. These data suggest that in addition to the known effects of sex steroid hormones (Hannah et al., 2008, Klein et al., 2002), glucocorticoids also contribute to different patterns of SEOV infection in male and female rats.

The lungs consistently are a site of elevated hantavirus replication and persistence (Botten et al., 2003, Easterbrook & Klein, 2008, Hutchinson et al., 1998, Lee et al., 1981). Because glucocorticoids have immunomodulatory properties, immune responses in the lungs were analyzed to evaluate potential mediators of hantaviral persistence and replication at a primary site of infection. Glucocorticoids did not affect proportions of CD3+, non-regulatory CD4+ T cells, CD8+ T cells, B cells, or macrophages in the lungs of male and female rats during SEOV infection. Every nucleated cell expresses glucocorticoid receptors, which when bound by glucocorticoids, translocate to the nucleus to alter transcription (Miller et al., 1998, Silverman et al., 2005). Thus, glucocorticoids were hypothesized to exert regulation of cell function at the transcriptional level rather than on the number or proportion of cells present in the lungs. The expression and production of proinflammatory, antiviral, as well as CD8+ T cell, Th1, Th2, and Th17 transcription factors and cytokines, however, did not correlate with elevated SEOV RNA load in the lungs of male rats with low concentrations of corticosterone,

Localized regulatory T cell responses (i.e. FoxP3 and TGF-β production) are elevated during persistent infection and contribute to hantavirus persistence in male rodents (Easterbrook et al., 2007, Schountz et al., 2007). This study shows that during SEOV infection, proportions of regulatory T cells, as well as the expression and production of Foxp3 and TGF-β, are elevated in the lungs of male, but not female, rats with low circulating concentrations of corticosterone (i.e. sham and ADX0 males). Although glucocorticoids and regulatory T cells both contribute to host homeostasis, glucocorticoids negatively regulate regulatory T cell responses through a negative glucocorticoid response element (GRE) on the TGF-β promoter (Parrelli et al., 1998). In males, reduced concentrations of corticosterone may contribute to subsequently elevated production of TGF-β and regulatory T cell responses.

The immune mediators that were examined did not fully explain the association between reduced circulating corticosterone and elevated SEOV RNA during peak infection in the lungs of male rats. Glucocorticoids also regulate the transcription of non-immune genes, including metabolic factors (e.g. rat arginase and tyrosine aminotransferase), cell proliferation factors (e.g. cyclin D3), and enzymes (e.g. MMP-9) (Bishayi & Ghosh, 2003, Newton, 2000). MMP-9 is a glycogenase that disrupts the basement membrane and extracellular matrix to permit mobility of cells through tissues and can contribute to extravasation of HIV-infected monocytes (Lafrenie et al., 1996). Hantaviruses also infect monocytes and macrophages and could increase dissemination into tissues by upregulating MMP-9 to disturb the protective basement membrane barrier. The expression of Mmp9 is negatively regulated by glucocorticoids (Eberhardt et al., 2002). Male rats with low circulating corticosterone had elevated expression of Mmp9 in their lungs during the acute phase of SEOV infection as compared with males with higher corticosterone concentrations. Among several species, females express less Mmp9 than males, which is mediated by the suppression of Mmp9 expression by estradiol (Ailawadi et al., 2004, Nilsson et al., 2007). In contrast to male rats, females had reduced expression of Mmp9 in the lungs during SEOV infection, suggesting that estradiol may inhibit Mmp9 expression in females, regardless of glucocorticoid concentrations. Additionally, TGF-β induces the expression of Mmp9 in macrophages and endothelial cells (Puyraimond et al., 1999, Xie et al., 1994). Male rats with the highest expression of Tgfβ also had elevated expression of Mmp9, suggesting that production of TGF-β may contribute to regulatory T cell activity and Mmp9 expression in male rats during early SEOV infection. Elevated production of MMP-9 during the acute phase of SEOV infection (e.g. Day 3 p.i.) may contribute to more efficient viral dissemination and, subsequently, more SEOV RNA in the lungs of male than female rats during peak infection (e.g. Day 15 p.i.). The initial dissemination of SEOV-infected cells may contribute to an increased viral load in lung tissue, but once infection is established, extended production of MMP-9 may be unnecessary for maintenance of viral persistence. Immune mediators, including regulatory T cells, are more likely to be the predominant mediators of SEOV persistence in the lungs of rats. Whether SEOV-infected or bystander macrophages and endothelial cells contribute to elevated Mmp9 expression in the lungs of males requires further investigation. Additionally, the temporal dynamics of MMP-9 production at time-points between Days 3 and 15 p.i. and the role of MMP-9 in mediating SEOV dissemination should be further evaluated.

The mechanism by which SEOV infection causes a reduction of corticosterone concentrations in male rats remains unknown. SEOV RNA has been identified in the adrenal glands of male and female rats (Klein et al., 2002; Hinson et al., 2004), so whether SEOV may act directly on cellular production of corticosterone in the adrenal cortex or indirectly through other host immunological or endocrine factors to modulate corticosterone production requires further investigation. The role of immune and endocrine mediators in contributing to the maintenance of zoonotic viruses, including hantaviruses, in the environment should continue to be examined.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank Thomas Castonguay for teaching us how to adrenalectomize rats and prepare corticosterone pellets. We also would like to thank Michele Hannah for assistance with animal processing, Greg Glass and Fidel Zavala for discussions about these data, Connie Schmaljohn and Kristen Spik (U.S. Army Medical Research Institute of Infectious Diseases) for providing hantavirus reagents, and the Becton Dickinson Immune Function Laboratory for use of the FACS equipment and analysis of FACS data. Financial support was provided by NIH R01 AI 054995 (SLK).

References

- Ailawadi G, Eliason JL, Roelofs KJ, Sinha I, Hannawa KK, Kaldjian EP, Lu G, Henke PK, Stanley JC, Weiss SJ, Thompson RW, Upchurch GR., Jr Gender differences in experimental aortic aneurysm formation. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2004;24:2116–2122. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000143386.26399.84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arai S, Bennett SN, Sumibcay L, Cook JA, Song JW, Hope A, Parmenter C, Nerurkar VR, Yates TL, Yanagihara R. Phylogenetically distinct hantaviruses in the masked shrew (Sorex cinereus) and dusky shrew (Sorex monticolus) in the United States. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2008;78:348–351. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey M, Engler H, Hunzeker J, Sheridan JF. The hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis and viral infection. Viral Immunol. 2003;16:141–157. doi: 10.1089/088282403322017884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belkaid Y. Regulatory T cells and infection: a dangerous necessity. Nat Rev Immunol. 2007;7:875–888. doi: 10.1038/nri2189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bishayi B, Ghosh S. Metabolic and immunological responses associated with in vivo glucocorticoid depletion by adrenalectomy in mature Swiss albino rats. Life Sci. 2003;73:3159–3174. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2003.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Botten J, Mirowsky K, Kusewitt D, Ye CY, Gottlieb K, Prescott J, Hjelle B. Persistent Sin Nombre virus infection in the deer mouse (Peromyscus maniculatus) model: Sites of replication and strand-specific expression. J Virol. 2003;77:1540–1550. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.2.1540-1550.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunst R, Mettang T, Kuhlmann U. Severe thrombocytopenia and response to corticosteroids in a case of nephropathia epidemica. Am J Kidney Dis. 1998;31:116–120. doi: 10.1053/ajkd.1998.v31.pm9428461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Easterbrook JD, Klein SL. Seoul virus enhances regulatory and reduces proinflammatory responses in male Norway rats. J Med Virol. 2008;80:1308–1318. doi: 10.1002/jmv.21213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Easterbrook JD, Zink MC, Klein SL. Regulatory T cells enhance persistence of the zoonotic pathogen Seoul virus in its reservoir host. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2007;104:15502–15507. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0707453104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eberhardt W, Schulze M, Engels C, Klasmeier E, Pfeilschifter J. Glucocorticoid-mediated suppression of cytokine-induced matrix metalloproteinase-9 expression in rat mesangial cells: involvement of nuclear factor-kappaB and Ets transcription factors. Mol Endocrinol. 2002;16:1752–1766. doi: 10.1210/me.2001-0278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hannah MF, Bajic VB, Klein SL. Sex differences in the recognition of and innate antiviral responses to Seoul virus in Norway rats. Brain Behav Immunity. 2008;22:503–516. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2007.10.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinson ER, Shone SM, Zink MC, Glass GE, Klein SL. Wounding: the primary mode of Seoul virus transmission among male Norway rats. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2004;70:310–317. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutchinson KL, Rollin PE, Peters CJ. Pathogenesis of a North American hantavirus, Black Creek Canal virus, in experimentally infected Sigmodon hispidus. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1998;59:58–65. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1998.59.58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kassel O, Herrlich P. Crosstalk between the glucocorticoid receptor and other transcription factors: molecular aspects. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2007;275:13–29. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2007.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khaiboullina SF, St Jeor SC. Hantavirus immunology. Viral Immunol. 2002;15:609–625. doi: 10.1089/088282402320914548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilpatrick ED, Terajima M, Koster FT, Catalina MD, Cruz J, Ennis FA. Role of specific CD8+ T cells in the severity of a fulminant zoonotic viral hemorrhagic fever, hantavirus pulmonary syndrome. J Immunol. 2004;172:3297–3304. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.5.3297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitay JI. Sex differences in adrenal cortical secretion in the rat. Endocrinology. 1961;68:818–824. doi: 10.1210/endo-68-5-818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein SL, Bird BH, Glass GE. Sex differences in Seoul virus infection are not related to adult sex steroid concentrations in Norway rats. J Virol. 2000;74:8213–8217. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.17.8213-8217.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein SL, Bird BH, Glass GE. Sex differences in immune responses and viral shedding following Seoul virus infection in Norway rats. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2001;65:57–63. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2001.65.57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein SL, Calisher CH. Emergence and persistence of hantaviruses. Cur Top Microbiol Immunol. 2007;317:217–252. doi: 10.1007/978-3-540-70962-6_10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein SL, Cernetich A, Hilmer S, Hoffman EP, Scott AL, Glass GE. Differential expression of immunoregulatory genes in male and female Norway rats following infection with Seoul virus. J Med Virol. 2004;74:180–190. doi: 10.1002/jmv.20163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein SL, Marson AL, Scott AL, Ketner G, Glass GE. Neonatal sex steroids affect responses to Seoul virus infection in male but not female Norway rats. Brain Behav Immunity. 2002;16:736–746. doi: 10.1016/s0889-1591(02)00026-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lafrenie RM, Wahl LM, Epstein JS, Hewlett IK, Yamada KM, Dhawan S. HIV-1-Tat modulates the function of monocytes and alters their interactions with microvessel endothelial cells. A mechanism of HIV pathogenesis. J Immunol. 1996;156:1638–1645. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee HW, Lee PW, Baek LJ, Song CK, Seong IW. Intraspecific transmission of Hantaan virus, etiologic agent of Korean Hemorrhagic fever, in the rodent. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1981;30:1106–1112. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1981.30.1106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller AH, Spencer RL, Pearce BD, Pisell TL, Azrieli Y, Tanapat P, Moday H, Rhee R, McEwen BS. Glucocorticoid receptors are differentially expressed in the cells and tissues of the immune system. Cell Immunol. 1998;186:45–54. doi: 10.1006/cimm.1998.1293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mori M, Rothman AL, Kurane I, Montoya JM, Nolte KB, Norman JE, Waite DC, Koster FT, Ennis FA. High levels of cytokine-producing cells in the lung tissues of patients with fatal hantavirus pulmonary syndrome. J Infect Dis. 1999;179:295–302. doi: 10.1086/314597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newton R. Molecular mechanisms of glucocorticoid action: what is important? Thorax. 2000;55:603–613. doi: 10.1136/thorax.55.7.603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nilsson UW, Garvin S, Dabrosin C. MMP-2 and MMP-9 activity is regulated by estradiol and tamoxifen in cultured human breast cancer cells. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2007;102:253–261. doi: 10.1007/s10549-006-9335-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parrelli JM, Meisler N, Cutroneo KR. Identification of a glucocorticoid response element in the human transforming growth factor beta 1 gene promoter. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 1998;30:623–627. doi: 10.1016/s1357-2725(98)00005-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Place NJ, Kenagy GJ. Seasonal changes in plasma testosterone and glucocorticosteroids in free-living male yellow-pine chipmunks and the response to capture and handling. Journal of Comparative Physiology B-Biochemical Systemic and Environmental Physiology. 2000;170:245–251. doi: 10.1007/s003600050282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plyusnin A, Morzunov SP. Virus evolution and genetic diversity of hantaviruses and their rodent hosts. Hantaviruses. 2001:47–75. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-56753-7_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puyraimond A, Weitzman JB, Babiole E, Menashi S. Examining the relationship between the gelatinolytic balance and the invasive capacity of endothelial cells. J Cell Sci. 1999;112(Pt 9):1283–1290. doi: 10.1242/jcs.112.9.1283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruzek MC, Pearce BD, Miller AH, Biron CA. Endogenous glucocorticoids protect against cytokine-mediated lethality during viral infection. J Immunol. 1999;162:3527–3533. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schountz T, Prescott J, Cogswell AC, Oko L, Mirowsky-Garcia K, Galvez AP, Hjelle B. Regulatory T cell-like responses in deer mice persistently infected with Sin Nombre virus. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2007;104:15496–15501. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0707454104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seitsonen E, Hynninen M, Kolho E, Kallio-Kokko H, Pettila V. Corticosteroids combined with continuous veno-venous hemodiafiltration for treatment of hantavirus pulmonary syndrome caused by Puumala virus infection. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2006;25:261–266. doi: 10.1007/s10096-006-0117-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silverman MN, Pearce BD, Biron CA, Miller AH. Immune modulation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis during viral infection. Viral Immunol. 2005;18:41–78. doi: 10.1089/vim.2005.18.41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webster JI, Tonelli L, Sternberg EM. Neuroendocrine regulation of immunity. Ann Rev Immunol. 2002;20:125–163. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.20.082401.104914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie B, Dong Z, Fidler IJ. Regulatory mechanisms for the expression of type IV collagenases/gelatinases in murine macrophages. J Immunol. 1994;152:3637–3644. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- You-Ten KE, Lapp WS. The role of endogenous glucocorticoids on host T cell populations in the peripheral lymphoid organs of mice with graft-versus-host disease. Transplantation. 1996;61:76–83. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199601150-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.