Abstract

In coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG), the combined use of left and right internal mammary arteries (LIMA and RIMA) — collectively known as bilateral IMAs (BIMAs) provides a survival advantage over the use of LIMA alone. However, gene expression in RIMA has never been compared to that in LIMA. Here we report a genome-wide transcriptional analysis of BIMA to investigate the expression profiles of these conduits in patients undergoing CABG. As expected, in comparing the BIMAs to the aorta, we found differences in pathways and processes associated with atherosclerosis, inflammation, and cell signaling — pathways which provide biological support for the observation that BIMA grafts deliver long-term benefits to the patients and protect against continued atherosclerosis. These data support the widespread use of BIMAs as the preferred conduits in CABG.

Keywords: Cardiovascular disease, Transcriptome analysis, Genomics, Coronary artery bypass grafting

1. Introduction

Surgical treatment of coronary artery disease (CAD) has advanced significantly in the past four decades, producing substantial improvements in patient outcomes. These past two decades have seen the evolution of the approach to the procedure from on-pump to off-pump to hybrid techniques. However, there are other areas, such as the selection of the ideal graft material for patients with CAD undergoing coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG), where adoption of new practices have lagged. The use of the left internal mammary artery (LIMA) in CABG is now widely accepted as a superior conduit over saphenous vein (SV), radial artery (RA), and gastroepiploic artery (GEA) grafts and has become the standard of care for patients undergoing CABG. LIMA has exceptional 10 year graft patency at (98%) compared to the SV, RA, and GEA grafts (89%, 91%, and 87% respectively) [1,2]. The use of the right IMA (RIMA) as a second graft conduit was a natural evolution after the success demonstrated by the single LIMA. Studies have demonstrated RIMA grafts having similar patency rates to LIMA [2,3].

We recently reported an analysis of short- and long-term outcomes for 1856 propensity-matched CABG patients who received either BIMA-SVG or LIMA-SVG. BIMA grafts demonstrated a survival advantage as early as 5 years post-surgery, leading up to an 18% survival benefit at 15 years follow-up [4]. Our results suggested that perioperative complications do not increase with the use of BIMAs. These results have been supported by subsequent papers [5,6]. The low morbidity and mortality rates in our series are likely due to the continuous evolution of technology and the adoption of less invasive options for CABG patients. A more widespread use of BIMAs in CABG patients would therefore continue to improve the overall excellent short- and long-term results of this operation. Despite these important clinical considerations, the mechanistic explanations for superior BIMA performance over other conduits have not been established and this may contribute to the slow uptake of BIMA grafts by the surgical community.

BIMAs display a significantly lower rate of atherosclerosis and, when used as grafts, seem to pass this protection to the native vessels; the rate of coronary disease progression after receiving an SVG is more than double that of LIMA grafts (48% versus 22%) [7,8]. This suggests that important factors contributing to the success of BIMA grafts may be the result of molecular differences among the tissues that are likely reflected in differences in gene expression. A number of published studies have analyzed gene expression in LIMAs and other conduits and found differences in genes associated with processes such as inflammation, thrombosis, and atherosclerosis (Table 1) [9–24]. However these studies are limited in that they either used a candidate gene approach or analyzed a very small number of samples with gene expression arrays; in none of these has the RIMA been analyzed and compared to the LIMA. Here we report a genome-wide transcriptional analysis of human left and right internal mammary arteries to investigate the expression profile of these conduits in patients undergoing CABG.

Table 1.

Summary of recent published results for the use of LIMA and other conduits used in CABG.

| Pathway | Reference | Protein (gene) | Comparing | Results | Impact |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vasodilation | Antoniades et al. [9] | GTP-cydohydrolase I(GCH1) | LIMA and RA | LIMA has higher levels of GCH1. | GCH1 regulates tetrahydrobiopterin (BH4). resulting in increased eNOS coupling. NO levels, and endothelial health in LIMA. |

| Dungan et al. [10] | B2-Adrenergic receptor (ARB2) | Hypertensive and healthy LIMA | Hypertensive LIMAs have lower levels of ARB2. | ARB2 regulates VSMC dilation in the neurohumoral and sympathetic autonomic nervous system pathways, acting as a receptor for epinephrine and norepinephrine. | |

| He [27] | Endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) (NOS3) | LIMA and RA | LIMA has higher levels of eNOS. | LIMA has higher levels of NO, a potent vasodilator. | |

| Vasoconstriction | Rudner et al. [12] | A1-Adrenergic receptor (ADRA1A) | Young and Old LIMA | ADRA1A levels increases in IMA with age. | IMAS sensitivity to vasoconstrictors increases with age. |

| Oxidative stress | Mangoush et al. [13] | Superoxide dismutase (RhoA) | IMA and RA | IMA has increased SOD activity. | LIMA is better equipped to handle oxidative stress and reperfusion injury. |

| Cell proliferation & migration | Yang et al. [14] | Platelet-derived growth factor-BB (PDGF-BB) (PDFS) | LIMA and SV | SV was more sensitive to PDGF-BB. | PDGF-BB leads to increased MAP kinase and decreased cell cycle inhibitor p27Kip1, ultimately resulting in increased cell proliferation in SV compared to LIMA |

| Mompéo et al. [15] | Estrogen receptors ER-A And ER-B (E SRI/2) | LIMA, SV, and RA | IMAs demonstrated higher levels of ERs. | ERs inhibit vascular smooth muscular cell (VSMC) proliferation and prevents atherosclerosis. | |

| Marchand et al. [16] | Wingless-type MMTV integration site family (Wnt) (Wnt1) | Young and Old LIMA | As IMAs age, Wnt-dependent activation of β-catenin loses the ability to activate cyclin D1. | IMA cell cycle slows down with age. | |

| Blood coagulation | Payeli et al. [17] | Tissue factor (tf), tissue plasminogen activator (Tpa). Tissue factor pathway inhibitor (TFPI) (TF, PLAT, TFPI) | LIMA and SV | IMAs have lower TF levels and higher tPA and TFPI levels. | Longer dotting times and slower VSMC migration times in the LIMA |

| Inflammatory response | Sato et al. [18] | Glucorticoid receptor (GCCR) | Healthy and atherosclerotic LIMA | Glucorticoid receptors are down-regulated by Lp(a) when exposed to pro-atherosclerotic conditions. | Leads to reduced patient response to glucorticoid-based therapies |

| Burger-Kentischer et al. [19] | Macrophage migration inhibitory factor (MIF) | LIMA, aorta, and coronary arteries | Up-regulated in response to LIMAs exposed to oxLDL | MIF is a marker for inflammation. | |

| Arishiro et al. [20] | Gap junction protein, A1 aka connexin 43 (Cx43) (GJA1) | LIMA and RA | Cx43 correlates with nuclear factor kappa beta (NF-κβ) in RA SMCs, but not in LIMA SMCs. | Decreased inflammatory response in LIMA SMCs | |

| Apoptosis | Martinet et al. [21] | Apoptosis-linked gene 2 (ALG-2) | Healthy and atherosclerotic | ALG-2 is down-regulated in non-atherosclerotic IMAs. | Non-atherosclerotic IMAs have reduced levels of apoptosis. |

| Atherosclerosis | Li et al [24] | oxLDL receptor-1 (LOX-1) (OLR1) | LIMA SV, carotid arties, and LIMA | Increased in SV, carotid arteries, and even more in atherosclerotic plaques | LIMA has less oxLDL receptors, implying a protection from atherosclerosis. |

| Besnard et al. [26] | Retinoic acid receptor-related orphan receptor A (RORA) | LIMA and atherosclerotic plaques | RORa4 increases in response to cytokines in healthy IMAs, but is decreased in atherosclerotic plaques. | RORa4, unlike other inflammatory markers, is decreased in atherosclerosis. |

2. Methods

2.1. Patient selection

We selected a cohort of 32 patients from whom we had frozen archival tissue from aorta, LIMA, and RIMA in the Cardiovascular Blood and Tissue Bank at The Valley Hospital. All subjects enrolled in this program gave informed consent prior to the procedure under 1RB approval (#11.0009).

2.2. Tissue harvesting

The mammary and aortic tissues were harvested at the time of CABG. The surgeon dissected the two most distal aspects of LIMA and RIMA segments and obtained a ≥ 1 cm sample. The tissue sample was placed in a cryomold and processed as a “frozen section” specimen using standard OCT gel. The sample was then labeled accordingly and stored in a designated section of a restricted-access freezer kept at − 70 to − 80 °C. During surgery, a punch aortotomy was made for the construction of the proximal anastomosis on the ascending aorta, the aortic tissue retrieved by the punch (the “aortic button”) was stored using an identical protocol. The samples were selected from the tissue bank, put on dry ice, packaged in a secure container, and shipped to the Dana–Farber Cancer Institute for analysis.

2.3. RNA extraction

Tissues were thawed and microdissected to remove muscle and other tissue contaminants and stored in RNAlater in microcentrifuge tubes. Samples were homogenized using a Fisher Rotor–Stator and total RNA was extracted using Qiagen RNeasy Mini Kit. RNA integrity was assessed using the Agilent 2100 BioAnalyzer and RNA quantities and purity were determined using a NanoDrop Spectrophotometer. RNA samples were amplified using the NuGen Ovation RNA Amplification System V2.

2.4. Hybridization and gene expression analysis

cDNA was labeled and hybridized to the Affymetrix U133A 2.0 GeneChip which contains 22,277 probe sets representing 18,400 transcripts and variants of 14,500 human genes and scanned to determine and assess gene expression profiles. The results were stored as Affymetrix.CEL files for further analysis. Of the 96 tissue samples with which we began, RNA from 23 failed quality control either due to insufficient quantities of RNA or due to poor quality hybridization results. Among the 73 profiles that passed quality control, 14 patients had data from all three tissues (“trios”), seven had useful data from aorta and RIMA, four from aorta and LIMA, two had samples from RIMA and LIMA, and five had useful data only from the aortic tissue. Data are available from GEO with Accession GSE41036. Raw gene expression data were normalized using gcRMA [25] which accounts for GC content in gene sequence while adjusting the relative gene expression levels to allow comparison of between samples.

To test for differential expression between groups of patient samples, we constructed linear models using limma, which uses empirical Bayes methods to borrow information across genes, making the analysis stable even for small numbers of samples [26]. To place the differentially expressed genes identified in these analyses into a biological context, we used the ingenuity pathway assist (IPA). IPA uses Fisher's exact test and permutation analysis to search for over-representation of biological pathways and annotated gene functional classes cataloged in the ingenuity pathways knowledge base (IPKB). Finally, we used IPA to generate “enriched local networks” based on the connectivity of the significant gene sets to other genes annotated in the IPKB.

3. Results

3.1. Patient selection

We selected a cohort of 32 patients from whom we had frozen archival tissue from aorta, LIMA, and RIMA. The patients all underwent isolated CABG between January 2008 and February 2011 (Table 2). The mean age was 57.8 years old and mean body mass index was 28.3. The cohort favored Caucasians (81.3%) and males (87.5%). Half of the patients had a history of smoking, however only 22% of the patients currently smoke. Half of the patients had a family history of CAD. Dyslipidemia and hypertension were the two most common co-morbidities (93.8% and 75% of patients, respectively). There were three patients (9.4%) with peripheral artery disease and five with diabetes (15.6%). Eight patients (25%) had previously received a percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) and twelve patients (37.5%) had a previous myocardial infarction. Angina was the most common cardiac symptom upon admission; half the patients had stable angina and ten (31.3%) presented with unstable angina. There was one patient admitted with atrial fibrillation. The mean ejection fraction was 57.1%. The patients underwent CABG, with the average patient requiring 3 grafts. About a third had left main disease. As of January 2012, all 32 patients were alive. The most common medications were beta blockers (90.6%), lipid-lowering drugs (81.3%), and statins (78.1%). Other medications included were aspirin (59.4%), anti-coagulants (37.5%), nitrates (12.5%), ADP inhibitors (6.3%), antiplatelets (6.3%), and glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors (3.1%).

Table 2.

Demographics and patients characteristics.

| Patient characteristics (n = 32) | |

|---|---|

| Age (mean ± SD) | 57.8 ± 7.7 |

| Gender (male, %) | 28, 87.5% |

| Ethnicity (Caucasian, %) | 26, 81.3% |

| Body surface area (mean ± SD) | 2 ±0.2 |

| Body mass index (mean ± SD) | 28.2 ± 3 |

| History of smoking (yes, %) | 16, 50% |

| Currently smoking | 7, 21.9% |

| Family history of CAD (yes, %) | 16, 50% |

| Blood work (mean ± SD) | |

| Cholesterol | 194.1 ± 59.5 |

| Triglycerides | 158.2 ± 127 |

| HDL | 47.5 ± 21.6 |

| DLDL | 124.7 ± 54.1 |

| Chol/HDL | 4.6 ±2 |

| DLDL/HDL | 2.8 ± 1.3 |

| Creatine | 1.0 ± 0.2 |

| Hemoglobin Alc | 6 ± 0.74 |

| Present comorbidity (yes, %) | |

| Hypertension | 24, 75% |

| Peripheral artery disease | 3, 9.4% |

| Diabetes | 5, 15.6% |

| Dyslipidemia | 30, 93.8% |

| Previous PCI (yes, %) | 8, 25% |

| Previous myocardial infarction (yes, %) | 12, 37.5% |

| Angina (yes, %) | |

| Stable | 16, 50% |

| Unstable | 10, 31.3% |

| Arrhythmia (yes, %) | 1, 3.1% |

| Medications (yes, %) | |

| Statins | 25, 78.1% |

| Beta blockers | 29, 90.6% |

| ACE inhibitors | 9, 28.1% |

| Nitrates IV | 4, 12.5% |

| Anti-coagulants | 12, 37.5% |

| Aspirin | 19, 59.4% |

| Lipic-lowering | 26, 81.3% |

| ADP inhibitors | 2, 6.3% |

| Antiplatelets | 2, 6.3% |

| Glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors | 1, 3.1% |

3.2. Comparative genome-wide transcriptional analysis of left and right internal mammary artery

The mammary tissues were harvested at time of coronary artery bypass graft surgery (CABG) and microdissected to remove muscle and other tissue contaminants. cDNA was labeled and hybridized to the Affymetrix U133A 2.0 GeneChip which contains 22,277 probe sets representing 18,400 transcripts and variants of 14,500 human genes and scanned to determine and assess gene expression profiles.

We first tested for significant differences in gene expression between the LIMA and RIMA in the entire set of 43 IMA tissue samples (20 LIMA/23 RIMA) and separately in the 14 trios. Using an adjusted p-value threshold less than 0.05, we found 249 genes that were marginally differentially expressed in the complete sample set, 312 in the collection of paired samples; the overlap between these two sets was 126 genes. We used IPA to assess whether the gene sets included any over-represented functional classes and found no consistent set of over-represented pathways and no trends in patterns of gene expression.

Of the 64 RIMA and LIMA tissue samples with which we began, 43 IMA tissue samples (20 LIMA/23 RIMA) provided good quality data. Of these, 28 represented paired LIMA/RIMA samples from the 14 trios (patients for whom we had LIMA, RIMA, and aorta samples). We then constructed a Bayesian linear model using limma [26] to compare patterns of gene expression between the RIMA and LIMA in the entire set of 43 IMA tissue samples (20 LIMA/23 RIMA) and separately in the 14 trios (patients for whom we had LIMA, RIMA, and aorta samples). Using an adjusted p-value threshold less than 0.05, we found 249 genes that were differentially expressed in the complete sample set, 312 in the collection of paired samples; the overlap between these two sets was 126 genes.

One might expect differences in expression between the LIMA and RIMA that could reflect their developmental history. Commonly used arterial grafts belong to different groups of arteries in various locations of the body and can be divided into somatic arteries and splanchnic arteries [27,28]. Somatic arteries supply the body wall and include the IMA, the inferior epigastric artery (IEA), the subscapular artery and the intercostal artery, while splanchnic arteries supply visceral organs and include the gastroepiploic artery (GEA) and the splenic artery. Embryonic studies have shown that somatic arteries develop from intersegmental branches to the body wall whereas splanchnic arteries develop from segmental branches of primitive dorsal aorta to supply the digestive tube [27, 28].

A few genes associated with the regulation of vascular smooth muscle cell (VSMC) phenotypes suggest slight differences in the developmental history of the LIMA and RIMA. The balance between synthetic and contractile vascular smooth muscle cell (VSMC) phenotype is of critical importance in the vascular tissue homeostasis as well as in the response to atherosclerotic stimuli and could reflect differences associated with development [29]. Among the genes differentially expressed between LIMA and RIMA is CAMK4, a calcium/calmodulin-dependent kinase that is involved in the regulation of cardiac responses, both in terms of electrophysiology and of cardiac myocyte hypertrophy [30, 31]. CAMK 4 is also associated with the bone morphogenetic protein family and so could participate in controlling vascular homeostasis. The genes, ARHGAP26, RHOD, and DIRAS3, related to integrin signaling molecules could also be integrated into the mechanisms of regulation of VSCM phenotype. Finally, PMF1, FOSL1, and CLPP are associated with oxidative stress response and we recently published work describing the role of oxidative stress in controlling cellular phenotype [32,33].

We then used the ingenuity pathway assist (IPA), which performs a Fisher's exact test and permutation analysis, to search for the over-representation of biological pathways and annotated gene functional classes (cataloged in the ingenuity pathways knowledge base) among the genes found to be significant. Among the 249 genes that were found to be differentially expressed in the complete sample set, only five pathways were found to be moderately significant (Fig. 1 and Supplementary Table 1). These five pathways were: cell cycle regulation by BTG family proteins, biosynthesis of steroids, mTOR signaling, mitotic roles of polo-like kinase, and cell cycle control of chromosomal replication. However, none of these represents an obviously relevant class of pathways. For the 312 genes identified in our analysis of the paired samples, we found nearly 20 pathways to be over-represented (Fig. 2 and Supplementary Table 1). These pathways were: CTLA4 signaling in cytotoxic T lymphocytes, iCOS-iCOSL signaling in T helper cells, reelin signaling in neurons, pyrimidine metabolism, ceramide signaling, sphingosine-1-phosphate signaling, CD28 signaling in T helper cells, systemic lupus erythematosus signaling, purine metabolism, T cell receptor signaling, human embryonic stem cell pluripotency, angiopoietin signaling, docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) signaling, natural killer cell signaling, ILK signaling, role of pattern recognition receptors in recognition of bacteria and viruses, NF-κB activation by viruses, nitric oxide signaling in the cardiovascular system, fatty acid elongation in mitochondria, and, role of OCT4 in mammalian embryonic stem cell pluripotency.

Fig. 1.

Statistical significance of canonical pathways with genes differentially expressed between the LIMA and RIMA based on the entire dataset of 43 IMA tissue samples (20 LIMA/23 RIMA). The yellow line represents the significance threshold based on permutation analysis.

Fig. 2.

Statistical significance of canonical pathways with genes differentially expressed between the LIMA and RIMA based on the 28 paired samples derived from 14 patients using data derived from both IMA tissues.

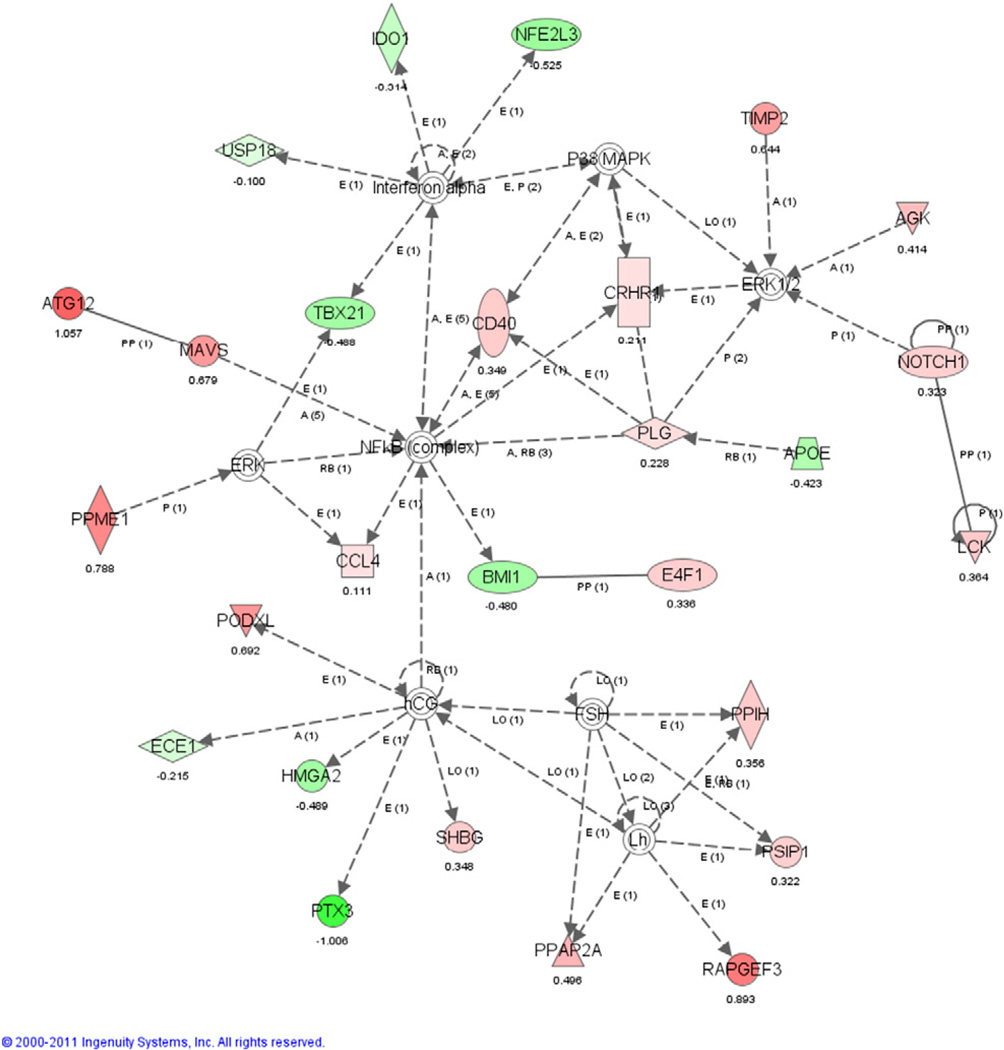

While some of the pathways we identified suggest a role for immune processes and others may be related to the different developmental history of the LIMA and RIMA, we do not find consistent patterns of up- or down-regulation as we found when comparing aorta to IMA as described below; this can be seen by looking at the NF-κB pathway (Fig. 3). Overall, gene expression analysis finds few meaningful differences between the LIMA and RIMA and suggests that these tissues are more alike than different.

Fig. 3.

Inferred connectivity map centered on NF-κB for differentially expressed genes between LIMA and RIMA. Red indicates that the genes are up-regulated in LIMA relative to RIMA and green indicates they were down-regulated. Uncolored genes or complexes were not found to be differentially expressed in our original analysis but were found through the pathway analysis. Note that this network does not exhibit a coherent pattern of biologically-driven regulation but instead a more random distribution of genes and across the network.

3.3. Comparative genome-wide transcriptional analysis of BIMAs and aortic wall

We used a limma to compare the three tissue types to each other using aorta as a baseline. We performed two comparisons. The first used all 73 available gene expression profiles and the second used only those data from the 14 trios. Using an adjusted p-value threshold less than 0.05, we identified 788 genes that were differentially expressed in the complete sample set, 653 in the set of 14 trios with an overlap of 360 between the sets (Table 3). A list of the genes found to be significantly differentially expressed between aorta and BIMA, together with summary statistics, can be found in the Supplementary materials.

Table 3.

Representation of biological pathways and annotated gene functional classes.

| 3D aorta vs. 43 EIMA |

14 trios (BIMA vs. aorta) |

Overlapping set of differentially expressed genes |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| # of up-regulated genes | 297 | 231 | 112 |

| # of down-regulated genes | 435 | 422 | 240 |

| Total | 752 | 053 | 360 |

We used the IPA to search for over-represented metabolic and signaling pathways among the significant gene sets found in analyzing all samples, the 14 trios, and the overlapping gene set. We found 189 pathways to be significantly over-represented in one or more of the gene sets based on permutation testing (see Supplementary materials for a comprehensive list). Pathways were ranked based on their significance among genes in the overlapping set, of these, nineteen were significant, although seven were only marginally significant. We therefore chose to focus on the top 12: atherosclerosis signaling, eicosanoid signaling, complement system, MIF-mediated glucocorticoid regulation, hepatic fibrosis/hepatic stellate cell activation, MIF regulation of innate immunity, arachidonic acid metabolism, LXR/RXR activation, B cell development, PPAR signaling, HMGB1 signaling, and glycerophospholipid metabolism (Fig. 4A). A similar analysis searching for biological functional classes (similar to gene ontology terms) yielded similar results (Supplementary materials and Fig. 4B).

Fig. 4.

Statistical significance of (A) canonical pathways and (B) assigned biological functions associated with genes differentially expressed between aorta and IMA samples as determined using Ingenuity Pathway Assist. The height of bars reflects the p-value from Fisher’s exact test. Blue bars are associated with the 782 differentially expressed genes in all aorta vs. all IMA comparisons. Orange bars present results for the 653 differentially expressed genes from 14 trios. Cyan bars represent results for the 360 genes found to be differentially expressed in both sets. The annotated classes were sorted by the p-value of the overlapping gene set (cyan). Here the significance threshold, shown as a dashed line, was estimated by permutation testing. The canonical pathway “atherosclerosis signaling” was ranked as the most significant pathway. The vast majority of the biological processes found to be significant are associated with inflammation, including those associated with the term “cardiovascular disease.” Detailed information on these significant canonical pathways and functional classes and a list of their component genes is provided in the Supplementary materials.

To better understand the overriding biological processes represented among the significant pathways and gene functional classes we found, we used IPA to generate “enriched local networks” (Fig. 5). These networks start with the annotated networks in the IPKB and extend them based on other sources of data, including protein–protein interaction data and other information linking the input significant genes to other genes annotated in the IPKB. Networks associated with “inflammatory response” as well as with “cellular movement” and “lipid metabolism” highlight a central role for NF-κB. NF-κB is also an important regulator in cell fate decisions, such as programmed cell death and proliferation control, and is critical in a wide range of disease processes [34]. NF-κB stimulates transcription of Cyclin-D1, a key regulator of G1 checkpoint control. Inappropriate activation of NF-κB has been linked to inflammatory events associated with a variety of diseases, including atherosclerosis [35], where it has been shown to be present in the coronary vasculature in hypercholesterolemia [36].

Fig. 5.

Inferred connectivity maps for differentially expressed genes in (A) the “inflammatory response” network and (B.) networks associated with “lipid metabolism” and “cellular movement” Red indicates that the genes are up-regulated in IMA relative to aorta and green indicates they were down-regulated. Uncolored genes or complexes were not found to be differentially expressed in our original analysis but were found through the pathway analysis.

In contrast to the strong similarity among IMAs, the differences between aorta and IMA show a consistent and coherent pattern of expression that is strongly correlated with the known biology and clinical information between these tissues.

4. Conclusions

What emerges from these collective analyses is a coherent biological picture that suggests multiple mechanistic differences between the BIMAs and aorta. These two different types of tissues were harvested from the patient as part of the discarded material not utilized during the CABG procedure and aorta was used as the only vascular tissue available as internal control after the surgery. Both IMAs express lower levels of genes encoding pro-atherosclerotic proteins and those involved in inflammatory processes. These protective factors appear to be shared by the mammary conduits from different patients and as a group when compared to the aortic buttons.

The LIMA and RIMA have different developmental histories and, despite their similar superior performance relative to SVGs in CABG procedures, one might expect that there could be underlying biological differences that would be reflected in patterns of differential gene expression between these tissues. Although we found a number of genes that differed in their expression between LIMA and RIMA, when we mapped these to canonical pathways and found those which were over-represented, no meaningful differences and no clear patterns of pathway regulation were found, suggesting that these two tissues are functionally very similar. When we compared aorta to BIMA samples, we found a far larger number of consistently differentially expressed genes. When we mapped these to over-represented canonical pathways and biological functions, we saw, substantial, biologically relevant patterns of gene expression. An examination of the significantly over-represented canonical pathways among the genes differentially expressed between aorta and BIMA paints a compelling picture of the differences we observed (Fig. 1A). Clinical evidence suggests that the BIMAs are protected against atherosclerotic processes and as one might expect, the genes in the annotated atherosclerosis signaling pathway are down-regulated in the BIMAs relative to aorta.

Eicosanoid signaling pathway genes are also expressed at lower levels in the BIMA tissues. Eicosanoids are signaling molecules created through oxidation of essential fatty acids and are associated with proinflammatory processes. During pathologic states such as ischemia or congestive heart failure, eicosanoids contribute to multiple maladaptive changes that include inflammation, alterations of cellular growth programs, and activation of multiple transcriptional events leading to the deleterious sequelae [37]. Aspirin and other non-steroid anti-inflammatory drugs, as well as statins, which have a protective effect in cardiovascular disease, act in part by down-regulating eicosanoid synthesis [38,39]. This is consistent with the aortic tissue exhibiting a stronger inflammatory response than the BIMAs, potentially leading increased plaque formation.

The cytokine macrophage migration inhibitory factor (MIF) has been shown to be a key regulator of acute and chronic immunoinflammatory conditions including rheumatoid arthritis (RA), atherosclerosis, and more recently systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) and to act through the regulation of glucocorticoids [19,40]; it has been suggested as a possible therapeutic target for atherosclerosis [41]. Arachidonic acid is a polyunsaturated omega-6 fatty acid that has been associated with an increased risk for cardiovascular disease [42] and its metabolites have been reported to mediate the interaction between platelets and blood vessel walls [43] as well as playing a role in vasodilation. Liver X receptors (LXR) are members of the nuclear receptor family of proteins that are critical for the control of lipid homeostasis in vertebrates. LXRs serve as cholesterol sensors that regulate the expression of multiple genes involved in the efflux, transport, and excretion of cholesterol and have been linked to atherosclerosis. LXR/retinoic X receptor (RXR) activation has been linked to the enhancement of the basolateral efflux of cholesterol [44] and synthetic LXR agonists have been shown to inhibit the development of atherosclerosis in murine models [45]. Finally, atherosclerosis has been associated with increased expression of hepatic inflammatory markers. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor (PPAR−)-α agonists have been found to moderate those inflammatory response markers both in the vascular wall and the liver. They also regulate the expression of key genes involved in lipid homeostasis and modulate the inflammatory response both in the vascular wall and the liver [46].

Analysis of over-represented biological functions paints a less-specific picture of the functional differences between the aorta and BIMAs, although one that is consistent with mechanisms was found in the pathway analysis. The significant functional classes include inflammatory response, infectious diseases, cell-to-cell signaling and interaction, immunological disease, cardiovascular disease, cell signaling, cell cycle, cellular assembly and organization, cellular compromise, and hypersensitivity response (Fig. 1B and Supplementary material).

To better understand the overriding biological processes represented among the significant pathways and gene functional classes we found, we used IPA to generate “enriched local networks” based on the connectivity of the significant gene sets to other genes annotated in the IPKB (Fig. 5). Networks associated with “inflammatory response” as well as with “cellular movement” and “lipid metabolism” highlight a central role for NF-κB. NF-κB is also an important regulator in cell fate decisions, such as programmed cell death and proliferation control, and is critical in a wide range of disease processes [34]. NF-κB stimulates transcription of Cyclin-D1, a key regulator of G1 checkpoint control. Inappropriate activation of NF-κB has been linked to inflammatory events associated with a variety of diseases, including atherosclerosis [35], where it has been shown to be present in the coronary vasculature in hypercholesterolemia [36].

As we have shown previously, there are also strong clinical advantages to using IMAs in CABG8. In addition to the improved patency and survival rates associated with BIMA use, it has also been shown that the mammaries actually retard the progression of CAD [47] and that the BIMAs provide protection against atherosclerosis to the entire target vessel [48]. Clearly the final choice regarding the use of one type of conduit or another during CABG is left to the surgeon performing the procedure. We are very aware that there are a multitude of factors that impact that decision process ranging from the quality of the target vessel, run off and or degree of stenosis to patient factors such as age, poorly controlled diabetes, and obesity, among others, that should be considered when planning to use the two mammary arteries during CABG.

Our hope is that the supporting transcriptional evidence presented here, which suggests a mechanism for the observed protective effect, provides the additional evidence necessary to persuade surgeons to favorably reconsider the use of BIMAs as the primary conduits for CABG. Larger studies that include the analysis of both genetic and clinical data are needed to further establish the connection between the differential gene expression of BIMAs and the superior outcomes observed when they are used in CABG. Our data should be interpreted as an addition to the overwhelming amount of clinical and imaging information already present in the literature regarding the superior outcomes of BIMA use during CABG. Our work, basically, suggests that if the use of one of those conduits (LIMA) has become the standard of care in coronary revascularization there should be no reason to think that two of those bypasses would not be a better operation for patients undergoing CABG.

Our transcriptional analysis of human surgically resected specimens provides biological support for the use of BIMAs as conduits in CABG and reinforces the successes seen in clinical practice. The arterial revascularization trial which has completed enrollment will provide the multi-institutional prospective randomized data currently lacking on this topic. Unfortunately, we will have to wait until 2018 to see the final results of this study. In the meantime, it appears that each patient, in spite of his/her particular clinical situation, holds within him/her a truly unique set of conduits that are still highly underutilized in the US (4% use of BIMA in CABG).

It should be noted that there are several limitations to the analysis we present here. As a retrospective study, the patients were nonrandomized. In addition, these patients have no post-procedural angiographic imaging data to establish graft patency status. This study was conducted at a single medium-sized suburban hospital and as a result, slightly different results could be observed in another setting or with a different demographic population. Despite these limitations, the transcriptomic analysis presented here is entirely consistent with the existing clinical data.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ygeno.2014.04.005.

References

- 1.Suma H, Tanabe H, Takahashi A, Horii T, Isomura T, Hirose H, Amano A. Twenty years experience with the gastroepiploic artery graft for CABG. Circulation. 2007;116:1188–1191. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.678813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shah PJ, Bui K, Blackmore S, Gordon I, Hare DL, Fuller J, Seevanayagam S, Buxton BF. Has the in situ right internal thoracic artery been overlooked? An angiographic study of the radial artery, internal thoracic arteries and saphenous vein graft patencies in symptomatic patients. Eur. J. Cardiothorac. Surg. 2005;27:870–875. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcts.2005.01.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Buxton BF, Ruengsakulrach P, Fuller J, Rosalion A, Reid CM, Tatoulis J. The right internal thoracic artery graft — benefits of grafting the left coronary system and native vessels with a high grade stenosis. Eur. J. Cardiothorac. Surg. 2000;18:255–261. doi: 10.1016/s1010-7940(00)00527-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Grau JB, Ferrari G, Mak RE, Shaw AW, Brizzio ME, Mindich BP, Strobeck J, Zapolanski A. Propensity matched analysis of bilateral internal mammary artery versus single left internal mammary artery grafting at 17-year follow-up: validation of a contemporary surgical experience. Eur. J. Cardiothorac. Surg. 2012;41(4):770–776. doi: 10.1093/ejcts/ezr213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Puskas JD, Sadiq A, Vassiliades TA, Kilgo PD, Lattouf OM. Bilateral internal thoracic artery grafting is associated with significantly improved long-term survival, even among diabetic patients. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 2012;94:710–716. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2012.03.082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Joo HC, Youn YN, Yi G, Chang BC, Yoo KJ. Off-pump bilateral internal thoracic artery grafting in right internal thoracic artery to right coronary system. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 2012;94:717–724. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2012.04.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kitamura S. Physiological and metabolic effects of grafts in coronary artery bypass surgery. Circ. J. 2011;75:766–772. doi: 10.1253/circj.cj-10-1302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Manninen HI, Jaakkola P, Suhonen M, Rehnberg S, Vuorenniemi R, Matsi PJ. Angiographic predictors of graft patency and disease progression after coronary artery bypass grafting with arterial and venous grafts. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 1998;66:1289–1294. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(98)00757-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Antoniades C, Shirodaria C, Van Assche T, Cunnington C, Tegeder I, Lotsch J, Guzik TJ, Leeson P, Diesch J, Tousoulis D, Stefanadis C, Costigan M, Woolf CJ, Alp NJ, Channon KM. GCH1 haplotype determines vascular and plasma biopterin availability in coronary artery disease effects on vascular superoxide production and endothelial function. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2008;52:158–165. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.12.062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dungan JR, Conley YP, Langaee TY, Johnson JA, Kneipp SM, Hess PJ, Yucha CB. Altered beta-2 adrenergic receptor gene expression in human clinical hypertension. Biol. Res. Nurs. 2009;11:17–26. doi: 10.1177/1099800409332538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Glineur D, D'Hoore W, de Kerchove L, Noirhomme P, Price J, Hanet C, El Khoury G. Angiographic predictors of 3-year patency of bypass grafts implanted on the right coronary artery system: a prospective randomized comparison of gastroepiploic artery, saphenous vein, and right internal thoracic artery grafts. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2011;142:980–988. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2011.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rudner XL, Berkowitz DE, Booth JV, Funk BL, Cozart KL, D'Amico EB, El-Moalem H, Page SO, Richardson CD, Winters B, Marucci L, Schwinn DA. Subtype specific regulation of human vascular alpha(1)-adrenergic receptors by vessel bed and age. Circulation. 1999;100:2336–2343. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.100.23.2336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mangoush O, Athanasiou T, Nakamura K, Johnson P, Smoienski R, Sarathchandra P, Oury T, Chester AH, Amrani M. Antioxidant properties of the internal thoracic artery and the radial artery. Heart Lung Circ. 2008;17:40–47. doi: 10.1016/j.hlc.2007.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yang Z, Oemar BS, Carrel T, Kipfer B, Julmy F, Luscher TF. Different proliferative properties of smooth muscle cells of human arterial and venous bypass vessels: role of PDGF receptors, mitogen-activated protein kinase, and cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitors. Circulation. 1998;97:181–187. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.97.2.181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mompeo B, Tscheuschilsuren G, Aust G, Metz S, Spanel-Borowski K. Estrogen receptor expression and synthesis in the human internal thoracic artery. Ann. Anat. 2003;185:57–65. doi: 10.1016/S0940-9602(03)80011-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Marchand A, Atassi F, Gaaya A, Leprince P, Le Feuvre C, Soubrier F, Lompre AM, Nadaud S. The Wnt/beta-catenin pathway is activated during advanced arterial aging in humans. Aging Cell. 2011;10:220–232. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2010.00661.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Payeli SK, Latini R, Gebhard C, Patrignani A, Wagner U, Luscher TF, Tanner FC. Prothrombotic gene expression profile in vascular smooth muscle cells of human saphenous vein, but not internal mammary artery. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2008;28:705–710. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.107.155333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sato A, Sheppard KE, Fullerton MJ, Sviridov DD, Funder JW. Glucocorticoid receptor expression is down-regulated by Lp(a) lipoprotein in vascular smooth muscle cells. Endocrinology. 1995;136:3707–3713. doi: 10.1210/endo.136.9.7649076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Burger-Kentischer A, Goebel H, Seiler R, Fraedrich G, Schaefer HE, Dimmeler S, Kleemann R, Bernhagen J, Ihling C. Expression of macrophage migration inhibitory factor in different stages of human atherosclerosis. Circulation. 2002;105:1561–1566. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000012942.49244.82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Arishiro K, Hoshiga M, Ishihara T, Kondo K, Hanafusa T. Connexin 43 expression is associated with vascular activation in human radial artery. Int. J. Cardiol. 2010;145:270–272. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2009.09.479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Martinet W, Schrijvers DM, De Meyer GR, Herman AG, Kockx MM. Western array analysis of human atherosclerotic plaques: downregulation of apoptosis-linked gene 2. Cardiovasc. Res. 2003;60:259–267. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(03)00537-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Besnard S, Heymes C, Merval R, Rodriguez M, Galizzi JP, Boutin JA, Mariani J, Tedgui A. Expression and regulation of the nuclear receptor RORalpha in human vascular cells. FEBS Lett. 2002;511:36–40. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(01)03275-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.He GW, Fan L, Grove KL, Fumary A, Yang Q. Expression and function of endothelial nitric oxide synthase messenger RNA and protein are higher in internal mammary than in radial arteries. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 2011;92:845–850. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2011.04.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Li DY, Chen HJ, Staples ED, Ozaki K, Annex B, Singh BK, Vermani R, Mehta JL. Oxidized low-density lipoprotein receptor LOX-1 and apoptosis in human atherosclerotic lesions. J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacol. Ther. 2002;7:147–153. doi: 10.1177/107424840200700304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wu Z, Irizarry RA, Gentleman R, Martinez-Murillo F, Spencer F. A model-based background adjustment for oligonucleotide expression arrays. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 2004;99:909–917. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Smyth GK. Linear models and empirical Bayes methods for assessing differential expression in microarray experiments. Stat. Appl. Genet. Mol. Biol. 2004;3 doi: 10.2202/1544-6115.1027. (Article3). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.He GW. Arterial grafts: clinical classification and pharmacological management. Ann. Cardiothorac. Surg. 2013;2:507–518. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2225-319X.2013.07.12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.He GW, Yang Q, Yang CQ. Smooth muscle and endothelial function of arterial grafts for coronary artery bypass surgery. Clin. Exp. Pharmacol. Physiol. 2002;29:717–720. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1681.2002.03705.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Beamish JA, He P, Kottke-Marchant K, Marchant RE. Molecular regulation of contractile smooth muscle cell phenotype: implications for vascular tissue engineering. Tissue Eng. B Rev. 2010;16:467–491. doi: 10.1089/ten.teb.2009.0630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Colomer JM, Mao L, Rockman HA, Means AR. Pressure overload selectively up-regulates Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II in vivo. Mol. Endocrinol. 2003;17:183–192. doi: 10.1210/me.2002-0350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Passier R, Zeng H, Frey N, Naya FJ, Nicol RL, McKinsey TA, Overbeek P, Richardson AJ, Grant SR, Olson EN. CaM kinase signaling induces cardiac hypertrophy and activates the MEF2 transcription factor in vivo. J. Clin. Invest. 2000;105:1395–1406. doi: 10.1172/JCI8551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Branchetti E, Sainger R, Poggio P, Grau JB, Patterson-Fortin J, Bavaria JE, Chorny M, Lai E, Gorman RC, Levy RJ, Ferrari G. Antioxidant enzymes reduce DNA damage and early activation of valvular interstitial cells in aortic valve sclerosis. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2013;33:e66–e74. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.112.300177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Branchetti E, Poggio P, Sainger R, Shang E, Grau JB, Jackson BM, Lai EK, Parmacek RC, Gorman MS, Gorman JH, Bavaria JE, Ferrari G. Oxidative stress modulates vascular smooth muscle cell phenotype via CTGF in thoracic aortic aneurysm. Cardiovasc. Res. 2013;100:316–324. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvt205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Baldwin AS., Jr The NF-kappa B and I kappa B proteins: new discoveries and insights. Annu Rev. Immunol. 1996;14:649–683. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.14.1.649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hinz M, Krappmann D, Eichten A, Heder A, Scheidereit C, Strauss M. NF-kappaB function in growth control: regulation of cyclin D1 expression and G0/G1-to-S-phase transition. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1999;19:2690–2698. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.4.2690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wilson SH, Caplice NM, Simari RD, Holmes DR, Jr, Carlson PJ, Lerman A. Activated nuclear factor-kappaB is present in the coronary vasculature in experimental hypercholesterolemia. Atherosclerosis. 2000;148:23–30. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9150(99)00211-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jenkins CM, Cedars A, Gross RW. Eicosanoid signalling pathways in the heart. Cardiovasc. Res. 2009;82:240–249. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvn346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Robinson DR. Eicosanoids, inflammation, and anti-inflammatory drugs. Clin. Exp. Rheumatol. 1989;7(Suppl. 3):S155–S161. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Santos MT, Fuset MP, Ruano M, Moscardo A, Valles J. Effect of atorvastatin on platelet thromboxane A(2) synthesis in aspirin-treated patients with acute myocardial infarction. Am J. Cardiol. 2009;104:1618–1623. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2009.07.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Santos LL, Morand EF. Macrophage migration inhibitory factor: a key cytokine in RA SLE and atherosclerosis. Clin. Chim. Acta. 2009;399:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2008.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bernhagen J, Krohn R, Lue H, Gregory JL, Zernecke A, Koenen RR, Dewor M, Georgiev I, Schober A, Leng L, Kooistra T, Fingerle-Rowson G, Ghezzi P, Kleemann R, McColl SR, Bucala R, Hickey MJ, Weber C. MIF is a noncognate ligand of CXC chemokine receptors in inflammatory and atherogenic cell recruitment. Nat. Med. 2007;13:587–596. doi: 10.1038/nm1567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Harris WS, Mozaffarian D, Rimm E, Kris-Etherton P, Rudel LL, Appel LJ, Engler MM, Engler MB, Sacks F. Omega-6 fatty acids and risk for cardiovascular disease: a science advisory from the American Heart Association Nutrition Subcommittee of the Council on Nutrition, Physical Activity, and Metabolism; Council on Cardiovascular Nursing; and Council on Epidemiology and Prevention. Circulation. 2009;119:902–907. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.191627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Moncada S, Vane JR. Arachidonic acid metabolites and the interactions between platelets and blood-vessel walls. N. Engl. J. Med. 1979;300:1142–1147. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197905173002006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Murthy S, Born E, Mathur SN, Field FJ. LXR/RXR activation enhances basolateral efflux of cholesterol in CaCo-2 cells. J. Lipid Res. 2002;43:1054–1064. doi: 10.1194/jlr.m100358-jlr200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tontonoz P, Mangelsdorf DJ. Liver X receptor signaling pathways in cardiovascular disease. Mol. Endocrinol. 2003;17:985–993. doi: 10.1210/me.2003-0061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zambon A, Gervois P, Pauletto P, Fruchart JC, Staels B. Modulation of hepatic inflammatory risk markers of cardiovascular diseases by PPAR-alpha activators: clinical and experimental evidence. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2006;26:977–986. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000204327.96431.9a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Otsuka F, Yahagi K, Sakakura K, Virmani R. Why is the mammary artery so special and what protects it from atherosclerosis? Ann. Cardiothorac. Surg. 2013;2:519–526. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2225-319X.2013.07.06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tarr FI, Sasvari M, Tarr M, Racz R. Evidence of nitric oxide produced by the internal mammary artery graft in venous drainage of the recipient coronary artery. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 2005;80:1728–1731. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2005.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.