Abstract

Cell-specific patterns of gene expression are established through the antagonistic functions of trithorax group (TrxG) and Polycomb group (PcG) proteins. Several muscle-specific genes have previously been shown to be epigenetically marked for repression by PcG proteins in muscle progenitor cells. Here we demonstrate that these developmentally regulated genes become epigenetically marked for gene expression (trimethylated on histone H3 Lys4, H3K4me3) during muscle differentiation through specific recruitment of Ash2L-containing methyltransferase complexes. Targeting of Ash2L to specific genes is mediated by the transcriptional regulator Mef 2d. Furthermore, this interaction is modulated during differentiation through activation of the p38 MAPK signaling pathway via phosphorylation of Mef 2d. Thus, we provide evidence that signaling pathways regulate the targeting of TrxG-mediated epigenetic modifications at specific promoters during cellular differentiation.

Cell-specific gene expression programs are established during embryo-genesis through transient environmental signals. These programs are then stably maintained and passed to daughter cells through a process of cellular memory. Experiments in Drosophila melanogaster have identified PcG and TrxG proteins as the mediators of this memory1. The list of genes that fall into PcG and TrxG protein groups is extensive1,2, but those of known function are modifiers of chromatin structure: histone methyltransferases, ubiquitin E3 ligases and ATP-dependent chromatin-remodeling factors. This suggests that epigenetic modification of chromatin is important in establishing cellular memory.

PcG and TrxG proteins act antagonistically to establish and maintain tissue-specific patterns of gene expression, the former marking genes for repression whereas the later marks genes for expression. This is accomplished in part through trimethylation of histone H3 at Lys9 (H3K9me3) and/or Lys27 (H3K27me3) for repressed genes, and through the H3K4me3 modification for active genes1,3. Indeed, studies based on chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) coupled to DNA microarray analysis (ChIP-chip experiments) have suggested that developmentally regulated genes that are actively expressed are enriched for the H3K4me3 epigenetic mark in the 5′ ends of their coding sequences4. The H3K27me3 and H3K9me3 modifications are enriched in facultative and constitutive heterochromatin, respectively5. Repression of transcription by PcG proteins is thought to be the default state, as these proteins can be found at both active and inactive genes, whereas TrxG proteins seem to be specifically targeted to active genes6. In agreement with this, loss of TrxG function prevents the expression of developmentally regulated genes7. In contrast, double mutations, where both a PcG protein (Ez) and a TrxG protein (Ash1) are mutated, result in ectopic expression of the developmentally regulated Hox genes8. This suggests that TrxG proteins act as anti-repressors to ensure that PcG proteins do not repress expression of developmentally important genes in specific tissues.

During myogenesis, the Mef2 family of MADS-box transcription factors and the muscle-specific transactivator MyoD target specific promoters9 to establish a precise gene expression program, ultimately resulting in the formation of multinucleated myotubes. This myogenic gene expression program is temporally ordered10 and is proposed to be mediated through a feed-forward mechanism11. Among the co-factors feeding into the myogenic program is the p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK)11, which is crucial in establishing the muscle-specific gene expression program10–13.

Although several important factors responsible for establishing muscle-specific gene expression have been identified, the mechanism by which transcription is activated at muscle-specific loci has remained elusive. Some insight has come from studies demonstrating that several muscle-specific genes are epigenetically marked for repression (by H3K27me3 or H3K9me3) in growing myoblasts14,15. In the case of H3K27me3-marked genes, it has been shown that the transcriptional regulator YY1 targets the PcG protein Ezh2 to promoters14. The fact that muscle-specific genes are targeted for repression by PcG proteins suggests that activation of these genes should require the anti-repressive function of TrxG proteins. We set out to determine whether muscle-specific genes are epigenetically marked for gene expression in differentiating mouse C2C12 myoblasts, and if so, how TrxG proteins are targeted to these promoters.

Results

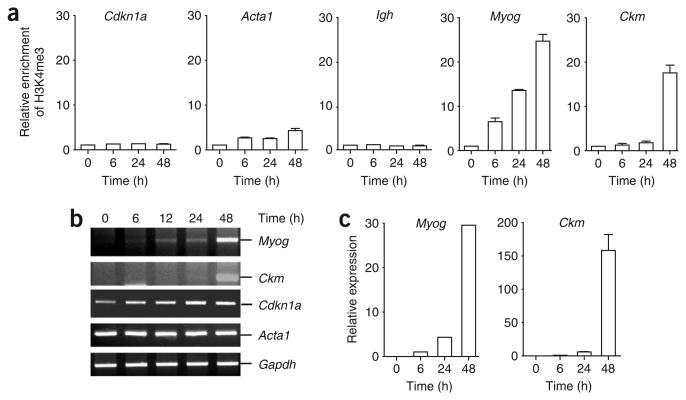

Specific genes are marked for expression during myogenesis

It has been proposed that genes poised for transcription are marked by H3K4me2, whereas those actively transcribing are marked by H3K4me3 (refs. 4,16). Here we set out to examine whether genes that are expressed during myogenesis are marked by H3K4me3 during the transactivation process. The mouse C2C12 myoblast cell line was used as a model for these studies, as it can be induced to undergo myogenesis under conditions of serum withdrawal17. To avoid potential epitope masking by proteins that bind modified histone tails, we used a native ChIP protocol to immunoprecipitate nucleosomes with an H3K4me3-specific antibody. Using hydrolysis probes for quantitative PCR (qPCR) that recognized the 5′ ends of the genes, we found that both the Myog and Ckm genes became enriched in nucleosomes containing H3K4me3 during C2C12 cell differentiation (Fig. 1a). This enrichment coincided temporally with the increased expression of these two genes during myogenesis (Fig. 1b,c). Consistent with previous results suggesting that not all active genes are enriched for the H3K4me3 mark18, we did not observe extensive enrichment of this mark in the transcribed Acta1 gene (Fig. 1a,b). Similarly, no enrichment of H3K4me3 was observed at the Cdkn1a gene, which is transcribed before differentiation and whose expression is further upregulated during myogenesis, nor was there enrichment at the transcriptionally silent Igh locus (Fig. 1a,b). Expanding our analysis to examine the distribution of H3K4me2 and H3K4me3 epigenetic marks across the Myog gene during C2C12 differentiation, we observed that the promoter region is enriched for the H3K4me2 mark, whereas the H3K4me3 mark peaks within the transcribed region of the gene (Supplementary Fig. 1 online).

Figure 1.

Muscle-specific genes are trimethylated at H3K4 during myogenesis. (a) Growing (0 h) or differentiating (6, 24 or 48 h) C2C12 cells were subjected to native ChIP analysis with antibodies to H3K4me3 or control rabbit IgG. Immunopurified nucleosomes were then deproteinated and subjected to qPCR analysis with primers recognizing the genes indicated. Average values of duplicate qPCR reactions are shown; error bars represent s.d. Each experiment was performed at least twice with independent chromatin samples and yielded similar results both times. (b) RNA was extracted from growing or differentiating C2C12 cells, reverse-transcribed and subjected to semiquantitative PCR analysis of gene expression with primers specific for the transcripts indicated. (c) cDNA was prepared as in b and subjected to qPCR analysis of gene expression with primers specific for either the Myog or Ckm transcripts and with primers specific for 18S RNA. Expression is reported relative to the control 18S RNA signal. Average values of triplicate qRT-PCR reactions are shown; error bars represent s.d. Each experiment was performed at least twice with independently isolated RNA.

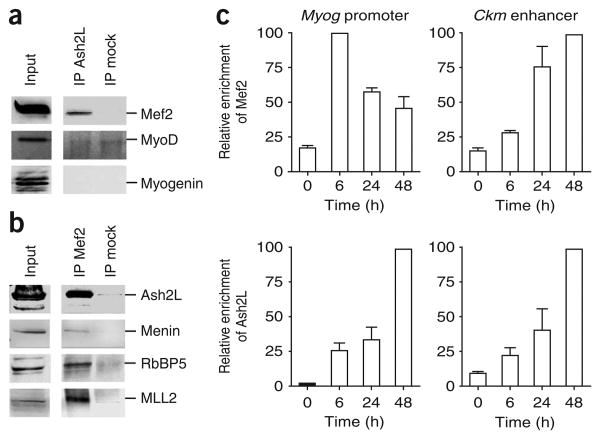

Ash2L associates with Mef 2d

Recent studies have suggested that the Ash2L protein is required for H3K4me3 to occur at specific loci19,20. As Ash2L is expressed in both skeletal muscle21 and C2C12 cells (Supplementary Fig. 2a online), we examined whether Ash2L-containing complexes may be recruited to muscle-specific genes by developmentally regulated transcriptional activators. To identify candidate transcriptional activators that mediate recruitment of TrxG proteins, we turned to the Myog promoter. In this promoter, DNA binding elements responsible for establishing cellular memory should lie in a fragment of DNA containing the region between positions −184 and +18 relative to the Myog transcription start site, as this region is sufficient to ensure muscle-specific expression of the gene22,23. As Myog has a well-characterized promoter22–26, we looked for interactions between Ash2L and transcriptional activators known to bind this region. Western blotting analysis of proteins co-immunoprecipitating with Ash2L indicated the presence of Mef 2 but not the muscle-specific transcriptional activators MyoD or myogenin (Fig. 2a). In a reciprocal experiment, immunoprecipitation of Mef 2 with a pan-Mef 2 antibody confirmed the interaction between the transcriptional activator and the Ash2L complex subunits Ash2L, RbBP5 and menin, along with the methyltransferase MLL2 (Fig. 2b). Furthermore, methyltransferase assays performed with Mef 2 immunoprecipitates confirmed that the transcriptional activator associates with an H3K4 methyltransferase activity in differentiating C2C12 cell extracts (Supplementary Fig. 2c,d). Notably, the association between Ash2L and Mef 2 was not observed in undifferentiated C2C12 cells or at the early stages of differentiation (data not shown), suggesting that the interaction between these proteins may be developmentally regulated. As Ash2L is present in at least five known methyltransferase complexes27, we examined whether the interaction between Ash2L and Mef 2 is limited to MLL2-containing complexes. Using antibodies directed against various H3K4 methyltransferases, we were able to immunoprecipitate Mef 2 with antibodies to MLL2, Set1 and MLL3, but not MLL or MLL4 (Supplementary Fig. 2b). Thus, Mef 2 can interact with several Ash2L complexes, but it preferentially interacts with MLL2-containing complexes.

Figure 2.

Mef2 interacts with the Ash2L methyltransferase complex. (a) Mef2 co-immunoprecipitates with Ash2L in C2C12 cells. Nuclear extracts prepared from differentiating C2C12 cells (48 h) were subjected to immunoprecipitation (IP) with anti-Ash2L or control IgG (mock). Immunoprecipitated proteins were analyzed by western blotting with indicated antibodies. (b) Cell extracts prepared from differentiating C2C12 cells (48 h) were subjected to immunoprecipitation with anti-Mef2 or control IgG antibody. Immunoprecipitated proteins were analyzed by western blotting with indicated antibodies. (c) Relative recruitment of Mef2 or Ash2L was measured by ChIP at the Myog promoter or Ckm enhancer at indicated time points during differentiation. After deproteination, immunopurified DNA was quantified by qRT-PCR with hydrolysis probes. Average values of duplicate qRT-PCR reactions are shown; error bars represent s.d. Each experiment was performed at least twice with independent chromatin samples and yielded similar results both times.

To determine whether Mef 2 recruits the Ash2L complex to mediate H3K4 trimethylation on muscle-specific genes, we used ChIP analysis to measure the binding of these two factors to the Myog and Ckm promoters during C2C12 differentiation. Consistent with an association between Mef 2 and the Ash2L complex, we observed a good correlation of their recruitment to the Ckm promoter (Fig. 2c). In contrast, the recruitment of Ash2L did not coincide temporally with the recruitment of Mef 2 at the Myog gene. Instead, Mef 2 was recruited to the Myog promoter within 6 h after serum withdrawal, whereas recruitment of Ash2L, marking of nucleosomes by H3K4me3 and gene activation were maximal at later stages (48 h) in the differentiation process (Fig. 1 and Fig. 2c). Thus, recruitment of Ash2L is temporally distinct from that of Mef 2 at the Myog promoter.

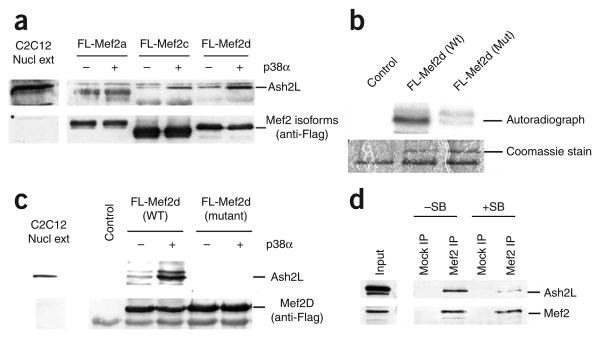

Phosphorylation of Mef 2d permits association with Ash2L

As our antibody recognizes all four Mef 2 isotypes (Mef 2a, Mef 2b, Mef 2c and Mef 2d), one possibility is that Ash2L interacts with a specific Mef 2 isotype whose expression or activity changes during differentiation. To test this possibility, we studied interactions between Ash2L and the three Mef 2 isotypes that are known to be expressed in muscle. Baculoviruses encoding C-terminally Flag-tagged Mef 2a (FL-Mef 2a), Mef 2c (FL-Mef 2c) and Mef 2d (FL-Mef 2d) were engineered. Recombinant Mef 2 proteins were then purified from baculovirus-infected Sf 9 cell extracts using M2-Flag agarose beads. As phosphorylation has been proposed to activate Mef 2 gene products28, the different purified Mef 2 proteins were incubated in the presence (or absence) of active p38α MAPK29 before incubation with an extract prepared from differentiating (48 h) C2C12 cells. Although Ash2L did not bind FL-Mef 2a, we consistently observed an interaction with FL-Mef 2d (Fig. 3a). Notably, this interaction was enhanced when FL-Mef 2d was phosphorylated by p38α. A weaker interaction between p38α-treated FL-Mef 2c and Ash2L could also be seen. Thus, Ash2L seems to associate selectively with the phosphorylated Mef 2d isotype (and, to a lesser extent, with phosphorylated Mef 2c). It is not clear why Mef 2a does not also interact with Ash2L. However, it is not a case of differential β-exon usage, as all three constructs contained the previously described isoform-specific acidic transactivation domain30. We did observe some interaction between Ash2L and Mef 2d in the absence of exogenous p38α. This is probably due to the presence of endogenous p38 activity present in the C2C12 cell extracts.

Figure 3.

Ash2L interacts preferentially with phosphorylated Mef2d and Mef2c. (a) Flag-tagged Mef2a, Mef2c or Mef2d treated with activated p38α (or untreated) were incubated with extract prepared from differentiating (48 h) C2C12 cells. After washing, Mef2-associated proteins were subjected to western blotting analysis with anti-Ash2L or anti-Flag. (b) Flag-tagged wild-type (WT) or mutant Mef2d were incubated with activated p38α and [32P]ATP. Reactions were separated by SDS-PAGE. (c) Interaction studies with Flag-tagged WT and mutant Mef2d as in a. (d) Cell extracts prepared from differentiating C2C12 cells (48 h) that had been incubated in the presence (+SB) or absence (−SB) of the p38 MAPK inhibitor SB203580 were subjected to immunoprecipitation with anti-Mef2 or control IgG. Immunoprecipitated proteins were analyzed by western blotting with indicated antibodies.

To examine the importance of Mef 2d phosphorylation by p38α in mediating its interaction with Ash2L, we generated a Mef 2d construct with mutated consensus p38 phosphorylation sites (T308A T315A). These mutations greatly reduced in vitro phosphorylation of the Mef 2d protein by p38α (Fig. 3b) and completely blocked its interaction with Ash2L (Fig. 3c). Furthermore, this protein behaved as a dominant-negative mutant, leading to decreased expression of the endogenous Myog gene in transfected C2C12 cells (Supplementary Fig. 3 online). To further confirm that p38-dependent phosphorylation of Mef 2d regulates its interaction with Ash2L, we immunoprecipitated Mef 2 from extracts of C2C12 cells that had been differentiated in the presence or absence of the p38 MAPK inhibitor SB203580. Use of this p38α/β-specific kinase inhibitor has previously been demonstrated to block phosphorylation of Mef 2 proteins in differentiating L8 myoblasts13. As expected, treatment of C2C12 cells with SB203580 markedly reduced the amount of Ash2L that co-immunoprecipitated with Mef 2 (Fig. 3d). These results suggest that Ash2L interacts with phosphorylated Mef 2d.

As the interaction between Ash2L and Mef 2d was not observed in growing myoblasts, we examined whether expression of the transcriptional activator is upregulated during C2C12 cell differentiation. However, both semiquantitative reverse-transcription (RT)-PCR and western blotting analysis showed that Mef 2d levels remained relatively constant throughout C2C12 differentiation (Supplementary Fig. 4 online). Therefore, we next examined whether p38 MAPK activity varies during C2C12 differentiation. In accordance with previous reports12, we found that levels of total p38 remained constant throughout differentiation. In contrast, there was markedly more active (phosphorylated) p38 during differentiation, with the maximal amount attained 48 h after serum withdrawal (Supplementary Fig. 4b). Thus, our results suggest that Mef 2d recruits Ash2L to muscle-specific promoters in a p38-dependent manner.

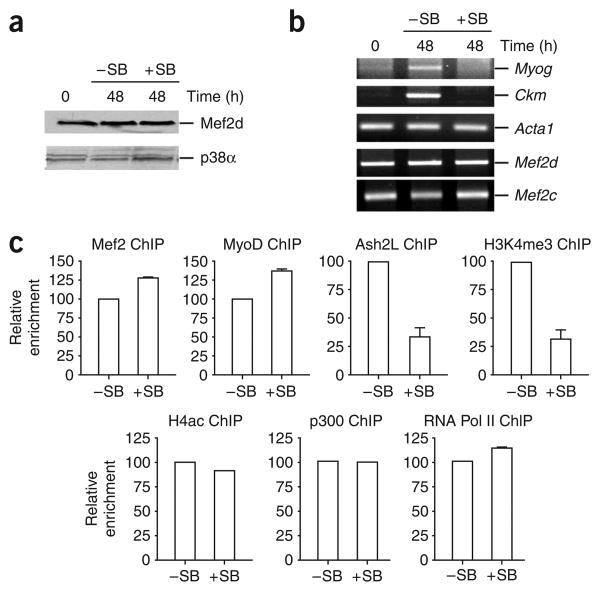

p38 regulates recruitment of Ash2L to muscle-specific promoters

To examine this possibility in vivo, we performed ChIP experiments with C2C12 cells that had been differentiated in the presence of SB203580. Treatment of C2C12 cells with SB203580 did not affect total p38 levels in the cell (Fig. 4a). As previously observed31, expression of both Ckm and Myog in differentiating C2C12 was inhibited by SB203580 treatment (Fig. 4b). This is not a global effect on transcription, as expression of Acta1, Mef 2c and Mef 2d was not affected. Furthermore, ChIP experiments demonstrated that the block in transcription at the Myog and Ckm genes was not due to reduced recruitment of MyoD, Mef2, p300 or RNA polymerase II (Pol II) to these loci (Fig. 4c and Supplementary Fig. 5 online). Similarly, acetylation of histone H4 (H4ac) was not affected by SB203580 treatment, suggesting that the promoters are poised for transcription. Treatment of differentiating C2C12 cells with SB203580 did, however, substantially decrease Ash2L recruitment and H3K4me3 at both of these muscle-specific promoters (Fig. 4c and Supplementary Fig. 5). This shows that p38 kinase activity is required in vivo for efficient recruitment of the Ash2L complex and H3K4 trimethylation at the Myog and Ckm promoters.

Figure 4.

Inhibition of p38 MAPK activity prevents recruitment of Ash2L to the Myog promoter. (a) Protein extracts prepared from C2C12 cells treated with SB203580 (+SB) or untreated (−SB) under either growth (0 h) or differentiation (48 h) conditions were analyzed by western blotting with indicated antibodies. (b) Inhibition of p38 kinase activity blocks transcription of several muscle-specific genes in C2C12 cells. RNA was isolated from +SB or −SB C2C12 cells under either growth or differentiation conditions. After reverse transcription, random primed cDNA was subjected to semiquantitative PCR analysis with primers specific for the genes indicated. (c) Inhibition of p38 kinase activity blocks recruitment of Ash2L and prevents H3K4me3 modification at the Myog promoter. ChIP was used to measure relative enrichment of the indicated proteins at the Myog promoter in C2C12 cells differentiated (48 h) in the presence or absence of SB203580. After deproteination, immunopurified DNA was quantified by qRT-PCR with hydrolysis probes. Average values of duplicate qRT-PCR reactions are shown; error bars represent s.d. Each experiment was performed at least twice with independent chromatin samples and yielded similar results both times.

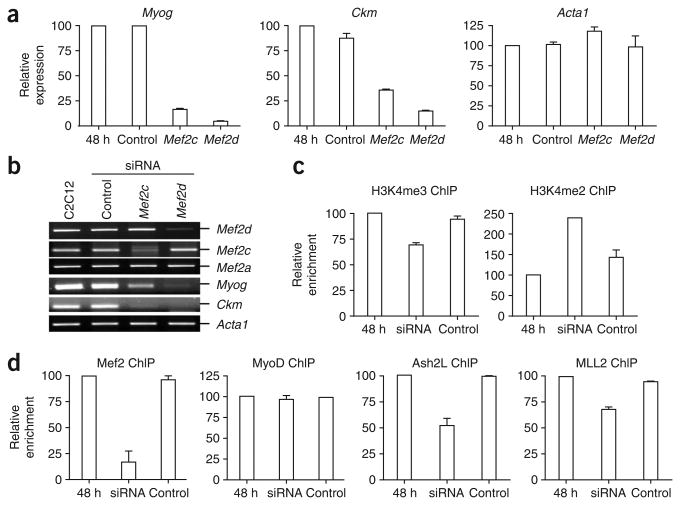

To confirm that Ash2L is recruited to the muscle-specific promoters through an Mef 2-dependent mechanism, we used short interfering RNA (siRNA)-mediated knockdown of Mef 2d and Mef 2c in C2C12 cells. Whereas the knockdowns did not appreciably affect Acta1 expression, both Myog and Ckm genes were markedly downregulated in response to knockdown of Mef 2d or Mef 2c (Fig. 5a,b). Because both Mef 2c and Mef 2d are required for maximal transactivation of the Ckm and Myog genes (Fig. 5b), we decided to knock down both Mef 2 isotypes in the same population of C2C12 cells for ChIP studies (Fig. 5c,d). Analysis of promoter occupancy at both the Ckm and Myog genes revealed that the siRNA treatment reduced recruitment of Mef 2 during differentiation by 80%, whereas MyoD levels remained constant (Fig. 5d and Supplementary Fig. 6 online). Loss of Mef 2 binding at these promoters coincided with decreased H3K4me3 and a concomitant increase in H3K4 dimethylation (Fig. 5c and Supplementary Fig. 6). Similarly, knockdown of Mef 2d markedly decreased recruitment of both Ash2L and MLL2 to the Myog and Ckm promoters (Fig. 5d and Supplementary Fig. 6). Our observation that Ash2L binding was reduced by only 50% when Mef 2 binding was reduced by 80% is probably explained by the ability of the TrxG complex to interact with multiple elements in the promoter region, including CBP/p300 (ref. 32), unmethylated CpG dinucleotides33 and H3K4me2 (ref. 34). Thus, although phosphorylated Mef 2d is probably required for initial recruitment of Ash2L, the increased affinity accorded by multiple interactions at the promoter might further stabilize the binding of the Ash2L complex.

Figure 5.

Knockdown of Mef 2d and Mef 2c in C2C12 cells decreases Ash2L at the Myog and Ckm promoters. (a) RNA was isolated from differentiating C2C12 cells (48 h) that were untransfected or transfected with siRNA targeting Mef 2d or Mef 2c or with untargeted control siRNA. RNA was reverse-transcribed and subjected to qPCR analysis of gene expression with primers specific for Myog, Ckm or Acta1 transcripts along with primers specific for 18S RNA. Expression is reported relative to the control 18S RNA signal. Average values of triplicate qRT-PCR reactions are shown; error bars represent s.d. Each experiment was performed at least twice with independently isolated RNA. (b) cDNA was prepared as in a and analyzed by semiquantitative PCR with primers specific to the genes indicated. (c,d) C2C12 cells were transfected with siRNA targeting both Mef2c and Mef2d (such that both family members would be knocked down) or with an untargeted control siRNA. Cells were then differentiated for 48 h and analyzed by ChIP to measure enrichment of H3K4 methylation at the Myog promoter (c) or relative recruitment of transcriptional activators and coactivators (d). Immunopurified DNA was quantified by qRT-PCR with hydrolysis probes. Average values of duplicate qRT-PCR reactions are shown; error bars represent s.d. Each experiment was performed at least twice with independent chromatin samples and yielded similar results both times.

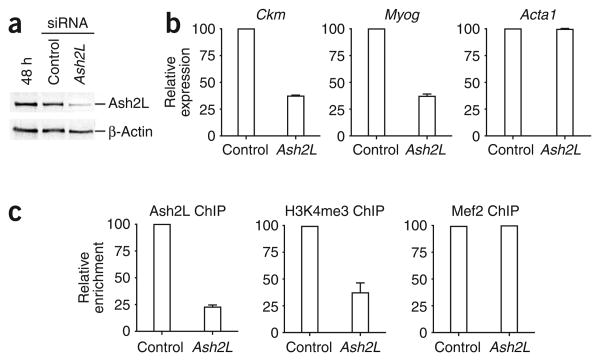

Lastly, to confirm the importance of the Ash2L complex in regulating gene expression at muscle-specific loci, we examined the effect of siRNA knockdown of Ash2L in C2C12 cells. Indeed, reduced levels of Ash2L in C2C12 cells (Fig. 6a) led to decreased expression of both the Myog and Ckm genes while having no effect on Acta1 RNA levels during muscle differentiation (Fig. 6b). This decreased expression can be correlated with reduced recruitment of Ash2L and less H3K4me3 at the Myog gene (Fig. 6c) and Ckm gene (data not shown). Thus, our studies reveal that establishment of the H3K4me3 mark at the Myog and Ckm promoters during muscle differentiation occurs through a series of ordered events involving Mef 2d phosphorylation by p38 MAPK and subsequent recruitment of the Ash2L methyltransferase complex.

Figure 6.

Knockdown of Ash2L in C2C12 cells leads to reduced transcription of the Myog and Ckm genes. (a) Whole-cell extracts prepared from differentiating C2C12 cells after indicated siRNA treatments were subjected to western blotting analysis with anti-Ash2L or anti–β-actin. (b) Knockdown of Ash2L leads to decreased expression of muscle-specific genes. RNA was isolated from differentiating C2C12 cells (48 h) transfected with siRNA targeting Ash2L or with untargeted control siRNA. RNA was extracted, reverse-transcribed and subjected to qPCR analysis with primers recognizing the genes indicated. Expression is reported relative to the control 18S RNA signal. Average values of triplicate qRT-PCR reactions are shown; error bars represent s.d. Each experiment was performed at least twice with independently isolated RNA. (c) C2C12 cells were transfected with siRNA targeting Ash2L or with untargeted control siRNA. Transfected cells were then differentiated for 48 h and analyzed by ChIP for enrichment of Ash2L, H3K4me3 and Mef2 at the Myog promoter. After deproteination, immunopurified DNA was quantified by qRT-PCR with hydrolysis probes. Average values of duplicate qPCR reactions are shown; error bars represent s.d. Each experiment was performed at least twice with independent chromatin samples and yielded similar results both times.

Discussion

In this study, we show that Ash2L is recruited to muscle-specific promoters through its association with the transcriptional activator Mef 2d. Furthermore, we demonstrate that Ash2L recruitment is regulated via phosphorylation of Mef 2d by the p38 MAPK. Indeed, we observed Mef 2 recruitment to the Myog promoter early in differentiation, whereas Ash2L was not recruited until p38 activity became upregulated during later stages of differentiation. Notably, Ash2L showed different affinities for the various members of the Mef 2 family of transcriptional activators. Combined with our observation that continued expression of Mef 2a in Mef 2d- and Mef2c-knockdown cells did not allow expression of the Myog and Ckm genes, these results demonstrate that the Mef 2 isotypes have different functions during myogenesis. In particular, we show that Mef 2d integrates the p38 MAPK signaling pathway to establish the epigenetic H3K4me3 mark at muscle-specific promoters.

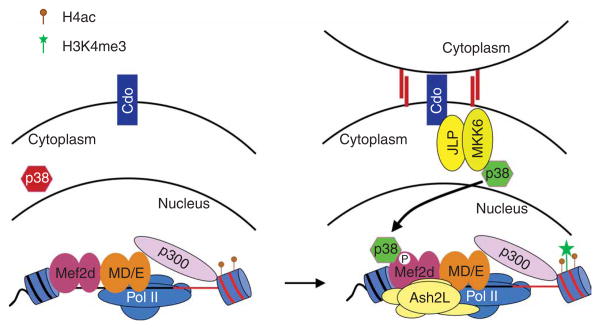

The essential role for the p38 MAPK signaling pathway in myogenesis has been well documented35. Treatment of myoblasts with SB203580 inhibits the formation of myotubes and blocks expression of a subset of muscle-specific genes10–13. Many studies have demonstrated that factors involved in transcriptional regulation in muscle are targets for phosphorylation by p38, including Mef 2a and Mef 2c28 as well as Mef 2d11. Furthermore, phosphorylation of the Mef2 activation domains by p38 has been shown to markedly increase its ability to activate transcription28. Finally, it has been demonstrated that precocious activation of p38 in the presence of Mef 2d leads to altered kinetics of transcription during myogenesis such that ordinarily late-expressing genes are expressed during the early stages of differentiation11. Although these observations have suggested that p38-dependent phosphorylation of Mef 2 proteins might be involved in establishing muscle-specific patterns of gene expression, the function of phosphorylation of the Mef 2 activation domain has not previously been defined. Our study shows that the Ash2L methyltransferase complex is selectively recruited to muscle-specific promoters through p38-dependent phosphorylation of Mef 2d, providing insight into the regulation of muscle-specific transcription by MAPK signaling. On the basis of the results obtained in this study, we propose a model for Mef 2d-dependent activation of muscle-specific genes during myogenesis (Fig. 7). During differentiation, MyoD and Mef2 bind muscle-specific promoters, leading to the recruitment of coactivators (including p300) and the basal transcriptional machinery to establish a transcriptionally poised promoter. Consistent with previous observations31, we detected Pol II and the acetyltransferase p300 at the Myog and Ckm promoters in the absence of p38 activity. This results in a promoter that contains H4ac. Once the muscle-specific genes are poised for transcription, their expression is initiated through activation of the p38 MAPK pathway. Recent studies have suggested that prolonged activation of the p38 MAPK pathway could be mediated through activation of the membrane-bound receptor Cdo as a result of cell-cell contact36. Once activated, p38 can then phosphorylate Mef 2d, thereby permitting the recruitment of the Ash2L complex to muscle-specific promoters, which ultimately would lead to trimethylation of H3K4. Combined with the p38-dependent remodeling of nucleosomes in the promoter region by the ATP-dependent chromatin-remodeling complex SWI/SNF31, the H3K4me3 modification would permit abundant expression of developmentally regulated genes. Notably, our siRNA experiments demonstrate that a decrease in H3K4me3 is matched by an increase in H3K4me2 (Fig. 5c and Supplementary Fig. 6), suggesting that these two modifications exist in a dynamic equilibrium that may allow rapid conversion from a poised promoter to an actively transcribing gene.

Figure 7.

Model for the integration of the p38 MAPK signaling pathway with Mef2-dependent recruitment of the Ash2L complex to muscle-specific promoters. Before activation of p38, MyoD and E47 (MD/E) cooperate with Mef 2d dimers (homo- or heterodimers) to establish a transcriptionally poised promoter through recruitment of the acetyltransferase p300 and Pol II. This leads to acetylation of nucleosomes on histone H4 within the promoter. As differentiation proceeds, cell-cell contact activates the membrane-bound receptor Cdo, leading to p38 MAPK activation via the scaffold protein JLP and the MKK6 kinase36. Once activated, p38 MAPK phosphorylates Mef 2d, leading to targeting of the Ash2L methyltransferase complex to muscle-specific promoters. The methyltransferase complex then establishes the epigenetic H3K4me3 mark required for abundant expression of developmentally regulated genes.

The p38 MAPK pathway has previously been shown to be essential for the recruitment of SWI/SNF to the Myog and Ckm promoters31. This is particularly noteworthy because the catalytic subunits of SWI/SNF (BRM/BRG1) are in the same TrxG family of proteins as Ash2L1,2. Furthermore, it has been shown that Mef 2d cooperates with myogenin to recruit SWI/SNF to the promoter region of the Ckm gene37. In contrast, several studies have suggested that SWI/SNF is recruited to the Myog promoter through an interaction with MyoD31,38 in the absence of Mef 2 (ref. 31). Whereas SWI/SNF seems to be recruited to the Myog and Ckm promoters through different mechanisms, we observed Mef 2d- and p38-dependent recruitment of Ash2L to both Myog and Ckm. Thus, there seems to be some difference in the mechanism by which Ash2L and SWI/SNF are targeted to developmentally regulated genes. However, p38 regulates the recruitment of both these TrxG complexes to specific genes (Fig. 4c and ref. 31). We propose that one of the mechanisms by which p38 promotes myogenesis is through targeting of TrxG proteins to muscle-specific genes to establish tissue-specific expression.

In conclusion, we show here that muscle-specific genes do become epigenetically marked for gene expression during myogenesis. Targeting of the H3K4me3 mark to specific promoters is mediated by the Ash2L methyltransferase complex, which is recruited by the DNA-bound transcriptional activator Mef 2d. Furthermore, we find that this recruitment is regulated through the p38 MAPK–mediated phosphorylation of Mef 2d, which enhances the association between the transactivator and the methyltransferase complex. Thus, our study mechanistically links the p38 MAPK signaling pathway with the activation of muscle-specific genes during myogenesis.

Methods

Antibodies

We used antibodies specific to H3K4me3 (Abcam ab8580), H3K4me2 (Upstate 07-030), H4ac (Upstate 06-866), WDR5 (Abcam ab22512), RbBP5 (Bethyl BL766), Mef 2 (Santa Cruz sc-17785, sc-13917), Mef 2d (BD Biosciences 610774), Set1 (Bethyl A300-289A), MLL (Bethyl A300-087A), MLL2/Trx2 (Bethyl A300-113A), menin (Bethyl A300-105A), Pol II (Santa Cruz sc-17798, sc-9001, sc-5943), p300 (Santa Cruz sc-584), p38 (Santa Cruz sc-7972), p38 phosphorylated on Thr180 and Tyr182 (Cell Signaling 9211S), myogenin (Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank F5D) and Flag (Sigma F-3165). Antibodies to MLL3 and MLL4/ALR have been described27. Antibodies against MyoD, Ash2L, DPY30 were raised in rabbits using purified full-length proteins.

Cell culture

The mouse myoblast cell line C2C12 (ref 17) was maintained at less than 80% confluency in DMEM containing 10% (v/v) FBS, l-glutamine, penicillin and streptomycin. For differentiation studies, cells were washed with PBS when they attained 80% confluence and then incubated in differentiation medium (DMEM containing 2% (v/v) horse serum, 10 μg ml−1 insulin, 10 μg ml−1 transferrin, l-glutamine, penicillin and streptomycin) for 48 h (unless otherwise noted). Control siRNAs or siRNAs targeting Mef 2c, Mef 2d or Ash2l (Ambion) were transfected at a final concentration of 100 nM using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) and transferred to differentiation media immediately. For p38 MAPK inhibition studies, SB203580 was added directly to the differentiation media at a final concentration of 10 μM.

Native chromatin immunoprecipitation

Approximately 1 × 107 C2C12 cells obtained at various stages of differentiation were lysed in buffer A (15 mM Tris (pH 7.5), 15 mM NaCl, 60 mM KCl, 250 mM sucrose, 5 mM MgCl2, 1.5 mM CaCl2, 1 mM DTT and 1 mM PMSF). Nuclei were recovered by centrifugation and quantified by measuring total ribonucleic acid content. Chromatin (15 mg) was digested with 1 U MNase (Sigma) for 10 min at 37 °C to give a maximum visible fragment size of 550 base pairs (three nucleosomes). NaCl was then added to a final concentration of 600 mM, and the nuclei were incubated with 10 mg of hydroxyapatite resin to generate a slurry. After extensive washing, nucleosomes were eluted from the resin with a buffer containing 300 mM NaPO4 (pH 7.2). Eluted nucleosomes were then subjected to immunoprecipitation with either an anti-H3K4me3, anti-H3K4me2 or control rabbit IgG, as described in the figure legends. Immunoprecipitated DNA was purified and subjected to qPCR analysis with hydrolysis probes (see Supplementary Table 1 online for primer and probe sequences). To calculate relative enrichment, we subtracted the signal observed in the control immunoprecipitation experiment from that observed with the specific antibody, then divided the resulting difference by the signal observed from one-fiftieth of the ChIP input material.

Chromatin immunoprecipitation

ChIP assays were done as described39, except that DNA was sonicated using a bioruptor to obtain fragments approximately 400 base pairs in length. Immunoprecipitated DNA was reverse–cross-linked, purified and subjected to qPCR analysis with hydrolysis probes (see Supplementary Table 1 for primer and probe sequences). Relative enrichment was calculated as described for native ChIP studies.

Protein expression

N-terminally Flag-tagged MyoD (FL-MyoD) and C-terminal Flag-tagged Mef 2aα1,β (FL-Mef 2a), Mef 2cα1,β,γ (FL-Mef 2c) and Mef 2dα1,β (FL-MEf 2D) were expressed using baculovirus in Sf 9 cells and purified with anti-Flag M2-agarose beads (Sigma). The phosphorylation-deficient mutant of Mef 2d was generated by mutation of both Thr308 and Thr315 to alanine using the QuikChange system (Stratagene). Activated p38α was purified from a BL-21 strain stably coexpressing His-p38α, MEK4 and MEKK-C29 with nickel–nitrilotriacetic acid (Ni-NTA) resin (Qiagen).

Immunoprecipitation and Flag pull-down assays

Cell extracts were prepared in lysis buffer (50 mM Tris (pH 8.0), 150 mM NaCl, 1% (v/v) Nonidet P-40, 0.1% (w/v) SDS, 0.5% (v/v) sodium deoxycholate and Complete protease inhibitors (GE Healthcare)) from differentiating C2C12 cells at the 48 h time point. Either protein A or protein G Dynabeads were coated with antibodies as described39. Approximately 400 μg of protein lysate were subjected to immunoprecipitation with various antibodies (as indicated in figure legends). Beads were then washed three times with buffer containing 300 mM KCl and 0.1% (v/v) Nonidet P-40, and proteins were eluted in SDS loading dye and then subjected to western blotting.

For Flag pull-down assays, extracts prepared from baculovirus-infected Sf 9 cells expressing recombinant proteins of interest were incubated with Flag M2– Agarose beads for 1 h. The beads were then washed with EX-100 buffer40 to remove unbound proteins. For phosphorylation experiments, protein-bound beads were incubated in the presence of 1 μM ATP with or without p38α kinase for 30 min at 30 °C. After washing to remove ATP and p38α, beads were incubated with 48 h–differentiated C2C12 cell extract. Interacting proteins were eluted in SDS loading dye and subjected to western blotting with indicated antibodies.

Reverse-transcription PCR assays

Total RNA (3 μg) was reverse-transcribed with MuMLV reverse transcriptase. The resulting random primed complementary DNA was subjected to semiquantitative RT-PCR with gene-specific primers (see Supplementary Table 1 for primer sequences) for Myog, Ckm, Cdkn1a, Acta1, Mef 2a, Mef 2c, Mef 2d and Actb (encoding β-actin). For quantitative RT-PCR (qRT-PCR), duplex reactions were performed using 6-fluorescein phosphoramidite (FAM)-labeled and 3′ black hole quencher-1 (BHQ)-labeled gene-specific primers (see Supplementary Table 1 for primer sequences) and 5′ yakima yellow (YY)-labeled and 3′ eclipse dark quencher (EDQ)-labeled primers specific for 18S ribosomal RNA (Eurogentec).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, the Muscular Dystrophy Association and the Stem Cell Network (to F.J.D.), from the US National Institutes of Health (to S.J.T.) and from the Terry Fox Foundation of the National Cancer Institute of Canada and the Human Frontiers Science Program (to M.B.). F.J.D. holds a Canadian Research Chair in Epigenetic Regulation of Transcription.

Footnotes

Note: Supplementary information is available on the Nature Structural & Molecular Biology website.

Author Contributions: S.R. and F.J.D. conceived and designed the experiments. S.R. was responsible for all ChIP, immunoprecipitation, RT-PCR and interaction studies. F.J.D. and M.B. generated the polyclonal antibody to full-length Ash2L. L.L. generated the polyclonal antibodies to full-length DPY and MyoD. E.M. generated the Mef2D mutant. S.R. and E.M. performed the transfection studies with the Mef 2 mutants. K.G. provided antibodies to MLL3 and MLL4. S.R., M.B., S.J.T. and F.J.D. provided scientific direction of the project. F.J.D. wrote the paper. S.R., M.B. and F.J.D. discussed and commented on the manuscript.

References

- 1.Ringrose L, Paro R. Epigenetic regulation of cellular memory by the polycomb and trithorax group proteins. Annu Rev Genet. 2004;38:413–443. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.38.072902.091907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brock HW, Fisher CL. Maintenance of gene expression patterns. Dev Dyn. 2005;232:633–655. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.20298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ruthenburg AJ, Allis CD, Wysocka J. Methylation of lysine 4 on histone H3: intricacy of writing and reading a single epigenetic mark. Mol Cell. 2007;25:15–30. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bernstein BE, et al. Genomic maps and comparative analysis of histone modifications in human and mouse. Cell. 2005;120:169–181. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Martens JH, et al. The profile of repeat-associated histone lysine methylation states in the mouse epigenome. EMBO J. 2005;24:800–812. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Papp B, Muller J. Histone trimethylation and the maintenance of transcriptional ON and OFF states by trxG and PcG proteins. Genes Dev. 2006;20:2041–2054. doi: 10.1101/gad.388706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Breen TR, Harte PJ. Molecular characterization of the trithorax gene, a positive regulator of homeotic gene expression. Drosophila Mech Dev. 1991;35:113–127. doi: 10.1016/0925-4773(91)90062-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Klymenko T, Muller J. The histone methyltransferases Trithorax and Ash1 prevent transcriptional silencing by Polycomb group proteins. EMBO Rep. 2004;5:373–377. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.7400111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Molkentin JD, Black BL, Martin JF, Olson EN. Cooperative activation of muscle gene expression by MEf 2 and myogenic bHLH proteins. Cell. 1995;83:1125–1136. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90139-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bergstrom DA, et al. Promoter-specific regulation of MyoD binding and signal transduction cooperate to pattern gene expression. Mol Cell. 2002;9:587–600. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(02)00481-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Penn BH, Bergstrom DA, Dilworth FJ, Bengal E, Tapscott SJA. MyoD-generated feed forward circuit temporally patterns gene expression during skeletal muscle differentiation. Genes Dev. 2004;18:2348–2353. doi: 10.1101/gad.1234304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wu Z, et al. p38 and extracellular signal-regulated kinases regulate the myogenic program at multiple steps. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:3951–3964. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.11.3951-3964.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zetser A, Gredinger E, Bengal E. p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway promotes skeletal muscle differentiation Participation of the Mef 2c transcription factor. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:5193–5200. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.8.5193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Caretti G, Di Padova M, Micales B, Lyons GE, Sartorelli V. The Polycomb Ezh2 methyltransferase regulates muscle gene expression and skeletal muscle differentiation. Genes Dev. 2004;18:2627–2638. doi: 10.1101/gad.1241904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhang CL, McKinsey TA, Olson EN. Association of class II histone deacetylases with heterochromatin protein 1: potential role for histone methylation in control of muscle differentiation. Mol Cell Biol. 2002;22:7302–7312. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.20.7302-7312.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Guenther MG, Levine SS, Boyer LA, Jaenisch R, Young RA. A chromatin landmark and transcription initiation at most promoters in human cells. Cell. 2007;130:77–88. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.05.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yaffe D, Saxel O. Serial passaging and differentiation of myogenic cells isolated from dystrophic mouse muscle. Nature. 1977;270:725–727. doi: 10.1038/270725a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Milne TA, et al. MLL associates specifically with a subset of transcriptionally active target genes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:14765–14770. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0503630102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Steward MM, et al. Molecular regulation of H3K4 trimethylation by ASH2L, a shared subunit of MLL complexes. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2006;13:852–854. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dou Y, et al. Regulation of MLL1 H3K4 methyltransferase activity by its core components. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2006;13:713–719. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang J, et al. ASH2L: alternative splicing and downregulation during induced megakaryocytic differentiation of multipotential leukemia cell lines. J Mol Med. 2001;79:399–405. doi: 10.1007/s001090100222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cheng TC, Wallace MC, Merlie JP, Olson EN. Separable regulatory elements governing myogenin transcription in mouse embryogenesis. Science. 1993;261:215–218. doi: 10.1126/science.8392225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yee SP, Rigby PW. The regulation of myogenin gene expression during the embryonic development of the mouse. Genes Dev. 1993;7:1277–1289. doi: 10.1101/gad.7.7a.1277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Edmondson DG, Cheng TC, Cserjesi P, Chakraborty T, Olson EN. Analysis of the myogenin promoter reveals an indirect pathway for positive autoregulation mediated by the muscle-specific enhancer factor MEF-2. Mol Cell Biol. 1992;12:3665–3677. doi: 10.1128/mcb.12.9.3665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Malik S, Huang CF, Schmidt J. The role of the CANNTG promoter element (E box) and the myocyte-enhancer-binding-factor-2 (MEF-2) site in the transcriptional regulation of the chick myogenin gene. Eur J Biochem. 1995;230:88–96. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1995.tb20537.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Berkes CA, et al. Pbx marks genes for activation by MyoD indicating a role for a homeodomain protein in establishing myogenic potential. Mol Cell. 2004;14:465–477. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(04)00260-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cho YW, et al. PTIP associates with MLL3- and MLL4-containing histone H3 lysine 4 methyltransferase complex. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:20395–20406. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M701574200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhao M, et al. Regulation of the MEf 2 family of transcription factors by p38. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:21–30. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.1.21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Khokhlatchev A, et al. Reconstitution of mitogen-activated protein kinase phosphorylation cascades in bacteria. Efficient synthesis of active protein kinases. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:11057–11062. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.17.11057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhu B, Ramachandran B, Gulick T. Alternative pre-mRNA splicing governs expression of a conserved acidic transactivation domain in myocyte enhancer factor 2 factors of striated muscle and brain. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:28749–28760. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M502491200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Simone C, et al. p38 pathway targets SWI-SNF chromatin-remodeling complex to muscle-specific loci. Nat Genet. 2004;36:738–743. doi: 10.1038/ng1378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ernst P, Wang J, Huang M, Goodman RH, Korsmeyer SJ. MLL and CREB bind cooperatively to the nuclear coactivator CREB-binding protein. Mol Cell Biol. 2001;21:2249–2258. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.7.2249-2258.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Voo KS, Carlone DL, Jacobsen BM, Flodin A, Skalnik DG. Cloning of a mammalian transcriptional activator that binds unmethylated CpG motifs and shares a CXXC domain with DNA methyltransferase, human trithorax, and methyl-CpG binding domain protein 1. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:2108–2121. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.6.2108-2121.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wysocka J, et al. WDR5 associates with histone H3 methylated at K4 and is essential for H3 K4 methylation and vertebrate development. Cell. 2005;121:859–872. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.03.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lluis F, Perdiguero E, Nebreda AR, Munoz-Canoves P. Regulation of skeletal muscle gene expression by p38 MAP kinases. Trends Cell Biol. 2006;16:36–44. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2005.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Takaesu G, et al. Activation of p38α/β MAPK in myogenesis via binding of the scaffold protein JLP to the cell surface protein Cdo. J Cell Biol. 2006;175:383–388. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200608031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ohkawa Y, Marfella CG, Imbalzano AN. Skeletal muscle specification by myogenin and Mef 2D via the SWI/SNF ATPase Brg1. EMBO J. 2006;25:490–501. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.de la Serna IL, et al. MyoD targets chromatin remodeling complexes to the myogenin locus prior to forming a stable DNA-bound complex. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25:3997–4009. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.10.3997-4009.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Brand M, et al. Dynamic changes in transcription factor complexes during erythroid differentiation revealed by quantitative proteomics. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2004;11:73–80. doi: 10.1038/nsmb713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dilworth FJ, Ramain-Fromental C, Yamamoto K, Chambon P. ATP-driven chromatin remodeling activity and histone acetyltransferases act sequencially during transactivation by RAR/RXR in vitro. Mol Cell. 2000;6:1049–1058. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)00103-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.