Abstract

Group B coxsackieviruses (CVB) utilize the coxsackievirus-adenovirus receptor (CAR) to recognize host cells. CAR is a membrane protein with two Ig-like extracellular domains (D1 and D2), a transmembrane domain and a cytoplasmic domain. The three-dimensional structure of coxsackievirus B3 (CVB3) in complex with full length human CAR and also with the D1D2 fragment of CAR were determined to ~22 Å resolution using cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM). Pairs of transmembrane domains of CAR associate with each other in a detergent cloud that mimics a cellular plasma membrane. This is the first view of a virus–receptor interaction at this resolution that includes the transmembrane and cytoplasmic portion of the receptor. CAR binds with the distal end of domain D1 in the canyon of CVB3, similar to how other receptor molecules bind to entero- and rhinoviruses. The previously described interface of CAR with the adenovirus knob protein utilizes a side surface of D1.

Coxsackieviruses are small, nonenveloped, positive-strand RNA viruses that belong to the Enterovirus genus of Picornaviridae1,2. Coxsackievirus infection can cause myocarditis, meningoencephalitis and inflammation of the pancreas in humans and many other hosts2. The crystal structure of coxsackievirus B3 (CVB3) shows that it has surface features similar to other entero- and rhinoviruses3. Coxsackievirus capsids have 60 copies each of four viral proteins, VP1, VP2, VP3 and VP4, which form an icosahedral shell with an ~300 Å external diameter that encapsidates an ~7.5 kilobase (kb) RNA genome. The six coxsackie B virus serotypes (CVB1–CVB6) and many adenoviruses share a common receptor on human cells, the coxsackievirus-adenovirus receptor (CAR)4–7. Because these two virus families are unrelated, their receptor specificity must have evolved independently.

A prominent feature of the capsid surface in entero- and rhinoviruses is a narrow depression around each of the five-fold axes termed the ‘canyon’, which had been predicted to be the receptor binding site for picornaviruses8. This was confirmed by cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM) for human rhinoviruses 14 and 16 (HRV14 and HRV16) in complex with intracellular adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1 or CD54)9,10, poliovirus (Mahoney) in complex with poliovirus receptor (PVR or CD155)11–13 and coxsackievirus A21 in complex with ICAM-1 (ref. 14). Conservation of receptor binding within the canyon, in spite of the evolutionary divergence of these viruses, suggests that such a binding site provides an evolutionary advantage. The binding site in the canyon has been suggested to be protected from immune surveillance by being less accessible to relatively large antibodies8. Furthermore, this site may also be required to trigger uncoating during viral entry15,16. Nevertheless, these suggestions have been challenged because the footprint of at least one neutralizing antibody was found to extend into the canyon17.

CAR is a 46 kDa membrane glycoprotein with two Ig-like extracellular domains (D1 and D2), a transmembrane domain and a 107-amino acid cytoplasmic domain5–7. CAR is expressed in many tissues and is highly conserved between mice and humans. It may have a cell adhesion function18, but its precise physiological role remains unclear. The roles of CAR in CVB and adenovirus infection are different. For CVBs, CAR can function for both attachment and infection7. For adenoviruses, however, the major function of CAR is to mediate initial attachment of virus to the cell surface, whereas subsequent entry of virus into cells is mediated by integrin coreceptors19,20. To further understand the role of CAR in CVB infection, we determined the structure of CVB3 bound to detergent extracted, full length CAR and to recombinant fragments of the CAR ectodomain. The mode of CAR binding into the viral canyon was the same in every case, demonstrating the importance of the virus–receptor interaction and the critical nature of the canyon binding site in the initiation of infection.

CVB3–CAR complexes

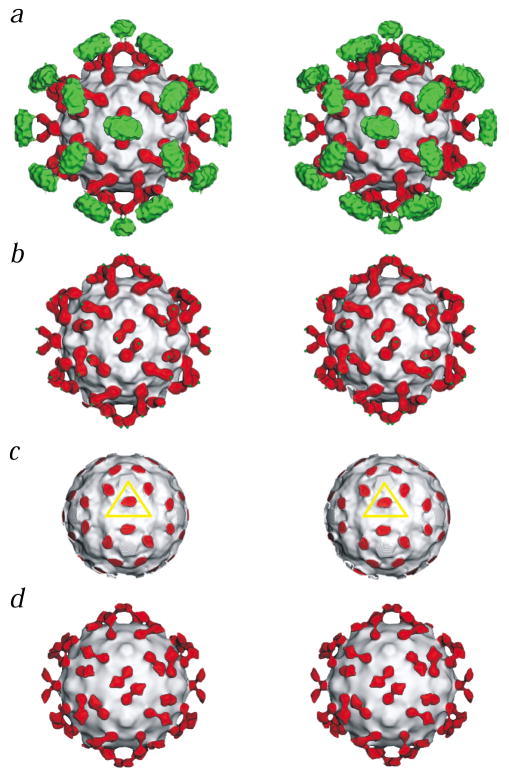

Reconstructions were computed of images of CVB3 in complex with either full length human CAR (Fig. 1a), with the ectodomain (D1D2) of human CAR (Fig. 1d) or with the D1 domain alone. Full length human CAR was extracted from mouse cells expressing CAR from multiple copies of the transfected human CAR gene. The mouse A9 cell line does not express detectable levels of mouse CAR (data not shown). Cryo-EM reconstructions showed that this form of the protein completely saturated binding sites on CVB3 capsids. A cDNA fragment encoding the entire CAR ectodomain (D1D2) was cloned into a VSV-based expression vector and then expressed in infected BHK cells. Although the resultant D1D2 fragment was able to bind strongly to adenovirus knob protein, showing it to be biologically active, cryo-EM reconstructions showed only partial saturation of binding sites on the CVB3 capsids. The D1 fragment of CAR was expressed in Escherichia coli, and its structure bound to adenovirus knob protein has been determined21. Nevertheless, cryo-EM reconstructions did not show any detectable binding of the D1 domain fragment to CVB3. In parallel with the cryo-EM experiments, interaction of the three different forms of CAR protein with CVB3 was monitored by plaque reduction assays. Consistent with the results of the cryo-EM reconstructions, the efficiency of plaque inhibition by the three forms of CAR protein varied in the order: full length CAR > D1D2 > D1. Because the N-terminus of CAR D1 participates in the interaction with CVB3, the different N-terminal sequences resulting from the various expression systems may have contributed to the variation in plaque reduction assays and cryo-EM results.

Fig. 1.

Stereo views of CAR bound to CVB3. The virus in each panel is represented as a grayscale surface. Domains D1 and D2 of CAR are colored red, and the transmembrane and cytoplasmic regions are green. a, CVB3 complexed with the full length CAR. b, Same as (a) but with density outside a radius of 200 Å removed to show domains D1 and D2 of CAR only (green dots indicate where the transmembrane regions start). c, Same as (a) but with density removed outside a radius of 154 Å to show the binding site of D1 in the CVB3 canyon. The yellow triangle defines the icosahedral asymmetric unit. d, The complex of CVB3 with the CAR D1D2 fragment.

The cryo-EM reconstruction of CVB3 in complex with full length CAR (Fig. 1) showed domain D1 bound into the canyon of CVB3, domain D2 making an angle of ~125° with the long axis of domain D1 and a large density feature corresponding to the transmembrane and cytoplasmic region. The size of this feature suggests that it may be associated with the Nonidet P40 (NP40) nonionic detergent present in the solution used for the extraction and purification of CAR. The transmembrane and cytoplasmic domains within the large density feature cannot be differentiated. The electron density between D2 and this large density region is lower than the density of the hinge between D1 and D2. This suggests the hinge between D2 and the transmembrane domain is more flexible or longer than the hinge between D1 and D2.

Adjacent CAR molecules, related by icosahedral two-fold axes, share common density in the external transmembrane and cytoplasmic regions. This association of the adjacent receptors might stabilize the complex or increase the possibility of forming saturated complexes. Hence, bivalent CAR might bind to CVB3 capsids with higher avidity than the monovalent D1 and D1D2 fragments, and this could account for the more potent plaque reduction activity of intact CAR protein. The large density feature may mimic a cellular membrane-like structure induced by the presence of the NP40 detergent. Therefore, the observed cryo-EM structure may represent the initial complex formation prior to the internalization of CVB3 into a cell.

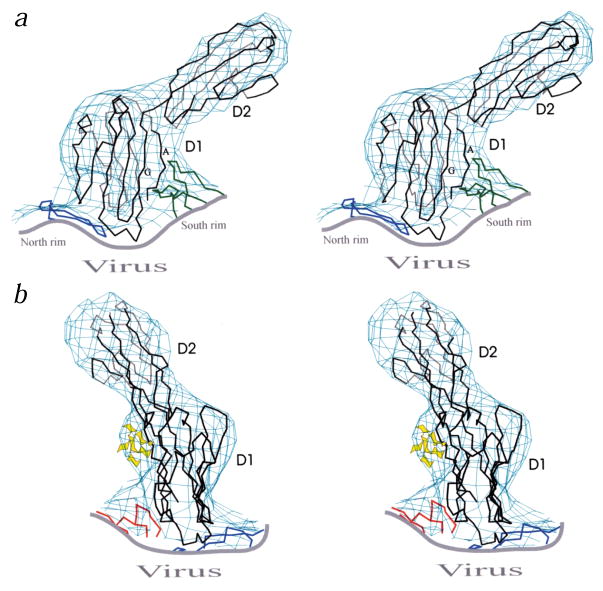

The D1 and D2 domains of CAR each has one potential N-glycosylation site. The site at Asn 108 contributes a small density protrusion on one side of the cryoEM density of domain D1. This density feature together with the asymmetric shape of domain D1 itself allows the structure of CAR D1 to be fit reliably (Fig. 2). The fit shows that the interface between the virus and the receptor consists of the distal end of CAR bound to the north rim and the floor of the canyon, as well as the A and G β-strands (Fig. 3 for nomenclature) bound to the south rim of the canyon. The EM density of D2 is in the shape of a cylinder and leads to a more uncertain fit of the homologous model. However, the requirement that the C-terminus of D1 must connect with the N-terminus of D2 provides some restraints on the fit of D2 into the EM density.

Fig. 2.

Orthogonal stereo views of the Cα backbone of CAR D1 and D2 (black) fit into the cryo-EM density. Fragments of CVB3 (blue for VP1, green for VP2 and red for VP3) are also shown. a, The south rim of the canyon, formed by VP2, contacts the A and G β-strands of domain D1. b, The sugar moieties of the carbohydrate at Asn 108 are depicted in yellow.

Fig. 3.

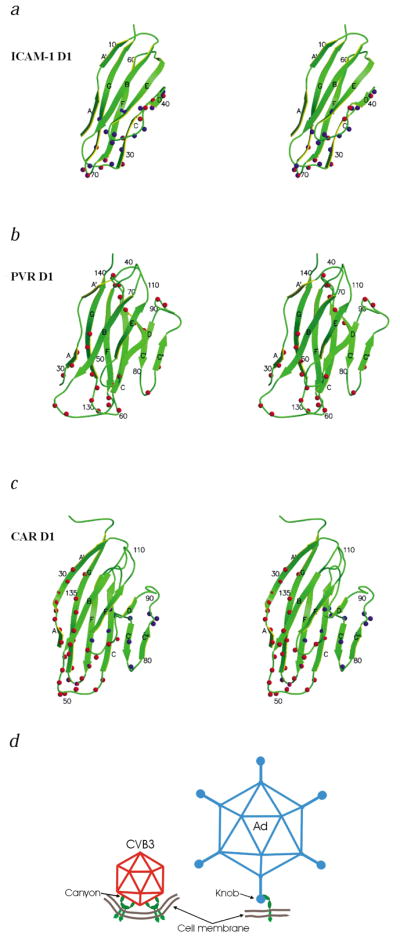

Stereo diagrams of the ICAM-1, PVR and CAR D1 domains. The β-strands are labeled A–G. The amino acids identified as being in the virus–receptor interface are indicated by spheres. a, ICAM-1 with HRV14 and HRV16 in blue, and ICAM-1 with coxsackievirus A21 in red; b, PVR with poliovirus in red; and c, CAR with adenovirus knob in blue and CAR with CVB3 in red. d, Schematic diagram of the modes by which CAR (green) binds to CVB3 (red) and adenovirus19 (blue). The suggested membrane curvature is speculative.

Although the cryo-EM density for CVB3 in complex with full length CAR shows greater saturation than that for the complex with CAR D1D2 fragment, the electron density distribution corresponding to D1 and D2 is very similar in both reconstructions (Fig. 1). Thus, the transmembrane and cytoplasmic association does not alter the way domain D1 binds to the virus. The reproducibility with which different samples of CAR bind to CVB3, or with which ICAM-1 binds to different HRV serotypes, contrasts with the quite different binding orientation of specific receptors, such as CAR, PVR, and ICAM-1, make with their corresponding viruses. Thus, the consistency for CAR binding suggests that all other receptor-virus studies are relevant when the receptors are anchored in the plasma membrane.

Interaction with picornaviruses

The CAR binding region in the CVB3 canyon is similar to the receptor binding region of other picornaviruses9,11–14. The binding region of receptors is mostly the distal end of domain D1, although in poliovirus it also includes the side of D1 composed of the C, C′ and C″ β-strands (Fig. 3). The orientation of D1 is approximately radial in all cases except for poliovirus. The canyon of poliovirus is wider than that of CVB3 and the HRVs, allowing the tangential binding of PVR into the poliovirus canyon. Therefore, the shape and size of the canyon may be important factors that dictate the docking orientation of the receptors.

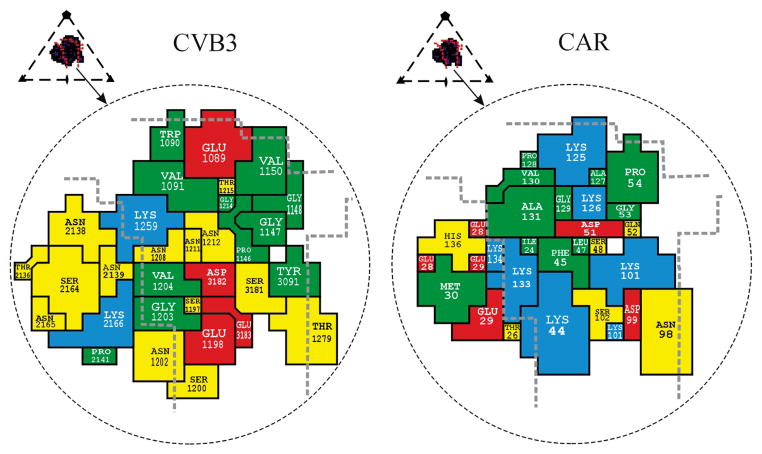

All of the external viral proteins (VP1, VP2 and VP3) participate in receptor binding, but the majority of the interactions with CAR are with VP1 (Fig. 4). Several charged residues line the binding interface and make complementary interactions with CAR. These residues in the virus–receptor interface are moderately well conserved among the six CVB serotypes as well as in swine vesicular disease virus (SVDV), a picornavirus that also uses CAR as its cellular receptor7. The mutation N2165D (residues in VP1, VP2, VP3 and VP4 of picornaviruses are numbered starting with 1000, 2000, 3000 and 4000, respectively) of a CVB3 variant22 attenuates the myocarditic phenotype. This mutation is adjacent to Lys 2166 and might influence the electrostatic interaction between the virus and Glu 28 or Glu 29 of CAR. Both human and mouse CAR can bind to CVBs. Amino acids of human CAR identified in the CVB3 interface (Fig. 4) are almost completely conserved in mouse CAR23.

Fig. 4.

Footprint of domain D1 onto the CVB3 surface (left) and footprint of CVB3 onto CAR (right). Inset shows the icosahedral asymmetric unit of the virus, the rough boundaries of the canyon (red lines) and the perimeter of the receptor footprint. The amino acids forming the interface are colored as follows: red for acidic residues, blue for basic residues, yellow for polar residues and green for hydrophobic residues. Thick dashed gray lines highlight the canyon boundaries. The CAR amino acids are numbered in accordance with the system used by Bewley et al.21 (PDB 1KAC); these sequence numbers are greater by two than those used by van Raaij et al.24 (PDB 1F5W).

Comparison with adenovirus interaction

CAR uses the distal end and the A-G side of D1 for binding to CVB3, whereas it utilizes the C, C′ and C″ strands and the FG loop on the other side of D1 for binding to adenoviruses19,21 (Fig. 3). The overlapping binding region of CVB3 and adenovirus on CAR is located at the beginning of strand C and the FG loop, accounting for the competitive binding of these viruses to HeLa cells4. The way CAR is utilized for attachment and subsequent processes for cellular infection is different for these two types of viruses (Fig. 3d). D1 of CAR has been shown to form a homodimer during crystallization24. The residues that form the interface between the monomers in the homodimer also form the interface with the D1–adenovirus knob protein. Apparently, the CAR residues in this interface make a nonspecific sticky surface. This surface, surprisingly, is not involved in the CAR–CVB3 interaction and might suggest that there is an especially strong adhesion of CAR to CVB3.

The interaction of receptor with entero- and rhinoviruses has been proposed to cause the release of a ‘pocket factor’ bound to VP1 and, hence, the destabilization of the viruses, thereby allowing the viruses to uncoat after cell entry15,16. The conservation of the binding site for Ig-like, cell surface receptor molecules in the canyon of entero- and rhinoviruses, as suggested by the canyon hypothesis8, might be required for protection of this site from the immune system of the host, as well as for providing a suitable trigger for virus uncoating.

Methods

Virus and CAR purification

CVB3 (strain M)25 was produced in HeLa cells and was purified by sedimentation through a 30% (w/v) sucrose cushion and then through a 10–40% (w/v) potassium tartrate gradient3. Full length human CAR protein was isolated from a mouse cell line that was stably transfected with a bacterial artificial chromosome (BAC) containing the human CAR gene (GenBank accession AF200465)26,27. A selected clone was grown in Dulbecco’s MEM supplemented with 10% (v/v) calf serum and 0.4 mg ml−1 G418-resistant cells. Cells were harvested and lysed in PBS containing 1% (v/v) Triton X-100. After low speed centrifugation, the cleared lysate was applied to a column of adenovirus 12 knob protein27 immobilized on CNBr-activated Sepharose beads. The column was washed with PBS containing 0.05% (v/v) NP40 and eluted with 0.25 M glycine buffer, pH 2.8, containing 0.05% NP40. Fractions containing CAR protein were dialyzed against PBS containing 0.05% NP40.

A cDNA fragment encoding the entire CAR ectodomain (D1D2) was cloned into a vesicular stomatis virus (VSV)-based expression vector. In this vector, CAR D1D2 cDNA was substituted for the VSV G protein and flanked by the signals that regulate transcription of the VSV G protein. In addition, the natural CAR signal peptide was deleted and replaced by the VSV G protein signal peptide, which increased secretion of CAR D1D2. Recovery of the ΔG-D1D2 recombinant VSV virus and preparation of virus stocks from cells transiently expressing VSV G protein were performed as described28. To produce CAR D1D2 protein, BHK cells were infected with the VSV G-complemented recombinant virus and maintained at 37 °C in serum-free medium for 16 h. CAR D1D2 accumulated to ~5 μg ml−1 in the culture supernatant. Protein was purified by affinity chromatography as described above. CAR D1 was expressed in E. coli as described27.

Plaque reduction

Monolayers of HeLa cells were grown in 60 mm culture dishes. CVB3 inoculum (1 × 108 PFU ml−1) was diluted in PBSA (PBS plus 0.1% (w/v) bovine serum albumin). Samples of full length CAR or CAR fragments were added to the diluted virus and incubated in microcentrifuge tubes for 2 h at room temperature. Media was aspirated from each dish and monolayers were infected with 0.2 ml of diluted virus. Virus was allowed to attach to the cells for 30 min at room temperature. Cultures were then fed with media containing 0.8% (w/v) agar and incubated at 37 °C for 24 h. Agar overlays were then removed, and cells were stained with crystal violet dye to visualize plaques (results not shown).

Cryo-EM reconstruction

The CAR samples were incubated with CVB3 at room temperature with a ratio of three to four CAR molecules per virus binding site. Small aliquots (~3.5 μl) of this mixture were applied to carbon-coated electron microscope (EM) grids and vitrified in liquid ethane as described by Baker et al.29 Control samples of CVB3 by itself were prepared similarly. Electron micrographs were recorded on Kodak SO-163 film using a Philips CM300 FEG microscope and were digitized with a Zeiss PHODIS microdensitometer at 14 μm intervals.

A cryo-EM reconstruction of HRV16 was used as an initial model for determining particle orientations and centers by means of the polar fourier transform method29,30. Corrections to compensate for the effects of the microscope contrast function were applied in the reconstruction procedure. The resolution of the resultant three-dimensional image reconstructions (Table 1) was estimated by splitting the image data into two sets and comparing the structure factors obtained in separate reconstructions. The reconstruction of the native CVB3 structure was in agreement with an electron density map generated from the X-ray crystallographically determined atomic structure of CVB3.

Table 1.

Statistics of the cryo-EM reconstructions

| CVB3–full length CAR complex | CVB3–D1D2 complex | CVB3 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of micrographs | 26 | 18 | 9 |

| Incubation time (min) | 45 | 110 | – |

| Defocus1 (μm) | 1.5–4.6 | 1.9–4.8 | 2.2–5.4 |

| Magnification | 61,000 | 45,000 | 61,000 |

| Dose (e− Å−2) | 21.6 | 17.3 | 15.5 |

| Number of particles | |||

| Selected | 635 | 1,110 | 297 |

| Total | 1,565 | 2,637 | 997 |

| Correlation coefficient2 | 0.386 | 0.441 | 0.491 |

| Resolution3 (Å) | 22 | 25 | 22 |

Determined from phase contrast transfer function of the microscope.

Real-space correlation coefficient (CC) for selected particles, CC = Σ ((rρi)(rρm) − <rρi><rρm>)/(Σ((rρi)2 − <rρi>2)Σ((rρm)2 − <rρm>2))1/2, where ρi is the electron density of the boxed cryo-EM image, ρm is the electron density of the model projection and r is the radius of the corresponding density point, which assures proper weighting of the densities. The angle brackets indicate mean values.

Resolution at which the correlation between two independent three-dimensional reconstructions falls below 0.5.

Model fitting

The crystal structures of CVB3 and of CAR D1 are available in the Protein Data Bank (PDB accession numbers 1COV for CVB3, and 1KAC and 1F5W for CAR D1). The structure of D2 was approximated by homologous modeling using the crystal structure of neural cell adhesion molecule (PDB accession number 1CS6)31, which has a 23% sequence identity with CAR D2. The model fitting of CAR into the difference map between the complex of CVB3 with CAR and native CVB3 was performed by manual fitting using the program O32 and also with the real-space model fitting program, EMfit33. The cryo-EM density suggested two possible positions of the carbohydrate moiety on CAR D1, resulting in two different orientations, related by an ~180° rotation around the long axis of D1. These orientations were differentiated by requiring that the carboxyl end of D1 must be close to the N-terminus of D2. The r.m.s. difference between equivalent Cα atoms of the hand-fit structure and the program-fit structure was 3.4 Å. Residues in the CAR–CVB3 interface were identified as those that had any atoms of CAR <4 Å from any atoms of CVB3.

Coordinates

The coordinates of the CAR molecule fitted into the cryoEM density of the CVB3–CAR complex have been deposited with the Protein Data Bank (accession number 1JEW).

Acknowledgments

We thank J. DeGregori at the University of Colorado Cancer Center for the hybridoma cells that we initially used to produce CAR. We thank the BNL genome sequencing group, especially B. Lade, L. Butler, K. Pellechi, J. Kieleczawa and J. Dunn, for sequence analysis of the BAC containing the CAR gene. DNA sequencing was supported in part by the Office of Biological and Environmental Research of the U.S. Department of Energy. We also thank C. Xiao, W. Zhang, S. Mukhopadhyay, B. Hébert and J. Henderson for helpful discussions, C. Towell and S. Wilder for help in preparation of the manuscript, and K. Springer for purification of the CAR D1D2 protein fragment. This work was supported by NIH grants to M.G.R., R.J.K., P.F., M.A.W. and T.S.B., and grants from the Keck Foundation and Purdue University.

References

- 1.Rueckert RR. In: Fields virology. Fields BN, Knipe DM, Howley PM, editors. Lippincott-Raven Press; Philadelphia & New York: 1996. pp. 609–654. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Melnick JL. In: Fields virology. Fields BN, Knipe DM, Howley PM, editors. Lippincott-Raven Publishers; Philadelphia & New York: 1996. pp. 655–712. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Muckelbauer JK, et al. Structure. 1995;3:653–668. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(01)00201-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lonberg-Holm K, Crowell RL, Philipson L. Nature. 1976;259:679–681. doi: 10.1038/259679a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bergelson JM, et al. Science. 1997;275:1320–1323. doi: 10.1126/science.275.5304.1320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang X, Bergelson JM. J Virol. 1999;73:2559–2562. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.3.2559-2562.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Martino TA, et al. Virology. 2000;271:99–108. doi: 10.1006/viro.2000.0324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rossmann MG, et al. Nature. 1985;317:145–153. doi: 10.1038/317145a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kolatkar PR, et al. EMBO J. 1999;18:6249–6259. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.22.6249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Olson NH, et al. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:507–511. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.2.507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.He Y, et al. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:79–84. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Belnap DM, et al. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:73–78. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.1.73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Xing L, et al. EMBO J. 2000;19:1207–1216. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.6.1207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Xiao C, et al. J Virol. 2001;75:2444–2451. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.5.2444-2451.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rossmann MG. Protein Sci. 1994;3:1712–1725. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560031010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Oliveira MA, et al. Structure. 1993;1:51–68. doi: 10.1016/0969-2126(93)90008-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Smith TJ, Chase ES, Schmidt TJ, Olson NH, Baker TS. Nature. 1996;383:350–354. doi: 10.1038/383350a0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tomko RP, Xu R, Philipson L. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:3352–3356. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.7.3352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nemerow GR. Virology. 2000;274:1–4. doi: 10.1006/viro.2000.0468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bai M, Harfe B, Freimuth P. J Virol. 1993;67:5198–5205. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.9.5198-5205.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bewley M, Springer K, Zhang YB, Freimuth P, Flanagan JM. Science. 1999;286:1579–1583. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5444.1579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Knowlton KU, Jeon ES, Berkley N, Wessely R, Huber S. J Virol. 1996;70:7811–7818. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.11.7811-7818.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bergelson JM, et al. J Virol. 1998;72:415–419. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.1.415-419.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.van Raaij MJ, Chouin E, van der Zandt H, Bergelson JM, Cusack S. Structure. 2000;8:1147–1155. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(00)00528-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gauntt CJ, Trousdale MD, LaBadie DR, Paque RE, Nealon T. J Med Virol. 1979;3:207–220. doi: 10.1002/jmv.1890030307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mayr GA, Freimuth P. J Virol. 1997;71:412–418. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.1.412-418.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Freimuth P, et al. J Virol. 1999;73:1392–1398. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.2.1392-1398.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Robison CS, Whitt MA. J Virol. 2000;74:2239–2246. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.5.2239-2246.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Baker TS, Olson NH, Fuller SD. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 1999;63:862–922. doi: 10.1128/mmbr.63.4.862-922.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Baker TS, Cheng RH. J Struct Biol. 1996;116:120–130. doi: 10.1006/jsbi.1996.0020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Freigang J, et al. Cell. 2000;101:425–433. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80852-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jones TA, Zou JY, Cowan SW, Kjeldgaard M. Acta Crystallogr A. 1991;47:110–119. doi: 10.1107/s0108767390010224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rossmann MG. Acta Crystallogr D. 2000;56:1341–1349. doi: 10.1107/s0907444900009562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]