Abstract

The endogenous opioid system is centrally involved in short-term placebo analgesic effects, but its potential regulation of memory and learning circuits, critical for the sustainability of placebo responses, has not been explored. Here we examined the recall of analgesic effects after placebo administration as a function of its initial capacity to activate μ-opioid neurotransmission. Memories of therapeutic/adverse responses 24 hours after placebo administration were associated with differences in μ-opioid neurotransmission in the Papez circuit, VTA, amygdala and septum. These data suggests that μ-opioid neurotransmission is involved in the recall of therapeutic benefit, providing a framework to understand stimulus learning and long-term therapeutic effect associations.

Keywords: placebo, analgesia, μ-opioid receptor, recall, memory

Learning motivated behaviors seem critical for the development (1) and presumably, sustainability of placebo responses. However, the neurobiology of long-term forms of placebo responses in humans is largely unexplored. A body of literature has implicated dopaminergic neurotransmission in both, placebo responses (2, 3) and learning motivated behaviors (4). However, the contribution of other placebo related neurotransmitter systems, such as the endogenous opioid, to learning in a motivational context,has not been studied in humans. In vitro studies on neurons in the hippocampus have shown that μ-opioid receptor agonists facilitate long term potentation by increasing excitability of hippocampal pyramidal and dentate granule cells (5) and enkephalins have been involved in the attenuation of amnesia (6).

A network of regions, including the rostral anterior cingulate, dorsolateral prefrontal (DLPFC) and orbitofrontal cortices, insula, ventral striatum, amygdala, medial thalamus and periaqueductal gray (PAG) are involved in acute placebo analgesia (2). These brain areas partly overlap and demonstrate substantial connectivity with traditional memory and cognitive circuits such as the cortico-limbic pathway, the Papez circuit or the septo-hippocampal pathway (7), where high concentrations of μ-opioid receptors have also been described (8).

Here we examined the relationships between measures of regional μ-opioid system activation using positron emission tomography (PET) and the μ-opioid receptor selective radiotracer [11C]carfentanil during a constant sustained pain challenge with and without placebo administration,as previously described (2),and the recall of analgesic effects 24 hours later. It was hypothesized that in addition to already described acute placebo-responsive regions (2), the recall of placebo analgesia would induced the activation of the μ-opioid system in cognitive regions engaged during placebo administration, providing a framework for the understanding of neurocircuitry of long-term forms of placebo response.

For this purpose subjects were asked to recall their pain experience by completing the McGill Pain Questionnaire (MPQ) in a phone interview 24 hours after completion of the scanning protocols (pain and pain + placebo scans). Subjects were considered placebo recall responders when MPQ scores 24 hours after the pain + placebo scans were lower than during the scans when pain alone was introduced (n=18); and placebo recall non-responders when MPQ scores 24 hours after the pain + placebo studies were the same or greater than during the studies where pain alone was introduced (n=19). A mixed model was applied on a voxel by voxel basis using SMP5, with placebo responders/non-responders recall groups as the between subject factor and μ-opioid system activation during placebo administration as the dependent variable using a threshold of p<0.001, with an extent >80 mm3 for regions previously implicated in placebo effects. For hypothesized regions involved in memory formation (hippocampus, parahippocampus, mamillary bodies and septum), a volume of interest (VOI) analysis and FWE correction for multiple comparisons at p<0.05 was employed.

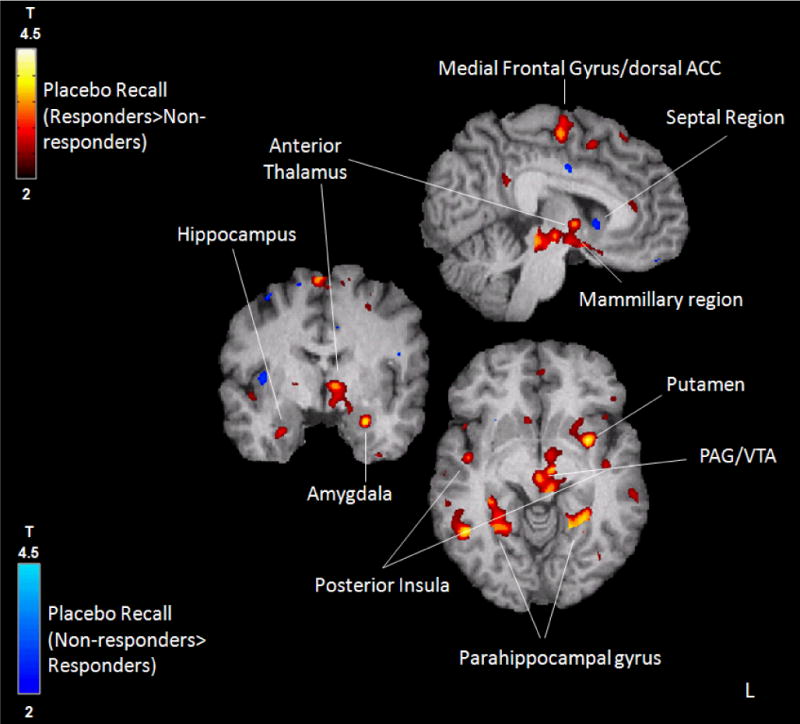

The whole brain analysis revealed a significant effect of recall group (placebo responders>non-responders) on μ-opioid system activation in regions previously associated with placebo responses: DLPFC (x, y, z, MNI coordinates, −42, 26, 13; Z=3.54), medial frontal gyrus/dorsal anterior cingulate cortex (−2, 9, 54; Z=3.22), posterior insula (−51, −17, 0; Z=3.48), amygdala (−27, −3, −22; Z=3.75), putamen (−33, 5, −5; Z=4.20), ventral striatum (19, 6, −15; Z=3.38), ventral tegmental area (VTA) (−8, −15, −8; Z=3.5) and PAG (−6, −29, −10; Z=3.44) (Supplementary Table 1).

The ROI analysis detected effects of recall group (placebo responders>non-responders) in regions involved in memory processing: left parahippocampus (−27, −45, −5; Z=3.67), left hippocampus (−27, −5, −22; Z=3.57) and left mamillary bodies (−6, −15, −8; Z=3.10), and with trend levels in the right hemisphere for all regions. Conversely, and nearing significance (−2, 11, −1; Z=2.6), greater μ-opioid system activation during placebo administration in the non-responder group was singularly noted in the septal region (placebo non-responders>responders) (Figure 1, Supplementary Table 1).

Figure 1.

Placebo recall (red-yellow: responders>non-responders; dark-light blue: non-responders>responders) group effect on μ-opioid system activation during placebo administration with expectation of analgesia.

Consistent with animal models showing an effect of the enkephalinergic system and μ-opioid receptors in learning and memory (6), our data suggest that in addition to its immediate placebo-analgesic effects, the μ-opioid receptor system is involved in the subsequent recall of placebo responses. Specifically, the VTA and the Papez circuit (hypothalamus-mammillary bodies, mamillo-thalamic tract, anterior thalamic nuclei, cingulate cortex and hippo/parahippocampus), implicated in reward-motivated learning and memory processing (4) appeared involved in these processes. Activation in the septal region in placebo non-responders recalling was also observed. If confirmed, this effect would be consistent with the memory impairment observed after intraseptal μ-opioid agonist administration (9),through inhibition of septohippocampal GABAergic neurons (10). This report extends previous findings on the role of the μ-opioid neurotransmitter system in acute placebo responses (2), and highlights a novel role of this system in the formation of memories of placebo analgesic effects in distinct neural circuits. These processes provide a framework to understand stimulus learning and therapeutic effect associations, of importance for the sustainability of placebo effects.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Supplementary information is available at Molecular Psychiatry’s website

References

- 1.Colloca L, Miller FG. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2011 Jun 27;366(1572):1859–1869. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2010.0398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Scott DJ, Stohler CS, Egnatuk CM, Wang H, Koeppe RA. Zubieta JK Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2008 Feb;65(2):220–231. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2007.34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.de la Fuente-Fernandez R. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2009 Dec;15(Suppl 3):S72–74. doi: 10.1016/S1353-8020(09)70785-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Adcock RA, Thangavel A, Whitfield-Gabrieli S, Knutson B, Gabrieli JD. Neuron. 2006 May;50(4)(3):507–517. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.03.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Simmons ML, Chavkin C. Int Rev Neurobiol. 1996;39:145–196. doi: 10.1016/s0074-7742(08)60666-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rigter H. Science. 1978 Apr 7;200(4337):83–85. doi: 10.1126/science.635578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Liu MG, Chen J. Neurosci Bull. 2009 Oct;25(5):237–266. doi: 10.1007/s12264-009-0905-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Arvidsson U, Riedl M, Chakrabarti S, Lee JH, Nakano AH, Dado RJ, et al. J Neurosci. 1995 May;15(5 Pt 1):3328–3341. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-05-03328.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bostock E, Gallagher M, King RA. Behav Neurosci. 1988 Oct;102(5):643–652. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.102.5.643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Alreja M, Shanabrough M, Liu W, Leranth C. J Neurosci. 2000 Feb 1;20(3):1179–1189. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-03-01179.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.