Abstract

Gambierol is a marine polycyclic ether toxin produced by the marine dinoflagellate Gambierdiscus toxicus and is a member of the ciguatoxin toxin family. Gambierol has been demonstrated to be either a low-efficacy partial agonist/antagonist of voltage-gated sodium channels or a potent blocker of voltage-gated potassium channels (Kvs). Here we examined the influence of gambierol on intact cerebrocortical neurons. We found that gambierol produced both a concentration-dependent augmentation of spontaneous Ca2+ oscillations, and an inhibition of Kv channel function with similar potencies. In addition, an array of selective as well as universal Kv channel inhibitors mimicked gambierol in augmenting spontaneous Ca2+ oscillations in cerebrocortical neurons. These data are consistent with a gambierol blockade of Kv channels underlying the observed increase in spontaneous Ca2+ oscillation frequency. We also found that gambierol produced a robust stimulation of phosphorylation of extracellular signal-regulated kinases 1/2 (ERK1/2). Gambierol-stimulated ERK1/2 activation was dependent on both inotropic [N-methyl-d-aspartate (NMDA)] and type I metabotropic glutamate receptors (mGluRs) inasmuch as MK-801 [NMDA receptor inhibitor; (5S,10R)-(+)-5-methyl-10,11-dihydro-5H-dibenzo[a,d]cyclohepten-5,10-imine maleate], S-(4)-CGP [S-(4)-carboxyphenylglycine], and MTEP [type I mGluR inhibitors; 3-((2-methyl-4-thiazolyl)ethynyl) pyridine] attenuated the response. In addition, 2-aminoethoxydiphenylborane, an inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor inhibitor, and U73122 (1-[6-[[(17b)-3-methoxyestra-1,3,5(10)-trien-17-yl]amino]hexyl]-1H-pyrrole-2,5-dione), a phospholipase C inhibitor, both suppressed gambierol-induced ERK1/2 activation, further confirming the role of type I mGluR-mediated signaling in the observed ERK1/2 activation. Finally, we found that gambierol produced a concentration-dependent stimulation of neurite outgrowth that was mimicked by 4-aminopyridine, a universal potassium channel inhibitor. Considered together, these data demonstrate that gambierol alters both Ca2+ signaling and neurite outgrowth in cerebrocortical neurons as a consequence of blockade of Kv channels.

Introduction

Gambierol is a ladder-shaped polyether toxin produced by the marine dinoflagellate Gambierdiscus toxicus and belongs to the ciguatoxin family of marine natural products (Lewis, 2001). Ingestion of particular tropical and subtropical reef fish species can result in ciguatera, a form of human poisoning. The neurologic features of ciguatera include sensory abnormalities such as paraesthesia, heightened nociception, unusual temperature perception, and taste alteration (Lewis, 2001; Pearn, 2001).

The chemical synthesis of gambierol has facilitated the investigations into the pathologic and pharmacological characterization of this compound (Fuwa et al., 2002, 2004; Johnson et al., 2005; Furuta et al., 2010). Gambierol is a potent toxin with a minimal lethal dose ranging from 50 to 80 μg/kg (i.p.) in mice, and has been demonstrated to elicit aberrant behavior in mice consistent with a neurotoxic insult (Ito et al., 2003; Fuwa et al., 2004).

Gambierol has been shown to bind to neurotoxin site 5 on voltage-gated sodium channels (VGSCs), albeit with modest micromolar affinity (Ito et al., 2003; LePage et al., 2007). This polyether toxin has also been shown to act as a low-efficacy VGSC partial agonist to stimulate sodium influx in cerebrocortical neurons (Cao et al., 2008). Consistent with its profile as a low-efficacy VGSC partial agonist, gambierol acts as a functional antagonist of neurotoxin site 5 on VGSCs in that it inhibits brevetoxin-2–induced Ca2+ influx and neurotoxicity in cerebellar granule neurons (LePage et al., 2007).

In contrast with gambierol’s modest affinity for VGSCs, it displays a high-affinity blockade of voltage-gated potassium channels (Kvs). Gambierol inhibits Kv1 and Kv3 currents at nanomolar concentrations (Cuypers et al., 2008; Kopljar et al., 2009). The molecular determinants for gambierol inhibition of Kv3.1 are located outside the K+ pore and involve lipid-facing residues on both the S5 and S6 segments of the α-subunits (Kopljar et al., 2009). This high-affinity gambierol binding site on Kv3.1 is accessible in the closed state.

The cellular consequences of gambierol exposure appear to be dependent on cell type. In neuroblastoma cells, gambierol produces an elevation of cytosolic calcium that was attributed to its action as a partial agonist at VGSCs (Louzao et al., 2006; Cagide et al., 2011). In rat cerebellar granule cells, different gambierol effects on Ca2+ dynamics have been reported for distinct concentration ranges and detection methods. At concentrations ranging from 10 nM to 10 μM, gambierol suppressed brevetoxin-induced elevation of intracellular Ca2+ concentration ([Ca2+]i) in cerebellar granule neurons measured at the population level (LePage et al., 2007). The ability of gambierol to inhibit both brevetoxin-induced elevation of [Ca2+]i and neurotoxicity was attributed to gambierol acting as a functional antagonist of neurotoxin site 5 on the VGSC. Another study using gambierol concentrations ranging from 0.1 to 30 μM reported the production of Ca2+ oscillations in cerebellar granule neurons at the single-cell level (Alonso et al., 2010). Although this latter action of micromolar gambierol was proposed to be secondary to inhibition of voltage-gated potassium channels, the requirement for micromolar concentrations is not consistent with gambierol’s nanomolar affinity for voltage-gated potassium channels (Ghiaroni et al., 2005; Cuypers et al., 2008; Kopljar et al., 2009).

Oscillations in cytoplasmic Ca2+ levels are a common mode of signaling in both excitable and nonexcitable cells and can increase the efficiency and specificity of gene expression (Dolmetsch et al., 1998; Li et al., 1998). Ca2+ oscillations have been reported in neocortical, hippocampal, and cerebellar granule neurons (Ogura et al., 1987; Nuñez et al., 1996; Dravid and Murray, 2004). Neurons in culture form functional synapses and rhythmic neurotransmitter release in a neuronal network may drive the synchronous oscillatory activity (Nakanishi and Kukita, 1998). Such synchronized Ca2+ oscillations in primary neuronal cultures measured at the population level with Ca2+-sensitive fluorescent probes have been strictly associated with bursts of action potentials (Pacico and Mingorance-Le Meur, 2014). These spontaneous Ca2+ oscillations have been implicated in the regulation of neural plasticity in developing neurons (Spitzer et al., 1995).

In this study, we evaluated the influence of gambierol on spontaneous Ca2+ oscillations in cerebrocortical neurons. Gambierol produced a robust augmentation of Ca2+ oscillations at concentrations consistent with Kv channel inhibition. This effect of gambierol was mimicked by an array of Kv1 subfamily inhibitors as well as the universal potassium channel inhibitors 4-aminopyridine and tetraethylammonium. Direct evidence for gambierol inhibition of Kv channel function in cerebrocortical neurons was derived using a thallium (TI+) influx assay. Gambierol also stimulated phosphorylation of extracellular signal-regulated kinases 1/2 (ERK1/2) in cerebrocortical neurons through a mechanism that involved activation of glutamate receptors. Finally, we found that gambierol enhanced neurite outgrowth, suggesting that modulation of potassium channel function and engagement of Ca2+ signaling can exert a trophic influence on cerebrocortical neurons.

Materials and Methods

Gambierol was synthesized as previously described (Johnson et al., 2006). Penicillin, streptomycin, and heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum were obtained from Atlanta Biologicals (Norcross, GA). The fluorescent dye Fluo-3-AM, Neurobasal medium, and pluronic acid F-127 were obtained from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA). TEA, 4-aminopyridine (4-AP), nifedipine, and 2-aminoethoxydiphenylborane (2-APB) were from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). All other potassium channel peptidic inhibitors used in this study were from Alomone Laboratory (Jerusalem, Israel). Anti-ERK1/2 and anti–phospho-ERK1/2 (p-ERK1/2) were from Cell Signaling Technology (Danvers, MA). MTEP [3-((2-methyl-4-thiazolyl)ethynyl) pyridine], U73122 (1-[6-[[(17b)-3-methoxyestra-1,3,5(10)-trien-17-yl]amino]hexyl]-1H-pyrrole-2,5-dione), NBQX [2,3-dihydroxy-6-nitro-7-sulfamoyl-benzo[f]quinoxaline-2,3-dione], and MK-801 [(5S,10R)-(+)-5-methyl-10,11-dihydro-5H-dibenzo[a,d]cyclohepten-5,10-imine maleate] were from Tocris Bioscience (Ellisville, MO).

Neocortical Neuron Culture.

Primary cultures of neocortical neurons were obtained from embryonic day 16 Swiss–Webster mice as previously described (Cao et al., 2010). The dissociated cells were plated onto poly(l-lysine)–coated 96-well clear-bottomed black-well (MidSci, St. Louis, MO) or 12-well culture plates at densities of 1.5 × 105 or 1.8 × 106 cells/well, respectively. For the neurite outgrowth experiments, cells were planted onto poly(l-lysine)–coated 1.2-mm coverslips in 24-well plates at a density of 1.5 × 104 cells/well. The Creighton University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee approved all animal use protocols.

Intracellular Ca2+ Monitoring.

Cerebrocortical neurons grown in 96-well plates were used for [Ca2+]i measurements at days in vitro (DIV) 11–13 as previously described (Cao et al., 2012). Neurons were loaded with Fluo-3 and then incubated at 37°C for 1 hour and transferred to the FLIPR Fluorescence Laser Plate Reader chamber (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA). Different concentrations of gambierol or potassium channel inhibitors were added to the wells after a 2-minute baseline recording from a compound plate in a volume of 50 μl at the rate of 30 μl/s using an automatic robotic system. The emitted fluorescence signals were recorded at 515–575 nm after excitation at 488 nm.

Western Blotting.

Equal amounts (30 µg) of cell lysates were loaded onto a 10% SDS-PAGE gel and transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane by electroblotting. After blocking, membranes were incubated overnight at 4°C with primary antibody (anti-ERK, 1:2000; anti–p-ERK, 1:2000). After washing, the membranes were incubated with the secondary antibody conjugated with horseradish peroxidase for 1 hour, washed four times in Tris-buffered saline/Tween 20, and incubated with ECL Plus (GE Healthcare Biosciences, Piscataway, NJ) for 4 minutes. Blots were exposed to HyBlot CL film (Denville Scientific, Inc., Metuchen, NJ) and developed. Membranes were stripped with stripping buffer (63 mM Tris base, 70 mM SDS, 0.0007% 2-mercaptoethanol, pH 6.8) and reblotted for further use.

Western blot densitometry was performed with an MCID image analysis system and data were obtained using MCID Basic 7.0 software (Image Analysis Software Solutions for Life Sciences, Interfocus Imaging Ltd., Linton, UK). Briefly, total band density was acquired by quantifying total pixels in a fixed rectangle over the desired band. ERK activation was quantified by normalizing p-ERK to total ERK after background subtraction.

Diolistic Labeling.

The Helios Gene Gun System (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) was used to deliver DiI-coated tungsten particles (1.3 μM) (Bio-Rad) into paraformaldehyde-fixed DIV 1 cerebrocortical neurons as previously described (Jabba et al., 2010).

Thallium Influx Assay.

The thallium influx assay was performed using the FluxOR kit (Invitrogen) as described in the product information sheet. Thallium influx in cerebrocortical neurons at DIV 11–13 was assessed. Briefly, the growth medium was replaced with dye loading buffer (80 μl/well) containing FluxOR dye and Powerload. The neurons were then incubated at 37°C in a CO2 incubator for 1 hour. The dye loading buffer was then replaced with 50 µl assay buffer. The thallium influx assay was performed in the presence of bumetanide (10 μM), a potassium-chloride cotransporter 2 (KCC2) K+-Cl− cotransporter inhibitor, and ouabain (100 μM), a Na+/K+ ATPase inhibitor. Various concentrations of gambierol or 1 mM of the broad spectrum K+ channel blocker 4-AP were added and neurons were incubated for an additional 10 minutes. Cells were then transferred to a FLIPR II Fluorescence Laser Plate Reader (Molecular Devices). The excitation wavelength was 490 nm, and emission fluorescence was recorded at 525 nm. After recording the baseline for 1 minute, 20 μl of a 5× thallium (1 mM final concentration) solution prepared in the kit stimulus buffer was added and fluorescence was subsequently measured for 350 seconds.

Data Analysis.

Quantification of Ca2+ oscillation data was achieved by counting the number of Ca2+ oscillations occurring in a 15-minute period after the addition of vehicle or potassium channel inhibitor. These data were presented as the percentage of control. Concentration-response relationships were analyzed by nonlinear regression analysis with GraphPad Prism software (version 6.0; GraphPad Software, Inc., San Diego, CA). Statistical significance was determined by an analysis of variance and, where appropriate, a Dunnett’s multiple comparison test was performed to compare responses of vehicle and drug-treated neurons.

Results

Gambierol Augments Spontaneous Ca2+ Oscillations in Cerebrocortical Neurons.

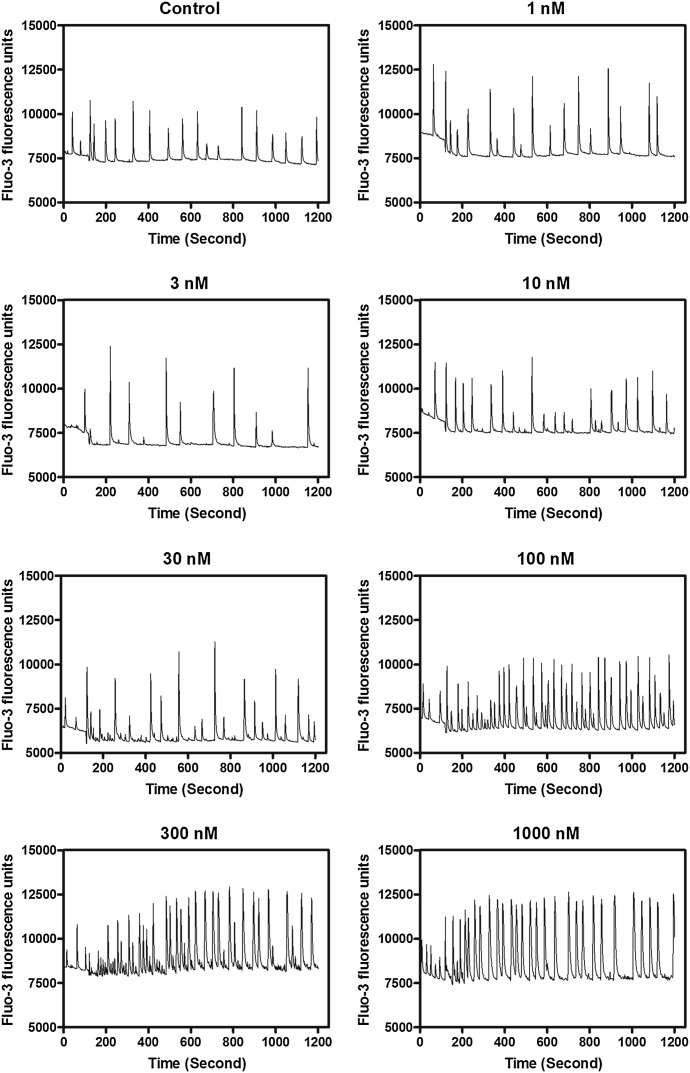

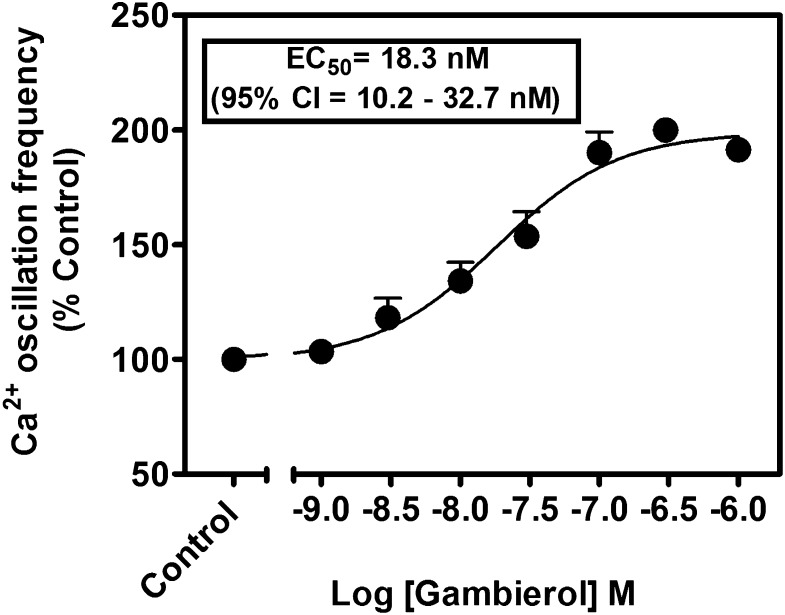

Gambierol has been demonstrated to act as either a low-efficacy partial agonist at VGSCs or a high-affinity Kv channel inhibitor (Inoue et al., 2003; Ghiaroni et al., 2005; Cuypers et al., 2008; Kopljar et al., 2009; Cagide et al., 2011; Pérez et al., 2012). Either activation of VGSCs or inhibition of Kv channels can alter Ca2+ dynamics in neurons (Wang and Gruenstein, 1997; Cao et al., 2011). We previously reported that primary cultures of cerebrocortical neurons display synchronized spontaneous Ca2+ oscillations (Dravid et al., 2004). We therefore examined the influence of gambierol on Ca2+ dynamics in cerebrocortical neurons. As depicted in Fig. 1, gambierol produced a potent, robust, and concentration-dependent stimulation of spontaneous Ca2+ oscillation frequency. The EC50 value for gambierol stimulation of Ca2+ oscillation frequency was 18.3 nM (95% confidence interval, 10.2–32.7 nM) (Fig. 2).

Fig. 1.

Representative time-response relationships for gambierol-augmented spontaneous Ca2+ oscillations in cerebrocortical neurons. This experiment was repeated three times with similar results.

Fig. 2.

Concentration-response relationships for gambierol stimulation of the spontaneous Ca2+ oscillations in cerebrocortical neurons. This experiment was repeated three times in triplicate with similar results. 95% CI, 95% confidence interval.

Gambierol Inhibits Thallium Influx in Cerebrocortical Neurons.

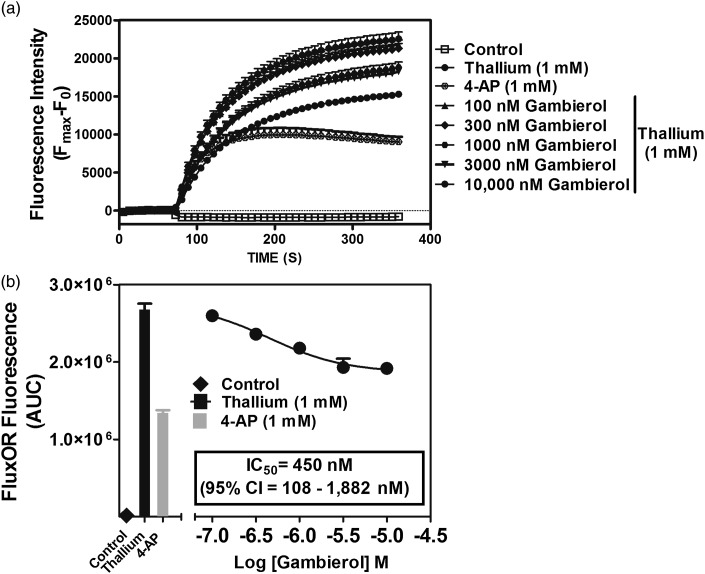

We next adapted a fluorescence-based Tl+ influx assay, based on the permeability of potassium channels to Tl+, for use in primary cultures of cerebrocortical neurons. The FluxOR thallium-sensitive fluorescent dye assay uses Tl+ influx as a surrogate indicator of K+ channel activity. Tl+-sensitive indicators report channel activity with a large fluorogenic response that is proportional to the number of open potassium channels on the cell, making it extremely useful for studying K+ channel function (Beacham et al., 2010). Given the reports of inhibition of Kv1 and Kv3.1 channels by gambierol, we used the FluxOR assay to detect K+ channel blockade in cerebrocortical neurons. Gambierol has been demonstrated to have high affinity for Kv1.1–Kv1.5 and Kv3.1, where it selectively interacts with closed channels. Gambierol appears to act as an intramembrane anchor, displacing lipids and prohibiting the voltage sensor domain of the channel from moving at physiologically relevant membrane potentials causing the channel to remain in the closed state (Kopljar et al., 2009).

Given that Tl+ is transported by both KCC2 and Na+/K+ ATPase (Johns, 1980; Delpire et al., 2009; Zhang et al., 2010), our preliminary data demonstrated that cerebrocortical neurons displayed a high basal Tl+-sensitive fluorescence signal (data not shown). To isolate Tl+ influx through voltage-gated potassium channels, we performed experiments in the presence of KCC2 inhibitor bumetanide (10 μM) and Na+/K+ ATPase inhibitor ouabain (100 μM) in cerebrocortical neurons. As depicted in Fig. 3, gambierol treatment produced a concentration-dependent inhibition of Tl+ influx-induced increase in FluxOR TM fluorescence. The gambierol IC50 value for this inhibition of Tl+ influx was 450 nM (95% confidence interval, 108–1882 nM).

Fig. 3.

Gambierol suppresses thallium influx in cerebrocortical neurons. Time-response (A) and concentration-response (B) relationships. This representative experiment with triplicate determinations was repeated twice with comparable results. 95% CI, 95% confidence interval; AUC, area under the curve.

Influence of an Array of Potassium Channel Inhibitors on Spontaneous Ca2+ Oscillations in Cerebrocortical Neurons.

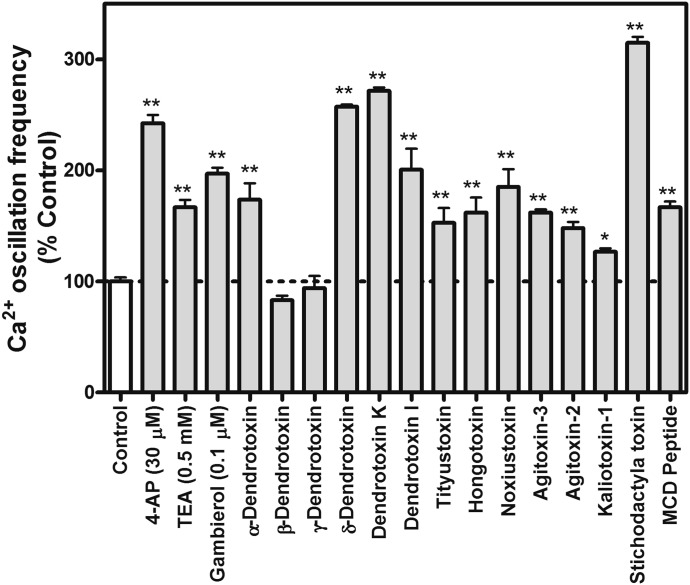

To confirm the role of Kv1 in the gambierol-induced increase Ca2+ oscillation frequency, we evaluated the influence of an array of specific Kv1 subfamily inhibitors on spontaneous Ca2+ oscillations. As depicted in Fig. 4, 12 of 14 Kv1 subfamily inhibitors including α-dendrotoxin, δ-dendrotoxin, dendrotoxin K, dendrotoxin I, tityustoxin, hongotoxin, noxiustoxin, agitoxin-2, agitoxin-3, kaliotoxin-1, stichodactyla toxin, and mast cell degranulating peptide (all at a concentration of 100 nM) significantly enhanced Ca2+ oscillations. However, two Kv1 subfamily inhibitors, β-dendrotoxin and γ-dendrotoxin, were inactive. In addition to the inhibition of the Kv1 subfamily, gambierol was also found to bind to and stabilize the closed state of Kv3.1 (Kopljar et al., 2009). We therefore examined whether inhibition of Kv3.1 can affect Ca2+ oscillations. As depicted in Fig. 4, 4-AP at a low concentration of 30 μM, which selectively suppresses Kv3.1 (Grissmer et al., 1994), produced a significant increase in spontaneous Ca2+ oscillations. TEA at a concentration of 0.5 mM also produced a significant increase in the frequency of spontaneous Ca2+ oscillations.

Fig. 4.

Influence of an array of voltage-gated potassium channel inhibitors on the spontaneous Ca2+ oscillations in cerebrocortical neurons. Each bar represents the mean ± S.E.M. from two experiments performed in duplicate (n = 4 for each bar) (*P < 0.05; **P < 0.01, inhibitor versus control by analysis of variance). MCD peptide, mast cell degranulating peptide.

Gambierol-Enhanced ERK1/2 Activation in Cerebrocortical Neurons.

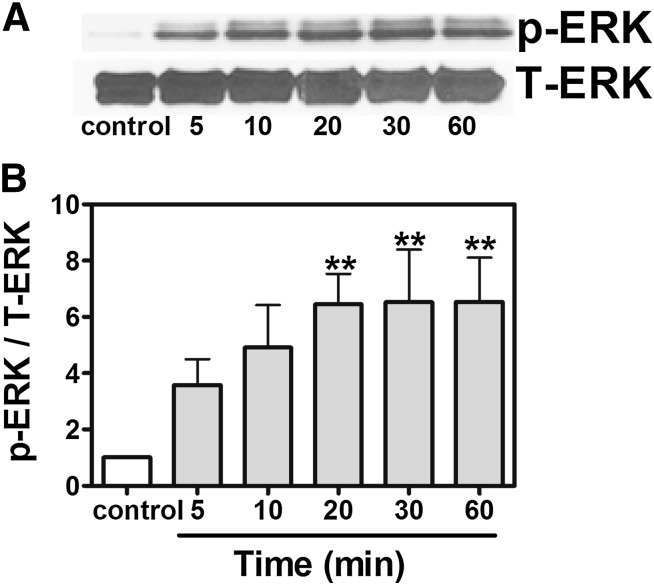

Ca2+ oscillation frequency can reduce the effective Ca2+ threshold for the activation of the ERK/mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathway (Kupzig et al., 2005). We therefore examined the possibility of ERK1/2 activation in response to gambierol exposure. As shown in Fig. 5, gambierol (100 nM) produced a robust stimulation of ERK1/2 phosphorylation as early as 5 minutes after exposure and gradually increased as a function of time, reaching the plateau at 20 minutes.

Fig. 5.

Gambierol-enhanced ERK1/2 activation. (A) Representative Western blots for gambierol (100 nM) stimulation of ERK1/2 phosphorylation (p-ERK) as a function of time. (B) Quantification of ERK1/2 phosphorylation after exposure of cerebrocortical neurons to gambierol (100 nM). These data were pooled from four independent experiments (n = 4 for each bar) (**P < 0.01, gambierol versus vehicle control by analysis of variance). T-ERK, total ERK.

Involvement of Glutamate Receptor Signaling Pathways in Gambierol-Induced ERK1/2 Activation.

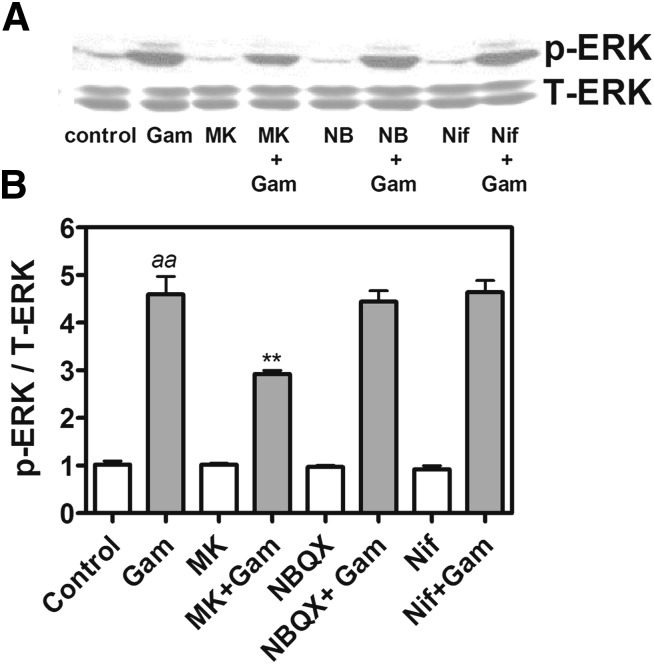

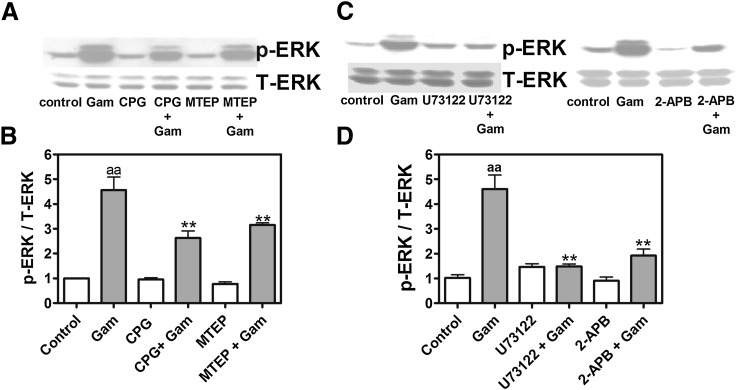

We next examined the signaling mechanisms underlying gambierol-induced ERK1/2 activation. As depicted in Fig. 6, pretreament with nifedipine (1 μM), an L-type Ca2+ channel inhibitor, was without effect on gambierol-induced ERK1/2 activation. The N-methyl-d-aspartate (NMDA) receptor blocker MK-801 (1 μM), but not AMPA (α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid)/kianate receptor antagonist NBQX (3 μM), significantly reduced gambierol-induced ERK1/2 phosphorylation from 460% ± 55% of control to 292% ± 15% (n = 4, P < 0.01) (Fig. 6). The involvement of metabotropic glutamate receptors (mGluRs) in the gambierol response was indicated using S-(4)-CPG [S-(4)-carboxyphenylglycine] (500 μM), an mGluR1 antagonist, or MTEP (1 μM), a mGluR5 antagonist. Both mGluR antagonists produced a significant reduction in gambierol-induced ERK1/2 activation from 456% ± 53% of control to 263% ± 29% (n = 3, P < 0.01) and 316% ± 8% (n = 3, P < 0.01), respectively (Fig. 7, A and B). We next assessed whether the phospholipase C (PLC) signaling pathway downstream from type I mGluRs contributed to gambierol-induced ERK activation. Pretreatment with either U73122 (3 μM), a PLC inhibitor, or 2-APB (10 μM), an inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor antagonist, abolished gambierol-induced ERK1/2 activation (Fig. 7, C and D).

Fig. 6.

NMDA receptor inhibitor MK-801, but not L-type Ca2+ channel antagonist nifedipine or AMPA/kinate receptor antagonist NBQX, inhibited gambierol-induced ERK1/2 phosphorylation. (A) Representative Western blots for the influence of MK-801 (1 μM), nifedipine (1 μM), or NBQX (3 μM) on 100 nM gambierol-induced ERK1/2 phosphorylation (p-ERK). (B) Quantification of the influence of MK-801, nifedipine, and NBQX on gambierol-induced ERK1/2 phosphorylation. Each data point represents the mean ± S.E.M. from four Western blot experiments (n = 4 for each bar) (aaP < 0.01, gambierol versus vehicle control; **P < 0.01, gambierol + MK-801 versus gambierol by analysis of variance). Gam, gambierol; MK, MK-801; NB, NBQX; Nif, nifedipine; T-ERK, total ERK.

Fig. 7.

Involvement of mGluR1/5, PLC, and inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptors in gambierol-induced ERK1/2 +phosphorylation. (A) Representative Western blots for S-(4)-CPG (500 μM) and MTEP (1 μM) inhibition of 100 nM gambierol-induced ERK1/2 phosphorylation (p-ERK). (B) Quantification of the influence of S-(4)-CPG and MTEP on gambierol-induced ERK1/2 phosphorylation (aaP < 0.01, gambierol versus vehicle control; **P < 0.01, gambierol + inhibitor versus gambierol by analysis of variance). (C) Representative Western blots for U73122 (3 μM) and 2-APB (10 μM) inhibition of gambierol-induced ERK1/2 phosphorylation (p-ERK). (D) Quantification of the inhibition of U73122 and 2-APB on gambierol-induced ERK1/2 phosphorylation (aaP < 0.01, gambierol versus vehicle control; **P < 0.01, gambierol + inhibitor versus gambierol by analysis of variance). CPG, S-(4)-CPG; Gam, gambierol; T-ERK, total ERK.

Inhibition of Voltage-Gated Potassium Channel Stimulated Neurite Outgrowth in Immature Cerebrocortical Neurons.

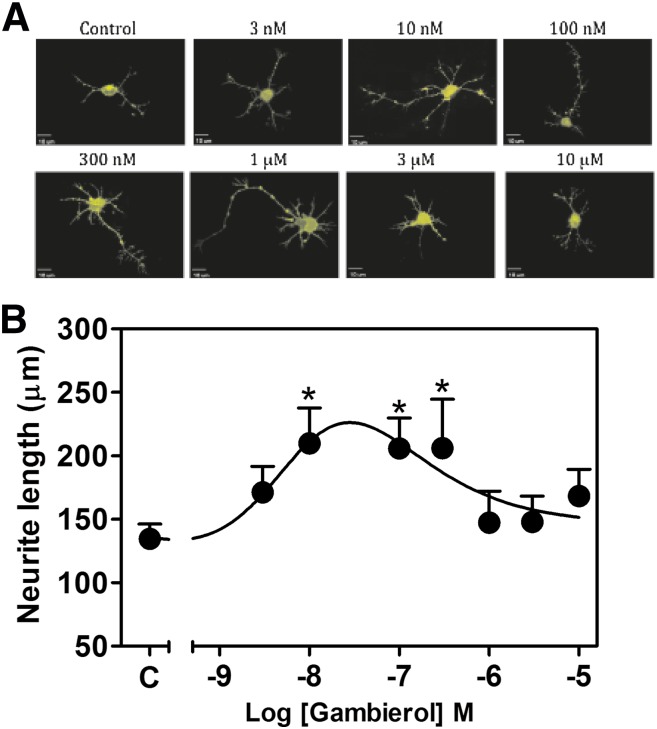

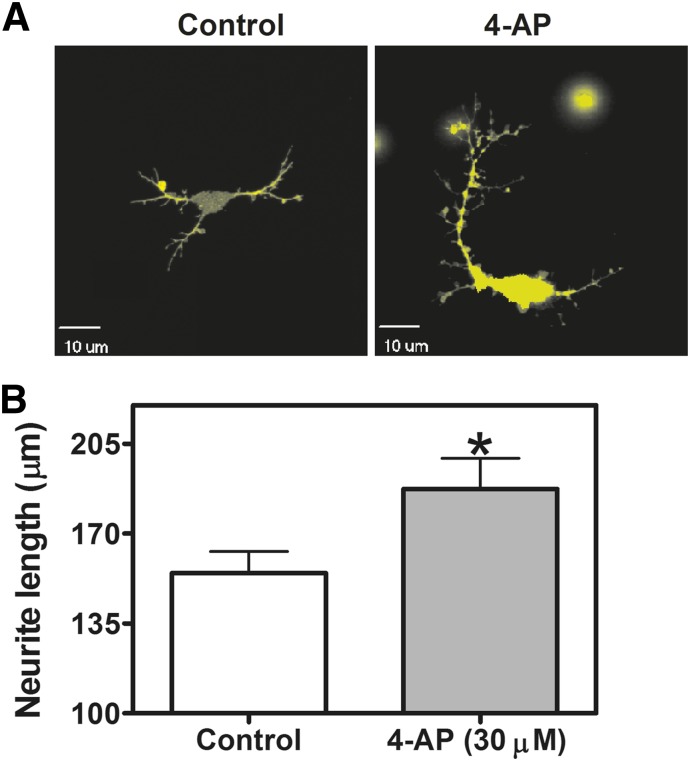

Voltage-gated potassium channels are responsible for action potential repolarization and inhibition of voltage-gated potassium channels results in the prolongation of the action potential duration (Wulff et al., 2009). Depolarizing stimuli, such as that produced by elevation of extracellular potassium concentration, has been demonstrated to stimulate dendritic growth in hippocampal (Wayman et al., 2006) and cerebrocortical neurons (Redmond et al., 2002). In addition, spontaneous Ca2+ oscillations have been implicated in the regulation of neuronal structural plasticity in developing neurons (Spitzer et al., 1995) and Ca2+ spikes have been demonstrated to modulate neuronal migration in cerebellar granule neurons (Komuro and Rakic, 1996). We therefore examined the influence of gambierol on the neurite outgrowth in immature cerebrocortical neurons. Three hours after plating, primary cultures of immature cerebrocortical neurons were exposed to various concentrations of gambierol ranging from 3 nM to 10 μM for 24 hours, and total neurite outgrowth was then assessed. Diolistic labeling was used to visualize neurons and assess total neurite outgrowth of control and gambierol-treated neurons. Gambierol enhanced neurite outgrowth in immature cerebrocortical neurons, with the low concentrations of 10, 100, and 300 nM producing a maximum 1.5-fold increase in total neurite length (Fig. 8A). By contrast, higher concentrations (>300 nM) of gambierol progressively decreased neurite outgrowth (Fig. 8B). We also assessed the influence of 4-AP at the low Kv3.1 selective concentration of 30 μM; this concentration of 4-AP produced a significant stimulation of neurite outgrowth in cerebrocortical neurons (Fig. 9), confirming the role of this Kv channel in the regulation of neuronal development.

Fig. 8.

Gambierol-stimulated neurite outgrowth. (A) Representative images of DiI-loaded immature cerebrocortical neurons at 24 hours after plating. Various concentrations of gambierol were added to the culture medium at 3 hours after plating. Depicted neurons were visualized by diolistic loading with DiI. (B) Quantification of concentration-response effects of gambierol on neurite outgrowth at 24 hours after plating. Gambierol-enhanced neurite outgrowth displayed a hormetic concentration-response relationship. The experiment was performed twice, and each point represents the mean value derived from analysis of 10–20 neurons. *P < 0.05, gambierol versus control by analysis of variance.

Fig. 9.

Potassium channel inhibitor 4-AP stimulated neurite outgrowth in cerebrocortical neurons. Representative images (A) and quantification (B) of 4-AP (30 μM)–induced neurite outgrowth. Each data point represents the mean value derived from analysis of 50–60 neurons (*P < 0.05, 4-AP versus vehicle control by the t test).

Discussion

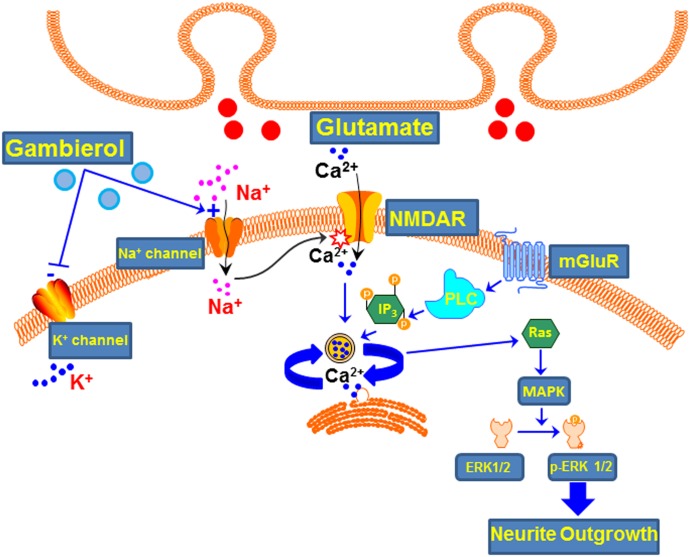

As depicted in Fig. 10, gambierol has been demonstrated to be both a low-efficacy partial agonist of VGSCs (Inoue et al., 2003; LePage et al., 2007; Cao et al., 2008) and a high-affinity Kv channel blocker (Ghiaroni et al., 2005; Cuypers et al., 2008; Kopljar et al., 2009; Pérez et al., 2012). Here we demonstrate that gambierol augments spontaneous Ca2+ oscillation frequency in cerebrocortical neurons. This response likely stems from gambierol’s ability to inhibit Kv channel function in cerebrocortical neurons. In support of this, we found that 1) gambierol produced a concentration-dependent inhibition of Tl+ influx through Kv channels in cerebrocortical neurons; 2) an array of Kv1 subtype-specific inhibitors as well as the universal potassium channel inhibitors 4-AP and TEA stimulated spontaneous Ca2+ oscillation frequency; and 3) gambierol’s IC50 value for inhibition of Tl+ influx was somewhat greater than that for stimulation of Ca2+ oscillations, which is most likely a function of Tl+ influx through multiple Kv channels with differing affinities for gambierol. The maximal inhibition of Tl+ influx fluorescence produced by gambierol in cerebrocortical neurons was approximately 67% of the inhibition produced by the universal K+ channel inhibitor 4-AP (1 mM). These data suggest that gambierol does not inhibit all 4-AP–sensitive Kv channels expressed in cerebrocortical neurons.

Fig. 10.

Summary of gambierol molecular targets and downstream signaling events. Gambierol acts as a high-affinity (in nanomoles) blocker of K+ channels and a modest affinity (in micromoles), low-efficacy partial agonist at Na+ channels. Collectively, these actions increase neuronal excitability and spontaneous Ca2+ oscillations leading to p-ERK activation with a bidirectional influence on neurite outgrowth. IP3, inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate; NMDAR, NMDA receptor.

In cerebellar granule neurons, gambierol has been reported to induce Ca2+ oscillations, which was interpreted to be a consequence of potassium channel blockade (Alonso et al., 2010). Although this effect of gambierol parallels that observed in the this study in which a potentiation of spontaneous Ca2+ oscillations was observed, the response in cerebellar granule neurons required micromolar gambierol concentrations that were somewhat higher than that required for Kv channel blockade (Ghiaroni et al., 2005; Cuypers et al., 2008; Kopljar et al., 2009). Whether measured at the single-cell (Alonso et al., 2010) or population level (this report), both studies observed that Ca2+ oscillations in the presence of gambierol were highly synchronous. Inhibition of Kv channels with Ba2+ was previously reported to increase the frequency of Ca2+ oscillations in spontaneously active hypothalamic neurons (Costantin and Charles, 2001), and it is reasonable to infer that both the induction of Ca2+ oscillations in cerebellar granule neurons (Alonso et al., 2010) and the increase in the frequency of Ca2+ oscillations in cerebrocortical neurons reported herein derive from gambierol-induced inhibition of Kv channels.

In oocyte recording experiments, gambierol inhibited Kv1.1–Kv1.5, but not Kv1.6, channel currents (Cuypers et al., 2008; Kopljar et al., 2009). We found that 12 of 14 Kv1 channel subfamily inhibitors produced a significant stimulation of spontaneous Ca2+ oscillations. However, two Kv1 subfamily toxins, β-dendrotoxin and γ-dendrotoxin, were without effect on Ca2+ oscillation frequency. It was previously reported that α-dendrotoxin inhibited the binding of [125I]δ-dendrotoxin to brain sections, whereas β- and γ-dendrotoxin were less effective as competitors of δ-dendrotoxin binding (Awan and Dolly, 1991). Thus, the inactivity of β- and γ-dendrotoxin on Ca2+ oscillations may be due to their unique selectivity profile for subtypes of Kv1 channels. Nonetheless, the potentiation of spontaneous Ca2+ oscillation frequency by an array of Kv1 subfamily inhibitors points to a role of Kv1 channels in the regulation of Ca2+ oscillation frequency.

In addition to the inhibition of Kv1.1–Kv1.5 channels, gambierol exerts a high-affinity block of Kv3.1 by stabilizing the closed state of the channel (Kopljar et al., 2009). The Kv3.1 potassium channel is a delayed rectifier channel with fast activation and deactivation kinetics and was previously demonstrated to be expressed in the cerebral cortex (Ozaita et al., 2002). The Kv3.1 channel in the cerebral cortex has a role in the fast repolarization of action potentials that enables neurons to fire repetitively at high frequency (Rudy et al., 1999). Kv3.1 was also shown to be more sensitive to 4-AP exposure than Kv1.1–Kv1.5 (Grissmer et al., 1994). Using a Kv3.1-selective, low concentration of 4-AP (30 μM), we found that 4-AP produced a significant stimulation on Ca2+ oscillation frequency. A similar response was observed with a low concentration of TEA (0.5 mM). These results are consonant with a previous demonstration of the ability of 4-AP and TEA to produce Ca2+ oscillations in cortical neurons (Wang and Gruenstein, 1997), and suggest that Kv3.1 channel inhibition contributes to gambierol’s potentiation of spontaneous Ca2+ oscillation frequency. In cerebellar granule neurons, both 4-AP and gambierol-induced Ca2+ oscillations involved glutamate release and NMDA receptor activation, suggesting a shared mechanism of action (Alonso et al., 2010).

MAPKs constitute a family of serine/threonine kinases, of which ERK1/2 participates in physiologic events such as synaptic plasticity and learning and memory (Sweatt, 2001). We found that gambierol produced a robust stimulation of ERK1/2 phosphorylation. Although a potent high-efficacy VGSC activator was demonstrated to stimulate ERK1/2 activation (Dravid et al., 2004), it is unlikely that gambierol-induced (100 nM) ERK1/2 phosphorylation was a consequence of activation of VGSCs. Gambierol is a very low-efficacy partial VGSC agonist with a Ki value for neurotoxin site 5 in the micromolar range (Ki = 4.8 μM) (Inoue et al., 2003; LePage et al., 2007). The low efficacy of gambierol at VGSCs was demonstrated with measurements of sodium influx in cerebrocortical neurons (Cao et al., 2008). Of 11 VGSC gating modifiers demonstrated to be capable of producing sodium influx in cerebrocortical neurons, gambierol displayed the lowest efficacy (0.11) with a maximal increment in [Na+]i of only 4 mM (Cao et al., 2008). The gambierol-induced ERK1/2 phosphorylation observed here therefore most likely resulted from augmentation of spontaneous Ca2+ oscillations due to inhibition of Kv channels. Ca2+ oscillations reduce the effective cytoplasmic [Ca2+] threshold for the activation of Ras, and Ca2+ oscillatory frequency is optimized for activation of Ras and the ERK/MAPK pathway (Kupzig et al., 2005). Our data are also consistent with the previous demonstration that the Kv channel blockers 4-AP and TEA increased ERK1/2 phosphorylation as a consequence of enhanced Ca2+ transients in rat cardiomyocytes (Tahara et al., 2001).

In contrast with 4-AP–induced ERK1/2 activation that was dependent on L-type Ca2+ channels in cardiomyocytes (Tahara et al., 2001), our data indicated that gambierol-induced ERK1/2 activation did not require Ca2+ influx through L-type Ca2+ channels. Gambierol-induced ERK activation in cerebrocortical neurons did, however, involve NMDA receptors inasmuch as MK-801 reduced the response. We also demonstrated the involvement of the type I mGluR signaling pathway in the response to gambierol since both S-(4)-CPG and MTEP partially attenuated gambierol-induced ERK1/2 activation. In addition, both U73122, a PLC inhibitor, and 2-APB, an inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor antagonist, produced nearly complete inhibition of gambierol-induced ERK1/2 activation. These data suggest that gambierol-induced ERK1/2 phosphorylation involves Kv channel inhibition, release of glutamate, and engagement of mGluR signaling through PLC. This is consistent with several previous studies demonstrating that potassium channel inhibitors such as 4-AP produce glutamate release in a variety of neural preparations (Tapia and Sitges, 1982; Tibbs et al., 1989; Peña and Tapia, 2000).

Neuronal activity regulates intracellular Ca2+, and activity-dependent calcium signaling has been shown to regulate dendritic growth and branching (Konur and Ghosh, 2005). Activity-dependent dendritic growth is associated with Ca2+ influx through the NMDA receptor with subsequent ERK1/2 activation (Wayman et al., 2006). Moreover, NMDA receptor–dependent calmodulin signaling cascades have been shown to regulate neurite/axonal outgrowth (Wayman et al., 2004) and activity-dependent synaptogenesis (Saneyoshi et al., 2008). Given the ability of gambierol to increase Ca2+ oscillation frequency and stimulate ERK1/2 phosphorylation, we assessed the influence of gambierol on neurite outgrowth. Gambierol enhanced neurite outgrowth with a bidirectional concentration-response relationship. A Kv3.1-selective, low concentration (30 μM) of 4-AP also enhanced cerebrocortical neuron neurite outgrowth. The similar bidirectional patterns shown by NMDA (George et al., 2012) and gambierol on neurite outgrowth are consistent with a role for NMDA receptors in the effects of gambierol on cerebrocortical neuron growth. An inverted-U model describes the relationship between NMDA receptor activity and neuronal survival and growth (Lipton and Nakanishi, 1999). This inverted-U NMDA concentration-response relationship has primarily, but not exclusively, been regressed to intracellular Ca2+ regulation. An optimal window for [Ca2+]i is required for activity-dependent neurite extension and branching, with low levels stabilizing growth cones and high levels stalling them, in both cases preventing extension (Gomez and Spitzer, 2000). Given that NMDA also displays an inverted-U concentration-response relationship for ERK1/2 activation (Dravid et al., 2004), we suggest that similar mechanisms are operative in the bidirectional effects of NMDA and gambierol on neurite outgrowth.

Considered together, we have demonstrated that gambierol augments spontaneous Ca2+ oscillation frequency and ERK1/2 activation in cerebrocortical neurons. We suggest that these actions of gambierol are a consequence of Kv channel inhibition inasmuch as they are mimicked by an array of selective and universal Kv channel blockers, and gambierol inhibited TI+ influx through potassium channels in cerebrocortical neurons. We also found that gambierol affects cerebrocortical neuron neurite outgrowth in a bidirectional manner paralleling the profile for NMDA-induced neurite outgrowth. This suggests that similar mechanisms are operative in the bidirectional effects of NMDA and gambierol on neuronal growth. Polyether Kv channel blockers such as gambierol may represent a novel class of compounds capable of producing changes in the structural plasticity of the brain after neural insult such as trauma or stroke.

Abbreviations

- 2-APB

2-aminoethoxydiphenylborane

- 4-AP

4-aminopyridine

- AMPA

α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid

- [Ca2+]i

intracellular Ca2+ concentration

- DIV

days in vitro

- ERK1/2

extracellular signal-regulated kinases 1/2

- KCC2

potassium-chloride cotransporter 2

- Kv

voltage-gated potassium channel

- MAPK

mitogen-activated protein kinase

- mGluR

metabotropic glutamate receptor

- MK-801

(5S,10R)-(+)-5-methyl-10,11-dihydro-5H-dibenzo[a,d]cyclohepten-5,10-imine maleate

- MTEP

3-((2-methyl-4-thiazolyl)ethynyl) pyridine

- NBQX

2,3-dihydroxy-6-nitro-7-sulfamoyl-benzo[f]quinoxaline-2,3-dione

- NMDA

N-methyl-d-aspartate

- p-ERK1/2

phospho-ERK1/2

- PLC

phospholipase C

- S-(4)-CPG

S-(4)-carboxyphenylglycine

- U73122

1-[6-[[(17b)-3-methoxyestra-1,3,5(10)-trien-17-yl]amino]hexyl]-1H-pyrrole-2,5-dione

- VGSC

voltage-gated sodium channel

Authorship Contributions

Participated in research design: Cao, Mehrotra, Rainier, Murray.

Conducted experiments: Cao, Cui, Busse, Mehrotra.

Contributed new reagents or analytic tools: Rainier.

Performed data analysis: Cao, Cui, Busse, Mehrotra, Murray.

Wrote or contributed to the writing of the manuscript: Cao, Mehrotra, Rainier, Murray.

Footnotes

This work was supported in part by the National Institutes of Health National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke [Grant 2R01-NS053398 (to T.F.M.)]; and the National Institutes of Health National Center for Research Resources [Grant G20-RR024001]. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Center for Research Resources or the National Institutes of Health.

References

- Alonso E, Vale C, Sasaki M, Fuwa H, Konno Y, Perez S, Vieytes MR, Botana LM. (2010) Calcium oscillations induced by gambierol in cerebellar granule cells. J Cell Biochem 110:497–508 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Awan KA, Dolly JO. (1991) K+ channel sub-types in rat brain: characteristic locations revealed using beta-bungarotoxin, alpha- and delta-dendrotoxins. Neuroscience 40:29–39 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beacham DW, Blackmer T, O’ Grady M, Hanson GT. (2010) Cell-based potassium ion channel screening using the FluxOR assay. J Biomol Screen 15:441–446 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cagide E, Louzao MC, Espiña B, Ares IR, Vieytes MR, Sasaki M, Fuwa H, Tsukano C, Konno Y, Yotsu-Yamashita M, et al. (2011) Comparative cytotoxicity of gambierol versus other marine neurotoxins. Chem Res Toxicol 24:835–842 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao Z, George J, Gerwick WH, Baden DG, Rainier JD, Murray TF. (2008) Influence of lipid-soluble gating modifier toxins on sodium influx in neocortical neurons. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 326:604–613 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao Z, LePage KT, Frederick MO, Nicolaou KC, Murray TF. (2010) Involvement of caspase activation in azaspiracid-induced neurotoxicity in neocortical neurons. 114: 323–334 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao Z, Hammock BD, McCoy M, Rogawski MA, Lein PJ, Pessah IN. (2012) Tetramethylenedisulfotetramine alters Ca²⁺ dynamics in cultured hippocampal neurons: mitigation by NMDA receptor blockade and GABA(A) receptor-positive modulation. Toxicol Sci 130: 362–372 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao Z, Shafer TJ, Murray TF. (2011) Mechanisms of pyrethroid insecticide-induced stimulation of calcium influx in neocortical neurons. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 336:197–205 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costantin JL, Charles AC. (2001) Modulation of Ca(2+) signaling by K(+) channels in a hypothalamic neuronal cell line (GT1-1). J Neurophysiol 85:295–304 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuypers E, Abdel-Mottaleb Y, Kopljar I, Rainier JD, Raes AL, Snyders DJ, Tytgat J. (2008) Gambierol, a toxin produced by the dinoflagellate Gambierdiscus toxicus, is a potent blocker of voltage-gated potassium channels. Toxicon 51: 974–983 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delpire E, Days E, Lewis LM, Mi D, Kim K, Lindsley CW, Weaver CD. (2009) Small-molecule screen identifies inhibitors of the neuronal K-Cl cotransporter KCC2. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 106:5383–5388 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dolmetsch RE, Xu K, Lewis RS. (1998) Calcium oscillations increase the efficiency and specificity of gene expression. Nature 392:933–936 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dravid SM, Baden DG, Murray TF. (2004) Brevetoxin activation of voltage-gated sodium channels regulates Ca dynamics and ERK1/2 phosphorylation in murine neocortical neurons. J Neurochem 89:739–749 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dravid SM, Murray TF. (2004) Spontaneous synchronized calcium oscillations in neocortical neurons in the presence of physiological [Mg(2+)]: involvement of AMPA/kainate and metabotropic glutamate receptors. Brain Res 1006:8–17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furuta H, Hasegawa Y, Hase M, Mori Y. (2010) Total synthesis of gambierol by using oxiranyl anions. Chemistry 16:7586–7595 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuwa H, Kainuma N, Tachibana K, Sasaki M. (2002) Total synthesis of (-)-gambierol. J Am Chem Soc 124:14983–14992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuwa H, Kainuma N, Tachibana K, Tsukano C, Satake M, Sasaki M. (2004) Diverted total synthesis and biological evaluation of gambierol analogues: elucidation of crucial structural elements for potent toxicity. Chemistry 10:4894–4909 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- George J, Baden DG, Gerwick WH, Murray TF. (2012) Bidirectional influence of sodium channel activation on NMDA receptor-dependent cerebrocortical neuron structural plasticity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 109:19840–19845 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghiaroni V, Sasaki M, Fuwa H, Rossini GP, Scalera G, Yasumoto T, Pietra P, Bigiani A. (2005) Inhibition of voltage-gated potassium currents by gambierol in mouse taste cells. Toxicol Sci 85: 657–665 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomez TM, Spitzer NC. (2000) Regulation of growth cone behavior by calcium: new dynamics to earlier perspectives. J Neurobiol 44:174–183 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grissmer S, Nguyen AN, Aiyar J, Hanson DC, Mather RJ, Gutman GA, Karmilowicz MJ, Auperin DD, Chandy KG. (1994) Pharmacological characterization of five cloned voltage-gated K+ channels, types Kv1.1, 1.2, 1.3, 1.5, and 3.1, stably expressed in mammalian cell lines. Mol Pharmacol 45:1227–1234 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inoue M, Hirama M, Satake M, Sugiyama K, Yasumoto T. (2003) Inhibition of brevetoxin binding to the voltage-gated sodium channel by gambierol and gambieric acid-A. Toxicon 41: 469–474 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito E, Suzuki-Toyota F, Toshimori K, Fuwa H, Tachibana K, Satake M, Sasaki M. (2003) Pathological effects on mice by gambierol, possibly one of the ciguatera toxins. Toxicon 42: 733–740 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jabba SV, Prakash A, Dravid SM, Gerwick WH, Murray TF. (2010) Antillatoxin, a novel lipopeptide, enhances neurite outgrowth in immature cerebrocortical neurons through activation of voltage-gated sodium channels. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 332:698–709 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johns A. (1980) Ouabain-sensitive thallium fluxes in smooth muscle of rabbit uterus. J Physiol 309:391–403 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson HW, Majumder U, Rainier JD. (2005) The total synthesis of gambierol. J Am Chem Soc 127:848–849 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson HW, Majumder U, Rainier JD. (2006) Total synthesis of gambierol: subunit coupling and completion. Chemistry 12:1747–1753 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Komuro H, Rakic P. (1996) Intracellular Ca2+ fluctuations modulate the rate of neuronal migration. Neuron 17:275–285 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konur S, Ghosh A. (2005) Calcium signaling and the control of dendritic development. Neuron 46:401–405 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kopljar I, Labro AJ, Cuypers E, Johnson HW, Rainier JD, Tytgat J, Snyders DJ. (2009) A polyether biotoxin binding site on the lipid-exposed face of the pore domain of Kv channels revealed by the marine toxin gambierol. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 106:9896–9901 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kupzig S, Walker SA, Cullen PJ. (2005) The frequencies of calcium oscillations are optimized for efficient calcium-mediated activation of Ras and the ERK/MAPK cascade. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 102:7577–7582 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LePage KT, Rainier JD, Johnson HW, Baden DG, Murray TF. (2007) Gambierol acts as a functional antagonist of neurotoxin site 5 on voltage-gated sodium channels in cerebellar granule neurons. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 323:174–179 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis RJ. (2001) The changing face of ciguatera. Toxicon 39:97–106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li W, Llopis J, Whitney M, Zlokarnik G, Tsien RY. (1998) Cell-permeant caged InsP3 ester shows that Ca2+ spike frequency can optimize gene expression. Nature 392:936–941 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipton SA, Nakanishi N. (1999) Shakespeare in love—with NMDA receptors? Nat Med 5:270–271 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Louzao MC, Cagide E, Vieytes MR, Sasaki M, Fuwa H, Yasumoto T, Botana LM. (2006) The sodium channel of human excitable cells is a target for gambierol. Cell Physiol Biochem 17: 257–268 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakanishi K, Kukita F. (1998) Functional synapses in synchronized bursting of neocortical neurons in culture. Brain Res 795:137–146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nuñez L, Sanchez A, Fonteriz RI, Garcia-Sancho J. (1996) Mechanisms for synchronous calcium oscillations in cultured rat cerebellar neurons. Eur J Neurosci 8:192–201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogura A, Iijima T, Amano T, Kudo Y. (1987) Optical monitoring of excitatory synaptic activity between cultured hippocampal neurons by a multi-site Ca2+ fluorometry. Neurosci Lett 78:69–74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ozaita A, Martone ME, Ellisman MH, Rudy B. (2002) Differential subcellular localization of the two alternatively spliced isoforms of the Kv3.1 potassium channel subunit in brain. J Neurophysiol 88:394–408 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pacico N, Mingorance-Le Meur A. (2014) New in vitro phenotypic assay for epilepsy: fluorescent measurement of synchronized neuronal calcium oscillations. PLoS ONE 9:e84755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearn J. (2001) Neurology of ciguatera. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 70:4–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peña F, Tapia R. (2000) Seizures and neurodegeneration induced by 4-aminopyridine in rat hippocampus in vivo: role of glutamate- and GABA-mediated neurotransmission and of ion channels. Neuroscience 101:547–561 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pérez S, Vale C, Alonso E, Fuwa H, Sasaki M, Konno Y, Goto T, Suga Y, Vieytes MR, Botana LM. (2012) Effect of gambierol and its tetracyclic and heptacyclic analogues in cultured cerebellar neurons: a structure-activity relationships study. Chem Res Toxicol 25:1929–1937 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Redmond L, Kashani AH, Ghosh A. (2002) Calcium regulation of dendritic growth via CaM kinase IV and CREB-mediated transcription. Neuron 34:999–1010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudy B, Chow A, Lau D, Amarillo Y, Ozaita A, Saganich M, Moreno H, Nadal MS, Hernandez-Pineda R, Hernandez-Cruz A, et al. (1999) Contributions of Kv3 channels to neuronal excitability. Ann N Y Acad Sci 868:304–343 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saneyoshi T, Wayman G, Fortin D, Davare M, Hoshi N, Nozaki N, Natsume T, Soderling TR. (2008) Activity-dependent synaptogenesis: regulation by a CaM-kinase kinase/CaM-kinase I/betaPIX signaling complex. Neuron 57:94–107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spitzer NC, Olson E, Gu X. (1995) Spontaneous calcium transients regulate neuronal plasticity in developing neurons. J Neurobiol 26:316–324 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sweatt JD. (2001) The neuronal MAP kinase cascade: a biochemical signal integration system subserving synaptic plasticity and memory. J Neurochem 76:1–10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tahara S, Fukuda K, Kodama H, Kato T, Miyoshi S, Ogawa S. (2001) Potassium channel blocker activates extracellular signal-regulated kinases through Pyk2 and epidermal growth factor receptor in rat cardiomyocytes. J Am Coll Cardiol 38:1554–1563 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tapia R, Sitges M. (1982) Effect of 4-aminopyridine on transmitter release in synaptosomes. Brain Res 250:291–299 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tibbs GR, Dolly JO, Nicholls DG. (1989) Dendrotoxin, 4-aminopyridine, and beta-bungarotoxin act at common loci but by two distinct mechanisms to induce Ca2+-dependent release of glutamate from guinea-pig cerebrocortical synaptosomes. J Neurochem 52:201–206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X, Gruenstein EI. (1997) Mechanism of synchronized Ca2+ oscillations in cortical neurons. Brain Res 767:239–249 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wayman GA, Impey S, Marks D, Saneyoshi T, Grant WF, Derkach V, Soderling TR. (2006) Activity-dependent dendritic arborization mediated by CaM-kinase I activation and enhanced CREB-dependent transcription of Wnt-2. Neuron 50:897–909 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wayman GA, Kaech S, Grant WF, Davare M, Impey S, Tokumitsu H, Nozaki N, Banker G, Soderling TR. (2004) Regulation of axonal extension and growth cone motility by calmodulin-dependent protein kinase I. J Neurosci 24: 3786–3794 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wulff H, Castle NA, Pardo LA. (2009) Voltage-gated potassium channels as therapeutic targets. Nat Rev Drug Discov 8:982–1001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang D, Gopalakrishnan SM, Freiberg G, Surowy CS. (2010) A thallium transport FLIPR-based assay for the identification of KCC2-positive modulators. J Biomol Screen 15:177–184 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]