Abstract

Racial and ethnic health disparities in reproductive medicine exist across the life span and are costly and burdensome to our healthcare system. Reduction and ultimate elimination of health disparities is a priority of the National Institutes of Health who requires reporting of race and ethnicity for all clinical research it supports. Given the increasing rates of admixture in our population, the definition and subsequent genetic significance of self-reported race and ethnicity used in health disparity research is not straightforward. Some groups have advocated using self-reported ancestry or carefully selected single-nucleotide polymorphisms, also known as ancestry informative markers, to sort individuals into populations. Despite the limitations in our current definitions of race and ethnicity in research, there are several clear examples of health inequalities in reproductive medicine extending from puberty and infertility to obstetric outcomes. We acknowledge that socioeconomic status, education, insurance status, and overall access to care likely contribute to the differences, but these factors do not fully explain the disparities. Epigenetics may provide the biologic link between these environmental factors and the transgenerational disparities that are observed. We propose an integrated view of health disparities across the life span and generations focusing on the metabolic aspects of fetal programming and the effects of environmental exposures. Interventions aimed at improving nutrition and minimizing adverse environmental exposures may act synergistically to reverse the effects of these epigenetic marks and improve the outcome of our future generations.

Keywords: racial disparities, ancestry informative markers, admixture, infertility, transgenerational, epigenetic, developmental origins of adult disease

Racial and ethnic differences exist in all facets of reproductive medicine, from birth to menopause. Health disparities as defined by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) are differences in the overall rate of disease incidence, prevalence, mortality, morbidity, or survival rates in a population compared with the health status of the general population.1 Addressing health disparities is a priority of the NIH who established the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparity (NIMHD) in 2010 and requires reporting of race and ethnicity for all clinical research it supports.2 The NIMHD has recognized racial and ethnic minority groups as health disparity populations. However, health disparities are not just an issue for the populations that are directly affected. The health of racial and ethnic minorities will impact the health of the entire nation as these populations continue to grow and as the rate of racial diversity and mixture between racial groups increases in our population.3 Socioeconomic, education, insurance status, and overall access to care more than likely contribute to the differences. However, disparities persist even when these factors are controlled for in studies suggesting that underlying biologic, genetic, or epigenetic effects may also be at play.

Inequalities in reproductive medicine extend to infertility, preterm birth, overall care utilization, and treatment outcomes. The 2005 American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists committee opinion recognized this issue and called for the elimination of disparities with a comprehensive, multilevel strategy that would involve all members of the society.4 It should be a societal goal to resolve these disparities, as the cost of disparity is intolerably high. However, disparity in medicine has become an increasingly more divisive topic, as advances in our understanding of the human genome have brought the traditional concepts of race and ethnicity into question. Despite this controversy, there is biological plausibility for differences between groups with the recent development of ancestry informative markers (AIMs) and ongoing research into the transgenerational effects of epigenetics. Our hope is to inspire clinicians and scientists to join in the investigation of why these differences exist and how best to address them to optimize the reproductive health of future generations.

Defining Race and Ethnicity in Research

The mission of the NIMHD is ultimately to reduce and eventually eliminate health disparities through research, community outreach, and public health education.1 If we are to conduct effective research into the etiologies of disparity, we must first agree upon a definition of race and ethnicity so that results and conclusions can be compared between studies. The definition of “race” stirs controversy, as it may be viewed as a real biological entity or as a social–political construct.5 The modern concept of “race” most likely dates back to the 17th century with European imperialism and the desire to categorize and name newly encountered populations.6,7 Ethnicity is a broader category incorporating race, cultural tradition, common population history, religion, language, and often a shared genetic heritage.8 No matter one's view, currently race/ethnicity is self-reported in the vast majority of clinical studies and based on the same categories used by the US Census Bureau.2 The Executive Office of the President's Office of Management and Budget (OMB Statistical Directive No. 15) directs the collection of data on race and ethnicity. This directive emphasizes the importance of self-reporting and that the categories are based on social–political construct, not scientifically or genetically based.9

The US Census Bureau collects race data based on self-identification in accordance with guidelines provided by the US Office of Management and Budget.3 It is explicitly stated that the racial categories reflect a “social” definition and are not an attempt to define race biologically, anthropologically, or genetically. The five racial categories included in the census questionnaire and subsequently used by researchers include white, black/African American, American Indian/Alaskan Native, Asian, and Native Hawaiian/other Pacific Islander. Hispanic/Latino or non-Hispanic/Latino is designated separately as the sole ethnic category. Additionally for the first time in the 2000 US Census and continuing into 2010, individuals were allowed to report more than one race in an attempt to reflect the increasing diversity of our society.3 According to the US Census Bureau, non-Hispanic white births made up less than half of all births in the United States for the first time (46%) in the 12-month period ending in July 2011.3 Simultaneously among participants reporting only a single race, individuals reporting “black” rose 11%, “Pacific Islander” rose 25%, “Asian” grew by 32.3%, while “white” only increased by 7.1%.3 The number of people reporting “Hispanic” as an ethnicity increased to 37.1%.3 Also notably, the number of people choosing to report more than one race rose to 36.6%3 adding complexity to the modern definition of race and reflecting increasing rates of admixture in our society. These increasing rates of admixture in our population may make conclusions solely based on a strict categorization of individuals by race invalid.

Clinicians and scientists frequently use race to extrapolate an individual's ancestry and thereby predict genetic risk for disease and treatment response. Therefore, it is important to understand the limitations of using “race” as a proxy for genetic variation. Even when following the guidelines set forth by the NIH, some researchers are not able to interpret their results given the ambiguous evolving definition of race in our society. One recent qualitative study by Hunt and Megyesi interviewed genetic researchers about their methods of collecting, maintaining, and reporting racial data and found that most used race/ethnicity as an important component of study design looking at variation of disease markers.10 In qualitative interviews, the authors exposed several inconsistencies that could introduce inaccuracy into the studies. For example, none of the interviewed scientists had a systematic way to handle mixed-race participants.10 Many of the scientists responded when participants were difficult to classify that their information was excluded from data analysis.10 In pointing out that self-reporting is not always straightforward, the authors found that one of the interviewed geneticists even had difficulty classifying himself into a racial category.10 Hunt and Megyesi concluded that the current guidelines for racial/ethnic categorization especially when race is used as proxy for genetic variation are arbitrary, ambiguous, and lacking sufficient rigor.10 The authors concluded that scientists should investigate the basis of the variance and not tolerate inconsistent classifications.10

In an attempt to avoid inconsistencies resulting from self-report, recent research has been focused on attempting to categorize participants based on genetic markers. From a genomic standpoint, Homo sapiens are 99.6 to 99.8% identical to all others.11 Of the 3 million nucleotides that may vary between individuals, the majority will occur at neutral sites not contributing to phenotypic differences, while only a minority will affect gene regulation, transcription, and trans-lation.11,12 Greater than 10 million single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) have been identified in the human genome, accounting for approximately 90% of the variation.13 Several studies have assessed the frequency of SNPs and have shown that approximately 10 to 15% of the total genetic difference between humans is found between certain geographic groups (i.e., sub-Saharan Africans, Northern Europeans, and East Asians).14–16 Rosenberg et al14 were the first to show that population groups may be clustered through analysis of multiallelic microsatellite loci with high statistical accuracy. Furthermore, clustering of populations by geographic origin has been accomplished with the use of SNPs and their associated haplotypes.17 Cooper et al18 argue that population-specific alleles are unlikely to occur in medically relevant areas of the genome and they point out that the majority of genetic variation occurs within, not between, continental populations. The authors liken these microsatellite loci to a “last name” that merely serves to distinguish ancestry.18

Some groups have focused on the 10 to 15% total genetic variation to sort individuals into populations based on carefully selected SNPs, the so-called ancestry informative markers.19–21 Paschou et al demonstrated that a small panel of AIMs could be used to assign 1,043 individuals to their self-reported world-wide population of origin (51 populations represented) with a close to 100% accuracy.21 The same group showed similar results using AIMs to predict the ancestry of 1,200 individuals from 11 populations within Europe.22

AIMs may also aid researchers in understanding the contributions of admixture in populations. Parra et al investigated the correlation between ancestry, AIMs, and skin pigmentation measured by spectrometry in individuals from five admixed world-wide populations.19 In this study, the authors showed that there was a significant but variable correlation between skin pigmentation and indigenous American or West African ancestry (Puerto Rican ρ = 0.633 vs. Mexican ρ = 0.212).19 The authors explain that the variance in the correlations is likely a result of population structure due to admixture of varying pigmentation levels. Using simulation models with AIMs, they describe how the correlations between skin pigmentation and ancestry are no longer significant when the parental phenotypes are similar, or with increasing admixture in the population.19 Parra et al advocate for the use of AIMs to determine ancestry admixture rather than researchers relying on skin pigmentation to accurately reflect ancestry.19 While the use of AIMs to categorize research subjects should become increasingly more accessible and is an exciting development in the genomic era,23–25 this will add an additional layer of complexity and cost to investigations and at this time is not practical for most researchers.

With the limited feasibility of AIMs at this time and the limitations of race self-reporting, some authors have discussed using reporting of ancestry instead.11,12 Asking about ancestry allows researchers to capture more information regarding admixture and will take into account the shared population history that contributes to genetic and epigenetic differences between groups. As Keita et al5 astutely point out, the often used demographic category “African American” should not be used to refer to both the descendants of the Middle Passage Africans (i.e., descendants of African slaves in America) and recent African immigrants. We postulate that descendants of the Middle Passage Africans may still harbor epigenetic signatures from the deprivation, stress, and hardship with which their ancestors suffered. At this time focusing on ancestry, rather than race, in health disparity research may help shed some light on the etiologies of disparity.

Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Reproductive Medicine

While understanding that all studies making conclusions based on race/ethnicity are subject to limitations as elucidated above, it is hard to disagree with the evidence supporting the existence of health disparities among minority populations. Two clear examples are the epidemic of diabetes and obesity. As the rates of diabetes mellitus and obesity increase across the board in America, these diseases seem to disproportionately affect minority women. The most recent CDC data demonstrate that when compared with “white” Americans, “non-Hispanic black” Americans carry a 77% increased risk of diabetes mellitus. While these data also showed an increased risk of diabetes for “Hispanics” and “Asians” compared with “white” Americans, the most dramatic increased risk was among “non-Hispanic black” individuals.26 The prevalence of obesity is also increasing more dramatically in minority populations. The National Health and Nutritional Examination Survey data from 2008 showed that 49.6% of “non-Hispanic black” women have obesity (body mass index > 30), while the same is true for only 33% of “white” women.27 These demographic differences are of critical importance to reproductive medicine, as there is a clear association between increased body mass index, polycystic ovarian syndrome, insulin resistance, anovulation, and diabetes mellitus.

Ethnic disparities in reproductive medicine can be appreciated as early as puberty where cumulative data from several large studies have shown that, on average, African American females enter puberty 1 year sooner than white females.28 Several competing theories (hyperinsulinemia, critical body-weight, total fat mass, and toxin exposure) have been proposed to explain disparate timing of puberty.28 These theories will be discussed in greater detail in subsequent chapters. However, the significance of earlier menarche in African American women deserves mention, as several large studies have shown that early age at menarche is associated with increased risk of type 2 diabetes mellitus,29–31 obesity,29,30 hypertension,32 cardiovascular disease,32 coronary heart disease,32 all-cause mortality,32 and cancer mortality.32 The authors suggest that these effects are mediated by body mass index. We hypothesize that further research may show that the observed disparities in pubertal timing may begin as early as in utero through epigenetic mechanisms (i.e., heritable, toxin related, nutrition related) leading to development of a “thrifty phenotype” predisposing effected neonates to increased rates of obesity, early puberty, and continued metabolic consequences into adulthood which are passed on to subsequent generations.

Studies examining disparities with respect to infertility and assisted reproductive technology (ART) have also demonstrated racial differences. African American women compared with Caucasian women who present for infertility care have on average experienced a longer duration of infertility suggesting differential access to care.33,34 Sharara and McClamrock demonstrated this difference persisted (average of 1.3 more years of infertility (p = 0.16) in “black” women) even in the context of state mandated insurance coverage of infertility care.35 Of note, the authors specified that women of mixed race were excluded from their study. Differences in infertility diagnosis have also been shown with African Americans33,34,36–40 and Hispanics34,41 having higher rates of tubal factor infertility compared with white women. Several studies have also shown that these minority populations have higher rates of uterine factor infertility (e.g., fibroids).36–39 In contrast, white women were found to have higher rates of endometriosis33,38,39,41 and ovulatory dysfunction.33,38 Outcomes of ART have also been shown to vary by race with some studies reporting lower implantation rates, clinical pregnancy rates, and live birth rate for African Americans,33,35,42 while other studies have shown no difference.39,40 Interestingly, some investigators have suggested that racial differences in clinical pregnancy rate and live birth rate may resolve with the utilization of frozen cycles rather than fresh cycles.33,37 Butts and Seifer reviewed several large studies acknowledging limitations and found that race/ethnicity remained a risk factor for poor ART outcome even after adjusting for confounders.28

The obstetric literature has also demonstrated persistent racial disparities. African Americans have been shown to have higher rates of maternal mortality, increased perinatal and neonatal mortality, and increased incidence of low and very low birth weight neonates.43–47 Some have attempted to explain the difference in low birth weight as physiological rather than pathological growth restriction. Kramer et al analyzed 11.5 million singleton live births in the United States from 1998 to 2000 and found that neonatal mortality was highest for all gestational ages in US-born blacks, intermediate in foreign-born blacks, and lowest in infants born to white mothers.48 When the authors correlated small for gestational age (SGA) to neonatal mortality, they found that the gestational age-specific pattern of SGA cohered better when it was based on a single standard versus an ethnic-based standard.48 This finding supports the conclusion that differences in birth weight in the African American population are pathologic.48 A second study by Alexander et al demonstrated that the risk of SGA and infant mortality even in an “extremely low risk population” was 2.64 and 1.61 times greater for African American women, respectively, compared with white women.49 In the study by Kramer et al48 if genetic or biologic factors alone were to blame, one would expect the US-born blacks to have been at the intermediate weight/mortality reflecting their admixture. Moreover, Alexander et al49 by studying an extremely low-risk population essentially controlled for age, prenatal care, mode of delivery, and medical/social history demonstrated that given the lack of obvious risk factors in the African American population, they likely carry a transgenerational predisposition for poor outcomes.

Environmental Effects on Health Disparities

Epigenetics is the study of heritable changes in gene expression or phenotype that do not involve changes in the underlying DNA sequence. The most well-known epigenetic mechanisms involve DNA methylation and histone modification. The epigenome is able to adapt more rapidly to environmental conditions than can the genome and these modifications to gene expression last through generations.50 David Barker has done much work on this subject over the past 20 years and has fathered the theory of Developmental Origins of Health and Disease, also known as the theory of Fetal Origins of Adult Disease and the Barker hypothesis.51-53 His work focuses on the interactions between the in utero environment, predominantly malnutrition, and subsequent development of disease in the offspring. Multiple studies investigating this hypothesis have demonstrated markers of placental inflammation and alterations in fetal metabolic profile and fat mass.54-59 It is thought that subsequent metabolic syndrome and heart disease develop in the offspring because of an adaptation to a “thrifty phenotype” in utero in preparation for a world without nutrients and who instead encounter a world with plenty of nutrients. This “mismatch” concept appears to be central to the disease process and may help explain why low-birth-weight infants born to minority populations end up with higher rates of obesity and diabetes upon encountering a society reliant upon high calorie and high-fat nutritional sources.

Pembrey, using the Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children, showed a link between grandmothers' food supply and granddaughters' longevity and the same for the male line.60 The effect was sex specific and the authors postulated that the effect might be mediated through sex chromosomes.60 Mouse models have also been used to examine this concept of environmental exposures leading to phenotypic changes in multiple generations. In one model, the authors demonstrated that in utero exposure to a ubiquitous environmental contaminant, 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin (TCDD), led to decreased fertility and an increased incidence of preterm birth in F1 mice.61 They further showed that this effect lasted for three subsequent generations without direct toxin exposure clearly suggesting that ancestral exposure to the toxin led to transmission of heritable epigenetic alterations.61 In a similar study, Manikkam et al showed that in utero exposure to hydrocarbons, plastics, and dioxin led to early-onset puberty and spermatogenic cell apoptosis in three subsequent generations.62 The authors examined the sperm promoter epigenome and were able to identify differentially methylated regions of DNA in the descendants of exposed rats.62 These studies provide biologic plausibility for the transgenerational epigenetic effects of disparate environmental exposures and a possible explanation for the increased risk of adverse health outcomes in minority individuals who otherwise would be considered low risk.

We hypothesize that epigenetic effects may prove to be the biologic link between reproductive health disparity and the effects of socioeconomic status, education, and societal stress. There is abundant evidence to show that racial and ethnic minorities generally have a lower socioeconomic status compared with the white population.63-65 There is also evidence to show that minority populations tend to live in communities with social disorder, increased poverty, and differential access to healthcare resources.66,67 These societal disparities alone do not seem to explain the differences seen in health outcomes. One study investigating a transgenerational dataset of African Americans found that women with early life impoverishment who achieved upward economic mobility had a decreased incidence of preterm birth compared with women with life-long impoverishment.68 However, this effect was not seen in women with upward economic mobility who had themselves been low birth weight, suggesting a possible transgenerational epigenetic effect that could not be overcome with a change in socioeconomic status.68 In a similar example, when infants born to college-educated parents were assessed, the rate of infant mortality was two times higher in non-Hispanic black infants compared with non-Hispanic white infants despite controlling for education.69

One longitudinal model that may go farther than any other in an attempt to explain the complexities of racial and ethnic disparities in reproductive medicine is the “life-course perspective.”70 This model takes into account not only fetal origins of disease (as previously discussed) but also cumulative wear and tear leading to differential health trajectories affecting reproductive potential. The authors discuss that most studies with focus on assessing the etiology of racial and ethnic disparities in birth outcomes examine exposures during pregnancy. They astutely point out that several studies looking at the effects of socioeconomic status, behavioral risk factors, inadequate prenatal care, stressful life events, and current maternal infections have shown that these factors examined during pregnancy alone do not explain the disparities seen.

Studies of the “cumulative pathway mechanism” have shown hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis hyperactivity in animals and humans subjected to chronic stress.71,72 The authors hypothesize biologic plausibility for HPA axis hyperactivity leading to immune-inflammatory dysregulation and increased risk for cardiovascular disease, autoimmune disorders, and preterm birth/low birth weight.70 In support of this hypothesis, the authors cite a study by Stein et al73 who investigated a cohort of homeless women and found a stronger association between severity of homeless-ness (i.e., the number of times homeless and the percentage of life spent homeless) with low birth weight and preterm birth than with being homeless in the index pregnancy. Using a synthesis of the early programming model and the cumulative pathway model, the authors describe how different health trajectories develop over the life span resulting from exposure to risk and protective factors at sensitive times.70 The authors call for more longitudinal research linking different stages of life, from one pregnancy to the next, and across generations.70

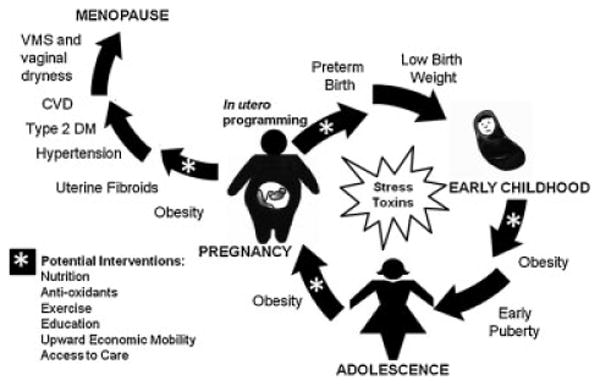

We would build on this longitudinal model and emphasize the metabolic consequences of poor nutrition, type 2 diabetes mellitus, and obesity, as it relates to in utero programming and exertion of subsequent transgenerational effects (▸Fig. 1). In addition to fetal origins of disease, we acknowledge that socioeconomic status, societal stress, disparate exposures to environmental toxins, education, and access to care also influence reproductive health. We propose an integrated view of health disparities across the life span and across generations focusing on the metabolic aspects of fetal programming and the effects of environmental exposures. As previously stated, it is known that women from minority populations have improved reproductive outcomes with upward economic mobility and increased levels of education and we would advocate for societal efforts to improve these factors in minority populations. Moreover, we would also advocate for far-reaching changes to nutritional societal norms, namely, an improvement to access and acceptance of nutritious food sources.

Figure 1.

Health disparities affect women across the life-span and may be propagated in a transgenerational cycle. Obesity and metabolic alterations in pregnancy, in addition to transgenerational inheritance of epigenetic marks, lead to in utero programming. These epigenetic changes cause placental abnormalities including expression of inflammatory markers leading to preterm birth and low birth weight. Inheritance of the “thrifty phenotype” predisposes offspring to obesity and early puberty. Metabolic alterations leading to increased rates of obesity and diabetes persist through adolescence and into adulthood when that offspring will enter motherhood starting the cycle again and passing along the same epigenetic marks to the next generation. Postpubertal health disparities also include increased rates of uterine fibroids, type 2 diabetes mellitus (DM), hypertension, cardiovascular disease (CVD), and vasomotor symptoms (VMS), as well as vaginal dryness in menopause. We propose potential interventions (indicated by asterisks) along the lifespan including improved nutrition, antioxidants, exercise, education, upward economic mobility, and increased access to care that synergistically may help resolve this transgenerational cycling of persistent health disparities.

Recent work has demonstrated the possibility that diet may resolve toxicant-induced epigenetic changes. McConaha et al showed that adult male mice exposed in utero to a ubiquitous environmental toxicant, TCDD, confer an increased risk of preterm birth to unexposed females who demonstrate a placental inflammatory response related to altered expression of messenger RNA.74 The authors were able to demonstrate that the placental inflammatory response and thus preterm birth could be prevented with a paternal preconception diet consisting of omega-3 fatty acids.74 These data provide hope that an integrated and longitudinal view of health disparities including a focus on nutrition in research may help us in understanding the etiology of disparity as well as recognize ways to improve reproductive outcomes.

Cost of Health Disparities

Healthcare disparities are expensive. In a 2009 report commissioned by the Joint Center of Economic and Political Studies, LaVeist et al estimated that 30.6% of direct medical care expenditures between 2003 and 2006 for African Americans, Asian Americans, and Hispanics were excess costs secondary to health inequalities.75 This excess accounted for an estimated $229.4 billion.75 In a separate study, Zhang et al used a cross-sectional study design to investigate pregnancy outcomes and associated cost among Medicaid recipients in 14 southern US states.76 The authors found that African American women were significantly more likely to experience adverse pregnancy outcomes (e.g., preeclampsia, placental abruption, preterm birth, small for birth size for gestational, and fetal death) as compared with other racial/ethnic groups.76 They estimated that elimination of this health disparity (not accounting for related neonatal costs) could generate $114 to 214 million per year in Medicaid savings in these 14 states.76 These two studies emphasize that health disparities are not only affecting individual populations but are also costly and burdensome to our entire US healthcare system. These data demonstrate that long-term investments in women's health could yield great returns in the health of future generations and reduce costly disparities.

Conclusions

Despite limitations in our current paradigm for racial categorization, the literature firmly supports the existence of racial and ethnic health disparities that are costly to our US healthcare system. The etiology of these disparities is poorly understood and research with a fresh perspective aimed at identifying the cause of these disparities is urgently needed. Self-reporting by research participants into racial categories has been shown to be inconsistent and needs to be revised to account for increasing rates of admixture. Possible approaches would be to replace our current system with the use of AIMs or with self-report of ancestry and ethnic identity, either of which would more effectively capture the influence of admixture. Moving forward, research studies on health disparities also need to utilize a longitudinal approach, understanding the transgenerational predisposition of risk factors as well as the effect of environmental exposures and nutrition on reproductive outcomes. With new methods, we may be able to identify interventions that can curb the tide of these transgenerational effects and improve the outcome of our future generations.

References

- 1.National Institutes of Health. Bethesda, MD: National Institutes of Health; 2011. [Accessed February 12, 2013]. NIH Health Disparities Strategic Plan and Budget, Fiscal Years 2009-2013. [Online]. Available at: http://www.nimhd.nih.gov/about_ncmhd/Strategic%20Plan%20FY%202009-2013%20rev%20080212.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 2.National Institutes of Health. Bethesda, MD: National Institutes of Health; 2011. [Accessed February 12, 2013]. NIH Policy on Reporting Race and Ethnicity Data: Subjects in Clinical Research. [Online]. Available at: http://grants.nih.gov\grants\guide\notice-files\NOT-OD-01-053.html. [Google Scholar]

- 3.U.S. Census Bureau. Statistical Abstract of the United States. 131st. Washington, DC: US Government printing office; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 4.ACOG Committee on Health Care for Underdeserved Women. ACOG committee opinion. Number 317, October 2005. Racial and ethnic disparities in women's health. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;106(4):889–892. doi: 10.1097/00006250-200510000-00053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Keita SO, Kittles RA, Royal CD, et al. Conceptualizing human variation. Nat Genet. 2004;36(11, Suppl):S17–S20. doi: 10.1038/ng1455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brace CL. “Race” Is a Four-Letter Word: The Genesis of the Concept. New York: Oxford University Press; 2005. p. 326. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Montagu A. The concept of race. Am Anthropol. 1962;64:919–928. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Burchard EG, Ziv E, Coyle N, et al. The importance of race and ethnic background in biomedical research and clinical practice. N Engl J Med. 2003;348(12):1170–1175. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsb025007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Executive Office of the President; Office of Management and Budget (OMB); Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs. Recommendations from the Interagency Committee for the Review of the Racial and Ethnic Standards to the Classification of Federal Data on Race and Ethnicity. Washington, DC; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hunt LM, Megyesi MS. The ambiguous meanings of the racial/ethnic categories routinely used in human genetics research. Soc Sci Med. 2008;66(2):349–361. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.08.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bamshad M. Genetic influences on health: does race matter? JAMA. 2005;294(8):937–946. doi: 10.1001/jama.294.8.937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tishkoff SA, Kidd KK. Implications of biogeography of human populations for ‘race’ and medicine. Nat Genet. 2004;36(11, Suppl):S21–S27. doi: 10.1038/ng1438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.International HapMap Consortium. The international HapMap project. Nature. 2003;426(6968):789–796. doi: 10.1038/nature02168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rosenberg NA, Pritchard JK, Weber JL, et al. Genetic structure of human populations. Science. 2002;298(5602):2381–2385. doi: 10.1126/science.1078311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bamshad MJ, Wooding S, Watkins WS, Ostler CT, Batzer MA, Jorde LB. Human population genetic structure and inference of group membership. Am J Hum Genet. 2003;72(3):578–589. doi: 10.1086/368061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bamshad M, Wooding S, Salisbury BA, Stephens JC. Deconstructing the relationship between genetics and race. Nat Rev Genet. 2004;5(8):598–609. doi: 10.1038/nrg1401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stephens JC, Schneider JA, Tanguay DA, et al. Haplotype variation and linkage disequilibrium in 313 human genes. Science. 2001;293(5529):489–493. doi: 10.1126/science.1059431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cooper RS, Kaufman JS, Ward R. Race and genomics. N Engl J Med. 2003;348(12):1166–1170. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsb022863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Parra EJ, Kittles RA, Shriver MD. Implications of correlations between skin color and genetic ancestry for biomedical research. Nat Genet. 2004;36(11, Suppl):S54–S60. doi: 10.1038/ng1440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Raska P, Iversen E, Chen A, et al. European American stratification in ovarian cancer case control data: the utility of genome-wide data for inferring ancestry. PLoS ONE. 2012;7(5):e35235. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0035235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Paschou P, Lewis J, Javed A, Drineas P. Ancestry informative markers for fine-scale individual assignment to worldwide populations. J Med Genet. 2010;47(12):835–847. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2010.078212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Drineas P, Lewis J, Paschou P. Inferring geographic coordinates of origin for Europeans using small panels of ancestry informative markers. PLoS ONE. 2010;5(8):e11892. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0011892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kosoy R, Nassir R, Tian C, et al. Ancestry informativemarker sets for determining continental origin and admixture proportions in common populations in America. Hum Mutat. 2009;30(1):69–78. doi: 10.1002/humu.20822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Amirisetty S, Hershey GK, Baye TM. AncestrySNPminer: a bioinformatics tool to retrieve and develop ancestry informative SNP panels. Genomics. 2012;100(1):57–63. doi: 10.1016/j.ygeno.2012.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Halder I, Shriver M, Thomas M, Fernandez JR, Frudakis T. A panel of ancestry informative markers for estimating individual bio-geographical ancestry and admixture from four continents: utility and applications. Hum Mutat. 2008;29(5):648–658. doi: 10.1002/humu.20695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cowie CC, Rust KF, Ford ES, et al. Full accounting of diabetes and pre-diabetes in the U.S. population in 1988-1994 and 2005-2006. Diabetes Care. 2009;32(2):287–294. doi: 10.2337/dc08-1296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Atlanta, GA: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Butts SF, Seifer DB. Racial and ethnic differences in reproductive potential across the life cycle. Fertil Steril. 2010;93(3):681–690. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2009.10.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lakshman R, Forouhi N, Luben R, et al. Association between age at menarche and risk of diabetes in adults: results from the EPIC-Norfolk cohort study. Diabetologia. 2008;51(5):781–786. doi: 10.1007/s00125-008-0948-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.He C, Zhang C, Hunter DJ, et al. Age at menarche and risk of type 2 diabetes: results from 2 large prospective cohort studies. Am J Epidemiol. 2010;171(3):334–344. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwp372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pierce MB, Kuh D, Hardy R. The role of BMI across the life course in the relationship between age at menarche and diabetes, in a British Birth Cohort. Diabet Med. 2012;29(5):600–603. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2011.03489.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lakshman R, Forouhi NG, Sharp SJ, et al. Early age at menarche associated with cardiovascular disease and mortality. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2009;94(12):4953–4960. doi: 10.1210/jc.2009-1789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Seifer DB, Frazier LM, Grainger DA. Disparity in assisted reproductive technologies outcomes in black women compared with white women. Fertil Steril. 2008;90(5):1701–1710. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2007.08.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jain T. Socioeconomic and racial disparities among infertility patients seeking care. Fertil Steril. 2006;85(4):876–881. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2005.07.1338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sharara FI, McClamrock HD. Differences in in vitro fertilization (IVF) outcome between white and black women in an inner-city, university-based IVF program. Fertil Steril. 2000;73(6):1170–1173. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(00)00524-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Feinberg EC, Larsen FW, Catherino WH, Zhang J, Armstrong AY. Comparison of assisted reproductive technology utilization and outcomes between Caucasian and African American patients in an equal-access-to-care setting. Fertil Steril. 2006;85(4):888–894. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2005.10.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Csokmay JM, Hill MJ, Maguire M, Payson MD, Fujimoto VY, Armstrong AY. Are there ethnic differences in pregnancy rates in African-American versus white women undergoing frozen blastocyst transfers? Fertil Steril. 2011;95(1):89–93. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2010.03.050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Luke B, Brown MB, Stern JE, Missmer SA, Fujimoto VY, Leach R. Racial and ethnic disparities in assisted reproductive technology pregnancy and live birth rates within body mass index categories. Fertil Steril. 2011;95(5):1661–1666. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2010.12.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dayal MB, Gindoff P, Dubey A, et al. Does ethnicity influence in vitro fertilization (IVF) birth outcomes? Fertil Steril. 2009;91(6):2414–2418. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2008.03.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bendikson K, Cramer DW, Vitonis A, Hornstein MD. Ethnic background and in vitro fertilization outcomes. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2005;88(3):342–346. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2004.11.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shuler A, Rodgers AK, Budrys NM, Holden A, Schenken RS, Brzyski RG. In vitro fertilization outcomes in Hispanics versus non-Hispanic whites. Fertil Steril. 2011;95(8):2735–2737. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2011.04.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Seifer DB, Zackula R, Grainger DA. Society for Assisted Reproductive Technology Writing Group Report. Trends of racial disparities in assisted reproductive technology outcomes in black women compared with white women: Society for Assisted Reproductive Technology 1999 and 2000 vs 2004-2006. Fertil Steril. 2010;93(2):626–635. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2009.02.084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Poole JH, Long J. Maternal mortality—a review of current trends. Crit Care Nurs Clin North Am. 2004;16(2):227–230. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2004.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Davidson EC, Jr, Fukushima T. The racial disparity in infant mortality. N Engl J Med. 1992;327(14):1022–1024. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199210013271409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Alexander GR, Tompkins ME, Allen MC, Hulsey TC. Trends and racial differences in birth weight and related survival. Matern Child Health J. 1999;3(2):71–79. doi: 10.1023/a:1021849209722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Luke B, Murtaugh M. The racial disparity in very low birth weight. N Engl J Med. 1993;328(4):285–286. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199301283280415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Frisbie WP, Song SE, Powers DA, Street JA. The increasing racial disparity in infant mortality: respiratory distress syndrome and other causes. Demography. 2004;41(4):773–800. doi: 10.1353/dem.2004.0030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kramer MS, Ananth CV, Platt RW, Joseph KS. US Black vs White disparities in foetal growth: physiological or pathological? Int J Epidemiol. 2006;35(5):1187–1195. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyl125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Alexander GR, Kogan MD, Himes JH, Mor JM, Goldenberg R. Racial differences in birthweight for gestational age and infant mortality in extremely-low-risk US populations. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 1999;13(2):205–217. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3016.1999.00174.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Stöger R. The thrifty epigenotype: an acquired and heritable predisposition for obesity and diabetes? Bioessays. 2008;30(2):156–166. doi: 10.1002/bies.20700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Barker DJ. The long-term outcome of retarded fetal growth. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 1997;40(4):853–863. doi: 10.1097/00003081-199712000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Dennison E, Fall C, Cooper C, Barker D. Prenatal factors influencing long-term outcome. Horm Res. 1997;48(Suppl 1):25–29. doi: 10.1159/000191262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Roseboom TJ, van der Meulen JH, Osmond C, et al. Coronary heart disease after prenatal exposure to the Dutch famine, 1944-45. Heart. 2000;84(6):595–598. doi: 10.1136/heart.84.6.595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Taricco E, Radaelli T, Rossi G, et al. Effects of gestational diabetes on fetal oxygen and glucose levels in vivo. BJOG. 2009;116(13):1729–1735. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2009.02341.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Catalano PM, Thomas A, Huston-Presley L, Amini SB. Increased fetal adiposity: a very sensitive marker of abnormal in utero development. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2003;189(6):1698–1704. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(03)00828-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Catalano PM, Farrell K, Thomas A, et al. Perinatal risk factors for childhood obesity and metabolic dysregulation. Am J Clin Nutr. 2009;90(5):1303–1313. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2008.27416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Aagaard-Tillery KM, Grove K, Bishop J, et al. Developmental origins of disease and determinants of chromatin structure: maternal diet modifies the primate fetal epigenome. J Mol Endocrinol. 2008;41(2):91–102. doi: 10.1677/JME-08-0025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Cox J, Williams S, Grove K, Lane RH, Aagaard-Tillery KM. A maternal high-fat diet is accompanied by alterations in the fetal primate metabolome. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2009;201(3):e1–e9. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2009.06.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Challier JC, Basu S, Bintein T, et al. Obesity in pregnancy stimulates macrophage accumulation and inflammation in the placenta. Placenta. 2008;29(3):274–281. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2007.12.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Pembrey ME. Male-line transgenerational responses in humans. Hum Fertil (Camb) 2010;13(4):268–271. doi: 10.3109/14647273.2010.524721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Bruner-Tran KL, Osteen KG. Developmental exposure to TCDD reduces fertility and negatively affects pregnancy outcomes across multiple generations. Reprod Toxicol. 2011;31(3):344–350. doi: 10.1016/j.reprotox.2010.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Manikkam M, Guerrero-Bosagna C, Tracey R, Haque MM, Skinner MK. Transgenerational actions of environmental compounds on reproductive disease and identification of epigenetic biomarkers of ancestral exposures. PLoS ONE. 2012;7(2):e31901. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0031901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Burns PG. Reducing infant mortality rates using the perinatal periods of risk model. Public Health Nurs. 2005;22(1):2–7. doi: 10.1111/j.0737-1209.2005.22102.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Cai J, Hoff GL, Dew PC, Guillory VJ, Manning J. Perinatal periods of risk: analysis of fetal-infant mortality rates in Kansas City, Missouri. Matern Child Health J. 2005;9(2):199–205. doi: 10.1007/s10995-005-4909-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Gennaro S. Overview of current state of research on pregnancy outcomes in minority populations. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;192(5, Suppl):S3–S10. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2005.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Giscombé CL, Lobel M. Explaining disproportionately high rates of adverse birth outcomes among African Americans: the impact of stress, racism, and related factors in pregnancy. Psychol Bull. 2005;131(5):662–683. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.131.5.662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Macera C, Armstead C, Anderson N. Sociocultural influences on health. In: Baum A, Revenson TA, Singer JE, editors. Handbook of Health Psychology. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum; 2001. pp. 427–440. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Collins JW, Jr, Rankin KM, David RJ. African American women's lifetime upward economic mobility and preterm birth: the effect of fetal programming. Am J Public Health. 2011;101(4):714–719. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2010.195024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Schoendorf KC, Hogue CJ, Kleinman JC, Rowley D. Mortality among infants of black as compared with white college-educated parents. N Engl J Med. 1992;326(23):1522–1526. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199206043262303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Lu MC, Halfon N. Racial and ethnic disparities in birth outcomes: a life-course perspective. Matern Child Health J. 2003;7(1):13–30. doi: 10.1023/a:1022537516969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Sapolsky RM. Social subordinance as a marker of hypercortisolism. Some unexpected subtleties. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1995;771:626–639. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1995.tb44715.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Kristenson M, Kucinskienë Z, Bergdahl B, Calkauskas H, Urmonas V, Orth-Gomér K. Increased psychosocial strain in Lithuanian versus Swedish men: the LiVicordia study. Psychosom Med. 1998;60(3):277–282. doi: 10.1097/00006842-199805000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Stein JA, Lu MC, Gelberg L. Severity of homelessness and adverse birth outcomes. Health Psychol. 2000;19(6):524–534. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.McConaha ME, Ding T, Lucas JA, Arosh JA, Osteen KG, Bruner-Tran KL. Preconception omega-3 fatty acid supplementation of adult male mice with a history of developmental 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin exposure prevents preterm birth in unexposed female partners. Reproduction. 2011;142(2):235–241. doi: 10.1530/REP-11-0070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.LaVeist TA, Gaskin DJ, Richard P. The Economic Burden of Health Inequities in the United States. Washington, DC: Joint Center for the Political and Economic Studies; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Zhang S, Cardarelli K, Shim R, Ye J, Booker KL, Rust G. Racial disparities in economic and clinical outcomes of pregnancy among Medicaid recipients. Matern Child Health J. 2012 doi: 10.1007/s10995-012-1162-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]