Abstract

HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders (HAND) describes different levels of neurocognitive impairment, which are a common complication of HIV infection. The most severe of these, HIV-associated dementia (HIV D), has decreased in incidence since the introduction of combination antiretroviral therapy (cART), while an increase in the less severe, minor neurocognitive disorder (MND), is now seen. The neuropathogenesis of HAND is not completely understood, however macrophages (MΦ)s/microglia are believed to play a prominent role in the development of the more severe HIV-D. Here, we report evidence of neuroinflammation in autopsy tissues from patients with HIV infection and varying degrees of neurocognitive impairment but without HIV encephalitis (HIVE). MΦ/microglial and astrocyte activation is less intense but similar to that seen in HIVE, one of the neuropathologies underlying HIV-D. MΦs and microglia appear to be activated, as determined by CD163, CD16 and HLA-DR expression, many having a rounded or ramified morphology with thickened processes, classically associated with activation. Astrocytes also show considerable morphological alterations consistent with an activated state and have increased expression of GFAP and vimentin, as compared to seronegative controls. Interestingly, in some areas, astrocyte activation appears to be limited to perivascular locations, suggesting events at the blood-brain barrier may influence astrocyte activity. In contrast to HIVE, productive HIV infection was not detectable by tyramide signal-amplified immunohistochemistry or in situ hybridization in the CNS of HIV infected persons without encephalitis. These findings suggest significant CNS inflammation, even in the absence of detectable virus production, is a common mechanism between the lesser and more severe HIV-associated neurodegenerative disease processes and supports the notion that MND and HIV-D are a continuum of the same disease process.

Introduction

HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders (HAND) is an umbrella term that describes three levels of neurocognitive dysfunction in HIV infection. The most severe of these, HIV-associated dementia (HIV-D), is characterized by acquired deficits in at least two neurocognitive domains and is associated with motor or behavioral abnormalities that result in functional impairment in work and activities of daily life (ADL). Prior to the introduction of combination antiretroviral therapy (cART), HIV-D was a frequent complication of AIDS. The use of cART has decreased the incidence of HIV-D dramatically, however, the frequencies of the less severe, minor neurocognitive disorder (MND) and the subclinical, asymptomatic neurocognitive impairment (ANI), are increased and estimated to effect as many as 50% of individuals infected with HIV, even among those with long-standing virus suppression [1]. Further, the severity of one of the neuropathological correlates of HIV-D, HIV encephalitis (HIVE), is considerably attenuated in the cART era, with a marked reduction in the number and size of perivascular cuffs and nodular lesions, as well as decreased virus production, in the CNS [1-3].

While the neuropathogenesis of HAND is not completely understood, extensive studies have demonstrated a significant role of monocyte/macrophage (MΦ) accumulation and HIV-1 replication within the CNS compartment in the development and progression of HIV-D and HIVE (for review, see Fischer-Smith and Rappaport, 2005 [4]). These findings are further supported by the significant decrease in the incidence of HIVD with the introduction of cART, suggesting that reduced virus replication and restored immune function reduces the risk for acquiring HIV-related CNS disease. Nevertheless, HAND remains a common complication of HIV infection and the pathogenic mechanisms involved remain unclear, particularly with mild to moderate impairment. Whether the lesser degrees of neurocognitive dysfunction in HIV infection represent distinct pathologies or a continuum of the same disease process that progressed to HIV-D in some individuals also remains an important question in the field.

Unlike HIV-D, a neuropathological correlate for MND and ANI has not yet been identified. Previously, MΦ/microglial activation was revealed by CD68 and MHC class II immunopositivity in the hippocampus and basal ganglia (BG) of cART-treated subjects without HIVE that was similar to activation in HIVE [3]. These findings suggested that neuroinflammation, which is significant in HIV-D and HIVE, may also play a role in less severe forms of HAND. To begin to understand the pathogenic mechanisms involved in HAND, we investigated autopsy frontal white matter (FWM) and BG tissue from cART-treated HIV infected persons without encephalitis for MΦ/microglial and astrocyte activation markers that provide additional insights into their activation and have previously been shown to be significant to HIVE pathogenesis [5-8]. Subjects studied also include those with HIVE, three of whom were treated with cART, and seronegative individuals. Here, we report similar immune activation in autopsy brain tissue from cART-treated patients with HIV infection with and without encephalitis, with some distinct differences in frequency, intensity and location. Further, neuropsychological testing revealed neurocognitive impairment among the majority of the HIV infected subjects studied. These data support the hypothesis that chronic inflammation of the brain is a common feature in HIV infection in the post-cART era, and likely plays a key role in the pathogenesis of HAND.

Materials and Methods

Human Brain Tissues

Formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded frontal white matter (FWM) and basal ganglia (BG) tissues from patients with HIVE, HIV infection without encephalitis, and seronegative individuals without CNS disease were obtained from the Manhattan HIV Brain Bank, member of the National NeuroAIDS Tissue Consortium (U24MH100931). Patients on and off cART at the time of death were included (Table 1). A total of 8 HIVE, 10 HIV infection without encephalitis or other apparent CNS disease and 5 seronegative cases were analyzed.

Table I.

Human Subjects

| PID | Class | Age | Sex | Race | CD4 | VL (copies/ml) | cART at death | Cog status |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 500 | HIVE | 47 | m | w | 20 | 210000 | none | HIV-D |

| 537 | HIVE | 45 | f | b | 6 | n/a | none | n/a |

| 603 | HIVE | 49 | m | b | 2 | 493381 | none | HIV-D |

| 10017 | HIVE | 44 | m | w | 7 | 389120 | none | npi-o |

| 10070 | HIVE | 37 | m | b | 1 | >750000 | none | ms change |

| 10133 | HIVE | 48 | m | w | 3 | 173921 | d4t, kaletra, nevirapine | MCMD po |

| 540 | HIVE | 47 | m | b | 1 | 683333 | d4t, epivir, sustiva | psychosis |

| 10231 | HIVE | 47 | m | h | 98 | 208516 | tenofovir, epivir, videx, reyataz, norvir | n/a |

| 10016 | HIV+/no E | 58 | f | b | 98 | 576000 | none | MCMD pr |

| 10066 | HIV+/no E | 54 | f | b | 8 | 469163 | none | MCMD po |

| 10011 | HIV+/no E | 44 | m | h | 16 | 162642 | none | MCMD po |

| 10119 | HIV+/no E | 33 | m | b | 1 | 312240 | none | HIV-D po |

| 10203 | HIV+/no E | 44 | f | h | 86 | 36035 | none | npi-o |

| 10067 | HIV+/no E | 28 | m | A | 5 | 2097 | epivir, nelfinavir, effavirenz, tenofovir | MCMD pr |

| 10013 | HIV+/no E | 33 | m | w | 9 | >750000 | videx, abacavir, ritonavir, indinavir | MCMD pr |

| 10001 | HIV+/no E | 64 | f | b | 72 | 359 | d4t, epivir, kaletra | HIV-D po |

| 30024 | HIV+/no E | 43 | m | b | 104 | <50 | epivir, kaletra, hydroxyurea | MCMD po |

| 10127 | HIV+/no E | 39 | f | h | 402 | 1013 | trizivir | npi-o |

| 551 | HIV− | 30 | f | h | - | - | - | n/a |

| 567 | HIV− | 63 | m | h | - | - | - | n/a |

| 588 | HIV− | 21 | m | h | - | - | - | n/a |

| 594 | HIV− | 57 | f | w | - | - | - | n/a |

| 601 | HIV− | 58 | f | h | - | - | - | n/a |

Autopsy frontal white matter (FWM) and basal ganglia (BG) from of 8 HIVE, 10 HIV without encephalitis (HIV+/no E) and 5 seronegative (HIV−) individuals without CNS disease were investigated. All tissues were acquired through the Manhattan HIV Brain Bank (MHBB) NeuroAIDS Tissue Consortium. Neurocognitive diagnoses were assigned by a licensed neuropsychologist of the MHBB. Diagnoses were assigned according to the DANA modification of the American Academy of Neurology (AAN) criteria, which includes to degrees of HIV-related neurocognitive impairment, HIV-associated dementia (HIV-D) and minor cognitive motor disorder (MCMD). The mean age for each grouping are as follows: HIVE = 45.5 years; HIV+/no E = 44 years; HIV− = 45.8 years. “Cog status” refers to the neuropsychological classification diagnosed in life, while “Class” reflects post-mortem CNS findings. Inconsistencies between these two classifications underscores the difficulty in accurately diagnosing these patients. Abbreviations: HIV-D = HIV-associated dementia; MCMD = minor cognitive motor disorder; ms change = mental status change: patient has altered cognitive capacity, however, the individual observing this is unsure if this constitutes dementia or a transient abnormality; pr = probable: no confounds; po = possible: confounds exist, but observer believes cognitive impairment is most likely HIV-associated; npi-o = neuropsychological impairment-other: patient is cognitively impaired and the observer believes there are enough ancillary factors/co-morbid processes to account for the dementia.

Neurocognitive diagnostic procedures

Neurocognitive diagnoses were assigned by a licensed neuropsychologist of the MHBB. Diagnoses of HIV-associated dementia (HIV-D), minor cognitive motor disorder (MCMD), and normal cognition were assigned according to the DANA modification of the American Academy of Neurology (AAN) criteria [9, 10]. AAN requires impaired cognition in at least two domains, neurological abnormalities or decline in motivation, behavior, or emotional control, and related impairment in functional status. “Possible” and “probable” specifiers were applied to all cases, as outlined in the criteria. A diagnosis of neuropsychological impairment-other (NPI-O) was assigned when participants presented with pre-existing or co-morbid condition that more possibly accounted for the observed cognitive impairment (e.g., stroke, urine toxicology positive for illicit substances). The neuropsychological test battery, upon which diagnoses were based, assessed a broad range of cognitive abilities sensitive to HIV impairment, including speed of information processing, fine motor speed, working memory, learning, memory, executive functioning and verbal fluency [11].

Immunohistochemistry

Immunohistochemistry was performed as described by us previously [6-8]. Briefly, deparaffinized and rehydrated 4μm brain tissue sections underwent high heat non-enzymatic antigen retrieval, followed by blocking and overnight incubation with primary mouse monoclonal antibodies. Primary antibodies included CD16 (1:40; Vector, clone 2H7), CD163 (1:100; Vector, clone 10D6), CD68 (1:50; Dako, clone KP1), Ki67 (1:25; Novacastra, clone Mm1), HLA-DR (1:100; Dako, clone Tal.1B5), HIVp24 (1:5; Dako, clone Kal-1), GFAP (1:100; Dako, clone 6F2) and vimentin (1:25; Abcam, clone EPR3776). Positive control tissues included autopsy lymph node, liver or small intestine from seronegative or HIV-1 infected individuals. Negative controls consisted of isotype antibodies used in place of the primary and tissues incubated in buffer without primary antibody. Primary antibodies were detected with biotinylated anti-mouse secondary antibodies, avidin-biotin complex and alkaline phosphatase, followed by incubation with Vector Red substrate, according to the manufacturer's instructions (Vectastain ABC AP Kit; Vector Laboratories). A tyramide signal amplification (TSA) method was used (Renaissance TSA Biotin System, Perkin Elmer) for detection of CD163, Ki-67 and HIV-1 p24, following the manufacturer's instructions. Following a light counterstain with haematoxylin, sections were dehydrated and coverslipped with Permount.

In-situ hybridization

HIV in-situ hybridization was performed as described by us previously [8]. Briefly, following deparaffinization and rehydration, tissues were permeabilized with proteinase K (Dako) and washed in diethylpyrocarbonate (DEPC)-treated PBS. Afterwards, tissues were post-fixed, quenched of endogenous peroxidase, and acetylated. Slides were washed between treatments using DEPC-treated PBS. Tissues were pre-hybridized by incubating with mRNA hybridization solution (Dako) at 45°C for one hour, followed by hybridization with 10ng HIV sense or α-sense digoxigenin (DIG)-labeled “whole genome” RNA probe (Lofstrand Labs, Ltd.) at 45°C overnight. Following overnight incubation, tissues were placed through a series of stringent washes and exposed to 20μg/ml RNase A. Detection of the probe was accomplished using a hydrogen peroxidase labeled antibody against DIG, followed by TSA (GenPoint Kit, Dako) per the manufacturer's instructions.

Scoring of tissues

Immunostained CNS tissues were scored by two observers (ET, DM or PS and TFS), independently. A score of 0-4 was assigned to each section after the observation of a minimum of 10 microscopic fields at 40X objective magnification and was based on a qualitative average of the number of immunostained cellular profiles. Positivity for each antigen of interest was subjectively graded on a scale from 0-4. A score of “0” denotes typical expression frequency and/or intensity of a normally expressed antigen (e.g., CD163). A “negative” score signifies the absence of the specified antigen. Differences in the scoring by the two observers were resolved by reviewing the blinded slides together through a double-headed microscope.

Statistics

The number of CD16+ and CD68+ cells in brain tissue (FWM and BG) was determined for each case by averaging the number of positive cells observed over 10 random microscopic fields at 200× magnification. Data were obtained using two independent observers (ET and TFS) for a total of 20 microscopic fields (field of view = 0.7mm). The mean of the two averages was accepted as the average number of CD16+ and CD68+ cells per field for each case. Levene's test was applied to assess the assumption that the variances between the groupings are equal. Student's t-test was then used to compare the mean CD68+ and CD16+ microglia frequencies between HIV+/no E and HIVE subjects.

Results

Significant MΦ/microglial accumulation and activation is seen in the brains of HIV infected persons without encephalitis

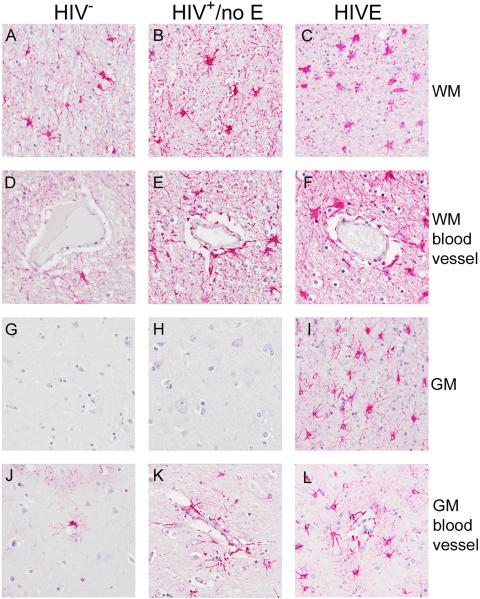

Immunohistochemical analyses of frontal white matter (FWM) and basal ganglia (BG) tissues from human subjects with HIVE, HIV infection without encephalitis (HIV+/no E) and seronegative individuals without CNS disease, revealed significant accumulation of MΦs/microglia in HIVE and HIV+/no E, as compared to control tissues, revealed by CD68 immunopositivity (not shown). The number of CD68+ cells in the FWM and BG was determined as described above, and then the mean of the observed averages was accepted as the mean CD68+ microglia per field for each case. No significant differences between the means of the two groups, HIV+/no E and HIVE, were noted, as determined by Student's t-test (Figure 1). The staining may reflect trafficking of monocytes/MΦs from the peripheral blood into the CNS compartment and/or up-regulation of CD68 expression by resident microglia, suggestive of immune activation in the CNS of HIV+/no E subjects. There was an absence of Ki-67 immunopositivity in the CNS, supporting the notion that increases in CD68+ cells in the CNS were not due to local MΦ/microglial proliferation (not shown).

Figure 1. CD68+ and CD16+ microglia frequency in the CNS of HIV infected subjects with and without encephalitis.

The number of CD68+ or CD16+ microglia in FWM and BG was determined for each case by averaging the number of positive cells observed over 10 random microscopic fields at 200X magnification by two independent observers for a total of 20 microscopic fields. The mean of the two averages was accepted as the average number of CD68+ or CD16+ microglia per field for each case. Assuming equal variances, as verified by Levene's test, the relationship of the means for the two groups, HIV+/no E and HIVE, was determined by the Independent Samples t-test (GNU PSPP). The average frequency of CD68+ microglia in FWM and BG of patients with HIV infection was similar, regardless of the presence or absence of encephalitis. The difference in the average frequency of CD16+ microglia, however, does approach significance between the two groups (p=0.06), suggesting that while the number of microglia may be similar in HIV infected persons with and without encephalitis, the degree of MΦ/microglial activation is greater in those with HIVE. It is important to note, that the mean CD68+ or CD16+ cell frequency reported here for HIVE subjects may be less than actual, as cells that accumulated perivascularly (cuffs) and within nodular lesions, where it was difficult to determine a single cell border, were counted as one.

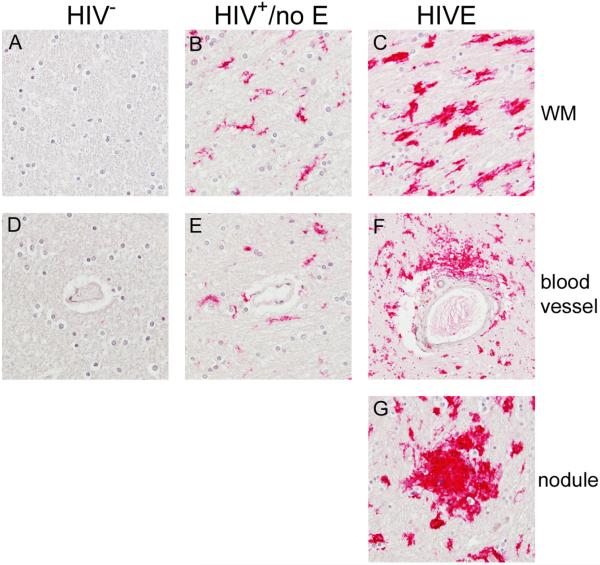

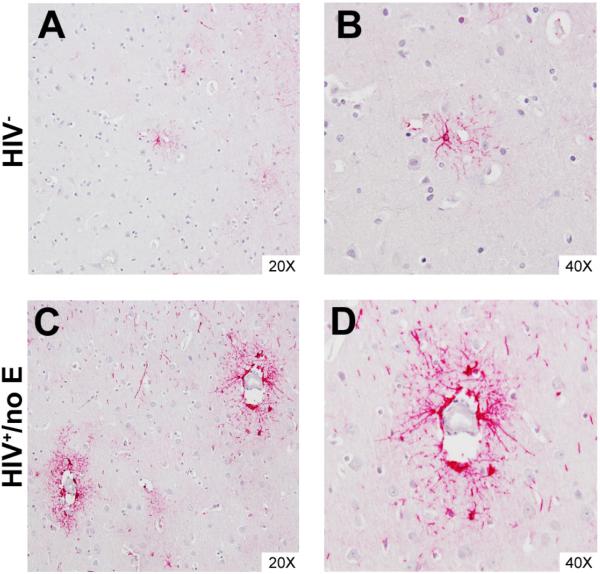

MΦ/microglial activation in HIV +/no E is phenotypically similar to that seen in HIVE

Previously we reported significant accumulation of CD16+ and CD163+ MΦs/microglia in the brains of patients with HIVE that was not observed in patients without encephalitis in the pre-cART era [6, 7]. Here, we performed immunohistochemical analyses to investigate CD16 and CD163 expression in FWM and BG. As reported previously, significant CD16 expression was observed on MΦs/microglia that accumulated within the brain parenchyma, as well as those that comprise perivascular cuffs and nodular lesions, in the brains of patients with HIVE (Figure 2, Panels C, F, and G) and was absent in seronegative brains (Figure 2, Panels A and D). In contrast to our earlier findings, CD16 expression was also seen in the CNS of patients with HIV+/no E (Figure 2, Panels B and E), although this was generally to a much lesser extent than that observed in HIVE (see Table 2). In addition, CD16+ MΦs/microglia in HIVE appear to be in a high activation state, as indicated by their rounded morphology and retracted branches with increased cytoplasm. Comparatively, microglia in HIV+/no E have a more ramified morphology (Figure 2, compare Panels B and C), but appear to have retracted processes that are thicker than is normally seen in healthy CNS. The results of these studies are summarized for each subject in Table 2.

Figure 2. CD16+ MΦs/microglia are observed in the CNS of HIV+ patients with and without encephalitis.

As reported previously, significant accumulation of CD16+ MΦs and microglia are observed in the CNS of patients with HIVE. These cells are found in the parenchyma (Panel C) and comprising perivascular cuffs (Panel F) and nodular lesions (Panel G). HIV+/no E also demonstrated considerable CD16 expression in the CNS (Panels B and E), but was less than that seen in HIVE (see Table 2). The degree of positivity varied in this patient population, where some patients demonstrated a low level, while others showed greater CD16 expression. Indeed, some patients in the HIV+/no E grouping demonstrated both high and low frequencies. This is in contrast to HIVE CNS, which showed a high frequency of CD16 expression throughout the brain section studied. CD16+ microglia in HIVE appear to be in a higher activation state, suggested by a rounded morphology with retracted branches and greater cytoplasm than normally seen in healthy CNS, than in HIV+/no E, which show a more ramified morphology (compare Panels B and C). CD16 was not observed in seronegative CNS (Panels A and D). All panels shown at 40X magnification under oil.

Table 2.

Macrophage/Microglia Immunoreactivity Score and Description

| PID | Class | CD16 | CD163 | HLA-DR | HIVp24 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 500 | HIVE | FWM: 2½+ BG: 3+; global, round and ramified, cuffs, nodules and MNGC | FWM & BG: 4+; global bright pv MΦs, round and ramified parenchymal cells, cuffs, nodules | FWM: 3+; pv MΦs/cuffs, MNGC, many parenchymal rounded MΦs/microglia BG: 4+; several large pv cuffs and nodules, MNGC, MΦs/microglia throughout parenchyma |

FWM: 3+; parenchymal, single area of pathology containing nodules and MNGC BG: 4+; parenchyma, several nodules, pv cuffs, MNGC |

| 537 | HIVE | FWM: 3; BG: 2½+; global, round and ramified, cuffs, nodules and MNGC; dimmer in BG | FWM & BG: 4+; global bright pv MΦs, round and ramified parenchymal cells, cuffs, nodules | FWM: 2+; several nodules and pv cuffs in same proximity BG: 2+; scattered nodules and cell aggregates, MNGC, microglia in areas of pathology |

FWM: 3+; two areas of intense positivity that is largely parenchymal BG: 1+; nodules |

| 540 | HIVE | FWM & BG: 4+; global, nodules, cuffs and microglia | FWM & BG: 4+; global bright pv MΦs, round and ramified parenchymal cells, cuffs, nodules | FWM: 2½+; many pv MΦs, single large area containing positive microglia and MNGC BG: 3+; pv MΦs/cuffs, nodules, MNGC, microglia in areas of pathology |

FWM: negative BG: negative |

| 603 | HIVE | FWM & BG: 4+; global, bright, particularly in areas associated with pathology | FWM & BG: 4+; large patchy areas in FWM, global in BG; bright pv MΦs, round and ramified parenchymal cells, cuffs, nodules | FWM: 2½+; pv MΦs, single large area with positive pv MΦs/cuffs, nodules, microglia BG: n/d |

FWM: ½+; no significant pathology, microglia with thick processes BG: 1+; no significant pathology, microglia with thick processes |

| 10017 | HIVE | FWM: 1½+; large areas with dim positivity BG: 2½+; large bright areas, many containing nodules |

FWM: 3 BG: 4+; global bright pv MΦs, round and ramified parenchymal cells, cuffs, nodules | FWM: 3½+; positive microglia throughout section, many nodules, pv MΦs/cuffs BG: 4+; positive microglia throughout, many nodules, MNGCs, pv MΦs/cuffs |

FWM: n/d BG: 4+; many ramified microglia with thickened processes, nodules, pv cuffs |

| 10070 | HIVE | FWM & BG: 4+; global, nodules, cuffs and microglia | FWM & BG: 4+; global bright pv MΦs, round and ramified parenchymal cells, cuffs, nodules | FWM: n/d BG: 3+; pv MΦs/cuffs with positive proximal microglia |

FWM: 4+; parenchymal, large area of pathology containing nodules and MNGC BG: 2½+; no pathology in section, microglia are rounded and scattered |

| 10133 | HIVE | FWM: 4+; global, nodules, cuffs and microglia BG: 2+; nodules, few areas with dim positivity |

FWM: 4+ BG: 3+; global in FWM, large patchy areas in BG; bright pv MΦs, round and ramified parenchymal cells, cuffs, nodules | FWM: 4+; positive microglia throughout, many nodules, pv MΦs/cuffs BG: 3½+; patchy, strongly positive regions throughout section containing microglia, nodules, pv MΦs/cuffs |

FWM: 2+; three areas containing ramified microglia with thick processes, MNGC, pv cuffs, nodules BG: 2½+; several regions containing ramified microglia with thick processes, MNGC, pv cuffs, nodules |

| 10231 | HIVE | FWM: 4+; global; most areas bright with rare dim BG: negative |

FWM & BG: 4+; global bright pv MΦs, round and ramified parenchymal cells, cuffs, nodules | FWM: 1+; rare pv MΦs with single area of several blood vessels with accumulation of positive cells BG: 2+; parenchymal cell aggregates (“soft” nodules) with microglia in proximity, several pv MΦs |

n/d |

| 10001 | HIV+/no E | FWM: 3+; diffuse positivity with bright and dim areas BG: ½+; single small dim area |

FWM: 3+; bright pv MΦs, large patches of parenchymal positivity; some cells appear to have aggregated BG: 2½+: bright pv MΦs; parenchymal positivity is predominantly in GM |

FWM: 1+; single small area with pv MΦs and microglia BG: 1+; single area contains scattered microglia, rare microglia in other areas with minimal pv MΦs |

FWM: negative BG: negative |

| 10011 | HIV+/no E | FWM: 4+; global, microglia BG: 3+; global, dimmer than FWM, few areas where cells appear to have aggregated (“soft” nodules) |

FWM: 4+; bright pv MΦs; several parenchymal areas BG: 3+; bright pv MΦs with patches of parenchymal positivity |

FWM: n/d BG: ½+; positivity only with one aggregate of cells in the parenchyma (“soft” nodule) |

FWM: negative BG: negative |

| 10013 | HIV+/no E | FWM: 3+; diffuse with bright and dim areas BG: 1½+; several dim areas, single bright area |

FWM: ½ +; bright pv MΦs, BG: 2½+; bright pv MΦs, patchy in parenchyma | FWM: negative BG: ½+; limited to pv MΦs |

FWM: negative BG: negative |

| 10016 | HIV+/no E | FWM: 1½+; single area with dim positivity BG: negative |

FWM: 2½+; single area with bright positivity BG: 1+; bright pv MΦs |

FWM: negative BG: negative |

FWM: negative BG: negative |

| 10066 | HIV+/no E | FWM: 3+; global, ramified BG: negative |

FWM: 3+; bright pv MΦs, parenchymal positivity BG: 1+; bright pv MΦs, rare parenchymal positivity |

FWM: negative BG: ½+; rare pv MΦs, single area with rare parenchymal microglia |

FWM: negative BG: negative |

| 10067 | HIV+/no E | FWM: ½+; most seen around or proximal to blood vessels BG: negative |

FWM: 1½+; bright pv MΦs, small parenchymal region BG: 1+; bright pv MΦs |

FWM: 1½+; two strongly positive nodules, scattered microglia, some pv MΦs BG: 2+; scattered microglia with aggregates of cells (“soft” nodules) |

FWM: negative BG: negative |

| 10119 | HIV+/no E | FWM: 4+; global, bright; some pv MΦ accumulation, a possible “soft nodule” BG: ½+; single region with dim pv MΦ and parenchymal expression |

FWM: 4+; global positivity; brighter pv than parenchymal in some areas; possible cuffs BG: 1½+; bright pv MΦs with mild parenchymal positivity |

FWM & BG: ½+; rare pv MΦs and proximal microglia | FWM: negative BG: negative |

| 10127 | HIV+/no E | FWM: negative BG: negative |

FWM: 1+; bright pv MΦs BG: ½+; pv MΦs slightly brighter than normal |

FWM: 1+; moderate pv MΦ positivity, rare presence of small pv cuffs BG: 2+; moderate pv MΦ throughout, some pv cuffs present, single parenchymal region containing cells with a round or rounded morphology |

FWM: n/d BG: n/d |

| 10203 | HIV+/no E | FWM: 3½+; large bright regions, one dim BG: 1: single dim area |

FWM: 4+; bright pv MΦs and parenchymal microglia BG: 2½+; bright pv MΦs, patchy parenchymal positivity |

FWM: n/d BG: 2+; pv MΦs with microglia in surrounding area |

FWM: negative BG: negative |

| 30024 | HIV+/no E | FWM: 1+; single dim region BG: negative |

FWM: 2+; bright pv MΦs with scattered dim positivity in parenchyma BG: 1+; bright pv MΦs |

FWM: negative BG: ½+; single blood vessel shows positive pv MΦs |

FWM: negative BG: negative |

| 551 | HIV− | FWM: ½+; rare parenchymal cells BG: negative |

FWM: 0 BG: 0 |

FWM: negative BG: negative |

n/a |

| 567 | HIV− | FWM & BG: negative | FWM: 0 BG: ½+; pv MΦs slightly brighter than normal |

FWM: 1+; rare parenchymal positivity, round infiltrating cells and cell accumulation associated with a single blood vessel BG: ½+; rare pv MΦs with few parenchymal microglia |

n/a |

| 588 | HIV− | FWM: 1+; most positivity seen perivascularly with rare dim parenchymal positivity BG: negative |

FWM: 1+; bright pv MΦs, rare parenchymal positivity BG: ½+; pv MΦs slightly brighter than normal |

FWM: negative BG: ½+; rare pv MΦs |

n/a |

| 594 | HIV− | FWM & BG: negative | FWM: 1+; bright pv MΦs, rare parenchymal positivity BG: ½+; pv MΦs slightly brighter than normal |

FWM: negative BG: 1+; limited to pv MΦs |

n/a |

| 601 | HIV− | FWM & BG: negative | FWM: ½+; pv MΦs slightly brighter than normal BG: 0 |

FWM: negative BG: ½+; rare pv MΦs |

n/a |

Autopsy FWM and BG from HIVE, HIV+/no E and seronegative subjects were investigated for MΦ/microglial expression of CD16, CD163, HLA-DR and HIVp24, for productive HIV-1 infection, by immunohistochemistry. Immunostained CNS tissues were scored independently by two observers. A score of 0-4 was assigned to each section after the observation of a minimum of 10 microscopic fields at 40× objective magnification and was based on a qualitative average of the number of immunostained cellular profiles. The results of these studies are summarized for each subject above. Normal distribution and intensity of CD163, which is found on perivascular MΦs in healthy CNS, is indicated by a score of “0”. This is in contrast to “negative”, which indicates the absence of the indicated marker. Abbreviations: n/d = not done; n/a = not applicable; MNGC = multi-nucleated giant cells; pv = perivascular.

While CD16 expression was observed in both HIVE and HIV+/no E subjects, the degree of positivity varied in HIV+/no E, where some patients demonstrated low and others showed higher CD16 expression. This may have been related to plasma viral loads, as of the four HIV+/no E subjects with low viral loads (<5000 copies/ml), three were given scores under 2+ in both the FWM and BG. This is in contrast to HIVE, which showed a high frequency of CD16 expression in all brains studied, and in whom all pre-mortem viral loads were over 150,000 copies/ml. To investigate the relationship of CD16 expression between HIV+/no E and HIVE, the number of CD16+ cells in the FWM and BG was determined for each case as described above for CD68. A comparison of the two means by Student's t-test demonstrated a trend toward a higher frequency of CD16+ microglia in HIVE that did not reach statistical significance (Figure 1).

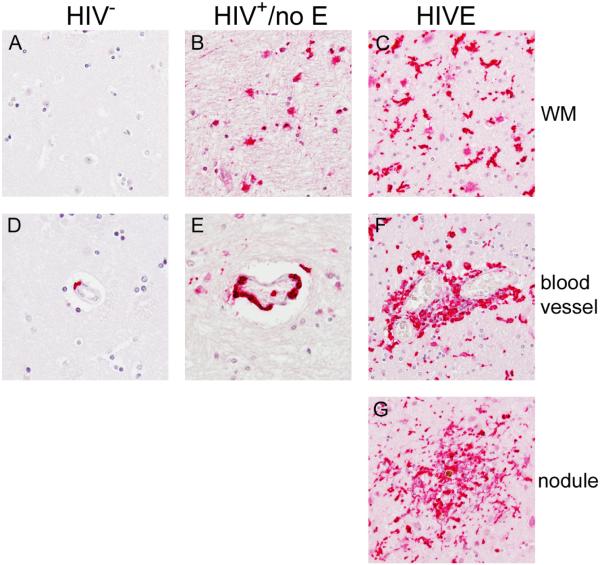

Like CD16, significant accumulation of CD163+ MΦs and microglia were observed in the CNS of patients with HIVE within the parenchyma, perivascular cuffs, and nodular lesions (Figure 3, Panels C, F, and G). In normal brain, CD163+ expression was seen on perivascular MΦs, but not parenchymal microglia (Figure 3, Panel A and D), consistent with normal CD163 expression in the CNS [12, 13]. As compared to seronegatives, brain tissue from HIV+/no E subjects showed some accumulation of CD163+ perivascular MΦs (Figure 3, Panel E) but not to the same degree as HIVE (Figure 3, Panel F). Likewise, while CD163 positivity was observed in the brain parenchyma of patients with HIV+/no E (Figure 3, Panel B), it appeared to be much less than that observed in HIVE (Figure 3, Panel C) and mostly in patches within the section studied, rather than the global positivity observed in HIVE (Table 2). Interestingly, CD163+ microglia in HIV+/no E mostly appeared as rounded cells with few branches. Rounded CD163+ cells are also observed in HIVE, in addition to numerous activated microglia with thickened, retracted processes (Figure 3, compare Panels B and C). The results of these studies are summarized for each subject in Table 2.

Figure 3. CD163+ MΦs/microglia accumulate in the CNS of HIV+ patients with and without encephalitis.

As reported previously, significant accumulation of CD163+ MΦs and microglia are observed in the CNS of patients with HIVE within the parenchyma (Panel C), perivascular cuffs (Panel F) and nodular lesions (Panel G). To a lesser degree, CD163 positivity was also observed in the brain parenchyma of patients with HIV+/no E (Panel B). CD163+ microglia in HIV+/no E appear rounded with few branches. Rounded CD163+ cells are also observed in HIVE, in addition to numerous activated microglia with thickened, retracted processes (compare Panels B and C). In normal brain, CD163+ expression is seen on perivascular MΦs (Panel D), but is not normally expressed by resident microglia (Panel A). Comparatively, accumulation of CD163+ perivascular MΦs is seen in HIV+/no E (Panel E) but not to the same degree of that observed in HIVE (Panel F). All panels shown at 40X magnification under oil.

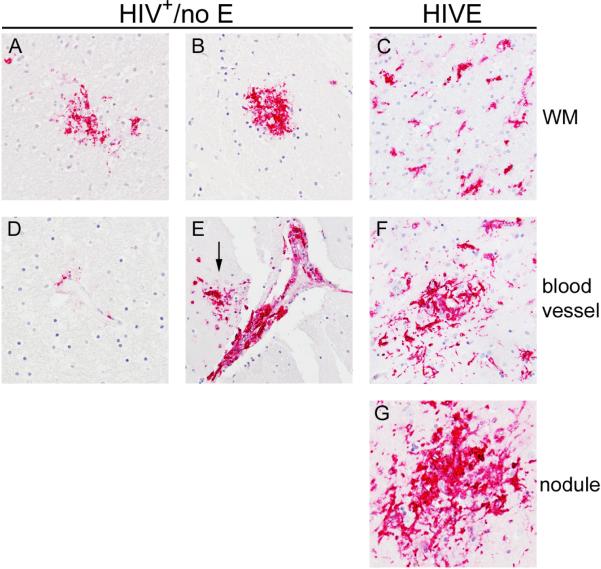

HLA-DR expression in HIV+/no E reveals pathology consistent with HIVE

HLA-DR expression in HIVE was predominantly by MΦs/microglia that accumulated perivascularly and within nodular lesions (Figure 4, Panels F and G), consistent with our earlier findings [6]. To a lesser degree, HLA-DR was expressed by activated microglia, with thickened and retracted processes, in the parenchyma and was most often observed in areas of pathology (Figure 4, Panel C). In contrast to HIVE, HLA-DR expression in the brains of subjects with HIV+/no E was, for the most part, not observed on cells in the parenchyma, however, when present, parenchymal HLA-DR was observed, it was seen on aggregates of cells, or what we've termed, “soft nodules”, because they appear as mild cell aggregates, rather than the distinct large nodular lesions seen in HIVE (Figure 4, Panels A and B). Rarely, HLA-DR expression was seen on perivascular MΦs in HIV+/no E (Figure 4, Panel D), with the exception of five subjects, who demonstrated a greater degree of HLA-DR+ MΦ accumulation perivascularly that appeared to develop into cuffs in some subjects (Figure 4, Panel E). In seronegative brain, HLA-DR was predominantly limited to rare expression by perivascular MΦ (Table 2).

Figure 4. HLA-DR reveals pathological alterations in HIV+/no E.

HLA-DR expression in HIVE was seen by MΦs/microglia that accumulated perivascularly (Panel F) and within nodular lesions (Panel G). In the parenchyma, HLA-DR was expressed by activated microglia, with thickened and retracted processes, most often observed in areas of pathology (Panel C). In the CNS of subjects with HIV+/no E, HLA-DR was, for the most part, not expressed by cells in the parenchyma (not shown). Interestingly, when parenchymal HLA-DR was observed, it was seen on aggregates of cells, or “soft nodules” (Panels A and B). Rare HLA-DR expression was seen on perivascular MΦs in HIV+/no E (Panel D), with the exception of five subjects, who demonstrated some degree of HLA-DR+ MΦ accumulation perivascularly, that appeared to develop into cuffs in one subject (Panel E). A nodule also appears to have formed in the region of the cuff shown in Panel E (arrow). All panels shown at 40X magnification under oil.

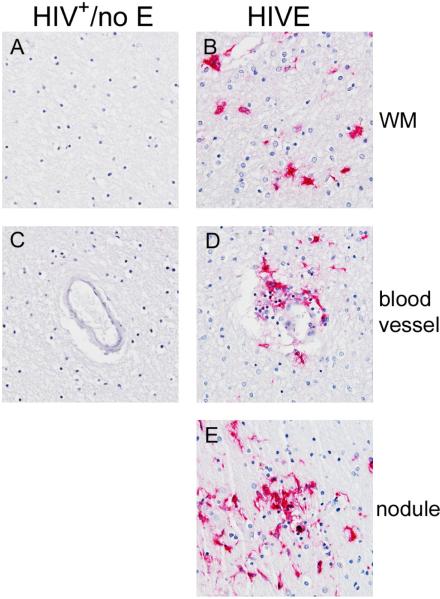

Detectable productive HIV infection remains limited to HIVE

In HIVE, productive HIV infection was detected, as indicated by HIVp24 positivity (Figure 5, Panels B, D and E) and in situ hybridization (data not shown). Similar studies did not reveal productive infection in any of the HIV+/no E cases (Figure 5, Panels A and C), including those with cell aggregates suggestive of nodular lesion formation.

Figure 5. Productive HIV infection is not detected in the CNS of patients with HIV+/no E.

In HIVE CNS, productive HIV infection was detected, as indicated by HIVp24 positivity (Panels B, D and E). This was not observed in any of the HIV+/no E cases studied (Panels A and C). All panels shown at 40X magnification under oil.

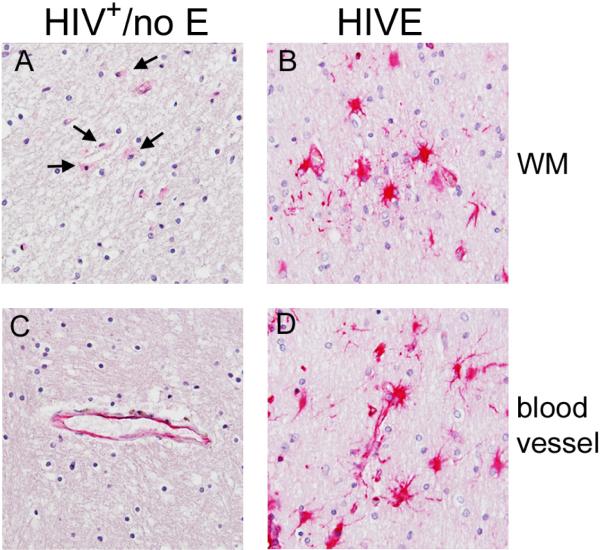

Distinct patterns of GFAP and vimentin expression and astrocyte morphology are seen in HIV infected patients with and without encephalitis

Astrocyte expression of GFAP was observed in all groupings, but with apparent differences in the frequency of GFAP+ cells, intensity of GFAP expression and astrocyte morphology. Increased frequency of GFAP+ astrocytes was observed in WM of subjects with HIV+/no E and HIVE, as compared to those without HIV, which corresponded with greater astrocyte hypertrophy (Figure 6, compare Panels A, B and C; compare Panels D, E and F). In cortical grey matter (GM), GFAP expression by astrocytes in areas away from blood vessels was only observed in HIVE (Figure 6, compare Panels G and H with Panel I). Of particular interest is the finding that in both HIVE and HIV+/no E, perivascular astrocytes often expressed higher levels of GFAP than those in the brain parenchyma, suggesting that events at the blood-brain barrier (BBB) influence astrocyte activation. This is most evident in the cortical GM of patients with HIV+/no E, which often displayed perivascular astrocyte positivity that did not extend significantly into the parenchyma (Figure 7, Panels C and D). To a considerably lesser degree in frequency and intensity, this phenomenon was also observed in seronegative brain (Figure 7, Panels A and B).

Figure 6. GFAP expression and astrocyte morphology in HIV infected patients with and without encephalitis.

GFAP expression by astrocytes was observed in all groupings, but with apparent differences in the frequency of GFAP+ cells, expression intensity and astrocyte morphology. Increasing frequency of GFAP+ astrocytes was observed in the white matter (WM) of HIV+/no E and HIVE subjects, as compared to HIV− subjects (compare Panel A with Panels B and C; compare Panel D with Panels E and F). The increased frequency of GFAP+ astrocytes corresponds to decreased GFAP expression and greater astrocyte hypertrophy, with the most severe seen in HIVE (Panels C and F). In grey matter (GM), GFAP expression by astrocytes in areas away from blood vessels was only observed in HIVE (compare Panels G and H with Panel I). These astrocytes demonstrate higher (brighter) expression of GFAP, than those found in WM, and have largely retained their star-life morphology (compare Panel I with Panel C).

Figure 7. GFAP positivity distinguishes perivascular astrocytes in cortical GM of patients with HIV+/no E.

Perivascular astrocytes were often found to express higher levels of GFAP than those in the brain parenchyma in HIVE and HIV+/no E, suggesting events at the BBB influence astrocyte activation. This is most obvious in cortical GM of patients with HIV+/no E, which often displayed regions of perivascular astrocyte positivity that did not extend significantly into the parenchyma (Panels C and D). This was also observed, but to a considerably lesser degree in frequency and intensity, in seronegative CNS (Panels A and B).

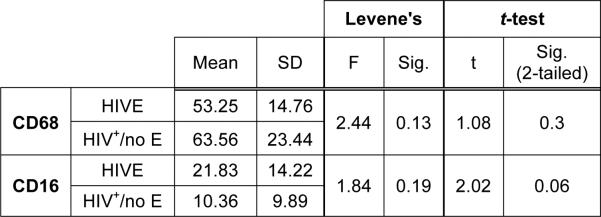

In contrast to GFAP positivity, expression of vimentin was only observed on astrocytes in HIV+/no E and HIVE. This was seen at a much greater frequency and intensity in HIVE (Figure 8, Panels B and D) than HIV+/no E (Figure 8, Panels A and C), but appeared to be limited to hypertrophic astrocytes in both groupings. Unlike GFAP, vimentin did not highlight astrocytes located around blood vessels in HIV+/no E. HIV+/no E shows what appears to be endothelial staining, which is also observed in HIVE but with the additional astroglial positivity (Figure 8, compare Panels C and D). In seronegative CNS, rare hypertrophic vimentin+ astrocytes were observed in only one case. The results of these studies are summarized for each subject in Table 3.

Figure 8. Vimentin positivity is primarily limited to hypertrophic astrocytes in HIVE and HIV+/no E.

Vimentin positivity was more frequent and intense in HIVE (Panels B and D) than HIV+/no E (Panels A and C), but limited to hypertrophic astrocytes in both groupings. Unlike GFAP, vimentin did not highlight astrocytes located around blood vessels in HIV+/no E (see Figure 7). HIV+/no E shows what appears to be endothelial staining, which is also observed in HIVE but with the additional astroglial positivity (Panels C and D). Rare hypertrophic vimentin+ astrocytes were observed in only one of the seronegative cases studied (see Table 3).

Table 3.

Astrocyte Immunoreactivity Score and Description

| PID | Class | GFAP | Vimentin |

|---|---|---|---|

| 500 | HIVE | 4+; dim and bright throughout section, dim is associated with astrocyte hypertrophy in WM, higher expression by perivascular astrocytes in WM and GM, bright ramified throughout GM | 4+; primarily hypertrophic astrocytes throughout WM, rare dim hypertrophic in GM |

| 537 | HIVE | 3½+; primarily dim associated with astrocyte hypertrophy in WM, patches of high-expressing ramified GM astrocytes and hypertrophic perivascular astrocytes in WM and GM | 3+; primarily patches of hypertrophic astrocytes in WM, higher expression seen at the WM/GM boundary, rare dim hypertrophic in GM |

| 540 | HIVE | 3½+; primarily dim associated with astrocyte hypertrophy in WM, patches of high-expressing ramified GM astrocytes and hypertrophic perivascular astrocytes in WM and GM | 1½+; occasional bright hypertrophic astrocytes in WM, rare dim hypertrophic in GM |

| 603 | HIVE | 4+; significant throughout section, hypertrophic astrocytes in WM tend to be dimmer than ramified astrocytes in GM, bright expression by perivascular astrocytes in WM and GM | 3+; primarily patches of hypertrophic astrocytes in WM with rare positive cells scattered throughout, higher expression seen at the WM/GM boundary, negative in GM |

| 10017 | HIVE | 3+; primarily dim associated with astrocyte hypertrophy in WM, few high-expressing ramified astrocytes in GM | 1+; primarily hypertrophic astrocytes in WM, rare very dim hypertrophic in GM |

| 10070 | HIVE | n/d | n/d |

| 10133 | HIVE | 2½+; primarily low-expressing hypertrophic astrocytes in WM with higher expression and ramified morphology near and within GM; patchy perivascular positivity in GM | 2½+; bright and dim hypertrophic astrocytes throughout WM, dim hypertrophic at WM/GM boundary, negative in GM |

| 10231 | HIVE | 3½+; positivity throughout section, mostly bright and ramified in WM and GM with several areas of dim positivity associated with astrocyte hypertrophy in WM, high-expressing perivascular astrocytes in WM and GM | negative |

| 10001 | HIV+/no E | 3½+; high-expressing ramified astrocytes throughout section with bright perivascular in WM and GM, infrequent areas in WM with bright hypertrophic astrocytes | 1½+; single small region with primarily bright hypertrophic and rare ramified astrocytes in WM, negative in GM |

| 10011 | HIV+/no E | 3+; high-expressing ramified astrocytes throughout section, bright perivascular positivity in WM and GM, some regions show only perivascular positivity, significant positivity at the WM/GM boundary, several areas in WM with bright hypertrophic astrocytes | 1½+; primarily dim with a small region of bright hypertrophic astrocytes in WM, negative in GM |

| 10013 | HIV+/no E | 3½+; bright hypertrophic astrocytes throughout section, ramified astrocytes also present | ½+; rare, very dim hypertrophic astrocytes in WM, negative in GM |

| 10016 | HIV+/no E | 3+; bright ramified astrocytes in WM, infrequent bright perivascular astrocytes in GM | ½+; rare, very dim hypertrophic astrocytes in WM, negative in GM |

| 10066 | HIV+/no E | 3½+; high-expressing ramified astrocytes throughout section, frequent large areas with bright hypertrophic astrocytes, significant positivity in GM with high perivascular expression | ½+; rare, very dim hypertrophic astrocytes in WM, negative in GM |

| 10067 | HIV+/no E | 2½+; bright ramified astrocytes at WM/GM boundary and in regions of GM, dimmer hypertrophic astrocytes in WM | ½+; rare, very dim hypertrophic astrocytes in WM, negative in GM |

| 10119 | HIV+/no E | 3½+; bright ramified astrocytes in GM with primarily dimmer hypertrophic astrocytes in WM | 2+; single large area with bright hypertrophic astrocytes in WM, negative in GM |

| 10127 | HIV+/no E | 2½+; bright ramified astrocytes in WM and at WM/GM boundary, infrequent areas of dim hypertrophic astrocytes in WM, positivity in GM is limited to perivascular astrocytes | negative |

| 10203 | HIV+/no E | n/d | n/d |

| 30024 | HIV+/no E | 3½+; bright ramified astrocytes in WM and at WM/GM boundary, dim hypertrophic astrocytes also present in WM, positivity in GM is limited to perivascular astrocytes | negative |

| 551 | HIV− | 2½+; positivity in GM is limited to perivascular astrocytes, some large areas of bright ramified with rare dim hypertrophic astrocytes in WM | negative |

| 567 | HIV− | 3+; regions of primarily bright ramified with rare dim hypertrophic astrocytes in WM, GM positivity is limited to perivascular astrocytes | negative |

| 588 | HIV− | 2½+; regions of primarily bright ramified with rare dim hypertrophic astrocytes in WM, no GM present in section | negative |

| 594 | HIV− | 2+; regions of primarily dim hypertrophic astrocytes in WM with bright ramified perivascular astrocytes and at WM/GM boundary, GM positivity is limited to perivascular astrocytes | negative |

| 601 | HIV− | 1½+; rare dim hypertrophic astrocytes in WM with bright ramified astrocytes at the WM/GM boundary | ½+; rare hypertrophic astrocytes in WM |

Autopsy FWM from HIVE, HIV+/no E and seronegative subjects were investigated for astrocyte expression of GFAP and vimentin by immunohistochemistry. The results of these studies are summarized for each subject above. Abbreviations: n/d = not done; pv = perivascular.

Discussion

In this histological study, we show similar features of immune activation in the CNS of neurocognitively impaired HIV infected persons with and without encephalitis, regardless of cART at the time of death. Many of the findings in HIV+/no E brain are more pronounced in HIVE, with greater expression intensity and/or frequency (Table 4), suggesting that similar pathogenic mechanisms are involved in the lesser and more severe forms of HAND. A caveat is that for many of these individuals, cART was for some reason not efficacious, as evidenced by high plasma viral loads, or not present at the time point that plasma viral load determinations were obtained. Additionally, despite cART access, all but one of our patients had significantly depressed (AIDS-defining) CD4 counts. In this study, however, we examined the presence of HIV in brain, and as anticipated, showed it was limited to individuals with HIVE, even though the immunological profile of HIVE and HIV+/no E were similar (Table 4). Thus, our results are applicable to individuals on and off cART, with and without viral suppression systemically or in the brain.

Table 4.

Summary of Immunohistological Findings

| Class | HIVp24 | CD16 | CD163 | HLA-DR | GFAP | Vimentin |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HIVE | FWM: 2+ BG: 2+ Nodules, cuffs and microglia with thickened processes |

FWM: 3½+ BG: 2¾+ Global and patchy positivity of microglia, nodules, cuffs and MNGC |

FWM and BG: 4+ Global positivity of microglia, nodules, cuffs and MNGC | FWM: 2½+ BG: 3+ Mostly nodules and pv MΦs/cuffs with patchy regions of positive microglia |

FWM: 3½+ Primarily dim hypertrophic astrocytes in WM with infrequent high-expressing ramified astrocytes in cortical GM |

FWM: 2+ Primarily hypertrophic astrocytes in WM with rare dim hypertrophic astrocytes in cortical GM |

| HIVnoE | Negative | FWM: 2½+ BG: ¾+ Predominantly patchy microglial positivity with bright and dim cells; some cell aggregates (“soft nodules”) noted |

FWM: 2½+ BG: 1½+ Bright pv MΦs with patches of parenchymal positivity |

FWM: ½+ BG: 1+ Mostly patchy and limited to pv MΦs and regional microglia; some cell aggregates (“soft nodules”) noted |

FWM: 3+ Mostly bright ramified astrocytes in WM and at WM/GM boundary, infrequent dim hypertrophic astrocytes in WM, positivity in GM is largely limited to pv astrocytes |

FWM: ¾+ Rare, very dim hypertrophic astrocytes in WM, negative in cortical GM |

| HIV− | n/a | FWM: <½+ BG: negative Rare, limited pv and parenchymal positivity observed in 2 of 5 cases |

FWM and BG: <½+ Limited pv MΦs slightly brighter than normal and rare parenchymal positivity |

FWM and BG: <½+ Limited, rare pv MΦs |

FWM: 2+ Primarily patchy, bright ramified astrocytes; when present, cortical GM positivity is limited to pv astrocytes |

Negative |

The average positivity score and most frequent findings from the immunohistochemical studies is tabulated for each class. Abbreviations: n/a = not applicable; pv = perivascular.

Previously, we demonstrated significant accumulation of CD16+ and CD163+ MΦs and microglia in FWM and BG of HIV-infected human subjects from the pre-cART era and SIV-infected rhesus macaques with encephalitis, which was not observed in HIV/SIV infection without encephalitis [6, 8]. These cells were found in the brain parenchyma and comprised nodular lesions and perivascular cuffs. Importantly, CD16+/CD163+ perivascular MΦs appeared to be the major reservoir of productive HIV infection, suggesting that late invasion of HIV-infected monocytes/MΦs occurs in some individuals and in the context of increased viremia and immune dysfunction (AIDS) [6, 8]. Here, we show CD16 expression by microglia at a lower frequency in HIV+/no E than in HIVE, with only rare perivascular MΦ positivity, which may be related to systemic viremia. Further, CD16+ microglia in HIVE appear to be in a higher activated state, with increased cytoplasm and thickened, retracted processes. CD16 expression reveals different degrees of microglial activation in HIV infection that likely contributes to neurocognitive decline, even among those who do not go on to develop frank dementia and encephalitis.

CD163, which is normally expressed by perivascular MΦs but not resident microglia [13], was observed on parenchymal microglia in HIV+/no E. Expression is significantly less in HIV+/no E than that seen HIVE and also appears in patches, rather than the global immunopositivity seen in HIVE, suggesting the presence of foci of immune activation in the CNS during earlier stages of disease that may contribute to neurocognitive impairment. CD163 is also up-regulated by perivascular MΦs and reveals some mild perivascular cell accumulation in HIV+/no E, suggesting early immune activity at the blood-brain barrier (BBB) before the formation of cuffs.

Astrocytes provide additional evidence of activity occurring at the level of the BBB in both mild and severe CNS disease, with GFAP expression by perivascular astrocytes, which have endfeet that terminate on the brain capillaries, that is often greater (brighter) than expression by parenchymal astrocytes. This is evident in WM in both HIV+/no E and HIVE, but is most apparent in cortical GM of patients with HIV+/no E. Here, expression is primarily limited to perivascular astrocytes and does not extend significantly into the parenchyma, suggesting events at the BBB may precede and promote glial activation in the parenchyma. While the cause of astrocyte activity and GFAP expression at the BBB is unknown, several cytokines and other soluble MΦ activation factors implicated in HIVE pathogenesis, including tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), interleukin (IL)-1β, and nitric oxide (NO), reportedly upregulate GFAP expression [14-16]. Indeed, perivascular MΦ CD163 and HLA-DR expression may represent similar or distinct MΦ activation states throughout the disease process that could influence perivascular astrocyte activation, as well as promote and maintain inflammation/activation in the parenchyma. This may explain, at least in part, the significant presence of reactive parenchymal astrocytes in the cortical GM in HIVE that is not observed in HIV+/no E. Interestingly, astrocytic expression of vimentin, an intermediate filament protein that may be involved in hypertrophy of astrocytic processes [17], is significantly greater in HIVE, which also shows more pronounced astrocyte hypertrophy than that seen in HIV+/no E, and may be the result of lengthy and extensive neuroinflammation.

The pattern of MHC class II expression, as determined by HLA-DR immunoreactivity, in HIV+/no E and HIVE also suggests different stages of the same disease process. In HIVE, significant HLA-DR expression is seen on MΦs/microglia that accumulate around blood vessels and within nodular lesions, as well as activated microglia with short, thickened processes. This is significantly attenuated in HIV+/no E and largely limited to perivascular MΦs with proximal microglial positivity, suggesting activity at the BBB, precedes parenchymal involvement. Of great interest, however, is the ‘unveiling’ by HLA-DR immunopositivity of what appear to be nodular lesions in two cases of HIV+/no E and perivascular cuffs in a third. While we had noted potential “soft” nodules in some HIV+/no E cases positive for CD16 and/or CD163, surrounding immunopositivity obfuscated these important pathological features. HLA-DR, which may suggest a different type of MΦ/microglial activation, clearly reveals what is likely early nodule formation in HIV+/no E and provides evidence that the different forms of HAND are a continuum of the same disease process.

Although considerable inflammation is seen in HIV+/no E CNS, productive HIV infection was not detected, through either immunohistochemistry against HIVp24 or in situ hybridization studies directed against HIV RNA, even with the use of tyramide signal-amplification methods (data not shown). The neuroinflammation observed in the absence of productive infection may result from a number of different factors, including low level virus production that is below our level of detection, neurotoxic affects of cART, itself, and/or chronic systemic immune activation that may be present, with or without CD4+ T cell reconstitution and virus suppression. Indeed, persistent systemic monocyte/MΦ activation, associated with microbial translocation, has been reported in HIV infected persons under successful pharmacological intervention [18]. In addition, factors associated with Alzheimer's dementia (AD) and other chronic neurodegenerative diseases, including amyloid-β, hyperphosphorylated tau and α-synuclein, have been reported to accumulate in the CNS of HIV infected patients without encephalitis or productive CNS infection and are believed to contribute to neuroinflammation [19-21]. Whether these factors induce inflammation in the CNS or accumulate in response to inflammatory events, however, remains unclear. Due to the limited number of brain specimens available for our studies, we have not yet explored the potential relationship between these factors and neuroinflammation.

Since the introduction of cART, the pattern of HAND has changed, with decreased incidence of HIV-D; however, less severe forms of HAND, ANI and MND, are now seen with greater frequency than that reported in the pre-cART era. Indeed, the increased incidence in the milder forms of HAND prompted the revised American Academy of Neurology (AAN) research criteria of HAND that increased the previous two degrees of HIV-associated neurocognitive impairment, HIV-D and MCMD, which was used to diagnose the subjects in this study, to include the three levels used today. Whether the three forms of HAND represent distinct diseases of the CNS or a continuum of the same disease process remains unclear. The longitudinal outcome of individuals diagnosed with mild forms of HAND is not always known and HAND does not appear to follow a predictable pattern or linear disease progression common to other neurodegenerative diseases, such as Parkinson's disease and Alzheimer's dementia. Further, a beneficial effect of cART on cognition has been associated with duration on therapy [1, 22], demonstrating a reversible component of neuronal injury with cART. Interestingly, this has been reported even among individuals on drug regimens with low BBB penetrance, suggesting that restored systemic immunity confers a protective benefit to the CNS. Indeed, a recent report demonstrated that low nadir CD4 and not virus suppression in the CSF was the best predictor for neurocognitive impairment, supporting a role for systemic immune impairment in HIV-related CNS injury [23].

Here, we show the presence of chronic CNS inflammation involving CNS-associated MΦs, microglia and astrocytes in HIV infection that would, presumably, impact homeostatic mechanisms in the brain and neuronal function. As such, neuroinflammation, which has a well-established and prominent role in HIV-D pathogenesis, likely contributes to the milder degrees of HAND, ANI and MND, suggesting a disease continuum, rather than three separate HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders and underscores the need for early diagnosis and intervention, as well as development of therapeutic strategies that target prolonged inflammation of the CNS. As with other AIDS-defining illnesses, cART may have slowed the progression of HIV-associated CNS disease, thus providing a larger window for understanding the pathogenesis. Identifying the mechanism(s) driving chronic inflammation of the CNS will likely provide important insights into the pathogenesis of neurodegenerative disease and may reveal potential targets for therapeutic intervention in HIV and, potentially, non-HIV related CNS disease.

Acknowledgments

Grant: RO1 NS063605 (TFS)

Abbreviations

- HAND

HIV-associated neurocognitive impairment

- HIV-D

HIV-associated dementia

- MND

mild neurocognitive disorder

- MCMD

minor cognitive motor disorder

- ANI

asymptomatic neurocognitive impairment

- cART

combination anti-retroviral therapy

- MΦ

macrophage

- CNS

central nervous system

- FWM

frontal white matter

- BG

basal ganglia

- MNGC

multi-nucleated giant cells

- pv

perivascular

References

- 1.Simioni S, Cavassini M, Annoni JM, et al. Cognitive dysfunction in HIV patients despite long-standing suppression of viremia. AIDS. 2010;24(9):1243–50. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3283354a7b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Borjabad A, Morgello S, Chao W, et al. Significant effects of antiretroviral therapy on global gene expression in brain tissues of patients with HIV-1-associated neurocognitive disorders. PLoS Pathog. 2011;7(9):e1002213. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Anthony IC, Ramage SN, Carnie FW, et al. Influence of HAART on HIV-related CNS disease and neuroinflammation. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2005;64(6):529–36. doi: 10.1093/jnen/64.6.529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fischer-Smith T, Rappaport J. Evolving paradigms in the pathogenesis of HIV-1-associated dementia. Expert Rev Mol Med. 2005;7(27):1–26. doi: 10.1017/S1462399405010239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ciardi A, Sinclair E, Scaravilli F, et al. The involvement of the cerebral cortex in human immunodeficiency virus encephalopathy: a morphological and immunohistochemical study. Acta Neuropathol. 1990;81(1):51–9. doi: 10.1007/BF00662637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fischer-Smith T, Croul S, Sverstiuk AE, et al. CNS invasion by CD14+/CD16+ peripheral blood-derived monocytes in HIV dementia: perivascular accumulation and reservoir of HIV infection. J Neurovirol. 2001;7(6):528–41. doi: 10.1080/135502801753248114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fischer-Smith T, Croul S, Adeniyi A, et al. Macrophage/microglial accumulation and proliferating cell nuclear antigen expression in the central nervous system in human immunodeficiency virus encephalopathy. Am J Pathol. 2004;164(6):2089–99. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63767-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fischer-Smith T, Bell C, Croul S, et al. Monocyte/macrophage trafficking in acquired immunodeficiency syndrome encephalitis: lessons from human and nonhuman primate studies. J Neurovirol. 2008;14(4):318–26. doi: 10.1080/13550280802132857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nomenclature and research case definitions for neurologic manifestations of human immunodeficiency virus-type 1 (HIV-1) infection. Report of a Working Group of the American Academy of Neurology AIDS Task Force. Neurology. 1991;41(6):778–85. doi: 10.1212/wnl.41.6.778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Clinical confirmation of the American Academy of Neurology algorithm for HIV-1-associated cognitive/motor disorder. The Dana Consortium on Therapy for HIV Dementia and Related Cognitive Disorders. Neurology. 1996;47(5):1247–53. doi: 10.1212/wnl.47.5.1247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Woods SP, Rippeth JD, Frol AB, et al. Interrater reliability of clinical ratings and neurocognitive diagnoses in HIV. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol. 2004;26(6):759–78. doi: 10.1080/13803390490509565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fabriek BO, Van Haastert ES, Galea I, et al. CD163-positive perivascular macrophages in the human CNS express molecules for antigen recognition and presentation. Glia. 2005 doi: 10.1002/glia.20208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rezaie P, Male D. Microglia in Fetal and Adult Human Brain Can Be Distinguished from Other Mononuclear Phagocytes through Their Lack of CD163 Expression. Neuroembryology. 2003;2(3):130–133. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brahmachari S, Fung YK, Pahan K. Induction of glial fibrillary acidic protein expression in astrocytes by nitric oxide. J Neurosci. 2006;26(18):4930–9. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5480-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sticozzi C, Belmonte G, Meini A, et al. IL-1beta induces GFAP expression in vitro and in vivo and protects neurons from traumatic injury-associated apoptosis in rat brain striatum via NFkappaB/Ca calmodulin/ERK mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling pathway. Neuroscience. 2013 doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2013.07.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhang L, Zhao W, Li B, et al. TNF-alpha induced over-expression of GFAP is associated with MAPKs. Neuroreport. 2000;11(2):409–12. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200002070-00037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wilhelmsson U, Li L, Pekna M, et al. Absence of glial fibrillary acidic protein and vimentin prevents hypertrophy of astrocytic processes and improves post-traumatic regeneration. J Neurosci. 2004;24(21):5016–21. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0820-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wallet MA, Rodriguez CA, Yin L, et al. Microbial translocation induces persistent macrophage activation unrelated to HIV-1 levels or T-cell activation following therapy. AIDS. 2010;24(9):1281–90. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e328339e228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Achim CL, Adame A, Dumaop W, et al. Increased accumulation of intraneuronal amyloid beta in HIV-infected patients. J Neuroimmune Pharmacol. 2009;4(2):190–9. doi: 10.1007/s11481-009-9152-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Khanlou N, Moore DJ, Chana G, et al. Increased frequency of alpha-synuclein in the substantia nigra in human immunodeficiency virus infection. J Neurovirol. 2009;15(2):131–8. doi: 10.1080/13550280802578075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Anthony IC, Ramage SN, Carnie FW, et al. Accelerated Tau deposition in the brains of individuals infected with human immunodeficiency virus-1 before and after the advent of highly active anti-retroviral therapy. Acta Neuropathol. 2006;111(6):529–38. doi: 10.1007/s00401-006-0037-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cysique LA, Vaida F, Letendre S, et al. Dynamics of cognitive change in impaired HIV-positive patients initiating antiretroviral therapy. Neurology. 2009;73(5):342–8. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181ab2b3b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Heaton RK, Franklin DR, Ellis RJ, et al. HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders before and during the era of combination antiretroviral therapy: differences in rates, nature, and predictors. J Neurovirol. 2011;17(1):3–16. doi: 10.1007/s13365-010-0006-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]