Abstract

A large repository of cryopreserved peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) samples was created to provide laboratories testing the specimens from human immunodeficiency virus-1 (HIV-1) vaccine clinical trials the material for assay development, optimization, and validation. One hundred thirty-one PBMC samples were collected using leukapheresis procedure between 2007 and 2013 by the Comprehensive T cell Vaccine Immune Monitoring Consortium core repository. The donors included 83 human immunodeficiency virus-1 (HIV-1) seronegative and 32 HIV-1 seropositive subjects. The samples were extensively characterized for the ability of T cell subsets to respond to recall viral antigens including cytomegalovirus, Epstein– Barr virus, influenza virus, and HIV-1 using Interferon-gamma (IFN-γ) enzyme linked immunospot (ELISpot) and IFN-γ/interleukin 2 (IL-2) intracellular cytokine staining (ICS) assays. A subset of samples was evaluated over time to determine the integrity of the cryopreserved samples in relation to recovery, viability, and functionality. The principal results of our study demonstrate that viable and functional cells were consistently recovered from the cryopreserved samples. Therefore, we determined that this repository of large size cryopreserved cellular samples constitutes a unique resource for laboratories that are involved in optimization and validation of assays to evaluate T, B, and NK cellular functions in the context of clinical trials.

Keywords: Peripheral blood mononuclear cells, Cryopreservation, Repository

1. Introduction

The evaluation of antigen-specific cellular responses induced by vaccine candidates in clinical trials by central laboratories requires extensive standardization and validation of the end-point assays. The central laboratories are usually performing these assays under Good Clinical Laboratory Practice (GCLP) guidelines and, therefore, are required to participate in External Proficiency testing (EP; see also Sanchez et al. in this issue) to monitor their ability to consistently generate results that are within established ranges for the cellular functions of interest (Ozaki et al., 2012; Sarzotti-Kelsoe et al., 2009). The validation of endpoint assays and the EP programs require testing the same samples overtime in replicate assays and the distribution of the same sample to multiple laboratories (Gill et al., 2010; Horton et al., 2007; Russell et al., 2003). In addition, bridging and comparative studies of different assays platforms usually require large size samples (Gill et al., 2010; Horton et al., 2007; Russell et al., 2003).

The development of effective vaccines in the past decades has demonstrated that vaccine immunogenicity evaluated as protection from HIV-1 infection might not simply correlate to a single effector function, cellular or humoral, of the human immune responses (Makedonas and Betts, 2010; Plotkin, 2008, 2013). In addition to validating assays for endpoint testing of clinical samples, there is a consistent request to develop novel assays that expand our understanding of the protective immune responses (Plotkin, 2013). The knowledge that has been gathered by the field on protection conferred by the immune response following HIV-1 natural infection in naive or vaccine recipient subjects suggests a role for T (Walker and McMichael, 2012), B (Bonsignori et al., 2012), and NK cellular subsets (Alter and Altfeld, 2009).

In order to perform the tasks indicated above, laboratories need access to large cell banks. We report here establishing a PBMC repository for the Comprehensive T cell Vaccine Immune Monitoring Consortium (CTVIMC) part of the Collaboration for the AIDS Vaccine Discovery network. The PBMC samples were collected using leukapheresis procedure from HIV-1 seronegative and seropositive donor samples with a wide range of viral antigen-specific functional responses. The samples were processed and stored within 8 hours from collection to retain viability, recovery, and functionality (see Garcia et al. in this issue). We report the characterization of these large cell banks and the results of the longitudinal quality control procedures that we have implemented to verify the functional integrity of the samples.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Samples

One hundred and thirty-one samples from HIV-1 seronegative and seropositive donors were collected between June 2007 and July 2013 at Duke University, Durham, North Carolina, USA. Donors provided written informed consent, and study protocols had been reviewed and approved by the Duke University Institutional Review Board. All the samples were collected, processed, and cryopreserved according to the procedures described by Garcia and collaborators at Duke University (see Garcia et al. in this same issue).

2.2. Biological characterization

The donors were characterized for their profile of humoral immune responses against infectious agents of interest including CMV, influenza, adenovirus, poxvirus, and hepatitis B. All samples were also HLA typed for class I alleles. The information is not presented, but is available upon request to this program.

2.3. Functional characterization

We determined recovery and viability of all samples at time of collection and within 4 weeks from time of cryopreservation using the Guava PC analyzer as previously described (Bull et al., 2007).

We also assessed cellular functions using interferon-gamma enzyme linked immunospot (IFN-γ ELISpot) and intracellular cytokine staining (ICS) assays as described below. The functionality was tested for all samples within 4 weeks from collection and, in addition, every 6 months in five samples representing different levels of responses and monthly in one low/medium responder. We also selected a subset of ten samples to measure cellular function using both assays 5–6 years after sample acquisition.

2.4. Peptide pools

Twenty-three peptides that represent the CMV, EBV, and influenza MHC class I restricted epitopes constituted one peptide pool as previously described (CEF pool) (Currier et al., 2002). The second pool represented the sequence of the CMV pp65 protein with 15 amino acid peptides overlapping by 11 amino acids. The peptide pools utilized for this EP program were purchased from JPT Peptide Technologies (Berlin, Germany). The peptides' purity was >90% as defined by the certificate of analysis provided by the manufacturer.

The global potential T cell epitope (PTE) peptide pools (HIV-1 Gag, Env, Pol and Nef) utilized to determine the frequency of HIV-1-specific T cell responses were obtained by the National Institute of Health Research Reagent Program (https://www.aidsreagent.org). The 15 amino acid peptides were pooled as previously reported based on the frequency of their recognition (Li et al., 2006) for the ICS assay, whereas, for the ELISpot assay, the peptides were pooled based on the region they represented to eliminate any duplicate responses in more than one pool due to the recognition of the variants of the same region.

2.5. Interferon-gamma (IFN-γ) ELISpot assay

Cryopreserved cells were thawed, counted, and resus-pended in complete medium (R10) RPMI 1640 (Gibco; Grand Island, NY) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Gemini Bio-Products; West Sacramento, CA) and 5% Pen-Strep-Glut (Gibco; Grand Island, NY). Cell suspensions at 2 × 106 cells/mL were incubated overnight at 37 °C, 5% CO2 in 50 mL tubes. The IFN-γ ELISpot assay was performed using Mabtech pre-coated plates (Mabtech; Mariemont, Ohio); Mabtech biotinylated anti-IFN-γ 7-B6-1 monoclonal antibody (Ab) was used as the detecting Ab; NovaRED substrate (Vector Laboratories; Burlingame, CA) was used to reveal the presence of spots. Spots formed by IFN-γ-secreting cells were counted with an automated ImmunoSpot plate reader (Cellular Technologies, Cleveland Ohio), and results are presented as spot-forming cells (SFC) as indicated in each figure. For all samples, the cells were evaluated for their functionality using the CEF and CMVpp65 peptide pools at the concentration of 1 µg/mL. For the HIV-1 seropositive samples, additional testing was performed using the PTE peptides. This assay was performed following Good Clinical Laboratory Procedures guidelines; detailed Standard Operating Procedures are available upon request.

2.6. Intracellular cytokine staining (ICS) assay

The screening of the leukapheresis samples by ICS assay was performed using the following conjugated Ab panel in BD Lyoplate™ (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA): CD3 APC H7 (clone SK7), CD4 V450 (clone SK3), CD8 PerCPCy5.5 (clone SK1), CD45RO PE Cy7 (clone UCHL1), CD27 APC (clone L128), IL-2 PE (clone 5344.111), and IFN-γ Alexa 700 (clone B27). The following panel was utilized to test the functionality of the samples 5–6 years after collection (results reported in Results section for longevity of functionality assessed by ICS): CD3 Cy7APC (BD, clone SP34-2), CD28 Cy5PE (BD, clone CD28.2), CD45RA Cy7PE (BD, clone L48), CCR7 Ax680 (R&D, clone 150503), CD4 ECD (Beckman Coulter, clone SFCl12T4D11), CD8 PacBlue (BD, clone RPA-T8), IFN-γ APC (BD, clone B27), and IL-2 PE (BD, clone MQ1-17H12). The LIVE/DEAD® Fixable Aqua Dead Cell Stain Kit (Life technology, InVitrogen) was utilized in both panels to exclude non-viable cells from the analyses. The concentration used for each Ab and the viability dye was defined according to published procedures (Lamoreaux et al., 2006; Perfetto et al., 2006b).

Cryopreserved PBMCs were thawed, washed and rested overnight before use as reported for the IFN-γ ELISpot assay. Cells were removed from overnight incubation, counted, then washed and resuspended to 10 × 106 cells/mL in R10 media. One-hundred microliters of the cell suspension was added to each well of a 96-well plate. Peptide and superantigen Staphylococcus aureus enterotoxin B (SEB; Sigma-Aldrich; St. Louis, MO), used as positive control, solutions were prepared and added to the cells for a final volume of 200 µL in each well. Peptides were added to attain a final concentration in each well of 2.5 µg/mL. Negative control wells received 100 µL of cell suspension and 100 µL of R10 media. Brefeldin-A (Sigma-Aldrich; St. Louis, MO) was present in all wells at a concentration of 10 µg/mL. Plates were incubated for 6 hours at 37 °C, 5% CO2. At the end of the incubation plates were wrapped in foil and transferred to 2–8 °C for next day antibody staining. On the following day, the plates were removed from the fridge and centrifuged at 863 ×g for 4 minutes. Next, cells were washed with 200 µL of PBS per well and centrifuged at 863 ×g for 4 minutes. Cells were then resuspended in 50 µL viability staining mix and incubated for 20 minutes at room temperature. Fifty (50) microliters of the surface staining mix was then added and incubated for 20 minutes at room temperature. Cells were subsequently washed once with 100 µL of wash buffer (D-PBS supplemented with 1% FBS) and centrifuged for 4 minutes at 863 ×g. The wash step was then repeated with 200 µL of wash buffer. The cells were then resuspended in 100 µL BD Cytofix/Cytoperm (BD Biosciences; San Jose, CA) and incubated for 20 minutes at 4 °C. After incubation, cells were washed twice in 1× BD Perm Wash (BD Biosciences; San Jose, CA) and centrifuged for 4 minutes at 863 ×g. Then, all cells were resuspended in 100 µL of intracellular staining mix and incubated for 20 minutes at room temperature. Finally, cells were washed three times in 1× BD Perm Wash (BD Biosciences; San Jose, CA), centrifuged for 4 minutes at 863 ×g, and resuspended in 250 µL 1% formalin solution (Sigma-Aldrich; St. Louis, MO). The samples were acquired within 24 hours using a custom made BD LSRII (BD Biosciences; San Jose, CA). Instrument configuration has been previously reported (Pollara et al., 2011). Optimization and daily standardization of the instrument were performed according to published procedures (Perfetto et al., 2006a). Data analysis was performed using FlowJo 9.6.4 software (TreeStar). Gates were set to include singlet events, live CD3+ cells, lymphocytes, and CD4+ and CD8+ functional subsets as illustrated (Supplemental Fig. 1).

2.7. Antibody dependent cellular cytotoxicity (ADCC)

The previously described ADCC assay (Pollara et al., 2011) was utilized to evaluate the function of NK cells recovered from cryopreserved samples. The monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) utilized in the assay have been already described in Ferrari et al. (2011) and optimized for binding to the Fcγ-Receptor IIIa (Fcγ-R IIIa) according to Shields et al. (2001). Dr. Kijak determined the Fcγ-R IIIa genotype of the donors using the SNP rs396991 and TaqMan SNP Genotyping Pre-Validated Assay (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA).

2.8. B cell enzyme linked immunospot (B cell ELISpot)

The ability of the B cell present in the cryopreserved samples to produce IgG in response to polyclonal and recall antigens (subtype B HIV-1 BaL recombinant glycoprotein 140) was tested using the previously published method (Walsh et al., 2013). The Keyhole Limpet Hemocyanin (KLH, Pierce, Rockford, IL) was used as negative control. The TLR7/8 R848 and TLR9 CpG-C agonists were used as co-stimulatory molecules in the B cell activation culture system utilized to expand the B cell populations according to the published procedure.

2.9. Statistical analyses

Statistical analyses were performed using the Prism software (Graphpad) or SAS 9.2. The methods are indicated throughout the article.

3. Results

3.1. Sample collection

All leukopaks were obtained through proper IRB approved protocols at Duke University. Each leukopak was processed as a fresh sample and cryopreserved within approximately 6 hours of the apheresis collection. Cryopreserved vials were then inventoried into the CTVIMC PBMC repository. An average of 348 vials of PBMC (average for HIV- was 331 and for HIV+, 394 vials) containing 20 × 106 PBMC per vial were stored from a single leukopak. Each vial was labeled with a unique global specimen identification number. Vials were split and stored in two different LN2 freezers for redundancy. LN2 freezers were in a secured facility and were monitored 24/7 for temperature. Currently, the CTVIMC repository has over 31,490 cryopreserved PBMC vials. Since the inception of the CTVIMC repository in August 2007, a total of 43,148 PBMC vials have been cataloged. Of those, 11,653 vials have been shipped out from the repository.

3.2. Donor demographics

Since August 2007, the CTVIMC repository has obtained a total of 131 leukopaks from 115 different individuals. All the information regarding the donor demographics is reported in Table 1. Of the total leukopaks, 95 were from healthy noninfected, HIV-1 seronegative and 36 were from seropositive HIV-1 infected subjects (Table 1). Multiple leukapheresis donations were obtained from several donors.

Table 1.

PBMC repository donor demographics.

| Female | Male | |

|---|---|---|

| Totala | 44 | 71 |

| Age (years) | ||

| 18–30 | 15 | 25 |

| 31–40 | 9 | 14 |

| 41–50 | 14 | 22 |

| 51–60 | 6 | 10 |

| Ethnicity | ||

| White | 34 | 46 |

| Black | 8 | 21 |

| Asian | 1 | 2 |

| Hispanic | 1 | 2 |

| HIV status | ||

| Seronegative | 40 | 43 |

| Seropositive | 4 | 28 |

| On anti-retroviral Rx | ||

| Yes | 4 | 21 |

| No | 0 | 7 |

All numbers represent the absolute number for each category.Table 2

3.3. Initial sample viability and recovery (≤4 weeks)

For all 131 cryopreserved samples, viability and recovery were assessed within 4 weeks from time of processing and evaluated immediately following thawing (Day 1) and after overnight resting (Day 2), and the data are reported in Table 2. We observed a viability greater than 70% as requested by the Immunology Quality Assessment (IQA) program (Weinberg et al., 2009, 2010) at Day 1 (average ± standard deviation 91.49 ± 3.5; range 79.3–99.1) (Table 2). The viability was also greater than 70% at Day 2 in all but two samples (average ± standard deviation 92.9 ± 4.8; range 65.1–98.5).

Table 2.

Viability and recovery of cryopreserved samples at week 4.

| Viability Day 1 |

Viability Day 2 |

Recovery Day 1 |

Recovery Day 2 |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of samples | 131 | 131 | 131 | 131 |

| Mean ± SDa | 91.5 ± 3.5 | 92.9 ± 4.8 | 99.4 ± 16.8 | 87.9 ± 15.9 |

| Range | 79.3–99.1 | 65.1–98.5 | 63.5–173.0 | 56.5–159 |

SD = standard deviation.

The average recovery was ≥99.4 and 87.9%, with ranges of 63.5–173 and 56.5–159 at Day 1 and Day 2, respectively (Table 2), and met laboratory's standard of >50% recovery (Weinberg et al., 2009, 2010).

We did not observe any gender-related differences in samples. The average viability for Days 1 and 2 was 91.1% and 93.8% for female donors and 91.9% and 92.4% for male donors.

3.4. CEF- and CMVpp65-specific T cell responses

We used the CEF and CMVpp65 peptide pools as described in Materials and methods to screen the cryopreserved samples using IFN-γ ELISpot and IFN-γ/IL-2 ICS for T cell responses against recall antigens. The CEF peptide pool was utilized for all the donors using the IFN-γ ELISpot assay, but only the HIV-1 seronegative donors were tested by IFN-γ/IL-2 ICS against CEF peptide pool.

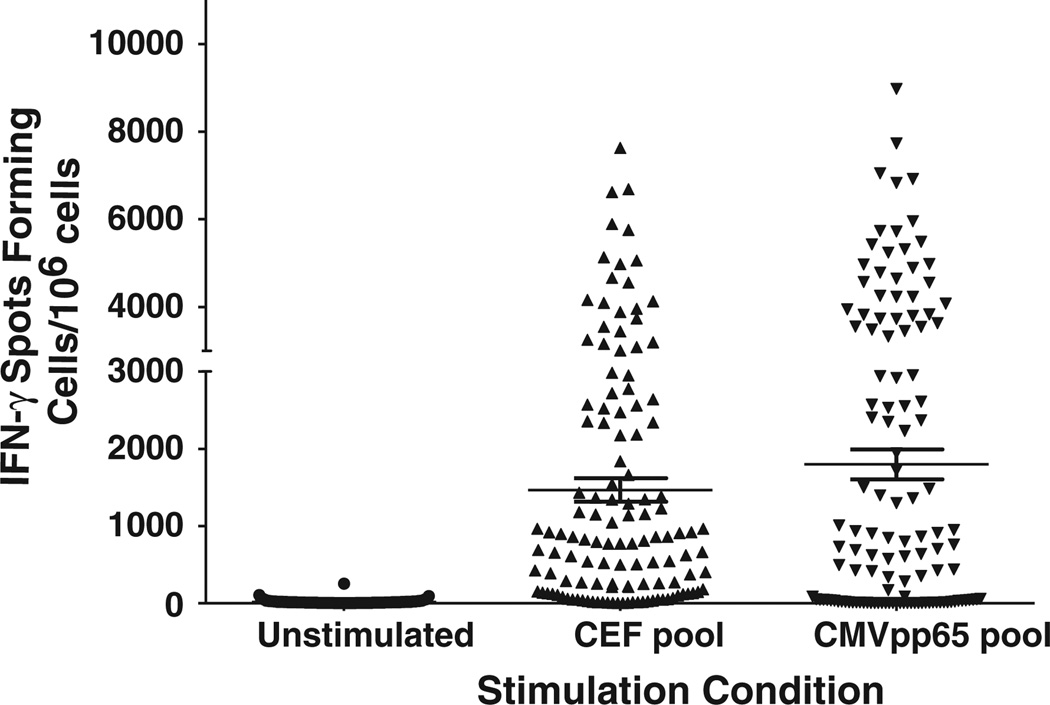

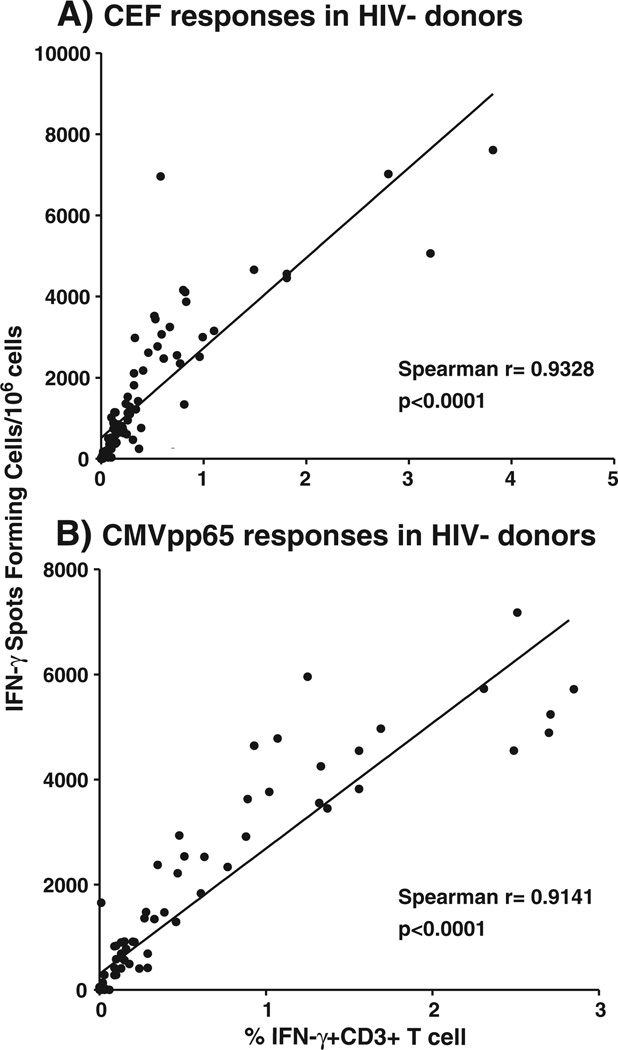

Among the 126 samples tested thus far, we observed responses directed against the CEF pool in 105 (83%) by IFN-γ ELISpot (Fig. 1; Table 3). The frequency of these responses correlated significantly with the total IFN-γ responses observed in the CD3+ T cell subset using ICS (Spearman r = 0.9328 and p < 0.0001) (Table 3; Fig. 2a).

Fig. 1.

IFN-γ ELISpot responses. The IFN-γ ELISpot responses are reported as spot forming cells per 106 PBMC (y-axis). The stimulation conditions reported on the x-axis were unstimulated (medium only representing the background), the CEF peptide pool and CMV pp65 peptide pool. The mean and the standard error of the mean are indicated by the line and whiskers.

Table 3.

Frequency of CEF and CMVpp65 responses.

| Spot forming cells/106 cells |

% Viable CD3+IFN-γ T cells |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median | SDa | Range | p Valueb | Median | SDa | Rangec | p Valueb | ||

| No Ag | Female | 12.5 | 21.8 | 1.5–106 | 0.064 | 0.012 | 0.121 | 0.00–0.84 | 0.275 |

| Male | 8.0 | 30.3 | 0–251 | 0.013 | 0.017 | 0.00–0.01 | |||

| CEF | Female | 850 | 1363.8 | 12–6958 | 0.377 | 0.194 | 0.262 | 0.00–1.10 | 0.537 |

| Male | 680 | 1883.4 | 0–7607 | 0.140 | 0.812 | 0.00–3.82 | |||

| CMVpp65 | Female | 582 | 2125.8 | 0–8975 | 0.437 | 0.124 | 1.001 | 0.00–5.50 | 0.803 |

| Male | 920 | 2110.8 | 0–7732 | 0.174 | 0.811 | 0.00–3.13 | |||

SD = standard deviation.

Non-adjusted p-values from Mann–Whitney U test for comparisons of female and male results.

Background greater than 0.068 in samples from one female and two male donors.

Fig. 2.

Correlation between frequency of IFN-γ T cell responses detected by ELISpot and intracellular cytokine staining. The frequency of IFN-γ T cell responses detected by ELISpot is reported as spot forming cells per 106 PBMC (y-axis). The frequency of the total viable CD3+IFN-γ+ T cells is reported on the y-axis. The Spearman correlation r values were determined using Prism software for responses to: A) the CEF peptide pool; and B) the CMV pp65 peptide pool. The p values for significance are reported in each figure.

Anti-CMV responses were detected in 81 (64%) of the donors (Fig. 1; Table 3). The frequency of these responses also correlated significantly with the total IFN-γ responses observed in the CD3+ T cell subset using ICS (Spearman r = 0.9141 and p <0.0001) (Fig. 2b). Among the responders, 56 (44%) had detectable CD4+ responses against the CMVpp65 pool as detected by ICS with an average response of 0.21% viable CD3+ T cells (range 0.0–2.02). Interestingly, the median of the CMV T cell responses was higher in the HIV-1 infected individuals (3378 SFC/106 cells, range 0–8975) compared to the HIV-1 seronegative individuals (419 SFC/106 cells, range 0–7178).

We did not observe any significant difference in the frequency of the CEF and CMV T cell responses in the female group compared to the male group using both ELISpot and ICS assays (Table 3; non-adjusted p-values always >0.064 from Mann–Whitney U test).

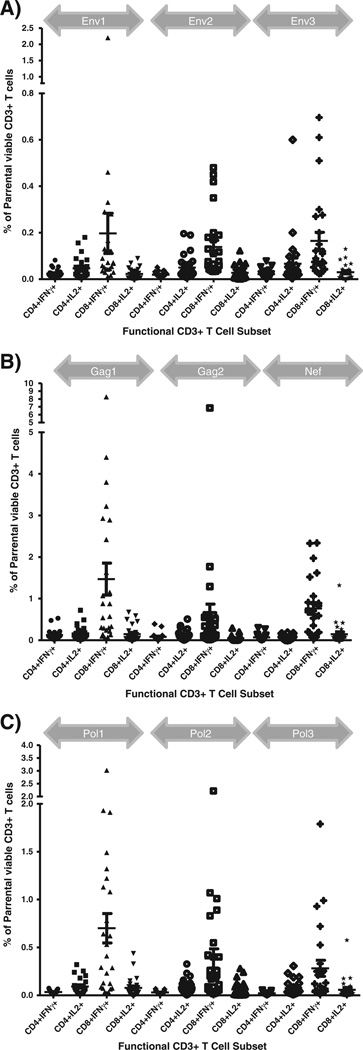

3.5. Anti-HIV T cell responses

The analyses of the anti-HIV-1 responses by ICS revealed responders against each antigenic region tested (Table 4). The CD8+ T cell responses were predominantly detected against Gag (n = 17), followed by Nef (n = 15), Pol (n = 14), and Env (n = 7). The CD4+ T cell responses were only detected against Gag (n = 5) and Nef (n = 2) (Fig. 3). We did not detect CD4+ T cell responses in the absence of concomitant CD8+ T cell responses.

Table 4.

Frequency of IFN-γ anti-HIV-1T cell responses by ICS.

| Env |

Gag |

Nef |

Pol |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CD4+ | CD8+ | CD4+ | CD8+ | CD4+ | CD8+ | CD4+ | CD8+ | |

| Responders (n) | 0 | 7 | 5 | 17 | 2 | 15 | 0 | 14 |

| Average | 0.51 | 0.37 | 1.71 | 0.26 | 1.11 | 0.88 | ||

| SDa | 0.46 | 0.11 | 2.01 | 0.65 | 0.63 | |||

| Range | 0.21–1.99 | 0.20–0.50 | 0.22–8.04 | 0.26–0.27 | 0.28–2.30 | 0.21–2.81 | ||

The values represent the frequency of the CD4+ and CD8+ cells based on the parental population, i.e. singlets/viable/CD3+/lymphocytes as reported in the method section.

SD = standard deviation.

Fig. 3.

Frequency of HIV-1-specific T cell responses by intracellular cytokine assays. The frequency of viable CD3+ T cells against the PTE peptide pools representing the HIV-1 Env (A), Gag (B), Nef (B), Pol (C) gene products are reported on the y-axis. The responses to each peptide pool are grouped according to the gray arrows above each plot. The cell CD4+ and CD8+ CD3+ T cell subsets responding as detectable by the production of IFN-γ and IL-2 are reported on the x-axis.

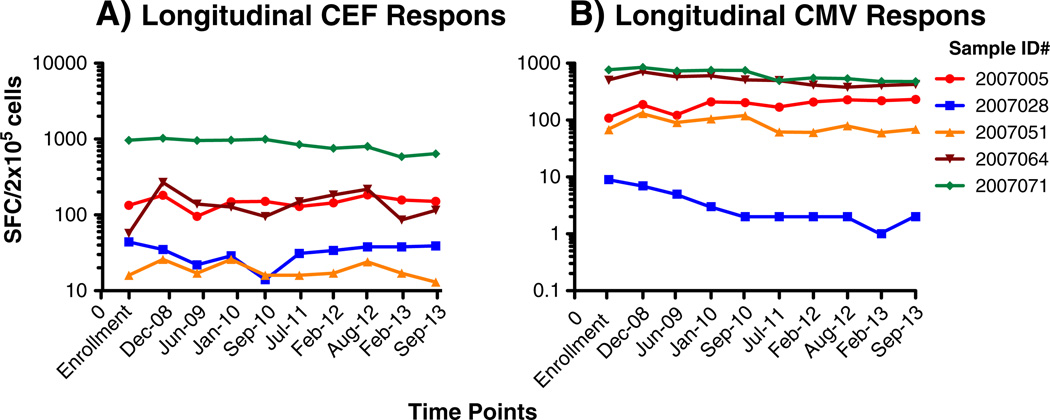

3.6. Longitudinal quality assessment of the cryopreserved samples by IFN-γ ELISpot

We have performed a semiannual quality assessment of stored specimens to assure that long term cryopreservation does not negatively impact their viability, recovery, and function. Five samples originally selected based on their range of responses following CEF and CMVpp65 peptide pools stimulations have been retested every 6 months since cryopreservation. Mixed effects models in SAS 9.2 were used to assess trends over time for viability, recovery, and functionality. The α level was set at 0.05 for these analyses without any correction for multiple testing. According to the longitudinal analysis of the responses to recall antigens in the five reference samples, we did not observed any negative trend for Day 2 viability (p > 0.24, range 0.24–0.97) and recovery (p > 0.9, range 0.09–0.51). The analysis of the antigen-specific responses did not reveal any change in the hierarchy of the responses among the donors as well as any significant decline of detectable CEF and CMVpp65 responses in three out five samples (Fig. 4). We observed a significant decline in two samples (064 and 071), and this decline was limited to the CMV in 064 (p <0.0001) and observed for both CEF and CMV responses in 071 (p <0.0001 in both) (Fig. 4). Both samples were collected from HIV infected donors. Therefore, we tested five additional samples collected from HIV seropositive individuals for anti-CEF and anti-CMV responses. The analysis of the individual SFC/2 × 105 cells replicates using the paired t-test did not reveal any significant difference between the responses detected at enrollment and in December 2012. Moreover, for each set of responses the coefficient of pairing was significant (0.99 and 0.90, respectively; data not shown).

Fig. 4.

Longitudinal quality assessment of functional recall antigens responses. Five samples selected to represent a range of positive responses to the recall antigens represented by the CEF (A) and CMVpp65 (B) peptide pools are reported as spot forming cells per 106 PBMC. Each line represents the longitudinal assessment for each individual sample as reported in the figure legend. The time of testing are reported on the y-axis.

3.7. Functional integrity of cryopreserved samples by ELISpot and ICS

Because we observed a decline in the responses by HIV-1 seropositive donors, we measured the functionality of 10 samples both by IFN-γ ELISpot and ICS assays at the time of acquisition in the repository (2007–2008) and 5–6 years later (2013). The CEF and CMV peptide pools were used for these comparisons. The results obtained from this round of testing (T2) were compared to those obtained at the time the samples were first obtained and deposited in our repository (T1). We also compared the frequency of total IFN-γ+CD3+ T cell detected by ICS and compared to the frequency of SFC/ 2 × 105 cells detected by ELISpot at both T1 and T2. The Spearman test was utilized to determine the presence of significant correlation between the results obtained with each assay. The Spearman values, calculated in SAS 9.2, of each comparison are reported in Table 5. All comparisons revealed that the results were significantly correlated and indicated that no decline in the responses was observed over time in these additional ten samples. These results suggest that the decline observed in the two HIV seropositive described in Section 3.6 is not a generalizable to other HIV seropositive donor samples.

Table 5.

Spearman analysis for correlations between the Ag specific responses at enrollment (T1) and after 5 years of storage (T2).

| Variable | CEF ICS T1 | CEF ELISpot T2 | CMV ICS T1 | CEF ELISpot T2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CEF ELISpot T1 | 0.76 | 0.99 | ||

| CEF ICS T2 | 0.95 | 0.87 | ||

| CMV ELISpot T1 | 0.99 | 0.98 | ||

| CMV ICS T2 | 0.95 | 0.98 |

The table reports the correlation values obtained by Spearman analysis for the responses detected by IFN-γ ELISpot intracellular cytokine staining (ICS) at enrollment (T1) and after 5 years of storage in the repository (T2). The responses by ICS were evaluated using the total frequency of IFN-γ+CD3+ T cells. A total of 10 samples were evaluated. All correlations were significant with p < 0.05.

Lastly, we utilized the data obtained from these ten samples using the ICS assay to determine whether the biologically relevant responses defined as CD8 responses to CEF and CMVpp65 and CD4 responses to CMVpp65 were preserved at T2 compared to T1. We did not observe any significant difference in the frequency of responding cells in either subset detected at each time point (paired t-test with p > 0.05).

3.8. Evaluation of ADCC activity using NK cells isolated from cryopreserved repository samples

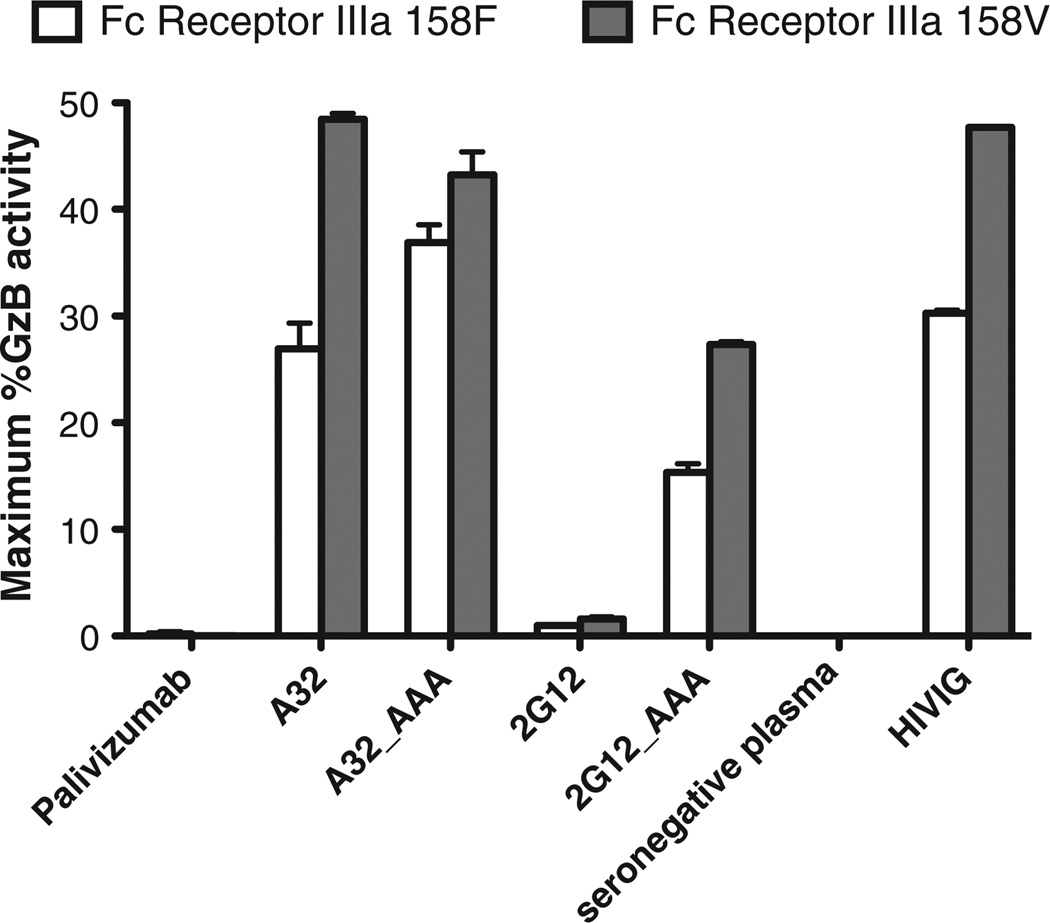

We have previously determined that cryopreserved PBMC samples and NK cells isolated from cryopreserved PBMC generate ADCC assay results consistent with those observed using freshly collected effector cells (Pollara et al., 2011). The use of cryopreserved leukapheresis samples can improve experimental consistency by testing large batches with effector cells collected from a single donor at a single time point. In addition, cryopreserved samples can be screened post-collection to identify samples with particular characteristics. We have genetically screened repository samples to identify those homozygous for the low affinity (158F) and high affinity (158V) allelic variants of Fcγ-Receptor IIIa (Fcγ-R IIIa). NK cells were purified from a representative donor for each Fcγ-R IIIa phenotype by negative selection and used as effector cells to measure ADCC activity of monoclonal and polyclonal antibodies against A1953 chronically HIV-1-infected target cell line (Fig. 5) (Pollara et al., 2011). The HIV specific monoclonal antibodies A32 and 2G12 were produced by recombinant techniques as IgG1, and IgG1 engineered to include three alanine substitutions at positions 298, 333, and 334 that are known to increase ADCC activity mediated by Fcγ-R IIIa (Shields et al., 2001). We observed higher ADCC activities (average 1.6 fold, range 1.2–1.8 fold) for the HIV-specific monoclonal antibodies and the polyclonal IgG preparation, HIVIG, when assays were performed with NK cells expressing the high affinity 158V Fcγ-R IIIa variant compared to those performed with NK cells expressing the lower affinity variant. Consistent with previous observations, optimization of the monoclonal antibody Fc region by alanine substitution mutations increased ADCC activity (average 8.7 fold, range 0.9– 17 fold) mediated by both 158F and 158V Fcγ-R IIIa-bearing NK cells (Shields et al., 2001).

Fig. 5.

Functionality of cryopreserved NK cell-mediated ADCC. Cryopre-served human PBMC samples were genetically screened to identify donors with low affinity (158F, white bars) and high affinity (158V, grey bars) allelic variants of FcγR IIIa. The results are reported as the maximum % Granzyme B (%GzB) activity on the y-axis. The target cells were represented by the A1953 HIV-1 chronically infected target cell line. The purified NK populations were tested at an effector to target cell ratio of 5:1. Palivizumab (anti-RSV mAb) was used as negative control along with the plasma collected from a HIV-1 seronegative donor (seronegative plasma). The polyclonal IgG preparation, HIVIG, was tested as a positive control. The A32 and 2G12 mAb are anti-HIV-1 Env gp120 specific mAb tested as expressed with a consensus or AAA variant sequence of the Fc region. The height of each bar represents the average of two independent experiments, and the whiskers represent the standard error mean.

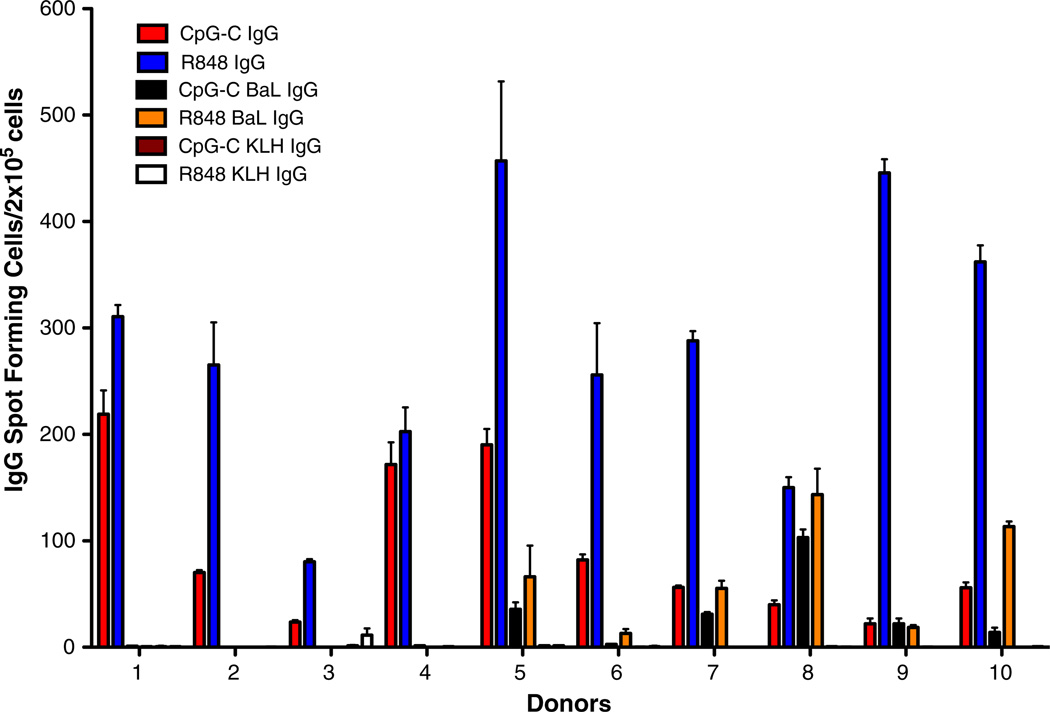

3.9. B cell ELISpot

The B cell ELISpot assay was performed utilizing the published methodology to test the presence of IgG-producing B cell in the cryopreserved samples (Fig. 6). Ten samples were selected based on the presence of T cell responses to HIV-1 peptide pools and stimulated with the TLR agonist in absence or in presence of the HIV-1 subtype B BaL gp140. The total IgG and BaL gp140-specific IgG responses were detected as published. Polyclonal IgG production was detected in 10 out of ten samples, and the amount of IgG produced by costimulation with R848 (average SFC/105 cells = 281; range 80–457) was always significantly greater than by costimulation with CpG-C (average SFC/105 cells = 93; range 22–219) (Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed rank test; p = 0.002); The pairing of the results was also significant (Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed rank test; p = 0.026). HIV-1 BaL gp140-specific IgG responses were observed in 4 out of ten individuals, and responses detected in the R848-costimulated condition (average SFC/105 cells = 41; range 0–143) were greater than in the CpG-C-costimulated condition (average SFC/105 cells = 21; range 0–103) without reaching statistical significance (Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed rank test; p = 0.1).

Fig. 6.

Functionality of cryopreserved B cells detected by ELISPOT assay. Cryopreserved PBMCs were stimulated in the presence of two co-stimulatory TLR agonists CpG-C and R848 to detect the production of total or HIV-1 BaL gp140-specific IgG-producing B cells. The KLH reagent was used as negative control to determine background IgG detection. The results are reported as average of the IgG spot forming cells per 2 × 105 cells in triplicate wells, and the whiskers represent the standard error mean. Each bar represents a different condition for detection of IgG producing cells, and the corresponding colors are depicted in the figure.

4. Discussion

The evaluation of cellular responses induced by HIV-1 candidates vaccines has required an extensive effort to validate cellular-based assay for use in clinical trials (Horton et al., 2007; Russell et al., 2003). In addition, a consistent effort has been made to establish external proficiency testing programs (Cox et al., 2005) and to adhere to GCLP guidelines (Sarzotti-Kelsoe et al., 2009). The optimization, validation, and proficiency testing of the assays require collection and storage of large banks of PBMC samples. In this article, we have reported the development of a repository of cryopreserved samples that can provide laboratories with the necessary number of cells to harmonize and monitor the performance of cellular assays on large scale. The samples have been collected over a period of 7 years (2007–2013) and tested for their functional integrity over time using the ELISpot and ICS assays. We have demonstrated that these samples maintain the necessary recovery and viability to generate reproducible functional results over time. In addition, we have reported about the collection, storage, and longitudinal assessment of the samples functionality, information deemed of importance according to the most current guidelines suggested by the Minimal Information about T cell Assays (MIATA) (Britten et al., 2012; Janetzki et al., 2013).

These PBMC samples have been successfully used to harmonize the IFN-γ ELISpot T cell assay across four different CTVIMC laboratories (Gill et al., 2010), as well as to develop assays for testing NK-mediated ADCC (Pollara et al., 2011) and B cell functions (Walsh et al., 2013). The latter two assays were among those used as primary and secondary assays to evaluate correlates of risk of HIV-1 infections in the RV144 ALVAC/AIDSVax® clinical trial (Haynes et al., 2012). It should be noted that most of the studies performed in support to vaccine clinical trials are utilizing cryopreserved cellular samples. The testing of cryopreserved T and NK cells has already been bridged to that of samples collected from fresh blood (Horton et al., 2007; Pollara et al., 2011; Russell et al., 2003), whereas there is still unclear notions on the effect of cryopreservation on the recovery of the functional B cell populations (Olemukan et al., 2010; Reimann et al., 2000). This clinical trial shed new light on the type and specificity of immune responses that correlated with lower risk of HIV-1 infection. However, the best combination of humoral and cellular immune responses that may increase the breadth and longevity of these protective immune responses and the role of T follicular helper cells and other T cells could have in this process remain to be determined (Locci et al., 2013). The specificity and role of T follicular helper cells will be explored in more detail in the future and these PBMC samples could help in developing new panels of reagents and assays for characterizing this CD4 T cell subset. In addition, the utilization of recombinant CMV vectors to generate protection from SIV infection has revealed the protective role of MHC class II-restricted CD8+ T cell mediated responses (Hansen et al., 2013). Once again, these data indicate the need to develop new assays to assess the immunogenicity of HIV-1 vaccine candidates. The sample collected and stored by the CTVIMC repository may be important in developing these new panels of reagents and assays.

In conclusion, we have established and maintained a PBMC repository by the Comprehensive T cell Vaccine Immune Monitoring Consortium (CTVIMC). The unique value of this resource for the CTVIMC and other groups within and outside the CAVD network lies in availability of high quality, characterized specimens obtained via leukapheresis thus offering large number of vials from each donor. This is crucial in any assay development or optimization activities where testing has to be repeated or performed across different laboratories. These specimens are available to the whole CAVD network upon request via internal CAVD portal (www.cavd.org) and can be easily accessed by other investigators outside the consortium upon request to the CTVIMC leadership.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgement

This work was supported by a Collaboration for AIDS Vaccine Discovery (CAVD)/Comprehensive T Cell Vaccine Immune Monitoring Consortium (CTVIMC) grant from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation (Grant ID# OPP1032325).

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jim.2014.04.005.

References

- Alter G, Altfeld M. NK cells in HIV-1 infection: evidence for their role in the control of HIV-1 infection. J. Intern. Med. 2009;265:229. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2008.02045.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonsignori M, Alam SM, Liao H-X, Verkoczy L, Tomaras GD, Haynes BF, Moody MA. HIV-1 antibodies from infection and vaccination: insights for guiding vaccine design. Trends Microbiol. 2012;20:532. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2012.08.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Britten CM, Janetzki S, Butterfield LH, Ferrari G, Gouttefangeas C, Huber C, Kalos M, Levitsky HI, Maecker HT, Melief CJM, O’Donnell-Tormey J, Odunsi K, Old LJ, Ottenhoff THM, Ottensmeier C, Pawelec G, Roederer M, Roep BO, Romero P, van der Burg SH, Walter S, Hoos A, Davis MM. T cell assays and MIATA: The essential minimum for maximum impact. Immunity. 2012;37:1. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bull M, Lee D, Stucky J, Chiu Y-L, Rubin A, Horton H, McElrath MJ. Defining blood processing parameters for optimal detection of cryopreserved antigen-specific responses for HIV vaccine trials. J. Immunol. Methods. 2007;322:57. doi: 10.1016/j.jim.2007.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox JH, Ferrari G, Kalams SA, Lopaczynski W, Oden N, D’souza MP Elispot Collaborative Study Group. Results of an ELISPOT proficiency panel conducted in 11 laboratories participating in international human immunodeficiency virus type 1 vaccine trials. AIDS Res. Hum. Retroviruses. 2005;21:68. doi: 10.1089/aid.2005.21.68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Currier JR, Kuta EG, Turk E, Earhart LB, Loomis-Price L, Janetzki S, Ferrari G, Birx DL, Cox JH. A panel of MHC class I restricted viral peptides for use as a quality control for vaccine trial ELISPOT assays. J. Immunol. Methods. 2002;260:157. doi: 10.1016/s0022-1759(01)00535-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrari G, Pollara J, Kozink D, Harms T, Drinker M, Freel S, Moody MA, Alam SM, Tomaras GD, Ochsenbauer C, Kappes JC, Shaw GM, Hoxie JA, Robinson JE, Haynes BF. An HIV-1 gp120 envelope human monoclonal antibody that recognizes a C1 conformational epitope mediates potent antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity (ADCC) activity and defines a common ADCC epitope in human HIV-1 serum. J. Virol. 2011;85:7029. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00171-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gill DK, Huang Y, Levine GL, Sambor A, Carter DK, Sato A, Kopycinski J, Hayes P, Hahn B, Birungi J, Tarragona-Fiol T, Wan H, Randles M, Cooper AR, Ssemaganda A, Clark L, Kaleebu P, Self SG, Koup R, Wood B, McElrath MJ, Cox JH, Hural J, Gilmour J. Equivalence of ELISpot assays demonstrated between major HIV network laboratories. PLoS One. 2010;5:e14330. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0014330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen SG, Sacha JB, Hughes CM, Ford JC, Burwitz BJ, Scholz I, Gilbride RM, Lewis MS, Gilliam AN, Ventura AB, Malouli D, Xu G, Richards R, Whizin N, Reed JS, Hammond KB, Fischer M, Turner JM, Legasse AW, Axthelm MK, Edlefsen PT, Nelson JA, Lifson JD, Fruh K, Picker LJ. Cytomegalovirus vectors violate CD8+ T cell epitope recognition paradigms. Science. 2013;340:1237874. doi: 10.1126/science.1237874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haynes BF, Gilbert PB, McElrath MJ, Zolla-Pazner S, Tomaras GD, Alam SM, Evans DT, Montefiori DC, Karnasuta C, Sutthent R, Liao H-X, DeVico AL, Lewis GK, Williams C, Pinter A, Fong Y, Janes H, DeCamp A, Huang Y, Rao M, Billings E, Karasavvas N, Robb ML, Ngauy V, de Souza MS, Paris R, Ferrari G, Bailer RT, Soderberg KA, Andrews C, Berman PW, Frahm N, De Rosa SC, Alpert MD, Yates NL, Shen X, Koup RA, Pitisuttithum P, Kaewkungwal J, Nitayaphan S, Rerks-Ngarm S, Michael NL, Kim JH. Immune-correlates analysis of an HIV-1 vaccine efficacy trial. N. Engl. J. Med. 2012;366:1275. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1113425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horton H, Thomas E, Stucky J, Frank I, Moodie Z, Huang Y, Chiu Y, Mcelrath M, Derosa S. Optimization and validation of an 8-color intracellular cytokine staining (ICS) assay to quantify antigen-specific T cells induced by vaccination. J. Immunol. Methods. 2007;323:39. doi: 10.1016/j.jim.2007.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janetzki S, Hoos A, Melief CJM, Odunsi K, Romero P, Britten CM. Structured reporting of T cell assay results. Cancer Immun. 2013;13:13. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamoreaux L, Roederer M, Koup R. Intracellular cytokine optimization and standard operating procedure. Nat. Protoc. 2006;1:1507. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2006.268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li F, Malhotra U, Gilbert PB, Hawkins NR, Duerr AC. Peptide selection for human immunodeficiency virus type 1 CTL-based vaccine evaluation. Vaccine. 2006;24:6893. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2006.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Locci M, Havenar-Daughton C, Landais E, Wu J, Kroenke MA, Arlehamn CL, Su LF, Cubas R, Davis MM, Sette A, Haddad EK, Poignard P, Crotty S. Human circulating PD-1+CXCR3-CXCR5+ memory Tfh cells are highly functional and correlate with broadly neutralizing HIV antibody responses. Immunity. 2013;39:758. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2013.08.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makedonas G, Betts MR. Living in a house of cards: re-evaluating CD8+ T-cell immune correlates against HIV. Immunol. Rev. 2010;239:109. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2010.00968.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olemukan RE, Eller LA, Ouma BJ, Etonu B, Erima S, Naluyima P, Kyabaggu D, Cox JH, Sandberg JK, Wabwire-Mangen F, Michael NL, Robb ML, de Souza MS, Eller MA. Quality monitoring of HIV-1-infected and uninfected peripheral blood mononuclear cell samples in a resource-limited setting. Clin. Vaccine Immunol. 2010;17:910. doi: 10.1128/CVI.00492-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ozaki DA, Gao H, Todd CA, Greene KM, Montefiori DC, Sarzotti-Kelsoe M. International technology transfer of a GCLP-compliant HIV-1 neutralizing antibody assay for human clinical trials. PLoS One. 2012;7:e30963. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0030963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perfetto SP, Ambrozak D, Nguyen R, Chattopadhyay P, Roederer M. Quality assurance for polychromatic flow cytometry. Nat. Protoc. 2006a;1:1522. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2006.250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perfetto SP, Chattopadhyay PK, Lamoreaux L, Nguyen R, Ambrozak D, Koup RA, Roederer M. Amine reactive dyes: an effective tool to discriminate live and dead cells in polychromatic flow cytometry. J. Immunol. Methods. 2006b;313:199. doi: 10.1016/j.jim.2006.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plotkin SA. Vaccines: correlates of vaccine-induced immunity. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2008;47:401. doi: 10.1086/589862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plotkin SA. Complex correlates of protection after vaccination. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2013;56:1458. doi: 10.1093/cid/cit048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pollara J, Hart L, Brewer F, Pickeral J, Packard BZ, Hoxie JA, Komoriya A, Ochsenbauer C, Kappes JC, Roederer M, Huang Y, Weinhold KJ, Tomaras GD, Haynes BF, Montefiori DC, Ferrari G. High-throughput quantitative analysis of HIV-1 and SIV-specific ADCC-mediating antibody responses. Cytometry A. 2011;79A:603. doi: 10.1002/cyto.a.21084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reimann KA, Chernoff M, Wilkening CL, Nickerson CE, Landay AL The ACTG immunology advanced technology laboratories. Preservation of Lymphocyte Immunophenotype and Proliferative Responses in Cryo-preserved Peripheral Blood Mononuclear Cells from Human Immunodeficiency Virus Type 1-Infected Donors: Implications for Multicenter Clinical Trials. Clin. Vaccine Immunol. 2000;7:352. doi: 10.1128/cdli.7.3.352-359.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell ND, Hudgens MG, Ha R, Havenar-Daughton C, McElrath MJ. Moving to human immunodeficiency virus type 1 vaccine efficacy trials: defining T cell responses as potential correlates of immunity. J. Infect. Dis. 2003;187:226. doi: 10.1086/367702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarzotti-Kelsoe M, Cox J, Cleland N, Denny T, Hural J, Needham L, Ozaki D, Rodriguez-Chavez IR, Stevens G, Stiles T, Tarragona-Fiol T, Simkins A. Evaluation and recommendations on good clinical laboratory practice guidelines for phase I-III clinical trials. PLoS Med. 2009;6:e1000067. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shields RL, Namenuk AK, Hong K, Meng YG, Rae J, Briggs J, Xie D, Lai J, Stadlen A, Li B, Fox JA, Presta LG. High resolution mapping of the binding site on human IgG1 for Fc gamma RI, Fc gamma RII, Fc gamma RIII, and FcRn and design of IgG1 variants with improved binding to the Fc gamma R. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:6591. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M009483200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker B, McMichael A. The T-cell response to HIV. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 2012;2:a007054. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a007054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walsh PN, Friedrich DP, Williams JA, Smith RJ, Stewart TL, Carter DK, Liao H-X, McElrath MJ, Frahm N NIAID HIV Vaccine Trials Network. Optimization and qualification of a memory B-cell ELISpot for the detection of vaccine-induced memory responses in HIV vaccine trials. J. Immunol. Methods. 2013;394:84. doi: 10.1016/j.jim.2013.05.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinberg A, Song L-Y, Wilkening C, Sevin A, Blais B, Louzao R, Stein D, Defechereux P, Durand D, Riedel E, Raftery N, Jesser R, Brown B, Keller MF, Dickover R, McFarland E, Fenton T. Pediatric ACTG Cryopreservation Working Group, 2009. Optimization and limitations of use of cryopreserved peripheral blood mononuclear cells for functional and phenotypic T-cell characterization. Clin. Vaccine Immunol. 2009;16:1176. doi: 10.1128/CVI.00342-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinberg A, Song LY, Wilkening CL, Fenton T, Hural J, Louzao R, Ferrari G, Etter PE, Berrong M, Canniff JD, Carter D, Defawe OD, Garcia A, Garrelts TL, Gelman R, Lambrecht LK, Pahwa S, Pilakka-Kanthikeel S, Shugarts DL, Tustin NB. Optimization of storage and shipment of cryopreserved peripheral blood mononuclear cells from HIV-infected and uninfected individuals for ELISPOT assays. J. Immunol. Methods. 2010;363:42. doi: 10.1016/j.jim.2010.09.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.