Abstract

Sigma (σ) factors are the predominant constituents of transcription regulation in bacteria. σ Factors recruit the core RNA polymerase to recognize promoters with specific DNA sequences. Recently, engineering of transcriptional regulators has become a significant tool for strain engineering. The present review summarizes the recent advances in σ factor based engineering or synthetic design. The manipulation of σ factors presents insights into the bacterial stress tolerance and metabolite productivity. We envision more synthetic design based on σ factors that can be used to tune the regulatory network of bacteria.

Keywords: sigma factor, strain engineering, bacterial stress tolerance, extremophile, synthetic biology

Introduction

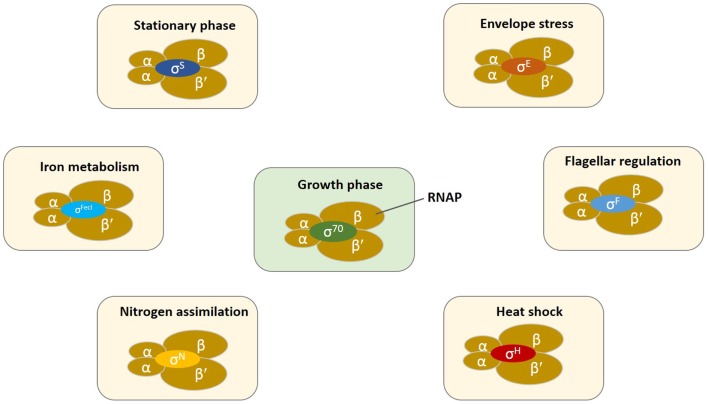

The transcriptional network of bacteria contains an extensive hierarchy of regulators with the RNA polymerase (RNAP) and particularly, σ factors toward the top and other transcription factors (TF) toward the bottom that control the regulatory network of gene transcription (Ishihama, 2010). Bacterial core RNAP consists of five subunits α2ββ′ω with a molecular mass of ~400 kDa. σ Factors are a family of TF that recruit RNAP for the transcription of a specific subset of genes/operons (Figure 1). The core RNAP associates with the initiation σ factor and the resulting holoenzyme recognizes promoters with specific DNA motifs.

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of the bacterial transcription initiation in which core RNAP (α2ββ′ω) associates with several different classes of sigma factors for the regulation of gene expression. Switching of σ factors occurs during the changing growth phases or environmental conditions. σ Factors in exponential growing cells, σ70/σD/σA; stationary or stress phase, σS/σ38/σB; heat shock, σH/σ32; extracytoplasmic function or extreme heat shock, σE/σ24; iron metabolism, σFecI; nitrogen regulation, σN/σ54; expression of flagellar genes, σF/σ28. The small subunit ω is omitted for clarity.

Engineering of transcriptional regulators can be utilized to modulate the bacterial transcriptional regulatory network (Lin et al., 2013b). These studies have been focused on artificial TF, such as zinc finger proteins (Park et al., 2005; Lee et al., 2011), as well as components of RNAP such as σ factors (mainly σ70) and the α subunit of RNAP (Alper and Stephanopoulos, 2007; Klein-Marcuschamer and Stephanopoulos, 2008; Klein-Marcuschamer et al., 2009; Ma and Yu, 2012). Recently, this approach has been further extended by introducing an engineered exogenous global regulator IrrE (Chen et al., 2011, 2012). The present review describes the recent highlights in the engineering or synthetic design of σ factors for artificial transcriptional regulation in several different types of bacteria.

An Overview of σ Factors

Bacteria encode an essential housekeeping σ factor that controls a large number of promoters, which is also known as σ70 (or σD) in Escherichia coli, σA in Bacillus subtilis, and other Gram-positive bacteria. While, one or more alternative σ factors control the transcriptional initiation of a subset of genes with shared functions that varies between species. For example, an intracellular pathogen Mycoplasma genitalium encodes 1 σ factor, E. coli encodes 7 σ factors, B. subtilis has 18 σ factors, Pseudomonas putida encodes 24 different σ factors, and the soil bacterium Streptomyces coelicolor contains 65 σ factors including 53 alternative σ factors (Gruber and Gross, 2003). All σ factors except σN (or σ54) belong to the σ70 family (Jordan et al., 2008). The σN family mainly regulates nitrogen metabolism (Murakami and Darst, 2003).

Bacteria often experience fluctuating changes in their environment from heat shock, variation in pH, and osmolarity to nutrient deprivation. They have adapted various mechanisms to respond to the imposed stresses (Aertsen and Michiels, 2004), and alternative σ factors provide the main line of response by effectively reprograming the transcription of sets of specific genes (Marles-Wright and Lewis, 2007). The key regulator of general stress response in E. coli is the σ factor σS (σ38 or RpoS) (McCann et al., 1991; Battesti et al., 2011), which either directly or indirectly regulates about 10% of E. coli genes during the stationary phase (Weber et al., 2005). The rpoS gene translation is activated by the RNA-chaperone Hfq mediated sRNAs, while it is inhibited by the sRNA, OxyS (Majdalani et al., 2002; Mandin and Gottesman, 2010). In the Gram-positive bacterium B. subtilis, the σ factor σB controls the general stress response (Hecker and Volker, 1998; Volker et al., 1999).

The E. coli heat shock response is positively controlled by σH (or σ32) encoded by the rpoH gene, which regulates the transcription of heat shock genes (Erickson and Gross, 1989; Wang and Kaguni, 1989; Nagai et al., 1990). σH mediated response protects the cells from heat as well as several other environmental stresses including acid shock, ethanol, and hyperosmotic shock (Gamer et al., 1996).

The cell surface stress is regulated by the ECF σ factors, which are in turn regulated by the corresponding anti-σ factors that are in most cases encoded within the same operons as σ factors (Missiakas et al., 1997; Ades et al., 1999). E. coli has two ECF σ factors, including σE (σ24) that regulates cell envelope response and σFecI (FecI) controlling the iron citrate transport system, respectively (Erickson and Gross, 1989; Angerer et al., 1995; Chaba et al., 2007). In P. aeruginosa, an ECF σ factor, AlgU (σ22) regulates the expression of the genes essential for synthesis of the exopolysaccharide alginate, which is responsible for biofilm formation and provides the bacterium better fitness against environmental stresses. AlgU is structurally similar to σE and recognizes similar promoter sequences (Cezairliyan and Sauer, 2009; Barchinger and Ades, 2013). B. subtilis encodes seven ECF σ factors (σM, σW, σX, σY, σZ, and σYlaC) (Wiegert et al., 2001; Ho and Ellermeier, 2012).

A class of σ factors that deserves special attention are those of the extremophilic microorganisms, which have developed changes in the cytoplasmic membrane structure, heat shock proteins, and synthesis of extremoenzymes to live under extreme environment such as extreme temperature, pH (acid or alkaline), high pressure, high salt concentration, toxic metals, and increased radiation (Cavicchioli et al., 2011; Reed et al., 2013). The extremophilic enzymes in these organisms have received ample attention due to their potential biotechnological applications, but the regulatory proteins including σ factors are much less well understood or known.

Thermus thermophilus HB27 and T. thermophilus HB8, both are extremely thermophilic bacteria, require an optimal growth temperature of 65°C. A housekeeping σ factor, σA was found in these thermophiles, which has a similar role to σ70 in E. coli (Nishiyama et al., 1999; Sakamoto et al., 2008). T. thermophilus HB8 has an operon consisting of sigE and TTHB212 genes encoding a σE and an anti-σE, respectively (Sakamoto et al., 2008).

A homolog of the E. coli stationary phase σ factor σS (about 76% similarity) is found in Vibrio parahaemolyticus, a Gram-negative bacterium inhabiting coastal waters. The rpoS deletion mutant strain had significantly reduced survival under acid stress conditions, suggesting its role in cell survival under stress conditions, such as oxidative stress and exposure to acid (Whitaker et al., 2010).

The extremely radioresistant Deinococcus radiodurans has acquired the ability to survive acute doses of γ-irradiation. Only three predicted σ factors were found in the genome of D. radiodurans, including one σ70 (rpoD/sigA), an ECF σ ortholog Sig1, and a third putative ECF σ ortholog Sig2. Sig 1 was found to play a major role in the regulation of heat shock genes for survival against heat and ethanol stresses, while Sig2 likely controls the expression of a smaller set of heat shock genes. Other alternative σ factors such as σS, σH, and σN were not found in D. radiodurans (Schmid and Lidstrom, 2002).

The bacterial σ factors have distinct promoter targets, yet these targets sometimes overlap. ECF σ factors generally recognize the highly conserved AAC motif in the −35 region and a CGT motif in the −10 region (Helmann, 2002). For example, the ECF σ factors of B. subtilis including σW, σX, and σM recognize an overlapping set of promoters related to cell envelope homeostasis and antibiotic resistance (Mascher et al., 2007; Kingston et al., 2013). Functional overlap between the promoters of σ70 with those of σS, σH, or σE was found in E. coli (Tanaka et al., 1993; Wade et al., 2006). The consensus binding DNA sites for the housekeeping and ECF σ factors of E. coli are very different, yet ~40% of overlap was observed for promoters recognized by σ70 and σE (Wade et al., 2006).

Engineering of σ Factors

Different σ factor based engineering approaches are described below and summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Various σ factor based engineering approaches applied for strain engineering.

| Sigma factor | Approach | Phenotype | Organism | Reference | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Housekeeping σ factor | σ70 | Global transcription engineering (gTME) | Ethanol, lactic acid, and acrylamide tolerance | E. coli L. plantarum R. ruber TH | Alper and Stephanopoulos (2007), Klein-Marcuschamer and Stephanopoulos (2008), and Ma and Yu (2012) |

| Hyaluronic acid production | E. coli | Yu et al. (2008) | |||

| σHrdB | Random mutation, genome shuffling, point mutation | Teicoplanin production | A. teichomyceticus L - 27 | Wang et al. (2014) | |

| Stationary phase σ factor | σS | Gene knockout | 1-Propanol and putrescine production | E. coli | Choi et al. (2012) and Qian et al. (2009) |

| Random mutagenesis | Isobutanol production | E. coli | Smith and Liao (2011) | ||

| Overexpression of sRNAs | Activation of σS and increased acid tolerance | E. coli | Gaida et al. (2013), Bak et al. (2014), and Jin et al., 2009 | ||

| Overexpression of 5′ untranslated region of rpoS mRNA | Polyhydroxybutyrate (PHB) production | E. coli | Kang et al. (2008) | ||

| SigE | Gene overexpression | Hydrogen and PHB production | Synechocystis sp. | Osanai et al. (2013a) and Osanai et al. (2013b) | |

| Alternative σ factors | Sig6 | Gene knockout | Avermectin production | S. avermitilis | Jiang et al. (2011) |

| σ22 | Mutation in anti-sigma factor | Alginate production | P. aeruginosa, P. fluorescens | Martin et al. (1993) and Borgos et al. (2013) | |

| Orf21 | Gene overexpression | Clavulanic acid production | S. clavuligerus NRRL3585 | Jnawali et al. (2011) | |

| σE | Adaptive evolution, gene overexpression | Ethanol production and tolerance | Thermoanaerobacter sp. X514 | Lin et al. (2013a,b) | |

| σN | Gene overexpression | Oxytetracycline production | E. coli | Stevens et al. (2013) | |

| σ Factors by synthetic design | σS | Synthetic sRNA, construction of riboswitch | Altered rpoS translation | E. coli | Jin et al. (2013) and Jin and Huang (2011) |

| ECF σ factors | Chimeric σ factors | E. coli | Rhodius et al. (2013) | ||

| Orthogonal σ factors | Bisected T7 polymerase | T7 phage | Segall-Shapiro and Voigt (2013) |

Engineering of housekeeping σ factors

Global transcription engineering (gTME) was applied to E. coli, Lactobacillus plantarum, and Rhodococcus ruber TH by tailoring the housekeeping σ factor to investigate ethanol tolerance, hyaluronic acid production, lactic and inorganic acid tolerance, and acrylamide tolerance, respectively. The best σ factor mutants showed enhanced stress tolerance than the wild-type strains (Alper and Stephanopoulos, 2007; Klein-Marcuschamer and Stephanopoulos, 2008; Yu et al., 2008; Ma and Yu, 2012).

The introduction of exogenous σ factor into an industrial strain Actinoplanes teichomyceticus L-27 was recently demonstrated. For this strain, the exact principal sigma factors σHrdB are not well understood, but the actinomyces genera shares high similarity in σHrdB amino acid sequences. Thus, three σHrdB genes from A. missouriensis 431, Micromonospora aurantiaca ATCC27029, and Salinispora arenicola CNS-205 were rationally selected and engineered by random mutagenesis, DNA shuffling, and point mutation, and the resulting library transferred in A. teichomyceticus L-27. Screening yielded a recombinant strain with a twofold increase in teicoplanin production in a pilot scale fermentation (5.3 mg L−1). The mutants showed significant diversity in the region 1.1 of σHrdB, apparently generated by DNA shuffling (Wösten, 1998; Campbell et al., 2002; Wang et al., 2014).

Engineering of stationary phase σ factors

While σs mainly plays a significant role in the metabolism of E. coli during the stationary phase, it was reported that during the exponential growth phase, deletion of σs gene (rpoS) enhanced the tricarboxylic acid cycle and the glyoxylate shunt (Rahman et al., 2006). The rpoS gene was knocked out from a metabolically engineered E. coli for 1-propanol production, and the yield increased by over 100% to about 10 g L−1 (Choi et al., 2012). Similarly, for an E. coli strain producing putrescine, a four carbon linear chain diamine with a wide range of industrial applications, the deletion of rpoS led to a 10% increase in the productivity in both batch and fed-batch cultures (Qian et al., 2009).

An engineered E. coli was constructed for improved isobutanol production by random mutagenesis and selection with an analog of valine (norvaline), which theoretically stimulated the production of the common precursor 2-ketoisovalerate. The mutant strain NV3 produced an improved isobutanol level of about 8 g L−1 in comparison to the wild-type strain with 5 g L−1 in 24 h. A truncation mutation was found in the rpoS gene of the mutant strain. Repair of this gene further elevated the yield of isobutanol to 21.2 g L−1 in 99 h (Smith and Liao, 2011), likely because in this case σS was critical for isobutanol tolerance.

The 5′ untranslated region of rpoS mRNA forms an inhibitory loop, which blocks the ribosome binding site and represses the translation of rpoS. Three non-coding sRNAs (DsrA, RprA, and ArcA) can disrupt this loop and overexpression of these sRNAs increased acid tolerance supra-additively up to 8500-fold during active cell growth (Gaida et al., 2013). On the other hand, deletion of any of these sRNA decreased acid resistance (Bak et al., 2014). The sRNA GcvB also positively regulates the rpoS expression level. This sRNA was identified from a single gene knock out library for 79 sRNA in E. coli MG1655. The overexpression of gcvB caused a threefold increase in the rpoS translation. Thus, GcvB can be a potential candidate for modulating rpoS expression and for engineering acid tolerance (Jin et al., 2009).

A stress-induced system was designed to activate polyhydroxybutyrate (PHB) production by placing the synthesis genes under the control of the 5′ untranslated region and the promoter of rpoS in E. coli, which formed a so-called stress-induced region (SIR). The engineered strain produced PHB up to 85.8% of cell dry weight in a glucose medium without the addition of any additional inducer (Kang et al., 2008). PHB with shorter carbon chains and polyhydroxyalkanoate (PHA) with longer carbon chains are two types of well known bioplastics.

The stationary phase σ factor, SigE in cyanobacteria is a positive regulator of sugar catabolism. For the unicellular cyanobacterium, Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803, overexpression of sigE enhanced the transcription of genes for the oxidative pentose phosphate pathway and also for glycogen catabolism, and altered the metabolite levels (e.g., acetyl coA and citrate) of the TCA cycle (Osanai et al., 2011). Further studies revealed more pleiotropic effects. The cell size of sigE over-expressing strain increased likely due to an aberrant cell division. The hydrogen production was also increased under microoxic conditions. However, sigE overexpression caused reduced photosynthesis and respiration due to changes in several regulatory proteins. Regardless of these changes, the engineered strain showed normal growth and viability both under nitrogen replete and nitrogen-limiting conditions (Osanai et al., 2013a). In addition, several cyanobacteria including Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803 accumulate mostly PHB as carbon and energy source during unfavorable growth conditions. Under nitrogen-limiting conditions, sigE overexpression in Synechocystis 6803 increased glucose catabolism, which turned the metabolic pathway toward increased PHB production (Osanai et al., 2013b).

Engineering of alternative σ factors

Avermectins that have potent anthelmintic and insecticidal properties are biosynthesized by Streptomyces avermitilis. About 47 ECF σ factors were found in the genome of S. avermitilis. The production of avermectin was negatively regulated by an ECF σ factor, Sig6 in S. avermitilis SAV663. Deletion of sig6 resulted in an increased avermectin yield of ~680 mg L−1, while overexpression decreased the yield by 56–63%. The expression of a pathway-specific activator gene aveR was upregulated in the sig6 deletion mutant, resulting in the increased avermectin production (Jiang et al., 2011).

Alginate is biosynthesized as an exopolysaccharide by two bacterial genera, Pseudomonas and Azotobacter. As mentioned, the expression of alginate biosynthetic genes is regulated by the alternative σ factor AlgU. A mutation in the anti-σ factor MucA resulted in stabilization of AlgU in P. aeruginosa, thereby overproduction of alginate (Martin et al., 1993). An efficient method for alginate production in P. fluorescens SBW25 was subsequently demonstrated (Borgos et al., 2013) using an engineered MucA mutant with a deletion of the 37 C-terminal amino acids. This mutant was found to upregulate various genes including the TCA cycle, ribosomal and translational proteins, and downregulated the NADPH oxidizing cycle, when cells were grown on glycerol in chemostats under nitrogen limitation.

The putative σ factor Orf21 was engineered to study its role in the production of clavulanic acid (CA) in Streptomyces clavuligerus NRRL3585. Disruption of the orf21 gene decreased the CA production slightly, whereas overexpression of orf21 enhanced the production by 1.4-fold. RT-PCR analysis showed that Orf21 activated the synthesis genes ceas2 and cas2, and the activator gene ccaR, of the CA gene cluster (Jnawali et al., 2011).

Solvent tolerance and productivity are two important traits required for biofuel production. An adaptive evolution strategy was developed for improved ethanol tolerance and productivity in Thermoanaerobacter sp. X514. Long-term exposure to ethanol caused the ethanol sensitive wild-type to develop a low ethanol tolerance of 2% (XI) and subsequently a higher tolerance of 6% (XII). Genomic and transcriptomic analyses identified an iron containing alcohol dehydrogenase (ADH) and the ECF σ24 as the key factors for improved tolerance for XI and XII, respectively. The adh over-expressing strain showed a 33% improvement in the ethanol productivity over the control, and a 31.8-fold enhanced growth under 1% ethanol. Under the same condition, ethanol tolerance was improved by 102-fold by over-expressing σ24, with a 21% higher ethanol productivity than the control (Lin et al., 2013a).

Overexpression of the alternative σ factor σ54 in E. coli successfully enhanced the heterologous expression of the oxytetracycline biosynthetic genes from a 32 kb type II oxytetracycline gene cluster. It was reasoned that this non-native cluster nonetheless contained σ54 promoters. This provides useful clues for the production of other polyketides (Stevens et al., 2013).

Synthetic design for σ factors

So far, the σ factors have been largely manipulated with the more traditional genetic engineering approach. However, in recent years, several lines of studies using the synthetic biology approach have emerged. For example, an artificial sRNA was obtained from a rationally designed library that bound to the RBS region of the rpoS gene. This RNA alone or together with the sRNA DsrA can act to inhibit the translation of rpoS and convert the activator DsrA to a co-inhibitor (Jin et al., 2013). A theophylline dependent hybrid riboswitch was also created using the lactose inducible promoter for controlling the σS expression. When theophylline was added, the rpoS expression was repressed with increased acid sensitivity and increased acetate assimilation. The addition of IPTG restored the σS activity with enhanced acid survival and normal acetate assimilation (Jin and Huang, 2011).

Genome mining was used to identify an orthogonal set of 20 bacterial ECF σ factors and their cognate promoters. These σ factors and their corresponding anti-σ factors were further used to build synthetic transcriptional units in E. coli. Additional chimeric σ factors were obtained by swapping the −35 and −10 promoter binding domains from subgroups of ECFs. This study demonstrates the possibility of designing synthetic regulatory network within a cell by utilizing ECF σ factors (Rhodius et al., 2013).

Finally, a bisected version of the T7 polymerase was used to create orthogonal sigma factors. This split polymerase contained a larger catalytic core and a smaller segment for promoter recognition. By engineering the latter, different orthogonal promoter recognition fragments were generated (Segall-Shapiro and Voigt, 2013).

Outlook

Although the knowledge of σ factors, including those of extremophiles, has been accumulating rapidly over the past two decades, the engineering of these factors remains scattered, and less than rational with few a priori designs. This is because the underlying mechanisms that bring the observed outcomes are often poorly understood. Nonetheless, the application of recent advances in systems biology will provide a more quantitative description of complex bacterial regulatory networks, which in turn will guide the engineering of σ factors to become a more predictable exercise. Additionally, an increasingly expanded set of new DNA manipulation tools as well as design principles from synthetic biology is now also available for this engineering endeavor. From this, one can envision the following lines of re-engineering or re-design of σ factors:

-

(1)

Re-design of the different domains of σ factors, including the helix-turn-helix (HTH)-mediated DNA binding motifs. This is in part demonstrated by the pioneering work of Rhodius et al. (2013). Design of artificial transcriptional factors based on the zinc finger motifs commonly found in eukaryotes has already been proved feasible (Park et al., 2003; Khalil et al., 2012).

-

(2)

Editing the promoter sequences for σ factors. Engineered promoters of different strength for both exponential and stationary phases have been available (Alper et al., 2005; Miksch et al., 2005), which provide clues or tools for manipulating promoters for σ factors.

-

(3)

Rewiring of the regulatory network for σ factors, which are part of the cellular transcriptional regulatory network that is interconnected, multi-layered, and hierarchical (Martinez-Antonio and Collado-Vides, 2003). It would be interesting to see whether one could partially or completely simplify/re-design regulatory switches or circuits for σ factors in order to better respond to industrially relevant stresses, many of which are more defined than the environmental ones.

-

(4)

Construction of sRNA molecules or sRNA circuits that regulate the translation of σ factors, as shown by Jin and Huang (2011). Na et al. (2013) have also previously demonstrated that it is possible to design artificial sRNAs that can regulate translation.

-

(5)

Finally, utilization of extremophilic σ factors in mesophilic organisms, which has not been explored so far. Along this line, it is interesting to note that the GroESL chaperonins from the solvent-tolerant P. putida enhanced thermo-tolerance and ethanol tolerance in E. coli, and the groESL from the thermophilic Thermoanaerobacter tengcongensis provided better tolerance toward corn cob hydrolyzates and better productivity for Clostridium acetobutylicum (Luan et al., 2014). This suggests that other extremophilic proteins including regulatory proteins may function in mesophilic organisms (Lin et al., 2013b).

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the National Basic Research Program of China (2011CBA00805 and 2013CB733900). Lakshmi Tripathi was supported by a Center for Life Science Post-Doctoral Fellowship, Tsinghua University.

References

- Ades S. E., Connolly L. E., Alba B. M., Gross C. A. (1999). The Escherichia coli sigma(E)-dependent extracytoplasmic stress response is controlled by the regulated proteolysis of an anti-sigma factor. Genes Dev. 13, 2449–2461 10.1101/gad.13.18.2449 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aertsen A., Michiels C. W. (2004). Stress and how bacteria cope with death and survival. Crit. Rev. Microbiol. 30, 263–273 10.1080/10408410490884757 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alper H., Fischer C., Nevoigt E., Stephanopoulos G. (2005). Tuning genetic control through promoter engineering. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 102, 12678–12683 10.1073/pnas.0504604102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alper H., Stephanopoulos G. (2007). Global transcription machinery engineering: a new approach for improving cellular phenotype. Metab. Eng. 9, 258–267 10.1016/j.ymben.2006.12.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angerer A., Enz S., Ochs M., Braun V. (1995). Transcriptional regulation of ferric citrate transport in Escherichia coli K-12. Fecl belongs to a new subfamily of sigma 70-type factors that respond to extracytoplasmic stimuli. Mol. Microbiol. 18, 163–174 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1995.mmi_18010163.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bak G., Han K., Kim D., Lee Y. (2014). Roles of rpoS-activating small RNAs in pathways leading to acid resistance of Escherichia coli. Microbiol. Open 3, 15–28 10.1002/mbo3.143 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barchinger S. E., Ades S. E. (2013). Regulated proteolysis: control of the Escherichia coli sigma(E)-dependent cell envelope stress response. Subcell. Biochem. 66, 129–160 10.1007/978-94-007-5940-4_6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Battesti A., Majdalani N., Gottesman S. (2011). The RpoS-mediated general stress response in Escherichia coli. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 65, 189–213 10.1146/annurev-micro-090110-102946 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borgos S., Bordel S., Sletta H., Ertesvåg H., Jakobsen Ø, Bruheim P., et al. (2013). Mapping global effects of the anti-sigma factor MucA in Pseudomonas fluorescens SBW25 through genome-scale metabolic modeling. BMC Syst. Biol. 7:19. 10.1186/1752-0509-7-19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell E. A., Muzzin O., Chlenov M., Sun J. L., Olson C. A., Weinman O., et al. (2002). Structure of the bacterial RNA polymerase promoter specificity sigma subunit. Mol. Cell 9, 527–539 10.1016/j.bbr.2011.03.031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavicchioli R., Amils R., Wagner D., Mcgenity T. (2011). Life and applications of extremophiles. Environ. Microbiol. 13, 1903–1907 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2011.02512.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cezairliyan B. O., Sauer R. T. (2009). Control of Pseudomonas aeruginosa AlgW protease cleavage of MucA by peptide signals and MucB. Mol. Microbiol. 72, 368–379 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2009.06654.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaba R., Grigorova I. L., Flynn J. M., Baker T. A., Gross C. A. (2007). Design principles of the proteolytic cascade governing the sigmaE-mediated envelope stress response in Escherichia coli: keys to graded, buffered, and rapid signal transduction. Genes Dev. 21, 124–136 10.1101/gad.1496707 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen T., Wang J., Yang R., Li J., Lin M., Lin Z. (2011). Laboratory-evolved mutants of an exogenous global regulator, IrrE from Deinococcus radiodurans, enhance stress tolerances of Escherichia coli. PLoS ONE 6:e16228. 10.1371/journal.pone.0016228 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen T., Wang J., Zeng L., Li R., Li J., Chen Y., et al. (2012). Significant rewiring of the transcriptome and proteome of an Escherichia coli strain harboring a tailored exogenous global regulator IrrE. PLoS ONE 7:e37126. 10.1371/journal.pone.0037126 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi Y. J., Park J. H., Kim T. Y., Lee S. Y. (2012). Metabolic engineering of Escherichia coli for the production of 1-propanol. Metab. Eng. 14, 477–486 10.1016/j.ymben.2012.07.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erickson J. W., Gross C. A. (1989). Identification of the sigma E subunit of Escherichia coli RNA polymerase: a second alternate sigma factor involved in high-temperature gene expression. Genes Dev. 3, 1462–1471 10.1101/gad.3.9.1462 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaida S. M., Al-Hinai M. A., Indurthi D. C., Nicolaou S. A., Papoutsakis E. T. (2013). Synthetic tolerance: three noncoding small RNAs, DsrA, ArcZ and RprA, acting supra-additively against acid stress. Nucleic Acids Res. 41, 8726–8737 10.1093/nar/gkt651 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gamer J., Multhaup G., Tomoyasu T., Mccarty J. S., Rudiger S., Schonfeld H. J., et al. (1996). A cycle of binding and release of the DnaK, DnaJ and GrpE chaperones regulates activity of the Escherichia coli heat shock transcription factor sigma32. EMBO J. 15, 607–617 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gruber T. M., Gross C. A. (2003). Multiple sigma subunits and the partitioning of bacterial transcription space. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 57, 441–466 10.1146/annurev.micro.57.030502.090913 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hecker M., Volker U. (1998). Non-specific, general and multiple stress resistance of growth-restricted Bacillus subtilis cells by the expression of the sigmaB regulon. Mol. Microbiol. 29, 1129–1136 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00977.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helmann J. D. (2002). “The extracytoplasmic function (ECF) sigma factors,” in Advances in Microbial Physiology, ed. Poole R. K. (San Diego, CA: Academic Press; ), 47–110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho T. D., Ellermeier C. D. (2012). Extra cytoplasmic function sigma factor activation. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 15, 182–188 10.1016/j.mib.2012.01.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishihama A. (2010). Prokaryotic genome regulation: multifactor promoters, multitarget regulators and hierarchic networks. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 34, 628–645 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2010.00227.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang L., Liu Y., Wang P., Wen Y., Song Y., Chen Z., et al. (2011). Inactivation of the extracytoplasmic function sigma factor Sig6 stimulates avermectin production in Streptomyces avermitilis. Biotechnol. Lett. 33, 1955–1961 10.1007/s10529-011-0673-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin Y., Huang J. D. (2011). Engineering a portable riboswitch-LacP hybrid device for two-way gene regulation. Nucleic Acids Res. 39, e131. 10.1093/nar/gkr609 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin Y., Watt R. M., Danchin A., Huang J. D. (2009). Small noncoding RNA GcvB is a novel regulator of acid resistance in Escherichia coli. BMC Genomics 10:165. 10.1186/1471-2164-10-165 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin Y., Wu J., Li Y., Cai Z., Huang J. D. (2013). Modification of the RpoS network with a synthetic small RNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 41, 8332–8340 10.1093/nar/gkt604 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jnawali H. N., Liou K., Sohng J. K. (2011). Role of sigma-factor (orf21) in clavulanic acid production in Streptomyces clavuligerus NRRL3585. Microbiol. Res. 166, 369–379 10.1016/j.micres.2010.07.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jordan S., Hutchings M. I., Mascher T. (2008). Cell envelope stress response in Gram-positive bacteria. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 32, 107–146 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2007.00091.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang Z., Wang Q., Zhang H., Qi Q. (2008). Construction of a stress-induced system in Escherichia coli for efficient polyhydroxyalkanoates production. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 79, 203–208 10.1007/s00253-008-1428-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khalil A. S., Lu T. K., Bashor C. J., Ramirez C. L., Pyenson N. C., Joung J. K., et al. (2012). A synthetic biology framework for programming eukaryotic transcription functions. Cell 150, 647–658 10.1016/j.cell.2012.05.045 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kingston A. W., Liao X., Helmann J. D. (2013). Contributions of the sigma, sigma and sigma regulons to the lantibiotic resistome of Bacillus subtilis. Mol. Microbiol. 90, 502–518 10.1111/mmi.12380 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein-Marcuschamer D., Santos C. N., Yu H., Stephanopoulos G. (2009). Mutagenesis of the bacterial RNA polymerase alpha subunit for improvement of complex phenotypes. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 75, 2705–2711 10.1128/AEM.01888-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein-Marcuschamer D., Stephanopoulos G. (2008). Assessing the potential of mutational strategies to elicit new phenotypes in industrial strains. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105, 2319–2324 10.1073/pnas.0712177105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee J. Y., Yang K. S., Jang S. A., Sung B. H., Kim S. C. (2011). Engineering butanol-tolerance in Escherichia coli with artificial transcription factor libraries. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 108, 742–749 10.1002/bit.22989 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin L., Ji Y., Tu Q., Huang R., Teng L., Zeng X., et al. (2013a). Microevolution from shock to adaptation revealed strategies improving ethanol tolerance and production in Thermoanaerobacter. Biotechnol. Biofuels 6, 103. 10.1186/1754-6834-6-103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin Z., Zhang Y., Wang J. (2013b). Engineering of transcriptional regulators enhances microbial stress tolerance. Biotechnol. Adv. 31, 986–991 10.1016/j.biotechadv.2013.02.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luan G., Dong H., Zhang T., Lin Z., Zhang Y., Li Y., et al. (2014). Engineering cellular robustness of microbes by introducing the GroESL chaperonins from extremophilic bacteria. J. Biotechnol. 178, 38–40 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2014.03.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma Y., Yu H. (2012). Engineering of Rhodococcus cell catalysts for tolerance improvement by sigma factor mutation and active plasmid partition. J. Ind. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 39, 1421–1430 10.1007/s10295-012-1146-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Majdalani N., Hernandez D., Gottesman S. (2002). Regulation and mode of action of the second small RNA activator of RpoS translation, RprA. Mol. Microbiol. 46, 813–826 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2002.03203.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandin P., Gottesman S. (2010). Integrating anaerobic/aerobic sensing and the general stress response through the ArcZ small RNA. EMBO J. 29, 3094–3107 10.1038/emboj.2010.179 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marles-Wright J., Lewis R. J. (2007). Stress responses of bacteria. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 17, 755–760 10.1016/j.sbi.2007.08.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin D. W., Schurr M. J., Mudd M. H., Govan J. R., Holloway B. W., Deretic V. (1993). Mechanism of conversion to mucoidy in Pseudomonas aeruginosa infecting cystic fibrosis patients. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 90, 8377–8381 10.1073/pnas.90.18.8377 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez-Antonio A., Collado-Vides J. (2003). Identifying global regulators in transcriptional regulatory networks in bacteria. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 6, 482–489 10.1016/j.mib.2003.09.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mascher T., Hachmann A. B., Helmann J. D. (2007). Regulatory overlap and functional redundancy among Bacillus subtilis extracytoplasmic function sigma factors. J. Bacteriol. 189, 6919–6927 10.1128/JB.00904-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCann M. P., Kidwell J. P., Matin A. (1991). The putative sigma factor KatF has a central role in development of starvation-mediated general resistance in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 173, 4188–4194 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miksch G., Bettenworth F., Friehs K., Flaschel E., Saalbach A., Twellmann T., et al. (2005). Libraries of synthetic stationary-phase and stress promoters as a tool for fine-tuning of expression of recombinant proteins in Escherichia coli. J. Biotechnol. 120, 25–37 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2005.04.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Missiakas D., Mayer M. P., Lemaire M., Georgopoulos C., Raina S. (1997). Modulation of the Escherichia coli sigmaE (RpoE) heat-shock transcription-factor activity by the RseA, RseB and RseC proteins. Mol. Microbiol. 24, 355–371 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.3601713.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murakami K. S., Darst S. A. (2003). Bacterial RNA polymerases: the whole story. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 13, 31–39 10.1016/S0959-440X(02)00005-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Na D., Yoo S. M., Chung H., Park H., Park J. H., Lee S. Y. (2013). Metabolic engineering of Escherichia coli using synthetic small regulatory RNAs. Nat. Biotechnol. 31, 170–174 10.1038/nbt.2461 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagai H., Yano R., Erickson J. W., Yura T. (1990). Transcriptional regulation of the heat shock regulatory gene rpoH in Escherichia coli: involvement of a novel catabolite-sensitive promoter. J. Bacteriol. 172, 2710–2715 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishiyama M., Kobashi N., Tanaka K., Takahashi H., Tanokura M. (1999). Cloning and characterization in Escherichia coli of the gene encoding the principal sigma factor of an extreme thermophile, Thermus thermophilus. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 172, 179–186 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1999.tb13467.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osanai T., Kuwahara A., Iijima H., Toyooka K., Sato M., Tanaka K., et al. (2013a). Pleiotropic effect of sigE over-expression on cell morphology, photosynthesis and hydrogen production in Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803. Plant J. 76, 456–465 10.1111/tpj.12310 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osanai T., Numata K., Oikawa A., Kuwahara A., Iijima H., Doi Y., et al. (2013b). Increased bioplastic production with an RNA polymerase sigma factor SigE during nitrogen starvation in Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803. DNA Res. 20, 525–535 10.1093/dnares/dst028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osanai T., Oikawa A., Azuma M., Tanaka K., Saito K., Hirai M. Y., et al. (2011). Genetic engineering of group 2 sigma factor SigE widely activates expressions of sugar catabolic genes in Synechocystis species PCC 6803. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 30962–30971 10.1074/jbc.M111.231183 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park K. S., Jang Y. S., Lee H., Kim J. S. (2005). Phenotypic alteration and target gene identification using combinatorial libraries of zinc finger proteins in prokaryotic cells. J. Bacteriol. 187, 5496–5499 10.1128/JB.187.15.5496-5499.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park K. S., Lee D. K., Lee H., Lee Y., Jang Y. S., Kim Y. H., et al. (2003). Phenotypic alteration of eukaryotic cells using randomized libraries of artificial transcription factors. Nat. Biotechnol. 21, 1208–1214 10.1038/nbt868 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qian Z. G., Xia X. X., Lee S. Y. (2009). Metabolic engineering of Escherichia coli for the production of putrescine: a four carbon diamine. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 104, 651–662 10.1002/bit.22502 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rahman M., Hasan M. R., Oba T., Shimizu K. (2006). Effect of rpoS gene knockout on the metabolism of Escherichia coli during exponential growth phase and early stationary phase based on gene expressions, enzyme activities and intracellular metabolite concentrations. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 94, 585–595 10.1002/bit.20858 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reed C. J., Lewis H., Trejo E., Winston V., Evilia C. (2013). Protein adaptations in archaeal extremophiles. Archaea 2013, 373275. 10.1155/2013/373275 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhodius V. A., Segall-Shapiro T. H., Sharon B. D., Ghodasara A., Orlova E., Tabakh H., et al. (2013). Design of orthogonal genetic switches based on a crosstalk map of sigmas, anti-sigmas, and promoters. Mol. Syst. Biol. 9, 702. 10.1038/msb.2013.58 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakamoto K., Agari Y., Yokoyama S., Kuramitsu S., Shinkai A. (2008). Functional identification of an anti-sigmaE factor from Thermus thermophilus HB8. Gene 423, 153–159 10.1016/j.gene.2008.07.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmid A. K., Lidstrom M. E. (2002). Involvement of two putative alternative sigma factors in stress response of the radioresistant bacterium Deinococcus radiodurans. J. Bacteriol. 184, 6182–6189 10.1128/JB.184.22.6182-6189.2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segall-Shapiro T. H., Voigt C. (2013). Artificial sigma factors based on bisected t7 RNA polymerase. United States patent application PCT/US2013/034147.

- Smith K. M., Liao J. C. (2011). An evolutionary strategy for isobutanol production strain development in Escherichia coli. Metab. Eng. 13, 674–681 10.1016/j.ymben.2011.08.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevens D. C., Conway K. R., Pearce N., Villegas-Penaranda L. R., Garza A. G., Boddy C. N. (2013). Alternative sigma factor over-expression enables heterologous expression of a type II polyketide biosynthetic pathway in Escherichia coli. PLoS ONE 8:e64858. 10.1371/journal.pone.0064858 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka K., Takayanagi Y., Fujita N., Ishihama A., Takahashi H. (1993). Heterogeneity of the principal sigma factor in Escherichia coli: the rpoS gene product, sigma 38, is a second principal sigma factor of RNA polymerase in stationary-phase Escherichia coli. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 90, 3511–3515 10.1073/pnas.90.8.3511 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volker U., Maul B., Hecker M. (1999). Expression of the sigmaB-dependent general stress regulon confers multiple stress resistance in Bacillus subtilis. J. Bacteriol. 181, 3942–3948 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wade J. T., Castro Roa D., Grainger D. C., Hurd D., Busby S. J., Struhl K., et al. (2006). Extensive functional overlap between sigma factors in Escherichia coli. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 13, 806–814 10.1038/nsmb1130 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H., Yang L., Wu K., Li G. (2014). Rational selection and engineering of exogenous principal sigma factor (sigma(HrdB)) to increase teicoplanin production in an industrial strain of Actinoplanes teichomyceticus. Microb. Cell Fact. 13, 10. 10.1186/1475-2859-13-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Q. P., Kaguni J. M. (1989). dnaA protein regulates transcriptions of the rpoH gene of Escherichia coli. J. Biol. Chem. 264, 7338–7344 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weber H., Polen T., Heuveling J., Wendisch V. F., Hengge R. (2005). Genome-wide analysis of the general stress response network in Escherichia coli: sigmaS-dependent genes, promoters, and sigma factor selectivity. J. Bacteriol. 187, 1591–1603 10.1128/JB.187.5.1591-1603.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitaker W. B., Parent M. A., Naughton L. M., Richards G. P., Blumerman S. L., Boyd E. F. (2010). Modulation of responses of Vibrio parahaemolyticus O3:K6 to pH and temperature stresses by growth at different salt concentrations. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 76, 4720–4729 10.1128/AEM.00474-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiegert T., Homuth G., Versteeg S., Schumann W. (2001). Alkaline shock induces the Bacillus subtilis sigma(W) regulon. Mol. Microbiol. 41, 59–71 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2001.02489.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wösten M. M. S. M. (1998). Eubacterial sigma-factors. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 22, 127–150 10.1111/j.1574-6976.1998.tb00364.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu H., Tyo K., Alper H., Klein-Marcuschamer D., Stephanopoulos G. (2008). A high-throughput screen for hyaluronic acid accumulation in recombinant Escherichia coli transformed by libraries of engineered sigma factors. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 101, 788–796 10.1002/bit.21947 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]