Abstract

Coeliac disease (CD) affects about 1 % of the general population. Information concerning gluten intake in the general population is scarce. In particular, variation in gluten intake during the complementary feeding period may be an independent risk factor in CD pathogenesis. We determined the intake of gluten from wheat, barley, rye and oats in a cross-sectional National Danish Survey of Dietary Habits among Infants and Young Children (2006–2007). The study population comprised a random sample of 1743 children aged 6–36 months, recruited from the National Danish Civil Registry. The protein contents from wheat, rye, barley and oats were found in the National Danish Food Composition Table, and multiplied with the amounts in the recipes. The amounts of gluten were calculated as the amount of cereal protein × 0·80 for wheat and oats, ×0·65 for rye and ×0·50 for barley. Dietary intake was recorded daily for seven consecutive days in pre-coded food records supplemented with open-answer possibilities. Gluten intake increased with age (P < 0·0001). Oats were introduced first, rapidly outpaced by wheat, the intake of which continued to increase with age, whereas oats started to decrease at 12 months. Boys had a higher intake of energy (P ≤ 0·0001) and all types of gluten, except for barley (P ≤ 0·87). In 8–10-month-old (P < 0·0001) and 10–12-month-old (P = 0·007), but not in 6–8-month-old infants (P = 0·331), non-breast-fed infants had higher total gluten intake than partially breast-fed infants. In conclusion, this study presents representative population-based data on gluten intake in Danish infants and young children.

Key words: Gluten, Coeliac disease, Diet, Children, Infants, Breast-feeding

Abbreviation: CD, coeliac disease

Coeliac disease (CD) is characterised as a state of heightened immunological responsiveness to ingested gluten (from wheat, barley or rye) in genetically susceptible individuals( 1 ). CD at the same time is a multi-organ disease with a wide variety of gastrointestinal and extra-intestinal manifestations of variable type and severity that may become symptomatic at all ages( 2 ). If the disease is untreated, it is associated with a number of complications, e.g. chronic diarrhoea, anaemia and growth problems in infancy and childhood as well as osteoporosis later in life( 1 , 3 ).

Historically, CD has been considered as an uncommon condition, but recent studies in a number of populations have shown that CD affects about 1 % of the general population( 4 – 8 ) and that the prevalence may be increasing( 9 ).

Information concerning gluten intake in the general population is scarce. In particular, variation in gluten intake during the complementary feeding period may be an independent risk factor in CD pathogenesis( 10 ).

We therefore determined the intake of gluten from wheat, oats, barley and rye in a cross-sectional National Danish Survey of Dietary Habits among Infants and Young Children.

Subjects and methods

The study was conducted according to the guidelines laid down in the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Danish Data Protection Agency. According to the Danish National Committee on Health Research Ethics, studies with no intervention and with no invasive treatment, like the present study, in which only diet was recorded, do not require ethical approval. Verbal informed consent was obtained from custody holders of all subjects, and was witnessed and recorded.

Population

A total of 1757 children, aged 6–36 months, were recruited by simple random samples from The Central Office of Civil Registration. Within respective age groups the sample was representative with regard to age and sex and covered all months of the year and the whole country geographically. The recruited children were enrolled in The National Danish Dietary Survey among Infants and Young Children (2006–2007) – a cross-sectional study of infants and young children, aimed at assessing food and nutrient intakes, including gluten, related to age and dietary recommendations( 11 ). The response rate for infants and children with both background interview and dietary data was 54 %. The distribution of sex and age of the participants could be characterised as representative of the Danish population of children aged 6–36 months as compared with the data of the general population in Denmark( 12 ), except for the 12–24-month-old children, where boys were underrepresented (47 % in the sample v. 51 % the whole population).

Anthropometric variables

Information about length (≤12 months) or height (>12 months) was obtained through a personal face-to-face interview with one parent. At the interview nude weight to the nearest 0·1 kg was obtained by the interviewer, using a digital scale (Soehnle Verona 63686 (Medshop) Quattrotronic scale). Alternatively, the weight was collected from the child's health cards, previously measured by healthcare personnel.

Dietary intake

Dietary consumption was recorded for seven consecutive days using a validated method( 13 ) consisting of pre-coded booklets accompanied by a booklet with twelve food photograph series( 14 ). The pre-coded food record was developed specifically for children between 6 months and 4 years of age and the booklets were divided into different parts corresponding to breakfast, lunch, dinner and in-between meals. The quantities were estimated from standard portion sizes, household measures or from the food photograph series, depending on the specific food or drink. If the child attended day care the food and drinks were recorded in household measures by the day care staff on a sheet, and then transferred to the pre-coded food record by the parents.

Gluten content in food items

Cereal-containing products included porridge, which was divided into industrial porridge, where brand names were provided, and homemade porridge, in categories of millet, oats and wheat porridge and open space to record other types of porridge. Mashes can be divided into industrial mashes, where brand names were provided, and homemade mashes, with information on the amount of pasta. Bread can be divided into cereal types of bread, such as wheat bread and rye bread. Recipes were generic recipes made as a weighted average from the most used bread types. Pasta consisted of one generic recipe with wheat pasta. Breakfast cereals can be divided into sugary breakfast cereals and non-sugary breakfast cereals. Recipes for each group were generic recipes made from the most widely used breakfast cereals. Muesli and rolled oats were provided each with separate recipes.

All food products containing wheat, oats, barley and rye were considered as containing gluten. From all food products reported in the food record, the gluten content of these cereals was calculated. Since there is no information in food composition tables on the gluten content of food products, the estimated amount of protein from gluten-containing cereals according to the Danish Food Composition Databank( 15 ) was multiplied by 0·8 for wheat( 16 , 17 ) and oats, by 0·65 for rye( 18 ) and by 0·50 for barley( 19 ). The amount of gluten-containing cereals in composite foods was estimated from recipe information from producers or the recipes used in the dietary survey.

Intakes of energy, nutrients and food items were calculated for each individual using the software system GIES (version 1.000 d; developed at the National Food Institute, Technical University of Denmark) and the Danish Food Composition Databank( 15 ).

Outliers

Participants were considered outliers and excluded from the analyses (n 14) if their energy intake per kg body weight was +3 sd of the mean, resulting in a final number of participants of n 1743. Estimation of the degree of possible over- and under-reporting was done by comparing the daily energy intake of each participant with their likely energy requirement. For the infants (<12 months) this was done using the reference values of the estimated daily energy requirement of 355 kJ/kg for children below 12 months according to Nordic Nutrition Recommendations( 20 ) and cut-offs (±46 %) as reported by Wells & Davies( 21 ). For the children the BMR was estimated for each individual according to the Nordic Nutrition Recommendations( 20 ) and used for estimating cut-off points based on physical activity level values of light activity level (1·44) and according to Goldberg et al.( 22 ), Black et al.( 23 , 24 ) and Livingstone et al.( 25 ).

Breast-feeding

To estimate the quantity of breast milk consumed, information on the frequency of feeding was used combined with data on the presumed volume of breast milk per feed( 26 ). If the child received breast milk more than six times per d, the assigned volume was 130 ml per feed; with three–five feeds per d, the assigned volume was 89 ml per feed; and with less than three feeds per d, the volume assigned was 53 ml per feed. The nutritional content of breast milk was calculated according to published values( 27 , 28 ).

Statistical analysis

All data were analysed with SPSS software (version 20.0; IBM SPSS Inc.). Results are given as mean values and standard deviations. ANOVA was applied to test for statistically significant differences in gluten intakes between sex (male; female), age groups (6–7, 8–9, 10–11, 12–24 and 24–36 months) and the general linear models procedure was applied with age as a covariate included in the models to test statistically significant differences in gluten intakes between breast-feeding groups (partially breast-fed and non-breast-fed). A significance level of P < 0·05 was used (two-tailed tests).

Results

Descriptive characteristics

Characteristics of the study population are given in Table 1. Boys were taller and heavier than girls, and boys had higher birth weight (P < 0·001), birth length (P < 0·001) and ponderal index at birth (P = 0·063) than girls.

Table 1.

Physiological characteristics of the study population (n 1743)

(Mean values and standard deviations)

| 6–7 months (n 316) | 8–9 months (n 289) | 10–11 months (n 221) | 12–24 months (n 474) | 25–36 months (n 443) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | sd | Mean | sd | Mean | sd | Mean | sd | Mean | sd | ||

| Age (months) | Boys | 6·8 | 0·6 | 8·9 | 0·6 | 10·8 | 0·5 | 17·9 | 3·5 | 30·0 | 3·8 |

| Girls | 6·8 | 0·7 | 8·9 | 0·6 | 10·9 | 0·5 | 17·5 | 3·4 | 30·3 | 3·5 | |

| P* | 0·543 | 0·740 | 0·027 | 0·235 | 0·392 | ||||||

| Length or height (cm) | Boys | 69·67 | 3·30 | 72·59 | 3·77 | 73·31 | 3·45 | 78·26 | 4·75 | 87·67 | 7·01 |

| Girls | 67·43 | 3·12 | 70·61 | 3·71 | 71·53 | 4·17 | 76·24 | 4·76 | 84·93 | 7·77 | |

| P* | <0·001 | <0·001 | 0·001 | <0·001 | <0·001 | ||||||

| Weight (kg) | Boys | 8·92 | 1·07 | 9·64 | 1·04 | 10·20 | 1·16 | 11·75 | 1·47 | 13·86 | 1·66 |

| Girls | 8·07 | 0·98 | 8·80 | 1·02 | 9·41 | 1·01 | 10·98 | 1·39 | 13·77 | 1·86 | |

| P* | <0·001 | <0·001 | <0·001 | <0·001 | 0·599 | ||||||

| BMI (kg/m2) | Boys | 18·38 | 2·04 | 18·36 | 2·23 | 19·04 | 2·38 | 19·22 | 2·60 | 18·22 | 3·17 |

| Girls | 17·78 | 2·15 | 17·73 | 2·41 | 18·45 | 2·55 | 18·86 | 2·56 | 19·57 | 4·17 | |

| P* | 0·012 | 0·023 | 0·083 | 0·146 | <0·001 | ||||||

* ANOVA test for the difference between boys and girls within the same age group.

Diet and gluten intake

In agreement with the fact that the boys were larger than the girls, boys had a higher intake of energy than girls below the age of 12 months (P < 0·001), but not above the age of 12 months when adjusted for age (results not shown). However, there was no sex difference regarding energy intake per kg of body weight (P = 0·191).

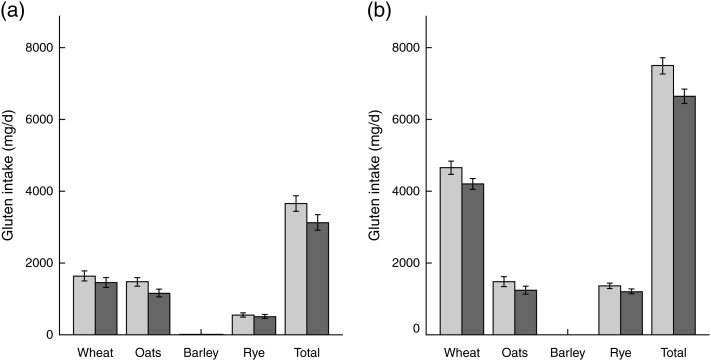

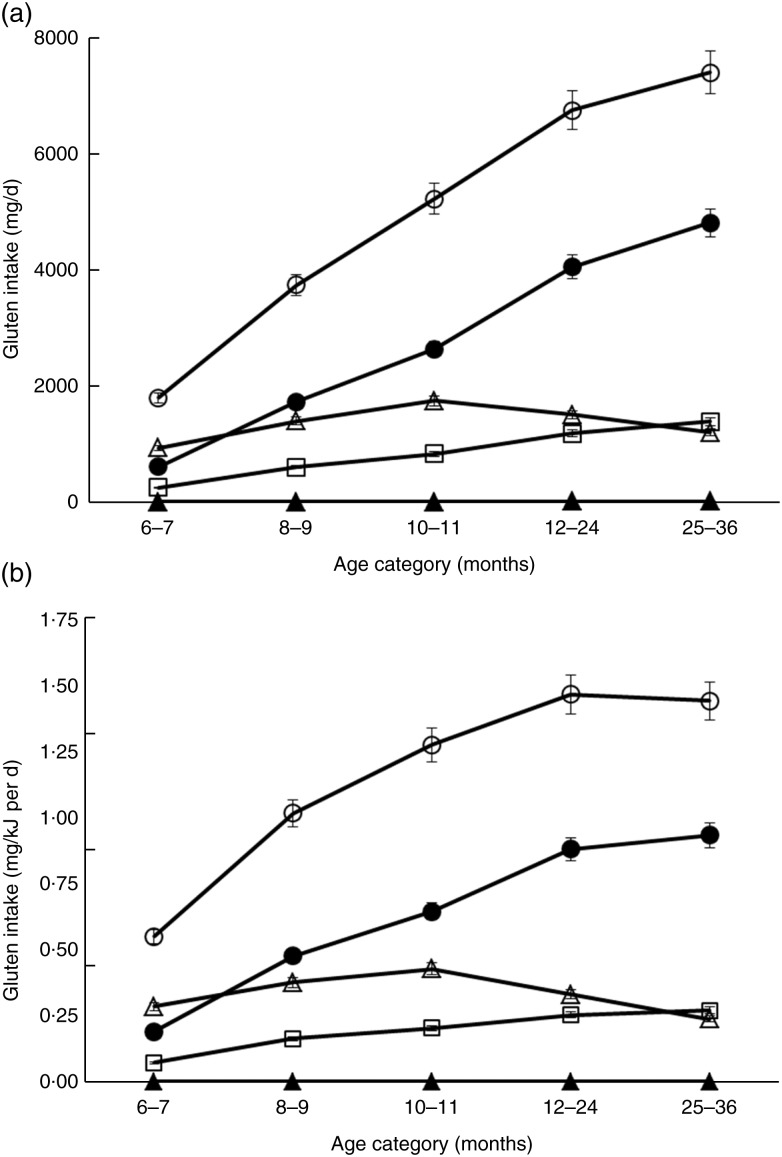

Total gluten intake (mg) was higher in boys than in girls, and the intake of different gluten types tended to be higher in boys than in girls with the exception of gluten from barley (Fig. 1). Gluten intake (mg/d) increased with increasing age (all types; P < 0·0001) (Table 2). Oats were introduced first, rapidly being outpaced by wheat that continued to increase with age, whereas oats started to decrease at 12 months (Fig. 2).

Fig. 1.

Daily intake of gluten (mg/d) from wheat, oats, barley and rye, and total gluten in

6- to 36-month-old Danish infants and children (n 1743). Values are

means, with 95 % CI represented by vertical bars. ( ),

Boys; (

),

Boys; ( ), girls. (a) Infants aged 6 to 12 months

old (n 826). Differences between boys and girls: wheat,

P = 0·06; oats, P < 0·001; barley,

P = 0·49; rye, P = 0·33; total,

P = 0·001. (b) Children aged 12 to 36 months old

(n 917). Differences between boys and girls: wheat,

P < 0·001; oats, P = 0·007; barley,

P = 0·87; rye, P = 0·002; total,

P < 0·001.

), girls. (a) Infants aged 6 to 12 months

old (n 826). Differences between boys and girls: wheat,

P = 0·06; oats, P < 0·001; barley,

P = 0·49; rye, P = 0·33; total,

P = 0·001. (b) Children aged 12 to 36 months old

(n 917). Differences between boys and girls: wheat,

P < 0·001; oats, P = 0·007; barley,

P = 0·87; rye, P = 0·002; total,

P < 0·001.

Table 2.

Daily gluten intake in 6–36-month-old infants and children (n 1743)

(Mean values and standard deviations)

| 6–7 months (n 316) | 8–9 months (n 289) | 10–11 months (n 221) | 12–24 months (n 474) | 25–36 months (n 443) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | sd | Mean | sd | Mean | sd | Mean | sd | Mean | sd | |

| Gluten (mg/d) | 1796a | 1508 | 3740b | 1860 | 5224c | 2089 | 6748d | 2393 | 7400e | 2323 |

| Wheat | 610a | 685 | 1734b | 1213 | 2639c | 1504 | 4054d | 1788 | 4809e | 1869 |

| Oats | 935a | 999 | 1400b,d,e | 1155 | 1750c,d | 1267 | 1504b,c,d | 1352 | 1197b,e | 1281 |

| Barley | 4·94a | 4·25 | 3·86a | 13·3 | 2·35a | 5·96 | 8·17b | 24·2 | 8·28b | 24·9 |

| Rye | 249a | 418 | 602b | 566 | 833c | 622 | 1181d | 756 | 1386e | 780 |

| Gluten per unit energy intake (mg/kJ per d) | 0·55a | 0·41 | 1·02b | 0·45 | 1·28c | 0·42 | 1·47d | 0·40 | 1·44d | 0·37 |

| Wheat | 0·19a | 0·20 | 0·48b | 0·33 | 0·64c | 0·32 | 0·88d | 0·34 | 0·93d | 0·31 |

| Oats | 0·28a,d,e | 0·29 | 0·37b,c,d | 0·29 | 0·43b,c | 0·29 | 0·33a,b,d | 0·28 | 0·24a,e | 0·26 |

| Barley | 0·0009a,b,c,e | 0·001 | 0·0010a,b,c,d,e | 0·003 | 0·0006a,b,c | 0·001 | 0·0018b,d,e | 0·005 | 0·0016a,b,d,e | 0·005 |

| Rye | 0·07a | 0·12 | 0·16b | 0·15 | 0·20c | 0·16 | 0·25d | 0·15 | 0·27d | 0·14 |

a,b,c,d,e Mean values within a row with unlike superscript letters were significantly different (P < 0·05; ANOVA test with Bonferroni post hoc test).

Fig. 2.

Daily intake of gluten from wheat, oats, barley and rye, and total gluten in 6- to 36-month-old Danish infants and children (n 1743). Values are means, with 95 % CI represented by vertical bars. ○, Total gluten; •, wheat; ▵, oats; ▴, barley; □, rye. (a) Absolute gluten intake (mg/d). (b) Gluten intake per unit energy intake (mg/kJ per d).

Breast-feeding

All infants at the age of 6 months had ceased exclusive breast-feeding. In 6–8-month-olds, 57 % of the infants were still being partially breast-fed, in 8–10-month-olds, 38 % of the infants and in 10–12-month-olds, 22 % of the infants were still being partially breast-fed. In 12–24-month-olds, 5 % of the children were still being partially breast-fed, and in 24–36-month-olds, 1 % of the children were still being partially breast-fed (Table 3). Although intake of all types of gluten were higher in non-breast-fed infants than in partially breast-fed infants, there were no statistically significant differences in gluten intake, in absolute amounts and energy adjusted amounts, between partially breast-fed and non-breast-fed 6–8-month-old infants. In 8–10-month-old and in 10–12-month-old infants, non-breast-fed infants had higher absolute total gluten intake than partially breast-fed infants.

Table 3.

Daily intake of gluten in partially breast-fed (P-BF) and non-breast-fed (N-BF) 6–12-month-old children (n 826)

(Mean values and standard deviations)

| 6–8 months (n 316) | 8–10 months (n 289) | 10–12 months (n 221) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P-BF (n 181) | N-BF (n 135) | P-BF (n 110) | N-BF (n 179) | P-BF (n 48) | N-BF (n 173) | ||||||||||

| Mean | sd | Mean | sd | P* | Mean | sd | Mean | sd | P* | Mean | sd | Mean | sd | P* | |

| Gluten (mg/d) | 1649 | 1537 | 1994 | 1450 | 0·331 | 3185 | 1580 | 4080 | 1940 | <0·001 | 4392 | 1777 | 5455 | 2115 | 0·007 |

| Wheat | 542 | 677 | 700 | 687 | 0·229 | 1411 | 1025 | 1932 | 1278 | <0·001 | 2338 | 1493 | 2723 | 1500 | 0·256 |

| Oats | 870 | 974 | 1022 | 1030 | 0·562 | 1182 | 1018 | 1534 | 1215 | 0·012 | 1313 | 1166 | 1872 | 1270 | 0·012 |

| Barley | 2·77 | 4·33 | 3·17 | 4·15 | 0·537 | 2·18 | 3·06 | 4·89 | 16·70 | 0·094 | 1·85 | 4·08 | 2·49 | 6·40 | 0·649 |

| Rye | 234 | 411 | 269 | 430 | 0·947 | 591 | 566 | 609 | 568 | 0·805 | 740 | 661 | 859 | 662 | 0·343 |

| Gluten per unit energy intake (mg/kJ per d) | 0·53 | 0·43 | 0·59 | 0·38 | 0·847 | 0·92 | 0·41 | 1·07 | 0·45 | 0·003 | 1·17 | 0·36 | 1·30 | 0·43 | 0·151 |

| Wheat | 0·18 | 0·20 | 0·21 | 0·18 | 0·739 | 0·41 | 0·29 | 0·52 | 0·35 | 0·007 | 0·62 | 0·34 | 0·65 | 0·32 | 0·919 |

| Oats | 0·28 | 0·29 | 0·30 | 0·29 | 0·814 | 0·34 | 0·29 | 0·40 | 0·29 | 0·109 | 0·35 | 0·30 | 0·45 | 0·28 | 0·065 |

| Barley | 0·0009 | 0·001 | 0·0010 | 0·001 | 0·826 | 0·0006 | 0·0009 | 0·0012 | 0·004 | 0·092 | 0·0005 | 0·001 | 0·0006 | 0·001 | 0·832 |

| Rye | 0·07 | 0·12 | 0·08 | 0·11 | 0·557 | 0·17 | 0·17 | 0·16 | 0·14 | 0·478 | 0·20 | 0·17 | 0·21 | 0·16 | 0·884 |

* Univariate general linear model test for the difference between breast-feeding groups with age as a covariate.

Possible over- and under-reporting

In total, about 9 % of the children were possible over-reporters and about 2 % were possible under-reporters.

Discussion

In the present study, we examined gluten consumption patterns in a representative sample of healthy Danish infants and young children. We observed that gluten consumption increased with age. Oats were being introduced first, being outpaced at 8–9 months of age by wheat that continued to increase with age, whereas oats started to decrease at 12 months of age. This pattern is in agreement with the Danish national dietary recommendation for infants( 29 ) to start complementary feeding with porridge that typically contains oats from the age of about 6 months, and then later introduce bread and pasta made from wheat, the type of gluten that was consumed in the highest amount in Danish infants and young children, except for oats in 6–7-month-olds. In general, the consumption of barley in Danish infants and young children was very low and with quite a large variation. The intake of rye exceeded that of oats at 25–36 months of age, which probably is due to the frequent use of rye bread in the Danish diet( 30 ).

The present study found that boys had higher gluten intakes than girls, but this difference disappeared when expressed as mg gluten per kJ energy or mg gluten per kg body weight. This finding may indicate that there were no differences in the eating pattern with regard to gluten-containing foods between boys and girls.

To our knowledge, no other studies have examined the relationship between gluten intake and age and breast-feeding status. However, in Sweden, national data on the duration of breast-feeding were collected on a yearly basis from 1973 to 1997, and the supply of gluten-containing follow-on formula sold on the Swedish market was used to estimate average daily consumption of flour in children below 2 years of age( 31 ). Also, in a Swedish population-based case-referent study, a questionnaire was used to assess patterns of food introduction to infants, showing that the risk of CD was reduced in children aged <2 years if they were still being breast-fed when dietary gluten was introduced( 32 ). More recently, an FFQ was developed in The Netherlands which assessed the gluten intake in eighty-seven infants( 33 ) and seventy-one young children( 34 ).

The prevalence of diagnosed CD differs considerably among bordering countries( 35 – 37 ). Previously, CD was considered as an uncommon condition, and earlier studies have shown a strikingly low prevalence of CD in Denmark( 38 ). However, the true prevalence may be substantially higher than that reported in clinical studies due to an unidentified number of undiagnosed children( 39 ) and adults, and the prevalence seems to be increasing( 9 ), emphasising the importance of accumulating knowledge about quantitative and qualitative gluten intake in infants and children. The diet in the first year of life, including the timing of introduction of complementary feeding, may have a substantial influence on CD development as suggested by studies of autoimmunity in the first year of life( 40 , 41 ), indicating a ‘sensitive window’ for the development of CD.

As the timing of introduction of gluten into the food package of young children also seems to play a role in the development of auto-immunity next to the use of breast-feeing( 42 ), we explored the relationship between breast-feeding and intake of gluten in infants and young children. After adjusting for the influence of age, gluten intake was generally higher in non-breast-fed infants than in partially breast-fed infants, although less pronounced in the younger age group. It may be concluded that the national guidelines for infant feeding with regard to introducing gluten-containing foods while still breast-feeding were seemingly followed to a large extent in this Danish population, and this might contribute to the explanation that the incidence of CD is relatively low in Denmark.

There were some limitations in the present study. Breast milk intake was assessed from frequency of feeding, which may be a rather rough estimate, not considering the variation in milk composition during a feed or the duration of feeding, but comparable with those used in other studies( 43 , 44 ). Still, a small over- or underestimation of the breast milk intake may be present. A second limitation in the present study is the presence of possible over- and under-reporters. We estimated that approximately 9 % of the children were possible over-reporters and about 2 % were possible under-reporters. In comparison, Conn et al. using the same principle found, among 9-month-olds, that 32 % were likely to be over-reporting and <1 % under-reporting( 43 ). We chose not to exclude these possible over- and under-reporters as intakes in this age group may vary considerably and most of the infants and young children classified as possible over-reporters were just above the calculated limits.

The strengths of the present study include access to very detailed dietary data that enabled analysis of the gluten intake from different types of gluten and to stratify into age groups. Participants with energy intake per kg body weight that was +3 sd of the mean were considered outliers and excluded from the analyses. The study had a high representativity as it was based on a random selection of the national population including both urban and rural areas.

CD is only induced by wheat, rye and barley. Interestingly, a small subset of coeliac patients may be intolerant to the avenin proteins, which make up only about 10 % of the total proteins of oats( 45 ). Therefore, we performed the analyses to make it possible to differentiate between the gluten intake from wheat, barley, rye and oats.

Results of the present study are useful in enabling future exploration of the association between the qualitative and quantitative consumption of gluten and the manifestations of CD.

Conclusion

This study presents representative population-based data on gluten intake in infants and young children.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to Tue Christensen, Majken Ege, Karsten Kørup and Karin Hess Ygil (Division of Nutrition, National Food Institute, Technical University of Denmark) for developing the software system and databases used in the processing of the data and for contributing to data processing. In particular, the authors thank Majken Ege for her great work when taking part in preparing and coordinating dietary intake data collection. The authors conceived the study (C. H., E. T. and S. H.), designed the analyses of the study (C. H. and E. T.) and were responsible for the design and collection of data from the National Danish Survey of Dietary Habits among Infants and Young Children (E. T.). C. H. was responsible for analyses of data and writing the manuscript. All authors participated in the discussion of the results and revision of the manuscript. This study was supported by the Danish Strategic Research Council (project no. 09-06-5149), and The National Danish Dietary Survey among Infants and Young Children was financed by the Ministry of Food, Agriculture and Fisheries. None of the authors has declared any conflict of interest.

References

- 1.American Gastroenterological Association (2001) American Gastroenterological Association medical position statement: Celiac sprue. Gastroenterology 120, 1522–1525 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hill ID, Dirks MH, Liptak GS, et al. (2005) Guideline for the diagnosis and treatment of celiac disease in children: recommendations of the North American Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 40, 1–19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mäki M & Collin P (1997) Coeliac disease. Lancet 349, 1755–1759 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Johnston SD, Watson RG, McMillan SA, et al. (1997) Prevalence of coeliac disease in Northern Ireland. Lancet 350, 1370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sanders DS, Patel D, Stephenson TJ, et al. (2003) A primary care cross-sectional study of undiagnosed adult coeliac disease. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 15, 407–413 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.West J, Logan RF, Hill PG, et al. (2003) Seroprevalence, correlates, and characteristics of undetected coeliac disease in England. Gut 52, 960–965 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fasano A, Berti I, Gerarduzzi T, et al. (2003) Prevalence of celiac disease in at-risk and not-at-risk groups in the United States: a large multicenter study. Arch Intern Med 163, 286–292 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dube C, Rostom A, Sy R, et al. (2005) The prevalence of celiac disease in average-risk and at-risk Western European populations: a systematic review. Gastroenterology 128, S57–S67 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Myleus A, Ivarsson A, Webb C, et al. (2009) Celiac disease revealed in 3 % of Swedish 12-year-olds born during an epidemic. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 49, 170–176 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ludvigsson JF & Fasano A (2012) Timing of introduction of gluten and celiac disease risk. Ann Nutr Metab 60, Suppl. 2, 22–29 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Trolle E, Gondolf UH & Christensen T (2012) Food and nutrient intake in Danish infants and young children (½–3 years). In Programme and Abstract Book. 10th Nordic Nutrition Conference, Reykjavik, Iceland, 3–5 June 2012. pp. 57–8 (abstr). Copenhagen: Nordic Council of Ministers [Google Scholar]

- 12.Statistics Denmark (2012) StatBank Denmark. Live births by age of mother and sex of child. http://www.statistikbanken.dk/statbank5a/default.asp?w=1920

- 13.Gondolf UH, Tetens I, Michaelsen KF, et al. (2012) Dietary habits of partly breast-fed and completely weaned infants at 9 months of age. Public Health Nutr 15, 578–586 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gondolf UH, Tetens I, Hills AP, et al. (2012) Validation of a pre-coded food record for infants and young children. Eur J Clin Nutr 66, 91–96 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.DTU Food, National Food Institute Technical University of Denmark (2012) Danish Food Composition Databank, ed. 7.01. http://www.foodcomp.dk/v7/fvdb_search.asp

- 16.Wieser H, Seilmeier W & Belitz HD (1980) Comparative investigations of partial amino acid sequences of prolamines and glutelins from cereals. II. Fractionation of glutelins (author's transl.). Z Lebensm Unters Forsch 171, 430–436 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.van Overbeek FM, Uil-Dieterman IG, Mol IW, et al. (1997) The daily gluten intake in relatives of patients with coeliac disease compared with that of the general Dutch population. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 9, 1097–1099 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gellrich C, Schieberle P & Weiser H (2003) Biochemical characterization and quantification of the storage protein (secalin) types in rye flour. Cereal Chem 80, 102–109 [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ellis HJ, Freedman AR & Ciclitira PJ (1990) Detection and estimation of the barley prolamin content of beer and malt to assess their suitability for patients with celiac-disease. Clin Chim Acta 189, 123–130 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nordic Council of Ministers (2004) Nordic Nutrition Recommendations 2004. Copenhagen: Nordic Council [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wells JC & Davies PS (1999) Can body size predict infant energy requirements? Arch Dis Child 81, 429–430 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Goldberg GR, Black AE, Jebb SA, et al. (1991) Critical evaluation of energy intake data using fundamental principles of energy physiology: 1. Derivation of cut-off limits to identify under-recording. Eur J Clin Nutr 45, 569–581 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Black AE (2000) Critical evaluation of energy intake using the Goldberg cut-off for energy intake:basal metabolic rate. A practical guide to its calculation, use and limitations. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord 24, 1119–1130 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Black AE (2000) The sensitivity and specificity of the Goldberg cut-off for EI:BMR for identifying diet reports of poor validity. Eur J Clin Nutr 54, 395–404 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Livingstone MB, Robson PJ, Black AE, et al. (2003) An evaluation of the sensitivity and specificity of energy expenditure measured by heart rate and the Goldberg cut-off for energy intake: basal metabolic rate for identifying mis-reporting of energy intake by adults and children: a retrospective analysis. Eur J Clin Nutr 57, 455–463 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dewey KG, Finley DA & Lonnerdal B (1984) Breast milk volume and composition during late lactation (7–20 months). J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 3, 713–720 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Picciano MF, Calkins EJ, Garrick JR, et al. (1981) Milk and mineral intakes of breastfed infants. Acta Paediatr Scand 70, 189–194 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Department of Health and Social Security (1977) The composition of mature human milk. Report of the Working Party on the Composition of Foods for Infants and Young Children Report on Health and Social Subjects no. 12. London: HMSO. [PubMed]

- 29.The National Board of Health (2005) Recommendations for the Nutrition of Infants. Recommendations for Health Personnel. Copenhagen: The National Board of Health [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pedersen AN, Fagt S, Groth MV, et al. (2010) Dietary Habits in Denmark 2003–2008. Main Results. National Food Institute, Technical University of Denmark.

- 31.Ivarsson A, Persson LA, Nystrom L, et al. (2000) Epidemic of coeliac disease in Swedish children. Acta Paediatr 89, 165–171 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ivarsson A, Hernell O, Stenlund H, et al. (2002) Breast-feeding protects against celiac disease. Am J Clin Nutr 75, 914–921 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hopman EG, Kiefte-de Jong JC, Le CS, et al. (2007) Food questionnaire for assessment of infant gluten consumption. Clin Nutr 26, 264–271 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hopman EG, Pruijn R, Tabben EH, et al. (2012) Food questionnaire for assessment of gluten intake for children of 1–4 years of age. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 54, 791–796 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Olsson C, Stenlund H, Hornell A, et al. (2009) Regional variation in celiac disease risk within Sweden revealed by the nationwide prospective incidence register. Acta Paediatr 98, 337–342 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sjoberg K & Eriksson S (1999) Regional differences in coeliac disease prevalence in Scandinavia? Scand J Gastroenterol 34, 41–45 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Weile B, Cavell B, Nivenius K, et al. (1995) Striking differences in the incidence of childhood celiac disease between Denmark and Sweden: a plausible explanation. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 21, 64–68 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Weile B & Krasilnikoff PA (1993) Extremely low incidence rates of celiac disease in the Danish population of children. J Clin Epidemiol 46, 661–664 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dydensborg S, Toftedal P, Biaggi M, et al. (2012) Increasing prevalence of coeliac disease in Denmark: a linkage study combining national registries. Acta Paediatr 101, 179–184 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ziegler AG, Schmid S, Huber D, et al. (2003) Early infant feeding and risk of developing type 1 diabetes-associated autoantibodies. JAMA 290, 1721–1728 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hoffenberg EJ, Emery LM, Barriga KJ, et al. (2004) Clinical features of children with screening-identified evidence of celiac disease. Pediatrics 113, 1254–1259 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Norris JM, Barriga K, Hoffenberg EJ, et al. (2005) Risk of celiac disease autoimmunity and timing of gluten introduction in the diet of infants at increased risk of disease. JAMA 293, 2343–2351 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Conn JA, Davies MJ, Walker RB, et al. (2009) Food and nutrient intakes of 9-month-old infants in Adelaide, Australia. Public Health Nutr 12, 2448–2456 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Noble S & Emmett P (2001) Food and nutrient intake in a cohort of 8-month-old infants in the south-west of England in 1993. Eur J Clin Nutr 55, 698–707 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Arentz-Hansen H, Fleckenstein B, Molberg O, et al. (2004) The molecular basis for oat intolerance in patients with celiac disease. PLoS Med 1, e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]