Abstract

Objective:

Cases of narcolepsy in association with psychotic features have been reported but never fully characterized. These patients present diagnostic and treatment challenges and may shed new light on immune associations in schizophrenia.

Method:

Our case series was gathered at two narcolepsy specialty centers over a 9-year period. A questionnaire was created to improve diagnosis of schizophrenia or another psychotic disorder in patients with narcolepsy. Pathophysiological investigations included full HLA Class I and II typing, testing for known systemic and intracellular/synaptic neuronal antibodies, recently described neuronal surface antibodies, and immunocytochemistry on brain sections to detect new antigens.

Results:

Ten cases were identified, one with schizoaffective disorder, one with delusional disorder, two with schizophreniform disorder, and 6 with schizophrenia. In all cases, narcolepsy manifested first in childhood or adolescence, followed by psychotic symptoms after a variable interval. These patients had auditory hallucinations, which was the most differentiating clinical feature in comparison to narcolepsy patients without psychosis. Narcolepsy therapy may have played a role in triggering psychotic symptoms but these did not reverse with changes in narcolepsy medications. Response to antipsychotic treatment was variable. Pathophysiological studies did not reveal any known autoantibodies or unusual brain immunostaining pattern. No strong HLA association outside of HLA DQB1*06:02 was found, although increased DRB3*03 and DPA1*02:01 was notable.

Conclusion:

Narcolepsy can occur in association with schizophrenia, with significant diagnostic and therapeutic challenges. Dual cases maybe under diagnosed, as onset is unusually early, often in childhood. Narcolepsy and psychosis may share an autoimmune pathology; thus, further investigations in larger samples are warranted.

Citation:

Canellas F, Lin L, Julià MR, Clemente A, Vives-Bauza C, Ollila HM, Hong SC, Arboleya SM, Einen MA, Faraco J, Fernandez-Vina M, Mignot E. Dual cases of type 1 narcolepsy with schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders. J Clin Sleep Med 2014;10(9):1011-1018.

Keywords: type 1 narcolepsy, psychotic disorders, HLA, brain autoantibodies, autoimmune

Type 1 narcolepsy is a disabling sleep disorder caused by hypocretin-1 deficiency affecting approximately 0.02% of adults worldwide.1 It is strongly associated with the DQB1*06:02 allele of the human leucocyte antigen (HLA) system,2 and is likely due to an autoimmune attack causing a specific loss of hypothalamic hypocretin-1 neurons.

Narcolepsy is characterized by the presence of daytime sleepiness, cataplectic attacks, hypnagogic/hypnopompic hallucinations, sleep paralysis, and disturbed nocturnal sleep. Initially narcolepsy was considered a psychiatric disorder, as some symptoms are reminiscent of psychiatric disorders, for instance, disordered thinking and confusion-like behaviors due to sleepiness; and psychotic-like symptoms due to hypnagogic/hypnopompic hallucinations.

BRIEF SUMMARY

Current Knowledge/Study Rationale: Rare cases of narcolepsy with psychosis have been reported but never systematically studied regarding clinical features, treatment outcomes, or potential autoimmune markers. We carefully examined a cohort of dual cases to define characteristics of hallucinations and delusions, compared to simple narcolepsy, and searched for antibodies directed against targets known to be involved in other forms of psychosis.

Study Impact: Our study will improve diagnosis and treatment of these complex cases, and provides a specialized questionnaire for clinical use. We found no evidence of antibody-mediated autoimmunity or new HLA associations, but based on our study of clinical history, we make recommendations on how to proceed.

Recently, the HLA system has been implicated in schizophrenia through several genome wide analysis studies (GWAS),3–6 making the study of psychotic symptoms in narcolepsy of special interest, and the possibility of an overlapping autoimmune pathology conceivable. Another finding linking autoimmunity and the emergence of psychotic symptoms has been the description of anti-neuronal surface antibodies in young adults who develop psychosis in the context of limbic encephalitis,7 especially anti-NMDA-receptor antibodies. These autoantibodies recognize neuronal surface antigens and have a causal relationship with the diseases. Tsutsui et al. detected anti-NMDAR antibodies in three of five hypocretin-deficient narcolepsy patients who had severe psychotic symptoms but no signs of encephalitis.8 The prevalence of antibodies to other neuronal surface proteins, such as AMPA receptor type 1 or 2, the GABA receptor, and proteins associated with the voltage-gated potassium channel, LGI1 and CASPR2, have not yet been investigated in narcolepsy patients with psychosis.

Comorbid psychiatric symptoms are more frequent in narcoleptic patients than in the general population. Among these, depression is the most frequently reported in adults.9–11 The frequency of comorbid schizophrenia is unknown, despite the fact that these two disorders have been historically related12,13 due to the many overlapping symptoms (e.g., hallucinations) and similar ages of onset. Misdiagnosis and inappropriate treatment can be more common than with other psychiatric disorders.14 In a few cases, narcolepsy has been misdiagnosed as refractory schizophrenia.15–17 There are also occasional reports of narcolepsy patients with challenging differential diagnoses with a psychotic disorder.18,19 These highlight the difficulties faced by clinicians to correctly diagnose narcolepsy and psychosis in the presence of vivid hallucinations and altered behavior. Of importance is the presence of cataplexy, the best clinical marker of HLA-associated hypocretin-1 deficiency, a finding not always reported in prior case reports. Cataplexy itself can be difficult to diagnose in the presence of another psychiatric disorder and may be inhibited by antipsychotic treatment.20,21

To complicate matters further, there are case reports of narcolepsy with paranoid psychosis emerging after treatment with psychostimulants, suggesting that treatment can also be involved.22–24 Nevertheless, there are a few reports of individual cases with a proven coexistence of narcolepsy together with a genuine psychotic disorder.25–27 Other reports do not allow definitive conclusions of whether the association with psychosis is primary, or secondary to stimulant treatments.25,28–30

Psychotic symptoms in narcolepsy have been evaluated in three controlled studies. Two studied narcolepsy, schizophrenic patients, and control subjects,31,32 while another studied narcolepsy patients versus matched controls.33 Although methodologies were different, the main conclusions were similar: the modality of hallucinations (auditory in schizophrenia vs visual and multisensory in narcolepsy) can differentiate narcolepsy from schizophrenia; and delusions are frequent in schizophrenia, but not present in narcolepsy or control subjects, except for rare instances. Moreover, in striking contrast to psychotic patients, narcolepsy patients experience hallucinations only when falling asleep, shortly after awakening, or when they are very sleepy. On the contrary, in psychotic patients hallucinations are more frequent during wakefulness when the patient is more alert.

In this work, we review a rare series of 10 patients with a well-documented diagnosis of narcolepsy together with schizophrenia or another psychotic disorder. Eight patients were diagnosed at the Stanford Center for Narcolepsy (California) over a period of 9 years. In view of the diagnostic challenges we faced in these cases, we developed a questionnaire-based interview tool with the goal of helping clinicians to differentiate true psychosis from psychotic symptoms experienced by narcoleptic patients (Diagnostic Interview for Genetic Studies Adapted for Narcolepsy [DIGSAN]). This questionnaire, modified from the Diagnostic Schedule for Genetic Studies (DIGS)34 was then tested in narcolepsy cases diagnosed at St. Vincent's hospital in Korea, where two additional cases were identified. Based on the autoimmune basis of narcolepsy, we hypothesized that antineuronal surface autoantibodies could be present in some patients with the dual diagnosis, potentially in a higher proportion than in patients with a diagnosis of psychosis. We therefore performed a systematic study of this unique cohort of dual-diagnosis cases by performing HLA typing and screening for autoimmune markers of the central nervous system (CNS), as well as antibodies linked to systemic autoimmune diseases. The study of narcolepsy cases associated with psychotic disorders may provide novel insights into the pathophysiology of both illnesses that could share an autoimmune mechanism.

SUBJECTS AND METHODS

Stanford and Korean Samples

Eight patients with cataplexy and psychosis were identified from 2003-2012 at the Stanford Sleep Clinic among a total of over 300 diagnosed patients. All presented with typical HLA DQB1*06:02-positive narcolepsy with cataplexy. Diagnosis was confirmed by nocturnal polysomnography (PSG) and a multiple sleep latency test (MSLT). Four of 8 had documented low CSF hypocretin-1. All but one had also been diagnosed with a concurrent psychiatric psychotic disorder by a psychiatrist external to the sleep center. Additional cases were identified within a large cohort at St. Vincent's hospital in Korea (see Testing the DIGSAN below). Of 3 initial subjects, 2 were found to have clear cataplexy and were finally included. For immunological studies, each patient was paired with an ethnically and age-matched control. Sera from all cases and controls were studied blind of diagnosis.

Development of the DIGSAN

Based on the experience with these patients, we built a specialized questionnaire (DIGSAN). It was designed to be as short as possible and clinically usable. Nevertheless, it has to be administered by a clinician or a trained professional in sleep disorders.

The questionnaire is structured in 5 sections: Section I Demographics, section II Family History, section III Narcolepsy symptom survey, section IV Medical History, and section V Psychosis Interview. Material to study psychiatric symptoms was drawn from section K (Psychosis) of the DIGS 3.0 version 03-Nov-1999. Material from section F (Depression) and G (Mania) was added to obtain data regarding incidental mood disorders.

For non-psychiatrist interviewers, it is important to note that for questions in the psychosis interview (section V), particularly numbers 8, 9, and 10, the interviewer has to consider not only the patient's verbal answers, but also other information such as their behavior, as well as input from relatives and clinical records, if available. The DIGSAN was built to help to assign a unique or dual diagnosis for patients with narcolepsy; in the case of a dual diagnosis, a consensus with both a sleep disorders specialist and a psychiatrist is needed. The questionnaire is included in the supplemental material.

Testing the DIGSAN

We tested the DIGSAN by administering it to 3 patients having a dual diagnosis of narcolepsy and schizophrenia at St Vincent's hospital, Korea, from a cohort of over 300 narcolepsy patients. Methods for the cohort evaluation were reported in Hong et al.,35 although the sample has been continually extended through 2012. Of these 3 subjects, 2 were found to have clear cataplexy based on the DIGSAN and further review, and were included.

Screening of Autoantibodies Associated with Systemic Autoimmune Diseases

Antinuclear antibodies (ANA) were determined by indirect immunofluorescence (IFI) on Hep2 lines (INOVA, San Diego, USA). ANA titers < 1:160 were considered negative. Anti-ENA and anti-Ribosomal P antibodies were screened by line immunoblot assay (Innogenetics, Gent, Belgium), and reactive sera were studied by a semiquantitative ELISA for specific antigens: SSA, SSB, U1RNP, or Sm (INOVA) or a quantitative ELISA (for Scl70 or Jo1)(Phadia AB, Uppsala, Sweden).

In ANA positive samples with a homogeneous pattern, we tested for the presence of anti-double-stranded DNA (dsDNA) antibodies by IFI on Crithidia luciliae slides (INOVA).

Onconeural Antibody Detection

Onconeural antibodies were screened by IFI, at 1:10 titer, on rat cerebellum sections (Euroimmun AG, Luebeck, Germany). Primate cerebellum slides (Euroimmun AG) were used to confirm positive reactions on rat cerebellum.

We also tested antibodies to 9 known intracellular synaptic antigens: amphiphysin, GAD65, Hu, Yo, CV2, Ri, Ma1, Ma2, and SOX-1, by line immunoblot assay (RAVO Diagnostika, Freiburg, Germany).

Neuronal Surface Antibody Detection

Neuronal surface antibodies (NSAbs) were studied by a “Cell Based Assay” (CBA), according to the method of Wandinger et al.36 Serum samples were tested at a starting dilution of 1:10, by IFI, on rat cerebellum and hippocampus sections and transfected HEK293 cells. HEK293 cells expressed one of these antigens: the glutamate receptor type NMDA (subunit NR1), the AMPA receptor type 1 or 2, the GABA receptor, or one of the proteins associated to the voltage-gated potassium channel: leucine-rich glioma inactivated 1 (LGI1) or Contactin associated protein 2 (CASPR2) (Euroimmun AG).

All tests were performed blindly and IFI images interpreted independently by two observers

HLA Typing

A, B, C, DR, DQ, and DP typing was conducted in all cases with (i) cataplexy or hypocretin-1 deficiency and (ii) long standing psychosis, totaling 10 samples. High-resolution typing was obtained using the Luminex xMAP Technology. Allele frequencies were obtained from http://bioinformatics.nmdp.org/ and other sources.

RESULTS

Clinical Data

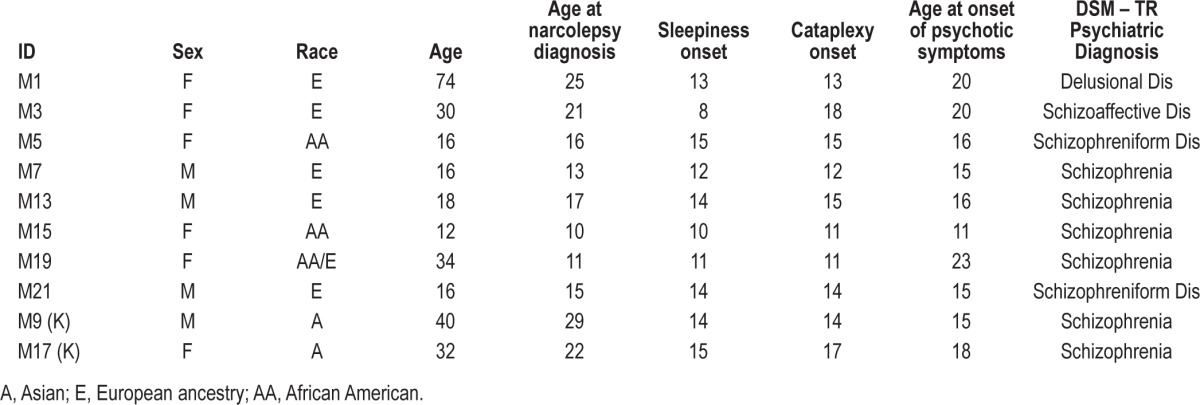

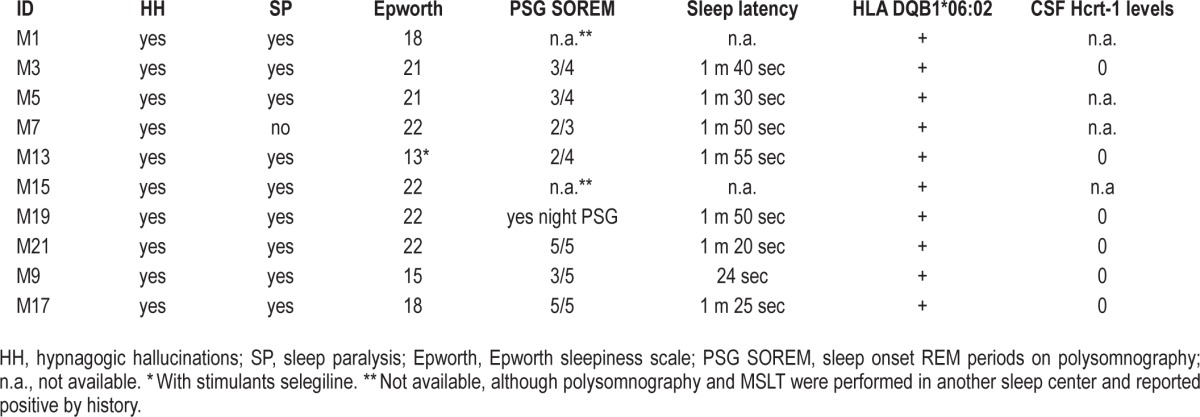

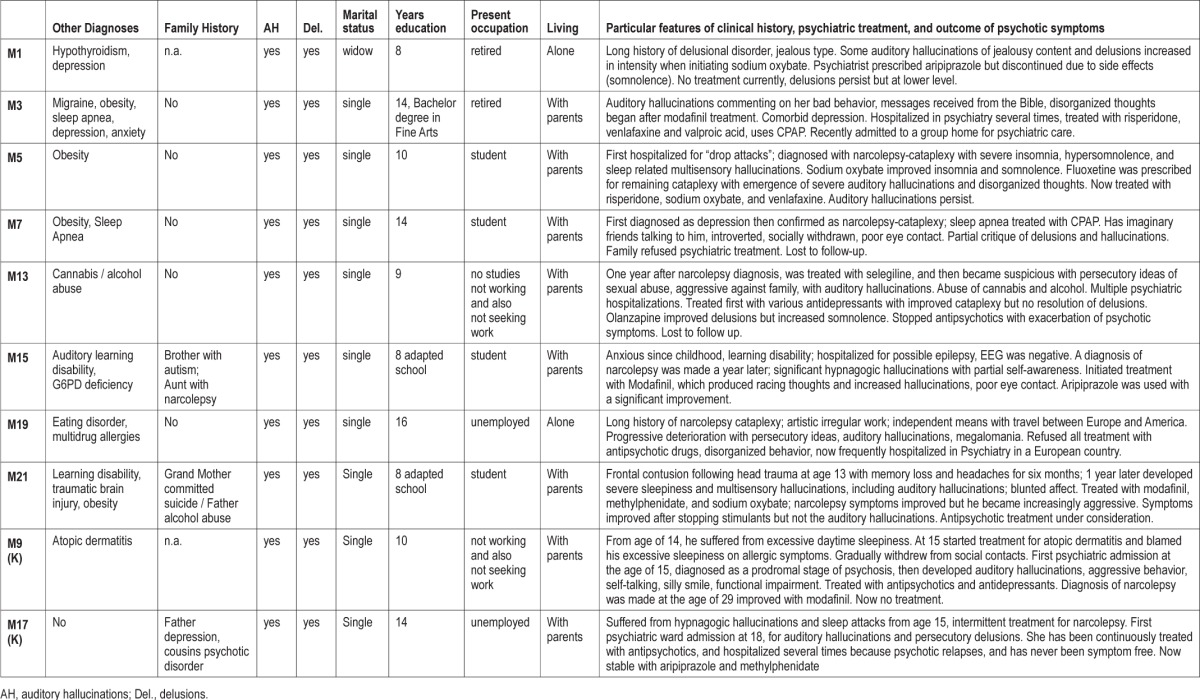

Demographic, sleep clinical, and psychiatric diagnostic data for the patients are summarized in Tables 1, 2, and 3, respectively.

Table 1.

Summary data of patients.

Table 2.

Narcolepsy data.

Table 3.

Psychiatric description of patients.

Regarding narcolepsy, all cases were typical type I narcolepsy patients. Age of onset was younger than usual, including 4 children (younger than 12 years) and 6 adolescents (12-18 years). Clinically, patients had the complete clinical “tetrad” of symptoms, except for one patient who did not report sleep paralysis. Somnolence was severe as shown by a high Epworth Sleepiness Scale score (typically > 20) and short mean sleep latencies during MSLTs (< 2 minutes). All had hypnagogic/hypnopompic hallucinations that were multisensory (visual, kinesthetic, olfactory, gustative) and related to drowsiness or sleep onset.

Regarding psychosis, patients were formally diagnosed according to DSM-IV-TR criteria as: schizophrenia (6 patients), schizoaffective disorder (1 patient), schizophreniform disorder (2 patients) and delusional disorder (1 patient). In all cases but one, diagnosis was made by external psychiatrists who provided psychiatric follow-up. Case M7 was diagnosed at the Stanford Sleep Clinic by EM, but he and his family rejected psychiatric diagnosis and were lost to follow-up.

All cases except M1 had persistent auditory hallucinations during the wake period and presented with typical features of schizophrenia paranoid type: disorganized thinking and behavior and delusions. Auditory hallucinations were of paranoid and mystic content, and all of the patients also had delusional ideas, the majority being persecutory, with increased suspicions and ideas of reference. All patients reported florid and severe hypnagogic hallucinations and vivid dreaming, consistent with those observed in narcolepsy; however, these occurred not only at sleep onset, but also frequently during daytime. In addition, they were chronically convinced of the reality of the hallucinations. There was typically an absence of insight regarding these ideas. In several cases, family and psychiatric records described anxiety and sadness. Flat affect was described in 5 of the patients. Patients also had disorganized behavior, tended to avoid social contacts, and had difficulties in their social lives and relationships. All had academic and/or work difficulties and demonstrated less personal and social achievement than could be expected by their age and cultural level even compared to other narcoleptic patients.

Table 3 describes the clinical history and particular clinical features of each of these patients, with psychiatric treatment and the outcome of psychotic symptoms when available.

Four cases carried additional comorbid psychiatric diagnoses: learning disabilities (2), eating disorder (anorexia nervosa) (1), and drug abuse (1). The last patient was the only one who presented with unusually aggressive behavior. Four of the 10 cases had family history of narcolepsy (2) and psychiatric disorder (3). One patient (M15) had antecedents of both narcolepsy (aunt) and psychiatric disorder (brother, autism); she also had G6PD deficiency and learning disability due to abnormal auditory processing. She also had the earliest onset of psychotic symptoms; was diagnosed with early onset schizophrenia, and the psychiatrist initiated aripiprazole with a good control of psychotic symptoms.

Onset of psychotic symptoms generally followed narcolepsy, although it was concomitant in several cases, particularly in early onset cases, and within 3 years in all other cases except M1 and M19. Two patients had psychotic symptoms for less than 6 months at the time of the study (M5, M21), and thus have a provisional diagnosis of schizophreniform disorder. Obesity, a common feature of childhood narcolepsy, was present in 4 cases, and 2 were treated with continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP).

All patients, except Korean case M9, started treatment for narcolepsy before the antipsychotic treatment. Treatments used were: sodium oxybate, and stimulants alone (modafinil, methylphenidate, selegiline) or combined with antidepressants as fluoxetine and venlafaxine. In none of these cases did delusions and auditory hallucinations improve after cessation of narcolepsy treatment. In one case (M1), there was a clear relationship between treatment initiation and increase of psychotic symptoms. This patient had persecutory and jealous delusions for several years; the delusions became more visible after initiation of treatment with sodium oxybate. Another case, M19, had a long history of narcolepsy-cataplexy, was intolerant of stimulant medication, and developed psychosis many years after onset. The response to antipsychotic therapy was highly variable in these patients, ranging from excellent (M3, M15) to very poor (most others), with frequent refusal of psychiatric therapy.

Autoantibody Testing

Only serum n.4 was ANA positive, and presented a dense speckled fine pattern, compatible with the presence of anti-DSF70 antibodies, which is a frequent ANA pattern found in healthy people and not associated with systemic autoimmune diseases.

Autoantibodies directed to specific antigens linked to systemic autoimmune diseases (ENA, Ribosomal P or dsDNA) were negative in all sera.

Immunostaining of rat cerebellum showed a positive reaction only in serum n.13, which yielded a granular cytoplasmic pattern in Purkinje cells. We ruled out the presence of anti-Yo antibodies using line immunoblot studies. This serum sample did not present a positive immunofluorescence pattern on primate cerebellum, and we interpret these results as an artifact reaction due to a heterophilic antibody against a rat antigen. None of the samples showed the characteristic anti-aquaporin 4 pattern on cerebellum slides. Immunofluorescence on hippocampus sections and specific CBA tests were negative in all sera.

HLA Typing

No shared HLA allele was found (see Table S1, supplemental material). The frequency of HLA C*01:02, an allele previously reported to be associated with schizophrenia in a large cohort of patients, was not increased versus what could be expected, as none of the patients carried this particular allele. Similarly, the carrier frequency of the protective haplotype DRB1*03:01, DQA1*05:01, DQB1*02:01 (30%) was unremarkable and slightly increased versus what would be expected in controls (approximate allele frequency in such a mixed group: 10%). Two unusual findings were the observation of an absence of DRB4 genes (and associated DRB1*04, DRB1*07, and DRB1*09), and a high number of DRB3*03 alleles (80%), a finding that would need a much larger sample to confirm.

DISCUSSION

The co-occurrence of narcolepsy with psychotic symptoms raises clinical and pathophysiological questions. At the clinical level, narcolepsy can be misdiagnosed as a psychiatric condition, especially if cataplexy is not reported, or is unrecognized by the physician. In adolescents, misdiagnosis often results from overlapping age of onset and symptoms (notably hallucinations, and behavioral problems) between narcolepsy and schizophrenia.14,16,27 The fact that adolescents often go through difficult maturational issues often further confuses the picture, especially when communication is poor and when patients refuse treatment or the reality of the condition. In our case series, narcolepsy symptoms began during childhood or adolescent years but was often not diagnosed for years, and in a number of cases, was not identified until after psychotic symptoms had manifested (Table 1). Recently the diagnostic delay for narcolepsy has dramatically shortened, with diagnosis occurring close to onset (childhood and adolescence), emphasizing the importance of differentiating emerging and evolving symptoms of narcolepsy vs schizophrenia.

Prepubertal children pose special diagnostic problems. When cataplexy or atonia episodes are preeminent, a misdiagnosis of Pediatric Autoimmune Neurological Disease associated with Streptococcus (PANDAS), seizures, or paraneoplastic syndrome can be made.37 Indeed, the characteristics of emergent cataplexy in children are quite different from those of established cataplexy, complicating diagnosis.38 Irritability, anger, and at times violent behaviors, all secondary to sleepiness, may emerge suddenly in a child who was previously well-behaved and has gained large amount of weight. The change in character can be dramatic but is entirely reversible when treating sleepiness and REM-related symptoms. When hypnagogic hallucinations are preeminent, young children, depending on their maturational stage, may not be able to fully comprehend that these are unreal experiences, especially just after waking up. In most cases, however, children accept that these are similar to dreams once explained carefully by the clinician—a critical difference compared to schizophrenia or true psychotic disorder. Based on the above, when in doubt and unless proven otherwise, it is always better to treat narcolepsy first, hoping all psychotic symptoms are narcolepsy-related rather than the converse, especially if the premorbid personality was entirely normal.

The focus of this report are the rare cases in which narcolepsy is genuinely associated with schizophrenia or other psychotic disorders unrelated to the dream-like multisensory hallucinations characteristic of the narcolepsy syndrome. In these cases, we found that the auditory hallucinations appear always together with multisensory (visual, kinesthetic, olfactory, gustative) ones, and complex delusions (persecutory ideas, increased suspicions, ideas of reference) are present. Thinking may be disorganized, although this can be difficult to demonstrate when the individual is very sleepy. In these dual diagnosis cases, the patient generally believes the hallucinations and delusions are real and cannot be easily convinced otherwise. Two possible options then need to be considered: the psychosis may be a side effect of treatment, or the development of an unrelated psychiatric comorbid condition.

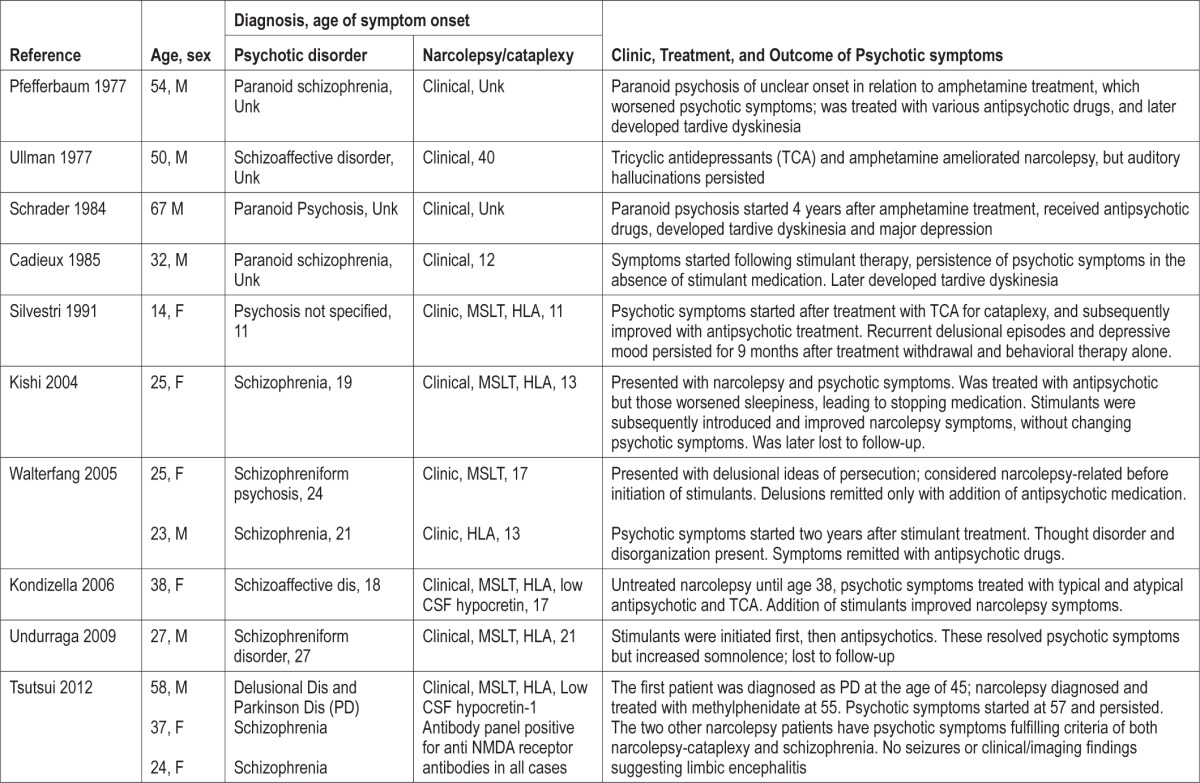

Table 4 reviews the few previously published cases of narcolepsy associated with psychosis. As in our case series, narcolepsy onset typically preceded the onset of psychotic symptoms. In many of these older reports, it is difficult to evaluate whether therapy played a crucial role in the development of psychosis.

Table 4.

Clinical characteristics of previously published dual cases.

Until recently, stimulant therapy was the main treatment for narcolepsy, and these compounds are well known to trigger psychosis.39 Psychotic symptoms may be induced most often by amphetamine or methylphenidate, but also modafinil.40–44 In this case series, we believe medication was likely a minor factor in the development of psychosis, except in patient M1. In this instance, the diagnosis was delusional disorder rather than schizophrenia, thinking remained organized, and ideation was of the jealous type. In other cases, treatment with antidepressants, stimulants or sodium oxybate may have contributed to precipitating the condition or exacerbated a preexisting one; although it is also possible the underlying schizophrenia became more evident as sleepiness lifted with treatment. Similarly, these patients also had florid hypnagogic hallucinations, which may have fueled the schizophrenia-type delusions without being the sole cause. In several cases close to onset, it is also difficult to exclude the possibility of a natural evolution of the disorder with time, independent of treatment.

In four cases, additional comorbid psychiatric diagnoses were present: learning disabilities, eating disorder, and drug abuse. Four cases had family history of narcolepsy or psychiatric disorder, and one had antecedents of both narcolepsy and psychiatric disorder. This suggests a double diagnosis should be considered, particularly in subjects with known risk factors associated with development of psychosis: family psychiatric history, low intelligence level, personal history of head injury,45 environmental distress, and cannabis use.46 The findings in our series agree with previous findings reported in Table 4. Silvestri described a girl with a narcolepsy onset at age 11 who had psychiatric family antecedents of psychosis.26

All of our dual diagnosis cases except M1 had persistent auditory hallucinations during the wake period, an uncommon feature in narcolepsy. Moreover, they were chronically convinced of the reality of the hallucinations. Importantly there was an absence of insight regarding these ideas as is typical of patients with chronic psychosis. In addition, our patients tended to avoid social contacts and experienced difficulties in their professional and social lives and relationships.

Treatment response for the dual diagnosis patients was variable and involved balancing narcolepsy therapies to reduce cataplexy, REM-like hallucinations, and sleepiness with antipsychotic drug treatment, which reduces delusions and hallucinations but induces sleepiness. It is important to evaluate the existence of delusional ideas that may be hidden by the patient. Treatment with stimulants alone can worsen psychotic symptoms,40 but in our experience, stimulant can be used if no overstimulation results. Regarding non-narcolepsy psychotic symptoms, aripiprazole was used, as it is less sedating. In other cases, risperidone was successfully used. It is our experience that undertreating narcolepsy is more often the end result, as untreated sleepiness reduces behavioral problems.

The frequency of hypocretin deficiency in association with schizophrenia is unknown. While co-occurrence is reportedly low, dual cases may be more frequent as a result of misdiagnosis. Clinicians should be mindful that the two syndromes can coexist, and that at minimum one diagnosis does not exclude the other. We believe the DIGSAN can be a useful tool for clinicians to distinguish each separate diagnosis. This is particularly important now that biological tests are available,47 and others will be developed soon. Accurate diagnosis is critically important for the outcome, as treatment is different for the two diseases, and good treatments are currently available for each illness.

The coexistence of narcolepsy with schizophrenia also raises interesting pathophysiological questions. It may be a chance finding, or an association of two co-clustering autoimmune diseases, as often found in other cases where specific autoimmune diseases can coexist more frequently than expected by chance alone. A large number of HLA association studies in small schizophrenia samples have produced controversial results.6 One suggested that DR15 or DQB1*06:02 were more frequent in schizophrenia versus controls,48 although this was not consistently replicated.49 More recently, using large samples of schizophrenia cases and controls, GWAS studies found clear signals in the HLA region.3–6 Due to the high level of linkage disequilibrium in the region, the signal has been difficult to map, but it is interesting to note that HLA DRB1*03:01 and DRB1*13:03 appeared to confer protection for the illness,3,5 while DQB1*06:02 frequency was slightly increased. More recently, carriers of the rare HLA C*01:02 allele have been reported to be at increased risk,3 a finding that awaits replication. In this study, we fully HLA typed 10 cases with narcolepsy and psychotic disorder, but no clear association emerged in addition to the expected DQB1*06:02 narcolepsy association; notably we did not find increased HLA C*01:02 nor a protective effect of DRB1*03:01, which was, if anything, increased in frequency. These results indicate that psychosis in these dual diagnosis patients is either a chance finding not related to autoimmunity, or mediated through DQB1*06:02. Alternatively, further heterogeneity in schizophrenia associated with these cases may have masked the association in this small sample.

In our series we failed to identify anti-NMDA-receptor antibodies described by Tsutsui et al.8 in three of five hypocretindeficient narcolepsy patients with severe psychotic symptoms. We also examined other potential CNS targets and antibodies linked to systemic autoimmune diseases, including the AMPA receptor type 1 or 2, the GABA receptor, proteins associated with the voltage-gated potassium channel, LGI1 and CASPR2, but we could not find any abnormalities. Immunocytochemical studies of brain sections were also conducted without positive results.

In addition to surface and cytoplasmic/synaptic neuronal antibodies, we also screened for antibodies linked to systemic autoimmune diseases (ENA, ribosomal P, dsDNA). Some of these have not previously been studied in narcolepsy and are associated with central nervous system involvement. The rationale is that these studies provide an indirect assessment of patients' autoimmune background, and help to discriminate whether immunofluorescence patterns found on hippocampus or cerebellum sections are due to non-organ-specific vs neuronal-specific antibodies. Again, no abnormalities were identified in our case series.

In conclusion, narcolepsy associated with genuine psychosis is a clear entity that presents specific diagnostic and therapeutic challenges. In our present study, we were unable to substantiate the hypothesis that the psychosis is autoimmune-mediated. Importantly, however, we only examined sera for the presence of autoantibodies and did not explore a potential pathology mediated by cytotoxic T cells. In narcolepsy, autoantibodies have not been consistently found in sera or CSF50,51; however, there is now clear evidence of T cell mediated destruction of hypocretin cells.52 It is therefore possible that a similar cell-mediated mechanism may precipitate schizophrenia in these cases, warranting additional pathophysiological and therapeutic investigation.

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

This was not an industry supported study. Support Grants: FISS PI10/00716 and INT11/007, 2012 to Dr. Canellas; NIH-NS23724 to Dr. Mignot. The study was performed at the Center for Sleep Sciences and Medicine, Stanford University School of Medicine. The authors have indicated no financial conflicts of interest.

SUPPLEMENTAL MATERIAL

HLA typing results in 10 patienst with narcolepsy and long standing psychosis

REFERENCES

- 1.Dauvilliers Y, Arnulf I, Mignot E. Narcolepsy with cataplexy. Lancet. 2007;369:499–511. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60237-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mignot E, Lin X, Kalil J, et al. DQB1-0602 (DQw1) is not present in most nonDR2 Caucasian narcoleptics. Sleep. 1992;15:415–22. doi: 10.1093/sleep/15.5.415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Irish Schizophrenia Genomics C, the Wellcome Trust Case Control C Genome-wide association study implicates HLA-C*01:02 as a risk factor at the major histocompatibility complex locus in schizophrenia. Biol Psychiatry. 2012;72:620–8. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2012.05.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shi J, Levinson DF, Duan J, et al. Common variants on chromosome 6p22.1 are associated with schizophrenia. Nature. 2009;460:753–57. doi: 10.1038/nature08192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stefansson H, Ophoff RA, Steinberg S, et al. Common variants conferring risk of schizophrenia. Nature. 2009;460:744–47. doi: 10.1038/nature08186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Debnath M, Cannon DM, Venkatasubramanian G. Variation in the major histocompatibility complex [MHC] gene family in schizophrenia: associations and functional implications. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2013;42:49–62. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2012.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dalmau J, Gleichman AJ, Hughes EG, et al. Anti-NMDA-receptor encephalitis: case series and analysis of the effects of antibodies. Lancet Neurol. 2008;7:1091–8. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(08)70224-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tsutsui K, Kanbayashi T, Tanaka K, et al. Anti-NMDA-receptor antibody detected in encephalitis, schizophrenia, and narcolepsy with psychotic features. BMC Psychiatry. 2012;12 doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-12-37. 37-244X-12-37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ohayon MM. Narcolepsy is complicated by high medical and psychiatric comorbidities: a comparison with the general population. Sleep Med. 2013;14:488–92. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2013.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kales A, Soldatos CR, Bixler EO, et al. Narcolepsy-cataplexy. II. Psychosocial consequences and associated psychopathology. Arch Neurol. 1982;39:169–71. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1982.00510150039009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Frauscher B, Ehrmann L, Mitterling T, et al. Delayed diagnosis, range of severity, and multiple sleep comorbidities: a clinical and polysomnographic analysis of 100 patients of the innsbruck narcolepsy cohort. J Clin Sleep Med. 2013;9:805–12. doi: 10.5664/jcsm.2926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shapiro B, Spitz H. Problems in the differential diagnosis of narcolepsy versus schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 1976;133:1321–3. doi: 10.1176/ajp.133.11.1321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fortuyn HA, Mulders PC, Renier WO, Buitelaar JK, Overeem S. Narcolepsy and psychiatry: an evolving association of increasing interest. Sleep Med. 2011;12:714–9. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2011.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Benca RM. Narcolepsy and excessive daytime sleepiness: diagnostic considerations, epidemiology, and comorbidities. J Clin Psychiatry. 2007;68(Suppl 13):5–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Douglass AB, Shipley JE, Haines RF, Scholten RC, Dudley E, Tapp A. Schizophrenia, narcolepsy, and HLA-DR15, DQ6. Biol Psychiatry. 1993;34:773–80. doi: 10.1016/0006-3223(93)90066-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Douglass AB, Hays P, Pazderka F, Russell JM. Florid refractory schizophrenias that turn out to be treatable variants of HLA-associated narcolepsy. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1991;179:12–7. doi: 10.1097/00005053-199101000-00003. discussion 18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Talih FR. Narcolepsy presenting as schizophrenia: a literature review and two case reports. Innov Clin Neurosci. 2011;8:30–4. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Szucs A, Janszky J, Hollo A, Migleczi G, Halasz P. Misleading hallucinations in unrecognized narcolepsy. Acta Psychiatr Scan. 2003;108:314–6. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0447.2003.00114.x. discussion 16-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Takeuchi N, Mukai M, Uchimura N, Satomura T, Sakamoto T, Maeda H. A narcoleptic patient exhibiting hallucinations and delusion. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2000;54:321–2. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1819.2000.00696.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Krahn LE. Reevaluating spells initially identified as cataplexy. Sleep Med. 2005;6:537–42. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2005.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Okura M, Riehl J, Mignot E, Nishino S. Sulpiride, a D2/D3 blocker, reduces cataplexy but not REM sleep in canine narcolepsy. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2000;23:528–38. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(00)00140-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schrader G, Hicks EP. Narcolepsy, paranoid psychosis, major depression, and tardive dyskinesia. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1984;172:439–41. doi: 10.1097/00005053-198407000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pfefferbaum A, Berger PA. Narcolepsy, paranoid psychosis, and tardive dyskinesia: a pharmacological dilemma. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1977;164:293–7. doi: 10.1097/00005053-197704000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cadieux RJ, Kales JD, Kales A, Biever J, Mann LD. Pharmacologic and psychotherapeutic issues in coexistent paranoid schizophrenia and narcolepsy: case report. J Clin Psychiatry. 1985;46:191–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kishi Y, Konishi S, Koizumi S, Kudo Y, Kurosawa H, Kathol RG. Schizophrenia and narcolepsy: a review with a case report. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2004;58:117–24. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1819.2003.01204.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Silvestri R, Montagnese C, De Domenico P, et al. Narcolepsy and psychopathology. A case report. Acta Neurol. 1991;13:275–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kondziella D, Arlien-Soborg P. Diagnostic and therapeutic challenges in narcolepsy-related psychosis. J Clin Psychiatry. 2006;67:1817–9. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v67n1122b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ullman KC. Narcolepsy and schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 1977;134:822. doi: 10.1176/ajp.134.7.822b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Walterfang M, Upjohn E, Velakoulis D. Is schizophrenia associated with narcolepsy? Cogn Behav Neurol. 2005;18:113–8. doi: 10.1097/01.wnn.0000160822.53577.2c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Undurraga J, Garrido J, Santamaria J, Parellada E. Treatment of narcolepsy complicated by psychotic symptoms. Psychosomatics. 2009;50:427–8. doi: 10.1176/appi.psy.50.4.427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dahmen N, Kasten M, Mittag K, Muller MJ. Narcoleptic and schizophrenic hallucinations. Implications for differential diagnosis and pathophysiology. The Eur J Health Econ. 2002;3(Suppl 2):S94–8. doi: 10.1007/s10198-002-0113-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fortuyn HA, Lappenschaar GA, Nienhuis FJ, et al. Psychotic symptoms in narcolepsy: phenomenology and a comparison with schizophrenia. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2009;31:146–54. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2008.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vourdas A, Shneerson JM, Gregory CA, et al. Narcolepsy and psychopathology: is there an association? Sleep Med. 2002;3:353–60. doi: 10.1016/s1389-9457(02)00062-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nurnberger JI, Jr., Blehar MC, Kaufmann CA, et al. Diagnostic interview for genetic studies. Rationale, unique features, and training. NIMH Genetics Initiative. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1994;51:849–59. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1994.03950110009002. discussion 63-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hong SC, Lin L, Jeong JH, et al. A study of the diagnostic utility of HLA typing, CSF hypocretin-1 measurements, and MSLT testing for the diagnosis of narcolepsy in 163 Korean patients with unexplained excessive daytime sleepiness. Sleep. 2006;29:1429–38. doi: 10.1093/sleep/29.11.1429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wandinger KP, Saschenbrecker S, Stoecker W, Dalmau J. Anti-NMDA-receptor encephalitis: a severe, multistage, treatable disorder presenting with psychosis. J Neuroimmunol. 2011;231:86–91. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2010.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Aran A, Einen M, Lin L, Plazzi G, Nishino S, Mignot E. Clinical and therapeutic aspects of childhood narcolepsy-cataplexy: a retrospective study of 51 children. Sleep. 2010;33:1457–64. doi: 10.1093/sleep/33.11.1457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Plazzi G, Pizza F, Palaia V, et al. Complex movement disorders at disease onset in childhood narcolepsy with cataplexy. Brain. 2011;134:3480–92. doi: 10.1093/brain/awr244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Auger RR, Goodman SH, Silber MH, Krahn LE, Pankratz VS, Slocumb NL. Risks of high-dose stimulants in the treatment of disorders of excessive somnolence: a case-control study. Sleep. 2005;28:667–72. doi: 10.1093/sleep/28.6.667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Guilleminault C. Amphetamines and narcolepsy: use of the Stanford database. Sleep. 1993;16:199–201. doi: 10.1093/sleep/16.3.199a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pawluk LK, Hurwitz TD, Schluter JL, Ullevig C, Mahowald MW. Psychiatric morbidity in narcoleptics on chronic high dose methylphenidate therapy. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1995;183:45–8. doi: 10.1097/00005053-199501000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Narendran R, Young CM, Valenti AM, Nickolova MK, Pristach CA. Is psychosis exacerbated by modafinil? Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2002;59:292–3. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.59.3.292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ivanenko A, Tauman R, Gozal D. Modafinil in the treatment of excessive daytime sleepiness in children. Sleep Med. 2003;4:579–82. doi: 10.1016/s1389-9457(03)00162-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Crosby MI, Bradshaw DA, McLay RN. Severe mania complicating treatment of narcolepsy with cataplexy. J Clin Sleep Med. 2011;7:214–6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ohayon MM. Prevalence of hallucinations and their pathological associations in the general population. Psychiatr Res. 2000;97:153–64. doi: 10.1016/s0165-1781(00)00227-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.van Os J, Kenis G, Rutten BP. The environment and schizophrenia. Nature. 2010;468:203–12. doi: 10.1038/nature09563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mignot E, Lammers GJ, Ripley B, et al. The role of cerebrospinal fluid hypocretin measurement in the diagnosis of narcolepsy and other hypersomnias. Arch Neurol. 2002;59:1553–62. doi: 10.1001/archneur.59.10.1553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Grosskopf A, Muller N, Malo A, Wank R. Potential role for the narcolepsy- and multiple sclerosis-associated HLA allele DQB1*0602 in schizophrenia subtypes. Schizophr Res. 1998;30:187–9. doi: 10.1016/s0920-9964(97)00148-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wright P, Nimgaonkar VL, Donaldson PT, Murray RM. Schizophrenia and HLA: a review. Schizophr Res. 2001;47:1–12. doi: 10.1016/s0920-9964(00)00022-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Cvetkovic-Lopes V, Bayer L, Dorsaz S, et al. Elevated Tribbles homolog 2-specific antibody levels in narcolepsy patients. J Clin Invest. 2010;120:713–9. doi: 10.1172/JCI41366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Dauvilliers Y, Montplaisir J, Cochen V, et al. Post-H1N1 narcolepsy-cataplexy. Sleep. 2010;33:1428–30. doi: 10.1093/sleep/33.11.1428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.De la Herran-Arita AK, Kornum BR, Mahlios J, et al. CD4+ T Cell Autoimmunity to Hypocretin/orexin and cross-reactivity to a 2009 H1N1 Influenza A Epitope in narcolepsy. Sci Transl Med. 2013;5 doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3007762. 216ra176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

HLA typing results in 10 patienst with narcolepsy and long standing psychosis