Abstract

Introduction:

Vulnerability to stress-related sleep disturbances and maladaptive sleep beliefs has been proposed to be predisposing factors for insomnia. Yet previous studies addressing these factors have been cross-sectional in nature and could not be used to infer the time sequences of the association. The current study used a six-year follow-up to examine the predisposing roles of these two factors and their interactions with major life stressors in the development of insomnia.

Methods:

One hundred seventeen college students recruited for a survey in 2006 participated in this follow-up survey in 2012. In 2006, they completed a packet of questionnaires including the Dysfunctional Beliefs and Attitudes about Sleep Questionnaire, 10-item version (DBAS-10), the Ford Insomnia Response to Stress Test (FIRST), and the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI); in 2012 they completed the Insomnia Severity Index (ISI) and the modified Life Experiences Survey (LES).

Results:

Fourteen of the participants were found to suffer from insomnia as measured by the ISI. Logistic regression showed that scores on both DBAS-10 and FIRST could predict insomnia at follow-up. When the interaction of DBAS-10 and LES and that of FIRST and LES were added, both DBAS-10 and FIRST remained significant predictors, while the interaction of FIRST and LES showed a near-significant trend in predicting insomnia.

Conclusions:

The results showed that both vulnerability to stress-related sleep disturbances and maladaptive sleep beliefs are predisposing factors for insomnia. The hypothesized interaction effect between sleep vulnerability and major life stressors was found to be marginal. The maladaptive sleep beliefs, on the other hand, showed a predisposing effect independent from the influences of negative life events.

Citation:

Yang CM, Hung CY, Lee HC. Stress-related sleep vulnerability and maladaptive sleep beliefs predict insomnia at long-term follow-up. J Clin Sleep Med 2014;10(9):997-1001.

Keywords: insomnia, dysfunctional sleep belief, sleep vulnerability

Insomnia is among the most common health complaints. It is estimated that about one-third of the adult population exhibits insomnia symptoms; 9% to 15% report sleep difficulties and daytime consequences; and about 6% show symptoms of diagnosable insomnia.1 It can significantly impact not only nighttime sleep but also daytime functioning.2–5

BRIEF SUMMARY

Current Knowledge/Study Rationale: Vulnerability to stress-related sleep disturbances and maladaptive sleep beliefs has been proposed to predispose the development of insomnia. The current study aims to confirm the predisposing roles of these factors with a longitudinal survey study.

Study Impact: The findings that both vulnerability to stress-related sleep disturbances and maladaptive sleep beliefs are predisposing factors for insomnia provide a direction to identify individuals with higher risk for insomnia. Preventive strategies can then be applied to reduce their risk of developing chronic insomnia.

In spite of the prevalence and significant impacts of insomnia, the understanding of its etiology is still limited. Spielman in 1986 proposed a 3-P model that conceptualized the contributing factors of chronic insomnia into three categories: predisposing factors that set the stage for the development of insomnia, precipitating factors that trigger the onset of insomnia, and perpetuating factors that maintain long-term sleep difficulties.6 Several etiological models have been proposed to illustrate the interaction between psychological/behavioral factors and neurophysiological mechanisms for sleep/wake regulation that may initiate and maintain insomnia.7–11 In these models, psychological and behavioral factors, such as dysfunctional beliefs about sleep, maladaptive sleep-related behaviors, and conditioned hyperarousal were identified as playing a major role in the perpetuation of insomnia. Stress, on the other hand, is the most common precipitating factor. These models are based primarily on the accumulated body of literature comparing various psychological and associated physiological measures in insomnia patients and good sleepers. For example, several studies have demonstrated that poor sleepers and patients with insomnia have more dysfunctional beliefs about sleep,12–14 a greater prevalence of intrusive thoughts, worry and rumination prior to sleep,15–17 poorer sleep hygiene practices,18–20 and less perceived control over stress and more emotional coping styles.22 Although these studies have provided support for the association between these psychological and behavioral factors and chronic insomnia, the contributions of these factors at different points along the developmental course of chronic insomnia remain to be examined. Also, relatively few studies have addressed the predisposing factors of insomnia. A recent review has proposed that genetic predispositions (e.g., 5HTTLPR serotonin transporter polymorphism) associated with personality traits of propensity to negative affect (e.g., neuroticism) might lead to disrupted sleep via increasing stress-reactivity and learned negative associations, which further increase the likelihood of sleep disruption and the development of chronic insomnia. While the predisposing factors per se may be difficult or impossible to alter, these factors alone may not lead to chronic sleep disturbances.21 If the predisposing factors can be identified, preventive measures may be taken to prevent the development of chronic insomnia in high-risk individuals.

One measure, the Ford Insomnia Response to Stress Test (FIRST), has recently been developed to identify such individuals at high risk for insomnia by assessing their vulnerability to stress-related sleep disturbance.23 High FIRST scores were shown to be associated with elevated sleep disturbance in response to stress due to spending one's first night sleeping in a laboratory as well as a caffeine challenge. Recent sibling and twin studies have also demonstrated that moderate variation in FIRST scores can be attributed to genetic factors.24,25 These results suggest that FIRST scores may reflect the individual trait of sleep reactivity to stress. This trait is therefore proposed to be a predisposing factor for long-term insomnia.

Furthermore, higher sleep vulnerability was found to be associated with arousal- and emotion-related measures.26,27 These studies suggested that cognitive-emotional hyperarousal might modulate an individual's vulnerability to stress-related insomnia. Due to the cross-sectional nature of these studies, however, they do not provide direct evidence that sleep vulnerability is a predisposing factor for longer-term insomnia. A longitudinal study is required to confirm this supposition. As far as we know, only one longitudinal study, published in abstract form, has reported that non-insomnia individuals who scored higher on the FIRST have a greater risk for the subsequent development of insomnia over the course of about 13 months.28 More evidence is needed to confirm this finding.

The present study aims to examine whether sleep reactivity to stress is a predisposing trait for insomnia via a long-term follow-up. Additionally, we selected another variable, dysfunctional sleep belief, as another possible predisposing factor, since it has been found to be higher among insomnia patients. Belief is usually considered to be a relatively stable concept; thus any dysfunctional sleep belief can be presumed to exist early in the course of insomnia. A previous study has also shown an association between sleep vulnerability and dysfunctional sleep belief in young good sleepers.29 In the present study, following up with study subjects six years later, we first examined whether stress-related sleep vulnerability and dysfunctional sleep belief assessed six years previously can predict current insomnia, then examined the role of life stressors in the interaction of these two factors. We hypothesized that: (a) both dysfunctional sleep beliefs and sleep vulnerability to stress can predict insomnia six years later; (b) the predictability with which sleep vulnerability to stress is associated with insomnia is moderated by stress; (c) the predictability of dysfunctional sleep beliefs is not moderated by stress.

METHODS

Subjects

Subjects were recruited from 528 undergraduate university students who participated in a survey study about their sleep in 2006. Among them, 330 agreed to be contacted for follow-up evaluations and signed the consent forms. In 2012, after all participants had graduated from college, 192 were reached by emails and/or phone calls, and 117 (M to F = 51:66; mean age = 25.6 years old) agreed to participate in the follow-up survey.

Procedures

In the 2006 survey, participants completed a packet of questionnaires including the Dysfunctional Beliefs and Attitudes about Sleep Questionnaire, 10-item version (DBAS-10), the FIRST, and the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI). The survey questionnaires were administered during class in several courses by a research assistant who was not associated with the instructors of the courses. In 2012, participants were contacted individually by phone or email, then completed a packet of online questionnaires. The survey questionnaires included the Insomnia Severity Index (ISI) and a modified Life Experiences Survey (LES) for negative life events in the past 3 years in addition to the baseline questionnaires. The participants received a gift coupon of 150NTD to compensate for their participation. The study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee and consent forms were obtained from all participants before their participation.

Measurement

Ford Insomnia Response to Stress Test (FIRST)

The FIRST is a 9-item questionnaire that was designed to quantify the degree of vulnerability to stress-related sleep disturbance as an individual trait. For each item, subjects were asked to rate the likelihood of experiencing sleep disturbance in response to a common stressful situation in daily life on a 4-point Likert scale. The test-retest reliability coefficient was 0.92 with a 2-week interval between test administrations.23 The scale also has good internal consistency as indicated by high Cronbach α coefficients of 0.83 in the original study23 and 0.85 in the present study.

Insomnia Severity Index (ISI)

The ISI is a 7-item Likert-type self-rating scale designed to assess the subjective perception of the severity of insomnia.9,30 The scale contains items that measure the symptoms, associated features, and impact of insomnia, including difficulty falling asleep, difficulty maintaining sleep, early morning awakening, satisfaction with sleep, concerns about insomnia, and functional impact of insomnia. The scale was shown to have small to moderate correlations with polysomnographic indices of sleep quality (r = 0.32–0.55). It was also found to have adequate internal consistency in both the original study (Cronbach α = 0.74)30 and the current study (Cronbach α = 0.86). In order to approach the DSM-IV diagnostic criteria for primary insomnia,31 we have modified the scale, increasing the duration of insomnia symptoms to one month.

Dysfunctional Beliefs and Attitudes about Sleep Scale, 10-item version (DBAS-10)

The original DBAS consists of 30 items concerning beliefs, attitudes, expectations, and attributions about sleep and insomnia.14 Subjects rate their level of agreement on a 10-point scale for each item. Espie and colleagues analyzed data on the DBAS and identified the items that showed significant changes in response to cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia and developed a 10-item version of the DBAS.32 These items comprise 3 factors: (a) immediate negative consequences of insomnia, (b) long-term negative consequences of insomnia, and (c) control over sleep. The scale was shown to have good internal consistency in both the original study (Cronbach α = 0.69)32 and the current study (Cronbach α = 0.78).

Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Inventory (PSQI)

The PSQI contains 19 items that were designed to measure different aspects of sleep quality and sleep disturbances during a one-month period.33 A global sleep quality score, ranging from 0 to 21, can be derived, with higher scores indicating poorer sleep quality. The PSQI has good internal consistency (Cronbach α = 0.83) and test-retest reliability (r = 0.85). A cutoff score of 6 was found to have good sensitivity (89.6%) and fair specificity (86.5%) in identifying poor sleepers.

Modified Life Experiences Survey (LES)

The LES is a self-rating scale developed to assess the major life events that have occurred in the past year and their impacts.34 Subjects are asked to recall the occurrence of different types of life events and to rate their impact on a 7-point Likert scale from Extremely Negative (-3) to Extremely Positive (+3). The original scale contains 57 items. It has been shown to have acceptable test-retest reliability (r's = 0.63 and 0.64 for 2 different tests). For the current study the LES was further modified to assess the major life events in the past 3 years.

Data Analysis

The participants with insomnia at follow-up were initially identified with a cutoff score of 10 on the ISI.30 Logistic regression was then conducted to examine whether the DBAS-10 and the FIRST are predictors for insomnia with baseline PSQI score as the control variable. The interaction of LES with the DBAS-10 and its interaction with the FIRST were then added, according to the method suggested by Baron and Kenny.35

RESULTS

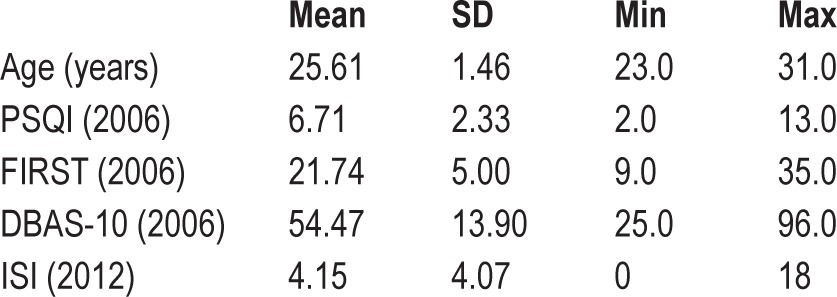

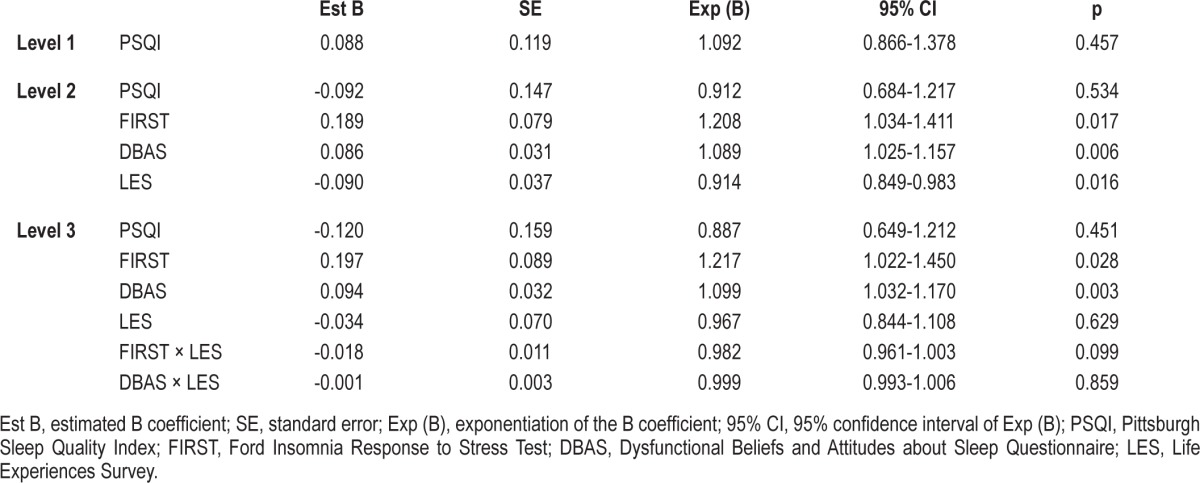

The demographic data on the subjects and means and SDs of the rating scale scores are presented in Table 1. Fourteen participants were found to suffer from insomnia, defined as an ISI > 10 on the follow-up survey. Logistic regression showed that scores on both the FIRST (B = 0.189, p = 0.017) and the DBAS-10 (B = 0.086, p = 0.006) could significantly predict insomnia at follow-up with baseline PSQI as the control (see Table 2). When the interactions of FIRST with LES and that of DBAS-10 with LES were introduced, both FIRST (B = 0.197, p = 0.028) and DBAS-10 (B = 0.094, p = 0.003) remained significant predictors. In terms of the interactions, that of FIRST with LES showed a near-significant trend in predicting insomnia (B = -0.018, p = 0.099) but that of DBAS with LES did not predict insomnia at follow-up (B = -0.001, n.s.; see Table 2). In terms of the odds ratio, a one-point increase on the FIRST was associated with a 21.7% increase in the odds of insomnia (Exp (B) = 1.217), while a one-point increase on the DBAS was associated with a 9.9% increase (Exp (B) = 1.099).

Table 1.

Mean (SD) of the participants' ages and scores on the rating scales.

Table 2.

Results of the logistic regression regarding insomnia prediction at 6-year follow-up.

DISCUSSION

This study aims to explore the contributing roles of vulnerability to stress-related transient sleep disturbance and dysfunctional sleep beliefs as predisposing factors for insomnia, as well as their interaction with major life stressors. The results showed that both factors could predict the occurrence of insomnia six years later, a finding which supports the notion that they are both predisposing factors for insomnia. Although previous studies have shown an association of stress-related sleep vulnerability and maladaptive sleep beliefs with insomnia, most of these studies were conducted with a cross-sectional design and thus their results cannot be used to infer the time sequences of the association. Using a longitudinal design, the current study confirmed the roles of vulnerability to stress-related transient sleep disturbance and dysfunctional sleep beliefs as predisposing factors.

Since stress-related sleep vulnerability as measured by the FIRST reflects sleep reactivity when encountering daily life stressors, it was expected that this trait of vulnerability is associated with the development of insomnia through an interaction with major life stressors. This assumption, however, is not fully supported by our results. The interaction of FIRST score and measures of major life events over the past three years only showed a near-significant trend toward predicting insomnia at follow-up (p = 0.099). Therefore, if there is an interaction effect, its influence is minimal. Although this result is not consistent with our prediction, the observation that the FIRST has a higher direct effect is also of importance. It is possible that individuals with strong trait vulnerability can develop insomnia under only minimal stress. In addition, as illustrated in the 3-P model, while the stressor may serve as a precipitating factor that triggers the onset of insomnia, other factors are required to maintain it or cause it to become chronic. Sleep disturbance may continue even after the precipitating stressful events are dissipated or resolved. Another possible reason why the stress-ors did not show an interaction effect with the individual trait of sleep vulnerability is that the LES does not identify all of the stressors that may be associated with insomnia. In addition to major life stressors such as those that the LES measures, daily hassles can also be triggers of insomnia in highly vulnerable individuals. Previous studies have shown that daily hassles might play an equally, if not more, important role compared to major life stressors for the development of psychophysiological symptoms.36–39 This possibility needs to be confirmed in future studies. Maladaptive sleep beliefs, on the other hand, showed a predisposing effect to insomnia that is independent from the influence of negative life events. This result was expected, as the beliefs are more strongly associated with sleep per se than are daily life events.

In sum, the present study confirms that dysfunctional sleep beliefs and stress-related sleep vulnerability are predisposing factors toward insomnia in a six-year follow-up assessment. Major life stressors, on the other hand, were not found to be a major moderator of the association between these factors and insomnia. These findings have important clinical implications and can advance our understanding of the development of insomnia. First, individuals who are vulnerable to stress-related sleep disturbance can be identified by means of a self-rating scale. Stress management aimed at reducing pre-sleep arousal can then be used to prevent stress-related transient sleep disturbance from becoming a longer-term problem. Second, dysfunctional sleep beliefs can also be assessed to identify individuals with higher risk for insomnia. Psychological education providing correct knowledge and more adaptive attitudes about sleep can then be offered to reduce their risk of developing chronic insomnia.

In light of the significance and clinical implications of these results, some limitations should be kept in mind when interpreting them. First, the response rates were low (35.5% among the subjects who agreed to be contacted in 2006; 60.9% among the subjects who were successfully contacted in 2012), leading to a small sample size (N = 117) at the six-year follow-up. In addition, only 14 of the final participants had insomnia. Therefore, the results should be interpreted with caution. Second, the subjects were originally recruited from a university campus; they represent a young and well-educated population. There may be a limit to how applicable the findings are to other populations. Third, the diagnosis of insomnia was based on the ISI score. Although we have modified the duration over which symptoms are assessed in this test in order to collect data that can be used with the diagnostic criteria of DSM-IV, the modified test still might not be consistent with the clinical diagnosis of insomnia. In addition, no objective measurement of sleep was applied. The possibility of comorbid sleep disorders cannot be ruled out. Fourth, as mentioned above, stressors were measured with regard to reported major life events. Future studies should consider daily hassles as well to further clarify the role of stress and its interactions with potential predisposing factors of insomnia. Last, although this study involved a long-term follow-up, the participants are still relatively young in comparison to the insomnia patients seen in clinical settings. The relative importance of various factors could be different for insomnia patients in different age groups. We are planning to continue following this group of participants to further our understanding of the development of insomnia.

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

This was not an industry supported study. This study is partially supported by the National Science Council of Taiwan (Grant no. NSC98-2410-H-004-023-MY3). The authors have indicated no financial conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ohayon MM. Epidemiology of insomnia: what we know and what we still need to learn. Sleep Med Rev. 2002;6:97–111. doi: 10.1053/smrv.2002.0186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Godet-Cayre V, Pelletier-Fleury N, Le Vaillant M, Dinet J, Massuel MA, Leger D. Insomnia and absenteeism at work. Who pays the cost? Sleep. 2006;29:179–84. doi: 10.1093/sleep/29.2.179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Roth T, Ancoli-Israel S. Daytime consequences and correlates of insomnia in the United States: results of the 1991 National Sleep Foundation Survey. II. Sleep. 1999;22(Suppl 2):S354–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ustinov Y, Lichstein KL, Wal GS, Taylor DJ, Riedel BW, Bush AJ. Association between report of insomnia and daytime functioning. Sleep Med. 2010;11:65–8. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2009.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Riedel BW, Lichstein KL. Insomnia and daytime functioning. Sleep Med Rev. 2000;4:277–98. doi: 10.1053/smrv.1999.0074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Spielman AJ. Assessment of Insomnia. Clin Psychol Rev. 1986;6:11–25. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bonnet MH, Arand DL. Hyperarousal and insomnia. Sleep Med Rev. 1997;1:97–108. doi: 10.1016/s1087-0792(97)90012-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Espie CA, Broomfield NM, MacMahon KM, Macphee LM, Taylor LM. The attention-intention-effort pathway in the development of psychophysiologic insomnia: a theoretical review. Sleep Med Rev. 2006;10:215–45. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2006.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Morin CM. New York, NY: Kluwer Academic/Plenum; 1993. Insomnia: Psychological Assessment and Management. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Perlis ML, Giles DE, Mendelson WB, Bootzin RR, Wyatt JK. Psychophysiological insomnia: the behavioural model and a neurocognitive perspective. J Sleep Res. 1997;6:179–88. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2869.1997.00045.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Harvey AG. A cognitive model of insomnia. Behav Res Ther. 2002;40:869–93. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7967(01)00061-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Carney CE, Edinger JD. Identifying critical beliefs about sleep in primary insomnia. Sleep. 2006;29:342–50. doi: 10.1093/sleep/29.3.342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Edinger JD, Fins AI, Glenn DM, et al. Insomnia and the eye of the beholder: are there clinical markers of objective sleep disturbances among adults with and without insomnia complaints? J Consult Clin Psychol. 2000;68:586–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Morin CM, Stone J, Trinkle D, Mercer J, Remsberg S. Dysfunctional beliefs and attitudes about sleep among older adults with and without insomnia complaints. Psychol Aging. 1993;8:463–7. doi: 10.1037//0882-7974.8.3.463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Harvey AG. Pre-sleep cognitive activity: a comparison of sleep-onset insomniacs and good sleepers. Br J Clin Psychol. 2000;39:275–86. doi: 10.1348/014466500163284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nelson J, Harvey AG. An exploration of pre-sleep cognitive activity in insomnia: imagery and verbal thought. Br J Clin Psychol. 2003;42:271–88. doi: 10.1348/01446650360703384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wicklow A, Espie CA. Intrusive thoughts and their relationship to actigraphic measurement of sleep: towards a cognitive model of insomnia. Behav Res Ther. 2000;38:679–93. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7967(99)00136-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jefferson CD, Drake CL, Scofield HM, et al. Sleep hygiene practices in a population-based sample of insomniacs. Sleep. 2005;28:611–5. doi: 10.1093/sleep/28.5.611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Harvey AG. Sleep hygiene and sleep-onset insomnia. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2000;188:53–5. doi: 10.1097/00005053-200001000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yang CM, Lin SC, Hsu SC, Cheng CP. Maladaptive sleep hygiene practices in good sleepers and patients with insomnia. J Health Psychol. 2010;15:147–55. doi: 10.1177/1359105309346342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Harvey CJ, Gehrman P, Espie CA. Who is predisposed to insomnia: a review of familial aggregation, stress-reactivity, personality and coping style. Sleep Med Rev. 2014;18:217–27. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2013.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Morin CM, Rodrigue S, Ivers H. Role of stress, arousal, and coping skills in primary insomnia. Psychosom Med. 2003;65:259–67. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000030391.09558.a3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Drake C, Richardson G, Roehrs T, Scofield H, Roth T. Vulnerability to stress-related sleep disturbance and hyperarousal. Sleep. 2004;27:285–91. doi: 10.1093/sleep/27.2.285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Drake CL, Scofield H, Roth T. Vulnerability to insomnia: the role of familial aggregation. Sleep Med. 2008;9:297–302. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2007.04.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Drake CL, Friedman NP, Wright KP, Jr., Roth T. Sleep reactivity and insomnia: genetic and environmental influences. Sleep. 2011;34:1179–88. doi: 10.5665/SLEEP.1234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fernandez-Mendoza J, Vela-Bueno A, Vgontzas AN, et al. Cognitive-emotional hyperarousal as a premorbid characteristic of individuals vulnerable to insomnia. Psychosom Med. 2010;72:397–403. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e3181d75319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yang CM, Lin SC, Cheng CP. Transient insomnia versus chronic insomnia: a comparison study of sleep-related psychological/behavioral characteristics. J Clin Psychol. 2013;69:1094–107. doi: 10.1002/jclp.22000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Drake C, Jefferson C, Roehrs T, Richardson G, Roth T. Vulnerability to chronic insomnia: a longitudinal population-based prospective study. Sleep. 2004;27:A270–1. (Abstract Suppl) [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yang CM, Chou CP, Hsiao FC. The association of dysfunctional beliefs about sleep with vulnerability to stress-related sleep disturbance in young adults. Behav Sleep Med. 2011;9:86–91. doi: 10.1080/15402002.2011.557990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bastien CH, Vallieres A, Morin CM. Validation of the Insomnia Severity Index as an outcome measure for insomnia research. Sleep Med. 2001;2:297–307. doi: 10.1016/s1389-9457(00)00065-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.American Psychiatric Association. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 4th ed., text revision. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Espie CA, Inglis SJ, Harvey L, Tessier S. Insomniacs' attributions. psychometric properties of the Dysfunctional Beliefs and Attitudes about Sleep Scale and the Sleep Disturbance Questionnaire. J Psychosom Res. 2000;48:141–8. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3999(99)00090-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Buysse DJ, Reynolds CF, 3rd, Monk TH, Berman SR, Kupfer DJ. The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index: a new instrument for psychiatric practice and research. Psychiatry Res. 1989;28:193–213. doi: 10.1016/0165-1781(89)90047-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sarason IG, Johnson JH, Siegel JM. Assessing the impact of life changes: development of the Life Experiences Survey. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1978;46:932–46. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.46.5.932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Baron RM, Kenny DA. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1986;51:1173–82. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.51.6.1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chamberlain K, Zika S. The minor events approach to stress: support for the use of daily hassles. Br J Psychol. 1990;81:469–81. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8295.1990.tb02373.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fernandez E, Sheffield J. Relative contributions of life events versus daily hassles to the frequency and intensity of headaches. Headache. 1996;36:595–602. doi: 10.1046/j.1526-4610.1996.3610595.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Flannery RB., Jr Major life events and daily hassles in predicting health status: methodological inquiry. J Clin Psychol. 1986;42:485–7. doi: 10.1002/1097-4679(198605)42:3<485::aid-jclp2270420314>3.0.co;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lau GK, Hui WM, Lam SK. Life events and daily hassles in patients with atypical chest pain. Am J Gastroenterol. 1996;91:2157–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]