Abstract

Background

Exercise-induced bronchoconstriction (EIB) describes airway narrowing that occurs in association with exercise. Exercise in hot and cold environments has been reported to increase exercise-induced bronchoconstriction (EIB) in subjects with asthma. However, to our knowledge, the effect of hot and cold environment on pulmonary function and EIB in trained males has not been previously studied. The main goal of this research was to examine the influence of environmental temperature and high intensity interval exercise on pulmonary function in trained teenage males. Also, this study sought to assess the influence of exercise and environmental temperature on EIB.

Materials and Methods

Thirty trained subjects (mean age 16.56±0.89 yrs, all males) underwent high intensity interval exercise testing (22 minutes) by running on a treadmill in hot and cold environments under standardized conditions (10 °C and 45 °C with almost 50% relative humidity in random order in winter and summer). Lung function (flow volume loops) was measured before and 1, 5, 15, 30 and 60 min after the exercise by digital spirometer. Data was analyzed using SPSS software and P < 0.05 was considered significant. The diagnosis of EIB was made by 10% fall in FEV1 post-exercise.

Results

The post-exercise maximal reduction in forced expiratory volume in 1s (FEV1), peak expiratory flow (PEF) and average forced expiratory flow rate over the middle 50% of the FVC (FEF25-75) increased significantly compared to pre-exercise at 10 °C with almost 50% relative humidity (cold air). The obtained values were: -15.93(15min post-exercise), -22.53 (1 min post-exercise) and -18.25%(5min post-exercise). Post-exercise maximal reduction in FEV1, PEF and FEF25-75 increased significantly compared to pre-exercise value at 45 °C with almost 50% relative humidity (hot air). Obtained values were: -10.35 (1 min post-exercise), -9.16 (1 min post-exercise) and -7.39 (5 min post-exercise). Changes in FEV1, PEF and FEF25-75 reduction in cold air was significantly greater than in hot air (P < 0.05). Maximal prevalence of exercise-induced bronchoconstriction (EIB) in cold and hot air was 60% (18 of 30 subjects) and 40% (12 of 30 subjects), respectively.

Conclusion

This study demonstrated that pulmonary function in hot and cold air was influenced by temperature (in the same relative humidity (50%) and also high intensity interval exercise. Prevalence of EIB after high intensity exercise in hot and cold air increased in trained adolescent males; however, these changes in cold air were greater than in hot air among trained adolescent males. Therefore, results of this study suggest that adolescents (although trained) should avoid high intensity (95% maximal heart rate) exercise in winter (extremely low temperature) and summer (extremely high temperature) to prevent EIB.

Keywords: Temperature, Exercise-Induced Bronchoconstriction, Exercise

INTRODUCTION

The term exercise-induced bronchoconstriction (EIB) describes the acute transient airway narrowing that occurs during and most often after exercise in 10 to 50% of elite athletes, depending on the type of sport (1–4). Other terms that have been used to describe the symptoms associated with EIB include: exercise asthma, exercise airway hyper-reactivity, exercise-induced asthma (EIA), skier asthma, skier cough, hockey cough, or cold-induced asthma. All are attempts to characterize the condition of airway narrowing resulting from exercise that is typically accompanied by symptoms of cough, wheeze, chest tightness, dyspnea or excess mucus (5). Etiology of EIB is that breathing relatively dry and cold air during exercise causes the airways to narrow by osmotic and thermal consequences of evaporative water loss from the airway surface (1, 6, 7). In addition, dehydration of the small airways and increased forces exerted on to the airway surface during severe hyperpnoea are thought to be the key factors in determining the occurrence of injury of the airway epithelium. The injury-repair process of the airway epithelium may contribute to the development of the bronchial hyper-responsiveness that is documented in many elite athletes (8). These stimuli most often occur after exercise with the maximum response typically 5-15 minutes post-exercise and generally resolve spontaneously with airway function returning to normal levels within 20 to 60 minutes after exercise (6, 9). The various EIB testing protocols often demand different exercise intensities, which influences the results of EIB tests. Exercise intensity is an important parameter that must be monitored during EIB testing (3). McFadden at el, in 1979 and Strauss at el, in 1978 reported that the incidence and severity of EIB increased when exercise was performed in a cold/dry environment; conversely, incidence and severity reduced after exercise in warm, humid conditions (10, 11). Most of the previous reports have evaluated the effect of breathing cold air through a mouthpiece, while the subjects are exposed to laboratory environmental temperature. Only very few studies have investigated the effect of whole body exposure to cold and hot air on lung function and EIB in trained teenagers (4, 12, 13). Wilber et al. (14) found that 18 to 26% of Olympic winter sport athletes and 50% of cross-country skiers had EIB. Of the 50 elite summer athletes studied, with and without asthma, Holzer et al. (15) found that 50% had EIB. Mannix et al. (16) studied 124 elite figure skaters and tested them on an ice rink during their figure-skating routines. Thirty-five percent had a significant post-exercise drop in their FEV1. The US Olympic Committee reported an 11.2% prevalence of EIB in all athletes who competed in the 1984 summer Olympics. Despite numerous studies that have investigated the prevalence of EIB in athletes, few have investigated the prevalence of EIB in a group of teenagers in spring and winter. Also, few studies compared pulmonary function and EIB at several time points after high intensity exercise in trained teenagers (17, 18).

As far as we know, while a variety of protocols, modes, and methods have been used to provoke EIB, it is best assessed by a standardized exercise test. Lately, it has been stated that an exercise load corresponding to 95% of maximum heart rate (HRmax) is preferable to obtain a high sensitivity (19). Many studies found that any exercise test of sufficient intensity and duration, under ambient dry-air conditions, can be used to elicit a bronchoconstricting response for EIB screening. It is best to employ an exercise challenge that mimics the individual's actual athletic event. Studies documenting the prevalence of EIB and asthma in winter sport athletes have presented a different picture, with a doubled prevalence than that of the summer athletes (14, 16, 20, 21). More recently, survey data reported by Nystad et al. (22) identified a prevalence of 10% among all Norwegian elite athletes (n = 1620) and 6.9% among matched controls (n = 1680). Rundell et al, considering the evidence regarding elite winter sport athletes suggested that the high prevalence of EIB does not support current definitions of classical asthma and is in sharp contrast with that seen in summer athletes (23). Beck et al. have demonstrated that a high percentage of elite athletes have EIB; it is extremely prevalent in winter sports where, depending on the sport surveyed, 20 to 50% of the athletes are affected. Although the typical EIB response involves normal bronchodilation during exercise with bronchoconstriction after exercise, bronchoconstriction can and does occur during exercise and may limit athletic performance (24). Maffulli et al. have found that an increasing number of children take part in organized sport activities, receive intensive training and participate in high level competition from an early age. Although intensive training in children may foster health benefits, many are injured as a result of training, often quite seriously (25). Many researchers stated that the respiratory system can impact the strength and exercise performance in healthy humans and highly trained athletes (26–28) especially, at high temperatures (29, 30).

However, it is not known whether hot and cold environments can influence exercise performance or if there is a relationship between the magnitude of EIB and high intensity exercise in hot and cold environments in trained teenagers. Such knowledge is needed for giving optimal advice to adolescents competing in different sports, especially summer and winter sports. It is also helpful for regular physical training of adolescents in Iran. Many studies describing the prevalence of EIB in elite athletes have used survey data from medical history questionnaires (23). Therefore, the primary objectives of this investigation were: 1) to determine the effects of high-intensity exercise on EIB in trained teenagers, 2) to assess (compare) EIB in hot and cold temperatures after high-intensity exercise in this group, and 3) to determine the prevalence of EIB in cold and hot environments in trained teenagers.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This laboratory study was performed in three separate phases:

First phase: Sample selection

Sixty teenage male subjects who volunteered for participation in this study were initially recruited. All subjects (age 15-17 years) were fit, physically active, healthy and nonsmoker students with no history of cardiovascular or respiratory problems. Subjects were evaluated in the laboratory of Shahid Chamran University of Ahvaz, Iran.

Subjects completed health and physical activity level forms. Then, level of maximal oxygen uptake of all subjects was determined by Astrand-Rhyming test. The standard exercise protocol for this study was submaximal Astrand-Rhyming protocol on Monark cycle. Duration of this test, according to the subjects’ heart rate, was at least 6 minutes but it could take longer than 6 minutes. The initial load at the beginning of the test cycle was 98.1 watt. If in the first 2minutes, the heart rate was less than 60% of the maximum heart rate (HRmax), the load was increased by 49 watt during the next 2 minutes. If the heart rate was 60-70% of the HRmax, the load was increased by 24.5 watt during the next 2 minutes. If the heart rate rose to more than 70% of HRmax, the test continued without load change until the heart rate reached a steady state and the test was terminated.

After determining the level of maximal oxygen uptake in all subjects based on VO2max level, thirty subjects were classified as trained subjects because of having maximal VO2max level.

Final Sample Size: The study population consisted of thirty males (mean age 16.56±0.89 yrs; mean height 172.31±5.18 cm and mean weight 58.95±4.73 kg;) who were physically active soccer players (n=10), or track and field (1500m, 5000m) (n=8) handball (n=3) basketball (n=5) or martial arts (n=4) players. Based on a detailed medical history questionnaire, subjects had no history of cardiopulmonary, metabolic or musculoskeletal disease and were nonsmokers. All subjects signed an informed consent and the local institutional review board approved the study.

Familiarizing subjects with the test process: before conduction of the test, patients were familiarized with the conduction of pulmonary function tests (to measure FVC, each subject blew into the instrument with maximum force after full inspiration; three readings were taken and the best one was recorded. The volume of air that expired in the first second of FVC was defined as FEV1). Spirometry including FEV1, FVC and PEF2575 were done. All maneuvers complied with the general acceptability criteria of The European Respiratory Society (ERS) (31). Predicted lung function values, when used, were according to Quanjer et al. and Zapletal et al. studies (31, 32). Patients were also familiarized with high intensity Astrand test that was performed on a treadmill.

Second phase: Conduction of the test in winter (cold environment)

A. Before testing, subjects were asked not to drink coffee or other caffeine-containing beverages on test days and to refrain from strenuous exercise for 24 h prior to testing.

Controlling relative humidity and temperature:

The high intensity test in cold environment was performed in winter (January 2011). This test was performed in an indoor sports facility (physiology laboratory of Shahid Chamran University) located in Ahvaz city of Islamic Republic of Iran. Before the high intensity testing on a treadmill, pulmonary function test was performed for all subjects as described earlier.

During PFT, three digital indoor/outdoor thermometer/hygrometer (Taylor, USA) placed in three different locations in the laboratory were used to control the temperature and relative humidity. The thermometer features included: 1) Reporting indoor temperature from 14 to 122° F (-10 to 50° C), 2) Reporting indoor humidity levels from 20 to 99% RH, 3) Measuring temperature in 0.1° increments and humidity in 1% increments, and 4) Minimum/maximum temperature and humidity memory recall. Also, VICKS steam humidifier (V105CM, Japan) was used to control the humidity before, during and after exercise. Air conditioner was not used. Mean (± SD) humidity (%) and temperature in cold environment is shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Mean± standard division of relative humidity (%) and temperature in cold environment

| Variable | Pre-test | During test | Post test | Significant Level |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| temperature in cold environment(°C) | 10.45±1.86 | 10.75±1.15 | 11.01±1.96 | NS* |

| Relative humidity in cold environment (%) | 50.51±1.51 | 51.48±1.93 | 49.99±1.87 | NS |

NS: Not Significant

B. Testing:

High intensity exercise protocol: Maximum heart rate is best determined by a progressive, maximal exercise test. We calculated the maximum heart rate (HRmax) of individuals using the formula below:

HRmax = 220-age

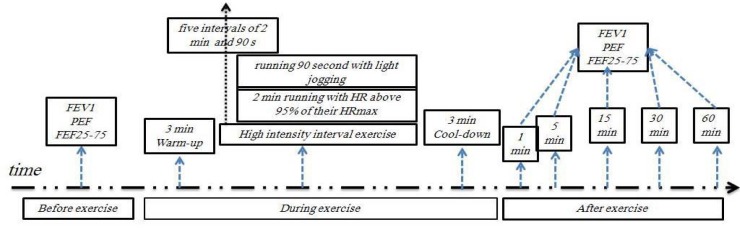

The high-intensity training consisted of a brief 3-min warm-up with light jogging followed by five 2-min intervals of near-maximal running reaching a HR above 95% of their HRmax at the end of the 2-min period (after each 2min interval, subjects ran 90 seconds with light jogging) (6) continued with a brief 3-min cool-down with light jogging with total exercise time per session = 22 min (33) (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

High intensity interval exercise in cold and hot temperatures

C. After testing: subjects performed PFT at 1, 5, 15, 30 and 60 minutes, after performing the high intensity exercise protocol.

All these tests (PFT test before exercise, high intensity exercise protocol, PFT tests after exercise) were carried out in a cold environment. Each subject was evaluated in the Respiratory Pathophysiology Laboratory of the same Department. Children were tested between 9:00 AM to 12:00 PM in a climate-controlled laboratory (with the above-mentioned temperature and relative humidity) (34).

Third phase: testing in summer (hot environment)

A. Before the test: Subjects were asked not to drink coffee or other caffeine-containing beverages on test days and to refrain from strenuous exercise for 24 h prior to testing.

Control of relative humidity and temperature:

High intensity testing in warm environment was performed in summer (July 2011). This test was performed in an indoor sports facility in the physiology laboratory of Shahid Chamran University located in Ahvaz city of Islamic Republic of Iran. Before the high intensity testing on the treadmill, all subjects underwent pulmonary function tests as described earlier.

During PFT, three digital indoor/outdoor thermometer/hygrometer (Taylor, USA) placed in three different locations in the laboratory were used to control the temperature and relative humidity. VICKS steam humidifier (V105CM, Japan) was used to control the humidity before, during and after exercise. However, the heater was not used. Mean (± SD) relative humidity (%) and temperature in the hot environment is shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Mean (± SD) relative humidity (%) and temperature in hot environment

| Variable | Pre-test | During the test | Post test | Significance Level |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Temperature in hot environment(°C) | 45.33±1.50 | 46.12±1.80 | 45.11±1.59 | NS |

| Relative humidity in hot environment (%) | 50.95±1.29 | 49.83±1.83 | 50.44±1.45 | NS |

* NS: Not Significant

B. Testing:

High intensity exercise protocol: Maximum heart rate was best determined by a progressive, maximal exercise test. We calculated the maximum heart rate (HRmax) of individuals using the formula below for warm environment:

HRmax = 220-age

The high-intensity training consisted of a 1) brief 3-min warm-up with light jogging, 2) followed by five intervals of 2 min of near-maximal running reaching a HR above 95% of their HRmax at the end of the 2-min period (after each 2 min interval, subjects ran for 90 second with light jogging), 3) continued by a brief 3-min cool-down with light jogging with total exercise time per session = 22 min (33) (Figure 1).

C. After the test: subjects performed PFT test at 1, 5, 15, 30 and 60 minutes, after performing the high intensity exercise protocol. Each subject was evaluated in the Respiratory Pathophysiology Laboratory of the same Department. Children were tested between 9:00 A.M to 12:00 P.M in a climate-controlled laboratory (temperature and relative humidity mentioned above) (34).

All these tests (PFT test before exercise, high intensity exercise protocol, PFT tests after exercise) were performed in hot temperatures.

Key Points:

Pulmonary function tests were ordered in participants without symptoms of cough, dyspnea, wheezing, hypoxemia, or bronchodilator use. None of the participants had any symptoms.

Warm-up time was equal in the two tests. Thus, warm up results were not interpreted in this study.

Statistical analysis

Demographics were presented as mean values and standard deviation (SD). Differences between the two tests were analyzed by Student's paired t-test when ensuring normal distribution. The bronchoconstrictor response following exercise was measured after both tests, FEV1 was measured at least twice, at 1, 5, 15, 30, and 60 minutes after exercise and the lowest FEV1 recorded over this period was used to calculate the maximal percentage fall from baseline by the following equation:

% fall in FEV1= (pre-exercise FEV1- lowest FEV1 post-exercise)/pre-exercise FEV1×100

Subjects who experienced a 15% fall in FEV1 were considered positive for EIB (34). All tests were two-tailed with a significance level of 5%. Statistical analyses were performed with Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) version 19.0 software.

RESULTS

Demographic data and baseline lung function are presented in Table 3. Baseline lung function (FEV1, FEF25-75 and PEF) did not differ significantly in the two test seasons. VO2max in the cold and hot environment was 53.63±1.58 and 51.66±3.54, respectively; however, VO2max did not change significantly during exercise in hot environment as compared with exercise in cold environment.

Table 3.

Demographic data and baseline lung function (liter) before exercise in a standardized hot environment (45°C and 50% relative humidity) and in a standardized cold environment (10°C and 50% relative humidity)

| Variables | 10°C and 50% relative humidity | 45°C and 50% relative humidity | Level of significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| FEV1(lit) | 3.37±0.49 | 3.48±0.60 | NS * |

| FEF25-75(lit) | 3.76±0.67 | 3.89±0.77 | NS |

| PEF(lit) | 5.77±0.44 | 5.78±0.54 | NS |

| Height(cm) | 172.31±5.18 | 172.31±5.39 | NS |

| Weight(cm) | 58.95±4.73 | 58.30±4.13 | NS |

| Age(year) | 16.56±0.89 | 16.56±0.89 | NS |

| Maximal oxygen consumption(ml/kg.min) | 53.63±1.58 | 51.66±3.54 | NS |

NS: Not Significance

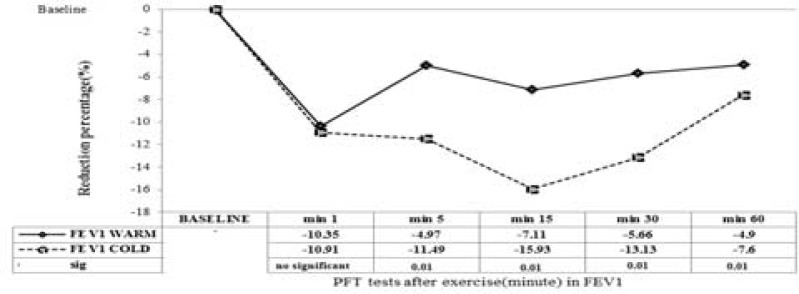

Drop in FEV1 increased significantly after exercise in the cold environment as compared with hot environment. Maximum reduction in FEV1 as percent of baseline lung function after exercise in the cold and hot environments was -15.93% (15 min after exercise) vs. -10.35(1 min after exercise) after high intensity exercise (Table 4). Reduction percentage in FEV1 was higher at all tested time points (except for 1 min) after exercise in the cold environment as compared to exercise in hot environment (Table 4). In addition, reduction percentage in FEV1 at 5, 15, 30 and 60 min was significantly higher (p = 0.01 for all time points except for 1 min) for exercise in the cold environment as compared to exercise in hot environment. In addition, Number and percentage of subjects who developed EIB were significantly higher at all time points after exercise in cold environment as compared to exercise in hot environment (10% fall in FEV1) (Table 4 and Figure 2).

Table 4.

Prevalence of exercise-induced bronchoconstriction (%) based on 10% fall in FEV1, percentage and number of affected subjects after activity in comparison with before activity at 10°C and 45°C with 50% relative humidity and calculation of the reduction percentage by subtraction of the post test mean from the pretest mean

| Post tests | Variables | 10°C and 50% Relative humidity | Relative humidity | Level of significance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre test-post test 1 min | Reduction percentage mean | −10.91 | −10.35 | Not Significant |

| Number(subjects) | 16 | 12 | 0.04 | |

| EIB (%) | 53 | 40 | 0.01 | |

| Pre test-post test 5 min | Reduction percentage mean | −11.49 | −4.97 | 0.01 |

| Number(subjects) | 14 | 9 | 0.02 | |

| EIB (%) | 46 | 30 | 0.01 | |

| Pre test-post test 15 min | Reduction percentage mean | −15.93 | −7.11 | 0.01 |

| Number(subjects) | 18 | 3 | 0.01 | |

| EIB (%) | 60 | 10 | 0.01 | |

| Pre test-post test 30 min | Reduction percentage mean | −13.13 | −5.66 | 0.01 |

| Number(subjects) | 15 | 11 | 0.03 | |

| EIB (%) | 50 | 36 | 0.01 | |

| Pre test-post test 60 min | Reduction percentage mean | −7.60 | −4.90 | 0.01 |

| Number(subjects) | 6 | 3 | 0.04 | |

| EIB (%) | 20 | 10 | 0.01 |

Figure 2.

Reduction percentage of lung function (FEV1) before and 1, 5, 15, 30 and 60 min after exercise in high temperature ( ) and in the cold environment (----). Results are given with a significance level of 5%

) and in the cold environment (----). Results are given with a significance level of 5%

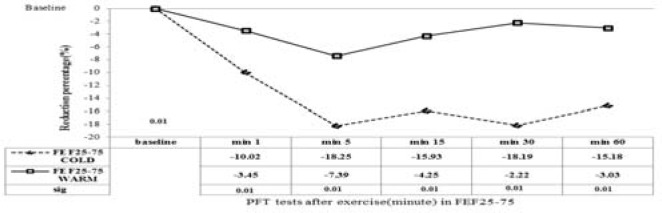

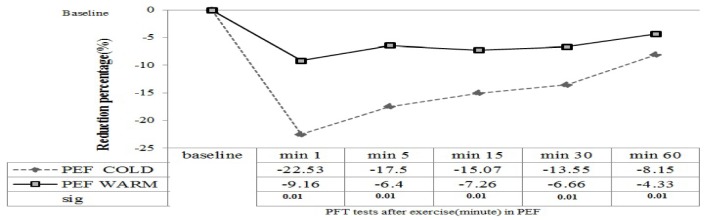

Reduction in FEF25-75 after exercise in the hot environment was noted at all time points; maximal reduction in cold and hot environments was -18.25% (at 5 min after exercise) vs. -7.39%, respectively (at 5 min after exercise) (Figure 3). Also, maximal reduction in PEF (after exercise) in cold and hot environments was -22. 53% (at 1 min after exercise) and -9.16%, respectively (at 1 min after exercise), (Figure 4).

Figure 3.

Reduction percentage of lung function (FEF25-75) before and 1, 5, 15, 30 and 60 min after exercise in high temperature ( ) and in the cold environment (----). Results are given with a significance level of 5%.

) and in the cold environment (----). Results are given with a significance level of 5%.

Figure 4.

Reduction percentage of lung function (PEF) before and 1, 5, 15, 30 and 60 min after exercise in high temperature ( ) and in the cold environment (----). Results are given with a significance level of 5%.

) and in the cold environment (----). Results are given with a significance level of 5%.

Table 4 showed the magnitude of EIB after high intensity interval exercise in cold and hot temperatures. Maximal prevalence of EIB at 10°C and 50% relative humidity was 60% (18 of 30 subjects), after inhaled cold air in high intensity interval exercise. However, when subjects inhaled warm air (45°C and 50% relative humidity) maximal prevalence of EIB was lower than in other conditions (inhaling cold air). Maximal prevalence of EIB in hot temperatures was 40% (12 of 30 subjects).

Table 5 showed the magnitude of EIB after high intensity interval exercise in cold and hot temperatures based on type of sport. Maximal prevalence of EIB at 10°C and 50% relative humidity was seen in endurance running after inhaling cold air in high intensity interval exercise. However, when subjects inhaled warm air (45°C and 50% relative humidity) maximal Prevalence of EIB was lower compared to inhaling cold air. Maximal prevalence of EIB in hot temperature was seen in endurance running.

Table 5.

Prevalence of exercise-induced bronchoconstriction based on the type of sport (10% fall in FEV1).

| Post tests | Variables | 10°C and 50% Relative humidity Number(subjects) | 45°C and 50% relative humidity Number(subjects) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pre test-post test 1 min | Soccer(8 subjects) | 4 | 3 |

| Volleyball (7 subjects) | 3 | 2 | |

| Martial arts(Taekwondo, Karate) (6 subjects) | 2 | 1 | |

| Wrestling(3 subjects) | 1 | 1 | |

| Endurance running(6 subjects) | 6 | 5 | |

| Pre test-post test 5 min | Soccer(8 subjects) | 3 | 2 |

| Volleyball (7 subjects) | 3 | 2 | |

| Martial arts(Taekwondo, Karate) (6 subjects) | 1 | 0 | |

| Wrestling(3 subjects) | 1 | 0 | |

| Endurance running(6 subjects) | 6 | 5 | |

| Pre test-post test 15 min | Soccer(8 subjects) | 5 | 1 |

| Volleyball (7 subjects) | 4 | 0 | |

| Martial arts(Taekwondo, Karate) (6 subjects) | 2 | 0 | |

| Wrestling(3 subjects) | 1 | 0 | |

| Endurance running(6 subjects) | 6 | 2 | |

| Pre test-post test 30 min | Soccer(football)(8 subjects) | 4 | 3 |

| Volleyball (7 subjects) | 3 | 2 | |

| Martial arts(Taekwondo, Karate) (6 subjects) | 1 | 0 | |

| Wrestling(3 subjects) | 1 | 1 | |

| Endurance running(6 subjects) | 6 | 5 | |

| Pre test-post test 60 min | Soccer(8 subjects) | 1 | 1 |

| Volleyball (7 subjects) | 1 | 0 | |

| Martial arts(Taekwondo, Karate) (6 subjects) | 0 | 0 | |

| Wrestling(3 subjects) | 0 | 0 | |

| Endurance running(6 subjects) | 4 | 2 |

DISCUSSION

The aim of this study was to determine the influence of high intensity interval exercise on a treadmill in two environments (cold and hot conditions) on the prevalence of EIB among adolescent athletes. The present study demonstrated that high intensity interval exercise in low temperature causes a higher prevalence of EIB in trained adolescent males. However, high intensity exercise causes exercise-induced bronchoconstriction (EIB) in trained adolescent males in hot and cold temperatures. Our obtained results showed the reduction of PEF and FEF25-75 post-test. The results of the present study demonstrated that the acute EIB response to high intensity interval exercise in adolescent athletes was influenced by changes in temperature (regardless of relative humidity). Moreover, our obtained data show that the pulmonary function (airways) response to high interval exercise in cold and hot temperatures in adolescent athletes is different than that in subjects exercising at normal temperatures regardless of relative humidity. However, it seems that endurance exercise causes the highest EIB compared to other sports (sprint and resistance sports) (Table 5).

Concerning FEV1, we found significant differences in FEV1 in adolescent athletes before and after exercise: in the LT (low temperature) environment, exercise resulted in a 15.93% maximal fall in FEV1. In the HT (high temperature) FEV1 maximal fall was 10.35% (p < 0.05). Comparing both environments, a higher FEV1 fall was observed for adolescent athletes in LT than in HT after exercise. Ana Silva and colleagues (35) reported similar results in their study, observing that a 15 minute progressive exercise trial on a calibrated cycloergometer, at 3 different workloads (30, 60, 120 watts) of 5 minutes each, followed by 5 minutes of recovery, breathing hot and humid air induced significant differences in FEV1 in asthmatics adolescents before and after exercise. In the low temperature environment, exercise resulted in a 9.4% fall of FEV1 and in the high environment FEV1 fell by 4.8%. In contrast, they did not find statistical differences in FEV1 in healthy subjects before and after exercise in both environments. They also found a higher FEV1 fall for asthmatics in low temperature than in high temperature after exercise.

It is also important to highlight that the majority of experimental designs described in the literature normally used higher temperatures and relative humidity ranges than those employed in our study. Mannix and colleagues (16) found a post exercise fall in FEV1 by 10% in 43 of 124 (35%) highly trained figure skaters, and a fall of 15% in 19 of them, indicating a significantly higher prevalence than what is usually reported for the general population. Our findings are also supported by Stensrud et al, who (36) demonstrated that after the exercise forced expiratory volume in 1 s (FEV1) increased significantly from 24% (5, 22) to 31% (26, 37), after exercise testing by running on a treadmill in a climate chamber with a standardized cold environment. They also found that maximum reduction in FEV1 increased significantly after exercise in the cold environment as compared with regular, indoor conditions. Wilson and colleagues (38) showed that there was a significant % fall in FEV1 after two 7 min treadmill exercise challenges at 80% maximum heart rate, separated by a 30 min rest both for warm humid and thermo-neutral conditions. However, the results of Wilson and colleagues study supported our findings, but there are differences in temperature, relative humidity and intensity exercise between the two investigations. Also, Therminarias et al. (39) studied eight well-trained males performing two incremental exercise tests until exhaustion, followed by 5 min of recovery in temperate (22°C) and cold (-10°C) environments. They found that at -10°C, a significant decrease in FEV1 was observed after exercise but no such effect was observed at 22°C. Therminarias et al. confirmed that considerable hyperpnoea in cold air causes a detectable airway obstruction.

Our data concerning PEF and FEF25-75 demonstrate significant differences in PEF and FEF25-75 in adolescent athletes before and after exercise: in the LT (low temperature) environment, exercise resulted in a 22.53% vs. 18.25% maximal fall in PEF vs. FEF25-75, respectively. In the HT (high temperature) PEF and. FEF25-75 experienced a maximal fall of 9.16% and 7.39%, respectively (p < 0.05). Comparing both environments, a higher PEF fall was observed in adolescent athletes in LT than in HT after exercise (Figure 3) (p < 0.05). In addition, comparing both environments, a higher FEF25-75 fall was observed in adolescent athletes in LT than in HT after exercise (Figure 4) (p < 0.05). These results are in accord with those of Kallings and colleagues (40), who observed that a 6-minute exercise of breathing hot and humid air induced a lower PEF fall (6.1±2%) than the same exercise while breathing cold and dry air (19.4±6% PEF fall). Another study also showed that well-trained males performed two incremental exercise tests until exhaustion, followed by 5 min of recovery in temperate (22°C) and cold (-10°C) environments. They concluded that at -10°C, a significant decrease in FEF75 was observed after exercise but not at 22°C (39). Horton et al. (41) demonstrated that when breathing ambient air, exposure to cold resulted in a significant decrease in FEVl and FEF25-75% to an average of 75 percent and 64 percent of the precooling baseline values, respectively.

In our investigation a 10% reduction in FEV1 after exercise challenge was considered as the spirometric criterion. Maximal prevalence of EIB in cold temperature was approximately 60% in our study after high intensity interval exercise. However, maximal prevalence in warm temperature was approximately 40% after high intensity interval exercise. Various studies have been conducted to determine the prevalence of EIB in athletes and non athletes with controversial results, probably because of methodological considerations such as exercise protocols, air temperature and humidity, subjects’ age and many other factors (42). Sallaoui et al. (42) reported that after 8-min of running at 80–85% HRmax, post exercise spirometry revealed EIB in 9.8% of athletes including 13% of the elite athletes. The main difference between our study and Sallaoui's was in defining EIB. In Sallaoui's study EIB was defined as a decrease of at least 15% in forced expiratory volume in one second (FEV1), but in our study EIB was defined as a decrease of at least 10% in FEV1. Also, Ogston and Butcher (43) established EIB with spirometry in 28 of 99 cross-country skiers after a 15-minute cross-country skiing exercise. Another study performed in Iran showed that according to spirometric findings, about 20% of participants who were football players had EIB. However, temperature was maintained at 24-27 °C and humidity was controlled between 26-30%. Thus, our study is different from the mentioned study in terms of air temperature, humidity, and process of diagnosis (in the mentioned study diagnosis of EIB was based on decrease in FEV1 by at least 15% or in PEFR or FEF25-75 by at least 25% after the exercise challenge) (44). Mannix et al. (16) found EIB prevalence to be 35% in elite ice-skaters. EIB was found in 23% of the athletes taking part in the Winter Olympic Games 1998. Ucok and colleagues (45) detected EIB in 7of 20 athletes and in 1 of 19 sedentary. They found that the prevalence of EIB was higher even if it is established in room temperature when training for the sports like long distance running which is not a cold weather sport (45). Provost-Craig et al. (20) demonstrated the prevalence of EIB to be 30% in 100 ice-skaters. Rundell and colleagues (46) diagnosed EIB in 30% of the athletes exposed to cold and dry weather exercise (14). The prevalence of EIB in our study (60%) was higher for cold weather sports. Provost-Craig and colleagues (20) documented exercise-induced bronchoconstriction after a 4-min skating program in 30 of 100 competitive skaters. Larsson and colleagues (47) found that 33 of 42 elite cross-country skiers (79%) had abnormal respiratory symptoms. Helenius et al. (44) established that exercise in subzero temperature had almost no effect on pulmonary function of elite runners which is not in agreement with our study. Many researchers have reported EIB in cold air, but only a few have assessed its prevalence in warm air (14, 44, 45).

It is known that cold, dry air increases EIB, and humid air reduces EIB in subjects with asthma. However, few studies exist regarding the effect of different climatic conditions on exercise capacity in subjects suffering from EIB, with conflicting results (48). According to Nieman et al, (49) many elite athletes report significant bouts with upper respiratory tract infections (URTI) interfering with their ability to compete and train. During the winter and summer Olympic Games, it has been regularly reported by clinicians that URTI are the most frequent and irksome health problems that athletes experience. They also found a relationship between exercise workload with immune function and infection risk. This study demonstrates that exercise with very high workload influences upper respiratory tract infections. Thus, decrease in pulmonary function in cold and hot temperatures observed in our study may induce immune reaction and increase the risk of infection as mentioned by Nieman. In another study it has been reported that the exercise-induced epithelial injury is a transient event; however, repair of denuded airway epithelial areas occurs very quickly and involves basal cells and Clara cells. Thus, the fact that neutrophil count is increased in sputum samples of elite athletes at rest and following a single bout of heavy exercise shows that in heavy exercise the epithelium requires the assistance of neutrophils, for repair of denuded airway epithelial areas (8). Langdeau and colleagues (50) strongly suggest that exercise or hyperventilation per se may not be the main mechanism involved in the development of pulmonary disorder in athletes and environmental factors may also influence the type and content of the inhaled air. They also suggest that duration of involvement for athletes in their current sport seemed to be a contributing factor to pulmonary abnormality, whereas the level of competition was not, as significant differences were observed between all parameters when athletes were divided by competitive caliber. Another study suggested that, although the typical EIB response involves normal bronchodilation during exercise with bronchoconstriction after exercise, bronchoconstriction can and does occur during exercise and may limit athletic performance (24). Consequently, the temperature may affect the severity of the EIB. Rundell and Sue-Chu (37) showed that, when exercise challenge was performed at the same RH (40%) but at temperatures of 20.2°C and -18°C, the severity of the EIB was significantly greater after exercise at -18 °C than at 20.2°C, suggesting the additive effect of cold air (36, 41). However, we used a 15% decrease in FEV1 as the cut-off criterion for a positive test. Thus, it may be prudent to assess individuals who have symptoms only under cold conditions with an exercise challenge with cold air inhalation if the challenge test with warm air with an absolute humidity <10 mg H2O per L is negative. In contrast, no additive effect was observed by Evans (51), who reported that the severity of EIB was related to water content and not the temperature of inhaled air during exercise. But also as mentioned above, addition of high intensity interval exercise to temperature may cause higher prevalence of EIB in teenage athletes. These results confirmed those in elite athletes, particularly those training in a cold environment and exercise-induced cough is a common complaint (52, 53). It has been observed that certain activities, e.g. running, produce greater airflow limitation than other activities, e.g. swimming (54). Also, most studies show increased airway responsiveness by using exercise as the provoking stimulus. The possibility that this reflects only a normal response to a supraphysiologic stimulus has been contradicted by recent reports showing that this increased airway response could also occur in athletes after using other stimuli such as methacholine (55). On the other hand, high-intensity exercise could induce or promote airway inflammation, either from hyperventilation or from an increased airway exposure to inhaled allergens or pollutants (56). Other factors may also be involved in the development of pulmonary disorder such as a predominance of the parasympathetic nervous system over the sympathetic one, a phenomenon that has been reported in athletes (57). Parasympathetic activity may act as modulator of airway responsiveness, but the increased prevalence of airway hyperresponsiveness in our athlete population may be related to the type and possibly the content of inhaled air during training (57).

Thereupon, our results are in agreement with previous experiments in which non-atopic subjects responded to extensive airway cooling by developing airway obstruction (58, 59). According to some authors, airway cooling has been proposed as the key stimulus initiating events that lead to an EIB (60) acting on thermo sensitive receptors, and a parasympathetic reflex response, or directly on smooth muscle. However, according to other authors, evaporative water loss and changes in osmotic environment lead to EIB. They hypothesize that changes in airway tonicity may trigger mediator release from osmosensitive cells causing inflammation and smooth-muscle constriction (61, 49). In addition, we in our data have shown that prevalence of EIB was higher than documented in other studies (16, 20, 62, 63). This result is the consequence of physical exertion, particularly when it is intense and prolonged, causing significant stress to the respiratory system, from the associated hyperventilation and increased airway exposure to contaminants of inhaled air (64, 65). Recent studies have generally shown a higher prevalence of airway hyperresponsiveness in athletes, particularly those performing winter sports such as cross-country skiing, ice skating, or hockey than in the general population (20, 66). More and more reports suggest that many athletes have a physician-made diagnosis of asthma or show an abnormal fall in expiratory flows after exercise challenge tests (67, 68). Thus, both high intensity interval exercise and low/high temperature (regardless of relative humidity) secondary to higher EIB than other study. However, in our investigation, EIB in high temperature was lower than in cold air. Based on the above mentioned literature, results show that high intensity interval exercise in low temperature causes higher EIB than in high temperature in adolescent athletes. These results confirm that muscular exercise in a cold environment requires both warming and humidification of large amounts of inspired air, resulting in a loss of heat and water from the respiratory tract. While these losses are known to induce airway obstruction in subjects with bronchial hyperresponsiveness, their effects are not well defined in normal nonatopic subjects. According to some authors, normal subjects do not develop measurable obstruction in response to airway cooling (60, 61), whereas other authors claim that they respond by developing measurable obstruction when the stimulus is sufficiently great (58, 59). The pathophysiology of EIB in athletes has not been well understood (4). Under these conditions, the origin and mechanisms involved in the development of bronchial obstruction are still under debate (69, 70). Thus, further investigations are required in this respect.

Key points

The primary stimulus for EIB is water loss from the airway surface liquid with subsequent release of bronchoconstricting mediators or inflammation in upper respiratory system due to high intensity interval challenge.

The time interval (between phases of running on a treadmill) can be a very effective stimulus for EIB.

The cold air laboratory challenge is an effective test for EIB.

The high temperature laboratory challenge is an effective test for EIB.

The high intensity interval exercise in cold air causes a higher EIB prevalence.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by Shahid Chamran University. We are grateful to our understudy subjects for their time and enthusiastic participation. We thank Dr. Mohsen Ghanbarzadeh for teaching us procedures for high intensity interval exercise challenge and also for conducting all the phases of testing and Ahmad Ghotbi, Ghasem Abdolrahimi, Ali Taghavi Orveh, Hamid Asle Mohammadizadeh and Dr. Abdolhamid Habibi (as supervisor) for their sincere cooperation.

REFERENCES

- 1.Parsons JP, Mastronarde JG. Exercise-induced bronchoconstriction in athletes. Chest. 2005;128(6):3966–74. doi: 10.1378/chest.128.6.3966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cerny F, Rundell K. 2010. Physical Activity, Asthma, and Exercise-Induced Bronchoconstriction; pp. 1–10. Series 11., Research Digest. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dal U, Erdogan T, Helvaci I. A workload equation for a bicycle ergometer is not sufficient to elicit exercise-induced bronchoconstriction in athletes. International SportMed Journal. 2010;11(1):226–34. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Messan F, Marqueste T, Akplogan B, Decherchi P, Grelot L. Exercise-Induced Bronchospasm Diagnosis in Sportsmen and Sedentary. ISRN Pulmonology. 2012:1–7. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Anderson SD, Holzer K. Exercise-induced asthma: is it the right diagnosis in elite athletes? J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2000;1061(3):419–28. doi: 10.1067/mai.2000.108914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rundell KW, Jenkinson DM. Exercise-induced bronchospasm in the elite athlete. Sports Med. 2002;32(9):583–600. doi: 10.2165/00007256-200232090-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Carlsen KH, Engh G, Mørk M, Schrøder E. Cold air inhalation and exercise-induced bronchoconstriction in relationship to metacholine bronchial responsiveness: different patterns in asthmatic children and children with other chronic lung diseases. Respir Med. 1998;92(2):308–15. doi: 10.1016/s0954-6111(98)90114-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kippelen P, Anderson SD. Airway injury during high-level exercise. Br J Sports Med. 2012;46(6):385–90. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2011-090819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McFadden ER, Jr, Lenner KA, Strohl KP. Postexertional airway rewarming and thermally induced asthma. New insights into pathophysiology and possible pathogenesis. J Clin Invest. 1986;78(1):18–25. doi: 10.1172/JCI112549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McFadden ER, Jr, Ingram RH. Exercise-induced asthma: Observations on the initiating stimulus. N Engl J Med. 1979;301(14):763–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197910043011406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Strauss RH, McFadden ER, Jr, Ingram RH, Jr, Deal EC, Jr, Jaeger JJ. Influence of heat and humidity on the airway obstruction induced by exercise in asthma. J Clin Invest. 1978;61(2):433–40. doi: 10.1172/JCI108954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Koskela H, Tukiainen H, Kononoff A, Pekkarinen H. Effect of whole-body exposure to cold and wind on lung function in asthmatic patients. Chest. 1994;105(6):1728–31. doi: 10.1378/chest.105.6.1728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Eschenbacher WL, Moore TB, Lorenzen TJ, Weg JG, Gross KB. Pulmonary responses of asthmatic and normal subjects to different temperature and humidity conditions in an environmental chamber. Lung. 1992;170(1):51–62. doi: 10.1007/BF00164755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wilber RL, Rundell KW, Szmedra L, Jenkinson DM, Im J, Drake SD. Incidence of exercise-induced bronchospasm in Olympic winter sport athletes. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2000;32(4):732–7. doi: 10.1097/00005768-200004000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Holzer K, Anderson SD, Douglass J. Exercise in elite summer athletes: Challenges for diagnosis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2002;110(3):374–80. doi: 10.1067/mai.2002.127784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mannix ET, Farber MO, Palange P, Galassetti P, Manfredi F. Exercise-induced asthma in figure skaters. Chest. 1996;109(2):312–5. doi: 10.1378/chest.109.2.312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Voy RO. The U.S. Olympic Committee experience with exercise-induced bronchospasm, 1984. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1986;18(3):328–30. doi: 10.1249/00005768-198606000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rupp NT, Guill MF, Brudno DS. Unrecognized exercise-induced bronchospasm in adolescent athletes. Am J Dis Child. 1992;146(8):941–4. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1992.02160200063028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Carlsen KH, Engh G, Mørk M. Exercise-induced bronchoconstriction depends on exercise load. Respir Med. 2000;94(8):750–5. doi: 10.1053/rmed.2000.0809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Provost-Craig MA, Arbour KS, Sestili DC, Chabalko JJ, Ekinci E. The incidence of exercise-induced bronchospasm in competitive figure skaters. J Asthma. 1996;33(1):67–71. doi: 10.3109/02770909609077764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rundell KW, Wilber RL, Szmedra L, Jenkinson DM, Mayers LB, Im J. Exercise-induced asthma screening of elite athletes: field versus laboratory exercise challenge. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2000;32(2):309–16. doi: 10.1097/00005768-200002000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nystad W, Harris J, Borgen JS. Asthma and wheezing among Norwegian elite athletes. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2000;32(2):266–70. doi: 10.1097/00005768-200002000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rundell KW, Jenkinson DM. Exercise-induced bronchospasm in the elite athlete. Sports Med. 2002;32(9):583–600. doi: 10.2165/00007256-200232090-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Beck KC, Offord KP, Scanlon PD. Bronchoconstriction occurring during exercise in asthmatic subjects. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1994;149(2 Pt 1):352–7. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.149.2.8306029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Maffulli N, Pintore E. Intensive training in young athletes. Br J Sports Med. 1990;24(4):237–9. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.24.4.237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gething AD, Passfield L, Davies B. The effects of different inspiratory muscle training intensities on exercising heart rate and perceived exertion. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2004;92(1-2):50–5. doi: 10.1007/s00421-004-1044-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nicks C, Farley R, Fuller D, Morgan D, Caputo J. The effect of respiratory muscle training on performance, dyspnea, and respiratory muscle fatigue in intermittent sprint athletes. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise. 2006;38(5):381. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stuessi C, Spengler CM, Knöpfli-Lenzin C, Markov G, Boutellier U. Respiratory muscle endurance training in humans increases cycling endurance without affecting blood gas concentrations. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2001;84(6):582–6. doi: 10.1007/s004210100408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Harms CA, Wetter TJ, St Croix CM, Pegelow DF, Dempsey JA. Effects of respiratory muscle work on exercise performance. J Appl Physiol. 2000;89(1):131–8. doi: 10.1152/jappl.2000.89.1.131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wells GD, Plyley M, Thomas S, Goodman L, Duffin J. Effects of concurrent inspiratory and expiratory muscle training on respiratory and exercise performance in competitive swimmers. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2005;94(5-6):527–40. doi: 10.1007/s00421-005-1375-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Quanjer PH, Tammeling GJ, Cotes JE, Pedersen OF, Peslin R, Yernault JC. Lung volumes and forced ventilatory flows. Report Working Party Standardization of Lung Function Tests, European Community for Steel and Coal. Official Statement of the European Respiratory Society. Eur Respir J Suppl. 1993;16:5–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zapletal A, Samanek M, Paul T. Lung function in children and adolescents. Methods, reference values. Prog Respir Res. 1987;22:113–218. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Astrand I, Astrand PO, Hallbäck I, Kilbom A. Reduction in maximal oxygen uptake with age. J Appl Physiol. 1973;35(5):649–54. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1973.35.5.649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tancredi G, Quattrucci S, Scalercio F, De Castro G, Zicari AM, Bonci E, et al. 3-min step test and treadmill exercise for evaluating exercise-induced asthma. Eur Respir J. 2004;23(4):569–74. doi: 10.1183/09031936.04.00039704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Silva A, Appell HJ, Duarte JA. Influence of environmental temperature and humidity on the acute ventilatory response to exercise in asthmatic adolescents. Arch Exerc Health Dis. 2011;2(1):69–75. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Stensrud T, Berntsen S, Carlsen KH. Exercise capacity and exercise-induced bronchoconstriction (EIB) in a cold environment. Respir Med. 2007;101(7):1529–36. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2006.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rundell KW, Sue-Chu M. Field and laboratory exercise challenges for identifying exercise-induced bronchoconstriction. Breathe. 2010;7(1):34–42. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wilson BA, Bar-Or O, O'Byrne PM. The effects of indomethacin on refractoriness following exercise both with and without a bronchoconstrictor response. Eur Respir J. 1994;7(12):2174–8. doi: 10.1183/09031936.94.07122174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Therminarias A, Oddou MF, Favre-Juvin A, Flore P, Delaire M. Bronchial obstruction and exhaled nitric oxide response during exercise in cold air. Eur Respir J. 1998;12(5):1040–5. doi: 10.1183/09031936.98.12051040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kallings LV, Emtner M, Bäcklund L. Exercise-Induced Bronchoconstriction in Adults with Asthma: Comparison between running and cycling and between cycling at different air conditions. Upsala Journal of Medical Sciences. 1999;104(3):191–8. doi: 10.3109/03009739909178962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Horton DJ, Chen WY. Effects of breathing warm humidified air on bronchoconstriction induced by body cooling and by inhalation of methacholine. Chest. 1979;75(1):24–8. doi: 10.1378/chest.75.1.24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sallaoui R, Chamari K, Mossa A, Tabka Z, Chtara M, Feki Y, et al. Exercise-induced bronchoconstriction and atopy in Tunisian athletes. BMC Pulm Med. 2009;9:8. doi: 10.1186/1471-2466-9-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ogston J, Butcher JD. A sport-specific protocol for diagnosing exercise-induced asthma in cross-country skiers. Clin J Sport Med. 2002;12(5):291–5. doi: 10.1097/00042752-200209000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Helenius IJ, Tikkanen HO, Haahtela T. Exercise-induced bronchospasm at low temperature in elite runners. Thorax. 1996;51(6):628–9. doi: 10.1136/thx.51.6.628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Uçok K, Dane S, Gökbel H, Akar S. Prevalence of exercise-induced bronchospasm in long distance runners trained in cold weather. Lung. 2004;182(5):265–70. doi: 10.1007/s00408-004-2503-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rundell KW, Spiering BA. Inspiratory stridor in elite athletes. Chest. 2003;123(2):468–74. doi: 10.1378/chest.123.2.468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Larsson K, Ohlsén P, Larsson L, Malmberg P, Rydström PO, Ulriksen H. High prevalence of asthma in cross country skiers. BMJ. 1993;307(6915):1326–9. doi: 10.1136/bmj.307.6915.1326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Stensrud T. Obtaining additional information by using exercise testing in the laboratory in the diagnosis of asthma. Breathe. 2010;7(1):44–51. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Nieman DC, Pedersen BK. Nutrition and Exercise Immunology. Boca Raton (FL): CRC Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Langdeau JB, Turcotte H, Bowie DM, Jobin J, Desgagné P, Boulet LP. Airway hyperresponsiveness in elite athletes. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2000;161(5):1479–84. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.161.5.9909008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Evans TM, Rundell KW, Beck KC, Levine AM, Baumann JM. Cold air inhalation does not affect the severity of EIB after exercise or eucapnic voluntary hyperventilation. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2005;37(4):544–9. doi: 10.1249/01.mss.0000158186.32450.ec. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Heir T, Oseid S. Self-reported asthma and exercise-induced asthma symptoms in high-level competitive cross-country skiers. Scandinavian Journal of Medicine and Science in Sports. 1994;4(2):128–33. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Rundell KW, Im J, Mayers LB, Wilber RL, Szmedra L, Schmitz HR. Self-reported symptoms and exercise-induced asthma in the elite athlete. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2001;33(2):208–13. doi: 10.1097/00005768-200102000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Orenstein D. Asthma and sport. In: Bar-Or O, editor. The child and adolescent athlete. Oxford UK: Blackwell Science Ltd; 1996. pp. 433–54. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zwick H, Popp W, Budik G, Wanke T, Rauscher H. Increased sensitization to aeroallergens in competitive swimmers. Lung. 1990;168(2):111–5. doi: 10.1007/BF02719681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Helenius IJ, Tikkanen HO, Sarna S, Haahtela T. Asthma and increased bronchial responsiveness in elite athletes: atopy and sport event as risk factors. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1998;101(5):646–52. doi: 10.1016/S0091-6749(98)70173-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Goldsmith RL, Bigger JT, Jr, Steinman RC, Fleiss JL. Comparison of 24-hour parasympathetic activity in endurance-trained and untrained young men. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1992;20(3):552–8. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(92)90007-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.O'Cain CF, Dowling NB, Slutsky AS, Hensley MJ, Strohl KP, McFadden ER, Jr, Ingram RH., Jr Airway effects of respiratory heat loss in normal subjects. J Appl Physiol. 1980;49(5):875–80. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1980.49.5.875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Paul DW, Bogaard JM, Hop WC. The bronchoconstrictor effect of strenuous exercise at low temperatures in normal athletes. Int J Sports Med. 1993;14(8):433–6. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1021205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Deal EC, Jr, McFadden ER, Jr, Ingram RH, Jr, Strauss RH, Jaeger JJ. Role of respiratory heat exchange in production of exercise-induced asthma. J Appl Physiol. 1979;46(3):467–75. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1979.46.3.467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Aitken ML, Marini JJ. Effect of heat delivery and extraction on airway conductance in normal and in asthmatic subjects. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1985;131(3):357–61. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1985.131.3.357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Rundell KW, Spiering BA, Judelson DA, Wilson MH. Bronchoconstriction during cross-country skiing: is there really a refractory period? Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2003;35(1):18–26. doi: 10.1097/00005768-200301000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Bavarian B, Mehrkhani F, Ziaee V, Yousefi A, Noorian R. Sensitivity and Specificity of Self-Reported Symptoms for Exercise-Induced Bronchospasm Diagnosis in Children. Iranian Journal of Pediatrics. 2009;19(1):47–51. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Barnes PJ, Fitzgerald GA, Dollery CT. Circadian variation in adrenergic responses in asthmatic subjects. Clin Sci (Lond) 1982;62(4):349–54. doi: 10.1042/cs0620349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Nieman DC. Upper respiratory tract infections and exercise. Thorax. 1995;50(12):1229–31. doi: 10.1136/thx.50.12.1229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Leuppi JD, Kuhn M, Comminot C, Reinhart WH. High prevalence of bronchial hyperresponsiveness and asthma in ice hockey players. Eur Respir J. 1998;12(1):13–6. doi: 10.1183/09031936.98.12010013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Brudno DS, Wagner JM, Rupp NT. Length of postexercise assessment in the determination of exercise-induced bronchospasm. Ann Allergy. 1994;73(3):227–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Helenius IJ, Tikkanen HO, Haahtela T. Association between type of training and risk of asthma in elite athletes. Thorax. 1997;52(2):157–60. doi: 10.1136/thx.52.2.157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Chapman KR, Allen LJ, Romet TT. Pulmonary function in normal subjects following exercise at cold ambient temperatures. Eur J Appl Physiol Occup Physiol. 1990;60(3):228–32. doi: 10.1007/BF00839164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Pekkarinen H, Tukiainen H, Litmanen H, Huttunen J, Karstu T, Länsimies E. Effect of submaximal exercise at low temperatures on pulmonary function in healthy young men. Eur J Appl Physiol Occup Physiol. 1989;58(8):821–5. doi: 10.1007/BF02332213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]