Summary

Pediatric hand fractures are common childhood injuries. Identification of the fractures in the emergency room setting can be challenging owing to the physes and incomplete ossification of the carpus that are not revealed in the xrays. Most simple fractures can be treated with appropriate immobilization through buddy taping, finger splints, or casting. If correctly diagnosed, reduced and immobilized, these fractures usually result in excellent clinical outcomes. However, fractures may require operative stabilization if they have substantial angulation or rotation, extend into the joint, or cannot be held in a reduced position with splinting alone. Most fractures can be treated operatively with closed reduction and percutaneous pinning if addressed within the first week following the injury. In children, the thick, vascular-rich periosteum and bony remodeling potential make anatomic reductions and internal fixation rarely necessary. Most fractures complete bony healing in 3-4 weeks, with the scaphoid being a notable exception. Following immobilization, children rarely develop hand stiffness and formal occupational therapy is usually not necessary. Despite the high potential for excellent outcomes in pediatric hand fractures, some fractures remain difficult to diagnose and treat.

Keywords: Pediatric hand fractures, Pediatric hand injuries

A number of pediatric hand fractures have fairly innocuous presentations, but require early recognition and intervention to achieve satisfactory outcomes. Seymour fractures (open distal phalanx physeal fracture with proximal nail fold incarceration) must be identified and treated operatively to avoid infection, malunion, and nail deformities. Distal condylar phalangeal (DCP) fractures are difficult to address if not reduced at the time of injury. An osteotomy to correct a DCP malunion can be fraught with complications, and sagittal plane deformities may be able to remodel better than previously thought. Scaphoid waist fractures in adolescents, if not identified shortly after injury and immobilized appropriately, may result in non-union.

Epidemiology

Distinguishing true “pediatric” hand fractures from fractures occurring in skeletally immature children and adolescents can be difficult if using epidemiologic studies only. Typically, a “pediatric” hand fracture would include children who continue to have open physes and therefore deserve special consideration regarding immobilization, remodeling potential, and surgical indications. Population database studies often use 18 years as a cut-off age for defining these fractures and may overestimate the prevalence of true pediatric hand fractures.

Fifteen percent of all fractures seen in the ER setting are hand fractures and nearly half of these fractures are a result either of sports activities or fights.1,2 In the pediatric population, hand fractures make up 2.3% of all ER visits, and the incidence of these fractures varies significantly by age. 3,4 In the UK, a stratified examination found the number of hand fractures per year within the general pediatric population to be low in toddlers (34/100,000 children), and increased nearly 20-fold after the 10th year to 663 hand fractures each year per 100,000 children ages 11-18.4

In a comprehensive examination of the 1998 National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey from US facilities, Chung et al. stratified both the injuries and the patients by age, and found that in children 5-14 the carpal fracture incidence was 131 per 100,000 children, the metacarpal fracture incidence was 250/100,000 children, and the phalangeal fracture incidence was 165.6/100,000 children in this age group.5 The over-all incidence of hand fractures in this high-risk age group was 546/100,000. Cumulatively, these incidence studies suggest emergency room physicians and pediatricians may treat many pediatric hand fractures definitively. In the UK, the incidence of pediatric hand fractures seen in specialty hand clinics for follow-up was only 264/100,000 children, less than half of the overall incidence found in other studies.3-5

Nearly all studies indicate boys suffer hand fractures more frequently than girls, with 65-75% of fractures occurring in males, peaking between the ages of 9-14.1,4,6-8 Phalangeal fractures are more common in the 9-12 year age group, whereas metacarpal fractures are most common in older adolescents 8 The border rays account for the majority of phalangeal and metacarpal fractures, over 75% in one 2006 study.4

Special considerations in the pediatric population

Pediatric bone growth occurs through the physeal plate, but because the physis is unmineralized, it is weaker than the surrounding mature bone. Following a fracture, differential growth at the physis and remodeling in the diaphysis can correct for substantial initial fracture displacement. This occurs most reliably in the plane of motion (i.e. flexion/extension). In fingers, displacement in the sagittal plane may remodel extensively (Figure 1), but remodeling in the coronal plane occurs less reliably.

Figure 1.

This late presentation of a dorsally displaced and shortened P1 fracture in 11 year-old girl demonstrates extensive remodeling in the sagittal plane over 2 years.

The physes are particularly vulnerable in younger children when shear forces are applied to the fingers, stressing the attachments of the chondrocytes at the zone of proliferation.9 In contrast, adolescents tend to place more compressive stresses across the metacarpals (in sports or with punching), resulting in metacarpal shaft fractures as the physes remain strong when compressed.4 Multiple attempts at reduction of physeal fractures can crush and disrupt the layered order of the physis, resulting in an iatrogenic physeal arrest. If a physeal fracture reduction cannot be accomplished in 1 or 2 attempts, it is better to consider open operative reduction to reduce the chance of growth arrest. Physeal arrest can result in difficult to treat angular deformities and joint malalignment due to continued growth in adjacent bones. The physis can be a source of confusion if one is accustomed to primarily reading adult imaging. In a large study of pediatric hand fractures, a misdiagnosis rate of 8% was found on the initial radiology interpretation, where 5 of the 11 misdiagnosed fractures were the normal physeal lucency. 8

Specific Injuries

Distal Tuft Fractures from Crush Injuries

The most common injury in toddler and preschool aged children is a crush injury to the fingertips, resulting in a distal tuft fracture. Tuft fractures account for up to 80% of hand fractures in this age group.4,10 These injuries can also involve soft tissue lacerations and nail bed injuries in addition to the distal phalangeal fracture, and irrigation and debridement remain the mainstay of initial treatment for these open injuries. Immobilization with a clamshell type plastic splint for 2-3 weeks will help protect the sensitive fingertip.

Although antibiotics are typically included as the standard of care for open injuries, there is evidence in adults that routine antibiotics may not be necessary. In a randomized double-blind study, thorough irrigation and debridement alone had no greater infection rates than those given antibiotics after the irrigation and debridement.11 It is unclear whether these results may be generalized to the pediatric population. Only rarely do these distal tuft fractures progress to a non-union, but x-rays may not show signs of union for up to 6 months, so diligence and patience is required when dealing with these injuries (Figure 2).12,13

Figure 2.

Six year-old boy with middle and ring fingertip crush injury and a closed subungal hematoma on the ring finger. The fractures persisted on x-ray 5 months after injury.

Seymour Fractures (open physeal fracture of the distal phalanx)

Originally described in 1966, this open distal phalanx physeal fracture can easily be overlooked as a minor injury to the nail.14. Even so, Seymour fractures can reliably be identified with a good lateral x-ray and a high degree of suspicion. Although the nail bed laceration itself is usually not visible, the proximal edge of the nailplate sits on top of the eponychial fold rather than beneath, making the nail appear “too long” in comparison to the other nails (Figure 3).15

Figure 3.

Innocuous clinical presentation of a Seymour fracture with an open physeal fracture identified on true lateral xray. Note that the lunula appears much larger than any of the other nails, indicating the nail is avulsed from the nail bed and sitting atop the eponychial fold.

Occurring often in older children and adolescents, a mallet finger with blood at the nail fold should be considered an open fracture through the distal phalanx physis (Salter Harris I) and/or metaphysis (Salter Harris II) until proven otherwise. A true lateral x-ray of the DIP joint must be used to confirm the diagnosis (Figure 3). Seymour fractures may closely mimic true mallet fingers at presentation, but the displacement occurs through the fracture rather than the DIP joint, as the insertion of the extensor tendon on the epiphysis is uninjured. Seymour fractures require operative irrigation and debridement, and a careful exploration to remove the proximal nail plate from the site of incarceration. Once the nail plate is extracted, the fracture can be reduced without difficulty.12 The nail itself may help to stabilize the reduction and does not need to be routinely removed.14 In the largest series of these fractures, just over 20% (5 of 23 acute fractures) remained unstable after operative debridement and reduction.16 A single k-wire placed from the fingertip through the DIP joint for 4 weeks will allow the fracture to heal in a reduced position.

Late presentations of Seymour fracture often result in infection, growth arrest and persistent mallet deformity of the distal phalanx.15 A variant of this injury, reported only in toddlers, is a complete dorsal rotation of the epiphysis in Salter Harris I type fractures.17,18,19 At presentation, this is difficult to recognize, as the epiphysis of the distal phalanx does not ossify until 18-24 months. The completely extruded epiphysis results in extensor mechanism dysfunction and distal phalanx deformity combined with a longitudinal growth arrest. There is no consensus on treatment in these cases and outcomes are generally poor.

Bony Mallet Finger Fractures

A flexion force directed to an actively extended finger will result in a bony mallet injury. The extensor tendon avulses a fragment of the epiphysis resulting in an intraarticular fracture that may also extend into the metaphysis of the distal phalanx. Bony mallets in adolescents approaching skeletal maturity present similarly to those in adults, but should be recognized as a Salter-Harris III or IV type fracture. There are no published reports specifically on bony mallets in the pediatric population, but treatment principles are similar to those for adults.20,21 Fractures involving less than 1/3 of the joint surface are not usually unstable and can successfully treated with extension splints, even upon late presentation.22 Fractures with persistent volar subluxation of the distal phalanx, joint incongruity, or fracture fragments larger than 50% of the joint surface should be addressed surgically to restore congruity of the articular surface.23

For non-operative management, adherence to strict splinting is mandatory. Smaller children may have difficulty keeping the extension splint in place due to poor compliance or a poor fit on their plump digit. Some authors suggest that in children who are likely to be non-compliant, it may be more reliable to operatively reduce and pin the fracture.15 Originally described by Ishiguro, extension block pinning is a minimally invasive way to reduce the bony mallet to the remaining joint surface of the distal phalanx.21 The bony fragment is prevented from displacing dorsally while the DIP joint is flexed, then the distal phalanx is skewered on a k-wire and reduced up to the fragment by extending the joint and pinning across the DIP joint in extension (Figure 4).

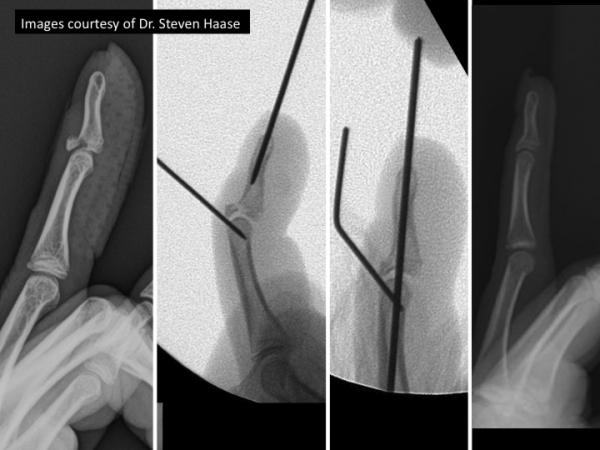

Figure 4.

Fixation of an adolescent bony mallet fracture using ishiguro extendion block technique

Intrarticualar Condylar Split Fractures

The intra-articular condylar split fracture is a problematic fracture, mainly due to its frequent late presentation. A patient's finger may appear normal on an AP radiograph, but the displaced condyle will create a “double density” sign on a true lateral x-ray. These fractures result from an avulsion force, a direct axial blow, or a shearing of the subchondral bone from the underlying shaft and perfect reduction is required for the phalangeal condyles to conform to the facets in the middle or distal phalanx. In the pediatric population, these fragments can be tiny, and delays longer than one week may result in difficulties achieving an adequate closed reduction. The reduction, if addressed early, can be augmented with a towel clip to close the gap between the condyles and secured with K-wires.15

Percutaneous pinning is generally the preferred fixation, rather than other methods of internal fixation, for intracondylar split fractures to prevent tethering of the collateral ligaments. Fortunately, at the distal aspect of phalanx, one does not need to contend with a potential growth disturbance as the physis is located at the proximal aspect of each phalanx. However, if open reduction is required, the soft tissue envelope must be respected to prevent avascular necrosis (AVN).24 In cases of malunion, attempts to perform an osteotomy to improve alignment should be undertaken with great care to preserve the surrounding soft tissue attachments to the distal fragment to reduce the risk of AVN.15 In the setting of a congruous joint with an angular malalignment, an extra-articular osteotomy can be considered (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Two year-old girl with an unwitnessed injury to her left index finger. She presented 10 months later with an intracondylar proximal phalanx malunion. Due to persistent deformity and inability to form a closed fist, she underwent a corrective osteotomy 8 years later with good final results despite the known risk of AVN.

Phalangeal Neck Fractures

Fractures of the proximal and middle phalanx located distal to the collateral ligament recess are called phalangeal neck fractures, or distal condylar phalangeal (DCP) fracture. These fractures tend to displace into extension with dorsal translation, and if left unreduced, a typical volar spike of bone prevents flexion of the joint. This type of fracture occurs almost exclusively in children and have historically been mistaken for a physeal injury at the distal aspect of the phalanx, despite the proximal location of the physis in the phalanges of the fingers.25 True lateral x-rays of the affected finger, without overlap of other fingers, must be obtained to determine the most appropriate course of treatment. Many of these fractures can be successfully reduced in a closed manner because they do not involve the articular surface. However, due to the rapid healing in children, if the fracture is more that 1-2 weeks old, closed reduction will likely not be possible. For reasons not well understood, conservative treatment carries an additional risk for non-union in thumb phalangeal neck fractures and avascular necrosis in the small finger.26

A classification by Al-Quattan using a case series of 66 of these fractures suggests that non-displaced fractures heal well with splinting alone (Type I). The author found that displaced fractures with some remaining bony contact (Type II) were most likely to have good outcomes with operative reduction and fixation.16 Completely displaced DCP fractures with no bony contact (Type III) had the worst outcomes ranging from non-unions to digital necrosis and amputation, especially for late presentations (Figure 6). Owing to the poor blood supply and lack of soft tissue attachments to the distal fragment, this fracture usually requires the pins to be left in place for at least 4 weeks.27

Figure 6.

Three year-old girl presented two weeks after right small finger injury. Xrays show a small finger distal condylar phalangeal (DCP) fracture, with no bony contact (Type III). Despite efforts to reduce and stabilize the fracture, the fracture went on to a non-union with minimal motion at the PIP joint.

Controversy remains as to the necessity of an osteotomy for missed, malunited DCP fractures. Recent case series have shown excellent remodeling in the sagittal plane with non-operative treatment.15,28,29 It should be noted that little remodeling can be expected in the coronal plane, and coronal deformities need to be addressed surgically. Osteotomy carries the risk of avascular necrosis due to the tenuous collateral blood supply of the distal aspect of the phalanx and must be approached with care.27

Proximal Phalanx Fractures

Treatment for fractures along the shaft of the proximal phalanx is dictated by the orientation of the fracture as well as the degree of initial displacement. Management is also guided by clinical evaluation, as very innocuous-looking fractures can have substantial rotational deformities that can lead to problems forming a tight fist and grip. There are no trials comparing one treatment method to another for phalangeal fractures in children, and the literature is largely limited to retrospective case reports and series. Despite this insufficiency, much can be gleaned from the generations of experience in some of these studies.

For length stable fractures with minimal displacement, buddy taping to an adjacent finger for both support and encouragement of early motion can be an effective treatment until the fracture site is no longer tender, typically from 3-4 weeks. Oblique or spiral fractures requiring reduction need more rigid immobilization, such as an ulnar or radial gutter splint or cast. These fractures must be monitored vigilantly for displacement, but this can be difficult to see through casting material. No splint can hold a phalanx fracture “out to length,” it can only control radial and ulnar deviation, flexion, and extension. Length unstable fractures require operative fixation to maintain the reduction.

Fractures at the base of the proximal phalanx occur when the finger is abducted past the normal range of the MCP joint. These fractures are most common in the small finger where they are known as “extra octave” fractures. These fractures can occur transversely through the physis, or just distal to the physis in the metaphysis.16,30,31 Owing to their proximity to the physis, significant remodeling can be expected in all but the most displaced fractures.16 Flexor tendon entrapment, disruption of the collateral ligaments, or fracture comminution can prevent successful closed reduction. As originally described by Beatty et al, using a pencil as a fulcrum in the 4th web space to gain control over the proximal segment of the 5th proximal phalanx fracture can be a useful technique to restore alignment.32

Scaphoid Fractures

Although scaphoid fractures account for only 3% of pediatric fractures of the hand and wrist, they are the most common carpal fracture in this population.33,34

Diagnosis and treatment in the pediatric population relies heavily on an understanding of the ossification and blood supply of the carpal bones. The scaphoid begins to show an ossific nuclei at 4-5 years of age, finishing ossification at 13-15 years of age.35 Fractures are rarely identified before age six because they involve cartilage only, but increase in incidence with each subsequent year, peaking at age 15.36-38

D'Arienzo proposed a three-part classification system that considers the age of the child and the presumed degree of ossification.39 Type 1 lesions are typically seen in children younger than eight and are purely chondral injuries, occurring just proximal to the ossific nuclei at the waist. These fractures are rare and often require an MRI for diagnosis. In children 8-11 years of age, the ossification process has crossed the waist and fractures are osteochondral in nature, and these heal readily if immobilized properly. Type 3 lesions are the most common fractures occurring in adolescents 12 and older. At this age, the scaphoid is nearly completely ossified, and these fractures behave similarly to those in the adult population with a tenuous proximal blood supply. In a retrospective analysis of 351 pediatric scaphoid fractures, the average patient age was 14.6 years, with 71% of fractures occurring at the waist.40 Twenty-three percent occurred at the distal pole, while only 6% occurred at the proximal pole.

In 13-30% of scaphoid fractures, initial radiographs are negative.33,41 Most authors recommend a thumb spica casting for 2 weeks with repeat imaging to determine the course of treatment.39,41,42 There is little consensus on short or long arm casting, however, if radiographs at 2 weeks are negative and the child has improved symptoms, no further immobilization is recommended.39,41,42 MRI may be used to rule out a fracture shortly after the injury. In one study, a negative MRI performed 3-10 days after the injury shortened the course of immobilization in 58% of patients.43

In the previously described study of 351 scaphoid fractures, the authors reported a 90% union rate for casting acute fractures, whereas only 23% of chronic fractures achieved union with casting alone.40 With casting only, acute fractures of the distal pole heal most rapidly, taking from 4 to 8 weeks, whereas waist fractures can take 5-16 weeks to show radiographic healing.36,39,44,45 Once a non-union has been identified, whether due to late presentation, inadequate immobilization, or subsequent fracture displacement, surgical intervention is recommended to improve the union rates. Autologous bone grafting with a volar approach is most commonly used for non-unions and “humpback” deformities, secured with either temporary k-wire fixation or a permanent compression screw (Figure 6). Recently, narrow diameter headless screws have been shown to shorten time to union in older adolescents compared to screws with wider shafts.34 It is proposed that these narrow screws decrease the amount of disruption to the endogenous blood supply, allowing for faster bony healing.

For reasons not completely understood, dorsal intercalated segment instability (DISI) deformities associated with scaphoid non-unions in children have never been observed to progress to scaphoid non-union advanced collapse (SNAC). As opposed to adult scaphoid non-union surgeries, the DISI deformity in children can persist even after the correction of the scaphoid anatomy with bone grafting.42 One case report discussed the resolution of the DISI deformity over time following surgical fixation, whereas another showed persistent, asymptomatic DISI deformities four years after surgery.46,47 Immediate restoration of the lunate orientation following correction of a humpback deformity may not be possible in adolescents. However, the growing carpus may retain some remodeling capacity, allowing for some correction of the malalignment over time.48

Closed Treatment and Immobilization

The vast majority of phalangeal and metacarpal fractures are minimally displaced, stable fractures. The thick periosteal covering and ability of the bone to plastically deform afford a great deal of stability in incomplete fractures. These fractures require minimal augmentation due to their inherent stability and rapid fracture healing. The periosteum can be a powerful tool for reduction in children, providing a “hinge” to lever the distal segment on the proximal portion of the bone to attain anatomic alignment.49

Nearly all active children will attempt escape from even the best-molded cast, and therefore compliance should never be assumed. For younger children, long arm casts with just 2 or 3 layers of padding will prevent motion within the cast and stop the cast from slipping distally on the arm. In addition, supracondylar molding of the fiberglass can help to prevent the elbow pulling proximally within the upper portion of the cast. If a fracture must be perfectly immobile to maintain a reduction, augmentation with k-wires is advisable. Most well-aligned fractures do not need to be immobilized for longer than 4 weeks, as most healing at the physis occurs within 3 weeks, with slightly slower healing noted at the diaphysis.50

Operative considerations

In most pediatric hand fractures, closed reduction and percutaneous pinning remain the mainstay of operative treatment for acute displaced fractures that cannot be closed reduced and held in position with splinting alone. A limited open approach may be used to extract interposed tissue, usually either a tendon or the volar plate in phalangeal fractures. A K-wire may be gently inserted into the fracture site and be used to create leverage for reduction once any interposed tissue is removed.26,29 A fracture may be secured with multiple wires, but care must be taken to not create a pivot point at the fracture site by crossing the pins. Ideally, the pins should diverge at the fracture site to optimize stability, but can be difficult to achieve in very small children. Fortunately, most fractures have a robust soft tissue envelope to aid stability.

Once K-wires are in place, they must be protected at all times with a cast or brace if left outside the skin for later removal, and rarely do these wires need to stay in place longer than 3-4 weeks. The length of percutaneous k-wire fixation does not appear to correlate to rates of infection, therefore routine antibiotics are not necessary.51 If the wire ends are capped and out of the skin, even toddlers usually tolerate removal of the pins in the office. If a longer period of immobilization is desired, as in a scaphoid non-union, pins may be cut below the skin for convenience, but then require a return to the OR for removal. If a skin incision closure is required, absorbable sutures (such as 4-0 chromic) must be used to prevent tedious suture removal on a screaming child.

Key Takeaway Points.

Hand fractures in children are common; conservative management is usually sufficient if initiated early

Seymour fractures (open physeal fracture of the distal phalanx) should be diagnosed with a good lateral x-ray to ensure timely operative extrication of the nail plate, irrigation and debridement, fracture reduction and percutaneous pinning.

Finger malrotation in metacarpal and phalangeal fractures must be assessed clinically, as x-rays may not reveal the deformity

Late presentations of displaced distal condylar phalanx fractures may be managed conservatively if well aligned in the coronal x-ray because sagittal malalignment can remodel, even in older children

Suspected scaphoid fractures in adolescents may be ruled out using MRI to decrease the immobilization time. Scaphoid non-unions will require operative fixation and possible bone grafting, but an associated DISI deformity may not improve with restoration of scaphoid anatomy.

Acknowledgments

Supported in part by grants from the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases and from the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases (2R01 AR047328-06) and a Midcareer Investigator Award in Patient-Oriented Research (K24 AR053120) (to Dr. Kevin C. Chung)

References

- 1.Landin LA. Epidemiology of children's fractures. J of Pediatric Orthopaedics. 1997;6(2):79–83. doi: 10.1097/01202412-199704000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Worlock P, Stower M. Fracture patterns in Nottingham children. J of Pediatric Orthopedics. 1986;6(6):656–660. doi: 10.1097/01241398-198611000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Worlock P, Stower M. The incidence and pattern of hand fractures in children. J of Hand Surg (Br) 1986;11(2):198–200. doi: 10.1016/0266-7681(86)90259-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vadivelu R, Dias JJ, Burke FD, Stanton J. Hand injuries in children: a prospective study. J Ped Orthopedics. 2006;26(1):29–35. doi: 10.1097/01.bpo.0000189970.37037.59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chung KC, Spilson SV. The frequency and epidemiology of hand and forearm fractures in the United States. J Hand Surg (Am) 2001;26(5):908–915. doi: 10.1053/jhsu.2001.26322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mahabir RC, Kazemi ALIR, Cannon WG, Courtemanche DJ. Pediatric hand fractures: a review. Pediatric Emergency Care. 2001;17(3):153–156. doi: 10.1097/00006565-200106000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bhende MS, Dandrea LA, Davis HW. Hand injuries in children presenting to a pediatric emergency department. Annals of Emergency Medicine. 1993;22(10):1519–1523. doi: 10.1016/s0196-0644(05)81251-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chew EM, Chong AKS. Hand fractures in children: epidemiology and misdiagnosis in a tertiary referral hospital. J Hand Surg (Am) 2012;37(8):1684–1688. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2012.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Salter RB, Harris WR. Injuries involving the epiphyseal plate. J Bone and Joint Surgery. 1963;45(3):587–622. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rajesh A, Basu AK, Vaidhyanath R, Finlay D. Hand fractures: a study of their site and type in childhood. Clinical Radiology. 2001;56(8):667–669. doi: 10.1053/crad.2001.0753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stevenson J, McNaughton G, Riley J. The use of prophylactic flucloxacillin in treatment of open fractures of the distal phalanx within an accident and emergency department: a double-blind randomized placebo-controlled trial. J Hand Surg (Br) 2003;28(5):388–394. doi: 10.1016/s0266-7681(03)00175-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Al Qattan M, Hashem F, Helmi A. Irreducible tuft fractures of the distal phalanx. J Hand Surg (Br) 2003;28(1):18–20. doi: 10.1054/jhsb.2002.0814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.DaCruz D, Slade R, Malone W. Fractures of the distal phalanges. J Hand Surg (Br) 1988;13(3):350–352. doi: 10.1016/0266-7681_88_90111-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Seymour N. Juxta-Epiphysial Fracture of the Terminal Phalanx of the Finger. J Bone and Joint Surg (Br) 1966;48(2):347–349. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cornwall R, Waters PM. Remodeling of phalangeal neck fracture malunions in children: case report. J Hand Surg (Am) 2004;29(3):458–461. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2004.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Al-Qattan M. Extra-articular transverse fractures of the base of the distal phalanx in children and adults. J of Hand Surg (Br) 2001;26(3):201–206. doi: 10.1054/jhsb.2000.0549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Waters PM, Benson LS. Dislocation of the distal phalanx epiphysis in toddlers. J Hand Surg (Am) 1993;18(4):581–585. doi: 10.1016/0363-5023(93)90293-C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Keene JS, Engber WD, Stromberg W. An irreducible phalangeal epiphyseal fracture-dislocation. A case report. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1984;186:212–215. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.de Jong A, Haddad B, Wood M. Irreducible dorsal epiphyseal fracture dislocation of the distal phalanx: a case report. Hand. 2013 doi: 10.1007/s11552-012-9489-y. (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wehbe M, Schneider L. Mallet fractures. J Bone and Joint Surg (Am) 1984;66(5):658–669. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ishiguro T, Itoh Y, Yabe Y, Hashizume N. Extension block with Kirschner wire for fracture dislocation of the distal interphalangeal joint. Tech in Hand & Upper Ext Surg. 1997;1(2):95–102. doi: 10.1097/00130911-199706000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kalainov DM, Hoepfner PE, Hartigan BJ, Carroll C, Genuario J. Nonsurgical treatment of closed mallet finger fractures. J Hand Surg (Am) 2005;30(3):580–586. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2005.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pegoli L, Toh S, Arai K, Fukuda A, Nishikawa S, Vallejo I. The Ishiguro extension block technique for the treatment of mallet finger fracture: indications and clinical results. J Hand Surg (Br) 2003;28(1):15–17. doi: 10.1054/jhsb.2001.0733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Topouchian V, Fitoussi F, Jehanno P, Frajman J, Mazda K, Pennecot G. Treatment of phalangeal neck fractures in children: technical suggestion. Chirurgie Main. 2003;22(6):299–304. doi: 10.1016/j.main.2003.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Puckett BN, Gaston RG, Peljovich AE, Lourie GM, Floyd WE. Remodeling potential of phalangeal distal condylar malunions in children. J Hand Surg (Am) 2012;37(1):34–41. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2011.09.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Al-Qattan M. Nonunion and avascular necrosis following phalangeal neck fractures in children. J Hand Surg (Am) 2010;35(8):1269–1274. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2010.03.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yousif N, Cunningham M, Sanger J, Gingrass R, Matloub H. The vascular supply to the proximal interphalangeal joint. J Hand Surg (Am) 1985;10(6 Pt 1):852–861. doi: 10.1016/s0363-5023(85)80161-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hennrikus W, Cohen M. Complete remodelling of displaced fractures of the neck of the phalanx. J Bone and Joint Surg (Br) 2003;85(2):273–274. doi: 10.1302/0301-620x.85b2.13167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mintzer C, Waters P, Brown D. Remodelling of a displaced phalangeal neck fracture. J Hand Surg (Br) 1994;19(5):594–596. doi: 10.1016/0266-7681(94)90122-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fischer MD, McElfresh EC. Physeal and periphyseal injuries of the hand. Patterns of injury and results of treatment. Hand Clinics. 1994;10(2):287–301. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Leclercq C, Korn W. Articular fractures of the fingers in children. Hand Clinics. 2000;16(4):523–534. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Beatty E, Light T, Belsole R, Ogden J. Wrist and hand skeletal injuries in children. Hand Clinics. 1990;6(4):723–738. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Christodoulou A, Colton C. Scaphoid fractures in children. J Pediatric Orthopaedics. 1986;6(1):37–39. doi: 10.1097/01241398-198601000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gholson JJ, Bae DS, Zurakowski D, Waters PM. Scaphoid fractures in children and adolescents: contemporary injury patterns and factors influencing time to union. J Bone and Joint Surg (Am) 2011;93(13):1210–1219. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.J.01729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Stuart HC, Pyle SI, Cornoni J, Reed RB. Onsets, completions and spans of ossification in the 29 bone-growth centers of the hand and wrist. Pediatrics. 1962;29(2):237–249. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mussbichler H. Injuries of the carpal scaphoid in children. Acta Radiologica. 1961;56:361–368. doi: 10.3109/00016926109172830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Toh S, Miura H, Arai K, Yasumura M, Wada M, Tsubo K. Scaphoid fractures in children: problems and treatment. Journal of Pediatric Orthopaedics. 2003;23(2):216–221. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bloem J. Fracture of the carpal scaphoid in a child aged 4. Arch Chir Neerl. 1971;23(1):91–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.D'Arienzo M. Scaphoid fractures in children. J Hand Surgery (Br) 2002;27(5):424–426. doi: 10.1054/jhsb.2002.0820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gholson JJ, Bae DS, Zurakowski D, Waters PM. Scaphoid fractures in children and adolescents: contemporary injury patterns and factors influencing time to union. JBJS (Am) 2011;93(13):1210–1219. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.J.01729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Evenski AJ, Adamczyk MJ, Steiner RP, Morscher MA, Riley PM. Clinically suspected scaphoid fractures in children. J Pediatric Orthopaedics. 2009;29(4):352–355. doi: 10.1097/BPO.0b013e3181a5a667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Anz AW, Bushnell BD, Bynum DK, Chloros GD, Wiesler ER. Pediatric scaphoid fractures. J Amer Academy of Orthopaedic Surg. 2009;17(2):77–87. doi: 10.5435/00124635-200902000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Johnson KJ, Haigh SF, Symonds KE. MRI in the management of scaphoid fractures in skeletally immature patients. Pediatric Radiology. 2000;30(10):685–688. doi: 10.1007/s002470000305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gamble JG, Simmons SC., III Bilateral scaphoid fractures in a child. Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research. 1982;162:125–128. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Vahvenen V, Westerlund M. Fracture of the carpal scaphoid in children: a clinical and roentgenological study of 108 cases. Acta Orthopaedica. 1980;51(1-6):909–913. doi: 10.3109/17453678008990893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Suzuki K, Herbert TJ. Spontaneous correction of dorsal intercalated segment instability deformity with scaphoid malunion in the skeletally immature. J Hand Surg (Am) 1993;18(6):1012–1015. doi: 10.1016/0363-5023(93)90393-H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mintzer C, Waters P, Simmons B. Nonunion of the scaphoid in children treated by Herbert screw fixation and bone grafting. A report of five cases. J Bone and Joint Surg (Br) 1995;77(1):98–100. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hamdi MF, Khelifi A. Operative management of nonunion scaphoid fracture in children: a case report and literature review. Musculoskeletal Surgery. 2011;95(1):49–52. doi: 10.1007/s12306-010-0092-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Charnley J. The closed treatment of common fractures. Cambridge University Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rang M. Injuries of the Epiphysis, Growth Plaste and Perichondrial Ring. In: Rang M, editor. Children's Fractures. JB Lippincott; 1983. pp. 10–25. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Battle J, Carmichael KD. Incidence of pin track infections in children's fractures treated with Kirschner wire fixation. J Pediatric Orthopaedics. 2007;27(2):154–157. doi: 10.1097/bpo.0b013e3180317a22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]