Abstract

Molecular imaging methods have previously been employed to image tissue-specific reporter gene expression by a two-step transcriptional amplification (TSTA) strategy. We have now developed a new bidirectional vector system, based on the TSTA strategy, that can simultaneously amplify expression for both a target gene and a reporter gene, using a relatively weak promoter. We used the synthetic Renilla luciferase (hrl) and firefly luciferase (fl) reporter genes to validate the system in cell cultures and in living mice. When mammalian cells were transiently cotransfected with the GAL4-responsive bidirectional reporter vector and various doses of the activator plasmid encoding the GAL4-VP16 fusion protein, pSV40-GAL4-VP16, a high correlation (r2 = 0.95) was observed between the expression levels of both reporter genes. Good correlations (r2 = 0.82 and 0.66, respectively) were also observed in vivo when the transiently transfected cells were implanted subcutaneously in mice or when the two plasmids were delivered by hydrodynamic injection and imaged. This work establishes a novel bidirectional vector approach utilizing the TSTA strategy for both target and reporter gene amplification. This validated approach should prove useful for the development of novel gene therapy vectors, as well as for transgenic models, allowing noninvasive imaging for indirect monitoring and amplification of target gene expression.

INTRODUCTION

Conventional noninvasive cancer therapy is often hampered by a lack of tumor specificity that frequently culminates in unwanted severe adverse effects, thereby limiting therapeutic doses and rendering the malignant lesions resilient to treatment (Nettelbeck et al., 1998, 2000). Gene therapy continues to be investigated as a potential alternative to the drawbacks of traditional cancer therapy. Thus the goal is to achieve high levels of transcription of a transgene in the desired cell population by the use of cell-specific promoters or regulatory elements. However, a majority of these tissue-specific promoters are also inherently weaker activators of transcription, and even when suitably delivered to the target site, are often unable to achieve therapeutic levels of the protein transcribed from the therapeutic gene (TG). Thus it became imperative to design strategies to enhance promoter strength, while maintaining specificity, of these weak tissue-specific promoters (Nettelbeck et al., 2000).

Several strategies have been successfully implemented so far. These include (1) designing a minimal promoter by eliminating from a natural promoter all the other elements that do not contribute to promoter strength, (2) designing promoters containing activated point mutations, (3) constructing chimeric promoters by combining the transcriptional regulatory elements from different promoters specific for the same tissue, (4) enhancement at the posttranslational level, and (5) using recombinant transcriptional activators (RTAs) that assist in achieving transcriptional amplification (Nettelbeck et al., 2000; Iyer et al., 2001).

The RTA approach, also referred to as the two-step transcriptional amplification (TSTA) approach, has been effectively used to enhance the transcriptional ability of tissue-specific promoters in both cell culture and in living animals. In this approach the promoter drives the production of the potent GAL4-VP16 transcriptional activator, encoded by the “activator” plasmid. This chimeric transcription factor, consisting of the highly potent activation domain of the herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV1) VP16 immediate-early trans-activator fused to the yeast GAL4-DNA-binding domain, in turn acts on a second expression plasmid encoding the reporter/therapeutic proteins through a GAL4-responsive minimal promoter bearing multiple tandem copies of the 17-bp GAL4-binding sites (G5) placed upstream from the genes of interest. Iyer et al. (2001) and Zhang et al. (2002) used the TSTA strategy, in combination with positron emission tomography (PET) and optical methods, to amplify and image the expression of reporter genes—mutant HSV1 thymidine kinase (HSV1-sr39tk) and firefly luciferase (fl), respectively—in living animals. These studies validated the ability of the TSTA system to enhance the transcriptional ability of a weak tissue-specific promoter, the prostate-specific antigen enhancer/promoter (PSE). The system was also valuable in demonstrating androgen-responsive activity in prostate cancer cells (Iyer et al., 2001; Zhang et al., 2002). Another study used a similar approach to achieve tumor-specific amplification of gene expression from a novel suicide gene therapy adenoviral vector driven by a weak tissue-specific CEA promoter (Qiao et al., 2002).

Precise localization and quantitative assessment of the level of gene expression are highly desirable for the evaluation of gene therapy trials (Massoud and Gambhir, 2003). A number of methodologies can be employed to image reporter genes in living subjects. Among them PET, single-photon emission computed tomography (SPECT), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and optical imaging are well standardized and can be extensively used to study reporter gene expression repeatedly and noninvasively (Wang, 2001; Weber et al., 2001; Massoud and Gambhir, 2003; Ray et al., 2003). Although PET has good spatial resolution, high sensitivity, and tomographic capabilities, it is limited by higher cost and the risk of radioactive exposure. In contrast, optical imaging techniques (fluorescence and bioluminescence) can be a low-cost and quick alternative for real-time analysis of gene expression in small animals with just transiently transfected cells (Zhang et al., 1999; Contag and Bachmann, 2002; Contag and Ross, 2002; Negrin et al., 2002; Ray et al., 2003). Our laboratory has successfully used both fl and synthetic Renilla luciferase (hrl) as bioluminescence optical reporter genes to study gene expression in small animals. We have also reported that both fl and hrl can be imaged in the same animal and that they present different light production kinetics without any substrate cross-reactivity (Bhaumik and Gambhir, 2002a, 2002b).

Gene expression can be imaged directly if the transgene or therapeutic gene (TG) is also an imaging reporter gene (RG), for example, HSV1-tk or the mutant thymidine kinase (HSV1-sr39tk) gene, whose protein product HSV1 thymidine kinase (HSV1-TK/SR39TK) can trap various radiolabeled substrates in cells and hence can be detected by PET/SPECT (Gambhir et al., 1998, 2000; Eckelman et al., 2000; Lammertsma, 2001; Luker and Piwnica-Worms, 2001; Sharma et al., 2002; Blake et al., 2003; Massoud and Gambhir, 2003). Unfortunately, most therapeutic transgenes lack the appropriate ligands or substrates that can be radiolabeled and used to generate images that define the magnitude of gene expression. Thus general strategies have been developed and validated to link the expression of the TG to a PET or optical RG and to track in vivo expression of the TG indirectly by imaging the RG. Linking the expression of the TG to the RG can be achieved through a variety of different molecular constructs (Ray et al., 2001; Sundaresan and Gambhir, 2002). One approach is to clone both genes, one immediately following the other (with or without a short spacer) (Ray et al., 2003), downstream of a single promoter. A single mRNA strand carrying the coding regions of both genes will be transcribed from this construct and will encode a fusion protein. This approach requires that the function of the reporter protein or the therapeutic protein not be significantly compromised as a result of the fusion. A second approach is to place both genes in different locations in the same vector, each downstream of identical but independent promoters (Ray et al., 2001; Sun et al., 2001; Yaghoubi et al., 2001). Because the promoters are identical, theoretically, the two separate mRNAs and proteins that are produced should be correlated. A simpler method is to coadminister two identical vectors, one carrying the TG and the other the RG. Our laboratory has demonstrated that it is possible to macroscopically correlate the expression of two genes by regulating their transcription with the same promoter, but delivering them on separate adenoviral vectors (Yaghoubi et al., 2001). An additional method for transcriptional linking of the TG with the RG is by the use of a bicistronic vector, containing an internal ribosomal entry site (IRES). In this case both genes are transcribed into a single mRNA from the same promoter but are translated into two different proteins with the help of the IRES sequences (Ray et al., 2001). Yu et al. constructed such a vector in which the dopamine type 2 receptor (D2R) RG was placed upstream and the HSV1-sr39tk RG was placed downstream of the encephalomyocarditis (EMCV) IRES. Transcription of both genes was directed by a cytomegalovirus (CMV) promoter (Yu et al., 2000). C6 glioma cells stably transfected with the vector expressed both genes with high correlation. However, a drawback of the IRES system is the attenuation of expression of the gene downstream of the IRES sequence. Chappell et al. identified a novel IRES within the mRNA of the homeodomain protein Gtx that produced 60-fold higher activity compared with the EMCV–IRES in cell cultures (Chappell et al., 2000). Our laboratory has used the Gtx–IRES to produce novel gene therapy vectors to overcome the attenuation of the downstream gene (Wang, 2001).

Earlier, Baron et al. (1995) constructed a tetracycline-inducible novel vector system in which a single bidirectional tetracycline-inducible promoter can be used to control the expression of any pair of genes in a correlated, dose-dependent manner. We applied this bidirectional strategy and obtained highly correlated expression of two PET reporter genes in living subjects (Sun et al., 2001).

In the current study, our objective was to develop a new bidirectional vector system, based on the TSTA/RTA model, that can amplify the expression of both a TG and a RG simultaneously (Fig. 1). This system should help in determining the spatial location(s) and level of expression of the target gene with the help of the highly correlated expression of the tightly coupled reporter gene, which can be imaged non-invasively. The system consists of two components: (1) an activator plasmid encoding the GAL4-VP16 trans-activator protein and (2) a reporter plasmid carrying two optical reporter genes in opposite orientations flanking a bidirectional GAL4-responsive promoter system. One or both of the reporter genes can be changed to a therapeutic gene of interest. Our results show that two optical reporter genes encoding firefly luciferase (FL) and synthetic Renilla luciferase (hRL) are indeed coregulated in a quantitative manner by means of this strategy, both in cell culture as well as in living animals imaged with an optical system.

FIG. 1.

Schematic diagram of the bidirectional system. The first construct is the activator plasmid pSV40-GAL4-VP16 (referred to as VP16 in text), responsible for driving expression of the GAL4-VP16 fusion protein under the control of the constitutive SV40 promoter. GAL4-VP16 consists of the N-terminal portion of the VP16 activation domain (amino acids 413–454) fused to the GAL4 DNA-binding domain (amino acids 1–147). The second construct depicts the design of the bidirectional reporter plasmid (fl-G5-hrl). The genes are under the control of the GAL4-responsive bidirectional minimal promoter. One of two genes can be a target gene (TG) (hrl) while the other can be a reporter gene (RG) (fl). The GAL4-VP16 fusion protein can potentially lead to amplification of both TG and RG simultaneously, with the tightly coupled reporter gene providing indirect quantitation and imaging locations of the TG.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Chemicals

Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) was purchased from GIBCO-BRL (Grand Island, NY). A luciferase assay kit was purchased from Promega (Madison, WI). D-Luciferin potassium salt, a substrate for FL, was obtained from Xenogen (Alameda, CA). Coelenterazine, the substrate for hRL, was purchased from Biotium (Hayward, CA).

Cell culture

N2a cells (mouse neuroblastoma), 293T cells (human kidney), and HeLa cells (human cervical carcinoma) were grown in DMEM high-glucose supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and 1% penicillin–streptomycin solution.

Construction of plasmids/vectors

The activator plasmid pSP72-SV40-GAL4-VP16 was constructed as described earlier (Iyer et al., 2001). Multiple steps of cloning and polymerase chain reaction (PCR) amplifications were employed to construct the bidirectional fl-G5-hrl (reporter) plasmid that contains a GAL4-responsive bidirectional promoter in the center connecting the forward (hrl) and backward (fl) genes. The promoter consists of five GAL4-binding sites (17 bp each) flanked on each side by two TATA box-containing minimal promoters from the adenoviral E4 gene (E4TATA) as described previously (Iyer et al., 2001). The hrl gene excised from the pCMV-hrl plasmid (Promega) was first inserted between the NheI and NotI sites in multiple cloning site I (MCSI) of the PBIL vector obtained from BD Biosciences Clontech (Palo Alto, CA). The G5-E4T cassette was PCR amplified from the G5E4T-fl vector (Iyer et al., 2001), using a 5′-end primer with an StuI site attached (AATTAGGCCTAATTCTCGAGATTTAGGTGACACTATAGAAT) and a 3′-end primer with an NheI site attached (AATTGCTAGCACACCACTCGACACGGCACC). The 5′-end primer also encoded a unique XhoI site just following the StuI site. The PCR fragment was subsequently digested with StuI and NheI and cloned into the PBIL vector. The second E4TATA minimal promoter was then inserted in the (−) strand preceding the fl gene in the vector. The E4TATA sequence was PCR amplified from the pSP72-E4TATA-CAT plasmid (Iyer et al., 2001), using an upstream primer with an XhoI site (AATTCTCGAGGGATCCCCAGTCCTATATATACT) and a 3′-end primer with an SacII site (AATTCCGCGGACACCACTCGACACGGCACC). The E4T-G5-E4T cassette completely replaced the TRE promoter element in the original PBIL vector.

For the sake of convenience the bidirectional reporter template with fl and hrl is abbreviated as fl-G5-hrl, the trans-activator plasmid pSV40-GAL4-VP16 is VP16, and the unidirectional TSTA system is G5fl.

Cell transfections and enzyme assays

Cells were plated in 12-well plates in DMEM containing 10% FBS. Transient transfections were performed 36 hr later with Superfect transfection reagent. Each transfection mix contained different dose combinations of the reporter plasmid fl-G5-hrl and the activator plasmid VP16. After 24 hr of incubation the cells were harvested and the cell lysate was used for enzyme assays.

Luciferase assays

All bioluminescence assays were performed in a TD 20/20 luminometer (Turner Designs, Sunnyvale, CA) with an integration time of 10 sec. The protein content of the cell lysates was determined with a Bio-Rad protein assay system (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) in a DU-50 spectrophotometer (Beckman Coulter, Fullerton, CA) and the luminescence results are reported as relative light units (RLU) per microgram of protein.

FL assays were carried on with a luciferase assay kit from Promega. Renilla luciferase assays were performed as described previously (Bhaumik and Gambhir, 2002a).

Preparation of coelenterazine and D-luciferin

A stock solution of coelenterazine in methanol (2 mg/ml) was further diluted with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). A 15-mg/ml stock solution of D-luciferin in PBS was filtered through 0.22-μm pore size filters before use.

Imaging FL and hRL bioluminescence in living animals

All handling of animals was performed in accordance with University of California, Los Angeles and Animal Research Committee guidelines. N2a cells were transiently cotransfected with fl-G5-hrl and various doses of VP16. Cells were harvested 24 hr after transfection and resuspended in PBS. Adult male nude mice were injected with 1 × 106 cells in four different sites subcutaneously, each site representing cells transfected with a particular dose of the activator plasmid, 30 min before imaging. The naked DNA experiments were performed in male CD-1 mice more than 6 weeks of age. Both plasmids, in different proportions (as described in Results), were mixed thoroughly with 2 ml of PBS and kept in ice. The whole volume was then rapidly (within 2–3 sec) injected (hydrodynamic injection) into the tail vein of each animal. Animals were subjected to bioluminescence imaging 6 and 24 hr postinjection.

For imaging hrl gene expression 100 μl of the coelenterazine (20 μg for xenograft studies and 40 μg for naked DNA experiments) was injected via the tail vein approximately 10 sec before imaging, whereas to image fl gene expression 200 μl of D-luciferin (3 mg) was injected intraperitoneally 10 min before imaging. All mice were imaged with a cooled charge-coupled device (CCD) camera (IVIS; Xenogen) and photons emitted from cells implanted in the mice were collected and integrated for a period of 1 min. Images were obtained with Living Image software (Xenogen) and IGOR image analysis software (Wavemetrics, Lake Oswego, OR). Imaging was continued until the hRL signal dropped beyond detectable limits (~2 hr). The animals were then injected intraperitoneally with 200 μl of D-luciferin stock solution and each animal was imaged for 15 min, with 1 min of acquisition each time.

For quantification, regions of interest (ROIs) were drawn over the sites of implantation and maximum photons/sec/cm2/steradian was obtained.

Statistical testing

Linear regression analysis was performed to assess the linear relationship between two variables. The strength of correlation between them was quantified in terms of the square of the Pearson correlation coefficient (r2). The significance of correlation was obtained by performing the Student t test against the null hypothesis that the correlation coefficient (r) is zero. Values of p < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. All cell culture and mouse group comparisons were performed with a Student t test. Values of p ≤ 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

A GAL4-responsive bidirectional strategy can amplify the expression of two independent reporter genes in transiently transfected cells

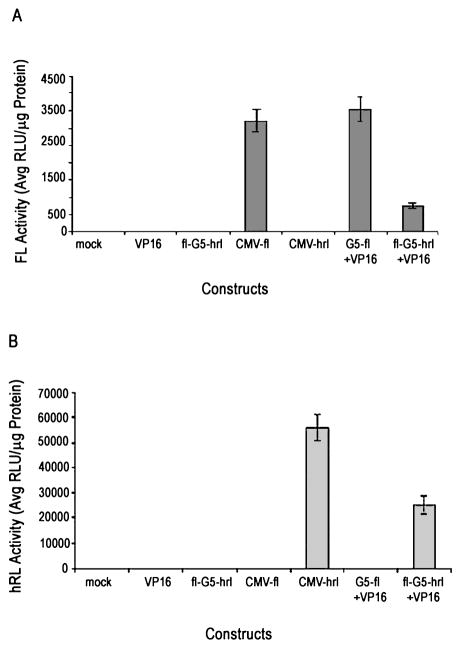

To determine, in cell culture, whether this novel strategy has the potential to amplify the expression of both reporter genes simultaneously, N2a cells were transiently cotransfected in 12-well plates with the activator (VP16) and the reporter (fl-G5-hrl) plasmids in a 1:1 ratio and the cell lysates were assayed 24 hr after transfection. Robust expressions of both reporter genes were obtained in the presence of the GAL4-VP16 fusion protein compared to cells transfected with the same amount of reporter plasmid alone (Fig. 2A and B). Firefly luciferase protein activity is about 2000-fold higher than in mock-transfected cells and cells transfected with activator plasmid only, and about 300-fold higher than in cells transfected with only the reporter plasmid. Similarly, there is a 500- and 600-fold gain in expression of the hrl gene in cells cotransfected with both plasmids compared with cells carrying only the activator plasmid or the reporter plasmid, respectively, and a 700-fold gain compared with mock-transfected cells. This result illustrates, primarily, that this novel vector will allow us to drive the expression of both genes simultaneously in the presence of GAL4-VP16. When CMV-hrl is compared with the bidirectional system, there is 2-fold lower hRL activity in the case of the latter (p = 0.005). However, when compared with CMV-fl, fl expression is about 3- to 4-fold lower (p = 0.003) in the case of the bidirectional system. A comparison of fl gene activity with the unidirectional TSTA system (G5-fl) (Iyer et al., 2001) reveals about a 3- to 4-fold drop with the bidirectional model (p < 0.01). To determine whether the results are consistent across cell lines, similar experiments were repeated in other mammalian cell lines (HeLa and 293T). Similar results were obtained in both cell lines, with 293T cells showing the highest expression levels of both genes. These results indicate that the bidirectional system can cause significant amplification in the expression of both genes simultaneously in the presence of the trans-activator, and that the results are reproducible across several cell lines.

FIG. 2.

The bidirectional system mediates simultaneous expression of both fl (A) and hrl (B) genes. N2a cells were transiently transfected with water (mock), activator plasmid alone (VP16), reporter plasmid alone (fl-G5-hrl), CMV-fl, CMV-hrl, Unidirectional fl TSTA system (G5fl+VP16), or both reporter and activator (fl-G5-hrl+VP16). The cells were harvested 24 hr after transfection and assayed for FL and hRL activity. Error bars represent the SEM for triplicate measurements.

Linearly increasing levels of fl and hrl expression are observed in N2a cells transfected with increasing doses of activator plasmid when the dose of reporter plasmid is kept constant

To confirm that the levels of expression of the reporter genes increase in accordance with increasing levels of the activator protein GAL4-VP16, we transfected N2a cells with increasing doses of VP16 (0–0.75 μg/well) along with a constant dose of the reporter plasmid (0.5 μg/well). Cells transfected with only the reporter plasmid were used as the control. We observed a linear increase in hRL and FL enzyme activities up to 0.75 μg/well (Fig. 3A and B). Thus within a 0- to 0.75-μg/well dose of the activator plasmid both FL and hRL activities correlate well with the amount of the activator protein (r2 = 0.98 and 0.90, respectively).

FIG. 3.

Linear increase in gene expression with increasing doses of the activator plasmid. (A) and (B) show the linear increase in expression of the hrl and fl genes, respectively, as the activator plasmid (VP16) dose is increased from 0 to 0.75 μg/well while the dose of reporter plasmid is maintained at 0.5 μg/well. Seen here are high correlations (r2 = 0.90 and 0.98 for hrl and fl, respectively) between the dose of activator plasmid used for transfection and protein activities. The results were obtained 24 hr after transfection in N2a cells. Error bars indicate the SEM for triplicate measurements. (C) Correlation between hrl and fl expression in N2a cells transfected with various doses of VP16 and a constant dose of fl-G5-hrl. The correlation is r2 = 0.94.

The bidirectional reporter system produces highly correlated expression of two independent reporter genes in cell culture studies

To determine in cell culture whether the expression of a reporter gene can be used to estimate the expression of a linked transgene, using the current strategy, we cotransfected N2a (0–0.75 μg/well), HeLa (0–0.75 μg/well), and 293T (0–0.8 μg/well) cells with various doses of the activator plasmid and a constant dose (0.5 μg/well) of the reporter plasmid. After 24 hr of transfection the cell lysates were collected and assayed for FL and hRL enzyme activities. Figure 3C illustrates correlation between the activities of the two luciferases stated as average relative light units (RLU) per microgram of protein. Regression analysis shows high correlation (r2 = 0.94) between the FL and hRL activities in N2a cells. High correlations are also seen in the case of HeLa (r2 = 0.98) and 293T cells (r2 = 0.92) (data not shown).

Expression of both reporter genes increases linearly and in a highly correlated fashion in cells transfected with various doses of the reporter plasmid while keeping the dose of the activator plasmid constant

To see whether the results were reproducible if the dose of the reporter component of the system was changed while keeping the activator component constant, we repeated the transfection studies with multiple doses of the reporter plasmid (0–0.75 μg/well) while the amount of the activator plasmid was kept constant at 0.5 μg/well in N2a cells. The FL and hRL activities again increased linearly with increasing doses of the reporter as revealed by regression analysis (Fig. 4A and B) (r2 = 0.98 and 0.96, respectively). The activities of both genes were also highly correlated (r2 = 0.99) (Fig. 4C). The results were also reproducible in both HeLa and 293T cells (r2 = 0.95 and 0.98, respectively), although in the latter case the level of expression was much higher (data not shown).

FIG. 4.

Linear increase in gene expression with increasing levels of reporter plasmid. (A) and (B) show the linear relationship between the expression of fl (A) and hrl (B) genes and the dose of the reporter plasmid (fl-G5-hrl) (0–0.75 μg/well) while the dose of the activator plasmid was maintained at 0.5 μg/well. Seen here are high correlations (r2 = 0.96 and 0.98 for hrl and fl, respectively) between the dose of reporter plasmid used for transfection and protein activities. The results were obtained 24 hr after transfection in N2a cells. Error bars indicate the SEM for triplicate measurements. (C) Correlation between hrl and fl expression in N2a cells transfected with various doses of fl-G5-hrl and a constant dose of VP16. The correlation is r2 = 0.99.

Amplified expression levels of optical reporter genes fl and hrl can be imaged in individual living animals and are highly correlated

We next examined whether the GAL4-responsive bidirectional reporter system can regulate expression of both fl and hrl in cells implanted and imaged in living animals. N2a cells were cotransfected with various doses of the activator plasmid and a constant dose of the reporter plasmid in six-well plates. The dose of the reporter plasmid was maintained at 0.67 μg/well while the activator dose was varied (10, 50, 100, and 150% of the reporter [fl-G5-hrl] dose). Cells were harvested after 24 hr and 1 × 106 cells were implanted separately at four different sites in each of three male nude mice. The mice were then scanned with the cooled CCD camera to image the activities of the luciferases from each site. The mice were first scanned after tail vein injection of coelenterazine. Five hours later the mice were scanned again after an intraperitoneal injection of D-luciferin. There is a linear increase in the expression levels of both genes across mice for the dose range tested (Fig. 5A). Furthermore, the expression levels of both reporter genes, measured as ROI values (maximum photons/cm2/sec/steradian) for each implantation site is well correlated (r2 = 0.82) in living mice (Fig. 5B).

FIG. 5.

(A) Optical CCD imaging of a mouse carrying N2a cells transiently cotransfected with a constant dose of fl-G5-hrl and various doses of the activator plasmid VP16 implanted subcutaneously at four different sites. Sites A–D indicate cells transfected with various doses of VP16 in increasing order. Both images shown are from the same mouse and are formed by superimposing visible light images on the optical CCD bioluminescence image with a scale depicting photons/cm2/sec/steradian (sr). Mice were imaged after tail vein injection of coelenterazine (left) and after intraperitoneal injection of D-luciferin (right). (B) Correlation of fl and hrl gene expression from three mice optically imaged with cells cotransfected with different doses of the activator plasmid (VP16) and a constant dose of the reporter plasmid (fl-G5-hrl). Shown is a plot of hRL activity versus FL activity, expressed as maximum photons/cm2/sec/sr, obtained from ROIs drawn over the implantation sites on the mouse images (r2 = 0.82, n = 3 mice).

Next, we wanted to test the efficacy of this amplification system in a real gene therapy application. For this purpose we injected the components of this system in a 1:1 ratio (10 μg of each of the plasmids) by the method of hydrodynamic injection into the tail vein of living mice. Naked DNAs delivered by this process are delivered to the liver, where they tend to transfect the liver hepatocytes in vivo with high efficiency (Zhang et al., 1999). We wanted to test whether our system would be able to produce detectable expression of the two reporter genes and also retain the high degree of correlation between the gene expression levels in the hepatocytes transfected in vivo by this technique. Indeed, we could detect robust expressions of both fl and hrl reporter genes in the liver regions of the animals within 6 hr of hydrodynamic injection and expression was still high even 24 hr after the injection (Fig. 6A). Most importantly, the level of expression of the hrl gene is also well correlated (r2 = 0.66) with that of the fl gene in living mice (n = 11) (Fig. 6B).

FIG. 6.

(A) Optical CCD imaging of a mouse injected hydrodynamically with 10 μg each of activator (VP16) and reporter plasmid (fl-G5-hrl) 24 hr before imaging. Both images shown are from the same mouse and are formed by superimposing visible light images on the optical CCD bioluminescence image with a scale depicting photons/cm2/sec/sr. Mice were imaged after tail vein injection of coelenterazine (40 μg; left) and after intraperitoneal injection of D-luciferin (3 mg; right). (B) Correlation of fl and hrl gene expression from mice optically imaged after the injection of 10 μg each of the activator plasmid (VP16) and the reporter plasmid (fl-G5-hrl). Shown is a plot of hRL activity versus FL activity, expressed as maximum photons/cm2/sec/sr, obtained from same-sized ROIs drawn over the liver region on the mouse images (r2 = 0.66, n = 11 mice).

DISCUSSION

This article reports initial results from experiments in which a novel GAL4-responsive bidirectional vector was used to amplify the expression of two reporter genes simultaneously both in cell culture and in living animals. This system should help to amplify the expression of a gene of interest from a weak tissue-specific promoter and to determine the spatial location and level of expression of the target gene repeatedly, with the help of the highly correlated expression of a tightly coupled reporter gene. This approach can be made fully quantitative and tomographic by simply replacing the optical reporter gene with a PET reporter gene.

We have previously demonstrated that the TSTA strategy can be used to amplify the expression of a single reporter gene from a weak tissue-specific promoter in a prostate-specific manner in living mice (Iyer et al., 2001). We have been evaluating ways to develop this system as a potential gene therapy vector. Accordingly, we decided to design a bidirectional system based on the TSTA model that will link a therapeutic gene with an imaging reporter gene, so that, as stated previously, by simply studying the reporter gene noninvasively we can estimate the magnitude of expression of our target gene of interest and also monitor its location. Such a system may also be useful in transgenic animal applications, where the expression of the gene of interest can be repeatedly monitored in an intact animal.

In the present study we observed that expression from both coding regions was significantly elevated and retained a high level of correlation. Our data demonstrate that the hRL signal resulting from translation of the forward hrl gene in the bidirectional reporter vector can be used to quantify the level of expression of the fl gene in living animals. However, there was apparently a significant attenuation of the fl gene placed in a reverse orientation to the GAL4-binding sites in the vector. Despite this, we could observe robust signal from the fl gene both in cell culture and in vivo. Most importantly, we also obtained a high correlation between the expression levels of the two reporter genes both in cell culture (r2 = 0.95) and in living animals (r2 = 0.82 and 0.66), using bioluminescence imaging.

The naked DNA experiments were performed to test the efficacy of the system developed in a real gene therapy application, in which the different components of this system will be delivered in vivo by means of different nonviral or viral vectors and will be required to transfect the cells of the animal in situ. Earlier studies have shown that efficient plasmid delivery to the liver can be achieved via a hydrodynamically based procedure involving rapid tail vein injection of a large volume of DNA solution (Liu and Knapp, 2001; Herweijer and Wolff, 2003). This method is being widely utilized by gene therapy researchers to evaluate the therapeutic activities of various genes (Zhang et al., 2004). We decided to adopt this method to transfect hepatocytes in vivo with both activator and reporter plasmids and then study whether the correlation was still maintained between the levels of expression of the two genes. We obtained a good level of correlation between the two reporter genes (r2 = 0.66), similar to what was seen in the xenograft studies. These results support the robustness of our system. However, in contrast to the xenograft studies, in the naked DNA experiments we had to administer a higher dose of coelenterazine to obtain a detectable signal for the hrl reporter gene. This was expected because Renilla luciferase is known to produce blue-shifted light (475 nm) that is largely attenuated while traveling from a deep tissue environment like the liver. Apart from this there could be other parameters that regulate the delivery of the substrate coelenterazine to the transfected hepatocytes, such as the hepatic circulation and the presence of P-glycoproteins (Ros et al., 2003; Pichler et al., 2004). All these factors can also be influential in achieving a lower correlation compared with subcutaneous tumor studies, in which the source of light has a superficial location.

The bidirectional system showed a 3- to 4-fold lower expression of the fl gene when compared with a well-established reporter system, CMV-fl, and a 2- to 3-fold lower signal of the forward hrl gene when compared with CMV-hrl. An earlier TSTA system also showed a 2- to 3-fold lower signal from a SV40-GAL4-VP16-activated unidirectional G5-fl vector when compared with CMV-fl (Iyer et al., 2001). Thus a reduced signal from the forward hrl gene when compared with CMV-hrl is in accordance with previous results. Previous studies have validated that 5×GAL4-binding sites are optimal for one promoter (Emami and Carey, 1992; Iyer et al., 2001; Zhang et al., 2002). Thus it could be possible that the inclusion of an additional promoter might compete with the available GAL4-VP16 activator proteins, thereby resulting in a reduction of overall activities of both promoters. However, we are unable to explain the phenomenon causing a greater attenuation of the expression level of the reverse gene. On the basis of other studies (Ross et al., 2000; Dion and Coulombe, 2003) it seems unlikely that this effect is related to the orientation of the GAL4-DNA-binding domains. It has been observed that the ability of GAL4-VP16 to activate transcription varies 1- to 2-fold with 2- to 8-bp variations in the spatial positioning of the DNA-bound activation domain from the TATA box of the promoter (Ross et al., 2000). Thus it is possible that slight dissimilarities in the spacer distances between the individual E4TATA minimal promoters and the GAL4-binding sites in the reporter plasmid can impart differential transcriptional abilities to the promoters, resulting in turn in differential expression of the genes they activate. Uneven spacer distances between the coding sequences of the two genes and their minimal promoters may also cause this effect. In our vector system the reverse fl gene is 30 bp away from its E4TATA minimal promoter, whereas the forward hrl gene is only 10 bp away. We are currently trying to test these possibilities by simply switching the positions of the two genes and repeating the experiments with the new reporter vector. Nonetheless, our initial results indicate for the first time that the TSTA strategy can be developed into a potent bidirectional system that can successfully achieve amplification of two independent genes, simultaneously. There are several ways we can try to reduce the attenuation of the reverse gene and make the system more robust. These include (1) optimization of the number of GAL4-binding sites for two promoters, (2) optimization of the spacer distance between the genes and the minimal promoter, (3) optimization of the spacer distance between the minimal promoter and the GAL4-binding sites, and (4) use of a more potent transcriptional activator that contains two activator domains of VP16 fused to the GAL4-DNA-binding domain (GAL4-VP2) (Zhang et al., 2002).

We have observed a linear increase in the levels of expression of both genes as we increased the dose of the activator. However, the relationship may not hold true at higher concentrations of the activator, as earlier studies have shown attenuation of gene expression in the presence of excess GAL4-VP16 (“squelching”) (Gill and Ptashne, 1988). We also observed that the bidirectional vector is somewhat leaky before being activated by GAL4-VP16; however, this leakiness gave rise to minimal background levels in both cell and animal studies.

Because it is important that any reporter gene-imaging approach not significantly perturb the cell or the animal models being studied we decided to do a dose–response study with various doses of the activator plasmid in various mammalian cell lines. Among the mammalian cell lines tested only transiently transfected 293T cells showed some levels of cytotoxicity at the highest dose (0.75 μg/well) used. Such effects were not observable in N2a or HeLa cells. But because low levels of GAL4-VP16 were practically nondeleterious to the cells and still produced significant amplification of gene expression, we think that this system will be satisfactorily nontoxic. However, further studies with stable cell lines, gene therapy vectors, and transgenic animal models will help in the characterization of the potential toxicities of the current approach.

The bidirectional reporter system has many advantages over other, alternative systems. A fusion protein approach has the disadvantage of not being generalizable, because for every new therapeutic gene the fusion approach would have to be validated. This approach has an advantage over the bicistronic IRES strategy because, unlike the IRES, this system is not likely to be affected by physiological stress (such as heat shock, hypoxia, and poisoning) that can confound the quantitation (Sun et al., 2001). Approaches to deliver reporter and therapeutic genes via separate vectors require a higher viral dose leading to a potentially overwhelming immune response and possible disengagement of reporter gene and therapeutic gene expression at the single-cell level (Yaghoubi et al., 2001).

The bidirectional vector system can be combined in a single-vector system and eventually used in a multitude of gene therapy studies. Apart from facilitating the repeated imaging of the location(s), magnitude, and time variation of the reporter gene expression, this system can also help in the quantification of therapeutic and “suicide” genes. The high correlation power of this model will help immensely in the application of reporter gene technology to animals and humans, thereby advancing research in multiple fields including the monitoring of human gene therapy (Yu et al., 2000). A system like this will also be useful for studying tumor growth and regression after pharmacological intervention, studying protein–protein interactions (Paulmurugan et al., 2002; Ray et al., 2002; Paulmurugan and Gambhir, 2003), and developing model gene therapy vectors for monitoring site-specific delivery and expression of transgenes.

OVERVIEW SUMMARY.

Tissue-specific promoters frequently used for tissue-specific delivery of therapeutic genes in gene therapy applications are limited by their weak transcriptional ability. To overcome this drawback the two-step transcriptional amplification (TSTA) strategy was designed to enhance the promoter strengths of such weak tissue-specific promoters. Here, we report on the engineering, functional characterization, and in vivo application of a bidirectional TSTA system that will allow us to simultaneously amplify the expression of a therapeutic gene and that of a tightly coupled reporter gene. We demonstrate that such a bidirectional TSTA system will also be helpful in quantifying the amplified expression of the therapeutic gene simply by studying the highly correlated expression of the tightly coupled reporter gene.

Acknowledgments

We thank Xioaman Lewis (Crump Institute of Molecular Imaging, UCLA), Qian Wang (Stanford University), and Kim Le (Department of Biological Chemistry, UCLA) for assistance with this project. This work is supported in part by NIH grants R01 CA82214 and SAIRP R24 CA92865, Department of Energy contract DE-FC03-87ER60615, and CaP Cure.

References

- BARON U, FREUNDLIEB S, GOSSEN M, BUJARD H. Coregulation of two gene activities by tetracycline via a bidirectional promoter. Nucleic Acids Res. 1995;23:3605–3606. doi: 10.1093/nar/23.17.3605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BHAUMIK S, GAMBHIR SS. Optical imaging of Renilla luciferase reporter gene expression in living mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002a;99:377–382. doi: 10.1073/pnas.012611099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BHAUMIK S, GAMBHIR SS. Simultaneous imaging of the expression of two bioluminescent reporter genes in living mice. Mol Ther. 2002b;5:S422. [Google Scholar]

- BLAKE P, JOHNSON B, VANMETER JW. Positron emission tomography (PET) and single photon emission computed tomography (SPECT): Clinical applications. J Neuroophthalmol. 2003;23:34–41. doi: 10.1097/00041327-200303000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CHAPPELL SA, EDELMAN GM, MAURO VP. A 9-nt segment of a cellular mRNA can function as an internal ribosome entry site (IRES) and when present in linked multiple copies greatly enhances IRES activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:1536–1541. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.4.1536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CONTAG CH, BACHMANN MH. Advances in in vivo bioluminescence imaging of gene expression. Annu Rev Biomed Eng. 2002;4:235–260. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bioeng.4.111901.093336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CONTAG CH, ROSS BD. It’s not just about anatomy: In vivo bioluminescence imaging as an eyepiece into biology. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2002;16:378–387. doi: 10.1002/jmri.10178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DION V, COULOMBE B. Interactions of a DNA-bound transcriptional activator with the TBP-TFIIA-TFIIB-promoter quaternary complex. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:11495–11501. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M211938200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ECKELMAN WC, TATUM JL, KURDZIEL KA, CROFT BY. Quantitative analysis of tumor biochemistry using PET and SPECT. Nucl Med Biol. 2000;27:633–635. doi: 10.1016/s0969-8051(00)00163-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- EMAMI KH, CAREY M. A synergistic increase in potency of a multimerized VP16 transcriptional activation domain. EMBO J. 1992;11:5005–5012. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1992.tb05607.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GAMBHIR SS, BARRIO JR, WU L, IYER M, NAMAVARI M, SATYAMURTHY N, BAUER E, PARRISH C, MACLAREN DC, BORGHEI AR, GREEN LA, SHARFSTEIN S, BERK AJ, CHERRY SR, PHELPS ME, HERSCHMAN HR. Imaging of adenoviral-directed herpes simplex virus type 1 thymidine kinase reporter gene expression in mice with radiolabeled ganciclovir. J Nucl Med. 1998;39:2003–2011. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GAMBHIR SS, BAUER E, BLACK ME, LIANG Q, KOKORIS MS, BARRIO JR, IYER M, NAMAVARI M, PHELPS ME, HERSCHMAN HR. A mutant herpes simplex virus type 1 thymidine kinase reporter gene shows improved sensitivity for imaging reporter gene expression with positron emission tomography. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:2785–2790. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.6.2785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GILL G, PTASHNE M. Negative effect of the transcriptional activator GAL4. Nature. 1988;334:721–724. doi: 10.1038/334721a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HERWEIJER H, WOLFF JA. Progress and prospects: naked DNA gene transfer and therapy. Gene Ther. 2003;10:453–458. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3301983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- IYER M, WU L, CAREY M, WANG Y, SMALLWOOD A, GAMBHIR SS. Two-step transcriptional amplification as a method for imaging reporter gene expression using weak promoters. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:14595–14600. doi: 10.1073/pnas.251551098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LAMMERTSMA AA. PET/SPECT: Functional imaging beyond flow. Vision Res. 2001;41:1277–1281. doi: 10.1016/s0042-6989(00)00262-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LIU D, KNAPP JE. Hydrodynamics-based gene delivery. Curr Opin Mol Ther. 2001;3:192–197. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LUKER GD, PIWNICA-WORMS D. Molecular imaging in vivo with PET and SPECT. Acad Radiol. 2001;8:4–14. doi: 10.1016/s1076-6332(03)80738-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MASSOUD TF, GAMBHIR SS. Molecular imaging in living subjects: seeing fundamental biological processes in a new light. Genes Dev. 2003;17:545–580. doi: 10.1101/gad.1047403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NEGRIN RS, EDINGER M, VERNERIS M, CAO YA, BACHMANN M, CONTAG CH. Visualization of tumor growth and response to NK-T cell based immunotherapy using bioluminescence. Ann Hematol. 2002;81(Suppl 2):S44–S45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NETTELBECK DM, JEROME V, MULLER R. A strategy for enhancing the transcriptional activity of weak cell type-specific promoters. Gene Ther. 1998;5:1656–1664. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3300778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NETTELBECK DM, JEROME V, MULLER R. Gene therapy: Designer promoters for tumour targeting. Trends Genet. 2000;16:174–181. doi: 10.1016/s0168-9525(99)01950-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PAULMURUGAN R, GAMBHIR SS. Monitoring protein–protein interactions using split synthetic Renilla luciferase protein-fragment-assisted complementation. Anal Chem. 2003;75:1584–1589. doi: 10.1021/ac020731c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PAULMURUGAN R, UMEZAWA Y, GAMBHIR SS. Noninvasive imaging of protein–protein interactions in living subjects by using reporter protein complementation and reconstitution strategies. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:15608–15613. doi: 10.1073/pnas.242594299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PICHLER A, PRIOR JL, PIWNICA-WORMS D. Imaging reversal of multidrug resistance in living mice with bioluminescence: MDR1 P-glycoprotein transports coelenterazine. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:1702–1707. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0304326101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- QIAO J, DOUBROVIN M, SAUTER BV, HUANG Y, GUO ZS, BALATONI J, AKHURST T, BLASBERG RG, TJUVAJEV JG, CHEN SH, WOO SL. Tumor-specific transcriptional targeting of suicide gene therapy. Gene Ther. 2002;9:168–175. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3301618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RAY P, BAUER E, IYER M, BARRIO JR, SATYAMURTHY N, PHELPS ME, HERSCHMAN HR, GAMBHIR SS. Monitoring gene therapy with reporter gene imaging. Semin Nucl Med. 2001;31:312–320. doi: 10.1053/snuc.2001.26209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RAY P, PIMENTA H, PAULMURUGAN R, BERGER F, PHELPS ME, IYER M, GAMBHIR SS. Noninvasive quantitative imaging of protein–protein interactions in living subjects. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:3105–3110. doi: 10.1073/pnas.052710999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RAY P, WU AM, GAMBHIR SS. Optical bioluminescence and positron emission tomography imaging of a novel fusion reporter gene in tumor xenografts of living mice. Cancer Res. 2003;63:1160–1165. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ROS JE, LIBBRECHT L, GEUKEN M, JANSEN PL, ROSKAMS TA. High expression of MDR1, MRP1, and MRP3 in the hepatic progenitor cell compartment and hepatocytes in severe human liver disease. J Pathol. 2003;200:553–560. doi: 10.1002/path.1379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ROSS ED, KEATING AM, MAHER LJ., III DNA constraints on transcription activation in vitro. J Mol Biol. 2000;297:321–334. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.3562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SHARMA V, LUKER GD, PIWNICA-WORMS D. Molecular imaging of gene expression and protein function in vivo with PET and SPECT. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2002;16:336–351. doi: 10.1002/jmri.10182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SUN X, ANNALA AJ, YAGHOUBI SS, BARRIO JR, NGUYEN KN, TOYOKUNI T, SATYAMURTHY N, NAMAVARI M, PHELPS ME, HERSCHMAN HR, GAMBHIR SS. Quantitative imaging of gene induction in living animals. Gene Ther. 2001;8:1572–1579. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3301554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SUNDARESAN GG, GAMBHIR SS. Radionuclide imaging of reporter gene expression. In: Toga AW, Mazziotta JC, editors. Brain Mapping: The Methods. 2. Academic Press; San Diego, CA: 2002. pp. 799–818. [Google Scholar]

- WANG YAGS. New approaches for linking PET and therapeutic reporter gene expression for imaging gene therapy with increased sensitivity. Presented at the Society for Nuclear Medicine Meeting; Toronto, ON, Canada. 2001. [Google Scholar]

- WEBER WA, HAUBNER R, VABULIENE E, KUHNAST B, WESTER HJ, SCHWAIGER M. Tumor angiogenesis targeting using imaging agents. Q J Nucl Med. 2001;45:179–182. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- YAGHOUBI SS, WU L, LIANG Q, TOYOKUNI T, BARRIO JR, NAMAVARI M, SATYAMURTHY N, PHELPS ME, HERSCHMAN HR, GAMBHIR SS. Direct correlation between positron emission tomographic images of two reporter genes delivered by two distinct adenoviral vectors. Gene Ther. 2001;8:1072–1080. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3301490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- YU Y, ANNALA AJ, BARRIO JR, TOYOKUNI T, SATYAMURTHY N, NAMAVARI M, CHERRY SR, PHELPS ME, HERSCHMAN HR, GAMBHIR SS. Quantification of target gene expression by imaging reporter gene expression in living animals. Nat Med. 2000;6:933–937. doi: 10.1038/78704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ZHANG G, GAO X, SONG YK, VOLLMER R, STOLZ DB, GASIOROWSKI JZ, DEAN DA, LIU D. Hydroporation as the mechanism of hydrodynamic delivery. Gene Ther. 2004;11:675–682. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3302210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ZHANG L, ADAMS JY, BILLICK E, ILAGAN R, IYER M, LE K, SMALLWOOD A, GAMBHIR SS, CAREY M, WU L. Molecular engineering of a two-step transcription amplification (TSTA) system for transgene delivery in prostate cancer. Mol Ther. 2002;5:223–232. doi: 10.1006/mthe.2002.0551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ZHANG W, CONTAG PR, MADAN A, STEVENSON DK, CONTAG CH. Bioluminescence for biological sensing in living mammals. Adv Exp Med Biol. 1999;471:775–784. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4615-4717-4_89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]