Abstract

Objective

This systematic review aimed to evaluate the level of evidence of contemporary peer-reviewed literature published from 2004–2011 on the psychosocial impact of lymphedema.

Methods

Eleven electronic databases were searched and 1,311 articles retrieved; 23 met inclusion criteria. Twelve articles utilized qualitative methodology and 11 employed quantitative methodology. An established quality assessment tool was used to assess the quality of the included studies.

Results

The overall quality of the 23 included studies was adequate. A critical limitation of current literature is the lack of conceptual or operational definitions for the concept of psychosocial impact. Quantitative studies showed statistically significant poorer social well-being in persons with lymphedema, including perceptions related to body image, appearance, sexuality, and social barriers. No statistically significant differences were found between persons with and without lymphedema in the domains of emotional well-being (happy or sad) and psychological distress (depression and anxiety). All 12 of the qualitative studies consistently described negative psychological impact (negative self-identity, emotional disturbance, psychological distress) and negative social impact (marginalization, financial burden, perceived diminished sexuality, social isolation, perceived social abandonment, public insensitivity, non-supportive work environment). Factors associated with psychosocial impact were also identified.

Conclusions

Lymphedema has a negative psychosocial impact on affected individuals. The current review sheds light on the conceptualization and operationalization of the definitions of psychosocial impact with respect to lymphedema. Development of a lymphedema-specific instrument is needed to better characterize the impact of lymphedema and to examine the factors contributing to these outcomes in cancer and non-cancer-related populations.

Keywords: Lymphedema, Psychosocial, Systematic review, Psychological distress, Cancer, Oncology

Introduction

Lymphedema is a prevalent and potentially debilitating chronic condition affecting more than 3 million people in the US[1]. While the majority of cases are known to be related to cancer treatment, the actual number of people affected by cancer or non-cancer-related lymphedema is unknown. Cancer-related lymphedema, a syndrome of abnormal swelling and multiple symptoms, is the result of obstruction or disruption of the lymphatic system associated with cancer treatment (e.g., axillary surgery and/or radiotherapy), influenced by patient personal factors (e.g., obesity), and triggered by factors such as infections or trauma [1–3]. While up to 40% of the 2.5 million breast cancer survivors have developed this condition, lymphedema also affects a large proportion of survivors with other malignancies, including melanoma (16%), gynecological (20%), genitourinary (10%), head/neck (4%) cancer [4]. Additionally, secondary lymphedema may occur due to non cancer causes, such as trauma or infection, and primary lymphedema may occur due to intrinsic factors, such as familial or genetic factors.

It is well documented that lymphedema and associated symptoms (e.g., swelling, heaviness, tightness, firmness, pain, numbness, stiffness, or impaired limb mobility) exert a negative impact on physical and functional well-being, resulting in diminished overall health-related quality of life (HR-QOL) [5,6]. Psychological distress, such as anxiety and depression from perceived abandonment by healthcare professionals, and marginalization among breast cancer survivors with lymphedema have also been reported [7–10]. Recent research reports that breast cancer survivors with lymphedema utilized more psychological counseling services than breast cancer survivors without lymphedema [8].

Early quantitative research that reported psychosocial consequences of lymphedema were specifically designed to evaluate HR-QOL among individuals with lymphedema. However, psychosocial impact was not conceptually and operationally defined in these early studies [6,9,10]. HR-QOL has been described as the effect that a medical condition or its treatment has on a person [11–12]. Most HR-QOL measures operationally define quality of life based on the World Health Organization’s definition, denoting that quality of life is a multidimensional concept, incorporated in the complexity of the person’s physical health, psychological status, level of independence, beliefs, and social and personal relationships [13]. Accordingly, HR-QOL assessment tools usually assess the following domains of well-being: emotional, psychological, social, physical, or functional [11]. Since a number of HR-QOL instruments have subscales which specifically assess emotional and social well-being, the use of HR-QOL measures, such as the Psychosocial Adjustment to Illness Scale-Self-Report (PAIS), the 36-Item Short-Form Health Survey (SF-36 or SF-12), and the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy–Breast (FACT-B) scale [6,9,10], permitted early research to report the psychosocial consequences of lymphedema. For example, Woods [10] used the PAIS to assess psychosocial adjustment to breast-cancer-related lymphedema in 37 patients and found that the patients’ average score for the PAIS was within normal limits. Based on these results, the author concluded that the women in the study had adequate psychosocial adjustment to their post-breast cancer lymphedema. Velanovich and Szymanski [6] used the SF-36 to evaluate the impact of lymphedema among 827 breast cancer survivors; 68 of these patients had clinically apparent lymphedema. Breast cancer survivors with lymphedema in the study reported statistically lower median scores in the emotional domain and a statistically higher percentage of the women with lymphedema had poorer overall mental health scores. Beaulac [9] used the FACT-B+4 to assess the psychosocial impact of lymphedema in 151 patients with breast cancer. Those with lymphedema had lower total FACT-B scores in comparison to those without lymphedema (p<.001). Additionally, emotional well-being scores from the FACT-B were lower for those with lymphedema, as compared to those without (p<0.01). These researchers concluded that moderate lymphedema could have significant impact on women’s emotional well-being.

The use of HR-QOL instruments to assess the psychosocial impact of a medical condition [6,9–10] contributes to difficulty in assimilating results and drawing conclusions, as there may be overlap across the dimensions or lack of items to assess a given domain sufficiently. For example, recent research showed that the SF-36 had relatively weak discriminative power with respect to emotional well-being, failing to demonstrate mental health differences among breast cancer survivors with lymphedema and those without lymphedema [14]. This may be due to SF-36’s limited coverage of mental health symptoms since the SF-36 contains only two items addressing anxiety and three items assessing depression.

With the increased awareness that HR-QOL is not an ideal proxy measure for the assessment of psychosocial issues related to lymphedema [14], more recently investigators have attempted to use a variety of methods and instruments to identify the nature, severity, and prevalence of the psychosocial impact of lymphedema. For example, instruments such as the Profile of Mood States questionnaire (POMS-SF) [15] and Center for Epidemiologic Studies of Depression [16] scale have been used to assess the psychological concerns in patients with lymphedema and qualitative methodologies have been employed to solicit descriptions directly from patients related to the psychosocial impact of lymphedema [17–18].

This systematic review was aimed to evaluate the level of evidence of contemporary peer-reviewed literature published from January 2004 to December 2011. Because to date there has been an overall lack of a specific conceptual and operational definition of psychosocial impact to guide this systematic review, the authors defined the psychosocial impact of lymphedema based on Mosby's Medical Dictionary [19] as a combination of psychological and social factors that directly affect an individual with lymphedema. Based on existing literature, the definition was operationalized to include the psychological factors/concerns including emotion or mood, depression, anxiety, mental distress, or fear, as well as social factors to including stigma, lack of healthcare coverage, social isolation/withdrawal, marginalization, and social support. Specifically, this review was intended to answer the following questions:

What is the psychosocial impact of lymphedema? (RQ#1)

Which factors are associated with the psychosocial impact of lymphedema? (RQ#2)

Methods

Literature Search and Inclusion Criteria

The literature search identified research articles that examined the psychosocial impact of lymphedema and that were published in peer-reviewed journals. The inclusion criteria for the topical review were research studies that either:

used instruments to evaluate the psychosocial impact of lymphedema or studies which assessed psychological, emotional, and social domain using HR-QOL instruments. (RQ#1)

used qualitative approaches to describe and understand the psychosocial impact of lymphedema. (RQ# 1&2)

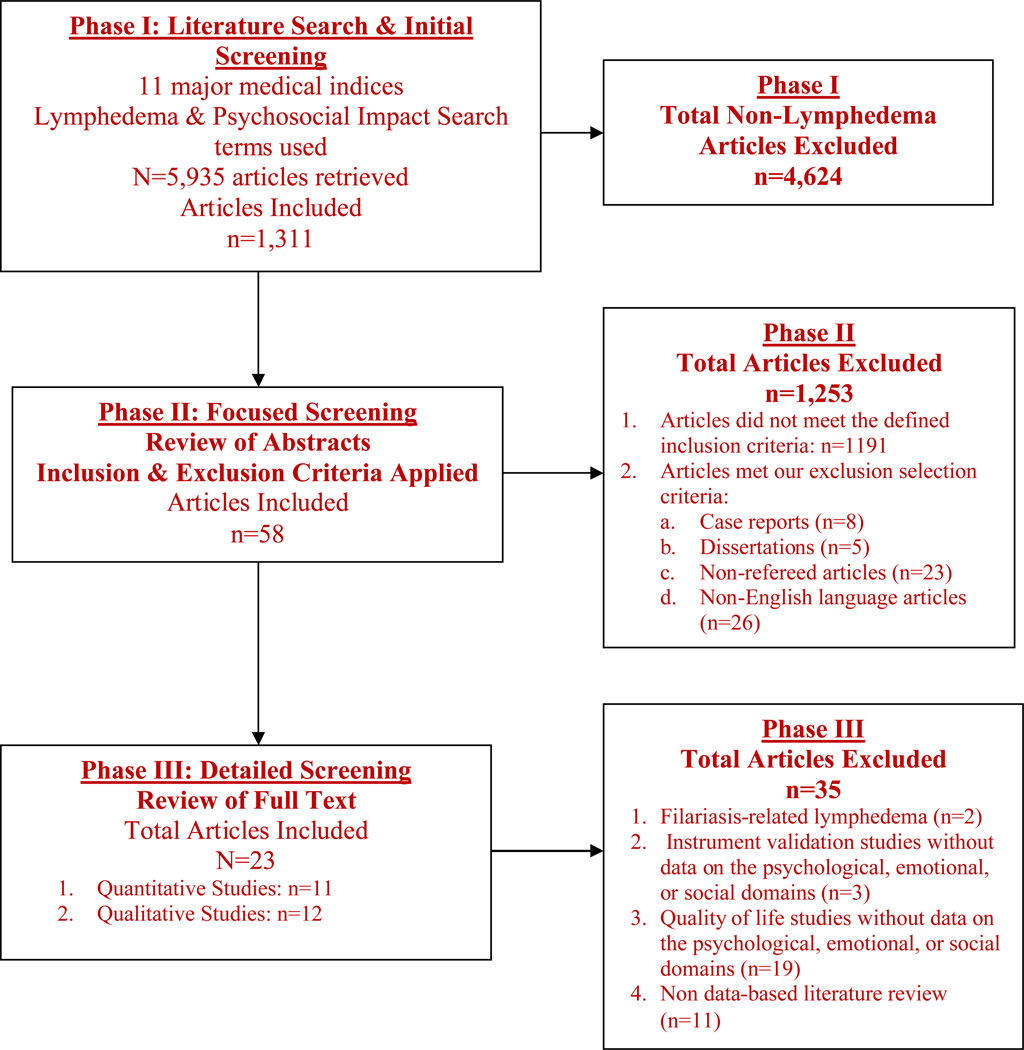

identified factors associated with the psychosocial impact of lymphedema. (RQ#2) The review was conducted over three phases. In Phase I, a research librarian performed

the initial searches using the terms “lymphedema,” “lymphodema,” “lymphoedema,” “elephantiasis,” “swelling,” “edema,” and “oedema” to capture all literature potentially related to lymphedema (2004–2011). The terms were applied to 11 major medical indices: PubMed, MEDLINE, CINAHL, Cochrane Library databases (Systematic Reviews and Controlled Trials Register), PapersFirst, ProceedingsFirst, Worldcat, PEDro, National Guidelines Clearing House, ACP Journal Club, and Dare. The search terms were then expanded to cover all literature related to the key concept of psychosocial impact by applying the following terms to the above 11 databases: (a) general terms such as “psychosocial impact,” “psychosocial consequences,” “psychosocial concerns,” or “quality of life;” (b) specific terms related to psychological impact such as “psychological distress,” “depression,” “anxiety,” “fear,” “mood/mood disturbance,” or “emotional disorder/disturbance;” and (c) specific terms related to social impact such as “marginalization,” “stigma,” “lack of healthcare coverage,” “social isolation”, “social withdrawal,” “social support,” “providers’ support,” “interpersonal relationship,” “sexuality,” “sexual relationship,” or “intimate relationship.”

A total of 5,935 articles were retrieved; 4,624 articles were excluded by research associates because they did not pertain to lymphedema. In Phase II, the first three authors reviewed the abstracts of the remaining 1,311 articles; 1,253 articles were excluded because they did not meet the defined inclusion criteria (n=1191) or because of our selection criteria that excluded case reports (n=8), dissertations (n=5), non-refereed articles (n=23), and non-English language articles (n=26). In Phase III, the first three authors reviewed the full text of the remaining 58 articles and excluded studies that: (1) investigated filariasis-related lymphedema (n=2); (2) were instrument validation studies and did not provide data on the psychological, emotional, or social domains (n=3); (3) were QOL studies that reported only overall scores for QOL but did not report scores for the psychological, emotional, or social domains (n=19); and (4) non data-based literature review (n=11). A total of 23 studies met inclusion for this review. Please see Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Literature Review and Screening Process for Psychosocial Impact of Lymphedema Systematic Review of Literature (2004–2011)

Assessing the Quality of the Included Studies

To assess the quality of the included studies, a validated assessment tool was used to quantify the rigor of the studies [20–24]. We adapted an established quality assessment tool using a 16-item index to evaluate the quality of each included article (Table 1)[20–24]. The quality assessment tool, with two items specifically for quantitative and qualitative studies, allows for consistent inter-rater reliability between ratings for both quantitative and qualitative studies [24]. Each article was assessed and scored independently by the first three authors, with one point assigned for each criterion fulfilled according to the adapted 16-item index (Table 1). Score discrepancies were resolved through group consultation and consensus. All criteria were equally weighted and the higher score indicated higher quality of a study with a total potential affirmative score of 14. For this systematic review, studies that received an affirmative score of at least 10 out of 14 were considered to have adequate quality. Similar adaptations of this instrument have been used in systematic reviews of the psychosocial impact of parental cancer on children and completion of cancer treatment [23–24].

Table 1.

Results of Quality Assessment Scores

| Quality Assessment Criteria | Quantitative (n=11) No. ( %) |

Qualitative (n=12) No. (%) |

Total (n=23) No. (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Explicit and soundness of literature review | 9 (81.8) | 12 (100) | 21 (91.3) |

| Clear aims and objectives | 10 (90.9) | 12 (100) | 22 (95.7) |

| Clear description of setting | 10 (90.9) | 9 (75.0) | 19 (82.6) |

| Clear description of sample | 9 (81.8) | 8 (66.7) | 17 (73.9) |

| Appropriate sampling procedure | 11 (100) | 8 (66.7) | 19 (82.6) |

| Clear description of data collection | 9 (81.8) | 11 (91.7) | 20 (86.9) |

| Clear description of setting | 10 (90.9) | 10 (83.3) | 20 (86.9) |

| Evidence of critical reflection (Qualitative Study) | - | 10 (83.3) | 10 (83.3) |

| Provision of recruitment data | 11 (100) | 9 (75.0) | 20 (86.9) |

| Provision of attrition data | 8 (72.7) | 2 (16.7) | 10 (43.5) |

| Provision of psychometric properties of the measurement instruments (Quantitative Study) | 3 (27.3) | - | 3 (27.3) |

| Appropriate statistical analysis (Quantitative Study) | 10 (90.9) | - | 10 (90.9) |

| Findings reported for each outcome | 8 (72.7) | 10 (83.3) | 18 (78.3) |

| Description of validity/reliability of results | 1 (9.1) | 5 (41.7) | 6 (26.1) |

| Sufficient original data (Qualitative Study) | - | 9 (75.0) | 9 (75.0) |

| Provision of strengths and limitations of the study | 8 (72.7) | 9 (75.0) | 17 (73.9) |

| Quality Scores | Mean (Range; SD) |

Mean (Range; SD) |

Mean (Range; SD) |

| 10.73 (8–13;1.5) |

10.33 (5–13; 3.1) |

10.52 (5–13; 2.5) |

|

Data Extraction and Data Analysis

Detailed critical appraisal of each included quantitative study was performed to extract the following data: study aims, design, study origin, participants, definition of lymphedema, measurement instruments for psychological factors and social factors [20–24]. Data were analyzed and synthesized to generate key results, strengths and weaknesses of the studies. The heterogeneity of the included quantitative studies and the use of a variety of measures limited the ability for a formal meta-analysis.

Qualitative studies were included to strengthen the systematic review [20–25]. Data extraction and analysis of the qualitative studies was guided by the established meta-synthesis methods [23–24, 26–27]. Meta-synthesis involves systematically identifying key concepts arising from each study, using the original quotations from participants and the themes described by the researchers. Common and different themes within and across the included studies were analyzed and synthesized to create a coherent literature summary [26]. The synthesis was started by listing all the themes the authors described in the most recent article in the review, then comparing the themes extracted from the most recent article with the themes identified by chromatically subsequent studies, listing the number of other studies that reported the same themes, and adding additional themes as they arose in the articles, until all themes were included on the list [24,27]. Data were analyzed and synthesized to identify the common themes, as well as to evaluate the strengths and weaknesses of each included qualitative study.

Results

Quality of the Included Studies

The overall quality of the 23 studies was adequate (Mean=10.52; SD=2.5; Range=5–13), as assessed by the adapted quality assessment tool [20–24]. No significant difference was found in the overall quality between the included quantitative studies (Mean=10.73; SD=3.1; Range=8–13) and qualitative studies (Mean=10.33; SD=3.1; Range 5–13). Detailed information regarding the mean quality scores for the quantitative and qualitative studies are reported in Table 1.

Quantitative Studies

There were a total of 5,090 participants in the 11 quantitative studies. The sample size in each study ranged from 128 to 1,449 participants. Lymphedema definitions and measurements varied greatly from study to study. Among the 11 quantitative studies, six studies used self-report of swelling [5, 15, 28–30], four studies used inter-limb differences in limb circumferences and volume by tape measures [3, 31–33], and one study used bioimpedance measurements [16].

None of the included 11 quantitative studies provided conceptual or operational definitions for psychosocial impact. No study was specifically designed to evaluate the psychosocial impact of lymphedema. Six studies provided data pertaining to the psychological, emotional, or social dimensions of HR-QOL [3,5, 7,16, 29,33]. Some studies focused on psychological factors/concerns (such as depression and anxiety [20, 26], mood disturbance [22], mental health [20]) and social factors/concerns (such as body image [29, 33], sexuality, social relationships [33], impact on leisure and recreational activities [32]. Six studies reported data regarding psychosocial impact of lymphedema using a validated HR-QOL instrument [3,5, 7,16, 29,33]. It should be noted that participants in 10 of the 11 quantitative studies were breast cancer survivors with one exception which included individuals with primary lymphedema [34].

Qualitative Studies

A total of 236 participants were in the 12 quantitative studies. The sample size in each study ranged from 5 to 42 participants. Among the 12 qualitative studies, 8 studies employed descriptive or hermeneutic phenomenological methodology [2,17,35–38]; one study used Pennebaker’s expressive writing paradigm [39]; one used a qualitative survey [18]; and 2 studies did not specify which qualitative methods were utilized [40–41]. The participants in 9 studies were female breast cancer survivors, while one study investigated male and female cancer survivors with lower extremity lymphedema. Two studies included both males and females, with both cancer and non-cancer related lymphedema [35].

Psychosocial Impact

Since the review was guided by the conceptual definition of the psychosocial impact of lymphedema as the combination of the psychological and social factors/concerns that directly affect an individual with lymphedema, the results of this systematic review are presented in terms of psychological and social domains directly and negatively affected by lymphedema or its treatment and management as well as factors associated with psychological and social impact of lymphedema.

Psychological Impact

Conflicting findings pertaining to the psychological domain were reported in this review. In Denmark, Vassard et al.[15] used the POMS-SF to assess 633 breast cancer survivors with lymphedema to specifically investigate emotional and psychological distress in the context of a rehabilitation program. The study found that there was no statistically significant difference in mood disturbance between women with lymphedema and without lymphedema (X=20; range: 16–24 vs. X=13; range: 11–15: p=0.32). Women with lymphedema had a 14% higher risk for scoring one level higher on POMS-SF, which was apparent at the 6- and 12-month follow-up. Similarly, using the FACT-B, in a matched pair case-control study in Hong Kong, Mak and colleagues [3] found no statistical significance, but a trend toward lower emotional well-being scores was noticed in Chinese breast cancer survivors with lymphedema (n=101), in comparison to those without lymphedema (17.3±5 vs. 18.1±4.9, respectively, p=0.2895). The researchers did not provide any data or discussion on the potential influence of Chinese culture on Chinese women’s emotional well-being.

In the US, Oliveri and colleagues [29] investigated the characteristics of arm and hand swelling in relation to perceived mental health functioning among breast cancer survivors (N=245) 9 to16 years post-diagnosis who had previously participated in a clinical trial coordinated by the Cancer and Leukemia Group B (CALGB 8541). Using the SF-36, they found there was no statistically significant difference in general mental health scores between women with lymphedema (X=76.11; range 28–100; SD=16.60) and without lymphedema (X=77.04; range: 20–100; SD=16.63). Using the Epidemiologic Studies-Depression, Breast Cancer Anxiety and Screening Behavior scale, the researchers also found no statistically significant difference in depression, breast cancer anxiety, body satisfaction, or general mental health between women with lymphedema and without lymphedema. In contrast to the previous findings, in the US, Paskett and colleagues [5] investigated the impact of lymphedema on HR-QOL in 622 breast cancer survivors using SF-12. These investigators reported that women with lymphedema had statistically significant poorer mental well-being scores than women without lymphedema (43.1 vs. 44.8, p<0.01).

In another study that included Japanese breast cancer survivors with and without lymphedema, investigators [30] found that women with lymphedema who reported pain had worse psychological well-being than those who reported no pain (20.19 vs. 21.68, p<0.05). In addition, women with lymphedema who reported more severe physical discomfort had worse psychological well-being than those who did not have severe physical discomfort (20.34 vs. 21.80, p<0.05), although no statistically significant association was found between pain, physiological discomfort, and psychological well-being. Chachaj [31] used the GHQ-30 to assess psychological distress in a study of 328 female breast cancer survivors in Poland and reported that breast cancer survivors with lymphedema had statistically significant worse psychological distress scores than survivors without lymphedema (10.61 vs. 8.01; F=7.42, p=0.007).

Consistent themes associated with negative psychological effects were identified in the 12 qualitative studies, including domains of changed self-identity, emotional disturbance, and psychological distress (e.g., depression, hopelessness, helplessness). Negative self-identity with associated reports of feeling “ugly,” “old,” “unattractive,” and “disgusted” were ignited by the sense of body image disturbance with the visible appearance of lymphedema ( the “swollen arm” or “puffy hand”) as a “a visible sign of disability” [2,18,41]. A sense of body image disturbance and negative self-identity associated with losing the “pre-lymphedema being” arose from the reality that lymphedema was a life-long chronic health issue and could not be cured or hidden [2,17–18,37–39]. All 12 of the studies reported negative emotions (frustration, anger, fear, self-blame, tiredness, sadness) and psychological distress (depression, hopelessness, helplessness). Several studies described that the sense of illness permanence and the chronicity of lymphedema elicited the negative emotions of fear, anger, sadness, and loneliness, frustration as well as psychological distress of depression, hopelessness, helplessness [18,37,39, 42–43]. Daily time-consuming self-care for lymphedema also caused frustration, depression, or anger [18,37,39, 42–43]. The type of lymphedema, that is, cancer-related or non-cancer-related, did not appear to influence the psychosocial issues faced by these individuals.

Social Impact

Statistically significant poorer social well-being in patients with lymphedema was an overall finding noted in this review of quantitative studies. Areas of particular concern included perceived sexuality and leisure impairments [32–34]. In a study of 537 breast cancer survivors in the US [28], breast cancer survivors with lymphedema had statistically significant poorer social well-being scores than those without lymphedema (5.5±0.25 vs. 6.1±0.21, respectively, p< 0.01) as measured by investigator-created measures of HR-QOL, after controlling for age, education, marital status, surgery type, and time since diagnosis. Mak and colleagues [3] found statistically significantly lower social well-being scores in Chinese women with lymphedema than those without lymphedema (20.5 ± 6 vs. 21.9 ± 4.9, p=0.0133).

In an intervention study assessing the impact of a strength-training program on perceptions of 234 breast cancer survivors [33], researchers used the BIRS to assess social barriers. The researchers found that women with lymphedema had lower social barriers, appearance and sexuality, and mental health scores than those without lymphedema, although there was no statistically significant association between the overall scores of BIRS and lymphedema. The strength-training program improved the scores of sexuality and appearance in the treatment group over 12 months (7.6±18.9 vs. −1.4±19.7).

Only one study evaluated the relationship of arm mobility, leisure pursuits, and recreational activities among women treated for breast cancer in Canada [32]. The researchers found that the presence of lymphedema had a statistically significant association with decreased recreational activities (r=0.096, p=0.011), but was not significant in multiple regression analyses using a self-report of leisure and recreational activities checklist.

Findings from these studies related to social well-being are supported by a large descriptive study of individuals with both cancer (n=840) and non-cancer-related lymphedema (n=609) [34]. This study reported that 75% of respondents noted their swelling interfered with daily living [34]. More than half (54%) experienced difficulties in their social life, 42% had work difficulties, and 21% had “close relationship” problems.

Consistent themes associated with negative social impact were identified in the 12 qualitative studies, including marginalization, perceived diminished sexuality, perceived social abandonment, social isolation, public insensitivity, financial burden, and unsupportive work environment.

Feeling of being marginalized was the major theme guiding the outcomes associated with social impact associated with lymphedema. Patients felt frustrated with healthcare providers’ or family’s relegation of lymphedema as unimportant or trivial, and when healthcare providers provided conflicting, minimal, or no lymphedema information [2, 38, 39, 42–43]. Patients also felt depressed, angry, or frustrated when their effort to engage in daily time-consuming self care was misunderstood and when there was a realization that there was little or no available funding from the health care system for lymphedema [2, 38, 39, 42–43].

One study reported mixed or conflicting experiences of lymphedema among female breast cancer survivors in the workplace [36]. In this study, the women described different negative feeling associated with lymphedema based on the nature of their work. Women who needed to perform heavy lifting or required frequent use of their affected limb described tremendous negative impact of lymphedema on their work; they felt “handicapped,” “disabled,” or “debilitated.” Women whose job required only occasional lifting reported lymphedema was just “a little limitation,” “inconvenience,” or a “bother to their work.” Lymphedema as a visible sign elicited varying social reactions at work, ranging from co-workers providing unrequested assistance with lifting to employers who were not helpful or supportive.

The negative impact of lymphedema on sexual relationships was reported by female breast cancer survivors [41]. Women in this study did not perceive themselves as “attractive” or “desirable” because of lymphedema, and they worried about sexual performance and their partners’ or spouses’ perception of them. Financial burden created worry and anger when insurance did not cover costly compression garments or other equipment for daily lymphedema management including prescribed therapy sessions [16,18].

Social isolation to avoid scrutiny from others was common, especially when individuals were asked repeatedly in public why their limbs were so “large” or “burned” [2,17,43]. Such public insensitivity also instilled negative emotions such as tiredness, feeling disabled, or depressed [2,17,43]. Perceived social abandonment was elicited by the feeling of being abandoned by the health care system, including lack of sufficient insurance and government support, lack of patient education, receiving minimal and inconsistent information from healthcare providers and insufficient response to their needs for and management of lymphedema [2,36–40].

Factors associated with the psychological impact

The quantitative studies provided information regarding some factors associated with the psychological problems experienced by individuals with lymphedema. For example, Oliveri and colleagues [29] investigated the characteristics of arm and hand swelling in relation to perceived mental health functioning among breast cancer survivors (N=245) and compared the chronic nature of lymphedema in terms of constant (Stage 2 and 3) and non-constant lymphedema (Stage 0 or Stage 1). They found that women with non-constant lymphedema reported statistically significant more breast cancer anxiety than women with constant lymphedema (p=0.006). Additionally, in the study by Chachaj and colleagues [31], breast and hand lymphedema had a statistically significant positive correlation with higher psychological distress (F=5.73, p=0.017; F=4.61, p=0.032, respectively). The researchers also found that pain in the affected breast had the strongest negative psychological impact (F=23.54, p< 0.001) and that pain was a stronger factor of psychosocial distress than swelling. In addition, upper arm lymphedema was a significant factor associated with higher psychological distress. These data suggest that lymphedema stage, location, and pain are associated with increased anxiety and psychological distress in patients with lymphedema.

Patient narratives revealed contributing factors that were perceived to be associated with psychological difficulties. From a psychological perspective, emotional frustration was the most important negative emotion expressed by breast cancer survivors [2,17, 36–41]. Frustration arose from the following contributing factors, including daily burden of time-consuming self care, difficulty in accepting lymphedema, loss of control of time, unexpected occurrence of lymphedema and symptoms; the fact that there is no cure for lymphedema; healthcare providers’ relegation of lymphedema as unimportant ; inability to find clothing or shoes to fit lymphedematous arm/hand or leg/foot; public insensitivity to inquiry pertaining to lymphedema; inaccurate and minimal information about lymphedema from healthcare providers; and lack of financial support from government and insurance companies [2,17,18,36–39]. Anger and emotional frustration occurred when individuals encountered difficulties conducting basic requirements for daily living, such as buying clothes, pants, or shoes to fit the lymphedematous arm/hand or legs/feet [2,18,40]. Social marginalization has also been identified as an important issue that is associated with psychological distress (e.g, depression, hopelessness, helplessness)[39].

Factors associated with the social impact

Contributing factors associated with social impact of lymphedema were also identified. For example, lack of social support related to living alone or without a partner led many participants to report that daily lymphedema care was perceived as a great burden [17,39]. Public inquiry and misunderstanding regarding lymphedema were other factors contributing to the feelings of being stigmatized, embarrassed, or resultant social isolation [18]. Lack of healthcare providers’ support contributed to social marginalization [2,36–40]. Insufficient insurance coverage for lymphedema management was the major contributor to financial burden, which instilled frustration, anger, and psychological distress (e.g., hopelessness and helplessness) [17–18]. Often, the contributing factors for psychological and social impact were intertwined.

Discussion

This review of studies published between 2004 and 2011 that examined the psychosocial impact of lymphedema identified 23 relevant articles from eight countries. The overall quality of the included 23 studies was adequate and no significant difference was found in the quality scores among the included quantitative studies and qualitative studies. Nevertheless, it is important to note a critical limitation of the reviewed literature, that is, lack of a conceptual or operational definition for the concept of psychosocial impact.

Only one quantitative study [34] and three qualitative studies included lower extremity lymphedema [35,42–43]; the other studies (19 of 23) primarily focused on breast cancer-related lymphedema. Thus, the findings of this review are biased toward identifying the psychosocial impact of breast cancer-related lymphedema and cannot necessarily be generalized to other group of patients with primary lymphedema or lymphedema related to other cancers in body regions, such as the head/neck, trunk, and lower extremity. About half of the studies (11 of 23; 47.8%) originated in the US and majority of the studies did not report the ethnicity data or the ethnic differences among individuals with lymphedema, which may also limit the broader generalization of these findings in different healthcare systems and/or cultural contexts.

The review revealed a paucity of quantitative studies that were specifically designed with the primary objective of quantitatively evaluating the psychosocial impact of lymphedema. Most of the studies focused on assessing the impact of cancer-related lymphedema on overall HR-QOL and therefore used generic HR-QOL instruments. Lower overall HR-QOL was reported among cancer survivors with lymphedema in all of the quantitative studies. Statistically significant poorer social well-being in patients with lymphedema was reported [3,28], including a negative impact on body image, appearance, sexuality, and social barriers [32–33]. However, no statistically significant difference was noted in the emotional domain [3,15], and conflicting findings were reported with respect to the psychological distress of depression and anxiety [5,29,33]. One of the contributing factors to such insignificant and conflicting findings might be lack of validated, disease-specific instruments to quantify the psychosocial impact of lymphedema for research. For example, FACT-B and SF-36 assess emotional well-being using items to assess generally feeling “happy,” “sad,” tired,” or “ depressed.” Such items might not be sensitive or sufficient enough to assess negative emotions (e.g., frustration, anger, fear, worry, guilt/self-blame) and psychological distress (e.g., hopelessness and helplessness) provoked by the chronic nature of lymphedema, lack of accurate information about lymphedema, marginalization, the financial burden (insufficient insurance coverage), daily self-care, or public insensitivity. Alternatively, inconsistent use of instruments across studies, inconsistent definitions of lymphedema, and heterogeneous samples may explain the mixed results.

Consistently, all 12 of the qualitative studies described negative psychological impact of lymphedema (including domains of negative self-identity, emotional disturbance, and psychological distress) and negative social impact (including domains of marginalization, financial burden, perceived diminished sexuality, social isolation, perceived social abandonment, public insensitivity, and non-supportive work environment). For example, many qualitative studies did report strong negative emotion of frustration [2,17–18,39], while quantitative studies reported no statistically significant difference regarding emotional domain among cancer survivors with and without lymphedema [3,15]. This may be because HR-QOL instruments do not assess frustration in general or frustration specifically related to lymphedema. In addition, all the HR-QOL instruments do not assess the concepts specifically related to lymphedema, such as “negative self-identity,” “financial burden,” “perceived diminished sexuality,” “marginalization,” “perceived social abandonment,” “social isolation,” “public insensitivity,” or “non-supportive work environment.”

Findings pertaining to the factors influencing the psychosocial impact of lymphedema suggest that, in addition to physical symptoms, lack of social, family, and professional support, time-consuming daily lymphedema care, lack of public sensitivity to the problem, insufficient health insurance, and financial burdens are all major contributing factors to the tremendous psychosocial effects experienced by these patients. It is important to note that the HR-QOL instruments are not specific and sufficient enough to assess such contributing factors identified through the synthesis of qualitative studies (Table 4), a deficit which has created limitations in research and challenges in clinical practice. It is clear that there is a need to develop additional valid, reliable lymphedema-specific measures capable of accurately evaluating psychosocial impact of lymphedema.

Table 4.

Recommended Domains of Psychological and Social Impact

| Operational Domains & Definitions | Dimensions | Contributing Factors | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Psychological Impact |

Negative Self-identity: individuals’ negative perception of self to be associated with lymphedema |

Body-image Disturbance |

*A person with swollen or huge arm *Feeling ugly, unattractive, disgusting *loss of pre-lymphedema being |

| Perceived disability |

*Handicapped *Disabled *A person with a visible sign of disability |

||

|

Emotion Disturbance: Negative emotions elicited or directly affected by lymphedema or its treatment and management |

Frustration | *Unexpected onset of lymphedema *The need to change previous life-style *The fact that no cure for lymphedema *Healthcare providers’ relegation of lymphedema to an unimportant trivial *Difficult in finding clothing or shoes to fit lymphedematous arm/hand or leg/foot *Public inquiry regarding lymphedema *Healthcare providers’ provision of inaccurate or minimal information of lymphedema *Lack of financial support from government and insurance company *Burden from daily involvement of managing lymphedema |

|

| Fear | * Fear of the lymphedema getting worse | ||

| Sadness | * Sad about having to wear non-fashionable or sexy clothes to fit the swollen arm | ||

| loneliness | *Feeling that being the only one with lymphedema and suffering from lymphedema *Feeling alone with managing this lifelong condition |

||

| Guilt/self-blame | * Feeling guilty about or blame self for something that patients did to cause lymphedema | ||

| Worry | *Worried that lymphedema is getting worse *Worried about no insurance coverage for some compression garments or prescribed therapy session *Worried about job security due to inability to accomplish assigned responsibility |

||

| Anger | *Healthcare providers’ provision of inaccurate or minimal information of lymphedema *Inability to find effective therapists |

||

| Tiredness | *The chronicity of the disease *Daily actions for lymphedema management |

||

|

Psychological Distress: depression, hopelessness and helplessness elicited by lymphedema and living with lymphedema |

Depression | *Feeling depressed that the condition has to be managed every day; *Depressed when physical function is impaired especially when one’s job responsibility is impacted |

|

| Hopelessness | * Feeling hopeless that there is no cure for lymphedema | ||

| Helplessness | *Feeling helpless when daily management of lymphedema could not improve symptoms *Feeling helpless due to loss of independency and having to rely on others’ to accomplish house work or job responsibility |

||

| Social Impact |

Marginalization: healthcare providers’ relegation of lymphedema as unimportant |

None | *Lack of support from healthcare providers *Lack of support from friends/family *Lack of funding from the health care systems |

| Financial Burden: limited financial support | None | *Limited insurance to cover costly compression garments, prescribed therapy sessions, and other equipments for managing lymphedema *Lack of financial support from government and insurance company |

|

|

Perceived Diminished Sexuality: perceived self as a non-sexy being & perceived inadequate intimate sexual relationship |

None | *Feeling no longer sexy or attractive with swollen limb *Feeling ugly with a huge limb *Feeling less attractive to spouse or partners *Feeling impaired relationship with spouse or partners *Loss of spontaneity of sex life *Encountering difficult in foreplay |

|

|

Social Isolation: Intentionally avoid social or public appearance or contact |

None | *Trying to not go out as much as possible *Trying to avoid any personal contact |

|

|

Unsupportive work environment: Perceived lack of support from employers or coworkers |

None | *Employers’ lack of knowledge of lymphedema *Employers or co-workers’ unwillingness to help with assigned job responsibilities |

|

|

Publics’ insensitivity: individuals were inquired in public about lymphedema |

None | * Constantly being asked about lymphedema in public |

Future Recommendations

Little consistency exists in the current literature in defining and measuring the psychological impact of lymphedema. None of the included 11 quantitative studies provided conceptual or operational definitions for psychosocial impact. The results of the review did support our conceptual definition of the psychosocial impact of lymphedema as a combination of psychological and social factors that directly affect an individual with lymphedema. In addition, the review did provide more detailed information for a better conceptualization and operationalization of the concept. To address this deficit and advance the science, it is important to provide evidence-based conceptualization of the concept, especially when considering conditions and needs specific to lymphedema and its treatment and management. The following conceptual definition is offered for consideration: psychosocial impact of lymphedema refers to the combination of the psychological and social effects elicited by or associated with the disease condition, or its treatment and management, which directly and negatively affect persons with lymphedema. The review also sheds light on the operationalization of the psychosocial impact of lymphedema by identifying specific domains, dimensions, and contributing factors of psychological and social impact through the synthesis of qualitative studies (Table 4). We recommend the operationalization of the psychological impact to include psychological domains of negative self-identity, emotional disturbance, psychological distress, and social impact to include domains of marginalization, financial burden, perceived diminished sexuality, social isolation, unsupportive work environment, public insensitivity, and perceived social abandonment.

Lack of specialized instruments to capture the unique psychosocial impact described by qualitative research may be one of the most important factors contributing to the conflicting and insufficient data in quantitative research. This deficit supports the need for developing a lymphedema-specific instrument to better characterize the psychosocial impact by considering factors contributing to psychological and social impact identified through the synthesis of qualitative studies (Table 4). In addition, more studies are needed to investigate lymphedema related to cancers beyond breast cancer and non-cancer-related lymphedema to address the limitations of the current literature.

Table 2.

Quantitative Studies

| Authors/ Reference #/ Study Origin |

Aim/Design | Sample/gender /Age |

Definition of Lymphedema |

Psychosocial Measures |

Psychological & Social Domains & Dimensions |

Key results | Study Strength | Study Weakness | QS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vasard et al., 2010 [15] Study Origin: Denm ark |

Aim: To investigate psychological distress, QOL, and health in women with LE. Design: Prospective study |

N=633 women (n=125 LE, n=508 non-LE). N=553 at first follow-up, N=494 at the second follow- up. Mean Age: NR Age Range: NR |

Self-report and then confirmed the status of LE diagnosis via telephone interview. |

Profile of Mood States questionnaire (POMS-SF) |

Psychosocial: Mood disturbance |

*No statistically significant difference of mood disturbance between women with LE and without LE. *Women with LE had a 14% higher risk for scoring one level higher on POMS-SF, as apparent at the 6- and 12-month follow- ups. |

*Used multivariate analysis to explore the relationship between LE and mood disturbance while controlling for other covariates. |

*Sample bias: Patients were attending a rehabilitation program. |

10 |

| Mak et al., 2009 [3] Study Origin: Hong Kong |

Aim: To compare arm symptom- associated distress and QOL in Chinese breast cancer survivor women with and without LE. Design: Matched pair case-control |

N=202 women (n=101 LE, n=101 non-LE) Age: LE=53.3 ± 9.6; Non- LE=50.3± 7.7 |

Documented LE in chart; arm circumference for LE (differences between 2 arms > 3cms, 3–5cms, >5cms). |

FACT-B +4a Chinese version. |

*Psychological: Emotional state, including sad, proud, losing hope, nervous, worry about dying or disease condition getting worse *Social: relationship with family, friends, spouse/partner; relationship with doctors |

*Statistically significant lower social wellbeing in women with LE in comparison with women without LE (20.5 ± 6 vs. 21.9 ± 4.9, p=0.0133). *statistical significance but poorer emotional wellbeing noticed in comparison with women without LE (17.3±5 vs. 18.1±4.9, respectively, p=0.2895). |

* Rigorous study design. * Used a control group of survivors without LE to compare the differences in psychosocial wellbeing while adjusting for the effect of stage of cancer, post- surgery length, and radiotherapy status. * Provided an insight of Chinese women’s social and emotional wellbeing with LE symptoms. |

*Retrospective design. *No data regarding the duration of LE. *No data and discussion regarding Chinese women’s cultural view that may help explain this insignificant finding of emotional wellbeing. * No data regarding patient’s relationship with doctors. |

13 |

| Chachaj et al., 2009 [31] Study Origin: Poland |

Aim: To investigate the factors associated breast cancer survivors with upper arm LE vs. non-LE patients. Design: Case- control |

N=328 female breast cancer survivors (n=117 LE; n=211 non-LE) Age: Non-LE: 59.95±10.56; LE 61.39±9.44 |

A difference of circumference >5 cm measured by patients. |

General Health Questionnaire (GHQ-30). |

Psychological: anxiety, and depression Social Factors: social dysfunction |

* Survivors with LE had statistically significant worse psychological distress than survivors without LE (10.61 vs. 8.01; F=7.42, p=0.007). *Survivors with LE in the affected breast and hand had a statistically significant positive correlation with higher psychological distress (F=5.73, p=0.017; F=4.61, p=0.032, respectively). * Pain in the affected breast had the strongest negative psychological impact (F=23.54, p< 0.001). *Pain is a stronger factor for psychosocial distress than swelling in survivors with LE. * Upper arm LE was associated with higher psychological distress. |

*Included a comparison group of survivors without LE. |

*Questionable validity of LE measured by pts (>5cm difference). |

12 |

| Speck et al., 2009 [33] Study Origin: US |

Aim: To investigate the impact of a strength training program on perceptions of breast cancer survivors. Design: RCT |

N=234 women (n=112 LE, n=122 non-LE) Age: LE 56±9, 58±9; Non-LE: age=55±7; 57±8, in treatment and control group respectively. |

Interlimb volume difference. |

Body image and relationship (BIRS); SF-36. |

*Psychological: mental health; *Social: Self- perception of appearance, sexuality, relationships and social functioning; |

* No statistically significant association between BIRS and LE. *Strength training program improved the scores of sexuality and appearance in treatment group over 12-months (7.6±18.9 vs. − 1.4±19.7) * Women with LE had worse social barriers, appearance and sexuality score, and mental health than patients without LE-using BIRS. |

*A large sample size with a RCT design. * Adjustment of age, marital status, race, education, BMI, and treatment to ensure the effectiveness of weight training. |

* Did not provide detail of psychosocial subscales of each scale for LE group. * Did not report or compare the difference of psychosocial impacts in pts with LE and without LE. |

12 |

| Oliveri et al., 2008 [29] Study Origin: US |

Aim: To investigate the association between characteristics of LE and mental health functioning among long-term breast cancer survivors. Design: Cross- sectional |

N=245 women (n=75 LE, n=170 non-LE) Age: 63±10 |

Self-reported LE |

* Epidemiologic studies- depression; breast cancer anxiety and screening behavior scale; *Self-concept scale; *SF-36. |

Psychosocial: Depression, anxiety Social: body satisfaction, general mental health. |

* 55% of women reported the first episode of LE within the first 2 years post-surgery. * 69% of women reported that LE interfered with their clothing fitting and perceived appearance. * No statistically significant difference of depression, breast cancer anxiety, body satisfaction, or general mental health between women with LE and without LE. * Non-constant LE women reported statistically significant more breast cancer anxiety than women with constant LE (p=0.006). *Women with severe swelling had trended toward worse depressive symptoms and poorer mental health (lower mental SF-36 scores) as well. |

*Investigate the psychosocial influence of LE in long-term breast cancer patients and no statistically significant psychosocial difference between long- term LE women and non-LE women which implies some mediating factors may occur in the long-term since surgery. * The study results demonstrated the LE impacts were not simply the presence of LE, but the temporal characteristics of swelling (e.g., transient and constant swelling). |

* Did not control for other factors which might impact QOL or psychosocial status (e.g., family stress, co- morbidities etc.) |

12 |

| Miedema et al., 2008 [32] Study Origin: Canada |

Aim: To examine the relationship between arm mobility, leisure pursuits, and recreational activities in women treated for breast cancer. Design: Cross- sectional |

N= 574 women Age: 54.29 ± 11.95 (n=17 LE; n=557 non-LE) |

Difference of percentage of arm volume in affected side vs. unaffected side by measuring every 10 cm from digital to proximal of both limbs **No LE: <10% volume difference **Minimal LE: 10% to 19% **Moderate LE: 20–45% **Severe LE: >40%. |

Self-report of leisure and recreational activities. |

Social: Leisure and recreational activities. |

* 49% of breast cancer survivors reported a decrease of recreational activities and 29% of them reported a decrease of leisure activities post-surgery. * Presence of LE was statistically significantly associated with decreased recreational activities (r=0.096, p=0.011), but not significant in multiple regression analysis. |

*Short post- surgery duration (6–12months) can minimize the memory bias. *Use of valid and reliable instrument. |

* Dichotomized LE may have under-estimated the impact of severity of LE limiting the possible significant impact of LE on leisure and recreational activities. |

11 |

| Heiney et al., 2007[28] Study Origin: US |

Aim: To compare the QOL of breast cancer survivors with LE and without LE. Design: Cross- sectional |

N=537 women (n=122 LE; n=415 non-LE) Age: 60.5±11.2 |

Self-report of LE. |

QOL-breast cancer version. |

Psychological, social, and spiritual wellbeing. |

* Patients with LE had statistically significant poorer social wellbeing than patients without LE (5.5±0.25 vs. 6.1±0.21, respectively, p< 0.01); *Education, age, level of education, type of surgeries negatively impact social wellbeing |

* ANOVA used to compare the variance between groups while controlling for other factors). |

* Rely on patient’s self- report LE. * Low participation rate (28%) may limit the generalizability. *No detailed description of items to assess psychological, social, & spiritual domain. |

9 |

| Tsuchiya, 2008 [15] Study Origin: Japan |

Aim: To assess the association between LE-related factors and QOL. Design: Cross- sectional |

N=138 women Age: 56.1±8.3 n=31 LE; n=107 non LE |

Self-report of LE and verified by palpation & inspection. |

WHO QOL- BREF Japanese version. |

Psychological and social wellbeing. |

* Women with LE who reported pain had worse psychological wellbeing than those who reported no (20.19 vs. 21.68, p<0.05). * Women with LE who reported more severe physical discomfort had worse psychological wellbeing than those who did not have severe physical discomfort (20.34 vs. 21.80, p<0.05). * No statistically significant association between pain, physiological discomfort and psychological wellbeing. |

* The study findings suggest the influence of physical wellbeing on psychological wellbeing among Japanese women with LE. |

* Lack of a comparison group. * It was not discussed why physiological discomfort and pain would influence psychological wellbeing but not social wellbeing. *No detailed description of items to assess psychological, social wellbeing. |

11 |

| Paskett et al., 2007 [5] Study Origin: US |

Aim: To investigate characteristics associated with LE and the impact of LE on QOL in young breast cancer survivors. Design: Longitudinal design |

N=622 women Age: 38.5±4.9 (n=336 LE by 36- month follow-up; n=286 Non LE) |

Self-report LE. |

SF 12-M and FACT-B. |

*Psychological: Emotional dimension, including sad, proud, losing hope, nervous, worry about dying or disease condition getting worse *Social: relationship with family, friends, spouse/partner; relationship with doctors |

* Women with LE had worse mental wellbeing scores than women without LE (43.1 vs. 44.8, p<0.01)—using SF-12. |

* High enrollment rate (93%) increased the generalizability of the target population. * Longitudinal design. * The study findings show that non-white race was a risk factor associated with LE. |

* No report on the reliability of self- reported LE. *No detailed report on the subscales on emotional and social dimensions of FACT-B+4 ULL |

11 |

| Ridner 2005[16] Study Origin: US |

Aim: To investigate the differences of QOL in breast cancer patients with and without LE. Design: Mix method (qualitative embedded in quantitative study) |

N=128 women (n=64 LE, n=64 non-LE) Age: LE 58±10.2:Non- LE 55±8.9 |

Bioimpedance measured the lymphedema index ratio between affected and unaffected limbs. |

Center for Epidemiologic studies of depression. |

*Psychological: Depression |

*No difference in depression between patients with LE and without LE using Center for Epidemiologic studies of depression. |

* Comparison with non-LE group helped understand the impacts of LE on patients with LE. *Age matched within three years. |

*Use of pilot symptom check- list. *No detailed report on the subscales on emotional and social dimensions of FACT-B+4 ULL |

9 |

| Lam, Wallace, Burbig, Franks, & Moffattt, 2006[34] Study Origin: United Kingdom |

Aim: To obtain an overview of lymphedema patient’s experiences. Design: Cross- sectional |

N= 1,449 mixed types of LE=, (1319 females; including primary and secondary LE) Age: 80% ≥50yrs. |

Self-reported LE. |

Self-report survey forms. |

Social wellbeing; close relationships; work |

*54% of all respondents reported problems with social life. Fewer of those with arm/hand LE only reported this problem (38%). *42% of all respondents reported problems with work. *21% of all respondents reported problems with close relationships. Fewer of those with arm/hand LE only reported this problem (12%). |

*Large sample size. *Included primary and cancer-related secondary LE. |

*Only reported basic descriptive statistics. *Did not use a valid and reliable instrument to collected psychosocial data. |

8 |

Abbreviations: LE: Lymphedema; QOL: quality of life; MLD: manual lymphatic drainage; NR: not reported in the study; QS: Quality scores

Table 3.

Qualitative Studies

| Authors/ Reference #/ Study Origin |

Aim/ Qualitative Method |

Sample/ Gender/age/ Duration of LE |

Key Findings | Emerging Themes | Study Strength | Study Weaknesses |

QS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ridner et al., 2011 [39] Study Origin: US |

Aim: To explore the perceptions and feelings toward LE among female breast cancer survivors. Qualitative Method: Pennebaker’s expressive writing paradigm |

*Sample: N=39 female breast cancer survivors with LE; *Age: 55.31± 10.14 *Duration of LE: Mean=5.75 ±4.06 |

* LE has negative psychosocial impact on female breast cancer survivors. * 90% felt unimportant or powerless. *74% felt a lack of support from healthcare providers which might be associated with disease management failure. * 54% of felt isolated from friends/family because they don’t understand LE. * 92% felt multiple losses, such as body-image disturbance, impaired functionality, and loss of control over time (a need more time for disease maintenance), and uncertainty (fear of the LE getting worse). * LE changed participant’s self-identity because it is a lifelong chronic health issue and can’t be cured or hidden. *77% wanted to be back to “normal.” * Those with psychosocial support from spouses, family members, friends, and coworkers, as well as spiritual supports described positive feelings toward LE and better coping with LE. |

* Multiple negative psychological and social experiences: 1) marginalization and minimization (lack of support from health care providers, as well as friends/family, and lack of funding from the health care systems); 2) multiplying losses (body image disturbance, impaired functionality, loss of control of time and uncertainty); 3) yearning to return to normal (want to be back to “pre- lymphedema”), and 4) uplifting resources (psychosocial support from significant others, as well as religious belief would reinforce the positive feelings toward LE). |

*Well-designed qualitative study using expressing writing method to uncover rich & in-depth understanding of the experience of living with breast cancer- related LE * Considerable larger sample size for a qualitative study |

* Inherent limitations from qualitative research design |

12 |

| Fu & Rosedale, 2009 [2] Study Origin: US |

Aim: To explore and describe breast cancer survivors’ LE-related symptom experiences. Qualitative Method: Descriptiv e Phenomenology |

*Sample: N=34 female breast cancer survivors with LE *Mean Age (range)=55 (35–86) *Duration of LE: Mean: 65 mos Range : 2 to 115 mos |

*LE brought emotional distress and frustration to breast cancer survivors with LE *Emotional frustration and distress also arose when women confronted situations in which LE symptoms unexpectedly led them to change their previous lifestyles (such as sad about “having to find different clothes to fit the swollen arm”), or they had to rely on others in daily routines at work and home. *Emotional frustration and distress is a result of daily experience of continuous physical LE symptom. *Severe emotional distress was experienced when LE symptoms interfered with women’s ability to accomplish tasks at work or when employers perceived the women’s “swollen arm,” or “puffy hand,” as “a visible sign of disability.” |

* Emotional distress evoked by LE symptoms may encompass multiple dimensions: 1) temporal (transient or consistent); 2) situational (unexpected situations evoked by symptoms); and; 3) attributive (emotional responses that change one’s perceived identity; such as losing their pre-lymphedema being or feeling handicapped. |

*Well-designed phenomenologi cal study *Considerable larger sample size for a qualitative study with different minority women *Identified that physical symptoms elicited negative emotions & changed breast cancer survivors’ self- identify |

*Inherent limitations from qualitative research design |

12 |

| Honnor, 2009 [38] Study Origin: United Kingdom |

Aim: To explore what LE-related information been given and what LE- related information is needed from a breast cancer survivor’s perspectives. Qualitative Method: Descriptive phenomenology methods |

Sample: N= 16 female breast cancer survivors with LE, *Mean Age= NR Age range= 50–79 breast cancer survivors *Duration of LE: Mean= NR; Range: <1yr to >24 yrs |

* 13/16 participants not informed about post- treatment LE. * Participants stated that they would like to have been informed about the physical and psychological consequences of LE. * Various experience of psychological effects of LE (minor, distressing, and worse than the breast cancer). |

* Negative psychological impacts of LE were varied: 1) perceived stigma, lack of self- efficacy (couldn’t do what they can do before the presence of LE, pre-lymphedema being); and, 2) impaired body image, and self- blame for the presence of LE. * Various information needs were mentioned (too much information would increase their anxiety, but some others felt positively about information that it helped them cope). * Various barriers of given information of LE: lack of healthcare provider’s time and their lack of knowledge of LE. |

*Adequate sample for qualitative study *Uncovered lack of patient education or information elicited emotional distress |

*Inherent limitations from qualitative research design |

10 |

| Maxeiner et al., 2009[18] Study Origin: US |

Aim: Explore the psychosocial issues resulting from primary and secondary LE by semi-structured interview and survey from an on- line support group. Qualitative Method: Qualitative Survey: Patient’s responses to 10 open-ended online survey questions. |

Sample: 42 surveys received Gender=NR *Age=NR 18 participants had primary LE while 24 had secondary cancer-related LE *Duration of LE: NR |

*Participants were frustrated and unsatisfied with the information provided by their physicians but satisfied with the information provided by their physical therapists, as well as dealing with Medicare and health insurance. *On-line support was the main support for primary LE, family and on-line support were for secondary LE. *Self-image: felt tired of and depressed about their LE; very self-conscious about their LE. * The chronicity of LE created fear, sadness, and sense of illness permanence. *Lamenting on the loss of pre-lymphedema life. *Frustration from public inquiry regarding LE. *Frustrated to find clothing or shoes to fit LE feet or arms. |

*Financial burden from managing LE. *Negative emotions (frustration) were elicited by trying to find clothing or shoes to fit LE arm/hand or leg/foot. *Inaccurate and minimal information from healthcare providers *Online support may help patient to cope with LE *Negative emotions (fear, sadness, sense of illness permanence) were elicited by the chronicity of LE—temporal dimension of LE. *Negative emotions were elicited by the visible appearance of LE: feeling ugly, old, unattractive, disgusting |

*Inclusion of 18 individuals with primary LE |

*No data regarding duration of LE *No specific qualitative method to guide the study *No discussion regarding the differences between individuals with primary & secondary LE |

5 |

| Fu, 2008 [36] Study Origin: US |

Aim: To explore the experience of work among female breast cancer survivors with LE. Qualitative Method: Descriptive phenomenological method |

*Sample: N=22 female breast cancer survivors with LE; *Mean Age (range)= 53 (42–65) *Duration of LE: Mean=37 mos (range: 2–108 mos) |

*They experienced different treatment from their co-workers/employers toward their LE. Co-workers may help them lift, but the employers might not be supportive to the other co-workers share/help the workload *Participants described different negative feeling levels of LE based on the nature of their work. *Study participants who needed to perform heavy lifting or frequently use their affected arm described their work more negatively, or as being handicapped, disabled, or debilitated. *Participants whose job only needed occasional lifting reported LE was less of a limitation, inconvenience, and bother to their work. *Different attitudes toward LE to their work were noted based on the nature of work. *Constant worriers were more evident among women whose job required heavy lifting or frequent use of their affected side. *Feeling fortunate and grateful to be alive was more common among women whose job required no heavy lifting or infrequent use of their affected side (less impact of LE on their work). |

* A mixed or conflicting experience of LE among female breast cancer survivors at work: 1) having a visible sign (disability vs. a need for help); 2) worrying constantly vs. feeling fortunate; and, 3) feeling handicapped vs. inconvenience due to the physical limitations of LE. |

*Well-designed phenomenologi cal study *Considerable larger sample size for a qualitative study *Identified that unsupportive work environment elicited negative emotions & changed breast cancer survivors’ self- identify |

*Inherent limitations from qualitative research design |

12 |

| Radina et al., 2008 [41] Study Origin: US |

Aim: To explore the impact of LE on sexual relationships among female breast cancer survivors with their intimate partners. Qualitative Method: NR |

*Sample: N= 11 female breast cancer survivors with LE *Mean Age (range)= 60.6 (51–78) *Duration of LE: Mean= 3.6 yrs (range: 0.75–13 yrs) |

* 4 of 11 women with LE appeared to have changes in their self-perceptions and body images. They did not perceive themselves as attractive or desirable because of LE or because of the garment, which might also impact their partner’s perception of their attractiveness. * Some women also noticed changes in their intimacy relationship with their partner. They might have concerns of their sexual performance (difficulties in foreplay because of LE) and were more aware of the support from their partner |

* LE had negative impacts on women’s experiences of sexuality: 1) not feeling sexy any more (change of body images and self- perceptions): and, 2) changes in intimate relationships |

*Adequate sample for qualitative study *Uncovered LE changed one’s perception of self *Uncovered that LE impacted patients’ sexuality & intimate relationship |

*No specific qualitative method to guide the study *Inherent limitations from qualitative research design |

11 |

| Towers, 2008 [17] Study Origin: Cana da |

Aim: To explore the psychosocial and financial stress among pts with LE from cancer survivors and their spouse’s perspectives. Qualitative Method: Descriptive phenomenological method |

*Sample: N=19 (n=11 LE- cancer survivors, n=8 spouses); 10 female and 1 man *Mean Patient Age =63.7 (range 50– 75); Spouse age=NR *Duration of LE: Mean=4 yrs (range 2–30 yrs) |

*All participants noted having a financial burden because the treatment and management devices were not covered adequately government or private insurance. *Due to the conflicting information sometimes provided by healthcare providers, patients felt alone with managing this lifelong condition, anger, and depression; however, they had a strong belief in relying on the information and support of healthcare providers. *Patients with LE felt the burden of managing LE in daily life, especially the affect on the time that a couple might spend together. *Patients stated the importance of a support system. They might have many sources of support (e.g., spouses, peer support groups, and LE organizations). *People who lived alone, or without partner support, might experience a greater burden with the physical LE management than others with spousal supports (e.g., putting on the garments or using management devices). |

* Psychosocial distress was not only from the direct impacts of LE, but also from the lack of financial supports: 1) frustration with lack of financial support from government and insurance company; 2) feeling alone with this lifelong health issue; and, 3) the burden of living with LE |

*Inclusion of 1 male patient *Inclusion of spouses *Designed to specifically understand psychosocial distress from cancer-related LE & financial problems *Well-designed phenomenologi cal study *Adequate sample for qualitative study |

*Inherent limitations from qualitative research design |

12 |

| Bulley, 2007 [40] Study Origin: Unite d Kingdom |

Aim: To explore LE-patients’ psychological needs as well as the benefits from health care. Qualitative Method: NR |

*Sample: N=5 female patients (n=2 primary LE, n=3 breast cancer- related LE) *Age: NR *Duration of LE: Mean= 34 mos for primary LE (range: 8–60 mos); Mean= 56 mos (range:6– 144 mos) |

*Psychosocial distress (e.g., helplessness, depression) was usually accompanied with physiological discomfort (e.g., pain, swelling, etc.) and impaired physical function. *Body image disturbance with LE which further impacted their daily life (e.g., difficulties looking into the mirror, difficulties in buying clothing and shoes, etc.). *Negative psychological impacts from coping with living with LE (anger and difficulties in accepting LE). *Positive psychological feelings could be facilitated by talking to the healthcare providers who know LE and understand the patient’s feelings. *Expectation of LE treatment/management had psychological impacts (patients who hoped to cure LE were less satisfied). |

* LE impacted physical mobility and function, as well as the disturbance and pain which decreased psychological wellbeing (e.g., anger, helplessness, depression, and body image disturbance). |

*Inclusion of 2 individuals with primary LE *Specifically designed to study psychological needs of patients with LE |

*No specific qualitative method to guide the study *Small sample size (n=5) even for qualitative study |

11 |

| Frid et al., 2006 [35] Study Origin: Sweden |

Aim: To explore cancer-related lower limb LE experiences, perceptions and how the late palliative stage patients manage their LE. Qualitative Method: Phenomenographic approach |

*Sample: N=13 cancer patients with lower limb LE (9 females, 4 males) *Mean Age (range): 63.3 (37–82) *Duration of LE: NR |

*Late palliative stage patients viewed lower limb lymphedema (LLL) as the least severe consequence of their cancer, but it was also a symbol of their cancer. Although it was just a minor problem compared to death and the illness the palliative patients face; some thought it impacted their daily life. *The presence of LE influenced patient’s thoughts about their future, their physical function, relationship with others, and their coping. *Increased knowledge may help them to cope with their LE on a cognitive level. |

* LLL influenced the patients’ thoughts about the future and their body image. Multidimensional psychosocial perceptions: contradicting feelings (hope vs. worry, positive vs. negative), negative feelings (fear, irritation, dependency, handicapped) due to the limited physical function, mixed emotions received from the interaction with others (consideration, sympathy, lack of understanding, avoidance). Psychological support but insufficient management for LE (lack of staff’s time, knowledge of LE) from healthcare providers, dependency, and avoidance (do not want to look at their legs and see friends). |

*Focus on experience of living with lower limb LE *Inclusion of both male & female patients |

*Sample bias: Patients were in the late palliative stage. *No data for duration of LE *Inherent limitations from qualitative research design |

11 |

| Greenslade & House, 2006 [37] Study Origin: Canada |

Aim: To explore the physical and psychosocial conditions among breast cancer survivors with LE. Qualitative Method: Hermeneutic phenomenological approach |

*Sample: N=13 female breast cancer survivors with LE *Mean Age: NR Age Range: 45–82 *Duration of LE: NR |

*LE impacts small but everything in survivors’ daily lives. Survivors had to change or adapt life-style to live with LE otherwise they had to face negative consequences of LE (e.g., pain, protection, discomfort). *Survivors yearned for lead a normal life without wearing compression sleeves and not being asked about their “fat and big” arms. *Feeling of being abandoned from health care system: survivors received minimal and inconsistent information from healthcare providers and insufficient response to their needs for and management of LE. *LE brought a lot of negative emotional feelings, such as frustration, anger, fear, self- blame, resigned, sad, and hopeless. |

* The essence of women’s perceptions of LE is existential aloneness around the other five psychosocial dimensions: normality (want to be normal and body image), abandonment (lack of education, apathy and cost of the healthcare system), searching (learning, and searching for supports), negative emotions (frustration, anger, sadness, helplessness, fear, self-blame), and constancy (the discomforts/accommodations are constant in daily life). |

*Adequate sample for qualitative study *Feeling being abandoned by healthcare system elicited negative emotions and psychological distress |

*No data regarding duration of LE *Inherent limitations from qualitative research design |

12 |

| Williams, Moffat, & Franks, 2004[42] Study Origin: United Kingdom |

Aim: To explore the lived experience of individuals with different types of LE. Qualitative Method: Phenomenological method |

*Sample: N=15 individuals with primary or secondary LE. 12 females and 3 males. *Mean Age (range): 57(35–89) *Duration of LE: Mean: NR Range:1–41 yrs |

*Lymphedema brought emotional uncertainty. *Feelings of tension with healthcare providers were present. *Diagnosis of LE brought fear, anxiety, and sorrow. |

*Uncertainty, “fishing in the dark” (too little information about LE), and tension with healthcare providers were predominant psychological themes. |

*Inclusion of primary & secondary LE *Inclusion male and female patients |

*Limited data regarding how the study proceeded in terms of recruitment, data collection, & data analysis |

9 |

| Bogan, Powell, and Dudgeon, 2007[43] Study Origin: US |

Aim: To gain insight into the perspective of individuals with non-cancer related LE. Qualitative Method: Naturalistic inquiry |

*Sample: N=7 individuals with non-cancer- related LE. 4 females and 3 males. *Mean Age (range): 55 (36–75) *Duration of LE: Mean: NR Range: 5–75 mos |

*Inability to obtain a correct diagnosis and treatment led to feelings of not living a full life. *Social isolation to avoid scrutiny of others was common. *Lack of answers about condition from healthcare providers was disturbing. *Effective treatment was associated with increased hope. |

*Nowhere to turn-to get help for dealing with the condition. *Turning point-once diagnosed and treated. *Making room in their lives to accommodate the intrusive nature of LE in their daily lives. |

*Focused on non-cancer- related LE *Inclusion of male and female patients |

*Small sample even for qualitative study *Limited data regarding how the study proceeded in terms of recruitment, data collection, & date analysis |

8 |

Note: LE: lymphedema; MLD: annual lymphatic drainage; Mo: month; QS: Quality Scores; NR: not reported in the study; QOL: quality of life; QS: Quality Scores; Yr: year.

Acknowledgements

On behalf of the American Lymphedema Framework Project, the authors thank Kandis Smith, Melanie Schneider Austin, and the reference librarians of the University of Missouri for their technical assistance.

Footnotes

- Mei R. Fu, PhD, RN, APRN-BC, has no financial interest or commercial association with information submitted in manuscript.

- Sheila H. Ridner, PhD, RN, FAAN, has no financial interest or commercial association with information submitted in manuscript.

- Sophia H. Hu, PhD, RN, has no financial interest or commercial association with information submitted in manuscript.

- Bob R. Stewart, EdD, has no financial interest or commercial association with information submitted in manuscript.

- Janice N. Cormier, MD, MPH, FACS, has no financial interest or commercial association with information submitted in manuscript.

- Jane M. Armer, PhD, RN, FAAN, has no financial interest or commercial association with information submitted in manuscript.

Contributor Information

Mei R. Fu, New York University College of Nursing, New York, NY.

Sheila H. Ridner, Vanderbilt University School of Nursing, Nashville, TN.

Sophia H. Hu, New York University College of Nursing, New York, NY.

Bob R. Stewart, University of Missouri Sinclair School of Nursing, Columbia, MO.