Abstract

Background

Myocardial infarction-induced remodeling includes chamber dilatation, contractile dysfunction, and fibrosis. Of these, fibrosis is the least understood. Following MI, activated cardiac fibroblasts (CFs) deposit extracellular matrix. Current therapies to prevent fibrosis are inadequate and new molecular targets are needed.

Methods and Results

Herein we report that GSK-3β is phosphorylated (inhibited) in fibrotic tissues from ischemic human and mouse heart. Using two fibroblast-specific GSK-3β knockout mouse models, we show that deletion of GSK-3β in CFs leads to fibrogenesis, left ventricular dysfunction and excessive scarring in the ischemic heart. Deletion of GSK-3β induces a pro-fibrotic myofibroblast phenotype in isolated CFs, in post-MI hearts, and in MEFs deleted for GSK-3β. Mechanistically, GSK-3β inhibits pro-fibrotic TGF-β1-SMAD-3 signaling via interactions with SMAD-3. Moreover, deletion of GSK-3β resulted in the suppression of SMAD-3 transcriptional activity. This pathway is central to the pathology since a small molecule inhibitor of SMAD-3 largely prevented fibrosis and limited LV remodeling.

Conclusion

These studies support targeting GSK-3β in myocardial fibrotic disorders and establish critical roles of CFs in remodeling and ventricular dysfunction.

Keywords: Cardiac fibroblast, GSK-3β, Myocardial infarction, Ventricular remodeling, SMAD-3, Fibrosis, Myofibroblast, TGF-β1 signaling

Introduction

Post-MI remodeling is a major cause of heart failure worldwide but despite more aggressive approaches to prevent remodeling, these strategies often fail. MI and most other cardiac diseases are associated with myocardial fibrosis, which is characterized by excess deposition of extracellular matrix (ECM) and accumulation of cardiac fibroblasts. Fibroblasts are the predominant cell type in the adult heart, are the principal producers of ECM, and contribute significantly to myocardial fibrosis. Virtually every form of heart disease is associated with expansion and activation of the CF compartment.1 The plasma levels of collagen markers, which correlate with ongoing cardiac fibrosis, are emerging as predictive markers for heart failure in humans.2 However, fibroblasts are still considered to play a secondary role in adverse cardiac remodeling and heart failure. Furthermore, most of the existing literature on cardiac fibroblast biology has been generated either from in vitro culture models or from a mouse model in which genetic manipulation has been targeted to cardiomyocytes only.

Cardiac fibroblasts are critically involved in both reparative and detrimental fibrotic responses post MI. In the healthy heart, resident fibroblasts are quiescent and produce limited amounts of ECM proteins.3 In response to the loss of a large number of cardiomyocytes in the ischemic heart due to necrotic cell death, cardiac fibroblasts, together with inflammatory cells, infiltrate to the ischemic area to initiate healing and scar formation, thereby maintaining the structural integrity of the myocardium.4 In addition, during acute tissue injury, mesenchymal and inflammatory cells secrete TGF-β1 to induce fibroblast to myofibroblast transformation. Myofibroblasts are phenotypically modulated cells characterized by the presence of a microfilamentous contractile apparatus enriched with α-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA). In the healing wound, activated myofibroblasts are the main source of ECM and play a critical role in both wound healing and tissue remodeling. Myofibroblasts are not present in the healthy myocardium.5 Although required for the reparative response and scar formation, persistent myofibroblast activity can lead to excessive scarring, loss of tissue compliance, and an extensive fibrotic response that is the basis for fibrotic disorders in numerous organs.4, 6, 7

TGF-β1 signals through at least two independent routes: 1) primarily through the SMAD-dependent canonical pathway and, 2) the SMAD-independent or non-canonical pathway. In the canonical pathway, activation of TGFβ type 2 receptor (TGFBR2) activates TGF-β type I receptor (TBRI; also known as TGFBRI1 or ALK5) and then the TBRI phosphorylates the transcription factors SMAD-2 and SMAD-3 (Receptor SMADs; R-SMAD). Upon phosphorylation, R-SMADs, together with the common mediator, SMAD-4 (CO-SMAD) translocate to the nucleus to regulate transcriptional responses. SMAD-6 and SMAD-7 are inhibitory SMADS (I-SMAD).7–9 TGF-β1 can also signal through non-canonical SMAD-independent pathways that include MAPKs, TNF receptor-associated factor 4 (TRAF4), TRAF6, TGFβ-activated kinase 1 (TAK1), RHO, PI3K, AKT, NF-κB and TRPC6.7

The roles of GSK-3β in cardiac myocyte biology and disease have been extensively studied.10–13 However, the role of GSK-3β in cardiac fibroblast activation and fibrotic remodeling post-MI is not known. In the present study we achieve CF-specific deletion of GSK-3β by employing Cre recombinase driven by Postn (periostin) promoter in GSK-3βfl/fl mice (Per-KO). In addition to Per-KO mice, we also employed tamoxifen-inducible Col1a2-cre mice (Col-KO) to obtain conditional fibroblast-specific GSK-3β KO mice. We report that deletion of GSK-3β leads to hyper- activation of pro-fibrotic TGF-β1-SMAD-3 signaling which results in excessive fibrosis and adverse ventricular remodeling, post-MI. Furthermore, using SIS3, a small molecule SMAD-3 inhibitor, we implicate unrestrained SMAD-3 activity as the key factor driving the detrimental phenotype in GSK-3β KO hearts. To our knowledge these studies are the first to demonstrate, what we believe to be a surprising effect of cardiac fibroblast-specific gene targeting on global cardiac function and adverse remodeling post-MI.

Materials and Methods

Please see online supplement for detailed methods.

Fibroblast-specific deletion of GSK-3β

All studies involving the use of animals were approved by the IACUC of the Temple University School of Medicine. Generation and characterization of fibroblast-specific GSK-3β KO mouse models is described in the Results section. At 12 weeks of age, Col-KO mice were placed on a tamoxifen chow diet (400mg/kg) for 28 days followed by regular chow for an additional 15 days (to allow the clearance of tamoxifen from the mice). Mice GSK-3βfl/fl/Cre/Tam were conditional knockout (Col-KO), whereas littermates GSK-3βfl/fl/Tam represented controls (WT).

Statistics

Differences between data groups were evaluated for significance using nonparametric Mann-Whitney test or one-way analysis of variance, as appropriate and Bonferroni post-test (GraphPad Prism Software Inc., San Diego, CA). Repeated measures analysis of variance was used to evaluate the statistical significance of data acquired from same animals over multiple time points. Survival analysis was performed by the Kaplan-Meier method, and between-group differences in survival were tested by the Log-rank (Mantel-Cox) test. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM, unless noted otherwise. For all tests, a P value of < 0.05 or less was considered to denote statistical significance.

Results

Activation of GSK-3β in mice and human ischemic/fibrotic heart

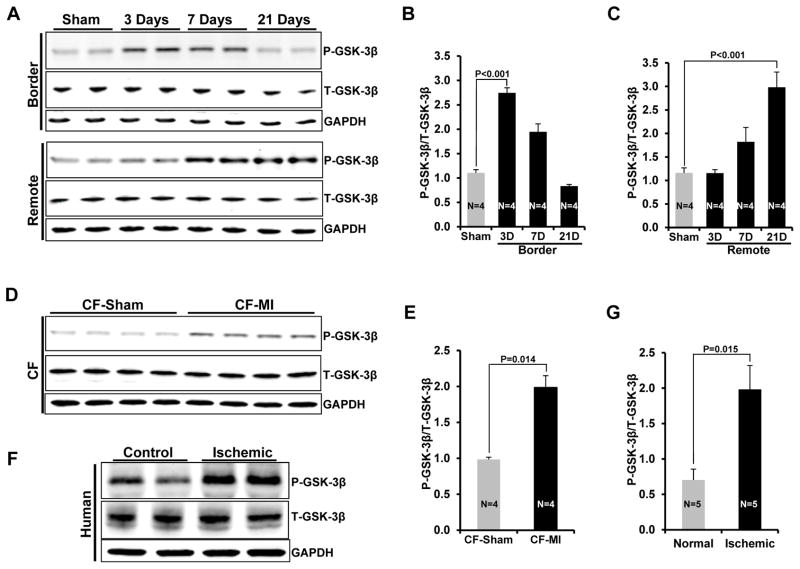

To test our hypothesis that GSK-3β critically regulates post-MI fibrosis and fibroblast activation, we first determined the effect of MI on GSK-3β activity (phosphorylation). Two month old WT mice were subjected to MI surgery and LV lysates from border and remote zones were analyzed for GSK-3β phosphorylation at various time points as indicated (Fig. 1A–C). In the border zone, MI induced maximal GSK-3β phosphorylation at day 3 post-MI, which slowly declined at later time points (day 7 and day 21) (Fig. 1B). In contrast, in the remote zone, GSK-3β phosphorylation was first observed at day 7 and continued to increase until the termination of the study (21days) (Fig. 1C). Thus, phosphorylation of GSK-3β is associated with pronounced fibrogenesis, initialy in the border zone, and later in the remote zone. To confirm the localization of the observed MI-induced GSK-3β phosphorylation to cardiac fibroblasts, cells were isolated from sham vs MI-operated hearts at 3 WKs post-MI and degree of phosphorylation of GSK-3β was determined. As hypothesized, GSK-3β phosphorylation (i.e. inhibition) was significantly increased in the fibroblasts isolated from ischemic hearts (Fig. 1D, E). MI-induced GSK-3β inhibition was further confirmed by analyzing the GSK-3β upstream effector, P-AKT (P-AKT473, P-AKT308), and the downstream targets (Cyclin D1, c-Myc), 3 wks post-MI (Suppl Fig. S1A–E). To determine the potential importance of this finding in the failing human heart, we examined GSK-3β phosphorylation in human heart tissues from end-stage ischemic cardiomyopathy patients. Indeed, phosphorylation of GSK-3β was significantly increased in the ischemic hearts compared to control hearts, consistent with the inhibition of GSK-3β in our ischemic mouse hearts (Fig 1F, G).

Figure 1. Activation of GSK-3β in ischemic heart and cardiac fibroblast-specific deletion of GSK-3β.

A, WT mice were subjected to MI surgery at 2 months of age. Three wks post-MI, western blotting was performed on the heart lysates from border and remote zone. B&C, Quantification of GSK-3β phosphorylation in border vs remote zone. D, CFs were isolated from sham and MI operated hearts at 3 weeks post-MI and western blot analysis was performed. E, Quantification of P-GSK-3β in CFs from sham and MI hearts. F, Representative Immunoblot showing significantly increased phosphorylation of GSK-3β in the ischemic human heart vs control heart. G, Quantification of GSK-3β phosphorylation in failing vs control human heart. H, WT and Per-KO mice were subjected to MI surgery at 2 months of age. Two wks post-MI, cardiac fibroblasts were isolated from the area of injury (left ventricle) and Western blotting was performed. Representative Immunoblot demonstrates 65% deletion of GSK-3β in KOs. I, Quantification of GSK-3β expression in GSK-3β KO fibroblasts versus WT fibroblasts.

Generation and characterization of fibroblast-specific GSK-3β KO mice

To evaluate the role of fibroblast GSK-3β in the regulation of MI-induced fibrotic remodeling and heart failure, we generated a mouse model in which GSK-3β was conditionally deleted in fibroblasts. We crossed tamoxifen-inducible Col1a2-cre mice with GSK-3βfl/fl mice to obtain conditional fibroblast-specific GSK-3β KO mice (Col-KO). Tamoxifen treatment led to an ~60% reduction of GSK-3β protein in the cardiac fibroblasts from KO mice compared to littermate controls. However, GSK-3β levels in the cardiomyocytes were unchanged (Suppl Fig. S2A–C). In addition to Col-KO, which targets all fibroblasts, we also generated a mouse model in which GSK-3β could be specifically deleted in cardiac fibroblasts. In this model, Cre recombinase is driven by a 3.9-kb mouse Postn promoter, (provided by Dr. Simon J. Conway, Indiana University, School of Medicine, USA).14 A recent study15 further confirmed that periostin expression in the heart is restricted to cardiac fibroblasts and is not expressed in cardiomyocytes, endothelial cells, or vascular smooth muscle cells in normal or injured hearts (ie subjected to MI or to pressure-overload). In the healthy adult heart, periostin expression is very low to absent, but increases dramatically, and specifically, in the fibroblast lineage after injury.14–17 In normal isolated fibroblasts, periostin is expressed in low amounts in cardiac fibroblasts, but expression dramatically increases after passaging during active myofibroblast transformation. Periostin expression goes down again when, presumably, transformation is nearing completion (Suppl Fig. S3A&B). To generate injury-inducible CF-specific KO mice, GSK-3βfl/fl mice were bred with Postn-Cre mice to generate CF-specific GSK3β-KO mice (Per-KO). Both Col-KO and Per-KO progeny were viable, fertile, reproduced at expected Mendelian ratios and showed no overt pathologic phenotypes. To determine the extent of CF-specific GSK-3β deletion that was induced following injury, WT and Per-KO mice were subjected to MI at 2 months of age. Cardiac fibroblasts were isolated from the injury area at 2 wks post-MI and levels of GSK-3β were determined by immunoblotting. GSK-3β protein level was reduced by ~65% in comparison to littermate controls (Fig. 1H, I). These complimentary models have key advantages: Per-KO is injury-inducible, allowing deletion of GSK-3β specifically in cardiac fibroblast post-injury whereas Col-KO mice allowed us to delete the gene at desired time-points (pre or post injury).

Deletion of GSK-3β in cardiac fibroblasts leads to cardiac dysfunction and dilatative remodeling post MI

To determine the effect of GSK-3β deletion on infarct size, WT and Col-KO mice were subjected to MI at 4 months of age. Infarct size was determined on day 2 post-MI using TTC-stained heart sections. We found that infarct size was comparable in WT and Col-KO hearts (Suppl Fig. S4A&B). To determine the role of GSK-3β in myocardial remodeling, WT and Col-KO mice were subjected to MI at 4 months of age. Pre-MI, WT and KO hearts had comparable chamber dimensions and ventricular function (Suppl Fig. S5A–D), but as early as 2 weeks post-MI, KO animals had a greater increase in end-diastolic and end-systolic dimensions in comparison to WT animals, reflecting accelerated dilatative remodeling in the KO (Suppl Fig. 6A&B). This was associated with marked LV dysfunction as reflected by reduced LVEF and LVFS (Suppl Fig. 6C&D). LV dilatation and dysfunction remained worse in the KO throughout the duration study.

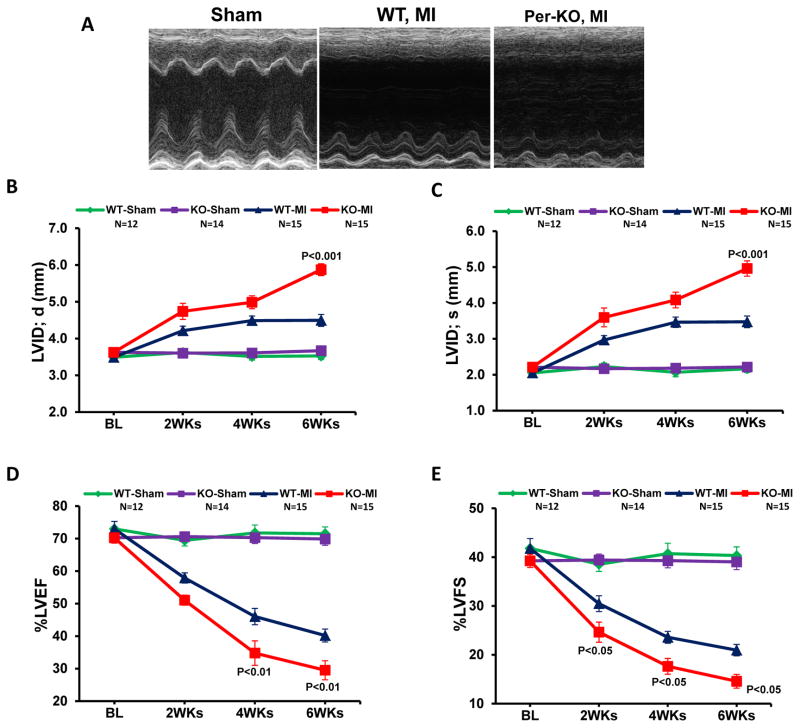

Since the Col-KO targets to all fibroblasts, we next examined this surprising phenotype in Per-KO mice which specifically target to cardiac fibroblasts. Indeed, Per-KO animals showed accelerated cardiac dysfunction and ventricular chamber dilation post-MI (Fig. 2A–E). At termination, both HW/TL and LW/TL were significantly increased in Per-KO mice, confirming increased post-MI hypertrophy and heart failure in GSK-3β deficient hearts (Fig. 2F&G). Consistently, a pattern of increased mortality was also obsereved in the KO mice post-MI; however, this did not reach statistical significance (Suppl Fig. 7).

Figure 2. Cardiac fibroblast-specific deletion of GSK-3β leads to cardiac dysfunction and dilatative remodeling post-MI.

Two-month-old WT and Per-KO mice underwent baseline transthoracic echocardiographic examination. Twenty-four hours later they were subjected to occlusion of the proximal left anterior descending coronary artery. Mice were then followed with serial echocardiography at the time points shown. A, Representative M-mode images from 6 weeks post-MI are shown. B, Left ventricular internal dimension at end-diastole (LVID;d). C, LVID at end-systole (LVID;s). D, left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF). E, LV fractional shortening (LVFS). F, Increased hypertrophy in the Per-KO mice subjected to coronary artery ligation as shown by HW/BW ratio. G, Increased heart failure in the Per-KO mice. The ratio of lung weight to body weight (LW/BW, a measure of heart failure) was significantly increased in the KO mice. MI, myocardial infarction; BL, baseline; WT, Wild type; KO, Knockout.

CF-specific deletion of GSK-3β increases post-MI scar circumference and fibrosis

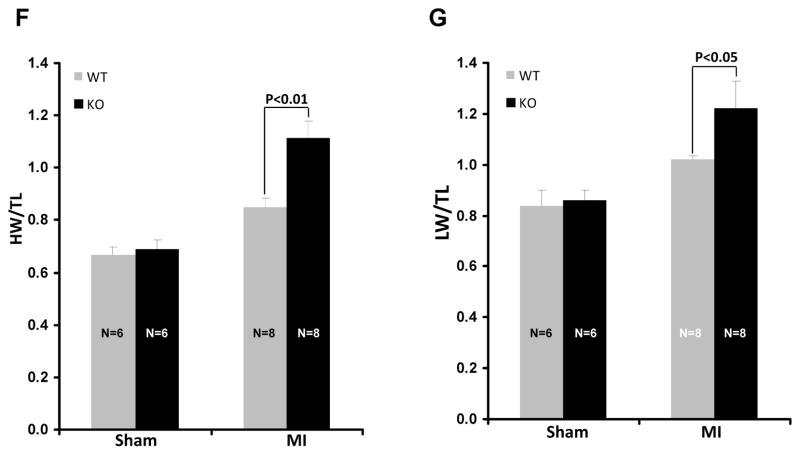

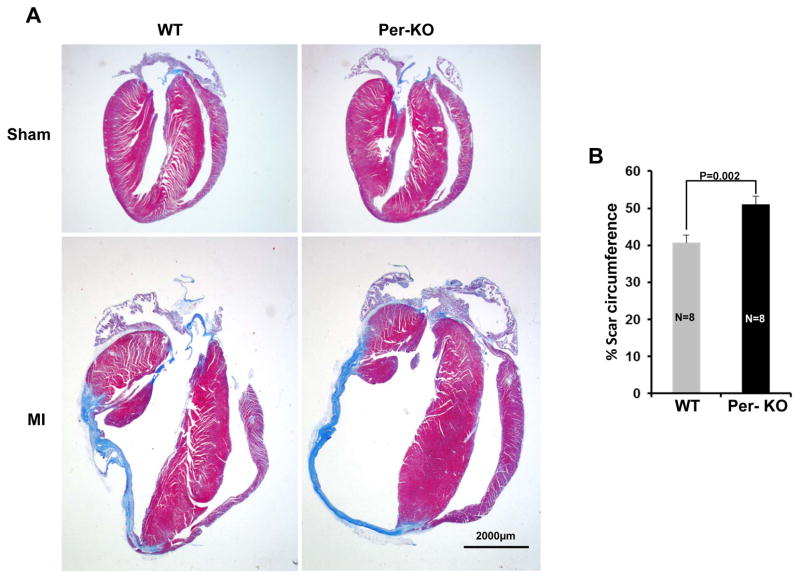

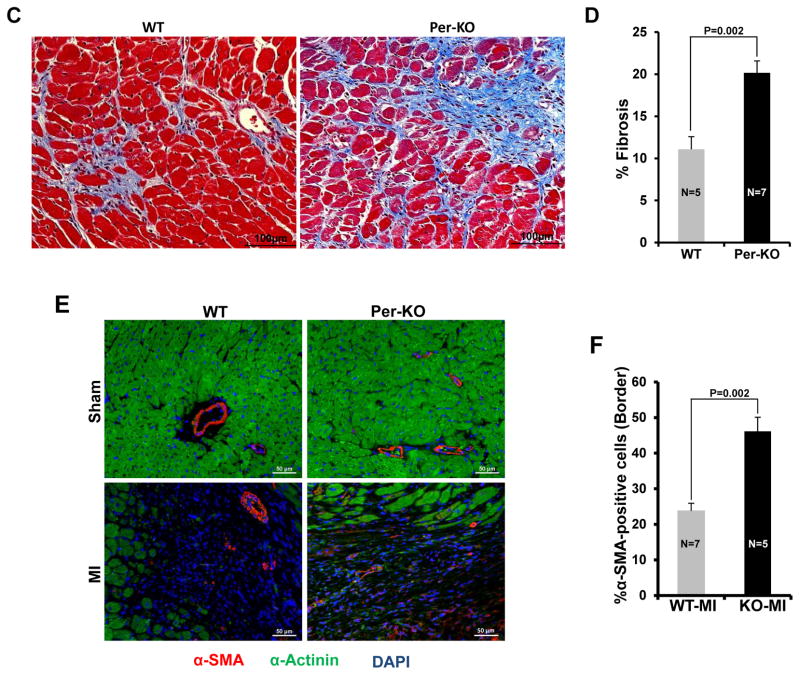

To determine the role of cardiac fibroblast GSK-3β in myocardial remodeling, WT and Per-KO mice were subjected to MI. At 6 wks post-MI, hearts were excised and Masson’s trichrome staining was performed. The percent circumference of the LV that was composed of scar tissue was determined as described.18,19 Scar tissue-% circumference was significantly increased in Per-KO hearts (Fig. 3A&B). Fibrosis was also significantly increased in the border zone of Pre-KO hearts (Fig. 3C&D). Consistently, scar tissue-% circumference was significantly increased in the Col-KO hearts at 6wks post-MI (Suppl Fig. S8A&B). Transformation of fibroblasts to myofibroblasts, characterized by expression of α-SMA and production of ECM components, is a key event in fibrotic remodeling. In agreement with previous reports we did not observed α-SMA positive cells in the sham operated heart.20, 21 However, cconsistent with the increased fibrosis and scar expansion, we also observed a significant increase in the number of α-SMA positive cells (myofibroblasts) in the infarct-region of KO hearts (Fig. 3E, F).

Figure 3. Cardiac fibroblast specific deletion of GSK-3β promotes post-MI scar expansion and fibrosis.

Two-month-old WT and Pre-KO mice were subjected to MI surgery for 6 weeks, as described in Materials and Methods. A, Representative images of heart sections stained with Masson trichrome at 6 week’s post-MI vs sham surgery. B, scar circumference was measured and expressed as a percentage of total area of LV myocardium. C, Representative images of LV border zone showing increased fibrosis in the KO mouse heart. D, Bar graph showing fold changes in fibrosis in the border zone of WT and KO hearts 6 weeks post-MI. E, At 6 weeks post-MI, immunofluorescence staining was performed to visualize α-SMA positive cells (red), Sarcomeric-alpha-actinin (α-SA), a myocyte-specific marker (green) and DAPI (blue) was used to label nuclei. Representative merge images are shown. F, Quantification of α-SMA positive cells is expressed as a percentage of total cells counted.

Deletion of GSK-3β induces myofibroblast transformation

Previous studies have shown that fibroblasts rapidly differentiate into myofibroblasts in in vitro culture conditions as indicated by increased α-SMA expression. We found that untreated CFs spontaneously undergo this differentiation under normal culture conditions even in early passage (Fig. 4A), emphasizing the importance of using low passage fibroblasts when conducting studies on effects of exogenous agents on myofibroblast transformation. For this reason, all of our studies were conducted in serum free conditions using passage 1 cells. We asked if spontaneous expression of α-SMA (i.e. myofibroblast differentiation) is associated with GSK-3β activity. To test this hypothesis, isolated cardiac fibroblasts were cultured up to 3 passages (all other experiments were done using passage one cardiac fibroblasts), and myofibroblast differentiation (α-SMA expression) and GSK-3β serine 9 phosphorylation (inhibition) were examined at every passage through Western blot analysis. Spontaneous expression of α-SMA was found to strongly correlate with inhibitory phosphorylation of GSK-3β (Fig. 4A&B). Next, we tested the hypothesis that inhibition of GSK-3β is required for spontaneous α-SMA expression in cultured cardiac fibroblasts. To test this hypothesis, CF were transfected with an adenovirus expressing a mutant form of GSK-3β (Serine S9A), which cannot be phosphorylated and, therefore, is constitutive active. Western blot analysis revealed that Ad-GSK-3β-S9A significantly decreases the α-SMA expression in the presence of TGF-β1 (Fig. 4C&D).

Figure 4. GSK-3β regulates fibroblast to myofibroblast transformation in cardiac fibroblasts.

A, Cardiac fibroblasts were isolated from 1–3 day old neonatal rat pups and were cultured up to three passages. Western blot analysis was performed to determine the expression of α-SMA and phosphorylation of GSK-3β. B, Line graph shows quantification of fold changes in α-SMA expression and GSK-3β phosphorylation. C, Neonatal cardiac fibroblasts were transfected with adenoviruses expressing constitutively active GSK-3β (Ad-GSK-3βS9) or GFP (Ad-GFP). After 24 h of transfection, viral medium was replaced with fresh serum free medium (SFM) and cells were treated with TGF-β1 (10ng/ml) for 48 h before harvesting. Western blot analysis was performed to determine the expression of α-SMA, endogenous and mutant GSK-3β, and HA-tag. D, Bar graphs show fold changes in α-SMA expression. E, MEF cells were cultured in complete DMEM medium (10%FBS and 1% antibiotics) to a confluency of ~75% and then were switched to fresh SFM medium for overnight starvation before harvesting. After starvation, cells were harvested and lysates were analyzed by immunoblotting with α-SMA and GSK-3α/β antibodies, as indicated. F, Bar graphs show fold changes in α-SMA expression in GSK-3β KO MEFs compared to WT cells. G, WT and GSK-3β KO MEFs were cultured on chamber slides and Immunofluorescence staining was performed. TGF, TGF-β1; GSKS9, GSK-3βS9

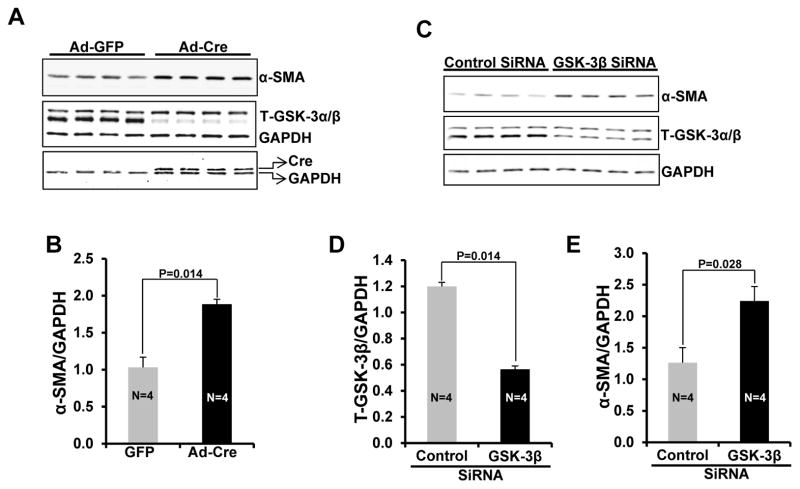

To further confirm the role of GSK-3β in myofibroblast transformation, loss of function studies were performed in WT and GSK-3β KO MEFs and isolated adult cardiac fibroblasts. Western blot analysis revealed that expression of α-SMA was several-fold up-regulated in GSK-3β KO MEFs at basal conditions in comparison to WT MEFs (Fig. 4E, F). Furthermore, GSK-3β KO MEFs showed a typical myofibroblast-like phenotype at basal conditions as revealed by immunofluorescence analysis (Fig. 4G). Next, adult cardiac fibroblasts were isolated from GSK-3β−fl/fl mouse hearts and GSK-3β was deleted by adenovirus-mediated Cre expression. In this model, expression of Cre leads to ~90% deletion of the target gene and, as anticipated, led to significantly enhanced expression of α-SMA (Fig. 5A&B). To rule out the possibility that Cre might play a role in myofibroblast transformation, we further confirmed these results by utilizing an siRNA approach. Indeed, siRNA mediated knockdown of GSK-3β was sufficient to significantly increase α-SMA expression (Fig. 5C, D, E). Taken together, these data suggest that GSK-3β negatively regulates cardiac fibroblast to myofibroblast transformation and its deletion/inhibition is sufficient to induce myofibroblast transformation.

Figure 5. GSK-3β regulates fibroblast to myofibroblast transformation in adult cardiac fibroblasts.

A, adult CFs were isolated from GSK-3βfl/fl mice and Cre was driven by adenoviral transfection to delete GSK-3β. After 24 h of transfection, viral medium was replaced with fresh SFM and cells were further maintained for 48 h before harvesting. Western blot analysis was performed to determine the expression of α-SMA, Cre, and T-GSK-3α/β. B, Bar graphs show fold changes in α-SMA expression. C, CFs were isolated from WT mice and were transfected with control and GSK-3β targeted siRNA. After 24 h of transfection, medium was replaced with fresh SFM and cells were further maintained for 48 h before harvesting. D&E, Bar graphs show fold changes in T-GSK-3β and α-SMA expression.

Mechanism of increased fibrosis and myofibroblast transformation in GSK-3β KO

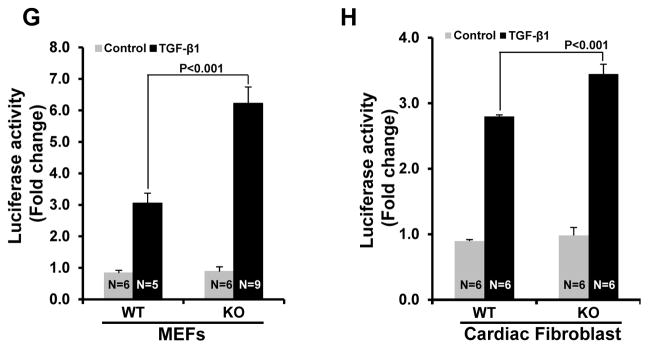

We next examined the possible mechanisms responsible for the increased myofibroblast formation and fibrotic remodeling in GSK-3β-KO mice. TGF-β1 is the most potent inducer of ECM production characterized to date and promotes fibroblast to myofibroblast differentiation. TGF-β1 is known to activate SMAD-2 and SMAD-3; however, the pro-fibrotic effects of TGF-β1 signaling have been largely attributed to SMAD-3 mediated signaling.6, 22 To determine the role of GSK-3β on TGF-β1 signaling, WT and GSK-3β KO MEFs were treated with TGF-β1 (10ng/ml) for 1h and phosphorylation of SMAD-3 at the C-terminus (Ser423/25) was determined. Indeed, upon TGF-β treatment, the C-terminal phosphorylation of SMAD-3 was significantly increased in GSK-3β null cells compared to wild-type cells (Fig. 6A, B). To determine the role of GSK-3β on TGF-β1 signaling in cardiac fibroblasts, neonatal cardiac fibroblasts were isolated from 1–3 day old rat pups. Cells were treated with TGF-β1 (10ng/ml, 1h) in the presence or absence of GSK-3 inhibitor SB216763 (10μM, 30 min pretreatment). As hypothesized, inhibition of GSK-3β led to a significant increase in the phosphorylation of SMAD-3 at Ser 423/25 (Fig. 6D, E).

Figure 6. Deletion/inhibition of GSK-3β in fibroblasts leads to hyper-activation of TGF-β1-SMAD-3 signaling.

A, WT and GSK-3β KO MEFs were serum-starved overnight before receiving TGFβ-1 for 1 h (10ng/ml). Western blot analysis was performed to analyze the phosphorylation of SMAD-3 at Ser204 and Ser423/425. B, Bar graphs show fold changes in phosphorylation of SMAD-3 at Ser423/425 in GSK-3βKO MEFs compared to WT cells in the presence or absence of TGF-β1. C, Bar graphs show fold changes in phosphorylation of SMAD-3 at Ser204. D, Neonatal cardiac fibroblasts were serum starved overnight before receiving GSK-3 inhibitor SB415286 (10μM) for 30 min and an additional 1 h of TGF-β1 stimulation. Western blot analysis was performed to analyze the phosphorylation of SMAD-3 at Ser204 and Ser423/425. E, Bar graphs show fold changes in phosphorylation of SMAD-3 at Ser423/425. F, Bar graphs show fold changes in phosphorylation of SMAD-3 at Ser204. G&H, Cells were transfected with SMAD-3 Cignal Lenti Reporter virus. Forty-eight h after transfection, cells were treated with 5ng/ml TGF-β1 for 24 h and the luciferase activity was quantified.

To date, most studies on TGF-β signaling pathways have focused on TGF-β receptors directly phosphorylating and activating SMAD transcription factors within the C-terminal domain.8, 9 However, there is increasing interest in alternate serine and threonine phosphorylation sites within the linker region of SMADs, which control a number of cellular responses including epithelial-mesenchymal transition and SMAD-3 transcriptional activity.23–25 In contrast to C-terminal domain phosphorylation (which leads to activation), linker region phosphorylation leads to inhibition of SMAD transcriptional activity.23, 26 We asked if GSK-3β might also regulate SMAD-3 activity by modulating SMAD-3 phosphorylation in its linker region in fibroblasts. WT and GSK-3β KO MEFs were treated with TGF-β1 for 1 h and phosphorylation of SMAD-3 at Ser204 was determined. Indeed, TGF-β1-induced phosphorylation of SMAD-3 at Ser204 was significantly decreased in GSK-3β KO cells (Fig. 6A, C). Similar results were observed in neonatal cardiac fibroblasts in the presence of GSK-3 inhibitor SB216763 (10uM, 30min pretreatment) (Fig. 6D, F). These results indicate that GSK-3β exerts dual control on TGF-β1-SMAD-3 signaling, specifically by regulating both the C-terminal domain as well as the linker region. To investigate the role of GSK-3β in the regulation of SMAD-3 transcriptional responses, SMAD-3 reporter assays were performed as described in the Methods section. Indeed, TGF-β1-induced transcriptional activity of SMAD-3 was significantly increased in the GSK-3β KO MEFs and GSK-3β deleted adult cardiac fibroblasts (Fig. 6G&H). These results indicate that GSK-3β is a critical regulator of canonical TGF-β1 signaling and its deletion, or inhibition, leads to aberrant hyper-activation of pro-fibrotic TGF-β1-SMAD-3 signaling.

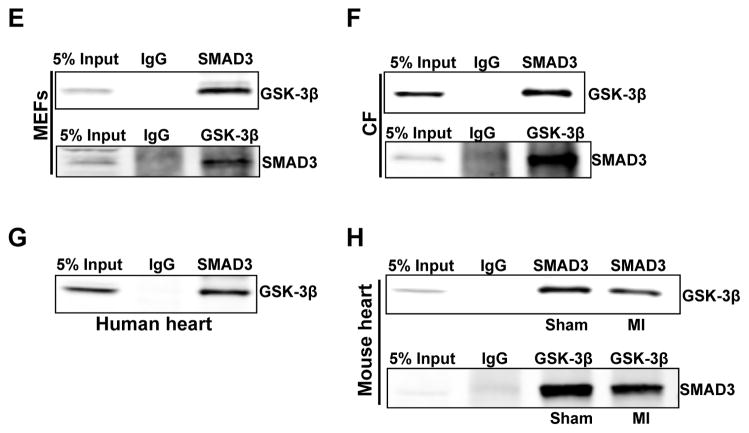

Nucleocytoplasmic trafficking of SMAD-3 is a rate-limiting step in TGF-β signaling and is important for determining the strength and duration of the signal and biological response.27–29 To further dissect the role of GSK-3β in restricting TGF-β-SMAD-3 activity, we examined the intracellular distribution of SMAD-3 in WT and GSK-3β KO MEFs and in cardiac fibroblasts. After sub-fractionating cells into cytoplasmic and nuclear fractions, we analyzed the content of GSK-3β and SMAD-3 in these two fractions by Western blotting. GSK-3β was primarily found in the nuclear fraction in both MEFs and cardiac fibroblasts (Fig. 7A–D). As expected, TGF-β treatment (10ng/ml, 1h) significantly increased nuclear content of total SMAD-3 in MEFs and cardiac fibroblasts. Of note, TGF-β-induced nuclear translocation of SMAD-3 was independent of GSK-3β in both MEFs and cardiac fibroblasts. These findings indicate that GSK-3β-mediated regulation of TGF-β-SMAD-3 signaling is independent of nuclear- cytoplasmic trafficking of SMAD-3.

Figure 7. GSK-3β directly interacts with SMAD-3 but does not affect its nuclear accumulation after TGF-β1 stimulation.

A, Nuclear and cytoplasmic fractionation was performed with WT and GSK-3β KO MEF cells treated with TGFβ1 (10ng/ml) for 1 h. The content of GSK-3β, SMAD-3, nuclear marker LaminA/C, and cytosolic marker GAPDH was determined. B, Bar graphs show fold changes in SMAD-3 and GSK-3β translocation to the nucleus after TGF-β1 stimulation. C, Neonatal cardiac fibroblasts were serum starved overnight before receiving GSK-3 inhibitor SB415286 (10μM) for 30 min and an additional 1 h of TGF-β1 stimulation. Nuclear and cytoplasmic fractionation was performed and content of GSK-3β, SMAD-3, nuclear marker LaminA/C, and cytosolic marker GAPDH was determined. D, Bar graphs show fold changes in SMAD-3 and GSK-3β translocation to nucleus after TGF-β1 stimulation. E, MEFs were lysed for endogenous co-immunoprecipitation assay using either IgG or the monoclonal antibodies as indicated, and followed by immunoblotting. F, G, physical interaction between SMAD-3 and GSK-3β was also examined in lysates from cardiac fibroblasts and human heart. H, Co-immunoprecipitation assay was performed with lysates from sham and MI operated hearts at 6 weeks post-MI, using either IgG or the monoclonal antibodies as indicated, and followed by immunoblotting.

To further dissect the mechanism by which GSK-3β regulates SMAD-3 signaling, we examined whether these proteins might physically interact. Endogenous SMAD-3 in MEFs and cardiac fibroblasts was found to co-immunoprecipitate with GSK-3β (Fig. 7E, F). As an alternative approach to probe for a possible interaction between SMAD-3 and GSK-3β, we tested whether immunoprecipitation of SMAD-3 also pulled down GSK-3β in MEFs and cardiac fibroblasts. Indeed, a co-immunoprecipitation experiment with SMAD-3 antibody further suggests the interaction of SMAD-3 with GSK-3β both in MEFs and CF (Fig. 7E, F). Furthermore, we demonstrated that GSK-3β and SMAD-3 also interact in the human heart as revealed by a CO-IP experiment with human heart lysates (Fig. 7G). To determine the effect of MI on GSK-3β and SMAD-3 interaction, CO-IP studies were performed with lysates from sham and MI operated hearts at 6 weeks post-MI. MI leads to a decrease in the interaction of SMAD-3 and GSK-3β (Fig. 7H). Taken together, these studies suggest that GSK-3β interacts with, and thereby maintains, the low level of activity of SMAD-3 in the normal healthy heart.

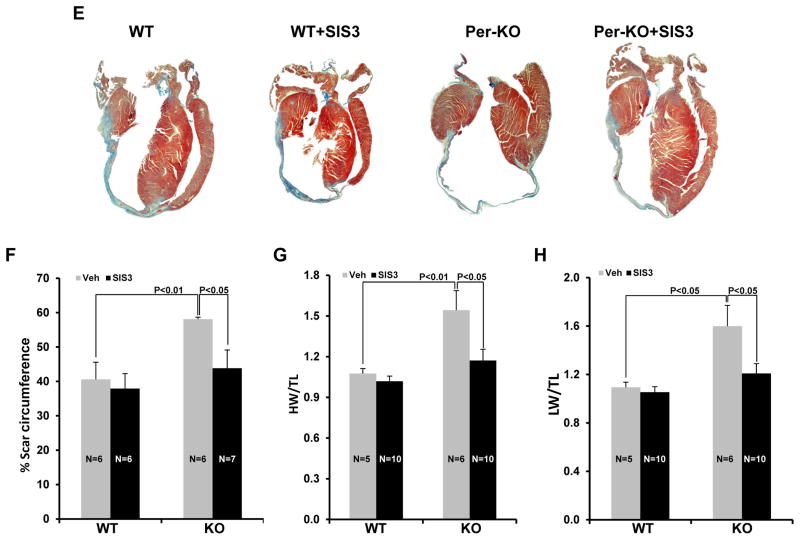

SMAD-3 inhibitor rescues the detrimental phenotype of GSK-3βKO post-MI

Finally, we wanted to determine the molecular mechanism of the observed detrimental phenotype in the GSK-3β KO mice, with our hypothesis being that hyper-activation of SMAD-3 in the KO hearts is the cause, rather than consequence, of excessive remodeling. Therefore, we asked if a small molecule inhibitor of SMAD-3 could rescue the observed detrimental phenotype in GSK-3β KO mice. SIS3 (1.25mg·kg−1·day−1) or vehicle was administered to WT and Per-KO mice by osmotic mini-pumps. Taking into consideration the injury-inducible model (i.e. deletion starts with injury) and the requirement of fibrosis in the early healing process and scar maturation, we implanted the pumps one week after MI surgery so as to focus on the post-MI remodeling phase. Mice were followed with serial transthoracic echocardiography. The efficacy of SIS3 treatment in the applied experimental condition was confirmed by western blot analysis of P-SMAD-3 at Ser423/25 in the LV lysates (Suppl Fig. S9A&B). To our surprise, SIS3 administration nearly abolished the detrimental phenotype of GSK-3β deletion as evidenced by restored ventricular function and chamber dimensions (Fig. 8A–D). SIS3 also significantly blunted scar expansion in Per-KO hearts compared to Per-KO treated with vehicle. Protective effects of SIS3 were also observed in HW/TL, HW/LW ratio and in limiting scar expansion (Fig. 8E–H). Of note, SIS3-mediated protection was seen much earlier in the KO hearts than in WT littermates (Suppl Fig. S10A&B). We believe that this was due to the extent of aberrant hyper-activation of SMAD-3 in the KOs vs WTs. Together, these findings provide strong evidence that hyper-activation of SMAD-3 is largely responsible for the detrimental phenotype following selective inhibition or deletion of GSK-3β in cardiac fibroblasts.

Figure 8. Pharmacological inhibition of SMAD-3 attenuated the cardiac dysfunction, dilative remodeling and scar expansion in Per-KO hearts post-MI.

WT and Per-KO mice underwent baseline transthoracic echocardiographic examination. Twenty-four hours later they were subjected to occlusion of the proximal left anterior descending coronary artery. Mice were then followed with serial echocardiography at the time points shown. Osmotic pumps were implanted 1 week post MI surgery. A, left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF). B, LV fractional shortening (LVFS). C, Left ventricular internal dimension at end-diastole (LVID;d). D, LVID at end-systole (LVID;s). E, Representative images of heart sections stained with Masson trichrome 5 weeks post-MI. F, scar circumference was measured and expressed as a percentage of total area of LV myocardium. G, SIS3 rescues increased hypertrophy in the KO mice subjected to coronary artery ligation as shown by HW/BW ratio. H, SIS 3 rescued the failing heart phenotype the KO mice. The ratio of lung weight to body weight (LW/BW, a measure of heart failure) was significantly attenuated by SIS3 treatment in the KO mice. SIS, SMAD-3 inhibitor SIS3

Discussion

It is generally accepted that fibroblasts are critically involved in both the reparative response and the pathogenesis of cardiac remodeling following MI.1, 30 Despite this, direct evidence for a role of cardiac fibroblasts in MI-induced remodeling is lacking, largely due to the lack of genetic tools for specifically manipulating the cardiac fibroblast in vivo. Herein, we used two different fibroblast-specific GSK-3β KO mice to demonstrate that GSK-3β negatively regulates fibrotic remodeling in the ischemic heart. Specifically, we found that GSK-3β modulates canonical TGF-β1 signaling through direct interactions with SMAD-3. Furthermore, we show that GSK-3β–mediated negative regulation of fibrosis is essential to limit the adverse ventricular remodeling in the ischemic heart. When GSK-3β is deleted in cardiac fibroblasts, SMAD-3 is hyper-activated, resulting in excessive fibrosis that leads to rapid adverse ventricular remodeling. Re-establishing SMAD-3 inhibition by the small molecule inhibitor SIS3 attenuates MI-induced ventricular dilatation and contractile dysfunction.

The literature examining the role of fibrotic remodeling in vivo is confusing to say the least. Only two studies have attempted to address this issue with any success.14, 31 The first, by Takeda et al14, employed deletion of Kruppel-like factor 5 (KLF5) using the periostin Cre model. They used thoracic aortic constriction (TAC) at two levels of severity. With low intensity TAC, they found deletion was protective with less fibrosis and less hypertrophy. Based on studies in conditioned media, and using micro-arrays, they concluded that the mechanism of less hypertrophy was not via an effect on fibroblasts but was due to less secretion of IGF-1. Strikingly, with high intensity TAC, the phenotype was the opposite-increased mortality and LV dysfunction. Mechanisms of these opposing effects remain unclear. The second attempt to discern mechanisms of fibrotic remodeling employed a Col-Cre strategy to delete β-catenin.31 The conclusion drawn was that deletion of β-catenin led to defective fibrosis and cardiac dysfunction. However there were virtually no mechanistic data to explain the phenotype other than possibly fibroblast proliferation. In striking contrast, we deleted GSK-3β, an anti-fibrotic factor, and this led to markedly increased fibrosis, and increased scar expansion.

To our knowledge this is the first report describing a direct role of cardiac fibroblasts in MI-induced fibrotic remodeling, employing a cardiac fibroblast-specific mouse model. We have previously reported that conditional deletion of GSK-3β specifically in cardiomyocytes leads to cardiomyocyte proliferation, but does not have any effect on fibrosis following pressure overload or MI.10 Taken together, these results suggest that the functional consequence of loss of GSK-3β is cell type-dependent in the heart and that deletion/inhibition of GSK-3β in fibroblasts is detrimental. It is generally accepted that persistent myofibroblast activation, and the resultant increase in fibrous tissue they produce, cause progressive adverse myocardial remodeling, a pathological hallmark of the failing heart, irrespective of its etiologic origin. However, the responsible molecular mechanism/s are complex and not well understood.4, 32 Consistent with increased fibrosis, fibroblast to myofibroblast transformation was significantly increased in KO hearts. Moreover, by using a combination of genetic and pharmacological tools we demonstrate that inhibition of GSK-3β is essential to induce fibroblast to myofibroblast transformation. Importantly, inhibiting myofibroblast transformation following cardiac injury has been shown to decrease fibrosis.33 Matsuda et al.13 employed a constitutively active global knock-in mouse model and showed that TAC-induced fibrosis was abolished in the heart of GSK-3β knock-in mice, suggesting that inhibition of GSK-3β is required for TAC-induced fibrosis. Our findings are consistent with this observation and show the robust increase in the fibrotic response in GSK-3β KO hearts post-MI. These data suggest that GSK-3β is an essential regulator of myocardial fibrosis in the injured heart and strategies to maintain GSK-3β in an active state, especially in the remodeling phase after MI, may provide a therapeutic option to inhibit fibrosis and thus limit maladaptive remodeling.

In order to investigate the mechanisms by which cardiac fibroblast GSK-3β regulates fibrotic remodeling, we identified SMAD-3 as a key target of GSK-3β in cardiac fibroblasts. Inhibition or deletion of GSK-3β in cardiac fibroblasts leads to hyper-activation of SMAD-3 as evidenced by increased phosphorylation of SMAD-3 within the C-terminal domain (S423/425) and decreased phosphorylation in the linker region (S204). Both of these post-translational modifications are known to increase transcriptional activity of SMAD-3. To our knowledge, this is the first report showing dual control of SMAD-3 activation by GSK-3β. This occurs by modulating both the carboxyl terminal domain (S423/425) and linker (S204) phosphorylation sites. Our data also show that GSK-3β and SMAD-3 directly interact. However, it is unclear precisely how deletion/inhibition of GSK-3β might lead to increased phosphorylation of SMAD-3 at S423/425, and determining the mechanism is beyond the scope of this work.

Given the critical role played by SMAD-3 in tissue fibrosis, SMAD-3 modulation is likely a key mechanism by which GSK-3β regulates fibrotic remodeling in the ischemic heart. Indeed, our studies clearly suggest that activation of TGF-β1-SMAD-3 signaling following deletion of GSK-3β in cardiac fibroblasts is the primary mechanism leading to adverse fibrotic remodeling and ventricular dysfunction. This conclusion is strongly supported by our studies with the small molecule SMAD-3 inhibitor SIS3, which rescued the detrimental phenotypes observed in GSK-3β KO hearts. These results are consistent with the observations in SMAD-3 KO and SMAD-3+/− mice, which suggest that loss of SMAD-3 prevents fibrotic remodeling and attenuates adverse remodeling in both ischemic and pressure overloaded hearts.33, 34

In summary, we believe that we have identified a novel and central role of GSK-3β in regulating myocardial fibrotic remodeling in the infarcted heart. GSK-3β exerts these effects via direct regulation of the canonical TGF-β1-SMAD-3 signaling pathway. Clinically, pharmacological inhibitors targeting the GSK-3 family of kinases have been proposed for several select diseases. Given the profound findings of the present study, we are concerned that adverse fibrotic remodeling with any such inhibitory agents should raise caution especially in the setting of long-term use post MI.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Fig. S1. Analysis of GSK-3β upstream activator and downstream targets post-MI. A, WT mice were subjected to MI surgery at 2 months of age. Western blotting was performed on the heart lysates at three wks post-MI. B&C, Quantification of upstream activator P-AKT473 and P-AKT308. D&E, Quantification of downstream targets cyclinD1 and c-myc.

Supplementary Fig. S2. Tamoxifen inducible GSK-3β deletion in Col-KO mice.

A, WT and Col-KO mice were placed on a tamoxifen chow diet (400mg/kg) for 28 days followed by regular chow for an additional 15 days. Cardiac fibroblasts and cardiomyocytes were isolated and Western blotting was performed. Representative Immunoblot demonstrates 60% deletion of GSK-3β in GSK-3β KO fibroblasts. B, Quantification of GSK-3β expression in GSK-3β KO fibroblasts versus WT fibroblasts. C, Quantification of GSK-3β expression in cardiomyocytes from fibroblasts specific KO hearts.

Supplementary Fig. S3. Periostin expression in the isolated cardiac fibroblasts.

A, Cardiac fibroblasts were isolated from 1–3 day old neonatal rat pups and were cultured up to three passages. Western blot analysis was performed to determine the expression of periostin. B, Bar graph shows quantification of fold changes in periostin expression.

Supplementary Fig. S4. Deletion of fibroblast GSK-3β does not affect MI size.

A, Representative images are triphenyltetrazolium chloride (TTC) stained heart sections from WT mice 48 hours post-MI showing infarct zone (white area), scale bar=1mm. (B) Infarct size was quantified and expressed as a percentage of the total area of the LV myocardium.

Supplementary Fig. S5. Conditional deletion of fibroblast GSK-3β does not affect cardiac function at baseline. At 12 weeks of age, Col-KO mice were placed on a tamoxifen chow diet (400mg/kg) for 28 days. Mice were then followed with serial echocardiography at the time points as indicated. A, Left ventricular internal dimension at end-diastole (LVID;d). B, LVID at end-systole (LVID;s). C, left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF). D, LV fractional shortening (LVFS).

Supplementary Fig. S6. Conditional deletion of fibroblast GSK-3β leads to cardiac dysfunction and dilatative remodeling post-MI

Four month old WT and Col-KO mice underwent baseline transthoracic echocardiographic examination. Twenty-four hours later they were subjected to occlusion of the proximal left anterior descending coronary artery. Mice were then followed with serial echocardiography at the time points shown. A, Left ventricular internal dimension at end-diastole (LVID;d). B, LVID at end-systole (LVID;s). C, left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF). D, LV fractional shortening (LVFS). BL, baseline; WT, Wild type; KO, Knockout

Supplementary Fig. S7. Effect of fibroblast specific GSK-3β deletion on post-MI mortality

A, WT and per-KO mice were subjected to MI or sham surgery and survival was monitored for 6 weeks. Survival was analyzed by the Kaplan-Meier method, and differences between groups were determined by Log-rank (Mantel-Cox) test.

Supplementary Fig. S8. Conditional deletion of GSK-3β in fibroblasts promotes post-MI scar expansion and fibrosis

Four-month-old WT and Col-KO mice were subjected to MI surgery for 6 weeks, as described in Materials and Methods. A, Representative images of heart sections stained with Masson trichrome at 6 week’s post-MI vs sham surgery. B, scar circumference was measured and expressed as a percentage of total area of LV myocardium.

Supplementary Fig. S9. In-vivo pharmacological inhibition of SMAD-3.

Mice were subjected to occlusion of the proximal left anterior descending coronary artery. Mice were treated with vehicle or SIS3, delivered by implantation of an Alzet osmotic pump, 1wks post-MI. A, at 8 weeks post-MI western blot analysis was performed with the LV lysates to determine the efficacy of SIS3. B, Bar graphs show fold changes in phosphorylation of SMAD-3 at Ser423/425.

Supplementary Fig. S10. SIS3 mediated protection of cardiac function post-MI.

WT mice underwent baseline transthoracic echocardiographic examination. Twenty-four hours later they were subjected to occlusion of the proximal left anterior descending coronary artery. Mice were treated with vehicle or SIS3, delivered by implantation of an Alzet osmotic pump starting from 1wk post-MI. Echocardiography was performed to access the heart function at 8 weeks post-MI. A, left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF). B, LV fractional shortening (LVFS). SIS, SMAD-3 inhibitor SIS3

Supplementary Table: List of antibodies used in the study.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the NHLBI to T. Force (HL061688, HL091799) CIHR operating grant (FRN 12858) to J.W. and American Heart Association Scientist Development Grant (13SDG16930103) to H.L.

Footnotes

Disclosure: None.

References

- 1.Chen W, Frangogiannis NG. Fibroblasts in post-infarction inflammation and cardiac repair. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2012 doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2012.08.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lijnen PJ, Maharani T, Finahari N, Prihadi JS. Serum collagen markers and heart failure. Cardiovasc Hematol Disord Drug Targets. 2012;12:51–55. doi: 10.2174/187152912801823147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dobaczewski M, Bujak M, Li N, Gonzalez-Quesada C, Mendoza LH, Wang XF, Frangogiannis NG. Smad3 signaling critically regulates fibroblast phenotype and function in healing myocardial infarction. Circ Res. 2010;107:418–428. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.109.216101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Weber KT, Sun Y, Bhattacharya SK, Ahokas RA, Gerling IC. Myofibroblast-mediated mechanisms of pathological remodelling of the heart. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2013;10:15–26. doi: 10.1038/nrcardio.2012.158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Melchior-Becker A, Dai G, Ding Z, Schafer L, Schrader J, Young MF, Fischer JW. Deficiency of biglycan causes cardiac fibroblasts to differentiate into a myofibroblast phenotype. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:17365–17375. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.192682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hecker L, Vittal R, Jones T, Jagirdar R, Luckhardt TR, Horowitz JC, Pennathur S, Martinez FJ, Thannickal VJ. Nadph oxidase-4 mediates myofibroblast activation and fibrogenic responses to lung injury. Nat Med. 2009;15:1077–1081. doi: 10.1038/nm.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Davis J, Burr AR, Davis GF, Birnbaumer L, Molkentin JD. A trpc6-dependent pathway for myofibroblast transdifferentiation and wound healing in vivo. Dev Cell. 2012;23:705–715. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2012.08.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Akhurst RJ, Hata A. Targeting the tgfbeta signalling pathway in disease. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2012;11:790–811. doi: 10.1038/nrd3810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Massague J. Tgfbeta signalling in context. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2012;13:616–630. doi: 10.1038/nrm3434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Woulfe KC, Gao E, Lal H, Harris D, Fan Q, Vagnozzi R, DeCaul M, Shang X, Patel S, Woodgett JR, Force T, Zhou J. Glycogen synthase kinase-3beta regulates post-myocardial infarction remodeling and stress-induced cardiomyocyte proliferation in vivo. Circ Res. 2010;106:1635–1645. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.109.211482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Haq S, Choukroun G, Kang ZB, Ranu H, Matsui T, Rosenzweig A, Molkentin JD, Alessandrini A, Woodgett J, Hajjar R, Michael A, Force T. Glycogen synthase kinase-3beta is a negative regulator of cardiomyocyte hypertrophy. J Cell Biol. 2000;151:117–130. doi: 10.1083/jcb.151.1.117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kerkela R, Kockeritz L, Macaulay K, Zhou J, Doble BW, Beahm C, Greytak S, Woulfe K, Trivedi CM, Woodgett JR, Epstein JA, Force T, Huggins GS. Deletion of gsk-3beta in mice leads to hypertrophic cardiomyopathy secondary to cardiomyoblast hyperproliferation. J Clin Invest. 2008;118:3609–3618. doi: 10.1172/JCI36245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Matsuda T, Zhai P, Maejima Y, Hong C, Gao S, Tian B, Goto K, Takagi H, Tamamori-Adachi M, Kitajima S, Sadoshima J. Distinct roles of gsk-3alpha and gsk-3beta phosphorylation in the heart under pressure overload. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:20900–20905. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0808315106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Takeda N, Manabe I, Uchino Y, Eguchi K, Matsumoto S, Nishimura S, Shindo T, Sano M, Otsu K, Snider P, Conway SJ, Nagai R. Cardiac fibroblasts are essential for the adaptive response of the murine heart to pressure overload. J Clin Invest. 2010;120:254–265. doi: 10.1172/JCI40295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kong P, Christia P, Saxena A, Su Y, Frangogiannis NG. Lack of specificity of fibroblast specific protein (fsp)1 in cardiac remodeling and fibrosis. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2013 doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00395.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Oka T, Xu J, Kaiser RA, Melendez J, Hambleton M, Sargent MA, Lorts A, Brunskill EW, Dorn GW, 2nd, Conway SJ, Aronow BJ, Robbins J, Molkentin JD. Genetic manipulation of periostin expression reveals a role in cardiac hypertrophy and ventricular remodeling. Circ Res. 2007;101:313–321. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.107.149047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lorts A, Schwanekamp JA, Baudino TA, McNally EM, Molkentin JD. Deletion of periostin reduces muscular dystrophy and fibrosis in mice by modulating the transforming growth factor-beta pathway. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:10978–10983. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1204708109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Saxena A, Fish JE, White MD, Yu S, Smyth JW, Shaw RM, DiMaio JM, Srivastava D. Stromal cell-derived factor-1alpha is cardioprotective after myocardial infarction. Circulation. 2008;117:2224–2231. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.694992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Balsam LB, Wagers AJ, Christensen JL, Kofidis T, Weissman IL, Robbins RC. Haematopoietic stem cells adopt mature haematopoietic fates in ischaemic myocardium. Nature. 2004;428:668–673. doi: 10.1038/nature02460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Souders CA, Bowers SL, Baudino TA. Cardiac fibroblast: The renaissance cell. Circ Res. 2009;105:1164–1176. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.109.209809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Turner NA, Porter KE. Function and fate of myofibroblasts after myocardial infarction. Fibrogenesis Tissue Repair. 2013;6:5. doi: 10.1186/1755-1536-6-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bonniaud P, Kolb M, Galt T, Robertson J, Robbins C, Stampfli M, Lavery C, Margetts PJ, Roberts AB, Gauldie J. Smad3 null mice develop airspace enlargement and are resistant to tgf-beta-mediated pulmonary fibrosis. J Immunol. 2004;173:2099–2108. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.3.2099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bae E, Kim SJ, Hong S, Liu F, Ooshima A. Smad3 linker phosphorylation attenuates smad3 transcriptional activity and tgf-beta1/smad3-induced epithelial-mesenchymal transition in renal epithelial cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2012;427:593–599. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2012.09.103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cohen-Solal KA, Merrigan KT, Chan JL, Goydos JS, Chen W, Foran DJ, Liu F, Lasfar A, Reiss M. Constitutive smad linker phosphorylation in melanoma: A mechanism of resistance to transforming growth factor-beta-mediated growth inhibition. Pigment Cell Melanoma Res. 2011;24:512–524. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-148X.2011.00858.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Velden JL, Alcorn JF, Guala AS, Badura EC, Janssen-Heininger YM. C-jun n-terminal kinase 1 promotes transforming growth factor-beta1-induced epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition via control of linker phosphorylation and transcriptional activity of smad3. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2011;44:571–581. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2009-0282OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wang G, Matsuura I, He D, Liu F. Transforming growth factor-{beta}-inducible phosphorylation of smad3. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:9663–9673. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M809281200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hill CS. Nucleocytoplasmic shuttling of smad proteins. Cell Res. 2009;19:36–46. doi: 10.1038/cr.2008.325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schmierer B, Tournier AL, Bates PA, Hill CS. Mathematical modeling identifies smad nucleocytoplasmic shuttling as a dynamic signal-interpreting system. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:6608–6613. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0710134105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chen X, Xu L. Mechanism and regulation of nucleocytoplasmic trafficking of smad. Cell Biosci. 2011;1:40. doi: 10.1186/2045-3701-1-40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Porter KE, Turner NA. Cardiac fibroblasts: At the heart of myocardial remodeling. Pharmacol Ther. 2009;123:255–278. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2009.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Duan J, Gherghe C, Liu D, Hamlett E, Srikantha L, Rodgers L, Regan JN, Rojas M, Willis M, Leask A, Majesky M, Deb A. Wnt1/betacatenin injury response activates the epicardium and cardiac fibroblasts to promote cardiac repair. EMBO J. 2012;31:429–442. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2011.418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.van den Borne SW, Diez J, Blankesteijn WM, Verjans J, Hofstra L, Narula J. Myocardial remodeling after infarction: The role of myofibroblasts. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2010;7:30–37. doi: 10.1038/nrcardio.2009.199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zeisberg EM, Tarnavski O, Zeisberg M, Dorfman AL, McMullen JR, Gustafsson E, Chandraker A, Yuan X, Pu WT, Roberts AB, Neilson EG, Sayegh MH, Izumo S, Kalluri R. Endothelial-to-mesenchymal transition contributes to cardiac fibrosis. Nat Med. 2007;13:952–961. doi: 10.1038/nm1613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bujak M, Ren G, Kweon HJ, Dobaczewski M, Reddy A, Taffet G, Wang XF, Frangogiannis NG. Essential role of smad3 in infarct healing and in the pathogenesis of cardiac remodeling. Circulation. 2007;116:2127–2138. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.704197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Fig. S1. Analysis of GSK-3β upstream activator and downstream targets post-MI. A, WT mice were subjected to MI surgery at 2 months of age. Western blotting was performed on the heart lysates at three wks post-MI. B&C, Quantification of upstream activator P-AKT473 and P-AKT308. D&E, Quantification of downstream targets cyclinD1 and c-myc.

Supplementary Fig. S2. Tamoxifen inducible GSK-3β deletion in Col-KO mice.

A, WT and Col-KO mice were placed on a tamoxifen chow diet (400mg/kg) for 28 days followed by regular chow for an additional 15 days. Cardiac fibroblasts and cardiomyocytes were isolated and Western blotting was performed. Representative Immunoblot demonstrates 60% deletion of GSK-3β in GSK-3β KO fibroblasts. B, Quantification of GSK-3β expression in GSK-3β KO fibroblasts versus WT fibroblasts. C, Quantification of GSK-3β expression in cardiomyocytes from fibroblasts specific KO hearts.

Supplementary Fig. S3. Periostin expression in the isolated cardiac fibroblasts.

A, Cardiac fibroblasts were isolated from 1–3 day old neonatal rat pups and were cultured up to three passages. Western blot analysis was performed to determine the expression of periostin. B, Bar graph shows quantification of fold changes in periostin expression.

Supplementary Fig. S4. Deletion of fibroblast GSK-3β does not affect MI size.

A, Representative images are triphenyltetrazolium chloride (TTC) stained heart sections from WT mice 48 hours post-MI showing infarct zone (white area), scale bar=1mm. (B) Infarct size was quantified and expressed as a percentage of the total area of the LV myocardium.

Supplementary Fig. S5. Conditional deletion of fibroblast GSK-3β does not affect cardiac function at baseline. At 12 weeks of age, Col-KO mice were placed on a tamoxifen chow diet (400mg/kg) for 28 days. Mice were then followed with serial echocardiography at the time points as indicated. A, Left ventricular internal dimension at end-diastole (LVID;d). B, LVID at end-systole (LVID;s). C, left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF). D, LV fractional shortening (LVFS).

Supplementary Fig. S6. Conditional deletion of fibroblast GSK-3β leads to cardiac dysfunction and dilatative remodeling post-MI

Four month old WT and Col-KO mice underwent baseline transthoracic echocardiographic examination. Twenty-four hours later they were subjected to occlusion of the proximal left anterior descending coronary artery. Mice were then followed with serial echocardiography at the time points shown. A, Left ventricular internal dimension at end-diastole (LVID;d). B, LVID at end-systole (LVID;s). C, left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF). D, LV fractional shortening (LVFS). BL, baseline; WT, Wild type; KO, Knockout

Supplementary Fig. S7. Effect of fibroblast specific GSK-3β deletion on post-MI mortality

A, WT and per-KO mice were subjected to MI or sham surgery and survival was monitored for 6 weeks. Survival was analyzed by the Kaplan-Meier method, and differences between groups were determined by Log-rank (Mantel-Cox) test.

Supplementary Fig. S8. Conditional deletion of GSK-3β in fibroblasts promotes post-MI scar expansion and fibrosis

Four-month-old WT and Col-KO mice were subjected to MI surgery for 6 weeks, as described in Materials and Methods. A, Representative images of heart sections stained with Masson trichrome at 6 week’s post-MI vs sham surgery. B, scar circumference was measured and expressed as a percentage of total area of LV myocardium.

Supplementary Fig. S9. In-vivo pharmacological inhibition of SMAD-3.

Mice were subjected to occlusion of the proximal left anterior descending coronary artery. Mice were treated with vehicle or SIS3, delivered by implantation of an Alzet osmotic pump, 1wks post-MI. A, at 8 weeks post-MI western blot analysis was performed with the LV lysates to determine the efficacy of SIS3. B, Bar graphs show fold changes in phosphorylation of SMAD-3 at Ser423/425.

Supplementary Fig. S10. SIS3 mediated protection of cardiac function post-MI.

WT mice underwent baseline transthoracic echocardiographic examination. Twenty-four hours later they were subjected to occlusion of the proximal left anterior descending coronary artery. Mice were treated with vehicle or SIS3, delivered by implantation of an Alzet osmotic pump starting from 1wk post-MI. Echocardiography was performed to access the heart function at 8 weeks post-MI. A, left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF). B, LV fractional shortening (LVFS). SIS, SMAD-3 inhibitor SIS3

Supplementary Table: List of antibodies used in the study.