Abstract

Purpose of review

The role of innate immunity in systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) has been a rapidly expanding area of research over the last decade. Included in this rubric is the concept that activation of the inflammasome, a molecular complex that activates caspase-1 and in turn, the cytokines IL-1β and IL-18, is important in lupus pathogenesis. This review will summarize recent discoveries exploring the role of the inflammasome machinery in SLE.

Recent findings

Immune complexes can activate the NLRP3 inflammasome, and SLE-derived macrophages are hyper-responsive to innate immune stimuli, leading to enhanced activation of the inflammasome and production of inflammatory cytokines. Work in several murine models suggests an important role for the NLRP3 inflammasome in mediating lupus nephritis. Caspase-1, the central enzyme of the inflammasome, is essential for development of type I interferon responses, autoantibody production and nephritis in the pristane model of lupus. The AIM2 inflammasome may have protective and pathogenic roles in SLE.

Summary

Recent evidence suggests that the inflammasome machinery is dysregulated in SLE, plays an important role in promotion of organ damage, and may mediate cross-talk between environmental triggers and the development of lupus. Further research should focus on whether inhibition of inflammasome components may serve as a viable target for therapeutic development in SLE.

Keywords: Inflammasome, lupus, IL-18, caspase-1, NLRP3

Introduction

Systemic Lupus Erythematosus (SLE) is an autoimmune syndrome characterized by formation of autoantibodies to nuclear components, immune complex deposition and inflammatory cell-mediated organ damage. Significant progress has been made over the past decade describing the putative role of innate immune processes in disease pathogenesis. These abnormalities include stimulation of toll-like receptor (TLR) signaling by immune complexes, activation of persistent type I interferon (IFN) responses, and hyperproduction of neutrophil NETs(1–4). In the past few years, another innate immune signaling complex, the inflammasome, has garnered support for a role in promoting organ damage and contributing to the SLE phenotype. This review will discuss the recent evidence that implicates the inflammasome in SLE pathogenesis.

The inflammasome

The inflammasome is a term used to describe a complex of molecules that, when induced to oligomerize, result in the activation of caspase-1, the primary enzyme responsible for activation of the pro-inflammatory cytokines IL-1β and IL-18 (reviewed in (5)). Activation of the inflammasome, particularly in the context of intracellular infections, may also result in an inflammatory form of cell death dependent on caspase-1, termed pyroptosis(6). Most inflammasomes involve a NOD-like receptor (NLR), such as NLRP3, which contains a C-terminal leucine rich repeat domain, a central NACHT nucleotide binding domain and an N-terminal PYRIN domain, which is able to interact with the PYRIN domain of the adaptor ASC. ASC is able to recruit caspase-1 via its CARD domain resulting in oligomerization of multiple caspase-1 molecules that in turn cleave and activate each other (reviewed in(7)). Other inflammasomes are formed from scaffolds not related to the NOD-like receptor. These include Absent in Melanoma 2 (AIM2), IFN-γ inducible protein 16 (IFI16) and retinoic acid inducible gene I (RIG-I). These proteins are able to assemble inflammasomes in response to cytosolic nucleic acids. They also play important roles in induction of antiviral type I interferon (IFN) responses. How the cytokine activation and IFN regulating roles of non-NLR inflammasomes are regulated is still an area of investigation (7).

Regulation of inflammasome activity occurs at multiple levels. NLRP3 and IL-1β are not constitutively expressed. They require a “priming” step, usually stimulation by toll-like receptor (TLR) ligands, which subsequently activate NFκB and their transcription (8). De-ubiquitination of NLRP3 has also been reported as an important intermediate step for inflammasome priming(9). Final activation of the inflammasome depends on the presence of unique ligands or cellular metabolic changes which result in assembly of the complex. These include stimuli as diverse as bacterial peptidoglycans, nucleic acids and crystalline materials (10–12).

The inflammasome is a recognized central pathogenic player in several rheumatologic diseases. The inherited cryopyrinopathies stem from activating mutations in NLRP3 leading to increased IL-1β production(13). Gout and pseudogout involve joint inflammation secondary to activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome by monosodium urate and calcium pyrophosphate crystals respectively(12). Research is also ongoing into the role of the inflammasome in diseases such as inflammatory bowel disease, type II diabetes and metabolic syndrome(14–16). Importantly, a role for inflammasome in SLE pathogensis is emerging (Table 1).

Table 1.

Summary of inflammasome scaffolds and their links to SLE.

| Inflammasome Scaffold | Activation Triggers | Links to SLE |

|---|---|---|

| NLRP1 | Bacillus anthracis lethal toxin | Genetic polymorphisms associated with SLE |

| NLRP3 | Crystalline material, potassium efflux, immune complexes, C3a, UVB radiation, microbial PAMPs, mitochondrial destabilization | Upregulated in diseased tissue, inhibition improves disease in murine models |

| NLRC4/IPAF | Salmonella typhimurium, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Legionella pneumophila, Shigella flexneri infection | None reported |

| AIM2 | Double-stranded DNA; DNA viruses, Francisella tularensis and Listeria monocytogenes infection | Inhibition provides resistance to apoptotic DNA-induced lupus phenotype but also increases type I IFN responses through upregulation of p202 |

| IFI-16 | DNA | None reported |

| RIG-I | RNA | May facilitate CCL5 upregulation in nephritis but no links with its inflammasome activity known |

CCL5=chemokine ligand 5, PAMPs=pathogen-associated molecular patterns, SLE=systemic lupus erythematosus

Genetic Evidence for a Role for the Inflammasome in SLE

Advanced genetic techniques have enhanced autoimmune disease research by finding important targets for study. Polymorphisms in the inflammasome scaffold, NLRP1, have previously been highly associated with vitiligo and type I diabetes(17). The same polymorphisms in this gene are also highly associated with the development of SLE and correlate with the phenotypes of nephritis, arthritis and cutaneous lesions(18). These polymorphisms lead to increased IL-1β production from circulating monocytes (19). Other inflammasome genes, including NLRP3, AIM2, NLRC4 and CASP1 were not associated with increased risk for SLE in the same study(18). The role of genetic polymorphisms in the cytokines activated by the inflammasome has also been examined. Several polymorphisms in the promoter of IL18 have been related to increased risk of SLE in several different ethnic populations(20*, 21*). Despite several studies, no convincing evidence for IL-1β polymorphisms contributing to SLE risk has been documented(18, 22).

Activation of the Inflammasome in SLE

Increased expression of inflammasome components, including NLRP3 and caspase-1 has been reported in lupus nephritis biopsies(23), suggesting that this tissue may be primed for inflammasome activation. How the inflammasome is triggered in SLE is an important concept for understanding its role in this disease. Immune complexes formed secondary to antibody recognition of DNA or RNA antigens, have been shown to stimulate inflammasome activation through upregulation of TLR-dependent activation of NFκB and subsequent activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome(24, 25**). Importantly, the use of chloroquine, an antimalarial that interferes with TLR7 and 9 activation in the lysosomal compartment, is able to block the stimulation of IL-1β release following stimulation of monocytes with RNA or DNA immune complexes(24, 25**). C3a, which is released during complement activation in tissues, promotes inflammasome activation through upregulation of ATP secretion(26*). Together, these results support the notion that immune complex deposition and complement consumption in organs affected by SLE promote activation of the inflammasome and may contribute to organ damage through this mechanism. Neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs) have also been proposed to play a pathogenic role in SLE. These structures are released spontaneously by a subset of proinflammatory lupus neutrophils termed low density granulocytes (LDGs) (4) and contribute to immune complex formation and type I IFN synthesis(27). Recently, NETs have been shown to activate caspase-1, resulting in release of IL-1β and IL-18, and this activation was enhanced in macrophages derived from SLE patients(28*). Importantly, IL-18 is able to induce NETosis, suggesting that NET activation of the inflammasome can result in a feed-forward loop in which inflammasome-activated IL-18 stimulates a perpetual cycle of NET formation and inflammasome activation(28*). This mechanism yields an intriguing possibility as to how infection or other triggers can spark a disease flare in SLE patients.

C1q, the deficiency of which is a strong risk factor for development of SLE(29), has important inhibitory functions on type I IFN responses in plasmacytoid dendritic cells(30). Recently, C1q, when presented in the context of apoptotic lymphocytes, was also demonstrated to repress the expression of NLRP3 in human monocyte-derived macrophages(31). Importantly, following phagocytosis of C1q-coated apoptotic lymphocytes, activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome by LPS and ATP was inhibited(31). These results suggest that the absence of C1q may contribute to SLE development through multiple pathways, including release of suppressive effects on inflammasome activation during phagocytosis.

Lupus Nephritis

The NLRP3 inflammasome has received a significant amount of attention as a contributor to lupus nephritis in murine models. Daily treatment of NZB/NZW F1 mice with epigallocatechin-3-gallate, a major bioactive polyphenol in green tea, reduced renal inflammation and suppressed upregulation of NLRP3 and activation of IL-1β and IL-18 in the kidneys of these mice. No suppression of anti-dsDNA antibodies or activation of T or B cells was observed in this model(32). Signaling through many TLR receptors activates NLRP3 expression via activation of NFκB(8) and thus acts as an important priming step for inflammasome inhibition. Recently, it has been suggested that the beneficial effects of TLR7, 8 and 9 inhibition in NZBW/F1 murine lupus models stem at least partially through blockade of NLRP3 upregulation(33*). Further demonstrating the important of this pathway, inhibition of NLRP3 expression by use of inhibitors of NFκB was able to protect MRL/lpr mice from nephritis and demonstrated a 50% reduction in anti-dsDNA titers(34*). NLRP3 inflammasome activation has also been demonstrated in other models of renal injury(35), so it remains to be determined whether inhibition of NLRP3 function will benefit more than lupus-related renal injury.

In addition to NLRP3, the importance of caspase-1 in the development of murine lupus has also been recognized. In a recent study, caspase-1 −/− mice were shown to be resistant to develop lupus using the pristane model. Compared to wild-type mice, caspase-1 −/− mice had significant reductions in both anti-dsDNA and anti-RNP autoantibody titers, abrogation of a type I IFN signature and were protected from both renal immune complex deposition and kidney inflammation(36**). Inhibition of the P2X7 receptor, a well-studied activator of NLRP3 and caspase-1(37), has also shown beneficial effects in lupus nephritis in both MRL/lpr and NZM 2328 mice. Indeed, inhibition of this receptor via brilliant blue G or via siRNA knockdown of P2X7 blocked development of anti-dsDNA antibodies, immune complex deposition and renal inflammation (38**). Blockade of High-mobility group box 1 protein (HMGB1), a danger signal that circulates on nucleosome and NET-derived complexes at higher levels in SLE(3, 39) has also shown success in abrogating caspase-1 activation and lupus nephritis in BXSB mice(40*).

The inflammasome scaffold AIM2 has also been studied for its role in SLE pathogenesis. AIM2 binds cytoplasmic DNA and induces inflammasome activation through recruitment of the adaptor molecule ASC through its pyrin domain(41). Balb/c mice induced to develop a lupus-like syndrome by repeated injection of apoptotic DNA have elevated levels of AIM2 expression in multiple organs, which correlates with disease progression. Further, these mice have a diminished lupus-like phenotype when AIM2 is knocked down(42*). Others, however, have demonstrated that inhibition of AIM2 may promote lupus pathogenesis. In mice, another interferon-inducible p200 family member, p202, is upregulated in many lupus-prone strains(43, 44). p202 negatively regulates AIM2 inflammasome activation, consequently decreasing cell death and promoting prolonged type I IFN production in response to cytosolic DNA(45*). Inhibition of AIM2 results in upregulation of p202(46). Importantly, in T and B cells, type I IFN exposure results in suppression of AIM2 and upregulation of p202(47). This could thus lead to a vicious cycle of type I IFN production. Thus, the inhibition of AIM2 may be a double edged sword with regards to lupus pathogenesis.

Cutaneous Lupus (CLE)

While the inflammasome itself has not been well-studied in cutaneous lupus, the inflammasome-activated cytokine IL-18 has been proposed as an important pathogenic mediator of cutaneous lupus lesions. IL-18 appears to play an important role in atopic dermatitis (reviewed in (48)), but is less well-studied in lupus. This cytokine is highly upregulated in the epidermis of cutaneous lupus, but not control, skin biopsies(49). IL-18 exposure induces upregulation of MHC class II and the chemokine CXCL10, which may be important for recruitment and activation of inflammatory cells(50). Additionally, keratinocytes isolated from subacute cutaneous lupus lesions upregulate TNF-α after IL-18 stimulation, which increases keratinocyte sensitivity to apoptosis, leading to enhanced exposure of modified autoantigens. These effects of IL-18 were not noted in control keratinocytes(49). Interestingly, UV light has been reported to activate the inflammasome in keratinocytes(51), but whether this contributes to enhanced photosensitivity in SLE patients remains to be determined.

Cardiovascular Disease

SLE patients demonstrate up to a 50-fold increased risk of cardiovascular disease (CVD)(52). The detrimental effects of type I IFNs in the vasculature of SLE patients has been proposed to be a primary pathogenic mediator of this risk (reviewed in(53). One mechanism in which type I IFNs impact vascular health is through their detrimental effects on growth and differentiation of endothelial progenitor cells, which are important for vascular repair(54). Type I IFNs repress expression of the pro-angiogenic cytokine IL-1β(55). Importantly, type I IFNs have also been shown to upregulate NLRP3, caspase-1 and IL-18 in human EPC cultures, which results in enhanced production of IL-18. IL-18, in turn, has inhibitory effects on EPC differentiation to mature endothelial cells(23). Inhibition of caspase-1 in these cultures prevents the detrimental effects of type I IFNs (23), and absence of functional caspase-1 also renders murine bone marrow EPC cultures resistant to the detrimental effects of pristane-induced lupus on EPC function and improves endothelial function in vivo(36**). Thus, the balance of IL-1β and IL-18 production via inflammasome activation, as influenced by type I IFN exposure, may have important consequences for vascular health in SLE.

Cholesterol crystals, which accumulate in atherosclerotic plaques, are able to stimulate inflammasome activation, and this activation is required for atherosclerosis development in the LDL-receptor knockout model of atherosclerosis(14). Interestingly, a role for complement activation in enhancing the activation of the inflammasome in response to cholesterol crystals has recently been documented(56*). Whether immune complex mediated complement activation and deposition can enhance inflammasome activation in SLE CVD remains to be explored.

The Importance of Inflammasome-generated cytokines in SLE

IL-18 has been postulated as important in SLE as noted above. Serum levels of this cytokine are elevated in SLE patients and correlate with disease severity, autoantibody profiles and the presence of lupus nephritis (23, 57–59). Moreover, IL-18 transcripts are elevated in glomeruli and tubulointerstitial compartments from patients with lupus nephritis(60), and serum levels correlate with the severity of lupus nephritis and degree of proteinuria(61*). Inhibition of IL-18 function in the murine lupus model MRL-Faslpr suggests a role for IL-18 in SLE nephritis and skin disease(62, 63), and reductions in IL-18 transcripts have been associated with improvement in murine lupus nephritis models(64). Unlike IL-18, increased serum levels of IL-1β are not commonly observed in SLE patients and have not been sufficiently linked to lupus pathogenesis(65).

Modulation of Inflammasome Activity in SLE

Therapeutic intervention for SLE patients may have modulating effects on inflammasome activity. Hydroxychloroquine has not been shown to significantly modify inflammatory cytokine levels in patients after six months of therapy(65). However, others have shown that chloroquine is able to reduce inflammasome activation by immune complexes(24, 25). Glucocorticoids induce expression of NLRP3 and enhance its activation and IL-1β secretion by ATP in vitro (66). In vivo, glucocorticoids may also have a positive effect on NLRP3, NLRP1, caspase-1 and IL-1β expression in SLE patients(67). A recent paper suggests that methotrexate is able to stimulate IL-1β production in a cultured monocytic cell line, but it is unclear whether this is related to induction of cell death. These findings were not able to be replicated in primary human PBMCs(68), thus the in vivo effects of methotrexate on inflammasome activity remain unclear. Further exploration into how treatments for SLE impact inflammasome activity are needed.

Conclusion

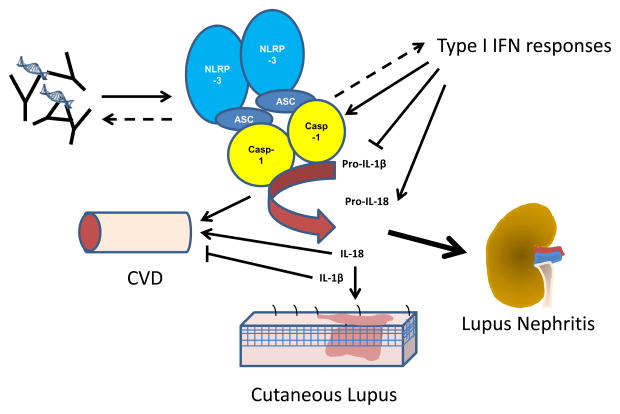

SLE is a heterogeneous disease with wide-ranging manifestations. The research discussed above suggests that the inflammasome is emerging as an important player in lupus pathogenesis (Figure 1). Consideration of the role of the inflammasome in further mechanistic studies of this disease is warranted. Targeting of the NLRP3 inflammasome appears to be a promising therapeutic avenue for lupus nephritis and further research is needed to understand whether other organ damage can be prevented with inhibition of this complex.

Figure 1.

The inflammasome is activated in SLE and contributes to disease pathogenesis. Immune complexes, neutrophil NETs and type I IFN responses may enhance inflammasome activation in SLE. This results in increased production of IL-18, which contributes to cutaneous lesion development, cardiovascular disease risk and nephritis. A role for caspase-1 in promoting type I IFN responses and autoantibody generation has also been noted in the pristane model of lupus. The NLRP3 inflammasome has also been implicated as an important contributor to lupus nephritis. CVD=cardiovascular disease, IFN=interferon.

Key Points.

Activation of the inflammasome by SLE-specific immune complexes, complement activation or neutrophil NETs may contribute to organ inflammation and propagation of aberrant immune responses.

Inhibition of NLRP3, caspase-1 and IL-18 has shown benefit to nephritis in various murine models of lupus.

Activation of caspase-1 contributes to endothelial progenitor cell dysfunction and may promote vascular damage in SLE.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the Intramural Research Program at the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases, National Institutes of Health and the Alliance for Lupus Research (M.J.K). J.M.K. was supported by the PHS grant ARK08AR063668.

References

- 1.Savarese E, Chae OW, Trowitzsch S, et al. U1 small nuclear ribonucleoprotein immune complexes induce type I interferon in plasmacytoid dendritic cells through TLR7. Blood. 2006 Apr 15;107(8):3229–34. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-07-2650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kirou KA, Lee C, George S, et al. Activation of the interferon-alpha pathway identifies a subgroup of systemic lupus erythematosus patients with distinct serologic features and active disease. Arthritis Rheum. 2005 May;52(5):1491–503. doi: 10.1002/art.21031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Garcia-Romo GS, Caielli S, Vega B, et al. Netting neutrophils are major inducers of type I IFN production in pediatric systemic lupus erythematosus. Sci Transl Med. 2011 Mar 9;3(73):73ra20. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3001201. Epub 2011/03/11. eng. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Villanueva E, Yalavarthi S, Berthier CC, et al. Netting neutrophils induce endothelial damage, infiltrate tissues, and expose immunostimulatory molecules in systemic lupus erythematosus. J Immunol. 2011 Jul 1;187(1):538–52. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1100450. Epub 2011/05/27. eng. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lamkanfi M, Dixit VM. Inflammasomes and Their Roles in Health and Disease. Annual Review of Cell and Developmental Biology. 2012;28(1):137–61. doi: 10.1146/annurev-cellbio-101011-155745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Miao EA, Leaf IA, Treuting PM, et al. Caspase-1-induced pyroptosis is an innate immune effector mechanism against intracellular bacteria. Nat Immunol. 2010;11(12):1136–42. doi: 10.1038/ni.1960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Latz E, Xiao TS, Stutz A. Activation and regulation of the inflammasomes. Nat Rev Immunol. 2013 Jun;13(6):397–411. doi: 10.1038/nri3452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bauernfeind FG, Horvath G, Stutz A, et al. Cutting Edge: NF-κB Activating Pattern Recognition and Cytokine Receptors License NLRP3 Inflammasome Activation by Regulating NLRP3 Expression. The Journal of Immunology 2009. 2009 Jul 15;183(2):787–91. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0901363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Juliana C, Fernandes-Alnemri T, Kang S, et al. Non-transcriptional Priming and Deubiquitination Regulate NLRP3 Inflammasome Activation. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2012. 2012 Oct 19;287(43):36617–22. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.407130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Franchi L, Kanneganti T-D, Dubyak GR, Núñez G. Differential Requirement of P2X7 Receptor and Intracellular K+ for Caspase-1 Activation Induced by Intracellular and Extracellular Bacteria. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2007. 2007 Jun 29;282(26):18810–8. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M610762200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Franchi L, Muñoz-Planillo R, Reimer T, et al. Inflammasomes as microbial sensors. European Journal of Immunology. 2010;40(3):611–5. doi: 10.1002/eji.200940180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rock KL, Kataoka H, Lai J-J. Uric acid as a danger signal in gout and its comorbidities. Nature reviews. 2013 Jan;9(1):13–23. doi: 10.1038/nrrheum.2012.143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Agostini L, Martinon F, Burns K, et al. NALP3 forms an IL-1beta-processing inflammasome with increased activity in Muckle-Wells autoinflammatory disorder. Immunity. 2004 Mar;20(3):319–25. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(04)00046-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Duewell P, Kono H, Rayner KJ, et al. NLRP3 inflammasomes are required for atherogenesis and activated by cholesterol crystals. Nature. 2010 Apr 29;464(7293):1357–61. doi: 10.1038/nature08938. Epub 2010/04/30. eng. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stienstra R, van Diepen JA, Tack CJ, et al. Inflammasome is a central player in the induction of obesity and insulin resistance. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011 Sep 13;108(37):15324–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1100255108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zaki MH, Lamkanfi M, Kanneganti TD. The Nlrp3 inflammasome: contributions to intestinal homeostasis. Trends Immunol. 2011 Apr;32(4):171–9. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2011.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jin Y, Mailloux CM, Gowan K, et al. NALP1 in vitiligo-associated multiple autoimmune disease. The New England journal of medicine. 2007 Mar 22;356(12):1216–25. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa061592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pontillo A, Girardelli M, Kamada A, et al. Polimorphisms in inflammasome genes are involved in the predisposition to systemic lupus erythematosus. Autoimmunity. 2012;45(4):271–8. doi: 10.3109/08916934.2011.637532. Epub 2012 Feb 7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Levandowski CB, Mailloux CM, Ferrara TM, et al. NLRP1 haplotypes associated with vitiligo and autoimmunity increase interleukin-1beta processing via the NLRP1 inflammasome. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013 Feb 19;110(8):2952–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1222808110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *20.Song G, Choi S, Ji J, Lee Y. Association between interleukin-18 polymorphisms and systemic lupus erythematosus: a meta-analysis. Molecular Biology Reports. 2013 Mar 01;40(3):2581–7. doi: 10.1007/s11033-012-2344-y. English. This meta-analysis examined three polymorphisms of IL-18 and their association with SLE risk, including stratification by ethnicity. This paper demonstrated some but not all IL-18 polymorphisms may contribute to SLE. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *21.Wen D, Liu J, Du X, et al. Association of interleukin-18 (−137G/C) polymorphism with rheumatoid arthritis and systemic lupus erythematosus: a meta-analysis. International reviews of immunology. 2014 Jan;33(1):34–44. doi: 10.3109/08830185.2013.816699. This study demonstrated a link of −137G/C polymorphism in the IL-18 gene with SLE risk in Asian populations. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang B, Zhu JM, Fan YG, et al. The association of IL1alpha and IL1beta polymorphisms with susceptibility to systemic lupus erythematosus: a meta-analysis. Gene. 2013 Sep 15;527(1):95–101. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2013.05.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kahlenberg JM, Thacker SG, Berthier CC, et al. Inflammasome activation of IL-18 results in endothelial progenitor cell dysfunction in systemic lupus erythematosus. J Immunol. 2011 Dec 1;187(11):6143–56. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1101284. Epub 2011/11/08. eng. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shin MS, Kang Y, Lee N, et al. U1-Small Nuclear Ribonucleoprotein Activates the NLRP3 Inflammasome in Human Monocytes. The journal of immunology 2012. 2012 May 15;188(10):4769–75. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1103355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- **25.Shin MS, Kang Y, Lee N, et al. Self Double-Stranded (ds)DNA Induces IL-1β Production from Human Monocytes by Activating NLRP3 Inflammasome in the Presence of Anti–dsDNA Antibodies. The journal of immunology. 2013 Jan 11;2013 doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1201195. This study demonstrated activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome in human monocytes by dsDNA complexes created from SLE serum. Activation was dependent on TLR9 activation of NFκB, reactive oxygen species generation and potassium efflux. This observation suggests a mechanism by which the inflammasome may be stimulated in SLE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *26.Asgari E, Le Friec G, Yamamoto H, et al. C3a modulates IL-1β secretion in human monocytes by regulating ATP efflux and subsequent NLRP3 inflammasome activation. Blood 2013. 2013 Nov 14;122(20):3473–81. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-05-502229. This paper demonstrates an enhancer role for C3a in stimulating IL-1β release from LPS stimulated monocytes through activation of intracellular ATP release. C3a is activated by immune complex deposition and thus may contribute to SLE pathogenesis. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lande R, Ganguly D, Facchinetti V, et al. Neutrophils Activate Plasmacytoid Dendritic Cells by Releasing Self-DNA-Peptide Complexes in Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. Sci Transl Med. 2011 Mar 9;3(73):73ra19. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3001180. Epub 2011/03/11. eng. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *28.Kahlenberg JM, Carmona-Rivera C, Smith CK, Kaplan MJ. Neutrophil Extracellular Trap–Associated Protein Activation of the NLRP3 Inflammasome Is Enhanced in Lupus Macrophages. The journal of immunology 2013. 2013 Feb 1;190(3):1217–26. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1202388. This paper demonstrated that lupus macrophages have enhanced inflammasome activation in response to neutrophil extracellular traps and LL-37. IL-18 released from these macrophages can stimulate NETosis and promote a viscious cycle of inflammasome activation and NET release. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Manderson AP, Botto M, Walport MJ. The role of complement in the development of systemic lupus erythematosus. Annual review of immunology. 2004;22:431–56. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.22.012703.104549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Santer DM, Hall BE, George TC, et al. C1q deficiency leads to the defective suppression of IFN-alpha in response to nucleoprotein containing immune complexes. J Immunol. 2010 Oct 15;185(8):4738–49. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1001731. Epub 2010/09/17. eng. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Benoit ME, Clarke EV, Morgado P, et al. Complement Protein C1q Directs Macrophage Polarization and Limits Inflammasome Activity during the Uptake of Apoptotic Cells. The Journal of Immunology 2012. 2012 Jun 1;188(11):5682–93. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1103760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tsai PY, Ka SM, Chang JM, et al. Epigallocatechin-3-gallate prevents lupus nephritis development in mice via enhancing the Nrf2 antioxidant pathway and inhibiting NLRP3 inflammasome activation. Free Radic Biol Med. 2011 Aug 1;51(3):744–54. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2011.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *33.Zhu FGJW, Bhagat L, Wang D, Yu D, Tang JX, Kandimalla ER, La Monica N, Agrawal S. A novel antagonist of Toll-like receptors 7, 8 and 9 suppresses lupus disease-associated parameters in NZBW/F1 mice. Autoimmunity. 2013;46(7):419–28. doi: 10.3109/08916934.2013.798651. This paper demonstrated that blockade of TLR 7,8 and 9 receptors reduced renal disease and inhibition of IL-1β production in NZBW/F1 mice. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *34.Zhao J, Zhang H, Huang Y, et al. Bay11-7082 attenuates murine lupus nephritis via inhibiting NLRP3 inflammasome and NF-κB activation. International Immunopharmacology. 2013;17(1):116–22. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2013.05.027. This paper used an inhibitor of NFκB in MRL/lpr mice, which reduced nephritis, autoantibody formation and renal IL-1β production. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Vilaysane A, Chun J, Seamone ME, et al. The NLRP3 Inflammasome Promotes Renal Inflammation and Contributes to CKD. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology 2010. 2010 Oct 1;21(10):1732–44. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2010020143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- **36.Kahlenberg JM, Yalavarthi S, Zhao W, et al. An essential role for caspase-1 in the induction of murine lupus and its associated vascular damage. Arthritis Rheum. 2014 Oct 14;66(1):153–62. doi: 10.1002/art.38225. Epub 2013/10/16. Eng. This is the first paper to utilize a knock-out model to examine the role of the inflammasome in murine lupus. Absence of caspase-1 was protective in that mice exposed to pristane did not develop chronic IFN signatures, autoantibodies or nephritis. Lack of caspase-1 was also protective for cardiovascular measures in this model. This observation solidifies the importance of the inflammasome in renal inflammation and also suggests that caspase-1 may be important in other areas of SLE pathogenesis. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bours MJ, Dagnelie PC, Giuliani AL, et al. P2 receptors and extracellular ATP: a novel homeostatic pathway in inflammation. Frontiers in bioscience. 2011;3:1443–56. doi: 10.2741/235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- **38.Zhao J, Wang H, Dai C, et al. P2X7 Blockade Attenuates Murine Lupus Nephritis by Inhibiting Activation of the NLRP3/ASC/Caspase 1 Pathway. Arthritis & Rheumatism. 2013;65(12):3176–85. doi: 10.1002/art.38174. This paper demonstrated an upregulation of the NLRP3 inflammasome pathways in the kidneys of MRL/lpr mice. They also demonstrated that chemical inhibition or siRNA knockdown of the P2X7 receptor, a known activator of the inflammasome, was sufficient to improve renal disease in this model. Blockade of P2X7 receptor function also abrogated proteinuria and autoantibody levels the NZM2328 with IFN-accelerated lupus. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Urbonaviciute V, Fürnrohr BG, Meister S, et al. Induction of inflammatory and immune responses by HMGB1–nucleosome complexes: implications for the pathogenesis of SLE. The Journal of Experimental Medicine 2008. 2008 Dec 22;205(13):3007–18. doi: 10.1084/jem.20081165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *40.Zhang C, Li C, Jia S, et al. High mobility group box 1 inhibition alleviates lupus-like disease in BXSB mice. Scandinavian journal of immunology. 2014 doi: 10.1111/sji.12165. epub ahead of print. This paper demonstrates that neutralizing antibodies to HMGB1 reduce IL-1β, IL-18 and improve renal disease in BXSB mice. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fernandes-Alnemri T, Yu J-W, Datta P, et al. AIM2 activates the inflammasome and cell death in response to cytoplasmic DNA. Nature. 2009;458(7237):509–13. doi: 10.1038/nature07710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *42.Zhang W, Cai Y, Xu W, et al. AIM2 Facilitates the Apoptotic DNA-induced Systemic Lupus Erythematosus via Arbitrating Macrophage Functional Maturation. Journal of clinical immunology. 2013 Jul 01;33(5):925–37. doi: 10.1007/s10875-013-9881-6. English. This paper demonstrates that AIM2 is upregulated in macrophages exposed to apoptotic DNA and that knock-down of AIM2 improved the lupus phenotype in response to apototic DNA exposure. This paper suggests a pathogenic role of AIM2 in lupus. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Panchanathan R, Xin H, Choubey D. Disruption of mutually negative regulatory feedback loop between interferon-inducible p202 protein and the E2F family of transcription factors in lupus-prone mice. J Immunol. 2008 May 1;180(9):5927–34. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.9.5927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Haywood ME, Rose SJ, Horswell S, et al. Overlapping BXSB congenic intervals, in combination with microarray gene expression, reveal novel lupus candidate genes. Genes Immun. 2006 Apr;7(3):250–63. doi: 10.1038/sj.gene.6364294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *45.Yin Q, Sester DP, Tian Y, et al. Molecular mechanism for p202-mediated specific inhibition of AIM2 inflammasome activation. Cell reports. 2013 Jul 25;4(2):327–39. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2013.06.024. This paper demonstrated that p202 is able to inhibit AIM2 inflammasome activation via interaction with the HIN domain of AIM2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Panchanathan R, Duan X, Shen H, et al. Aim2 Deficiency Stimulates the Expression of IFN-Inducible Ifi202, a Lupus Susceptibility Murine Gene within the Nba2 Autoimmune Susceptibility Locus. The Journal of Immunology 2010. 2010 Dec 15;185(12):7385–93. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1002468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Panchanathan R, Duan X, Arumugam M, et al. Cell type and gender-dependent differential regulation of the p202 and Aim2 proteins: implications for the regulation of innate immune responses in SLE. Mol Immunol. 2011 Oct;49(1–2):273–80. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2011.08.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wittmann M, Macdonald A, Renne J. IL-18 and skin inflammation. Autoimmunity Reviews. 2009;9(1):45–8. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2009.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wang D, Drenker M, Eiz-Vesper B, et al. Evidence for a pathogenetic role of interleukin-18 in cutaneous lupus erythematosus. Arthritis & Rheumatism. 2008;58(10):3205–15. doi: 10.1002/art.23868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wittmann M, Purwar R, Hartmann C, et al. Human Keratinocytes Respond to Interleukin-18: Implication for the Course of Chronic Inflammatory Skin Diseases. J Investig Dermatol. 2005;124(6):1225–33. doi: 10.1111/j.0022-202X.2005.23715.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Feldmeyer L, Keller M, Niklaus G, et al. The Inflammasome Mediates UVB-Induced Activation and Secretion of Interleukin-1β by Keratinocytes. Current Biology. 2007;17(13):1140–5. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2007.05.074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Manzi S, Meilahn EN, Rairie JE, et al. Age-specific incidence rates of myocardial infarction and angina in women with systemic lupus erythematosus: comparison with the Framingham Study. American Journal of Epidemiology. 1997;145(5):408–15. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kaplan MJ, Salmon JE. How does interferon-α insult the vasculature? Let me count the ways. Arthritis & Rheumatism. 2011;63(2):334–6. doi: 10.1002/art.30161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Denny MF, Thacker S, Mehta H, et al. Interferon-alpha promotes abnormal vasculogenesis in lupus: a potential pathway for premature atherosclerosis. Blood. 2007 Oct 15;110(8):2907–15. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-05-089086. Epub 2007/07/20. eng. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Thacker S, Berthier C, Mattinzoli D, et al. The detrimental effects of IFN-α on vasculogenesis in lupus are mediated by repression of IL-1 pathways: potential role in atherogenesis and renal vascular rarefaction. The journal of immunology. 2010;185(7):4457–69. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1001782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *56.Samstad EO, Niyonzima N, Nymo S, et al. Cholesterol Crystals Induce Complement-Dependent Inflammasome Activation and Cytokine Release. The Journal of Immunology 2014. 2014 Mar 15;192(6):2837–45. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1302484. This paper demonstrated that cholesterol chrystals are able to activate both the classical and alternative complement pathways. Activation of complement by cholesterol was able to enhance cholesterol crystal activation of the inflammasome. This suggests that complement activation by contribute to atherosclerosis development via enhancement of inflammasome activation by cholesterol crystals. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Tucci M, Quatraro C, Lombardi L, et al. Glomerular accumulation of plasmacytoid dendritic cells in active lupus nephritis: role of interleukin-18. Arthritis and rheumatism. 2008;58(1):251–62. doi: 10.1002/art.23186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hu D, Liu X, Chen S, Bao C. Expressions of IL-18 and its binding protein in peripheral blood leukocytes and kidney tissues of lupus nephritis patients. Clin Rheumatol. 2010 Feb 8;29(7):717–21. doi: 10.1007/s10067-010-1386-6. Epub 2010/02/09. Eng. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Calvani N, Richards HB, Tucci M, et al. Up-regulation of IL-18 and predominance of a Th1 immune response is a hallmark of lupus nephritis. Clinical and experimental immunology. 2004;138(1):171–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2004.02588.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kahlenberg JM, Thacker SG, Berthier CC, et al. Inflammasome Activation of IL-18 Results in Endothelial Progenitor Cell Dysfunction in Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. J Immunol. 2011 Nov 4; doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1101284. Epub 2011/11/08. Eng. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *61.Hatef MR, Sahebari M, Rezaieyazdi Z, et al. Stronger Correlation between Interleukin 18 and Soluble Fas in Lupus Nephritis Compared with Mild Lupus. ISRN rheumatology. 2013;2013:850851. doi: 10.1155/2013/850851. This study confirmed an increase in serum IL-18 associated with the onset of proteinuria in patients with lupus nephritis. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Menke J, Bork T, Kutska B, et al. Targeting transcription factor Stat4 uncovers a role for interleukin-18 in the pathogenesis of severe lupus nephritis in mice. Kidney international. 2011;79(4):452–63. doi: 10.1038/ki.2010.438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kinoshita K, Yamagata T, Nozaki Y, et al. Blockade of IL-18 Receptor Signaling Delays the Onset of Autoimmune Disease in MRL-Faslpr Mice. The journal of immunology 2004. 2004 Oct 15;173(8):5312–8. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.8.5312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Tsai P-Y, Ka S-M, Chang J-M, et al. Antroquinonol differentially modulates T cell activity and reduces interleukin-18 production, but enhances Nrf2 activation, in murine accelerated severe lupus nephritis. Arthritis & Rheumatism. 2012;64(1):232–42. doi: 10.1002/art.33328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Willis R, Seif A, McGwin G, et al. Effect of hydroxychloroquine treatment on pro-inflammatory cytokines and disease activity in SLE patients: data from LUMINA (LXXV), a multiethnic US cohort. Lupus 2012. 2012 Jul 1;21(8):830–5. doi: 10.1177/0961203312437270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Busillo JM, Azzam KM, Cidlowski JA. Glucocorticoids Sensitize the Innate Immune System through Regulation of the NLRP3 Inflammasome. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2011. 2011 Nov 4;286(44):38703–13. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.275370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Yang Q, Yu C, Yang Z, et al. Deregulated NLRP3 and NLRP1 Inflammasomes and Their Correlations with Disease Activity in Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. The Journal of Rheumatology 2014. 2013 Dec 15;41(3) doi: 10.3899/jrheum.130310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Olsen N, Spurlock C, Aune T. Methotrexate induces production of IL-1 and IL-6 in the monocytic cell line U937. Arthritis Research & Therapy. 2014;16(1):R17. doi: 10.1186/ar4444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]