Abstract

Ecological models of physical activity emphasize the effects of environmental influences. “Microscale” streetscape features that may affect pedestrian experience have received less research attention than macroscale walkability (e.g., residential density). The Microscale Audit of Pedestrian Streetscapes (MAPS) measures street design, transit stops, sidewalk qualities, street crossing amenities, and features impacting aesthetics. The present study examined associations of microscale attributes with multiple physical activity (PA) measures across four age groups. Areas in the San Diego, Seattle, and the Baltimore metropolitan areas, USA, were selected that varied on macro-level walkability and neighborhood income. Participants (n=3677) represented four age groups (children, adolescents, adults, older adults). MAPS audits were conducted along a 0.25 mile route along the street network from participant residences toward the nearest non-residential destination. MAPS data were collected in 2009–2010. Subscale and overall summary scores were created. Walking/biking for transportation and leisure/neighborhood PA were measured with age-appropriate surveys. Objective PA was measured with accelerometers. Mixed linear regression analyses were adjusted for macro-level walkability. Across all age groups 51.2%, 22.1%, and 15.7% of all MAPS scores were significantly associated with walking/biking for transport, leisure/neighborhood PA, and objectively-measured PA, respectively. Supporting the ecological model principle of behavioral specificity, destinations and land use, streetscape, street segment, and intersection variables were more related to transport walking/biking, while aesthetic variables were related to leisure/neighborhood PA. The overall score was related to objective PA in children and older adults. Present findings provide strong evidence that microscale environment attributes are related to PA across the lifespan. Improving microscale features may be a feasible approach to creating activity-friendly environments.

Keywords: United States, built environment, walkability, direct observation, city planning, older adults, adolescents, children

Introduction

Ecological models of health behavior focus attention on the potential broad reach and long-term effects of environmental influences, and such models have been widely applied to physical activity (Sallis, Owen, & Fisher, 2008). Many built environment characteristics have been related to physical activity (Bauman et al., 2012). Environmental variables fall into two broad categories: macroscale, consisting of structural features such as street inter-connectivity and land use mix (Brownson, Hoehner, Day, Forsyth, & Sallis, 2009); and microscale, or details that can affect the experience of being active in a place, such as aesthetics and sidewalk design (Sallis et al., 2011b). Most research has focused on macroscale variables that characterize walkability (Frank et al., 2010) or park access (Brownson et al., 2009), but studying microscale features may also be useful for understanding physical activity (Moudon & Lee, 2003). Microscale characteristics of the pedestrian environment, such as street crossing design and quality of sidewalks, can be modified at lower cost and in a shorter time-frame than reconfiguring the macroscale design.

The small literature on microscale features assessed by direct observation in relation to physical activity is encouraging. Pikora et al. (2002, 2006) showed that well-maintained walking surfaces, destinations, and public transit were correlated with walking for transport or recreation. Boarnet, Forsyth, Day, & Oakes (2011) found sidewalk infrastructure, crossing and street characteristics, traffic calming, parking structure type, and building design mix were associated with physical activity, while aesthetics, negative land uses, and lighting were not. Hoehner, Ramirez, Elliot, Handy, & Brownson (2005) found active transportation was positively related to public transit and bike lanes, but negatively associated with aesthetics. However, there are not enough studies of microscale features to support conclusions about consistent correlates of physical activity (Bauman et al., 2012). The literature is further limited by inconsistent definitions and scoring, few studies of youth and older adults, and failure to control for macroscale attributes.

The present study contributes to the literature by examining associations of microscale environmental attributes, using a reliable instrument and systematic scoring system (Millstein et al., 2013), with multiple physical activity measures, in four age groups.

Methods

Design of Three Studies That Provided Data

Objective microscale environmental data were collected as part of three studies examining the relation of neighborhood design to physical activity, nutrition behaviors, and weight status in children, adolescents, adults, and older adults. These studies were conducted in urban and suburban neighborhoods in Seattle/King County, WA, San Diego, CA, and the Baltimore, MD-Washington, DC region. Neighborhoods were selected to vary on macro-environment features and median income (Frank et al., 2010). Methods of the Senior Neighborhood Quality of Life Study (SNQLS) (King et al., 2011), Neighborhood Impact on Kids (NIK) (Frank et al., 2012; Saelens et al., 2012), and Teen Environment and Neighborhood study (TEAN) (Sallis et al., 2011a) have been reported. These studies were approved for research with human subjects by the Institutional Review Boards at San Diego State University, Seattle Children's Hospital, and Stanford University. Table 1 summarizes study characteristics and sample sizes for the MAPS evaluation.

Table 1.

Study characteristics: Neighborhood Impact on Kids (NIK), Teen Environment and Neighborhood (TEAN), and Senior Neighborhood Quality of Life Study (SNQLS)

| Study | Participant ages |

Study design |

Eligible destinations |

Regions | Sample size | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Routes | Segments | Crossings | Cul-de-sacs | |||||

| NIK | 6–11 and parent |

Hi/low Activitya X Hi/low Nutritionb |

Cluster of ≥3 commercial locations, parks, schools |

San Diego County, CA | 365 | 1285 | 675 | 154 |

| Seattle/King County, WA | 393 | 1196 | 581 | 153 | ||||

| TEAN | 12–16 and parent |

Hi/low Walkabilityc X Hi/low Incomed |

Cluster of ≥3 commercial locations, one park, one school |

Seattle/King County, WA | 427 | 1685 | 962 | 171 |

| Maryland-DC | 470 | 1643 | 938 | 105 | ||||

| SNQLS | 66+ | Hi/low Walkabilityc X Hi/low Incomed |

Cluster of ≥3 commercial locations, parks,schools |

Seattle/King County, WA | 462 | 1152 | 511 | --- |

GIS-defined block group walkability and park access

defined by the presence or absence of grocery stores and fast food restaurants

walkability index defined by GIS-derived residential density, intersection density, retail floor area ratio, and mixed use

based on 2000 census data for block group median household income

Microscale Audit of Pedestrian Streetscapes (MAPS)

Development and sections of tool

The MAPS direct observation instrument was adapted from previous tools (Millstein et al., 2013), primarily the Analytic Audit Tool (Brownson et al., 2004), as modified by the Healthy Aging Network (Kealey et al., 2005). MAPS has four sections: route, crossings, street segments and cul-de-sacs (available for download at http://sallis.ucsd.edu/measure_maps.html). Route-level items evaluated characteristics for a 0.25 mile route from the participant’s home towards pre-selected non-residential destinations. Items included land use and destinations, street amenities, and aesthetic and social characteristics. Segment-level (street segments between intersections) items assessed sidewalks, slope, buffers between street and sidewalk, bicycle facilities, building aesthetics, trees, setbacks of buildings from the sidewalk or street, and building height. Street crossing items assessed crosswalk markings, width of crossings, curbs, crossing signals, and pedestrian protection. Cul-de-sac items included size and condition of surface area, slope, and amenities within cul-de-sacs (e.g., basketball hoops).

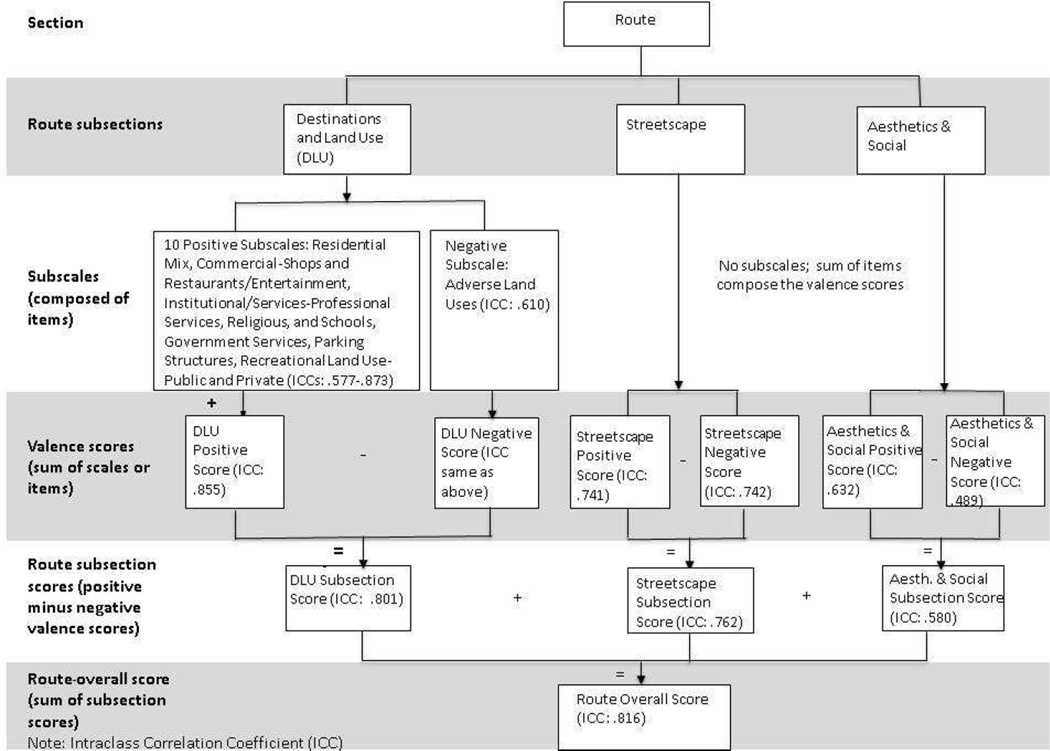

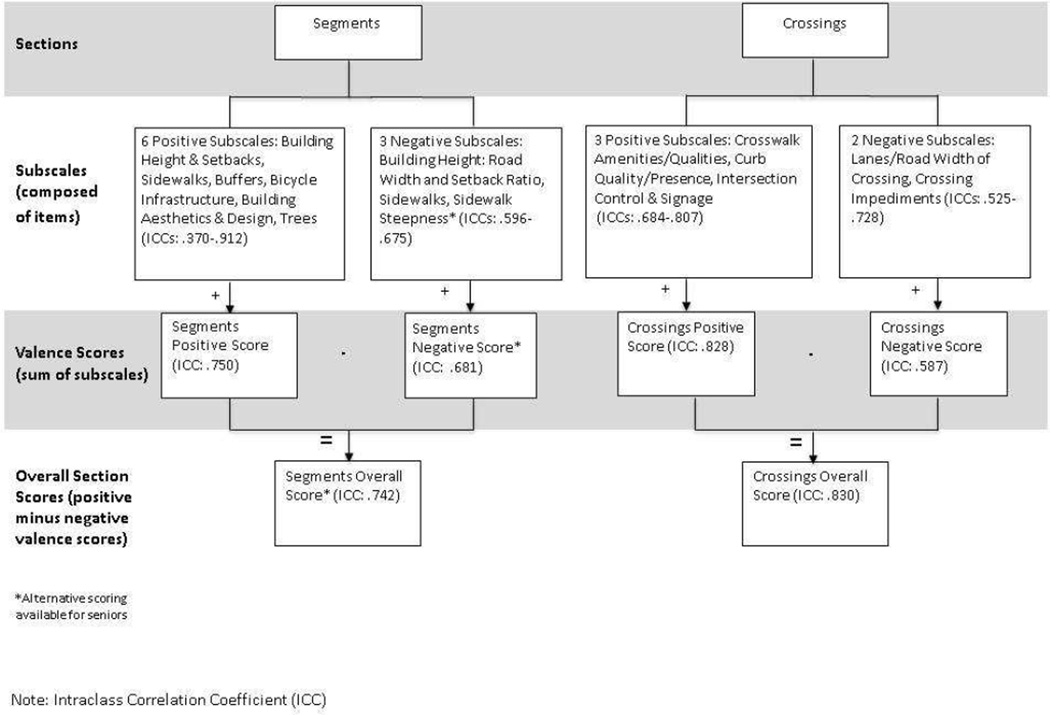

Subscale, Valence, Overall, and Grand Scores

The tiered scoring system summarized items into subscales at multiple levels of aggregation. Figures and 2 illustrate the hierarchy of scores from lowest to highest level of aggregation. The numbers of segments and crossings varied by route, so segment and crossing scores represent means for each route. All sections had positive and negative valence scores based on the expected effect on physical activity (e.g. crosswalk amenities were positive and crossing impediments were negative). Negative valence scores (higher scores indicated more negative attributes) were subtracted from positive valence scores (higher scores indicated more positive attributes) to create “overall” section scores. For example, if segment positive score is 10 and segment negative score is 6, then the segment overall score would be 4. Overall positive and negative valence scores were produced from the section valence scores, and a grand score was calculated by subtracting the overall negative valence score from the overall positive valence score. The cul-de-sac section had a single positive valence score that was not included in the overall scores because the expected direction of its relation to physical activity was unclear.

Figure 1.

MAPS scoring structure and summary of inter-rater reliability: Route section (one survey per participant)

Figure 2.

MAPS scoring structure and summary of inter-rater reliability: Segments and Crossings sections (multiple surveys per route)

Figures 1 and 2 reprinted from Millstein RA, Cain KL, Sallis JF, Conway TL, Geremia CM, Frank LD, Chapman J, Van Dyck D, Dipzinski L, Kerr J, Glanz K, Saelens BE. Development, Scoring, and Reliability of the Microscale Audit of Pedestrian Streetscapes(MAPS). BMC Public Health, 2013, 13:403. Copyright 2013, with author permission.

MAPS Data Collection

MAPS data were collected in 2009–2010. MAPS observations were conducted along a ¼ mile route starting at a study participant’s home and walking toward the nearest pre-determined destination (i.e. shops or services, a park, or a school) along the street network (Millstein et al., 2013). This is a distinct difference from other instruments that require observations of a sample of streets to characterize an area or neighborhood (Boarnet et al., 2011; Cerin, Chan, Macfarlane, Lee, & Lai, 2011). Route items were collected across the entire ¼ mile. When a street was crossed, a new crossing section was completed, along with a new segment section. Cul-de-sacs or street deadends within 400 feet of a participant’s home were rated in the NIK and TEAN studies only. MAPS audits were completed in 28.5 (SD=13.2) minutes on average. See manual for further details (Cain, Millstein, & Geremia, 2012). MAPS items and subscales demonstrated predominantly moderate to excellent inter-rater reliability (ICC values ≥.41 and ≥.60, respectively) (Millstein et al., 2013; Figures 1 and 2).

Physical Activity Measures

Walking and Biking for Transport

Children (parent-reported) and adolescents (self-reported) reported how often they usually walked or biked (0=never to 5=four or more times/week) to 9 common locations including recreation centers and a friend’s house. Responses were averaged (Grow et al., 2008). Parents of child and adolescent participants completed a survey about their own physical activity. Active transport was assessed using the Global Physical Activity Questionnaire (GPAQ), which has support for reliability and validity (Bull et al., 2009). The active transportation item assessed the number of days for walking and biking for transport during a typical week. Older adults completed the Community Healthy Activities Model Program for Seniors (CHAMPS) questionnaire, which has been validated with older populations (Stewart et al., 2001). Participants reported times per week they usually walked or biked to do errands (biking added in SNQLS). The sum of the two variables was log-transformed as it was skewed.

Leisure and Neighborhood Physical Activity

Children (parent-reported) and adolescents (self-reported) completed 5 questions about how often they were physically active in settings near home such as nearby street, sidewalk, or cul-de-sac (0=never to 5= four or more times a week). This scale was adapted from a measure with good test-retest reliability (Grow et al., 2008), and a mean was computed. Parents reported the time per typical day they spent in leisure physical activity on the GPAQ (moderate and vigorous intensity items combined). For older adults, an item from the CHAMPS asking about time per week spent walking for leisure was used.

Accelerometer

Objective physical activity was measured using the Actigraph (models 7164/71256 for adolescents/older adults; GT1M/GT3X with Normal filter for children/adolescents; Pensacola, FL). Parents in NIK and TEAN did not wear accelerometers so there is no objective outcome for adults. Accelerometers collected data in either 30-second (children & adolescents) or 60-second epochs (older adults). Participants were asked to wear the accelerometer for seven consecutive days during waking hours (except when swimming or bathing). Upon return, Actigraphs were downloaded and screened for completeness using MeterPlus versions 4.0–4.3 (www.meterplussoftware.com). A valid day had at least 10 hours of wear time. Nonwearing time was 20, 30, or 45 minutes of consecutive zero counts for children, adolescents, and older adults, respectively (Cain, Sallis, Conway, Van Dyck & Calhoon, 2013). If the accelerometer did not record at least 5 wearing days for older adults and adolescents, or 6 for children (including at least 1 weekend day for adolescents and children), participants were asked to re-wear the device for the number of missing days. Data were included in analyses if there was at least one 10-hour wearing day.

For children and adolescents, data were scored using Freedson youth age-specific cut-points with a 4-MET moderate intensity threshold (Trost et al., 2002). Accelerometer variables analyzed for this study included only data collected during typical non-school hours (3pm – 11pm on weekdays and all weekend hours), and average daily minutes of moderate-to-vigorous physical activity (MVPA) during ‘non-school’ hours was computed. School-time accelerometer data were excluded because physical activity during school hours should be less related to the home neighborhood environment. Children had an additional accelerometer measure developed for NIK (Kneeshaw-Price et al., 2013). Parents of NIK participants completed a daily location log while the child wore the accelerometer. Time in neighborhood locations was linked via the accelerometer’s time stamp to the matching accelerometer data. Average daily minutes of MVPA ‘in the neighborhood’ was calculated using the Freedson youth age-specific 3-MET moderate-intensity threshold (Trost et al., 2002).

For older adults, accelerometer data were converted to minutes in MVPA using the Freedson adult cut-point (Freedson, Melanson, & Sirard, 1998), and average daily minutes of MVPA was computed.

Covariates

Demographic covariates assessed by survey were age, gender, education (parent education for children and adolescents), and race/ethnicity. Education was dichotomized (college degree or higher vs. less), and race was dichotomized into white/Non-Hispanic and non-white. Older adults reported on lower-extremity mobility impairment measured with the validated 11-item lower extremity subscale of the Late-Life Function and Disability Instrument (Sayers et al., 2004). Table 2 summarizes characteristics for the four study samples.

Table 2.

Participant characteristics for study populations

| Children n=758 |

Adolescents n=897 |

Adults n=1655 |

Older Adults n=367 |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean age(SD) | 9.1(1.6) | 14.1(1.4) | 44.0(27.0) | 75.0(6.6) |

| Percent female | 50.0 | 49.6 | 79.7 | 50.8 |

| Percent non-White | 31.4 | 33.3 | 24.2 | 16.2 |

| Percent with college degreea | 68.1 | 64.0 | 65.8 | 48.6 |

reported for parent of children and adolescents

GIS walkability

In all 3 studies, a GIS-based walkability value was calculated for each census block group by summing the z-scores of four macro built environment measures: 1) net residential density, 2) intersection density, 3) retail floor to land area ratio (FAR), and 4) mixed use (Frank et al., 2010). Each block group’s walkability index was used to categorize the block group into either high or low walkability.

Data Analysis

Data were analyzed using SPSS version 21.0 (Chicago, Il.). Mixed linear regression analyses were performed to assess the relationship of each MAPS score with physical activity outcomes for each age group, adjusting for all covariates as fixed effects and participant clustering in census block groups (per recruitment procedures) as a random effect. All statistical models were run both with and without adjusting for macro-level GIS-defined walkability (high/low). When the macro-level GIS measure is adjusted for in the model, any associations between physical activity outcomes with microscale measures of the pedestrian environment are independent of GIS-assessed macro-level walkability. T statistics from the macro-level adjusted and unadjusted mixed models are presented in Tables 3–5 instead of b estimates and CIs because measurement units and scales varied across the MAPS variables. T statistics (and significance levels) provide a common indicator for comparing relative magnitudes of association across MAPS scores.

Table 3.

Results from mixed regression of relations between MAPS scores and walking and biking for transport†. Reported with and without adjusting for macro-level walkability.

| Children | Adolescents | Adults | Older adults | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adjusteda | Unadjustedb | Adjusteda | Unadjustedb | Adjusteda | Unadjustedb | Adjusteda | Unadjustedb | |

| Destinations & Land Use | ||||||||

| Positive Characteristics | ||||||||

| Residential Mix | 1.403 | 2.840** | 1.989* | 3.435** | 4.396*** | 6.265*** | 2.351* | 3.729*** |

| Shops | 1.683 | 2.361* | 1.577 | 3.043** | 2.773** | 4.105*** | 4.758*** | 6.143*** |

| Restaurant-Entertainment | 3.093** | 3.442** | 2.090* | 3.483** | 3.756*** | 4.960*** | 4.960*** | 5.957*** |

| Institutional-Service | 2.754** | 3.645*** | 1.102 | 2.990** | 3.545*** | 5.352*** | 3.670*** | 5.794*** |

| Government-Service | −0.120 | 0.294 | 0.950 | 1.901 | 2.271* | 3.116** | 1.765 | 2.656** |

| Public Recreation | 0.651 | 1.750 | 1.026 | 2.071* | 1.784 | 2.842** | −0.807 | −0.412 |

| Private Recreation | 0.966 | 1.125 | 0.268 | 0.636 | −.688 | −.479 | 0.812 | 0.684 |

| Parking | 0.302 | 0.703 | −0.488 | 0.110 | 1.223 | 1.859 | −1.459 | −1.630 |

| Transit Stops | 2.256* | 3.411** | 2.270* | 3.973*** | 3.573*** | 5.469*** | 0.868 | 1.324 |

| Valence and Overall | ||||||||

| Positive | 3.017** | 4.301*** | 2.168* | 4.278*** | 4.376*** | 6.489*** | 5.101*** | 7.220*** |

| Negative | 0.282 | 1.096 | 1.282 | 1.963 | 1.500 | 2.571* | 1.562 | 2.036* |

| Overall | 3.269** | 4.500*** | 1.953 | 4.053*** | 4.326*** | 6.365*** | 4.928*** | 6.909*** |

| Streetscape Characteristics | ||||||||

| Valence and Overall | ||||||||

| Positive | 2.290* | 3.433** | 2.505* | 3.969*** | 3.764*** | 5.315*** | 1.390 | 2.105* |

| Negative | −2.610** | −3.621*** | −2.933** | −4.570*** | −2.762** | −4.696*** | −2.671** | −4.037*** |

| Overall | 2.760** | 4.024*** | 3.039** | 4.775*** | 4.015*** | 5.898*** | 2.030* | 3.101** |

| Aesthetics & Social Characteristics | ||||||||

| Valence and Overall | ||||||||

| Positive | 0.613 | 0.310 | 0.218 | 0.721 | −.677 | −.792 | 2.930** | −0.805 |

| Negative | −0.609 | −0.166 | 2.587* | 3.940*** | 3.328** | 4.512*** | −1.586 | 3.381** |

| Overall | 0.735 | 0.271 | −1.757 | −2.512* | −2.738** | −3.658*** | −2.996** | −2.936** |

| Crossings/Intersections | ||||||||

| Positive Characteristics | ||||||||

| Crosswalk Amenities | 2.849** | 3.524*** | 0.191 | 0.911 | .175 | 1.192 | 1.664 | 2.258* |

| Curb Quality | 2.538* | 3.088** | 0.011 | 1.063 | 1.738 | 2.594* | 2.307* | 3.510** |

| Intersection Control | 0.247 | 1.382 | 0.968 | 1.771 | −.370 | .907 | 2.718** | 3.581*** |

| Neqative Characteristics | ||||||||

| Road Width | 2.207* | 3.055** | 0.343 | 1.277 | 1.837 | 2.261* | −0.677 | −0.611 |

| Impediments | −2.944** | −3.308** | 0.938 | −0.226 | −2.124* | −2.923** | −2.650** | −3.911*** |

| Valence and Overall | ||||||||

| Positive | 2.464* | 3.512*** | 0.488 | 1.594 | .716 | 2.085* | 2.699** | 3.848*** |

| Negative | −1.815 | −1.752 | 1.036 | 0.336 | −1.212 | −1.797 | −2.636** | −3.693*** |

| Overall | 2.577* | 3.336** | −0.035 | 1.065 | 1.011 | 2.263* | 3.002** | 4.281*** |

| Street Segments | ||||||||

| Positive Characteristics | ||||||||

| Building Height-Setback | 3.080** | 4.514*** | 2.056* | 3.933*** | 3.374** | 5.242*** | 3.072** | 4.578*** |

| Building Height-Road Width Ratio | 0.828 | 1.276 | 0.032 | 1.062 | 2.530* | 3.467** | 1.648 | 3.014** |

| Buffer | 3.532*** | 5.229*** | 2.126* | 2.969** | 4.832*** | 6.510*** | 1.648 | 3.762*** |

| Bike Infrastructure | 0.355 | 0.278 | 0.974 | 1.497 | 2.708** | 3.080** | −0.488 | −.672 |

| Trees | 1.819 | 1.876 | 0.834 | 0.923 | 2.088* | 2.591* | 0.659 | 1.827 |

| Building Aesthetics/Design | 0.575 | 1.396 | 0.369 | 1.566 | 1.294 | 2.195* | 1.405 | 1.650 |

| Sidewalk | 4.353*** | 5.239*** | 1.529 | 3.365** | 3.842*** | 5.363*** | 1.855 | 3.527*** |

| Negative Characteristics | ||||||||

| Sidewalk Obstructions/Hazards | −4.066*** | −5.076*** | −1.319 | −2.436* | −2.700** | −3.795*** | −1.725 | −3.432** |

| Wide One-Way Street Designc | 0.354 | 0.607 | 1.148 | 2.613** | 2.758** | 3.862*** | .575 | 1.359 |

| Slope | −4.513*** | −5.589*** | −1.420 | −3.043** | −3.967*** | −5.221*** | −1.900 | −3.737*** |

| Valence and Overall | ||||||||

| Positive | 3.901*** | 5.210*** | 2.065* | 3.820*** | 5.084*** | 6.880*** | 2.692** | 4.795*** |

| Negative | −4.478*** | −5.540*** | −1.421 | −2.856** | −3.484** | −4.708*** | −1.774 | −3.529*** |

| Overall | 4.912*** | 6.215*** | 1.902 | 3.641*** | 4.791*** | 6.472*** | 2.605* | 4.867*** |

| Cul-De-Sacs | ||||||||

| Overalld | 0.546 | 0.189 | 1.152 | 1.296 | 0.257 | −0.233 | - | - |

| Grand Valence and Overall | ||||||||

| Overall Positive | 4.518*** | 6.172*** | 2.740** | 5.034*** | 5.095*** | 7.398*** | 4.573*** | 6.963*** |

| Overall Negative | −4.465*** | −5.348*** | −0.390 | −1.411 | −2.154* | −3.040** | −1.016 | −2.595* |

| Overall Grand Score | 5.543*** | 7.129*** | 2.304* | 4.523*** | 4.906*** | 7.091*** | 4.063*** | 6.570*** |

Values are t statistics. Significant results for walkability-adjusted models are bolded.

Walking/biking for transport measures: children & adolescents (frequency of walk/bike trips with Likert scale responses); adults (# days walk/bike for transport); older adults (# trips walk/bike for transport)

analyses adjusted for age, gender, education, race, GIS-defined walkability (high/low), physical functioning (older adults) and clustering of participants within block groups

analyses adjusted for age, gender, education, race, physical functioning (older adults) and clustering of participants within block groups

not included in negative segment or overall scores

not included in grand valence/overall scores

p ≤0.05

p ≤0.01

p ≤0.001

Table 5.

Results from mixed regression for relations between MAPS scores and objective MVPA†. Reported with and without adjusting for macro-level walkability.

| Children (in neighborhood) |

Children (non-school time) |

Adolescents (non-school time) |

Older adults | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adjusteda | Unadjustedb | Adjusteda | Unadjustedb | Adjusteda | Unadjustedb | Adjusteda | Unadjustedb | |

| Destinations & Land Use | ||||||||

| Positive Characteristics | ||||||||

| Residential Mix | 0.100 | 0.420 | 0.104 | −0.020 | −0.783 | −0.180 | 1.983* | 2.269* |

| Shops | 1.962 | 2.068* | 0.237 | 0.129 | 0.701 | 1.259 | 0.987 | 1.312 |

| Restaurant-Entertainment | 1.546 | 1.159 | −0.838 | −1.037 | 1.172 | 1.701 | 0.718 | 1.039 |

| Institutional-Service | 1.451 | 1.596 | 0.696 | 0.562 | −0.619 | 0.144 | −0.108 | 0.421 |

| Government-Service | −1.473 | −1.376 | 0.563 | 0.620 | −0.420 | −0.019 | −1.165 | −0.875 |

| Public Recreation | 0.899 | 0.723 | 0.833 | 0.274 | 1.553 | 1.958 | −0.326 | −0.278 |

| Private Recreation | 2.397* | 2.377* | 3.475** | 3.497** | 1.438 | 1.538 | −1.285 | −1.216 |

| Parking | −1.154 | −1.072 | 0.076 | 0.004 | −2.858** | −2.570* | −1.269 | −1.340 |

| Transit Stops | 0.593 | 0.780 | 0.615 | 0.405 | 1.091 | 1.730 | 0.840 | 0.969 |

| Valence and Overall | ||||||||

| Positive | 1.721 | 1.820 | 0.685 | 0.401 | 0.295 | 1.119 | 0.446 | 0.927 |

| Negative | −0.340 | −0.048 | 0.377 | 0.261 | −0.495 | −0.217 | −0.591 | −0.361 |

| Overall | 2.026* | 2.057* | 0.648 | 0.372 | 0.475 | 1.282 | 0.660 | 1.104 |

| Streetscape Characteristics | ||||||||

| Valence and Overall | ||||||||

| Positive | 0.656 | 0.784 | 2.035* | 1.958 | −0.068 | 0.542 | 1.157 | 1.376 |

| Negative | −0.620 | −0.740 | 0.237 | 0.478 | 0.021 | −0.629 | −0.949 | −1.254 |

| Overall | 0.746 | 0.884 | 1.611 | 1.436 | −0.063 | 0.650 | 1.291 | 1.564 |

| Aesthetics & Social Characteristics | ||||||||

| Valence and Overall | ||||||||

| Positive | 0.488 | 0.472 | 1.077 | 1.354 | −0.995 | −0.776 | −0.445 | −0.376 |

| Negative | −1.585 | −1.509 | −1.734 | −1.926 | 0.163 | 0.728 | −0.589 | −0.326 |

| Overall | 1.344 | 1.280 | 1.748 | 2.010* | −0.632 | −0.940 | 0.044 | 0.057 |

| Crossings/Intersections | ||||||||

| Positive Characteristics | ||||||||

| Crosswalk Amenities | −1.342 | −1.219 | −0.883 | −1.007 | 0.115 | 0.370 | 0.831 | 1.056 |

| Curb Quality | 2.088* | 2.299* | 0.727 | 0.217 | 0.974 | 1.370 | 2.421* | 2.662** |

| Intersection Control | −1.689 | −1.529 | −2.001* | −2.043* | 1.559 | 1.876 | 2.071* | 2.254* |

| Negative Characteristics | ||||||||

| Road Width | −0.216 | 0.057 | −0.879 | −1.047 | 0.794 | 1.164 | −0.862 | −0.859 |

| Impediments | −2.504* | −2.784** | −0.698 | −0.300 | −1.177 | −1.615 | −1.756 | −2.016* |

| Valence and Overall | ||||||||

| Positive | −0.273 | −0.024 | −0.938 | −1.241 | 1.129 | 1.544 | 2.109* | 2.355* |

| Negative | −2.650** | −2.771** | −1.136 | −0.842 | −0.787 | −1.061 | −1.926 | −2.156* |

| Overall | 0.851 | 1.096 | −0.242 | −0.596 | 1.147 | 1.560 | 2.307* | 2.559* |

| Street Segments | ||||||||

| Positive Characteristics | ||||||||

| Building Height-Setback | 0.471 | 0.949 | −1.727 | −2.279* | −1.462 | −0.650 | 2.695** | 2.976** |

| Building Height-Road Width Ratio | −0.838 | −0.861 | 2.170* | 2.000* | −0.339 | 0.081 | 3.229** | 3.494** |

| Buffer | 1.019 | 1.440 | 0.010 | −0.043 | 1.220 | 1.610 | .549 | 1.007 |

| Bike Infrastructure | −0.824 | −0.829 | −1.816 | −1.928 | 0.660 | 0.864 | .313 | 0.292 |

| Trees | 1.440 | 1.402 | −0.203 | 0.637 | 0.615 | 0.635 | 1.184 | 1.450 |

| Building Aesthetics/Design | 0.121 | 0.417 | −0.966 | −1.729 | −0.302 | 0.211 | .300 | 0.400 |

| Sidewalk | 2.159* | 2.483* | −0.324 | −0.415 | 1.903 | 2.507* | 1.477 | 1.816 |

| Negative Characteristics | ||||||||

| Sidewalk Obstructions/Hazards | −1.201 | 1.721 | 0.385 | 0.466 | −1.815 | −2.250* | −1.478 | −1.814 |

| Wide One-Way Street Designc | −0.069 | 0.081 | −2.165* | −2.154* | 1.149 | 1.732 | 1.034 | 1.250 |

| Slope | −2.663** | −3.082** | −0.205 | −0.124 | −1.240 | −1.821 | −1.057 | −1.442 |

| Valence and Overall | ||||||||

| Positive | 1.205 | 1.572 | −1.208 | −1.319 | 0.911 | 1.577 | 2.217* | 2.552* |

| Negative | −2.009* | −2.486* | 0.054 | 0.178 | −1.576 | −2.102* | −0.991 | −1.358 |

| Overall | 1.920 | 2.385* | −0.646 | −0.770 | 1.380 | 2.016* | 1.824 | 2.193* |

| Cul-De-Sacs | ||||||||

| Positived | 1.538 | 1.529 | 0.125 | −0.076 | 2.617** | 2.638** | − | − |

| Grand Valence and Overall | ||||||||

| Overall Positive | 2.043* | 2.316* | 0.412 | 0.160 | 0.534 | 1.421 | 1.906 | 2.275* |

| Overall Negative | −2.771** | −3.184** | −0.583 | −0.457 | −1.435 | −1.813 | −1.582 | −1.880 |

| Overall Grand Score | 2.863** | 3.191** | 0.597 | 0.338 | 1.010 | 1.828 | 2.218* | 2.547* |

Values are t statistics. Significant results for walkability-adjusted models are bolded.

Objective PA measures: children & adolescents (MVPA during non-school hours; Freedson youth 4METs), children (MVPA in the neighborhood; Freedson youth 3METs), older adults (total MVPA; Freedson 3METs)

analyses adjusted for age, gender, education, race, GIS-defined walkability (high/low), physical functioning (older adults) and clustering of participants within block groups

analyses adjusted for age, gender, education, race, physical functioning (older adults) and clustering of participants within block groups

not included in negative segment or overall scores

not included in grand valence/overall scores

p ≤0.05

p ≤0.01

Results

Effects of adjusting for walkability

Including macro-level walkability in the models did not have a major impact on the number of significant findings (48 lost significance; 8 gained; net loss of 40 of 193 significant findings), so only walkability-adjusted results are described below.

Walking and biking for transport

There were 88 significant associations with MAPS scores and walking/biking for transport across all age groups (51.2% of MAPS scores; Table 3).

Destinations and non-residential land use along the route were consistently related to walking/biking for transport in all age groups. There were 3 significant subscales for children, 3 for adolescents, 6 for adults, and 4 for older adults. Positive land uses were important, particularly restaurants-entertainment for all ages, shops for adults and older adults, and transit stops for children, adolescents and adults. Negative destinations and land uses (e.g., abandoned buildings, parking garages) were unrelated to active transport.

Streetscape characteristics were consistently related to walking/biking for transport in all age groups. Both positive and negative environmental aspects were related to active transport, but the overall score showed the strongest association among children, adolescents, and adults. In older adults, negatives were most related to this outcome.

Aesthetics and social characteristics were generally unrelated or “inversely” related to walking/biking for transport across age groups. Negative aesthetic/social features were related in an unexpected direction in adolescents and adults (i.e. higher scores associated with more active transport). Positive aesthetics/social features were related in the expected direction in older adults only.

Crossing characteristics were related to walking/biking for transport in children (3 subscales) and older adults (3 subscales) in the expected direction. Positive characteristics were important, particularly for children and older adults, as were negative impediments for children, adults, and older adults. Unexpectedly, road width was positively related in children (i.e. wider roads associated with more walking/biking for transport). The overall score was stronger than positive or negative valence scores for children and older adults.

Segment characteristics were significantly related to active transport in children (5 subscales), adolescents (2 subscales), adults (9 subscales), and older adults (1 subscale). Both positive and negative subscales were important; however, positive subscales were more consistent correlates of active transport across age groups.

The grand scores were related to walking/biking for transportation in all age groups. The overall positive score was related in all age groups and the overall negative score was related in children and adults. The grand score showed the strongest association in children while overall positive score showed the strongest association in adults, compared with all of the other scores.

Leisure and neighborhood physical activity

There were 38 significant associations with leisure/neighborhood physical activity across all age groups (22.1% of MAPS scores; Table 4). Relations with destinations and land use were generally negative or unrelated in all age groups with the exception of public recreation (positive association with children) and parking (positive association in children and adults). Aesthetics and social characteristics were related to neighborhood physical activity in children and leisure physical activity in adults, and the overall score was the strongest correlate in both groups. The cul-de-sac score was positively related to neighborhood physical activity for children and adolescents. A few other significant findings in the expected direction were found for curb quality, crossing impediments, and sidewalk slope and obstructions, but only in children. Several relationships were found with adolescents’ reported neighborhood physical activity, but the associations were in the unexpected direction.

Table 4.

Results from mixed regression for relations between MAPS scores and leisure and neighborhood physical activity†. Reported with and without adjusting for macro-level walkability.

| Children | Adolescents | Adults | Older adults | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adjusteda | Unadjustedb | Adjusteda | Unadjustedb | Adjusteda | Unadjustedb | Adjusteda | Unadjustedb | |

| Destinations & Land Use | ||||||||

| Positive Characteristics | ||||||||

| Residential Mix | −3.349** | −4.497** | −1.631 | −1.684 | −1.320 | −1.223 | 1.319 | 1.476 |

| Shops | −2.022** | −2.866** | −0.992 | −1.065 | −.861 | −.799 | 1.156 | 1.324 |

| Restaurant-Entertainment | −1.886 | −2.738** | −0.973 | −1.045 | .008 | −.043 | 0.686 | 0.877 |

| Institutional-Service | −2.582* | −3.475** | −1.180 | −1.253 | −1.352 | −1.219 | 0.366 | 0.662 |

| Government-Service | −1.127 | −1.172 | −0.248 | −0.311 | −1.666 | −1.580 | −0.084 | 0.107 |

| Public Recreation | 2.430* | 1.629 | −0.074 | −0.146 | 1.048 | .940 | 0.397 | 0.409 |

| Private Recreation | 1.749 | 1.498 | 0.089 | 0.069 | .852 | .810 | −1.691 | −1.621 |

| Parking | 2.091* | 2.631** | −1.051 | −1.089 | 2.041* | 2.048* | −4.073** | −4.124** |

| Transit Stops | −2.298* | −2.977** | −1.188 | −0.296 | −.084 | −0.122 | −0.078 | 0.024 |

| Valence and Overall | ||||||||

| Positive | −2.514* | −3.651** | −1.559 | −1.611 | −.875 | −.789 | 0.332 | 0.624 |

| Negative | −2.992** | −3.842** | −0.158 | −0.203 | −1.669 | −1.647 | −0.594 | −0.409 |

| Overall | −1.829 | −2.880** | −1.646 | −1.692 | −.433 | −.367 | 0.537 | 0.795 |

| Streetscape Characteristics | ||||||||

| Valence and Overall | ||||||||

| Positive | −1.492 | −1.869 | −1.798 | −1.847 | −.003 | −.082 | 1.267 | 1.400 |

| Negative | 1.932 | 2.744** | 1.593 | 1.649 | .742 | .700 | −0.565 | −0.756 |

| Overall | −1.871 | −2.443* | −2.007* | −2.044* | −.241 | −.294 | 1.267 | 1.421 |

| Aesthetics & Social Characteristics | ||||||||

| Valence and Overall | ||||||||

| Positive | 3.254** | 4.146** | −1.713 | −1.746 | 3.090** | 3.198** | 0.115 | 0.224 |

| Negative | −3.089** | −3.876** | 1.016 | 0.895 | −5.123** | −5.053** | 0.822 | 0.891 |

| Overall | 3.798** | 4.771** | −1.630 | −1.565 | 5.370** | 5.354** | −0.560 | −0.557 |

| Crossings/Intersections | ||||||||

| Positive Characteristics | ||||||||

| Crosswalk Amenities | 0.071 | −0.673 | −2.116* | −2.088* | .105 | .148 | 0.538 | 0.811 |

| Curb Quality | 1.982* | 1.464 | −1.457 | −1.410 | −1.305 | −1.129 | 1.150 | 1.445 |

| Intersection Control | −1.185 | −2.187* | −1.713 | −1.677 | −1.091 | −.933 | 1.642 | 1.884 |

| Negative Characteristics | ||||||||

| Road Width | 0.809 | 0.839 | −0.971 | −0.936 | .275 | .469 | −0.834 | −0.865 |

| Impediments | −2.150* | −1.625 | 1.467 | 1.411 | 1.539 | 1.236 | −0.671 | −0.990 |

| Valence and Overall | ||||||||

| Positive | 0.434 | −0.585 | −2.285* | −2.222* | −1.048 | −.871 | 1.315 | 1.624 |

| Negative | −1.731 | −1.200 | 0.973 | 0.947 | 1.627 | 1.434 | −0.978 | −1.266 |

| Overall | 1.026 | 0.044 | −2.082* | −2.023* | −1.424 | −1.211 | 1.350 | 1.673 |

| Street Segments | ||||||||

| Positive Characteristics | ||||||||

| Building Height-Setback | 0.899 | −0.134 | −1.404 | −1.468 | −.209 | −.146 | 2.925** | 2.981** |

| Building Height-Road Width Ratio | −0.427 | −0.724 | 0.079 | 0.010 | 1.000 | 1.018 | 2.735** | 2.797** |

| Buffer | −0.064 | −1.373 | 0.457 | 0.385 | −1.697 | −1.527 | −.018 | 0.289 |

| Bike Infrastructure | −1.553 | −1.822 | −1.344 | −1.373 | .555 | .537 | 0.822 | 0.830 |

| Trees | 1.526 | 0.760 | 0.055 | 0.050 | .125 | .283 | .545 | 0.724 |

| Building Aesthetics/Design | −0.450 | −1.485 | −0.486 | −0.562 | −.923 | −.863 | 1.984* | 2.054* |

| Sidewalk | 1.864 | 1.278 | −1.433 | −1.496 | −.868 | −.782 | 1.164 | 1.343 |

| Negative Characteristics | ||||||||

| Sidewalk Obstructions/Hazards | −2.214* | −1.505 | 0.059 | 0.138 | 1.576 | 1.456 | −1.322 | −1.487 |

| Wide One-Way Street Designc | −1.254 | −1.472 | −0.327 | −0.420 | −.139 | −.035 | 2.748** | 2.839** |

| Slope | −2.645** | −2.013* | 1.177 | 1.247 | 2.143* | 2.032* | −1.081 | −1.270 |

| Valence and Overall | ||||||||

| Positive | 0.636 | −0.904 | −0.840 | −0.926 | −.996 | −.798 | 2.680** | 2.690** |

| Negative | −2.603** | −1.825 | 0.660 | 0.740 | 1.831 | 1.711 | −0.969 | −1.159 |

| Overall | 2.023* | 0.740 | −0.820 | −0.906 | −1.642 | −1.449 | 2.076* | 2.155* |

| Cul-De-Sacs | ||||||||

| Overalld | 3.543** | 4.007** | 2.714** | 2.741** | −0.228 | −0.185 | − | − |

| Grand Valence and Overall | ||||||||

| Overall Positive | −0.663 | −2.059* | −2.169* | −2.171* | −0.595 | −.465 | 1.727 | 1.838 |

| Overall Negative | −3.640** | −3.165** | 1.442 | 1.494 | −0.146 | −.267 | −0.961 | −1.135 |

| Overall Grand Score | 1.361 | −0.077 | −2.297* | −2.296* | −0.393 | −.246 | 1.806 | 1.898 |

Values are t statistics. Significant results for walkability-adjusted models are bolded.

Neighborhood & Leisure PA measures: children & adolescents (frequency of neighborhood physical activity with Likert scale responses), adults (time spent in leisure MVPA) and older adults (time spent walking for leisure).

analyses adjusted for age, gender, education, race, GIS-defined walkability (high/low), physical functioning (older adults) and clustering of participants within block groups

analyses adjusted for age, gender, education, race, physical functioning (older adults) and clustering of participants within block groups

not included in negative segment or overall scores

not included in grand valence/overall scores

p ≤0.05

p ≤0.01

p ≤0.001

Objectively measured physical activity (MVPA)

There were 27 associations with MVPA out of 172 possible (15.7% of MAPS scores; Table 5). Private recreation, overall destinations and land use and positive streetscape were related to children’s neighborhood and non-school MVPA, and residential mix was related to older adults’ MVPA. Several relations with crossing and segment characteristics were found in children (4 subscales for ‘in neighborhood’ and 3 subscales for ‘non-school’) and older adults (4 subscales). Overall negative scores were related to MVPA in children, and overall positives related in older adults' MVPA in the expected direction. The cul-de-sac score was related to MVPA in adolescents only. The grand score was related in children's ‘in neighborhood’ and older adults' MVPA in the expected direction.

Discussion

The value of using observational measures of streetscape details was demonstrated by many findings that MAPS variables significantly explained physical activity in four age groups while adjusting for macro-level walkability (Table 6). The pattern of results suggests many modifiable built environment attributes are related to physical activity. Destinations and land use, streetscape, and intersection variables were mainly related to walking/biking for transportation. Aesthetic variables were related in the expected direction to leisure time physical activity in children and adults. Overall MAPS scores were related to objectively measured MVPA among children and older adults. In general, the strongest associations were seen with MAPS grand and valence scores, suggesting that behavior is more likely to be influenced by the cumulative impact of numerous environmental attributes needed to collectively create a supportive environment for physical activity.

Table 6.

Summary of significant associations of physical activity outcomes with MAPS summary scores

| Destinations & Land Use |

Streetscape Characteristics |

Aesthetics & Social Characteristics |

Crossings/ Intersections |

Street Segments |

Cul-de-sacs | Grand Scores | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Walking/ biking for transport |

Positive valence | Children Adolescents Adults Older adults |

Children Adolescents Adults |

Older adults | Children Older adults |

Children Adolescents Adults Older adults |

Children Adolescents Adults Older adults |

|

| Negative valence | Children Adolescents Adults Older adults |

Adolescents Adults |

Older adults | Children Adults |

Children Adults |

|||

| Overalla | Children Adults Older adults |

Children Adolescents Adults Older adults |

Adults Older adults |

Children Older adults |

Children Adults Older adults |

Children Adolescents Adults Older adults |

||

| Leisure/ neighborhood physical activity |

Positive valence | Children | Children Adults |

Older adults | Children Adolescents |

Adolescents | ||

| Negative valence | Children | Children Adults |

Adolescents | Children | Children | |||

| Overall Scorea | Adolescents | Children Adults |

Adolescents | Children Older adults |

Adolescents | |||

| Objective physical activity (MVPA) |

Positive valence | Children | Older adults | Older adults | Adolescents | Childrenn’hood | ||

| Negative valence | Childrenn’hood | Childrenn’hood | Childrenn’hood | |||||

| Overalla | Childrenn’hood | Older adults | Childrenn’hood Older adults |

overall score=positive minus negative

= in-neighborhood MVPA

Italics indicates results in unexpected direction

Present findings support the use of multi-level ecological models in physical activity research because other health behavior models do not include built environment influences. Microscale variables have been proposed as potential influences on physical activity, but seldom studied. The ecological model principle of behavioral specificity (Sallis et al., 2008) was strongly supported by present results, with different microscale correlates of active transport versus active leisure. Results of the current study can help build more complete ecological models of physical activity.

Microscale attributes were most consistently associated with walking/biking for transportation. This finding is notable because it indicates that land use and streetscape details are important even after adjusting for macro-level walkability, which itself mainly is related to frequency of active transport (Bauman et al., 2012). The MAPS grand score was significant for all four age groups’ active transport with effect sizes in the small-to-medium range (d=.28 in adults, d=.44 in children and d= .47 in older adults) adjusting for walkability. Overall streetscape and positive destinations/land use were also significant for all age groups. The grand score or the overall positive score consistently had one of the highest t-values in the table, supporting an interpretation that numerous microscale variables, particularly the presence of positive attributes (rather than the lack of negative attributes), contributed to a cumulative impact.

Broad support for the importance of the destinations and land use score confirms the central role of proximity of destinations as a prerequisite for active transportation. However, changing land uses is relatively expensive, and it can be argued whether land use should be considered a microscale feature at all. The street segment score that included design features, slope, and sidewalk quality was significant in all age groups except adolescents. The most consistent associations were seen with "positive building height and setbacks," which is a design element that provides a sense of human-scale buildings and a comforting sense of outdoor enclosure (Ewing et al., 2013). This is an indicator of pedestrian-oriented design in which buildings are a moderate height (3–5 stories) and entrances are directly onto the sidewalk (no setback).

Sidewalk characteristics were related to active transport, though findings varied by age group. Quality of street crossings was only significant among children and older adults, which may be explained by these groups having the most difficulty crossing streets and potentially deriving the most benefit from improved street crossings. Cul-de-sacs were positively related to neighborhood physical activity in children and adolescents, suggesting young people may play there. Both positive and negative summary scores had numerous significant findings, suggesting designers should work to maximize positive attributes and minimize negative attributes for activity-friendly environments.

Regarding specific attributes, some of the strongest associations with active transport were for restaurant and service (e.g. banks) land uses, which tend to be frequent destinations. Shops were significant only for adults and older adults, who are likely to be the most frequent shoppers. Presence of these destinations had the strongest associations among older adults, which is similar to prior findings that self-reported mixed land use was a particularly strong correlate of walking for transport for older adults (Shigematsu et al., 2009). A surprising finding was that overall aesthetics was negatively related to walking for transportation in adults and older adults, though aesthetics was positively related to leisure time physical activity of children and adults. Perhaps graffiti, incivilities, and presence of strangers are more common on busy urban streets, discouraging leisure activity. Street segment variables were mainly related to active transport for children and adults, with factors such as buffers between the street and sidewalk, sidewalk quality, and slope related to this type of physical activity. Notable findings with specific subscales can be followed up with examination of individual items, and identification of important items can lead to actionable recommendations to planners and transportation departments.

The main finding regarding leisure time and neighborhood physical activity was the preponderance of associations in the unexpected direction of variables in all categories, with several significant results for children and adolescents. The implication is that designing places that facilitate walking for transportation appears to be associated with less active play for children in their neighborhoods. Pedestrian amenities are usually concentrated along commercial routes with high vehicular traffic, which parents may perceive as unsuitable for outdoor play. Present findings raise a challenge to urban designers and planners to design neighborhoods that support active transportation and recreation for youth.

The role of type of parking was particularly unclear because having no parking and/or on-street parking was related to neighborhood and leisure physical activity in a positive direction with children and adults, but in a negative direction with older adults. This category of parking was in contrast to having parking structures and large lots. It could be that having no parking and/or street parking was largely found in suburban neighborhoods where children and adults prefer to engage in leisure time/neighborhood physical activity, while older adults may prefer to walk for leisure in places with more destinations, like a large shopping center. The main findings in line with expectations were the positive association of public recreation land use with children's leisure activity and associations of overall aesthetics with leisure physical activity among children and adults.

There were fewer significant associations of MAPS scores with accelerometer-measured MVPA, which is consistent with both conceptual models (Sallis et al., 2006) and reviews (Ding, Sallis, Kerr, Lee, & Rosenberg, 2011) indicating that environmental characteristics are related to specific physical activity domains. The few observed associations of MAPS scores to MVPA could be affected by evidence that microscale attributes were positively related to active transportation but negatively related to active leisure, especially for children. Nevertheless, the grand score was significantly and positively related to MVPA for both children (activity in the neighborhood; 2.2 more minutes/day in the highest vs lowest quintile) and older adults (3.5 more minutes/day in the highest vs lowest quintile) adjusting for walkability. This is further confirmation that the cumulative effects of microscale environment variables are most important, even when few significant effects with components are seen. Among specific variables, availability of private recreation (e.g., commercial gym, dance studio) was related to children's MVPA in the neighborhood and after school. Cul-de-sac presence and amenities were among the few attributes significantly related to MVPA in adolescents. The overall land use score was positively related with children's neighborhood MVPA, despite negative associations with leisure activity. Interestingly, though only the negative crossing and segment scores were significantly related to children's neighborhood MVPA, only the positive crossing and segment scores were related to older adults' MVPA. One interpretation is that negative characteristics discourage parents from allowing their children to play in the neighborhood, but positive characteristics are needed to draw older adults out to be active. It is notable that the strongest associations with objectively measured MVPA were with children's physical activity “in the neighborhood”, indicating the value of ensuring that environmental and physical activity measures are geographically concordant. This pattern supports the specificity principle of ecological models.

Study strengths included the scoring system that simplified a complex measure, examination of multiple physical activity domains, inclusion of three geographic regions, and separate analyses of four age groups in most analyses. Adjusting for macro-level walkability demonstrated that microscale variables provided additional useful information. Study limitations relate to possible selection biases that may be inherent in the research design, as sampling in the study regions was not random, but rather purposeful to maximize variation in walkability and income. Comparisons with census data in the study regions showed the adult sample to have slightly higher income, more educated, and more likely to be White/non-Hispanic, while the older adult and adolescent samples had similar demographics to the census data (King et al., 2011; unpublished). Thus, there are possible limitations to the generalizability of these findings.

Another limitation was that the MAPS method of assessing quarter-mile routes specific to each participant was efficient, but did not thoroughly characterize an entire neighborhood. Also, accelerometer data were not available with the adult sample. Lastly, MAPS remains an expensive measure for data collection, and it is challenging to score, so it would be valuable to develop a shorter and simpler version, with automatic scoring software.

Conclusion

The present results provided strong evidence that microscale environment attributes were related to physical activity patterns across the life course, and these associations were independent of macro-level walkability. The implication is that it may be feasible to facilitate physical activity by altering microscale characteristics like street crossings, sidewalks, and aesthetics. Rather than identifying a few critical environmental characteristics that have particularly powerful associations with physical activity, it appears the cumulative effects of numerous attributes are the likely mechanism of effect. Both positive and negative aspects of the environment appeared to be important. The grand score that summarized all the sections was often the strongest correlate of all the physical activity outcomes. The present study provided strong evidence of the predictive validity of the MAPS instrument by demonstrating many associations with physical activity that generalized across age groups and added information beyond macro-level walkability. Present findings supported the value of applying ecological models to physical activity research and were consistent with the principle of behavior-specific correlates of environmental attributes. Using instruments like MAPS can help identify built environment changes that can be achieved at a reasonable cost and in a feasible time frame with a likelihood of improving physical activity. Present results support an interpretation that microscale attributes of streetscapes can affect the experience of being active in the environment and thus the likelihood of meeting physical activity guidelines associated with reduced chronic disease and improved health status.

Research Highlights.

Microscale attributes were related to physical activity in all ages.

Microscale attributes were most strongly associated with active transport.

There are different microscale correlates of active transport vs active leisure.

There is a cumulative effect of environmental attributes.

The predictive validity of the MAPS audit tool and scoring system is established.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Bauman AE, Reis RS, Sallis JF, Wells JC, Loos RJ, Martin BW for the Lancet Physical Activity Series Working Group. Correlates of physical activity: why are some people physically active and others not? The Lancet. 2012;380(9838):258–271. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60735-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boarnet MG, Forsyth A, Day K, Oakes JM. The street level built environment and physical activity and walking: Results of a predictive validity study for the Irvine-Minnesota Inventory. Environment and Behavior. 2011;43:735–775. [Google Scholar]

- Brownson RC, Hoehner CM, Day K, Forsyth A, Sallis JF. Measuring the built environment for physical activity: state of the science. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2009;36(Suppl 4):S99–123. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2009.01.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bull FC, Maslin TS, Armstrong T. Global physical activity questionnaire (GPAQ): nine country reliability and validity study. Journal of physical activity & health. 2009;6(6):790. doi: 10.1123/jpah.6.6.790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brownson RC, Chang JJ, Eyler AA, Ainsworth BE, Kirtland KA, Saelens BE, Sallis JF. Measuring the environment for friendliness toward physical activity: a comparison of the reliability of 3 questionnaires. Journal Information. 2004;94(3) doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.3.473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cain KL, Millstein RA, Geremia CM. Microscale Audit of Pedestrian Streetscapes (MAPS): Data Collection & Scoring Manual. University California San Diego; 2012. [Accessed Aug 8, 2013]. Available for download at: http://sallis.ucsd.edu/Documents/Measures_documents/MAPS%20Manual_v1_010713.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Cain KL, Sallis JF, Conway TL, Van Dyck D, Calhoon L. Using Accelerometers in Youth Physical Activity Studies: A Review of Methods. Journal of Physical Activity and Health. 2013;2013;10:437–450. doi: 10.1123/jpah.10.3.437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cerin E, Chan K, Macfarlane DJ, Lee K, Lai P. Objective assessment of walking environments in ultra-dense cities: Development and reliability of the Environment in Asia Scan Tool—Hong Kong version (EAST-HK) Health and Place. 2011;17(4):937–945. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2011.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding D, Sallis JF, Kerr J, Lee S, Rosenberg DE. Neighborhood environment and physical activity among youth: A review. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2011;41:442–455. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2011.06.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ewing R, Clemente O, Neckerman KM, Purciel-Hill M, Quinn JW, Rundle A. Measuring urban design: Metrics for liveable places. Washington, DC: Island Press; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Frank LD, Saelens BE, Chapman J, Sallis JF, Kerr J, Glanz K, Couch SC, Learnihan V, Zhou C, Colburn T, Cain KL. Objective assessment of obesogenic environments in youth: Geographic information system methods and spatial findings from the Neighborhood Impact on Kids (NIK) Study. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2012;42(5):e47–55. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2012.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frank LD, Sallis JF, Saelens BE, Leary L, Cain K, Conway TL, Hess PM. The development of a walkability index: application to the Neighborhood Quality of Life Study. British Journal of Sports Medicine. 2010;44:924–933. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.2009.058701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freedson PS, Melanson E, Sirard J. Calibration of the Computer Science and Applications, Inc. accelerometer. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise. 1998;30:777–781. doi: 10.1097/00005768-199805000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grow M, Saelens BE, Kerr J, Durant N, Norman GJ, Sallis JF. Factors associated with children’s active use of recreation sites in their communities: examining accessibility and built environment. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise. 2008;40(12):2071–2079. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e3181817baa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoehner CM, Brennan Ramirez LK, Elliott MB, Handy SL, Brownson RC. Perceived and objective environmental measures and physical activity among urban adults. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2005;28(2 Suppl 2):105–116. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2004.10.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kealey M, Kruger J, Hunter R, Ivey S, Satariano W, Bayles C, Williams K. In Proceedings of the 19th National Conference on Chronic Disease Prevention and Control. Atlanta, GA: 2005. Engaging Older Adults to Be More Active Where They Live: Audit Tool Development. [Google Scholar]

- King AC, Sallis JF, Frank LD, Saelens BE, Cain K, Conway TL, Chapman JE, Ahn DK, Kerr J. Aging in neighborhoods differing in walkability and income: associations with physical activity and obesity in older adults. Social Science and Medicine. 2011;73:1525–1533. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.08.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kneeshaw-Price S, Saelens BE, Sallis JF, Glanz K, Frank LD, Kerr J, Hannon P, Grembowski DE, Chan KCG, Cain KL. Objective Physical Activity by Location: Why the Neighborhood Matters. Pediatric Exercise Science. 2013;25:468–486. doi: 10.1123/pes.25.3.468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Millstein RA, Cain KL, Sallis JF, Conway TL, Geremia C, Frank LD, Chapman J, Van Dyck D, Dipzinski L, Kerr J, Glanz K, Saelens BE. Development, scoring, and reliability of the Microscale Audit of Pedestrian Streetscapes (MAPS) BMC Public Health. 2013;13:403. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-13-403. http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2458/13/403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moudon AV, Lee C. Walking and bicycling: an evaluation of environmental audit instruments. American Journal of Health Promotion. 2003;18(1):21–37. doi: 10.4278/0890-1171-18.1.21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pikora TJ, Bull FCL, Jamrozik K, Knuiman M, Giles-Corti B, Donovan RJ. Developing a reliable audit instrument to measure the physical environment for physical activity. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2002;23(3):187–94. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(02)00498-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pikora TJ, Giles-Corti B, Knuiman MW, Bull FC, Jamrozik K, Donovan RJ. Neighborhood environmental factors correlated with walking near home: Using SPACES. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise. 2006;38:708–714. doi: 10.1249/01.mss.0000210189.64458.f3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saelens BE, Sallis JF, Frank LD, Couch SC, Zhou C, Colburn T, Cain KL, Chapman J, Glanz K. Obesogenic neighborhood environments, child and parent obesity: The Neighborhood Impact on Kids (NIK) Study. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2012;42(5):e57–e64. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2012.02.008. Epub on April 10, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sallis JF, Cervero RB, Ascher W, Henderson KA, Kraft MK, Kerr J. An ecological approach to creating more physically active communities. Annual Review of Public Health. 2006;27:297–322. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.27.021405.102100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sallis JF, Conway TL, Kerr J, Saelens BE, Frank LD, Glanz K, Slymen DJ, Cain KL, Chapman JE. Presentation at International Society Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity conference. Melbourne, Australia: 2011a. Adolescents’ Physical Activity as Related to Built Environments: TEAN Study in the US. [Google Scholar]

- Sallis JF, Owen N, Fisher EB. Ecological models of health behavior. In: Glanz K, Rimer BK, Viswanath K, editors. Health Behavior and Health Education: Theory, Research, and Practice. 4th edition. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 2008. pp. 465–486. [Google Scholar]

- Sallis JF, Slymen DJ, Conway TL, Frank LD, Saelens BE, Cain K, Chapman JE. Income disparities in perceived neighborhood built and social environment attributes. Health and Place. 2011b;17:1274–1283. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2011.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sayers SP, Jette AM, Haley SM, Heeren TC, Guralnik JM, Fielding RA. Validation of the Late-Life Function and Disability Instrument. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2004;52(9):1554–1559. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2004.52422.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shigematsu R, Sallis JF, Conway TL, Saelens BE, Frank LD, Cain K, Chapman JE, King AC. Age differences in the relation of perceived neighborhood environment to walking. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise. 2009;41:314–321. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e318185496c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart AL, Mills KM, King AC, Haskell WL, Gillis D, Ritter PL. CHAMPS physical activity questionnaire for older adults: outcomes for interventions. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise. 2001;33(7):1126–1141. doi: 10.1097/00005768-200107000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trost SG, Pate RR, Sallis JF, Freedson PS, Taylor WC, Dowda M, Sirard J. Age and gender differences in objectively measured physical activity in youth. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise. 2002;34:350–355. doi: 10.1097/00005768-200202000-00025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]