The current study retrospectively examined the association of diabetes mellitus (DM) and colon cancer prognosis in a population-based cohort in Taiwan. Data from the National Cancer Registry and the National Health Insurance system databases in Taiwan were reviewed to establish a patient cohort representative of the general population. Among patients who receive curative surgery for early colon cancer, DM was determined to be a predictor of increased overall mortality.

Keywords: Cancer registry, Diabetes mellitus, Colorectal cancer, Prognosis

Abstract

Background.

We investigated the association between diabetes mellitus (DM) and the prognosis of patients with early colon cancer who had undergone curative surgery.

Methods.

From three national databases of patients in Taiwan, we selected a cohort of colon cancer patients who had been newly diagnosed with stage I or stage II colon cancer between January 1, 2004 and December 31, 2008 and had undergone curative surgery. We collected information regarding DM (type 2 DM only), the use of antidiabetic medications, other comorbidities, and survival outcomes. The colon cancer-specific survival (CSS) and the overall survival (OS) were compared between patients with and without DM.

Results.

We selected 6,937 colon cancer patients, among whom 1,371 (19.8%) had DM. The colon cancer patients with DM were older and less likely to receive adjuvant chemotherapy but had a similar tumor stage and grade, compared with colon cancer patients without DM. Compared with colon cancer patients without DM, patients with DM had significantly shorter OS (5-year OS: 71.0% vs. 81.7%) and CSS (5-year CSS: 86.7% vs. 89.2%). After adjusting for age, sex, stage, adjuvant chemotherapy, and comorbidities in our multivariate analysis, DM remained an independent prognostic factor for overall mortality (adjusted hazards ratio: 1.32, 95% confidence interval: 1.18–1.49), but not for cancer-specific mortality. Among the colon cancer patients who had received antidiabetic drug therapy, patients who had used insulin had significantly shorter CSS and OS than patients who had not.

Conclusion.

Among patients who receive curative surgery for early colon cancer, DM is a predictor of increased overall mortality.

Implications for Practice:

The current study demonstrated that diabetes mellitus (DM) is an independent predictor of increased overall mortality in patients with early colon cancer. Additionally, DM may be associated with increased cancer-specific mortality in younger patients (age <65 years). In DM patients who received anti-diabetic drugs, insulin treatment significantly predicted for overall mortality and colon cancer-specific mortality. Our study suggested colon cancer patients with long-standing DM or poor DM status have increased colon cancer-specific mortality. By knowing this information, physicians may pay more attention to DM diagnosis and DM care in early colon cancer patients.

Introduction

Colon cancer is one of the most commonly diagnosed cancers and remains the leading cause of cancer-related deaths worldwide, despite advances in systemic cytotoxic and targeted therapies [1]. For localized disease, a complete resection can be curative and is the current treatment standard. However, approximately 20%–25% of patients with stage II disease suffer from disease recurrence after surgery [2, 3].

Several studies and meta-analyses have shown that diabetes mellitus (DM) is associated with an increased risk of colon cancer [4–8]. The chronic use of insulin or sulfonylureas in patients with type 2 DM may also increase the risk of colon cancer [9, 10]. One potential explanation for these findings is secondary hyperinsulinemia caused by insulin resistance, which may promote colon cancer carcinogenesis [11].

Because DM may contribute to increased colon cancer carcinogenesis, it is possible that DM is associated with poor prognosis in colon cancer. However, the results of previous studies of DM and colon cancer prognosis conflict. Some studies have shown that colon cancer patients with DM had poorer survival than those without DM [12–14]. However, other studies did not identify a similar association [15, 16]. These inconsistent findings may be attributed to heterogeneous populations, different definitions of DM history (from questionnaires or medical records), and the adjusted covariates in the prognostic analyses.

In our current study, we retrospectively examined the association of DM and colon cancer prognosis in a population-based cohort in Taiwan. We reviewed data from the National Cancer Registry and the National Health Insurance (NHI) system databases in Taiwan to establish a patient cohort representative of the general population. Because it has been reported that DM may have different prognostic impact on colon and rectal cancers and considering the expectation that DM will not significantly affect the mortality rate for stage III or IV colon cancer patients because of relatively shorter 5-year survival rates, we included only early colon cancer patients in our study [14].

Materials and Methods

Data Sources

A population-based cohort of patients who had been newly diagnosed with colon cancer between January 1, 2004 and December 31, 2008 was selected from the Taiwan Cancer Registry database [17], which is managed by the Bureau of Health Promotion, Department of Health, Taiwan. The database contains records regarding approximately 78% of the newly diagnosed cancer patients in Taiwan, and all of the major cancer care institutes in Taiwan are required to enter medical data for their patients into the database [18]. Patients’ baseline data regarding demographic characteristics, cancer staging, cancer grading, and anticancer treatments were collected from the database.

The NHI is a mandatory health insurance system that provides insurance coverage for more than 98% of the residents of Taiwan [19]. We used its reimbursement database to collect information regarding DM status, antidiabetic treatments, and other comorbidities for our study cohort. Only information regarding type 2 DM was collected. All medical claims were submitted and captured electronically. The medical records were linked to the mortality data of the National Death Registry. We used individual patients’ identification numbers and birthdays to link three databases. In Taiwan, every resident has a unique identification number, so we could handle cases with the same birthday and gender well.

Personal identities were encrypted, and therefore, all the data were analyzed anonymously to conform to the privacy regulations for personal electronic data. The release of our study data was approved by Collaboration Center of Health Information Application, Department of Health Executive Yuan. Our study protocol was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the College of Public Health of National Taiwan University.

Study Participants

Patients who had been newly diagnosed with colon cancer between January 1, 2004 and December 31, 2008 based on the criteria of the International Classification of Diseases for Oncology, Third Edition (ICD-O-3), codes C180 through C189 and C199, were older than 40 years on the date of diagnosis, had received surgical resection as the first curative treatment, and had been evaluated as pathologic stage I or II according to criteria established by the American Joint Committee on Cancer, Sixth Revision [20], were included in our study cohort. Patients were excluded for the following conditions to increase the specificity of those with early stage colon cancer who had received curative surgery: (a) an unknown DM status, which may be related to unknown diagnosis time of colon cancer or termination of insurance; (b) histological findings indicating lymphoma (ICD-O-M9590 through M9989) or Kaposi’s sarcoma (M9140); (c) a diagnosis of any cancer before 2004 or cancer other than colon cancer between January 1, 2004 and December 31, 2008; (d) type 1 DM; (e) unclear surgical margins; (f) patients who did not fulfill DM diagnosis criteria but received antidiabetic drugs; and (g) patients who received neoadjuvant radiotherapy or chemotherapy, combined radiotherapy and surgery, or combined chemotherapy after 90 days of surgery as their initial treatment for colon cancer.

Study Variables and Endpoints

The study participants were classified as patients with DM or without DM (non-DM) according to their medical claims records in the NHI database for 1 year preceding the date of their colon cancer diagnosis. The diagnosis codes from both inpatient and outpatient clinics were used. Patients were defined as having DM (ICD-9-CM: 250.×) if a DM diagnosis was noted at least twice during their outpatient clinic visits or at least once during hospitalization during the year prior to their colon cancer diagnosis. Patients who had been treated with insulin were defined as those with any record of use within 1 year prior to the date of their colon cancer diagnosis, according to their NHI claims records.

In addition to DM, all other comorbidities in the Deyo version of the Charlson Comorbidity Index were examined [21]. The International Classification of Disease, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) codes derived from the NHI claims data were screened for comorbidities by using the revised mapping algorithm by Quan et al. [22]. All comorbidities were coded and analyzed as dichotomized variables (yes or no). The colon cancer patients’ records were screened for the following ICD-9-CM diagnosis codes: DM (250.×); congestive heart failure (398.91, 402.01, 402.11, 402.91, 404.01, 404.03, 404.11, 404.13, 404.91, 404.93, 425.4–425.9, 428.×); cerebrovascular disease (362.34 and 430.×–438.×); dementia (290.×, 294.1, and 331.2); chronic pulmonary disease (416.8, 416.9, 490.×–505.×, 506.4, 508.1, and 508.8); renal disease (403.01, 403.11, 403.91, 404.02, 404.03, 404.12, 404.13, 404.92, 404.93, 582.×, 583.0–583.7, 585.×, 586.×, 588.0, V42.0, V45.1, and V56.×); and cirrhosis (571.2, 571.5, and 571.6).

Patients were followed from the day of colon cancer diagnosis until death or December 31, 2011s. We defined the period from the date of colon cancer diagnosis until death as overall survival (OS) for deaths from all causes or as colon cancer-specific survival (CSS) for deaths related to colon cancer. The data of patients surviving past the last day of the follow-up period were censored.

Statistical Methods

We compared the mean or frequency of the demographic and clinical characteristics of the DM and non-DM study groups on the date of colon cancer diagnosis by using an independent t test for the continuous variables or the χ2 test for the categorical variables. Patient survival by DM status was estimated using the Kaplan-Meier method and was compared using the log-rank test. We used a Cox proportional-hazards model to estimate the adjusted hazards ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for the association of DM and other risk factors on survival outcomes with an adjustment for demographic variables, tumor stage, tumor grade, type of DM treatment, and comorbidities. To evaluate the consistency of the prognostic associations of DM across different patient populations, subgroup analyses defined by age (40–64 or ≥65 years), sex, tumor stage, type of treatment for colon cancer, and DM medication were performed as sensitivity analyses. The results of comparisons with a two-sided p value less than .05 were considered statistically significant. SAS, version 9.2, statistical software (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC, http://www.sas.com) was used for all the statistical analyses.

Results

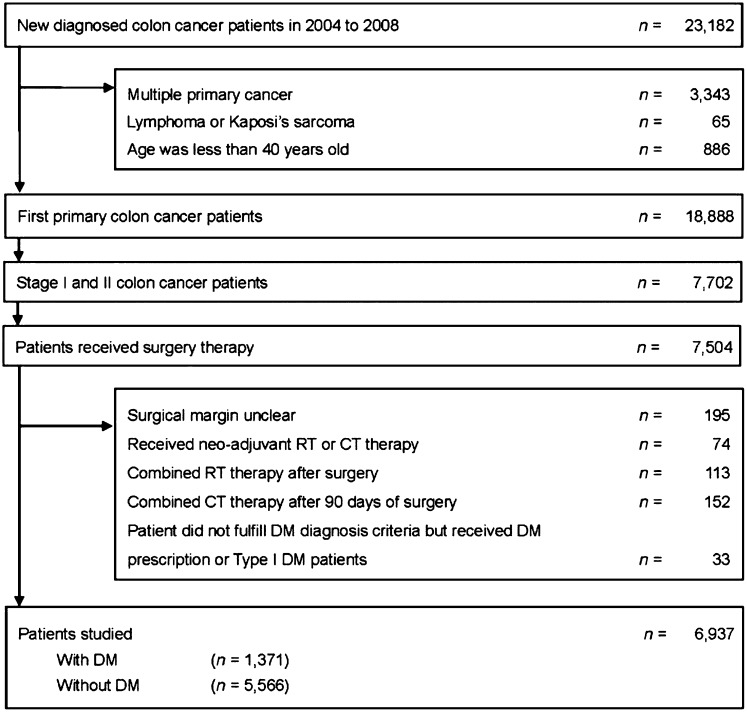

We identified 23,182 patients who had been newly diagnosed with early colon cancer between January 1, 2004 and December 31st, 2008 in the Taiwan Cancer Registry database. Among the 6,937 early colon cancer patients who met the inclusion criteria for our study (Fig. 1), 1,371 (19.8%) of them had DM. There were only 33 patients who did not fulfill DM diagnosis criteria but received antidiabetic drugs. The baseline patient characteristics are summarized in Table 1. The colon cancer patients with DM were older (mean age, 70.2 years vs. 66.6 years, p < .001) and less likely to have received adjuvant chemotherapy (26.6% vs. 31.8%, p < .001) than those without DM. Compared with colon cancer patients without DM, those with DM were more likely to have had comorbidities, such as liver cirrhosis (2.7% vs. 1.0%, p < .001), congestive heart failure (9.0% vs. 4.9%, p < .001), cerebrovascular disease (15.8% vs. 7.9%, p < .001), dementia (3.4% vs. 1.7%, p < .001), hemiplegia or paraplegia (1.5% vs. 0.7%, p = .003), or renal disease (9.4% vs. 3.2%, p < .001).

Figure 1.

Patient flow diagram.

Abbreviations: CT, chemotherapy; DM, diabetes mellitus; RT, radiotherapy.

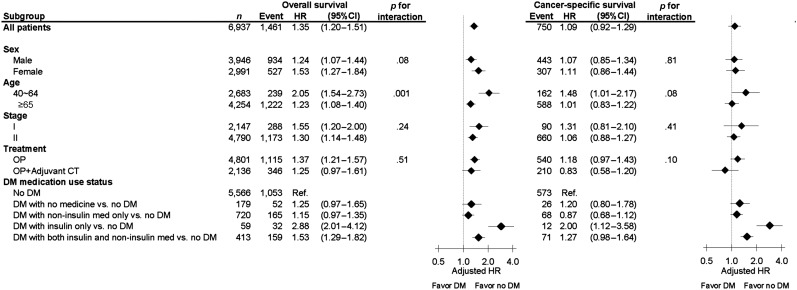

Table 1.

Patient characteristics (n = 6,937)

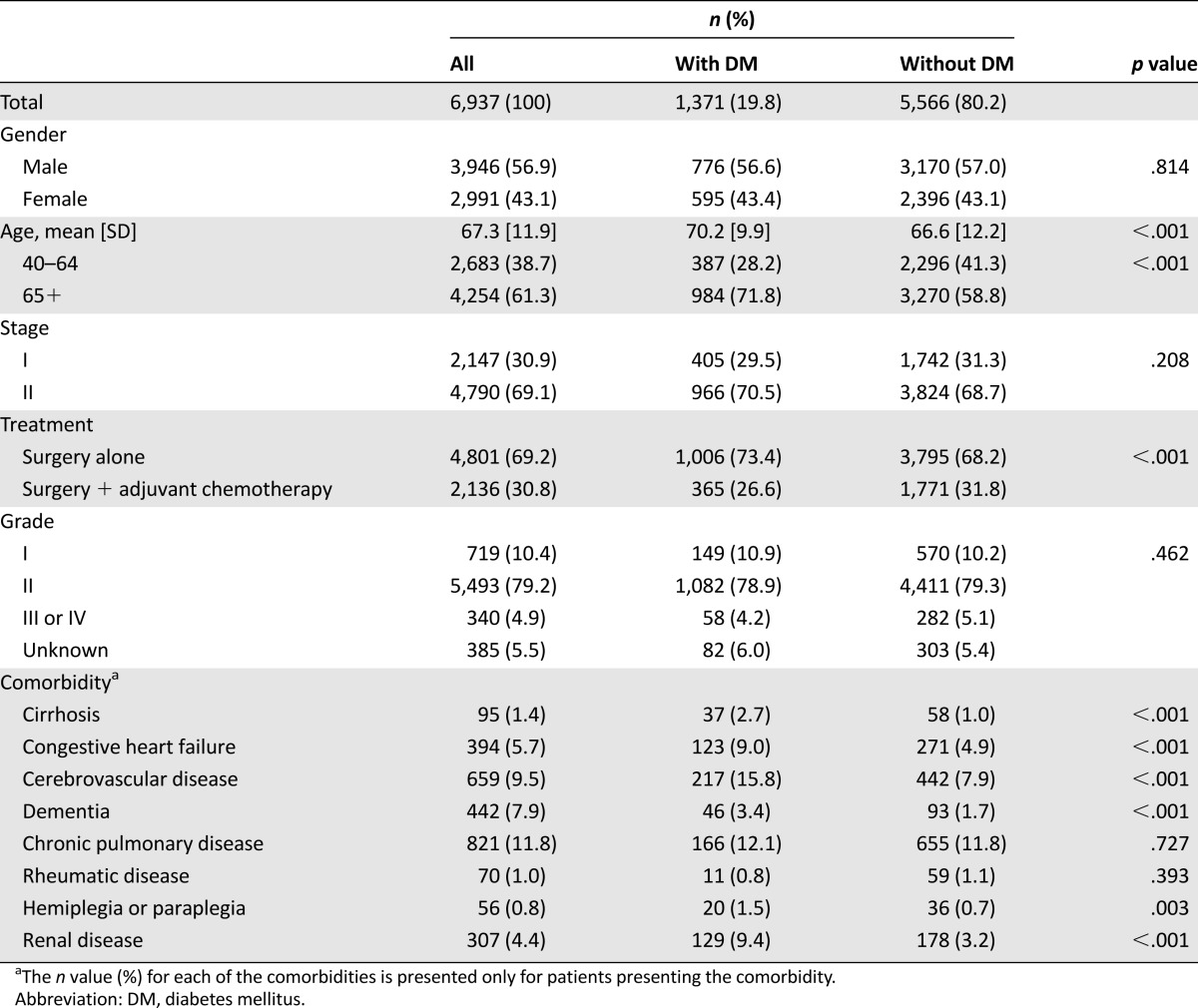

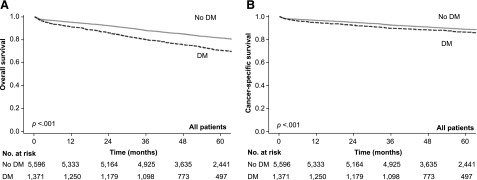

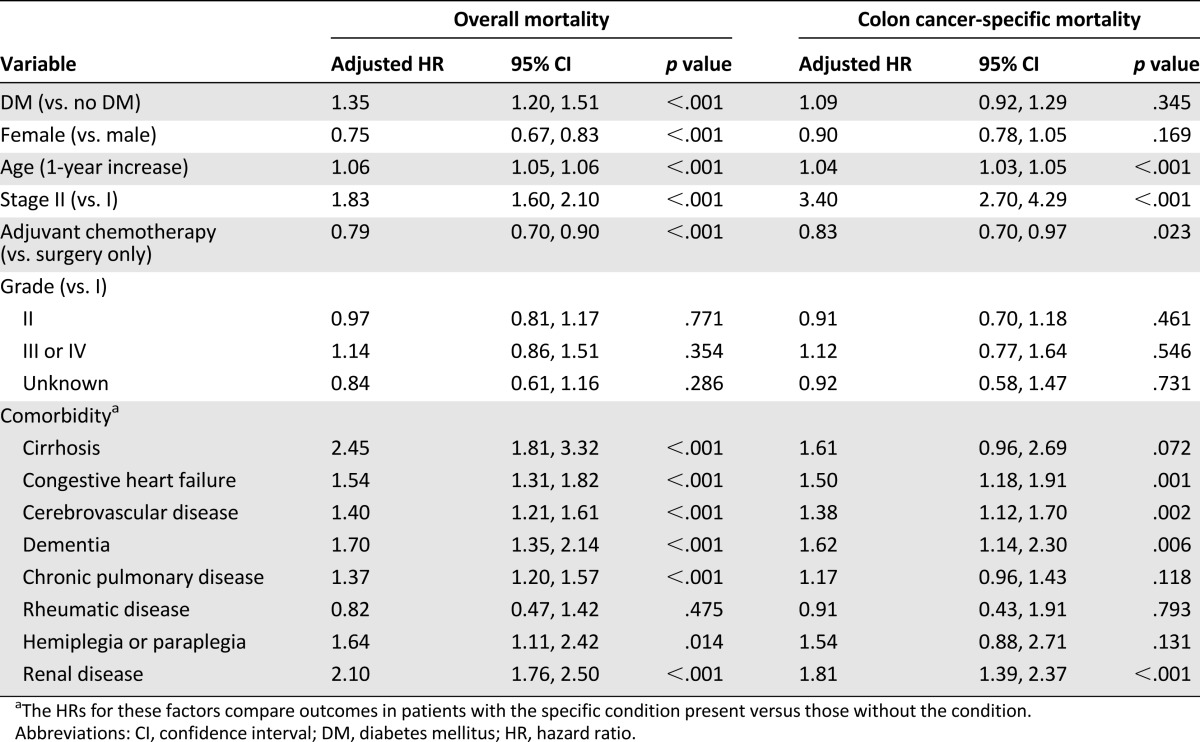

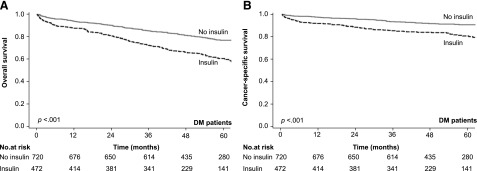

The median follow-up period of all patients was 54.9 months, and 1,461 (21.1%) colon cancer patients had died. The colon cancer patients with DM had shorter OS (2-year OS: 86.0% vs. 92.3%, 5-year OS: 71.0% vs. 81.7%, p < .001; Fig. 2A) and shorter CSS (2-year CSS: 92.6% vs. 95.1%, 5-year CSS: 86.7% vs. 89.2%, p < .001; Fig. 2B). After adjusting for age, sex, stage, adjuvant chemotherapy, and comorbidities in the multivariable analysis, DM remained an independent predictor of increased overall mortality (adjusted HR: 1.35; 95% CI: 1.20–1.51, p < .001), but it was not a significant predictor of increased colon cancer-specific mortality (adjusted HR: 1.09; 95% CI: 0.92–1.29, p = .345; Table 2). In the subgroup analysis of OS, the prognostic association of DM existed across all subgroups, with no significant differences. In the analysis of CSS, the prognostic association of DM was significant in younger colon cancer patients (age, 40–64 years) only (Fig. 3). In the analysis of the impact of DM medication use status (versus no DM) on survival, DM with insulin treatment (insulin only or both insulin and noninsulin medication) also had significant association with poor OS and CSS (Fig. 3).

Figure 2.

Kaplan-Meier analysis of survival in patients who received surgery. (A, B): Kaplan-Meier analysis of overall survival (A) and colon cancer-specific survival (B) of patients with stage I or II colon cancer who received surgery. Patients were grouped by diabetes mellitus status. The p values were determined by the log-rank test.

Abbreviation: DM, diabetes mellitus.

Table 2.

Multivariate analysis by the Cox proportional hazard model to demonstrate the adjusted hazard ratios of potential factors on overall survival and colon cancer-specific survival

Figure 3.

Subgroup analysis of adjusted hazard ratios of mortality for DM vs. no-DM using the Cox proportional hazard model (the no-DM group as the reference). Every analysis was adjusted for all the other factors not involving the subgroup, including gender, age, tumor stage, treatment (surgery vs. surgery + adjuvant chemotherapy), cirrhosis, and all other comorbidities listed in Table 1.

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; CT, chemotherapy; DM, diabetes mellitus; Favor no DM, hazard ratios favoring patients without DM to have better survival outcomes; HR, hazard ratio; OP, surgery.

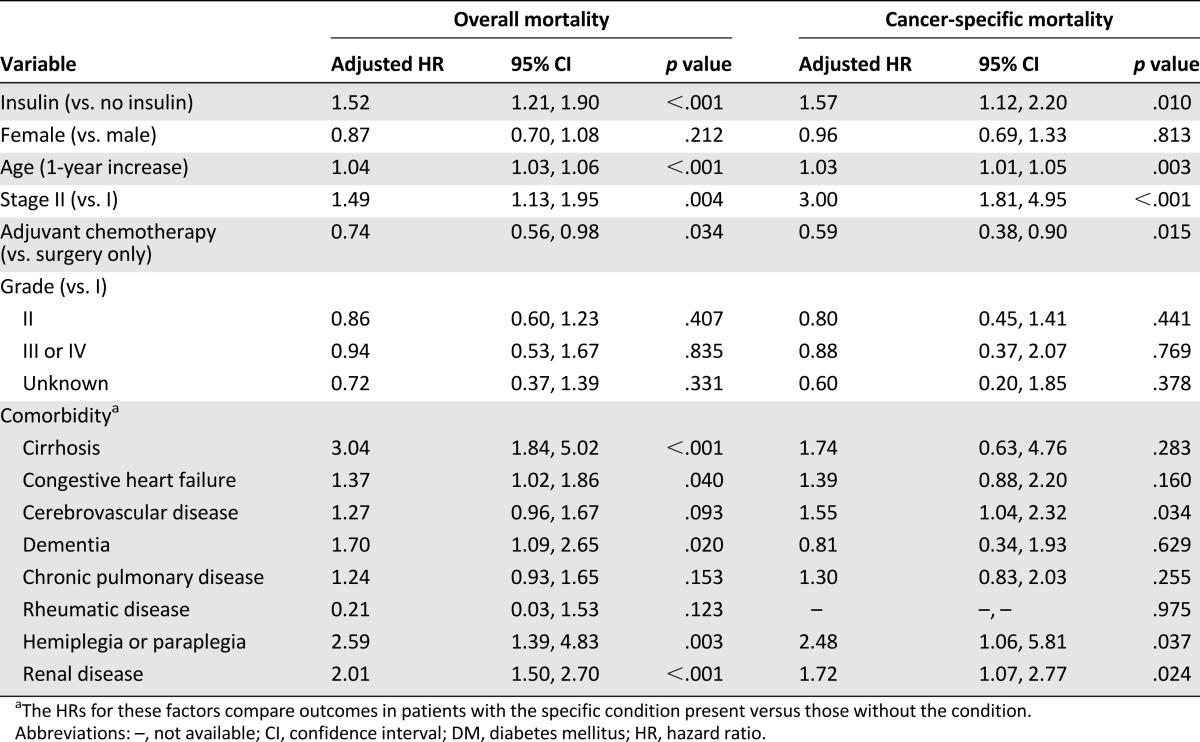

Among the 1,371 colon cancer patients with DM, 1,192 (86.9%) had received antidiabetic medication treatment within 1 year prior to the date of their colon cancer diagnosis. Among them, 472 patients had used insulin, 1,133 patients had used noninsulin drugs, 822 patients had used metformin, and 914 patients had used sulfonylureas. The colon cancer patients with DM who had used insulin had shorter OS (p < .001; Fig. 4A) and shorter CSS (p < .001; Fig. 4B) than those who had used an antidiabetic medication other than insulin. In the multivariate analysis, insulin treatment remained an independent predictor for overall mortality (adjusted HR: 1.52; 95% CI: 1.21–1.90, p < .001) and colon cancer-specific mortality (adjusted HR: 1.57; 95% CI: 1.12–2.20, p = .010; Table 3).

Figure 4.

Kaplan-Meier analysis of survival in patients with DM. (A, B): Kaplan-Meier analysis of overall survival (A) colon cancer-specific survival (B) of patients with DM, grouped by the usage of insulin or not. The p values were conducted by the log-rank test.

Abbreviation: DM, diabetes mellitus.

Table 3.

The Cox regression model among DM patients excluding no receiving DM drugs (n = 1,192)

Discussion

In this study, we found that the incidence of DM in our study population (mean age, 67.3 years) was 19.8%, which was comparable to general population of similar age in Taiwan (60–70 years, 20.1%) [23]. We also found colon cancer patients with DM had shorter OS than those without DM. In our multivariate analyses, DM remained an independent prognostic factor for increased overall mortality. Its prognostic influence was consistent across all the colon cancer patient subgroups. Our findings are in agreement with previous studies [12–14, 24, 25], whereas two relatively small studies [15, 16] had previously shown the opposite of our results.

In contrast, we found that DM was not an independent predictive factor for increased colon cancer-specific mortality, which is in agreement with two previous large population-based studies [14, 25]. In a nationwide population-based study in the Netherlands, DM was not associated with shorter CSS in patients with stage I to stage III colon cancer but was a predictor of shorter cancer-specific survival in patients with rectal cancer [14]. It is possible that DM has different prognostic association on colon and rectal cancer. In a large prospective cohort, however, Dehal et al. [24] showed that DM was nonsignificantly associated with higher cancer-specific mortality (relative risk, 1.29; 95% CI, 0.98 to 1.70) in patients with nonmetastatic “colorectal” cancer. Furthermore, a single-institute study showed that DM was significantly associated with shorter CSS in patients with resected stage I to stage III colon cancer when no adjustments for adjuvant chemotherapy and comorbidities were made in the multivariate analysis [12].

Although DM was not an independent predictor of increased colon cancer-specific mortality in our entire study population, it tended to be more prevalent in younger patients (age, 40–64 years) with shorter CSS (Fig. 3). One possible explanation for this finding is that younger patients were more likely to die of colon cancer than from causes that were unrelated to cancer (cancer death, age 40–64 years: 67.7%; age ≥65 years: 48.1%). In addition, both the CSS and the OS were generally longer for younger colon cancer patients. Thus, the associations of DM on the OS and the CSS for colon cancer patients may increase over time. Further studies are needed to clarify the basis of the association between DM and CSS in younger colon cancer patients, and separate analyses of colon and rectal cancer patients are also warranted.

Several hypotheses have been proposed that may explain the mechanisms underlying the association between DM and poor prognosis in colon cancer patients [26]. First, DM indirectly impacts prognosis through the shared risk factors of type 2 DM and colon cancer, such as the association between obesity and increased deaths from all causes among colorectal cancer patients [27]. Second, DM may directly influence the pathophysiology of colon cancer as a result of secondary hyperinsulinemia, which may promote carcinogenesis in colon cancer through the stimulation of insulin and insulin-like growth factor-1 receptors [11].

We also found that colon cancer patients with DM who had used insulin had shorter OS and CSS than those who had not used insulin, and insulin treatment was an independent predictor for both overall and colon cancer mortality in our multivariate analysis. The data should be interpreted with caution because we could not prevent the bias of antidiabetic drug overlaps, duration of antidiabetic drugs, and compliance. The treatment of DM usually changed with time as the disease progressed, from oral drugs to insulin injection, so the association of insulin treatment with increased colon cancer mortality may be related to long-standing and/or worse diabetes status, which is consistent with the explanation of secondary hyperinsulinemia.

Whether insulin use is an independent predictor of cancer mortality is still unclear. Our study result is in line with a registry-based study in Finland that revealed insulin-treated patients with diabetes had higher mortality from malignancy than non-insulin-treated patients [28]. On the other hand, one prospective study showed opposite results, which was that insulin use was associated with significantly lower colorectal cancer mortality in patients with colorectal cancer and type 2 DM [24]. The authors suggested the association could be related to the small number of patients.

Several limitations to our findings should be noted. First, our database did not include information regarding postdiagnosed obesity and patient’s physical activity, and we may overestimate the prognosis impact of DM in colon cancer, because obesity and physical activity are risk factors for DM [27, 29]. Second, information regarding the dosage and treatment period of antidiabetic drug therapies was difficult to clarify. Third, we could not assess cancer recurrence based on the information in the database. However, the large sample size of our population-based study likely provided a more accurate representation of daily clinical practice.

Conclusion

We found that DM is an independent prognostic factor for increased overall mortality in patients with early colon cancer. Among colon cancer patients with DM who receive antidiabetic drug therapy, patients who use insulin have shorter OS and CSS than patients who do not.

Acknowledgment

This study was supported by a grant from the Science and Technology Unit, Department of Health in Taiwan (DOH101-TD-B-111-001 and DOH102-TD-B-111-001).

Footnotes

For Further Reading:Ming Yin, Jie Zhou, Edward J. Gorak, Fahd Quddus. Metformin Is Associated With Survival Benefit in Cancer Patients With Concurrent Type 2 Diabetes: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. The Oncologist 2013;18:1248–1255.

Implications for Practice:Patients with type 2 diabetes have increased cancer risk and cancer-related mortality, which can be reduced by metformin treatment. However, it is unclear whether metformin can also modulate clinical outcomes in patients with cancer and concurrent type 2 diabetes. Our meta-analysis provided evidence that there was a relative survival benefit associated with metformin treatment compared with treatment with other glucose-lowering medications. Our results suggest that metformin is the drug of choice in the treatment of patients with cancer and concurrent type 2 diabetes.

Author Contributions

Conception/Design: Kuo-Hsing Chen, Yu-Yun Shao, Zhong-Zhe Lin

Provision of study material or patients: Yi-Chun Yeh

Collection and/or assembly of data: Yi-Chun Yeh

Data analysis and interpretation: Kuo-Hsing Chen, Yu-Yun Shao, Ho-Min Chen

Manuscript writing: Kuo-Hsing Chen

Final approval of manuscript: Kuo-Hsing Chen, Yu-Yun Shao, Zhong-Zhe Lin, Yi-Chun Yeh, Wen-Yi Shau, Raymond Nienchen Kuo, Ho-Min Chen, Chiu-Ling Lai, Kun-Huei Yeh, Ann-Lii Cheng, Mei-Shu Lai

Disclosures

The authors indicated no financial relationships.

References

- 1.Jemal A, Bray F, Center MM, et al. Global cancer statistics. CA Cancer J Clin. 2011;61:69–90. doi: 10.3322/caac.20107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gray R, Barnwell J, McConkey C, et al. Adjuvant chemotherapy versus observation in patients with colorectal cancer: A randomised study. Lancet. 2007;370:2020–2029. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61866-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lin BR, Lai HS, Chang TC, et al. Long-term survival results of surgery alone versus surgery plus UFT (Uracil and Tegafur)-based adjuvant therapy in patients with stage II colon cancer. J Gastrointest Surg. 2011;15:2239–2245. doi: 10.1007/s11605-011-1722-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Larsson SC, Orsini N, Wolk A. Diabetes mellitus and risk of colorectal cancer: A meta-analysis. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2005;97:1679–1687. doi: 10.1093/jnci/dji375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yuhara H., et al. Is diabetes mellitus an independent risk factor for colon cancer and rectal cancer? Am J Gastroenterol. 2011;106:1911–1922. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2011.301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jiang Y, Ben Q, Shen H, et al. Diabetes mellitus and incidence and mortality of colorectal cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies. Eur J Epidemiol. 2011;26:863–876. doi: 10.1007/s10654-011-9617-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.He J, Stram DO, Kolonel LN, et al. The association of diabetes with colorectal cancer risk: The Multiethnic Cohort. Br J Cancer. 2010;103:120–126. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6605721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tseng CH. Diabetes, metformin use, and colon cancer: A population-based cohort study in Taiwan. Eur J Endocrinol. 2012;167:409–416. doi: 10.1530/EJE-12-0369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chang CH, Lin JW, Wu LC, et al. Oral insulin secretagogues, insulin, and cancer risk in type 2 diabetes mellitus. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012;97:E1170–E1175. doi: 10.1210/jc.2012-1162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yang YX, Hennessy S, Lewis JD. Insulin therapy and colorectal cancer risk among type 2 diabetes mellitus patients. Gastroenterology. 2004;127:1044–1050. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Giovannucci E. Insulin and colon cancer. Cancer Causes Control. 1995;6:164–179. doi: 10.1007/BF00052777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Huang YC, Lin JK, Chen WS, et al. Diabetes mellitus negatively impacts survival of patients with colon cancer, particularly in stage II disease. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2011;137:211–220. doi: 10.1007/s00432-010-0879-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Meyerhardt JA, Catalano PJ, Haller DG, et al. Impact of diabetes mellitus on outcomes in patients with colon cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:433–440. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.07.125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.van de Poll-Franse LV, Haak HR, Coebergh JW, et al. Disease-specific mortality among stage I-III colorectal cancer patients with diabetes: A large population-based analysis. Diabetologia. 2012;55:2163–2172. doi: 10.1007/s00125-012-2555-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Noh GY, Hwang DY, Choi YH, et al. Effect of diabetes mellitus on outcomes of colorectal cancer. J Korean Soc Coloproctol. 2010;26:424–428. doi: 10.3393/jksc.2010.26.6.424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Park SM, Lim MK, Shin SA, et al. Impact of prediagnosis smoking, alcohol, obesity, and insulin resistance on survival in male cancer patients: National Health Insurance Corporation Study. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:5017–5024. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.07.0243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Taiwan Cancer Registry. Available at http://tcr.cph.ntu.edu.tw/main.php? Page=N1 Accessed February 1, 2012.

- 18.Chiang CJ, Chen YC, Chen CJ, et al. Cancer trends in Taiwan. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2010;40:897–904. doi: 10.1093/jjco/hyq057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.National Health Insurance Administration Ministry of Health and Welfare: Statistics & Surveys. Available at http://www.nhi.gov.tw/English/webdata/webdata.aspx?menu=11&menu_id=296&webdata_id=1942&WD_ID=296 Accessed February 1, 2012.

- 20. Greene FL. AJCC Cancer Staging Manual, 6th ed. New York, NY: Springer-Verlag, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Deyo RA, Cherkin DC, Ciol MA. Adapting a clinical comorbidity index for use with ICD-9-CM administrative databases. J Clin Epidemiol. 1992;45:613–619. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(92)90133-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Quan H, Sundararajan V, Halfon P, et al. Coding algorithms for defining comorbidities in ICD-9-CM and ICD-10 administrative data. Med Care. 2005;43:1130–1139. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000182534.19832.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Health Promotion Administration, Ministry of Health and Welfare. The investigation of the incidence of triple-high status in Taiwan, 2007. Available at http://www.hpa.gov.tw/BHPNet/Web/HealthTopic/TopicArticle.aspx?id=201102140001&parentid=200712250011 Accessed on August 1, 2013.

- 24.Dehal AN, Newton CC, Jacobs EJ, et al. Impact of diabetes mellitus and insulin use on survival after colorectal cancer diagnosis: The Cancer Prevention Study-II Nutrition Cohort. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:53–59. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.38.0303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Polednak AP. Comorbid diabetes mellitus and risk of death after diagnosis of colorectal cancer: A population-based study. Cancer Detect Prev. 2006;30:466–472. doi: 10.1016/j.cdp.2006.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Giovannucci E, Harlan DM, Archer MC, et al. Diabetes and cancer: A consensus report. Diabetes Care. 2010;33:1674–1685. doi: 10.2337/dc10-0666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Campbell PT, Newton CC, Dehal AN, et al. Impact of body mass index on survival after colorectal cancer diagnosis: The Cancer Prevention Study-II Nutrition Cohort. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:42–52. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.38.0287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Forssas E, Sund R, Manderbacka K, et al. Increased cancer mortality in diabetic people treated with insulin: A register-based follow-up study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2013;13:267. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-13-267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Campbell PT, Patel AV, Newton CC, et al. Associations of recreational physical activity and leisure time spent sitting with colorectal cancer survival. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:876–885. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.45.9735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]